Promoting IDPs' and Women's Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia

Promoting IDPs' and Women's Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia

Promoting IDPs' and Women's Voices in Post-Conflict Georgia

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

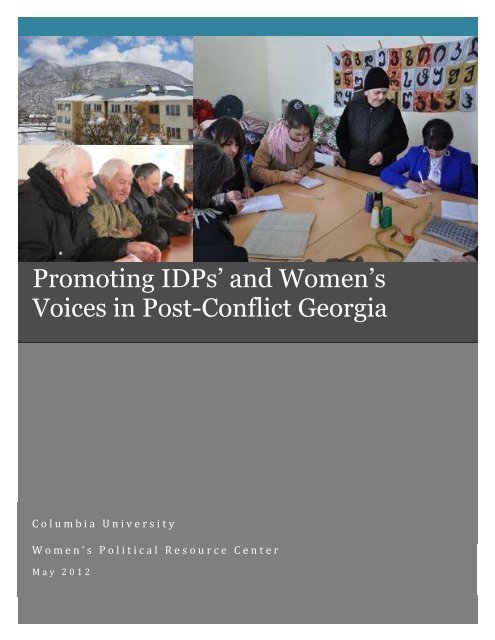

<strong>Promot<strong>in</strong>g</strong> IDPs’ <strong>and</strong> Women’s <strong>Voices</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Post</strong>-<strong>Conflict</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>May 2012Authors:Alex<strong>and</strong>ra dos ReisDrilon GashiSamantha HammerMarissa PolnerowAlej<strong>and</strong>ro Roche del FrailleJan<strong>in</strong>e WhiteCompleted <strong>in</strong> fulfillment of the Workshop <strong>in</strong> Development Practice at Columbia University’s School ofInternational <strong>and</strong> Public Affairs, Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2012.In partnership with the Women’s Political Resource Center, Tbilisi, <strong>Georgia</strong>.Cover images (clockwise): Newly constructed IDP hous<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Potskho-Etseri; Old-wave IDP women focusgroup <strong>in</strong> Tbilisi; New-wave IDP men focus group <strong>in</strong> Karaleti IDP settlement.Cover image sources: Keti Terdzishvili, CARE International, <strong>and</strong> Alej<strong>and</strong>ro Roche del FrailleOther photos: Alej<strong>and</strong>ro Roche del FrailleColumbia UniversitySchool of International <strong>and</strong> Public Affairs420 West 118th StNew York, NY 10027www.sipa.columbia.eduView of Tbilisi, Marissa Polnerow1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSWe are grateful for the support of our client organization, the Women’s Political Resource Center(WPRC), <strong>and</strong> WPRC’s President, Lika Nadaraia, who has extended this unique opportunity to our team.We would also like to thank the supportive staff members of WPRC, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Keti Bakradze, <strong>and</strong>Nanuka Mzhavanadze. We hope that our project will contribute to the valuable work undertaken atWPRC, <strong>and</strong> its newly-launched Frontl<strong>in</strong>e Center <strong>in</strong> Tbilisi.At Columbia University, we were privileged to work with Professor Gocha Lordkipanidze, our academicadvisor, who shared with us a wealth of <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>and</strong> guidance. His knowledge on <strong>Georgia</strong>n society,governance, <strong>in</strong>ternational law, human rights, <strong>and</strong> conflict resolution helped advance our research <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>form this report. Jenny McGill, the Workshop <strong>in</strong> Development Practice Director, <strong>and</strong> Ilona V<strong>in</strong>klerova,the Economic <strong>and</strong> Political Development Concentration Manager, have provided extraord<strong>in</strong>ary supportthat cannot be measured simply by the time they contributed. We would also like to thank Kristy Kelly,Sara M<strong>in</strong>ard, L<strong>in</strong>coln Mitchell <strong>and</strong> David Phillips for shar<strong>in</strong>g their expertise <strong>and</strong> enthusiasm.We very much appreciate the time that the many NGO, government, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational organizationrepresentatives set aside to share their expertise with us <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, as well as <strong>in</strong> New York, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton,D.C., London, <strong>and</strong> Switzerl<strong>and</strong>. We would especially like to thank the staff of Association Gaenati whok<strong>in</strong>dly hosted us <strong>in</strong> Zugdidi <strong>and</strong> helped connect us with other stakeholders <strong>in</strong> the region. We would liketo also thank Dalila Khorava of <strong>Georgia</strong>n Support for Refugees, Vakhtang Piranishvili of CAREInternational, N<strong>in</strong>o Shervashidze <strong>and</strong> Eliko Bendeliani at Sukhumi University, for their help <strong>in</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>gfocus groups that significantly enhanced our research. Some of our <strong>in</strong>terviewees also participated <strong>in</strong> ourroundtable discussion, so we would to thank them for engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a discussion with other stakeholders<strong>and</strong> help<strong>in</strong>g us formulate our recommendations. N<strong>in</strong>o Khelaia, Zita Basl<strong>and</strong>ze <strong>and</strong> Kate Terdzishvili alsoprovided valuable support as <strong>in</strong>terpreters.Our research would not have been possible without the assistance of <strong>in</strong>dividuals across <strong>Georgia</strong> whobravely shared their very personal experiences of displacement with us. Overall, we were <strong>in</strong>crediblytouched by the generosity of all our <strong>in</strong>terviewees, who were quick to extend help<strong>in</strong>g h<strong>and</strong>s <strong>and</strong> providesupport to our project.2

CONTENTSAcronyms <strong>and</strong> Abbreviations 4Executive Summary 5Introduction 6Women’s Political Resource Center 7Country Profile 8Methodology 16Avenues of IDPs’ <strong>and</strong> Women’s Political ParticipationNational Level 22Local Level 32Policymak<strong>in</strong>g 36F<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs: Factors Impact<strong>in</strong>g IDPs’ <strong>and</strong> Women’s Political Participation 53Psychosocial Factors 54Institutional Factors 69Political Factors 79Economic Factors 90Recommendations for <strong>Promot<strong>in</strong>g</strong> IDPs’ <strong>and</strong> Women’s Political Participation 96AppendicesA - Consolidated Recommendations Table 105B - List of IntervieweesC - Human Rights Documents Relevant to IDP Rights <strong>and</strong> Participation106110Bibliography 1143

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONSCEDAWCRCDRCECOSOCEUEUMMEWMIGEADGAFGELGFSISGIPAGYLAHRBAICCPRICESCICGIDMCIDPINGOMDGMRANAPNATONEDNDINGONRCOSAGIOSFOSCEP2PPTSDSIPATIUNDPUNFPAUNHCRUNIFEMUNMUNOMIGUN WomenUSAIDWPRCConvention on the Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of all Forms of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Aga<strong>in</strong>st WomenConvention on the Rights of the ChildDanish Refugee CouncilUnited Nations Economic <strong>and</strong> Social CouncilEuropean UnionEuropean Union Monitor<strong>in</strong>g MissionEast-West Management InstituteGender Equality Advisory Council, Parliament of <strong>Georgia</strong>Gender Analysis Framework<strong>Georgia</strong>n lari<strong>Georgia</strong>n Foundation for Strategic <strong>and</strong> International Studies<strong>Georgia</strong>n Institute of Public Affairs<strong>Georgia</strong>n Young Lawyers AssociationHuman rights-based approachInternational Covenant on Civil <strong>and</strong> Political RightsInternational Covenant on Economic, Social <strong>and</strong> Cultural RightsInternational Crisis GroupInternal Displacement Monitor<strong>in</strong>g CentreInternally Displaced PersonInternational Non-government organizationUnited Nations Millennium Development GoalsM<strong>in</strong>istry for Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories,Refugees <strong>and</strong> AccommodationNational Action PlanNorth Atlantic Treaty OrganizationUnited States National Endowment for DemocracyNational Democratic InstituteNon-governmental organizationNorwegian Refugee CouncilOffice of the Special Advisor on Gender Issues <strong>and</strong> Advancement of WomenOpen Society FoundationOrganization for Security <strong>and</strong> Cooperation <strong>in</strong> EuropePeople-to-people (diplomacy)<strong>Post</strong>-traumatic stress syndromeColumbia University’s School of International <strong>and</strong> Public AffairsTransparency InternationalUnited Nations Development ProgramUnited Nations Population FundThe Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for RefugeesUnited Nations Development Fund for WomenUnited National MovementUnited Nations Observer Mission <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>United Nations Entity for Gender Equality <strong>and</strong> the Empowerment of WomenUnited States Agency for International DevelopmentWomen’s Political Resource Center4

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYInternally displaced persons (IDPs) <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, many liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> protracted displacement s<strong>in</strong>ce the early1990s, face a number of challenges <strong>in</strong> participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> politics <strong>and</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g. Us<strong>in</strong>g a human-rights<strong>and</strong> gender-based approach, this report assesses the extent to which displaced women <strong>and</strong> men are<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> policymak<strong>in</strong>g regard<strong>in</strong>g their needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests. We focus on policies that promote thedurable solutions as def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the UN Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement: return,resettlement, <strong>and</strong> local <strong>in</strong>tegration.Avenues of ParticipationStructures <strong>and</strong> processes support<strong>in</strong>g IDPs’ participation certa<strong>in</strong>ly exist, particularly through civil society,<strong>in</strong> which women are disproportionately more active. Policymak<strong>in</strong>g has also become more <strong>in</strong>clusive, butsignificant improvements are needed <strong>in</strong> implement<strong>in</strong>g policies to ensure IDPs’ effective participation<strong>and</strong> enable them to choose among the durable solutions. A ma<strong>in</strong> challenge for achiev<strong>in</strong>g this objectivelies <strong>in</strong> connect<strong>in</strong>g locally-based problems with a coherent national policy approach that IDPs havehelped to formulate.Factors Influenc<strong>in</strong>g EngagementInterconnected psychosocial, political, <strong>in</strong>stitutional <strong>and</strong> economic issues limit IDPs’ engagement <strong>in</strong>decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> public life more generally. For example, shift<strong>in</strong>g gender roles have affected howmen <strong>and</strong> women deal with displacement, creat<strong>in</strong>g burdens <strong>and</strong> opportunities for participation of bothgenders. Political divisions with<strong>in</strong> IDP communities also pose barriers, <strong>in</strong> addition to a lack of consistentpolitical will, <strong>in</strong>stitutional capacity, <strong>and</strong> coord<strong>in</strong>ation among key stakeholders. F<strong>in</strong>ally, poverty canpromote a vicious cycle, h<strong>in</strong>der<strong>in</strong>g participation while the lack of political voice also serves as a keyobstacle to promot<strong>in</strong>g efforts that address this marg<strong>in</strong>alization.RecommendationsIDPs as rights-holders <strong>and</strong> the state <strong>and</strong> other relevant duty bearers hold different levels ofresponsibility <strong>in</strong> address<strong>in</strong>g this situation. We conclude with recommendations for the Government of<strong>Georgia</strong>, <strong>in</strong>ternational organizations, NGOs, <strong>and</strong> IDP communities can enhance IDPs’ voice <strong>in</strong> policiesthat affect them. Systematic <strong>in</strong>clusion of this group, improved governance, <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>creased cooperationamong stakeholders can support IDPs <strong>in</strong> becom<strong>in</strong>g more active <strong>in</strong>dividually <strong>and</strong> organiz<strong>in</strong>g collectively toadvocate for their needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests. These efforts thereby promote more <strong>in</strong>clusive governance <strong>and</strong>peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g processes <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>n society.5

INTRODUCTIONAugust 2012 marks the 20 th anniversary of the open conflict between the Republic of <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> thebreakaway region of Abkhazia, which led to the displacement of approximately 251,000 <strong>in</strong>ternallydisplaced persons. 1 Another wave of 40,000 people fled the Upper Kodori Gorge <strong>in</strong> Abkhazia <strong>in</strong> 1998.The conflict over Tskh<strong>in</strong>vali region/South Ossetia also displaced about 60,000 people <strong>in</strong> the early 1990s<strong>and</strong> an additional 26,000 IDPs after the August 2008 war. IDPs, compris<strong>in</strong>g about 5% of the <strong>Georgia</strong>npopulation, rema<strong>in</strong> the group <strong>in</strong> society most affected by <strong>Georgia</strong>’s frozen conflicts.International human rights st<strong>and</strong>ards m<strong>and</strong>ate the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government, together with civil society <strong>and</strong>the <strong>in</strong>ternational community, to ensure that IDPs are able to exercise their right to participate <strong>in</strong> publiclife. In particular, accord<strong>in</strong>g to the United Nations Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement, IDPs havea right to participate <strong>in</strong> decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g regard<strong>in</strong>g their specific needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests as IDPs. Whileprogress has been made, IDPs cont<strong>in</strong>ue to face difficulties <strong>in</strong> participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> civic life – with some ofthese difficulties be<strong>in</strong>g unique to IDPs, <strong>and</strong> others shared with the <strong>Georgia</strong>n population as a whole. Theweb of factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g IDPs’ political participation must be more fully understood <strong>in</strong> order for IDPs tobe able to realize this right.The Women’s Political Resource Center (WPRC) has tasked the SIPA consult<strong>in</strong>g team with assess<strong>in</strong>gthese factors through a gendered lens <strong>in</strong> order to see how displaced women <strong>and</strong> men function <strong>in</strong> publiclife <strong>and</strong> the political arena. The consult<strong>in</strong>g team conducted qualitative research <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> theUnited States, employ<strong>in</strong>g human rights-based <strong>and</strong> gender-based approaches to analyze issues ofgovernance <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> with<strong>in</strong> the context of b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational law <strong>and</strong> legal norms.The f<strong>in</strong>al report presents the l<strong>and</strong>scape of avenues <strong>and</strong> processes of women <strong>and</strong> men IDPs’ participation<strong>in</strong> policymak<strong>in</strong>g around the durable solutions of return, resettlement, <strong>and</strong> local <strong>in</strong>tegration. However,several psychosocial, <strong>in</strong>stitutional, political <strong>and</strong> economic factors significantly limit opportunities forIDPs’ engagement. Women IDPs <strong>in</strong> particular, although be<strong>in</strong>g quite active <strong>in</strong> civil society, <strong>in</strong> most casesface additional challenges <strong>in</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g politically active as a result of pressures to conform to traditionalroles. This report contributes to the underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of IDPs’ engagement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>n civic life byexam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g these factors, with the aim of exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g opportunities for displaced women <strong>and</strong> men toparticipate <strong>in</strong> governance <strong>and</strong> peace processes.The report concludes with recommendations for the <strong>Georgia</strong>n Government, civil society actors,<strong>in</strong>ternational donors, <strong>and</strong> the IDP community <strong>in</strong> order to empower action <strong>in</strong> pursuit of these aims.1 <strong>Georgia</strong>. M<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong> Refugees of <strong>Georgia</strong>.“IDP Issues – General Information.” M<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong>Refugees of <strong>Georgia</strong>, N.d. Web. 30 Nov 2011.6

THE WOMEN’S POLITICAL RESOURCE CENTERThis project aligns with the Women’s Political Resource Center’s broader goal of support<strong>in</strong>g women’s<strong>and</strong> vulnerable populations’ political participation. Orig<strong>in</strong>ally founded as the Fem<strong>in</strong>ist Club organization<strong>in</strong> 1998, WPRC has s<strong>in</strong>ce developed <strong>in</strong>to a coalition of non-governmental organizations <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals.The WPRC’s ma<strong>in</strong> objectives are to politically empower women <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> to achieve genderequality <strong>in</strong> the country. WPRC is headquartered <strong>in</strong> Tbilisi <strong>and</strong> has three regional offices, <strong>in</strong> Mtskheta(Mtskheta-Mtianeti region), Poti (Samegrelo region) <strong>and</strong> Kutaisi (Imereti region). 2In 2005, the organization was granted Consultative Status of the United Nations Economic <strong>and</strong> SocialCouncil <strong>and</strong> has as a result exp<strong>and</strong>ed its partnerships to a worldwide network of NGOs <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>clusive relationships. WPRC <strong>in</strong>itiated the creation of an <strong>in</strong>ternational foundation <strong>in</strong> 2006, which,“provides technical assistance to women politicians <strong>and</strong> develops strategies to foster women'sempowerment <strong>and</strong> gender equality <strong>in</strong> democratic governance.” 3 In addition, WPRC is a member of theGender Advisory Council to the <strong>Georgia</strong>n Parliament. The Gender Advisory Council br<strong>in</strong>gs togethergovernment <strong>and</strong> non-government representatives to discuss <strong>and</strong> make recommendations on genderissues <strong>and</strong> to ensure that the voice of women is equal to that of men <strong>in</strong> formulat<strong>in</strong>g public policy at boththe national <strong>and</strong> local level. 4 In the region, <strong>in</strong> 2010, WPRC led the launch of the Caucasian Fem<strong>in</strong>istInitiative, which <strong>in</strong>corporates organizations <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividuals from <strong>Georgia</strong>, Armenia <strong>and</strong> Azerbaijan. TheCenter is part of a network of 40 regional <strong>and</strong> Tbilisi-based women’s organizations. 5WPRC works for women’s human rights through conduct<strong>in</strong>g studies on women's issues <strong>and</strong> advocat<strong>in</strong>glegislative recommendations promot<strong>in</strong>g gender equality. Besides provid<strong>in</strong>g technical assistance,conduct<strong>in</strong>g research, consult<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> engag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> other analytical <strong>and</strong> educational activities, the WPRC isactive <strong>in</strong> conduct<strong>in</strong>g forums, lectures, media campaigns <strong>and</strong> public actions. 6 WPRC works closely withdifferent <strong>in</strong>ternational NGOs <strong>and</strong> donors on form<strong>in</strong>g public op<strong>in</strong>ion regard<strong>in</strong>g the participation ofwomen, ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced persons (IDPs) <strong>in</strong> political processes <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. 7 PriorSIPA consult<strong>in</strong>g teams have worked <strong>in</strong> cooperation with WPRC on projects concern<strong>in</strong>g domestic violence<strong>and</strong> traffick<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> on gender equality with<strong>in</strong> the <strong>Georgia</strong>n education system.2 "About Us." Womens Political Resource Center. Web. 03 Dec. 2011.3 Ibid.4 "Gender Advisory Council under the Chairperson of the Parliament of <strong>Georgia</strong> – the First Institutional Mechanism." Parliamentof <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 03 Dec. 2011..5 "<strong>Women's</strong> Political Resource Center (WPRC)." Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Portal. Web. 03 Dec. 2011.6 "About Us." Womens Political Resource Center. Web. 03 Dec. 2011.7 "<strong>Women's</strong> Political Resource Center (WPRC)." Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g Portal.7

COUNTRY PROFILEPolitical Context<strong>Georgia</strong> has seen a turbulent past two decades. The country rega<strong>in</strong>ed its<strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> 1991 <strong>and</strong> shortly thereafter lapsed <strong>in</strong>to civil conflictover Abkhazia; embarked on a program of accelerated state- <strong>and</strong>democracy-build<strong>in</strong>g with the Rose Revolution <strong>in</strong> 2004; <strong>and</strong> suffered amajor setback when war with Russia erupted <strong>in</strong> 2008.Establish<strong>in</strong>g a democratic <strong>Georgia</strong>n state follow<strong>in</strong>g the fall of the SovietUnion presented an enormous challenge <strong>and</strong> cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be a work <strong>in</strong>progress. Over the past eight years, current President Mikheil Saakashvilihas embarked on ambitious political <strong>and</strong> economic reforms, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g re-mak<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Georgia</strong>n police,virtually elim<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g everyday corruption, de-regulat<strong>in</strong>g the economy, <strong>and</strong> arrest<strong>in</strong>g oligarchic bus<strong>in</strong>essfigures. However, concerns have been raised over state-supported limitations on freedom of speech,state control of the <strong>Georgia</strong>n media, <strong>and</strong> centralization of power, which has strengthened thepresidency at the expense of the legislature. 8 Issues of territorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity have compounded thechallenges of state build<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> reta<strong>in</strong> great importance <strong>in</strong> political discourse.<strong>Georgia</strong>n civil society proved its ability to have political <strong>and</strong> social impact <strong>in</strong> 2003 through its central role<strong>in</strong> the Rose Revolution. S<strong>in</strong>ce then, however, it has lost much of its national <strong>in</strong>fluence due to political,social, <strong>and</strong> economic circumstances. UNDP’s <strong>Georgia</strong> Programme Country Action Plan sums it up: “thecivil society sector is yet to become systemic <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence players <strong>in</strong> policy development <strong>and</strong> decisionmak<strong>in</strong>g.At the moment, the organizations lack concentration, capacity, <strong>and</strong> resources <strong>and</strong> oftenenterta<strong>in</strong> donor-driven <strong>in</strong>terest.” 9 Also, the <strong>Georgia</strong>n Government appears to be generally reluctant to<strong>in</strong>volve civil society organizations <strong>in</strong> the policymak<strong>in</strong>g process, although it has recently made certa<strong>in</strong>improvements <strong>in</strong> this area.Public confidence <strong>in</strong> civil society <strong>in</strong>stitutions other than the <strong>Georgia</strong>n Orthodox Church is quite low.While relatively few <strong>Georgia</strong>ns participate <strong>in</strong> NGOs <strong>and</strong> other civil society groups, non-<strong>in</strong>stitutionalizedparticipation (<strong>in</strong> neighborhood or community groups, etc.) is quite high, at 7.1%. 10Media freedom <strong>in</strong> particular cont<strong>in</strong>ues to be a concern, as it seems to be decreas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. GlobalIntegrity found <strong>in</strong> 2009 that <strong>Georgia</strong>n media, especially broadcast media, faces obstacles to produc<strong>in</strong>g8 Mitchell, 70. (“<strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>Post</strong>bellum”); De Waal, 6,9.9 Government of <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> United Nations Development Programme, <strong>Georgia</strong>. Country Programme Action Plan Between theGovernment of <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> the United Nations Development Programme, 2011-2015. Tbilisi: United Nations DevelopmentProgram, <strong>Georgia</strong>, 2011. Web. 26 Nov. 2011.10 Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy <strong>and</strong> Development <strong>and</strong> CIVICUS, 428

fair report<strong>in</strong>g on politically sensitive topics. As most media outlets were highly sympathetic to the newgovernment follow<strong>in</strong>g the Rose Revolution, the government was readily able to shape report<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> itsfavor. Today, citizens believe that media outlets are biased, <strong>and</strong> they largely do not trust theirreport<strong>in</strong>g. 11<strong>Georgia</strong>’s current political environment lacks accountability, with divisions among the opposition <strong>and</strong>marg<strong>in</strong>alization of other civil society <strong>in</strong>stitutions mak<strong>in</strong>g it difficult to check the power of the govern<strong>in</strong>gUnited National Movement (UNM) Party. More recent political debate has focused on two ma<strong>in</strong> issuesfor <strong>Georgia</strong>n politics: how the new 150-seat parliament will be formed —whether the UNM Party willaga<strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong> 71 of the 75 s<strong>in</strong>gle-seat constituencies by a s<strong>in</strong>gle majority— <strong>and</strong> whether Mikheil Saakashviliwill become the prime m<strong>in</strong>ister after the upcom<strong>in</strong>g elections, thereby rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the most powerful man<strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. 12 Regard<strong>in</strong>g public perception about democracy, there is a sharp division between UNMsupporters <strong>and</strong> supporters of the ma<strong>in</strong> opposition leader, Bidz<strong>in</strong>a Ivanishvili. Among the former, 69.8%th<strong>in</strong>k that there is democracy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, while among the latter only 12.5% agree. 13Economic Context<strong>Georgia</strong> has experienced significant economic growth <strong>in</strong> the last decade, with GDP growth <strong>in</strong> the 9–12%range <strong>in</strong> 2005–07, <strong>and</strong> 6.8% GDP growth <strong>in</strong> 2011. 14 The International F<strong>in</strong>ance Corporation’s “Do<strong>in</strong>gBus<strong>in</strong>ess 2011” study ranked <strong>Georgia</strong>’s economy as number one among improvements <strong>in</strong> 174 countriesover the past five years on the ease of do<strong>in</strong>g bus<strong>in</strong>ess. 15In spite of these improvements, <strong>Georgia</strong> is still considered a develop<strong>in</strong>g country accord<strong>in</strong>g to theInternational Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Report. 16 <strong>Georgia</strong>’s GDP per capita <strong>in</strong> 2011 was$5,491, rank<strong>in</strong>g 112 th <strong>in</strong> the world. 17 <strong>Post</strong>-Soviet reconstruction, two civil conflicts <strong>and</strong> the globalrecession have contributed to the impoverishment of a large section of the <strong>Georgia</strong>n population. About11% of the population rema<strong>in</strong>s poor accord<strong>in</strong>g to World Bank’s st<strong>and</strong>ards. 18Unemployment has been a persistent problem <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> ever s<strong>in</strong>ce the country ga<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong>1991. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the National Statistics Office of <strong>Georgia</strong>, unemployment rate stood at 16.3% <strong>in</strong>2010. 19 This is by far the highest level among the former Soviet Union countries. 20 The official statisticalso does not reflect the vast discrepancies between urban <strong>and</strong> rural areas of the country. Themethodology used to keep track of unemployment produces relatively low unemployment rates for11 Global Integrity. Global Integrity Scorecard: <strong>Georgia</strong>. Global Integrity (2009). Web. 24 Nov. 2011.12 Ibid, 21; Economist Intelligence Unit, Geoegia – Politics. n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.13 Institute for Policy Studies. Electorate profile: Report of the survey. Tbilisi, 2012. 32.14 International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Report. April 2011. Web. 30 April 2012.15 International F<strong>in</strong>ance Corporation, “<strong>Georgia</strong> Shares Experience to Improve Bus<strong>in</strong>ess Regulation Environment <strong>in</strong> Region,” Web.21 May 2012.16 International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook Report. April 2011. Web. 30 April 2012.17 World Economic Outlook Database – April 2012. International Monetary Fund. Web. 28 April 2012.18 The World Bank. <strong>Georgia</strong>: Poverty <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>come distribution. Web. 30 April 2012.19 Employment <strong>and</strong> unemployment. National Statistics Office of <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 28 April 2012.20 Statistical yearbook of <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 28 April 2012.9

ural areas (4.8% as 2006 21 ). By contrast, the average unemployment rate <strong>in</strong> cities is 26% 22 , while<strong>in</strong> Tbilisi unemployment is reported to be reach<strong>in</strong>g 40%. 23Foreign aid plays a prom<strong>in</strong>ent role <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>’s annual budget. More than US $1.5 billion (approximatelyGEL 2.1 billion) were delivered annually by donors between 2009-11. The state’s annual budget <strong>in</strong> eachof those years was 6.75, 6.97 <strong>and</strong> 7.35 billion GEL, respectively. 24 In addition, foreign direct <strong>in</strong>vestmenthas significantly decl<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce the late-2000s global recession, not least due to conflict <strong>in</strong> thecountry. S<strong>in</strong>ce the 2008 war, <strong>in</strong>flation has risen substantially <strong>and</strong> the country faces problems <strong>in</strong>generat<strong>in</strong>g revenue. <strong>Georgia</strong> has also suffered substantial <strong>in</strong>frastructure damage from the 2008 war <strong>and</strong>has faced the burden of provid<strong>in</strong>g for several thous<strong>and</strong> IDPs from conflict areas. With all of <strong>Georgia</strong>’schallenges, perhaps its greatest —especially accord<strong>in</strong>g to the <strong>Georgia</strong>n people— is to create jobs. 25<strong>Conflict</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Peace ProcessesThe conflicts between <strong>Georgia</strong>ns, South Ossetians, <strong>and</strong> Abkhaz have deep-seated roots. The breakup ofthe Soviet Union provided a catalyst for civil wars, with <strong>Georgia</strong> fight<strong>in</strong>g to conta<strong>in</strong> South Ossetia <strong>and</strong>Abkhazia with<strong>in</strong> its borders, <strong>and</strong> the latter entities seek<strong>in</strong>g self-determ<strong>in</strong>ation. 26 Hostilities erupted <strong>in</strong>South Ossetia <strong>in</strong> 1990, <strong>and</strong> despite a cease-fire two years later, the region has rema<strong>in</strong>ed unstable.President Saakashvili has repeatedly sought autonomy for South Ossetia <strong>in</strong>side <strong>Georgia</strong>, while Ossetianleaders cont<strong>in</strong>ue to call for the reunification of North <strong>and</strong> South Ossetia. 27 Parallel<strong>in</strong>g South Ossetia’sstory <strong>in</strong> many ways, war broke out <strong>in</strong> Abkhazia <strong>in</strong> 1993. The parties achieved a cease-fire <strong>in</strong> May 1994but the contradiction between Abkhazia’s unrecognized de facto <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>and</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>’s de jureterritorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity 28 cont<strong>in</strong>ues to shape the dynamics of the conflict.These unresolved conflicts <strong>in</strong>flamed tensions between <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> Russia, f<strong>in</strong>ally result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> warbetween the two countries <strong>in</strong> August 2008. 29 The war caused hundreds of casualties on both sides, <strong>in</strong>addition to a new wave of <strong>Georgia</strong>ns becom<strong>in</strong>g displaced. The parties reached a prelim<strong>in</strong>ary ceasefireagreement after five days, but Russia has yet to fully implement the six-po<strong>in</strong>t plan, ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g troops <strong>in</strong>the conflict regions <strong>and</strong> prevent<strong>in</strong>g the return of IDPs. In the effort to resolve the broader conflict,<strong>Georgia</strong>ns —<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Abkhaz governments-<strong>in</strong>-exile <strong>and</strong> representatives from South Ossetia—, <strong>and</strong>Russians are currently engaged <strong>in</strong> peace talks <strong>in</strong> Geneva, which also <strong>in</strong>clude South Ossetian <strong>and</strong> Abkhazparticipants <strong>and</strong> EU, US, UN <strong>and</strong> OSCE mediators. 30 However, the talks rema<strong>in</strong> stalled with the majorissues of territorial <strong>in</strong>tegrity, sovereignty <strong>and</strong> return of displaced persons unresolved. So far, limited21 Employment <strong>and</strong> unemployment. National Statistics Office of <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 28 April 2012.22 Ibid.23 Widespread unemployment takes its toll – World Vision. Web. 28 April 2012.24 Transparency International. Web. 6 May 2012.25 de Waal, 2011. 10-14; Economist Intelligence Unit. <strong>Georgia</strong> – Economy. n.d. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.26 Cornell, Svante E, <strong>and</strong> S F. Starr. The Guns of August 2008: Russia's War <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. Armonk, N.Y: M.E. Sharpe, 2009, 5.27 Gahrton, Per. <strong>Georgia</strong>: Pawn <strong>in</strong> the New Great Game. London: Pluto Press, 2010, 60-63.28 Ciobanu, Ceslav. Frozen <strong>and</strong> Forgotten <strong>Conflict</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Post</strong>-Soviet States: Genesis, Political Economy <strong>and</strong> Prospects forSolution. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 2009, 113.29 Cornell <strong>and</strong> Starr, 143; Ciobanu, 118.30 Gahrton, 74.10

people-to-people diplomacy efforts have not effectively supplemented Track I efforts at conflictresolution.Russia claims to be just a peacekeeper, but its military <strong>and</strong> economic support to Abkhazia <strong>and</strong> SouthOssetia make Russia a key actor <strong>in</strong> the conflict. While the two countries have not reestablisheddiplomatic relations s<strong>in</strong>ce the 2008 war, a senior <strong>Georgia</strong>n government official emphasized that theymust engage Moscow <strong>in</strong> work<strong>in</strong>g towards a solution, s<strong>in</strong>ce Russia has the last word <strong>in</strong> all major decisionsregard<strong>in</strong>g security, troops or return of IDPs. 31 This fact, coupled with Russia’s military power —especially compared to <strong>Georgia</strong>’s — makes any potential solution to the conflict dependent on Russia’s<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> the geopolitical context. Moreover, the United States <strong>and</strong> the European Union are also keyplayers <strong>in</strong> the effort to reach a susta<strong>in</strong>able deal.IDPs’ Social, Legal <strong>and</strong> Political SituationThe government of <strong>Georgia</strong> legally recognizes “<strong>in</strong>ternally displaced persons – persecuted” as citizens of<strong>Georgia</strong> or stateless persons who permanently reside with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> who were forced to flee fromthe conflict regions. 32 The Law on Forcibly Displaced Persons – Persecuted from the Occupied Territoriesof <strong>Georgia</strong>, last amended <strong>in</strong> 2011, def<strong>in</strong>es <strong>and</strong> regulates IDP status. The Law also sets out <strong>in</strong> generalterms the specific rights of the <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced <strong>in</strong> their places of temporary residence <strong>and</strong> upon theirreturn to their pre-displacement residences. 33 The Law establishes the grant<strong>in</strong>g of the IDP status tochildren of IDPs, entitles IDPs to a monthly allowance <strong>and</strong> free health care <strong>and</strong> education, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gsecondary education.The government recognizes the presence of 251,000 IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> as a result of conflicts <strong>in</strong> Abkhazia<strong>and</strong> Tskh<strong>in</strong>vali region/South Ossetia <strong>in</strong> the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g of 1990s, compris<strong>in</strong>g the “old wave.” In addition,about 26,000 people displaced from Tsk<strong>in</strong>vali region/South Ossetian as a result of the August 2008 warform the “new wave.” UNHCR estimated <strong>in</strong> 2011 that 54% of IDPs were female, 24% were children <strong>and</strong>17% were older persons. 34 The majority of the IDPs live <strong>in</strong> the municipalities of Tbilisi, Kutaisi, or Zugdidi.About 39% of “old wave” IDPs live <strong>in</strong> government-owned collective centers, many of which are rundown.The rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g 61% live <strong>in</strong> private accommodations either on their own or with another family. 35The number of IDPs liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> collective centers has decreased <strong>in</strong> recent years due to efforts by the<strong>Georgia</strong>n government to resettle IDPs <strong>in</strong>to private accommodations, particularly through a privatizationplan for collective centers. The assumption beh<strong>in</strong>d this decision is that those IDPs liv<strong>in</strong>g among the localpopulation will more easily become socially <strong>and</strong> economically <strong>in</strong>tegrated. However, unemployment31 Senior Government Official (Government of <strong>Georgia</strong>), Personal Interview, 3 February 2012.32 <strong>Georgia</strong>. M<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong> Refugees of <strong>Georgia</strong>.“IDP Issues – General Information.” M<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong>Refugees of <strong>Georgia</strong>, N.d. Web. 30 Nov 2011.33 Brook<strong>in</strong>gs. National <strong>and</strong> Regional Laws <strong>and</strong> Policies on Internal Displacement – <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 28 April 2012.34 Internal Displacement Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Centre. <strong>Georgia</strong>: Partial progress towards durable solutions for IDPs. A profile of the<strong>in</strong>ternal displacement situation. 21 March, 2012. 55.35 Internal Displacement Monitor<strong>in</strong>g Centre, 56.11

estimates among IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the 35% to 45% range, which is substantially higher than theestimated 16% for the non-displaced population. 36The situation of IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> is similar to other cases <strong>in</strong> the region, such as Azerbaijan, where IDPs arealso a particularly vulnerable group. Like <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, a large part of the IDPs <strong>in</strong> Azerbaijan are liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>collective centers characterized by <strong>in</strong>sufficient hous<strong>in</strong>g conditions <strong>and</strong> have limited access to the labormarket. Government <strong>in</strong>itiatives to target IDP needs <strong>in</strong> both countries are also very similar: they are oftenlimited to cash <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>-k<strong>in</strong>d benefits such as social assistance, free usage of healthcare or free provisionof electricity, gas <strong>and</strong> water. 37 Moreover, the IDP issue has been politicized <strong>in</strong> both countries, as IDPs’<strong>in</strong>tegration has been forestalled <strong>in</strong> the effort to cont<strong>in</strong>ue to lay claim over the conflict regions.More than 200 legislative acts <strong>and</strong> bylaws have been issued regard<strong>in</strong>g the legal <strong>and</strong> social protection ofIDPs, <strong>and</strong> an ad hoc m<strong>in</strong>istry —the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Refugees <strong>and</strong> Accommodation, now officially calledM<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong> Refugees(but <strong>in</strong> shorth<strong>and</strong> still referred to as the MRA)— was set up <strong>in</strong> 1995. In accordance with the Law on IDPs36 Mitchneck, Beth, Olga V. Mayorova <strong>and</strong> Joanna Regulska. “<strong>Post</strong>-<strong>Conflict</strong> Displacement: Isolation <strong>and</strong> Integration <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>.”Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 99.5 Feb. 2009: 1022-1032. Web. 21 Nov. 2011.37 European Commission. Social protection <strong>and</strong> social <strong>in</strong>clusion <strong>in</strong> Armenia, Azerbaijan <strong>and</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. 2011. 13.12

<strong>and</strong> the Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples, <strong>in</strong> February 2007, the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government approved the State Strategy forInternally Displaced Persons – Persecuted. In May 2010, it subsequently approved the Action Plan forthe Implementation of the State Strategy on IDPs dur<strong>in</strong>g 2009-2012.The State Strategy on IDPs <strong>and</strong> the Action Plan for the Implementation of the State Strategy serve as thebasis for the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government’s policies on IDPs. Before the draft<strong>in</strong>g of the State Strategy, therehad been no comprehensive approach to address<strong>in</strong>g IDPs’ specific rights <strong>and</strong> needs. In fact, prior toFebruary 2007, when the State Strategy on IDPs was adopted, the government actively worked aga<strong>in</strong>stIDPs’ <strong>in</strong>tegration, as their presence as <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced persons symbolized <strong>Georgia</strong>’s claim to thebreakaway territories of Abkhazia <strong>and</strong> South Ossetia.The State Strategy represents a paradigm shift <strong>in</strong> this discussion by counter<strong>in</strong>g the idea that return <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>tegration are mutually exclusive. It outl<strong>in</strong>es two ma<strong>in</strong> goals: (i) “to create conditions for dignified <strong>and</strong>safe return of IDPs <strong>and</strong> to support IDPs who have spontaneously returned to their places of permanentresidence,” <strong>and</strong> (ii) “to support decent liv<strong>in</strong>g conditions for the displaced population <strong>and</strong> their<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong> all aspects of society.” 38Regard<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government’s duties to its population to enable their participation, as a StateParty to the International Covenant on Civil <strong>and</strong> Political Rights, it is required under Article 25 to permitevery citizen, without unreasonable restrictions, the right <strong>and</strong> opportunity to: (i) “take part <strong>in</strong> theconduct of public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives,” (ii) “to vote <strong>and</strong> be electedat genu<strong>in</strong>e periodic elections which shall be by universal <strong>and</strong> equal suffrage <strong>and</strong> shall be held by secretballot, guarantee<strong>in</strong>g the free expression of the will of the electors,” <strong>and</strong> (iii) “To have access, on generalterms of equality, to public service <strong>in</strong> his country.” 39 As a State Party to the European Charter on HumanRights, Article 3, Protocol 1 also obligates the state to hold free elections.IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> have an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> political <strong>and</strong> civic affairs, especially because of thesupport they rely on from national authorities. Their needs <strong>in</strong>clude shelter, food, health care, <strong>and</strong>security. Women <strong>and</strong> children IDPs are vulnerable to abuse <strong>and</strong> sexual exploitation <strong>and</strong> particularly relyon authorities to provide security. More expansive IDP participation <strong>in</strong> elections will better address IDPneeds, <strong>and</strong> also opens up avenues to address societal <strong>in</strong>equities to promote reconciliation. The StateStrategy for IDPs recognizes the importance of IDPs’ election-related rights to help facilitate their<strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong>to <strong>Georgia</strong>n society. 40Particularly <strong>in</strong> the years follow<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>itial displacement <strong>in</strong> the early 1990s, <strong>Georgia</strong>n political forceshave attempted to use the IDP community as leverage <strong>in</strong> the peace process. The Abkhaz government-<strong>in</strong>-38 <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 30 Nov 2011.39 United Nations. International Covenant on Civil <strong>and</strong> Political Rights, Article 25, UN Doc. A/6316 (1966)40 Solomon, Andrew. “Election-Related Rights <strong>and</strong> Political Participation of Internally Displaced Persons: Protection Dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>After Displacement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> Prepared by Andrew Solomon.” Brook<strong>in</strong>gs Institution, Nov. 2009: 1-3. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.13

exile seemed to represent a revanchist group that could pose a political threat to Abkhazia. 41 In manyways, the IDP community’s marg<strong>in</strong>alization <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> results <strong>in</strong> the challenge of contribut<strong>in</strong>g morevaried <strong>and</strong> nuanced perspectives to both the formal peace process <strong>and</strong> more <strong>in</strong>formal peace build<strong>in</strong>gefforts with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Abkhazia, <strong>and</strong> South Ossetia.Women <strong>and</strong> Gender LegislationA cont<strong>in</strong>ued stream of legislation has been passed s<strong>in</strong>ce 2006 to address women’s issues <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>,reflect<strong>in</strong>g the perspective that <strong>Georgia</strong> seems to aspire towards gender equality. Reports have citeddifferences <strong>in</strong> approaches to these issues across the South Caucasus, with Armenia <strong>and</strong> Azerbaijan moreoriented towards traditional gender roles than <strong>Georgia</strong>. 42 However, several important issues rema<strong>in</strong>concern<strong>in</strong>g women’s empowerment. <strong>Georgia</strong> ranks 86 th out of 135 countries on the World EconomicForum’s Global Gender Gap <strong>in</strong>dex. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, Armenia <strong>and</strong> Azerbaijan have comparable rank<strong>in</strong>gs at84 th <strong>and</strong> 91 st place, respectively. <strong>Georgia</strong>’s rank<strong>in</strong>g has rema<strong>in</strong>ed stagnant s<strong>in</strong>ce 2006, with politicalempowerment <strong>and</strong> economic participation rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g virtually unchanged:Evolution of Key Gender Gap Sub Indexes 43Of particular significance to this report is <strong>Georgia</strong>’s low score on the political empowerment <strong>in</strong>dicator:only three of the 19 m<strong>in</strong>isters <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>’s government are female, <strong>and</strong> n<strong>in</strong>e of the 140 members ofparliament, while women hold under 11% of seats on local assemblies. These numbers amount to thelowest level of female participation <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>n politics s<strong>in</strong>ce the country’s <strong>in</strong>dependence <strong>in</strong> 1991. 44Women’s low political participation can be partially expla<strong>in</strong>ed by cultural gender stereotypes that placewomen <strong>and</strong> men <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> societal roles. More specifically, an Open Society <strong>Georgia</strong> study of publicvalues conducted <strong>in</strong> 2006 showed that <strong>Georgia</strong>n men <strong>and</strong> women do not view women as politicians. 45 In41 Ibid., 16.42 Caucasus Research Resource Center, “How Does the South Caucasus Compare?,” 5 October 2011. Web. 21 May 2012, 2.43 From the 2011 Global Gender Gap Report - <strong>Georgia</strong> Country Profile44 Shorana Latatia. Women Los<strong>in</strong>g Out <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>n Politics. Institute for War <strong>and</strong> Peace Report<strong>in</strong>g. 18 Mar. 2011. Web. 19 Nov.2011.45 Ibid.14

an effort to address these stereotypes <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>crease the number of women <strong>in</strong> politics, lead<strong>in</strong>g activistsadvocate for party <strong>and</strong> parliamentary quotas. 46In March 2010 the Parliament of <strong>Georgia</strong> passed the Gender Equality Law, which put <strong>in</strong> place<strong>in</strong>stitutional mechanisms to improve gender issues at the legislative level. The legislation provides forthe establishment of a national women’s mach<strong>in</strong>ery, the enhancement of women’s security, equality <strong>in</strong>the labor market <strong>and</strong> the strengthen<strong>in</strong>g of women’s political participation. The law also encouragesgender-responsive plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> budget<strong>in</strong>g on the part of the government. 47<strong>Georgia</strong> has also ratified the UN Convention on Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of All Forms of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Aga<strong>in</strong>stWomen (CEDAW) <strong>in</strong> 1994, but the CEDAW Committee flagged several human rights concerns. These<strong>in</strong>clude limited sex-disaggregated data, traffick<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> women <strong>and</strong> girls, <strong>and</strong> underrepresentation ofwomen <strong>in</strong> public <strong>and</strong> political life.Although current reforms seek to address these problems, significant gender gaps persist at all levels ofsociety, particularly for rural <strong>and</strong> IDP women. In many ways, women IDPs face even moremarg<strong>in</strong>alization <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>n society <strong>and</strong> have had m<strong>in</strong>imal <strong>in</strong>fluence over national policymak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong>conflict resolution processes. 48 However, the effort to promote women’s <strong>in</strong>volvement has receivedattention with a number of <strong>in</strong>itiatives around the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 <strong>and</strong> its sisterresolutions (1820, 1888, 1889, <strong>and</strong> 1960) on Women, Peace <strong>and</strong> Security. This set of resolutions calls foradopt<strong>in</strong>g a gender perspective <strong>and</strong> recogniz<strong>in</strong>g the needs of women <strong>and</strong> girls <strong>in</strong> post-conflict sett<strong>in</strong>gs. 49In 2010, a Gender Equality National Action Plan was drafted for the implementation of Resolution 1325<strong>and</strong> was approved by the Parliament of <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>in</strong> December 2011. 50 NGOs founded by <strong>and</strong> for womenhave also contributed extensively to develop<strong>in</strong>g the State Strategy on IDPs <strong>in</strong> 2007, <strong>and</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g theAugust War, they mobilized to provide humanitarian assistance to the new wave of IDPs. The upcom<strong>in</strong>gsections will present our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs on the important role of women’s NGOs, particularly IDP NGOs <strong>in</strong>promot<strong>in</strong>g the political participation of these groups.46 Organization for Security <strong>and</strong> Co-operation <strong>in</strong> Europe. <strong>Georgia</strong> - Gender Equality Indicators 2007. Organization for Security<strong>and</strong> Co-operation <strong>in</strong> Europe. 2007. Web. 22 Nov. 2011.47 Shiolashvili, Neli. Statement to the United Nations General Assembly Third Committee on Agenda Item 28(a), Advancementof Women. United Nations. United Nations Headquarters, New York, NY. 11 Oct. 2011. Web. 20 Nov. 2011.48 Women’s Information Center. Women, Peace <strong>and</strong> Security: Implementation of the UN Security Council Resolution No. 1325 <strong>in</strong><strong>Georgia</strong>. Tbilisi: Women’s Information Center, 2011. Web. 21 Nov. 2011. 25.49 United Nations. Security Council. Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000). 31 Oct. 2000. Web. 15 Nov. 2011.50 Ibid.15

METHODOLOGYResearch questionsOur research aims to promote more <strong>in</strong>clusive governance <strong>and</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g around IDP issues <strong>in</strong><strong>Georgia</strong>. Therefore, we seek to answer the follow<strong>in</strong>g three-part question:1. To what extent are <strong>in</strong>ternally displaced men <strong>and</strong> women <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> policymak<strong>in</strong>gregard<strong>in</strong>g their needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests as IDPs?2. What factors affect women <strong>and</strong> men <strong>IDPs'</strong> participation <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence overpolicymak<strong>in</strong>g regard<strong>in</strong>g their needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests as IDPs?3. What opportunities exist to promote effective, <strong>in</strong>clusive <strong>and</strong> gender-balanced IDPparticipation <strong>in</strong> these processes so that they will better address <strong>IDPs'</strong> specific rights,needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests?Key Concepts <strong>and</strong> Def<strong>in</strong>itionsInternally displaced persons (IDPs) 51 : We use the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government’s def<strong>in</strong>ition of: “<strong>in</strong>ternallydisplaced persons – persecuted” as citizens of <strong>Georgia</strong> or stateless persons who permanently residewith<strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> who were forced to flee their places of residence due to threats to a “family member’slife, health or freedom due to the aggression of foreign country, <strong>in</strong>ternal conflicts or mass violation ofhuman rights.” 52 We have also compared this def<strong>in</strong>ition with the more general def<strong>in</strong>ition presented <strong>in</strong>the UN’s Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement, discussed more <strong>in</strong> detail below. Adopt<strong>in</strong>g theconvention of previous studies, we use the term “old wave IDP” for those who were displaced dur<strong>in</strong>gthe conflicts of the 1990s, while “new wave IDPs” were displaced dur<strong>in</strong>g the 2008 conflict.Our research design <strong>and</strong> process considers two central ideas generally regard<strong>in</strong>g IDP populations:IDPs are entitled to enjoy, equally <strong>and</strong> without discrim<strong>in</strong>ation, the same rights <strong>and</strong> freedomsunder <strong>in</strong>ternational <strong>and</strong> domestic law as do other persons <strong>in</strong> their country. 53 Individuals areidentified as such so that they can be granted legal protection, due to the vulnerability thatmembers of this population face.51 Our research considers only conflict-affected IDPs currently resid<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> proper. Due to a lack of <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>and</strong>access, our research does not <strong>in</strong>clude IDPs who have returned to the conflict regions s<strong>in</strong>ce displacement or who were displacedwith<strong>in</strong> the conflict regions.52 M<strong>in</strong>istry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Accommodation <strong>and</strong> Refugees of <strong>Georgia</strong>. Web. 4Dec. 2011.53 UNHCR, H<strong>and</strong>book for the Protection of Internally Displaced Persons, 2008.16

The identities, perceptions, <strong>and</strong> relationships l<strong>in</strong>ked to <strong>in</strong>dividuals fall<strong>in</strong>g under the formaldef<strong>in</strong>ition of “IDP” are fluid <strong>and</strong> often situationally-determ<strong>in</strong>ed as dist<strong>in</strong>guished from the morestatic, legal def<strong>in</strong>ition.Throughout this paper, we question the logic <strong>and</strong> efficacy of conceptualiz<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Georgia</strong>n IDPs as a discrete<strong>and</strong> unified <strong>in</strong>terest group. IDPs’ needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests are highly conditioned by factors such as period ofdisplacement, place of orig<strong>in</strong>, gender, liv<strong>in</strong>g situation, socio-economic status, age <strong>and</strong> other aspects ofidentity. Therefore, we conclude that discussions of the needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests of IDPs as a discrete group,IDP unity <strong>and</strong> social <strong>and</strong> political power must be grounded <strong>in</strong> a specific context or issue.Gender: UN Women def<strong>in</strong>es this term as “social attributes <strong>and</strong> opportunities associated with be<strong>in</strong>g male<strong>and</strong> female <strong>and</strong> the relationships between women <strong>and</strong> men <strong>and</strong> girls <strong>and</strong> boys, as well as the relationsbetween women <strong>and</strong> those between men…Gender is part of the broader socio-cultural context.” As aresult, “these attributes, opportunities <strong>and</strong> relationships are socially constructed…In most societiesthere are differences <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>equalities between women <strong>and</strong> men <strong>in</strong> responsibilities assigned, activitiesundertaken, access to <strong>and</strong> control over resources, as well as decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g opportunities. Otherimportant criteria for socio-cultural analysis <strong>in</strong>clude class, race, poverty level, ethnic group <strong>and</strong> age.” 54Specifically, we consider how gender <strong>and</strong> other aspects of identity <strong>in</strong>fluence women’s <strong>and</strong> men’sexperiences of displacement <strong>and</strong> opportunities for participation <strong>in</strong> public life.Political participation: We view political participation as encompass<strong>in</strong>g a wide variety of <strong>in</strong>tentional <strong>and</strong>coord<strong>in</strong>ated, as well as un<strong>in</strong>tentional <strong>and</strong> uncoord<strong>in</strong>ated actions, behaviors, <strong>and</strong> modes of thoughtaimed at <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g governance. Forms of political participation <strong>in</strong>clude vot<strong>in</strong>g, civil disobedience,media campaigns, <strong>and</strong> other legally permitted practices. They can be coord<strong>in</strong>ated by <strong>in</strong>dividuals,through communities, through civil society, political parties, <strong>and</strong> other channels. Policymak<strong>in</strong>g alsoreflects political participation from different angles, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the groups that contribute to itsformulation, negotiation, passage <strong>and</strong> implementation. When exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g policymak<strong>in</strong>g, we pay specialattention to which stakeholders are <strong>in</strong>formed <strong>and</strong> consulted, <strong>and</strong> which are represented <strong>in</strong>, contributeto, <strong>and</strong> have authority over decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g. We have narrowed our focus to only <strong>in</strong>clude IDPs’participation around policymak<strong>in</strong>g concern<strong>in</strong>g opportunities to choose among the three durablesolutions, return, resettlement, <strong>and</strong> local <strong>in</strong>tegration. As these policies are dist<strong>in</strong>ct to IDP needs <strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>terests, this group should have the most <strong>in</strong>fluence over their content <strong>and</strong> its implementation.Peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g: We underst<strong>and</strong> this concept as long-term conflict resolution/transformation thatnecessarily <strong>in</strong>cludes both Track I <strong>and</strong> Track II approaches. We exam<strong>in</strong>e both, as well as the connectionsbetween them <strong>in</strong> the <strong>Georgia</strong>n case. Track I <strong>in</strong>volves formal peace talks, currently underway <strong>in</strong> Geneva,while Track II addresses grassroots <strong>and</strong> civil society efforts that may both <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>and</strong> be affected byofficial processes.54 UN Women. “Gender Ma<strong>in</strong>stream<strong>in</strong>g – Concepts <strong>and</strong> Def<strong>in</strong>itions”. Web. 15 Dec. 2011.17

Civil society: The Civil Society Index def<strong>in</strong>es civil society as “the arena, outside of the family, the state,<strong>and</strong> the market where people associate to advance common <strong>in</strong>terests.” 55 This def<strong>in</strong>ition <strong>in</strong>corporatesnongovernmental organizations, religious <strong>in</strong>stitutions, community groups, media, political parties, tradeunions. Tak<strong>in</strong>g civil society as a broad concept provides a wider lens with which to exam<strong>in</strong>e routes toenhanc<strong>in</strong>g gender-balanced political participation of IDPs.Research Approach <strong>and</strong> MethodsOur research <strong>and</strong> analysis is grounded <strong>in</strong> a human rights-based approach (HRBA), look<strong>in</strong>g specifically atthe rights codified <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational human rights norms <strong>and</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ards related to participation <strong>in</strong> publiclife as affected by IDP status <strong>and</strong> gender. HRBA, as def<strong>in</strong>ed by the United Nations Office of HighCommissioner for Human Rights, is a “conceptual framework for the process of human developmentthat is normatively based on <strong>in</strong>ternational human rights st<strong>and</strong>ards <strong>and</strong> operationally directed topromot<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> protect<strong>in</strong>g human rights.” 56 It seeks to analyze “<strong>in</strong>equalities which lie at the heart ofdevelopment problems <strong>and</strong> redress discrim<strong>in</strong>atory practices <strong>and</strong> unjust distributions of power thatimpede development progress,” with the ultimate goal of empower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals to participate <strong>in</strong>politics <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>fluence governance 57 . Follow<strong>in</strong>g the HRBA, we assume that a participatory approach leadsto policies that are more reflective of rights-holders’ needs <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests. Therefore, we have conductedour analysis with an eye to opportunities to exp<strong>and</strong> the scope <strong>and</strong> quality of IDPs’ political participation.HRBA requires the identification of a set of rights-holders endowed with certa<strong>in</strong> rights codified <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>ternational human rights st<strong>and</strong>ards, <strong>and</strong> correspond<strong>in</strong>g duty-bearers, whose role is to provide theconditions that will enable rights-bearers to claim their rights. We consider IDPs as a whole to be ourprimary rights-holders of concern. We f<strong>in</strong>d this approach to be useful <strong>and</strong> appropriate <strong>in</strong> this contextbecause it helps to clarify IDPs as possess<strong>in</strong>g specific rights as residents <strong>and</strong> citizens of <strong>Georgia</strong>, as men<strong>and</strong> women, as displaced <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>and</strong> displaced communities. 58 HRBA is most often used to constructa framework for development or humanitarian <strong>in</strong>terventions. This assessment tool is appropriate forthis project given our goals of empower<strong>in</strong>g IDPs to enhance their capacity with a view of greaterrepresentation <strong>in</strong> policymak<strong>in</strong>g.The HRBA is especially mean<strong>in</strong>gful <strong>in</strong> the context of <strong>in</strong>ternal displacement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> because itunderscores the need to shift perceptions of IDPs (from with<strong>in</strong> the IDP community <strong>and</strong> without) frompassive beneficiaries to capable actors. HRBA identifies them as agents of their own empowerment <strong>and</strong>asks how they can claim their <strong>in</strong>herent rights. This underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of IDPs differs significantly, <strong>and</strong> webelieve positively, from the perception of IDPs as dependents with needs that must be fulfilled. Thisview is common across <strong>Georgia</strong>n society <strong>and</strong> among some members of the <strong>in</strong>ternational community <strong>and</strong>55Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy <strong>and</strong> Development <strong>and</strong> CIVICUS, 16.56 United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Frequently Asked Questions on a Human Rights-BasedApproach to Development Cooperation, HR/PUB/06/8 (2006), 1557 Ibid.58 Although we consider IDPs to be a s<strong>in</strong>gle rights-bear<strong>in</strong>g group <strong>in</strong> this context, as noted above we purposely exam<strong>in</strong>e IDPheterogeneity under the HRBA framework as well.18

even IDPs themselves. The HRBA seeks to counter this perspective, while also l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g IDPs as rightsholderswith the <strong>Georgia</strong>n government <strong>and</strong> other stakeholders as duty-bearers.Gender equality is a central consideration with<strong>in</strong> HRBA. In this case, we seek to promote men’s <strong>and</strong>women’s equal access to opportunities for participation, so a gender-based approach is also afoundation of our research. UNDP def<strong>in</strong>es a gender-based analysis as the “collection <strong>and</strong> analysis of sexdisaggregated<strong>in</strong>formation” based on the assumption that women <strong>and</strong> men have different experiences,knowledge, talents <strong>and</strong> needs. 59 Gender analysis systematically explores these differences as expressedthrough avenues such as participation, resources, norms <strong>and</strong> values, <strong>and</strong> rights so that policies,programs <strong>and</strong> projects can identify <strong>and</strong> meet the different needs of men <strong>and</strong> women. 60 Moreover, theyshould ensure that non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>in</strong> access to resources based on different aspects of identity.In this context, it was crucial to consider that men <strong>and</strong> women may experience displacement differentlydue to their gender; they may also face different needs, opportunities <strong>and</strong> barriers when it comes toparticipat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> civic life. Therefore, we have ma<strong>in</strong>streamed consideration of gender throughout ourresearch <strong>and</strong> analysis.To employ both of these approaches, the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>ternational human rights <strong>in</strong>struments (to which<strong>Georgia</strong> is a party or accepts as the UN Member State) <strong>and</strong> some of their relevant articles provide aframework for our analysis: 61• Universal Declaration of Human Rightso Article 2: Non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ation• International Covenant on Civil <strong>and</strong> Political Rightso Article 2: Non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ationo Article 3: Equal rights of men <strong>and</strong> womeno Article 25: Right to voteo Article 26: Equal protection without discrim<strong>in</strong>ation• European Convention on Human Rightso Article 14: Non-discrim<strong>in</strong>ationo Article 3 (Protocol 1): Right to hold free elections• Convention on the Elim<strong>in</strong>ation of All Forms of Discrim<strong>in</strong>ation Aga<strong>in</strong>st Womeno Article 2: States need to enact policy to elim<strong>in</strong>ate discrim<strong>in</strong>ationo Article 5: Modification of social <strong>and</strong> cultural norms to support gender equalityo Article 7: Support for women’s <strong>in</strong>volvement <strong>in</strong> political <strong>and</strong> public life59 UNDP. Quick Entry Po<strong>in</strong>ts to Women’s Empowerment <strong>and</strong> Gender Equality <strong>in</strong> Democratic Governance Clusters. 2007. 4.60 European Commission. A Guide to Gender Impact Assessment. 1998. 5.61 See Appendix C for a more detailed list of the relevant articles <strong>in</strong> these <strong>in</strong>struments.19

• United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace <strong>and</strong> Securityo Article 1: Increase representation of women at all decision-mak<strong>in</strong>g levels <strong>in</strong> conflictresolution <strong>and</strong> peace processeso Article 8: Adopt a gender perspective <strong>in</strong> peace agreements• The UN Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement 62 :This document provides the cornerstone of our analysis of the participation of IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>.The Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples comprise an <strong>in</strong>ternationally-recognized (though non-b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g) st<strong>and</strong>ard ofrights specific to IDPs <strong>and</strong> correspond<strong>in</strong>g duties of governments <strong>and</strong> other actors “provid<strong>in</strong>gassistance <strong>and</strong> protection to IDPs.” 63 The Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples def<strong>in</strong>e three “durable solutions” todisplacement: <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong> the place of displacement, 64 resettlement to another part of thecountry, <strong>and</strong> dignified safe return. The Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples name national authorities as theprimary duty-bearers with responsibility to “establish the conditions, as well as provide themeans” to make each of these solutions available for IDPs to choose freely. 65 Central to ourproject is the provision that national authorities <strong>and</strong> other duty-bearers make special efforts to“ensure the full participation of displaced persons <strong>in</strong> the plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> management of theirreturn, resettlement <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>tegration.” 66 The Government of <strong>Georgia</strong> notes the relevance of theGuid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples <strong>in</strong> its policies documents. However, it narrows the Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples’def<strong>in</strong>ition of IDPs fail<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>clude people displaced by natural disasters, focus<strong>in</strong>g only on thosefrom the conflict regions.Research ProcessWe determ<strong>in</strong>ed that a qualitative research strategy would allow us to ga<strong>in</strong> the most nuancedunderst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g IDPs’ political participation. While our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs cannot be taken asprov<strong>in</strong>g causation or as be<strong>in</strong>g representative of all IDPs <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>, the scope of our analysis supportsgreater underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of opportunities for greater <strong>and</strong> more effective <strong>in</strong>clusion of IDPs <strong>in</strong> policymak<strong>in</strong>g.In addition to desk research, our assessment is based on orig<strong>in</strong>al source materials gathered throughroughly 70 semi-structured <strong>and</strong> spontaneous personal <strong>in</strong>terviews <strong>and</strong> five focus groups. Team membersconducted two field visits to <strong>Georgia</strong> total<strong>in</strong>g 24 days, with fieldwork done <strong>in</strong> Tbilisi, Zugdidi, Koda,62 Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement. Brook<strong>in</strong>gs – LSE Project on Internal Displacement. Web. 15 Dec. 2011.63 Ibid.64 We adopt an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the term “<strong>in</strong>tegration” that is specific to the <strong>Georgia</strong>n context. The discourse <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> onthis topic ranges from view<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tegration as mutually exclusive with IDPs’ return to their former home, while the more recentview presented <strong>in</strong> the state strategy suggests that these two concepts can also be complementary. 64 We also differentiatebetween <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> assimilation. The former term usually refers to migrant groups both adjust<strong>in</strong>g to life <strong>in</strong> their newenvironment <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g their identity, while the latter generally refers to a process whereby the dist<strong>in</strong>guish<strong>in</strong>g markersbetween migrant groups <strong>and</strong> host societies fall away. 64 These issues become relevant when consider<strong>in</strong>g the current situation ofprotracted displacement <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong> <strong>and</strong> its effects on the ways <strong>in</strong> which <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>and</strong> assimilation play a role <strong>in</strong> IDPs lives.These issues also relate to the extent to which the broader society views displaced persons as a dist<strong>in</strong>ct social group.65 United Nations Office for the Coord<strong>in</strong>ation of Humanitarian Affairs. Guid<strong>in</strong>g Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples on Internal Displacement. 2004. 14.66 Ibid.20

Karaleti settlement, <strong>and</strong> Potskho-Etseri. The team also conducted <strong>in</strong>terviews with experts <strong>in</strong> New York<strong>and</strong> Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C., along with stakeholders based <strong>in</strong> Europe.Interviewees <strong>in</strong>cluded development <strong>and</strong> human rights practitioners <strong>and</strong> academics with expertise onIDPs, women’s rights, political participation, governance, <strong>and</strong> peacebuild<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Georgia</strong>. Dur<strong>in</strong>g our fieldvisits, we spoke with a wide variety of relevant stakeholders, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g government officials <strong>and</strong> otherpolitical figures, such as representatives of the Abkhaz government-<strong>in</strong>-exile; analysts <strong>and</strong> academics;staff of local <strong>and</strong> national IDP <strong>and</strong> women’s NGOs; <strong>and</strong> representatives of <strong>in</strong>ternational organizations<strong>and</strong> donors.Throughout our research we have sought to <strong>in</strong>clude the perspectives of IDPs themselves as key<strong>in</strong>formants. Therefore, a particular focus of our research has been gather<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>sight from differentiatedgroups of IDPs, represent<strong>in</strong>g men <strong>and</strong> women, both conflict regions, both waves of displacement, <strong>and</strong>various socio-economic backgrounds <strong>and</strong> levels of <strong>in</strong>tegration <strong>in</strong>to <strong>Georgia</strong>n society. We prioritized<strong>in</strong>terview<strong>in</strong>g IDPs represent<strong>in</strong>g demographics that are currently underrepresented <strong>in</strong> the literature, <strong>in</strong>particular IDPs liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> private accommodations.Additionally, team members organized a stakeholder roundtable discussion on our prelim<strong>in</strong>ary f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsat the end of our second field visit. The roundtable brought together <strong>in</strong>dividual IDPs, IDP activists <strong>and</strong>other representatives of civil society. They discussed challenges around empower<strong>in</strong>g IDP politicalparticipation that our research identified <strong>and</strong> debate recommendations for address<strong>in</strong>g the situation.Insights from this discussion have <strong>in</strong>formed this report as well.The majority of <strong>in</strong>terviews were conducted <strong>in</strong> English, with local <strong>in</strong>terpreters provid<strong>in</strong>g language supportwhen necessary. A list of all <strong>in</strong>terviewees who agreed to be identified <strong>in</strong> this report can be found <strong>in</strong> theAppendix.21