Managing salts in soil and irrigation water - GCSAA

Managing salts in soil and irrigation water - GCSAA

Managing salts in soil and irrigation water - GCSAA

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>R E S E A R C H<strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>An <strong>in</strong>tegrated approach helps super<strong>in</strong>tendents grow healthy turf.Sowmya (Shoumo) Mitra, Ph.D.KEY POINTS■ Multiple options allow super<strong>in</strong>tendentsto improve poorquality<strong>water</strong> or reduce itseffects on turfgrass.■ Calcium, particle aggregation<strong>and</strong> leach<strong>in</strong>g can all help thesuper<strong>in</strong>tendent deal with lowquality<strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>.■ Foliar fertilizers can replacenutrients lost to leach<strong>in</strong>g orother salt-reduction strategies.The quality <strong>and</strong> quantity of <strong>irrigation</strong><strong>water</strong> is becom<strong>in</strong>g a limit<strong>in</strong>g factor <strong>in</strong>ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g high-quality turf for golfcourses all across the United States. Manygolf courses are experienc<strong>in</strong>g salt problems.The global dem<strong>and</strong> for fresh potable<strong>water</strong> is doubl<strong>in</strong>g every 20 years, <strong>and</strong> golfcourse super<strong>in</strong>tendents are forced to seekalternative <strong>water</strong> sources (5).Effluent <strong>water</strong> is be<strong>in</strong>g considered asan alternative <strong>irrigation</strong> source, <strong>and</strong> alot of golf courses <strong>in</strong> the southwesternUnited States have started us<strong>in</strong>g recycled<strong>water</strong> (9). As golf course super<strong>in</strong>tendentsswitch to alternative <strong>water</strong>sources, they must use an <strong>in</strong>tegratedapproach <strong>and</strong> proper agronomic practicesbased on <strong>in</strong>dividual sites.Management practices should be basedon <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong> reportsfrom a particular location.Irrigation <strong>water</strong> testsThe follow<strong>in</strong>g items need to beexam<strong>in</strong>ed for sal<strong>in</strong>ity hazards from <strong>irrigation</strong><strong>water</strong>:• Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) oradjusted SAR (adj. SAR)• Electrical conductivity (EC)• Total dissolved solids (TDS)• Amount of sodium [Na + ], calcium[Ca ++ ], magnesium [Mg ++ ],carbonate [CO 3=], <strong>and</strong> bicarbonate[HCO 3- ] ions• Residual sodium carbonate (RSC): RSCis calculated by the follow<strong>in</strong>g equation:RSC = [CO 3=+ HCO 3- ] – [Ca+++ Mg ++ ]Note: The units must be expressed asmilliequivalents per liter. Generally, labsreport values <strong>in</strong> parts per million ormilligrams per liter. Such values mustbe divided by the equivalent weightto obta<strong>in</strong> milliequivalents per liter.Calcium sourceSoils with high amounts of sodiumwill tend to disperse <strong>soil</strong> particles <strong>and</strong>, asa result, reduce aeration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>filtration<strong>in</strong>to the <strong>soil</strong> profile (2). High carbonates<strong>and</strong> bicarbonates <strong>in</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong> willreact with the available calcium <strong>and</strong> magnesiumto form <strong>in</strong>soluble <strong>salts</strong>. In orderto avoid these problems with <strong>irrigation</strong><strong>water</strong> <strong>and</strong> amended <strong>soil</strong>s, which have ahigh exchangeable sodium percentage,we must add a soluble source of calcium.70 Golf Course Management ■ January 2001

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>R E S E A R C HPhotos courtesy of R.R. DuncanHigh rates of gypsum may be mixed <strong>in</strong>to sodic <strong>soil</strong>s to correct problems <strong>in</strong>troduced by poorquality<strong>water</strong>.Calcium can be added <strong>in</strong> formssuch as gypsum, limestone, dolomite,lime <strong>and</strong> so on. Gypsum is the mostcommon source, because it has littleeffect on the <strong>soil</strong> pH <strong>and</strong> has high <strong>water</strong>solubility. Gypsum is calcium sulfatedihydrate (CaSO 4 , 2H 2 O). Whengypsum comes <strong>in</strong> contact with <strong>soil</strong>solution, it generates calcium ions,which replace sodium from the <strong>soil</strong>exchange complex.The <strong>soil</strong> exchange complex has negativecharges, which are generated mostlyby clay <strong>and</strong> organic matter. Clay m<strong>in</strong>eralshave a negative charge caused bystructural substitution <strong>in</strong> their lattice(isomorphic substitution). Organicmatter, however, has negative charges onits surface as a result of dissociation ofthe carboxyl acid groups (-COOH) ofhumic <strong>and</strong> fulvic acids.The sodium sulfate (Na 2 SO 4 )formed <strong>in</strong> the <strong>soil</strong> must be removedfrom the <strong>soil</strong> profile by leach<strong>in</strong>g.Addition of polyvalent (more than onecharge) cations such as calcium <strong>and</strong>magnesium will flocculate the <strong>soil</strong>.These cations hold <strong>soil</strong> particles becausetheir charges form cationic bridges.Flocculation is a prerequisite for <strong>soil</strong>aggregation, <strong>and</strong> a well-aggregated <strong>soil</strong>forms <strong>water</strong>-stable aggregates. A wellaggregated<strong>soil</strong> has <strong>in</strong>creased porosity,aeration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>filtration.Gypsum requirementThe gypsum required by a particulargolf course depends on the quality of<strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>soil</strong>. The relativeamounts of sodium, calcium, magnesium,carbonate <strong>and</strong> bicarbonate determ<strong>in</strong>ethe amount of gypsum requiredto treat <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>.There are two ways to figurethe gypsum requirement: RSC <strong>and</strong>Eaton’s gypsum requirement (EGR).The RSC method takes <strong>in</strong>to accountthe amount of carbonate <strong>and</strong> bicarbonate<strong>in</strong> <strong>water</strong> compared to calcium<strong>and</strong> magnesium. It does not accountfor the sodium. Hence, it tends tounderestimate the gypsum requirement.This method is useful when theamount of carbonate <strong>and</strong> bicarbonateis high, but the amount of sodium islow compared to calcium <strong>and</strong> magnesium.The units must be <strong>in</strong> milliequivalentsper liter.Golf Course Management ■ January 2001 71

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>R E S E A R C HRSC methodRSC method = 234 × [CO 3=+ HCO 3- ]– [Ca+++ Mg ++ ].The results are reported <strong>in</strong> pounds of100 percent grade gypsum per acre foot of<strong>water</strong>. If we use a lower grade of gypsum,for example, 95 percent, then we need toadd the extra 5 percent to the value.Eaton’s gypsum requirementEGR is calculated based on sodium,calcium, magnesium, carbonate <strong>and</strong>bicarbonate. EGR is calculated by thefollow<strong>in</strong>g equation:Soil testThe major sources of salt problemscan be traced to <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>, culturalpractices (ma<strong>in</strong>ly fertilization) <strong>and</strong>salt <strong>water</strong> <strong>in</strong>trusion. Hence, when weplan to treat the problem, we have totreat the <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong> <strong>and</strong> alsoaddress the salt problem <strong>in</strong> the <strong>soil</strong>.The follow<strong>in</strong>g items need to beobserved for <strong>soil</strong> sal<strong>in</strong>ity hazards:• Sodium absorption ratio (SAR)• Electrical conductivity (EC)• Exchangeable sodium percentage(ESP)ESP is calculated by the follow<strong>in</strong>g equation:EGR = 234 × [a + b + c], wherea = 0.43 × Na + - (Ca ++ + Mg ++ )b = 0.7 × CO 3=+ HCO 3-c = 0.3.The results are reported <strong>in</strong> poundsof 100 percent grade gypsum per acrefoot of <strong>water</strong>. If we use a lower grade ofgypsum, for example 97 percent, thenwe need to add the extra 3 percent tothe value.ESP ( percent) = [Exchangeable sodium/Soil cation exchange capacity] × 100.The units for the amount of sodiumshould be <strong>in</strong> milliequivalents per liter.Acid <strong>in</strong>jectionMany golf course super<strong>in</strong>tendentshave started us<strong>in</strong>g acid-<strong>in</strong>jection systems,but they need to be careful <strong>in</strong>select<strong>in</strong>g the right tool to countersodium <strong>and</strong> bicarbonate (HCO - 3 ) hazards.Acid-<strong>in</strong>jection systems <strong>in</strong>clude theuse of sulfurous generators, sulfuricacid (H 2 SO 4 ), urea plus sulfuric acid(monocarbamide dihydrogensulfate) orphosphoric acid (H 3 PO 4 ) (1). Sulfurousgenerators use elemental sulfur <strong>and</strong> oxidizeit to SO 3 by burn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the presenceof oxygen. The SO 3 gas reacts with<strong>water</strong> to form sulfuric acid (H 2 SO 4 ).Sulfuric acid (H 2 SO 4 ) reacts withbicarbonates (HCO - 3 ) to form carbondioxide (CO 2 ), <strong>and</strong> hence removes thebicarbonates, which would have reactedwith Ca <strong>and</strong> Mg to form <strong>in</strong>soluble precipitates(3).H 2 SO 4 + HCO 3- → HSO4 - + H2 O + CO 2Seashore paspalum is the best choice for sites with poor-quality <strong>water</strong> <strong>in</strong> warm climates.Sulfur is added through burn<strong>in</strong>g sothat it will react with the lime alreadypresent <strong>in</strong> the <strong>soil</strong> to form gypsum(CaSO 4 ). However, gypsum will notform if excess lime is not present. Even72 Golf Course Management ■ January 2001

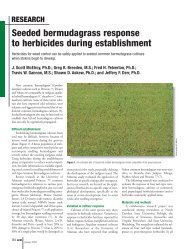

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>when gypsum is added to the <strong>soil</strong>, thegypsum may revert to <strong>in</strong>soluble lime(CaCO 3 ) <strong>in</strong> the presence of excessHCO 3- <strong>and</strong> CO3 = (3). Hence, <strong>in</strong> orderto use sulfur to form gypsum, it is necessarytoremove excessive HCO 3- <strong>and</strong>CO 3=. Super<strong>in</strong>tendents should be verycareful when they use sulfur burners,because, under anaerobic conditions,reduced forms of sulfur may lead toblack-layer problems later on. Therefore,sulfur products should be used <strong>in</strong>areas that are well aerated <strong>and</strong> have no<strong>in</strong>filtration problems.Another reason super<strong>in</strong>tendents useacid-<strong>in</strong>jection systems is to reduce <strong>soil</strong>pH. Unfortunately <strong>soil</strong> pH cannot bechanged easily by such acid applications,because <strong>soil</strong> has a huge buffer<strong>in</strong>gcapacity. Reduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>soil</strong> pH is very difficultor even impossible <strong>in</strong> highlybuffered, calcareous <strong>soil</strong>s (3). It is muchmore practical <strong>and</strong> also less expensive toreduce <strong>soil</strong> pH by spread<strong>in</strong>g sulfur overdry <strong>soil</strong> as an amendment.A few super<strong>in</strong>tendents use acid <strong>in</strong>jection<strong>in</strong> order to prevent the precipitationof calcium <strong>and</strong> magnesium carbonates<strong>in</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> plumb<strong>in</strong>g, but thisproblem can be solved with muchcheaper materials. A weak organic acid<strong>and</strong> a weak organic base comb<strong>in</strong>ationwill take care of the problem, <strong>and</strong> thesetypes of materials are readily available<strong>and</strong> relatively <strong>in</strong>expensive.on threshold EC values, but f<strong>in</strong>al selectionshould be made after check<strong>in</strong>g thegrowth vs. EC level, threshold EC valuesfor 50 percent growth reduction ofshoot <strong>and</strong> root. Seashore paspalum hashigh sal<strong>in</strong>ity tolerance, can tolerate<strong>water</strong>logg<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> has a low <strong>soil</strong>-oxygenrequirement (4). These attributes makeseashore paspalum an ideal turfgrasscultivar for warm-climate golf coursesfac<strong>in</strong>g severe sal<strong>in</strong>ity problems.Leach<strong>in</strong>gLeach<strong>in</strong>g of excess <strong>salts</strong> is the mostimportant step <strong>in</strong> manag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>salts</strong>.Without leach<strong>in</strong>g, the replaced sodium<strong>and</strong> the excess <strong>salts</strong> beyond the rootzone plague turf. It is difficult to leachpush-up greens or other parts of thegolf course that have f<strong>in</strong>er <strong>soil</strong> texture.Leach<strong>in</strong>g is more of an art, which asuper<strong>in</strong>tendent learns through experience<strong>and</strong> knowledge about the <strong>soil</strong> texture,the amount of <strong>water</strong> required orthe time needed for a particular green.If we try to underst<strong>and</strong> the movementof <strong>water</strong> through a <strong>soil</strong> profile, wewill f<strong>in</strong>d that, accord<strong>in</strong>g to the laws ofhydraulic conductivity, a particular <strong>soil</strong>horizon will release <strong>water</strong> as soon as itreaches field capacity. Water movesAtomic weightsR E S E A R C HSelection of turfgrassProper turfgrass selection is animportant management tool when sal<strong>in</strong>ityproblems are anticipated. Differentcultivars have differential responses tosal<strong>in</strong>ity levels. For example, commoncentipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides)is sensitive to salt levels, whereasseashore paspalum (Paspalum vag<strong>in</strong>atum)can tolerate higher sal<strong>in</strong>ity levels(14 decisiemens per meter) (1). Salt-sensitiveplants (glycophytes) should bereplaced with halophytes. When select<strong>in</strong>ga turfgrass species, it is advisable tocheck the growth versus EC curves forthat particular species. Turfgrass selectionfor sal<strong>in</strong>ity tolerance is often basedFor some calculations of <strong>water</strong> quality, units must be expressed as millequivalentsper liter. Generally, labs report values <strong>in</strong> parts per million or milligramsper liter. Such values need to be divided by the equivalent weight toobta<strong>in</strong> millequivalents per liter.Ions Atomic/molecular Equivalentweight (grams) Valence weight (meq/liter)Ca ++ 40 2 20Mg ++ 24 2 12Na + 23 1 23HCO 3- 61 1 61CO 3=60 2 30Golf Course Management ■ January 2001 73

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>R E S E A R C Hthrough the <strong>soil</strong> profile <strong>in</strong> concentriccircles. With<strong>in</strong> a particular <strong>soil</strong> horizon,<strong>water</strong> moves laterally (<strong>in</strong>stead of immediatelymov<strong>in</strong>g downward) until thehorizon reaches field capacity. For thisreason, deep, <strong>in</strong>frequent <strong>irrigation</strong> ispreferred over light, frequent <strong>irrigation</strong>.For a particular golf course, it isimportant to determ<strong>in</strong>e the amount of<strong>water</strong> required to flush the greens. Thefraction of <strong>water</strong> that <strong>in</strong>filtrates the <strong>soil</strong>surface <strong>and</strong> passes through the rootzone is called the leach<strong>in</strong>g fraction (LF).For practical reasons, the LF is calculatedas:LF = EC W / EC DW,where EC W is the electrical conductivity(EC) of the <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>, <strong>and</strong> EC DWis the EC of the dra<strong>in</strong>age <strong>water</strong>. Hence,the salt content of dra<strong>in</strong>age <strong>water</strong> can beadjusted by adjust<strong>in</strong>g the LF.The leach<strong>in</strong>g requirement (LR) isused to represent the m<strong>in</strong>imum amountof <strong>water</strong> that must pass through theroot zone to control <strong>salts</strong> to an acceptablelevel (2). The LR is expressed <strong>in</strong>terms of the percentage of <strong>water</strong> thatneeds to be applied to meet the evapotranspiration(ET) needs of a particularturfgrass.The oldest method of calculation (7)uses the ratio of EC of <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>(EC W ) to the sal<strong>in</strong>ity tolerance of the turfgrassbe<strong>in</strong>g grown (EC TS ) to determ<strong>in</strong>ethe amount of <strong>water</strong> that must be addedto leach excess <strong>salts</strong> from the root zone:LR = [EC W / EC TS ] × 100,where the EC TS is the threshold valuethat a particular turfgrass can tolerate.For example, if we are irrigat<strong>in</strong>g agolf course with ma<strong>in</strong>ly Kentucky bluegrass(Poa pratensis) with an EC TS valueof 3.0 decisiemens per meter from a<strong>water</strong> source hav<strong>in</strong>g an EC W value of1.5 decisiemens per meter, the leach<strong>in</strong>grequirement can be calculated as:LR = [1.5 / 3.0] × 100 = 50%In other words, grow<strong>in</strong>g Kentuckybluegrass with this <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>requires an additional 50 percent <strong>irrigation</strong>Salt toleranceTurfgrass species vary <strong>in</strong> their tolerance of sal<strong>in</strong>e conditions. Greater electrical conductivity (EC) tolerance <strong>in</strong>dicatesgreater salt tolerance (4).EC range caus<strong>in</strong>gCommon name Scientific name Threshold EC range 50% growth reductionAnnual bluegrass Poa annua 0-3 —Rough bluegrass Poa trivialis 0-3 —Kentucky bluegrass Poa pratensis 0-6 3-30Centipedegrass Eremochloa ophiuroides 0-3 8-9Common bermudagrass Cynodon dactylon 0-12 12-32Tall fescue Festuca arund<strong>in</strong>acea 5-10 8-12Perennial ryegrass Lolium perenne 3-10 8-10St. August<strong>in</strong>egrass Stenotaphrum secundatum 0-18 22-44Seashore paspalum Paspalum vag<strong>in</strong>atum 0-20 18-49Creep<strong>in</strong>g bentgrass Agrostis palustris 0-10 8Zoysiagrass Zoysia species 0-11 4-4074 Golf Course Management ■ January 2001

GCM - January 2001 - Research - <strong>Manag<strong>in</strong>g</strong> <strong>salts</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong><strong>water</strong> to leach <strong>salts</strong> beyond the root zone.MicroorganismsProper leach<strong>in</strong>g requires improv<strong>in</strong>gthe <strong>soil</strong> structure. Structure build<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>volves two different but complementaryprocesses. The coherence of particles<strong>in</strong> the structural units or aggregatesrequires the presence of cement<strong>in</strong>g substances<strong>and</strong> the mechanical forces thatdis<strong>in</strong>tegrate <strong>and</strong> mold the <strong>soil</strong> mass <strong>in</strong>tostable aggregates (7).Microorganisms can b<strong>in</strong>d <strong>soil</strong> particlesby adhesion of extracellular polymers<strong>and</strong> enzymes <strong>and</strong> by charge <strong>in</strong>teractions(6). Several researchers have<strong>in</strong>vestigated the role of microorganisms<strong>in</strong> enhanc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>soil</strong> aggregation. Somemicroorganisms secrete polysaccharides,which help <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong> aggregation,<strong>and</strong> dur<strong>in</strong>g the past 40 years, study ofmicrobial polysaccharides has dom<strong>in</strong>atedthe field (7). Microbial polysaccharidesmay be divided <strong>in</strong>to threegroups accord<strong>in</strong>g to their morphologicallocalization:• Extracellular surface polysaccharideslocated outside the cell wall <strong>and</strong> frequentlytermed “capsular polysaccharides”• Cell-wall polysaccharides• Somatic or <strong>in</strong>tracellular polysaccharideslocated <strong>in</strong>side the cytoplasmicmembrane (11)Researchers have reported that certa<strong>in</strong>species of Bacillus, Leuconostoc <strong>and</strong>Mycor secrete polysaccharides that are<strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> b<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g <strong>soil</strong> particles <strong>in</strong>to<strong>water</strong>-stable aggregates (7, 8). Microbialpolysaccharides provide the glue thatcements <strong>soil</strong> particles together, whereasfungal mycelia physically encompass(like a rope) the particles to <strong>in</strong>creasetheir physical association.Soil management is one of the mostimportant factors <strong>in</strong>fluenc<strong>in</strong>g the structureof <strong>soil</strong>s. The <strong>in</strong>teraction of managementwith <strong>soil</strong> biochemistry <strong>and</strong> <strong>soil</strong>microbiology determ<strong>in</strong>es the extent of<strong>soil</strong> aggregation. Soil mean aggregate sizehas been correlated with <strong>soil</strong> monosaccharidecontent, total <strong>soil</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> content<strong>and</strong> extractable humic substances (10).Hence, the addition of monosaccharides<strong>and</strong> prote<strong>in</strong> is recommended.In conclusion, a golf course super<strong>in</strong>tendentshould develop an <strong>in</strong>tegratedsalt-management program <strong>in</strong> order togrow healthy turf <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the follow<strong>in</strong>gstrategies:• Us<strong>in</strong>g or add<strong>in</strong>g a soluble source ofcalcium <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong>• Increas<strong>in</strong>g <strong>soil</strong> aggregation toimprove aeration <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>filtration• Leach<strong>in</strong>g excess <strong>salts</strong> <strong>and</strong> displacedsodium from the root zone• Apply<strong>in</strong>g foliar nutrients to replenishthe leached-out nutrients ■AcknowledgmentHelp from John M. Doyle is highly appreciated.Literature cited1. Carrow, R.N., <strong>and</strong> R.R. Duncan. 1998. Saltaffectedturfgrass sites: Assessment <strong>and</strong> management,Ann Arbor Press, Chelsea, Mich.2. Carrow, R.N., R.R. Duncan <strong>and</strong> M. Huck.1999. Treat<strong>in</strong>g the cause, not symptoms.USGA Green Section Record 37(6):11-15.3. Christians, N. 1999. Why <strong>in</strong>ject acid <strong>in</strong>to<strong>irrigation</strong> <strong>water</strong>? Golf Course Management67(6):52-56.4. Duncan, R.R., <strong>and</strong> R.N. Carrow. 2000. Soonon golf courses: New seashore paspalums.Golf Course Management 68(5):65-67.5. Duncan, R.R., R.N. Carrow <strong>and</strong> M. Huck.2000. Effective use of sea<strong>water</strong> <strong>irrigation</strong> onturfgrass. USGA Green Section Record38(1):11-17.6. Fletcher, M., M. Latham, J. Lynch <strong>and</strong> P.R.Rutter. 1980. The characteristics of <strong>in</strong>terfaces<strong>and</strong> their role <strong>in</strong> microbial attachment.p. 67-78. In: R.C.W. Berkley, J.M. Lynch, J.Mell<strong>in</strong>g, P.R. Rutter <strong>and</strong> B. V<strong>in</strong>cent (eds.),Microbial adhesion to surfaces. EllisHorwood Limited, Chichester, Engl<strong>and</strong>.7. Griffiths, E. 1965. Micro-organisms <strong>and</strong> <strong>soil</strong>structure. Biological Review 40:129-142.8. Harris, R.F., C. Chesters, O.N. Allen <strong>and</strong> O.J.Attoe. 1964. Mechanisms <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> <strong>soil</strong>aggregate stabilization by fungi <strong>and</strong> bacteria.Soil Science Society Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs 24:529-532.9. Huck, M., R.N. Carrow <strong>and</strong> R.R. Duncan.2000. Effluent <strong>water</strong>: Nightmare or dreamcome true? USGA Green Section Record38(2):15-29.10. Martens, D.A. 2000. Management <strong>and</strong> cropresidue <strong>in</strong>fluence <strong>soil</strong> aggregate stability.Journal of Environmental Quality 29:723-727.11. Stacey, M., <strong>and</strong> S.A. Barker. 1960.Polysaccharides of micro-organisms.Clarendon Press, Oxford.Sowmya (Shoumo) Mitra, Ph.D., is product managerfor Eco Soil Systems Inc.R E S E A R C HGolf Course Management ■ January 2001 75