Late-season bermudagrass nutrition and cold tolerance ... - GCSAA

Late-season bermudagrass nutrition and cold tolerance ... - GCSAA

Late-season bermudagrass nutrition and cold tolerance ... - GCSAA

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

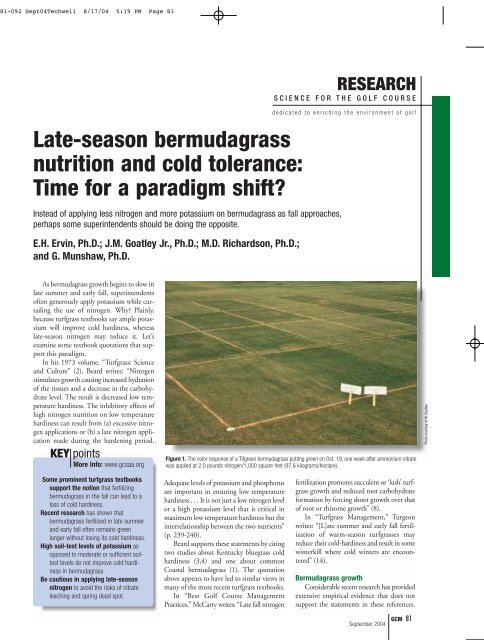

081-092 Sept04Techwell 8/17/04 5:19 PM Page 81<strong>Late</strong>-<strong>season</strong> <strong>bermudagrass</strong><strong>nutrition</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>cold</strong> <strong>tolerance</strong>:Time for a paradigm shift?Instead of applying less nitrogen <strong>and</strong> more potassium on <strong>bermudagrass</strong> as fall approaches,perhaps some superintendents should be doing the opposite.E.H. Ervin, Ph.D.; J.M. Goatley Jr., Ph.D.; M.D. Richardson, Ph.D.;<strong>and</strong> G. Munshaw, Ph.D.RESEARCHSCIENCE FOR THE GOLF COURSEdedicated to enriching the environment of golfAs <strong>bermudagrass</strong> growth begins to slow inlate summer <strong>and</strong> early fall, superintendentsoften generously apply potassium while curtailingthe use of nitrogen. Why? Plainly,because turfgrass textbooks say ample potassiumwill improve <strong>cold</strong> hardiness, whereaslate-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen may reduce it. Let’sexamine some textbook quotations that supportthis paradigm.In his 1973 volume, “Turfgrass: Science<strong>and</strong> Culture” (2), Beard writes: “Nitrogenstimulates growth causing increased hydrationof the tissues <strong>and</strong> a decrease in the carbohydratelevel. The result is decreased low temperaturehardiness. The inhibitory effects ofhigh nitrogen <strong>nutrition</strong> on low temperaturehardiness can result from (a) excessive nitrogenapplications or (b) a late nitrogen applicationmade during the hardening period.KEY pointsMore Info: www.gcsaa.orgFigure 1. The color response of a Tifgreen <strong>bermudagrass</strong> putting green on Oct. 19, one week after ammonium nitratewas applied at 2.0 pounds nitrogen/1,000 square feet (97.6 kilograms/hectare).Photo courtesy of M. GoatleySome prominent turfgrass textbookssupport the notion that fertilizing<strong>bermudagrass</strong> in the fall can lead to aloss of <strong>cold</strong> hardiness.Recent research has shown that<strong>bermudagrass</strong> fertilized in late summer<strong>and</strong> early fall often remains greenlonger without losing its <strong>cold</strong> hardiness.High soil-test levels of potassium asopposed to moderate or sufficient soiltestlevels do not improve <strong>cold</strong> hardinessin <strong>bermudagrass</strong>.Be cautious in applying late-<strong>season</strong>nitrogen to avoid the risks of nitrateleaching <strong>and</strong> spring dead spot.Adequate levels of potassium <strong>and</strong> phosphorusare important in ensuring low temperaturehardiness . . . It is not just a low nitrogen levelor a high potassium level that is critical inmaximum low temperature hardiness but theinterrelationship between the two nutrients”(p. 239-240).Beard supports these statements by citingtwo studies about Kentucky bluegrass <strong>cold</strong>hardiness (3,4) <strong>and</strong> one about commonCoastal <strong>bermudagrass</strong> (1). The quotationabove appears to have led to similar views inmany of the more recent turfgrass textbooks.In “Best Golf Course ManagementPractices,” McCarty writes: “<strong>Late</strong> fall nitrogenfertilization promotes succulent or ‘lush’ turfgrassgrowth <strong>and</strong> reduced root carbohydrateformation by forcing shoot growth over thatof root or rhizome growth” (8).In “Turfgrass Management,” Turgeonwrites: “[L]ate summer <strong>and</strong> early fall fertilizationof warm-<strong>season</strong> turfgrasses mayreduce their <strong>cold</strong>-hardiness <strong>and</strong> result in somewinterkill where <strong>cold</strong> winters are encountered”(14).Bermudagrass growthConsiderable recent research has providedextensive empirical evidence that does notsupport the statements in these references.September 2004GCM 81

081-092 Sept04Techwell 8/17/04 5:20 PM Page 82RESEARCHBefore we review this evidence, let’s frame thediscussion by reviewing <strong>bermudagrass</strong> growthduring the hardening period. Specifically, is itreasonable to think that lush shoot growthcan be promoted on transition zone<strong>bermudagrass</strong> (Cynodon species) once hardeningtemperatures are occurring? What arethese temperatures?When average daytime temperatures ([dailylow + daily high]/2) drop below 60 F (15.6 C),<strong>bermudagrass</strong> growth slows dramatically, withleaf discoloration (<strong>and</strong> the onset of dormancy)occurring in earnest once they drop below50 F (10 C) (5). In an upper transition zone climatesuch as in Roanoke, Va., average temperaturesof 60 F (15.6 C) are reached aroundSept. 30, with the first hard frost occurringabout Oct. 15, leading to almost complete leaftissue browning by early November.Thus, this mid-September to early-November hardening period is when textbooksadvise greatly reducing or actuallyeliminating the use of nitrogen. How does<strong>bermudagrass</strong> respond to the lower temperatures<strong>and</strong> shorter days of this period? Untilone or two hard frosts have occurred, the<strong>bermudagrass</strong> is still green <strong>and</strong> photosynthesizing,but little leaf elongation is occurring.But where is this photosynthate going?We contend that, as in cool-<strong>season</strong> grassesin late fall, most photosynthate is goingtoward root, stolon <strong>and</strong> rhizome growth orstorage. During this hardening period, itwould be almost impossible to promote alarge flush of succulent growth with an applicationof soluble nitrogen fertilizer. Try it, <strong>and</strong>the result is most often a greening responsewithout significant vertical growth.If the turf remains green later in the fall,the results should be greater photosynthesis<strong>and</strong> net energy gain. Loss of this re-greenedleaf tissue to a hard frost most likely has littleconsequence for overwintering becausethe status of the stem tissue (crowns, stolons<strong>and</strong> rhizomes) determines winter survival.Based on this reasoning, we hypothesizethat applying nitrogen late in the <strong>season</strong> inthe transition zone on <strong>bermudagrass</strong> that hasnot been overseeded will:• enhance color retention before frost events• encourage re-greening after mild frostevents• have no effect on <strong>cold</strong> hardiness• promote early spring green-upBelow we present supporting data fromfour late-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen studies conductedover the last 15 years.Study 1: Schmidt <strong>and</strong> ChalmersAt the Virginia Tech Turfgrass ResearchCenter in Blacksburg, mature Tifgreen<strong>bermudagrass</strong> was managed at 0.625 inch(15.88 millimeters) on a silt loam (pH 6.2<strong>and</strong> moderately high soil-test level of potassiumat 274 pounds/acre [307.1 kilograms/hectare]).[Researchers (5) havepresented the following potassium sufficiencyrankings: very low = 0-60 pounds/acre (0-67.3 kilograms/hectare); low = 61-120pounds/acre (67.3-134.5 kilograms/hectare);moderate = 121-280 pounds/acre (135.6-313.8 kilograms/hectare); high = greater than280 pounds/acre (313.8 kilograms/hectare).]The <strong>bermudagrass</strong> was treated with 0, 2.5pounds or 5.0 pounds nitrogen/1,000 squarefeet (0, 122.1 or 244.1 kilograms/hectare)from urea in split applications on Aug. 30<strong>and</strong> Sept. 27 of 1989, 1990 <strong>and</strong> 1991.The results in Table 1 clearly show thatlate-summer through early-fall nitrogenapplications to Tifgreen <strong>bermudagrass</strong>, amoderately winter-hardy cultivar, providedextended color in fall 1989. Similar resultswere found in 1990 <strong>and</strong> 1991. At no timeduring the three years of the study was<strong>bermudagrass</strong> recovery from dormancyimpaired because of late-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen(13). This was true even though conditionsin December 1989 were unusually <strong>cold</strong>,with a record low for Dec. 23 of -10 F(-23.3 C). Temperatures were normal inBlacksburg, Va., during the winters of 1990-1991 <strong>and</strong> 1991-1992.Study 2: Goatley et al.Mature Tifgreen <strong>bermudagrass</strong>, managedat 0.18 inch (4.57 millimeters) on aloam (pH 6.0 <strong>and</strong> a high soil-test level ofpotassium of 300 pounds/acre [336.3kilograms/hectare]) in Starkville, Miss.,received 0, 1.0 or 2.0 pounds nitrogen/1,000 square feet (0, 48.8 or 97.6 kilograms/hectare)from ammonium nitrate<strong>and</strong> 0, 0.8 or 2.0 pounds potassium (0, 39.1or 97.6 kilograms/hectare) from potassiumchloride (in all combinations) during the secondweek of October in 1989, 1990 <strong>and</strong>1991. On this soil, which contained sufficientsoil-available potassium (5), fertilizingwith potassium did not measurably change<strong>bermudagrass</strong> color or levels of total nonstructuralcarbohydrate (TNC) at any timefor any level.LATE NITROGEN ON TIFGREENNitrogen application rate 1989 color rating (9 = darkest) % greenhouse regrowth*Pounds/1,000 sq. ft. Kilograms/hectare Oct. 3 Oct. 16 Oct. 23 Feb. 15, 1990Control (no nitrogen applied) 5.8 b 4.4 b 4.3 c 28.6 a2.5 122.1 7.2 a 5.3 a 4.9 b 24.7 a5.0 244.1 7.3 a 5.3 a 6.3 a 26.1 a*Percentage of greenhouse regrowth of dormant plugs that are subjected to controlled freezing to 23 F (-5 C). Plugs were sampled <strong>and</strong> frozen on Jan. 25, 1989.Table 1. Influence of 1989 late-summer <strong>and</strong> early-fall applications of nitrogen on fall color <strong>and</strong> <strong>cold</strong> hardiness of Tifgreen <strong>bermudagrass</strong>.Values followed by the same letters within a column are not significantly different from each other.82 GCMSeptember 2004

081-092 Sept04Techwell 8/17/04 5:20 PM Page 83RESEARCHThe only measurable response was a linearincrease in concentrations of leaf-tissuepotassium as potassium applications increasedfrom 0 to 2.0 pounds/1,000 square feet (0 to97.6 kilograms/hectare). However, the nitrogenprovided longer fall color retention(Figure 1) <strong>and</strong> quicker spring green-upwithout reducing rhizome TNC levels inwinter or early spring (Table 2). The dataindicate that the 1-pound rate was sufficientfor enhanced color retention <strong>and</strong> green-up.No winterkill occurred in the field during thethree years of the study, even following anunusually <strong>cold</strong> spell in late December 1989.(7). The winters of 1990-1991 <strong>and</strong> 1991-1992 were normal.Study 3: RichardsonIn the third study, mature Tifway<strong>bermudagrass</strong> was managed at 0.5 inch(12.7 millimeters) on a silt loam (pH 6.4,with phosphorus <strong>and</strong> potassium levelsmaintained at sufficiency levels according tosoil tests) at the University of ArkansasResearch <strong>and</strong> Extension Center in Fayetteville(1998-1999) <strong>and</strong> at Springdale (Ark.)Country Club (1999-2000). Both sitesreceived either no nitrogen after Aug. 1 or 1.0pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (48.8 kilograms/hectare)(from urea) on Aug. 15 <strong>and</strong> onCOLOR AND RHIZOME TNC, 1991-1992Nitrogen rateRating date Control (no nitrogen applied) 1 pound/1,000 sq. ft. 2 pounds/1,000 sq. ft.(48.8 kilograms/hectare) (97.6 kilograms/hectare)ColorColor rating (9 = darkest)Oct. 17, 1991 5.3 6.2* 6.3*Oct. 31, 1991 5.8 7.1* 7.3*April 6, 1992 6.3 6.9* 6.8*RhizomesRhizome TNC (grams/kilogram)December 1991 14.2 14.4 13.2March 1992 14.6 14.2 13.6*Significantly different from the control.Table 2. Tifgreen <strong>bermudagrass</strong> color ratings <strong>and</strong> rhizome total nonstructural carbohydrate (TNC) levels during the 1991-1992 winter period.COLOR AND FREEZING TOLERANCENitrogen application datesTurf color (9 = darkest)September October November AprilNone after Aug. 1 (control) 6.2 5.8 4.5 4.5Aug. 15 <strong>and</strong> Sept. 15 6.8 6.3 6.1* 5.7*% rhizome survival following freezing, 199928 F (-2.2 C) 25 F (-3.9 C) 21 F (-6.1 C) 18 F (-7.8 C)None after Aug. 1 (control) 53.6 49.7 42.2 0.0Aug. 15 <strong>and</strong> Sept. 15 53.4 44.4 38.5 0.0*Significantly different from the control.Table 3. Fall <strong>and</strong> spring color ratings of Tifway <strong>bermudagrass</strong> <strong>and</strong> rhizome freezing <strong>tolerance</strong> as affected by late-summer nitrogen applications.September 2004GCM 83

081-092 Sept04Techwell 8/17/04 5:21 PM Page 84RESEARCHSept. 15. Both winters of the study (1998-1999 <strong>and</strong> 1999-2000) were mild for theregion, <strong>and</strong> no winter injury was observed inany of the plots. Thus, controlled freezing testswere used to determine the low temperaturesurvival of field-harvested rhizomes. Additionallate-summer nitrogen enhanced fall colorretention <strong>and</strong> spring green-up without affecting<strong>cold</strong> hardiness, as determined by rhizomesurvival after controlled freezing (11) (Table 3).Study 4: Munshaw <strong>and</strong> ErvinThis study used two-year-old Tifway<strong>bermudagrass</strong> managed at 0.63 inch (16.0millimeters) on a silt loam (pH 6.8 <strong>and</strong>medium-low soil-test levels of potassium of120 pounds/acre [134.5 kilograms/hectare])at the Virginia Tech Turfgrass ResearchCenter in Blacksburg. All plots received 1.0pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (48.8kilograms/hectare) monthly from Maythrough July in 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2002. BeginningAug. 15 of each year, the nitrogen treatmentreceived additional nitrogen from ammoniumnitrate at 1.0 pound nitrogen/1,000square feet (48.8 kilograms/hectare) everythree weeks, with the last application aboutOct. 17. Therefore, annual nitrogen rates forthe control were 4.0 pounds/1,000 squarefeet (195.3 kilograms/hectare), <strong>and</strong> the nitrogentreatments received 7.0 pounds/1,000square feet (341.8 kilograms/hectare).The data show that the extra nitrogen didnot provide a large late-<strong>season</strong> color benefit.We may have applied the nitrogen, seen aquick greening response (although data werenot collected) <strong>and</strong> then had a frost before ourscheduled visual rating date, thereby losingthe data that showed the benefit. However,the most important point is that additionallate-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen enhanced Novembercolor retention without affecting <strong>cold</strong> hardiness,as determined by rhizome survival aftercontrolled freezing (Table 4) (11).The 2001-2002 winter was normal, <strong>and</strong>no field winterkill was noted. The 2002-2003winter was <strong>cold</strong>er than normal, <strong>and</strong> Tifwaywinterkill of approximately 30% was noted.However, winterkill percentage was the sameregardless of late-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen rate.Study 5: Miller <strong>and</strong> DickensThe second st<strong>and</strong>ard practice of the late<strong>season</strong><strong>bermudagrass</strong> management scenario isto apply potassium liberally with the intentionof promoting plants that are more <strong>cold</strong>hardy.Researchers at Auburn Universityconducted a study to answer this question:How much potassium is enough?Mature Tifway <strong>bermudagrass</strong>, managed at0.5 inch (12.7 millimeters) on a loamy s<strong>and</strong>(pH 6.0) at the Auburn University TurfgrassResearch Center in Auburn, Ala., was used inthis 1992-1994 study. The objective was toevaluate the effects of high annual potassiumapplication rates on <strong>cold</strong> resistance in<strong>bermudagrass</strong> (10). Initial soil-available potassiumwas very low at 36.0 pounds/acre (40.4kilograms/hectare).Potassium was applied from April throughOctober to cover a low to very high range ofmonthly rates: 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 <strong>and</strong> 4.0pounds potassium/1,000 square feet (0,12.2, 24.4, 48.8, 97.6 <strong>and</strong> 195.3 kilograms/hectare).Only the three highest potassiumrates were chosen for determination of<strong>cold</strong> resistance. The most significant resultsare outlined below.• At the end of the study (September1994), soil-test potassium levels wereapproximately 80 (low), 115 (low) <strong>and</strong>160 (moderate) pounds/acre (89.7, 128.9<strong>and</strong> 179.3 kilograms/hectare) for the 1.0,2.0 <strong>and</strong> 4.0 pounds potassium/1,000square feet/month (0, 48.8, 97.6 <strong>and</strong>195.3 kilograms/hectare/month) treatments,respectively.• The amount of potassium in <strong>bermudagrass</strong>leaf tissue increased until the 1.0 poundpotassium/1,000 square feet/month (97.6kilograms/hectare) level was reached. Atthis monthly potassium level <strong>and</strong> above,leaf-tissue potassium flat-lined at approx-COLOR AND FREEZING TOLERANCE, 2001-2002Nitrogen applicationTurf color (9 = darkest)August September October NovemberControl 8.2 8.0 7.0 3.6<strong>Late</strong>-<strong>season</strong> 8.2 7.9 7.2 4.3*% rhizome survival following freezing †39 F (3.9 C) 27 F (-2.8 C) 23 F (-5 C) 19 F (-7.2 C)Control 57.5 23.3 8.6 0.0<strong>Late</strong>-<strong>season</strong> 50.7 23.2 6.9 0.7*Significantly different from the control.†The percenages for rhizome survival following freezing are the averages of the data from Jan. 2 <strong>and</strong> Feb. 3, 2002.Table 4. Color ratings of Tifway <strong>bermudagrass</strong> <strong>and</strong> rhizome freezing <strong>tolerance</strong> as affected by late-summer <strong>and</strong> fall nitrogen applications averaged over 2001 <strong>and</strong> 2002.84 GCMSeptember 2004

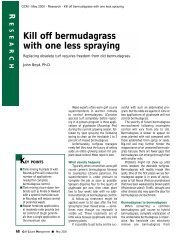

081-092 Sept04Techwell 8/17/04 5:21 PM Page 85RESEARCHimately 1.1%. This indicates that plantuptake of potassium was saturatedat monthly application rates of 1.0 poundor above.• Greenhouse, lab <strong>and</strong> field observationsindicated that applied potassium had noeffect on <strong>cold</strong> resistance.ConclusionsA 1971 trial (6) demonstrated that adequate,balanced ratios of nitrogen <strong>and</strong> potassiumwere more effective in promotingwinter survival of two <strong>bermudagrass</strong> cultivarsthan either high-nitrogen or high-potassiumfertilization programs. All of the studies summarizedin this paper, in which potassiumwas maintained at approximately moderatesoil-test sufficiency levels throughout theexperiments, support these earlier reports <strong>and</strong>suggest that continuing nitrogen fertilizationinto the later months of the growing <strong>season</strong>does not significantly affect freeze <strong>tolerance</strong>of <strong>bermudagrass</strong>, as long as other macronutrientssuch as potassium are not limiting.The last 15 years of research in the uppersoutheast <strong>and</strong> the transition zone of theUnited States indicate the possibility of aparadigm shift in our late-<strong>season</strong> nutrientmanagement of <strong>bermudagrass</strong>. Keeping<strong>bermudagrass</strong> green later in the fall has notresulted in a loss of <strong>cold</strong>-hardiness.We have two recommendations, withthree added precautions.If soil tests indicate potassium levels are inthe moderate to high range (121-400pounds/acre [135.6-448.3 kilograms/hectare), high rates of potassium do not needto be applied late in the <strong>season</strong> to improve<strong>bermudagrass</strong> <strong>cold</strong> hardiness.Applications of soluble nitrogen at 0.5 to1 pound nitrogen/1,000 square feet (24.4-48.8 kilograms/hectare) at two- to four-weekintervals, until hard frosts have resulted incomplete dormancy, will prolong fall colorretention <strong>and</strong> may enhance spring green-up(Figure 2).• Precaution 1. Apply lower rates of nitrogenon s<strong>and</strong>y soils where the risk of nitrateleaching is greater.• Precaution 2. Prove the benefits of late-<strong>season</strong>nitrogen to yourself <strong>and</strong> your constituentson a small scale beforeimplementing on the whole course.Experiment with rates <strong>and</strong> timings foryour location on one fairway or nurseryarea for at least one year.• Precaution 3. Be especially skeptical whenFigure 2. <strong>Late</strong>-October color resonses of Tifway <strong>bermudagrass</strong> three weeks after treatments were applied. From top tobottom, the treatments were: no nitrogen treatment, ammonium nitrate, IBDU (Isobutylidene Diurea, a slow-release nitrogensource) <strong>and</strong> methylene urea.considering the implementation of late<strong>season</strong>nitrogen on areas of the course historicallyprone to spring dead spot, as someresearch <strong>and</strong> experience has indicatedhigher late-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen causes greaterincidence of spring dead spot (9).Literature cited1. Adams, W.E., <strong>and</strong> M. Twersky. 1959. Effect of soilfertility on winter killing of Coastal <strong>bermudagrass</strong>.Agronomy Journal 52:325-326.2. Beard, J.B. 1973. Turfgrass: Science <strong>and</strong> culture.Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.3. Beard, J.B., <strong>and</strong> P.K. Rieke. 1966. The influence ofnitrogen, potassium <strong>and</strong> cutting height on the lowtemperature survival of grasses. AgronomyAbstracts 58:34.4. Carroll, J.C., <strong>and</strong> F.A. Welton. 1939. Effect of heavy<strong>and</strong> late applications of nitrogenous fertilizer on the<strong>cold</strong> resistance of Kentucky bluegrass. PlantPhysiology 14:297-308.5. Carrow, R.N., D.V. Waddington <strong>and</strong> P.E. Rieke. 2001.Turfgrass soil fertility <strong>and</strong> chemical problems. AnnArbor Press, Chelsea, Mich.6. Gilbert, W.B., <strong>and</strong> D.L. Davis. 1971. Influence of fertilityratios on winter hardiness of <strong>bermudagrass</strong>.Agronomy Journal 63:591-593.7. Goatley, J.M. Jr., V. Maddox, D.J. Lang <strong>and</strong> K.K.Crouse. 1994. ‘Tifgreen’ <strong>bermudagrass</strong> response tolate-<strong>season</strong> application of nitrogen <strong>and</strong> potassium.Agronomy Journal 86:7-10.8. McCarty, L.B. 2001. Best golf course managementpractices. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J.9. McCarty, L.B., L.T. Lucas <strong>and</strong> J.M. DiPaola. 1992.Spring dead spot occurrence in <strong>bermudagrass</strong> followingfungicide <strong>and</strong> nutrient applications.HortScience 27(10):1092-1093.10. Miller, G.L., <strong>and</strong> R. Dickens. 1996. Potassium fertilizationrelated to <strong>cold</strong> resistance in <strong>bermudagrass</strong>.Crop Science 36:1290-1295.11. Munshaw, G., <strong>and</strong> E.H. Ervin. 2004. Nutritional <strong>and</strong>PGR effects on lipid unsaturation, osmoregulantcontent, <strong>and</strong> relation to <strong>bermudagrass</strong> <strong>cold</strong> hardiness.Ph.D. dissertation, Virginia PolytechnicInstitute <strong>and</strong> State University: ETD-01162004-171301.12. Richardson, M.D. 2002.Turf quality <strong>and</strong> freezing <strong>tolerance</strong>of ‘Tifway’ <strong>bermudagrass</strong> as affected bylate-<strong>season</strong> nitrogen <strong>and</strong> trinexapac-ethyl. CropScience 42:1621-1626.13. Schmidt, R.E., <strong>and</strong> D.R. Chalmers. 1993. <strong>Late</strong> summerto early fall application of fertilizer <strong>and</strong> biostimulantson <strong>bermudagrass</strong>. International TurfgrassSociety Research Journal 7:715-721.14. Turgeon, A.J. 2002. Turfgrass management, 6th ed.Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J.E.H. Ervin, Ph.D. (ervin@vt.edu), is an assistant professor<strong>and</strong> J.M. Goatley Jr., Ph.D., is a turfgrass specialistin the department of crop <strong>and</strong> environmental scienceat Virginia Polytechnic Institute <strong>and</strong> State University,Blacksburg; M.D. Richardson, Ph.D., is an associateprofessor in the department of horticulture, Universityof Arkansas, Fayetteville; <strong>and</strong> G. Munshaw, Ph.D., is anassistant professor in the department of plant <strong>and</strong> soilsciences, Mississippi State University, Starksville.September 2004GCM 85