intro to photography - Reframing Photography

intro to photography - Reframing Photography

intro to photography - Reframing Photography

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

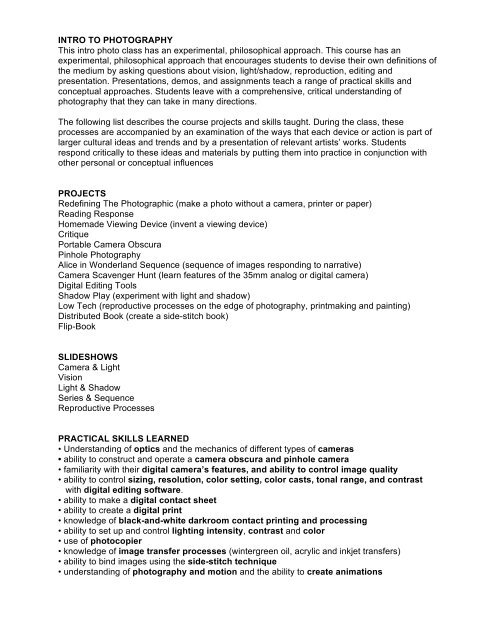

INTRO TO PHOTOGRAPHYThis <strong>intro</strong> pho<strong>to</strong> class has an experimental, philosophical approach. This course has anexperimental, philosophical approach that encourages students <strong>to</strong> devise their own definitions ofthe medium by asking questions about vision, light/shadow, reproduction, editing andpresentation. Presentations, demos, and assignments teach a range of practical skills andconceptual approaches. Students leave with a comprehensive, critical understanding ofpho<strong>to</strong>graphy that they can take in many directions.The following list describes the course projects and skills taught. During the class, theseprocesses are accompanied by an examination of the ways that each device or action is part oflarger cultural ideas and trends and by a presentation of relevant artists’ works. Studentsrespond critically <strong>to</strong> these ideas and materials by putting them in<strong>to</strong> practice in conjunction withother personal or conceptual influencesPROJECTSRedefining The Pho<strong>to</strong>graphic (make a pho<strong>to</strong> without a camera, printer or paper)Reading ResponseHomemade Viewing Device (invent a viewing device)CritiquePortable Camera ObscuraPinhole Pho<strong>to</strong>graphyAlice in Wonderland Sequence (sequence of images responding <strong>to</strong> narrative)Camera Scavenger Hunt (learn features of the 35mm analog or digital camera)Digital Editing ToolsShadow Play (experiment with light and shadow)Low Tech (reproductive processes on the edge of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, printmaking and painting)Distributed Book (create a side-stitch book)Flip-BookSLIDESHOWSCamera & LightVisionLight & ShadowSeries & SequenceReproductive ProcessesPRACTICAL SKILLS LEARNED• Understanding of optics and the mechanics of different types of cameras• ability <strong>to</strong> construct and operate a camera obscura and pinhole camera• familiarity with their digital camera’s features, and ability <strong>to</strong> control image quality• ability <strong>to</strong> control sizing, resolution, color setting, color casts, <strong>to</strong>nal range, and contrastwith digital editing software.• ability <strong>to</strong> make a digital contact sheet• ability <strong>to</strong> create a digital print• knowledge of black-and-white darkroom contact printing and processing• ability <strong>to</strong> set up and control lighting intensity, contrast and color• use of pho<strong>to</strong>copier• knowledge of image transfer processes (wintergreen oil, acrylic and inkjet transfers)• ability <strong>to</strong> bind images using the side-stitch technique• understanding of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy and motion and the ability <strong>to</strong> create animations

CONCEPTS LEARNED• greater understanding of the possibilities of “pho<strong>to</strong>graphy”• critical grasp of the nature of vision and how it is mediated by the eye/brain and byconstructed devices• familiarity with a range of artists’ works involving pho<strong>to</strong>graphy• appreciation of the dynamics between translating a text <strong>to</strong> image• ability <strong>to</strong> consider narrative that is presented as part of a series or within a sequence• awareness of the psychological and cultural significance of light and shadow• understanding of the democratic, monetary, and aesthetic connotations of pho<strong>to</strong>graphicreproduction• knowledge of several critique strategies and approachesPROJECT 1: REDEFINING THE PHOTOGRAPHICStudents make a “pho<strong>to</strong>graph” without using a camera, a digital printer or darkroom, or any kindof paper. This is an <strong>intro</strong>duc<strong>to</strong>ry project listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects as“Pho<strong>to</strong>graph Without Paper / Printer / Darkroom / Camera”.I often give this project on the first day of class because it asks students <strong>to</strong> reconsider how"pho<strong>to</strong>graphy" can be defined. Rather than reducing pho<strong>to</strong>graphy <strong>to</strong> its physical form (a printedimage), students begin <strong>to</strong> consider and identify conceptual characteristics of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy.I give very little <strong>intro</strong>duction <strong>to</strong> this project so that they really need <strong>to</strong> find their own way. A grea<strong>to</strong>utcome of the assignment is the conversation that takes place when students present theirwork from this project. It's interesting <strong>to</strong> learn significant experiences everyone has had withpho<strong>to</strong>graphy, and what the medium has enabled or affected in their lives. When I begin with thisproject, students seem <strong>to</strong> become more philosophical and better equipped <strong>to</strong> make conceptualleaps in their work in future projects, whatever the technical parameters of those projects maybe.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Pho<strong>to</strong>graphic Analogies, from the essay “Copying, Capturing,and Reproducing”, page 171.Author Susan Sontag agrees that pho<strong>to</strong>graphic images possess the presence of the original subject.In her essay “The Image-World,” she notes that past societies saw an object and its image as havingdifferent physical characteristics, but a similar “energy or spirit”.(2) While paintings may provide animage that is merely an appearance of the thing painted, “a pho<strong>to</strong>graph is not only an image (as apainting is an image), an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stenciled offthe real, like a footprint or a death mask.”(3) Like a fossil, a pho<strong>to</strong>graph offers a trace of an objectnow resigned <strong>to</strong> the past. As physical imprints, fossils and pho<strong>to</strong>graphs hold significant power; whilewe know they are not identical <strong>to</strong> their pre-fossilized selves, we understand that they are powerfulreplacements. As their referent disappears, the remnants become as important as the original. Indoing so, they essentially become similar <strong>to</strong> the source itself. Since my grandparents’ deaths, thefew pho<strong>to</strong>graphs I have of them have become increasingly valuable, <strong>to</strong> the point where, where I seethem, I almost feel as though I am visiting my grandma and pappy…..(2) Susan Sontag, On Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy (New York: Anchor Books, Doubleday, 1989), 155. originally published in 1977. (3) Susan Sontag, On Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, 154.

PROJECT 2: READING RESPONSEStudents post responses <strong>to</strong> weekly readings. This project is listed under the title “ReadingResponses” within the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects.The reading responses encourage students <strong>to</strong> process and analyze the ideas and information,and allow them <strong>to</strong> expand on these ideas. They are a helpful way for instruc<strong>to</strong>rs <strong>to</strong> keep track ofwhether and how students are interpreting the readings and how they are making connectionsbetween these <strong>to</strong>pics and their own artwork.PROJECT 3: HOMEMADE VIEWING DEVICEMake a viewing device that corrects/emphasizes your own habits as viewer. This project islisted under the same name within the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects.This project is helpful before we begin <strong>to</strong> work with cameras as it slows students down and asksthem <strong>to</strong> consider their own vision. The project gives students control over how their vision isaltered and how the world is seen. Hopefully, when we then start working with camera obscurasand digital and analog cameras, they’ll see these <strong>to</strong>ols more critically.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Visual Technologies, from the essay “Seeing, Perceiving andMediating Vision”, page 27Our inattention <strong>to</strong> the influences of <strong>to</strong>ols such as the eye and brain, visual conventions such asperspective, and our constructed environment is somewhat understandable. More surprising,perhaps, are the ways we use visual technologies daily, yet rarely notice how these devices organizeour world. We arrange friends within the camera’s viewfinder and consume TV narratives withoutactually regarding the technology that constructs the images. Just as we see without recognizingthe process of seeing, we bypass the technology that mediates visual encounters and go straight <strong>to</strong>the picture. When the <strong>to</strong>ols that produce the images are taken for granted, we become less awareof the pho<strong>to</strong>graphic way of seeing. In The Reconfigured Eye, William J. Mitchell explains that while wemay think we control the mechanics of pho<strong>to</strong>graphic construction—cameras, lenses, and otherparaphernalia—it is actually these devices that determine the way we “see the world”: “While wehave been using the <strong>to</strong>ols, operations, and media of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy <strong>to</strong> serve our pic<strong>to</strong>rial ends, theseinstruments and techniques have simultaneously been constructing us as perceiving subjects.” (88)…. (88) William J. Mitchell, The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-‐Pho<strong>to</strong>graphic Era (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1992), 59.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Learning <strong>to</strong> Assemble Vision, from the essay “Seeing,Perceiving and Mediating Vision”, page 13The neurologist Oliver Sacks writes that “most of us have no sense of the immensity of thisconstruction [our visual construction of the world], for we perform it seamlessly, unconsciously,thousands of times every day, at a glance.”(30) The complexity of this process becomes dauntinglyapparent within Sacks’s account of Virgil, a blind man in his fifties who, following cataract surgery,regained the use of his eyes. When the bandages were removed, Virgil experienced a world of sensafor the first time since childhood. However, Virgil still depended upon his prior faculties as a blindman (sound, <strong>to</strong>uch, taste, smell) <strong>to</strong> understand the sensa. For example, he recognized that a brightcolored blur comprised a man only upon hearing the man’s voice. He could experience thephenomena of light and color, but could not process them in<strong>to</strong> the appearances of objects. His need<strong>to</strong> relearn the world according <strong>to</strong> the codes of a sighted person illustrates that seeing is a learnedexperience, based on memory and accumulated encounters in a visual world. Like Virgil, apho<strong>to</strong>graphic camera cannot distinguish a person from a bicycle and does not know that one is aliveand the other inanimate. The eye of the camera is directed by an opera<strong>to</strong>r who selects, remembers,and perceives….. (30) Oliver Sacks, An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales (New York: Vintage Books, 1995) 127.

PROJECT 4: CRITIQUEStudents critique Homemade Viewing Devices and, later, Alice in Wonderland, Low Tech, andFlipBook.See:Tools, Materials, and Processes: EDITING, PRESENTATION, AND EVALUATION - Evaluation, page 469.PROJECT 5: PORTABLE CAMERA OBSCURASStudents make a portable camera obscura out of a cardboard box and with a utility knife,needle, drill/drill bit, heavy duty tape (black or duct), and a dark <strong>to</strong>wel/t-shirt.We take the cameras obscura outside <strong>to</strong> a nearby pond and spend some time just looking.Outside of class, I ask students <strong>to</strong> spend time documenting what they saw in the cameraobscura with any materials of their choice.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Visual Technologies, from the essay “Seeing, Perceiving andMediating Vision”, page 28The camera obscura is a key visual <strong>to</strong>ol that provides a model for understanding vision during the17th and 18th centuries. In the 5th century bc, the Chinese philosopher, Mo-Ti (470–390 bc),described the basic principal at work in the camera obscura: that light, traveling through a pinholein<strong>to</strong> a darkened room, would project an inverted image of the scene outside that chamber. Hereferred <strong>to</strong> this darkened room as a “collecting place” or the “locked treasure room.”89 Both termsemphasize what was assuredly a magical display of lights—in color, upside down, reversed from left<strong>to</strong> right, twinkling and ephemeral from motion—and downplay the images’ connection <strong>to</strong> the outsideworld. Mo-Ti’s “treasure room” appeared <strong>to</strong> offer a wondrous miracle. His description of thesephenomena would be redefined in future centuries as the camera obscura, a dark room widely usedby scientists, magicians, and artists….<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Constructing a Portable Camera Obscura, from the “Tools,Materials, Processes: VISION”, page 52Small or portable camera obscuras can be made out of any light-tight container: wooden boxes,books, tents, etc. The following directions explain how <strong>to</strong> elaborate upon the design of the room-sizecamera obscura by turning a cardboard box in<strong>to</strong> a portable camera obscura.For a basic portable camera obscura, find a box that can be closed on all sides and that, when fittedover your head, has at least 5 inches of room <strong>to</strong> spare from the <strong>to</strong>p of your head <strong>to</strong> the <strong>to</strong>p of thebox, and at least 12 inches between your eyes and the front of the box (the image plane).….PROJECT 6: PINHOLE PHOTOGRAPHY + ALICE IN WONDERLANDStudents build a pinhole camera and use it <strong>to</strong> visually translate a portion of a chapter of Alice inWonderland. The Alice assignment is listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects as “Alice inWonderland: Collaborative Sequencing”.Pinhole pho<strong>to</strong>graphy provides students another way of capturing the images they’ve just viewedin their cameras obscura. The dis<strong>to</strong>rted, dreamlike quality of the images suits the surreal qualityof Lewis Carroll’s s<strong>to</strong>ry, which provides an <strong>intro</strong>duction <strong>to</strong> narrative, sequence, and s<strong>to</strong>ry-telling.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Pinhole Cameras, from the “Tools, Materials, Processes:

VISION”, page 72.Pinhole cameras are lensless cameras, constructed and used as early as the 1850s. The camerabody has a small hole in one side, through which light passes and forms an image inside the camera.Because there is no lens <strong>to</strong> sharpen the image, pinhole images are fairly soft, which gives them aromantic quality. This is why they were popular in the 1890s with Pic<strong>to</strong>rialist pho<strong>to</strong>graphers whowanted pho<strong>to</strong>graphic images with the hazy look of paintings. Interest in pinhole pho<strong>to</strong>graphy fadedfor many decades, and then revived in the 1970s when the first his<strong>to</strong>ries of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy werepublished and artists began <strong>to</strong> look at older processes.See also:The pinhole as lens, page 58.The basic pinhole camera, page 78.Printing images: Traditional processes, page 261.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Series and Sequence, from the essay “Series and Sequence”,page 319.Grouping pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in series allows for organization and comparison—powerful <strong>to</strong>ols that allow us<strong>to</strong> grasp a diversity of information. Grouping individual pho<strong>to</strong>graphs in<strong>to</strong> series makes possible, forexample, the entire discipline of Art His<strong>to</strong>ry, which posits a linkage between objects as diverse as aCycladic figurine and Bernini’s statue of David, or the Great Ziggurat of Ur and Frank Gehry’sGuggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain.PROJECT 7: CAMERA SCAVENGER HUNTStudents become familiar with their camera’s manual and learn <strong>to</strong> control their camera’sfeatures. The assignment is listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects as “CameraScavenger Hunt”.There are several versions of this assignment, one that focuses on the technical features anduse of the viewfinder <strong>to</strong> frame, while the others complement the technical aspects withconceptual prompts.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Small-format Cameras, from the “Tools, Materials, Processes:VISION”, page 71.Small-format cameras are the most common size of camera, with the most variation in features andcost. The main differences between small format cameras are whether the viewing system is singlelens reflex (SLR), rangefinder/ viewfinder, or LCD screen, and whether the camera is analog or digital.Cameras with au<strong>to</strong>matic systems enable quick shots without the need <strong>to</strong> fuss with camera controls.Manual cameras, or cameras with a manual mode, allow you <strong>to</strong> selectively focus and/or chooseaperture and shutter speed.See also:The 35mm SLR camera body, page 82.The digital camera body, page 84.Camera controls, page 94.Film speed, page 232.Digital sensors, page 233.

PROJECT 8: DIGITAL EDITING TOOLSStudents become familiar with editing <strong>to</strong>ols in Camera Raw and Adobe Pho<strong>to</strong>shop. They canread about digital editing techniques and/or follow along with a class demo. The resource ofimages <strong>to</strong> correct is listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Presentations as “Bad Images.”Sometimes, I’ll ask them <strong>to</strong> use the <strong>to</strong>ols they’ve just learned <strong>to</strong> edit and reprint three or fourimages previously submitted in the class.See:Making a digital contact sheet, page 306.Digital printing, page 284.Digital resizing, page 382.Using Variations <strong>to</strong> learn <strong>to</strong> identify color casts, page 406.Using curves <strong>to</strong> correct color, page 407.Using Camera Raw <strong>to</strong> correct color casts, page 243.Using Levels and Curves <strong>to</strong> adjust <strong>to</strong>nal range and contrast, page 392.Making a gradual <strong>to</strong>nal adjustment, page 399.Digital burning & dodging, page 401.Creating shallow depth of field in a digital image, page 97.How <strong>to</strong> straighten images with the measuring <strong>to</strong>ol, page 92.How <strong>to</strong> record and play an action, page 466.PROJECT 9: SHADOW PLAYStudents experiment with light and shadow by creating a three-minute performance using onlylight, shadow, a backdrop and props. This project is listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphyProjects as “Shadow Play”.This project asks students <strong>to</strong> consider light and shadow as materials that form the subject ratherthan as secondary <strong>to</strong> the subject. Students learn <strong>to</strong> control contrast, intensity, and color.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Light is Radiation, from the essay “Light and Shadow”, page115.Our bodies note and respond <strong>to</strong> the effects of light and shadow—from the uplifting feeling ofsunlight on our faces (which triggers the body’s production of Vitamin D, an important nutrient), <strong>to</strong>the cooling effect of shadow on a warm summer day. (Interestingly, in a pho<strong>to</strong>graph, colortemperature has <strong>to</strong> do with the actual temperature of the physical process taking place, althoughthe results are the opposite of what we might expect: higher temperatures produce a more intenselight, with more of a blue cast, while a weaker, cooler light has a reddish cast.) Indeed, the naturalpatterns of light and dark drive the circadian rhythms (or “biological clock”) of humans and otheranimals. Winifred Gallagher writes that the “origins of the influences of light on our activity arerooted far back in the evolutionary past … [the] very survival of our species has depended onmatching the workings of our bodies and minds <strong>to</strong> the demands of the day and night.” (16) ….(16) Winifred Gallagher, The Power of Place: How Our Surroundings Shape Our Thoughts, Emotions and Actions (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007), 29. See also:Tools, Materials, and Processes: LIGHT AND SHADOW, page 137.

PROJECT 10: LOW TECHStudents learn low-tech reproductive processes and use them <strong>to</strong> create a book. This project islisted in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects as “Distributed Book” and “Side-Stitch Zine”.This process expands the notion of reproduction by using inexpensive processes such aswintergreen oil transfer, inkjet transfer, rubbings, and contact paper and gel medium transfer.The assignment emphasizes common methods between pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, printmaking, andpainting and allows students <strong>to</strong> play with pho<strong>to</strong>graphic images in painterly or mechanical ways.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, Pho<strong>to</strong>graphic Analogies, from the <strong>intro</strong>duction <strong>to</strong> “Copying,Capturing, and Reproducing”, page 169.Which is more valuable, the original or its copy? The essay “Copying, Capturing, and Reproducing”begins by considering some of the earliest negative impressions, fossils, and then continues <strong>to</strong> minethe his<strong>to</strong>rical and contemporary questions surrounding the value(s) of reproduction. This distancebetween the original and its after image is described by analogies from Genetics, in which thevariance from offspring <strong>to</strong> offspring resembles the variations from copy <strong>to</strong> copy, while still bearingclear resemblances <strong>to</strong> the source (the original). We also consider the position of pho<strong>to</strong>graphy as asingular object or a <strong>to</strong>ol of mass reproduction. Whereas the value of an au<strong>to</strong>nomous object lies in itsrarity, pho<strong>to</strong>graphy is a medium defined by reproduction, which posits much of its value in copies.The ubiquity of reproductions, from cartes de visite <strong>to</strong> digital files, has enabled political campaigns,the culture of celebrity, social revolutions, and Facebook.See also:Rubbings, page 219.Image transfer and rubbing techniques, page 223.Acrylic lifts, page 228.The book, page 445.PROJECT 11: FLIP-BOOKStudents create a flipbook. This project is listed in the <strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy Projects as “FlipBook”.For this project, students consider an alternative method of presentation that incorporatesstillness and animation. The project asks them <strong>to</strong> consider narrative, illusion, truth/fantasy, andmovement, and the challenge of working with a large number of images.<strong>Reframing</strong> Pho<strong>to</strong>graphy, The Flip Book, from the Presentation section of “Tools,Materials, Processes: Editing, Presentation, and Evaluation”, page 464.A flip book is a simple way <strong>to</strong> animate images. Also referred <strong>to</strong> as flick books or folioscopes, flipbooks can be approached as small films, with similar considerations of direction, scenery, andlighting. The sound of the fluttering pages mimics the sound of a film reel turning, and therectangular format is similar <strong>to</strong> a film screen. Unlike video or film animations, the flip book turns theviewer in<strong>to</strong> the anima<strong>to</strong>r. The viewer brings the still images <strong>to</strong> life, controls the speed (by shufflingthrough slowly or quickly), and the orientation (by viewing the action forwards and backwards).See also:Nineteenth-century viewing devices and their optical legacy, page 38.Motion, page 341.Batch processing, page 467.