Saskatchewan Mennonite Historian - September 2005

Saskatchewan Mennonite Historian - September 2005

Saskatchewan Mennonite Historian - September 2005

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

SASKATCHEWANMENNONITEHISTORIANOfficial periodical of the<strong>Mennonite</strong> Historical Society of <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>, Inc.Volume XI No. 3, <strong>September</strong>, <strong>2005</strong>Builder of Musical InstrumentsRandy Letkeman“Before I build, I look at the raw wood infront of me. I see in my mind a finished musicalinstrument.” So says Randy Letkeman, a 46year-old vocational training supervisor whoworks at the <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> Abilities Council inSaskatoon. Randy’s passion is making musicalinstruments and he has made lutes, guitars,mandolins, dulcimers and a hurdy gurdy.“Each instrument has a personality all itsown,” says Letkeman. “My job is to develop itas I put all the pieces together.”Indeed, Randy’s instruments are carefullycrafted. It all begins with the selection of qualitymaterials: sitka spruce from British Columbia;ebony from Africa; boxwood from Europe;maple from Ontario; coniferous sap to makevarnish, and; hardened bone from the leg boneof a beef steer to make keys. These are butsome items needed.Randy believes he inherited some of hiscreativity and abilities from his grandparents.His grandfather George Letkeman was a musicianand choir director in the Great Deer <strong>Mennonite</strong>Brethren Church. His other grandfather,David Martens, who founded Martensville inthe early 1950s, was a man of many talents –carpenter, welder, and designer.Today, Randy lives in Martensville, atown 15 kilometers north of Saskatoon, in anadequate bungalow with his wife, Christel(Leola and Edgar Epp’s daughter) and children,Samantha and Loyal. In Randy’s backyardis his beloved workshop. It is there thatthat he spends his time designing and building.Randy’s first building project, at age 12,was a model airplane. By age 25, he had built acrude dulcimer. A guitar and banjo player, hegot interested in how they were put together.Soon he joined the Luthiers Guild and began tocraft other instruments. It was the hurdy gurdythat challenged him most. “It has a stubbornpersonality,” he observes, “that makes it hardto play. It is a complicated instrument withvarious characteristics that must all work together.The guitar responds more easily andhas a mild temperament,” he notes.Randy believes that as he gives life towood in the form of instruments, they respondby giving him immeasurable pleasure.What is next for Randy? “I dream ofbuilding a harpsichord”, he notes. “That wouldbe the ultimate challenge.”

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 2SASKATCHEWANMENNONITE HISTORIAN2326 Cairns AvenueSaskatoon, SK. S7J 1V1Editor: Dick H. EppBook Editor: Victor G. WiebeGenealogy Page Editor:Rosemary SlaterProduction/Design: BettyBanman, Diana Buhler, HelenFast, Deanna Krahn, RosemarySlater, Hilda VothProof Readers: Ernie Baergen,Betty Epp, Verner Friesen,Advisory Committee:Jake Buhler, Verner Friesen,Esther PatkauThe Editor invites readers to participate bysending news, articles, photos, church historiesand other items to him by email atdhepp1@shaw.caHONOUR LISTHelen BahnmannHelen DyckDick H. EppMargaret EppPeter K. Epp †George K. Fehr †Jake FehrJacob E. FriesenJacob G. GuenterGerhard Hiebert †Katherine Hooge †Abram G. JanzenJohn J. Janzen †George Krahn †Ingrid Janzen-LampJ.J.Neudorf †J.C.Neufeld †John P. NickelEsther PatkauDr. Ted RegehrEd RothWilmer Roth †Arnold Schroeder †Katherine Thiessen †Rev. J.J. Thiessen †Dr. David Toews †Toby Unruh †George Zacharias †PresidentJake Buhler836 Main StreetSaskatoon, SK S7H 0K3Tel.: 244-1392jakelouisebuhler@sasktel.netVice-PresidentVerner Friesen1517 Adelaide St. ESaskatoon, SK S7J 0J2Tel: 373-8275vafriesen@sasktel.netSecretary/Archivist,MCSaskVera FalkBox 251Dundurn, SK S0K 1K0Tel: 492-4731Fax: 492-4731r.v.of.thodeandshields@sasktel.netTreasurerMargaret SniderBox 35Guernsey, SK S0K 1W0Tel: (306) 365-4274sniderwm@sasktel.netArchivesKathy BoldtBox 152, RR #4Saskatoon, SK S7K 3J7Tel: 239-4742keboldt@sasktel.netAbe BuhlerBox 1074Warman, SK S0K 4S0Tel: 931-2512Margaret EwertBox 127Drake, SK S0K 0H0Tel: 363-2077mewert@canada.comEileen QuiringBox 2Waldheim, SK S0K 4R0Tel: (306) 945-2165eileenajq@sasktel.netEd SchmidtBox 28Waldheim, SK S0K 4R0Tel: (306) 945-2217ewschmidt@sasktel.netTo add a name to the Honour List, nominate a person in writing. Candidates musthave made significant contributions to the preservation of <strong>Mennonite</strong> history,heritage or faith in our province.MHSS Board of Directors, <strong>2005</strong>Victor G. WiebeBook Review Editor/Archivist11 Kindrachuk Cres.Saskatoon, SK S7K 6J1Tel: 934-8125victor.wiebe@usask.caBoard CommitteesPhotographer SMHSusan BraunBox 281Osler, SK S0K 3A0Tel: 239-4201Cemeteries/ArchivesHelen Fast146 Columbia DriveSaskatoon, SK S7K 1E9Tel: 242-5448Fax: 668-6844rhfastlane@shaw.caCemetery Project MHSSJohn P. NickelGeneral DeliveryBattleford, SK S0M 0C0Tel: 937-2134johnpnickel@sasktel.netAdvisory Committee SMHEsther Patkau2206 Wigging AvenueSaskatoon, SK S7J 1W7Tel: 343-8645Genealogy Page Editor, SMHRosemary Slater111 O’Neil CrescentSaskatoon, SK S7N 1W9Tel: 955-3759r.slater@sasktel.net<strong>Mennonite</strong> Historical Societyof <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> (MHSS)Room 900-110 La Ronge RoadSaskatoon, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>S7K 7H8(306) 242-6105mhss@sasktel.netArchive HoursMonday: 1:30-4:00 p.m.Wednesday: 1:30-4:00 p.m.Wednesday: 7:00-9:00 p.m.Is your membership paid up?

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 3President’s MessagePresident’s Columnour communities, are also likerailway ties. If we choose totell our stories, we leave ourdate mark – a record of whowe are, what we did, and whywe did it.Old Testament records urgedthe Hebrew people to markthe great deeds of Jehovah, byerecting stone cairns. “Whenyour children ask what thesestones mean, you shall tellthem how Israel crossed overthe Jordan.” (Joshua 4: 21paraphrased)MHSS President GetsMaster of TheologyDegreeWe extend congratulations to ourHistorical Society BoardPresident, Jake Buhler, whograduated from St. Andrew’sCollege in Saskatoon on May 5,<strong>2005</strong>, with a Master of Theologydegree. St. Andrew’s at theUniversity of <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> is aUnited Church of Canadaseminary that trains persons forthe ministry. Jake majored inpastoral care.I have in front of me a smalldate marker. It looks like a nailwith a big head on it. In earlieryears, these date markers wereused to date railway ties. Asthey were put into the rail-bedby hand, a crew member wouldnail these small metal spikesinto the wooden rail ties. Sectionbosses could then monitortheir health and condition. BetweenOsler and Hague, theoldest railway tie still in usehas a 1940 date marker.The date marker I have containsthe number 37. The railwaytie it came from was removedfrom the Osler areaabout five years ago. Since1937, in sun and snow, indrought and rain, this markerhas served as a record of thelife of one railway tie.We, like the railway tie, haveour own life. Our families, ourinstitutions, our churches, andThe <strong>Mennonite</strong> Historical Societyof <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> is acollector of date markers andrecorder of stone cairns. Ourtask is to gather the stories ofour people and to make themavailable for all to see. Andthat is why we conduct GenealogyDays…why we haveArtisans Exhibitions…whywe collect the letters andbooks of our people…why wedocument cemeteries, why weinvite historians to interpretour journeys…and why wehave volunteers who servethose looking for information.I encourage you to put yourdate marker on your life.Write the story of your life, orof your community or church.Not only will you be acting ina biblical tradition; you willgive your children and theirchildren a living heritage.Jake BuhlerBefore enrolling at St. Andrew’s,Jake and his wife Louise hadspent twenty-one years overseas,first working for MCC inThailand for six years, then forthe Canadian Embassies inThailand and Vietnam for fifteenyears. Currently Jake works as alay minister at Osler <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church but has no immediateplans for more than that at thepresent time.************Passing the Comfort Quilters from CalgaryL to R, Katie Penner, Elsie Sawatzky,Paulene Sawatzky and Lil Bartel.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 4Editorial<strong>Saskatchewan</strong> Turns 100By Verner FriesenIt was on <strong>September</strong> 4, 1905 that <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>officially became a province in thedominion that stretches from sea to sea. The firstLieutenant Governor of the province was A. E.Forget, who appointed Walter Scott to be the firstprovincial premier. Walter Scott took office on<strong>September</strong> 12, and selected three other persons tobe sworn in along with him as the first governingbody in the province. The three were: J. H. Lamont,Attorney General; W. R. Motherwell, Ministerof Agriculture; and J. A. Calder, Minister ofEducation.On December 13 of the same year the peopleof <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> went to the polls for the firsttime in 25 constituencies. The electorate endorsedthe Liberal government of Walter Scott with 17seats in the legislature. The opposition party atthat time was the Provincial Rights party under F.W. G. Haultain, former premier of the NorthWest Terrritories.The member elected to the first legislaturein the Rosthern constituency was Gerhard Ens.Ens had come with his family to Canada fromRussia in 1891, and his family was one of six<strong>Mennonite</strong> families who settled in the Rosthernarea in 1892. Ens soon began vigorously promotingimmigration to Canada and settlement on thewestern frontier.Canadian government census figures indicatethat in 1901 there were 3,787 <strong>Mennonite</strong>s in<strong>Saskatchewan</strong>. The following decade shows asubstantial increase in that number; by 1911 therewere 14,586.For those early <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> pioneers, lifewas often very difficult - hard work, financialwoes, severe privations, etc. We, their descendants,have reaped many of the rewards of theirsacrifices. As someone (author unknown) haswritten:"We drink from wells we did not find;We eat food from farmland we did not develop;We enjoy freedoms which we have not earned;We worship in churches which we did not build;We live in communities which we did not establish."<strong>Saskatchewan</strong> has been good to us. "Theboundary lines have fallen for (us) in pleasantplaces; (we) have a goodly heritage". (Psalm 16:6)****************CARROT RIVER CONGREGATIONHONOURS 75 YEARSFrom the <strong>September</strong> 6, 2004 issue of the Canadian<strong>Mennonite</strong>Used by permission“The Lord is good and his love endures forever.His faithfulness continues through all generations”(Psalm 100:5) was the theme for the 75 th anniversaryof Carrot River <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church, August7-8.Approximately 200 people registered for theweekend celebration. Current members were joinedby former pastors, teachers, family members andfriends from British Columbia, Alberta, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>,Manitoba, Ontario and Indiana.Acquaintances were renewed and new onesmade as stories were shared. Several former teacherswho taught in the rural schools of the area duringthe 1950s made connections with former students.One person remembered being hosted by achurch family when he was in a conscientious objectors’camp during World War II.Histories, photographs and regional maps onthe wall created considerable interest. Some foundthe homesteads their parents or grandparents cameto in 1926 and in the years following. Others foundthe location of rural schools that have long sincedisappeared.In 1925 the first three <strong>Mennonite</strong> familiescame into the area south of what is now the town ofCarrot River. Abandoned shacks became their temporaryhomes. More people arrived - by 1931, over100 families. Participants celebrated the beginningof the Hoffnungsfelder <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church south ofCarrot River in 1929 and the establishment of thePetaigan <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church, north of Carrot River,in 1937. The two congregations joined in 1960when a new church was built in Carrot River itself.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 5Three original charter members of theHoffnungsfelder congregation -Tena Andres,Catherine Schapansky and Mary Gerbrandt -attended the celebration. Three former pastors,Peter Peters from Manitoba, Abe Buhler fromBritish Columbia, and John Wiebe from Manitoba,participated in the Saturday evening programor Sunday worship. Current pastor CraigHollands shared moments from the life of thechurch and led the choir on Sunday morning.Although inclement weather curtailedoutdoor activities, the atmosphere inside waswarm and hospitable. As the celebration endedwe were reminded that the Lord has been, andis, good. We claimed God’s enduring love forthe future of this church, in this community.Membership and attendance has fluctuatedover the years. Presently the church is onan upward trend, blessed with a large group ofyoung children.From reports by Audrey Bechtel andTrudy FastCarrot River Church 1928The atmosphere was one of joy and gratitude.Deep into the depression of the 1930s, Jacob Pankratzof Truax, Sask. was compelled to move out of thatarea to find employment. He found it at Watrous.There he also found his life partner in Margaret Kornelsen.They married June 16, 1935 in the newly organizedBethany <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church at Watrous.Jacob had come with his family from Alexanderwohl,Molotschna, via Datum and Mexico to settle inTruax in 1926. Margaret arrived in Canada with her familyfrom Kusmitzky, Russia, via Moscow and Germany, tomake her home in Watrous.The Lord sent showers of blessings in an all-daydownpour of rain upon this couple who would begin theirmarried life in the drought-stricken southern town ofTruax. Four of their five children - John, Justina, Nettieand Jake - were born in Truax. Isaac was born after thefamily's move to Watrous in 1943.Both Jacob and Margaret have been entwined intheir love of farm life, Jacob with a deep attachment tocattle and Margaret with a flair for gardening. Evennow, at 93, she maintains the reputation of being the firstto have lettuce in spring.Jacob and Margaret have been active and supportiveparticipants in the life and work of Bethany <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church. Margaret was the first to be baptizedthere. Margaret and Jacob's wedding was the first to beperformed there. Their 70 th wedding anniversary, too, is afirst - the first couple in the congregation to have reachedsuch a milestone."Even to your old age and gray hairs I am He, I amHe who will sustain you. I have made you and I willcarry you; I will sustain you and I will rescue you." Isaiah46:4.Submitted by Helen Kornelsen70th Wedding Anniversary ofJacob and Margaret (nee Kornelsen) PankratzThe 70 th wedding anniversary of Jacob andMargaret Pankratz, Watrous, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>, wasquietly celebrated by family members in their homeJune 15,<strong>2005</strong>, on the eve of their actual anniversary.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 6Nutana Park <strong>Mennonite</strong> ChurchTurns 40Nutana Park <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church beganfrom a church planting initiative of First <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church in Saskatoon. Edward Enns,pastor of First <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church at that time,described the starting of the new congregationin these words: "We will separate in a nontraditionalway - not because of internal strifeor cliquishness, not on the basis of age or differenceof purpose, but because of unity ofpurpose. We will go to one or the other of thetwo congregations for various secondary reasons,but our need for two groups will give usnew opportunities to live out the definition ofthe church - the ‘called out’ ones, whose witnesswill broaden and call out more into thefellowship of the church".The first worship service in the newNutana Park congregation took place on April4, 1965. 103 charter members became the nucleusof the congregation, 76 tranferring infrom First <strong>Mennonite</strong>, the rest from other areacongregations. Most of them lived in the NutanaPark subdivision where the new churchwas built.On the weekend of May 13 to 15, <strong>2005</strong>,present and former members of the congregationgathered to celebrate the 40th anniversaryof Nutana Park. Friday evening was reservedfor registration and greeting former memberswho had come back for the special occasion.Ernie Baergen, the first chairperson of the congregation,had prepared a detailed account ofthe 40-year history. Dick and Betty Epp, withthe help of many volunteers, had then produceda comprehensive time line portrayingthat history in words and pictures. This timeline created a good deal of interest.Saturday afternoon brought young andold together in a variety of intergenerationalactivities - like assembling a giant puzzle in theshape of a church, and a jeopardy-style gamein which various persons in the congregationwere to be identified on the basis of clues provided.One question that stumped everyonewas "Ha, Ha, Ha, Ha." The answer - the four membersof the Ha family, the first refugee family sponsoredby the congregation in 1979.A highlight of the weekend was a beautifuland inspirational concert presented by the currentSenior Choir joined by former choir members. Thechoir was led by Duff Warkentin, the present conductor,with two former conductors, Jake Ens andAlf Dahl, contributing as guest conductors.The weekend concluded with an intergenerationalSunday morning worship service. Both thechildren's and adult choirs participated. In PastorVern Ratzlaff s sermon he shared his vision of whatthe congregation is meant to be - a church "seekingto heal rifts; signing covenants with fellow congregations;recognizing the larger church and our sistersand brothers there - <strong>Mennonite</strong> World Conference,inter-church friendships and worship that rundeep and wide, marriages that recognize love doesnot limit itself to denominational lines, bible studiesand prayer groups that bring Catholics and UnitedChurch and Presbyterians and <strong>Mennonite</strong>s together;- - - All generations, represented here in the communionof saints, where women and men, youngand old, people of all classes, prophesy, speak God'sword. That's God's way of doing things in the historyof the church. That's God's work in us; that'sGod's intent and promise for us. All generations".In between the various weekend sessions, ofcourse, there were also coffee breaks and deliciousmeals, with lots of reminiscing and visiting andwarm fellowship.

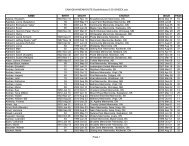

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 7Nota bena:mark well and observeOur Reader’s Page: Announcements and QuestionsMENNONITEHISTORICALSOCIETYOFSASKATCHEWANINC.GENEALOGYDAYOF $15.00REGISTRATIONOF(OR $25 PER COUPLE)OR $25INCLUDES THE NOONMEALAT THEFELLOWSHIPHALL- BETHANYMANOR110 LARONGELRD., SASKATOONSASKATOON, , SKOVEMBER 12, <strong>2005</strong>—9:30AM—12:00NOONNOVEMBERNOON(DOORSOPEN AT 8:30 AM FOR DISPLAYS, , BOOKBSALES, , ETCETC.)PRESENTATIONOF GENVUHARVEYMARTENS(COFFEE,, WATERWATER, , COOKIESCAVAILABLE )SHARINGHISTORYPROJECTSFROMVARIOUS GENEALOGYPLATFORMSCONTACTED SCHMIDTATEWSCHMIDT@SASKTELSASKTEL.NETOR (306-945945-2217)IF YOU HAVE A GENEALOGYPROJECTTHAT YOUHAVE DONE OR ARE DOING ON COMPUTER ANDARE WILLING TO SHARE WITH THE ATTENDEESAND HARVEYMARTENS.NOVEMBER12, <strong>2005</strong> – 12:45 P.M. – 3:45 P.M.PRESENTATIONSBY THE VICTORWIEBESAND VINCENTREMPELSAbout their May/June Tour of NorthernEurope—Short Break to Reorganize—Applied Demonstrations Of ApplicationOf GenVu<strong>Mennonite</strong> HostsAndRefugee Newcomers:1979—The PresentA Weekend History Conference30 <strong>September</strong>—1 October <strong>2005</strong>Eckhart Gramatté Hall,University of WinnipegSponsored by:the <strong>Mennonite</strong> Historical Societyof Canada.For more info contact Royden Loewen atr.loewen@uwinnipeg.caor 204-786-9391.****************MB Archives new address:As of April 25, <strong>2005</strong>:1310 Taylor Avenue,Winnipeg, ManitobaR3M 3Z6***************Membership Fees and Gift SubscriptionsWhen your membership expiration date on your addresslabel is underlined you know that it has expired. Sendyour membership fee to Treasurer, Room 900-110 LaRonge Road, Saskatoon, SK S7K 7H8 so that you will notmiss the next issue. Single memberships are $25.00, families$40.00. Gift subscriptions are available for friends,children, and grandchildren. We include a gift card withthe first subscription. All subscriptions and donations tothe society are eligible for tax deduction receipts.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 8Hoffnungsfelder <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church of Carrot RiverBeginning of the South ChurchIn the fall of 1925 the Peter P. Miller familyfrom Aberdeen, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>, and two other<strong>Mennonite</strong> families settled in the Carrot Riverarea (Township 49 - Range. 11). In the followingyears more families moved here.The <strong>Mennonite</strong> settlement did not increase toorapidly at first, but over the years this changeddramatically. By June 1928 fifteen <strong>Mennonite</strong>families had settled here. In the next year thisnumber had doubled. Five years after the first<strong>Mennonite</strong>s arrived here the count had risen tofifty families, and steadily kept increasing asthe years went by. In the fall of 1931 the counthad risen to one hundred and ten families.An itinerant pastor by the name of BenjaminEwert from the Conference of <strong>Mennonite</strong>s inCentral Canada visited the settlement from thevery beginning. He served with sermons, baptismsand communion services, as well as usinghis leadership abilities to guide and directthis new congregation until they were independent.In the fall of 1928 a small church was built. Dimensionswere 26 x 30 feet. This church, with Rev.Benjamin Ewert officiating, was dedicated March31, 1929.November 29, 1929 a brotherhood meeting tookplace, under the leadership of Rev. BenjaminEwert, with the purpose to organize the congregation.Here are the minutes of that meeting:"It was decided that we, newly settled <strong>Mennonite</strong>sat Carrot River, Sask. unite as a congregation, andthat our foundation be the Word of God, the plumbline of our confession of faith and our lives. Therefore;Jesus Christ to be our cornerstone.”The name of the church to be: Hoffnungsfelder<strong>Mennonite</strong> Church of Carrot River, Sask.It was decided that in spiritual matters to ask theConference of <strong>Mennonite</strong>s in Central Canada fortheir help until we have our own pastors. We alsowant to be affiliated with this Conference in the future.It was decided that the congregation elect threemembers as a church council. Their responsibilitywould be to give direction when needed. Of thesethree, one will act as secretary treasurer. Also twobrethren were elected to lead the Sunday School, aswell as worship services.His first visit was in June of 1926. His secondvisit was in November 1927, and after that formany years he came twice a year - in springand in fall. In spring he usually stayed threeweeks, and in fall two weeks or longer.On May 20, 1928 the first baptism service tookplace. Seven people were baptized after receivingspiritual instruction, and on the sameday the first communion service took place.(This was in a home.)In the following years several other <strong>Mennonite</strong>pastors came to serve with Sunday morningsermons. One of these was Rev. David H.Neufeldt from the Bethany <strong>Mennonite</strong> Churchin Lost River. He came frequently to visit,preach and serve.At the Brotherhood meeting June 25, 1931, a discussiontook place whether the congregation wasprepared to have an election for a pastor. The resultswere: 12 votes in favour, 11 against and 1 undecided.Therefore the conclusion was reached topostpone the election of a pastor until the fall of thesame year.At the brotherhood meeting November 21, 1931,once again the question arose whether to elect apastor. Through a secret ballot, the result indicated13 in favour, 2 opposed and 1 undecided. Hence itwas decided that the election should take place.Four candidates were to be elected and from thesetwo pastors were to be chosen.Sunday, November 22, 1931 the four candidateswere chosen by secret ballot. The result was: David

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 9Dyck - 12 votes; John D. Litke - 11 votes; JohannesC. Matthies - 7 votes; Richard Friesen -5 votes; Peter M. Epp - 3 votes; and the followingeach had one vote: Jacob Letkeman,Gerhard Matthies, Robert Friesen, Abram B.D.Friesen, and Isaac Neufeldt. The four with themost votes were declared candidates for thepastoral position. Thirty-four (34) brethrentook part in the voting.A second ballot produced the following results:David Dyck - 23 votes; Richard Friesen - 21votes; J.C. Matthies - 11 votes; John D. Litke -8 votes. Therefore David Dyck and RichardFriesen were declared elected as pastors.All of these elections took place under theleadership of Rev. Benjamin Ewert from Winnipeg,the itinerant pastor. David Dyck waselected church secretary.planned and cared for cemetery.Decided that Isbr Toews and K. Quiring shouldbring the wood needed to build the fence for tyingup the horses. A. Dyck took responsibility to buildthe fence.There was also to be a barn for the horses whichwould be 26ft long 7ft high 7ft wide. Stalls to be 7ftwide.Each family was expected to deliver two loads offire wood to the church for heating the churchwhich seemed to be very hard for every one to deliverthe two loads.There was a 25 cent levy for each member to bepaid to the church; later it was raised to 50 centswhich proved to be very hard to collect.On July 24, 1933 Elder Gerhard Buhler fromHerbert came to Carrot River and the followingweek held evening services every day. OnJuly 30 the ordination of three brethren as pastorstook place: David J. Dyck, RichardFriesen and John Litke. The choir of the HoffnungsfelderChurch sang two songs. Attendanceat the morning service was very good,filling the church to capacity. In the afternoonDavid Dyck, Richard Friesen and John Litkeeach presented a short message and Rev.Gerhard Buhler served communion. DavidDyck was elected as the leading minister of thecongregation. The afternoon service was notattended quite as well. After the services Rev.and Mrs. Buhler returned to their home in Herbert.This was the beginning of the <strong>Mennonite</strong>church at Carrot River.Several events took place that are important tothe life of the church. In 1930 a cemetery wasestablished south of town (SE28-twp49-rge 11)which was our cemetery for many years; theland was owned by Wilhelm Toews. In lateryears the town of Carrot River and R M ofMoose Range took over the cemetery. It thenbecame a community cemetery; which is verygood to see it taken over by the larger community.It is a very attractive place; very wellIn the later 30s the Petaigan church was established;then those that had settled north of town attendedthere.1937 the levy was raised to 75cents; then in l938the levy was raised to $1.00.1938 it was decided to put a basement under thechurch; then in 1939 the project got under way withgravel hauled by volunteers. P. Heppner was hiredto take leadership in construction for the basement;the other labour was volunteer. The basement wasto be 4 ft deep as well as above ground.1944 the levy was raised to $2.00. 1952 the levywas raised to $5.00. Also in 1952 it was resolvedthat every third Sunday message be in English.Also pastors were to be paid travel expenses whentaking a ministers course or attending a conference.Easter 1960 was dedication for the new church inCarrot River; this was the beginning of the CarrotRiver <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church; with the south and northchurches together.Herman Enns.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 10Hoffnungsfeld <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church, Petaigan, Sask.It was in the year 1925 when the first <strong>Mennonite</strong>families arrived and took up their homesteadsin townships 49, Range 11. Other familiesfollowed coming from Rosthern, Laird,Waldheim, Aberdeen and other places and alsosettled there and further north in Townships 50and 51, in the Petaigan district. The large CorneliusBoschman Sr. family from Aberdeentook homesteads along with 5 of their sons.Comelius C. Boschman Jr. was married andwas an ordained minister. He very soonstarted to get people together for SundaySchool and Church service. In the beginningthey came together in the homes. Ministersfrom southern and central <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> alsocame to help with the special services andmarriages.In 1934 the group decided to start to build achurch, It was built with squared timbers andwas all volunteer work. Progress was veryslow, but in 1937 the building was dedicated tothe Lord. Elder Benjamin Ewert officiated.About the same time they organized as achurch, calling it Hoffnungsfeld <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church at Petaigan, Sask. with a membershipof 58.farmers, and at times felt somewhat inadequate fortheir ministry tasks, the church invited other ministersand evangelists for special services. These serviceswere provided by ministers such asRev.G.G.Epp from Eigenheim; Rev. JohannesRegier from Tiefengrund; Rev. C.F. Sawatzky fromLaird; Rev. David Toews from Rosthern. Thechurch also had the joy and blessing of visits frommissionaries from foreign fields, travelling ministers,evangelists and young people’s workers. Also,several of the teachers who taught in this area werea welcome addition to the teaching and music life ofthe church.The inspirational meetings and teachings reaped aharvest of dedicated church and mission workers;Paul W. Boschman, son of Rev. C.C. and AgathaBoschman became a missionary. After obtaininghis BA. at Bethel College he was ordained as a ministerof the gospel, at his home church in Petaigan,in July 1948. He worked as Missionary Candidatefor some time by preaching in different churches.Then on Sept.2, 1951, Paul and his wife LaVernewere ordained as missionaries by Rev. J.J. Thiessenof the General Conference Mission Board, andcommissioned by the church to go to Japan. Theyspent about 20 years as missionaries there.InRev. Benjamin Ewert served this church aswell as the Carrot River (South) church rightfrom the beginning as Elder and with occasionalSunday sermons and for other functions.Rev C.C. Boschman was the congregation’sfirst minister, and under his leadership thechurch grew in number and in spiritual life.However, as Rev. Boschman was a farmer aswell as a minister, in 1942 the church decidedthat the work was getting too much for onepastor so they held an election. Brother BernardJ. Andres was elected and on August 25,1943 was ordained as pastor. Rev. G.G. Eppofficiated.Since both of the church ministers were alsoPaul & Agatha Boschman and family.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 11the spring of 1951 Henry Schroeder was ordainedas Missions Minister after having finishedBible School at Carlea, Sask. His worktook him to various places in Ontario.with German. Youth meetings were held regularlyand included events together with the South churchand Lost River as well as with the <strong>Saskatchewan</strong><strong>Mennonite</strong> Youth Organization.On July 31, 1955 Martha Boschman, daughterof Rev. and Mrs C.C. Boschman was ordainedas missionary nurse to Taiwan. She receivedher nurses training in the Victoria Hospital inPrince Albert, Sask. and her Bible training atthe Bible College in Winnipeg. Rev. J. J. Thiessen,and Rev. Andrew Shelly of the GeneralConference Mission Board officiated at herordination. While in the field, she met andmarried Han Vandenberg and together theyserved 30 plus years as missionaries in Japan.<strong>September</strong> 5, 1958 the church had the privilegeof ordaining another church member, Abe L.Froese, as a Mission Minister. He is a son-inlawto Rev and Mrs. C.C. Boschman. Abe andhis wife Lynda spent several years doing Missionwork in Northern Manitoba and then pastoringchurches in other areas of Manitoba.The Ministers’ Conference of the <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>and Canadian Conferences suggested thatchurches in the area elect their own Elder.Two churches, Lost River and Petaigan, agreedto elect one Elder between them and invitedRev. J. J. Nickel to lead the election. The candidateswere: Jacob J.Enns, Lost River; CorneliusEnns, Nipawin; Bernhard J. Andres, Petaiganand Cornelius C. Boschman of Petaigan.As a result of that election, Rev. C.C. Boschmanwas ordained as Elder for the Lost Riverand Petaigan Churches on <strong>September</strong> 6, 1953.The Rev. G.G. Epp officiated.Much of the worship service was conducted inGerman, but at some point in the 1950’s thecongregation recognized that some Englishwas needed in order to hold the interest andloyalty of the young people. Therefore a decisionwas made to have about 1 sermon a monthin English. Rev. B. J. Andres was selected todo the English preaching. “Young People’s”meetings were also in English as that generationwas more comfortable with English thanIn the 1950’s church membership began to declinebecause the young people were leaving the communityto work elsewhere, and some of the olderpeople were selling their homesteads and movingaway. The membership slowly went down from ahigh of about 90 to 30, when the church amalgamatedwith the South church forming a new churchin Carrot River.The Carrot River Church (South of Town) wasneeding to build a new church, so the church atPetaigan and the South Church agreed to build onetogether in the town of Carrot River. Buildingstarted in early summer in 1959 and on EasterMonday in April 1960 the new church in CarrotRiver was dedicated to the Lord. The Rev. J.C.Schmidt of Rosthern officiated in the dedication.It had been agreed between the two churches thatthe new church should have a new name and thatthe membership would be comprised of the membersof the two founding churches. A new churchregister was purchased, and all the names of themembers of the founding churches were enteredinto the register of the "Carrot River <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church ".Written by Trudy Fast & Len Andres –from various sources including a report by Rev.C.C. BoschmanPetaigan Church

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 12"I havebeenthrough somanychanges inmy life. Idid notthink Iwouldhave tolivethroughanotherone."Helen Kliewer BergmanThese were the words spoken by my greatgrandmother when she was moved from the independenceof her small house on Louise Ave. inSaskatoon to an assisted living unit in BethanyVilla. As it turned out, this was not yet her lastmove. Before her death on March 14, <strong>2005</strong> atthe age of 99, of necessity Great Grandma hadbeen relocated a final time to a nursing home inDalmeny. Impending death held no dismay forher. She was prepared and welcomed movingon. Through the years, Great Grandma wasknown for her love of things green - her carefullytended fruit trees, her vegetable garden,and the deep pleasure she derived from theblooms she nurtured. At the age of 85, being afirm believer that soil turned in fall retained themoisture for the coming year, Great Grandmastill spaded her entire garden by hand. As wellshe presided over the kitchen with accomplishedskill. Her experience as a young womanserving in the homes of others contributed toher reputation as a fine cook and baker, with adeft hand for presentation, always laying out abeautiful table. During the reign of Catherine theGreat (1762-1796) <strong>Mennonite</strong> farmers wereencouraged to emigrate from Germany to Russiain order to teach the Russians efficient farmingtechniques and improve Russia's economy. The<strong>Mennonite</strong>s came and farmed successfully. Some becamevery wealthy and acquired large estates. Insteadof disseminating their agricultural expertiseamong the local populous they hired the Russian's ascheap labor. This was a cause of great resentmentamong lower class Russians.Helen Kliewer was born in Friesental, SouthRussia on December nineteenth, 1905. The <strong>Mennonite</strong>area of settlement in which she lived was known asthe Molotschna. Her family was not wealthy. Theydid not own land and lived in a rented house. Herparents were Sara and Johann Kliewer. In the year1913, when Helen was eight, she and her youngerbrothers Vanya and Franz became ill with scarlet fever.Helen survived the fever, though her brothersdid not. They were two and five years old. It was inthis same year that Helen's mother died of "de Rose",a poisoning of the blood. She died only four daysafter the first signs of illness. My great grandmotherspoke of too many changes. The changes of 1913were to be the prelude of a great many more.Helen's father was conscripted shortly afterthe death of her mother. As <strong>Mennonite</strong>s are pacifists,Johann served the military in the medical field.Helen and her sisters, Neta and Sara, stayed withtheir grandparents for three years while her fatherwas in service. When he returned home Johann marrieda wealthy widow in possession of the large estate,Gut Rosenheim. The girls were not overly fondof their new stepmother nor she of them. She favoredher own children above her new husband's.The children's schoolteacher stayed in a tutorageon Rosenheim, but due to the revolution and unrestshe requested to stay in the estate house whereshe shared a bed with Helen. One night Helen wasawakened by noises in the house. She sat up, startled,but was immediately pulled back down by theschoolteacher. In that instant she felt the breeze of asaber swishing above her head. The house was beingpillaged. The bandits slashed the pillows and pouredsyrup into the holes. Not only did they take whateverthey wanted, they destroyed that which they did notwant.Russia was in such chaos that bands of robbersand anarchists were able to loot, rape, and kill

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 13without any opposition. A band took Helen'sfather in 1918. His family did not find out hewas dead until a month after his death whensome Russian acquaintances told them. Theyfound his body where the Russians told them itwould be and gave him a proper burial. It isprobable that Johann Kliewer would not havebeen killed had he not remarried and acquiredan estate. One man in particular became notoriousthroughout the Molotchna. His name wasMakhno. He called himself an anarchist but tothe <strong>Mennonite</strong>s he was a bandit. My grandmotherwas forced to serve him and his bandswhen he invaded and took over Rosenheim.The older girls were kept hidden for fear of beingraped and Helen was dressed in rags anddirtied to make herself less appealing. She describedMakhno as, "a little man, strutting aboutin his stolen blue-velvet coat." Due to the revolutionand unrest Helen and what remained ofher family moved to Waldheim.In 1924, when Helen was eighteen, sayinggoodbye to her brother Julius who remained behind,she and her sisters Neta and Sara immigratedto Canada. It was on the suggestion oftheir Aunt and Uncle Klassen, who were living inSwalwell, Alberta, that they decided to leaveRussia. They could not see any future for themselvesor freedom of religion in Russia. It costHelen and Neta two hundred and forty dollarseach to travel to Canada. Sara was able to travelat half the cost because she was considered achild. On July 23 Helen's uncle, John Friesen,drove the girls to the village of Lichenau wherethey boarded a train to Moscow. They continuedtraveling by train to Peucuuja where theywere given their C.P.R (Canadian Pacific Railway)pins. Their journey through Russia tookone week. From Peucuuja they took a train toLiebau, Poland, stopping at Riga onthe way. They took a midsize ship called Baltraacross the North Sea and arrived in London,England. From London they were transported tothe city of Southampton by train. There theyboarded the ship that took them across the AtlanticOcean to Quebec City where they arrivedon August 15. From there they traveled to Calgaryand then to Swalwell where their aunts and unclesKlassen and Harder were waiting.Helen and her sisters stayed in Swalwell forthree months, separated, and working for local familiesto pay off their traveling debt. Sundays, wheneveryone gathered for church, were the only times inwhich they were able to meet and share their experiences.They worked very hard for their employers inthe house, the barn, and in the fields. Helen's relativesthen decided to move to Dundurn, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>.There they purchased a large farm on credit with anumber of other <strong>Mennonite</strong> settlers. They divided theland into sections to farm. Helen and her sistersmoved to Dundurn along with their relatives wherethey, again, were hired to help on the farms. In thisway they were able to pay off their traveling debtswithin a year. They moved, eventually, to Saskatoon,<strong>Saskatchewan</strong> and worked as domestics for theirroom and board and a small wage. Helen was hiredon by Professor Grieg and then later by W.P. Thompsonof the University of <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>.Helen met Rudolf Bergman at a wedding.Not much is known of their romance. They weremarried on July 16, 1931 at Pleasant Point church inDundurn. The reception was held in Helen's Auntand Uncle Harder's barn. They moved to the smallcommunity of Elbow, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> and farmedthere for many years. Farming was tough, especiallyduring the depression. Despite the hardship thesewere good years for my great grandmother becauseshe and her husband lived on their own land. She feltrooted. It was there that she felt, finally, safe fromchange.Written by her Granddaughter Becky RiekmanFrom Passing on the Comfort Quilt Show

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 14Passing on the ComfortBy Alma EliasBy now, many of you have heard aboutthe quilt show and matching book called‘Passing on the Comfort’. The purpose of thebook and the show was to feature fragile andfaded, yet beautiful, quilts made by women inNorth America and sent to Europe by MCC.These were then used by Russian <strong>Mennonite</strong>refugees in the Netherlands just after WorldWar II.My first impression was that the quiltswere more beautiful and more intricate than Ihad expected. One nine patch was made of 1inch squares nicely color matched. Generally,the pieces of fabric were quite small, the colorco-ordination was good and some quilts alsohad a lot of hand quilting. In other words, agreat deal of effort and time went into theircreation.To me, a handmade gift involving a lotof time and effort communicates love. I’msure these quilts did more than warm tired,travel weary bodies. I think the love and caringinvolved in their making spoke to the refugeesand helped heal their broken hearts. Thatis what makes them so special.I had the privilege of taking a grade oneclass through the display at the MCC centre.Those students who had special blankets hadbrought them along. I noticed how lovinglythey handled their quilts or blankets as I read‘The Quilt Story’ by Tony Johnston. Thenthey talked about their quilts before gluing on anine patch fabric square onto paper. It wasvery clear that the children felt the love of theperson who had given them their quilts. Thesesix and seven year olds had no trouble understandingwhy the quilt show was very important.These quilts in the display brought healingin another way. For some people the sightof the quilts in this special show gave thempermission and an openness to share their storiesabout the war. In the sharing, there washealing. As a volunteer at the display at theMCC sale, I had the privilege of listening to atearful young woman tell me how her father nevertalked about his wartime experiences until he saw aperformance of ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’. Thenhe opened up and talked all night.Apparently at least one man in every locationwhere the quilts are shown points to a particularquilt and says, “I slept under that in Holland afterthe war”.The show legitimizes the experiences of therefugees and honors the loving work of quilters. Italso demonstrates how giving to MCC comes fullcircle. I guess it’s no accident that quilts are oftencalled comforters.*************************Samples of Quilts

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 15Our Readers WriteIn the early days wells were dug by hand.Once you reached a certain depth a cribbing wasbuilt and slid down into the well to protect theworkers. It was always a big event when the spadebroke through the ground to a gushing stream ofwater. Helen and Sam Bergen live in Lacombe, Alberta.Helen is the elder sister to the well diggersshown in the snapshot. The parents were Rev. A.A.and Anna Martens. Thank you, Helen for sendingus this interesting photo.****************Cream Separator IncidentBy Tony KrahnWell DiggingHelen Bergen sent us this photo in responseto our article in the December issueasking for stories about pioneer wells.The photo shows three Martens boysdigging a well on their farm in Glenbush inabout 1944. Left to right is Walter Martens,holding a willow fork commonly used by waterwitchers to find water, Abe is hauling upthe dirt from below, and brother John is tryingto find out how many feet they have to dig tofind water, using the old rod system. (If itbobbed up and down forty times it would beforty feet to water!) The other brother wasCorny, and he must be down in the well digging.In the December 2004 issue of the <strong>Saskatchewan</strong><strong>Mennonite</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> you had a photograph ofan old cream separator and you invited readers towrite about their experiences with this equipment.The photo brought a vivid memory to me. My storyhappened shortly after my parents had come to Canadain 1927. We lived in Davidson, SK at that time.Our house was made of two granaries connected toone another by a doorway. Here is the anecdote.My parents were in the barn milking and mybrother had, what he thought, was a wonderful idea.We would all hide in the cellar and my sister wouldtell our parents that we had gone away to someplace. In any case, the parents were not particularlyworried about it. They placed the two full pails ofmilk right on top of the cellar trap door and continuedwith their chores.In the meantime, we got worried being in thedark cellar and decided to go up. As my brother Edpushed the trap door from underneath it upset bothpails of milk. There was an ocean of milk all overthe place. I don’t remember how we cleaned it upbut I recall vividly how father lined all of us up in arow and gave us a thorough paddling.That is my recollection of the cream separator!

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 16From our ArchivesBy Victor Wiebe, ArchivistOver the spring and summer Alan Guentherworked diligently in the Archives and finishedcataloguing the major manuscript collections.Alan in his graduate studies at McGill Universitygained considerable experience in usingarchives. Now he could apply these skills indescribing the contents of archival collections.For his considerable efforts the Society gaveAlan a modest grant. The final products of hisefforts are dozens of archival boxes filled withrecords and clearly labeled and a very functionalprinted “Finding Aid.” The “FindingAid” tell researchers the content of a manuscriptcollection. A preliminary aid will justnote some subjects in the collection while avery detailed finding aid may describe everypiece of paper in a collection. The descriptionsby Alan Guenther are a little less than fullydetailed and they provide a description of thecontents of each file folder and in addition noteindividual items of significant historical value.The next step is to make these finding aids accessiblethrough our internet web site.We continue to receive significant gifts ofbooks and records and we are always verypleased for these. The largest donation was thelibrary of the Sharon <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church,Guernsey, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>. This was a hugecollection of over 750 books. These werebooks typical of a <strong>Mennonite</strong> congregationallibrary and at first glance it seems that the libraryheld few <strong>Mennonite</strong> works. Upon examiningthe actual books, however, we foundover 100 books were relevant to our collections.Many of these were by <strong>Mennonite</strong> writersand dealt with such topics as devotions,adolescents, peace and social issues. In additionthe collection also contained significantFROM THEARCHIVESresources on Sharon’s Sunday School and women’sgroups.As in the past the majority of the work is accomplishedby volunteers. We are blessed by some whovolunteer each week as well as those who come astime permits.We would like to remind all our readers to keep theArchives of the <strong>Mennonite</strong> Historical Society of<strong>Saskatchewan</strong> in mind when ever disposing of records,books, photographs and even sound recording.Many items that may seem to be worthlesscan in fact be extremely valuable in documentingthe history and faith practices of <strong>Mennonite</strong>s in ourprovince.Volunteer Appreciation TeaSunday afternoon, April 10, <strong>2005</strong>, the <strong>Mennonite</strong>Historical Society of <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> honoured itsmany volunteers with an afternoon tea in the FellowshipHall of Bethany Manor. The approximately50 volunteers and former Board membersenjoyed a Seniors’ Band from Aberdeen whoplayed a number of instruments including harmonicasand a variety of songs. Victor Wiebe formallythanked the volunteers for their many hours of workdevoted to various MHSS projects. The group thenenjoyed some delicious strawberry shortcake withtheir coffee or tea as a tangible token of appreciation.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 17Story of a CarpenterBy Wayne Dueck with assistancefrom Ted RegehrIn 1942, my father, David J. Dueck,member of the Eigenheim <strong>Mennonite</strong> Churchnear Rosthern, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>, chose ConscientiousObjector’s status and was sent to severaldifferent CO Camps in Alberta and British Columbiafrom 1942 – 1944. Together with otherCOs in Camp, his days were occupied withcutting down dead trees and removing them toa location where they were no longer a firethreat, clearing out burned trees and preparingthe area for reforestation, tree planting, constructingNational Park buildings (some ofwhich remain to this day), working in theCamp Kitchen, publishing the Camp Newsletter,taking care of the Camp horse(s), organizingMen’s Choruses and Quartets, organizingSunday morning Worship Services, clippinghair (10 cents a haircut), keeping their tentsneat and tidy, and writing letters to loved onesat home.Prior to leaving for CO Camp, Dad haddeveloped an interest in woodworking and,using thin cedar boards, he created fretwork,some of which he sold for 25 cents per piece,or he gave it to individuals whom he had cometo appreciate. He continued that hobby in COCamp.Apparently, he gave away as manypieces as he sold! Because he was located inCamp Q3, near Black Creek, B.C. for sixteenmonths, most of the fretwork which Dad createdwhile in Camp was sold or given away toindividuals living in the Camp or visitors toCamp Q3.In 1943 Reverend Edward Gilmore andtwo <strong>Mennonite</strong> ministers visited various ConscientiousObjector camps, including those inBritish Columbia, to minister to the men workingthere. The two Ontario <strong>Mennonite</strong> ministersmost involved in such visitations, and thusprobably the two accompanying Reverend Gilmore,were Reverend J. B. Martin, pastor ofthe Erb Street <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church in Waterloo,and Reverend Jacob H. Janzen, pastor of the Waterloo-KitchenerUnited <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church. All Ontarioministers involved in such visitations workedin close co-operation with the Conference of HistoricPeace Churches and, of course, the governmentappointed administrators of the camps. Myfather came to know and appreciate Reverend Gilmore.He gave Reverend Gilmore a piece of fretwork,a letter holder, on which was scrolled KEEPSMILING.Nearly sixty years later, Carry and I arrived athome after work to find several messages on ourMessage Machine. One of the messages was mostunusual! Mary Fretz, Beamsville, Ontario called toinquire whether I was David J. Dueck’s son? If not,she apologized for the call. If so, I was asked tocall her as soon as possible. I called Mary Fretz andidentified myself as David J. Dueck’s son. I toldher that my father had passed away in February,1992. Mary told me that, for many years, her parentshad used a letter holder, attached to the kitchenwall, in which her father placed yet unanswered letters.As she looked at the letter holder, she rememberedhow her deceased father, Reverend EdwardGilmore, used to carefully place unopened letters inthe uniquely designed letter holder. She removedthe letter holder from the wall and noticed that onthe back was inscribed David J. Dueck, 1943. Sheknew that the letter holder had been given to herfather, but who was David J. Dueck? She called herdaughter Sandi Hannigan, Erb Street <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church and asked Sandi for assistance in locatingDavid J. Dueck. Sandi contacted Conrad Stoesz,Archivist at the <strong>Mennonite</strong> Heritage Centre in Winnipeg,Manitoba. After some research, it was discoveredthat David J. Dueck’s parents, ReverendJohann and Anna Dueck, attended and ministered inthe Rosenorter Gemeinde (later Eigenheim <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church) and had twelve children, the youngestof whom was David. In 1944, David marriedLillian Roth and together they had four children,Wayne, Marilyn, Lyle and Lois.On the telephone, Mary and I pieced togetherthe story and she told me that she wanted to give thefretwork to me. I was truly grateful for her generosityas I did not have a piece of Dad’s fretwork. Iremembered how on cold winter evenings my fathersat at the kitchen table and by the light of a smalllamp, which is displayed in the Museum on our

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 18acreage, he sawed out the designs which hehad drawn ahead of time. I was not confidentthat the fretwork which Mary was giving mewould arrive safely if sent via the mail or courier.I commented that our friend Doreen Janzen,Waterloo, would be in Rosthern for herFarm Auction Sale on April 11 th . Perhaps thefretwork could be taken to Doreen’s home inWaterloo or to Doreen’s daughter Wendy Janzen’soffice in the St. Jacob’s <strong>Mennonite</strong>Church near Waterloo. Mary was sure that herdaughter, Sandi Hannigan, whose office was inthe Erb Street <strong>Mennonite</strong> Church, the veryChurch in which Reverend Martin servedmany years earlier, knew Wendy Janzen.Regrettably, Carry and I were not able toattend the Janzen Farm Auction as, due to astorm, we were unable to leave the Denver InternationalAirport. We arrived in Saskatoonlate in the evening of April 11 th . The carefullywrapped fretwork eventually reached our homewhen Doreen presented it to us. I held thepiece of fretwork in my hands and was overcomewith memories of my father. The fretworkshall, at family gatherings, be rotatedamongst my “Geschwister”. Eventually, oneof our sons will be given their Grandfather’sfretwork. Perhaps they, too, will rotate it betweenthemselves.****************Another Well StoryBy A.G. JanzenIn the year 1913, long before I was born, myparents moved to the village of Neuanlage, at thevery south end and on the west side. The buildingswere already there, but there was no well on theyard. All water had to be hauled from the east sideof the village, where there was an ample water supplyof good quality water and at a very reasonabledepth of only 14 feet. So my Father wanted to tryand get a well dug on his yard, even if it was not ofgood quality, but maybe it would be useable for cattleand horses.So two men from the village of Blumenheimwere hired to dig the well. They were Mr. DavidFriesen and a Mr. Heinrich Fehr. A wooden wellcribbing was nailed together and let down as thework progressed, so that there should be no dangerof the walls caving in. For their meals these menwere always invited into the house to eat. Thesemen took turns digging in the well and winching upthe pail that was filled with dirt. It was slow going.They were now nearing the 100 foot depth, when itwas lunch time. So the call went out, dinner is on.This time David Friesen was down in thehole. So he had to unhook the mud pail and stepinto the loop in the rope and hold on to the ropewith his hands on the trip up to the top, which hehad often done before. But this time somethingwent wrong, The winch that was being turned byhand suddenly did not turn any more. It was seizedup, nothing could be done, it was stuck. So Mr.Fehr called to my father for help, but it was of nouse. The winch just could not be moved. So myfather said “We will take a rope, tie a ladder to it,and let the ladder down and David can step on tothe ladder and we will haul him up that way. Soseveral men were called for extra grip on that ropebut they did not realize what had happened to DaveFriesen.While he was hanging there, he looked up.It was about 50 feet to the top. He looked down. Itwas also 50 feet to the bottom and there were thetools. If he should fall, he would hurt himself onthe tools lying there, so he froze to the rope he washolding on to, and when the ladder was dangling infront of him, he could not let go of the rope. My

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 19Father said, “I never prayed as hard in my life.Here was a man’s life at stake. If he could getonto the ladder it was easy to haul him up.” Sohe told David, “Just let go of the rope and grabthe ladder,” but David said, “ I cannot do that,then I fall and I will kill myself.” And whenFather realized what was wrong with David, hesaw what a danger confronted them but hecould not let on that he was also afraid. So hesaid to David, “There’s no danger, just let gowith one hand, grab the ladder and put one footon the rung of the ladder. But to no avail, thisman was frozen with fear till father suggestedthat he close his eyes, and then try it. It took along time of talking, when finally he put onefoot out and when it touched the rung on theladder his fear vanished and he could grab theladder and step on with both feet and theyhauled him up. So when all the men walkedinto the house, Mother said David was as whiteas a sheet, and asked only "Where can I liedown?” She gave him a couch in anotherroom; he needed no food that day.After the late noon meal, for the wholething had taken over an hour, Mr. Fehr askedFather, “What do we do now?” My Father answered,“Take a rope with a hook and try tocatch the pail standing there and bring it up. Ifyou can, hook also the spade, but otherwise weare done, no one is going down there again.“What about the well?” Father said, “I willbuy a six inch steel pipe and let it down all theway, then fill in the hole with the pile of dirtlying here.” So that is what was done. Then aman was hired with a well drilling machine,and he put his drill into that pipe and workeddown for another 10 feet and we had water.This was poor water, with a lot of iron in it,very hard, but livestock drank it. In 1928 whenI was 8 years old, the crop was good, so Fatherhad a windmill installed on that well. We duga cistern inside the barn, and on windy days thewindmill had to pump till that cistern was full.That way we had water in the barn for our cattleand horses. The barn is gone; the hole withthe pipe is still there but abandoned.More Picturesfrom the Appreciation Tea—April10, <strong>2005</strong>Our “Thanks” go out to the many volunteers whospend countless hours working at the Archives , andon the <strong>Mennonite</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>, collecting andpreserving our unique <strong>Mennonite</strong> History. Also weappreciate all the people who donate the stories andmaterials that tell the story of the <strong>Mennonite</strong>s.

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 20Mostly About BooksBy Victor G. WiebeBook EditorBuilding on the Past:<strong>Mennonite</strong> Architecture, Landscape andSettlements in Russia/Ukraineby Rudy P. Friesen / Edith Elisabeth FriesenPublished in 2004 by Raduga Publications,200-2033 Portage Ave.Wpg, MB R3J 0K8raduga@shaw.caList price $45, 750 pages, soft cover.Like many Canadians with <strong>Mennonite</strong>roots, I learned the stories of <strong>Mennonite</strong> Russiaas a child in the 1940s, as my father and hisfriends shared their stories of life, hardship,and loss in the land of their birth. Havingcome to Canada in the 1920s, their experienceswere still quite fresh and vivid; and I gleanedcertain strong impressions: <strong>Mennonite</strong>s werefarmers – devoutly religious, hard working,and orderly; especially when compared to theRussian peasants. There were apparently alsosome rich <strong>Mennonite</strong> estate owners, but thesewere few and far between. Life in the villageswas good, at least until the Revolution. Therewas not much travel beyond the boundaries ofthe colony, and little reason for it.<strong>Mennonite</strong> History studies in BibleSchool in the 1950s did little to alter this perception.Life on the Canadian Prairies wassimilar - we were farmers and rural people.But then came the 60s, and with it the realizationthat not all could be farmers. There wasn’tgoing to be enough land. Suddenly therewas a rush to jobs in the cities, and to postsecondaryeducation. There had been teachersbefore, and nurses, and a few doctors; but nowsuddenly the professions became acceptable –medicine, social work, political science, engineering,architecture, and even law! I recall statisticsthat suggested that <strong>Mennonite</strong>s moved from being20% urban and 80% rural in 1950, to being 80%urban and 20% rural in by 1975! We thought wewere a new generation, turning our backs on theland and striking out in the city; integrating into andcontributing to the larger secular Canadian society.We were unique in <strong>Mennonite</strong> history!Or were we? In his new book, “Building onthe Past”, architect Rudy Friesen opens a new windowinto the Russian <strong>Mennonite</strong> experience – andgives us a view that is at times surprising and unfamiliar.This view comes from looking at 125 yearsof buildings that <strong>Mennonite</strong>s constructed betweentheir arrival in Russia in 1788, and the RussianRevolution of 1917. But this is not primarily abook about buildings, or about architecture. Buildingsare windows through which we can see intothe heart of the society that built them – and <strong>Mennonite</strong>buildings are no exception.The book opens with a chapter on the HistoricalContext, briefly outlining <strong>Mennonite</strong> historyfrom the Reformation in the 1500s to the present.This is followed by a chapter on the Evolution of<strong>Mennonite</strong> Architecture, which also parallels theevolution of <strong>Mennonite</strong> society. Five stages areidentified:Settlement – transplantation & adaptation –1789-1835Progress – reform and standardization - 1835-1880Flowering – diversity and expansion – 1880-1914Disintegration – dismantling and conversion –1914-1999Recovery – remembering and rebuilding –from 1999Through the first two stages, <strong>Mennonite</strong>s developedan orderly, highly regulated pattern of villageconstruction, beginning with the Chortitza and

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 21the Molotschna Colonies, and expanding overtime (by 1914) to include some 72 colonies orsettlements, and over 450 villages. Developmentduring this period was dominated by agriculture,but locally based manufacturing wasbeginning to emerge by the end of the period.A helpful chapter entitled “Directory of Settlements”provides a listing of all these coloniesand villages; with the following thirteen chaptersfocusing on individual colonies, providinga broad array of photographs of buildings,maps and illustrations. Some of the photosdate back to the early 1900s; while many morehave been taken within the last five to tenyears and document what remains of earlier<strong>Mennonite</strong> buildings.The third stage of development, oftencalled the “Golden Age”, brings us pictures ofa <strong>Mennonite</strong> society that we may have troublerecognizing. A few quotes from the book willillustrate the point: “The <strong>Mennonite</strong>s who remainedin Russia (after the emigration of the1870s) were able to accommodate the sweepinggovernmental reforms aimed at Russification.They developed an elaborate system ofinstitutions designed to preserve <strong>Mennonite</strong>society.” “As <strong>Mennonite</strong>s studied and traveledthroughout Russia, Europe and even NorthAmerica, they became more culturally awareand brought new styles and technologies backto the colonies, thereby influencing the style of<strong>Mennonite</strong> buildings” “….<strong>Mennonite</strong>s nowhad their own professionally trained engineersand architects…” “By this time many <strong>Mennonite</strong>shad moved to cities and become thoroughlyurbanized. Thousands had establishedgrand estates. Others had become industrialtycoons and some had entered civic and nationalpolitics.” (p. 50) “As <strong>Mennonite</strong>s outgrewtheir utilitarian and conformist approachto construction, their buildings expressed increasingcreativity, sophistication and diversity.These were buildings that spoke the languageof modernity, pride and grandeur.” (p.51)The story of the fourth stage,“Disintegration”, is probably more familiar tous. Some 15,000 <strong>Mennonite</strong>s left Russia duringthe emigration of the 1870s. Of the 100,000<strong>Mennonite</strong>s living in Russia in 1914, 21,000 left forCanada and South America during the 1920s. Some12,000 more managed to follow in the late 1940safter having fled to Germany with the retreatingGerman army. The remainder disappeared, eitherby death, exile or assimilation; along with much ofthe tangible evidence of their past.As a practicing Winnipeg architect , RudyFriesen has a keen interest in buildings, but also in<strong>Mennonite</strong> history. Since his first visit to Russia in1978, he has returned numerous times to study anddocument the built history of the <strong>Mennonite</strong> people.He has also participated in the restoration of someof these original buildings; and has identified thefinal stage, “Recovery”, as a time when, through thecooperation of Ukrainians and North American<strong>Mennonite</strong>s, a process of restoring and refurbishingsome of these original buildings has begun, as away of recovering their shared social history.The final three chapters of the book are entitled“Estates”, “Forestry Camps”, and “Urban Centres”.Each is filled with interesting and relativelyunknown details of <strong>Mennonite</strong> life during the“Golden Age”. For example, “ By 1914 there werewell over 1000 <strong>Mennonite</strong> estates in all of Russia.Their total land area was estimated to be at leastone-third of the more than 1,000,000 dessiatines(2.7 million acres) owned by <strong>Mennonite</strong>s.” TheForestry Camps, which provided a form of alternativeservice in lieu of military service in the Russianarmy, were constructed, paid for, and operated bythe <strong>Mennonite</strong>s through a special agreement withthe government. As to the chapter on “Urban Centres”,it appears that indeed, we were not the firsturban <strong>Mennonite</strong> generation!This book is an archive with a wealth of currentdetail about the <strong>Mennonite</strong> world of southernRussia that our forefathers left almost a hundredyears ago. It provides a special insight into theirlives by looking at the tangible evidence that theyleft behind – their buildings. Through the carefulaccumulation of extensive data, Rudy has left usmuch to enrich our understanding and appreciationof their legacy.By Len R. Pauls, Regina Architect

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 22Fonn Onjafaa:The Recipes of Elizabeth WiebeWiebe, Alma, editor,Generation 2 Publishers, reprinted <strong>2005</strong>, 56 pp,$15.00 (shipping, taxes included).Available from Alma Wiebe,2337 Munroe Ave. S., Saskatoon, SK, S7J1S4.Reviewed by Jake Buhler.Fonn Onjafaa, was written out of necessity. AsElizabeth Wiebe’s nine daughters were growingup and setting up their own households,they would ask their mother for recipes ofdishes they had enjoyed on their farm fourmiles east of Warman, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>. Mrs.Wiebe, speaking Low German, would alwayssay, fonn onjafaa (trans = approximately) inanswer to how many cups of flour or sugarwere needed for a given recipe. She was neverspecific, choosing to add more of this ingredient,less of another, depending on the situation,who was eating, the number of eaters, etc. Atlong last, her daughters sat down with theirmother and, as best they could, put specifics tothe dozens of recipes Mrs. Wiebe carried in herhead. The result: 95 of the finest recipes thatcan be called the core of prairie <strong>Mennonite</strong>cooking.The recipes are laid out in seven groups– soups, breads, main courses, cookies, desserts,jams and preserves, and miscellaneous.A black and white photograph showing ElizabethWiebe in action, graces each food group.The recipes are laid out simply and clearly.Often they feature a food, the ingredients forwhich were found in the pasture or in the backyard. For example, the recipe for Zuarompsmoos (sorrel moos) is:1 1/2 cups sugar1 1/3 cups flour3 quarts milkCombine ingredients. Cook 3 cups fresh sorrelcut into half inch pieces in 2 cups water forapproximately 10 minutes. Add the 3 ingredientsabove and bring to boiling point but donot boil. Remove from heat and serve.The recipes highlight the what’s whatof <strong>Mennonite</strong> cooking. From Zomma Borscht toKernell Rollen to Paapanate to Schmaunt Kuchen,the book features the traditional dishes that havesustained <strong>Mennonite</strong>s for generations. The collectionalso demonstrates how Elizabeth Wiebe improvisedand made her own recipes. Rather than throwaway the rinds of watermelon (she grew them in hergarden), she would turn them into pickles, usingdill, vinegar, salt and sugar. There are no fewer than22 jams and preserves recipes showing the utility,economy, and variety of Elizabeth’s food makingability. In the middle of winter, her family of 15children had a wide variety of preserves that weredelicious and healthy.Do the recipes meet today’s standards of nofatand sugar-free diets? In the 1930s, 40s and 50s,there were no fast-food outlets in the isolated farmingcommunities. Home cooking was all there was.The emphasis was on quality, not quantity foods.The people who ate them were physically active.Few people were overweight. There was an appropriatebalance of fat in-take and the number of caloriesburnt off. Ghriven (cracklings) were a winterstaple food. It is possible that this food would notmake it into today’s Canada Health Food Guide! Ifyou choose to make a great dish of Ghriven and potatoes,you will find it on page 27!The 8 ½ by 5 ½ inch book is presented attractivelywith 56 laminated pages held togetherwith a quality black spiral ring. An easy to followtable of contents provides an overview of the recipes.At the end of the book is a complete family treeof Elizabeth’s children, grand and great grand children.This recipe book does not follow a consistentLow German spelling pattern and a few foodsmust be guessed at. However, all have Englishnames as well. While the book does have an interestingintroduction, it would have provided thereader with valuable background, had even a cursorybackground into the development of the recipesin Prussia, Russia, and finally, the prairies ofCanada, been included.Fonn Onjafaa has collected a host ofrecipes, many of which came out of oral tradition.Its contribution to <strong>Saskatchewan</strong> <strong>Mennonite</strong> socialhistory is a fine one.The book is a must if you care for Bulkche

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 23brot, Plumenmoos and Schinkefleesch,Kjielke, Rooda Zockakuchen or Kjrespaiplatz.Elizabeth Wiebe is 95 and lives in acondominium in Bethany Manor in Saskatoon.*************LEIDING/LYDING FAMILY REUNIONBy Jim LydingThe Leiding/Lyding family reunion washeld July 26 to July 29 on the campus of MillarCollege of the Bible in Pambrun, <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>with just under 70 descendants of Solomonand Maria Leiding attending. This firstever event commenced with supper and a getacquainted evening on July 26. Wednesdaywas occupied with a crokinole tournament andother table games, much visiting and viewingphotographs, and an evening of gospel singingfollowed by a bonfire. Thursday’s highlightsincluded a photo shoot, barbecue, and a varietyprogram including singing (solos and duets), askit, readings, and tributes. The program culminatedwith a humorous play “Wanted: AHousekeeper” which included some appropriatePlattdeutsch (Low German) expressions.The reunion ended with brunch on Friday.Throughout the course of the gathering,the Leidings/Lydings enjoyed a bountiful arrayof savory food prepared and served by the collegestaff. Some traditional <strong>Mennonite</strong> dishes,like Worscht (sausage), Wrennetje(perogies),and Borscht (soup) certainly delighted the palate!All members of the second generationare deceased; however, there are still threemembers of the third generation living,namely: Mrs. Margaret (Martens) Leiding, age98, Mrs. Helen (Leiding) Funk, age 90, andMrs. Marie (Funk) Leiding, age 86. Mrs.Marie Leiding, who resides in the HerbertHeritage Manor, attended on July 28.The parents, Solomon and Maria Justina,resided for a time in the village of Neville,southeast of Swift Current. They eventuallyreturned to Manitoba where both are buried atWinkler. Samuel is buried at Swift Current, Johannat Rosenort, north of McMahon, Jacob at Wymark,and Helena at Neville.Descendants of Soloman and Maria JustinaLeiding are scattered across Canada and the UnitedStates. Eleven of their thirteen children reachedadulthood and of those eleven, six spent some timein <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>. Soloman and Maria Justina andten of their children arrived in Canada from SouthRussia in May, 1892, and settled in Manitoba.From there, some came further west into <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>.The descendants of Samuel, Johann, Jacob,and Helena still make their homes in <strong>Saskatchewan</strong>.Of the eleven children of Solomon and MariaLeiding, representatives were present from theJohn, Jake, Bill, Bart, and Sam branches with thelargest representation from John’s descendants.The consensus at the conclusion of the reunionwas that a similar get-together would occur infour or five years, with Manitoba as the location.Any readers having any information aboutany members of this family are asked to contact JimLyding, Box 13, Vanguard, SK, S0N 2V0.Solomon and Maria Leiding

SASKATCHEWAN MENNONITE HISTORIAN 24THE OSLER HISTORICAL MUSEUMBy Lea HildebrandtThe Osler Historical Museum had its originsin 1980 when a group of communityminded individuals realized that Osler and areahad innumerable artifacts that needed to bepreserved immediately before the window ofopportunity was lost forever. Since a permanentstorehouse was not available at the time,the basement of the former two-room schoolhouse,now the Town Office, was utilized as atemporary site for the various displays.Unfortunately, this venue was far fromsuitable since the area was not roomy enoughto display the artifacts in a manner appropriatefor the public to view and appreciate. Articleswere crammed into allotted spaces helter skelter,leaving scant room for people to moveabout and observe. Besides, the basement withits high humidity, was replete with the dankand musty odours so common in wet basements.A one-storey dwelling that had recentlybeen owned by J.J. Neudorf became availableand Town Council, in its wisdom, decided todonate this building for use as a permanentmuseum. The four-room house had been builtby the late George and Helen Rempel in 1942on a lot adjacent to the school yard. Since thattime, it had been purchased by J.J. Neudorfand subsequently rented to a number of youngfamilies and individuals in the early ‘90s.The building dubbed “Osler HistoricalMuseum” was now taken over by an organizationof some half dozen members who thoroughlycleaned and renovated the entire structure,turning it into a typical dwelling of the1930s and ‘40s. An enthusiastic membershipheaded by Hella Banman, Jake and MargaretLoeppky, Kathy Boldt and many other willinghands, gathered a great variety of furniture,pictures, toys, clothing, etc. Mannequins wereprocured to lend an air of authenticity to thedisplays.With the aid of an Amateur Hour andnumerous “Low German Nights”, money wasraised to properly furnish and display all mannersof materials endemic to the ‘30s and ‘40s era.In 1994, the original one-room school that hadformerly been located in the northwest corner of theschoolyard but was now resting on Third Avenuewas relocated to the Museum site by movers ArtLetkeman and Cliff Peters to a spot just east of themain Museum building. This building, Osler’s firstschool, was constructed at the turn of the 20 th . Centuryand used until 1947 when a two-room schoolreplaced it. Since then, it had been used for a greatvariety of venues and most recently as the TownOffice.Refurbishing the entire building into the originalone-room school was cost prohibitive, so it wasdecided to use the North Half of the structure as aclassroom with the remainder slated as a storagefacility. Old snapshots and photographs enabled themembership to recreate the classroom with old doubledesks, coal stove with extended stovepipes and,of course, original blackboards.Also prominently displayed were two SportsTrophies, the Crough Trophy, emblematic of ChampionshipSoftball and the Dairy Pool Trophy forTrack and Field Excellence. Both of these wereannually presented at the Warman Sports Day whenall the country schools in the Warman MunicipalityNo. 374 plus the villages of Warman and Osler andoccasionally Hague gathered for a day of sports relatedactivities. It was one of the most notable daysof the year in the pre-television era. A mannequingarbed in an Osler Monarch uniform accented thedisplay.In later years, Mrs. Lillian Pauls, a formerOsler teacher, donated many school related artifacts,pictures, papers et al to add a degree of authenticityto the various displays.As a part of Osler’s Centennial celebration in2001, the original school bell which had last restedon the two-room school was installed by Bob Neufeld,Bud Banman and others. Likewise, Bob Neufeld,our master carpenter in residence, was instrumentalin obtaining and installing 6 inch dropsidingto both buildings which were then painted as thefinal step of the restoration. The basement of themain building has been upgraded to standard aftersuffering numerous wall cave-ins.One of the most attended days of the year isthe annual ‘Midnight Madness’ event held in early