New light on ancient sites The evil behind the legend Treasures ...

New light on ancient sites The evil behind the legend Treasures ...

New light on ancient sites The evil behind the legend Treasures ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

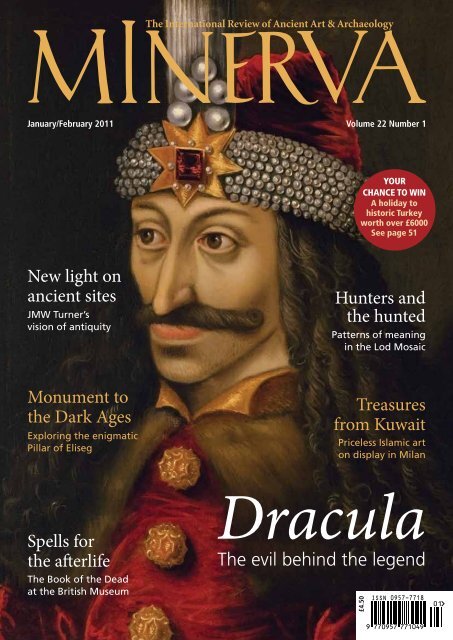

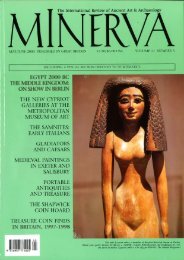

January/February 2011 Volume 22 Number 1YourCHANCE TO WinA holiday tohistoric Turkeyworth over £6000See page 51<str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>light</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><strong>ancient</strong> <strong>sites</strong>JMW Turner’svisi<strong>on</strong> of antiquityHunters and<strong>the</strong> huntedPatterns of meaningin <strong>the</strong> Lod MosaicM<strong>on</strong>ument to<strong>the</strong> Dark AgesExploring <strong>the</strong> enigmaticPillar of Eliseg<strong>Treasures</strong>from KuwaitPriceless Islamic art<strong>on</strong> display in MilanSpells for<strong>the</strong> afterlife<strong>The</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Deadat <strong>the</strong> British MuseumDracula<strong>The</strong> <strong>evil</strong> <strong>behind</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>legend</strong>£4.50ISSN 0957-7718019 770957771049

Australian heritage1 2Patricia Anders<strong>on</strong> examines <strong>the</strong>extraordinary prehistoric rock art ofWestern Australia3<strong>The</strong> world’soldestpalimpsest<strong>The</strong> Burrup Peninsula inWestern Australia, knownto <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal people asMurujuga, is a St<strong>on</strong>e Agesite which, toge<strong>the</strong>r with <strong>the</strong> islandsof <strong>the</strong> Dampier Archipelago, c<strong>on</strong>tains<strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> greatest c<strong>on</strong>centrati<strong>on</strong>s ofrock carvings found anywhere in <strong>the</strong>world. It is believed <strong>the</strong> oldest petroglyphsat <strong>the</strong> Burrup site date back30,000 years. If this is correct, <strong>the</strong>nsome of <strong>the</strong> carvings are c<strong>on</strong>temporarywith <strong>the</strong> painted images in <strong>the</strong> cavesof Chauvet (Ardèche, France) andAltamira (Cantabria, Spain), and predate<strong>the</strong> famous artwork at <strong>the</strong> LascauxCave (Dordogne, France) by about12,000 years.However, <strong>the</strong> 240 square kilometrearea has increasingly been <strong>the</strong>cause of tensi<strong>on</strong> between large multinati<strong>on</strong>almining companies seekingto exploit <strong>the</strong> rich mineral depositsfound in <strong>the</strong> area, and c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>groups attempting to preserve <strong>the</strong>unique engravings and paintings. In2003 <strong>the</strong> World M<strong>on</strong>uments Fund,a body that draws <strong>the</strong> public’s attenti<strong>on</strong>to culturally irreplaceable <strong>sites</strong>threatened by neglect, vandalism andFig 1. Upended carvingof a kangaroo from<strong>the</strong> Burrup site.Photo: Robin Chapple.Fig 2. Water bird andcrab carving from <strong>the</strong>Burrup site.Photo: Robin Chapple.Fig 3. Thylacine(Tasmanian tiger)which had becomeextinct <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>Australian mainlandby at least AD 1000.Carved at <strong>the</strong> Burrupsite. Photo: RobinChapple.Fig 4. Fish carvingfrom <strong>the</strong> Burrup site.Photo: Robin Chapple.o<strong>the</strong>r depredati<strong>on</strong>s, placed <strong>the</strong> BurrupPeninsula <strong>on</strong> its register of ‘100 MostEndangered Sites’ – <strong>the</strong> first Australianarchaeological site to be included.Despite <strong>the</strong> area’s petroglyphs beingnominated for <strong>the</strong> Nati<strong>on</strong>al HeritageList by Robert Bednarik (President of<strong>the</strong> Internati<strong>on</strong>al Federati<strong>on</strong> of RockArt Organizati<strong>on</strong>s), many of <strong>the</strong> prehistoricartworks, which number in<strong>the</strong> hundreds of thousands, have beendamaged or destroyed.<strong>The</strong> Burrup petroglyphs are apalimpsest of <strong>the</strong> spiritual and <strong>the</strong>ritualised; <strong>the</strong>y can take <strong>the</strong> form of4hopeful talismans for <strong>the</strong> hunt (Fig 8),or represent prehistoric graffiti. <strong>The</strong>reare carvings of <strong>the</strong> now extinct thylacine(Tasmanian tiger) (Fig 3), goannas(m<strong>on</strong>itor lizards), <strong>ancient</strong> speciesof fat-tailed kangaroo (Fig 1), eagles,emus, marine creatures (Fig 4) and seabirds(Fig 2). Mysterious symbols associatedwith Aboriginal cerem<strong>on</strong>ies andearth creati<strong>on</strong> stories are also depictedin many of <strong>the</strong> carvings and paintings.<strong>The</strong> Burrup Organisati<strong>on</strong> has notedthat, ‘Many motifs and some st<strong>on</strong>e featuresare c<strong>on</strong>nected to <strong>the</strong> beliefs andcerem<strong>on</strong>ial practices of Aboriginalpeople in <strong>the</strong> Pilbara regi<strong>on</strong> today. <strong>The</strong>entire Archipelago is a c<strong>on</strong>tinuous culturallandscape providing a detailedrecord of both sacred and secular lifereaching from <strong>the</strong> present back into<strong>the</strong> past, perhaps to <strong>the</strong> first settlementof Australia.’ Friends of AustralianRock Art (FARA) have also speculatedthat <strong>the</strong> site may have <strong>the</strong> oldest representati<strong>on</strong>of <strong>the</strong> human face (Fig 6). Inadditi<strong>on</strong> to <strong>the</strong> petroglyphs at Burrup,<strong>the</strong> site has a great layering of archaeologicallyinteresting objects includingcamp<strong>sites</strong>, standing st<strong>on</strong>es, quarriesand shell middens (Fig 5).12Minerva January/February 2011

Australian heritage5 67<strong>The</strong> geologist Mike D<strong>on</strong>alds<strong>on</strong>, whohas explored mineral resources inAustralia and elsewhere in <strong>the</strong> world,recently released Burrup Rock Art:Ancient Aboriginal rock art of BurrupPeninsula and Dampier Archipelago(Wildrock Publicati<strong>on</strong>s, 2010).D<strong>on</strong>alds<strong>on</strong> developed a keen interestin those remote areas of northwestAustralia, replete with <strong>the</strong> earliestpresence of humans <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tinent,and set about documenting <strong>the</strong> petroglyphsof <strong>the</strong> Burrup Peninsula and <strong>the</strong>Kimberley regi<strong>on</strong> of Western Australia.He sought <strong>the</strong> advice and approvalof some of <strong>the</strong> traditi<strong>on</strong>al Aboriginalowners of <strong>the</strong> Burrup Peninsula beforepublishing his book and, as a result,some of <strong>the</strong> images were removedbecause <strong>the</strong>y were c<strong>on</strong>sidered culturallysensitive. N<strong>on</strong>e<strong>the</strong>less, <strong>the</strong> volumestill includes 600 photographs of <strong>the</strong>petroglyphs.Despite its undoubted archaeologicalimportance, <strong>the</strong> Burrup site has <strong>the</strong>misfortune to be located near a naturalgas field, and <strong>the</strong> Northwest Shelfliquefied natural gas (LNG) industryhas been a presence in <strong>the</strong> areafor some 50 years (Fig 7). In <strong>the</strong> essayFig 5. Petroglyph siteat Burrup. Photo:Mike D<strong>on</strong>alds<strong>on</strong>.Fig 6. Arch face carvingfrom <strong>the</strong> Burrup site.Photo: Robin Chapple.Fig 7. Naturalgas z<strong>on</strong>e at Burrup.Photo: Robin Chapple.Fig 8. Carvingsdepicting emu tracksfrom <strong>the</strong> Burrup site.Photo: Robin Chapple.‘Culture Clash’, which appeared in<strong>The</strong> Australian newspaper (14 March,2009), respected journalist NicholasRothwell provided an account of <strong>the</strong>depredati<strong>on</strong>s that have taken place <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> Burrup Peninsula over <strong>the</strong> last 50years. In <strong>the</strong> late 1960s, a rail line forir<strong>on</strong> ore was c<strong>on</strong>structed, and a portand town were built <strong>on</strong> Burrup’s seawardedge. At this time a causewaywas also c<strong>on</strong>structed across <strong>the</strong> narrowstrait, c<strong>on</strong>necting Burrup with <strong>the</strong> restof Australia for <strong>the</strong> first time in 8500years. In <strong>the</strong> early 1980s Woodside’sNorth West Shelf Project also commencedand, as Rothwell notes: ‘<strong>The</strong>fate of Burrup’s rock art was not a bigfactor in those first chapters of <strong>the</strong>regi<strong>on</strong>’s transformati<strong>on</strong>, even though<strong>the</strong> extent of <strong>the</strong> peninsula’s spectacularengravings was known early <strong>on</strong>.’<strong>The</strong> debate <strong>the</strong>refore currentlyrevolves around what can best be d<strong>on</strong>eto preserve <strong>the</strong> remaining petroglyphsand o<strong>the</strong>r archaeological features of <strong>the</strong>Burrup Peninsula. <strong>The</strong> large multinati<strong>on</strong>almining group Rio Tinto, whichholds leases over part of <strong>the</strong> peninsula,has become increasingly involved withheritage c<strong>on</strong>cerns and has staff andadvisers, including archaeologist KenMulvaney, President of <strong>the</strong> AustralianRock Art Research Associati<strong>on</strong>, to8negotiate with indigenous people.Woodside, a large Australian oil andgas explorati<strong>on</strong> company, has agreedto c<strong>on</strong>sult closely with <strong>the</strong> indigenouscommunities and work around<strong>the</strong> archaeology whenever possible.Where this is deemed impractical,Woodside will relocate rocks decoratedwith petroglyphs. However, it hasbeen argued that moving any of <strong>the</strong>petroglyphs diminishes <strong>the</strong>ir significance,since <strong>the</strong>y were designed to beobserved and appreciated within specificparts of <strong>the</strong> Burrup landscape and<strong>the</strong> rock art c<strong>on</strong>stituted part of a web ofstories and cerem<strong>on</strong>ies that was understoodand celebrated by <strong>the</strong> Aboriginalcommunities over centuries and evenmillennia.In July 2008 <strong>the</strong> World ArchaeologyC<strong>on</strong>gress, held in Dublin and attendedby 1800 archaeologists, called <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>Australian Government to protectpetroglyphs threatened by a naturalgas producti<strong>on</strong> facility proposed byWoodside and <strong>the</strong> West AustralianGovernment. It was argued that <strong>the</strong>industrial development would diminish<strong>the</strong> <strong>sites</strong> against <strong>the</strong> wishes of itscustodians.In additi<strong>on</strong> to destructi<strong>on</strong> arisingfrom industrial enterprises, <strong>the</strong> Burrupsite is also vulnerable to vandals,although it could be argued that thosewho scratch <strong>the</strong>ir own designs and initialsinto <strong>the</strong> rock surfaces are merelyadding to <strong>the</strong> oldest palimpsest in <strong>the</strong>world. Some good news emerged whena short article ‘All clear for rock art’,which appeared in <strong>The</strong> Sydney MorningHerald (26 March, 2009) reported thata four-year m<strong>on</strong>itoring project hadfound no evidence that industrialemissi<strong>on</strong>s were harming <strong>the</strong> rock art.Perhaps if <strong>the</strong>se carvings survived <strong>the</strong>climate fluctuati<strong>on</strong>s associated with<strong>the</strong> last Ice Age, <strong>the</strong>y can also survive<strong>the</strong> multinati<strong>on</strong>als. nMinerva January/February 201113

4Fig 4. Funerarypapyrus of QueenNodjmet. <strong>The</strong> mainscene shows her in<strong>the</strong> form of Amun-Ra-Horakhty and Osiris.<strong>The</strong> text c<strong>on</strong>tains Bookof <strong>the</strong> Dead spellswith extracts from <strong>the</strong>Book of Caverns. 21 stdynasty. EA 10490/1.<strong>the</strong> burials of more well-to-do individuals.Workshops could make multiplecopies of <strong>the</strong> book by using <strong>the</strong>work of different scribes and pasting<strong>the</strong>m toge<strong>the</strong>r. <strong>The</strong>re can be variati<strong>on</strong>in handwriting, column width, drawingand painting (Fig 1). In many of<strong>the</strong>se texts it appears that <strong>the</strong> illustrati<strong>on</strong>swere more important than <strong>the</strong>text, as <strong>the</strong> latter was often crammedinto spaces left after <strong>the</strong> illustrati<strong>on</strong>shad already been added. Misspelled oromitted words are encountered, whileoccasi<strong>on</strong>ally images do not corresp<strong>on</strong>dwith <strong>the</strong> correct place in <strong>the</strong> text. Thisindicates a clear divisi<strong>on</strong> between specialistsin drawing <strong>the</strong> hieroglyphs andthose c<strong>on</strong>cerned with illustrati<strong>on</strong>s.Never<strong>the</strong>less, it is clear from <strong>the</strong> textsthat both <strong>the</strong> spoken and written wordswere thought to have great power. Forexample, in <strong>the</strong> Memphite <strong>the</strong>ology<strong>the</strong> god Ptah first c<strong>on</strong>ceives things inhis mind, and <strong>the</strong>n makes <strong>the</strong>m real byspeaking <strong>the</strong>ir names. <strong>The</strong> dead mustknow <strong>the</strong> names of gods and dem<strong>on</strong>sthat may be encountered during <strong>the</strong>irjourney. <strong>The</strong> phrase ‘I know you andI know your names’ is repeated oftenin <strong>the</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead. In knowing<strong>the</strong> names of deities it was thought that<strong>the</strong> spirit of <strong>the</strong> deceased could acquiresome of <strong>the</strong> power of <strong>the</strong> god. This is<strong>on</strong>e reas<strong>on</strong> why <strong>the</strong> text could occur ina variety of c<strong>on</strong>texts.<strong>The</strong> Book also changed over timeand place. <strong>The</strong> so-called Pyramid Textsof <strong>the</strong> Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC)were wholly c<strong>on</strong>cerned with <strong>the</strong> preservati<strong>on</strong>of royalty. Dating to <strong>the</strong> 5 th(2494–2345 BC) and 6 th (2345–2181BC) dynasties, <strong>the</strong> texts were not illustrated.<strong>The</strong>y dealt specifically with reuniting<strong>the</strong> king and his fa<strong>the</strong>r Ra.<strong>The</strong> texts were carved <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> wallsof tombs or sarcophagi and are wellknown from <strong>the</strong> graves at Saqarra.By <strong>the</strong> 6 th dynasty, <strong>the</strong> queen was alsoincluded in <strong>the</strong> remit of <strong>the</strong> texts.Beginning with <strong>the</strong> First IntermediatePeriod (2181–2040 BC), spells derivedfrom <strong>the</strong> Pyramid Texts were used, but<strong>the</strong>y are of a different character. <strong>The</strong>yare termed <strong>the</strong> Coffin Texts, and <strong>the</strong>yreflect <strong>the</strong> fact that by this time n<strong>on</strong>royalscould also be buried in coffinsand expect an afterlife (Fig 5). Ithas been suggested that this changewas <strong>the</strong> result of a breakdown of centralc<strong>on</strong>trol. Despite <strong>the</strong> name ‘CoffinTexts’, <strong>the</strong> spells could be rendered <strong>on</strong>a variety of surfaces, often in an abbreviatedform. At <strong>the</strong> same time, <strong>the</strong>earlier Pyramid Texts c<strong>on</strong>tinued tobe written <strong>on</strong> coffins throughout <strong>the</strong>Middle Kingdom. While <strong>the</strong> Pyramid5Fig 5. Inner coffin ofSeni (12 th dynasty 1850BC) El-Bersa, probablytomb 11. <strong>The</strong> texts <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> interior coffin areliterally Coffin Textsand are derived from<strong>the</strong> earlier Pyramidtexts. Although manycoffins survive from<strong>the</strong> period, few areinscribed with <strong>the</strong>Coffin Texts. Seniwas <strong>the</strong> chiefphysician of <strong>the</strong>governor of <strong>the</strong>Hare province inUpper Egypt.EA 30842.Figs 6a and 6b. <strong>The</strong>seillustrati<strong>on</strong>s showjust how complicated<strong>ancient</strong> Egyptianreligi<strong>on</strong> was. <strong>The</strong> sungod Ra-Horakhty(Ra-Horus of <strong>the</strong>Horiz<strong>on</strong>) is <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> left,while Sokar-Osiris is afusi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> king of<strong>the</strong> Ne<strong>the</strong>rworld andSokar, <strong>the</strong> funerarygod of Memphis.Details from <strong>the</strong>Papyrus of Nodjmet,early 21 st dynasty(c 1050 BC).EA 10541.6bTexts were focused <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> heavens,<strong>the</strong> Coffin Texts were c<strong>on</strong>cerned with<strong>the</strong> subterranean world of Osiris. <strong>The</strong>central <strong>the</strong>me is judgement, accordingto deeds in life: a clear indicati<strong>on</strong> of achange in Egyptian <strong>the</strong>ology during<strong>the</strong> Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 BC).In <strong>the</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kingdom, during whichtime <strong>The</strong>bes appears to have been <strong>the</strong>centre of redacti<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> text, <strong>the</strong>rewas even greater emphasis <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> individual.While some spells are clearlytaken from <strong>the</strong> Coffin Texts, manynew <strong>on</strong>es were added to <strong>the</strong> corpus.<strong>The</strong> earliest occurrence of Book of <strong>the</strong>6aMinerva January/February 2011 15

<strong>The</strong> organisati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> Book of<strong>the</strong> Dead was relatively straightforward.<strong>The</strong> titles of <strong>the</strong> spells, importantwords or titles, and <strong>the</strong> postscriptsof spells, could be written in red ink.Red would also be used when namingdangerous beings. <strong>The</strong> colour was alsoused to correct places in <strong>the</strong> text where<strong>the</strong> first scribe had made an error, or tocolour supplementary text that wouldexplain difficult passages.During <strong>the</strong> late 1 st century BC (<strong>the</strong>late Ptolemaic period), copies of <strong>the</strong>Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead made in <strong>the</strong> city ofAkhmim deliberately looked to <strong>the</strong>past for inspirati<strong>on</strong>. <strong>The</strong> form of writingis termed ‘retrograde’ because <strong>the</strong>figures faced right instead of left (whichwas <strong>the</strong> beginning of <strong>the</strong> text). Thismay have had some magical significance,but it may also be because <strong>the</strong>texts were copied from hieratic originalswhere <strong>the</strong> signs always faced right.Whatever <strong>the</strong> case, retrograde writingis known from <strong>the</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kingdomand <strong>the</strong> Ptolemaic periods. In laterages, however, <strong>the</strong> scribes frequentlymade mistakes, indicating that manyof <strong>the</strong>m did not fully understand <strong>the</strong>text (Fig 9). <strong>The</strong> language of <strong>the</strong> Bookof <strong>the</strong> Dead may have been very differentfrom colloquial speech, in keepingwith <strong>the</strong> language of many religi<strong>on</strong>stoday, which tends to be c<strong>on</strong>servative.In some cases it appears that <strong>the</strong>dead may have played an active part inselecting <strong>the</strong> texts that would accompany<strong>the</strong>m into <strong>the</strong> afterlife. In o<strong>the</strong>rcases it appears that books were producedin a manner resembling anassembly line. In some books it appearsthat <strong>the</strong> name of <strong>the</strong> first patr<strong>on</strong> hasbeen deliberately obscured so thatano<strong>the</strong>r name could be inserted. Insuch cases political factors may haveplayed a role, while it is also possiblethat full payment was not received for<strong>the</strong> book leading to it being sold toano<strong>the</strong>r customer (Fig 7). In rare casesit has even been suggested that <strong>the</strong>book has been illustrated by <strong>the</strong> owner(Fig 11).During <strong>the</strong> period of Maced<strong>on</strong>ianand Ptolemaic rule (332–30 BC) <strong>the</strong>Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead was replaced byo<strong>the</strong>r texts, but echoes of <strong>the</strong> past survivedinto <strong>the</strong> Roman period (Fig 10).C<strong>on</strong>sidering that <strong>the</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead,in various guises, was in use from <strong>the</strong>Old Kingdom through to <strong>the</strong> Romanperiod (c. 2686 BC–AD 395), it cansafely be said that it is <strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> mostsignificant religious texts of all time.It was first brought to <strong>the</strong> attenti<strong>on</strong>1110Fig 10. A scene from aRoman period shroud(2 nd –3 rd century AD).Here <strong>the</strong> deceasedreceives liquid froma tree goddess (Bookof <strong>the</strong> Dead spell 59).Hildesheim,Pelizaeus-Museum,LH 3l.Fig 11. Papyrus ofNebseny from <strong>the</strong> 18 thdynasty. It is knownthat <strong>the</strong> owner wasa scribe and copyistin <strong>the</strong> Temple ofPtah. This is <strong>on</strong>e of<strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>gest and bestexecuted examples of<strong>the</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Deadfrom this period. It is,atypically, executed<strong>on</strong>ly in red and blackink, and <strong>the</strong> drawingsare unusually fine.<strong>The</strong> man’s wife,parents, and childrenare named, and <strong>the</strong>children are depicted.In this scene <strong>the</strong> manand his wife receivean offering from <strong>the</strong>irs<strong>on</strong>, and beneath hischair is a c<strong>on</strong>tainerlabelled ‘holder forwriting’.of Europeans in <strong>the</strong> wake of <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>questsof Napole<strong>on</strong>, and Champolli<strong>on</strong>was a translator of parts of <strong>the</strong> text.From <strong>the</strong> early 19 th century <strong>the</strong> Bookof <strong>the</strong> Dead also began to be comparedto <strong>the</strong> Bible, although it was apparentlynot appreciated as a fixed revelati<strong>on</strong>from heaven, and did not express<strong>the</strong> tenets of a religi<strong>on</strong>. It was ra<strong>the</strong>r abook of ritual that changed over time.For understanding <strong>ancient</strong> Egyptianculture it is absolutely essential and itis <strong>the</strong>refore not surprising that muchattenti<strong>on</strong> has been devoted to studying<strong>the</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead as literature.However, <strong>the</strong>re has been relatively littleattenti<strong>on</strong> focusing <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> art illustrating<strong>the</strong> Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead. This is where<strong>the</strong> exhibiti<strong>on</strong> and accompanying catalogueat <strong>the</strong> British Museum fills animportant niche. While touring exhibiti<strong>on</strong>sfilled with objects from Egyptattract large numbers of visitors, inorder to better understand <strong>the</strong> <strong>ancient</strong>civilisati<strong>on</strong>, an exhibiti<strong>on</strong> such as thatat <strong>the</strong> British Museum is more significant.<strong>The</strong> accompanying book to <strong>the</strong>show, edited by John Taylor (who alsowrote much of <strong>the</strong> text) will also serveas an excellent volume of reference. n‘Journey to <strong>the</strong> afterlife: AncientEgyptian Book of <strong>the</strong> Dead’ runs at<strong>the</strong> British Museum until 6 March.Entrance for adults is £12, discountsare available. For more informati<strong>on</strong> +44 (0)20 7323 8299;www.britishmuseum.org.Minerva January/February 2011 17

OrientalismNeverout of printPeter A. Clayt<strong>on</strong> looks at <strong>the</strong> work ofEdward William Lane (1801–1876), pi<strong>on</strong>eerEgyptologist and Orientalist1<strong>The</strong> classical world of Greeceand Rome might be said tohave had a love/hate relati<strong>on</strong>shipwith <strong>ancient</strong> Egypt,especially after it became more accessiblefollowing <strong>the</strong> defeat of Cleopatraand Mark Ant<strong>on</strong>y at <strong>the</strong> battle ofActium in 31 BC. Ancient Egypt hadinfluenced Greek art, especially <strong>the</strong>standing male kouros figures, and for<strong>the</strong> Romans <strong>the</strong>re was <strong>the</strong> intrigue ofdeath, magic and wisdom mixed withrevulsi<strong>on</strong> at <strong>the</strong> <strong>ancient</strong> <strong>the</strong>rianthropic(animal-headed) gods. With <strong>the</strong> Arabinvasi<strong>on</strong> of Egypt in AD 640, Egypt wasessentially lost to <strong>the</strong> European world– although it c<strong>on</strong>tinued as a place ofmystery, hiding secrets in its indecipherablehieroglyphs. Renaissancescholars, most notably AthanasiusKircher (1602–80), endeavoured to‘crack <strong>the</strong> code’ arriving at ridiculoustranslati<strong>on</strong>s. It was left to <strong>the</strong> shortlivedNapole<strong>on</strong>ic c<strong>on</strong>quest of Egypt,1798–1801, to open <strong>the</strong> windows <strong>on</strong><strong>the</strong> <strong>ancient</strong> Phara<strong>on</strong>ic civilisati<strong>on</strong>. <strong>The</strong>publicati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> impressive 20 volumeDescripti<strong>on</strong> de l’Egypte, toge<strong>the</strong>rwith <strong>the</strong> writings of <strong>the</strong> Bar<strong>on</strong> VivantDen<strong>on</strong>, brought <strong>the</strong> l<strong>on</strong>g-lost m<strong>on</strong>umentsof Egypt to European eyes. <strong>The</strong>floodgates truly opened in 1822 with<strong>the</strong> decipherment of hieroglyphs byJean-François Champolli<strong>on</strong>. InitialEuropean involvement in Egypt wasmore a race to collect antiquities, oftendriven by nati<strong>on</strong>al pride. It was <strong>on</strong>lylater that dedicated scholars began toarrive. Principal am<strong>on</strong>gst <strong>the</strong>se wasEdward William Lane, a giant am<strong>on</strong>gsthis c<strong>on</strong>temporaries yet, until recently,largely overlooked.Lane was born in Hereford <strong>on</strong> 17September 1801, <strong>the</strong> fourth s<strong>on</strong> ofhis clergyman fa<strong>the</strong>r who was to diewhen Lane was <strong>on</strong>ly 12 years old. Afterattending grammar schools in Bathand Hereford, Lane began commerciallife as an engraver with his bro<strong>the</strong>rin L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, an occupati<strong>on</strong> that was tostand him in good stead in later yearswhen he would turn his skilled hand toillustrating <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>uments of Egypt.Despite his talents bad health forcedLane to leave that career. Meanwhile,<strong>the</strong> ‘Egyptomania’ that swept Britainduring <strong>the</strong> 1820s, a craze spurred <strong>on</strong>by published engravings of Egyptian2Fig 1. Lane’s clever‘birds-eye’ view of<strong>the</strong> Great Pyramid ofCheops from <strong>the</strong> topof <strong>the</strong> Sec<strong>on</strong>d Pyramidof Chephren.Fig 2. Edward WilliamLane drawn by hisbro<strong>the</strong>r Richard in1828 shortly afterreturning to England.m<strong>on</strong>uments, and especially GiovanniBelz<strong>on</strong>i’s (1778–1823) exhibiti<strong>on</strong> in<strong>the</strong> Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly during1820–21, captivated <strong>the</strong> youngLane and led him to develop a fascinati<strong>on</strong>with Egypt. He spent all hisspare time studying <strong>the</strong> country andresolved to visit its <strong>ancient</strong> <strong>sites</strong>. Hisinterest also turned to c<strong>on</strong>temporaryEgypt; he was studying Arabic by <strong>the</strong>age of 21, and three years later hadbecome c<strong>on</strong>versant with colloquialArabic. Advised that a warmer andmore c<strong>on</strong>genial climate would prove tobe more c<strong>on</strong>genial for his poor health,18Minerva January/February 2011

3 4Fig 3. While he sailed<strong>the</strong> Nile <strong>on</strong> his hiredcanjiah, Lane made hisquarters into an idealoffice and bedroom.5Fig 4. Interior ofan undergroundtomb at Saqqara.<strong>The</strong> cartouches arethose of <strong>the</strong> pharaohPsammetichus I or IIof <strong>the</strong> 26 th Dynasty(664–610 or 595–589BC). Such tombsaverage at least 10min depth before <strong>the</strong>burial chamber isreached.Fig 5. One of <strong>the</strong>several stele carvedin <strong>the</strong> cliffs marking<strong>the</strong> boundary ofAkhenaten’s newcapital, Akhetaten.This <strong>on</strong>e is <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> westbank of <strong>the</strong> Nile atTuna el Gebel.6which had fur<strong>the</strong>r deteriorated followingan attack of typhoid, Lane bookedhis passage <strong>on</strong> board <strong>the</strong> brig Findlaybound for Egypt. How Lane managedto meet <strong>the</strong> financial costs for <strong>the</strong> journeyis still something of a mystery, bu<strong>the</strong> was never<strong>the</strong>less able to pay his fareof 30 guineas (£31.50), and sailed <strong>on</strong>18 July 1825, although a severe stormdelayed his arrival at Alexandria, viaMalta, and he <strong>on</strong>ly reached Egypt <strong>on</strong>19 September. He described feeling‘like an Eastern bridegroom, about tolift <strong>the</strong> veil of his bride, and to see, for<strong>the</strong> first time, <strong>the</strong> features which wereFig 6. <strong>The</strong> great templeof <strong>the</strong> goddess Hathorat Dendera still largelyburied in sand but<strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> two finestpreserved <strong>ancient</strong>Egyptian temples,although actually of<strong>the</strong> Ptolemaic period(305–31 BC).to charm, or disappoint…’ He wasindeed to ‘lift <strong>the</strong> veil’ <strong>on</strong> <strong>ancient</strong> andmodern Egypt in his later works.<strong>The</strong> teeming city of Cairo and itsmany Islamic m<strong>on</strong>uments fascinatedLane. Within six days of his arrival inCairo, whilst waiting for his house tobe made ready, Lane paid a visit to <strong>the</strong>pyramids of Giza with a small groupof Europeans, staying overnight in anempty tomb. Bright mo<strong>on</strong><str<strong>on</strong>g>light</str<strong>on</strong>g> found<strong>the</strong>m climbing <strong>the</strong> Great Pyramid towatch <strong>the</strong> sunrise (Fig 1). Lane wasalso fortunate to meet Osman Effendi,actually a former Scottish soldierWilliam Thoms<strong>on</strong>, who had c<strong>on</strong>vertedto Islam after being captured by <strong>the</strong>Mamluk rulers of Egypt during anill-fated British military campaign in1807. Thomps<strong>on</strong> had been enslavedand, following an unsuccessful escapeattempt, faced executi<strong>on</strong> unless hechose to embrace Islam, a decisi<strong>on</strong> thatsaved his life and changed his name.Osman was a well known figure andacted as Lane’s dragoman (guide),encouraging him to adopt Turkish(Arab) dress, which would generallyallow him to pass himself off as anelite Turk ra<strong>the</strong>r than a European (FigMinerva January/February 2011 19

Orientalismhe acted as <strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> witnesses, butit gave him plenty of time to c<strong>on</strong>tinueworking up his notes and sketches.Back in England, and living withhis bro<strong>the</strong>r Richard in Regent’s Park,Lane (like Belz<strong>on</strong>i 20 years before) wasli<strong>on</strong>ised by society, c<strong>on</strong>stantly receivinginvitati<strong>on</strong>s for dinner parties.Richard, an artist and sculptor, revelledin Edward Lane’s exotic Easterndress and produced <strong>the</strong> remarkableterracotta statue of his bro<strong>the</strong>r now in<strong>the</strong> Nati<strong>on</strong>al Portrait Gallery, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>.However, his health was still troublinghim and he found <strong>the</strong> adjustment backinto British society something of a cultureshock. Never<strong>the</strong>less, he set aboutassembling his notes and material forhis manuscript, Descripti<strong>on</strong> of Egypt.Lane had begun <strong>the</strong> first draft for <strong>the</strong>book in 1829, although by <strong>the</strong> time itreached its third and final draft, it wasfour times <strong>the</strong> original length. Based<strong>on</strong> his research in Egypt between 1825and 1828, it ran to more than 300,000words, with 160 illustrati<strong>on</strong>s. WhileJohn Murray, <strong>the</strong> eminent publisher ofAlbemarle Street who had publishedBelz<strong>on</strong>i’s Narrative of Operati<strong>on</strong>s andRecent Discoveries in Egypt and Nubiain 1820, had agreed to publish Lane’smanuscript, <strong>the</strong> offer was withdrawnand Lane was unable to find ano<strong>the</strong>rpublisher willing to take <strong>on</strong> so huge awork. Thus it was held in <strong>the</strong> BodleianLibrary in manuscript form for 160years, until it was finally edited andpublished in 2000 (Fig 11).Lane returned to Egypt in 1842 andlived in <strong>the</strong> country for ano<strong>the</strong>r sevenyears, during which time he compiledhis great Arabic dicti<strong>on</strong>ary, publishedin eight volumes from 1863 to1893 (Fig 10). Lane was recognised asFig 10. Lane at work<strong>on</strong> his great Arabic-English Lexic<strong>on</strong> inHastings in 1850.Drawn by his nieceClara Sophia Lane.Fig 11. Lane’sDescripti<strong>on</strong> of Egypthas finally beenpublished 150 yearsafter he wrote it.Fig 12. At last Laneis truly recognisedin a magnificentbiography.Fig 13. Lane’s recordof <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>umentsis particularlyvaluable in view of<strong>the</strong> changes, evendestructi<strong>on</strong>, wroughtsince. <strong>The</strong> temple ofDakka was <strong>on</strong>e ofthose saved in <strong>the</strong>flooding of Nubia in<strong>the</strong> 1960s and movedto higher ground.10<strong>the</strong> leading Arabic scholar, and cameunder <strong>the</strong> patr<strong>on</strong>age of <strong>the</strong> Duke ofNorthumberland. Although his primaryc<strong>on</strong>cern was still <strong>the</strong> modernEgyptians, Lane never<strong>the</strong>less translatedand published <strong>The</strong> Thousandand One Nights (1838–40), and studiesfocused <strong>on</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r Arabic <strong>legend</strong>sand tales, as well as <strong>the</strong> Holy Qur’an.Lane was also closely associated withmany scholars of <strong>the</strong> Victorian period,including Hay and Sir John GardnerWilkins<strong>on</strong> (1797–1875), <strong>the</strong> latterhaving published his Manners andCustoms of <strong>the</strong> Ancient Egyptians inthree volumes (1837) and with manyediti<strong>on</strong>s following.Lane’s collecti<strong>on</strong> of Egyptian antiquitieswas acquired by <strong>the</strong> BritishMuseum in 1842, and <strong>the</strong> bulk of hissurviving manuscripts are held in <strong>the</strong>Bodleian Library, Oxford. He died atWorthing <strong>on</strong> 10 August 1876 and wasburied in West Norwood Cemetery,south L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>. His wife Anatasouladied <strong>on</strong> 16 November 1895, probably75 years old, and her will stipulated:‘I direct my trustees to pay to <strong>the</strong>131112authorities of <strong>the</strong> Norwood Cemeterysuch a sum of m<strong>on</strong>ey as <strong>the</strong>y requirefor insuring that <strong>the</strong> grave where I shallbe buried with my beloved husbandat Norwood Cemetery shall be keptdecently and in order.’ Unfortunately,<strong>the</strong> locati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong>ir grave is <strong>on</strong>lyroughly known as <strong>the</strong> grave markerwas 13 smashed and removed (al<strong>on</strong>g withthose of many o<strong>the</strong>r Victorian notables)in <strong>the</strong> early 1990s during a clearancecarried out by Lambeth BoroughCouncil ‘clearing away forgotten clutter’.But for all that, Lane’s name lives<strong>on</strong> in his work, recalling <strong>the</strong> <strong>ancient</strong>Egyptian prayer, ‘Speak my name thatI may live’ (Fig 12). nThis article is based <strong>on</strong>:Edward William Lane. <strong>The</strong> Life of<strong>the</strong> Pi<strong>on</strong>eering Egyptologist andOrientalist. Jas<strong>on</strong> Thomps<strong>on</strong>.L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>, 2010. x + 747pp, 55 illus.Descripti<strong>on</strong> of Egypt, Edward WilliamLane, edited by Jas<strong>on</strong> Thomps<strong>on</strong>.American University Press, Cairo,2000. xxxii + 588pp, 160 illus.Minerva January/February 2011 21

JMW Turner6foreground, and <strong>the</strong> city we survey is<strong>the</strong> Rome that Turner knew.<strong>The</strong>se two large canvases, Rome from<strong>the</strong> Vatican and Forum Romanum,for Mr Soane’s Museum (exhibited in1826) announced a preoccupati<strong>on</strong> thatwas to endure for most of Turner’s lifetime.<strong>The</strong> two pictures of Ancient andModern Rome that we have alreadylooked at testify to <strong>the</strong> excitement hefelt as late as 1839, when <strong>the</strong>y wereshown at <strong>the</strong> Academy; and <strong>the</strong>y d<strong>on</strong>ot by any means c<strong>on</strong>stitute <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>lyevidence of his c<strong>on</strong>cern with <strong>the</strong> cityand its history.In 1836 he had shown Rome fromMount Aventine, and in 1838 ano<strong>the</strong>rpair, Ancient Italy – Ovid banished fromRome (Fig 9), and Modern Italy – <strong>the</strong>Pifferari. <strong>The</strong> latter is a rural scene, setagainst <strong>the</strong> backdrop of an imaginaryTivoli; <strong>the</strong> former a grand harbourwith serried terraces of grand classicalbuildings – it might be <strong>the</strong> same settingas Agrippina – from which Ovid is hurriedaway surreptitiously at sunset. <strong>The</strong>great poet who in his Metamorphosescollected <strong>the</strong> <strong>legend</strong>s and folklore ofa rural populati<strong>on</strong> is c<strong>on</strong>trasted with<strong>the</strong> rustic music of <strong>the</strong> modern pifferari,<strong>the</strong> peasant pipers who haunt <strong>the</strong>countryside – and at certain times of<strong>the</strong> year <strong>the</strong> cities too.Turner’s interest in <strong>the</strong> literary andmusical c<strong>on</strong>tent of <strong>the</strong> landscapes tha<strong>the</strong> painted began early in his career.He was quoting from Milt<strong>on</strong>’s ParadiseLost and Thoms<strong>on</strong>’s Seas<strong>on</strong>s, as wellFig 6. Dido buildingCarthage, 1815. Oil<strong>on</strong> canvas. H. 156.6cm,W. 231.8cm Nati<strong>on</strong>alGallery, L<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>.Fig 7. Snow storm:Hannibal and hisarmy crossing <strong>the</strong>Alps, 1812. Oil <strong>on</strong>canvas. H. 14.6cm,W. 23.7cm. Tate.7as several modern poets – Akenside,Gray or Mallet, for instance – as so<strong>on</strong>as <strong>the</strong> Academy’s rules allowed him tocite <strong>the</strong>m in his catalogue entries. Helater quoted extensively from Scott,Byr<strong>on</strong> and Rogers, and composed hisown verses to accompany many of hispictures. As a young man he acquired acompendium of <strong>the</strong> Works of <strong>the</strong> BritishPoets, published by Robert Anders<strong>on</strong>in 1795, and this included a largeamount of classical poetry in translati<strong>on</strong>,including Hesiod, <strong>The</strong>ocritus,Sappho, Musaeus and Lucretius. We<strong>the</strong>refore need not be surprised tha<strong>the</strong> cites <strong>the</strong> Hymn of Callimachus whenexhibiting his Apollo and Pyth<strong>on</strong> in1811, or <strong>the</strong> Iliad when illustratingChryses praying to <strong>the</strong> sun in a watercolourof <strong>the</strong> same year: he of coursepossessed Pope’s famous translati<strong>on</strong> ofHomer, and Dryden’s of Virgil.His landscapes are indeed completeexpressi<strong>on</strong>s of <strong>the</strong> cultural life of <strong>the</strong>places <strong>the</strong>y depict – <strong>the</strong>y are, in animportant sense, always topographical;<strong>the</strong> imaginary scenes from antiquityare as vividly circumstantial as <strong>the</strong>views of modern Rome, Tyneside orL<strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>. For his painting of Palestrina(shown in 1830) he composed versesthat specifically elaborate <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> town’sheroic past, and associati<strong>on</strong> withHannibal:24Minerva January/February 2011

Military heritageMarching to <strong>the</strong>Roman beatMike Knowles takes Minerva inside <strong>The</strong> Ermine Street Guard,<strong>the</strong> society dedicated to replicating <strong>the</strong> arms and drills of <strong>the</strong>Roman imperial armySince its formati<strong>on</strong> in 1972,<strong>the</strong> Ermine Street Guard hasbecome firmly established as<strong>the</strong> leading society dedicatedto rec<strong>on</strong>structive research into <strong>the</strong>Roman Army as it existed around <strong>the</strong>time of <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>quest of Britain in AD43. A registered charity, with membersdrawn from a wide social andprofessi<strong>on</strong>al base, and an age rangerunning from 18 to 74, <strong>the</strong> Guard isfinanced through public events, educati<strong>on</strong>alvisits and d<strong>on</strong>ati<strong>on</strong>s. It is bestknown for staging displays at majorRoman <strong>sites</strong> throughout Britain andEurope, in which <strong>the</strong> audience is givenan explanati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> roles of <strong>the</strong> officers,legi<strong>on</strong>aries, auxiliaries and cavalrywho made up <strong>the</strong> Roman Army, aswell as dem<strong>on</strong>strating <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>and use of military equipment from2000 years ago. <strong>The</strong> Guard’s highlyaccurate interpretati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> Romanmilitary has proved extremely popularwith <strong>the</strong> general public, as well aswith academics, who value <strong>the</strong> insightsinto lifestyle and equipment that it provides.Remarkably, some 90 percent of<strong>the</strong> equipment is made by Guard members<strong>the</strong>mselves, to high standards ofFig 1. Br<strong>on</strong>ze orbrass helmet of <strong>the</strong>Weisenau/NijmegenType, with a widelyflaring neck-guard andl<strong>on</strong>g, heavily embossedeyebrows. 1 st centuryBC – 1 st century AD.H. 19cm (+21cm forcheekpieces). Weight1.3kg. Artefacts such asthis form <strong>the</strong> basis for<strong>the</strong> exacting replicasproduced by <strong>the</strong>Ermine Street Guard.Photo: courtesy of <strong>the</strong>Mougins Museum ofClassical Art.Fig 3. On <strong>the</strong> move.Members of <strong>the</strong>Ermine Street Guarddem<strong>on</strong>strate Romanmarching procedure.Fig 4. <strong>The</strong> Ermine StreetGuard dem<strong>on</strong>strate<strong>the</strong> famous tortoise(testudo) formati<strong>on</strong>in <strong>the</strong> Romanamphi<strong>the</strong>atre atCaerle<strong>on</strong>, south Wales.workmanship and accuracy, and is c<strong>on</strong>tinuallybeing added to and upgradedas new informati<strong>on</strong> and funds becomeavailable. In fact, <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ly major pieceof equipment which has to be farmedout to a skilled armourer (and that toan associate member of <strong>the</strong> Guard) is<strong>the</strong> basic unfinished helmet bowl, <strong>the</strong>beating out of which is highly specialisedwork (Fig 1).<strong>The</strong> highly detailed and preciserec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>s of armour and equipmentused by <strong>the</strong> Guard are primarilybased <strong>on</strong> those in use during <strong>the</strong> latterhalf of <strong>the</strong> 1 st century AD, <strong>the</strong> periodwhen <strong>the</strong> legi<strong>on</strong>s steadily expanded<strong>the</strong> province of Britannia in a series ofcampaigns against <strong>the</strong> Ir<strong>on</strong> Age tribesthat inhabited <strong>the</strong> island. However,equipment and weap<strong>on</strong>ry dating too<strong>the</strong>r Roman periods is reproduced by<strong>the</strong> Guard for both experimental anddisplay purposes. <strong>The</strong> rec<strong>on</strong>structedequipment is primarily based <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>accounts and treatises provided by<strong>ancient</strong> writers which relate to Romanmilitary matters. Authors such asJulius Caesar, Tacitus, Suet<strong>on</strong>ius, DioCassius and Vegetius all provide informati<strong>on</strong>c<strong>on</strong>cerning <strong>the</strong> weap<strong>on</strong>ry andequipment utilised by Roman soldiers,and also how <strong>the</strong> soldiers were trainedand expected to organise and functi<strong>on</strong>in battle. Unfortunately no originalRoman army drill manual exists,so <strong>the</strong> Guard has adapted commandsfrom drill manuals of early Englisharmies, although all orders are given inLatin. <strong>The</strong> Guard attempts to maintainhigh levels of accuracy when reproducing<strong>the</strong> kit of <strong>the</strong> imperial RomanArmy. This is achieved through studyof artefacts and depicti<strong>on</strong>s of Romansoldiers which survive from antiquity,finds recently unear<strong>the</strong>d duringarchaeological excavati<strong>on</strong>s, andthrough maintaining excellent relati<strong>on</strong>shipswith museums and <strong>the</strong> academiccommunity. <strong>The</strong> high level ofaccuracy demanded of <strong>the</strong> Guard’sequipment also allows <strong>the</strong> society tocarry out experimental archaeology.1 3C<strong>on</strong>structing and wearing <strong>the</strong> replicaarmour has high<str<strong>on</strong>g>light</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed <strong>the</strong> stresspoints where fittings are most likelyto suffer breakages, and mirror findsof armour recovered from Romanexcavati<strong>on</strong>s, with breakages in <strong>the</strong>same locati<strong>on</strong>s. Such are <strong>the</strong> levels ofau<strong>the</strong>nticity in <strong>the</strong> Guard’s clothing,weap<strong>on</strong>s and armour, that <strong>the</strong> Guardis also often commissi<strong>on</strong>ed to appearin film and televisi<strong>on</strong> documentariesrequiring portrayals of Roman soldiers.Members also provide assistanceto schools, universities, and o<strong>the</strong>r educati<strong>on</strong>alestablishments engaged inteaching aspects of Roman life.26Minerva January/February 2011

Military heritagesharp ir<strong>on</strong>, eleven inches (279mm) or afoot l<strong>on</strong>g, and were called piles. When<strong>on</strong>ce fixed in <strong>the</strong> shield it was impossibleto draw <strong>the</strong>m out, and whenthrown with force and skill, <strong>the</strong>y penetrated<strong>the</strong> cuirass without difficulty.’<strong>The</strong> Legi<strong>on</strong>ary would <strong>the</strong>n advancewith his shield up and short swords(gladii) pointed forwards. Instead ofbeing used as ra<strong>the</strong>r inefficient slashingweap<strong>on</strong>s, which would expose <strong>the</strong>soldier’s side to <strong>the</strong> enemy, <strong>the</strong> Romangladius was primarily intended for useas a stabbing weap<strong>on</strong>, ra<strong>the</strong>r like a bay<strong>on</strong>et(Fig 8).Artillery weap<strong>on</strong>s used in Britain ando<strong>the</strong>r parts of <strong>the</strong> Empire were initiallyderived from Greek designs, which <strong>the</strong>Romans adapted and improved up<strong>on</strong>.Despite dating back some two millennia,<strong>the</strong>se machines are still impressive:using experimental archaeology,<strong>the</strong> Guard has recreated some, and itregularly shoots <strong>the</strong>se during displays,where <strong>the</strong>y prove extremely popularto <strong>the</strong> watching public. <strong>The</strong> power for<strong>the</strong>se weap<strong>on</strong>s was obtained by usingsinew, rope or hair in torsi<strong>on</strong>, which,when released, could hurl projectilesover c<strong>on</strong>siderable distances.<strong>The</strong> <strong>on</strong>ager (named after <strong>the</strong> wild ass,which kicks up st<strong>on</strong>es to defend itself)could throw a large rock in a parabolahundreds of metres (Fig 6). Writingin <strong>the</strong> 4 th century AD, AmmianusMarcellinus provides a useful descripti<strong>on</strong>of <strong>the</strong> siege engine: ‘<strong>The</strong> <strong>on</strong>ager’sframe is c<strong>on</strong>structed from two beamsof oak, which curve into humps. In<strong>the</strong> middle <strong>the</strong>y have large holes boredthrough <strong>the</strong>m, in which str<strong>on</strong>g sinewropes are stretched and twisted. A l<strong>on</strong>garm is inserted between <strong>the</strong> bundle ofrope, with a pin and a pouch at <strong>the</strong> end.It strikes <strong>on</strong> a huge buffer with a sackstuffed with fine chaff and secured bytight binding. When it comes to combat,a round st<strong>on</strong>e is placed in <strong>the</strong>pouch and <strong>the</strong> arm is winched down.<strong>The</strong> master artilleryman <strong>the</strong>n strikes<strong>the</strong> pin with a hammer, launching <strong>the</strong>st<strong>on</strong>e towards its target.’6Fig 6. Members of<strong>The</strong> Ermine StreetGuard winch back <strong>the</strong>throwing arm of an<strong>on</strong>ager.Fig 7. <strong>the</strong> Romanarmy campaign campwith a hand stitchedc<strong>on</strong>tubernium eightmantent to <strong>the</strong> rear.Fig 8. Roman ir<strong>on</strong>short swords (gladii)used for close combat.Date: 1 st –3 rd centuryAD. Dimensi<strong>on</strong>s (fromtop to bottom):L. 65cm; L. 57cm;L. 68cm; L. 65.5cm.Photo: courtesy ofMougins Museum ofClassical Art.87O<strong>the</strong>r artillery pieces used by <strong>the</strong>Roman military included <strong>the</strong> ballista,which hurled st<strong>on</strong>es with a flattertrajectory than <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>ager, whilst<strong>the</strong> catapulta, similar to a crossbow,was capable of firing ir<strong>on</strong>-tippedbolts with sufficient force to penetratearmour at l<strong>on</strong>g distances (Figs 6, 9).A bolt fired from a catapulta can beseen in Dorchester Museum, whereit remains embedded in <strong>the</strong> spine of<strong>on</strong>e of <strong>the</strong> defenders of <strong>the</strong> great hillfort of Maiden Castle, captured by soldiersof Legio II Augusta, commandedby <strong>the</strong> future emperor Vespasian during<strong>the</strong> Claudian c<strong>on</strong>quest of Britain.Last summer, large numbers of heavyir<strong>on</strong> bolts were also unear<strong>the</strong>d byarchaeologists working near <strong>the</strong> townof Oldenrode in Sax<strong>on</strong>y, at <strong>the</strong> siteof a 3 rd century battle fought againsthostile German tribes (See Minerva,November/December, 2010, p. 4).Roman tent lea<strong>the</strong>r found atVindolanda and Carlisle provided <strong>the</strong>impetus for <strong>the</strong> Guard to rec<strong>on</strong>structan au<strong>the</strong>ntic tent intended for <strong>the</strong>eight soldiers of <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tubernium. In1993, with informati<strong>on</strong> provided byProf Carol van Driel-Murray of <strong>the</strong>University of Amsterdam, two societymembers completed <strong>the</strong> mammothtask of hand-sewing 70 goatskinstoge<strong>the</strong>r following <strong>the</strong> original waterproofstitching pattern found <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>preserved fragments of Roman tentlea<strong>the</strong>r, a process that took about 800hours to complete. A sec<strong>on</strong>d goatskintent was made some four years later,using a larger team of workers. As faras is known, <strong>the</strong>se remain <strong>the</strong> <strong>on</strong>lyaccurately hand stitched c<strong>on</strong>tubernia28Minerva January/February 2011

tents anywhere in <strong>the</strong> world, and <strong>the</strong>yare an important part of <strong>the</strong> staticdisplay for <strong>the</strong> Ermine Street Guard,forming <strong>the</strong> centrepiece of <strong>the</strong> Romanarmy campaign camp (Fig 7). Herefood is cooked over an open fire, and<strong>the</strong> public can learn more about <strong>the</strong>diet and type of rati<strong>on</strong>s c<strong>on</strong>sumed byRoman soldiers. O<strong>the</strong>r replicated toolsand artefacts help to explain <strong>the</strong> soldier’sdaily life, with a surge<strong>on</strong>’s set offield medical instruments of particularinterest (Fig 9) A ‘touch table’ gives <strong>the</strong>public – especially enthusiastic children– <strong>the</strong> chance to handle armourand equipment (Fig 12).Over <strong>the</strong> past 38 years <strong>The</strong> ErmineStreet Guard has displayed at all <strong>the</strong>major Roman <strong>sites</strong> in Britain, includingall those <strong>on</strong> Hadrian’s Wall,Richborough, Portchester, Fishbourne,Wroxeter and Caerle<strong>on</strong>, often workingclosely with instituti<strong>on</strong>s such as <strong>the</strong>English Heritage Events Unit, whichusually requests <strong>the</strong> Guard appearat three or four of its Roman <strong>sites</strong>each year. <strong>The</strong> Guard also makes frequentvisits to leading museums andhas also marched down <strong>the</strong> hallowedsteps of <strong>the</strong> Royal Military Academy,Sandhurst, although, ra<strong>the</strong>r surprisingly,it has yet to display in Italy.Members of <strong>the</strong> Guard have alsoappeared in many televisi<strong>on</strong> documentaries,and have taken part in five of<strong>the</strong> highly popular Time Team archaeologicalprogrammes. During <strong>on</strong>e of<strong>the</strong>se, filmed at Cirencester, <strong>the</strong> newlyc<strong>on</strong>structed Roman crane (trispastos)lifted a half-t<strong>on</strong>ne st<strong>on</strong>e column <strong>on</strong> itsfirst trial. <strong>The</strong> Guard has also been usedby documentary film-makers for programmesrequiring Roman military,depicting events such as <strong>the</strong> Boudiccanrevolt of AD 60, <strong>the</strong> toughest challenge129 10<strong>the</strong> Roman Army had to face in Britainduring <strong>the</strong> 1 st century AD. While filminga battle scene at Butser AncientFarm in Hampshire, sou<strong>the</strong>rn England,despite <strong>the</strong> careful battle choreography,blunted weap<strong>on</strong>s and lack of aggressiveintent, three Celtic warriors werenever<strong>the</strong>less accidentally injured, tworeceiving puncture wounds and <strong>the</strong>o<strong>the</strong>r suffering a c<strong>on</strong>cussi<strong>on</strong>. Oneparticularly striking scene involved alegi<strong>on</strong>ary dragging a Celtic woman byher hair through <strong>the</strong> mud, aptly illustrating<strong>the</strong> brutal discipline requiredof Roman soldiers and also emphasisingquite clearly <strong>the</strong> superior grip ofRoman hob-nailed sandals (caligae)over <strong>the</strong> footwear favoured by <strong>the</strong>women of <strong>the</strong> Iceni tribe, and indeedmost of <strong>the</strong>ir British opp<strong>on</strong>ents.However, far from being glamorous,filming is highly repetitive and cancause great discomfort while filming in<strong>the</strong> rain leads to <strong>the</strong> drudgery of cleaningrusty equipment. In fact, <strong>the</strong> equipmentrusts very easily, with sweatyfinger marks <strong>the</strong> worst to remove. Tocompletely deep clean and furbish a setof Legi<strong>on</strong>ary armour and equipmentusually takes about six hours. To preventcorrosi<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> campaign <strong>the</strong> metalswould have been smeared with olive oilor beeswax. However, <strong>the</strong> Guard is primarilydedicated to display and we canbe fairly certain that <strong>the</strong> Roman fieldarmy would not have felt <strong>the</strong> need tomaintain such a high standard of polishand gloss.Now in its 40 th year, <strong>The</strong> ErmineStreet Guard is able to parade nearly 50Roman legi<strong>on</strong>aries, auxiliaries andcavalry, all fitted out in armour andcarrying equipment and weap<strong>on</strong>ryc<strong>on</strong>structed to exacting standards. <strong>The</strong>Guard also publishes its own occasi<strong>on</strong>alperiodical, Exercitus, whichc<strong>on</strong>tains c<strong>on</strong>tributi<strong>on</strong>s from academicsand society members featuring diversearticles about topics relating to Romanlife, <strong>the</strong> army, military equipment and11Fig 9. In additi<strong>on</strong> toweap<strong>on</strong>ry used by<strong>the</strong> Roman military,replicated tools andinstruments crucial to<strong>the</strong> efficient operati<strong>on</strong>of <strong>the</strong> army, such as asurge<strong>on</strong>’s medical kit,are displayed by <strong>the</strong>Guard.Fig 10. Legi<strong>on</strong>ary of<strong>the</strong> 1 st century AD. <strong>The</strong>Ermine Street Guardtakes meticulous carein ensuring <strong>the</strong> armsand armour are asaccurate as possible.Fig 11. <strong>The</strong> ErmineStreet Guard <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong>march.Fig 12. <strong>The</strong> ‘touchtable’ is a popularattracti<strong>on</strong>, especialywith children,providing <strong>the</strong>m witha chance to handleRoman armour andtools.specialist rec<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong> methods used.To any<strong>on</strong>e interested in rec<strong>on</strong>structivearchaeology <strong>the</strong> Guard offers a uniqueand absorbing opportunity to relive<strong>the</strong> life of a Roman soldier in a criticalperiod in <strong>the</strong> development of our way oflife. <str<strong>on</strong>g>New</str<strong>on</strong>g> members who share an interestin <strong>the</strong> aims of <strong>the</strong> society are alwayswelcome. Full members are suppliedwith armour at no cost to <strong>the</strong>m and areencouraged to assist in <strong>the</strong> producti<strong>on</strong> ofGuard equipment. Associate membershipis available to those who are unableto play an active role but wish to keepupdated <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Roman army and support<strong>the</strong> work of <strong>the</strong> Society. Fur<strong>the</strong>rinformati<strong>on</strong> can be found <strong>on</strong>line atwww.erminestreetguard.co.uk nMike KnowlesCornicularius, Ermine Street Guard<strong>The</strong> author would like to thank ChrisHaines, Chairman and Centuri<strong>on</strong>of <strong>The</strong> Ermine Street Guard, whoseeditorial in Exercitus vol. 3 no. 6provided informati<strong>on</strong> for this article.Minerva January/February 2011 29

Roman artelephant, a giraffe and a rhinoceros,all of which were rarely seen in lifeand equally rarely depicted in Romanart. Such animals were captured andbrought to Rome for games in <strong>the</strong>arena. <strong>The</strong> giraffe, for example, wasfirst seen during <strong>the</strong> triumphal gamesheld by Julius Caesar in 46 BC. <strong>The</strong> rhinocerosfirst appears <strong>on</strong> br<strong>on</strong>ze coinsminted at Rome by Domitian (r. AD81–96), suggesting this was <strong>the</strong> earliestoccasi<strong>on</strong> such a creature had been seenin <strong>the</strong> imperial capital.Below, and <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> same axis as <strong>the</strong>central medalli<strong>on</strong>, is a scene with twofemale pan<strong>the</strong>rs clinging like largezoomorphic handles to <strong>the</strong> sides ofa large vase or krater (Fig 11). Whileall <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r large cats <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> LodMosaic are engaged in activities thatcame naturally to <strong>the</strong>m, <strong>the</strong>se two arecertainly not. <strong>The</strong> strange positi<strong>on</strong>ingof <strong>the</strong> two animals may be <strong>the</strong> resultFig. 6. A large predatorabout to eat a smallerfish <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> marine 6panel, Lod Mosaic.Fig. 7. <strong>The</strong> ketosflanked by a pair ofli<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> octag<strong>on</strong>almedalli<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong>central panel,Lod Mosaic.Fig. 8. Oceanus andketos <strong>on</strong> a Romanmarble sarcophagus,Severan, c. AD 190–200. <strong>The</strong> MetropolitanMuseum of Art, Gift ofJoseph V. Noble, 1956(56.145). Image © <strong>The</strong>Metropolitan Museumof Art.7of <strong>the</strong> pan<strong>the</strong>r’s frequent associati<strong>on</strong>with Di<strong>on</strong>ysus, which is illustrated byseveral objects in <strong>the</strong> MetropolitanMuseum’s permanent <strong>on</strong>-view collecti<strong>on</strong>.Indeed, <strong>the</strong> famous Badmint<strong>on</strong>Sarcophagus, which features Di<strong>on</strong>ysusriding in triumph <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> back of afemale pan<strong>the</strong>r, is displayed in <strong>the</strong>Shelby White and Le<strong>on</strong> Levy Court,immediately in fr<strong>on</strong>t of <strong>the</strong> Lod Mosaic(Fig 9). <strong>The</strong> inclusi<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> scene with<strong>the</strong> large krater can <strong>the</strong>refore be seen asa reference to <strong>the</strong> world of Di<strong>on</strong>ysiacbeliefs and to <strong>the</strong> prosperity and wellbeingthat it engendered.Finally, each corner of <strong>the</strong> mainsquare panel is decorated with twodolphins, facing each o<strong>the</strong>r to ei<strong>the</strong>rside of a trident (Fig 12). <strong>The</strong>y maysimply be generic motifs, but <strong>the</strong>y doseem to underline <strong>the</strong> c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> with<strong>the</strong> sea, al<strong>on</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> ketos and <strong>the</strong>cargo ships. Perhaps it is not too farfetchedto suggest that <strong>the</strong> wealthyowner of <strong>the</strong> Lod Mosaic may havemade his m<strong>on</strong>ey as a ship owner. Histrade: transporting valuable wild animalsfrom Africa and elsewhere for <strong>the</strong>spectacular animal hunting shows <strong>the</strong>Roman public enjoyed so much as partof <strong>the</strong> gladiatorial games. Why such aman should reside in a place like Lod,however, remains a mystery. As to <strong>the</strong>questi<strong>on</strong> of whe<strong>the</strong>r he was Jewish, thistoo cannot be answered c<strong>on</strong>clusively,but it seems unlikely. If he had been,it would seem natural for him to havewished to include some overtly Jewishsymbols <strong>on</strong> his expensive floor mosaics.If, however, he was a pagan, he mayhave decided to exclude representati<strong>on</strong>sof human figures in deference tohis Jewish neighbours, friends, and visitors.After all, he probably had to c<strong>on</strong>ductbusiness with many local Jews.<strong>The</strong> Lod Mosaic clearly provides <strong>the</strong>impressi<strong>on</strong> that <strong>the</strong> patr<strong>on</strong> who commissi<strong>on</strong>ed<strong>the</strong> floor had bought into,prospered, and benefited from <strong>the</strong>Roman way of life. <strong>The</strong> very Romannature of <strong>the</strong> various motifs that adorn<strong>the</strong> mosaic is best illustrated by parallelsfound <strong>on</strong> terracotta oil lamps. <strong>The</strong>se8ubiquitous and utilitarian objects weremass-produced in reusable mouldsand often had figures and o<strong>the</strong>r designs<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> central discus. A cursory surveyof any corpus of Roman lamps willturn up examples decorated with scallopshells, dolphins, birds perched <strong>on</strong>branches, peacocks displaying <strong>the</strong>irtail fea<strong>the</strong>rs, hares eating grapes, bulls,li<strong>on</strong>s attacking stags or mules, leopardsand pan<strong>the</strong>rs, elephants, andeven rhinoceroses. <strong>The</strong> last is highlyunusual but an example exists in <strong>the</strong>Metropolitan Museum’s own CesnolaCollecti<strong>on</strong> from Cyprus, and depicts arhinoceros attacking or, perhaps, eventossing a li<strong>on</strong> or ano<strong>the</strong>r type of largecat (Fig 13). <strong>The</strong> reas<strong>on</strong> for this aggressivebehaviour is explained by <strong>the</strong> smallcreature perched up in <strong>the</strong> tree <strong>behind</strong><strong>the</strong> rhinoceros. This may be taken,with artistic licence, to represent a32Minerva January/February 2011

Roman art109Fig. 9. Di<strong>on</strong>ysusriding a pan<strong>the</strong>r<strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> Badmint<strong>on</strong>Sarcophagus, Roman,c. AD 260–270.<strong>The</strong> MetropolitanMuseum of Art,Purchase, JosephPulitzer Bequest, 1955(55.11.5). Image © <strong>The</strong>Metropolitan Museumof Art.Fig. 10. <strong>The</strong> octag<strong>on</strong>almedalli<strong>on</strong> in <strong>the</strong>central panel, LodMosaic.Fig. 11. Krater withfemale pan<strong>the</strong>rs, LodMosaic.Fig. 12. Dolphins andtrident scene from <strong>on</strong>eof <strong>the</strong> corners of <strong>the</strong>central panel,Lod Mosaic.Fig. 13. Romanterracotta oil lampfrom Cyprus, first halfof 1 st century AD <strong>The</strong>Metropolitan Museumof Art, <strong>The</strong> CesnolaCollecti<strong>on</strong>, Purchasedby subscripti<strong>on</strong>,1874–76 (74.51.2162).Image © <strong>The</strong>Metropolitan Museumof Art.After <strong>the</strong> Metropolitan Museum, <strong>the</strong>Lod Mosaic exhibiti<strong>on</strong> will travelto <strong>the</strong> Legi<strong>on</strong> of H<strong>on</strong>or, Fine ArtsMuseums of San Francisco (April23–July 24, 2011), <strong>the</strong> Field Museum,Chicago, and <strong>the</strong> Columbus Museumof Art, Columbus, Ohio (dates tobe announced) before returningto Israel. <strong>The</strong>re it will be housed in<strong>the</strong> Shelby White and Le<strong>on</strong> LevyLod Mosaic Center, which willopen to <strong>the</strong> public in 2012/13. Foradditi<strong>on</strong>al informati<strong>on</strong>, includinga video about <strong>the</strong> discovery andc<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> of <strong>the</strong> mosaic, see <strong>the</strong>Metropolitan Museum’s website(www.metmuseum.org/special/index.asp) and a dedicated website createdby <strong>the</strong> Israel Antiquities Authority(www.lodmosaic.org).Photographs courtesy of <strong>the</strong> IsraelAntiquities Authority and <strong>The</strong>Metropolitan Museum of Art. <strong>The</strong>author would like to especially thankMiriam Avissar and Jacques Neguer.Dr Chris Lightfoot is Curator,Department of Greek and Roman Art,<strong>The</strong> Metropolitan Museum of Art.11 12baby rhino that has fled <strong>the</strong>re to escape<strong>the</strong> li<strong>on</strong>. <strong>The</strong> appearance of such motifs<strong>on</strong> objects as cheap and mundane asmould-made lamps dem<strong>on</strong>strates that<strong>the</strong>re was a repertoire of popular subjectsshared throughout <strong>the</strong> empire, atalmost every level of society. <strong>The</strong> fortuitoussurvival of <strong>the</strong> Lod Mosaic, itscareful excavati<strong>on</strong> and skilful c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>,and its present display to <strong>the</strong>public, allow us a new insight into <strong>the</strong>pervasiveness of Roman art. n13Minerva January/February 2011 33

British archaeologyMyth and memoryin <strong>the</strong> Welsh landscapeJuly 2010 saw <strong>the</strong> start of ‘Project Eliseg’, a new research programme that aims toexplore <strong>the</strong> famous and enigmatic Pillar of Eliseg. By Prof Howard Williams1image: By permissi<strong>on</strong> of Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru,<strong>The</strong> Nati<strong>on</strong>al Library of WalesIn a prominent locati<strong>on</strong> near <strong>the</strong>ruins of <strong>the</strong> medieval abbey ofValle Crucis, near Llangollen innorth-east Wales, <strong>on</strong> a moundof unknown date, stands a fragmentof a 9 th -century AD cross-shaft (Figs1, 3). This unique m<strong>on</strong>ument is <strong>on</strong>eof <strong>the</strong> most important <strong>sites</strong> for <strong>the</strong> historyof early medieval Wales and <strong>the</strong>Borders, for two reas<strong>on</strong>s. First, it is arare example of part of an early medievalst<strong>on</strong>e sculpture that is still situatedat, or very close to, its original placeof erecti<strong>on</strong>. Sec<strong>on</strong>d, although nowbarely visible, until <strong>the</strong> 17 th century itbore a l<strong>on</strong>g Latin inscripti<strong>on</strong> explainingwho erected it and why. Althoughfragmentary, <strong>the</strong> Latin inscripti<strong>on</strong> wastranscribed accurately by <strong>the</strong> famousWelsh antiquary Edward Lhwyd(1660–1709). It says that <strong>the</strong> cross waserected by C<strong>on</strong>cenn (o<strong>the</strong>rwise knownas Cyngen), <strong>the</strong> last king of early medievalPowys, who died in AD 854. <strong>The</strong>2text also states that <strong>the</strong> cross commemoratesC<strong>on</strong>cenn’s great grandfa<strong>the</strong>rEliseg, who it claims had driven out <strong>the</strong>English from <strong>the</strong> area ‘with his sword byfire’. Eliseg may have been a c<strong>on</strong>temporaryof <strong>the</strong> great Mercian king Offa (r.757–796) whose famous linear earthwork(Offa’s Dyke) runs <strong>on</strong>ly 9.5km to<strong>the</strong> east of <strong>the</strong> Pillar. Hostile relati<strong>on</strong>sbetween Powys and Mercia may haveprompted <strong>the</strong> Dyke’s c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>. <strong>The</strong>inscripti<strong>on</strong> also traces back <strong>the</strong> originsof <strong>the</strong> kingdom to Eliseg’s ancestors,who (according to <strong>the</strong> text) included<strong>the</strong> Roman emperor Magnus Maximus(r. c. AD 383–388) and <strong>the</strong> <strong>legend</strong>aryDark Age ruler Vortigern. C<strong>on</strong>cennwas <strong>the</strong>refore not <strong>on</strong>ly associating hiskingship with <strong>the</strong> military successes ofhis great-grandfa<strong>the</strong>r; through this tex<strong>the</strong> was portraying himself as heir to <strong>the</strong>kingdom of Britain (including all thoselands lost to <strong>the</strong> English) and to <strong>the</strong>imperial purple.<strong>The</strong> cross had fallen in <strong>the</strong> 17 th century,although it was re-erected in 1779by a local squire, who also dug <strong>the</strong>mound and reputedly found a st<strong>on</strong>ecist with a skelet<strong>on</strong> interred with a silvercoin (Fig 2). However, <strong>the</strong> report isunreliable and <strong>the</strong> b<strong>on</strong>es and artefactshave not survived, and <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>umenthas subsequently received no fur<strong>the</strong>rarchaeological research. Today, <strong>the</strong>site is a tourist attracti<strong>on</strong>, yet little isknown about <strong>the</strong> archaeological c<strong>on</strong>textof <strong>the</strong> Latin inscripti<strong>on</strong>. It has beenspeculated that <strong>the</strong> mound was a prehistoricm<strong>on</strong>ument, or perhaps even<strong>the</strong> tomb of Eliseg himself.Recently, as part of her research into<strong>the</strong> early medieval inscribed st<strong>on</strong>esand st<strong>on</strong>e sculpture from Wales, ProfNancy Edwards has reinterpreted<strong>the</strong> text and <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>ument as politicalpropaganda by <strong>the</strong> kings of Powys,at a time when <strong>the</strong>ir rule was underthreat by <strong>the</strong>ir Anglo-Sax<strong>on</strong> and Welshneighbours. She even suggests that <strong>the</strong>text, reading like a legal document andusing an antiquated script and phraseology,and with its focus <strong>on</strong> <strong>the</strong> myths,<strong>legend</strong>s and genealogy of Powys’ ruler,was c<strong>on</strong>cerned with legitimising landclaimsand territory. She suggests that<strong>the</strong> cross and mound may have been<strong>the</strong> focal point of an early medievalassembly site, and, drawing <strong>on</strong> analogieswith Scottish and Irish <strong>sites</strong>, tentativelyspeculates that it could havebeen <strong>the</strong> royal inaugurati<strong>on</strong> site for <strong>the</strong>kings of Powys. If so, <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>umentnever fulfilled this role, owing to <strong>the</strong>death of C<strong>on</strong>cenn, <strong>the</strong> rise to powerof <strong>the</strong> rival kingdom of Gwynedd, andFig 1. <strong>The</strong> Pillar ofEliseg and its mound,viewed from <strong>the</strong> west.Fig 2. <strong>The</strong> Pillar ofElisig near ValleCrucis, by ThomasRowlands<strong>on</strong>, penciland watercolour <strong>on</strong>paper, c. 1797. This is<strong>the</strong> earliest depicti<strong>on</strong>of <strong>the</strong> m<strong>on</strong>ument andcame so<strong>on</strong> after<strong>the</strong> Pillar had beenre-erected.334