Moments of Discovery - UT Southwestern

Moments of Discovery - UT Southwestern

Moments of Discovery - UT Southwestern

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Moments</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Discovery</strong>A Journey to the 2011 Nobel Prize

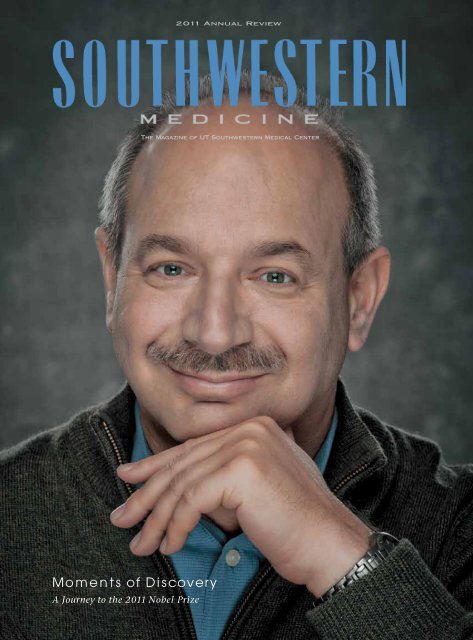

C O N T E N T SLUNG CANCER IN THE CROSSHAIRS 2Physicians and researchers are taking aim on several fronts to target America’s biggest cancer killer.THE NATION’S NO. 1 KILLER SENDS SILENT SIGNALS 10Cardiologists are uncovering new risk factors and predictors that can indicate heart disease before it strikes.BRAVE NEW WORLD: HIGH TECH MEDICINE 18Merging medicine and technology can advance scientific discovery and enhance patient care.MOMENTS OF DISCOVERY 26Dr. Bruce A. Beutler describes the long journey that led not only to pr<strong>of</strong>ound discoveries<strong>of</strong> how the immune system works, but also a Nobel Prize.THE HOSPITAL OF THE F<strong>UT</strong>URE 34Designed around the needs <strong>of</strong> patients and their families, the new <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> University Hospitalwill be as innovative as the scientific discoveries for which the medical center is known.CAN FOODBORNE ILLNESSES BE STOPPED? 42Researchers are at the forefront <strong>of</strong> understanding and preventing the spread <strong>of</strong> dangerous bacteria in food.VOLUME 21 / NUMBER 1 VOLUME / FEBRUARY 21 / 2012 NUMBER 1 / FEBRUARY 2012<strong>Southwestern</strong> Medicine is <strong>Southwestern</strong> a publication Medicine <strong>of</strong> the University is a publication <strong>of</strong> the UniversityNews Bureau at The University News Bureau <strong>of</strong> Texas at The <strong>Southwestern</strong> University <strong>of</strong> Texas <strong>Southwestern</strong>Medical Center, a component Medical <strong>of</strong> Center, The University a component <strong>of</strong> <strong>of</strong> The University <strong>of</strong>Texas System. Copyright, Texas 2012, System. <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Copyright, 2012, Medical <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> MedicalCenter. For permission Center. to quote For permission reprint any to material quote or reprint any materialwritten herein, for permission written to herein, reproduce for permission art, or to to reproduce art, or torequest additional copies, request please additional contact the copies, University please contact the UniversityNews Bureau, 5323 Harry News Hines Bureau, Blvd., 5323 Dallas, Harry Texas Hines Blvd., Dallas, Texas75390-9060. <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> 75390-9060. is an equal <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> opportunity is an equal opportunityinstitution.institution.WHAT IT TAKES TO BECOME A WORLD-CLASS PHYSICIAN 50<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> prepares the next generation <strong>of</strong> physicians to process and retain vast amounts <strong>of</strong> medicalknowledge, which, by 2020, is expected to double approximately every four months.THE CLINICAL FRONTIER 60CLINIC TREATS SLEEP AND BREATHING DISORDERS 60TARGETED THERAPY FOR ADVANCED GYNECOLOGIC CANCERS 61PRESIDENTDANIEL K. PODOLSKY, PRESIDENT M.D. DANIEL K. PODOLSKY, M.D.MAKING HEADWAY ON HEADACHES 62COMMUNICATIONS, VICE PRESIDENT MARKETING FOR COMMUNICATIONS, AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS MARKETING TIM DOKE AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS TIM DOKEDIRECTOR OF UNIVERSITY NEWS DIRECTOR BUREAUOF MICHAEL UNIVERSITY BERMAN NEWS BUREAU MICHAEL BERMANASSISTANT EDITORSR<strong>UT</strong>H EYRE ASSISTANT EDITORS R<strong>UT</strong>H EYREDONNA STEPH HANSARDONNA STEPH HANSARDROBIN LOVEMAN ROBIN LOVEMANPATRICK WASCOVICH PATRICK WASCOVICH2011 ANNUAL REVIEW 65highlights <strong>of</strong> the year 66financial statement 76gift report 79WRITERS DEBBIE BOLLESWRITERSDEBBIE BOLLESJEFF CARLTON JEFF CARLTONLAKISHA LADSON LAKISHA LADSONALEX LYDAALEX LYDARUSSELL RIAN RUSSELL RIANROBIN RUSSELL ROBIN RUSSELLERIN PRATHER STAFFORDERIN PRATHER STAFFORDPHOTOGRAPHERSBRIAN COATS PHOTOGRAPHERSDAVID GRESHAMBRIAN COATSDAVID GRESHAMDIRECTOR OF CREATIVE SERVICES DIRECTOR SHAYNE OF CREATIVE WASHBURN SERVICESSHAYNE WASHBURNDESIGNERS KEVIN BAILEYDESIGNERSJAY CALDWELLANGELA CHARLTONSHANE DENNEHEYYOLANDA FUENTESWALTER HORTONKEVIN BAILEYJAY CALDWELLANGELA CHARLTONSHANE DENNEHEYYOLANDA FUENTESWALTER HORTONPRODUCTIONCHERYL SUDOL PRODUCTIONKATHY WATSONCHERYL SUDOLKATHY WATSONOn the cover: 2011 Nobel On the Laureate cover: Dr. 2011 Bruce Nobel A. Beutler Laureate Dr. Bruce A. BeutlerArticles from <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medicine and other news and information from <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> are available online at www.utsouthwestern.edu.

Lung Cancer in theCrosshairsTargeting America's Biggest Cancer KillerAfter undergoing a routine hernia operation, Anita Vasquez returned to her Fort Worthhome only to come down with a fever and cough. A simple chest X-ray revealed a nightmarishscenario: Mrs. Vasquez learned she was facing a tumor that threatened to burstout <strong>of</strong> her lung and invade other organs. Never having touched a cigarette, she and herhusband were shocked. “The doctor <strong>of</strong>fered to show me a picture <strong>of</strong> my left lung on thecomputer,” the 68-year-old former unit secretary at Harris Methodist Hospital recalledrecently. “And there it was: a round shadow.” The couple immediately started pollingfriends and family about where to go for treatment. A dietitian at work quietly saidshe should go to Dallas, specifically to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical Center’s Harold C.Simmons Cancer Center, which has an excellent lung cancer program. She prayed.But it wasn’t until standing in a checkout line the next day that she heard anothercustomer speaking highly <strong>of</strong> the Simmons Cancer Center.B Y A L E X L Y D A1 2

“It was more than a coincidence that I wasin line with this man,” Mrs. Vasquez said onerecent afternoon. “That’s when God intervenedand made my decision for me.”She would go to Dallas.Patients are bringing their cancer fight tothe Simmons Cancer Center daily. For somewho are emotionally prepared and intellectuallycurious enough to see cancer up close, thecenter allows patients to get smart about thedisease, in ways that other cancer centerswithout equally strong research underpinningscannot. In order to effectively fight an enemy,one must see it to treat it. This is where doctorsand scientists at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> are makingheadway every day.Seeing the enemyDr. Adi Gazdar and other Simmons CancerCenter specialists believe that seeing the canceron a molecular level is important, and not justfor the diagnostician. Dr. Gazdar, pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> pathology, holds the W. Ray WallaceDistinguished Chair in Molecular OncologyResearch at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>.To most patients, the cancers growing inthe flasks and petri dishes that fill Dr. Gazdar’slaboratory will remain an invisible enemy.Yet the clumps <strong>of</strong> non-small cell lung cancers,giant-cell carcinomas and tumors are visibleto the naked eye. Hold the flask up to anyfluorescent light and they make cancer very realand very alive.Cynthia Gonzalez was in her early 50swhen diagnosed with advanced lung cancer,only after developing a persistent cough thatwas first thought by doctors to be bronchitisor pneumonia. After multiple visits at anotherfacility and an ineffective course <strong>of</strong> antibiotics,doctors discovered the truth. A biopsy done at<strong>UT</strong> MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houstonrevealed Stage 4 lung cancer.“By this time I had zero trust in doctors,”Mrs. Gonzalez said. “They did give me a videoand a brochure and that told me what to expect,but I didn’t feel like I was getting the personalattention that I needed.”After asking some friends in the medicalcommunity where she could go for thetrust and individualized treatment she wasseeking, she contacted Dr. Joan Schiller, chief<strong>of</strong> the Hematology/Oncology Division at<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> and holder <strong>of</strong> the AndreaL. Simmons Distinguished Chair in CancerResearch.Mrs. Gonzalez remembers the day vividly.It was Dec. 27, 2010.“Dr. Schiller called me back that day fromher family vacation in Colorado,” Mrs. Gonzalezsaid. “My experience is that most doctors careabout their own time, so I was so surprised andencouraged that she would be so selfless.”Mrs. Gonzalez’s experience at the SimmonsCancer Center is typical <strong>of</strong> many patients.The process usually starts with lab tests. Tumortissue is analyzed every way possible underthe microscope and through a series <strong>of</strong> highlysophisticated molecular assays. Then, usingthe state-<strong>of</strong>-the-art information collected ata cellular level, cancer specialists select thebest therapy for that patient – what types <strong>of</strong>chemotherapy drugs and, if indicated, the mosteffective uses <strong>of</strong> radiation, what doctors call a“combined modality” treatment.Understanding the enemyIn scientific terms, cancer is a disease <strong>of</strong>pathological hyperplasia – uncontrolled growth<strong>of</strong> the body’s own cells. And some patients’interest in the disease – ultimately a fightagainst their own body – can be comprehensivein itself: Doctors say the informed patient triesto absorb as much information as possibleabout the latest clinical advances and themost cutting-edge research in cancer biology,applying what they learn to fight their cancerin ways that make sense for them.At the Simmons Cancer Center, cancerpatients can visit the labs to understand moreabout the enemy, said Dr. John Minna, director<strong>of</strong> the Nancy B. and Jake L. Hamon Centerfor Therapeutic Oncology Research and theW.A. “Tex” and Deborah Moncrief Jr. Centerfor Cancer Genetics. A cancer patient beingtreated can not only see cancer cells, but has thechance to watch them swarm and multiply inDr. Gazdar’s lab.“We do have patients who want to considerthe totality <strong>of</strong> their disease and attack it fromall angles,” said Dr. Minna, a pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>internal medicine, who holds the Sarah M. andCharles E. Seay Distinguished Chair in CancerResearch and the Max L. Thomas DistinguishedChair in Molecular Pulmonary Oncology. “Tothese patients, visualizing the ‘enemy’ andunderstanding it on a fundamental level canincrease their interest in shaping a treatmentthat ultimately improves the outcome.”Call it a personalized, team-based approachthat puts the patient on par with theoncologists, researchers, nurses and supportivecare personnel who are all dedicated to the fight.An Invisible enemyThe Simmons Cancer Center is the onlycancer center in North Texas to have received adesignation from the National Cancer Institute(NCI). While the center is on the cutting edge<strong>of</strong> detecting and imaging cancer, the problem<strong>of</strong> adequately seeing cancer on a cellular leveldates to when leukemia was known simply as“white blood.”Until the middle <strong>of</strong> the last century,observing the behavior <strong>of</strong> cancer cells didnot significantly advance until the renownedpediatric pathologist Dr. Sidney Farber firsttrained his microscope in Boston on theblood <strong>of</strong> very sick children suffering from anexplosion in their white blood cell counts. Theblood looked milky under the microscope; hewas seeing leukemia. It was 1947, around thetime when <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> as it is knownnow was just getting <strong>of</strong>f the ground, thanks tothe inimitable leadership <strong>of</strong> Drs. Edward Cary,Donald Seldin and others.Fast-forward to 2012.The landscape for detecting, studying andtreating cancer has changed radically. Many <strong>of</strong>the advances are on full display at the SimmonsCancer Center, particularly in the fight againstlung cancer, the nation’s top cancer killer. Morethan 173,000 new cases <strong>of</strong> lung cancer areDr. Adi Gazdar scrutinizes a flask forclumps <strong>of</strong> cancer cells visible withthe naked eye. Dr. Gazdar’s laboratoryhas cataloged and analyzedover 2,200 human cancer specimens,with an emphasis on lung cancerand lymphomas.diagnosed each year in the U.S., accounting for13 percent <strong>of</strong> new cancer cases, according to theAmerican Cancer Society. That is equal to theentire city <strong>of</strong> Dayton, Ohio, getting a diagnosis– when 88 percent <strong>of</strong> the people living there donot even smoke.Peter Jennings, the late and pioneering ABCNews anchor, smoked. While he passed awayquietly in the palliative care unit <strong>of</strong> MemorialSloan-Kettering Cancer Center in 2005, noamount <strong>of</strong> money or expert care could save him.A number <strong>of</strong> other celebrities and notablepersonalities have succumbed to lung cancer,smokers and non-smokers alike: Dana Reeve,the wife <strong>of</strong> actor Christopher Reeve; actorsSteve McQueen and Vincent Price; and singerLou Rawls.Dr. Gazdar is among a select group <strong>of</strong> cancerscientists searching for lung cancer biomarkersin people who have never smoked. In 2009,the National Cancer Institute’s Early DetectionResearch Network and the Canary Foundation,a nonpr<strong>of</strong>it organization that funds research inearly cancer detection, provided initial funding<strong>of</strong> $1 million to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> for thefirst year <strong>of</strong> a biomarker project that is beingconducted at five sites across the country.The clinical problem is that lung cancer<strong>of</strong>ten cannot be detected until its advancedstages, and the average life expectancy <strong>of</strong>4SO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE 5

Lung cancer biology: getting down to the DNAsomeone receiving a lung cancer diagnosis isless than five years. It is a swift and stealthykiller, <strong>of</strong>ten with no early symptoms. Andunlike mammography for breast cancer,colonoscopy for colon cancer or PSA tests forprostate cancer, there is no routine screeningtest for early lung cancer.Mrs. Vasquez’s physician, Dr. Schiller, istrying to fix that.“The need for a comprehensive andprescribed way <strong>of</strong> detecting lung cancer earlyis crucial,” Dr. Schiller, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> internalmedicine said. “Older ways <strong>of</strong> screening justaren’t effective at catching lung cancer beforeit’s too late.”A study published Oct. 26, 2011, in theJournal <strong>of</strong> the American Medical Association foundthat routine chest X-rays do not reduce therisk <strong>of</strong> death from lung cancer in smokers orformer smokers. The NCI study involved morethan 150,000 older Americans. The finding wasstartling: Those who had annual chest X-rayscreenings over four years were just as likely todie <strong>of</strong> lung cancer as study volunteers who didnot get screened. In other words, chest X-raysare not useful in preventing lung cancer orseeing it early enough.Dr. Joan Schiller andher colleagues haveestablished a chestCT scanning programat <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>aimed at current andprior smokers ages 55years and older. Thescreening helps identifycancers beforethey become a seriousproblem.The findings suggest the best strategy fordiscovering lung tumors in an early, moretreatable stage is screening with computedtomography (CT) scans, which were shownin a separate recent study to lower the deathrate by 20 percent.To detect lung cancer earlier, the team ledby Dr. Schiller, Dr. Kemp Kernstine, Chair <strong>of</strong> theDivision <strong>of</strong> Thoracic Surgery and holder <strong>of</strong>Robert Tucker Hayes Foundation DistinguishedChair in Cardiothoracic Surgery, and Dr. HakChoy, chair <strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> RadiationOncology and holder <strong>of</strong> the Nancy B. and JakeL. Hamon Distinguished Chair in TherapeuticOncology Research, have started a chest CTscreening program that allows qualified peoplewho are at risk to elect to have a spiral CT scandone. Team members Dr. Muhanned Abu-Hijleh, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> internal medicine,and Dr. Cecelia Brewington, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>radiology, designed the program, which also hasa research component to identify other meansfor detecting cancer earlier, in the breath, saliva,mouth cells and blood.While preventative CT scans are not yetcovered by insurance, they are recommendedfor current and prior smokers ages 55 and older.The test consists <strong>of</strong> one low-dose CT scan peryear for three years. Lung cancer is not the onlypotentially life-threatening disease the scan isable to detect. While scanning for lung cancer,CT scans also can reveal the presence <strong>of</strong> otherdiseases, such as heart disease, emphysema andother cancers that may originate in or havespread to the chest.“There are some caveats, but this representsan opportunity to catch lung cancer and otherdiseases very early, well before they become aserious problem,” Dr. Schiller said.Nearly a quarter <strong>of</strong> the patients will be foundto have suspicious findings, most <strong>of</strong> them notcancer. While patients are exposed to low doses<strong>of</strong> radiation, each scan’s radiation dose is lessthan a fifth <strong>of</strong> the dose <strong>of</strong> regular CT scans.The key is to see the cancer while there isstill time to do something about it, Dr. Schillersaid. In Mrs. Vasquez’s case, there was still timebut the window was rapidly closing.Attacking the enemy<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> leads a SPORE (SpecializedPrograms <strong>of</strong> Research Excellence) grant thatis shared with MD Anderson. Such grants arethe cornerstone <strong>of</strong> the NCI’s effort to promotecollaborative, interdisciplinary cancer researchand treatment. These grants involve both basicscientists and clinicians working on new waysRadiation therapy is a powerful tool in treating cancer, but asmany patients can attest, being treated with radiation is notwithout side effects.“Radiation is a double-edged sword that affects bothtumors and healthy tissues,” says Dr. Hak Choy, chairman<strong>of</strong> radiation oncology and holder <strong>of</strong> the Nancy B. and Jake L.Hamon Distinguished Chair in Therapeutic Oncology Research.“Therefore, it is imperative that we administer radiation ascarefully and as precisely as possible. If we didn’t have to worryabout the side effects <strong>of</strong> radiation, we could curealmost any cancer.”In order to deliver the most preciseand least harmful doses <strong>of</strong> radiation, theuniversity’s Department <strong>of</strong> Radiation Oncologyhas invested in leading-edge devices capable<strong>of</strong> treating cancers anywhere in the body (see“Brave New World: High Tech Medicine” onp. 18), while ensuring minimal damageto surrounding healthy tissue. The resultis fewer side effects for treatments that 10years ago would have been associated withextreme fatigue, skin changes, hair loss, mouththe division <strong>of</strong> molecular radiation biology and holder <strong>of</strong> theDavid A. Pistenmaa, M.D., Ph.D., Distinguished Pr<strong>of</strong>essorshipin Radiation Oncology, leads the five-year project to identify themolecular events that underlie the choice between pathwaysfor repairing DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs).Although normal human cells are exposed to multiple DNAlesions every day, the type <strong>of</strong> damage inflicted by radiation –double-strand breaks – is the most harmful. In this instance,both pairs <strong>of</strong> genes are broken, increasing the likelihoodthat the cell will either be unable torepair itself or that the genetic code willpass on damaged information during cellreplication.Human cells have two distinct methods torepair DSBs, and one <strong>of</strong> the major unresolvedquestions in the field <strong>of</strong> DNA research is whatmechanism determines the choice betweenthe two. The importance <strong>of</strong> these repairpathways is supported by the observationthat an increase in cancer incidence isassociated with impaired DSB repair.“The increased level <strong>of</strong> DNA damage inproblems and more.But these are only the visible effects <strong>of</strong>radiation. Radiation therapy works bydeliberately damaging the cellular DNA, whichultimately induces tumor cell death. WhileDr. David Chen and his team arestudying how DNA is repaired by thebody, with an eye toward mitigatingthe side effects <strong>of</strong> radiation and moreeffectively targeting tumors.cancer cells and the use <strong>of</strong> DNA-damagingagents in cancer treatment underlie theimportance <strong>of</strong> DSB repair in cancerbiology,” Dr. Chen says. “Basic mechanisticinsights into DSB repair mechanisms andDNA damage to the tumor is desirable, healthy tissue may alsobe subjected to DNA damage, which may result in side effectsranging from temporary irritation, to scarring, necrosis and even (inthe long term) giving rise to new cancers.Understanding how tumor and healthy tissue repair DNAdamage is an area that may significantly impact the future ability<strong>of</strong> physicians to mitigate such side effects while more effectivelytargeting tumors.In March, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute <strong>of</strong> Texas(CPRIT) awarded $6.4 million to a multi-institutional groupled by a <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researcher who has made historiccontributions to the field <strong>of</strong> DNA repair. Dr. David Chen, chief <strong>of</strong>the regulation <strong>of</strong> pathway choice for the repair <strong>of</strong> DSBs arelikely to translate into new opportunities for cancer treatment.”With the CPRIT money awarded to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>, Dr.Benjamin Chen, assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> radiation oncologytogether with Dr. David Chen, will investigate whether activityat a specific amino acid cluster (the T2609 cluster) plays a rolein determining pathway choice. Another university researcher,Dr. Hongtao Yu, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> pharmacology, a Howard HughesMedical Institute investigator and a Michael L. RosenbergScholar in Medical Research, will study regulation <strong>of</strong> the DNArepair pathway choice by two other protein complexes that areinvolved in cell replication. Their individual projects are fundedat $1.3 million each.6continued page 86 SO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE 7

Dr. John Minnabelieves that<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>’sedge in personalizedcare comesfrom tailoringtreatment optionsto a molecularanalysis <strong>of</strong> eachpatient’s tumor.to prevent, detect and diagnose cancers, as wellas to treat them. The Simmons Cancer Centeris now headlong into an effort to identify themolecular hallmarks <strong>of</strong> lung cancer, with an eyetoward developing better drugs.The goal is to further personalize thetherapeutic options available to individualcancer patients who may be facing commoncancers with a unique set <strong>of</strong> characteristics.When combined with state-<strong>of</strong>-the-art methodsto test compounds against hundreds <strong>of</strong> differentcombinations <strong>of</strong> genetic mutations, a curefor certain cancers, such as lung, may bewithin reach.Dr. Michael White, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> cell biology,who is focused on uncovering the mechanisms bywhich cells can adversely react to their ownenvironment, said this represents a departurefrom the “guess-and-test” approach that hascharacterized a lot <strong>of</strong> the cancer biology thateventually moved into the clinical realm.Rather than “throwing spaghetti at the wallsto see what sticks,” Dr. White, who holds theSherry Wigley Crow Cancer Research EndowedChair, in Honor <strong>of</strong> Robert Lewis Kirby, M.D.and the Grant A. Dove Chair for Research inOncology, said <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers aswell as colleagues elsewhere are tapping intoan array <strong>of</strong> genetics assays, cell lines and tumormodels that have exclusively been built at<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> over the years.Collaborating with leaders in biochemistryand pharmacology, Dr. White and hiscolleagues, Dr. Michael Roth, the interimdean <strong>of</strong> <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Graduate School<strong>of</strong> Biomedical Sciences and vice chairman <strong>of</strong>biochemistry who holds the Diane and HalBrierley Distinguished Chair in BiomedicalResearch; Dr. Bruce Posner, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> biochemistry; and Dr. Minna are supportedby large grants from the National CancerInstitute and the Cancer Preventionand Research Institute <strong>of</strong> Texas (CPRIT).CPRIT has allowed these researchers tocross-test thousands <strong>of</strong> different compoundsand biological agents against different cancersranging from the ordinary to the exotic.As Dr. White points out, “combining ourhigh-throughput screening results with all <strong>of</strong>the molecular information we have assembledon lung cancers allows us to determine manynew therapeutic targets, which will change howwe approach lung cancer. This will also allow usto ‘personalize’ the use <strong>of</strong> these new therapiesby finding the right molecular match for eachpatient’s tumor – something we refer to as‘enrollment biomarkers.’”Researchers here and elsewhere believe thatthis is the most promising way in which socalled“translational” research is poised to crackthe cancer code and “catch up” with biology.“The doctors at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> used acombination <strong>of</strong> drugs that was specificallytailored for my particular cancer,” Mrs.Gonzalez said. “I think the drugs that my otherdoctors would have put me on would not havebeen as effective.”Outwitting the enemySince feelings can be hard to see, theemotional component <strong>of</strong> a positive diagnosisis <strong>of</strong>ten the most difficult aspect <strong>of</strong> cancer t<strong>of</strong>ully appreciate. The marshaling <strong>of</strong> spiritualresources needed to take on a war againstcancer is a battle with which Mrs. Vasquezand Mrs. Gonzalez are intimately familiar.“Patients <strong>of</strong>ten are looking for things thatgive them hope and a sense <strong>of</strong> control,” said Dr.Simon Craddock Lee, a medical anthropologistwho focuses on cancer disparities andpatient decision-making, and a member <strong>of</strong>the Population Sciences and Cancer ControlProgram within the Simmons Cancer Center.“Oncologists do their best to communicatethe options for patients while supportingthem in their right to decide the best course<strong>of</strong> treatment. In comprehensive cancer care, acadre <strong>of</strong> experts works with oncologists to try toaddress all the different needs <strong>of</strong> a patient.”To this end, the Simmons Cancer Centerhas a growing, multifaceted support programdesigned to work in concert with oncologistsand their patients from the very moment <strong>of</strong>diagnosis.“This is where our program is distinct fromother cancer care support programs,” said Dr.Jeff Kendall, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> psychiatryand the clinical leader <strong>of</strong> the supportive servicesprogram at the center. “Rather than beingmentioned as an afterthought to treatment, webring support services to the fore right away, asa seamless complement to treating the wholepatient, perhaps before he or she even realizes itis necessary.”The new direction in cancer care todayis treating the “whole patient,” Dr. Kendallnotes. This treatment model means recognizingthe importance <strong>of</strong> the emotional, social andspiritual changes that <strong>of</strong>ten accompany adevastating diagnosis <strong>of</strong> cancer and the effectthe illness can have on an entire family.However, recognition is not enough. It is justas important to intervene once certain needshave been identified, he said.Efforts by Dr. Kendall and his staff havesought to raise awareness and identifyemotional issues in cancer care through“psychosocial distress screening” interviewswith patients. In a sense, Dr. Kendall isattempting to see any signs <strong>of</strong> distress in hispatients while there is time to intervene.The stress associated with a cancer diagnosishas been shown to cause considerablepsychological morbidity, with 25 percent to50 percent <strong>of</strong> all cancer patients indicatingsignificant levels <strong>of</strong> distress.“While our advances in cancer research andtreatment continue at a steady pace, patientsnow face more complex treatment decisionsand follow-up options,” said Dr. James K.V.Willson, director <strong>of</strong> the Simmons CancerCenter and holder <strong>of</strong> the Lisa K. SimmonsThe Harold C. Simmons CancerCenter is one <strong>of</strong> only seven in thenation to obtain a prestigiousSpecialized Program <strong>of</strong> ResearchExcellence (SPORE) grant from theNational Cancer Institute.Distinguished Chair in ComprehensiveOncology. “<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> has a caring staff<strong>of</strong> medical pr<strong>of</strong>essionals who are committedto enhancing patients’ quality <strong>of</strong> life, as wellas meeting the needs <strong>of</strong> patients’ families. Akey component <strong>of</strong> our mandate as an NCIdesignatedcancer facility is that we meet allaspects <strong>of</strong> a patient’s total care. Support servicesare a key element in that.”After undergoing a lobectomy to remove thepart <strong>of</strong> her lung that was cancerous, followed bya chemotherapy and radiation regimen at theSimmons Cancer Center, Mrs. Vasquez still seesher doctors regularly.“When I was diagnosed and decided tostart going to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>, people said,‘Why do you keep going there? It’s too far!’” sherecently recounted. “The fact that I bonded sowell with Dr. Schiller and that they still checkon me is why. Of course, having cancer hasmade me more religious. I thank God for thecare I get there.”8SO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE 9

BY LAKISHA LADSONDespite the notion that heart disease occurs withoutwarning, <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical Center cardiologistsare discovering that the nation’s No. 1 killer doesindeed send silent signals <strong>of</strong> impending cardiovasculardisease decades before seemingly healthy people realizetheir lives are under assault.The murderer’s many weapons, which includeatherosclerosis, heart attack, stroke and congestiveheart failure, may be noted through silent cues fromblood-based tests, advanced imaging scans and possiblyeven a person’s capacity to exercise.“We’re discovering risk factors that are clear andcompletely silent,” said Dr. Darren McGuire, associatepr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> internal medicine at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>.“People feel fine even when the classic risk factors forcardiac disease are diagnosed, such as increasedblood pressure, abnormal cholesterol or diabetes.Uncovering these silent signals that become abnormallong before disease is evident gives us opportunitiesto create therapies to intervene before heart diseasedisables or ends a person’s life.”The Nation’sNo.1 KillerSends SilentSignalsSO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE 11

Drs. Jarett Berry,Sachin Gupta<strong>of</strong> cardiology, said the multiyear investigationmirrors the populations <strong>of</strong> most U.S. cities.“One <strong>of</strong> the many strengths <strong>of</strong> the Dallas HeartStudy is that important findings can be used atthe community level.”While the study’s findings will be a source <strong>of</strong>scientific information for many years to come,<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> cardiologists also are exploringother avenues to reduce health risks. One <strong>of</strong> themore intriguing is the interplay between exerciseand heart disease.Most people have heard and accept that ifthey exercise they might be able to stave <strong>of</strong>fdiabetes, obesity and heart disease for a while.Moving beyond these general benefits, <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>researchers, in conjunction with theCooper Institute <strong>of</strong> Dallas, have found that thelevel and intensity <strong>of</strong> exercise a person can doon a treadmill may actually tell how likely theyare to die decades later from heart disease.Researchers analyzed the heart disease risk <strong>of</strong>45-, 55- and 65-year-old men based on theirfitness level and traditional risk factors – age,systolic blood pressure, diabetes, total cholesteroland smoking habits – and found that low levels <strong>of</strong>midlife fitness, measured by how fast and longsomeone could exercise, are associated withmarked differences in lifetime risk for cardiovasculardisease. Higher fitness levels lowered thelifetime risk <strong>of</strong> heart disease even in people withother risk factors.Researchers also found the same treadmilltest predicts how likely a person is to die <strong>of</strong>heart disease or stroke more accurately thanassessing the risk using only traditionalprediction tools.For this work, the American HeartAssociation (AHA) gave the Elizabeth Barrett-Connor Research Award in Epidemiology to Dr.Sachin Gupta, postdoctoral trainee in internalmedicine. The award is one <strong>of</strong> the AHA’s mostprestigious awards, recognizing excellence inresearch by an early-career investigator.“Our study shows that fitness level measuredin middle age can significantly improverisk prediction algorithms and help to identifyindividuals at risk for cardiovascular deathboth in the short term and in the long term,”Dr. Gupta said.This trial has great potential for everyone butspecial significance for youth and women, whohave fewer prediction tools to assess long-termcardiovascular risk.“Nearly all women in the U.S. less than 50years <strong>of</strong> age are at low risk for heart disease,”said Dr. Berry, a Dedman Family Scholar inClinical Care. “As women get older, however,their risk increases dramatically. In our study,we found that low levels <strong>of</strong> fitness were particularlyhelpful in identifying women at riskfor heart disease over the long term.”<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>, Cooper partnerThese studies were done in conjunctionwith the Cooper Institute, which has compileddata on exercise and fitness from healthyvolunteers for 40 years. <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> hasa partnership with the institute, the preventivemedicine research and educational nonpr<strong>of</strong>itlocated at the Cooper Aerobics Center, todevelop a joint scientific medical researchprogram aimed at improving health andpreventing a wide range <strong>of</strong> chronic diseases.The hallmark study from the institute – theCooper Center Longitudinal Study – includesdetailed information from more than 250,000clinic visits that has been collected since Dr.Kenneth Cooper founded the institute andclinic in 1970.Large population studies like Dallas Heartand Cooper Center Longitudinal allowresearchers to examine not only factorscontributing to disease but, more importantly,factors that promote cardiovascular health.“We’re as interested in the protective factorsas the harmful ones,” Dr. de Lemos said. “Forexample, we are going to learn a huge amountfrom people who live their whole lives overweightor obese yet never develop cardiovascularcomplications – we’ve found a lot <strong>of</strong> peoplelike that in our study.”Doctors now are bringing these tests forsilent signals <strong>of</strong> heart disease to fruition and seeinghow they work in the real world. For example,<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers have founddifferences in blood levels <strong>of</strong> C-reactive protein(CRP) according to race or sex. CRP is a marker<strong>of</strong> inflammation and has been heavily toutedas a test to improve prediction <strong>of</strong> heart attacks.“White woman have higher levels <strong>of</strong> CRPthan both black and white men,” Dr. Kherasaid. “Since white women have lower rates <strong>of</strong>cardiovascular disease, this study raises somequestion about how to best use CRP in thereal world.”Dr. Khera said some tests may call fordifferent thresholds between men and womento determine more accurately the risk <strong>of</strong> heartdisease, and that overreliance on CRP for riskassessment in African-American patients mayoverestimate risk for cardiac and vascularevents, since more than one-half <strong>of</strong> thesepatients had elevated levels.Some <strong>of</strong> these signals are stronger for certaintypes <strong>of</strong> heart disease: calcium scanning forincreased risk <strong>of</strong> heart attack, fitness level andcardiac troponin T detection for heart failure.“We believe that combining imaging testswith protein tests is going to help identifypeople who feel perfectly well but who willhave notably increased risk <strong>of</strong> heart complicationsdown the line,” Dr. de Lemos said.The findings about fitness are now availableand can be accessed at www.lifetimerisk.org.On this website, an individual can help determinehis or her lifetime risk for cardiovasculardisease by entering their age, sex, fitness leveland other risk information.“Fitness has the potential to have a largeimpact because everybody can do it,” Dr. Kherasaid. “Fitness is relatively easy to measure,costs very little to improve, and people wantalternatives to medicines.”Cardio health balance delicateEven though heart disease is the leadingcause <strong>of</strong> death in the U.S., its incidence isdeclining in large segments <strong>of</strong> the generalpopulation due to decreases in cigarettesmoking and improved cholesterol levels.The nation’s aging population and its risingobesity epidemic, however, run counter tohealth-conscious gains.“Every adult in America is potentially atrisk for heart disease in some form or fashion.Once you have a heart attack, the risk foradditional heart problems down the road ismuch higher,” said Dr. Khera, co-chair <strong>of</strong> theAmerican Heart Association’s state advocacycommittee. “We’re proud that we’re doing thework on the front end to make sure the horsenever leaves the barn.”Increased screening is one solution, buteven then, approved implementation will bechallenging.“Without clear guidance and acceptedalgorithms for test interpretation, there ispotential for both inappropriate under-treatmentand over-treatment <strong>of</strong> individuals basedon test results,” Dr. Khera said. “Still, we thinkcritically and carefully about how to helpidentify those people who seem healthy, butare at increased risk <strong>of</strong> heart disease later on.”As long as heart disease remains rampant,<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers will work toprevent it, tweaking traditional predictiontools and creating new ones as a preemptivestrike against heart disease to eliminatesneak attacks in people without obvioussymptoms <strong>of</strong> disease.“We’ve learned a lot already about discoveringthe silent signals <strong>of</strong> the heart,” Dr. deLemos said, “and have great hope that biggerthings will come.”Dr. Amit KheraSO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE17

Brave New World:High TechMedicine<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> innovateswith many different technologiesto advance medical discoveryand revolutionize patient careBy Debbie Bolles

Using advancedtechnology, such asthis recently installedpositron emissionmammography (PEM)device used for breastcancer detection,Dr. Robert Lenkinskiplans to test newimaging agents that willprovide more detaileddisease information.By modifying the settings <strong>of</strong> the magnetduring an MRI scan, Dr. Changho Choi, associatepr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> radiology in the AdvancedImaging Research Center (AIRC), enhanced themagnetic resonance spectroscopy and identifieda protein that accumulates in the tumor cells<strong>of</strong> patients such as Mr. Smith with a specificgenetic mutation. When Mr. Smith’s symptomsworsened, his doctors noted huge spikes <strong>of</strong> thisprotein showing up on a research study scan.They have since treated the tumor and the levels<strong>of</strong> this protein have fallen. Mr. Smith now walkswithout difficulty and his seizures are gone.“This marks the first time a mutational biomarkerhas been identified through imaging,”said Dr. Elizabeth Maher, associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>internal medicine and neurology and neurotherapeutics,and the lead investigator in thisclinical trial. “It is a major breakthrough inour ability to treat patients.” Dr. Maherholds the Theodore H. Strauss Pr<strong>of</strong>essorshipin Neuro-Oncology.<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers and cliniciansdaily are using new imaging technology toimprove diagnosis and treatment, <strong>of</strong>ten probingdisease processes at the molecular level. Otherimaging innovations at the medical centerinclude more precise and less invasive imagingtools, development <strong>of</strong> contrast agents thatliterally “light up” disease processes never beforeseen and application <strong>of</strong> imaging devices fornonsurgical treatments.Dr. Neil R<strong>of</strong>sky, chairman <strong>of</strong> radiology,expects imaging technologies to become morepervasive in medical procedures and diagnostictests as advancements continue.“We’ll be able to visualize processes at alevel previously impossible and be able to usethat information in real time to make decisionsabout therapies that may optimize efficaciesfor patients,” said Dr. R<strong>of</strong>sky, who holds theEffie and W<strong>of</strong>ford Cain Distinguished Chair inDiagnostic Imaging.One example <strong>of</strong> this type <strong>of</strong> microscopicdetail involves how researchers at the AIRC aredeveloping hyperpolarized solutions for usein MRIs. Pyruvate, a naturally occurring metabolite,or small molecule, can be manipulated toincrease its sensitivity to MR signals, includingwhen it metabolizes into lactate. Lactate isproduced during cellular respiration as glucosebreaks down.“It’s a complicated method for increasingthe MR signal <strong>of</strong> specific molecules in metabolicpathways. You inject those, and you can see asignal you otherwise would not see,” said Dr.Robert Lenkinski, pr<strong>of</strong>essor and vice chairman<strong>of</strong> research in radiology, who is testing hyperpolarizedagents, along with Dr. Dean Sherry,pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> radiology and director <strong>of</strong> the AIRC,and Dr. Craig Malloy, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> internalmedicine and radiology in the AIRC and holder<strong>of</strong> the Richard A. Lange Chair in Cardiology.After injecting hyperpolarized pyruvate intothe body intravenously, doctors can potentiallysee how much <strong>of</strong> a person’s heart muscle ismetabolizing well, based on the MR image <strong>of</strong>pyruvate’s changes.“You can tell which part <strong>of</strong> the heart isdoing well and which is not. That will help indesigning an intervention or drug, or assessingif a treatment is working,” said Dr. Lenkinski.In similar research but using differenttechnology, Dr. Sumer, the robotic surgery expertfor head and neck cancer removal, is workingwith Dr. Jinming Gao, pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> pharmacologyin the Harold C. Simmons ComprehensiveCancer Center, to develop nanotechnologybasedfluorescent contrast agents for MR cancerimaging. Using imaging agents, the researchershave developed injectable pH-sensitivenanoparticles that light up with fluorescence inthe low-pH tumor environment. Because mostsolid cancers are slightly acidic, this <strong>of</strong>f-to-onmechanism fluorescently identifies the tumor’sborders, allowing the surgeon to remove thecancer more accurately.The research team also is creating nanoparticleswith targeting proteins on their surfacethat will direct the nanoprobes to bloodvessels feeding a tumor, stromal cells aroundthe tumor, and the cancer cells themselves.Still to come, another research team willdevelop tracers for positron emission tomography(PET) used in cancer diagnosis andtreatment. Dr. Xiankai Sun, assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> radiology, plans to use funds from a CancerPrevention and Research Institute <strong>of</strong> Texasgrant to purchase a biomedical cyclotron, amachine that produces radioisotopes for production<strong>of</strong> PET tracers. Medical institutions orresearch centers that have their own cyclotronscan produce a variety <strong>of</strong> PET tracers on-site forimmediate use.Taking advantage <strong>of</strong> new imaging technologyremains a priority at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>.In October 2011, the first positron emission“ This marks the first time a mutational biomarkerhas been identified through imaging.”mammography (PEM) unit was installed atthe Mary Nell and Ralph B. Rogers MagneticResonance Imaging Center on the NorthCampus. This technology helps pinpoint cancerin women with dense breast tissue and showstumor characteristic detail.Imaging technology also has expanded tonovel treatment methods. A new type <strong>of</strong>ultrasound uses the heat <strong>of</strong> high-intensityfocused ultrasound (HIFU) waves for noninvasivesurgery, such as uterine fibroid removal.<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers also plan to testMR-guided HIFU for prostate cancer treatment.“A tremendous amount <strong>of</strong> energy isdeposited in a very tiny spot. We irradiatewith ultrasound,” Dr. R<strong>of</strong>sky said.Revolutionizing radiation therapyAs associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> health studies at TexasWoman’s University, Dr. Kristin Wiginton isquite knowledgeable regarding the latest medicaltechnology. She never imagined, however,becoming a pioneer in testing a new radiationtreatment for breast cancer.After being diagnosed, Dr. Wiginton faced adifficult decision. Because heart disease runs inher family, she knew that traditional radiation—Dr. Elizabeth Maher2223

therapy potentially could damage her heart. Soshe took a risk, becoming the first woman toparticipate in a clinical trial at <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>using precisely focused high-beam radiation totreat breast cancer. After five radiation treatmentsin 2011, the results are encouraging. Thestudy still is under way.“I feel I made the right decision volunteeringfor this clinical trial,” said Dr. Wiginton. “Allin all, I think my recovery and comfort levelshave been much better than if I had gonethrough traditional whole-breast radiation.”This first trial in the region using the AccurayCyberKnife System not only cut treatment timeby 83 percent for Dr. Wiginton and other trial“ We are the pioneers in advancedtechnology We are the pioneers in radiation in advanced oncology, buttechnology there is a fine radiation line between oncology, curing butthere cancer is and a fine preserving line between quality curing <strong>of</strong> life.”cancer and preserving quality <strong>of</strong> life.”—Dr. Hak Choyparticipants, it also illustrates the real results<strong>of</strong> cutting-edge research into new radiationtherapies and technologies embraced by<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>.“We are the pioneers in advanced technologyin radiation oncology, but there is a fine linebetween curing cancer and preserving quality<strong>of</strong> life,” said Dr. Hak Choy, chairman <strong>of</strong>radiation oncology and holder <strong>of</strong> the NancyB. and Jake L. Hamon Distinguished Chair inTherapeutic Oncology Research.The balancing act means killing as muchcancer as possible with radiation while minimizingharm to healthy tissue. It’s a challengethat <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> radiation oncologistsface and make advancements in constantly.The stars in <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>’s radiationoncology arsenal include the Gamma KnifePerfexion system, which effectively treatsmultiple tumors in the brain, the CyberKnifehigh-beam radiation system and the Vero, amachine that directs radiation precisely whereneeded through stereotactic body radiationtherapy, or SBRT.Without the human element, however, suchmachinery would be useless. Some <strong>of</strong> themost renowned radiation oncology experts inthe country conduct breakthrough research at<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>, including Dr. Robert Timmerman,vice chairman <strong>of</strong> radiation oncologyand pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> neurological surgery.Dr. Timmerman, one <strong>of</strong> the nation’s top expertson SBRT, led the CyberKnife breast cancertrial and currently is co-leading a multi-institutionalstudy comparing the effectiveness <strong>of</strong>minimally invasive surgery versus SBRT in 400non-small cell lung cancer patients.“In the past, patients have been <strong>of</strong>feredlimited treatment options for this highly deadlydisease,” said Dr. Timmerman, holder <strong>of</strong> theEffie Marie Cain Distinguished Chair in CancerTherapy Research. “This trial will show us howbest to deploy both therapies and optimizethem for a given patient.”In a related study, Dr. Timmerman also istesting hyp<strong>of</strong>ractionated image-guided radiotherapyon non-small cell lung cancer patients.This type <strong>of</strong> treatment uses advanced imaging,motion control and dosimetry principlesto deliver treatments at higher doses, andwith more precision. These methods includemonitoring movement <strong>of</strong> lung cancer tumorsthrough imaging techniques as a patientbreathes and then adjusting radiation beamsaccordingly.Since most tumors are closely situatedwithin normal tissues, potent radiation can bea double-edged sword. With these and otheradvances, however, radiation therapy is becomingfaster, safer and more precise, as well as lessrecovery-intensive for patients.A picture in Dr. Choy’s <strong>of</strong>fice <strong>of</strong> a radiationtherapy machine used to treat a boy for ringwormat an Italian hospital in 1903 is a starkreminder <strong>of</strong> just how far this technology hasevolved. In his 20-plus years as a radiationoncologist, Dr. Choy has seen significant advancements– such as radiation treatments evolvingfrom inpatient to outpatient procedures.“We are truly the most sophisticated centerfor radiation therapy. Our patients come fromall over the world seeking the best technologyand the experts in the field,” Dr. Choy said.For his part, Mr. Perdue says he’s an idealexample and an avid proponent <strong>of</strong> the benefits<strong>of</strong> such high tech medical delivery.“There are so many new and better waysto do things. We, as patients, need to be opento those new findings and techniques,” he said.“If we’re not, I think we’re missing the boatand making a grave mistake.”Researchers develop effective radiation protocolwith fewer treatments | by Robin RussellYour doctor diagnoses you with prostate cancer, and your mind reels. You are scared, worry about loss <strong>of</strong>sexual function and maybe don’t even want to discuss it.Men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer currently must consider several treatment options – activesurveillance, radiation therapy, surgical removal <strong>of</strong> the gland – for this typically slow-growing disease.For those who choose radiation therapy, treatments for localized prostate cancer typically take 42 to 45days, spanning eight to nine weeks.Thanks to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical Center researchers using the latest technologies in a series <strong>of</strong> clinicaltrials, however, new protocols are being discovered.In a recent multicenter trial, researcherstweaked increasingly higher doses <strong>of</strong> ultra-preciseradiation known as stereotactic body radiationtherapy (SBRT), and found it safe and effective forpatients with low- to intermediate-risk prostatecancer, with fewer treatments needed.The linchpin <strong>of</strong> <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>’s SBRTprogram is the Vero. Installed in 2011, it is theonly one in North America. The system – whichinitially is being used to treat patients withprostate and lung cancer – combines threedifferent imaging technologies with a gimbaledX-ray delivery head, allowing physicians to followand treat a moving target safely.“The Vero gives us the most precise linearaccelerator that can spare normal tissuewhile taking care <strong>of</strong> cancer,” said Dr. Hak Choy,chairman <strong>of</strong> radiation oncology.Trial researchers used SBRT to treat patientswith localized prostate cancer in just five 30-minute sessions every other day, over the course <strong>of</strong> two weeks.“We were trying to develop a fast, convenient, outpatient, non-invasive treatment without injuringthe urethra, the bladder or the rectum,” said Dr. Robert Timmerman, vice chairman <strong>of</strong> radiation oncologyand pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong> neurological surgery.Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men, with some 230,000 cases diagnosed annually in theU.S. About half <strong>of</strong> those who are treated undergo radiation therapy. Not everyone is cured, however, becausesome tumors are resistant to radiation.SBRT has been used effectively for patients with lung, liver and brain cancers. The <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>study tested whether high-potency treatments could work in a moving target like the prostate, which shiftsconsiderably due to normal bladder and bowel functioning.To avoid injuring healthy tissue, researchers used beams <strong>of</strong> radiation that were only millimeters largerthan the target itself. That narrow scope helped avert consequences such as rectal injury, impotence anddifficulty urinating.The second phase <strong>of</strong> the clinical trial, completed in fall 2010, increased the dosage in participants by10 percent. More than 90 percent <strong>of</strong> the 50 patients involved tolerated the therapy well.Following clinical trials, <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> researchers will work with a multicenter consortium to developa next-step protocol to further improve the therapy.Dr. Robert Timmermantalks with radiationtherapist Lindsay Henryabout the Vero, the latestimaging technologyin <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>’sarsenal <strong>of</strong> stereotacticbody radiation therapyequipment.24SO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE25

MOMENTSDISCOVERYOFBy Dr. Bruce A. Beutler, as told to Deborah WormserIn 1993, Dr. Bruce Beutler – one <strong>of</strong><strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical Center’sfirst Howard Hughes MedicalInstitute (HHMI) investigators –embarked on a five-year journeythat led to his discovery <strong>of</strong> howthe innate immune system recognizesand responds to infectionin mammals, an achievement thatearned him the 2011 Nobel Prize inPhysiology or Medicine. Dr. Beutlerrecently returned to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>as director <strong>of</strong> the newCenter for the Genetics <strong>of</strong> HostDefense and holder <strong>of</strong> theRaymond and Ellen Willie DistinguishedChair in CancerResearch, in Honor <strong>of</strong> Laverneand Raymond Willie Sr. Here, hedescribes the painstaking workthat led to his discovery and thepressures bearing down uponhim in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1998.

Dr. Beutler’s father transformshis son’s fascinationwith nature into a quest forknowledge“My father encouraged me to go to medical school.And I am glad that he did.”My interest in science was sparked at an earlyage. When I was quite young I was interested innature, especially animals, and kept lists <strong>of</strong>birds I had seen. I still go birding when I have achance. I think the first spark <strong>of</strong> interest inscience had to do with the aesthetic pleasure <strong>of</strong>nature. One day, my father (scientist Dr. ErnestBeutler) suggested that what I was doing wasobservation rather than science. He explainedthat science meant asking specific questionsand addressing them through experimentationin order to gain insight into how things work.My father was a distinguished biomedicalresearcher, a member <strong>of</strong> the National Academy<strong>of</strong> Sciences and winner <strong>of</strong> many awards. WhenI was about 14, I began working in his laboratoryat the City <strong>of</strong> Hope Medical Center in Duarte,Calif. There I learned a great deal about how topurify proteins and analyze them, and also afair amount about genetics. I loved lab workand devoted myself to it as much as I could.I graduated early from high school and hada lot <strong>of</strong> advanced placement credit when, at 16,I went to college at the University <strong>of</strong> California,San Diego (UCSD), so I finished in two years.I certainly learned a lot about basic science, includinggenetics, at UCSD. But I was in a greathurry and actually looked on college, with itsmany humanities requirements, as an impedimentto becoming an independent researcher.I first learned about endotoxin, also knownas lipopolysaccharide (LPS), from UCSD pr<strong>of</strong>essorDr. Abraham Braude [associate pr<strong>of</strong>essor <strong>of</strong>internal medicine from 1953 to 1957 at whatwas then <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical School <strong>of</strong>the University <strong>of</strong> Texas]. Later, understandingLPS formed the core <strong>of</strong> myresearch, but at that time it wasjust a casual introduction. Ididn’t see it in its full contextin those days. I saw itmore as a laboratoryAt the age <strong>of</strong> 14,Bruce Beutler beginsworking in his father’slaboratory at theCity <strong>of</strong> Hope MedicalCenter in Duarte,Calif.curiosity and didn’tknow how importantit was in immunity andin disease.My father encouragedme to go tomedical school, and Iam glad that he did.At the University <strong>of</strong>Chicago School <strong>of</strong>Medicine, I learnedabout the principalchallenges in biomedicine, which tend to changequite slowly over time. I was one <strong>of</strong> thosepeople who went to medical school to learnabout the pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> disease and to understandwhat the big questions were.I first came to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> in 1981when I was matched to the house staff trainingprogram (internship). <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> wasmy first choice because I knew that I would getoutstanding training here. And I did.Dr. Donald Seldin was one <strong>of</strong> my teachers,along with Dr. Daniel Foster, Dr. Jean Wilsonand other greats <strong>of</strong> medicine and biomedicalscience. I spent a year as an internal medicineintern, and then a year as a neurology resident.The neurology program was run byDr. Roger Rosenberg, who had made a strongpitch to recruit me.Infection connectionDuring my clinical training, I saw what aproblem infection could be. Remember, I hadlearned something about LPS – endotoxin –from Dr. Braude and I began to think about itquite a lot in clinical terms, and to take note<strong>of</strong> the damage it could do. LPS is released fromGram-negative bacteria, sometimes evenmore after antibiotic therapy has begun thanbeforehand, and it causes fever, shock, abnormalities<strong>of</strong> blood coagulation and organ injury.This process is usually what kills, not theinfection. I began to wonder why that was.Did the bacteria utilize LPS as a virulencefactor? Or was it simply a structural element,and in that case, was it the host reaction thatwas excessive? And why would excessivereactivity be retained in the course <strong>of</strong> evolution?At that point, it hadn’t really occurred to meto address the question.After two years <strong>of</strong> residency, I went toRockefeller University, where my work demonstratedthat tumor necrosis factor (TNF), aninflammatory protein the body produces inresponse to pathogens, is an extremely importanteffector protein <strong>of</strong> the innate immunesystem. It plays a part both in inflammationand in resisting infection. And it turned out tobe an excellent therapeutic target: TNF blockadeis now a standard way <strong>of</strong> treating manyinflammatory diseases.I returned to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> in 1986 asan assistant pr<strong>of</strong>essor.With the passage <strong>of</strong> time, I realized that thekey question about innate immune responses,especially where infection was concerned butperhaps more generally too, was “how iseverything started?”How is it that LPS activates the macrophage,which then makes TNF? What’s the receptorfor LPS? And how do we become aware <strong>of</strong> aninfection during the first minutes or hoursafter we encounter microbes? In reality, theseare all variants <strong>of</strong> the same question.Our work was fairly fruitless from 1988 to1992 because <strong>of</strong> the way we went about it.We tried to use classical immunological methodsto find the difference between certain micethat couldn’t respond to LPS and other micethat could. We also used analytical biochemistryand we used expression cDNA cloning.None <strong>of</strong> these methods led anywhere.Applying geneticsThe real epiphany for me was embracing classicalgenetics, starting in 1993, to try to solvethe problem. And that was not accidental. Idon’t think I would have done it just anywhere.Genetics was so much a part <strong>of</strong> life here at<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>, and it was also a place whereone could quickly learn about what everyoneelse was doing. The students in my lab wouldtalk to students in other labs; there were reallyno barriers. And they would come back andchat with me about the latest innovations andabout how to get things done.First learns aboutendotoxin, also known aslipopolysaccharide (LPS)Graduates from UCSDwith bachelor’s <strong>of</strong> arts,biology, at the age <strong>of</strong> 18Enrolls in the University <strong>of</strong> California,San Diego, at the age <strong>of</strong> 1619641972197419762829

First comes to<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> asan internThere were three somewhatoverlapping phasesto our work: genetic mapping,physical mappingand gene identification.In the first phase, wehad to localize the mutationto a point betweentwo markers on the chromosome.This involveda lot <strong>of</strong> breeding <strong>of</strong> mice,and analysis <strong>of</strong> whetherthey would respond to LPS.In the second phase,we had to clone all theDNA between those twomarkers – about 2.6 millionbase pairs as weoriginally estimated. This involved isolatinghuge pieces <strong>of</strong> DNA in bacterial artificialchromosomes (BACs) and yeast artificial chromosomes(YACs).And in the third phase, we had to discoverthe gene content <strong>of</strong> those BACs and YACs,then search for a mutation in each <strong>of</strong> the geneswe found to find the change in the genomethat caused resistance to LPS in the C3H/HeJstrain <strong>of</strong> mouse. One must remember thatin those days, the entire genome <strong>of</strong> the mousewas terra incognita; there was not even anaccurate estimate <strong>of</strong> the number <strong>of</strong> genes, letalone what they might be.Each phase was tough but each in a differentway. I think the last two phases were thehardest. We mostly identified genes by sequencingthe DNA, and sequencing 2.6 millionbase pairs <strong>of</strong> DNA – about 0.1 percent <strong>of</strong> thegenome – was a real grind in an academiclab. Not only that, but today we know thesize was really about twice what we thought;about 5.2 million base pairs <strong>of</strong> DNA. It wasan assembly line. Someone would isolateBAC clones using markers within thecritical region. Someone else wouldshear BACs with ultrasound andmake libraries <strong>of</strong> the DNAfragments, cloning theminto Escherichia coliFinishes an internship in internal medicine andstarted a residency in neurology (1982-1983)(E. coli), and plating the libraries on agar. Yetanother would pick colonies and inoculatebroth to grow each colony in liquid culture,then prepare DNA for sequencing from culturesthat had grown the day before. Someone elsewould sequence the purified DNA.I myself spent much <strong>of</strong> my time analyzingthe sequence, and writing computer scriptsto facilitate this. I should mention that Drs.Alexander Poltorak and Irina Smirnova, mypostdoctoral researchers at that time and nowindependent scientists at Tufts University,were the tireless heroes <strong>of</strong> this effort, andwithout them, we surely would not have foundthe mutation.Sequencing in the earliest days was donewith radioactive nucleotides. You’d get a ladder<strong>of</strong> bands on a gel and you’d expose it overnightto X-ray film and read <strong>of</strong>f the base pairsthe next day. Betsy Layton, my administrativeassistant, would read and I would type or viceversa. We would read about 4,000 to 5,000bases <strong>of</strong> DNA in a morning, and that wouldbe about the limit a person could toleratereading in one day. Your eyes wouldget tired. Today’s methods can“There were three somewhat overlapping phases toour work: genetic mapping, physical mapping andgene identification.”deliver about 1 million base pairs per second,and certainly nothing <strong>of</strong> the kind we attemptedwill ever be done again.We were reading sequence in this manner in1993 and 1994. Then, using my own funds, Ibought a used ABI 373XL sequencer. That allowedus to sequence about 40,000 base pairsper day if we ran the machine around the clock.And we decentralized our sequencing also,farming it out to numerous core laboratories.Working around the clockWe worked most weekends, and we’d also workuntil late at night. We would look at theresults <strong>of</strong> the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool(BLAST) searches from sequencing that hadbeen done during the day. We would see if ourgenomic sequences had matches in an expressedsequence tag (EST) database. We used bothdbEST (database <strong>of</strong> Expressed Sequence Tags),which was public, and we used the TIGR (TheInstitute for Genomic Research) database,which was proprietary.Both <strong>of</strong> those were databases <strong>of</strong> complementaryDNA (cDNA) sequences, meaning theyrepresented the parts <strong>of</strong> the genome that wereknown to be expressed as messenger RNA.The idea was to look for genes that way. If youBLAST a genomic DNA sequence and it hasan EST match, that part <strong>of</strong> the genome is expressedand is part <strong>of</strong> a gene (with certain caveats;nothing is absolutely certain).Starts research career at RockefellerUniversity where he is lead author <strong>of</strong>the first study to demonstrate theinflammatory activity <strong>of</strong> tumor necrosisfactor (TNF)We cloned that immense span <strong>of</strong> DNAbecause we thought our mutation <strong>of</strong> interestmust be somewhere within it. We refer to sucha span <strong>of</strong> DNA as the “critical region.” Thearray <strong>of</strong> YACs and BACs that contain that part<strong>of</strong> the genome is called the “contig.” Alexander,Irina and I spent most <strong>of</strong> two years analyzingthe contig. Betsy worked in administration forthe lab but also physically organized massiveamounts <strong>of</strong> data, inoculated colonies, helpedread the sequence files and helped with theBLAST searches.We’d open 50 or 60 BLAST searches and havethem going at the same time – all open onthe toolbar <strong>of</strong> the computer. Sometimes we’dhave a memory problem and everythingwould shut down, which was most frustrating.Once, out <strong>of</strong> the blue, I received a telephonecall from someone at the National Centerfor Biotechnology Information, where theBLAST servers were housed, and the caller toldme, “You’ve been doing too many BLASTsearches and you can’t do that many anymore.”So for a time I cut back, mainly by stoppingthe recursive searches <strong>of</strong> old sequences asfrequently as I had been doing them. I alsobought a Linux computer <strong>of</strong> my own to BLASTlocally after a while. They don’t complainabout things like that these days.By the summer <strong>of</strong> 1998, we had finished sequencingalmost the entire contig and I knewwe were running out <strong>of</strong> anything to sequence.It was as though you’ve explored 90 percent<strong>of</strong> a room looking for a lost cufflink and thoroughlycovered the room and looked undereverything and you’ve looked at practicallyeverything except one s<strong>of</strong>a. And you know ithas to be under there, or else it’s going to benowhere in the room at all. It was that kind <strong>of</strong>Returns to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>as anassistant pr<strong>of</strong>essorand assistantinvestigator at theHoward HughesMedical Institute19811982198319863031

Has an epiphany—began embracingclassical genetics“We knew we had opened a new windowin immunology.”feeling: that we were running out <strong>of</strong> anythingto sequence and the probability <strong>of</strong> finding themutation was increasing with every BAC thatwe’d explore. Either that or we’d made a terriblemistake <strong>of</strong> some kind, and the mutationwasn’t in the critical region at all.And we had learned only in May 1998 thatour HHMI funding was going to end in August2000. This was very disappointing because we’dreally worked so hard on this difficult projectand that was what they had encouraged us todo, but they had run out <strong>of</strong> patience.A powerful matchOn Sept. 5, 1998, I was in my study at home atabout 9:30 p.m. We were doing BLAST analysis<strong>of</strong> the BAC I17, and I suddenly saw a powerfulmatch between one <strong>of</strong> our genomic sequencesand an EST. Then I saw another match. Eachwas nearly perfect, and I was confident that thiswas not a pseudogene. Looking further, I sawthat the target gene was known as Toll-likereceptor 4 (Tlr4), named for its similarity to theDrosophila Toll gene. And I also saw stronghomology to the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor,which I knew produced a strongly inflammatorysignal. I knew, too, that the Toll family hadleucine-rich repeats, as did CD14 – the oneprotein that was known to be involved in LPSsignaling, though it was not the product <strong>of</strong>the LPS locus. All these facts were exciting. But<strong>of</strong> course, they didn’t yet prove that Tlr4 wasthe gene we were after.I remember telephoning Alexander immediately,and later telephoning my father totell him about it, too, because I felt almostsure that this was the gene, based onthe fact that we had been nearly exhaustivein covering the criticalregion if nothing else. Thatvery night, I designedprimers to amplify the cDNA for Tlr4, andthe next morning Alexander and I had themsynthesized.By evening, he had begun to amplify usingpreparations <strong>of</strong> cDNA from the mutant C3H/HeJ strain and the control C3H/HeN strains <strong>of</strong>mice. It was a very long cDNA – more than4,000 base pairs. We were very skilled at shotguncloning, using ultrasound to break up apiece <strong>of</strong> DNA, by that time. We’d shatter theDNA with ultrasound and then we’d cloneall the pieces into a sequencing vector that hadprimer sites so we could sequence in both directions.We decided to fragment the band andsequence it in depth; then align the reads withPhrap, an assembly program. We saw the sequenceabout a week later, but couldn’t view itwith consed, the definitive program for visualizingaligned sequence, until Sept. 15. That wasthe day we were certain we saw the mutationin C3H/HeJ mice for the very first time, andthat was the second moment <strong>of</strong> excitement.I think it was the most thrilling moment <strong>of</strong>my career. It occurred over in the Y building[Green Research Building]: the critical moment<strong>of</strong> finding the mutation that distinguishedendotoxin unresponsive mice from the controlmice. I remember going to the computer inthe corner <strong>of</strong> our lab to look at it and then I’dwalk away and do some work and then goback and look at it again and again. After fiveyears <strong>of</strong> searching, you can hardly believe itwhen you’ve really found what you’ve beenlooking for, given the many frustrations andfalse starts. But, indeed, it was real. Still, therewas one final piece <strong>of</strong> pro<strong>of</strong> missing.We knew <strong>of</strong> another strain <strong>of</strong> mice –C57BL/10ScCr – that also couldn’t respond toLPS. And we were confident on genetic groundsthat they had a defect in the same gene. Welooked at this second strain <strong>of</strong> mouse and wefound we couldn’t amplify the cDNA at all,nor any part <strong>of</strong> the gene. We did a Southernblot (a test to determine if a DNAsample contains a specific geneticsequence) to see if we coulddetect the gene by probingit on a nylon membrane,and we couldn’t detectthe gene that way either.It seemed that in thecontrol strain, knownas C57BL/10ScSn, thegene was there, but inthe C57BL/10ScCrstrain, the gene was gone.Eventually, by sequencing,we found that74,000 base pairs <strong>of</strong> DNAwere missing from thegenome <strong>of</strong> this mouse. OnlyTlr4 was excised; no other geneswere harmed.That was really incontrovertibleevidence. Here we had two different alleles:One was a point mutation, one was a largedeletion. The first was likely to destroy Tlr4,and the second certainly did so. Both <strong>of</strong> themcaused endotoxin resistance. We concludedthat Tlr4 must be necessary for the responseto endotoxin.Finding the C57BL/10ScCr mutationmight have occurred perhaps a week later, nomore than that, because we were quite confidentthat we had really found the relevant locus.By Sept. 30, 1998, we had submitted ourpaper to Science.The paper was reviewed quite promptly,and there were only minor revisions to bemade. It was published in December 1998. Weknew we had opened a new window inimmunology, discovering how the innate immunesystem “sees” microbes. And we hadfound the very molecule that initiates Gramnegativeseptic shock.Returns to <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong>as Director <strong>of</strong>the new Center forthe Genetics <strong>of</strong> HostDefenseWins Shaw Prize in LifeScience and MedicineIs awarded the 2011Nobel Prize in Physiologyor MedicineA powerful match is found, leading to confirmatoryexperiments, and the writing <strong>of</strong> a landmark paperpublished in Science that December1993199820082011Is elected to the National Academy <strong>of</strong>Sciences and the Institute <strong>of</strong> Medicine3233

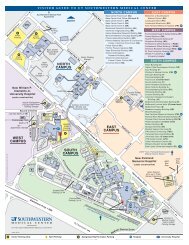

The Hospital <strong>of</strong> the FutureDesigned around the needs <strong>of</strong> patients and their families, the new<strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> University Hospital will be as innovative as the scientificdiscoveries for which the medical center is knownby Russell RianU.S. News & World Report has ranked <strong>UT</strong> <strong>Southwestern</strong> Medical Center as the top hospital in theDallas-Fort Worth region, with six nationally recognized specialties.University Hospital - Zale Lipshy was one <strong>of</strong> just three hospitals in the nation to earn thePatient Voice Award for Academic Medical Centers from Press Ganey, an independent firm that trackspatient safety and satisfaction.University Hospital - St. Paul ranks No. 1 in Texas for survival rates for heart transplants and in thetop 5 percent <strong>of</strong> programs in the country.University Hospitals & Clinics were named to the “Most Wired” list by Hospitals & Health Networks.So, what’s next?Envisioning – and building – the hospital <strong>of</strong> the future.1SO<strong>UT</strong>HWESTERN MEDICINE 35