ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer - Center for Jewish ...

ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer - Center for Jewish ...

ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer ib singer - Center for Jewish ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Lawyers<br />

Without Rights<br />

Jews and the Rule of Law<br />

Under the Third Reich<br />

by Carol Kahn Strauss<br />

On April 7, 1933, shortly after assuming power, Adolf Hitler<br />

ordered all non-Aryan attorneys to be relieved of their civil service<br />

positions, including university professorships and administrative<br />

positions throughout the legal system. The effect was<br />

devastating: at the time of the proclamation, there were almost<br />

20,000 lawyers in Germany, and about half of them were <strong>Jewish</strong>.<br />

The numbers, and the accomplishments, are staggering. In<br />

Berlin alone, there were 3,400 lawyers, of whom approximately<br />

2,000 were <strong>Jewish</strong>. Jews who had been trained<br />

as jurists worked as teachers, judges, notaries,<br />

administrators, and trial advocates. They were<br />

experts in commercial law, contracts law, labor<br />

law, penal law, family law and civil procedure.<br />

They developed theories of sociology and the<br />

law, pioneered modern concepts of women’s<br />

rights, and expanded the definitions of<br />

free speech. All of these were subsequently<br />

denounced as “<strong>Jewish</strong> perversions” by the Nazis.<br />

How had Jews become so numerous in the<br />

German legal profession?<br />

One poss<strong>ib</strong>le reason is ideological: throughout <strong>Jewish</strong><br />

history, the rule of law was of central importance. Traditional<br />

Judaism is a religion of law, whose important precepts, codes and<br />

guidelines are found in the B<strong>ib</strong>le, the Talmud, and rabbinic decisions.<br />

In the traditional <strong>Jewish</strong> view, law is holy and a necessary<br />

part of religious life.<br />

A second reason was practical. Secular law — the legal systems<br />

of the nations in which Jews lived — also mattered to Jews,<br />

especially during the 19th century when, with the onset of<br />

emancipation, the state regulated almost all of their activities.<br />

Jews were enmeshed in legal systems whether they were religious<br />

or not.<br />

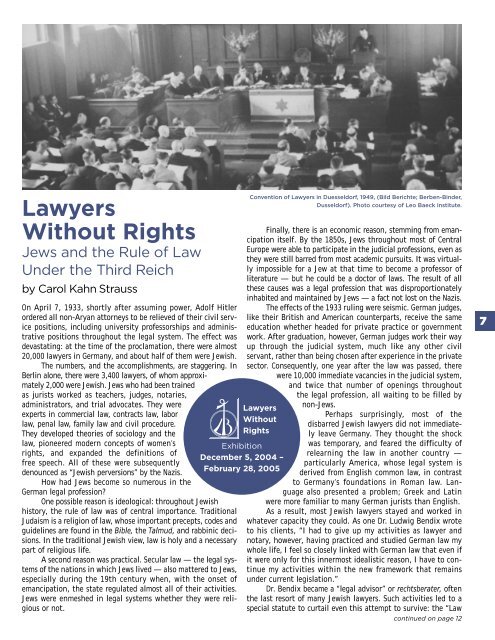

Convention of Lawyers in Duesseldorf, 1949, (Bild Berichte; Berben-Binder,<br />

Dusseldorf). Photo courtesy of Leo Baeck Institute.<br />

Finally, there is an economic reason, stemming from emancipation<br />

itself. By the 1850s, Jews throughout most of Central<br />

Europe were able to participate in the judicial professions, even as<br />

they were still barred from most academic pursuits. It was virtually<br />

imposs<strong>ib</strong>le <strong>for</strong> a Jew at that time to become a professor of<br />

literature — but he could be a doctor of laws. The result of all<br />

these causes was a legal profession that was disproportionately<br />

inhabited and maintained by Jews — a fact not lost on the Nazis.<br />

The effects of the 1933 ruling were seismic. German judges,<br />

like their British and American counterparts, receive the same<br />

education whether headed <strong>for</strong> private practice or government<br />

work. After graduation, however, German judges work their way<br />

up through the judicial system, much like any other civil<br />

servant, rather than being chosen after experience in the private<br />

sector. Consequently, one year after the law was passed, there<br />

were 10,000 immediate vacancies in the judicial system,<br />

and twice that number of openings throughout<br />

the legal profession, all waiting to be filled by<br />

Lawyers<br />

non-Jews.<br />

Perhaps surprisingly, most of the<br />

Without<br />

disbarred <strong>Jewish</strong> lawyers did not immediate-<br />

Rights ly leave Germany. They thought the shock<br />

Exh<strong>ib</strong>ition<br />

was temporary, and feared the difficulty of<br />

relearning the law in another country —<br />

December 5, 2004 –<br />

particularly America, whose legal system is<br />

February 28, 2005<br />

derived from English common law, in contrast<br />

to Germany’s foundations in Roman law. Language<br />

also presented a problem; Greek and Latin<br />

were more familiar to many German jurists than English.<br />

As a result, most <strong>Jewish</strong> lawyers stayed and worked in<br />

whatever capacity they could. As one Dr. Ludwig Bendix wrote<br />

to his clients, “I had to give up my activities as lawyer and<br />

notary, however, having practiced and studied German law my<br />

whole life, I feel so closely linked with German law that even if<br />

it were only <strong>for</strong> this innermost idealistic reason, I have to continue<br />

my activities within the new framework that remains<br />

under current legislation.”<br />

Dr. Bendix became a “legal advisor” or rechtsberater, often<br />

the last resort of many <strong>Jewish</strong> lawyers. Such activities led to a<br />

special statute to curtail even this attempt to survive: the “Law<br />

continued on page 12<br />

37