Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on ...

Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on ...

Review of the management of feral animals and their impact on ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Review</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

biodiversity in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

A resource to aid NRM planning<br />

PAC CRC Report June 2005<br />

Andrew Norris Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Tim Low C<strong>on</strong>sultant, Brisbane<br />

Iain Gord<strong>on</strong> CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Townsville<br />

Glen Saunders NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Primary Industries, Orange<br />

Steven Lapidge Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Keryn Lapidge Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

T<strong>on</strong>y Peacock Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Roger Pech CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra<br />

Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol CRC

<str<strong>on</strong>g>Review</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

biodiversity in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

A resource to aid NRM planning<br />

PAC CRC Report June 2005<br />

A report to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Government Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage prepared by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Pest<br />

Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre

C<strong>on</strong>tributors<br />

Andrew Norris Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Tim Low C<strong>on</strong>sultant, Brisbane<br />

Iain Gord<strong>on</strong> CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Townsville<br />

Glen Saunders NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Primary Industries, Orange<br />

Steven Lapidge Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Keryn Lapidge Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

T<strong>on</strong>y Peacock Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra<br />

Roger Pech CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra<br />

Suggested Citati<strong>on</strong><br />

Norris, A, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Low, T, 2005, <str<strong>on</strong>g>Review</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> biodiversity in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s: A resource to aid NRM planning, Pest<br />

Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol CRC Report 2005, Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol CRC, Canberra<br />

© Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australia<br />

COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMERS<br />

Informati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>tained in this publicati<strong>on</strong> may be copied or reproduced for study, research,<br />

informati<strong>on</strong> or educati<strong>on</strong>al purposes, subject to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> inclusi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> an acknowledgement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this<br />

source.<br />

The views <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> opini<strong>on</strong>s expressed in this publicati<strong>on</strong> are those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> authors <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> do not<br />

necessarily represent those <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Government or <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Minister for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage.<br />

While reas<strong>on</strong>able efforts have been made to ensure that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this publicati<strong>on</strong> are<br />

factually correct, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth does not accept resp<strong>on</strong>sibility for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> accuracy or<br />

completeness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tents, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be<br />

occasi<strong>on</strong>ed directly or indirectly through <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> use <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>, or reliance <strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>tents <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this<br />

publicati<strong>on</strong>.<br />

This project was funded by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Heritage Trust (NHT) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> was managed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage (DEH).

C<strong>on</strong>tents<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 1 Project brief..............................................................................1<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 2 Introducti<strong>on</strong>..............................................................................2<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 3 A status review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s .............6<br />

3.1 Species covered..................................................................................... 6<br />

3.2 Introducti<strong>on</strong>........................................................................................... 6<br />

3.3 Mammals............................................................................................... 6<br />

3.4 Birds ...................................................................................................... 8<br />

3.5 Reptiles <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> amphibians ....................................................................... 9<br />

3.6 Fish........................................................................................................ 9<br />

3.7 Species accounts.................................................................................. 10<br />

3.7.1 House Mouse (Mus musculus) .............................................................10<br />

3.7.2 Brown Rat (Rattus norvegicus)............................................................11<br />

3.7.3 Black Rat (Rattus rattus)......................................................................11<br />

3.7.4 Dingo (Canis familiaris dingo)............................................................12<br />

3.7.5 Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) ......................................................................14<br />

3.7.6 Cat (Felis catus)...................................................................................17<br />

3.7.7 Rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) ...........................................................20<br />

3.7.8 European Hare (Lepus europaeus)......................................................22<br />

3.7.9 Horse (Equus caballus)........................................................................22<br />

3.7.10 D<strong>on</strong>key (Equus asinus) ........................................................................24<br />

3.7.11 Pig (Sus scr<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>a)....................................................................................25<br />

3.7.12 One-Humped Camel (Camelus dromedarius) .....................................29<br />

3.7.13 Swamp Buffalo (Bubalis bubalis).........................................................31<br />

3.7.14 Bali Banteng (Bos javanicus)...............................................................34<br />

3.7.15 Cow (Bos taurus) .................................................................................36<br />

3.7.16 Goat (Capra hircus).............................................................................38<br />

3.7.17 Blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra) .........................................................40<br />

3.7.18 Fallow Deer (Dama dama)..................................................................41<br />

3.7.19 Red Deer (Cervus elaphus)..................................................................42<br />

3.7.20 Sambar Deer (Cervus unicolor)...........................................................43<br />

3.7.21 Rusa Deer (Cervus timorensis)............................................................43<br />

3.7.22 Chital Deer (Axis axis).........................................................................45<br />

3.7.23 Ostrich (Struthio Camelus)..................................................................45<br />

3.7.24 Helmeted Guinea-Fowl (Numida meleagris).......................................46<br />

3.7.25 Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) .............................................................47<br />

3.7.26 Rock Dove (Columbia livia).................................................................47<br />

3.7.27 Laughing Turtle-dove (Streptopelia senegalensis) ..............................48<br />

3.7.28 Spotted Turtle-dove (Streptopelia chinensis).......................................48<br />

3.7.29 Barbary Dove (Streptopelia risoria)....................................................49<br />

3.7.30 Skylark (Alauda arvensis)....................................................................49<br />

3.7.31 House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) ...................................................50<br />

3.7.32 Nutmeg Mannikin (L<strong>on</strong>chura punctulata) ...........................................50<br />

3.7.33 European Goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) .........................................51<br />

3.7.34 Comm<strong>on</strong> Blackbird (Turdus merula)...................................................51<br />

3.7.35 Comm<strong>on</strong> Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) ...................................................52

3.7.36 Comm<strong>on</strong> Myna (Acrido<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>res tristis)...................................................53<br />

3.7.37 Asian House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) ......................................53<br />

3.7.38 Flowerpot Snake (Ramphotyphlops braminus)....................................54<br />

3.7.39 Cane Toad (Bufo marinus)...................................................................55<br />

3.7.40 Comm<strong>on</strong> Carp (Cyprinus carpio) ........................................................57<br />

3.7.41 English Perch (Perca fluviatilis) .........................................................59<br />

3.7.42 Mosquit<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ish (Gambusia holbrooki)....................................................60<br />

3.8 New pests ............................................................................................ 61<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 4 Legislative framework...........................................................64<br />

4.1 Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth legislati<strong>on</strong> ................................................................. 64<br />

4.2 State <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Territory legislati<strong>on</strong>............................................................. 65<br />

4.3 Comments <strong>on</strong> current legislati<strong>on</strong> ........................................................ 71<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 5 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s ...............73<br />

5.1 General c<strong>on</strong>trol techniques.................................................................. 73<br />

5.1.1 Pois<strong>on</strong>ing .............................................................................................73<br />

5.1.2 Shooting ...............................................................................................74<br />

5.1.3 Trapping...............................................................................................75<br />

5.1.4 Mustering .............................................................................................76<br />

5.1.5 Judas technique....................................................................................76<br />

5.1.6 Fencing ................................................................................................76<br />

5.1.7 Water source c<strong>on</strong>trol............................................................................77<br />

5.1.8 Bioc<strong>on</strong>trol ............................................................................................78<br />

5.1.9 Fertility c<strong>on</strong>trol....................................................................................79<br />

5.1.10 COPs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> SOPs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> humaneness........................................................80<br />

5.1.11 Integrated <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> strategies.......................................................81<br />

5.1.12 Pest or resource – <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> value <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> commercial harvesting.......................82<br />

5.1.13 Managing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> not <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> number..........................................83<br />

5.1.14 M<strong>on</strong>itoring – assessing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> effectiveness .............................................83<br />

5.2 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> buffalo............................................................... 85<br />

5.3 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> cane toads.................................................................. 88<br />

5.4 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> camels ............................................................... 91<br />

5.5 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> cats.................................................................... 95<br />

5.6 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> deer ................................................................. 101<br />

5.7 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> goats................................................................ 105<br />

5.8 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> pigs.................................................................. 112<br />

5.9 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> foxes........................................................................ 118<br />

5.10 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> rabbits...................................................................... 125<br />

5.11 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild horses <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> d<strong>on</strong>keys......................................... 138<br />

5.12 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> wild dogs................................................................. 143<br />

5.13 Management <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> carp.......................................................................... 143<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 6 Stakeholder survey ..............................................................147<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 7 Key problems <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> opportunities for investment..............156<br />

7.1 Emerging <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> growing problems...................................................... 156<br />

7.1.1 Deer....................................................................................................158<br />

7.1.2 Camels................................................................................................160

7.1.3 Buffalo................................................................................................163<br />

7.1.4 Banteng ..............................................................................................164<br />

7.1.5 Feral cattle in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Kimberley .............................................................167<br />

7.1.6 D<strong>on</strong>keys near Ka<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rine ....................................................................167<br />

7.1.7 Goats in New South Wales <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Western Australia............................167<br />

7.1.8 Rabbits in South Australia .................................................................168<br />

7.1.9 Pigs in Cape York ..............................................................................169<br />

7.1.10 Dingoes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> dogs in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Territory .....................................170<br />

7.1.11 Foxes, pigs, dingoes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cats in Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ....................................170<br />

7.2 Social <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> industry issues ................................................................. 171<br />

7.2.1 Indigenous communities.....................................................................171<br />

7.2.2 New industries....................................................................................178<br />

7.2.3 Hunting ..............................................................................................180<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 8 Best practice planning.........................................................183<br />

8.1 Best practice planning....................................................................... 183<br />

8.1.1 Eradicati<strong>on</strong> or c<strong>on</strong>trol .......................................................................183<br />

8.1.2 Nil tenure approach – manage <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> by distributi<strong>on</strong> not tenure...185<br />

8.1.3 Management objectives – c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> vs producti<strong>on</strong> ......................185<br />

8.2 Checklist for best practice planning.................................................. 186<br />

8.3 PESTPLAN....................................................................................... 192<br />

Secti<strong>on</strong> 9 Priorities for investment .....................................................194<br />

9.1 Regi<strong>on</strong>al priorities............................................................................. 194<br />

9.1.1 Western Australia...............................................................................194<br />

9.1.2 South Australia...................................................................................195<br />

9.1.3 New South Wales................................................................................195<br />

9.1.4 Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ........................................................................................196<br />

9.1.5 Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Territory .............................................................................196<br />

9.2 Gaps in <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> tools <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> priorities for investment.................. 197<br />

9.3 Knowledge <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> biodiversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> pest animal.............. 199<br />

References..............................................................................................201<br />

Appendix A Workshop summary......................................................216<br />

Appendix B Stakeholder survey form..............................................220<br />

Appendix C Database <strong>on</strong> past NHT funded projects......................228

Table <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> figures<br />

Figure 1 Map <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.............................................................3<br />

Figure 2 Frequency <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> reported to have an <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong><br />

biodiversity. ..........................................................................................148<br />

Figure 3 a) Extent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> tool usage; b) General<br />

effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> tools...................................150<br />

Figure 4 Resp<strong>on</strong>se frequency for likely new <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal incursi<strong>on</strong> pathways....152<br />

List <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> tables<br />

Table 1 Exotic mammals in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that are exp<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir range or<br />

newly col<strong>on</strong>ising it....................................................................................7<br />

Table 2 Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds.............................................8<br />

Table 3 Biodiversity Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds (listed in approximate order <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

severity).....................................................................................................8<br />

Table 4 Exotic fish which have established wild populati<strong>on</strong>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s................................................................................................9<br />

Table 5 Species listed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> red fox Threat Abatement Plan (1999) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

found within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, for which foxes are a known or<br />

perceived threat. This list is not c<strong>on</strong>sidered complete. ...........................17<br />

Table 6 Species listed <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> cat Threat Abatement Plan (1999) for which<br />

cats are a known or perceived threat. This list was compiled some<br />

years ago <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is not c<strong>on</strong>sidered here to be entirely accurate. .................19<br />

Table 7 Species listed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> rabbit Threat Abatement Plan (1999) for which<br />

rabbits are a known or perceived threat. .................................................21<br />

Table 8 Rare species found in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> listed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Draft Threat<br />

Abatement Plan (2004) as threatened by <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> pigs ................................26<br />

Table 9 Species listed in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> goat Threat Abatement Plan (1999)<br />

occurring within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, for which <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> goats are a known<br />

or perceived threat. This list is incomplete. ...........................................39<br />

Table 10 Feral pests that could establish in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> future .............63<br />

Table 11 Australian legislati<strong>on</strong> relevant to <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g>...................66<br />

Table 12 St<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ard operating procedures for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

Developed by Sharp & Saunders (2004). ...............................................80<br />

Table 13 Capacity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> survey resp<strong>on</strong>dents ............................................................147<br />

Table 14 Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> resp<strong>on</strong>dents...................................................................147<br />

Table 15 Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in Australian Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s...............................148<br />

Table 16 Barriers to effective <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong><br />

biodiversity ...........................................................................................151<br />

Table 17 Feral <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> that are exp<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir range in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s...........157<br />

Table 18 Pest populati<strong>on</strong>s susceptible to eradicati<strong>on</strong> over all or part <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir<br />

range within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.................................................................184

Secti<strong>on</strong> 1 Project brief<br />

The Pest Animal C<strong>on</strong>trol Cooperative Research Centre (PAC CRC) was<br />

commissi<strong>on</strong>ed by <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage to<br />

review <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> for biodiversity outcomes in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. This<br />

review was undertaken to help guide future Natural Heritage Trust spending <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

pest <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>trol in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

The outcomes <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> project were to:<br />

• provide opti<strong>on</strong>s for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Government to better target its acti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

investment to limit <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> biodiversity in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

• assist Australian Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficers to assess <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adequacy <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> effectiveness <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

proposed <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal projects in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>text <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Heritage Trust<br />

regi<strong>on</strong>al planning process<br />

• improve <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> regi<strong>on</strong>s’ ability to plan for <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> implement <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

in an integrated way to protect biodiversity.<br />

The report achieves <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se outcomes by:<br />

• summarising relevant Australian Government, State <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Territory legislati<strong>on</strong>, as<br />

well as government <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> private arrangements (Secti<strong>on</strong> 4);<br />

• documenting existing methods for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> (Secti<strong>on</strong> 5);<br />

• assessing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> adequacy <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se methods <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir applicability to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

(addressed in Secti<strong>on</strong>s 5 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> 7);<br />

• identifying gaps <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> opportunities for targeting Comm<strong>on</strong>wealth acti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

investment in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Secti<strong>on</strong> 7).<br />

• developing a checklist for best practice planning <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g>, to assist regi<strong>on</strong>s to develop programs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> projects, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to allow<br />

Government <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ficers to assess those programs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> projects (Secti<strong>on</strong> 8)<br />

• listing rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> projects previously funded under <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Natural Heritage Trust <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r programs (Appendix 3)<br />

The report begins with a major secti<strong>on</strong> that lists <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal species found in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, summarising <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> biodiversity (Secti<strong>on</strong> 3).<br />

1

Secti<strong>on</strong> 2 Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Feral <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> have damaged biodiversity in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <strong>on</strong> a scale unmatched <strong>on</strong><br />

any o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r c<strong>on</strong>tinent.<br />

Australia has lost far more mammals to extincti<strong>on</strong> than any o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r country. Nowhere in<br />

temperate Australia can an intact mammal fauna still be found. To quote from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

federal government’s Acti<strong>on</strong> Plan for Australian Mammals (Maxwell et al. 1996):<br />

‘Australia accounts for about <strong>on</strong>e third <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> all mammal extincti<strong>on</strong>s world-wide since<br />

1600 <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> most extinct Australian mammals were marsupials.’ Most <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extinct<br />

mammals lived in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

When those extincti<strong>on</strong>s are analysed it becomes clear that habitat loss, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten touted as<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> extincti<strong>on</strong>s, is <strong>on</strong>ly a minor c<strong>on</strong>siderati<strong>on</strong>: ‘while l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> clearing has<br />

reduced <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> many species <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> is c<strong>on</strong>tributing to current declines, it has<br />

probably been <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> primary cause <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> extincti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong>e (Maxwell et al. 1996)’.<br />

The Acti<strong>on</strong> Plan explains <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> extincti<strong>on</strong>s thus:<br />

‘In summary, it appears that <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> interacti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> three factors – changes to<br />

habitat caused by introduced herbivores, homogenisati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat following<br />

changed fire regimes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, particularly, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> spread <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> exotic predators – has<br />

been mainly resp<strong>on</strong>sible for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> high extincti<strong>on</strong> rate <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsupials since<br />

European settlement <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australia’.<br />

By ‘exotic predators’, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> authors mean foxes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cats, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> introduced herbivores<br />

include rabbits.<br />

Apart from <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> loss <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammals, <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have degraded vast<br />

tracts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat, promoted invasi<strong>on</strong> by serious weeds, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> pose an <strong>on</strong>going threat to<br />

rare plants <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Buffalo, as <strong>on</strong>e example, have completely denuded some<br />

floodplain areas, caused sheet <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> gully erosi<strong>on</strong>, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> deaths <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> vast paperbark<br />

forests from hydrological changes that include seawater denudati<strong>on</strong>. Feral <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

also cause enormous ec<strong>on</strong>omic losses in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s by destroying crops <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

livestock <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> degrading l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scapes.<br />

The losses from <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> would be much greater except for <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> enormous<br />

amounts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> time, effort <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> m<strong>on</strong>ey poured into pest animal c<strong>on</strong>trol by l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>holders,<br />

biodiversity managers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> pest agencies. Australia is a world leader at c<strong>on</strong>trolling<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> pests for ec<strong>on</strong>omic <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> biodiversity outcomes.<br />

Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> this effort, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> numbers <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some pest species have been reduced, although<br />

o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r pests are increasing in number <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> severity <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. This survey has found<br />

that at least 16 species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal are increasing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir range within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r six species have become newly established. Increased effort<br />

is required to successfully manage <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>se pests.<br />

The federal government spends heavily <strong>on</strong> pest c<strong>on</strong>trol to protect biodiversity. Much<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> that funding is channelled through <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Heritage Trust (NHT), managed by<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment & Heritage (DEH). The NHT has been operating<br />

2

for eight years <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> during that period more than 300 projects with a pest <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

comp<strong>on</strong>ent have been funded.<br />

This report has been produced <strong>on</strong> behalf <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment &<br />

Heritage to guide future NHT spending <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> c<strong>on</strong>trol in<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

The Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are defined as those extensive regi<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australia, generally<br />

unsuitable for cropping, where grazing is <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> use. About 75 per cent <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Australian c<strong>on</strong>tinent falls within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.<br />

Figure 1 Map <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Australian Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

Experts C<strong>on</strong>sulted<br />

Ken Aplin, CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems, Canberra<br />

T<strong>on</strong>y Auld, NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

Keith Bellchambers, biological c<strong>on</strong>sultant, SA<br />

Joe Benshemesh, NT Parks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

David Berman, DNR&M, Qld<br />

John Blyth, CALM, WA<br />

Corey Bradshaw, Charles Darwin University, Darwin<br />

Mike Braysher, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Canberra<br />

Ray Chatto, NT Parks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

John Clarks<strong>on</strong>, EPA, Mareeba, Qld<br />

Peter Copley, Department for Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage, SA<br />

Patrick Couper, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Museum<br />

Nicki de Preu, Department for Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage, SA<br />

3

Am<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>a Dimmock, QDPI&F, Qld<br />

Glen Edwards, NT Parks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

Anne Fergus<strong>on</strong>, DEH, Kakadu Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park, NT<br />

Peter Fitzgerald, DEH, Garig Gunak Barlu Nati<strong>on</strong>al Park, NT<br />

Robert Henzell, Animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Plant C<strong>on</strong>trol Commissi<strong>on</strong>, SA<br />

Michael Hutchis<strong>on</strong>, QDPI&F, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Peter Jesser, DNR&M, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Andrea Johns<strong>on</strong>, Centralian L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Management Associati<strong>on</strong>, Alice Springs.<br />

Paul Josif, Manager, L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> & Sea Management Branch, Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s Council.,<br />

Peter Kendrick, CALM, Karratha, WA<br />

Mike Lapwood, CALM, Broome<br />

Peter Latz, c<strong>on</strong>sultant, Alice Springs<br />

Peter Leys, NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

Paul Mah<strong>on</strong>, NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

Adrian Manning, Australian Nati<strong>on</strong>al University, Canberra<br />

Hugh McNee, NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>, Cobar<br />

Nikola Markus, Threatened Species Network, Sydney<br />

Rh<strong>on</strong>da Melzer, EPA, Qld<br />

Jim Mitchell, DNR&M, Qld<br />

Andrew Moriarty, Rural L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s Protecti<strong>on</strong> Board, Mossvale<br />

Keith Morris, CALM, WA<br />

Greg Mutze, Dept Water, L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biodiversity C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong><br />

Scott O’Keeffe, DNR&M, Qld<br />

Dam<strong>on</strong> Oliver, NSW Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>, Queanbeyan<br />

Colleen O’Malley, Threatened Species Network, Alice Springs<br />

M<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>a Page, University <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>, Gatt<strong>on</strong><br />

Rachel Paltridge, Desert Wildlife Services, Alice Springs<br />

Gary Potter, EPA, Qld<br />

Mark Read, EPA, Cairns, Qld<br />

D<strong>on</strong>ald Rol<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, EPA, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Keith Saalfield, NT Parks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

Kevin Str<strong>on</strong>g, QDNR&M, Qld<br />

T<strong>on</strong>y Start, CALM, WA.<br />

Pacale Taplin, Indigenous L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Management Facilitator, Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Council, NT<br />

Megan Thomas, Qld Herbarium, Brisbane<br />

Laurie Twigg, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Agriculture, WA<br />

Mark Weaver, EPA, Qld<br />

Rick Webster, Ecosurveys Pty Ltd, Deniliquin<br />

Peter Wellings, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Heritage, Darwin<br />

Peter West, NSW DPI<br />

Ray Whear, L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Manager, Jawoyn Associati<strong>on</strong> Aboriginal<br />

Corporati<strong>on</strong>, Ka<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rine<br />

Mark Williams, Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Water, L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Biodiversity C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong>, Adelaide<br />

Bruce Wils<strong>on</strong>, DNR&M, Qld<br />

John Woinarski, NT Parks <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Wildlife Commissi<strong>on</strong><br />

John Doherty, EPA, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Colin Limpus, EPA, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

4

Abbreviati<strong>on</strong>s:<br />

CALM – Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> C<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Management<br />

DNR&M – Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Natural Resources <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mines, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

EPA – Envir<strong>on</strong>ment Protecti<strong>on</strong> Agency, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

DPI&F – Department <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Primary Industries <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Fisheries, Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

5

Secti<strong>on</strong> 3 A status review <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

3.1 Species covered<br />

House Mouse Brown Rat Black Rat<br />

Dingo Red Fox Cat<br />

Rabbit European Hare Horse<br />

D<strong>on</strong>key Pig One-humped Camel<br />

Swamp Buffalo Bali Banteng Cow<br />

Goat Blackbuck Fallow Deer<br />

Red Deer Sambar Deer Rusa Deer<br />

Chital Deer Ostrich Helmeted Guinea-fowl<br />

Mallard Rock Dove Laughing Turtle-dove<br />

Spotted Turtledove Barbary Dove Skylark<br />

House Sparrow Nutmeg Mannikin European Goldfinch<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Blackbird Comm<strong>on</strong> Starling Comm<strong>on</strong> Myna<br />

Asian House Gecko Flowerpot Snake Cane Toad<br />

3.2 Introducti<strong>on</strong><br />

Nearly all exotic vertebrates found within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are described here, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong> biodiversity is summarised. The informati<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s derives<br />

largely up<strong>on</strong> interviews with more than 40 biodiversity managers <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> pest managers<br />

(see page 8) working for state <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> federal agencies. (More than 100 reports <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

journal articles were c<strong>on</strong>sulted as well). By drawing up<strong>on</strong> a wide pool <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> experts<br />

working across <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> assessments <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are more current than<br />

would be possible if reports <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r publicati<strong>on</strong>s were <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main source <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> data.<br />

Indeed, many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> problems identified here are not adequately documented in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

published literature. The informati<strong>on</strong> presented here provides <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> basis for Secti<strong>on</strong> 7<br />

which identifies gaps in spending <strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal <str<strong>on</strong>g>management</str<strong>on</strong>g>.<br />

This chapter begins with secti<strong>on</strong>s that summarise each vertebrate class before<br />

describing species individually.<br />

Species listed <strong>on</strong> Schedule 1 <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Endangered Species Protecti<strong>on</strong> Act 1992, as<br />

facing a threat or perceived threat from a particular <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal, are listed under that<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal. These lists have been edited to remove species that do not occur in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. The lists are not comprehensive, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> not necessarily accurate.<br />

3.3 Mammals<br />

Twenty two species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammal are thought to occupy <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s today.<br />

(The presence <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <strong>on</strong>e species, <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Brown Rat, has not been c<strong>on</strong>firmed but seems<br />

highly likely). Australia has more introduced mammals than introduced birds, reptiles,<br />

or amphibians <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir overall <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s have been far greater. Foxes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cats are<br />

believed to have caused or c<strong>on</strong>tributed to various extincti<strong>on</strong>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> marsupials <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> native<br />

rodents. Foxes, cats, pigs <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> goats pose a threat to various rare <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>/or plants,<br />

6

ei<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r by preying up<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m or by competiti<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat degradati<strong>on</strong>. Rabbits,<br />

goats, buffalo, d<strong>on</strong>keys, pigs, horses, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> cattle – in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> approximate order listed<br />

- have caused major l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scape degradati<strong>on</strong>. Banteng, red deer <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> chital deer have<br />

caused significant l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> degradati<strong>on</strong> more locally.<br />

Feral mammals, unlike o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r groups <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> exotic vertebrates, occur throughout <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. There are vast tracts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> inl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> north-western Australia that do not<br />

support introduced birds, reptiles, amphibians or fish, but <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>re are no Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />

areas, apart from some mangrove forests, that do not support exotic mammals. Most<br />

localities support several species, <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ten half a dozen or more.<br />

Feral mammals have permanently transformed Australia. Ho<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g>ed mammals are now<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> largest <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g> in most terrestrial habitats in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s. Foxes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> cats are<br />

now <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> main mammalian predators. Most habitats are missing several native<br />

mammals because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> predati<strong>on</strong> by <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g>. Many l<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>scapes are permanently<br />

eroded by <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>animals</str<strong>on</strong>g>. As a threatening process, <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammals are most harmful to<br />

o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r mammals, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> to plants. Very few birds are threatened by <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammals within<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Malleefowl is a noteworthy excepti<strong>on</strong>). No reptiles or amphibians<br />

are threatened by <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> mammals within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, apart from marine <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

freshwater turtles, which lose eggs to foxes, dingoes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> pigs, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Great Desert<br />

skink, which apparently suffers predati<strong>on</strong> from <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> predators. Turtles appear to be<br />

particularly susceptible to egg predati<strong>on</strong> from exotic mammals, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> this is a major<br />

cause for c<strong>on</strong>cern (Secti<strong>on</strong> 7).<br />

Regrettably, this survey has found that eight species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> animal are increasing<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir range within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> two species have newly col<strong>on</strong>ised (Table 1).<br />

The blackbuck <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rattus tanezumi (see under Black Rat) may also represent new<br />

col<strong>on</strong>ists but informati<strong>on</strong> is lacking.<br />

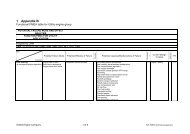

Table 1 Exotic mammals in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s that are exp<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir range or newly<br />

col<strong>on</strong>ising it.<br />

Exp<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>ing in range Where Scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> problem<br />

Black Rat<br />

Red Fox<br />

Pig<br />

One-humped Camel<br />

Swamp Buffalo<br />

Feral Cow<br />

Fallow Deer<br />

Chital Deer<br />

NT (Kakadu)<br />

NT (?) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Qld<br />

NT (Top End)<br />

WA, NT<br />

NT (Arnhem L<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>)<br />

WA (Kimberley)<br />

NSW, QLD<br />

NSW, QLD<br />

7<br />

Low (?)<br />

High (?)<br />

Locally high<br />

High<br />

Locally high<br />

High<br />

Medium<br />

High<br />

New to <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s Where Scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> problem<br />

Red Deer<br />

Rusa Deer<br />

NSW, QLD<br />

NSW, QLD<br />

High<br />

High<br />

Insufficient informati<strong>on</strong> Where Scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> Problem<br />

Blackbuck<br />

Rat (Rattus tanezumi)<br />

Spreading in QLD?<br />

Present in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s?<br />

Unknown<br />

Low

3.4 Birds<br />

Thirteen (or 14) species <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> bird occupy <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s today, although very few<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>m use natural or semi-natural areas. Six are c<strong>on</strong>fined to towns <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> homesteads,<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> two barely occur within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (Table 2). The o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r five make some use<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> semi-natural or natural habitats but <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong> a limited scale <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> within limited areas<br />

(Table 2). As well, ostriches may occur in scattered locati<strong>on</strong>s. Western Australia <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Territory are almost free <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds.<br />

Table 2 Distributi<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitat status <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds<br />

C<strong>on</strong>fined to towns <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> homesteads <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir vicinity<br />

Helmeted Guinea-fowl<br />

Rock Dove<br />

Laughing Turtle-dove<br />

Spotted Turtle-Dove<br />

Barbary Dove<br />

House Sparrow<br />

Only marginally present within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s (<strong>on</strong> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> south-eastern edge)<br />

Skylark<br />

European Goldfinch<br />

Widespread <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> found at least occasi<strong>on</strong>ally in semi-natural habitats<br />

Nutmeg Mannikin – Uses disturbed woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> grassl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s in coastal Queensl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Blackbird - In towns, homesteads <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> disturbed riparian forest in New South Wales<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Myna – Nests in woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s al<strong>on</strong>g <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern edges <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s z<strong>on</strong>e<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Starling – Widespread in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> eastern half <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> sometimes<br />

nesting in woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> remnants<br />

Woodl<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s, rainforests, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> o<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r natural habitats within <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s are, almost<br />

without excepti<strong>on</strong>, completely free <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds. Feral mammals, by c<strong>on</strong>trast, have<br />

invaded almost every habitat. Because <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir very limited presence within natural<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> semi-natural areas, <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds do not appear to be having a major <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> up<strong>on</strong><br />

biodiversity. Hybridisati<strong>on</strong> between Mallards <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Black Ducks is <strong>on</strong>e c<strong>on</strong>cern, <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

competiti<strong>on</strong> between Starlings <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Mynas for tree holes used by native birds is<br />

ano<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>r, although no threats to any listed species were recorded. (Starlings pose a<br />

threat to vulnerable Superb Parrots, but outside <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s.)<br />

Table 3 Biodiversity Impacts <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds (listed in approximate order <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> severity)<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Starling Competes with declining birds for nest holes<br />

Mallard Hybridises with native Black Duck<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Blackbird Probably spreads <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> seeds <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> some serious shrubby weeds<br />

such as Boxthorn <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> Blackberry<br />

Comm<strong>on</strong> Myna Competes with birds for nest holes, but not known to<br />

compete with any rare species<br />

Nutmeg Mannikin Apparently competes with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Chestnut-breasted Mannikin<br />

(a comm<strong>on</strong> bird) in disturbed habitats close to towns<br />

8

Although <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> biodiversity <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g>s appear minor at present, this situati<strong>on</strong> could<br />

change. If Nutmeg Mannikins col<strong>on</strong>ise <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Nor<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>rn Territory (which seems likely)<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y could compete seriously with <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Yellow-rumped Mannikin, a bird <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

c<strong>on</strong>servati<strong>on</strong> c<strong>on</strong>cern. If Helmeted Guinea-fowl spread widely through <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g><br />

Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>y could exert a significant <str<strong>on</strong>g>impact</str<strong>on</strong>g> in a wide range <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> habitats due to<br />

<str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g>ir large size, potential abundance (as recorded in Africa) <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> potential to serve as a<br />

prey species for dingoes <str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g> foxes. Many <str<strong>on</strong>g>of</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> <str<strong>on</strong>g>feral</str<strong>on</strong>g> birds found in <str<strong>on</strong>g>the</str<strong>on</strong>g> Rangel<str<strong>on</strong>g>and</str<strong>on</strong>g>s<br />