in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada - Davidsonia

in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada - Davidsonia

in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada - Davidsonia

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Volume 18, Number 2April 2007<strong>Davidsonia</strong>A Journal of Botanical Garden Science

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 41EditorialThe paper by Wharton and Lancaster published <strong>in</strong> this issue servesto rem<strong>in</strong>d us of problems that arise when we br<strong>in</strong>g rare or unusualplants <strong>in</strong>to cultivation. Wharton’s account of re-<strong>in</strong>troduction, <strong>in</strong> thiscase of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, reports earlier at least partially successful<strong>in</strong>troductions. Lancaster provides the background of successful cultivation.The satisfy<strong>in</strong>g part of their story is that their re-<strong>in</strong>troductionsare from seed.Botanical gardens provide expertise for <strong>in</strong> situ conservation as wellas be<strong>in</strong>g repositories for ex situ activities. The ex situ function is not anissue for common forms, but movement of rarities <strong>in</strong>to cultivation maylead to difficulties that arise from a collector’s urge to ‘have one of those<strong>in</strong> our garden’. It is not clear from the Wharton and Lancaster paper ifthe distribution of seed was accompanied by a request for the recipientsto keep a concise diary of the handl<strong>in</strong>g and progress of the materialsto ensure the collection of (standardized) <strong>in</strong>formation to <strong>in</strong>crease therecorded experience that came from grow<strong>in</strong>g these materials. The opportunityto have access to this and other seem<strong>in</strong>gly rare and uncultivatedmaterial would be well exploited by ask<strong>in</strong>g each recipient to shareexperience ga<strong>in</strong>ed dur<strong>in</strong>g early cultivation of new material. This simplecontribution would ensure that the knowledge is reta<strong>in</strong>ed and not left tochance. While there may be a few seek<strong>in</strong>g to control technical <strong>in</strong>formationfor profit, the Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) providesa framework for <strong>in</strong>formation to be gathered at one or more botanicalgardens and shared with the country of orig<strong>in</strong>.The ideal that botanical garden collections conta<strong>in</strong> accessions of anadequate sound sample size (some say 5 seed source specimens and notmerely 5 copies of a s<strong>in</strong>gle clone) presents a dilemma for collectors whof<strong>in</strong>d a s<strong>in</strong>gle specimen with perhaps only vegetative prospects. The col-Ia<strong>in</strong> E.P. Taylor, Professor of Botany and Research Director,UBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research,6804 SW Mar<strong>in</strong>e Drive, <strong>Vancouver</strong>, BC, <strong>Canada</strong>, V6T 1Z4.ia<strong>in</strong>.taylor@ubc.ca

42lection and successful propagation of vegetative material is an importantfirst step, it is important to tra<strong>in</strong> local people to collect seed, and toreturn to the site when seed is available. Both of these are important,though costly <strong>in</strong> both time and money; but they do contribute to thesponsor<strong>in</strong>g botanical garden’s essential obligations to the Conventionfor Biological Diversity.The paper by Saarela is another example of how researchers canprovide reliable <strong>in</strong>formation when the biological conditions, <strong>in</strong> this caseflower<strong>in</strong>g, are unknown. Individual ‘case studies’ such as this add tothe reliable body of horticultural knowledge. Eventually there will beenough natural history to launch a doctoral dissertation that will addressthe specific mechanisms of bamboo flower<strong>in</strong>g.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 43The North American flower<strong>in</strong>gof the cultivated founta<strong>in</strong>bamboo, Fargesia nitida(Poaceae: Bambusoideae), <strong>in</strong><strong>Vancouver</strong>, <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>, <strong>Canada</strong>AbstractFargesia nitida, the founta<strong>in</strong> bamboo, is a hardy and attractivebamboo that is commonly cultivated <strong>in</strong> North America. Because itsreproductive structures were not known until recently, there have beenseveral taxonomic issues with this species. Fargesia nitida began flower<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> 1993 <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom for the first time s<strong>in</strong>ce its orig<strong>in</strong>alcollection <strong>in</strong> its native Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> 1886, and it has s<strong>in</strong>ce been expected toflower <strong>in</strong> North America. Here I document its recent flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>Vancouver</strong>,<strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>, and I provide a morphological description offlower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals of this species.Introduction“With the commencement of flower<strong>in</strong>g of some European plants of umbrellabamboo, we should soon observe flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> this species <strong>in</strong> cultivationelsewhere. We may also predict that the founta<strong>in</strong> bamboo will soon come<strong>in</strong>to flower. If so, we have one of nature’s most <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g phenomena unfold<strong>in</strong>gbefore us.”– Thomas R. Soderstrom, 1979The bamboosBamboos (subfamily Bambusoideae Luerss.) are a large clade ofgrasses (Poaceae) that <strong>in</strong>cludes 1,200–1,400 woody and herbaceousspecies (Grass Phylogeny Work<strong>in</strong>g Group, 2001; Bamboo PhylogenyJeffery M. Saarela, Research ScientistResearch Division, Canadian Museum of Nature, P. O. Box 3443, Station D,Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4, <strong>Canada</strong>

46The genus FargesiaThe genus Fargesia <strong>in</strong>cludes clump-form<strong>in</strong>g woody bamboos withshort-necked rhizomes and dense, spatheate, unilateral <strong>in</strong>florescences(Stapleton, 1994a, b; Li et al. 2006). However, reproductive structuresare known only <strong>in</strong> about 25% of species (Gielis et al. 1999), and theoccasional acquisition of new flower<strong>in</strong>g material for described Fargesiataxa has <strong>in</strong>dicated that not all share the same reproductive morphology,which has frequently necessitated generic realignments (e.g., Stapleton,1994b; Li et al. 2006). Li et al. (2006) <strong>in</strong>dicated that the genus <strong>in</strong>cludesabout 90 species (with 77 endemic to Ch<strong>in</strong>a), but they noted that itwould be more appropriate to <strong>in</strong>clude several of their Fargesia species <strong>in</strong>a segregate genus, Bor<strong>in</strong>da. The generic circumscription of Fargesia, andtherefore its number of known species, rema<strong>in</strong>s uncerta<strong>in</strong>.Two Fargesia taxa, F. murielae (Gamble) Yi, and F. nitida (Mitford) P. C.Keng ex T. P. Yi, are closely related species (Guo et al. 2001, 2002; Guoand Li, 2004) that are widely cultivated <strong>in</strong> Europe and North Americabecause of their extreme hard<strong>in</strong>ess and attractiveness. Fargesia murielae(the umbrella bamboo or Muriel’s bamboo) (Figure 1, see rear cover)is characterized by its gracefully arch<strong>in</strong>g culms, whereas F. nitida (theFounta<strong>in</strong> Bamboo) is more upright <strong>in</strong> stature. Additional characteristicsof the culm leaves, culms, and foliage leaves further dist<strong>in</strong>guish thesetaxa (e.g., Stapleton 1995b; Li et al. 2006). Both species are native toCh<strong>in</strong>a, where they grow at high elevations (Li et al. 2006). The historyof the <strong>in</strong>troduction of both species <strong>in</strong>to the West has been documentedthoroughly (Stapleton. 1995a, b; Del Tredici, 1998;). In brief, F. nitidawas <strong>in</strong>itially grown <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom from seed collected <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a<strong>in</strong> 1886 (Stapleton, 1995b), and F. murielae was collected live <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong>1907 and subsequently propagated (vegetatively) at the Arnold Arboretumat Harvard University (Stapleton, 1995a; Del Tredici, 1998). All<strong>in</strong>dividuals of these species now grown <strong>in</strong> the West are believed to orig<strong>in</strong>atefrom these orig<strong>in</strong>al Ch<strong>in</strong>ese collections. Despite their ecologicaland economic importance <strong>in</strong> their native habitats, and their importanceas ornamentals <strong>in</strong> Europe and North America, the generic aff<strong>in</strong>ities,morphological characteristics, species circumscriptions, and typificationsof these taxa have been extremely controversial, largely because

48Photo: J.M. SaarelaFigure 2. A flower<strong>in</strong>g branch of Fargesia nitida.unilateral <strong>in</strong>florescences (Stapleton, 1994a, b; Li et al. 2006). AlthoughI did not study the type specimens of the commonly cultivated Fargesiataxa, I determ<strong>in</strong>ed these <strong>in</strong>dividuals to be F. nitida on the basis of theirrelatively upright culms. F. murielae, the other commonly cultivated Fargesiaspecies <strong>in</strong> North America, has culms that arch gracefully. Additionally,these plants grow<strong>in</strong>g on the UBC campus are known locally asF. nitida (Douglas Justice, personal communication, December 2006).Photo: J.M. SaarelaFigure 3. Inflorescence of Fargesia nitida [Saarela 798 (CAN)]. Scale bar = 5 mm.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 49Photo: E.P La Founta<strong>in</strong>eFigure 4. Two <strong>in</strong>dividuals of Fargesia nitida outside the MacMillan build<strong>in</strong>g on theUniversity of <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> campus. In December 2006 the leftmost clump wasflower<strong>in</strong>g vigorously, whereas the rightmost clump was not flower<strong>in</strong>g. When thisphoto was taken (August 2007), the leftmost <strong>in</strong>dividual was nearly devoid of foliage,likely a response to its earlier flower<strong>in</strong>g.There are numerous reports on plant enthusiast, nursery, and gardencentre websites <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g that F. nitida began flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> North America<strong>in</strong> the early to mid 2000s. This species was also observed flower<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> <strong>Vancouver</strong> at the VanDusen Botanical Garden <strong>in</strong> 2005 (D. Justice,personal communication). At the University of <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>, I observedsix separate plant<strong>in</strong>gs of F. nitida; <strong>in</strong> December, three of thesewere flower<strong>in</strong>g vigorously, and three were not. Because F. nitida reportedlydies after flower<strong>in</strong>g (many garden centre websites <strong>in</strong>dicate that theyare no longer sell<strong>in</strong>g “old generation” founta<strong>in</strong> bamboos because oftheir imm<strong>in</strong>ent flower<strong>in</strong>g and death). I revisited each of the six plants <strong>in</strong>early June, 2007, to determ<strong>in</strong>e if this was the case. At that time, each ofthe three <strong>in</strong>dividuals that were observed flower<strong>in</strong>g vigorously <strong>in</strong> Decem-

50ber had some reproductive structures at the anthesis stage, suggest<strong>in</strong>gthat these plants had probably flowered cont<strong>in</strong>uously over the previoussix month period, and that they had not f<strong>in</strong>ished flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> early June.However, the density of reproductive structures on each of these plantswas substantially reduced (I did not formally quantify flower<strong>in</strong>g density).In early June, the flower<strong>in</strong>g clump outside of the UBC StudentUnion Build<strong>in</strong>g showed no signs of ill health – the plant was dense withfoliage and looked remarkably similar to its non-flower<strong>in</strong>g neighbour<strong>in</strong>gplant. Large portions of the two clumps that had flowered vigorouslybeh<strong>in</strong>d the MacMillan build<strong>in</strong>g, however, were nearly devoid offoliage, suggest<strong>in</strong>g that flower<strong>in</strong>g had affected their survival (Figure 4).The two <strong>in</strong>dividuals at this location that were not flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Decemberappeared vigorous and healthy <strong>in</strong> August 2007. It is not clear whythe three flower<strong>in</strong>g plant<strong>in</strong>gs were not all affected <strong>in</strong> the same manner,but s<strong>in</strong>ce the flower<strong>in</strong>g cycle <strong>in</strong> these <strong>in</strong>dividuals is presumably not yetcomplete, it seems premature to determ<strong>in</strong>e conclusively their ultimatepost-flower<strong>in</strong>g fate.Despite casual observations that F. nitida has flowered recently <strong>in</strong>North America (see above), I am not aware of any previous reports<strong>in</strong> the scientific literature document<strong>in</strong>g this event — its first flower<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> North America, approximately 120 years after its seed was firstcollected <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a, and approximately 13 years after its first recordedflower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom (Renvoize, 1993). Collections madefrom these flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals of F. nitida (as well as some <strong>in</strong>dividualsnot <strong>in</strong> flower) <strong>in</strong> <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> therefore provided an opportunity tocharacterize the morphology of its reproductive structures, and fill thisgap <strong>in</strong> the taxonomic literature. The follow<strong>in</strong>g detailed morphologicaldescription of leaf foliage and reproductive morphology of F. nitidais based on collections made from these cultivated specimens. I hopethat these details will help to clarify species circumscriptions of thisand other wild and cultivated Fargesia species. A detailed description ofculm foliage (i.e., culm sheaths and culm blades) is not provided herebecause the available collections did not have sufficient material fromthis portion of the plants. For a detailed description of culm morphology,see Li et al. (2006).

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 51Description of leaf foliage and reproductivemorphology of Fargesia nitidaFargesia nitida (Mitford) P. C. Keng ex T. P. Yi, J. Bamboo Res.4(2): 30. 1985.Note—The taxonomy and nomenclature of Fargesia nitida is complex.For detailed <strong>in</strong>formation on the type specimen, correct applicationof the name F. nitida, and synonymy, see Stapleton (1995a,b, 1999), Li(1996), and Brummitt (1998).Foliage leaf sheaths glabrous, occasionally pubescent towards collar;marg<strong>in</strong>s not fused, usually smooth, sometimes pubescent near apex,hairs 0.2–0.5 mm long; auricles absent; oral setae 0.3–2.0 mm long,0.02–0.04 mm wide, not fused, straight or slightly s<strong>in</strong>uous, smoothwith occasional, m<strong>in</strong>ute, crater-like glands observable at 50x. Foliageleaf blades narrowly l<strong>in</strong>ear-lanceolate, 3–6.6 cm long, 4–7 mm wide,constricted at base, abaxial surface m<strong>in</strong>utely pubescent, apex pubescent-scabrous,adaxial surface glabrous, marg<strong>in</strong>s smooth, serrulate, orwith antrorse hairs to 0.35 mm. Outer ligules a ciliolate rim 0.1–0.2mm. Inner ligules 0.4–0.9 mm, truncate or rounded, glabrous or pubescent,marg<strong>in</strong>s glabrous or ciliate, cilia to 0.1 mm. Synflorescences(2–)3–3.6 cm long, 0.7–1 cm wide, strongly compressed, subtended by3–4 spathes; spathes purple to brown, strongly enclos<strong>in</strong>g synflorescencebase, strongly nerved, glabrous, marg<strong>in</strong>s usually glabrous but occasionallydensely ciliose, hairs to 0.7 mm, <strong>in</strong>ner most spathe exceed<strong>in</strong>g spikelet,often term<strong>in</strong>ated by blade; rachis and pedicels terete, 0.2–0.3 mm<strong>in</strong> diameter, usually glabrous, occasionally m<strong>in</strong>utely serrulate towardsnodes, longer hairs occasional particularly at nodes, nodes occasionallydensely hairy, hairs to 1 mm; branches <strong>in</strong>serted unilaterally, 1.4–1.8 mmlong. Spikelets 11.2–13.4 mm long, laterally compressed; florets 2 or3, the third floret usually sterile and smaller, disarticulat<strong>in</strong>g above theglumes. Glumes 2, lanceolate, purple, usually strongly keeled, sometimesflattened, particularly towards apex, surface glabrous, occasionallypubescent towards apex, keels glabrous, occasionally m<strong>in</strong>utely serrulatetowards apex; first glume 4.7–6.5 mm long, 1-3–nerved; second glume

526.8–8 mm, 5-nerved. Lemmas 9.8–11 mm long, green at base becom<strong>in</strong>gpurple towards apex, strongly keeled, strongly 7-nerved, keels smoothbecom<strong>in</strong>g pubescent towards apex, marg<strong>in</strong>s smooth, backs glabrous(sometimes with occasional hairs) becom<strong>in</strong>g scabrous towards apex;awns m<strong>in</strong>ute and mucro-like, 0–0.7 mm. Paleas 8.9–10.7 mm long, 1-3–nerved, bifid, divided apically for 0.2–0.7(–0.9) mm, sulcate, glabrousbut becom<strong>in</strong>g scabrous towards apex. Stamens 3; anthers 3.6–4.8 mmlong, 0.5-0.9 mm wide, bright yellow; filaments 0.1 mm wide, translucent.Styles 2, feathery. Lodicules 2, 2.1–2.8 mm long, triangularshaped, glabrous, apex pubescent, hairs 0.2–0.4 mm long. Fruit notobserved.Specimens exam<strong>in</strong>ed: <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>University of <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> (UBC), N side of Student UnionBuild<strong>in</strong>g (SUB), lower level, planted on either side of door, westmostclump, <strong>in</strong> flower, 13 Dec 2006, Saarela 798 (CAN, UBC); UBC, N sideof SUB, lower level, planted on either side of door, eastmost clump,not <strong>in</strong> flower, 13 Dec 2006, Saarela 799 (CAN); UBC, beh<strong>in</strong>d MacMillanbuild<strong>in</strong>g, directly along wall, westmost clump, 13 Dec 2006, Saarela 801(CAN); UBC, beh<strong>in</strong>d MacMillan build<strong>in</strong>g, directly along wall, eastmostclump, 13 Dec 2006, Saarela 802 (CAN).AcknowledgementsI am grateful to Douglas Justice (UBC Botanical Garden) for <strong>in</strong>formation,Paul Hamilton (Canadian Museum of Nature) for help withmicroscope photography, and Lynn Gillespie (Canadian Museum ofNature), Christopher Sears (University of <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>), and ananonymous reviewer for constructive comments on earlier versions ofthe manuscript.ReferencesBamboo Phylogeny Group. 2005-2006. Bamboo Biodiversity. http://www.eeob.iastate.edu/research/bamboo/<strong>in</strong>dex.html. Accessed 30 July 2007.Bhattacharya, S., Das, M., Bar, R., and Pal, A. 2006. Morphological and molecularcharacterization of Bambusa tulda with a note on flower<strong>in</strong>g. Annalsof Botany 98: 529-535.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 53Brummitt, R. K. 1998. Report of the Committee for Spermatophyte. Taxon47: 863-872.Clayton, W.D., Harman, K. T., and Williamson, H. 2006 onwards. GrassBase- The Onl<strong>in</strong>e World Grass Flora. http://www.kew.org/data/grassesdb.html.Accessed 26 February 2007.Del Tredici, P. 1998. The first and f<strong>in</strong>al flower<strong>in</strong>g of Muriel’s bamboo. Arnoldia58: 11-17Filgueiras, T. S., and Pereira, B. A. S. 1988. On the flower<strong>in</strong>g of Act<strong>in</strong>ocladumverticillatum (Gram<strong>in</strong>eae: Bambusoideae). Biotropica 20: 164-166.Frankl<strong>in</strong>, D. C. 2004. Synchrony and asynchrony: observations and hypothesesfor the flower<strong>in</strong>g wave <strong>in</strong> a long-lived semelparous bamboo. Journal ofBiogeography 31: 773-786.Gielis, J., Goetghebeur, P., and Debergh, P. 1999. Physiological aspects ofdevelopment and experimental reversion of flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Fargesia murielae(Poaceae: Bambusoideae). Systematics and Geography of Plants 68: 147-158.Grass Phylogeny Work<strong>in</strong>g Group. 2001. Phylogeny and subfamilial classificationof grasses (Poaceae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 88:373-457.Guo, Z.-H., Chen, Y.-Y., Li, D.-Z., and Yang, J.-B. 2001. Genetic variation andevolution of the alp<strong>in</strong>e bamboos (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) us<strong>in</strong>g DNAsequence data. Journal of Plant Research 114: 315-322.Guo, Z.-H., Chen, Y.-Y., and Li, D.-Z. 2002. Phylogenetic studies on theThamnocalamus group and its allies (Gram<strong>in</strong>eae: Bambusoideae) basedon ITS sequence data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 22: 20-30.Guo, Z.-H., and Li, D.-Z. 2004. Phylogenetics of the Thamnocalamus groupand its allies (Gram<strong>in</strong>eae: Bambusoideae): <strong>in</strong>ference from the sequencesof GBSSI gene and ITS spacer. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution30: 1-12.Janzen, D. H. 1976. Why bamboos wait so long to flower. Annual Review ofEcology and Systematics 7: 347-391.John, C. K., and Nadgauda, R. S. 2002. Bamboo flower<strong>in</strong>g and fam<strong>in</strong>e. CurrentScience 82: 261-262.Judziewicz, E. J., Clark, L. G., Londoño, X., and Stern, M. 1999. AmericanBamboos. Smithsonian Institution Press, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.

54Keeley, J. E., and Bond, W. J. 1999. Mast flower<strong>in</strong>g and semelparity <strong>in</strong> bamboos:the bamboo fire cycle hypothesis. American Naturalist 154: 383-391.Li, D. Z. 1996. Proposal to conserve S<strong>in</strong>arund<strong>in</strong>aria Nakai (Gram<strong>in</strong>eae) with aconserved type. Taxon 45: 321-322.Li, D. Z. 1997. The flora of Ch<strong>in</strong>a Bambusoideae project – problems andcurrent understand<strong>in</strong>g of bamboo taxonomy <strong>in</strong> Ch<strong>in</strong>a. In The Bamboos.Edited by G. P. Chapman. Academic Press, London.Li, Z., and Denich, M. 2004. Is Shennongjia a suitable site for re<strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>ggiant panda: an appraisal on food supply. The Environmentalist 24: 165-170.Li, D., Guo, Z., and Stapleton, C. 2006. Fargesia Franchet. In Flora of Ch<strong>in</strong>a:Poaceae, Volume 22. Edited by Z. Y. Wu, P.H. Raven, and D.Y. Hong.Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press, Beij<strong>in</strong>g and St. Louis.pp. 74-96.Ramanayake, S. M. S. D., and Yakandawala, K. 1998. Incidence of flower<strong>in</strong>g,death and phenology of development <strong>in</strong> the giant bamboo (Dendrocalamusgiganteus Wall. ex Munro). Annals of Botany 82: 779-785.Ramanayake, S. M. S. D, and Weerawardene, T. E. 2003. Flower<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a bamboo,Melocanna baccifera (Bambusoideae: Poaceae). Botanical Journal of the L<strong>in</strong>neanSociety 143: 287-291.Renvoize, S. A. 1993. In clos<strong>in</strong>g: S<strong>in</strong>arund<strong>in</strong>aria nitida – <strong>in</strong> flower! BambooSociety (Great Brita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 17: 24.Seifriz, W. 1920. The length of the life cycle of a climb<strong>in</strong>g bamboo: a strik<strong>in</strong>gcase of sexual periodicity <strong>in</strong> Chusquea abeitifolia Griseb. American Journalof Botany 7: 83-94.Soderstrom, T. R. 1979a. The bamboozl<strong>in</strong>g Thamnocalamus. Garden 3 (4): 22–27.Soderstrom, T. R. 1979b. Another name for the Umbrella Bamboo. Brittonia31: 495.Soderstrom, T. R., and Ellis, R. P. 1987. The position of bamboo genera andallies <strong>in</strong> a system of grass classification. In Grass Systematics and Evolution.Edited by T. R. Soderstrom, K. W. Hilu, C. S. Campbell, and M. E.Barkworth. Smithsonian Institution Press, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D. C., U. S. A. pp.225-238.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1994a. The bamboos of Nepal and Bhutan Part I: Bambusa,Dendrocalamus, Melocanna, Cephalostachyum, Te<strong>in</strong>ostachyum, and Pseudostachyum

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 55(Gram<strong>in</strong>eae: Poaceae, Bambusoideae). Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh Journal of Botany 51:1-32.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1994b. The bamboos of Nepal and Bhutan Part II: Arund<strong>in</strong>aria,Thamocalamus, Bor<strong>in</strong>da, and Yushania (Gram<strong>in</strong>eae: Poaceae, Bambusoideae).Ed<strong>in</strong>burgh Journal of Botany 51: 275-295.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1995a. Muriel Wilson’s bamboo. Bamboo Society (GreatBrita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 21: 10-20.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1995b. Flower<strong>in</strong>g of Fargesia nitida <strong>in</strong> the UK. BambooSociety (Great Brita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 22: 17-22.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1996. The Founta<strong>in</strong> Bamboo – Fargesia nitida. BambooSociety (Great Brita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 24: 19-20.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1997. Just when you thought it was safe to get back <strong>in</strong> thewater – comments on a proposal by D–Z Li to conserve S<strong>in</strong>arund<strong>in</strong>aria.Bamboo Society (Great Brita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 26: 25-26.Stapleton, C. M. A. 1999. Yushania vs. S<strong>in</strong>arund<strong>in</strong>aria: good news and bad.Bamboo Society (Great Brita<strong>in</strong>) Newsletter 31: 42-43.Stapleton, C. M. A. 2006. Proposal to conserve the name Arund<strong>in</strong>aria murielaeaga<strong>in</strong>st A. sparsiflora (Poaceae: Bambusoideae). Taxon 55: 227-228.Stapleton, C. M. A. 2006–2007. Bamboo Identification. http://bamboo-identification.co.uk/<strong>in</strong>dex.html.Accessed 30 July 2007.Stapleton, C. M. A. 2007. Bambuseae Nees. In Flora of North America.Volume 24. Magnoliophyta: Commel<strong>in</strong>idae (<strong>in</strong> part): Poaceae, part 1.Edited by M. E. Barkworth, K. M. Capels, S. Long, L. K. Anderton, and M.B. Piep. Oxford University Press. pp. 15-17.Stern, M. J., Goodell, K., and Kennard, D. K. 1999. Local distribution ofChusquea tomentosa (Poaceae: Bambusoideae) before and after a flower<strong>in</strong>gevent. Biotropica 31: 365-368.Tian, B., Chen, Y., Yan, Y., and Li, D. 2005. Isolation and ectopic expression ofa bamboo MADS-box gene. Ch<strong>in</strong>ese Science Bullet<strong>in</strong> 50: 217-224.Wu, Z. Y, Raven, P. H., and Hong, D. H. (Editors). 2006. Flora of Ch<strong>in</strong>a:Poaceae, Volume 22. Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press,Beij<strong>in</strong>g and St. Louis.Zhang, W., and Clark, L. G. 2000. Phylogeny and classification of the Bambusoideae(Poaceae). In Grass Systematics and Evolution. Edited by S. W. L.Jacobs and J. Everett. CSIRO, Melbourne, Australia. pp. 35-42.

56Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, the goat horntree – a two part account of itshistory <strong>in</strong> western cultivation andrecent re<strong>in</strong>troductionPart 1 P. WhartonCarrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a Franchet – Salicaceae (Flacourtiaceae)In 1971 as a forestry undergraduate at the University College ofNorth Wales, Bangor, I often referred to ‘Trees and Shrubs Hardy <strong>in</strong> the<strong>British</strong> Isles’ by W. J. Bean (Bean, 1976). The entry for Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, atree <strong>in</strong> the Flacourtiaceae, conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong>formation that the plant explorer,E. H. Wilson, had collected the species <strong>in</strong> 1908 and <strong>in</strong>troduced it tothe United K<strong>in</strong>gdom from seed obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> western Sichuan (Mup<strong>in</strong>).The plants were raised <strong>in</strong> the U.K. by Messers. Veitch and Sons, anddistributed <strong>in</strong> 1912 as part of their clos<strong>in</strong>g sale. Bean reported, “Itfirst flowered <strong>in</strong> this country <strong>in</strong> the garden of Capt. and Mrs. Desborough,Tulgey House, Broadstone, Dorset, <strong>in</strong> June 1929 and aga<strong>in</strong> thefollow<strong>in</strong>g year, but this specimen, which provided the material for theplate <strong>in</strong> the Botanical Magaz<strong>in</strong>e (Turrill, 1949), died <strong>in</strong> 1931”. This storytypifies the generally ephemeral nature of the early Wilson <strong>in</strong>troductions,to which Roy Lancaster alludes later <strong>in</strong> this article. Bean tells usit grew to flower<strong>in</strong>g size at Bodnant, Gwynedd and Borde Hill, Sussex,but unfortunately, died out dur<strong>in</strong>g or just after World War II. A plantat Kew, though seem<strong>in</strong>gly healthy, died before flower<strong>in</strong>g. It seemedthat the only surviv<strong>in</strong>g specimen <strong>in</strong> the <strong>British</strong> Isles was at Birr Castle<strong>in</strong> Eire, but a second was later found at Rowallane <strong>in</strong> Northern Ireland.I re<strong>in</strong>troduced this tree to cultivation some 20 years after I wasemployed as curator of the David C. Lam Asian Garden at the Uni-Peter WhartonUBC Botanical Garden and Centre for Plant Research,6804 SW Mar<strong>in</strong>e Drive, <strong>Vancouver</strong>, BC, <strong>Canada</strong>, V6T 1Z4Roy Lancaster58 Brownhills Road, Chandlers Ford, Eastleigh,Hampshire, S05 2EG, UK

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 57Photo: Peter WhartonFigure 1. Dashahe Cathaya Reserve, Dalou Shan, northern Guizhou. October 1994.

58versity of <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong> (UBC) Botanical Garden. A cooperativescientific agreement between UBC and the Nanj<strong>in</strong>g Botanical GardenMemorial Sun Yat-sen, <strong>in</strong> Jiangsu, Ch<strong>in</strong>a and my friendship with Dr. HeShan-an, then Director at Nanj<strong>in</strong>g, led <strong>in</strong> 1994 to an <strong>in</strong>vitation to visitthe Dashahe Cathaya Reserve, a remote conservation area <strong>in</strong> the DalouShan <strong>in</strong> northern Guizhou, close to the Chongq<strong>in</strong>g municipal regionborder <strong>in</strong> Sichuan (Figure 1). This reserve conta<strong>in</strong>ed scattered stands ofCathaya argyrophylla (Cathay silver fir) (Figure 2). These trees are oftenperched precariously on overhang<strong>in</strong>g limestone buttresses and are a dist<strong>in</strong>ctivefeature of the table-topped karst mounta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Dalou Shan.We spent 15 memorable days explor<strong>in</strong>g this little known reserve, whichis rich <strong>in</strong> both rhododendrons and a range of wildlife, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g landcrabs. The entire Dalou Shan region was thickly forested and a majorrefuge for the Ch<strong>in</strong>ese tiger before 1959. Sadly, this majestic animal isjust one of many larger mammals that have been hunted almost to ext<strong>in</strong>ctiondur<strong>in</strong>g a time of calamitous forest destruction.My first sight of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a (the goat horn tree; ‘yang jiao shu’<strong>in</strong> Mandar<strong>in</strong>) was along the banks of the Dasha He, a small river thatflows through the centre of the reserve, when I noticed a tree withconspicuous claw-like capsules. I remembered a colour slide taken byTed Dudley (U.S. National Arboretum, Wash<strong>in</strong>gton, D.C.) who photographedthis species (under collection # SABE 245) dur<strong>in</strong>g the firstS<strong>in</strong>o-American Botanical Expedition <strong>in</strong> 1980 to the Shennongjia regionof western Hubei. Dudley was particularly pleased to f<strong>in</strong>d the species<strong>in</strong> the Shennongjia, where it is uncommon, and this unexpected discoverygave me my own ‘botanical golden fleece’. As well, it was the firstrecord of the species <strong>in</strong> the Dashahe Cathaya Reserve. We collectedthe dist<strong>in</strong>ctive sp<strong>in</strong>dle-shaped capsules, which are similar <strong>in</strong> profile toa goat’s horn and often form pendulous clusters of three to five at thebranch tips. At maturity these long, bright green, lightly felted capsulessplit along three sutures, the valves arch<strong>in</strong>g backwards to form a structurerem<strong>in</strong>iscent of the flowers of Clematis texensis. The silky, ribbedcapsule <strong>in</strong>teriors are packed with small, flattened, w<strong>in</strong>ged seeds. A goat’shorn cornucopia, symboliz<strong>in</strong>g abundance, is an accurate metaphor ofthis species’ fecundity. The dist<strong>in</strong>ctive fruits and the flat-topped crown

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 59profile were the two characters needed to spot other specimens <strong>in</strong> thesurround<strong>in</strong>g moist woods. Wilson alludes to these very features <strong>in</strong> ANaturalist <strong>in</strong> Western Ch<strong>in</strong>a (Wilson, 1913)."Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, a wide-spread<strong>in</strong>g flat-topped tree, is very common <strong>in</strong> rockyplaces by the stream-side, and was laden with torpedo-shaped, velvety-grey fruit whichwas not ripe."My collection PW 68, wasacquired at 320m (1050ft) from anopen crowned riverside specimenof just over 11m (36ft) tall. ThePhotos: Peter WhartonFigure 2. Cathaya argyrophylla (Cathay silver fir) <strong>in</strong> the Dashahe region perched at theedges of limestone crags.

60associated ligneous vegetation <strong>in</strong>cluded a similar sized Magnolia <strong>in</strong>signisimmediately next to the goat horn tree. Nearby were f<strong>in</strong>e specimens ofAcer davidii (PW 74) with massive leaves (similar to A. davidii ‘GeorgeForrest’), Liquidambar formosana, and overhang<strong>in</strong>g specimens of Cyclocaryapaliurus and Cladrastis s<strong>in</strong>ensis. The headman of a local village guided us toseveral other Carrierea locations the follow<strong>in</strong>g day. My second collection(PW 84) was from a 15m (49ft) tree grow<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> vigorous secondarymesic forest. The trees here had obviously been ‘drawn up’ by thesurround<strong>in</strong>g forest, yet still displayed full, healthy crowns. They grew<strong>in</strong> small groups or as s<strong>in</strong>gle trees at the base of moist, north-east fac<strong>in</strong>grocky slopes. Despite the th<strong>in</strong> soils, they appeared to receive year roundmoisture. The soils at these sites ranged from moderately to weaklycalcareous. Leachate from the limestone cliffs above percolated downtowards the Dasha He, where the most of the goat horn tree populationsoccurred. Surround<strong>in</strong>g trees <strong>in</strong>cluded, Betula lum<strong>in</strong>ifera, Cornusmacrophylla, Corylus ch<strong>in</strong>ensis and Idesia polycarpa (another member of theFlacourtiaceae [Salicaceae]). These grew amongst a rich herbaceousflora that <strong>in</strong>cluded colonies of a curious, viviparous Senecio bulbiferusand a gargantuan Ligularia wilsoniana (giant groundsel) that had flower<strong>in</strong>gstems up to 3m (9.8ft) tall. Wild pigs evidently excavate and relishthe fleshy roots of the groundsel. Small groups and <strong>in</strong>dividuals of theCarrierea were mixed with<strong>in</strong> the forest along streams or where moisturewas flow<strong>in</strong>g through the soil profile. It is a pioneer species that prefersmoist forest marg<strong>in</strong>s and riparian sites, which, if left undisturbed,will eventually give way to broadleaved evergreen forest dom<strong>in</strong>ated byhusky oak relatives, such as Castanopsis chunii, C. platyacantha and Lithocarpushancei. Much of the lowland forest of this reserve appeared tobe regrowth after clear<strong>in</strong>g for subsistence rice cultivation several hundredyears ago. Vestiges of old terrac<strong>in</strong>g and abandoned walnut (Juglanscathayensis) groves were clearly visible. Today, the ma<strong>in</strong> threat to the reserveis illegal tree cutt<strong>in</strong>g and collection of traditional herbal plants byit<strong>in</strong>erant peasants from the Chongq<strong>in</strong>g municipal region (Sichuan) whoenter from the north. The reserve is also home to a very rare walnutrelative, Annamocarya s<strong>in</strong>ensis (Ch<strong>in</strong>ese hickory), which is at the northernlimit of its distribution.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 61Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a has a wide distribution throughout Hubei, Hunan,Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan between 1300m–1600m(4265–5250ft) elevation. Deforestation at these low elevations hasgreatly fragmented its formerly extensive range. Dur<strong>in</strong>g his travels <strong>in</strong>western Ch<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> early part of the 20 th century, E. H. Wilson describedit <strong>in</strong> most complimentary terms:“This handsome tree is very rare <strong>in</strong> western Hupeh, but common <strong>in</strong> westernSzech’uan, especially by the side of woodland streams up to 1200m (3937ft) altitude.Whilst not form<strong>in</strong>g a tall or even large tree, the much–branched and flat head iswide-spread<strong>in</strong>g; the bark is grey and usually smooth, but <strong>in</strong> very old trees it becomesfurrowed and corrugated. The flowers are ivory-white and of much substance.”(Wilson, 1917).It is clear to me that Dashahe should be protected <strong>in</strong> the longtermand that more botanical fieldwork is warranted <strong>in</strong> this remarkableregion. After my return to <strong>Canada</strong> I distributed seed to botanical <strong>in</strong>stitutionsand <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong> the United K<strong>in</strong>gdom, USA, New Zealandand Ireland.Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, U.K. (PW 68, 84)Wakehurst Place, RBG Kew, U.K. (PW 84)Ness Botanic Garden, University of Liverpool, U.K. (PW 84)Howick Gardens, Northumberland, U.K. (PW 84)Trewithen Gardens, Cornwall, U.K. (PW 84)Mr. Roy Lancaster, Hampshire, U.K. (PW 68, 84)National Botanical Gardens, Glasnev<strong>in</strong>, Ireland (PW 84)University of Wash<strong>in</strong>gton Botanic Gardens, (PW 68, 84)Seattle, WA., U.S.A.Pukeiti Trust Garden, New Plymouth, N.Z. (PW 68, 84)Roy and I would certa<strong>in</strong>ly appreciate obta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g further <strong>in</strong>formationon the location and condition of trees grown from the seeds that weredistributed.

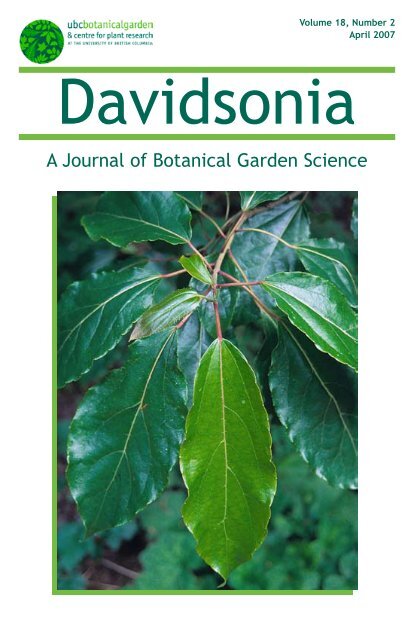

62Botanical descriptionCarrierea is named after the French botanist and horticulturist Elie-Abel Carriere (1818-1896). The specific name calyc<strong>in</strong>a means ‘belong<strong>in</strong>gto the calyx’, or, ‘with a well-developed calyx’.Growth habitIn the wild state, trees generally range from 6-9m (19-29ft) <strong>in</strong> opensituations, while <strong>in</strong> moist, forested locations trees can approach 15m(49ft). Wilson reported older trees with girths up to 1-1.6m (3.2-5.2ft),and occasional veteran trees approach<strong>in</strong>g 2m. No tree I observed <strong>in</strong>the wild had a diameter over 60cm (23”). The bark of young trees islight brown, with a slight silver cast, which contrasts beautifully withthe prom<strong>in</strong>ent chestnut coloured lenticels. These are liberally scatteredalong the trunk and ma<strong>in</strong> branches. Wilson describes the bark of veterantrees as ‘furrowed and corrugated’. Young trees, especially grow<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> open, waterside situations, tend to develop wide-spread<strong>in</strong>g openbranched crowns and eventually assume almost flat-topped profiles.Most trees derived from PW collections grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the U.K. and NewZealand are show<strong>in</strong>g typical, open crowned characteristics. Some young<strong>in</strong>dividuals grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> moist, forested conditions at the UBC David C.Lam Asian Garden are vigorously upright, show persistence of apicaldom<strong>in</strong>ance and seem likely to achieve maximal mature height. Theyoung shoots are <strong>in</strong>itially downy, becom<strong>in</strong>g glabrous by late summer andhave a reddish-green colouration that fades at maturity to light brownwith grayish lenticels. The ma<strong>in</strong> lateral branches close to the trunk arestrongly horizontal, rem<strong>in</strong>iscent of the related Idesia polycarpa. At theouter marg<strong>in</strong>s of the crown they assume a dist<strong>in</strong>ctively vertical pose,even with a full complement of summer foliage.Buds and leavesThe 3-8mm (0.11-0.31<strong>in</strong>) buds are alternate, rounded, reddish andf<strong>in</strong>ely downy, and spilt to unfurl leaves <strong>in</strong> mid to late March (Figure 3,see front cover). The alternate, slightly pendulous leaves are glabrous,dark glossy green above and paler beneath. Leaf shape ranges fromovate or broadly ovate-lanceolate to oblanceolate with a gradual taperto a slender apex. Leaf bases are quite variable, rang<strong>in</strong>g from rounded

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 63or cordate to cuneate. Leaf size is 10-15 x 5-8 cm (4-6 x 1.9-3.1<strong>in</strong>) onmature flower<strong>in</strong>g specimens, while on vigorous trees on moist sites theleaves often resemble those of Populus, often reach<strong>in</strong>g 24-30 x 6-8cm(9.4-11.8 x 2.3-3.1<strong>in</strong>). The leaf marg<strong>in</strong>s are set with regular, 1mm pegliketeeth and have conspicuous, <strong>in</strong>-rolled flanges. Petiole length rangesfrom 2-5cm (0.8-2<strong>in</strong>) and the petiole curves downwards where it attacheswith the leaf-blade. There is a pair of small glands at the junctionof the leaf blade and petiole. These are p<strong>in</strong>kish <strong>in</strong> color (similar to thevegetative buds) and resemble those found <strong>in</strong> Populus. Leaves fall green<strong>in</strong> the late autumn (November) if weather conditions rema<strong>in</strong> frost-free.We have never recorded any autumn colour.FlowersPlants are remarkably variable with respect to flower<strong>in</strong>g. Dr. Quent<strong>in</strong>Cronk and his students have been study<strong>in</strong>g the phylogeny of Carriereaand the genomics of the Salicaceae, and they have shed some lighton this sexual plasticity. Several genera <strong>in</strong> Flacourtiaceae (a considerablenumber of flacourts are now placed with<strong>in</strong> the Salicaceae, (Cronk, 2005)<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Carrierea, are functionally dioecious, yet sporadic occurrencesof monecious and hermaphrodite <strong>in</strong>dividuals occur. The fertile seedpodsof hermaphrodite trees are generally located at the term<strong>in</strong>al positionof the panicle. The same morphology occurs <strong>in</strong> the closely relatedgenus Idesia. It is <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g to speculate about the adaptive advantageof this wide range of sexual options. Both monoecy and especiallydioecy <strong>in</strong>hibit <strong>in</strong>breed<strong>in</strong>g (Quent<strong>in</strong> Cronk, pers. comm., 2005), whichcan have negative effects on a species’ long-term viability, but hermaphroditicbehavior may give the plant survival benefits, when geographicisolation, climatic stress or physical disturbances pose powerfulnatural dangers to their cont<strong>in</strong>uance.Individual flowers are borne <strong>in</strong> erect or spread<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>florescenceson lax term<strong>in</strong>al shoots (Figure 4). The flower masses resemble a candelabra.Wilson described them as “…curiously-shaped, waxy-whiteflowers borne <strong>in</strong> erect panicles” (Wilson, 1913. page 173). The rose-redrachis of the panicles is a most attractive foil for the pale flowers. Upto 10 flowers are produced, each with five heart-shaped, rugose sepals,which functionally replace normal petals. Flower colour varies from

64Photo: Peter WhartonFigure 4. A flower<strong>in</strong>g specimen at the Darts Hill Garden <strong>in</strong> Surrey, BC. July 2006.ivory white through yellowish to greenish white, and Wilson remarkedthat he came across ‘blush’ flower forms. I suspect that these p<strong>in</strong>kishflower forms may be due to normal ag<strong>in</strong>g discolouration. The sepalsform beaker-shaped flowers, with the sepal tips slightly twisted, up to3.1 x 2.5cm (1.2 x 0.98<strong>in</strong>) <strong>in</strong> size. The upper sepal marg<strong>in</strong> is lobed andraised-high <strong>in</strong> relation to the mid-po<strong>in</strong>t from the tip to its po<strong>in</strong>t of attachment.The centres of pistillate flowers are dom<strong>in</strong>ated by a large,vase-shaped, downy ovary, which has three radiat<strong>in</strong>g yellow stigmas atits apex. Form<strong>in</strong>g a boss <strong>in</strong> stam<strong>in</strong>ate flowers or clustered at the baseof the ovary <strong>in</strong> hermaphrodite flowers are numerous short, purplish-redstamens.Lord and Lady Rosse, the owners of Birr Castle sent me a cardsizepr<strong>in</strong>t of a beautiful pa<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g of the goat horn tree <strong>in</strong> full flower <strong>in</strong> 2004by the noted Irish botanical artist Susan Sex. The Birr tree has floweredheavily <strong>in</strong> the last six years provid<strong>in</strong>g a wealth of subject matter for thisf<strong>in</strong>e artist.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 65FruitFruits are dist<strong>in</strong>ctive sp<strong>in</strong>dle or claw shaped capsules, covered <strong>in</strong>dense down (Figure 5). They range <strong>in</strong> size from 7-11 x 2cm (2.7-4.3 x0.78<strong>in</strong>) and are often born <strong>in</strong> clusters of three to five at the branch extremities.The capsules split <strong>in</strong>to three lance shaped valves that re-curveat the tips reveal<strong>in</strong>g masses of papery w<strong>in</strong>ged seeds.Carrieria calyc<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>, <strong>Canada</strong>Plants grown from my seed collections were planted out <strong>in</strong> the DavidC. Lam Asian Garden, <strong>in</strong> UBC Botanical Garden <strong>in</strong> the autumn of 1997(Figure 6). They consisted of seven <strong>in</strong>dividuals of PW 68 and six ofPW 84, but we did not fully understand the importance of abundant, allseason, soil moisture to the vitality of this species. Recent phylogeneticresearch by Cronk and co-warkers at UBC has suggested some ecologicalsimilarities between Carrierea and poplars and willows.We planted our specimens on a range of sites from well-dra<strong>in</strong>edto streamside locations, from deep shade to full sun. The plants thatthrived were those grow<strong>in</strong>g at waterside or on well watered, oxygenatedsites that were rich <strong>in</strong> organic matter. Drought and vole damage re-Photo: Dr. T.R. DudleyFigure 5. The sp<strong>in</strong>dle-shaped fruit of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a (SABE 245). Wild specimenphotographed at the Shennengj<strong>in</strong> region, western Hubei. August 1980.

66Photo: Peter WhartonFigure 6. Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a grow<strong>in</strong>g at the UBC Botanical Garden <strong>in</strong> <strong>Vancouver</strong>,<strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 67duced our collection to 10 <strong>in</strong>dividuals. The largest trees are now (w<strong>in</strong>ter2006-07) just under 7m (23ft) high and grow<strong>in</strong>g with susta<strong>in</strong>ed vigor.In the w<strong>in</strong>ter of 2004-05 four trees were transplanted from drier sitesto sunlit streamside locations and all showed healthy extension growth<strong>in</strong> the summers of 2005 and 2006. So far, we have noticed no pest ordisease problems with our plants (Figure 7 - Front Cover).A number of young trees collected under PW 68 were distributedwith<strong>in</strong> southwestern BC <strong>in</strong> the late 1990’s, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the VanDusenBotanical Garden <strong>in</strong> <strong>Vancouver</strong>, the gardens of Margaret Charltonand Charlie Sale <strong>in</strong> North <strong>Vancouver</strong> and Francisca Darts (Darts HillGarden) <strong>in</strong> south Surrey, and the more exposed garden of Don Martyn<strong>in</strong> Yarrow, BC. The specimen at VanDusen Garden is healthy but small.The Darts Hill Garden tree, a small 2m (6.5ft) specimen, stress-floweredheavily <strong>in</strong> the summer of 2005 after a severe bark <strong>in</strong>jury, but subsequentlydied. This was the first <strong>in</strong>dividual to have flowered <strong>in</strong> NorthAmerica. Charlie Sale reports that his specimen is 7.5m (24.6ft) tall witha tapered, open crown to 4.5m (14.7ft). The vigor of this plant on asteep, south-west fac<strong>in</strong>g slope beneath a canopy of mature Pseudotsugamenziesii (Douglas fir) would appear to be out of character; althoughthere is year-round subsurface water percolat<strong>in</strong>g down the sloped siteand ra<strong>in</strong>fall is close to 2635mm (103<strong>in</strong>) a year. This specimen has neverflowered.Don Martyn’s garden at Yarrow, <strong>in</strong> the lower Fraser Valley, 80 km(50miles) east of <strong>Vancouver</strong> has provided a case study. The tree isplanted <strong>in</strong> the open on flat terra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> heavy clay soils over sand. Hedescribes the tree as multi-stemmed, with a congested central crown 4m(13ft) high by 3m (9.8ft) wide. The Yarrow district gets 60–80kmh (40-50mph) w<strong>in</strong>ds every year and below 0 o C weather often for more than aweek at a time. Recorded temperature range s<strong>in</strong>ce the tree was plantedwas -14° to 37 o C. Average ra<strong>in</strong>fall is about 1785mm (70<strong>in</strong>).Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> New ZealandCarrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a has been grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the central Hawkes Bay areaof the North Island s<strong>in</strong>ce the late 1970’s <strong>in</strong> the garden of Mike andCarola Hudson. They received their orig<strong>in</strong>al plant from Hillier’s Nurs-

68ery around 1980/1981. It appears this plant was derived from from theorig<strong>in</strong>al Birr Castle plant (private communication from Peter Dummerto Roy Lancaster). Dummer, who was Hillier’s master propagator untilhis retirement <strong>in</strong> the 1980s, remembers receiv<strong>in</strong>g the cutt<strong>in</strong>gs from BirrCastle and root<strong>in</strong>g them under mist us<strong>in</strong>g a hormone powder and gett<strong>in</strong>gabout 45% root<strong>in</strong>g strike. The Hudson plant <strong>in</strong>itially grew well to4.5m (15 ft), but collapsed <strong>in</strong> a very dry summer despite heavy water<strong>in</strong>g.A new basal sprout arose emerged and formed a mature 12m (39 ft)tree that flowers every year. Fruit and seed production depend on seasonalweather. Viable seed capsules only develop at the term<strong>in</strong>al flowerof each <strong>in</strong>florescence, which suggests an orig<strong>in</strong> from hermaphroditeflowers. Cutt<strong>in</strong>gs root well but never seem to thrive, and all have so fardied. The two oldest plants of seven grown from self-seed are now 9m(29.5ft) high and flower and fruit regularly. The Hudsons also grow onePW plant, but it has not yet flowered or fruited. They report that thisGuizhou tree has a more spread<strong>in</strong>g habit than the more upright Wilson<strong>in</strong>troduction, although Wilson ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed that his <strong>in</strong>troductions hadflat-headed wide spread<strong>in</strong>g crowns.Part 2 R. LancasterCarrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a <strong>in</strong> <strong>British</strong> cultivationThe only tree of note I have seen <strong>in</strong> <strong>British</strong> or Irish cultivation isfrom the famous Wilson collection, presumably W. 1212, of 1908 collectedfor the Arnold Arboretum and grow<strong>in</strong>g at Birr Castle <strong>in</strong> Co.Offaly, Ireland. This tree, planted <strong>in</strong> 1916 was 16m (52ft) x 39cm (15<strong>in</strong>)when measured <strong>in</strong> 2000 for the Tree Register of Ireland. The recordshows that this tree was purchased from Veitch Nursery dur<strong>in</strong>g the clos<strong>in</strong>gdown sale <strong>in</strong> 1914, which suggests that seed was sent by Wilson directlyto Veitch, although it is equally possible that the nursery receivedit as seed or as plants from the Arnold Arboretum. Curiously, plants ofCarrierea were be<strong>in</strong>g offered as early as 1912 by the Daisy Hill Nurseryof Newry, Co. Down who described it <strong>in</strong> their catalogue as an evergreenshrub.

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 69Although, Wilson encountered this species on several earlier occasionsfor the Veitch Nursery, e.g. July 1903 (No. 3227) no precise locality;June 1904 (No. 4752) on Mt. Omei, Sichuan; and <strong>in</strong> western Hupeh(No. 1104) no precise locality or date; it is not recorded that he collectedother than herbarium specimens <strong>in</strong> flower. Plants presumably from thesame Wilson 1908 collection were subsequently grown by several othergardens <strong>in</strong> Brita<strong>in</strong> and Ireland although few appear to have flourished.In A Garden Flora, describ<strong>in</strong>g trees and flowers grown <strong>in</strong> the gardenat Nymans, Sussex, between 1890 and 1915, a note by Muriel Messell(1918) records, “so far the hard<strong>in</strong>ess of this tree, which Mr. Wilson<strong>in</strong>troduced from Ch<strong>in</strong>a, has not been proved. Our plants were raisedfrom Mr. Wilson’s seeds, and one small tree has been planted out ofdoors for three years on a north-east slope, where it seems at home.”Sadly, there is no record of this tree or any others grown from this seedat Nymans that have survived the test of time.A tree, that is thought to have been planted around 1919, still growsat Rowallane <strong>in</strong> Northern Ireland. Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the former Head Gardener,Michael Snowden, now retired, this tree which may have comefrom the Donard Nursery of Co. Down <strong>in</strong> 1919 or, alternatively, theDaisy Hill Nursery <strong>in</strong> the same county, was planted <strong>in</strong> an area known asHolly Rock outside the ma<strong>in</strong> garden and was neglected if not forgottenfor many years. It presently stands at 5.5m (28ft), its stem fork<strong>in</strong>gat 50cm (19<strong>in</strong>) above ground. It seems to have never flowered.Another tree recorded as grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Walled Garden at Rowallane<strong>in</strong> the 1920’s is no longer extant. The first mention of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a<strong>in</strong> the Gardener’s Chronicle appeared <strong>in</strong> the March 22 nd 1930 issuewhen F.E.G. Southampton, contributed a note <strong>in</strong> New or NoteworthyPlants. “It appears quite hardy <strong>in</strong> this country (Brita<strong>in</strong>), plants hav<strong>in</strong>gcome through the severe weather experienced dur<strong>in</strong>g the spr<strong>in</strong>g of 1928without suffer<strong>in</strong>g any apparent <strong>in</strong>jury.” He further added “Unfloweredtrees here, planted <strong>in</strong> a sheltered position on soil of a heavy, clayeynature have reached a height of 6ft (1.8m).” It was <strong>in</strong> the same year thatflower<strong>in</strong>g material from a tree grow<strong>in</strong>g at Tulgey Wood, Broadstone,Dorset was sent by a Mrs. Desborough to Kew to provide the illustra-

70tion for the Curtis Botanical Magaz<strong>in</strong>e entry which was not publisheduntil 1949.In autumn 1994 I received seed of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, PW 68, fromPeter Wharton. I gave the seed to the Surrey plantsman, Harry Haywho, apart from hav<strong>in</strong>g a noted garden and arboretum, has an uncannyskill at rais<strong>in</strong>g plants from seed or cutt<strong>in</strong>gs. Two years later, Harry returnedto me a tray of sturdy seedl<strong>in</strong>gs, which I potted on. One ofthese I planted <strong>in</strong> my garden whilst the rest were distributed to amongothers, Hergest Croft <strong>in</strong> Herefordshire, Abbotsbury Subtropical Gardens<strong>in</strong> Dorset, Dunloe Castle Hotel Gardens <strong>in</strong> Co. Kerry, Ireland andthe National Arboretum, Westonbirt, Gloucestershire.My plant settled <strong>in</strong> and began to put on growth. In May 2004, almost10 years after I received the seed, it produced its first flower buds fromthe tips of several shoots. A month later, these buds began to open andthe characteristic bell-shaped, greenish-cream, five-lobed downy calyx,2.5cm (0.98<strong>in</strong>) long, appeared. On exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g these flowers it was clearthat they were male as there was no discernable ovary present, just aconspicuous brush of cream-coloured stamens of vary<strong>in</strong>g length to 2cm(0.78<strong>in</strong>). The flowers lasted for less than 10 days before fall<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>tact.The same week, I took some cut specimens of the flower<strong>in</strong>g stems to ameet<strong>in</strong>g of The Garden Society held at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kewwhere, to my surprise, Maurice Foster produced flower<strong>in</strong>g specimens ofa tree from the same Peter Wharton collection grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> his garden <strong>in</strong>Kent. It was clear that the flowers of Maurice’s tree were female as theywere virtually no stamens present, only a downy ovary with a conspicuousflattened three-lobed stigma. The calyx <strong>in</strong> both sets of specimens,were a pale greenish-cream.On 6 th July 2004, I attended a gather<strong>in</strong>g at Nymans <strong>in</strong> Sussex to celebratethe 50 th anniversary of the National Trust’s stewardship of thoseGardens. I was once more surprised to f<strong>in</strong>d the lunch tables decoratedwith cut flower<strong>in</strong>g specimens of Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a provided by the Earlof Rosse from the Wilson tree at Birr Castle. It was clear that they weretoo, were female.In 2005 my tree did not flower but more than made up for this <strong>in</strong>2006 when it flowered abundantly (flowers all male) from late June <strong>in</strong>to

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 71early July. Even when <strong>in</strong> full flower, this tree is not an eye-catcher as thepale green flowers do not stand out enough aga<strong>in</strong>st the leaves to createthe necessary contrast. Fortunately, the foliage more than makes up forthis deficiency. The leaves are slightly pendulous so that their glossy darkgreen surface is well displayed on the wide-spread branches. Leaves onmy tree are from 20-33cm (9-13<strong>in</strong>) long, a third of which belongs tothe petiole. The blade varies from narrow elliptic to oblanceolate, up to7cm (2.75<strong>in</strong>) at the broadest, acum<strong>in</strong>ate tip, broad cuneate to rounded,sometimes obliquely so at the base, regularly toothed with blunt or pegliketeeth, each with a circular glandular pit beneath. They are glabrousexcept for the shortly downy petiole and tufts of hair <strong>in</strong> the ve<strong>in</strong> axilsbeneath, especially those of the lowermost ve<strong>in</strong>s. There is a small glandat the base of the blade either side of the petiole. When measured on13 th July 2006, this tree was 8m (20ft) tall with a girth at 1.5m (5ft) of27cm (10.5<strong>in</strong>). The lower branches are spread<strong>in</strong>g, the upper ascend<strong>in</strong>gthen spread<strong>in</strong>g, creat<strong>in</strong>g a loosely layered appearance.I have another specimen grown from the Wharton 1994 <strong>in</strong>troduction(PW 68) at Abbotsbury Subtropical Garden <strong>in</strong> Dorset. This hasgrown well and <strong>in</strong> June 2006 was approximately the same size as m<strong>in</strong>e.It has yet to flower. Another of the same <strong>in</strong>troduction planted <strong>in</strong> theWalled Garden at Dunloe Castle Hotel Garden was around 3m (10ft)<strong>in</strong> 2005. This has yet to flower. A tree seen <strong>in</strong> July 2006 grow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> thewalled garden of Pan Global Plants at Frampton-on-Severn near Stroud<strong>in</strong> Gloucestershire was 3 x 3m (10ft x 10ft) hav<strong>in</strong>g previously had its topblown out <strong>in</strong> a storm. It was received from the National Arboretum atWestonbirt as a seedl<strong>in</strong>g from the Peter Wharton 1994 collections (PW84). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the nursery owner Nick Macer, this tree flowered(all female) <strong>in</strong> 2004,. In July 2006 the flowers appeared to be develop<strong>in</strong>gfruits which suggests that they had been poll<strong>in</strong>ated. Short stamensor shriveled rema<strong>in</strong>s were present which po<strong>in</strong>ts to these flowers be<strong>in</strong>ghermaphroditic!Maurice Foster <strong>in</strong>formed me that his tree flowered aga<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> July 2006though not as prolifically as <strong>in</strong> 2004. Seed capsules were up to 3cm(1.75<strong>in</strong>) long, surrounded at their base by what look like the rema<strong>in</strong>s ofmany short stamens. One or two of the capsules conta<strong>in</strong>ed develop<strong>in</strong>g

<strong>Davidsonia</strong> 18:2 73ReferencesBean, W.J. 1976. Trees and Shrubs Hardy <strong>in</strong> the <strong>British</strong> Isles, 8th edition.Volume 1. London: John Murray.Cronk Q.C.B. 2005. Plant eco-devo: the potential of poplar as a model organism.New Phytologist 166: 39-48.Messel, M. 1918. In, A garden flora trees and flowers grown <strong>in</strong> the gardens atNymans 1890-1915. By L. Messel. With illustrations by Alfred Parsons.London: Country Life.Turrill, W.B. 1949. Carrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a Franch. Botanical Magaz<strong>in</strong>e N.S. 53: 1.Wilson, E.H. 1913. A Naturalist <strong>in</strong> Western Ch<strong>in</strong>a. London: Methuen & Co. p.239. New edition 1987. Everyman Publishers.Wilson, E.H. 1917. Plantae Wilsonianae 1:284 Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress.

Table of contentsEditorialTaylorThe North American flower<strong>in</strong>g of thecultivated founta<strong>in</strong> bamboo, Fargesia nitida(Poaceae: Bambusoideae), <strong>in</strong><strong>Vancouver</strong>, <strong>British</strong> <strong>Columbia</strong>, <strong>Canada</strong>SaarelaCarrierea calyc<strong>in</strong>a, goat horn tree - a two part accountof its history <strong>in</strong> western cultivationand recent re<strong>in</strong>troductionWharton and LancasterBook review.van WijkGlean<strong>in</strong>gs4143567476