Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Fieldwork and Linguistic Analysis in Indigenous ... - ScholarSpace

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

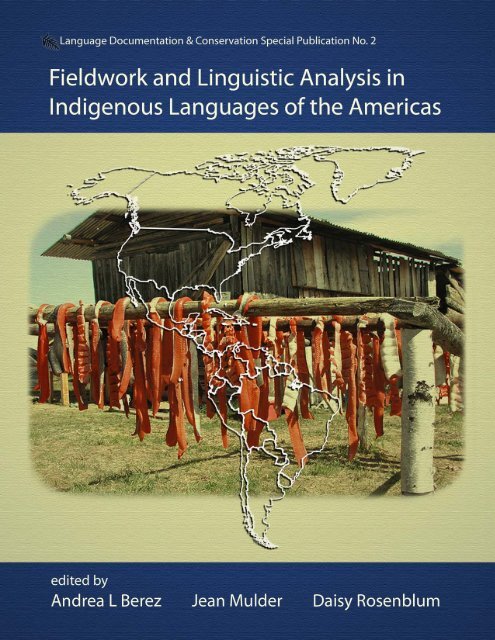

<strong>Fieldwork</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong><br />

<strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong><br />

Languages of the Americas<br />

edited by<br />

Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, <strong>and</strong><br />

Daisy Rosenblum<br />

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2

Published as a sPecial Publication of language documentation & conservation<br />

language documentation & conservation<br />

Department of <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s, UHM<br />

Moore Hall 569<br />

1890 East-West Road<br />

Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822<br />

USA<br />

http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc<br />

university of hawai‘i Press<br />

2840 Kolowalu Street<br />

Honolulu, Hawai‘i<br />

96822-1888<br />

USA<br />

© All texts <strong>and</strong> images are copyright to the respective authors. 2010<br />

All chapters are licensed under Creative Commons Licenses<br />

Cover design by Cameron Chrichton<br />

Cover photograph of salmon dry<strong>in</strong>g racks near Lime Village, Alaska, by Andrea L. Berez<br />

Library of Congress Catalog<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> Publication data<br />

ISBN 978-0-8248-3530-9<br />

http://hdl.h<strong>and</strong>le.net/10125/4463

Contents<br />

Foreword iii<br />

Marianne Mithun<br />

Contributors v<br />

Acknowledgments viii<br />

1. Introduction: The Boasian tradition <strong>and</strong> contemporary practice<br />

<strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork <strong>in</strong> the Americas<br />

Daisy Rosenblum <strong>and</strong> Andrea L. Berez<br />

2. Sociopragmatic <strong>in</strong>fluences on the development <strong>and</strong> use of the<br />

discourse marker vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Maya<br />

Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, <strong>and</strong> María Luz García<br />

3. Classify<strong>in</strong>g clitics <strong>in</strong> Sm’algyax:<br />

Approach<strong>in</strong>g theory from the field<br />

Jean Mulder <strong>and</strong> Holly Sellers<br />

4. Noun class <strong>and</strong> number <strong>in</strong> Kiowa-Tanoan: Comparative-historical<br />

research <strong>and</strong> respect<strong>in</strong>g speakers’ rights <strong>in</strong> fieldwork<br />

Logan Sutton<br />

5. The story of *o <strong>in</strong> the Cariban family<br />

Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, <strong>and</strong> Sérgio Meira<br />

6. Multiple functions, multiple techniques:<br />

The role of methodology <strong>in</strong> a study of Zapotec determ<strong>in</strong>ers<br />

Donna Fenton<br />

7. Middles <strong>and</strong> reflexives <strong>in</strong> Yucatec Maya:<br />

Trust<strong>in</strong>g speaker <strong>in</strong>tuition<br />

Israel Martínez Corripio <strong>and</strong> Ricardo Maldonado<br />

8. Study<strong>in</strong>g Dena’<strong>in</strong>a discourse markers:<br />

Evidence from elicitation <strong>and</strong> narrative<br />

Olga Charlotte Lovick<br />

9. Be careful what you throw out:<br />

Gem<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> tonal feet <strong>in</strong> Weledeh Dogrib<br />

Aless<strong>and</strong>ro Jaker<br />

10. Revisit<strong>in</strong>g the source:<br />

Non-f<strong>in</strong>ite verbs <strong>in</strong> Sierra Popoluca (Mixe-Zoque)<br />

Lynda Boudreault<br />

1<br />

9<br />

33<br />

57<br />

91<br />

125<br />

147<br />

173<br />

203<br />

223

Foreword<br />

This timely special publication represents a welcome stage <strong>in</strong> the development of the field<br />

of l<strong>in</strong>guistics. The discipl<strong>in</strong>e is witness<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>tertw<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of approaches to the study of<br />

language that have been evolv<strong>in</strong>g, often as <strong>in</strong>dependent str<strong>and</strong>s, for well over a century.<br />

Major progress has been made <strong>in</strong> all traditional doma<strong>in</strong>s: phonetics, phonology, morphology,<br />

syntax, semantics, <strong>and</strong> discourse. The importance of underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g how l<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

categories <strong>and</strong> structures emerge over time, how children acquire them, <strong>and</strong> how social<br />

<strong>and</strong> cultural uses shape them are now widely recognized. More is be<strong>in</strong>g learned every day<br />

about how language is utilized by speakers for social <strong>and</strong> cultural purposes. Technological<br />

<strong>and</strong> analytic advances have opened up possibilities for discoveries unimag<strong>in</strong>able at the<br />

outset, from f<strong>in</strong>e acoustic analysis to the manipulation of corpora. Theories are becom<strong>in</strong>g<br />

ever stronger, more detailed, <strong>and</strong> more sophisticated as we learn more about what occurs <strong>in</strong><br />

typologically diverse languages. This growth of knowledge has necessarily led to greater<br />

specialization on the part of <strong>in</strong>dividual researchers: there is simply too much for one person<br />

to master. At the same time, it is becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly clear that no aspect of language can<br />

be understood fully <strong>in</strong> isolation.<br />

There has been a palpable shift <strong>in</strong> attitudes with<strong>in</strong> the discipl<strong>in</strong>e, with greater respect<br />

among <strong>in</strong>dividual scholars for l<strong>in</strong>es of research outside of their own, <strong>and</strong> greater appreciation<br />

of the contributions each can make toward underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g others. Where once dist<strong>in</strong>ctions<br />

were sometimes drawn between ‘description’ <strong>and</strong> ‘theory’, there is now general<br />

recognition of the fact that the two are necessarily <strong>in</strong>terlock<strong>in</strong>g elements of an empiricallybased<br />

science. This recognition may have been stimulated, at least <strong>in</strong> part, by a heightened<br />

awareness of the immanent loss of l<strong>in</strong>guistic diversity <strong>in</strong> the world. Informed documentation<br />

<strong>and</strong> description of endangered languages has become a priority for the field, as one by<br />

one, languages are slipp<strong>in</strong>g away before our eyes <strong>and</strong> ears.<br />

The present collection is a f<strong>in</strong>e example of the evolution of the discipl<strong>in</strong>e, <strong>in</strong> particular<br />

the fad<strong>in</strong>g of impenetrable boundaries. It is now understood that good language<br />

documentation <strong>and</strong> description require a strong theoretical foundation, an underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g<br />

of what is currently known about language <strong>and</strong> at least some of the puzzles that rema<strong>in</strong>.<br />

All of the authors represented <strong>in</strong> this special publication br<strong>in</strong>g such a background to their<br />

fieldwork, <strong>and</strong> each of the articles makes an <strong>in</strong>cisive contribution to l<strong>in</strong>guistic theory. At<br />

the same time, it is now generally accepted that any theory of value must be grounded <strong>in</strong><br />

data. The papers collected here are exemplary <strong>in</strong> this regard. This volume represents the<br />

full range of structural doma<strong>in</strong>s, but each study also goes beyond the level of the specific<br />

patterns, markers, or constructions under consideration to exam<strong>in</strong>e the parts they play <strong>in</strong><br />

larger doma<strong>in</strong>s <strong>and</strong> their import for larger issues. There is work on the phonetic values of<br />

reconstructed vowels as revealed through modern fieldwork; on the tonal foot <strong>and</strong> the role<br />

of low-level allophonic processes <strong>in</strong> the construction of phonological categories; on prosodic,<br />

morphological, <strong>and</strong> syntactic properties of a range of grammatical <strong>and</strong> lexical clitics<br />

<strong>and</strong> their implications for a general theory of clitics; on the reconstruction of a complex<br />

system of number <strong>in</strong>flection based on noun class; on non-f<strong>in</strong>ite <strong>in</strong>flection, its <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

with argument structure, <strong>and</strong> its syntactic function; on the semantic thread of event construal<br />

l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g seem<strong>in</strong>gly disparate uses of the middle voice; on the spatial, temporal, <strong>and</strong><br />

discourse functions of determ<strong>in</strong>ers; <strong>and</strong> on the structural, pragmatic, <strong>and</strong> social functions<br />

of discourse markers.<br />

Licensed under Creative Commons<br />

Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License<br />

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 (May 2010):<br />

<strong>Fieldwork</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> Languages of the Americas,<br />

ed. by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, <strong>and</strong> Daisy Rosenblum, pp. iii-iv<br />

http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/<br />

http://hdl.h<strong>and</strong>le.net/10125/4462<br />

iii

Another fad<strong>in</strong>g boundary is that between academic l<strong>in</strong>guists on one side <strong>and</strong> members<br />

of language communities on the other. Work on <strong>in</strong>dividual languages, particularly<br />

those spoken by smaller populations <strong>and</strong> those <strong>in</strong> danger of disappearance, must be shaped<br />

not just by current l<strong>in</strong>guistic theory but equally if not more by the needs <strong>and</strong> desires of<br />

communities. Our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of l<strong>in</strong>guistic structure would be seriously impoverished<br />

without the dedication <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>sight of the speakers who collaborate <strong>in</strong> this work. More <strong>and</strong><br />

more community members are becom<strong>in</strong>g scholars. A recurr<strong>in</strong>g theme runn<strong>in</strong>g through this<br />

volume is the important <strong>in</strong>sights provided by speakers.<br />

The papers collected here also reflect a matur<strong>in</strong>g of methodology <strong>in</strong> the field. There<br />

are rich discussions of the <strong>in</strong>terplay between data <strong>and</strong> theory; between elicitation <strong>and</strong> unplanned<br />

spontaneous speech; between direct observation of speech <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>sights of<br />

speakers; between qualitative <strong>and</strong> quantitative f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs; between current data <strong>and</strong> analyses<br />

<strong>and</strong> earlier documentation <strong>and</strong> description. These threads have always been present <strong>in</strong> the<br />

discipl<strong>in</strong>e, but not necessarily with<strong>in</strong> the work of <strong>in</strong>dividual scholars. It has long been<br />

recognized that l<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong>cludes elements of hard science, of social science, <strong>and</strong> of the<br />

humanities. It has an empirical basis, with strict st<strong>and</strong>ards of responsibility to the data. It is<br />

a social phenomenon. It is also a human phenomenon, directly concerned with a product of<br />

the human m<strong>in</strong>d. The optimal methodologies for the study of language are not necessarily<br />

precisely the same as those for physics, mathematics, psychology, philosophy, or literature.<br />

In a sense we can see l<strong>in</strong>guistics com<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to its own as a discipl<strong>in</strong>e, with its own blend<br />

of methodologies. The present special publication provides a f<strong>in</strong>e example of this blend.<br />

Marianne Mithun<br />

iv

Contributors<br />

MELISSA AXELROD, who also specializes <strong>in</strong> Native American languages <strong>and</strong> language<br />

revitalization, is a professor <strong>in</strong> the <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s Department at the University of New<br />

Mexico. Together with Jule Gómez de García <strong>and</strong> María Luz García, she has been<br />

work<strong>in</strong>g with Ixil Maya speakers of the Grupo de Mujeres por la Paz of Nebaj, El<br />

Quiche, Guatemala, s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002 on NSF-funded projects to produce an electronic archive<br />

of l<strong>in</strong>guistic, cultural <strong>and</strong> historical materials <strong>and</strong>, most recently, a grammar of<br />

Ixil. Axelrod <strong>and</strong> Gómez de García have also collaborated on a language revitalization<br />

project with the Jicarilla Apache Nation <strong>in</strong> New Mexico <strong>and</strong> served as editors on the<br />

Dictionary of Jicarilla Apache (2007, Uiversity of New Mexico Press).<br />

ANDREA L. BEREZ is a doctoral c<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> the l<strong>in</strong>guistics department at the University<br />

of California, Santa Barbara. She is a descriptive <strong>and</strong> documentary l<strong>in</strong>guist who works<br />

primarily with speakers of Ahtna <strong>and</strong> Dena’<strong>in</strong>a, two endangered Athabascan languages<br />

of southcentral Alaska. Her l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude <strong>in</strong>tonation, spatial cognition <strong>and</strong><br />

discourse-functional approaches to grammar. She is also <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> the development<br />

of the technological <strong>in</strong>frastructure to support language documentation <strong>and</strong> archiv<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

LYNDA DE JONG BOUDREAULT graduated from the University of Texas at Aust<strong>in</strong><br />

where she specialized <strong>in</strong> descriptive l<strong>in</strong>guistics with particular <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> languages of<br />

Mesoamerica. Her research experience <strong>in</strong>cludes work on Iquito, a Zaparoan language<br />

spoken by about 26 people <strong>in</strong> the northern Peruvian Amazon, <strong>and</strong> Sierra Popoluca (also<br />

known as Soteapanec), spoken <strong>in</strong> the southern part of the State of Veracruz, Mexico. In<br />

addition to documentary work, Dr. Boudreault is <strong>in</strong>terested <strong>in</strong> pedagogy <strong>and</strong> issues of<br />

language revitalization <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance.<br />

ISRAEL MARTÍNEZ CORRIPIO is a graduate student at the Universidad Nacional<br />

Autónoma de México. His ma<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude voice systems <strong>and</strong> argument structure<br />

<strong>in</strong> Mayan languages.<br />

DONNA FENTON studied l<strong>in</strong>guistics at San Francisco State University <strong>and</strong> UC Berkeley.<br />

Her ma<strong>in</strong> research <strong>in</strong>terests are language documentation <strong>and</strong> revitalization, <strong>and</strong> Mesoamerican<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistics.<br />

MARÍA LUZ GARCÍA is a doctoral c<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic anthropology at The University<br />

of Texas at Aust<strong>in</strong>. Her focus of study is on the use of the Ixil language <strong>in</strong> creat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

public collectives. She has been work<strong>in</strong>g with Ixil organizations such as the Grupos<br />

de Mujeres y Hombres por la Paz, the Comunidades de Población en Resistencia, <strong>and</strong><br />

community leaders <strong>in</strong>volved <strong>in</strong> exhumation <strong>and</strong> reburial of victims of the genocide of<br />

Mayas of the 1980s. She has collaborated with Gómez de García <strong>and</strong> Axelrod on documentation<br />

of the Ixil language s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002.<br />

SPIKE GILDEA is an associate professor of l<strong>in</strong>guistics at the University of Oregon. His<br />

research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude fieldwork <strong>and</strong> descriptive l<strong>in</strong>guistics of South America, historical<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistics of the Cariban family, grammaticalization, <strong>and</strong> typological/functional<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistics. He has collected primary l<strong>in</strong>guistic data from speakers of thirteen Cariban<br />

v

languages: Akawaio (Kapóng), Akuriyó, Apalaí, Arekuna (Pemón), Ikpéng, Hixkaryana,<br />

Katxúyana, Makushi, Panare, Patamuna (Kapóng), Tiriyó, Waiwai, Wayana, Xikuyana<br />

(Katxúyana), <strong>and</strong> Yukpa.<br />

JULE GÓMEZ DE GARCÍA is a professor of l<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong> the Liberal Studies Department<br />

at California State University San Marcos <strong>and</strong> a specialist <strong>in</strong> Native American<br />

languages. She has worked on documentation of the Kickapoo <strong>and</strong> Jicarilla Apache<br />

languages <strong>and</strong> is a co-editor on a dictionary of Jicarilla Apache published by University<br />

of New Mexico Press <strong>in</strong> 2007. With María Luz García, Melissa Axelrod, <strong>and</strong> the Grupo<br />

de Mujeres por la Paz, she has worked on documentation of the Ixil Maya language<br />

s<strong>in</strong>ce 2002. The team is currently collaborat<strong>in</strong>g on the production of a grammar of the<br />

Nebaj dialect of Ixil, a project funded by the NSF.<br />

BEREND HOFF is a visit<strong>in</strong>g lecturer at Leiden University. He has been engaged <strong>in</strong> describ<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the grammar of the Carib language (Kari’nja) s<strong>in</strong>ce the 1950s, <strong>and</strong> he also<br />

studies language contact, especially the case of Isl<strong>and</strong> Carib.<br />

ALESSANDRO JAKER is a graduate student <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistics at Stanford University. His<br />

primary <strong>in</strong>terests are phonetics, phonology, <strong>and</strong> morphological typology. Recently, his<br />

empirical work has been focused on Athabaskan languages, <strong>in</strong> particular the dialects<br />

of Dogrib <strong>and</strong> Chipewyan spoken <strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> around Yellowknife, Northwest Territories.<br />

His dissertation work centers on the prosodic phonology of Dogrib, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>teraction<br />

between verb morphology <strong>and</strong> the prosody of Dogrib verbs.<br />

OLGA CHARLOTTE LOVICK studies Northern Athabascan languages, <strong>in</strong> particular<br />

Dena’<strong>in</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Upper Tanana, both spoken <strong>in</strong> Alaska. Her ma<strong>in</strong> research <strong>in</strong>terest lies <strong>in</strong><br />

the study of discourse, <strong>in</strong> particular the study of discourse markers <strong>and</strong> other particles,<br />

<strong>and</strong> the study of prosody <strong>in</strong> narrative. Current projects <strong>in</strong>clude a bil<strong>in</strong>gual collection of<br />

narratives <strong>in</strong> the Tetl<strong>in</strong> dialect of Upper Tanana as well as a first foray <strong>in</strong>to the prosody<br />

of conversation. Olga received both her Magister <strong>and</strong> her Ph.D. <strong>in</strong> General <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s<br />

from the Universität zu Köln, Germany. Prior to her current position as Assistant Professor<br />

at the First Nations University of Canada, she was a Postdoctoral Fellow at the<br />

Alaska Native Language Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks.<br />

RICARDO MALDONADO is a professor at The Universidad Nacional Autónoma de<br />

México <strong>and</strong> he is a guest professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Mexico.<br />

His research <strong>in</strong>terests center on the relationship between language <strong>and</strong> cognition with<br />

special focus on voice systems, possession <strong>and</strong> datives of Spanish <strong>and</strong> Mexican <strong>in</strong>digenous<br />

languages.<br />

SÉRGIO MEIRA is a lecturer <strong>in</strong> American Indian l<strong>in</strong>guistics as Leiden University’s Centre<br />

for <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s. His research focuses on historical l<strong>in</strong>guistics, fieldwork <strong>and</strong> description<br />

of the Cariban <strong>and</strong> Tupían language families, as well as language <strong>and</strong> cognition. He<br />

has collected primary l<strong>in</strong>guistic data from speakers of 14 Cariban languages: Akawaio,<br />

vi

Akuriyó, Apalaí, Bakairi, Hixkaryana, Karihona, Kari’nja, Katxúyana, Kuhikuru,<br />

Makushi, Tiriyó, Waiwai, Wayana, <strong>and</strong> Yukpa.<br />

JEAN MULDER is a senior lecturer <strong>in</strong> the School of Languages <strong>and</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s at the<br />

University of Melbourne. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests range over language documentation,<br />

grammatical <strong>and</strong> discourse analysis, m<strong>in</strong>ority language education, <strong>and</strong> educational l<strong>in</strong>guistics<br />

with fieldwork on a variety of languages. She began her study of Sm’algyax<br />

by work<strong>in</strong>g for five years full time <strong>in</strong> the field develop<strong>in</strong>g the Sm’algyax Language<br />

Studies Program <strong>in</strong> School District No. 52 (British Columbia). She completed her PhD<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s at the University of California, Los Angeles <strong>and</strong>, prior to her current position,<br />

she taught at the University of Victoria, Simon Fraser University, the University<br />

of Alberta, <strong>and</strong> the University of Swazil<strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> southern Africa.<br />

DAISY ROSENBLUM is a doctoral student <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistics at the University of California,<br />

Santa Barbara. Her work focuses on the documentation <strong>and</strong> description of American<br />

<strong>in</strong>digenous languages <strong>in</strong> the Mayan <strong>and</strong> Wakashan families, with an emphasis on the<br />

study of multi-modal <strong>in</strong>teraction. Her research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude prosody, argument<br />

structure, deixis, <strong>and</strong> grammars of space <strong>and</strong> time, <strong>and</strong> the <strong>in</strong>teractions among them.<br />

She is currently work<strong>in</strong>g with members of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation <strong>in</strong> British Columbia<br />

to record, transcribe <strong>and</strong> analyze multiple genres of spontaneous speech <strong>in</strong> three<br />

dialects of Kwak’wala.<br />

HOLLY SELLERS completed a BA (Honors) <strong>in</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s at the University of Melbourne.<br />

She has an <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> syntax as well as undocumented languages. She has<br />

worked on data from the Native American language of Sm’algyax from the British Columbia<br />

region <strong>in</strong> Canada as well as first h<strong>and</strong> documentation of the Ganalbiŋu language<br />

of Northern Australia.<br />

LOGAN SUTTON is a Ph.D. c<strong>and</strong>idate <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistics at the University of New Mexico<br />

<strong>and</strong> works for the American Indian Studies Research Institute at Indiana University.<br />

He received his B.A. <strong>in</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistics from Indiana University <strong>in</strong> 2004 <strong>and</strong> his M.A. <strong>in</strong><br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistics from the same school <strong>in</strong> 2006. His primary research <strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong>clude synchronic<br />

<strong>and</strong> diachronic analysis <strong>and</strong> description of the Kiowa-Tanoan <strong>and</strong> Caddoan<br />

language families <strong>and</strong> language revitalization among Native American communities<br />

<strong>in</strong> the Southwest. He is currently work<strong>in</strong>g alongside Professor Melissa Axelrod <strong>and</strong><br />

other graduate students at UNM <strong>in</strong> collaboration with members of Pueblo communities<br />

towards develop<strong>in</strong>g material for language revitalization <strong>and</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>tenance.<br />

vii

Acknowledgments<br />

The editors are deeply grateful to the follow<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividuals who have contributed to the<br />

success of this publication: Marianne Mithun, Anthony Aristar, Helen Aristar-Dry, Paul<br />

Newman, Roxana Ma Newman, <strong>and</strong> Martha Ratliff (for their procedural guidance); Stefan<br />

Th. Gries (for encourag<strong>in</strong>g the project <strong>in</strong> the first place); Michal Brody, Matthew Gordon,<br />

Salomé Gutiérrez Morales, Gary Holton, Cara Penry Williams, <strong>and</strong> S<strong>and</strong>ra Thompson (for<br />

shar<strong>in</strong>g their expertise on the contents); Cameron Crichton <strong>and</strong> Holly Sellers (for their<br />

design skills); <strong>and</strong> Lea Harper, Timothy J.P. Henry, Carmen Jany, Joye Kiester, Verónica<br />

Muñoz Ledo, Carlos Nash, Elizabeth Shipley, Rebekka Siemens, <strong>and</strong> Alex Walker (for<br />

be<strong>in</strong>g all-around good colleagues).<br />

viii

1<br />

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 (May 2010):<br />

<strong>Fieldwork</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> Languages of the Americas,<br />

ed. by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, <strong>and</strong> Daisy Rosenblum, pp. 1-8<br />

http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/<br />

http://hdl.h<strong>and</strong>le.net/10125/4448<br />

Introduction: The Boasian tradition<br />

<strong>and</strong> contemporary practice <strong>in</strong><br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork <strong>in</strong> the Americas<br />

Daisy Rosenblum <strong>and</strong> Andrea L. Berez<br />

University of California, Santa Barbara<br />

The papers collected <strong>in</strong> this volume represent a cross-section of current l<strong>in</strong>guistic scholarship<br />

<strong>in</strong> which authors share a common methodology: the analyses presented here have<br />

emerged directly from the challenges <strong>and</strong> felicities of l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork <strong>and</strong> language<br />

documentation. We take fieldwork to be the study of a language—often not the researchers’<br />

own, <strong>and</strong> frequently conducted on site where the language is spoken—as a holistic system,<br />

operat<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>terdependent social, cultural, <strong>and</strong> historical contexts. While each contributor<br />

<strong>in</strong> these pages has narrowed his or her focus to one small corner of that system, the<br />

work here is <strong>in</strong>formed by attention to the larger contexts of these languages, situated <strong>in</strong> the<br />

communities <strong>in</strong> which they are spoken, <strong>and</strong> of field l<strong>in</strong>guistics as a discipl<strong>in</strong>e, situated <strong>in</strong><br />

the community <strong>in</strong> which it is practiced.<br />

The languages considered here are all <strong>in</strong>digenous to the Americas. Measured <strong>in</strong> degrees<br />

of latitude, they span nearly half the globe, from Alaska <strong>and</strong> the Northwest Territories<br />

<strong>in</strong> the north to Brazil <strong>in</strong> the south. The tradition of fieldwork <strong>in</strong> American l<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong><br />

particular <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> American anthropology more generally was established <strong>in</strong> large part by<br />

Franz Boas <strong>in</strong> the early twentieth century. Boas <strong>and</strong> his students, with Edward Sapir foremost<br />

among them, located fieldwork as the fundamental method for elucidat<strong>in</strong>g universals<br />

<strong>and</strong> variation <strong>in</strong> language. For even the earliest fieldworkers, gather<strong>in</strong>g data <strong>in</strong> the field<br />

required collaboration with native speakers, the collection of diverse genres of data us<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

multiplicity of methods, <strong>and</strong> patience with the unfold<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> sometimes chaotic nature of<br />

data gathered <strong>in</strong> the field. In the century s<strong>in</strong>ce Boas conducted his iconic field trips to North<br />

America’s Northwest Coast, generations of Americanist l<strong>in</strong>guists have carried forward this<br />

legacy, <strong>and</strong> the fifteen authors <strong>in</strong> the present publication carry forth this tradition. The<br />

articles coalesce around these same themes of community collaboration, attendance to a<br />

wide range of data types <strong>and</strong> methods, <strong>and</strong> the slowly unfold<strong>in</strong>g nature of the process. Each<br />

paper highlights the methodological <strong>and</strong> theoretical contributions field-based l<strong>in</strong>guistic research<br />

has made to our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of grammatical structure <strong>in</strong> American languages, <strong>and</strong><br />

to the broader theoretical objectives of the discipl<strong>in</strong>e as a whole. To paraphrase Jean Mulder<br />

<strong>and</strong> Holly Sellers (chapter 3), contemporary l<strong>in</strong>guistic theories can give <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to the<br />

underly<strong>in</strong>g structure of field-collected language data <strong>in</strong> typological context, <strong>and</strong> the data<br />

themselves afford empirical means of test<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g our theories.<br />

Licensed under Creative Commons<br />

Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike License

Introduction 2<br />

COMMUNITY COLLABORATION<br />

A general review of our ethnographic literature shows clearly how much better<br />

is the <strong>in</strong>formation obta<strong>in</strong>ed by observers who have comm<strong>and</strong> of the language,<br />

<strong>and</strong> who are on terms of <strong>in</strong>timate friendship with the natives, than that obta<strong>in</strong>ed<br />

through the medium of <strong>in</strong>terpreters. (Boas 1911 [1966, 1991]:57)<br />

A common start<strong>in</strong>g po<strong>in</strong>t for a field l<strong>in</strong>guist is a mutually beneficial relationship with the<br />

community of speakers with whom one is to work; whether a l<strong>in</strong>guist is a member of the<br />

speaker community or a guest, a reciprocal <strong>and</strong> collaborative alliance is crucial to success.<br />

An exchange of skills <strong>and</strong> expertise between speakers <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guists has been <strong>in</strong>tegral to<br />

successful long-term fieldwork relationships s<strong>in</strong>ce Boas collaborated with George Hunt to<br />

transcribe Kwak’wala (Kwakiutl) texts <strong>and</strong> produce ethnographies of Kwakwaka’wakw<br />

communities. Many fieldworkers see this type of exchange as a way of giv<strong>in</strong>g back to<br />

speakers who are shar<strong>in</strong>g their l<strong>in</strong>guistic <strong>and</strong> cultural knowledge.<br />

However, a collaborative relationship between speakers <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guists is more than<br />

merely responsible procedure; it produces better data <strong>and</strong> can illum<strong>in</strong>ate patterns otherwise<br />

<strong>in</strong>accessible to researchers. In her 2001 essay reflect<strong>in</strong>g on the roles of speakers <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guists<br />

<strong>in</strong> language documentation, Mithun observes that<br />

[i]n many ways, the more the speaker is <strong>in</strong>vited to shape the record, the richer<br />

the documentation of the language, <strong>and</strong> the more we will learn about the extent<br />

to which languages can vary … If speakers are allowed to speak for themselves,<br />

creat<strong>in</strong>g a record of spontaneous speech <strong>in</strong> natural communicative sett<strong>in</strong>gs, we<br />

have a better chance of provid<strong>in</strong>g the k<strong>in</strong>d of record that will be useful to future<br />

generations. (Mithun 2001:51-3)<br />

Several of the papers <strong>in</strong> this publication address how such relationships are established<br />

<strong>and</strong> negotiated, as well as the benefits to research, analysis, <strong>and</strong> theory deriv<strong>in</strong>g from close<br />

collaboration with speakers.<br />

Jule Gómez de García, Melissa Axelrod, <strong>and</strong> Maria Luz García (chapter 2) present<br />

their analysis of the development <strong>and</strong> use of an Ixil Maya discourse particle aga<strong>in</strong>st the<br />

backdrop of six years of collaboration with a women’s weav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> agricultural cooperative<br />

<strong>in</strong> Guatemala. It is the dynamic of the group itself <strong>and</strong> the women’s metatextual<br />

conversations about language work that generated the analysis presented here. In the midst<br />

of transcription session discussions, the event-sequenc<strong>in</strong>g function of the particle came to<br />

light as members of the group, unaccustomed to the picture book stimulus, realize the sequentiality<br />

of Pancakes for Breakfast <strong>and</strong> Frog, Where Are You?. “One of the most relevant<br />

facts of our fieldwork <strong>in</strong> Nebaj is the vary<strong>in</strong>g levels of literacy skills among the women<br />

<strong>and</strong> the correspondence of those skills with the differentials <strong>in</strong> experience the women have<br />

had with pr<strong>in</strong>ted materials. This fact has determ<strong>in</strong>ed how transcription <strong>and</strong> elicitation sessions<br />

will be arranged <strong>and</strong> now it is clear that it is also a factor <strong>in</strong> shap<strong>in</strong>g how, <strong>and</strong> how<br />

frequently, the discourse marker vet is used by the women <strong>in</strong> their speech” (p. 29).<br />

In turn, Jean Mulder <strong>and</strong> Holly Sellers’s paper on classify<strong>in</strong>g the uncommonly wide<br />

range of clitics found <strong>in</strong> Sm’algyax (Coast Tsimshian; chapter 3) shows how Anderson’s<br />

2005 constra<strong>in</strong>t-based account of clitics provides a framework for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g the com-<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 3<br />

plex behavior of Sm’algyax clitics. In addition, the Sm’algyax clitics provide <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to<br />

the applicability of the theory. Many of the examples cited come from texts that have been<br />

pa<strong>in</strong>stak<strong>in</strong>gly edited by a collective of Sm’algyax speakers <strong>and</strong> writers. “This is a case<br />

where not only does l<strong>in</strong>guistic theory help sharpen our underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g of fieldwork data,<br />

but also where field l<strong>in</strong>guistics has consequences for l<strong>in</strong>guistic theory,” they write, “…<br />

[t]he motivation for approach<strong>in</strong>g fieldwork <strong>and</strong> theoretical l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> this way<br />

is to work toward enabl<strong>in</strong>g knowledge of the language to be constructed not only for <strong>and</strong><br />

with, but also by community-members” (p. 34-35).<br />

Logan Sutton (chapter 4) tackles the role of collaborative fieldwork <strong>in</strong> historical <strong>and</strong><br />

comparative l<strong>in</strong>guistics <strong>in</strong> his reconstruction of noun class <strong>and</strong> number <strong>in</strong> Kiowa-Tanoan<br />

languages. At the same time he acknowledges the duty field l<strong>in</strong>guists have toward respect<strong>in</strong>g<br />

a language community’s desire for privacy. Pueblo communities have a long history<br />

of protect<strong>in</strong>g certa<strong>in</strong> aspects of culture <strong>and</strong> tradition, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g language, from academic<br />

research by outsiders. Sutton, whose research <strong>in</strong>volves collaboration with several Native<br />

American communities of the southwest United States, justifiably limits his historical<br />

analysis here to data already <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>t. He writes that <strong>in</strong> a publication about the relationship<br />

between fieldwork <strong>and</strong> analysis, it may “be surpris<strong>in</strong>g that I base the hypothesis <strong>and</strong> the<br />

conclusions of this paper on data collected by somebody else. … However, with all the<br />

virtues of fieldwork—<strong>in</strong>deed, most l<strong>in</strong>guistic work is ultimately ow<strong>in</strong>g to native speakers<br />

shar<strong>in</strong>g their languages—there are restrictions that must be recognized <strong>and</strong> respected”<br />

(p. 58). The sensitive <strong>and</strong> often emotionally-charged issue of privacy is a daily reality for<br />

many language workers <strong>in</strong> the Americas <strong>and</strong> elsewhere.<br />

A DIVERSITY OF RESOURCES<br />

To plumb the depths of a language, all sources are of value—elicitation, texts,<br />

casual speech, stories, <strong>and</strong> conversations … diversity must be allowed to suffuse<br />

fieldwork. (Rice 2001:240-1)<br />

When l<strong>in</strong>guists go to the field to gather data, the k<strong>in</strong>ds of data they collect, the manner<br />

<strong>in</strong> which they are collected, <strong>and</strong> the way <strong>in</strong> which these data are processed are primary<br />

considerations with far-reach<strong>in</strong>g theoretical implications. <strong>Fieldwork</strong>ers must decide when<br />

to collect data through elicitation or record<strong>in</strong>g of spontaneous discourse; what paradigms,<br />

texts, <strong>and</strong> lexica they seek; which orthography or orthographies they will choose for transcriptions,<br />

<strong>and</strong> whether record<strong>in</strong>gs are edited or left <strong>in</strong> their orig<strong>in</strong>al state. A diversified approach<br />

to l<strong>in</strong>guistic data, <strong>and</strong> faith <strong>in</strong> the long-term theoretical promise of such data, is also<br />

part of the Americanist tradition. Mithun po<strong>in</strong>ts out that <strong>in</strong> addition to direct elicitation, “[a]<br />

second k<strong>in</strong>d of methodology, the record<strong>in</strong>g of connected speech, formed the core of much<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork over the past century, particularly <strong>in</strong> North America. The tradition of<br />

text collection arose <strong>in</strong> part from a desire to document the rich cultures of the speakers,<br />

but it was also seen as a tool for underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g languages <strong>in</strong> their own terms, rather than<br />

through European models. The texts served as the basis for grammatical description” (Mithun<br />

2001:35). She quotes Boas’ <strong>in</strong>troduction to the <strong>in</strong>augural volume of the International<br />

Journal of American <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s, <strong>in</strong> which he presents a m<strong>and</strong>ate for a new era <strong>in</strong> the study<br />

of American languages <strong>and</strong> language <strong>in</strong> general: “While until about 1880 <strong>in</strong>vestigators<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 4<br />

conf<strong>in</strong>ed themselves to the collection of vocabularies <strong>and</strong> brief grammatical notes, it has<br />

become more <strong>and</strong> more evident that large masses of texts are needed <strong>in</strong> order to elucidate<br />

the structure of the languages” (Boas 1917:1, quoted <strong>in</strong> Mithun 2001:35).<br />

Several papers here address the value of collect<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> draw<strong>in</strong>g on a diversity of resources,<br />

from legacy materials <strong>in</strong> (<strong>and</strong> out of) archives to newly recorded speech, <strong>and</strong> the<br />

importance of br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g fresh <strong>in</strong>terpretation to the data <strong>and</strong> theories we may <strong>in</strong>herit from<br />

others. The chapter by Spike Gildea, B.J. Hoff, <strong>and</strong> Sérgio Meira (chapter 5) is also a historical<br />

reconstruction, this time of the proto-vowel ô <strong>in</strong> Cariban languages. Here, however,<br />

the focus is on how the modern collection of reliable field data can help answer questions<br />

rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the fieldnotes of our academic predecessors. Special attention is paid to how<br />

modern l<strong>in</strong>guists can benefit from the <strong>in</strong>terven<strong>in</strong>g years of professional <strong>and</strong> methodological<br />

growth the field has seen s<strong>in</strong>ce the early days of documentary work. “Early sources of<br />

data from Cariban languages were vexed with poor transcription, especially of vowels. As<br />

a result, early attempts to compare Cariban wordlists resulted <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>consistent correspondences.<br />

In our own fieldwork, we have found that old word lists are rarely confirmed by<br />

our modern transcriptions” (p. 93). “This paper illustrates the importance of good modern<br />

fieldwork <strong>in</strong> two ways: first, after collect<strong>in</strong>g reliable modern data, many <strong>in</strong>consistencies <strong>in</strong><br />

cognate sets disappear <strong>and</strong> previously unseen patterns become clear; second, reliable modern<br />

data can provide <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to previously opaque transcription systems used by older<br />

sources, thereby enabl<strong>in</strong>g us to make better use of language data recorded several hundred<br />

years ago” (p. 92).<br />

The importance of look<strong>in</strong>g to a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of connected spontaneous speech <strong>and</strong><br />

elicited data is addressed by Fenton, Lovick, <strong>and</strong> others, <strong>in</strong> particular the way <strong>in</strong> which<br />

multiple types of data exam<strong>in</strong>ed together can illum<strong>in</strong>ate the rich complexity of a l<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

system. Olga Charlotte Lovick builds on the vast body of work on clause-level syntax <strong>in</strong><br />

Athabaskan languages <strong>in</strong> her analysis of several discourse markers <strong>in</strong> Dena’<strong>in</strong>a (chapter 8).<br />

She <strong>in</strong>vokes a range of data sources—e.g., fieldnotes <strong>and</strong> texts she has collected <strong>and</strong> those<br />

collected by her predecessors—<strong>and</strong> methods to uncover the functions of particles that, accord<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to speakers, “‘have no mean<strong>in</strong>g’ or ‘mean someth<strong>in</strong>g else <strong>in</strong> every sentence’” (p.<br />

174). The difficulty of p<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g down the functions of discourse particles before lexical <strong>and</strong><br />

syntactic analyses are available is clear from the fieldnotes of previous researchers Lovick<br />

consulted, which are teem<strong>in</strong>g with particles that are either variably glossed or not glossed<br />

at all. In her chapter, Lovick advocates a flexible approach for reveal<strong>in</strong>g the connective <strong>and</strong><br />

cohesive functions of each of the particles she exam<strong>in</strong>es, <strong>and</strong> allows both direct elicitation<br />

<strong>and</strong> analysis of narrative to be her guide. “To def<strong>in</strong>e the mean<strong>in</strong>g of one of these discourse<br />

markers, simple elicitation is not sufficient … Direct question<strong>in</strong>g about the mean<strong>in</strong>g of the<br />

particles considered here may or may not yield a useful answer” (p. 174). She cont<strong>in</strong>ues,<br />

“only discourse analysis can show that [the particles] have different functions correspond<strong>in</strong>g<br />

to their position with<strong>in</strong> a narrative unit” (p. 174).<br />

In their chapter on middles <strong>and</strong> reflexives <strong>in</strong> Yucatec Maya (chapter 7), Israel Martínez<br />

Corripio <strong>and</strong> Ricardo Maldonado also advocate a multi-pronged approach to fieldworkbased<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g elicitation, text analysis, <strong>and</strong>, most importantly here,<br />

heed<strong>in</strong>g speaker <strong>in</strong>tuition as a clue to the semantic features of the constructions under<br />

<strong>in</strong>vestigation. Despite the seem<strong>in</strong>gly arbitrary distribution of middles <strong>and</strong> reflexives <strong>in</strong> Yucatec<br />

Maya, the authors show that middles are limited to absolute events (i.e., those <strong>in</strong><br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 5<br />

which no energy is expended), a typologically unusual motivation among languages with<br />

middle systems. An essential component of their methodology was the <strong>in</strong>corporation of<br />

speaker <strong>in</strong>tuition <strong>in</strong> the analytic process: “[o]ur data collection began with direct elicitation<br />

<strong>and</strong> the analysis of oral narrative, but these—whether alone or considered together—were<br />

not sufficient to fully illum<strong>in</strong>ate the behavior of the YM middle system. As our analysis<br />

grew, we found it necessary to <strong>in</strong>vent ways to <strong>in</strong>vestigate speaker <strong>in</strong>tuition as well” (p.<br />

148). By trust<strong>in</strong>g speakers’ <strong>in</strong>tuitions about subtle semantic differences between hypothetical<br />

language-use situations, Martínez Corripio <strong>and</strong> Maldonado are able to illum<strong>in</strong>ate<br />

<strong>and</strong> confirm a coherent semantic doma<strong>in</strong> govern<strong>in</strong>g the use of middles <strong>and</strong> reflexives <strong>in</strong><br />

Yucatec.<br />

Another paper highlight<strong>in</strong>g the role of multiple methodologies <strong>in</strong> fieldwork is Donna<br />

Fenton’s study of determ<strong>in</strong>ers <strong>in</strong> Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec (chapter 6). The determ<strong>in</strong>ers<br />

have a number of temporal, discourse <strong>and</strong> spatial functions, the details of which only<br />

became apparent through text analysis <strong>and</strong> elicitation, each method reveal<strong>in</strong>g a different<br />

set of subtleties of use. “The texts, which ow<strong>in</strong>g to the circumstances of my work <strong>in</strong> Teotitlán<br />

del Valle were collected <strong>and</strong> transcribed <strong>in</strong> the early stages of the research, revealed<br />

temporal <strong>and</strong> discourse functions of the determ<strong>in</strong>ers. Elicitation, which was <strong>in</strong>formed by<br />

the analysis of the texts, brought out the expected spatial dist<strong>in</strong>ctions <strong>and</strong> enabled me to<br />

ref<strong>in</strong>e my analysis of the temporal extensions of the determ<strong>in</strong>ers. Neither method on its<br />

own would have provided a complete picture, <strong>and</strong> it is possible that the ‘backwards’ order<br />

of data collection allowed for a better <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to how speakers actually used <strong>and</strong> thought<br />

about the system of determ<strong>in</strong>ers” (p. 126).<br />

Importantly, as noted by Mithun, a multiplicity of approaches will “permit … us to<br />

notice dist<strong>in</strong>ctions <strong>and</strong> patterns that we might not know enough to elicit … this material<br />

is <strong>in</strong> many ways the most important <strong>and</strong> excit<strong>in</strong>g of all. <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> theory will never be<br />

moved ahead as far by answers to questions we already know enough to ask as it will by<br />

discoveries of the unexpected” (Mithun 2001:45). As our work as l<strong>in</strong>guists now f<strong>in</strong>ds application<br />

among communities eager to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> <strong>and</strong> revitalize their languages, the need for<br />

a diversity of data is especially press<strong>in</strong>g.<br />

EVOLUTION OF THE ANALYSIS<br />

Fort Rupert, September 22, 1886<br />

The material overwhelms me. I am very curious about the story I am to get today.<br />

Each day br<strong>in</strong>gs so much that is new <strong>and</strong> so many surprises. (Boas, <strong>in</strong> a letter to<br />

his parents, from Rohner 1969:24)<br />

Ladners L<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g, August 17, 1890<br />

With what I am gett<strong>in</strong>g now <strong>and</strong> what I got before, I can see that I have learned a<br />

great deal. Much of the confused knowledge I had then is be<strong>in</strong>g straightened out<br />

now. (Boas, <strong>in</strong> a letter to his wife, from Rohner 1969:65)<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 6<br />

Often, what turns out to be the most valuable data may only reveal itself as such after the<br />

fieldtrip is over <strong>and</strong> the researcher has returned home. This revelation may eventually lead<br />

to another trip to the field—<strong>and</strong> another. In all cases, though, data gathered through fieldwork<br />

is chaotic, messy <strong>and</strong> full of surprises. Underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>g it may happen only slowly or <strong>in</strong><br />

fits <strong>and</strong> starts, often over multiple field seasons. This facet of l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork requires<br />

patience, curiosity, flexibility, <strong>and</strong> a focus on the process of discovery.<br />

In many of the essays gathered here, like Fenton’s analysis of Zapotec determ<strong>in</strong>ers<br />

discussed above, the analysis evolved over time through multiple visits to the field site.<br />

This theme is also present <strong>in</strong> Lynda Boudreault’s description of dependent verbs <strong>in</strong> Sierra<br />

Popoluca (chapter 10). The author describes dependent verbs <strong>in</strong> the language <strong>and</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>es<br />

the particular constructions <strong>in</strong> which they appear. The analysis presented here began<br />

with a careful look at previous work <strong>and</strong> developed by means of recurrent text transcription<br />

<strong>and</strong> elicitation that took place over multiple fieldtrips between 2004 <strong>and</strong> 2007. It is<br />

the <strong>in</strong>herently cyclical nature of field-based l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis that Boudreault highlights:<br />

“text transcription, data m<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, post-hoc analysis, <strong>and</strong> controlled elicitation … is a cyclic<br />

process that looks to data to corroborate predictions driven by l<strong>in</strong>guistic theory <strong>and</strong> that <strong>in</strong><br />

turn bear on theory” (p. 256). Her goal here is to show “the <strong>in</strong>terdependent processes of<br />

data collection <strong>and</strong> analysis by address<strong>in</strong>g how different observations emerge at different<br />

stages of the analysis” (p. 226).<br />

Aless<strong>and</strong>ro Jaker, <strong>in</strong> his paper on gem<strong>in</strong>ation <strong>and</strong> tonal feet <strong>in</strong> Weledeh Dogrib (chapter<br />

9), also focuses on l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis as a process that develops over time, but <strong>in</strong> this<br />

case the evolution is across generations of l<strong>in</strong>guists. Each new l<strong>in</strong>guist to tackle an issue<br />

<strong>in</strong>herits the assumptions <strong>and</strong> traditions of his or her academic predecessors, but at the<br />

same time br<strong>in</strong>gs someth<strong>in</strong>g uniquely personal to the analysis. It is up to the resourceful<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guist to draw upon his or her own experiences to move the field forward. As Jaker notes,<br />

American structuralists have <strong>in</strong>herited from Bloomfield the notion that consonant length is<br />

a phonemic issue <strong>and</strong> therefore must be a feature that can dist<strong>in</strong>guish between utterances.<br />

Consonant length <strong>in</strong> Athabaskan languages is often seen as phonetic, not phonemic (see<br />

Jaker for references). In Dogrib, however, the picture of consonant length is more complex.<br />

Jaker shows that <strong>in</strong> light of the Optimality Theory analysis presented here, “the key generalizations<br />

about morphophonemics <strong>in</strong> Dogrib require reference to syllable weight, which<br />

<strong>in</strong> turn requires reference to consonant length—we would miss important generalizations if<br />

gem<strong>in</strong>ates were not <strong>in</strong>cluded as part of the phonology” (p. 204). Jaker br<strong>in</strong>gs his <strong>in</strong>tuitions<br />

as a native speaker of another language with contrastive consonant length, Italian, to his<br />

fieldwork, which he calls “a process of unravel<strong>in</strong>g layers of unstated assumptions, both<br />

others’ <strong>and</strong> my own. Rely<strong>in</strong>g on descriptive statements made by others means adopt<strong>in</strong>g<br />

their assumptions about what facts ought to be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the description <strong>and</strong> what should<br />

be thrown out. <strong>Fieldwork</strong> with speakers of Weledeh Dogrib enables me to go back to the<br />

orig<strong>in</strong>al speech signal <strong>and</strong> decide for myself what is structurally important <strong>and</strong> what is not”<br />

(p. 204).<br />

This collection takes its place alongside several recent publications <strong>in</strong> which field l<strong>in</strong>guists<br />

share expertise <strong>and</strong> anecdotes about the particular methodologies that make fieldwork, <strong>and</strong><br />

the scholarly analyses based on field-collected data, so compell<strong>in</strong>g (Bouquiaux & Thomas<br />

1992; Vaux <strong>and</strong> Cooper 1999; Newman & Ratliff 2001; Gippert et al. 2006; Crowley 2007;<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 7<br />

Bowern 2008; Thieberger forthcom<strong>in</strong>g). We offer the current discussion to readers with<br />

<strong>in</strong>terests <strong>in</strong> the languages of the Americas <strong>and</strong> beyond. The themes considered <strong>in</strong> these<br />

papers are <strong>in</strong> many ways pert<strong>in</strong>ent for field l<strong>in</strong>guists worldwide.<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

Introduction 8<br />

references<br />

boas, franz. 1911. Introduction to H<strong>and</strong>book of American Indian Languages (Bullet<strong>in</strong> 40,<br />

Part 1, Bureau of American Ethnology), 1-79. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton: Government Pr<strong>in</strong>t<strong>in</strong>g Office,<br />

1-83. Repr<strong>in</strong>ted 1966 [1991]. L<strong>in</strong>coln: University of Nebraska Press.<br />

boas, franz. 1917. Introduction. International Journal of American <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s 1(1).1-8.<br />

bouquiaux, luc <strong>and</strong> Jacquel<strong>in</strong>e m. c. thomas. 1992. Study<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> describ<strong>in</strong>g unwritten<br />

languages. Dallas: Summer Institute of <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong>s.<br />

bowern, claire. 2008. <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> fieldwork: A practical guide. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.<br />

crowley, terry. 2007. Field l<strong>in</strong>guistics: A beg<strong>in</strong>ner’s guide. Oxford: Oxford University<br />

Press.<br />

giPPert, Jost, nikolaus P. himmelmann, <strong>and</strong> ulrike mosel (eds.). 2006. Essentials of<br />

language documentation. Berl<strong>in</strong>, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.<br />

mithun, marianne. 2001. Who shapes the record: The speaker <strong>and</strong> the l<strong>in</strong>guist. In Paul<br />

Newman & Martha Ratliff (eds.), <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> fieldwork, 34-54.<br />

newman, Paul <strong>and</strong> martha ratliff (eds.). 2001. <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> fieldwork. Cambridge: Cambridge<br />

University Press.<br />

rice, keren. 2001. Learn<strong>in</strong>g as one goes. In Paul Newman & Martha Ratliff (eds.), <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong><br />

fieldwork, 230-249.<br />

rohner, ronald P. 1969. The ethnography of Franz Boaz, letters <strong>and</strong> diaries of Franz<br />

Boas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.<br />

thieberger, nicholas (ed.). Forthcom<strong>in</strong>g. The Oxford h<strong>and</strong>book of l<strong>in</strong>guistic fieldwork.<br />

Oxford: Oxford University Press.<br />

vaux, bert <strong>and</strong> Just<strong>in</strong> cooPer. 1999. Introduction to l<strong>in</strong>guistic field methods. Munich:<br />

LINCOM.<br />

Daisy Rosenblum<br />

drosenblum@umail.ucsb.edu<br />

Andrea L. Berez<br />

aberez@umail.ucsb.edu<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

2<br />

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 2 (May 2010):<br />

<strong>Fieldwork</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>L<strong>in</strong>guistic</strong> <strong>Analysis</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Indigenous</strong> Languages of the Americas,<br />

ed. by Andrea L. Berez, Jean Mulder, <strong>and</strong> Daisy Rosenblum, pp. 9-31<br />

http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/<br />

http://hdl.h<strong>and</strong>le.net/101025/4449<br />

Sociopragmatic <strong>in</strong>fluences on the development<br />

<strong>and</strong> use of the discourse marker vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Maya<br />

Jule Gómez de García a , Melissa Axelrod b , <strong>and</strong> María Luz García c<br />

a California State University, San Marcos<br />

b University of New Mexico<br />

c The University of Texas at Aust<strong>in</strong><br />

In this paper we explore the functions of the particle vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Mayan <strong>and</strong> argue that it is a<br />

discourse marker used to perform both structural <strong>and</strong> pragmatic functions. Vet serves as a<br />

structural marker <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g temporally or causally <strong>in</strong>terdependent items; it also has sociopragmatic<br />

functions, allow<strong>in</strong>g speakers to present an evaluation of a discourse that <strong>in</strong>vites<br />

<strong>in</strong>terlocutors to also take a stance both on the <strong>in</strong>formation presented <strong>and</strong> on their roles <strong>in</strong><br />

particular sociocultural activities. These functions of manag<strong>in</strong>g negotiations among <strong>in</strong>terlocutors<br />

range from agreements on descriptive terms to calls for social action among<br />

entire groups, <strong>in</strong> all cases highlight<strong>in</strong>g the social nature both of discourse <strong>and</strong> of group<br />

activity. The overlapp<strong>in</strong>g of the structural <strong>and</strong> pragmatic functions of vet demonstrates the<br />

grammaticalization cl<strong>in</strong>e rang<strong>in</strong>g from adverb to discourse marker proposed by Traugott<br />

(1997). Our exam<strong>in</strong>ation of vet <strong>in</strong> a range of genres produced by the Mujeres por la Paz<br />

of Nebaj, El Quiché, Guatemala, a cooperative formed <strong>in</strong> 1997 by Ixil Maya women who<br />

were widowed or left fatherless dur<strong>in</strong>g the Guatemalan civil war, suggest that the effects of<br />

the <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>and</strong> group identities <strong>and</strong> motivations of participants outweighs anticipated<br />

genre effects.<br />

1. INTRODUCTION. The twenty-n<strong>in</strong>e members of the Grupo de Mujeres por la Paz live<br />

<strong>in</strong> Nebaj, El Quiché, Guatemala, a bustl<strong>in</strong>g town <strong>in</strong> the Cuchumatanes Mounta<strong>in</strong>s, seven<br />

hours by bus from Guatemala City. The Grupo is an unofficial agricultural <strong>and</strong> weav<strong>in</strong>g cooperative<br />

formed <strong>in</strong> 1997 by Ixil Maya women who were widowed or left fatherless dur<strong>in</strong>g<br />

the Guatemalan civil war. In the early 1980s, over four hundred highl<strong>and</strong> Mayan villages,<br />

many <strong>in</strong> the Ixil area, were destroyed <strong>and</strong> over a million people were displaced with<strong>in</strong> the<br />

country or forced to move <strong>in</strong>to Mexico. Thous<strong>and</strong>s of them took up hid<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> refugee communities<br />

<strong>in</strong> the mounta<strong>in</strong>s where they lived until the mid-1990s <strong>in</strong> a state of constant flight<br />

from government troops (Sanford 2003, Falla 1998, Manz 1988). Many women returned to<br />

Nebaj from the mounta<strong>in</strong>s with their children <strong>and</strong> formed cooperatives such as the Grupo<br />

de Mujeres por la Paz to provide themselves with support <strong>and</strong> sustenance as they began<br />

rebuild<strong>in</strong>g their lives <strong>and</strong> as they struggled to support their families.<br />

The members of the Grupo de Mujeres por la Paz have been work<strong>in</strong>g with us for six<br />

years to produce a multimedia corpus of texts, photographs, videos <strong>and</strong> audio files that<br />

document their wartime experiences <strong>and</strong> their efforts at recover<strong>in</strong>g or reconstitut<strong>in</strong>g their<br />

Licensed under Creative Commons<br />

Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives License

The Discourse Marker vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Maya 10<br />

communities <strong>and</strong> families <strong>in</strong> the post-war years of the past decade. 1 Their recorded narratives<br />

describe the progress of the Grupo’s weav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> agricultural cooperative, <strong>and</strong> they<br />

document the women’s emerg<strong>in</strong>g literacy. In 2002, they agreed to help with the transcription<br />

of the audio portion of a video of their <strong>in</strong>itial plann<strong>in</strong>g meet<strong>in</strong>g for the construction of<br />

a greenhouse. At that time, we established a process that cont<strong>in</strong>ues to work well for all of<br />

us. As there are three of us on the academic team, we <strong>in</strong>vited the women to come to elicitation<br />

<strong>and</strong> transcription sessions <strong>in</strong> groups of three, a format with which they have been quite<br />

comfortable. Patiently, they participated <strong>in</strong> the work of repitiendo palabras, repeat<strong>in</strong>g what<br />

they heard on tape slowly so that we could write it down. In order to more fully participate<br />

<strong>in</strong> the transcription work, they decided they wanted to learn to read <strong>and</strong> write Ixil. Two<br />

members of the Grupo who are proficient writers of both Spanish <strong>and</strong> Ixil organized biweekly<br />

classes where the others learned to hold <strong>and</strong> manipulate pencils <strong>and</strong> pens, then to<br />

sign their names, then to write the Ixil alphabet <strong>and</strong>, eventually, words <strong>and</strong> phrases. Then<br />

they hired a professional teacher <strong>and</strong> took first-grade general education classes which <strong>in</strong>cluded<br />

not only literacy lessons, but also civics, math, <strong>and</strong> general health studies.<br />

The women took control of the transcription sessions, learned to use computers to<br />

play back audio files, <strong>and</strong> worked to transcribe their own narratives, to put their own words<br />

<strong>in</strong>to writ<strong>in</strong>g. Currently (Spr<strong>in</strong>g 2008), some of them are learn<strong>in</strong>g to use computers to type<br />

the transcriptions from the notebooks they have pa<strong>in</strong>stak<strong>in</strong>gly produced over the past two<br />

years. This entire process was carefully video or audio recorded, as were a great number of<br />

meet<strong>in</strong>gs, transcription sessions, personal histories, story-book narrations, <strong>and</strong>, of course,<br />

parties.<br />

As we transcribed, bil<strong>in</strong>gual members of the Grupo provided translations <strong>in</strong>to Spanish,<br />

translations that were often negotiated by the women who began to wonder at the functions<br />

of <strong>in</strong>dividual words. These discussions led to the general <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> grammar <strong>and</strong>, specifically,<br />

to our <strong>in</strong>vestigation of the particle vet. The record<strong>in</strong>gs gathered for the multimedia<br />

database provide the data for this paper <strong>and</strong> the many hours the women spent <strong>in</strong> negotiat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

mean<strong>in</strong>g provide the impetus <strong>and</strong> the context for analysis.<br />

2. DISCOURSE MARKERS. As we were observ<strong>in</strong>g the members of the Grupo de Mujeres<br />

por la Paz <strong>in</strong> a multitude of social contexts where <strong>in</strong>terpretation of the purpose of their activities<br />

<strong>and</strong> the negotiation of process were the conversational tasks, we began to focus on<br />

l<strong>in</strong>guistic elements used by the women to accomplish those tasks. In this paper we explore<br />

the functions of the particle vet <strong>and</strong> argue that it is a discourse marker used to perform both<br />

structural <strong>and</strong> pragmatic functions.<br />

Fraser (1999:950) def<strong>in</strong>es discourse markers as<br />

a pragmatic class, lexical expressions drawn from the syntactic classes of conjunctions,<br />

adverbials, <strong>and</strong> prepositional phrases. With certa<strong>in</strong> exceptions, they<br />

signal a relationship between the segment they <strong>in</strong>troduce, S2, <strong>and</strong> the prior seg-<br />

1 This project is supported by the National Science Foundation, BCS Grant Nos. 0504804 <strong>and</strong><br />

0504905. This work would not be possible without the dedication, patience, <strong>and</strong> good will of the<br />

members of the Grupo de Mujeres por la Paz, to whom we are extremely grateful.<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

The Discourse Marker vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Maya 11<br />

ment, S1. They have a core mean<strong>in</strong>g which is procedural, not conceptual, <strong>and</strong><br />

their more specific <strong>in</strong>terpretation is ‘negotiated’ by the context, both l<strong>in</strong>guistic<br />

<strong>and</strong> conceptual.<br />

Schiffr<strong>in</strong> also def<strong>in</strong>ed discourse markers <strong>in</strong> terms of their use to l<strong>in</strong>k segments of<br />

discourse. She called them “sequentially dependent elements that bracket units of talk”<br />

(1987:31) <strong>and</strong> listed such def<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g characteristics as syntactic detachability <strong>and</strong> occurrence<br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial position as well as their ability to occur with a range of prosodic contours <strong>and</strong><br />

‘levels’ of function with<strong>in</strong> the discourse. Her later work (Schiffr<strong>in</strong> 2001:66) highlights the<br />

fact that they are multifunctional elements that also <strong>in</strong>dex the discourse to the discourse<br />

participants. They are<br />

<strong>in</strong>dices of the underly<strong>in</strong>g cognitive, expressive, textual, <strong>and</strong> social organization<br />

of a discourse … [<strong>and</strong> that it is] ultimately properties of the discourse itself (that<br />

stem, of course, from factors as various as the speaker’s goals, the social situation,<br />

<strong>and</strong> so on) that provide the need for (<strong>and</strong> hence the slots <strong>in</strong> which) markers appear.<br />

Redeker describes this <strong>in</strong>dex<strong>in</strong>g function as one that serves to br<strong>in</strong>g to the listener’s<br />

attention “a particular k<strong>in</strong>d of l<strong>in</strong>kage of the upcom<strong>in</strong>g utterance with the immediate discourse<br />

context” (Redeker, 1991:1168). Thus, <strong>in</strong> addition to l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g propositions, that is, to<br />

provid<strong>in</strong>g coherence with<strong>in</strong> a discourse, discourse markers have an important metatextual<br />

function of l<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g the discourse to its producers <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terpreters. As Traugott (1997) puts<br />

it, discourse markers “allow speakers to display their evaluation not of the content of what<br />

is said, but of the way it is put together; <strong>in</strong> other words, they do metatextual work.” Crismore<br />

et al (1993) describes metatextual devices as strategies that allow speakers or writers<br />

to draw attention to the “act of discours<strong>in</strong>g,” <strong>and</strong> help <strong>in</strong>terlocutors to organize, classify,<br />

<strong>in</strong>terpret, <strong>and</strong> evaluate propositional material.<br />

It is this metatextual function of discourse markers that allows manipulation of the<br />

alignments <strong>and</strong> of the roles <strong>and</strong> responsibilities of participants <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>teraction. Discourse<br />

markers used metatextually allow speakers to present an evaluation of a discourse that<br />

<strong>in</strong>vites <strong>in</strong>terlocutors to also take a stance regard<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation presented.<br />

What we will see <strong>in</strong> the analysis of the data is the duality of function of this discourse<br />

marker. It serves as a structural marker <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g temporally or causally <strong>in</strong>terdependent<br />

items; it also <strong>in</strong>dicates metatextual comment on the discourse itself <strong>and</strong>, importantly, on<br />

the <strong>in</strong>terlocutors’ roles <strong>in</strong> particular sociocultural activities. We f<strong>in</strong>d that the occurrences of<br />

vet thus <strong>in</strong>clude structural adverbial functions that often co-occur with the sociopragmatic<br />

functions of manag<strong>in</strong>g negotiations among <strong>in</strong>terlocutors. These sociopragmatic uses range<br />

from agreements on descriptive terms to calls for social action among entire groups, <strong>in</strong> all<br />

cases highlight<strong>in</strong>g the social nature both of discourse <strong>and</strong> of group activity. This use of<br />

vet is similar to the notion of <strong>in</strong>dexical ‘shifter’, which Hanks (1987:682) def<strong>in</strong>es as items<br />

that “relate utterances to their speakers, addressees, actual referents, place <strong>and</strong> time of occurrence.<br />

Indexical center<strong>in</strong>g is a primary part of the <strong>in</strong>terpretation of discourse because<br />

it connects the evaluative <strong>and</strong> semantic code with the concrete circumstances of its use.”<br />

The overlapp<strong>in</strong>g of the structural <strong>and</strong> pragmatic functions of vet demonstrates the grammaticalization<br />

cl<strong>in</strong>e rang<strong>in</strong>g from adverb to discourse marker proposed by Traugott (1997).<br />

fieldwork <strong>and</strong> l<strong>in</strong>guistic analysis <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>digenous languages of the americas

The Discourse Marker vet <strong>in</strong> Ixil Maya 12<br />

3. ADVERBIAL USES OF VET. The only previous analysis of vet is that of Ayres (1991),<br />

who focuses on the use of vet as an adverbial that “means someth<strong>in</strong>g like ya [‘already’], entonces<br />

[‘then’], or luego [‘soon, later’]. It is used after the verb, before the directional that<br />