- Page 5:

A.V. Kelly 2004First published 2004

- Page 11:

xThe CurriculumThe initial ambivale

- Page 15 and 16:

xivThe Curriculumbackground constra

- Page 17 and 18:

xviThe Curriculumshould be avoided

- Page 19 and 20:

towards central political control o

- Page 21 and 22:

The Curriculumthat, to the extent t

- Page 23 and 24:

The Curriculumsuch as Ivan Illich (

- Page 25 and 26:

the planners, the procedures adopte

- Page 27 and 28:

The Curriculummoral purpose of the

- Page 29 and 30:

The Curriculumwhich have been learn

- Page 31 and 32:

The CurriculumWe have long been fam

- Page 33 and 34:

The CurriculumIdeologies and curric

- Page 35 and 36:

The CurriculumQuite serious and ext

- Page 37 and 38:

The Curriculumcance of that asserti

- Page 39 and 40:

The Curriculummechanical view is by

- Page 41 and 42:

een removed from their sphere of in

- Page 43 and 44:

ing the problematic nature of human

- Page 45 and 46:

The Curriculumagainst the mysticism

- Page 47 and 48:

The Curriculumhave seen is characte

- Page 49 and 50:

The Curriculumknowledge rather than

- Page 51 and 52:

The Curriculummust be attempted, be

- Page 53 and 54:

The Curriculummust be ‘forced to

- Page 55 and 56:

The CurriculumAnd it has led some c

- Page 57 and 58:

The Curriculumwords, alternative di

- Page 59 and 60:

The Curriculumtheir dangers, howeve

- Page 61 and 62:

The Curriculumpost-modernism puts o

- Page 63 and 64:

3Curriculum as Content and ProductW

- Page 65 and 66:

The Curriculumpresent it. In a cont

- Page 67 and 68:

The Curriculumschool and can ultima

- Page 69 and 70:

The Curriculumpupils rather than th

- Page 71 and 72:

The CurriculumHowever, it is clear

- Page 73 and 74:

It is because of this fundamental i

- Page 75 and 76:

The Curriculumonly in the United St

- Page 77 and 78:

The Curriculumlum planning is that

- Page 79 and 80:

The Curriculumthe use of this model

- Page 81 and 82:

The CurriculumIt is easy to see why

- Page 83 and 84:

The Curriculumcurriculum planners w

- Page 85 and 86:

The Curriculumfor their own sake, a

- Page 87 and 88:

The CurriculumOne major reason, the

- Page 89 and 90:

The Curriculumbe broken down into

- Page 91 and 92:

objectives, and even, perhaps espec

- Page 93 and 94:

4Curriculum as Process and Developm

- Page 95 and 96:

the basic principles of democratic

- Page 97 and 98:

The first of these, the rejection o

- Page 99 and 100:

The Curriculumprinciples inherent i

- Page 101 and 102:

Education as developmentIt is worth

- Page 103 and 104:

The Curriculumsupports this kind of

- Page 105 and 106:

The Curriculummodel of curriculum r

- Page 107 and 108:

What the developmental model offers

- Page 109 and 110:

The Curriculumwhich we discussed in

- Page 111 and 112:

The CurriculumThere are aspects of

- Page 113 and 114:

God-given status of certain kinds o

- Page 115 and 116:

The Curriculumpractice, it is impor

- Page 117 and 118:

Key issues raised by this chapter1

- Page 119 and 120:

The CurriculumFirst of all we will

- Page 121 and 122:

The Curriculummain significance of

- Page 123 and 124:

The CurriculumTake-Up Project (Scho

- Page 125 and 126:

The Curriculumrelated sources. Firs

- Page 127 and 128:

The Curriculumthat this is not a mo

- Page 129 and 130: The Curriculumand for providing the

- Page 131 and 132: The Curriculumopposition and hostil

- Page 133 and 134: extending and otherwise reordering

- Page 135 and 136: The Curriculumwhich arose, then, wa

- Page 137 and 138: The CurriculumThese were among the

- Page 139 and 140: The Curriculumabout the major chang

- Page 141 and 142: The CurriculumChapter 8 that a nati

- Page 143 and 144: 6Assessment, Evaluation, Appraisal

- Page 145 and 146: The Curriculumous assessment forms

- Page 147 and 148: The CurriculumThe realities of Nati

- Page 149 and 150: The Curriculumargued (Nuttall, 1989

- Page 151 and 152: The Curriculumlinked to a curricula

- Page 153 and 154: Testing and curriculum controlFinal

- Page 155 and 156: The Curriculumproduces. And so diff

- Page 157 and 158: The Curriculuming (Stenhouse, 1975)

- Page 159 and 160: The Curriculumbut which nevertheles

- Page 161 and 162: The Curriculumuation procedures see

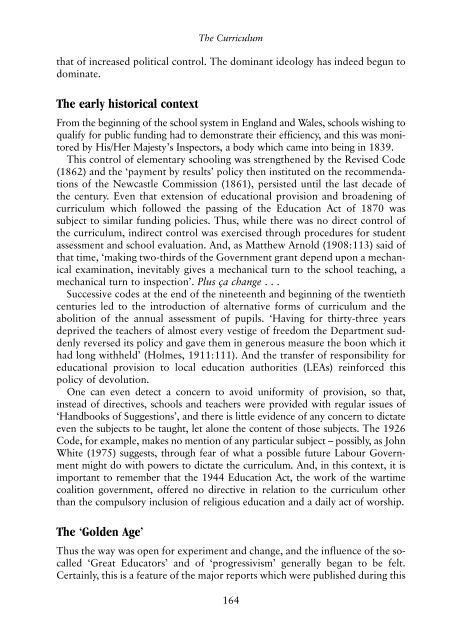

- Page 163 and 164: The CurriculumThis clearly leads us

- Page 165 and 166: The Curriculumthe innovation, not m

- Page 167 and 168: The Curriculuminto play after someo

- Page 169 and 170: The CurriculumThe intrinsic, democr

- Page 171 and 172: The Curriculumwe must note here the

- Page 173 and 174: The Curriculumpolitically grounded

- Page 175 and 176: The Curriculumprofessional judgemen

- Page 177 and 178: of educational research, have becom

- Page 179: The CurriculumDirect and indirect p

- Page 183 and 184: The Curriculumof subjects (humaniti

- Page 185 and 186: The Curriculumintellectual impoveri

- Page 187 and 188: The CurriculumIn short, one can det

- Page 189 and 190: The Curriculumclearly defined, ‘t

- Page 191 and 192: The Curriculumdirected towards what

- Page 193 and 194: The Curriculumprovision, and the 19

- Page 195 and 196: The CurriculumImpact on the trainin

- Page 197 and 198: The Curriculumhalf the members of s

- Page 199 and 200: The Curriculumtraditonal moral valu

- Page 201 and 202: context, it is clearly not appropri

- Page 203 and 204: The Curriculumthe pursuit of profit

- Page 205 and 206: The Curriculumchanges or can be cha

- Page 207 and 208: The Curriculumthe what of the curri

- Page 209 and 210: 8A Democratic and Educational Natio

- Page 211 and 212: The CurriculumKingdom was an except

- Page 213 and 214: The Curriculumapproach such as this

- Page 215 and 216: The Curriculumthe inclusion of thos

- Page 217 and 218: The Curriculumof the piecemeal appr

- Page 219 and 220: The Curriculumchapters, but the maj

- Page 221 and 222: of Education, 1931) and reinforced

- Page 223 and 224: The Curriculumas ‘one of the soci

- Page 225 and 226: The Curriculumforward the approach

- Page 227 and 228: The CurriculumAgain, therefore, we

- Page 229 and 230: The CurriculumThe implications of t

- Page 231 and 232:

The Curriculumbut every attempt mus

- Page 233 and 234:

The Curriculumimplemented in such a

- Page 235 and 236:

The Curriculumcontent but on common

- Page 237 and 238:

The Curriculumtion must be planned

- Page 239 and 240:

A Chronology of Curriculum Developm

- Page 241 and 242:

1965 Circular 10/65 requires all lo

- Page 243 and 244:

BibliographyAlexander, R.J. (1984)

- Page 245 and 246:

The CurriculumPhiladelphia: Open Un

- Page 247 and 248:

The CurriculumFoot, P. (1999) ‘Th

- Page 249 and 250:

The CurriculumJames, C.M. (1968) Yo

- Page 251 and 252:

The Curriculumstudy’. PhD thesis,

- Page 253 and 254:

The CurriculumSimon, B. (1985) Does

- Page 255 and 256:

The CurriculumGoverment reports and

- Page 257 and 258:

Author IndexAdelman, C., 118, 120,

- Page 259 and 260:

The Curriculum165, 167, 171, 175, 1

- Page 261 and 262:

Subject Indexability, 22, 196, 206a

- Page 263 and 264:

The Curriculumconditioning, 47Confe

- Page 265 and 266:

The CurriculumEducation Act (1944),

- Page 267 and 268:

The Curriculum172, 180-181see also

- Page 269 and 270:

The Curriculumpsycho-motor, 57see a

- Page 271 and 272:

The Curriculumscientific approaches