Social Mobilization and Behavior Change Communication for

Social Mobilization and Behavior Change Communication for

Social Mobilization and Behavior Change Communication for

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

This publication was prepared by AED <strong>and</strong> funded by the United States Agency <strong>for</strong> International Development undercontract number GHS-I-00-03-00036. It does not necessarily represent the views of USAID or the US Government.September 2009

PREAMBLE:This publication is the product of ongoing collaboration over the past four yearsbetween UNICEF <strong>and</strong> AI.COMM, a USAID project managed by AED, to design <strong>and</strong>implement effective communication programs in developing countries, first <strong>for</strong> avianinfluenza <strong>and</strong> more recently <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza preparedness <strong>and</strong> response.AI.COMM has been USAID’s principal mechanism <strong>for</strong> developing communicationstrategies <strong>and</strong> tools to prevent <strong>and</strong> control influenza outbreaks, including those approachesdiscussed in the framework of this document--behavior change communication,social mobilization, policy advocacy, <strong>and</strong> risk communication. In addition tosharing this framework, UNICEF bases its approach to communication on the humanrights principle that children <strong>and</strong> adolescents, their families, <strong>and</strong> communities havethe right to in<strong>for</strong>mation, communication, <strong>and</strong> participation. Thus, UNICEF promotesfull participation, gender equity <strong>and</strong> social inclusion in the development process ingeneral, <strong>and</strong> in communication in particular.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:This document was jointly prepared <strong>and</strong> funded by UNICEF <strong>and</strong> AI.COMM. The writingteam was led by Rebecca Fields from AI.COMM <strong>and</strong> Judith Graeff from UNICEF/New York. Drafts of the document were reviewed by staff from UNICEF, AI.COMM,<strong>and</strong> USAID, including: Françoise Vanni (UNICEF/Mexico); Surangani Abeyesekera <strong>and</strong>Patricia Portela Souza (UNICEF/Bangladesh); Sahar Hegazi (UNICEF/Egypt); Tran Tung(UNICEF/Asia Pacific Shared Services Centre); Pornthida Padthong (UNICEF/Thail<strong>and</strong>);Natalie Fol <strong>and</strong> Fabio Friscia (UNICEF/West <strong>and</strong> Central Africa); Paula Claycomb,Teresa Stuart, Neha Kapil, <strong>and</strong> Jesus Lopez-Macedo (UNICEF/New York); Anton Schneider(AI.COMM/Thail<strong>and</strong>); Eleanora De Guzman (AI.COMM/Vietnam); Cecile Lantican(AI.COMM/Lao PDR); Yaya Drabo (AI.COMM/West Africa); Phil Sedlak (AI.COMM/Nepal); Soliman Farah (AI.COMM/South Asia); Mark Rasmuson <strong>and</strong> Dee Bennett (AI.COMM/Washington); <strong>and</strong> Kama Garrison (USAID/Washington).

IntroductionIn June, 2009, the World Health Organization officially declared that a globalp<strong>and</strong>emic of type A (H1N1) influenza was under way. One of the critical interventionsto limit the transmission of the disease, mitigate its health impact, <strong>and</strong> contain thesocial <strong>and</strong> economic disruption it may cause is to ensure the ongoing provision ofeffective communication.This document provides an overview of strategic communication as it appliesto p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza in low <strong>and</strong> middle income countries. It is based both ontechnically sound communication principles <strong>and</strong> recent experience in severalcountries that have been proactive in communication ef<strong>for</strong>ts related to p<strong>and</strong>emic <strong>and</strong>avian influenza.The purpose of this document is to provide a framework <strong>and</strong> guidance to planners <strong>for</strong>developing country-specific social mobilization <strong>and</strong> behavior change communicationstrategies <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza. These strategies incorporate communicationobjectives, participant groups, desired behaviors, types of messages, selection ofchannels, <strong>and</strong> approaches to communication planning <strong>and</strong> implementation in supportof country-level ef<strong>for</strong>ts <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza response.A key component of the social <strong>and</strong> behavior change communication processis to integrate the involvement of marginalized <strong>and</strong> hard-to-reach groups incommunication planning <strong>and</strong> implementation so that they become active participants- not just passive recipients of in<strong>for</strong>mation. Involvement not only helps to adaptcommunication strategies <strong>and</strong> messages to the local context, but also connectsthe perspective of minorities <strong>and</strong> the hard-to-reach to upstream policy advocacyregarding p<strong>and</strong>emic response issues—<strong>for</strong> example, steps to take to reduce inequitiesin economic impact. In addition, access to limited supplies of vaccine <strong>and</strong> anti-viralmedications could become a critical issue. <strong>Communication</strong> should play a role inadvocating <strong>for</strong> equitable access, in accordance with official medical recommendations<strong>for</strong> the use of these products.Some countries may choose to use this guidance to help develop a focused plan ofaction <strong>for</strong> immediate response, while others may find it useful in drafting a broader,longer-term strategy. This decision will be made depending upon national needs,capacity <strong>and</strong> the extent of communication planning that has already been carriedout <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza. For example, in countries with no, or very few, cases oftype A H1N1 (2009) influenza despite the p<strong>and</strong>emic, this time of heightened globalawareness can be used as an opportunity to prepare <strong>and</strong> to strengthen ongoingdevelopment <strong>and</strong> communication initiatives.Intended users of this PLANNING GUIDANCEThis guidance document is intended primarily <strong>for</strong> those who are already familiarwith the basic principles of communication planning <strong>and</strong> implementation. It is nota detailed, “how-to” document with step-by-step instructions on each aspect of7

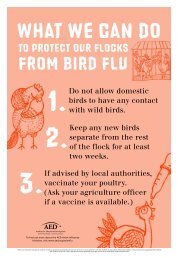

communication planning <strong>and</strong> implementation, but rather a concise overview ofcommunication as it pertains to p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza. For readers seeking moredetailed in<strong>for</strong>mation, the Resources section of this document provides references <strong>and</strong>electronic links to additional documents <strong>and</strong> websites.This document might also be shared with governments, donors, <strong>and</strong> within one’s ownorganization to advocate <strong>for</strong> adequate human, financial <strong>and</strong> material resources to plan<strong>and</strong> implement effective communication during a p<strong>and</strong>emic.Technical basis of communication <strong>for</strong> the H1N1influenza p<strong>and</strong>emicWHO/UNICEFrecommended behaviors:To reduce transmission:• Keep your distance from someone who iscoughing <strong>and</strong> sneezing• Stay home if you feel ill• Cover your coughs <strong>and</strong> sneezes• Wash your h<strong>and</strong>s with soap <strong>and</strong> waterTo lessen the health impact:• Give sick people a separate space at home• Assign a single caregiver to a sick person• Give plenty of fluids to the sick person• Recognize danger signs <strong>and</strong> seek prompt care*WHO/UNICEF: Behavioural interventions <strong>for</strong>reducing the transmission <strong>and</strong> impact of influenza A(H1N1) virus” June, 2009BOX 1The approaches <strong>and</strong> contentreflected here support the currentrecommendations on p<strong>and</strong>emicinfluenza of the World HealthOrganization <strong>and</strong> other internationalhealth partners. Because the actualcourse of disease <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic (H1N1)2009 cannot be predicted with certainty,<strong>and</strong> because the effectiveness of somepublic health interventions is still beingdetermined, readers are encouragedto consult WHO in<strong>for</strong>mation sourceson a regular basis. 1 These sourcespresent clearly the recommendedactions that national communicationinitiatives are to promote; key behaviorsare described in Box 1. As the technicalresponse to the p<strong>and</strong>emic continues toevolve, so must communication ef<strong>for</strong>tsto support that response.A coordinated approach to communicationplanningNational governments are the lead authority on p<strong>and</strong>emic response <strong>and</strong> communication.Because p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza has social <strong>and</strong> economic consequences as well as healthconsequences, representation from a wide range of development partners, bothpublic <strong>and</strong> private sector, needs to contribute to both p<strong>and</strong>emic preparedness <strong>and</strong>response. Coordination is also the key to success in planning <strong>and</strong> implementingstrategic communication <strong>for</strong> a situation as complex as p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza.National governments have found that working through a designated coordinationbody with membership to reflect the broad range of partners <strong>and</strong> stakeholdersimproves the planning <strong>and</strong> delivery of an effective response, includingcommunication. Rather than creating a new group, some countries have chosen tomake use of existing coordination bodies, adjusting their membership to address1For current, authoritative in<strong>for</strong>mation on the evolving global situation, readers should consult the WHOwebsite on p<strong>and</strong>emic (H1N1) 2009 influenza http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/en/index.html8

BOX 3LESSONS LEARNED ON EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATIONFROM AVIAN INFLUENZA AND SARS EXPERIENCESThese “lessons learned” have been extracted from two surveys of communication experiences gained from severalrecent epidemics. The Waisbord report 2 is based on 19 program reports <strong>and</strong> 14 national surveys in countriesaffected by avian flu as well as eight in-depth interviews with communication officers in the field. The Schiavo paper 3looked more broadly at lessons learned from avian flu, SARS, Ebola <strong>and</strong> anthrax outbreaks—conducting a literaturereview <strong>and</strong> 19 in-depth interviews with a variety of experts working in communication, emergency operations <strong>and</strong>public health, from national governments <strong>and</strong> global agencies. The consistency of response is striking. The lessonslearned are summarized below. Full versions of these reports can be found on: www.influenzaresources.org1. <strong>Communication</strong> interventions have been reportedly effective in increasing knowledge. Reports show thatknowledge about modes of transmission, symptoms, safe ways of disposing of sick/dead birds <strong>and</strong> preventionincreased after communication interventions.2. Increases in knowledge do not necessarily translate into effective behavioral changes. This leads to aconsiderable knowledge-practice gap. Few behavioral changes were found after communication interventions,even when knowledge about prevention <strong>and</strong> transmission increased.3. <strong>Communication</strong> interventions should go beyond in<strong>for</strong>mation transmission given that the lack of knowledge isnot the only or even the main, obstacle to per<strong>for</strong>ming desired practices.4. <strong>Communication</strong> should be integrated with initiatives that reduce obstacles to practicing healthy behaviors.Often, recommended behaviors are not feasible to do—even if an individual is motivated. Wider practice ofrecommended behaviors is often enhanced by changing policy, physical, <strong>and</strong> economic barriers rather thanfocusing communication on individual attitude <strong>and</strong> knowledge.5. Easy access <strong>and</strong> trust are two key considerations in selecting communication channels. These elements will bedifferent <strong>for</strong> different audiences—thus segmenting audience groups is a critical part of the planning process.6. Engaging trusted community groups <strong>and</strong> leaders may be more effective in reaching vulnerable/marginalizedgroups than disseminating centrally-generated messages through mass media.7. <strong>Communication</strong> should address local attitudes <strong>and</strong> stigma possibly associated with doing the desiredbehaviors.8. Messages should clearly tell people what benefits they would reap if they were to practice the recommendedbehaviors. Benefits should not be limited to conventional public health goals such as “achieving healthycommunities/families” or “preventing disease”. They should also consider a host of immediate social <strong>and</strong>economic rewards that can be associated with desired behavior.9. It is important to clarify expected behavioral <strong>and</strong> social outcomes <strong>and</strong> adapt recommended actions to the localcontext.10. Coordination among government counterparts, development partners <strong>and</strong> UN agencies is crucial <strong>for</strong> effectivecommunication with harmonized messages. This avoids confusion that can impede widespread adoption ofrecommended behaviors.11. Early integration of medical <strong>and</strong> scientific teams with communication teams can further contribute to a swiftresponse <strong>and</strong> to the development of community resilience during an outbreak.12. Timely, strategic, <strong>and</strong> well-coordinated communication ef<strong>for</strong>ts could make a difference not only in mitigatingthe consequences of an emergency, but also in managing people’s reaction during crises. Well managed,credible communication increases the likelihood that recommended behaviors <strong>and</strong> social actions will beadopted by the population.13. Early participation of key private sector partners, such as physicians <strong>and</strong> pharmacists, <strong>and</strong> commercial sectorbusinesses <strong>and</strong> employers is important so they will take their role in reducing transmission <strong>and</strong> mitigating thehealth, social <strong>and</strong> economic impact of the disease.2 Assessment of UNICEF-supported communication initiatives <strong>for</strong> prevention <strong>and</strong> control of avian influenza”, Finalreport <strong>for</strong> UNICEF, Silvio Waisbord, Ph.D., March, 2008.3 “Mapping <strong>and</strong> review of existing guidance <strong>and</strong> plans <strong>for</strong> community <strong>and</strong> household based communication toprepare <strong>and</strong> respond to p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza”, Research report <strong>for</strong> UNICEF, Renata Schiavo, January, 2009.

public health policy <strong>and</strong> any social reaction to the response <strong>and</strong> the disease itself. Animportant part of planning, then, is to decide how key communication partners willremain in contact if working conditions change radically during the p<strong>and</strong>emic.Lessons learned from past epidemicsWhile communication <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza has its own unique attributes, a usefulbody of knowledge exists from outbreaks over the past ten years of Severe AcuteRespiratory Syndrome (SARS), avian influenza, <strong>and</strong> Ebola virus that can guide currentcommunication initiatives. These are summarized in Box 3.<strong>Communication</strong> <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic response: KeyelementsIn the current response to p<strong>and</strong>emic (H1N1) 2009 influenza, some countries areable to build upon the communication strategy <strong>and</strong> activities conducted <strong>for</strong> avianinfluenza <strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic preparedness. Other countries are less well prepared. Ineither case, it is important to find a balance between working rapidly to implementthe communication necessary <strong>for</strong> the response while also respecting the fundamentalsof effective social <strong>and</strong> behavior change communication—the use of evidence,participation, <strong>and</strong> adaptation.In order to find this balance, it is useful to rely on existing resources as much aspossible. For example, planners can use existing demographic <strong>and</strong> social data (suchas from Demographic <strong>and</strong> Health Surveys – DHS) <strong>for</strong> selecting participant groups <strong>and</strong>communication channels; or they can use existing networks at the community level <strong>for</strong>social mobilization <strong>and</strong> behavior change communication.The following key elements should be included in a communication strategy tosupport a country’s response—particularly at the community level—to the currentp<strong>and</strong>emic influenza.<strong>Communication</strong> objectives: For communication to be effective, especially ata time of a p<strong>and</strong>emic when there is uncertainty about how it will affect a country,key partners <strong>and</strong> stakeholders should reach consensus at the national level on theobjectives of communication. This should happen be<strong>for</strong>e an outbreak occurs in thecountry. On a generic level, these objectives include the following:• Help to reduce transmission of disease• Mitigate health impact• Minimize panic <strong>and</strong> social disruption• Help governments provide crediblein<strong>for</strong>mation during responseSome countries will use this current p<strong>and</strong>emic todevelop a comprehensive, long-term strategy toencompass newly emerging infectious diseases<strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emics. Other countries will modify an<strong>Communication</strong> objectives needto be the product of joint planningby health officials, communicationspecialists <strong>and</strong> key partners <strong>and</strong>stakeholders.12

existing strategy developed <strong>for</strong> avian influenza <strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic preparedness, ordevelop a brief strategy just to address the current p<strong>and</strong>emic.Regardless, the strategy should describe how communication will use a combinationof advocacy, social mobilization <strong>and</strong> behavior change communication through avariety of channels to achieve each objective. For example, to reduce diseasetransmission:• advocacy to make appropriate policy changes can be carried out with public<strong>and</strong> private schools <strong>and</strong> major employers;• social mobilization activities can be implemented to create a supportiveenvironment <strong>for</strong> recommended hygiene <strong>and</strong> cough etiquette behaviors;• behavior change communication activities can be conducted to tailor messagesto the needs of each participant group, including school children, people atwork, parents, <strong>and</strong> slum dwellers.Any communication strategy should include anaction plan to guide communication activities <strong>for</strong>immediate implementation.Key participant groups: Many communicationprofessionals use terms such as target groupor target audience to indicate the segments ofthe population <strong>for</strong> which the communication isintended; these terms suggest a passive recipientof in<strong>for</strong>mation. This document, however, uses theterm “participant group” to designate the peopleat various levels who need to take action <strong>for</strong> aneffective communication response to the p<strong>and</strong>emic. Suggested participant groupsat all levels <strong>and</strong> the actions they can take to support appropriate p<strong>and</strong>emic responseare illustrated in Figure 1 on page 20.The selection of key participant groups should be based on data from previousresearch, current programs, <strong>and</strong> communication initiatives.Variables to consider when selecting key participant groups are:Each high-risk groupidentified by WHO containswithin it particularlyvulnerable <strong>and</strong> marginalizedsub-groups who may need tobe reached through specialcommunication ef<strong>for</strong>ts.• Epidemiological evidence—P<strong>and</strong>emic (H1N1) 2009 mostly affects pregnantwomen, young people (between 5 <strong>and</strong> 24 years of age), <strong>and</strong> people withpreexisting health conditions such as asthma, diabetes <strong>and</strong> obesity. Readers areencouraged to check www.who.int <strong>for</strong> updated in<strong>for</strong>mation.• <strong>Social</strong>ly-marginalized groups, such as slum dwellers, minorities, <strong>and</strong> women arevulnerable to social <strong>and</strong> economic consequences of any emergency.• Language groups—including languages used by indigenous or immigrantgroups; such groups risk being excluded from the in<strong>for</strong>mation flow.• Urban <strong>and</strong> rural populations have access to different channels of in<strong>for</strong>mation.• Children <strong>and</strong> adolescents are vulnerable to H1N1 disease, <strong>and</strong> countryexperience indicates that they are at risk of abuse during a prolongedp<strong>and</strong>emic. They also risk having interrupted schooling. Children in orphanages,13

correctional institutions, migrant/refugee camps, <strong>and</strong> boarding schools mighthave no one to advocate <strong>for</strong> their right to equal access to care.Marginalized groups: An important consideration in p<strong>and</strong>emic response is how toinvolve <strong>and</strong> reach socially-marginalized groups in a country. The very fact that they aremarginalized (by ethnicity, race, religion, economic means, displacement, profession)means that they are rarely involved in decisions affecting their well-being <strong>and</strong> haveless access to in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>and</strong> services. <strong>Communication</strong> <strong>for</strong> social <strong>and</strong> behaviorchange emphasizes inclusion of the marginalized in all steps of the communicationprocess, yet in a p<strong>and</strong>emic response mode, planners are often pressured to get oneset of messages out to the “general public” as rapidly as possible. Underst<strong>and</strong>ingthis reality, following are some possible ways to increase meaningful engagement of<strong>and</strong> reach to marginalized groups.a. Work with the government to map traditionally marginalized groups in thecountry <strong>and</strong> advocate <strong>for</strong> commitment that they will be reached during thep<strong>and</strong>emic.b. Identify humanitarian groups (such as the International Red Cross/Crescent,Medecins Sans Frontieres, Catholic Relief Services, <strong>and</strong> UN humanitarianagencies) that could reach marginalized people <strong>and</strong> orient/equip these agencieswith appropriate communication materials.c. Involve local leaders or advocacy groups <strong>for</strong> the marginalized in various aspectsof p<strong>and</strong>emic response (not just in pre-testing materials!). Representativescan participate in planning how to disseminate prevention messages to theirrespective group(s); help adapt messages to the lifestyle reality of their group;<strong>and</strong> update the group continually as the p<strong>and</strong>emic progresses.These steps might be politically sensitive <strong>and</strong> will take time <strong>and</strong> resources justwhen they are scarce. But the benefits to the country will be great if marginalizedpopulations feel more engaged <strong>and</strong> there<strong>for</strong>e more likely to take appropriate actionin a time of national alert.Desired <strong>and</strong> feasible behaviors: In May 2009, WHO <strong>and</strong> UNICEF disseminatedeight key behaviors (shown in Box 1) that will help to reduce transmission <strong>and</strong> lessenthe health impact of the (H1N1) 2009 influenza. Countries may also choose toadopt some non-health behaviors to the essential list, such as infant feeding, childprotection, <strong>and</strong> continued learning during school closures.With these behaviors as a starting point, it is important to seek wide participation inhow these behaviors can be adapted to the local context. In addition to discussionswithin the national coordination body, representatives of key minority groups, youth,or other important segments of the population can be included on planning <strong>and</strong>message design teams.Addressing feasibility: In an ef<strong>for</strong>t to respond rapidly, some planning teams may notsee the need to adapt recommended behaviors to the realities of the population.Failure to go into more detail about the feasibility of recommended behaviors,however, risks lowering both the effectiveness <strong>and</strong> the credibility of communicationef<strong>for</strong>ts. For example, how will people cover coughs <strong>and</strong> sneezes if no cloth or14

Messages should beadapted to reflect:disposable tissues are available? How can sick people stay home if their familydepends on their daily earnings? How can transmission be reduced in schools wherefrequent h<strong>and</strong> washing <strong>and</strong> physical distancing are not possible? How can publictransport or daily marketing be made safer? Taking the time to address these issuesin developing a list of feasible behaviors will improve their widespread adoption.Making some behaviors feasible <strong>for</strong> individuals is often better addressed atthe policy level. The last two questions above might be better addressed withtemporary policy changes rather than an emphasis on individual behavior change.To lower transmission at work settings—another example—temporary changes inscheduling, work space <strong>and</strong> work processes could improve h<strong>and</strong> washing possibilities,facilitate safe disposal of tissues <strong>and</strong> face masks, <strong>and</strong> lower occasions <strong>for</strong> closecontact. <strong>Communication</strong> plans should include policy advocacy to trigger timely <strong>and</strong>appropriate decisions by government <strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic partners to support adoption ofrecommended behaviors to scale.Adapted messages: Sometimes the first reactionplanners have to the time pressure during p<strong>and</strong>emicresponse is to develop generic messages based onscientific evidence alone. Planners often think thattranslating generic messages into multiple local languagesis a sufficient way to adapt them. However, messagesbased exclusively on technical content are unlikely tobe fully effective in promoting desired behaviors <strong>and</strong>social action. Messages need to reflect local perceptionsof risk <strong>and</strong> disease transmission <strong>and</strong> an underst<strong>and</strong>ingof the perceived consequences to per<strong>for</strong>ming desiredbehaviors. Emotional appeal is also important in messagedevelopment. In some countries, social research data willbe available to in<strong>for</strong>m the design of messages. But if not,it will be particularly important to conduct a small numberof focus group discussions with selected participant groupsto assure (at a minimum) that messages are understood<strong>and</strong> acceptable. As stated earlier, representatives of keyparticipant groups should participate in communication planning (such as messagedevelopment workshops) to facilitate adaptation of messages to these groups.• Local perceptions ofdisease transmission• Feasible <strong>and</strong> locallyrelevantcalls to action• Perceived consequencesto per<strong>for</strong>ming thebehavior• Emotional appealOne serious issue that has arisen in some countries that have been hard hit bythe 2009 influenza p<strong>and</strong>emic is stigma against sick people <strong>and</strong> members of theirhouseholds. <strong>Communication</strong> teams should anticipate this possibility <strong>and</strong> revise theirmessages as needed to promote supportive actions <strong>and</strong> care toward those who aredirectly or indirectly affected by p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza.Credible sources of in<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>and</strong> appropriate channels: The channelsto use during the p<strong>and</strong>emic are likely to vary widely depending upon how differentsegments of the population (participant groups) access <strong>and</strong> use in<strong>for</strong>mation. As muchas possible, planners can use existing data to determine access <strong>and</strong> credibility ofcommunication channels <strong>for</strong> the participant groups mentioned in the communication15

strategy. For example, there may be substantial differences between urban <strong>and</strong> ruralareas regarding access to <strong>and</strong> credibility of messages provided through mass media.In the early stages of a country’s response to the p<strong>and</strong>emic, radio, TV, <strong>and</strong> flyers/posters are often the channels of choice. Their advantage is their broad reach <strong>and</strong>ability to h<strong>and</strong>le “fast-breaking news”. Butmany countries have discovered that as theCOMMUNICATIONCHANNELSMASS MEDIA: Television,radio, newspapers, posters,billboards, leafletsTRADITIONAL MEDIA: folktheatre, puppets, poetry/song, social & religiousgatheringsINTERPERSONALCOMMUNICATION:household visits,courtyard meetings,health education, socialmobilization, school activitiesNEW MEDIA: Cell phones,SMS, internet (websites,blogs, Twitter), telephonehotlinesp<strong>and</strong>emic continues, other channels need to beused to reach effectively different participantgroups such as school children, pregnantwomen, indigenous peoples. For example,interpersonal communication from trustedsources is likely to be important to reachmarginalized populations or those outside thereach of broadcast media. (See section onpartners <strong>for</strong> social mobilization below).Interpersonal communication (IPC) channels,having limited reach, can rein<strong>for</strong>ce <strong>and</strong>personalize the general in<strong>for</strong>mation providedthrough mass media channels <strong>and</strong> can provideopportunities <strong>for</strong> dialogue <strong>and</strong> problemsolvingthat other channels cannot. In a highlycontagious influenza p<strong>and</strong>emic, however,the use of IPC might be limited because ofpotential transmission opportunities. Ways touse IPC without close physical contact includeusing megaphones, remaining outside duringhousehold visits, <strong>and</strong> not giving h<strong>and</strong>outs.Health care providers <strong>and</strong> community healthworkers can play a role in IPC during thep<strong>and</strong>emic. Yet, when an outbreak occurs, healthcare services can be overwhelmed <strong>and</strong> healthworkers are likely to be overtaken by clinicalduties; so their role as communicators can be greatly compromised. While theycannot provide typical health education sessions during an outbreak, they can learnto communicate with patients <strong>and</strong> families during clinical care. Thus, health workersshould be prepared so that they can provide key in<strong>for</strong>mation, respond to the concernsof their patients, <strong>and</strong> communicate their patients’ concerns onward as needed. Thenational <strong>and</strong> local coordinating bodies should determine who will take responsibility<strong>for</strong> communication training of health workers so that it is integrated into the nationalcommunication plan.The education system is an important communication channel in p<strong>and</strong>emicresponse—both through policy decisions <strong>and</strong> through promoting preventivebehaviors while schools are in session. <strong>Behavior</strong> change communication can reachstudents through age-appropriate lessons, games <strong>and</strong> songs as well as through16

peer group interaction. Teachers <strong>and</strong> students are often seen as credible sources ofin<strong>for</strong>mation <strong>and</strong> can be mobilized <strong>for</strong> outreach to the community.Many countries are experimenting with new media (see text box) to help in p<strong>and</strong>emiccommunication. While cell phone ownership is high in many countries, in<strong>for</strong>mationcoming via SMS is usually not seen as credible. Use of cell phones, where available,might be used more effectively to update <strong>and</strong> coordinate field workers <strong>and</strong> socialmobilization partners. The use of multiple channels is important <strong>for</strong> effectivecommunication, but keeping ef<strong>for</strong>ts coordinated <strong>and</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mation consistent acrosschannels is a major challenge during p<strong>and</strong>emic response. Advanced planning <strong>and</strong> anactive national communication coordination body will help to minimize confusion.Advocacy: During the response to the p<strong>and</strong>emic, advocacy can be used withvarious ministries outside of health (<strong>for</strong> example, education, child welfare, tourism) toengage them in policy decisions at the national level to help reduce transmission <strong>and</strong>mitigate the social <strong>and</strong> economic impact. Examples of such policy decisions includewhether to screen passengers at airports <strong>and</strong> place other restrictions on travel; <strong>and</strong>whether to use school closure or class dismissal as public health measures. Additionaladvocacy ef<strong>for</strong>ts may be needed to convince non-traditional partners, such as privatesector organizations <strong>and</strong> businesses, that they have a stake in p<strong>and</strong>emic response.For example, factory owners, the private education system, <strong>and</strong> agri-business can becalled upon to adjust temporarily their employment policies regarding absenteeism.(See “Desired <strong>and</strong> Feasible <strong>Behavior</strong>s” to see how policy change can help makedesired behaviors more do-able <strong>for</strong> individuals.) All organizations should be urgedto adopt business continuity measures, but this is especially important <strong>for</strong> thoseorganizations providing essential services to the public.Advocacy at the sub-national levels is also critical <strong>for</strong> coordinated planning <strong>and</strong>implementation to reach to the community level. In large countries or those withdecentralized political systems, provincial/district authorities may be called uponto develop their own preparedness <strong>and</strong> response plans. At the very least, localauthorities need to be oriented on the government’s response plan so that theycan guide implementation in their area <strong>and</strong> communicate to their constituents inharmony with national decisions. Coordination of social mobilization <strong>and</strong> othercommunity-level initiatives to reduce transmission might also rest with sub-nationalcommunication teams. There<strong>for</strong>e, national communication planners should engagerepresentatives of key sub-national levels to develop realistic implementation plans.Partners <strong>for</strong> socialmobilization: Be<strong>for</strong>e anoutbreak occurs, a few keygroups should be selected<strong>and</strong> agreements made abouthow they will be used <strong>for</strong>communication during thep<strong>and</strong>emic response. Civilsociety organizations, religious<strong>and</strong> community leaders, privatesector health providers <strong>and</strong>Be<strong>for</strong>e an outbreak, enlist the support of:• Civil society organizations <strong>and</strong> NGOs• Religious <strong>and</strong> community leaders• Private health providers <strong>and</strong> pharmacists• Major employers <strong>and</strong> private industries• Networks such as teachers <strong>and</strong> studentpeer groups17

pharmacists, major employers, NGOs <strong>and</strong> other development agencies are someof the partners to mobilize during the p<strong>and</strong>emic to reach out to people at thecommunity level. Existing networks outside of the health sector can also be importantpartners in communication. These may include hygiene promoters in water <strong>and</strong>sanitation programs, community catalysts/mobilizers, agricultural extension workers,micro-credit groups, educational networks such as teachers, administrators, <strong>and</strong>student peer groups, <strong>and</strong> village development committees. One country successfullyengaged herbal medicine vendors in rural markets to transmit prevention messagesto their clients.It is particularly important to find groups which can reach <strong>and</strong> are credible to someof the minorities, socially marginalized <strong>and</strong> other participant groups identified in thecommunication strategy.To assure that these groups communicate correct in<strong>for</strong>mation effectively, speciallyadaptedmaterials <strong>and</strong> orientation to their use will be important components of thecommunication plan. A monitoring plan that includes tracking how mobilizers are todeliver messages as the p<strong>and</strong>emic unfolds will be important to harmonize messages,minimize the spread of rumors, <strong>and</strong> maintain morale. Two-way communicationbetween mobilizers <strong>and</strong> their field supervisor/leader should be agreed upon. Forexample, planners could explore the use of regular contact by mobile phone.<strong>Behavior</strong> change communication (BCC): <strong>Behavior</strong> change communicationfocuses on individuals <strong>and</strong> their behavior. This guidance focuses on BCC <strong>and</strong> how itis effectively combined with other communication approaches to support p<strong>and</strong>emicresponse. Specifically, the role of BCC during the p<strong>and</strong>emic is to in<strong>for</strong>m <strong>and</strong>motivate individuals to adopt the behaviors recommended to prevent contracting theH1N1 virus, limit its spread to others <strong>and</strong> to promote home care of the sick. Thesemessages to individuals are spread through various channels which were describedabove. One effective way to motivate individuals is to engage popular <strong>and</strong> trustedpersonalities in addition to the official government spokespersons as sources ofin<strong>for</strong>mation.Using a combination of mass media, interpersonal communication <strong>and</strong> traditionalmedia will increase the effectiveness of messages to different participant groups.Examples of the kinds of materials <strong>and</strong> messages focusing on the individual <strong>and</strong> whathe/she should do during the p<strong>and</strong>emic can be found on these (among other) websites: www.p<strong>and</strong>emicpreparedness.org <strong>and</strong> www.influenzaresources.org.Risk/outbreak communication: As stated earlier, this is the term used <strong>for</strong> thecommunication between health <strong>and</strong> government authorities <strong>and</strong> the population of acountry in a p<strong>and</strong>emic situation be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>and</strong> in response to an outbreak in that country.It is well documented that when government <strong>and</strong> other authorities are transparentby providing timely <strong>and</strong> correct in<strong>for</strong>mation to the population, their ef<strong>for</strong>ts to reducetransmission <strong>and</strong> mitigate the impact of the p<strong>and</strong>emic are more successful. Effectiverisk communication, however, takes planning <strong>and</strong> capacity building, including:• Identification <strong>and</strong> training of spokespersons from government <strong>and</strong> otherselected agencies—<strong>for</strong> coordination <strong>and</strong> consistent messaging18

• Media training <strong>and</strong> continued orientation—<strong>for</strong> in<strong>for</strong>med <strong>and</strong> balanced reporting• During response: regular updates to the public from authorities via mass media;maintenance of quality websites <strong>and</strong> other in<strong>for</strong>mation sources; regular updatesto hard-to-reach groups via pre-arranged communication channels; monitoring<strong>for</strong> reach <strong>and</strong> rumors.Research <strong>and</strong> monitoring: Research during planning is important to underst<strong>and</strong>participant groups’ perceptions of risk<strong>and</strong> feasibility of protective behaviors<strong>and</strong> to prepare/adapt messages<strong>and</strong> materials. Because of the timeconstraint, planners should use existingdata sources as much as possible. Forexample, Demographic <strong>and</strong> HealthSurveys (DHS), carried out in manycountries, contain useful descriptivein<strong>for</strong>mation about households <strong>and</strong>communities which can help in<strong>for</strong>mthe design of actionable messages <strong>and</strong>identify the most effective channels<strong>for</strong> communication. Previous researchconducted <strong>for</strong> avian influenza, childsurvival, nutrition, personal hygiene,child protection, HIV/AIDS prevention,etc. that emphasized social <strong>and</strong>cultural determinants are good sources of evidence to help make the p<strong>and</strong>emiccommunication more strategic.If resources <strong>for</strong> research <strong>and</strong> monitoringare limited, focus on• existing sources of in<strong>for</strong>mation (such ashousehold surveys)• <strong>for</strong>mative research to underst<strong>and</strong>perceptions of risk <strong>and</strong> feasibility ofprotective behaviors <strong>and</strong>• pre-testing of communication products<strong>and</strong> messages• monitoring the reach of communicationchannels to key participant groupsGiven likely resource constraints, it may not be possible or essential to carry outquantitative baseline surveys about knowledge, attitudes, <strong>and</strong> behaviors specificallyrelating to p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza. While it would be desirable to have this in<strong>for</strong>mation inorder to measure the effectiveness of communication activities, it is likely to be moreuseful if the limited resources available are applied to pre-testing <strong>and</strong> monitoringactivities, as described below.Pre-testing: All communication products, including the feasibility of recommendedbehaviors, need to be pre-tested in a systematic way with the intended participantgroup. Taking time <strong>and</strong> resources to test messages <strong>and</strong> materials <strong>for</strong> comprehension<strong>and</strong> acceptability with communities be<strong>for</strong>e being approved by governmentauthorities/communication committees will be more effective in achievingcommunication objectives. If possible, negotiate a contract in advance with a localresearch firm, experienced in communication pre-testing, so that it can be rapidlydeployed when the communication messages <strong>and</strong> materials are ready.Monitoring plans do not need to be extensive. They should match the level of ef<strong>for</strong>tdevoted to p<strong>and</strong>emic-specific communication. Basically, the reach of communicationthrough the most heavily-used channels (including the deployment of socialmobilizers) should be monitored frequently during response—especially to trackef<strong>for</strong>ts to reach socially marginalized <strong>and</strong> hard-to-reach populations. Proxy indicators19

FIGURE 1LEVELS PARTICIPANT* ACTIONSNationalP<strong>and</strong>emicCoordinationbody, <strong>Communication</strong>Task Force, donors,private sector, nationalmedia, development partnersAdvocacy <strong>for</strong> government transparency <strong>and</strong> appropriate policy decisions; rights ofmarginalized groups protected; continuous work through national coordination bodies tosupport p<strong>and</strong>emic response; resources allocated <strong>for</strong> communication; strategy <strong>and</strong>materials developed; authorities <strong>and</strong> media trained in risk communication; use of massmedia; collection, analysis <strong>and</strong> use of research <strong>and</strong> monitoring dataSub-nationalDistrict, municipality, etc.Local government officials, districtMOH/MOE team, NGOs, hospitaladministration, border authoritiesLocal level advocacy <strong>for</strong> transparency <strong>and</strong> coordination of communication<strong>and</strong> public health response; harmonize messages; leadership trained in riskcommunication; social mobilizationHealth facilityHealth providers (public, private & faith based)Through IPC, use harmonized messages about reducingtransmission <strong>and</strong> providing home care.CommunityCSOs, community <strong>and</strong> religious leaders, women’s groups,CHWs, teachers/school committees, youth groupsUse traditional media, social mobilization, BCC incommunity <strong>and</strong> schools to reduce transmission,facilitate home care <strong>and</strong> social support.Household &IndividualParents, adult care-givers, adolescents, other household members, childrenPractice behaviors <strong>for</strong> home care,to reduce transmission, <strong>and</strong>mitigate social impact.* Participants are decision makers <strong>and</strong> stakeholders who need to take the actions described.BCC – behavior change communicationCHWs – community health workersCSOs – civil society organizationsMOH – Ministry of HealthMOE – Ministry of EducationNGO – nongovernmental organization20

Suggested resource materialsThe Humanitarian P<strong>and</strong>emic Preparedness (H2P) Initiative, UNICEF, <strong>and</strong> their partnershave worked closely with WHO <strong>and</strong> other public health agencies to develop a rangeof guidance documents <strong>and</strong> communication materials. These agencies <strong>and</strong> othersmaintain websites with specific links to the H1N1 p<strong>and</strong>emic. As these sites continueto evolve <strong>and</strong> additional resource materials are made available, readers are advised tocheck the websites listed below on a periodic basis.World Health Organization website <strong>for</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic H1N1 (2009) influenza:http://www.who.int/csr/disease/swineflu/en/index.htmlMulti-agency link <strong>for</strong> avian <strong>and</strong> p<strong>and</strong>emic communication resources:www.influenzaresources.orgH2P link <strong>for</strong> communication resources:www.p<strong>and</strong>emicpreparedness.orgUseful resource documents include the following:Behavioural interventions <strong>for</strong> reducing the transmission <strong>and</strong> impact of influenzaA(H1N1) virus: a framework <strong>for</strong> communication strategies (WHO/UNICEF, June2009). Available at:http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/framework_20090626_en.pdfDrawing Attention to P<strong>and</strong>emic Influenza through Advocacy. March 2009.Available at: http://avianflu.aed.org/globalpreparedness.htmEssentials <strong>for</strong> Excellence: Researching, Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Evaluating Strategic<strong>Communication</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Behavior</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Social</strong> <strong>Change</strong> with special reference to theprevention <strong>and</strong> control of avian influenza/p<strong>and</strong>emic influenza (2008). Available at:http://www.unicef.org/cbsc/files/Essentials_<strong>for</strong>_excellence.pdfGlobal Preparedness <strong>for</strong> P<strong>and</strong>emic Flu – Advocacy Kit. Available at:http://avianflu.aed.org/globalpreparedness.htm“Spreading the Word: Preventive Messages about Flu”. Training module <strong>for</strong>community health responders. Available on the H2P Website or on the COREGroup website at: www.coregroup.org/h2pWHO Outbreak <strong>Communication</strong> Guide, 2008http://www.who.int/ihr/elibrary/WHOOutbreakCommsPlanngGuide.pdf“Terms of reference <strong>for</strong> a national Avian <strong>and</strong> P<strong>and</strong>emic <strong>Communication</strong> task <strong>for</strong>ce”www.influenzaresources.org22