03-1 Pastoral Care.pdf

03-1 Pastoral Care.pdf

03-1 Pastoral Care.pdf

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

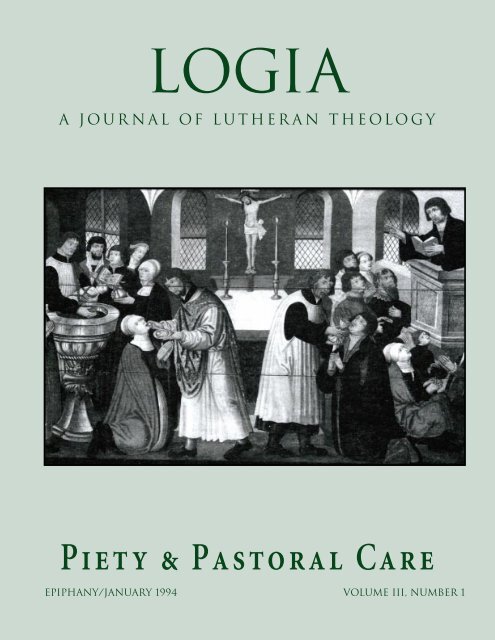

Logiaa journal of lutheran theologyPIETY & PASTORAL CAREEpiphany/january 1994 volume IIi, number 1

ei[ ti" lalei',wJ" lovgia Qeou'logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes articleson exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theology that promotethe orthodox theology of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. We cling toGod’s divinely instituted marks of the church: the gospel, preached purelyin all its articles, and the sacraments, administered according toChrist’s institution. This name expresses what this journal wants to be. InGreek, LOGIA functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,”“learned,” or “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,”“words,” or “messages.” The word is found in 1 Peter 4:11, Acts7:38 and Romans 3:2. Its compound forms include oJmologiva (confession),ajpologiva (defense), and ajvnalogiva (right relationship). Each ofthese concepts and all of them together express the purpose and methodof this journal. LOGIA is committed to providing an independent theologicalforum normed by the prophetic and apostolic Scriptures and theLutheran Confessions. At the heart of our journal we want our readers tofind a love for the sacred Scriptures as the very Word of God, not merelyas rule and norm, but especially as Spirit, truth, and life which revealsHim who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life—Jesus Christ our Lord.Therefore, we confess the church, without apology and without rancor,only with a sincere and fervent love for the precious Bride of Christ, theholy Christian church, “the mother that begets and bears every Christianthrough the Word of God,” as Martin Luther says in the Large Catechism(LC II, 42). We are animated by the conviction that the EvangelicalChurch of the Augsburg Confession represents the true expression ofthe church which we confess as one, holy, catholic, and apostolic.THE COVER ART is a photograph of the antemesale from TrorslundeChurch. Photograph supplied by National Museum, Copenhagen.EDITORSMichael J. Albrecht, Copy Editor—Pastor, St. James Lutheran Church,West St. Paul, MNJoel A. Brondos, Logia Forum and Correspondence Editor—Pastor,St. John Lutheran Church, Vincennes, INCharles Cortright, Editorial Associate—Pastor, Our Savior’s LutheranChurch, East Brunswick, NJScott Murray, Editorial Associate—Pastor, Salem Lutheran Church,Gretna, LAJohn Pless, Book Review Editor—Pastor, University Lutheran Chapel,Minneapolis, MNTom Rank, Editorial Associate—Pastor, Scarville Lutheran Church,Scarville, IAErling Teigen, Editorial Coordinator—Professor, Bethany LutheranCollege, Mankato, MNJon D. Vieker, Editorial Associate—Pastor, St. Mark’s LutheranChurch, West Bloomfield, MISUPPORT STAFFBrent W. Kuhlman, Development Manager—Pastor, Faith LutheranChurch, Hebron, NEPatricia Ludwig, Layout and Design—Cresbard, South DakotaTimothy A. Rossow, Subscription Manager—Pastor, Bethany LutheranChurch, Naperville, ILLäna Schurb, Proofreader—Ypsilanti, MIRodney E. Zwonitzer, Advertising Manager—Pastor, EmmanuelLutheran Church, Dearborn, MICONTRIBUTING EDITORSUlrich Asendorf—Pastor, Hannover, GermanyBurnell F. Eckardt, Jr.—Pastor, St. John Lutheran Church, Berlin, WICharles Evanson—Pastor, Redeemer Lutheran Church, Fort Wayne, INRonald Feuerhahn—Professor, Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MOLowell Green—Professor, State University of New York at Buffalo, NYPaul Grime—Pastor, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, West Allis, WIDavid A. Gustafson—Pastor, Peace Lutheran Church, Poplar, WITom G.A. Hardt—Pastor, St. Martin’s Lutheran Church, Stockholm, SwedenMatthew Harrison—Pastor, St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, Westgate, IASteven Hein—Professor, Concordia University, River Forest, ILHorace Hummel—Professor, Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MOArthur Just—Professor, Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, INJohn Kleinig—Professor, Luther Seminary, North Adelaide,South Australia, AustraliaArnold J. Koelpin—Professor, Dr. Martin Luther College, New Ulm, MNLars Koen—Uppsala University, Uppsala, SwedenGerald Krispin—Professor, Concordia College, Edmonton, Alberta,CanadaPeter K. Lange—Pastor, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Concordia, MOCameron MacKenzie—Professor, Concordia Theological Seminary, FortWayne, INGottfried Martens—Pastor, St. Mary’s Lutheran Church, Berlin, GermanyKurt Marquart—Professor, Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, INNorman E. Nagel—Professor, Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MOMartin Noland—Pastor, Christ Lutheran Church, Oak Park, ILWilhelm Petersen—President, Bethany Seminary, Mankato, MNHans-Lutz Poetsch—Pastor Emeritus, Lutheran Hour, Berlin, GermanyRobert D. Preus—Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, INClarence Priebbenow—Pastor, Trinity Lutheran Church, Oakey,Queensland, AustraliaRichard Resch—Kantor, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Fort Wayne, INDavid P. Scaer—Professor, Concordia Theological Seminary,Fort Wayne, INRobert Schaibley—Pastor, Zion Lutheran Church, Fort Wayne, INBruce Schuchard—Pastor, St. James Lutheran Church, Victor, IAKen Schurb—Professor, Concordia College, Ann Arbor, MIHarold Senkbeil—Pastor, Elm Grove Lutheran Church, Elm Grove, WICarl P.E. Springer—Professor, Illinois State University, Normal, ILJohn Stephenson—Professor, Concordia Seminary, St. Catharines,Ontario, CanadaWalter Sundberg—Professor, Luther Northwestern TheologicalSeminary, St. Paul, MNDavid Jay Webber—Pastor, Trinity Lutheran Church, Brewster, MAWilliam Weinrich—Professor, Concordia Theological Seminary,Fort Wayne, INGeorge F. Wollenburg—President, Montana District LCMS, Billings, MTLOGIA (ISSN #1064‒<strong>03</strong>98) is published quarterly by the Luther Academy, 2829 Fox Chase Run,Fort Wayne, IN 46825‒3985. Second class postage paid (permit pending) at Dearborn, MI and additionalmailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to LOGIA, 800 S. Military, Dearborn,MI 48124. Editorial Department: 1004 Plum St., Mankato, MN 56001. Unsolicited material is welcomedbut cannot be returned unless accompanied by sufficient return postage. Book ReviewDepartment: 1101 University Avenue SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414. All books received will be listed.Logia Forum and Correspondence Department: 707 N. Eighth St., Vincennes, IN 47591‒1909.Letters selected for publication are subject to editorial modification, must be typed or computerprinted, and must contain the writer’s name and complete address. Subscription & AdvertisingDepartment: 800 S. Military, Dearborn, MI 48124. Advertising rates and specifications are availableupon request.SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: U.S.: $18 for one year (four issues); $36 for two years (eightissues). Canada and Mexico: 1 year, $25; 2 years, $50. Overseas: 1 year, air: $35; surface: $25; 2 years,air: $70; surface: $50. All funds in U.S. currency only.Copyright © 1993. The Luther Academy. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may bereproduced without written permission.

logiaa journal of lutheran theologyEpiphany/January 1994 volume III, number 1CONTENTSCORRESPONDENCE....................................................................................................................................................................................2ARTICLESThe Outer Limits of a Lutheran PietyBy Steven A. Hein.............................................................................................................................................................................................................4Conditional Forgiveness and the Translation of 1 John 1:9By John M. Moe...............................................................................................................................................................................................................11Preaching to Preachers: Isaiah 6:1–8By Donald Moldstad .......................................................................................................................................................................................................131 Corinthians 11:29 — “Discerning the Body” and Its Implications for Closed CommunionBy Ernie V. Lassman ......................................................................................................................................................................................................15Using the Third Use: Formula of Concord VI and the Preacher’s TaskBy Jonathan G. Lange .....................................................................................................................................................................................................19The Law and the Gospel in Lutheran TheologyBy David P. Scaer ............................................................................................................................................................................................................27Angels UnawareBy Paul R. Harris .............................................................................................................................................................................................................35A Call for Manuscripts...................................................................................................................................................................................................42Only Playing Church? The Lay Minister and The Lord’s SupperBy Douglas Fusselman ...................................................................................................................................................................................................43COLLOQUIUM FRATRUM...................................................................................................................................................................52David Scaer: A Reply to Leonard KleinREVIEWS .................................................................................................................................................................................................................55REVIEW ESSAY : Translating the Bible: An Evaluation of the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).<strong>Pastoral</strong> <strong>Care</strong> and the Means of Grace. By Ralph UnderwoodA Common Calling: The Witness of Our Reformation Churches in North America Today. Ed. by Keith F. Nickle and Timothy F. LullOne Ministry Many Roles: Deacons and Deaconesses through the Centuries. By Jeannine E. OlsonMessianic Exegesis: Christological Interpretation of the Old Testament in Early Christianity. By Donald JuelBRIEFLY NOTEDLOGIA FORUM................................................................................................................................................................................................64Pastor, Couldn’t We ...? • Demand and Delight • Too Much to Read? • The Common PriesthoodFearful Proof • Uppsala Colloquy + 400 • The Once and Future ChurchProfiles in Ministry • ynod X and Synod Y • Gladly in the Midst • Resourcing the ResourceConfessional Stewardship • A House Dividing? Reflections on GCC ’93Doctrine and Practice • Shared Voices / Different Vision

CORRESPONDENCETou;" ajnqrwvpou" AND ejnanqrwphsavntaIN THE NICENE CREED■ I should like to add some commentson the article “Creedal Catholicity”(LOGIA, Forum, Eastertide/April 1993p. 59). In Australia the churches have alsostudied the problem of the ejnanqrwphsavntaand reckoned with the suggestionsof the international committees.While the Anglicans, Catholics and UnitingChurch have chosen to use “becamefully human,” the Lutherans preferred“became a human being.” Admittedly,this does not overcome Weinrich’sobjection that the masculinity of Christ isbeing overlooked, but it does go furtherin establishing the historical reality of thehuman nature of Christ.However, there is a more subtlereason for the “human being,” and thisseems to have been missed by bothPrange and Weinrich. It is the significanceof the tou;" ajnqrwvpou" at thebeginning of the sentence. Here theWELS Commission has followed therecommendation of the internationalcommittees, and simply omitted thetou;" ajnqrwvpou": “for us men and forour salvation.” However, if the Greek isset out in strophe form (I use BishopGoodwin’s version), it is noticeable thatwe have here a significant rhetoricalconstruction:To;n di∆ hJma'ı tou;" ajnqrwvpou"kai; dia; th;n hJmetevran swthrivan,katelqovnta ejk tw'n oujranw'nkai; sarkwqevnta,ejk Pneuvmato" aJgivou kai; Mariva" th'"Parqevnou,kai; ejnanqrwphsavnta:The Nicene fathers are balancingthe tou;" ajnqrwvpou" with the ejnanqrwphsavnta.In other words, if we followthe recommendation of the internationalcommittees, we have a sort ofincomplete chiasmus: a … , … a insteadof a …b, b…a. The writers are makingthe weighty point that for us “humanbeings” he became “a human being,”and they draw our attention to the factby a trope. Greek theology has alwayskept Romans 5:12 and following insight, and the Orthodox have continuallyreminded us of the words of Gregoryof Nazianzus: to; aprovslhptonajqeravpeuton. Unfortuantely, the newtranslation glides over the significantrhetoric of the original.As Professor Hartwig pointed out,there is good reason for abiding by a“common” text. For this reason, theLutheran Church of Australia has used“for us and for our salvation,” but it hasadded a footnote: “for us humanbeings.” In this way, if only in a footnote,the balance has been kept with“became a human being.”To press the case for the tou;"ajnqrwvpou" might seem like specialpleading. However, two points should bekept in mind. First, scholars have arguedthat the earliest drafts of the NiceneCreed contained only the kai; sarkwqevntawhich would have been sufficient toestablish the humanity of Christ if thishad been the only concern of the confessors.The ejnanqrwphsavnta was added inorder to say something more, and it canonly be properly understood if it is keptin tandem with the tou;" ajnqrwvpou".Secondly, there is the evidence ofthe Definition of Chalcedon. In line 14,2(following the numbering of Ortez deUrbina), we have the only quotation ofthe Nicene Creed: To;n aujto;n di∆ hJma'"kai; dia; th;n hJmetevranswthrivan. Herethe tou;" ajnqrwvpou" is omitted becausethere is no rhetorical correspondencewith a following ejnanqrwphsavnta.P. Koehne261 Koroit St.Warrnambool, Australia 3280RESPONSE TO DAVID SCAER■ It’s always fun to watch David Scaershooting from the hip, especially when hehits a target, but I am having difficultyidentifying this Klein that he is aiming formore or less in “The Integrity of the ChristologicalCharacter of the Office of theMinistry” [LOGIA, Vol. 2, No. 1].He says, for instance, that “all referencesto God including Father and Son aremetaphorical.” Well, yes, insofar as theyare. To the degree that the ordinary Englishmeaning of father is sexual begetter ofchildren (like Scaer or Klein) and son isthe male offspring of such a father, there isa difference between the use of Father forGod and our use of father for some males.To admit to the metaphorical character ofthis language is not the same as to grantthe arguments of Gnostic deconstructionists,who, in any event, can hardly be heldoff with a claim that all God language issimply univocal. Of course the first twopersons of the Trinity are Father and Son,but not in the same manner as Roy andLeonard Klein or Leonard and NicholasKlein. This is easy and it’s not heretical.

CORRESPONDENCE 3Then we learn that Klein derivesthe office of the ministry from baptism!This would surprise and please many ofhis opponents in the ELCA who findhim—with some reason—a rankRomanist. But Klein has never believedthis. What could he have said to makeScaer think so?It was probably that Klein said thatthe baptism of women is not withoutbearing on the question of women’sordination. Klein expressed at FortWayne some concern that when someMissourians appeal to the ministry’scharacter as representative of Christ inarguing against the ordination ofwomen—a point that is not withoutsome merit—they argue it with a ferocityapproaching misogyny, a ferocity thatseems to overlook that, in virtue of theirbaptism, women already representChrist. Klein would never accept thenaíve use of “neither male nor female” asa sufficient argument for women’s ordination.By the same token he will notgrant that the maleness of Christ and themaleness of the clergy until very recenttimes in some places is a sufficient argumentagainst ordaining women. Themuddling of a metaphor that leads Scaerand some others simplistically to say“woman at the altar; woman on thethrone” is as invalid as the liberal muddlingof metaphor to relativize God’srevelation of himself as Father and Son.The irony of Scaer’s misunderstandingof Klein is that it overlooks Klein’spleasure that Missouri—even if only tokeep women out of the ministry—isfinally being forced to re-evaluate its traditionalfunctionalism. Klein in factagrees with Scaer that the minister representsChrist. While holding that thechurch may in evangelical freedom callwomen to that ministry, he believes thatthe issue is not beyond debate and thatthe question of representation is a legitimatepart of that debate. Klein simplythinks that the question is far more intricatethan Scaer allows. And he does notat all think some of the things Scaerattributes to him.The Rev. Leonard R. KleinChrist Lutheran ChurchYork, PALOGIA CORRESPONDENCE ANDCOLLOQUIUM FRATRUMWe encourage our readers to respond tothe material they find in LOGIA—whetherit be in the articles, book reviews or lettersof other readers. Some of your suggestionshave already been taken to heart as weconsider the readability of everything fromthe typeface and line spacing (leading) tothe content and length of articles. Whilewe cannot print everything that comesacross our desks, we hope that our newCOLLOQUIUM FRATRUM section will allowfor longer response/counter-responseexchanges, whereas ourCORRESPONDENCE section is a place forshorter “Letters to the Editors.”If you wish to respond to something in anissue of LOGIA, please do so soon after youreceive an issue. Since LOGIA is a quarterlyperiodical, we are often meeting deadlinesfor the subsequent issue about the timeyou receive your current issue. Gettingyour responses in early will help keepthem timely. Send your CORRESPONDENCEcontributions to: LOGIA Correspondence,707 N. Eighth St., Vincennes, IN 47591-3111, or your COLLOQUIUM FRATRUM contributionsto LOGIA Editorial Department,1004 Plum St., Mankato, MN 56001.

The Outer Limits of a Lutheran PietySTEVEN A. HEIN“Lutherans are remarkably unremarkable.”THIS IS CHURCH HISTORIAN MARK NOLL’S ASSESSMENT OFLutherans in America in a recent essay entitled “TheLutheran Difference.” 1 From the standpoint of makingany particular impression on American culture, or being able todescribe something unique about a “Lutheran ethos or piety,”Mark Noll observes that from the angle of social scientists, onefails to find anything that manifests itself as particularly distinctive.Lutheran religious life in America has seemed rather unobtrusive.“Beyond their instructive experience as immigrants,”Noll opines, “it is hard to isolate identifiably Lutheran contributionsto the larger history of Christianity in America.” 2 Whenit comes to the subject of piety and its impact on society in general,Lutherans seem to be extraordinarily ordinary.While this evaluation may cause consternation and alarmwithin some circles of those who wish to identify with thename Lutheran, I do not believe that protests should belaunched too loudly from those whose confession embraces thesubstance of Luther’s Theology of the Cross. From this perspective,there are good reasons to embrace the conclusion thatthe good pious Christian called to live by the cross of Christ is,and remains in this life, a bit of a phantom, a sociologicaluncertainty. Indeed, it is the intention of this essay to sketch aportrait of true Christian piety as one which usually rendersthe individual believer indistinguishable from the average citizensof this world. Godliness involves a call to faith and faithfulnesswith a distinctive worldly accent.The life of the individual believer gives expression to whoand what Christians are by the assessment of God’s judgmentof law and gospel. As such, the Christian is, as Luther paradoxicallymaintained, “righteous and beloved by God, and yet. . . a sinner at the same time.” 3 Let’s examine this moreclosely. As the Christian lives in the flesh, he stands under thejudgment of law as a sinner. The law presents all sinners inthis life a security and a peril. Outwardly, the law presents thisfallen world with the security of social orders—the structuresABOUT THE AUTHORSTEVEN A. HEIN teaches religion at Concordia University, River Forest,Illinois, and is a contributing editor of LOGIA.4of community by which temporal life is ordered. Moreover, areasonable application of the law provides a modicum of temporalsecurity for peaceful relations among the social orders ofthe world. This civic use of law boils down to a reasonableapplication of the Golden Rule: life will go well for me, if Itreat others as I would have them treat me. 4 Such behavior,however, does not make the believer extraordinary or unusual.Civic righteousness neither makes the believer pious, nordoes it focus on the essential nature of the expression ofChristian piety. Common to believer and unbeliever alike, it isrooted in self-interest. Civic righteousness is not intrinsicallythe stuff of godliness; it is the stuff of practical wisdom.Spiritually speaking however, the law presents a peril. Itpronounces all mankind sinners and threatens all sinners withthe sentence of death. Through the law, God produces selfhonestyand contrition. But for the believer, the law is onlyGod’s preliminary word, his provisional judgment, not hisfinal judgment. God’s judgment of grace is his final verdict thatsets us free. “The law was given through Moses; grace and truthcame through Jesus Christ” (Jn 1:17). This is the word of truthabout our identity that proclaims us saints—holy, righteous,pious ones; this is the truth that embodies all our godliness andsets us free.It is the righteousness of Christ bestowed by God’s graciousword that declares the Christian good and holy in God’ssight. In Christian baptism, God has declared the Christianpious. True piety or holiness is essentially a hidden possessionof the Christian, not a demonstrable attribute, nor a bundle ofsome uniquely pious activities. On the demonstrable side ofthings, the Christian is and remains an impious sinner in character,in word, and deed. And about this seeming nonsense,Luther rhetorically asked,Who will reconcile these utterly conflicting statements,that the sin in us is not sin, that he who is damnablewill not be damned, that he who is rejected will not berejected, that he who is worthy of wrath and eternaldeath will not receive these punishments? Only themediator between God and man, Jesus Christ. 5The law judges what we are in this fallen creation, thegospel who we are in Christ. And how does God require us to

THE OUTER LIMITS OF A LUTHERAN PIETY 5swallow such “nonsense” and be obedient to it? Through faith!For this reason, the essential expression of the Christian’s pietyis subjective in character; it is faith in the heart, and hence it ishidden. The expression of true piety and godliness in the Theologyof the Cross is the obedience of faith and the expression offaithfulness. The outer limits of Christian piety, what the Christianis and what the Christian does, are tied to the call of God.This call causes the individual Christian to live a “provisional”life in this old fallen creation that can, indeed, merit the estimationof being “extraordinarily ordinary.” To appreciate this, andsurvey briefly the alternatives to this stance, we must explorethe concept of Christian vocation. In the history of theology,the concept of true Christian piety and godliness has been tiedto an understanding of God’s call to faith and faithfulness.CHRISTIAN PIETY WITHIN THE VOCATIO OF GODLuther often used a special term to designate the Christianlife of faithfulness, “vocation.” The word vocation comes fromthe Latin term, vocatio. A vocatio is a call or calling to a givenway of life. It grants an individual a particular standing andposition in relation to others within a community. Moreover,it defines how one meaningfully participates in and contributesto the life of the community. In other words, our vocation tellsus who we are within life’s social structures and what kind ofduties we have for the welfare of the community; it demandsthat we live lives of faith and faithfulness. We must trust ourvocation to live securely as members of society, and our faith isexpressed, in part, by faithfully being about the tasks that comewith our particular station.Christian life is lived as a calling, a vocation that flowsfrom God’s call and love for us in Christ. Through the gospel,he has called us to be sons and daughters in his family. This callis first and foremost a summons to a life of faith, a call to trustin God and who and what we are by his grace: forgiven andadopted children of his love. Christians have received theirvocational call from God in baptism. Baptism bestows on eachof us God’s gracious claim to be his child. His call brings fulland secure membership in his kingdom. The task that God hasgiven to us is to act out our faith in his calling. This is themeans of expressing our faithfulness to him and his family.True piety expresses or acts out our trust in who we are byGod’s call. Vocatio forms pietas. Major questions about Christianvocation must be addressed. How and where in the worldshould we live and serve our God as his children? What are ourtasks? What should be our relationship with the citizens andsocial structures of the world? What do our attachments andcommitments to our family, our work, and our civic involvementhave to do with living out the call of God? The churchthrough the ages has grappled with these questions and providedquite a spectrum of responses.St. Augustine, the great thinker of the ancient church, setforth his vision of God’s call in his monumental work, The Cityof God. Augustine conceived of the church as a pilgrim people,citizens of another age who are journeying through life in thisworld to their real home, “the City of God.” The call to faith isa call to faithful living as we travel on our way to the eternalkingdom that God will usher in at the close of the age. Augustinesaw citizenship as an exclusive status. Therefore sincebelievers are citizens of God’s eternal kingdom, they inhabitthe social structures of this world as foreigners, sojourners ontheir way to their real home. During the journey, God schoolsand outfits his people for the coming age. This was Augustine’svision of what Jesus meant in his call for his disciples to be inthe world, but not of the world. We live in the world, but asforeigners—citizens of the kingdom that is not identified withany temporal community. Our days on earth are focused onGod’s gracious power, transforming us in holiness, making usfit for life in the kingdom.This vision of Christian vocation created for Augustine akind of ambivalence toward the social communities of thisworld. Christians are to live peaceably within them, butbecause they are fallen and will pass away with the dawning ofthe kingdom, we must see the call of God and the higher tasksof faithfulness as transcending our involvement in them. Truegodliness involves for the faithful Christian a higher life whichwe pursue over and above the obligations and commitmentsthat arise from our sojourning in the world’s communities.The responsibilities of old world living are not of the same stuffas the works within a calling to divine citizenship. The Christianpilgrim may have to be involved with the former, but truepietas, true godliness flowing from faith, issues a higher orderof duties that flow from divine citizenship. For Augustine, oneis either a citizen of this world, or the City of God—but notboth. His portrait of the pious expressions of faith involved anextraordinary set of tasks, largely entailing self-discipline andspiritual devotion which stood over and beyond the everydayduties that spring from our sojourning in the social orders ofthis world. Here within the ordinary of life is the extraordinary,and this is the true stuff of Christian piety.. . . our vocation tells us who we arewithin life’s social structures.If this is really what true Christian piety is all about, whynot simply separate from the entanglements of this world andpursue godliness full time? In the second and third centuries,some radical Christian thinkers had just such a plan in mind.They placed an extreme emphasis on the negative side of thecall of God to be “not of the world.” Influenced by Greek Stoicphilosophy, their conception of the call of Christ was a call tolive in seclusion, divorced from all human community. Guidedby this vision, they equated the call of God with a life of isolationand self-denial. Many believers went out into the desertand lived solitary lives in caves. For them, true Christian pietywas tied up with an ascetic life of self-denial. They maintaineda meager physical existence with just enough food and water tokeep themselves alive. They were “hermits for Christ” whodevoted themselves to reading the Scriptures, prayer and meditationwhile waiting for God to usher in the fullness of the

6 LOGIAkingdom. For them, the Christian life was certainly extraordinaryand remarkable.During the Middle Ages a variation of the hermit movementbecame the standard form for what was termed “thehigher calling” of God. Rather than caves with one hermit percave, Christians pursued the higher call of God by cloisteringthemselves in groups inside monasteries. As holy fraternities,monks and nuns dedicated themselves to a pious life of devotionto God, separated from all commitments and attachmentsto the social orders of this world. Again, the highest order oftrue godliness was depicted as a life of self-denial and seclusion.Poverty, celibacy and strict obedience to monastic orderwere seen as virtuous sacrifice, the epitome of faithfulness.Unencumbered by secular concerns, the believer could becomeabsorbed in a higher regimen of worship, prayer and meditation.Monasticism flourished in Western Christianity for morethan a thousand years as the exemplary form of Christian vocationand piety. It was a kind of synthesis of Augustine’s visionof Christian citizenship and the hermit movement. Christianshad a choice. They could be ordinary or extraordinary. Theycould live a life of mediocre piety, sojourning in the old worldcommunities, trying to do pious things on top of the time-consumingtasks of earthly maintenance. Or they could pursue themore godly life—the higher calling—and do the pious thingsof divine citizenship “full time” within monasticism.GOD’S CALL TO DUAL CITIZENSHIPWhile a young monk, Luther searched the Scriptures andrediscovered the centrality of the incarnation and the cross inthe call of God. As he developed his “Theology of the Cross” herecognized that God’s saving work and call involve a kind of“salvific worldliness” in his method. God chooses to enlistworldly elements and structures of his fallen creation as instrumentsor means to accomplish his saving purposes. Think for amoment of the whole cycle of events in the extended Joseph narrativefrom Genesis. The words “and the Lord was with Joseph”(Gn 39:23) signal for the reader that “in, with and under” all ofthe worldly and tragic events that happened to Joseph and hisbrothers, God was at work to graciously bless the family of Israel.Joseph knew with all of his senses that his brothers and otherswere at work for evil purposes, but by faith he recognized God’ssaving activity at work for good (Gn 45:5–8, 50:20).So also, in a more central way, with the Incarnation andthe cross. God takes up and hides himself in ordinary humanflesh. He then enlists earthly family life, the carpentry trade,and the political and religious movements of the day in the serviceof his saving work. He works out but hides his righteousnessand pardon for us in the grisly act of capital punishmentby crucifixion—a tragic political event. By sight, we apprehendhis chosen worldly instruments and events, but by faith we seethe glory of God revealed in his Son and our righteousnessacquired. To understand God at work in the world is to holdon to both what we see and what is given to faith. Neitherdimension is to be denied or omitted from the church’s faithand confession. In the incarnation and the cross God revealsthe ultimate expression of salvific worldliness where the extraordinarywork of God is tied to and hidden in the ordinaryevents of the fallen world. As Luther observed, “Man hides hisown things in order to conceal them; God hides his own thingsto reveal them.” 6We would like to suggest that salvific worldliness is alsohow we should understand the contours of Christian vocationand true Christian piety from within the Theology of the Cross.We have become a new creation in Christ and a temple of theHoly Spirit, but God has called us to a life of faith and faithfulnessin the flesh and blood of the old creation. This means thatChristian vocation calls us to be simultaneously members of thecommunities of this fallen world and citizens of the kingdom ofGod. Jesus carried out his call from the Father within the oldcreation communities of earthly family, work and the socialstructures of general society. So also must we who now live inChrist. Christian life and vocation involves a dual citizenship;an extraordinary membership in the kingdom of God and anordinary membership in the old creation communities andstructures of everyday life. The Christian’s citizenship involvesan extraordinary one within the ordinary one.Luther recognized that God’s savingwork and call involves a kind of“salvific worldliness.”It is important to see that on one level, faithfulness inChristian vocation involves being about the ordinary living outof our commitments and projects that arise from our membershipand specific station in our families, workplace and generalsociety. God’s call to a life of faith and faithfulness alwaystouches us within our space—where we live already. It doesnot demand that we go off and live in caves or separated communities.And on this level, the outward character of Christianlife is not radically different from the average citizen of thisworld. In this sense, it is decidedly ordinary. But in, with andunder this life, God is calling the believer to a life of faith andfaithfulness as citizens of his kingdom. The higher calling ofthe Christian is not a summons to some parallel state, separatedfrom our participation in our existing communities, butrather it is embedded within them. True Christian piety is theextraordinary life of faith and faithfulness in Christ. But it isthe obedience of extraordinary faith expressed in the ordinarylife. The pious expressions of subjective faith are tied to thecommon and often mundane tasks that flow from our oldworld citizenship. Here, our Lord calls us to express our faithin him and his righteousness by loving service within ourearthly communities and the responsibilities that arise fromour places within them. Our roles and commitments withinthese communities are the schooling by which our Lord teachesus how to live out our faith as his children.When faith serves even the least among us in the mostmundane of ways, we serve Christ and glorify our heavenlyFather. This latter dimension is hidden from the world, perceivedonly through the eyes of faith. When the Christian shop-

THE OUTER LIMITS OF A LUTHERAN PIETY 7keeper sweeps the sidewalk outside the store, the householderdoes the laundry, the parent helps his child with homework orthe Christian salesman offers quality service graciously out oftrust in Christ and love for those served, faithfulness to the callof God is rendered. Here is the essence of pious Christian living.Indeed, it is a glorious, wonderful faithfulness that glorifies Godand for which the heavenly hosts are praising God. Faithfulnessflows from a heart of faith and love as we are about the fullrange of duties and tasks that arise from our ordinary commitmentsin life. Christian living from faith to faithfulness in theworld, as with Christ and his saving work, are both extraordinarywhile hidden, and ordinary as revealed.We are indeed, as Augustine recognized, a pilgrim peopleon our way to our ultimate home in the coming age. We awaitthe coming of our King and the fullness of our calling as citizensof a new age, to dawn when he returns. Life here within our oldcreation communities is temporary and provisional. Our visionof our final calling is shadowy and vague. It is not yet clear whatwe shall become. For now, our Lord directs our attention andenergies to the tasks he has called us to be about here, as wehope in the life to come. On the whole they are not very spectacularor compelling in the eyes of the world. Perhaps we coulddescribe them in the words of Mark Noll: They are by and large“remarkably unremarkable.” Let us explore them more closely.THE TASKS OF FAITHFULNESSAs Luther worked out from the Scriptures his Theology ofthe Cross and its application to Christian vocation, he realizedthat the call of Christ to the cross was a call to freedom. Thegospel abolishes slavish obedience to the Law and excludes thecommandments of church authorities that have no clear basisin God’s Word. Two major essays written in 1520 express theessence of Luther’s thinking about the character of Christianvocation under the cross: “The Freedom of the Christian” andthe treatise “On Good Works.”In “The Freedom of the Christian,” Luther captured St.Paul’s central point in his letter to the Galatians that the gospelof Christ is the end of the law. Living in Christ’s righteousnessimparts a polarity of freedoms: There is a “freedom from” and a“freedom to” for the children of God in the gospel. We havefreedom from any and all slavish forms of obedience and fromthe curse of the law. And we have freedom to live a life of faithand walk in the power of the Spirit. For Luther this meant thatobedience to the law was replaced for the Christian with theobedience of faith. He wrote:Is not such a soul most obedient to God in all thingsby this faith? What commandment is there that suchobedience has not completely fulfilled? What morecomplete fulfillment is there than obedience in allthings? This obedience, however, is not rendered byworks, but by faith alone. 7Faith grants to the Christian a freedom from slavish selflove,and freedom to love others, secure in God’s love. Thebondage of ordering all our projects to achieve self-justificationhas come to an end. The call of the gospel is not a summons todeny or denigrate self-love, nor does it forbid us our own commitmentsand projects in life. Rather, the righteousness of Christis the fulfillment of self-love in God’s love. Self-love may take abackseat and rest in the freedom and security of being “OK.” Sindistorted our loves by placing the self at the center and forefrontof life’s priorities. But now, secure in the verdict of the cross, theclaim of Christ calls forth a reordering of our loves that sin hasperverted, back to an expression of God’s original intention. Thefaith through which we are justified is expressed—it is acted outin life—through our loves as God originally ordered them.Faithfulness in Christian vocation is faith’s activity in love. As anew creation in Christ, the freedom of the Christian is hearingGod now address us with the following question: “What wouldyou like to do, now that you don’t have to do anything?’’ 8. . . the righteousness of Christ is thefulfillment of self-love in God’s love.Luther’s second writing, his treatise “On Good Works,” islargely an extended exposition on each of the Ten Commandments.It was a forerunner to the first chief part of his catechismswhich he wrote eight years later. Luther recognized thatthe commandments of God are a comprehensive summary ofthe law—the law which always unmasks our sinfulness andreveals God’s judgment. Yet Luther also recognized that thesecommandments also express all that the Christian needs toknow from God about good and God-pleasing works.He realized that the commandments sketch out both thecontext of where Christian vocation is to be lived, and theorder of our loves as God would have faith in Christ expressthem. Good works are not some extraordinary deeds that wetake time out from ordinary life to perform. Nor are theyexpressions about some intrinsic value of a life of self-denial.Rather, the commandments describe the natural outworking offaith in the everyday affairs of daily living in our families, workand community. Indeed, the commandments presuppose livinglife in these social orders of the old creation.The first table of the commandments presupposes that allhuman living flows from a personal involvement of the holyGod in our lives. He created us; he graciously preserves us; anddaily he provides for all our needs. The Fourth Commandmenttakes for granted that we live in the context of family and ageneral society of others ordered by the structures of government.The Fifth Commandment presumes interaction withothers that can affect bodily welfare. The Sixth Commandmenttakes for granted sexual contact and the community of husbandand wife in marriage. The Seventh, Ninth and TenthCommandments presume private possessions, and some kindof appropriate exchange of goods and services. The EighthCommandment reflects the reality that we touch and interactwith one another through communication. The commandmentsreflect the interpersonal character of how we live, workand carry on our ordinary projects of life.

8 LOGIAThe greatest insight of Luther in his treatise, however, washis recognition of the primacy and all-embracing thrust of theFirst Commandment. First, this means that we must approachall of our tasks and commitments in life from the perspectiveof “fear, love and trust in God.” Indeed, we are to orient ourwhole being within such a relation to God. Secondly, Lutherrecognized that the First Commandment is embedded in allthe others. All doing that includes the concerns raised in theremainder of the commandments Luther understood as a“doing of faith.” He called this a theological sense of doingrather than a moral sense of doing. To this point he wrote:In theology, therefore, “doing” necessarily requiresfaith itself as a precondition. . . . Therefore “doing”is always understood in theology as doing with faith,so that doing with faith is another sphere and a newrealm, so to speak, one that is different from moraldoing. When we theologians speak about “doing”therefore, it is necessary that we speak about doingwith faith, because in theology we have no right reasonand good will except faith. 9Faith in Christ is first expressed in fear and love of God. Thenour love of God becomes channeled into loving service towardothers. Our justification through faith in Christ is thusexpressed in life through loving service to our neighbor.. . . the commandments describe thenatural outworking of faith in theeveryday affairs of daily living in ourfamilies, work and community.Luther recognized that “our neighbor” is determined bywhere we are placed in life. We are limited and dependent creatureswho have been called by the gospel to live within the communitiesin the context of our vocation. This context we couldcall our “circle of nearness,” which particularizes and limits ourcall to serve. Here we encounter real flesh-and-blood peoplewith names and faces. We have not been called to love someabstract humanity, but this does not mean that love is limited tosimply “my station and its duties.” Our circle of nearness alsoincludes the stranger whom we encounter in our path as we tendto our station and its duties. This is what the “certain Samaritan”in the parable understood that apparently the priest and theLevite did not. Jesus implied the same thing when he told us thatinasmuch as we serve the least of his brothers, we serve him.Each of the interpersonal spheres reflected in the secondtable of the commandments becomes a context where God callsus to act out our trust in Christ and love of God. Our tasks ofloving service will vary according to our relationships and commitmentswithin the communities we inhabit. The character ofloving service will be different toward our spouse than towardthe student in the classroom or the check-out person at thelocal supermarket. The commandments do not define love nordo they present an exhaustive list of its duties. Rather they setparameters within which our duties can be found, and beyondwhich our projects and our loves may not go. Given the boundariesof the “shalls” and the “shall nots,” the Scriptures simplyassume that we know what love is and that where it exists in allits joy and spontaneity, it will find its own way. God leaves thematter up to our own creative determination as we encounterthe peculiarities of the people, situations and places in our life.Freedom reigns here, and the possibilities are endless. WhatGod wants us to do is to live out our faith and our loves creatively.Can this involve our own interests, projects and goals?Surely it can. As Luther observed about the Christian’s calling,that which the Scriptures do not forbid is permitted. Here wehave reached the outer limits of a Christian piety. It is tied tothe possibilities of loving service that expresses the obedience offaith. The cross is the Christian’s sentence to a life of freedom.The verdict of God in the cross has set us free to choose andpursue our own activities and goals, so long as they do not conflictwith his call. Our journey of faith through this life involvesthe “gentle art of getting used to our justification.” 10THE PIETY OF THE CHURCHIn our discussion of Christian vocation up to this point,we have focused our attention on God’s call of faith as it islived and expressed by the individual believer within the socialcommunities where God has placed him to live. We haveexplored the life of faith as a life of service and reordered love.Now we want to turn our attention to the corporate dimensionof God’s call that relates to our vocation to be a fellowship offaith—to be a called-out community of God’s people—whatwe more commonly refer to as Christ’s church. We may thinkof our individual vocations within the old creation structuresof life as callings to be the “church scattered.” Here Christianpiety flows from the obedience of subjective faith in projects ofloving service. Individual Christian piety is usually extraordinarilyordinary. We now want to briefly consider the piety ofthe church corporate and for that we must investigate the contoursof vocation for the “church gathered.” This is whatWerner Elert has called “we” piety. 11The church gathered is called to be the family of God thatlives by faith under the grace and the headship of Christ. Thisis what the church is called to be, and it is its primary vocation.Flowing from this primary call is a call to duty. Unlike individualChristian piety, however, the church’s piety is expressed inobjective tasks that need not flow from the subjective faith ofthe individual Christian to be valid. While the piety of the individualChristian is largely subjective in nature and thus hiddenin the ordinary tasks and duties that arise from membership inold world communities, Christian piety considered corporatelyis objective and made up of specific commands of Christ thatare open to the observation and measure of all. This is “we”piety—where Christian piety is ordinarily extraordinary. Hereis where Christians exhibit and display their righteousness andholiness; here it is made manifest to all. In manifesting itsrighteousness and holiness, the church shows off its Head anddistributes his gift of holiness. This is Gottesdienst, the holy

THE OUTER LIMITS OF A LUTHERAN PIETY 9Pietism creeps into the church’s thinking. . . when the works of God aretied to a “higher calling.”Bride of Christ expressing her faith objectively in proclamationof the gospel as Christ taught it to his apostles, and in administrationof his sacraments as he instructed. In addition, thechurch is called to admonish and discipline its impenitentmembers and restore them through his grace when theyrepent. Through the performance of these tasks as means, Jesusand his righteousness are made manifest in the world andbestowed on sinners. Moreover, by these means as marks, thechurch is located and its piety unmistakenly observed. Thechurch gathered has no phantom existence in the world.Indeed, unlike the individual Christian, it is identified throughits piety, the righteousness and holiness of Christ as manifestedin the gospel and sacraments.Through the church’s piety, its Head continues his ministryof building up and extending the Kingdom of God. Tocarry out this vocation of the church, Christ calls pastors today,as he called the apostles before, to carry out the church’s corporatecall in the ministry of word and sacrament. When weconsider the church scattered, we see individual Christianswho receive their vocation from God in their baptism, a call tolive in the grace of Christ by faith as a member of God’s familyprimarily and to express that faith in a life of service in theduties and commitments of the old world communities. Whenwe consider the church gathered, we see her receive her callfrom Christ before he ascended into heaven, and she is calledto express her faith in the public proclamation of the gospeland the administration of the sacraments.Individual members of God’s family relate to the call ofthe church gathered in two ways. First, we are called in theThird Commandment not to despise fellowship in the Wordnor absent ourselves from it. Rather, we are called to partakeregularly of God’s Word as it is proclaimed, and the sacramentsas they are administered. This is of crucial importance,for through the means of grace Christ nurtures our faith andequips and empowers it for daily works of service. Second, thechurch scattered is to witness to Christ and mutually admonishand console one another within our circle of nearness as partof our works of service. When Jesus was with his disciples inthe upper room, he schooled the church scattered about thelife of loving service. It even includes the ordinary dirty businessof life, like washing feet. But when he came to “this is mybody . . . do this in remembrance of me” he called the churchgathered to a part of its vocation.The primary piety of the church scattered is sacrificial innature, and the primary piety of the church gathered is sacramental.The sacrificial life of the church scattered flows fromthe grace-bestowing sacramental life of the church gathered.Corporate piety is always logically prior to individual piety. Asopportunity and need arise, however, we witness to Christ inour individual callings. And as need and opportunity arise, thechurch gathered offers sacrificial service. At Paul’s request, thechurches in Greece took up a collection to aid the faminestrickenchurch in Jerusalem. The church gathered has similarprojects today. The church is hidden within the old worldstructures of society and even in the structures of church government;but it is revealed to faith in terms of its presence byits word and sacrament service. Individual Christian piety isextraordinarily ordinary because its godliness is largely hidden.Corporate church piety, however, is ordinarily extraordinary—and its godliness, which is the righteousness of Christ, is mademanifest in word and sacrament. If you want to see Christianpiety on bold display, Lutherans in the Theology of the Crosssay, “Here it is!” On this count, church historian Mark Nollhad some remarkably favorable things to say about the contributionsAmerican Lutheranism can make to the AmericanChristian scene. He wrote:The Protestant tendency in America has been topreserve the importance of preaching, Bible-reading,the sacraments (or ordinances), and Christian fellowship,but to interpret these as occasions for human actsof appropriation. That God saves in baptism, that Godgives himself in the Supper, that God announces hisWord through the sermon, that God is the best interpreterof his written Word—these Lutheran convictionsare all but lost in the face of American confidence inhuman capacity.Finally what Lutherans can offer Americans is thevoice of Luther, a voice of unusual importance in Christianhistory . . . because in it we hear uncommon resonanceswith the voice of God. ... For whatever reason,in the effable wisdom of God, the speech of MartinLuther rang clear where others merely mumbled. 12THE PERILS OF PIETISMIf we go beyond these outer limits of a piety that lives inthe Theology of the Cross as Luther enunciated it with suchclarity and power, we will inevitably lapse into a false pietyborn from the many theologies of glory that are strewn aboutin church history. Here piety usually lapses into pietism, legalismand pharisaism. Pietism creeps into the church’s thinkingwhen it begins to develop a negative attitude about participationin the worldly interests and concerns of this life; when theworks of God are tied to a “higher calling” in this life thatought to separate us from the affairs of secular life in family,neighborhood and state. When the piety of the Christian ismeasured by a certain outward code of demonstrably holyacts—even if they are drawn from the Bible—we havelaunched into a theology of glory. Historically, pietism wasLutheran orthodoxy stood on its head. Orthodox Christianity(as articulated in confessional Lutheranism) embraces theobjective presentation of Christ and his gifts as they are mediatedby the Spirit-breathed external word and sacraments.Flowing from these gifts of righteousness and holiness, a sub-

10 LOGIAjective personal piety is expressed in faith that is active in worksof loving service. Pietism argued for a subjective mediation ofChrist and the Spirit within the heart of the Christian, whilethe expressions of Christian piety are to be objectively delineatedand divorced from the tasks of worldly concern.“Nave piety” replaces the obedience offaith flowing from the righteousness ofChrist with obedience to the law.Luther depicted a piety of outward works devised by thereligious opinions of men as “churchyard piety.” Monasticismwas the contemporary expression of churchyard piety thatLuther condemned as a false and empty piety that burdenedconsciences and took Christians away from the real tasks in theworld that God would have them be about. This was cloisteredmonasticism. Today we must beware of church body or congregationalchurchyard piety: modern ecclesiastical monasticismthat seeks to inundate its church membership with a veritableplethora of programs, activities and organizational eventsthat lack the context of a true Christian vocation of sacrificialservice in the old world communities of life. “Piety” becomesprogram involvement and participation in everything from“quilting for Christ” to “living prayer chains for endangeredanimals.” In some churches, if one does not schedule life andthe use of gifts according to the week’s “Calendar of ChristianEvents,” something is seen as terribly wrong. One has not beenassimilated into the regimen of real Christian living. Some congregationsare even calling a special pastor in charge of assimilatingmembers into all of these super-spiritual events: the Pastoror Director of Assimilation. The thinly veiled messageseems to be “Blessed are the involved and assimilated, for theyshall inherit the kingdom of God.” Activism in works that donot flow from one’s vocational call is present in every age as atemptation to leave ordinary duties of Christian piety for theextraordinary. This is churchyard piety.Luther had a warning about one more variety of false piety,what he called “nave piety.” Nave piety replaces the obedience offaith flowing from the righteousness of Christ with obedience tothe law. Today some within Lutheran circles are seeking toreplace the obedience of faith with a faith defined by obedience.This, we are told, is the real goal of the gospel. 13 The gospel hasthe central objective to turn us all into obedient people underGod’s legal system. Life with God is said not to terminate evangelicallyon the gospel—it is not the Good News of death to life.Rather, the gospel merely provides the ticket of admission to alegal life of obedience to the precepts of law. Gospel is to law asmeans are to end. The lordship of Christ is not the dominion ofgrace, but the rule of Christ as lawgiver. This is the Reformednotion of the gospel in the service of the law—the idea that Godhas saved us for obedience.Away with these things. We must follow Luther from thechurchyard, from the nave, into the sanctuary where life withGod, the truly godly and pious life, begins and ends with therighteousness of Christ which is the obedience of faith. When itgoes to work in the world it may seem rather ordinary, yes evendead, when not looked upon through the eyes of faith. But herein the old world tasks of everyday life is the outer limits for theexpression of the righteousness of faith. The inner limits however,are found in the sanctuary. When we gather together inthe sanctuary, when we parade our “we” piety through themanifestation of Christ in word and sacrament, there is theextraordinary righteousness of us all—our true piety that hasset us free. And that, Mark Noll and all Christians can recognizeand confess with Luther, is and will always remain extraordinaryand—remarkable! LOGIANOTES1. Mark Noll, “The Lutheran Difference,” First Things(February 1992) p. 31.2. Noll, p. 33.3. AE 26:2354. Werner Elert, The Christian Ethos, trans. by Carl J.Schindler (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1957) p. 73.5. AE 26:235–236.6. A sermon of Luther’s delivered on Feb. 24, 1517, WA1.138.13–15, as cited in Alister E. McGrath, Luther’s Theology ofthe Cross (Cambridge, Mass.: Basil Blackwell, 1990) p. 167.7. AE 31:350.8. Gerhard O. Forde, Justification by Faith: A Matter ofDeath and Life (Ramsey, N.J.: Sigler Press, 1990) pp. 57–58.9. AE 26:262–263.10. This is Gerhard Forde’s striking depiction of the sanctificationof the Christian in his presentation of “The LutheranView” of sanctification in Christian Spirituality: Five Views ofSanctification, edited by Donald L. Alexander (Downers Grove,Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1988) pp. 13–32.11. Elert, pp. 336–345.12. Noll, p. 39.13. This is the central thesis of Bickel/Nordlie’s The Goal ofthe Gospel: God’s Purpose in Saving You (St. Louis: ConcordiaPublishing House, 1992) p. 271 ff.

Conditional Forgivenessand the Translation of 1 John 1:9JOHN M. MOEJOHN FENTON IN HIS EXCELLENT ARTICLE, “IF WE CONFESSOur Sins: Conditional Forgiveness and 1 John 1:9,” 1 hassounded a much-needed corrective to the common misunderstandingof 1 John 1:9. “But if we confess our sins, God,who is faithful and just, will forgive our sins and cleanse usfrom all unrighteousness” is the translation used in the publicworship of many Lutheran Churches. 2 He is, I believe,absolutely correct when he says “To most people, these wordsmean: . . . (B) confessing our sins results in God forgiving usour sins just as he promised and because he is fair.” 3 He is alsocorrect in pointing out that this is not a classical “if X then Y”conditional sentence in which condition Y exists as the resultof condition X. I believe, however, that the Rev. Fenton hasmissed a very strong argument in favor of the point he is makingwhen he says that the fault for this misunderstanding is“not because of a faulty translation.” 4The Greek has eja;n oJmologw'men ta;" aJmartiva" hJmw'n,pistov" ejstin kai; divkaio" i{na ajfh/' hJmi'n ta;" aJmartiva" kai;kaqarivsh/ hJma'" ajpo; pavsh" ajdikiva". “If we confess our sins,faithful he is and righteous to forgive to us the sins and tocleanse us from all unrighteousness.” There are a number ofways in which the rendering of this verse by the Lutheran Bookof Worship (LBW) and Lutheran Worship (LW) is unfaithful tothe Greek text, all of which contribute to the false notion thatthe forgiveness and cleansing of which John writes is the resultof our confession.Both hymnals have “If we say we have no sin, we deceiveourselves, and the truth is not in us. But if we confess our sins,God, who is faithful and just, will forgive our sins and cleanseus from all unrighteousness.” 5The conjunction “but” has been added (“But if we confess,”etc.) where the Greek has no conjunction at all. Thisforces a logical connection between verse eight and verse ninethat is not there in the Greek. If saying that we have no sin isunderstood to result in deceiving ourselves in verse eight, theadded “but” to begin verse nine insures that the forgivenessand cleansing will be seen as the result of our confession.ABOUT THE AUTHORJOHN MOE is pastor of St. John’s Lutheran Church, Rosemount,Minnesota.11But the major fault with the translation of verse nine liesnot with the added “but” but with the distortion of theGreek grammar in the hymnals’ version. If we assume this tobe a conditional sentence, we must divide it into the protasis,eja;n oJmologw'men ta;" aJmartiva" hJmw'n, and the apodosis,pistov" ejstin kai; divkaio" i{na ajfh/' hJmi'n ta;" aJmartiva" kai;kaqJarivsh/ hJma'" ajpo; pavsh” ajdikiva". The apodosis, it will benoted, is an independent clause. 6 It can stand as a sentenceby itself with subject (“He,” understood), finite verb (“is”),and a i{na clause (“to forgive our sins and cleanse us from allunrighteousness”). The force of the i{na clause is disputed,but the dispute is whether the i{na clause should be seen as apurpose or as a result clause. 7 That dispute is not pertinentto our discussion here however, for either way, our forgivenessand cleansing are the purpose or the result of God’sfaithfulness and righteousness and not the purpose or resultof our confession.The translation we are dealing with renders the infinitives,which are the purpose or the result of God’s faithfulnessand righteousness, with future indicatives “will forgive. . .” and “cleanse,” and the all-important attributes ofGod in a parenthetical phrase, “who is faithful and just.” Theresult allows, and even invites, an erroneous, conditionalunderstanding of what John has to say about forgivenesshere.Every grade-school grammar student knows that a parentheticalphrase can be overlooked without distorting themeaning of the sentence in which it lies. It merely addsinformation—pertinent, helpful information perhaps—butnot information which is essential to the meaning of the sentence.“But if we confess our sins, God, who is faithful andjust, will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness”makes logical sense without the parentheticalphrase: “But if we confess our sins, God will forgive our sinsand cleanse us from all unrighteousness.” This is the classicformulation of the conditional sentence and clearly soundslike the forgiveness and cleansing are the result of our confession.But we have seen from the Greek that what John saysis that our forgiveness and cleansing are the result or thepurpose of God’s faithfulness and righteousness, not theresult of our confession. The translation clearly supports adistorted notion that is not in the Greek.

12 LOGIAThe translation, “But if we confess our sins, God, who isfaithful and just, will forgive our sins and cleanse us from allunrighteousness,” has a logical opposite which is “But if wedon’t confess our sins, God, who is faithful and just, will notforgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.”That logical deduction, invited and supported by the translation,is a dangerous error which the Greek shows to beimpossible and bordering on the blasphemous. A faithfulrendering of the Greek grammar, given the same logicaltreatment, would be: “If we don’t confess our sins, he isn’tfaithful and righteous to forgive to us the sins and to cleanseus from all unrighteousness.” Clearly this is not a conditionalsentence in which the condition described in the apodosisdepends on the “if” of the protasis.Rev. Fenton is, I think, correct in his belief (if I understandhim correctly) that we English-speaking Americansseem to expect a conditional sentence of the “if X then Y”variety whenever we are confronted with the word “if.”There are examples in English, however, of the type of sentencehe refers to as “what Dr. James Voelz calls a ‘presentgeneral condition.’” 8 That is to say there are others besides1 John 1:9. Two quick examples might be Luke 5:12, Kuvrie,eja;n qevlh/" duvnasaiv mh kaqarivvsai (“Lord, if you wish, youare able to cleanse me”) and Luke 22:67, Eja;n uJmi'n ei[pw oujmh; pisteuvshte. (“If I tell you, you will not believe”).Also, eja;n is not always best rendered “if.” A bit further onin this same letter John writes eja;n fanerwqh/' o{moioi aujtw/'ejsovmeqa (1 Jn 3:2). I know of no translation which renders this“If he appears we will be like him.” “When” seems to be thecorrect choice in this instance. I would suggest that “when”might be a better choice for the rendering of eja;n in 1 John 1:9 aswell. And although it may not read as smoothly in English, Iwould also suggest that the infinitive verb forms of the Greekbe retained in the apodosis to avoid distorting John’s meaning(that our forgiveness and cleansing are the purpose or result ofGod’s faithfulness and righteousness, not the result of our confession).I would attempt to render John’s Greek into Englishwith something like the following:eja;n oJmologw'men ta;" aJmartiva" hJmw'n, pistov" ejstinkai; divkaio" i{na ajfh/' hJmi'n ta;" aJmartiva" kai;kaqarivsh/ hJma'" ajpo; pavsh" ajdikiva". When we confessour sins, faithful he is and righteous to forgive oursins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. LOGIA1. Rev. John Fenton, “If We Confess Our Sins: ConditionalForgiveness and 1 John 1:9,” LOGIA Vol.2, No. 1 (Epiphany/January1993) p. 49.2. Lutheran Worship, pp. 158, 178; Lutheran Book of Worship,pp. 56, 77, 98.3. Fenton.4. Fenton.5. This translation matches no English Bible translation I havebeen able to find. Of the many which I have checked, it is closest tothe RSV which has, “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just,and will forgive our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness.”“But” has been added in the hymnal and “he is faithful and just, andwill . . .” has been changed to “God, who is faithful and just,will. . . .” Could it be that a desire to clarify the “he” of the RSV forliturgical usage has led to the hymnals’ regrettable weakening of thetranslation? The main point of John’s sentence, expressed with thefinite verb (i.e. “he is faithful and righteous”), has become not muchmore than an aside (“God, who [by the way] is faithful and just”).6. A search of every New Testament occurrence of eja;n revealsthree other sentences with a verbal clause controlled by eja;n and ai{na clause in the apodosis: Mt 18:16 eja;n de; mh; ajkouvsh/, paravlabemeta; sou' e[ti e{na h] duvo, i[na ejpi; stovmato" duvo martuvrwn h] triw'nstaqh/' pa'n rJh'ma, Jn 14:3 kai; eja;n poreuqJw' kai; ejtoimavswNOTEStovpon uJmi'n, pavlin e[rcomai kai; paralhvmyomai uJma'" pro;"ejmautovn, i{na o{pou eijmi; ejgw; kai; uJmei'" h\te, and 2 Cor 9:4 mhvpw” eja;n e[lqJwsin su;n ejmoi; Makedovne" kai; eu{rwsin uJma’"ajparaskeuavstou" kataiscunqJw'men hJmei'", i{na mh; levgwuJmei'", ejn th/' uJpostavsei tauvth/. Note that in the Matthew andJohn passages, which parallel the grammar of 1 John 1:9, theapodosis is an independent clause, and the i{na clause is dependenton the action of the verb preceding it and not on the verbcontrolled by eja;n (i.e., at Mt 18:16 the word is establishedbecause of taking one or two with you, not because the brotherdid not hear, etc.).7. The dispute is not over this verse only, but the moregeneral question of whether i{na is ever used to express result orif it must always be understood as expressing purpose. Robertsondisagrees with Burton saying, “He considers Rev. 13:13,poiei' shmei'a megavla, i{na kai; pu'r poih/' ejk tou' oujranou'katabaivnein, as the most probable instance of i{na denotingactual result. But there are others just as plain, if not clearer.Thus 1 John 1:9 pistov" ejstin kai; divkaio", i{na ajfh/' hJmi'n ta;"aJmartiva"” (A.T. Robertson, A Grammar of the Greek New Testamentin the Light of Historical Research (Nashville: BroadmanPress, 1934) p. 998).8. Fenton.

Preaching to Preachers: Isaiah 6:1‒8DONALD MOLDSTADIn the year that king Uzziah died I saw also the Lordsitting upon a throne, high and lifted up, and his trainfilled the temple. Above it stood the seraphims: eachone had six wings; with twain he covered his face, andwith twain he covered his feet, and with twain he didfly. And one cried unto another, and said, “Holy, holy,holy, is the Lord of hosts: the whole earth is full of hisglory.” And the posts of the door moved at the voice ofhim that cried, and the house was filled with smoke.Then said I, “Woe is me! for I am undone; because Iam a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of apeople of unclean lips: for mine eyes have seen theKing, the Lord of hosts.” Then flew one of the seraphimunto me, having a live coal in his hand, which he hadtaken with the tongs from off the altar: And he laid itupon my mouth, and said, “Lo, this hath touched thylips; and thine iniquity is taken away, and thy sinpurged.” Also I heard the voice of the Lord, saying,“Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” Thensaid I, “Here am I; send me.”AS A STUDENT OF THE HISTORY OF ART I HAVE VIEWEDthousands of slides, paintings, drawings and sculpture.Yet I cannot recall seeing a painting of the commissioningof Isaiah (Is 6:1–8). That may be due in part to the challengeof portraying the glory of God. It is very difficult to portraythis glory adequately. Even the more familiar paintings ofthe transfiguration of Christ are feeble attempts to display thissplendor.Man is unable to face the glory of the almighty Lord.Moses hid his face from the burning bush. At the transfigurationwe are told that the disciples fell face down, terrified. Herein our text, Isaiah is struck with intense guilt before God. Hisreaction is nothing but sheer despair. The first words from hismouth demonstrate this: “Woe to me I am ruined!” His wordsremind us of Peter upon experiencing the great catch of fishesABOUT THE AUTHORDONALD MOLDSTAD is pastor of King of Grace Lutheran Church,Golden Valley, Minnesota. This confessional address was preached toa circuit pastoral conference of the Evangelical Lutheran Synod.13orchestrated by Christ. When sensing the great disparitybetween himself and the glorious Son of God, he falls to thefeet of his Lord, and cries, “Get away from me Lord, for I am asinful man.” The brightness of God’s glory, the display of hisholiness, exposes all the more man’s wickedness and mortality.Isaiah writes that the angels sing, “Holy, holy, holy”—theHebrew word v/dq; is used, which means “set apart,” emphasizingthe distinction between the holy God and sinful mortalman. The comparison is unbearable for the prophet.We make comparisons all the time in our world. When wecompare ourselves to others, we can begin to imagine ourselvesbetter than we ought. That is especially true for those of us inthe teaching and preaching ministry. We receive the gratitudeof other believers, and at times their praises too, since we arededicated to the work of the Lord full time. But Satan can useeven this blessing of being entrusted with the mysteries of Godand turn it into a temptation of self-inflation.Furthermore, there is a need, due to our calling, for anincreased outward righteousness in our daily lives. It is expected,demanded of us. It is part of what we are before the world.Because of all this there is no more fertile garden for the seedsof pride and self-righteousness than in the office of the publicministry today. It is significant that in the parable of the publicanand the Pharisee in the Temple, Christ used the role of thePharisee—the moral, spiritual leader of his day—to representself-righteousness. In teaching it today he might choose to usea confessional Lutheran pastor. And if that thought troublesus, it shows the truth of it all the more.We condemn the liberal and Reformed who question theclear teachings of the Word of God, looking at them in derision,thinking, “God, I thank thee, I’m not as other men are.”Yet, in our own thoughts and in the inner chambers of ourhearts, we are just as full of doubt. The greatest temptation forthose called to the gospel ministry is pride.And on the other side is another danger: those who are theclosest to operating the knives of God’s law are most apt to getcut. We deal with that law all the time in preaching, teachingand counseling. It carves and cuts. So when the called ministerof God falls into sin, or looks back on past failings, it can drivethe preacher to despair. We are reminded all the more of thegreat difference between what our members or students imagineus to be and what we see in our own hearts.