05-4 Theology of the..

05-4 Theology of the..

05-4 Theology of the..

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Logia<br />

a journal <strong>of</strong> lu<strong>the</strong>ran <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

THEOLOGY OF THE CROSS & JUSTIFICATION<br />

reformation 1996 volume v, number 4

ei[ ti" lalei',<br />

wJ" lovgia Qeou'<br />

logia is a journal <strong>of</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>ran <strong>the</strong>ology. As such it publishes<br />

articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

that promote <strong>the</strong> orthodox <strong>the</strong>ology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Evangelical<br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> church: <strong>the</strong> gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and <strong>the</strong><br />

sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This<br />

name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA<br />

functions ei<strong>the</strong>r as an adjective meaning “eloquent,” “learned,”<br />

or “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,”<br />

“words,” or “messages.” The word is found in 1 Peter 4:11, Acts<br />

7:38, and Romans 3:2. Its compound forms include oJmologiva<br />

(confession), ajpologiva (defense), and ajvnalogiva (right relationship).<br />

Each <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se concepts and all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>m toge<strong>the</strong>r express <strong>the</strong><br />

purpose and method <strong>of</strong> this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free<br />

conference in print and is committed to providing an independent<br />

<strong>the</strong>ological forum normed by <strong>the</strong> prophetic and apostolic<br />

Scriptures and <strong>the</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Confessions. At <strong>the</strong> heart <strong>of</strong> our<br />

journal we want our readers to find a love for <strong>the</strong> sacred Scriptures<br />

as <strong>the</strong> very Word <strong>of</strong> God, not merely as rule and norm, but<br />

especially as Spirit, truth, and life which reveals Him who is <strong>the</strong><br />

Way, <strong>the</strong> Truth, and <strong>the</strong> Life—Jesus Christ our Lord. Therefore,<br />

we confess <strong>the</strong> church, without apology and without rancor, only<br />

with a sincere and fervent love for <strong>the</strong> precious Bride <strong>of</strong> Christ,<br />

<strong>the</strong> holy Christian church, “<strong>the</strong> mo<strong>the</strong>r that begets and bears<br />

every Christian through <strong>the</strong> Word <strong>of</strong> God,” as Martin Lu<strong>the</strong>r says<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Large Catechism (LC II, 42). We are animated by <strong>the</strong> conviction<br />

that <strong>the</strong> Evangelical Church <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Augsburg Confession<br />

represents <strong>the</strong> true expression <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church which we confess as<br />

one, holy, catholic, and apostolic.<br />

LOGIA (ISSN #1064‒0398) is published quarterly by <strong>the</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>r Academy, 9228 Lavant<br />

Drive, Crestwood, MO 63126. Non-pr<strong>of</strong>it postage paid (permit #4)) at Cresbard, SD and<br />

additional mailing <strong>of</strong>fices.<br />

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to LOGIA, PO Box 94, Cresbard, SD 57435.<br />

Editorial Department: 1004 Plum St., Mankato, MN 56001. Unsolicited material is<br />

welcomed but cannot be returned unless accompanied by sufficient return postage.<br />

Book Review Department: 1101 University Avenue SE, Minneapolis, MN 55414. All<br />

books received will be listed.<br />

Logia Forum and Correspondence Department: 2313 S. Hanna, Fort Wayne, IN 47591-<br />

–3111. Letters selected for publication are subject to editorial modification, must be typed<br />

or computer printed, and must contain <strong>the</strong> writer’s name and complete address.<br />

Subscription & Advertising Department: PO Box 94, Cresbard, SD 57435. Advertising<br />

rates and specifications are available upon request.<br />

SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION: U.S.: $20 for one year (four issues). Canada and<br />

Mexico: 1 year surface, $23; 1 year air, $30. Overseas: 1 year, air: $50; surface: $27. All<br />

funds in U.S. currency only.<br />

Copyright © 1996. The Lu<strong>the</strong>r Academy. All rights reserved. No part <strong>of</strong> this publication<br />

may be reproduced without written permission.<br />

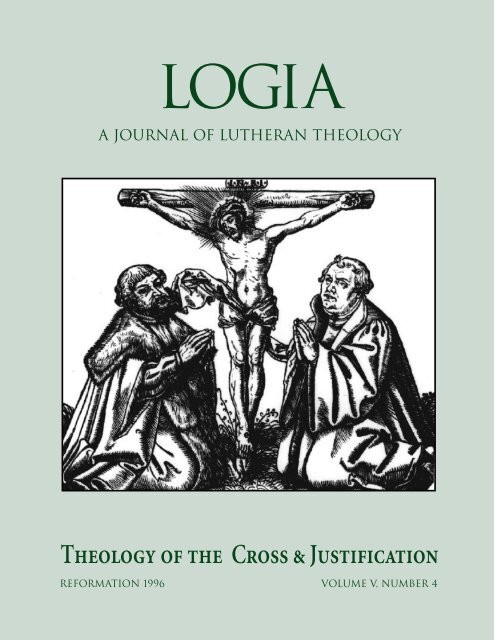

THE COVER ART features a woodblock engraving <strong>of</strong> Frederick<br />

<strong>the</strong> Wise and Martin Lu<strong>the</strong>r adoring <strong>the</strong> crucified<br />

Christ. The identity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> artist is not established. His initials<br />

are M. S., and he was active in Wittenberg from 1530<br />

to 1572. His illustrations appear in many <strong>of</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s writings<br />

issuing from <strong>the</strong> press <strong>of</strong> Hans Lufft.<br />

This engraving adorns <strong>the</strong> title pages <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wittenberg<br />

edition <strong>of</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s works. Published in twenty volumes<br />

(twelve German, seven Latin, and one index) between 1539<br />

and 1559, this first published collection <strong>of</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s writings<br />

was reprinted repeatedly until 1603. The publisher was<br />

Hans Lufft in Wittenberg, and <strong>the</strong> sponsor was John Frederick<br />

<strong>of</strong> Saxony, <strong>the</strong> bro<strong>the</strong>r and successor <strong>of</strong> Frederick.<br />

Reproduced from Volume 4 <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Wittenberg edition contained<br />

within <strong>the</strong> Haffenreffer Library <strong>of</strong> Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Dogmatician’s<br />

Collection <strong>of</strong> Concordia Seminary, St. Louis,<br />

Missouri. Used by permission.<br />

FREQUENTLY USED ABBREVIATIONS<br />

AC [CA] Augsburg Confession<br />

AE Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s Works, American Edition<br />

Ap Apology <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Augsburg Confession<br />

BSLK Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lu<strong>the</strong>rischen Kirche<br />

Ep Epitome <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Formula <strong>of</strong> Concord<br />

FC Formula <strong>of</strong> Concord<br />

LC Large Catechism<br />

LW Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Worship<br />

SA Smalcald Articles<br />

SBH Service Book and Hymnal<br />

SC Small Catechism<br />

SD Solid Declaration <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Formula <strong>of</strong> Concord<br />

Tappert The Book <strong>of</strong> Concord: The Confessions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Evangelical<br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Church. Trans. and ed. Theodore G. Tappert<br />

TDNT Theological Dictionary <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> New Testament<br />

TLH The Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Hymnal<br />

Tr Treatise on <strong>the</strong> Power and Primacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Pope<br />

Triglotta Concordia Triglotta<br />

WA Lu<strong>the</strong>rs Werke, Weimarer Ausgabe [Weimar Edition]

logia<br />

a journal <strong>of</strong> lu<strong>the</strong>ran <strong>the</strong>ology<br />

reformation 1996 volume v, number 4<br />

CONTENTS<br />

A Note to Our Readers .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2<br />

ARTICLES<br />

The Two-Faced God<br />

By Steven A. Hein .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3<br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s Augustinian Understanding <strong>of</strong> Justification in <strong>the</strong> Lectures on Romans<br />

By David Maxwell .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 9<br />

The Doctrine <strong>of</strong> Justification and Its Implications for Evangelicalism<br />

By Scott R. Murray..................................................................................................................................................................................................15<br />

A Call for Manuscripts .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 22<br />

Divine Service: Delivering Forgiveness <strong>of</strong> Sins<br />

By John T. Pless ......................................................................................................................................................................................................23<br />

Reflections on Lu<strong>the</strong>ran Worship, Classics, and <strong>the</strong> Te Deum<br />

By Carl P. E. Springer ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 29<br />

Patrick Hamilton (1503–1528): A Scottish Reformer with a Timeless Confession<br />

By Bruce W. Adams .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 43<br />

REVIEWS .................................................................................................................................................................................................... 45<br />

REVIEW ESSAY: What Is Liturgical <strong>Theology</strong> A Study in Methodology. By David W. Fagerberg.<br />

Worship in Transition: The Liturgical Movement in <strong>the</strong> Twentieth Century. By John Fenwick and Bryan Spinks.<br />

Remembering <strong>the</strong> Christian Past. By Robert L. Wilken.<br />

Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt, and Certainty in Christian Discipleship. By Leslie Newbigin.<br />

Transforming Congregations for <strong>the</strong> Future. By Loren B. Mead.<br />

Notes from a Wayfarer: The Autobiography <strong>of</strong> Helmut Thielicke. Translated by David R. Law.<br />

BRIEFLY NOTED<br />

PrEVIEW: Actio Sacramentalis—Die Verwaltung des Heiligen Abendmahles nach den Prinzipien Martin Lu<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

in der Zeit bis zur Konkordienformel. Luth. Verlagsbuchhandlung Groß Oesingen, 1996.<br />

LOGIA FORUM ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 57<br />

The Idolatrous Religion <strong>of</strong> Conscience • The Infusion <strong>of</strong> Love • The Cross and <strong>the</strong> Christian Life<br />

The Ship <strong>of</strong> Fools • Chapters Into Verse • Me Gavte La Nata<br />

Utilitarian Schools, Utilitarian Churches • The Last Word on Church and Ministry<br />

Objective Justification—Again • Praesidium Statement on Closed Communion<br />

Is Martens Justified • From Arrowhead to Augsburg • Worship at Lu<strong>the</strong>r Campus • Crazy Talk, Stupid Talk<br />

Upper Story Landing • Didache Today • Clergy Killers<br />

INDICES FOR VOLUMES I THROUGH V ................................................................................................................ 71<br />

Articles by Title • Articles by Author<br />

Book Reviews by Title • Book Reviews by Author<br />

LOGIA Forum

4 LOGIA<br />

<br />

ANote to Our Readers<br />

The editors wish to apologize to all <strong>of</strong> our faithful readers for <strong>the</strong> persistent lateness <strong>of</strong> LOGIA.<br />

We have taken as many steps as we can to solve <strong>the</strong> problem, but each time we fix one problem<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r arises in its place.<br />

All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> editors are volunteers. Except for <strong>the</strong> production staff, none <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> editors receives<br />

any remuneration for his work, and <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong> stipends paid to <strong>the</strong> production staff barely can<br />

be called token.<br />

The working editors are all parish pastors or college pr<strong>of</strong>essors, and thus have many demands<br />

on <strong>the</strong>ir time. The parish pastors especially are subject to emergencies and to <strong>the</strong> increased<br />

demands <strong>of</strong> various seasons <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> church year. The callings <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> editors all must take<br />

precedence over <strong>the</strong>ir volunteer work with LOGIA.<br />

We are very grateful to our readers for <strong>the</strong>ir continued patience. It is our hope that as LOGIA<br />

continues to grow, it will be possible for us to increase our production staff and pay <strong>the</strong>m<br />

sufficiently so that <strong>the</strong> production <strong>of</strong> LOGIA will be more timely. Until <strong>the</strong>n, we thank our<br />

readers for <strong>the</strong>ir continued indulgence.<br />

Erling T. Teigen<br />

Coordinating editor

NOT ONLY REFLECTIVE, LEARNED SCHOLARS have pondered<br />

<strong>the</strong> question, “What is God really like” or even more<br />

momentous questions such as: “What does he think<br />

about us and <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> evil here on earth Does he care Can<br />

we bargain with him or enlist his help in how we want to deal with<br />

it Is he a mighty, vengeful, ‘hard-nosed’ kind <strong>of</strong> God who is really<br />

not satisfied with anything less than perfection; or is he, ra<strong>the</strong>r, a<br />

kind, merciful sort <strong>of</strong> Deity” From mature intellectuals to young,<br />

inquisitive children, persons in every age have mulled over and<br />

debated questions such as <strong>the</strong>se. At some point in our lives, perhaps<br />

we too have desired to take <strong>the</strong> measure <strong>of</strong> God and wondered,<br />

“What would it be like to meet God face to face”<br />

MEETING THE GOD WHO SAVES<br />

The Hidden and Revealed God<br />

Although God is always closer to us than <strong>the</strong> nose on our face,<br />

he has not taken <strong>the</strong> wraps <strong>of</strong>f and given any sinful and mortal<br />

human being a full measure, face-to-face meeting. As God told<br />

Moses, who requested such a meeting, <strong>the</strong> face or full splendor <strong>of</strong><br />

his holiness and glory would be <strong>the</strong> immediate death <strong>of</strong> any sinful<br />

human (Ex 33:20). Out <strong>of</strong> his mercy, our God keeps himself on <strong>the</strong><br />

whole “under wraps,” a hidden God, but not totally hidden. He has<br />

chosen to reveal himself at some times and certain places, and <strong>the</strong>n<br />

only to reveal aspects <strong>of</strong> himself. In early Old Testament history,<br />

God <strong>of</strong>ten revealed himself as <strong>the</strong> One who is really in control <strong>of</strong><br />

things here on earth. Again and again he manifested his might and<br />

power in awesome ways. In <strong>the</strong> days <strong>of</strong> Noah, it was through <strong>the</strong><br />

destructive flood. With Sodom and Gomorra, it was fire and brimstone.<br />

In Egypt it was <strong>the</strong> plagues, <strong>the</strong> death <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> first-born, and<br />

<strong>the</strong> parting <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Red Sea. To those on Mt. Carmel it was fireballs<br />

from heaven that reduced a water-drenched sacrifice and altar to<br />

powdered ash. As much as we modern-day believers sometimes<br />

think that a good exhibition by God today would do wonders for<br />

<strong>the</strong> cause <strong>of</strong> true religion, <strong>the</strong>se spectacular works by God never did<br />

inspire much in <strong>the</strong> way <strong>of</strong> long-term faith and devotion. For <strong>the</strong><br />

most part, most <strong>of</strong> God’s mighty displays in <strong>the</strong> Old Testament<br />

simply scared <strong>the</strong> daylights out <strong>of</strong> people. Even in <strong>the</strong> wilderness<br />

when God first took up a glorious presence with his people in a<br />

special tent, <strong>the</strong> children <strong>of</strong> Israel always stood outside as if saying<br />

to Moses, “You go in and see what he wants; we’ll stay out here. You<br />

can tell us all about it later.” It almost seems as if God’s special way<br />

<strong>of</strong> saying hello in <strong>the</strong> Old Testament was to continually speak <strong>the</strong><br />

STEVEN HEIN teaches at Concordia University, River Forest, Illinois, and<br />

is a LOGIA contributing editor.<br />

The Two-Faced God<br />

Steven A. Hein<br />

<br />

5<br />

words, “Do not be afraid.” Meetings with <strong>the</strong> sovereign God back<br />

<strong>the</strong>n were usually a ra<strong>the</strong>r frightening experience.<br />

Mindful <strong>of</strong> our sinful frailty, yet possessing an all-embracing<br />

desire to bring us into a personal relationship with himself<br />

accented by faith and love, God has chosen to reveal himself to us<br />

hidden in <strong>the</strong> common things <strong>of</strong> this world. Our Creator has chosen<br />

to make himself personally known through <strong>the</strong> Word-madeflesh,<br />

Jesus; in <strong>the</strong> prophetic and <strong>the</strong> apostolic Scriptures; and in<br />

<strong>the</strong> word-made-visible in baptism and <strong>the</strong> Lord’s Supper. With<br />

<strong>the</strong> masks <strong>of</strong> humanity, earthly language, and <strong>the</strong> simple elements<br />

<strong>of</strong> water, bread, and wine, God has not simply descended to us,<br />

but condescended to us. Here he continually gives us <strong>the</strong> opportunity<br />

to take him in with all our senses in long, slow, and unalarming<br />

ways, face to face! God has no desire to destroy us. He wants<br />

to love and tenderly embrace us as his own. Moreover, his burning<br />

desire from creation on has been that we might respond to his<br />

love with a returning love, molding a magnificent relationship<br />

and life toge<strong>the</strong>r. But as we know, love always complicates things<br />

for us. It complicates things for God too. Søren Kierkegaard illustrated<br />

God’s problem well in <strong>the</strong> following parable:<br />

Suppose <strong>the</strong>re was a king who loved a humble maiden. The<br />

king was like no o<strong>the</strong>r king. Every statesman trembled<br />

before his power. No one dared brea<strong>the</strong> a word against him,<br />

for he had <strong>the</strong> strength to crush all opponents. And yet this<br />

mighty king was melted by love for a humble maiden.<br />

How could he declare his love for her In an odd sort <strong>of</strong><br />

way, his very kingliness tied his hands. If he brought her to<br />

<strong>the</strong> palace and crowned her head with jewels and clo<strong>the</strong>d<br />

her body in royal robes, she would surely not resist—no<br />

one dared resist him. But would she love him<br />

She would say she loved him, <strong>of</strong> course, but would she<br />

truly Or would she live with him in fear, nursing private<br />

grief for <strong>the</strong> life she left behind Would she be happy at his<br />

side How could he know If he rode to her forest cottage in<br />

his royal carriage, with an armed escort waving bright banners,<br />

that too would overwhelm her. He did not want a<br />

cringing subject. He wanted a lover, an equal. He wanted<br />

her to forget that he was a king and she a humble maiden<br />

and to let shared love cross over <strong>the</strong> gulf between <strong>the</strong>m.<br />

The king convinced he could not elevate <strong>the</strong> maiden without<br />

crushing her freedom, resolved to descend. He clo<strong>the</strong>d<br />

himself as a beggar and approached her cottage incognito,<br />

with a worn cloak fluttering loosely about him. It was no<br />

mere disguise, but a new identity he took on. He renounced<br />

<strong>the</strong> throne to win her hand. *

6 LOGIA<br />

As we know, <strong>the</strong> truth in Kierkegaard’s parable entered human<br />

history in Jesus Christ. Paul eloquently summarized <strong>the</strong> historical<br />

version <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> story in Philippians 2:<br />

Who being in very nature God, did not consider equality<br />

with God something to be grasped, but made himself nothing,<br />

taking <strong>the</strong> very nature <strong>of</strong> a servant, being made in<br />

human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man,<br />

he humbled himself and became obedient to death—even<br />

death on a cross!<br />

The king cast <strong>of</strong>f his regal robes and became a helpless baby, a<br />

lowly footwasher, and a shameful crossbearer. Not very scary, but<br />

that is precisely <strong>the</strong> point. God has love and courtship on his<br />

mind. In Jesus, God meets us face to face., but incognito and<br />

humbly, to win us over with a dying, sacrificial love to be his own<br />

bride forever. As he conquered <strong>the</strong> forces <strong>of</strong> darkness and death,<br />

<strong>the</strong> risen and exalted Christ is still with us, and out <strong>of</strong> his loving<br />

designs, humbly hidden in his gospel, cloaked in mundane human<br />

language and <strong>the</strong> common elements <strong>of</strong> water, bread, and wine.<br />

Through <strong>the</strong>se, word and sacrament, his gospel ministry <strong>of</strong> salvific<br />

courtship with frail, sinful people continues. Only now he carries<br />

it out through common human bodies like yours and mine. We in<br />

his church have become part <strong>of</strong> our Lord’s humble disguise!<br />

The king cast <strong>of</strong>f his regal robes and<br />

became a helpless baby, a lowly footwasher,<br />

and a shameful crossbearer.<br />

nb<br />

It’s not very flashy or spectacular, nothing like <strong>the</strong> great Old<br />

Testament extravaganzas. Hollywood would never clamor for <strong>the</strong><br />

screen rights, but here is God’s loving face as clearly as we can<br />

receive it from him. And it is his ministry and <strong>the</strong> way he condescends<br />

to meet us for our sake out <strong>of</strong> his mercy and love. Make no<br />

mistake about it, God was not fooling around when he made his<br />

Son incarnate. The cross cost him <strong>the</strong> humiliation and death <strong>of</strong><br />

his own Son, and all for <strong>the</strong> sake <strong>of</strong> his burning love for us sinful<br />

human beings. In <strong>the</strong> gospel, we truly meet an honest-to-God:<br />

God as he truly is, a loving and merciful heavenly Fa<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

God’s Preparatory Meeting<br />

Honest encounters among persons human or divine, however,<br />

always require that everything significant is out in <strong>the</strong> open. Fireballs<br />

and smoke will not reveal a loving and gracious God on <strong>the</strong><br />

divine side <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> meeting, and deceitfulness and dishonesty will<br />

not do on our side. All who think <strong>the</strong>y have <strong>the</strong> spiritual mettle to<br />

request a face-to-face meeting with God must realize, as C. S. Lewis<br />

did, that such a meeting requires that we rebellious sinners bring<br />

only our true face to <strong>the</strong> encounter. And <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> rub that brings<br />

<strong>the</strong> curiosity about divine matters within both child and learned<br />

scholar to a screeching halt. We don’t have <strong>the</strong> spiritual mettle<br />

natively within us for that. True moral self-honesty is a spiritual<br />

virtue, but we sons and daughters <strong>of</strong> Adam are spiritually dead.<br />

God, <strong>the</strong>refore, has ano<strong>the</strong>r face and ministry for us and our<br />

salvation to prepare us for <strong>the</strong> real-face-to-face meeting with him<br />

through <strong>the</strong> gospel. Through this preparatory meeting he gives us<br />

a true and honest face and <strong>the</strong> humility to meet him in his love<br />

and mercy. You cannot meet God as he truly is until you have met<br />

up with yourself as you really are. God will not be mocked by<br />

sham meetings with faceless human beings. We must wear our<br />

true face, and that is just what God would provide by meeting<br />

him through his law.<br />

Here we see one <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most unique and distinctive features<br />

about Christianity that separates it from all <strong>the</strong> religions <strong>of</strong> man.<br />

Most religions have a moral code that is commended to us with<br />

<strong>the</strong> promise that through it we can all become better people. With<br />

legal enlightenment and commitment to a virtuous sense <strong>of</strong> duty,<br />

we can all make significant progress in overcoming our perceived<br />

moral defects. Do-ability with sufficient resolve is <strong>the</strong> hallmark <strong>of</strong><br />

man’s moral precepts. “I ought, <strong>the</strong>refore I can,” said <strong>the</strong> famous<br />

moral philosopher Immanuel Kant. He constructed a whole system<br />

<strong>of</strong> ethics based on that assumption.<br />

But when we stand in <strong>the</strong> mirroring light <strong>of</strong> God’s law <strong>of</strong> life, it<br />

casts a shadow <strong>of</strong> darkness and death about us that elicits <strong>the</strong><br />

opposite confession: “I ought, but I don’t and I can’t.” God’s law<br />

shows us that our problem is not at its root immorality or weak<br />

resolve: ours is a problem <strong>of</strong> spiritual bankruptcy and death. This<br />

is <strong>the</strong> dark truth that lies tucked away deep in <strong>the</strong> soul <strong>of</strong> every<br />

sinner, that must be faced with all repentant honesty before we<br />

can meet <strong>the</strong> gracious God face to face. Our idolatry and deceitfulness<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> heart must be confronted for what <strong>the</strong>y are. The<br />

gap between what we are and what we ought to be needs to be<br />

seen as <strong>the</strong> great abyss that we are unable to cross.<br />

Jesus expressed <strong>the</strong> pith and marrow <strong>of</strong> God’s law when he<br />

repeated <strong>the</strong> Deuteronomic formula “You shall love <strong>the</strong> Lord your<br />

God with all your heart, mind, and soul and your neighbor as<br />

yourself.” And setting himself up as <strong>the</strong> revealed enfleshment <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

law, he commanded his disciples to “love one ano<strong>the</strong>r even as I<br />

have loved you.” Love is <strong>the</strong> law <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spirit <strong>of</strong> life, for God is love<br />

and God is life. There are two elements in full-strength law. The<br />

first is love, <strong>the</strong> character <strong>of</strong> God and <strong>the</strong> core purpose <strong>of</strong> human<br />

existence that God designed for us from <strong>the</strong> beginning. Love is <strong>the</strong><br />

core <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> moral and spiritual environment that we inhabit,<br />

grounded in God’s very being. When we love we are captivated by<br />

ano<strong>the</strong>r with spontaneous, joyful regard. The beloved’s needs,<br />

desires, and concerns become <strong>the</strong> center <strong>of</strong> attention that motivate<br />

and shape our involvement and relation to <strong>the</strong> beloved. Love’s<br />

activity and concern is always o<strong>the</strong>r-directed and always freely<br />

given. Love does not seek for <strong>the</strong> self, but for <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r (1 Cor 13:5).<br />

The second part is “law proper,” which was added because <strong>of</strong><br />

sin (Gal 3:19). It is <strong>the</strong> “you must—or perish.” Do it or die! Law<br />

proper places duty and obligation before us with <strong>the</strong> threatening<br />

penalty <strong>of</strong> death: a penalty that captivates us at <strong>the</strong> most fundamental<br />

level <strong>of</strong> our self-love and concern, our very well-being.<br />

Love is demanded under penalty <strong>of</strong> death. To serve <strong>the</strong> law is to<br />

enlist in <strong>the</strong> service <strong>of</strong> legal duty and to do so out <strong>of</strong> concern for<br />

<strong>the</strong> self, not concern for <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. Do what is required and you<br />

will live. In o<strong>the</strong>r words, your duty or your death! To be moved by<br />

legal necessity and <strong>the</strong> damning curse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law suffocates <strong>the</strong><br />

freedom and spontaneity that love requires. When we are capti-

THE TWO-FACED GOD 7<br />

vated and driven by <strong>the</strong> law, <strong>the</strong>re can be no love, but when we<br />

are grasped by love, <strong>the</strong> law’s demands and threats evaporate.<br />

Indeed, <strong>the</strong>y can even seem silly.<br />

Imagine strolling in a park and spotting a young couple sitting<br />

on a bench. As you watch <strong>the</strong>m out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> corner <strong>of</strong> your eye for<br />

several minutes, it becomes obvious that <strong>the</strong>y are deeply in love<br />

with one ano<strong>the</strong>r. You can tell just by noticing how <strong>the</strong>y look at<br />

one ano<strong>the</strong>r. Now imagine going up to <strong>the</strong>m and saying, “Surely<br />

you realize that you must love each o<strong>the</strong>r. It’s <strong>the</strong> law!” They would<br />

look at you as though you were crazy, would <strong>the</strong>y not Surely <strong>the</strong>y<br />

would wonder, “How must we do what we simply cannot help but<br />

do” Love’s compulsion is tied to <strong>the</strong> beloved, but never legal<br />

necessity. Where <strong>the</strong>re is love, <strong>the</strong> force and compulsion <strong>of</strong> legal<br />

necessity are not only absent; to lovers <strong>the</strong>y seem ridiculous.<br />

It was again Kierkegaard who understood that <strong>the</strong> two elements,<br />

love and law, have a paradoxical “hide-and-seek” relationship<br />

with one ano<strong>the</strong>r. If you encounter one, <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r is in hiding<br />

and nowhere to be found. If you experience <strong>the</strong> demand—<br />

“you must”—love is absent and nowhere to be seen. If love is a<br />

present flowing reality, <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> law has disappeared from view.<br />

Yes, love is <strong>the</strong> law <strong>of</strong> life, but love and law are never experienced<br />

toge<strong>the</strong>r, for like oil and water <strong>the</strong>y repel each o<strong>the</strong>r in our experience<br />

<strong>of</strong> each. We are ei<strong>the</strong>r grasped by <strong>the</strong> necessity <strong>of</strong> doing our<br />

duty for our own good, or we are captivated by love and what is<br />

good for <strong>the</strong> beloved.<br />

Let’s explore <strong>the</strong> paradox fur<strong>the</strong>r. It is certainly true that we are<br />

always capable <strong>of</strong> being more kind and considerate <strong>of</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rs than<br />

we have been, and we corrupt ourselves if we do not even try.<br />

Moreover, we will never love unless we make a conscious effort.<br />

Never<strong>the</strong>less, deliberately striving to love people will not accomplish<br />

<strong>the</strong> goal. Love is a fruit, not a work. Where love exists. it<br />

spontaneously carries its own burden for <strong>the</strong> beloved without<br />

strife or any sense <strong>of</strong> legal compulsion. The law <strong>of</strong> love presents<br />

sinful humans with a paradoxical dilemma, a moral and spiritual<br />

“catch-22.” The paradox can be illustrated by <strong>the</strong> example <strong>of</strong> a<br />

painter who deliberately tries to become a great artist. If he does<br />

not strive, he will never become an artist, much less a great one.<br />

But since he makes genius in his craft a deliberate goal <strong>of</strong> striving,<br />

he proves he is not and never will be a genius. Great artists are<br />

such without striving. Their abilities simply unfold in <strong>the</strong>ir work<br />

like <strong>the</strong> petals <strong>of</strong> a rose before <strong>the</strong> sun. Genius is a gift <strong>of</strong> God; it is<br />

not a work; and so also is love. Love blossoms from a grace-nourished<br />

faith in <strong>the</strong> Christian life as faith is exercised in our relations<br />

with o<strong>the</strong>rs. If we do not strive to love with all that is in us, we<br />

surely condemn ourselves. But on <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, love is not ours<br />

for <strong>the</strong> striving. Moreover, love is our duty, but we can never love<br />

when we are driven by a sense <strong>of</strong> that duty.<br />

Imagine that a husband confesses to his wife that he has been<br />

striving to love her for <strong>the</strong> past ten years and that he plans to<br />

redouble his efforts in <strong>the</strong> coming year. Has he not confessed to<br />

her that he hasn’t loved her in years, that he doesn’t love her now,<br />

and for that matter, he can’t If you were his wife, what would you<br />

say to him Are we not tempted to tell this man to please stop<br />

But isn’t it also true that he would stand self-condemned before<br />

his wife if he confessed to her that he doesn’t love her and, for that<br />

matter, he isn’t even going to try Catch-22! Checkmate! The husband<br />

is damned if he tries and damned if he doesn’t.<br />

Consider a second example from <strong>the</strong> late Edward John Carnell.<br />

Imagine that it is a husband’s first wedding anniversary and he<br />

knows how much his wife loves roses. He stops <strong>of</strong>f after work and<br />

picks up a dozen beautiful, long-stemmed, dew-dripping roses<br />

and presents <strong>the</strong>m to her when he arrives home. She naturally is<br />

touched by his thoughtfulness and responds with warm and<br />

affectionate gratitude. What would be her reaction, however, if in<br />

<strong>the</strong> middle <strong>of</strong> her thank-yous he were to say; “Think nothing <strong>of</strong> it<br />

honey, I’m just doing my duty” Do we not clearly see that <strong>the</strong><br />

more committed he becomes by doing his duty, <strong>the</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>r his<br />

heart and life will travel from real love Checkmate again! He<br />

must love his wife; it is his duty. But <strong>the</strong> more motivated he<br />

becomes to doing his duty, <strong>the</strong> more he destroys <strong>the</strong> possibility <strong>of</strong><br />

ever loving her. Duty damns if we do it, and it damns if we don’t,<br />

for both destroy love.<br />

The law <strong>of</strong> love presents sinful humans<br />

with a paradoxical dilemma, a moral<br />

and spiritual “catch-22.”<br />

nb<br />

Love is not ours for <strong>the</strong> striving, nor ours for <strong>the</strong> refusal to strive.<br />

Love is our duty under <strong>the</strong> law, but commitment to duty and all<br />

legal considerations void and destroy love. When we are captivated<br />

by <strong>the</strong> law, <strong>the</strong>re is no love. The law always reveals where we don’t<br />

and can’t. We both understand and sympathize with <strong>the</strong> reactions<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> wife in our illustrations. And <strong>the</strong>refore, we also understand<br />

<strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> God. Love is a fruit <strong>of</strong> faith empowered by grace,<br />

where, <strong>of</strong> course, <strong>the</strong> law has been abolished and is nowhere to be<br />

found. The words <strong>of</strong> St. Paul in Romans 3:19 speak to us:<br />

Now we know that whatever <strong>the</strong> law says, it speaks to those<br />

who are under <strong>the</strong> law, that every mouth may be closed and<br />

all <strong>the</strong> world may become accountable to God; because by<br />

<strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law no flesh will be justified in his sight; for<br />

through <strong>the</strong> law comes <strong>the</strong> knowledge <strong>of</strong> sin.”<br />

This is God’s central purpose <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law. He did not intend it to<br />

be ei<strong>the</strong>r a motivational tool to nurture a true loving heart from<br />

one <strong>of</strong> selfishness and pride, nor did he intend it to be an exercise<br />

guide that would enable <strong>the</strong> practitioner <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> “ten principles” to<br />

advance in <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> loving. When God added <strong>the</strong> law to his creative<br />

design <strong>of</strong> love, he provided a potent diagnostic tool to set in<br />

bold relief our spiritual deadness and <strong>the</strong> impossibility <strong>of</strong> transforming<br />

ourselves back into his original plan for us in creation.<br />

Love was <strong>the</strong> constant condition <strong>of</strong> human existence in paradise<br />

until Adam and Eve exchanged <strong>the</strong>ir trust in God for trust in<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves. When <strong>the</strong>ir trust was destroyed, <strong>the</strong> full contours <strong>of</strong><br />

love evaporated with it. At its core, human capacity became<br />

bankrupt <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> spiritual resources to center our existence around<br />

a whole-being love and trust in God. Such an existence was paradise,<br />

but paradise was lost. The law was given to show <strong>the</strong> sons<br />

and daughters <strong>of</strong> Adam that we have no resources within our-

8 LOGIA<br />

selves to return to paradise. Moral necessity coupled with <strong>the</strong><br />

threat <strong>of</strong> death will not generate ei<strong>the</strong>r love or trust in God.<br />

Attempts to enlist <strong>the</strong> law to do so will only generate a false selfrighteousness<br />

or full-scale rebellion.<br />

The truth about us seen in <strong>the</strong> law at full strength is painfully<br />

hard to receive. All <strong>of</strong> our pride and sense <strong>of</strong> fleshly well-being is<br />

crushed by <strong>the</strong> verdict it pronounces. It pushes us to a level <strong>of</strong><br />

self-honesty that we know would spell <strong>the</strong> end to all our selfmade<br />

“I’m-doing-O.K.” faces. It destroys all plans and pretensions<br />

<strong>of</strong> self-justification by doing our duty. The law condemns<br />

us! We can be easily tempted to turn away from <strong>the</strong> full impact <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> law and try to negotiate with its demands. Some popular ways<br />

include making <strong>the</strong> demands <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law into goals as if <strong>the</strong> law is<br />

saying, “Become <strong>the</strong> person who can love God with all heart,<br />

mind, and soul, and neighbor as self, and you will live.” Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

is, “Make steady improvement in <strong>the</strong> art <strong>of</strong> loving and you will<br />

live.” And, <strong>of</strong> course, <strong>the</strong>re is <strong>the</strong> popular old standby, “Be more<br />

loving <strong>the</strong>n most <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> people you know and you will live.”<br />

All <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se pretentious evasions deny <strong>the</strong> full thrust <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law,<br />

which proclaims that if we have not already and always been loving<br />

God with everything that is in us and o<strong>the</strong>r humans as ourselves,<br />

<strong>the</strong>n we are dead in our trespasses already. Dead people cannot<br />

do anything; <strong>the</strong>y are out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> running! This is <strong>the</strong> curse <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> law (Gal 3:10). To finally hear this chilling truth from <strong>the</strong> God<br />

who pronounces it places <strong>the</strong> sinner under <strong>the</strong> wrath <strong>of</strong> God at a<br />

critical juncture. Ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> sinner will become infuriated or broken.<br />

Ei<strong>the</strong>r one will say from <strong>the</strong> heart, “To hell with <strong>the</strong> law!”<br />

and run from God to greater levels <strong>of</strong> loveless rebellion, or God<br />

will turn <strong>the</strong> individual down <strong>the</strong> crushing road <strong>of</strong> repentance.<br />

Here he wants to fashion <strong>the</strong> humble, honest face that can meet<br />

<strong>the</strong> gracious God who saves. It is a face that recognizes <strong>the</strong> need<br />

for righteousness, love, and unconditional acceptance. God meets<br />

<strong>the</strong>se needs in <strong>the</strong> gospel by clothing our barren and sinful condition<br />

with <strong>the</strong> righteousness <strong>of</strong> Christ and recreating our face and<br />

our whole spiritual being into a likeness <strong>of</strong> his Son. Through faith<br />

in Christ we now have a face fit not simply to meet our God, but<br />

to belong to him in love as his bride forever.<br />

THE CHEMISTRY OF LAW AND GOSPEL<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> us who have taken Chemistry 101 in high school or college<br />

can recall that <strong>the</strong>re is an interesting polarity in chemical<br />

substances. Some are acidic to various degrees and o<strong>the</strong>rs are<br />

alkaline or base in nature. Water apparently is neutral. Perhaps we<br />

also remember what happens if we mix acid into an alkaline solution<br />

or visa versa. Each has <strong>the</strong> effect <strong>of</strong> weakening <strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r, and if enough is added, eventually it will neutralize <strong>the</strong><br />

entire strength <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> solution. And water, as we know, is <strong>the</strong> universal<br />

solvent. It dilutes <strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong> both. I’m no chemist, but<br />

perhaps we could say that if we need full-strength acid, alkaline<br />

solutions are hazardous if mixed in. They will contaminate by<br />

producing a neutralizing effect, and <strong>the</strong> same <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r way<br />

around. Moreover, if, for example, we need both full-strength<br />

acid and alkaline solutions, water could be considered a contaminant<br />

because <strong>of</strong> its effect <strong>of</strong> diluting <strong>the</strong> strength <strong>of</strong> both.<br />

There are some useful contact points here for understanding<br />

<strong>the</strong> nature and ministry <strong>of</strong> God’s law and gospel. I do not know<br />

who <strong>the</strong> chemist was who is responsible for discovering <strong>the</strong> dual-<br />

ity and polarity <strong>of</strong> substances in terms <strong>of</strong> base and acid and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

effects upon one ano<strong>the</strong>r. But it was especially <strong>the</strong> insight <strong>of</strong><br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>r that refreshed western Christian thinking by <strong>the</strong> rediscovery<br />

that God’s word is rightly understood and divided by distinguishing<br />

between two different words or ministries <strong>of</strong> God, law<br />

and gospel. This is <strong>the</strong> central key that unlocks <strong>the</strong> true meaning<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scriptures and enables us to hear <strong>the</strong> voice <strong>of</strong> God through<br />

<strong>the</strong>m aright. From Genesis to Revelation, God addresses us in<br />

some places with a word that is law and o<strong>the</strong>r places with gospel.<br />

And like base and acidic solutions, each has its own unique properties<br />

and characteristics that God might accomplish his purposes<br />

with us through <strong>the</strong>m, yet each also has <strong>the</strong> power to contaminate<br />

and neutralize <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r if <strong>the</strong>y are mixed. Kept separate and at<br />

full strength, however, <strong>the</strong>y are powerful and potent instruments<br />

that, when properly applied, carry out all <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> things that God<br />

would accomplish in our lives for our ultimate salvation.<br />

We know from our own experience and from history that <strong>the</strong><br />

right words spoken at <strong>the</strong> right time to <strong>the</strong> right people can<br />

have amazing and powerful effects for good and ill. As <strong>the</strong> wise<br />

proverb says, “The pen is mightier than <strong>the</strong> sword.” By <strong>the</strong> right<br />

word under <strong>the</strong> right conditions whole nations and peoples<br />

have been moved to accomplish what was thought to have been<br />

impossible. Think <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> famous words <strong>of</strong> John Paul Jones during<br />

<strong>the</strong> American Revolution, or <strong>the</strong> inspiring words <strong>of</strong> Winston<br />

Churchill during <strong>the</strong> Battle <strong>of</strong> Britain. Or think <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> simple<br />

words “I love you,” magically spoken at <strong>the</strong> right time and place,<br />

which transformed <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> an indifferent beloved, creating a<br />

love-relationship that everyone including <strong>the</strong> beloved thought<br />

impossible. But now <strong>the</strong> beloved sheepishly and with much chagrin<br />

confesses, “I don’t know what happened, but I have fallen<br />

in love.”<br />

We know <strong>the</strong> power <strong>of</strong> mere human words. Imagine by comparison<br />

<strong>the</strong> incredible power that God’s word possesses. The<br />

entire universe was created by it! The Lord tells us that it never<br />

returns to him void, but always accomplishes <strong>the</strong> purposes for<br />

which he sends it forth (Is 55:11). He has entrusted his powerful<br />

Word <strong>of</strong> law and gospel to us. We would be his arms, legs, and<br />

mouth to proclaim his Word <strong>of</strong> law and gospel, through which he<br />

meets sinners face to face for <strong>the</strong>ir salvation (Mt 28:20; Jn 15:27).<br />

The crucial thing, however, is that <strong>the</strong>se words must be delivered<br />

unmixed and at full strength, or potency is diminished, <strong>the</strong> power<br />

is neutralized, and <strong>the</strong> true face <strong>of</strong> God as he would reveal himself<br />

to us evaporates.<br />

Full-Strength Law<br />

Let’s examine this more closely beginning with law, God’s<br />

preparatory meeting and ministry for <strong>the</strong> saving encounter<br />

through <strong>the</strong> gospel. The law is always preliminary and preparatory.<br />

Full-strength and pure law is <strong>the</strong> unconditional demand first<br />

to love God with all our heart, mind, and soul. This demand, as<br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>r recognized, means that we are to “fear, love, and trust in<br />

God above all things.” Second, <strong>the</strong> law demands that we love o<strong>the</strong>rs<br />

when <strong>the</strong>y enter our circle <strong>of</strong> nearness as we love ourselves.<br />

This fully potent law is to be poured into <strong>the</strong> hearts and minds <strong>of</strong><br />

complacent sinners to produce <strong>the</strong> awareness <strong>of</strong> moral and spiritual<br />

bankruptcy—<strong>the</strong> checkmate <strong>of</strong> “I must” joined to “I don’t<br />

and I can’t.” Remember, God’s purpose here is to reveal his just

THE TWO-FACED GOD 9<br />

wrath and judgment, and in our despair <strong>of</strong> self-righteousness to<br />

fashion <strong>the</strong> honest face <strong>of</strong> a repentant heart. The law exposes and<br />

condemns our false gods, our self-made plans <strong>of</strong> well-being, and<br />

our selfish, loveless treatment <strong>of</strong> God and our neighbor.<br />

But what happens if <strong>the</strong> law is not at full strength What if it is<br />

mixed with elements <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel or simply watered down<br />

What if <strong>the</strong> word we convey is a “you must,” but we join it to <strong>the</strong><br />

message that God is kind and merciful, so an honest sincere<br />

effort will do Sincere, honest effort is something that we can<br />

muster through striving and a commitment to duty. Here a true<br />

encounter with <strong>the</strong> holy and righteous God is neutralized and<br />

repentance is not produced. The face <strong>of</strong> God here is a false face—<br />

it reveals nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> God who condemns nor <strong>the</strong> God who saves<br />

through Christ.<br />

Dead people cannot do anything;<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are out <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> running! This<br />

is <strong>the</strong> curse <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law.<br />

nb<br />

Or consider <strong>the</strong> more common error <strong>of</strong> reducing <strong>the</strong> law to<br />

simply a list <strong>of</strong> moral dos and don’ts—a plan for how we ought to<br />

behave in daily living. What happens if we present <strong>the</strong> law only in<br />

terms <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> outward dimensions <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Ten Commandments<br />

Do we swear, lie, cheat, or steal Which <strong>of</strong> us can claim a clean<br />

slate here Never<strong>the</strong>less, we have certainly watered down <strong>the</strong> law<br />

<strong>of</strong> love, <strong>the</strong> law <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spirit <strong>of</strong> life. We have reduced it to outward<br />

do-ability. The power is gone.<br />

The law as moral principle may indeed reveal immorality on<br />

our part, but it cannot reveal our true condition <strong>of</strong> moral bankruptcy<br />

and spiritual deadness. It may confront us with occasional<br />

or frequent “I don’ts” for which we may sense a responsibility to<br />

apologize—as we <strong>of</strong>ten do to one ano<strong>the</strong>r—but mere moral<br />

principle will never bring anyone to <strong>the</strong> dead-end checkmate <strong>of</strong> “I<br />

can’t.” There is room to maneuver with mere moral principles <strong>of</strong><br />

duty on <strong>the</strong> legal plane <strong>of</strong> give-and-take. We know in advance<br />

that a sincere apology must be accepted and we can always renew<br />

our commitment and hope to do better in <strong>the</strong> future.<br />

Moralizing will never reveal <strong>the</strong> God who condemns, nor will<br />

it ever produce true repentance. We apologize for <strong>the</strong> things we<br />

have done, but we repent for <strong>the</strong> person we have been. Only fullstrength<br />

law destroys <strong>the</strong> hope <strong>of</strong> self-righteousness and lays us<br />

open to see <strong>the</strong> true depths <strong>of</strong> our spiritual poverty. It is God’s<br />

checkmate that produces repentance and <strong>the</strong> honest face that recognizes<br />

<strong>the</strong> need for a gracious God. Anything less turns <strong>the</strong> good<br />

news into ordinary news or no news at all.<br />

Full-Strength Gospel<br />

Let’s turn our attention now to <strong>the</strong> ministry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel.<br />

Question: What is <strong>the</strong> difference between receiving <strong>the</strong> largest,<br />

most valuable diamond in <strong>the</strong> world as a free gift and getting it<br />

for a penny If we look at it on <strong>the</strong> surface, <strong>the</strong> difference is not<br />

very much at all, just a mere penny. But let’s look at this more<br />

closely. In <strong>the</strong> first instance we have a gift, and quite a gift at that.<br />

What do we have, however, in <strong>the</strong> second instance Is it not true<br />

that what we have here is an incredible bargain Notice <strong>the</strong> big<br />

difference. Great gifts are expressions and signs <strong>of</strong> great love, if<br />

indeed <strong>the</strong>y are true gifts. The giving <strong>of</strong> gifts is <strong>the</strong> way persons,<br />

both human and divine, express <strong>the</strong>ir love for one ano<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Incredible bargains are different. They are usually expressions <strong>of</strong><br />

deception, stupidity, or shrewd business enterprise at work. How<br />

many things do we get in <strong>the</strong> mail every week that trumpet<br />

incredible bargains and <strong>of</strong>ten with <strong>the</strong> word FREE! scrawled in<br />

big, bold print. But, as it is said, let <strong>the</strong> buyer beware! We usually<br />

get what we pay for, don’t we Has experience not taught us that<br />

<strong>the</strong>re is a world <strong>of</strong> difference between a bargain—no matter how<br />

great it may seem—and a true gift. Genuine gifts are expressions<br />

<strong>of</strong> love; bargains are not.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> most common words used to express <strong>the</strong> gospel in<br />

<strong>the</strong> New Testament is <strong>the</strong> word grace. It means gift. Full-strength<br />

gospel proclaims <strong>the</strong> good news <strong>of</strong> a priceless gift that <strong>the</strong> gracious<br />

God who loves us has appropriated and gives to us for <strong>the</strong><br />

sake <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> saving work <strong>of</strong> his Son’s death and resurrection. It is<br />

<strong>the</strong> gift <strong>of</strong> righteousness, forgiveness, reconciliation. It is <strong>the</strong> gift<br />

<strong>of</strong> secured unconditional acceptance now and forever. It is <strong>the</strong> gift<br />

<strong>of</strong> freedom, new life, and adoption into <strong>the</strong> family <strong>of</strong> God. It is<br />

<strong>the</strong> gift <strong>of</strong> well-being now and forever. Pure gospel brings us face<br />

to face with <strong>the</strong> loving God who, through his Son and with this<br />

grace, brings us back into <strong>the</strong> most beautiful love-relationship<br />

and matures our faith and love into <strong>the</strong> full stature <strong>of</strong> his Son.<br />

But what happens to this precious gift if law is mixed into <strong>the</strong><br />

gospel or if it is diluted What if we attach to <strong>the</strong> gift <strong>the</strong> requirement<br />

that we love him or our neighbor, even if just a little bit Why,<br />

that’s not asking much for such a priceless treasure as eternal life!<br />

Do you see what has happened The gift has evaporated and we<br />

now have a bargain, perhaps even a good one, but <strong>the</strong>re is no<br />

longer <strong>the</strong> gift. Moreover, we have turned <strong>the</strong> face <strong>of</strong> our gracious,<br />

loving God into a cosmic businessman or huckster who is out marketing<br />

his spiritual wares for a little virtue or affection. Any amount<br />

or aspect <strong>of</strong> law will neutralize <strong>the</strong> grace <strong>of</strong> God and diminish <strong>the</strong><br />

power <strong>of</strong> God unto salvation. Can anyone bargain for your love<br />

God’s love and gifts can never be had for a bargain ei<strong>the</strong>r.<br />

Let’s look at this also from our standpoint. In our example, <strong>the</strong><br />

bargain <strong>of</strong> a happy forever only requires that you love a little bit.<br />

Will we ever have any assurance <strong>of</strong> a happy forever How much<br />

does God think is a “little bit” Have we provided enough yet, or<br />

is more needed How will we ever know, until, <strong>of</strong> course, it is too<br />

late And what about <strong>the</strong> quality <strong>of</strong> our love How good does it<br />

have to be Is ours good enough Who knows Even a little bit <strong>of</strong><br />

law can rob us <strong>of</strong> all assurance and confidence that <strong>the</strong> blessings<br />

<strong>of</strong> God are truly ours. And if our happy forever is on <strong>the</strong> line,<br />

what means everything to us finally ends up depending on mere<br />

whistling in <strong>the</strong> dark. From our perspective, bargains from God<br />

<strong>of</strong>fer no confidence or peace where we need it most: our present<br />

and future well-being.<br />

GROWTH IN CHRIST<br />

When I was a young boy and would drift <strong>of</strong>f aimlessly in <strong>the</strong> middle<br />

<strong>of</strong> doing my homework from school or some chore I was<br />

expected to do, my fa<strong>the</strong>r was usually close at hand and did his

10 LOGIA<br />

best to get me back on track. One <strong>of</strong> his favorite words <strong>of</strong> advice<br />

on such occasions was, “Son, what you need here is to get your<br />

head on straight.” Oh, how many times did I hear <strong>the</strong>se words<br />

growing up! Sometimes it seemed to me that my major problem<br />

in life, from my dad’s perspective, was a continually <strong>of</strong>f-center<br />

head that was forever needing readjustment.<br />

Now, many years later, I think that our heavenly Fa<strong>the</strong>r is in<br />

total agreement with my dad. He echoes <strong>the</strong> same words <strong>of</strong> advice<br />

for me and all his children in his Word when it comes to <strong>the</strong> tasks<br />

and challenges <strong>of</strong> Christian living. In 1 Peter he exhorts us to “gird<br />

our minds for action.” David tells us in Psalm 7 that “<strong>the</strong> righteous<br />

God tries <strong>the</strong> heart and mind” <strong>of</strong> all <strong>of</strong> us. Being “rightminded”<br />

or in <strong>the</strong> right mind is <strong>of</strong> great importance for living<br />

and growing in Christ.<br />

Mind Renewal<br />

The Christian as new creation and fleshly self really has a duality<br />

in <strong>the</strong> mind, two minds, so to speak. Paul exhorts us to put<br />

our heads on straight because “<strong>the</strong> mind set on <strong>the</strong> flesh is death”<br />

and “hostile to God,” but <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> Christ or <strong>the</strong> “mind set on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spirit is life and peace” (Rom 8:6). When we are drifting <strong>of</strong>f in<br />

<strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flesh, our heads are not on straight, and we need<br />

to make <strong>the</strong> adjustment <strong>of</strong> putting on <strong>the</strong> new self and <strong>the</strong>n walk<br />

in <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> Christ.<br />

In Ephesians 4, Paul reminds us that <strong>the</strong>re are two things that<br />

we need to do continually in order to mature in Christ and fight<br />

<strong>the</strong> inner war that is a part <strong>of</strong> our daily Christian living. The first<br />

is to get our heads on straight by putting on <strong>the</strong> new self. The<br />

second is mind renewal—to “be renewed in <strong>the</strong> spirit <strong>of</strong> [our]<br />

mind.” Both tasks are also emphasized in Romans 12: “Do not be<br />

conformed to this world, but be transformed by <strong>the</strong> renewing <strong>of</strong><br />

your mind.” And <strong>the</strong> purpose <strong>of</strong> this mind renewal “So we can<br />

prove what <strong>the</strong> will <strong>of</strong> God is, that which is good and acceptable<br />

and perfect.”<br />

If, as a boy, my dad was always exhorting me to get my head on<br />

straight, I must confess that ins<strong>of</strong>ar as that was actually accomplished,<br />

he must be credited (toge<strong>the</strong>r with Mom) with performing<br />

<strong>the</strong> lion’s share <strong>of</strong> that task. And though I needed <strong>the</strong>m, his<br />

words sometimes were very hard and painful to receive. Likewise,<br />

our Heavenly Fa<strong>the</strong>r, exhorting us in much <strong>the</strong> same way, carries<br />

out, through his Son, <strong>the</strong> lion’s share <strong>of</strong> mind adjustment and<br />

renewal that he commands <strong>of</strong> us. And again we see ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

instance <strong>of</strong> what God commands, God produces. He works in <strong>the</strong><br />

Christian life continually to get our heads on straight—casting<br />

<strong>of</strong>f <strong>the</strong> fleshly mind, putting on <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> Christ—and <strong>the</strong>n he<br />

renews and matures that mind.<br />

Applying Law and Gospel<br />

Our Lord does all this by <strong>the</strong> Holy Spirit through his ministry<br />

<strong>of</strong> law and gospel in <strong>the</strong> word and sacraments. Through<br />

<strong>the</strong> law at full strength, he exposes our fleshly self-made plans<br />

for acceptability and secure personal well-being and condemns<br />

<strong>the</strong>m for <strong>the</strong> idolatrous and unworkable plans that <strong>the</strong>y are.<br />

The real checkmate here is not simply that <strong>the</strong>y are wrong.<br />

Ra<strong>the</strong>r, it is that <strong>the</strong>y don’t work and can’t work, and those who<br />

rely and trust in such plans are not just wrong, <strong>the</strong>y are dead.<br />

This is full-strength law!<br />

The most penetrating law is that which is directed not to our<br />

behavior, but to <strong>the</strong> core <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fleshly self that is in <strong>the</strong> mind and<br />

heart. That is where <strong>the</strong> rebellious strategies and goals are lodged,<br />

formulated, and energized for action. It is on <strong>the</strong> level <strong>of</strong> fleshly<br />

belief, hope, and trust that <strong>the</strong> law must be applied. A mere<br />

behavioral application can <strong>of</strong>ten end up as moralizing, and <strong>the</strong><br />

sinful self can easily adapt to a certain modicum <strong>of</strong> nice, moral<br />

living. And in Christians it <strong>of</strong>ten does!<br />

We need to be clear about God’s objectives here as we battle <strong>the</strong><br />

flesh. God’s ministry <strong>of</strong> law in <strong>the</strong> life <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Christian is not to<br />

reform <strong>the</strong> fleshly self. He is out to kill it. Paul exhorts us to mortify<br />

and crucify <strong>the</strong> flesh. Kill it! Remember, <strong>the</strong> heart and mind<br />

<strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> fleshly self is organized around a rebellious answer and<br />

strategy to solve <strong>the</strong> problem <strong>of</strong> existence itself, personal wellbeing:<br />

What do we need that we might be secure and acceptable<br />

human beings, and what can we do for significant, meaningful<br />

impact in life How <strong>the</strong> fleshly self in each one <strong>of</strong> us frames out<br />

answers to this is ground-point zero where full-strength law<br />

needs to be directed and applied again and again.<br />

What does effective ministry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law do for <strong>the</strong> new self<br />

Nothing in any direct way, but it does create a powerful hunger<br />

and thirst for our Lord’s bread <strong>of</strong> life and living water <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

gospel. The law itself imparts no spiritual nutrition or power for<br />

Christian living, but it is God’s great appetite builder that sends<br />

us running for <strong>the</strong> word <strong>of</strong> life. And <strong>the</strong> ministry <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel is<br />

how our Lord feeds <strong>the</strong> new creation to sustain and mature our<br />

faith and life in Christ. The cutting edge <strong>of</strong> this building up<br />

through <strong>the</strong> gospel involves <strong>the</strong> Spirit’s work <strong>of</strong> mind renewal for<br />

development and maturity.<br />

There is ano<strong>the</strong>r paradox here. Full-strength gospel can <strong>of</strong>ten<br />

be <strong>the</strong> simple gospel: “You are forgiven, God loves you and<br />

accepts you just as you are for <strong>the</strong> sake <strong>of</strong> Christ.” Or even, “Jesus<br />

loves me, this I know, for <strong>the</strong> Bible tells me so.” For our little ones<br />

in Christ we must take care to feed <strong>the</strong>m continually with <strong>the</strong><br />

pure milk <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel. And sometimes <strong>the</strong> simple gospel is what<br />

we need, just <strong>the</strong> plain but full-strength words, “you are forgiven.”<br />

Yet it is also true that <strong>the</strong> gospel is not simple. There is<br />

more to it in its implications and applications than we will ever<br />

grasp in this life.<br />

As we grow and mature in Christ, <strong>the</strong> Lord also intends for us<br />

to feed on <strong>the</strong> “meat and potatoes,” indeed, <strong>the</strong> whole nine<br />

courses <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel, not simply <strong>the</strong> milk and pabulum. The<br />

Spirit is working through word and sacrament to renew our<br />

minds and hearts to <strong>the</strong> full stature <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> Christ himself.<br />

And we need this mature understanding and trust <strong>of</strong> faith to handle<br />

<strong>the</strong> front lines <strong>of</strong> Christ’s warfare with <strong>the</strong> powers <strong>of</strong> darkness<br />

in our lives and in <strong>the</strong> world: maturity for battle and service at <strong>the</strong><br />

tough outposts <strong>of</strong> life. The milk and pabulum <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> gospel alone<br />

will not provide that kind <strong>of</strong> growth and equipping. With a fullorbed<br />

gospel <strong>the</strong> new creation becomes progressively built up for<br />

a fuller and deeper flow <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> love and ministry <strong>of</strong> Christ<br />

through us to those he gives us opportunity to serve. LOGIA<br />

NOTE<br />

* Paraphrase <strong>of</strong> Søren Kierkegaard, Philosophical Fragments, pp. 31–43,<br />

by Philip Yancy, Disappointment with God (Grand Rapids: Zondervan<br />

Publishing House, 1988), 103–104.

Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s Augustinian Understanding <strong>of</strong> Justification<br />

in <strong>the</strong> Lectures on Romans<br />

AUGUSTINE’S STRUGGLE AGAINST PELAGIUS has direct bearing<br />

upon Lu<strong>the</strong>r’s <strong>the</strong>ology. In his Lectures on Romans,<br />

Lu<strong>the</strong>r draws heavily on Augustine, citing mostly his anti-<br />

Pelagian writings. Of <strong>the</strong>se writings, Augustine’s De spiritu et littera<br />

plays <strong>the</strong> greatest role. 1 Lu<strong>the</strong>r refers to it throughout his<br />

comments on <strong>the</strong> first seven chapters. 2 This phenomenon invites<br />

investigation concerning <strong>the</strong> influence <strong>of</strong> De spiritu et littera on<br />

<strong>the</strong> Romans lectures. Does Lu<strong>the</strong>r adopt Augustine’s distinction<br />

between Spirit and letter If so, what influence does it have on his<br />

understanding <strong>of</strong> justification<br />

SPIRIT AND LETTER<br />

It may be helpful first to articulate Augustine’s view <strong>of</strong> Spirit and<br />

letter in De spiritu et littera. The passage <strong>of</strong> Scripture to which<br />

Augustine appeals is 2 Corinthians 3:6: “for <strong>the</strong> letter kills, but <strong>the</strong><br />

Spirit gives life.” 3 Augustine had once understood this passage as<br />

a license to allegorize. The literal meaning <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Scriptures kills,<br />

so one should seek <strong>the</strong> spiritual meaning.³ But he rejects that<br />

opinion in De spiritu et littera, or at least relegates it to a secondary<br />

place. His new understanding is that <strong>the</strong> letter is <strong>the</strong> law<br />

(which kills), while <strong>the</strong> Spirit is <strong>the</strong> Holy Spirit who heals <strong>the</strong> sinner<br />

and enables him to keep <strong>the</strong> law.<br />

The law kills because it is external. Its demands can be kept<br />

externally, but <strong>the</strong> law lacks <strong>the</strong> power to enable one to do <strong>the</strong>se<br />

works from <strong>the</strong> heart. Augustine states,<br />

Even those who did as <strong>the</strong> law commanded, without <strong>the</strong><br />

help <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spirit <strong>of</strong> grace, did it through fear <strong>of</strong> punishment<br />

and not from love <strong>of</strong> righteousness [amore iustitiae]. 4<br />

Augustine here identifies <strong>the</strong> help <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spirit as <strong>the</strong> production<br />

<strong>of</strong> amor. For Augustine, <strong>the</strong> factor that determines whe<strong>the</strong>r a<br />

work is good or bad is not <strong>the</strong> external quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> work, but<br />

<strong>the</strong> internal disposition <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> one who does <strong>the</strong> work. Works that<br />

are not done from amor cannot be good works, and thus <strong>the</strong>y<br />

cannot give life. The distinction between Spirit and letter for<br />

Augustine is a distinction between internal and external. The law<br />

is external, while <strong>the</strong> Spirit, grace, and love are internal.<br />

Augustine does not think, however, that <strong>the</strong> letter and <strong>the</strong><br />

Spirit contradict or exclude each o<strong>the</strong>r. He stresses not only <strong>the</strong><br />

difference, but also <strong>the</strong> congruity (congruentia) <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Spirit with<br />

<strong>the</strong> letter. He finds evidence <strong>of</strong> this congruity in that <strong>the</strong>re were<br />

DAVID MAXWELL is an S. T. M. student at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis,<br />

Missouri.<br />

David Maxwell<br />

<br />

11<br />

fifty days between <strong>the</strong> Passover and Moses’ reception <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> law<br />

on Mt. Sinai just as <strong>the</strong>re were fifty days between Jesus’ death<br />

and resurrection and <strong>the</strong> coming <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Holy Spirit. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,<br />

<strong>the</strong> Holy Spirit, who is called <strong>the</strong> finger <strong>of</strong> God, wrote <strong>the</strong><br />

law on both occasions. In <strong>the</strong> Old Testament, he wrote it on<br />

stones; in <strong>the</strong> New Testament he wrote in on hearts. Augustine<br />

sums this up by saying,<br />

When, to put fear into <strong>the</strong> mind <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> flesh, <strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong><br />

charity [caritatis] are written upon tables, we have <strong>the</strong> law<br />

[lex] <strong>of</strong> works, <strong>the</strong> letter killing <strong>the</strong> transgressor: when charity<br />

[caritas] itself is shed abroad in <strong>the</strong> hearts <strong>of</strong> believers, we<br />

have <strong>the</strong> law [lex] <strong>of</strong> faith, <strong>the</strong> Spirit giving life to <strong>the</strong> lover<br />

[dilectorem]. 5<br />

The congruentia between <strong>the</strong> Spirit and <strong>the</strong> letter is reflected in<br />

that Augustine uses <strong>the</strong> same words to describe both. Both urge<br />

caritas. Both are lex. The only difference is that <strong>the</strong> letter is caritas<br />

written on tablets <strong>of</strong> stone (externally), while <strong>the</strong> Spirit is caritas<br />

written on <strong>the</strong> heart (internally).<br />

The congruity <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> letter and <strong>the</strong> Spirit makes possible an<br />

augmenting movement from <strong>the</strong> one to <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r. The Spirit does<br />