Memory-Insufficient-spec-alt

Memory-Insufficient-spec-alt

Memory-Insufficient-spec-alt

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Memory</strong><strong>Insufficient</strong>Games history ezineVolume twoIssue sixAlternative and<strong>spec</strong>ulative historiesof gamesJanuary 2015

Kill the pastLiberation maiden and destructive nostalgiaBenjamin GabrielApokalypsisRapture, death and mythmakingStephen WinsonGoing homeRepresentations of my residencesJefferson GeigerComrades in codeA short history of the gaming commonsShaun GreenAfter CyberSynChile’s department of simulation literatureDIY video game historyAdam FlynnRachel Simone WEIL

EditedbyRachel Simone Weiland Zoya StreetEditorialRachel Simone Weilnobadmemories.com@partytimeHXLNTRachel Simone Weil is an experimental videogame developer whose 8-bit NES cartridges playat the borders of fact and fiction.Alternative pasts,<strong>spec</strong>ulative futuresIn how many ways might the history of videogames and game cultures as we know them haveplayed out differently? How will video games affectus ten, twenty, or fifty years from now?This <strong>spec</strong>ial issue of <strong>Memory</strong> <strong>Insufficient</strong> focuseson <strong>alt</strong>ernative and <strong>spec</strong>ulative histories of games.The essays contained herein reimagine gaming’spast or dream of its possible futures. To be frank,the works in this issue can be challenging to read,as they dart between truth, fiction, and blends ofboth.

When curiosity gets the best of you, you may findyourself looking up dates, names, facts, and figuresto discover whether what you’re reading isreal or imagined. But it is good that these works arechallenging. They confuse our idea of video gamehistory as a stable collection of fact. They grant usthe opportunity to acknowledge how much of historyrelies on chance and invite us to play, quiteliterally, with history as we know it. They ask usto consider the anxieties we might face in the nearfuture and what role games might play.It is my hope that these feelingsof confusion and curiosity arecontagious, that they accompanyyour reading of all video gametexts so that you might call eachone into question.Like on FacebookSubscribe by emailrupazero.com<strong>Memory</strong> <strong>Insufficient</strong> is published on a CreativeCommons Attribution - Non-commercial -NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Blood and RosesMargaret Atwood andthe dystopian presentMichael Lyonsfb.com/HistoryBoys @queer_mikeyMichael Lyons is a queer-identified journalistfrom Toronto, Canada, a contributor to Xtra Magazine,half of the ‘History Boys’ column on LGBThistory, and Senior Writer for The Plaid Zebra.Warning: Mild to extreme spoilers for MargaretAtwood’s MaddAddam trilogy, discussion of violence,sexual violence against women, genocide.I’m sittingon a computer atschool, trying to calculatethe monetary worth of mass genocide incomparison to the value of famous works of art.Canadian author Margaret Atwood is to blame.“Blood and Roses was a trading game, along thelines of Monopoly,” Atwood writes. “The Bloodside played with human atrocities for the counters,atrocities on a large scale: individual rapesand murders didn’t count, there had to have

een a large number of people wiped out. Massacres,genocides, that sort of thing. The Roses sideplayed with human achievements. Artworks, scientificbreakthroughs, stellar works of architecture,helpful inventions. Monuments to the soul’smagnificence, they were called in the game.”I start with a Google search ofhow much the average person’slife is worth — a morbid exercisein itself.I find a LiveScience article titled “What’s the DollarValue of a Human Life?” that seems on the mark.This places a human life, from a safety analyst’sper<strong>spec</strong>tive, at $5 million, which is apparently aconservative estimate. This boggles my mind; Ialways thought life insurance paid out much lessthan this. After a brief fact-finding mission, thearcane machinations of modern insurance policiesstill escape me, so I’ll stick with $5 million/person. I decided to go with Bergen-Belsen as mytest genocide. About 35,000 people died in the Naziconcentration camp, which works out to about$175 billion by the safety analyst’s number.Pictured aboveNext, the worth of a famous work of art. Wikipediahelpfully tells me that the most ever paid fora piece of art in a private sale — with modern inflationtaken into account — was $274 million for‘The Card Players’ by Cézanne.I blink, my mind blanking for a second. That’sworth about 55 human lives by the $5 million estimate.That’s only equal to an École Polytechniquemassacre plus a Salem Witch hangings with a fewassassinations as spare change. A dozen Cézanneswouldn’t begin to match Bergen-Belsen, let alonethe Holocaust. You’d need more than three-anda-half‘The Card Players’ just to cancel out the200 killed in the Tiananmen Square protests of1989, and this doesn’t begin to take into accountany kind of monetary worth of the violation of hu-

man rights associated with the arrests and ensuingcrackdowns. Must we also assume that someindividual human lives — politicians or artistsor great thinkers — are worth more than, say, amodest grocer’s?How do you put a value on Einstein’sTheory of Relativity, orVirginia Woolf’s collected works,or the signature of Princess Enheduannacirca 2280 BCE?To think, all I’m trying to do is build a simple,workable paper prototype of Blood and Roses, avideo game described by Canadian author MargaretAtwood in her <strong>spec</strong>ulative fiction masterpiece,Oryx and Crake, the first in her MaddAddam trilogy.The series is a Swiftian journey into a strange andfrightening, though oddly familiar, near-futureEarth. Genetic engineering, bio-warfare, erodingdemocracy, amoral corporations, and a crumblingglobal environment all feature heavily. In her acknowledgementsof the culminating book, Madd-Addam, Atwood admits that the series “does notinclude any technologies or biobeings that do notalready exist, are not under construction, or are notpossible in theory.” Interactive media and videogames exist within Atwood’s delicious dystopianuniverse, and they serve a very <strong>spec</strong>ific purpose.I was inspired to think about this recently while enjoyinga Game Grumps “let’s play” video of PlagueInc., a mobile-turned-PC/console game whereyou lovingly parent an ever-evolving pathogen asit attempts to wipe out the entire human race. Itreminded me of the beginning of Oryx and Crake,which explains that the novel’s main character,Jimmy/Snowman, has parents who are bioengineersfor morally corrupt biomedical corporations.Jimmy has a fond memory of his mother teachinghim a scientific computer program that pits digital

cells against microbes: a cellular war game. What,I wonder, is the appeal of watching Greenland’slast living human die of a horrific disease as theentire country goes dark in Plague Inc.?On a close read of the Blood and Roses section of Oryxand Crake, it’s easy to think of other real-life videogames that are analogous to those presented inAtwood’s world. In my mind, Atwood’s KwiktimeOsama becomes a blood-soaked Call of Duty-styleFPS of “Infidels” versus “Extremists.” BarbarianStomp (See If You Can Change History!) is a customizablegame that pits civilized cities against savage,invading hordes. There’s an easy comparisonto be made with resource management strategygame series like Age of Empires and Civilization.Three-Dimensional Waco, which I only understoodas a reference to the Waco, Texas military siege ona second read, could easily be a mass-killing rampagegame in the vein of Far Cry, Grand Theft Autoor the virulently violent game Hatred.The aforementioned games, whether fictionalor real, share a few common elements: kill orbe killed, winners triumph over losers, murder asthe central mechanic and death of the opposingplayer(s) as the goal. Even as these series progressinto ever more graphically impressive games, oras we explore video games that are more aestheticallyelegant like Assassin’s Creed, Bioshock or FinalFantasy, violent conflict, battle, murder and deathare the fuel that keeps the proverbial engine going,and this is an industry norm.E<strong>spec</strong>ially as far as video gamesare concerned, we live in an author’sdystopian reality.There’s another dimension to interactive mediathat Atwood explores within MaddAddam.The third book describes the early life of Zeb, theabused son of a sadistic, petroleum-worshipping,fundamentalist Christian preacher-turned-mas-

tinuous loop.Jimmy and his friend play chess, the aforementionedBlood and Roses and another game: Extinctathon.Extinctathon is something like the game20 Questions, but about dead <strong>spec</strong>ies. Players takea codename that has to be a creature that wentextinct within the last 50 years—Pyrenean Ibex,Baiji Dolphin, Saint Helena Olive, Eastern Cougar,Western Black Rhinocerous or the Japanese RiverOtter, to name a few — and then engage withanother player to guess the identity of an extinct<strong>spec</strong>ies.This is also where the notion of video games as anextension of dystopia is turned on its head. Extinctathon,throughout the series, proves to be aplace of resistance, an Alice-Through-the-Looking-Glassadventure into a society of anti-corporatebioterrorists and eco-friendly hackers andgreen intelligence network operatives. The gatewayto this society, a form of resistance, hides inplain sight, masquerading as a game. While eachare monitored and administrated in various ways,Twitter, Tumblr, 4chan and Reddit can, for betteror for worse, feel like this; clandestine meetinggrounds in digital spaces, places where resistancecan occur just as easily as not.Extinctathon and Blood and Roses are the only of Atwood’sgames that I can’t really think of a real-lifecomparison to, hence I find myself sitting in myschool’s computer lab trying to come up with themechanics of a trading game that matches knowledgeof atrocities to human accomplishments.Atwood points out in her description of the game:“That was the trouble with Bloodand Roses: it was easier to rememberthe Blood stuff. The othertrouble was that the Blood player

#nodads 2024A history of trollingand hypervigilanceZoya Streetzoyastreet.com @rupazeroZoya Street is a freelance historian and journalistfrom Britain, living in the Bay Area. Heis the founder and editor of <strong>Memory</strong> <strong>Insufficient</strong>and author of Dreamcast Worlds and Delay.Originally published as an anonymous blog poston CryptoJournal in February 2024. Reprintedhere on a creative commons license.Earlierthis year, I found out that mydad is an internet troll. What’sworse is that he’s been one my whole life. Apparentlyit started withn imageboards in the 2000sand then moved into harassing feminist mediacritics in the 2010s.Twenty years of this shit! How did I not know untilnow? My parents, who were in the midst of sortingout the divorce they so desperately deserved,started up yet another raging fight.

And somehow the truth justspilled out: my dad is an internettroll.All those nights that Dad was hanging out in hisden? It turns out he was sending vile messagesto teen girls, girls my own age, maybe even girlswho I followed. He ran through burner accountsto send particularly threatening messages anonymously.I guess the threats are scarier somehowwhen they don’t have a face attached, when thereceiver knows that the sender could be anyone,anywhere. He kept a few pseudonymous accountsrunning, too, sending seemingly polite messagesat high volume that subtly undermined thereceiver’s self-esteem in little chunks at a time.He watched these girls break down publicly whiledrinking a beer after our family dinners together.Mom said that since Dad was my age, this had beenhis way of feeling connected to other people. Asmedia changed, his sense of being part of somethingbigger was made stronger. Old trolls actedalone. Back then, they acted in packs, each oneable to contribute a little piece that would add upto someone’s meltdown. Old trolls disappeared ifthey were not fed. But eventually, the trolls learnedto feed each other, to feed on the attention fromeach other and pat themselves on the back for ajob well done.Old trolls attacked forums. New trolls attackedpeople, targeting individuals on multiple platforms.I knew better than to be traceable like that. I learnedthat the hard way early on, when Dad found myfirst blog. He sent me an email with some choicequotes about people I had crushes on. “Don’t associateyour real name with stuff like that,” hesaid. “There are bad people out there.” He sentme selfies that he’d found of me, that I thoughtI’d posted under a pseudonym.

“You’ve got to learn how to makeyour face undetectable. And youshouldn’t be posting pictures atyour age. Have you any idea howdangerous this is?”A serial harasser, scolding me for making myself atarget to harassers. I suppose that’s how it works,right? He gets to feel that he’s protected his kid,and that if only other people weren’t so stupid asto use social media the way that it was designedto be used, they wouldn’t be so easily targeted byhim. Maybe in his mind he was doing them a favourtoo, by teaching them to be hypervigilant.How did he find those selfies of me, though? I figuredit out years later. His implant sends images toa server with facial recognition software, allowinghim to find any search-indexed photographs ofthat person posted anywhere. He essentially getsto bookmark people and access them wheneverand wherever the urge takes him. He accessed meand was surprised at what he found.Dad felt entitled to two identities: he could be agood guy at the dining table, and a powerful badassonline. The two identities never had to belinked to one another, as long as he kept in placean elaborate set of systems that kept the two livesseparate. The internet isn’t real to him. It’s just agame.And yet, it was Dad who told me about the goodold days, when your online identity would be moreauthentic than your real-life identity, when theinternet was the place you went to truly be yourself,to explore sides of yourself that you couldn’tpresent to the real world. He talked about it asthough it was a fleeting moment. “SJWs got obsessedwith identity, and made it into this wholewar,” he said to me.

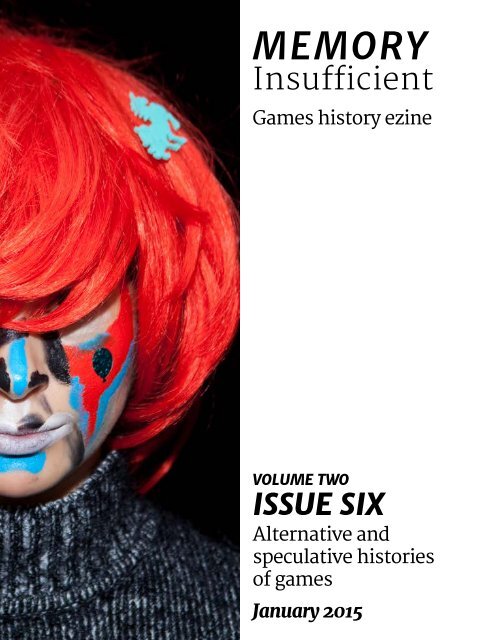

metrical hairdos, lighting tricks, draping headscarvesin just the right way so that one eye isconcealed. You find ways of showing your face toother humans while hiding it from the machine.I had friends who were constantly changing uptheir style so that their parents wouldn’t just findthem by the familiar shapes and colours they caston their face. But you learn how to read the commonelements in someone’s style that computersstill can’t read so well: the materials they prefer,the lines that their hand tends to produce.Trolls like my father turned onlinespace into a sick game. Well,I can play that game, too. And I’mbetter at it than he is.Dad hasn’t found any of my online profiles inyears, because he doesn’t understand who I am.He thinks he can find me by my name or my face.But I have lots of names and lots of faces. All ofthem are mine, readable only by those who knowwhat they’re looking for.ResourcesAdam Harvey (2014)Cv Dazzle: Camouflage from Face Detectionhttp://ahprojects.com/projects/cv-dazzle/About the header and cover image:Oakland poet Stephanie Young created the Anti-Surveillance FeministPoet Hair & Makeup Party project in reaction to an internal debate withinAmerican poetry after the December 2013 publication in the New York DailyNews of a puff piece profiling six young female New York poets. Photographedat the NYC Poetry Festival on Governors Island in late July whenthe New York poets were dressed to perform in the scorching heat, the articlewas widely excoriated within the poetry subculture. The poets cameto be blamed for having dared subject themselves to the male gaze in public.The backlash was vicious.The Anti-Surveillance Feminist Poet Hair & Makeup Party aims to scramblethe gaze. The Brooklyn segment was organized by poet Monica Mc-Clure, whose image headed the Daily News article & who therefore becamethe locus of her colleagues’ vitriol. Adopting the techniques of CV Dazzleby Adam Harvey, the Party thwarts the machine gaze of facial recognitionsoftware & disrupts the male gaze of the dominant culture. All via traditionalfemme grooming rituals & female bonding.Photograph by Emily Raw, used with kind permission.

Another Brickin the WallA history of indie gamesClaris Cyarron@cyarronClaris is an arcane laserbabe, trans-architect, wasteland wandererand narrative agitator. She works at Silverstring as an ineffabilityconsultant and feminist hex evoker.This piece has been reprinted from the Fall 2024anthology of The Indie Revue with permissionfrom its original author.IndieCadewas last week, and <strong>alt</strong>houghI’m a bit jetlagged,I’m still gleefully poring over the event detailsI downloaded. I’ve got many memories left togo through, but one of my favorite bits thus far hasbeen the appearance of Kelley Arman, lead writeron the Ancient Crests series, at the hyper-exclusiveFlawless Victory party.The whole 5-hour memory is great (and can bedownloaded from her Ancient Crests blog), butthe best part was when, a little over an hour in,

she climbed on stage and challenged the MC to adance-off on the pristine, first-gen Dance DanceRevolution pad that had been restored <strong>spec</strong>ificallyfor the event. I don’t want to spoil what happensnext, but suffice it say that ten minutes later, thebubble machines were turned on and the party reallygot started.Peering through the screen at the glamourousworld of game designers, watching the weeklyvideo recap for updates on the extraordinary livesof eccentric, exciting, elusive digital artists, viewingthe lives they have authored and the episodessectioned off and commodified for entertainment,one could be forgiven for not remembering that itwasn’t always like this.It’s hard for me to believe it too, and I’ve spent theentirety of my professional life—almost 9 yearsnow—exploring and commenting on the digitalart and games scene. But even just a decade ago,going to a game’s PAX booth meant meeting some(if not all) of the devs. Going to a GDC party wasas simple as showing up on time and paying thecover charge.Making friends with your heroeswas often as easy as introducingyourself.The goal wasn’t to create a space where artistscould continually reach further and push theboundaries of the artform, but to push against thevery boundary between creator and player. Thegoal was to get everyone creating games and tolet this movement spill outward to inculcate andinform every a<strong>spec</strong>t of a digitally connected, system-ladenworld.I suppose it’s easy to look back on this as simplyan extension of bygone, starry-eyed Silicon Valleyutopianism, but at the time, this radical inclusionismwas meant to be in direct oppositionto the tech-startup brand of Randian heroics that

led the world into four economic meltdowns beforefinally lying down to die. The idea was thatas long as the class of creative “out-of-the-box”thinkers continued to be the same kind of snotnosedbrats (who had no interest in anything beyondtheir ability to prove their own greatness),the vast potential of the digital arts would be wasted.The best thing for games (and tech at large) todo would be to open its doors to everyone. Or sothe story went.Now, as the 10-year anniversary of GamerGateapproaches, a few of my colleagues have begunpublicly bemoaning the loss of this techno-utopianvision with trite “in my day” nostalgia pieces.So, is this the point where I pile on? Do I thinkthere’s a dangerous or lamentable disconnect betweencreators and fans?I don’t agree that our community has lost its way,but I do think it’s important to look back over thelast decade. Perhaps if we were more historicallyaware, we’d understand the need for creators tohave the space to interact with each other withoutthe ever-present gaze of customers.Popular history has a peculiarway of compressing time, takingmovements and countermovementsand stacking them likepages in a book.We stop seeing the pages as being distinct and startfocusing on how the words flow between them.Each moment is a complex web of competing potentialities,but in hindsight, we read it as if thenarrative was somehow etched into the very fabricof time, immutable and preordained. Withoutediting, history doesn’t work well as a story preciselybecause history isn’t a story. Furthermore,loose-ends and counterflows aren’t evidence ofpoor storytelling, they’re evidence of a complexi-

ty only reality can provide.First of all, ten years ago gaming sites still hadcomment sections. Yeah. Remember those? Ofcourse you don’t, because they were horrible andyou’ve blocked out all memory of them, or you’retoo young to remember—lucky duck. Thanks toGamerGate and Hammerfest, the games communitywas one of the first to completely do awaywith comments.Comment sections are a rarity,and you can thank the constant,omnipresent brutality ofyour fellow humans for ruiningthe dream of an internet whereeveryone’s opinions matter andare heard.In the days before and during GamerGate andHammerfest, however, many denizens of the internetwere more interested in protecting a person’sright to speak (even if “to speak” meant“to harass”) than they were a person’s right tobe protected from abuse. It’s strange to look backon this and remember that at the time, it wasframed as a debate about free speech. Nevertheless,that’s exactly how it went down. Thousandsupon thousands of the entitled, petulant massescame shrieking out of the woodwork, crying “censorship!”in the face of (often temporary) bans forviolent threats and vile statements.Honestly, despite the justifiable fears toward governmentintervention, everyone still hoped thatthe government would eventually sort out the socialand technological ills that plagued the internet—atthe very least by making online harassmenta realistically punishable crime. I don’t thinkanyone expected that in the wake of the 2014-15race riots, and bogged down by the protests and

guerilla interference that would later coalesce intothe Social Liberation Front, local and federal lawenforcement agencies in the United States wouldsimple give up and make it clear that it was up toonline communities to police themselves.The fact is that the games communitywas forced into this positionboth by violently entitledfans and by the ineptitude of thesystems that are supposed to protectthem.When pop-game icon David Jaren received complaintsabout his absence on the PAX Prime 2022Mega Blast Mountain design panel, he respondedjovially. “I feel very blessed everyday to have myfans’ affection and support,” Jaren said.“Without them I wouldn’t have a job, but I alsohave that job to do, and attending conventions toanswer the same questions again and again isn’tpart of it. People will complain if I don’t go to aconvention, but they’ll also complain if the nextBlast Mountain gets pushed back, so I have to pickmy battles.”Notoriously weird art-games creator Paige Leavenworth(winner of the 2019 IGF Nuovo Award andthe IGF’s Seumas McNally Grand Prize in 2021 and2023), paints an even starker, and frankly, moreaccurate, picture of fans in the poem they postedon their website after they were targeted by Hammerfesthackers last year:We are not kings & queens, held high by our subjectsand honor-bound to preserve their lives andvouchsafe their happiness.We are not politicians, elected to our station bypopular vote and beholden to keep election promisesor else.We are wizards and priests, empowered by the

elief of the common folk and protected not bylove or devotion but by their fear. Fear of us—but protected only just. Our flocks and followersare indeed our greatest threat, for demons anddarknesses always wear a human face; evil worksthrough people; evil is born of people; it is impossibleto know what desires live behind unknowneyes.Leavenworth came under firefrom fans for being in a relationshipwith gender-abolitionistgames creator Quincey Floss anddigital art critic Jennie Jones.Jones was an IGF judge the year Leavenworth wontheir first Grand Prize, and some fans felt that thissignaled a potential conflict of interest, callinginto question the results of the 2021 awards <strong>alt</strong>ogether.Eventually, as things involving passionatefans always do, it escalated to death threats,extreme breaches of privacy, and drone-basedstalking. This resulted in the IGF finally decidingto abandon its long-held efforts to keep itselfopen to the public; last year’s awards ceremonywas an invite-only affair, with several popular butrelatively small-time creators being denied ticketsamid concerns that some of them had beenactive community members on notorious imageboard4chan in the past. Other creators were deniedinvite on the basis that they had connectionsto the Social Liberation Front.Jeremy Irons, the president of the IGF, was verycandid about the matter.“Look, as far as I’m concerned, the fans havebrought this on themselves. We are all reallyfucking tired of being bullied and harassed by‘fans.’ We’re done being terrorized by people whodon’t have the talent or energy to get off theirasses and create things for themselves, who justwant to tear down other people and their efforts.

We won’t let them suck our energy and time anymore. We don’t owe them anything. I’m not surewe ever did. As for which creators got invited lastyear, all I can say is that the IGF is not interestedin providing a platform for extreme views. We’vebuilt a rich, diverse, nurturing community here,and we’re not interested in radicals jeopardizingthat.”Of course, that wasn’t the first time Leavenworthhas faced the ire of their fans. You may remembertheir public refusal five years ago to allow Twitterto put their account on the Zero-Harassmentfeature track, along with all the other verified accounts.Leavenworth’s argument, which was disseminatedin their videogame manifesto, “NeverLook Away,” was that as long as Twitter was notfixing the problem for all users, it was unethicalfor the “elite” to accept <strong>spec</strong>ial treatment. A fewyears later, Leavenworth closed their account entirely,citing continued harassment.I think we all want to feel likewe’re an important part of thisamazing culture.One day, I hope that I’ll get on that Flawless Victoryguest list, but let’s be honest here, some of uscontribute more than others. These creators areour best and brightest, and they deserve the livesthey have built for themselves and the communitythey have built for each other. Like musicians andactors before them, these luminaries have beenlifted up by the hands of a million (or more) fansonly to realize that each hand wouldn’t let go, andso the dream turned into a nightmare.Some amateur designers claim that voices are stillbeing marginalized or excluded entirely in the developercommunity. Their argument is that the jobof including diverse voices was never truly doneand that many good folks were simply trappedoutside as the walls came up—a terrible fate indeed.

I couldn’t agree more, but that doesn’t in any waylend credence to the idea that the walls shouldcome down. Critics and commentators like myselfexist so that outsider creators can become known,and find their way inside. We need to acknowledgethe ways we are failing to do that. We don’t needto burn the castle down.The concept album The Wall (1979) by classic rockgroup Pink Floyd contains songs that tell a story.In it, we follow the life of a musician who is pushedfurther into isolation and disconnect by the ills ofthe world. Mentally, the protagonist builds “thewall” to keep everyone out and to keep himselfsafe. Pink Floyd was trying to comment on howmodern society alienates and isolates us all; eachmoment of the protagonist’s life is another brickin the wall, and in the finale of the album, the wallis torn down and he is once again free to reconnectwith the world.Of course, this was written beforethe creation of the internet,and the danger for artists todayis not isolation but invasion.The fact is, radical inclusivity was a great idea intheory and in history, but it fails to pass musterin practice today. Ten years ago, the narrative wasthat “anybody can make a game,” not unlike howthe idea driving communism was that “everyone’seffort is equally valuable.” We know how well thelatter worked out, and now it’s time to put the formeron the same shelf.Tower image rendered and shared by Monteirinhoon PlanetMinecraft.com

Kill the pastLiberation maiden anddestructive nostalgiaBenjamin Gabrieluninterpretative.blogspot.comBenjamin Gabriel writes about games, music and science fiction.Aside from blogging at Uninterpretative, he has also written forthe New Enquiry and writes book reviews for Strange Horizons.In the mid-2000s,a new Japanese game designer began makingwaves in America. His public-facing persona waslinked to one phrase: Punk’s Not Dead. His weirdgame became a flashpoint. Despite being for aNintendo console, it was as alienating, hyperviolent,and hypersexualized as anything from theItalian exploitation films of the 1970s. It had allthe technical abstraction and mythological sensibilitiesof early survival horror. And it was an onrailsshooter.Suda51’s Killer7 dreamt big. It framed its conflictsin no uncertain terms; the shooting gallery was

a game of chess at the end of time with gods asplayers, the targets (and, ultimately, the shooter)nothing less than global conspirators and avatarsof Death. But it still had time for charming characterslike a severed head and a grenadier luchador.The size of those dreams was seen, by the fandom,through a glass darkly; the developers’ ambitionwas not a feature or a narrative choice, but the architectureof the whole project. Killer7, a game obsessedwith conspiracy theories, became a thingto be decoded, a text in a Dan Brown novel. Fueledin part by the language barrier between Americanfans and the Japanese developer, auxiliary materialquickly became fetish objects for the dedicatedfandom. Of these, a supplement to Killer7 quicklygained prominence. The first half of its subtitlematched a phrase from machine-translated interviewswith the developer, and a new three wordphrase was born: Kill the Past.Nearly a decade on, piecing togetherthe information availablein English on the Kill the Pastslogan is still not easy.It seems to have been a sort of thematic trilogyfrom Suda51’s time as an employee of HumanEntertainment. The games he directed there hadsomething vaguely like a shared world, but weremostly linked by way of a motif; the playable character,at some point, would have to kill somethingor someone from their past, in order to be able tomove on or—according to some fan translationsof an interview about the last game in the trilogy—more<strong>spec</strong>ifically, to fight the future.Killer7 was looped into this trilogy, despite it consistingof Moonlight Syndrome, The Silver Case, andFlower, Sun, and Rain, because the supplement,Hand in Killer 7: Kill the Past, Jump Over the Age appearedon the radar of a new American fandom.And because—more than Suda51’s more popular

For the trilogy, seekontek.netFor the supplement, see thefan translation atdelta headtranslationthree-word catchphrase—it provided a productivemeans through which to read games markedby his brand.2013’s Killer is Dead was heralded as a return toform for the auteur, after a number of diversions;fans anxiously anticipated a return to the themesof Killer7 after years of Lollipop Chainsaws. It waswidely rumored that Suda51 had taken a backseaton directing “his” games sometime aroundthe release of No More Heroes; but fans still boughtthem, in hopes of a return to form.What this mentality ignored wasthat the phrase wasn’t an authorialsignature, but a productiveframing.A year prior to the release of Killer is Dead, Suda51’sGrasshopper Manufacture participated in a compilationgame, published by Level-5, for the Nintendo3DS handheld console. Titled Guild01, it wasintended as a showcase for Japanese auteur designers.Grasshopper Manufacture’s contributionwas Liberation Maiden, a game in which the Presidentof a future Japan (who happens to be a teenagegirl) pilots a mecha to fight off “The Dominion”and restore Japan to its natural beauty.For more on this, see:ClockworkWorldsThe mecha genre itself was just beginning a resurgencewhen Liberation Maiden came out. Theremake of Neon Genesis Evangelion had begun, andPacific Rim was well into development. The followingyear, the compilation’s sequel included agame called Attack of the Friday Monsters! whichmore directly addressed the conventions and historyof the mecha and kaiju genres, and the waysin which they are used to create futures for whichwe can all be nostalgic.This nostalgia is always haunted. The kaiju genre,and its most famous figure, Godzilla, are wellknown for being a response to the atomic bomb

and to widespread industrialization. They are politicalin a way that the depiction of mechas is not,even though the two are historically intertwined.The history, however, is largely avoided when thegenres are split; that Liberation Maiden is a mechagame is in some sense an attempt to avoid the politicsof history.A future for which we can all becomfortably nostalgic sits uneasilywith the imperative to killthe past.Liberation Maiden manages to create a future whichinverts the past. As the player shoots lasers at enemiesand buildings, causing them to burst intoflora, bits and pieces of narrative are unlocked.These unlocks happen when the player does unintuitivethings like “flying to the edge of the combatzone;” not challenges so much as suggestionsto play the game poorly. Six of these unlockablesare marked “History,” and provide worldbuildingcontext. “100 years in the future,” Japan is awaning ecological paradise under semi-subjugationby “The Dominion,” and is leading a worldwideeffort to resist the Dominion’s strangleholdon the world.The “sole ruler of the Dominion[,] known onlyas ‘the Chairman,’” never shows up in the gameproper. His “ambitions border on madness,” asthe leader of a nation whose “radical political philosophyis little more than a front for spreadingtheir own ideals and national interests, leadingthem to wage war against the entire world.” TheChairman, who is a clear analogue of Mao, alsohas weaponry described as “[l]acking any artisticaesthetics.”Over the course of the played through narrative,the Dominion is only ever given a single momentof visual identification; after the player has defeatedthe final boss, a large airship appears bear-

ing a flag with a striking resemblance to the flag ofthe People’s Republic of China (<strong>alt</strong>hough resemblanceto the Viet Cong flag or the People’s LiberationArmy’s Air Force flag are arguable as well):one large, and several smaller, gold five-pointedstars, the large on a red background. The flag ofthe Dominion is cut in half with blue on the bottom(where the smaller stars are), which bringsup the other resemblances.Liberation Maiden takes as its premise a fantasy futurein which the roles of the Second Sino-Japanesewar are reversed. The chairman is now theimperial aggressor.Suda51’s games have a tendency to engage internationalpolitics, but Kill the Past tends to be readas a purely personal theme. The fact that Killer7uses an America-Japan conflict as its motivatingincident is subsumed into the personal conflictsof its characters. Liberation Maiden doesn’t allowfor this, though: the only way to read it, in termsof Killing the Past, is politically.This political reading is fraught.It mirrors the ascendant rightwing tendency in Japan to revisethe nation’s imperialist aggressionsduring the second worldwar.In terms of the game itself, it pushes the ecologic<strong>alt</strong>hemes away from the benign Save theWhales feeling that blowing up buildings to maketrees provides and towards something more likeBlood & Soil. But the obvious counterpoint, thatthis premise is largely locked away behind a seriesof menus and so is not central to the game, ishard to argue ever since it received a sequel. LiberationMaiden SIN might not be available to English-speakinggamers, but the fact that it is a vi-

sual novel indicates that when given the choice,Suda51 opted to expand on the games story ratherthan its mechanics.That this first iteration came as a mecha shooter,with all its story components locked away, however,seems telling. The scoring system is, amongother things, a way to signify its status as in thelineage of arcade games. This lineage is largely abroken one; the decline of arcades, particularly inAmerica, positions any game which engages thisidiom as a throwback. Thus two central a<strong>spec</strong>ts ofthe game itself, its aesthetics and its incentives,are themselves of a piece with the past.The Kill the Past trilogy is sometimes read in termsof a theory of trauma; beyond the recurring tropeof a head in a brown paper bag, the <strong>spec</strong>ific impetusto kill someone (or something) from one’sown past in order to move forward in life gels witha psychoanalytic approach, whereby trauma mustbe objectified and overcome. Crucial to this dynamicis the hermeticism of the space, in whichthe analyst functions as an unimpeachable authorityfigure by way of manner and infallibilityof reading in order to provide the analysand witha space in which to progress beyond their trauma.Many of Suda51’s games can be read through thislens, though applying it to Liberation Maiden risksanthropomorphizing the actions of the state tojustify imperialism.Against simply ascribing toSuda51 an unreconstructed imperialistsympathy, then, an attemptto look forward.If Kill the Past is indeed a productive lens throughwhich to read his games, whether by authorial intentor accident of the global distribution of goods,then the rubric itself must be interrogated.The historical revisionism of Liberation Maiden is

For more on TakashiMurakami, see:Japan Societya way to apply the lens of the Kill the Past slogan,and a way to read it. If killing the past is a straightforwardtheory of trauma, then Liberation Maidenis little more than a rephrasing of contemporaryvisual artist Takashi Murakami’s thesis on kawaii;that Japanese culture is engaged in an endless attemptto overcome the trauma of the atom bomb.That, rather than the bomb, the game centers imperialistaggression is noteworthy, however. LiberationMaiden suggests that the past, in terms ofgame mechanics and aesthetics, can be productivelyengaged with as signs and systems. Thistakes the form of <strong>spec</strong>ulative future which lookssuspiciously like <strong>alt</strong>ernate history. To fight for thefuture, one must kill the past.ResourcesKontek.netKill the Past trilogyhttp://archive.kontek.net/killer7.3dactionplanet.gamespy.com/killthepast.htmDelta Head TranslationHand in Killer7http://www.deltaheadtranslation.com/adilegian/HAND_IN_KILLER7.txtAustin Walker‘A disputed history:Attack of the Friday Monsters and the Kaiju Genre’http://clockworkworlds.com/post/56557215335/adisputed-history-attack-of-the-friday-monstersandTakashi Murakami‘Little Boy:The arts of Japan’s exploding subculture’http://www.japansociety.org/little_boy_the_arts_of_japans_exploding_subcultureLiberation Maiden image copyright Level5

ApokalypsisRapture, death andmythmakingStephen Winson@StephenWinsonStephen Winson was co-editor of re/Action, and is now aco-founder of content curation platform newsbloQ.In the long tradition of apocalyptic writing fromthe ancient world, most stories are framed as thetranscription of dreams the writer had, whereinsomething, usually the future, is revealed tothem. The English word, apocalypse, derives fromthe ancient Greek apokalypsis, which means “revelation.”Opening presents is apokalypsis, as whatwas hidden is now revealed.Depending on which version ofthe Christian Bible you encounter,the final book may be titled“Apocalypse” or “Revelation” forindeed they are the same thing.

The adoption of Christianity by the Roman Empire,and its subsequent spread past the decayingstate, transformed an apocalypse into The Apocalypse;the <strong>spec</strong>ific events that were purportedlyrevealed to John of Patmos, and over time anyother fantastic scenario describing the end of thecurrent social and political order.Despite the major change in the meaning of apocalypse,apokalypsis has not disappeared. All of ourstories of <strong>spec</strong>ulative or <strong>alt</strong>ernative history, andmost of science fiction, are apocalyptic writingin that original sense. While we do not generallypresent them as a transcribed dream to each other,we do say that authors “dream up” the fictionalworlds they write about. With that framing, thedifferences between ancient apocalyptic texts andmodern fiction writing blur greatly. Indeed, wheneverwe write about the future, or consider whatmight have happened differently in the past, weare passing judgement on our own time in muchthe same way as the apocalyptic writers of old didon theirs.Sometimes this is explicit, such as the distinctnovel and film versions of Robert Heinlein’sStarship Troopers, and Joe Haldeman’s The ForeverWar. Often it is subtler, such as in Cormac McCarthy’sThe Road, or William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’sThe Difference Engine. The now of the authoris always there, constantly examined, regardlessof how far in the future the story takes place, orhow long past the <strong>spec</strong>ulative change it explores.As with John of Patmos, authorsof future and <strong>alt</strong>ernative historyjudge the time they are writingin.The Walking Dead games from Telltale are some ofthe best written examples of the zombie apocalypse.As with other stories in the genre, The WalkingDead is apocalyptic in both senses.

The societies we live in shown tobe brittle shells that are all thatprotects us from each other, andoften ourselves.Our selves are shown to be shells, built for a purpose,and we will become different selves whenneed demands, often without noticing. Trust isdangerous, e<strong>spec</strong>ially when survival is impossiblewithout it. The dirty jobs modern societiesmust do go undone, revealing the true nature ofthe costs of survival to those who had been livinglives of ignorant privilege. Living humans arethe monsters, and those who fail to recognize thatmeet brutal ends. Through the zombies, the naturalworld reasserts itself over humanity, turningformer humans into a thoughtless force of nature.That it is not a supernatural deity who is the drivingforce in the catastrophe is irrelevant. In TheWalking Dead the cold, uncaring universe stands injudgement, and the authors believe our society,not to mention most of us, will be found wanting.The <strong>alt</strong>ernate history of Bioshock also passes judgmenton the world when it was released. In its mostwidely recognized mode, it passes judgement onthe objectivist libertarianism of Ayn Rand’s AtlasShrugged by exploring how the author believes asociety run as such would end up. But there aremany direct allusions to the Christian Apocalypsethat riddle the text. The name of the city,Rapture, is obvious and explicit. The character ofAtlas/Fontaine has many attributes attributed tovarious versions of the Antichrist and the Dragonfrom Revelation and various subsequent interpretationsof the book. The player’s avatar, aproduct of the manipulations of Rapture’s Antichrist,bears a tattoo on his right hand, mirroringthe Mark of the Beast. At the end, he slays the“dragon” Fontaine, and is the saviour of the LittleSisters, the “chosen few” saved from the tribulationof the end times.

Taken together with its two sequels, Bioshock 2and Bioshock Infinite, the series expands from anapokalypsis of the doom of any would-be G<strong>alt</strong>’sGulch, to warning of the doom from any deviationfrom the modern, neo-liberal capitalist consensus.Bioshock 2 posits a collectivist opposition toAndrew Ryan’s objectivism taking over in the ruinsof Rapture, and judges those principles to befailures in practice. Bioshock Infinite extends thisjudgement both to modern neo-Confederate conservativereactionaries, and militant resistance bythe oppressed. Taken as a whole, the series becomessomething of an Apocalypse of ProfessorPangloss, the mentor of the titular main characterof Voltaire’s Candide. As the professor says at theend of the novel:“There is a concatenation of events in this best ofall possible worlds: for if you had not been kickedout of a magnificent castle for love of Miss Cunegonde:if you had not been put into the Inquisition:if you had not walked over America: if youhad not stabbed the Baron: if you had not lost allyour sheep from the fine country of El Dorado:you would not be here eating preserved citronsand pistachio-nuts.”This repeats all across <strong>spec</strong>ulative fiction. Star Trekposits the ultimate triumph of 1960s liberal Americanidealism. Fallout warns of the consequencesof our overweening sense of control over ourfate, and belief in progress, echoing Mary Shelley’sFrankenstein. Gears of War is a neo-conservativemorality tale for the War on Terror, exhortingits players that the only response to our implacableenemy is total war, total victory, or total destruction.Dead Space presents an atheist moralitytale of the horrors that could be unleashed by deludedtheists in the future. The “secular heaven”posited in the late Iain M. Banks Culture novels isa more modern, European take on the idealisticapocalypse of Star Trek.Employing apocalypse even extends to the storiesour political leaders generate about the kind of

government they and their opponents would implement.In the United States of America today,we are deluged by the duelling Apocalypses of theRepublican and Democratic parties. Apocalypse,and its apokalypsis, is fundamental to our modernunderstanding of the future and the past. It givesus the narrative of history. The whys and wherefores.Without that judgement of thepresent, the future isn’t the future,and the past isn’t history.Without that, it’s simply stuffthat happened, or might happen,or might have happened.Image: Four Horsemen of Apocalypse, by ViktorVasnetsov. Painted in 1887. Public domain imagevia Wikimedia Commons.

Going homeRepresentations of myresidencesJefferson Geigerjeffersongeiger.weebly.com @geigerjdJefferson Geiger is a graduate of Colorado State University’s Journalismand Technical Communication program. He is fascinatedby developers who push narrative and mechanical boundaries.“We’ve cleaned up the mess at DIA.”I blink at the screen. I’m playing Assassin’s Creedwhile sitting uncomfortably on a futon made for 21/2 people at my brother’s apartment in The People’sRepublic of Boulder. To my left is a cat whohates me and on my right is my brother’s roommate,passed out. I want to show him the screen,but I’m not sure if he’s either getting over a hangoveror a high. Maybe both. I was just lazily skimmingWarren Vidic’s emails, but now I read themmore carefully. Denver International Airport isonly forty minutes from here. I’ve been there morethan any other airport. What could have happenedat DIA? My DIA?

A few weeks later, my family and I drive to PeñaBoulevard, the throat of DIA, for a trip east to visitour past. Even though it’s night, the moonlightbounces off the snow and makes the city brighterthan hours before. We pass cluster of buildingsand I do a double-take. Was that—no, it couldn’tbe. There’s no way a random business park has thesame logo as Abstergo Industries. Has that watertower always been there? Maybe Ubisoft borrowedideas from the present, too.2012, the year Assassin’s Creed takes place, cameand went without any excitement. The blue mustangstatue with demonic orange eye outside theairport that killed its own creator didn’t evenclaim another life. It’s not that I was hoping foran incident to occur, it’s just that I was curious.I didn’t want the world to end from the MayanApocalypse, mainly because it would mean that Ispent my whole life in school, but surely I wasn’tthe only one wondering if something would happen.* * *I pop Left 4 Dead into the Xbox 360 after school whilemy friends all grab a controller off of the coffeetable. We start a new campaign for probably thesixth time. A few levels in, the excited profanitiesshouted at every encountered Witch or Tank settledown as the game is paused for bathroom break.I’m crouched behind an abandoned car staring atthe license plate for a couple minutes.Even though the screen is grayand blurred, I recognize thestripes. Blue. White. Yellow.Pennsylvania.Wait, that’s where we are? My old home?I’m the one person in the room who has beento The Keystone State, let alone live there for 15

years, and I only noticed the setting because I wasbored. With the generic names like Fairfield andNewburg I never realized it was Pennsylvania.The camera at the beginning of Blood Harvest pansover a sign that says “Allegheny National Forest,”but I must have been goofing off with my friends orskipped the cutscene. I’ve never been to the forestin person, so it’s not like I would have recognizedit, but the name “Allegheny” is so Pennsylvanianthat I should have known sooner.Instead, each new locale wasLorem Ipsum, USA to me: a quietplaceholder meant to not distractplayers from their objectiveof survival.After the zombie slaying session I become slightlydisappointed at this new information. Granted,Pennsylvania isn’t the most exciting state, but Ifeel as though Valve could have thrown in moreunique environments. Imagine cutting throughhordes of undead civil war soldiers on the fieldsof Gettysburg, running up the stairs of the PhiladelphiaMuseum of Art like Rocky to get to shelter,or knocking a corpse off of one of Pittsburgh’snumerous bridges. Six years later I get the leveldesign I’m looking for.* * *Everyone on Twitter can’t stop talking aboutThe Last of Us and I give in. Rather, my Playstation3-owning friend, who I also convinced to getJourney so I could experience it, gives in. I watchthe Hank Williams trailer from Gamescon overand over to sate my desire as he plays. When thecredits stop rolling he calls to me from down thehall. The eerie guitar of Gusatvo Santaolalla, thegame’s composer, pours out of the subwoofer aslight from the TV illuminates the otherwise pitch-

lack room. I plant my posterior and play.Ellie, Joel and I leave Boston and drive to Pittsburgh.I sing along to the Hank Williams trackthat I’ve now memorized and recognize the brightyellow Fort Duquesne Bridge in the horizon.I stare in awe and wander around the familiarsights. There’s the Mellon Building right next tothe US Steel Tower. A few moments later I passthe Highmark Building. Naughty Dog’s artists dida <strong>spec</strong>ulator job with aging real life environments20 years. It’s like I’m visiting my family in the futurethat probably won’t happen but I already believeit has. When I recognize settings in moviesit’s like looking at someone else’s photographs,but when I experience it in games it’s like I’m rewritingmy memory. Eventually Clickers ruin myscenic tour and it’s time to move on. The most livablecity isn’t so livable anymore. As I head west,my friend tells me that I’ll soon see another familiarsight.“Where’s this lab of theirs?” Joel asks. “All theway out in University of Eastern Colorado,” saysTommy. “Go Big Horns,” replies Joel.I sit in silence and go over the dialogue in my head.There’s no University of Eastern Colorado. ColoradoState University’s mascot is a ram, which isa male big horn sheep. My alma mater is only a40 minute drive to the Wyoming border and it’salso more eastern than University of Colorado,the state’s other major school and rival to CSU. Atattered green and gold banner, my university’scolors, with a Big Horn logo flaps in the wind asJoel approaches on horseback.I look over to my friend with wideeyes. I am on CSU’s campus playinga video game where I explorea fictional version of CSU.

I’ll admit that the brick architecture is more likeCU’s and the science building is probably theirmedical facility that churns out MDs, but CSU isknown for it’s world-class veterinary school. Thegame didn’t <strong>spec</strong>ify what kind of science lab. Inreality I understand it’s an amalgamation of thetwo for legal reasons, but you’ll have a difficulttime convincing me CSU doesn’t turn into a Fireflylab in the near future.I lean out of the room and picture zombies run downthe hall. What buildings on campus would be thebest hideout in 2033? With twelve stories Westfalland Durward are the tallest, but that might be abit too isolated. The third floor of Morgan Libraryis centrally located and has a good amount of realestate. One the other hand, the top of Yates givestwo more floors and the chemistry labs could proveto be useful. I should have signed up for HumansVersus Zombies this year.* * *I’m jealous of Californians, New Yorkers and Martians.They get to have all the fun in their own videogame worlds. The latest SSX has a map in TheRockies, but the 3,000 mile range stretches fromNew Mexico to Canada. Instead of going southand exploring Colorado’s 20-plus ski resorts, thegame focuses on three peaks in British Columbiaand Alberta. South Park: The Stick of Truth takesplace in a mining ghost town. Without locals-onlyreferences like in the Guitar Hero episode, themountains might as well be Skyrim.This summer I hiked around Mt.Massive, the location for Outlast,and didn’t spot a single abandonedbuilding, let alone an asylum.Given the state’s mass shootings history, de-

velopers should shy away from a modern, openworldgame in Colorado. However, The CentennialState’s past is rich with video game setting opportunities.I would love to play an Assassin’s Creed inthe late 1800’s with Tesla as the go-to gadget guycrafting tools out of his lab in Colorado Springs.If Red Dead Redemption ever has a sequel, it couldmove further north into Colorado and follow themining boom, train industry or Zebulon Pike’sexpedition. Throw a dart at the map and you’rebound to find something worthwhile.The coasts have been in the spotlight long enough.I want more people to experience what I did in TheLast of Us. Go big—I mean, rams.Image: Sketch of Mount Massive Buffalo StateHospital from Outlastby DeviantArt user Aiden2107

Comrades in codeA short history of thegaming commonsShaun Greenarcadianrhythms.com @shanucoreShaun lives by the sea in the south of England. He enjoys videogames, science fiction, punk, history and politics. This is hisfirst visit to this timeline.With the solemnity of Remembrance Day so close behindus, it is a fine time to look back on a near-centuryof near-global peace and recognise what this fertilebed has allowed to take root and bloom. In particular itis a time to acknowledge the importance of the GamingCommons - and to understand how this revolutionaryconcept was brought into being. As gamers,we often fail to afford sufficient attention to the toolsand support structures that have historically enableddevelopers to create the experiences we love.Some may consider it tasteless to draw a connectionbetween a monument to human barbarity and senselessnesslike the Great War and a cultural mediumthat, perhaps by dint of its youth, is often unfairly re-

garded as frivolous. The response to such accusationsis to note that just as the tapestry of history providesample inspiration for the conceptual and thematicgrounding of games—as in mature works that seekto explore the world around them—so too do the errorsof history suggest how events might have turnedout very differently.Consider Germany. As gamers we may know themchiefly for development collectives like Akiba andBlue Byte, alongside distribution co-operatives suchas Kalypsian. Such groups benefit from their nation’sstrong economy; German love of engineeringand precision may be a running joke, but the countryextols the European ideal with its economic stability,long-standing social democratic and socialist governance,and its many leading scientists, philosophersand technologists.Germany’s game developers, too, have often beenat the forefront of games as an explorative medium.Take, for example, the 1996 RPG Albion, which usedthe science fiction and fantasy genres to bring to vividlife a tale of colonialism, callous exploitation and,finally, war—all defeated by an alliance of minds thatspanned nations and worlds. It is difficult to imaginesuch a game emerging from an imperial Germany,so critical is it of the narratives that once defined thenation.Similarly, political experimentsin MUDs became popular in thecountry in the 1980s, allowingplayers to <strong>spec</strong>ulate upon andparticipate in a fictional Germanygoverned not by socialistcouncils but ruled by oligarchsand despots.With these and many other achievements borne in

mind, it is interesting to note that following the GreatWar and its 16 million dead—including 2 million Germanconscripts and volunteers—there were seriousproposals among the victorious nation-states to billthe cost of the conflict to Germany.Latter-day economists have analysed such proposals- actually annulled several years after the war ended,following changes in British and French political leadership- and argued that they might have destroyedthe viability of Germany as a nation, so preventingit from growing into the leading role it plays in Europetoday and simultaneously inviting the diseaseof nationalism back into its bruised national psyche.What might have happened had Germany’s peoplesuffered in such a way? We can only <strong>spec</strong>ulate, yet itis likely that the country would have followed a verydifferent trajectory, perhaps with ramifications forall Europe.Let us set aside <strong>spec</strong>ulation and focus instead on lessdisputable positions. Arguably the most importantfeature of the modern games development landscape,the Gaming Commons allows developers tosource assets from a vast library and draw upon thecoding expertise of their comrades.Entire modules can be taken fromthe Commons and repurposed,enabling sophisticated, provenmechanics and components to beimplemented without buildingthem entirely from the groundup.The origins of the Gaming Commons can be foundin the tape- and disk-sharing traditions that rosealongside early personal computing in early 1980sEurope, the USA and, later, the PSUSR. European andAmerican users would exchange disks containingthe primitive software of the time, often hand-cod-

ed by hobbyists, using their creativity to solve softwareproblems that the hardware manufacturers ofthe time had scarcely probed. Ironically, given thelate arrival of personal computing in the Post-SovietStates, it was a PSUSR factory on the outskirts of Leningradthat first began to ship its products with compendiumsof such crowdsourced software pre-loadedin 1985. This approach spread like wildfire aroundthe Old World, despite political resistance from theNew—which continued, as it continues today, tocling to its particular vision of intellectual property.Yet the physical nature and memory limitations ofdisks restricted the degree to which software couldbe exchanged, and the logistics of collating, organisingand okaying the use of software at manufacturingor distribution hubs compounded the challenges ofinterchange.This is where NORPLNET and ARPANET come in; theprecursors to today’s internet.While the history of the internetis generally well-known it’sworth acknowledging the ideologicalclashes that characterisedits ancestors.ARPANET came first in 1969: a triumph for the Americancapitalist model. Yet its intended use in militaryresearch programs proved enough of a politicalsticking point that European nations opted to producetheir own independent super-network.Although the modern global internet only came intobeing much later, NORPLNET was hugely valuable inhelping to refine the common practice of softwareexchange into something much greater. When theacademic and research network was opened to industryand the general public in 1988, computing enthusiastsseized upon it as a channel for mass discussionas well as data exchange. The exchange of software,

previously limited by physical media, geography orthe reach of distributive co-operatives, became intertwinedwith the free passage and exchange of databetween post-capitalist Eurasian nations, and theresultant boom in both innovation and refinementof software inspired still greater things—including,later, the Gaming Commons.Although digital gaming was still young, and largelyrecognised by mainstream culture as an Americanand Japanese eccentricity, its enthusiasts were disproportionatelyrepresented among these proto-internetpioneers. Many early NORPLNET users werethemselves software developers, and the 1980s hadbeen a fine era in which to exercise personal creativity—whichmeant that large numbers of computergames were produced.Yet as computers became increasingly powerful,and software concurrently grew more sophisticated,challenges began to emerge. Developers consistentlyfound themselves in the position of, if not reinventing,then recreating the wheel: coding parts of theirgames and crafting assets that, in truth, had beenmade hundreds of times before by other people. Howto solve such a problem?The answer came in the form ofa student project at UniversidadPolitécnica de Madrid, completedin 1990, which they dubbedthe Asset Repository.These Spanish comrades invited software and gamedevelopers around the world to contribute small programs,sub-routines, modules, even art and audioassets to this repository, and to take from it anythinguseful for their own development projects.“The origins of our Asset Repository lie in the varietyof our modes of thought, and of our... re<strong>spec</strong>tiveage and youth. I was a child during Franco’sattempted coup, and remember all too well how

Europe might have fallen into a new Dark Age offascism and corporatism. I turned to study latein life, but was determined to find ways to buildbridges, between nations and between citizens,not only politically but creatively. My many talentedcomrades on this project, with their youthand technological brilliance, and their beliefin this humanitarian vision, were able to makedream become reality.”- Bernadita Martin, Asset Repository ProjectLead, interviewed in 2005.The project proved such a resounding and popularsuccess that the primitive infrastructure of NOR-PLNET struggled under the strain of packet exchange,and the students at Madrid had to rapidly secure additionalservers to support the Repository. Thesewere happily directed to the university, at the behestof the country’s Syndicalist government, from one ofSpain’s leading computer manufacturers.It wasn’t until delicate international political treatieswere signed between 1992 and 1993, signalling -amongst other groundbreaking developments - theunion of ARPANET with NORPLNET into a single ‘internet’,that developers from the Old and New Worldswere able to exchange ideas and assets as freely as isthe case today. This digital union was celebrated bymany online initiatives, among them the renamingand expansion of the Asset Repository into the grander,more communitarian Gaming Commons, thanksto international co-operation between numerous academic,government and unaffiliated syndicalist datacentres.Yet despite today’s Gaming Commons only havingcome into being when Old and New united, it’s probablethat the original concept of the Asset Repositorywould never have been willed into being without thecomradeship between nations that characterises thepast four-score years of socialist and democratic Europe- all brought about thanks to the harsh lessonstaught by the experiences of the Great War and theassociated follies of capitalism and imperialism.

The spirit of the old Internationale,of collaboration betweenEuropean citizens and nations,and of a citizenry free to workand self-express for the good ofthemselves, one another and thecitizen body, is what ushered theCommons into being.What capitalist state could have permitted such widespreadfree exchange without the intrusion of thecommercial imperative, or provided support structuresby which citizens could pursue creative endeavoursthat have no clear, immediate ‘market value’?“It’s undeniable that the socialists and communistsof Old Europe have chanced across somethingbrilliant. It’s also undeniable that, onceAmerican capitalism and entrepreneurial spiritis brought to the table, this Asset Repository willsoon be a relic of the past.”- Unattributed quote, Microsoft Board meeting, 1991.Fortunately, <strong>alt</strong>hough the distribution of Americancommercial assets via the Gaming Commons wasand remains restricted, its new availability in 1990sUSA following years of proven success inspired manyAmerican citizens to make use of decades of European,Asian and African ingenuity. The projects thatthese American entrepreneurs released—typicallymarketed and sold domestically, and freely distributedoutside the United sphere of influence—shookthe American gaming industry from its Atari-dominatedcomplacency.The seismic impact of the GamingCommons continues to be feltthroughout the USA today.

US corporations such as Microsoft have attempted toset up their own competing commercial endeavours,though these have achieved limited takeup and success.Several smaller companies have experimentedin de-commercialising a<strong>spec</strong>ts of development,funding creative ‘farms’ to allow for greater freedomof experimentation—all in the hopes of later benefittingfrom the sales of new product, of course. Perhapsmost importantly, the number of games autonomouslydeveloped and released by citizens hasshown exponential growth year-by-year since theRepository was made available within the USA.Today the fruit of the Gaming Commons is enjoyedby millions of gamers and developers around theworld, and the games, stories and experiences thatpeople create continue to foster the empathy andunderstanding necessary to advance communitarianart and culture. There is beauty in seeing a Congoleseartist realise a vision that draws upon the richnessof her cultural heritage, and for it to have been madepossible because of the contributions of hundreds ofcomrades around the globe. There is also beauty inthe way that the Gaming Commons, by making trivi<strong>alt</strong>he communal overcoming of technical challenges,encourages creators to focus upon ideas, redoublingtheir efforts to make their games mean something.It is true that there are valid criticisms of the Commons.Today, with the majority of the world’s populationalready online, and with millions of creatorsaround the world all clamouring for attention, weare faced by a serious curatorial challenge that NOR-PLNET’s early Asset Repository users could neverhave foreseen. But they only had to imagine the solutionto their own challenge—how best to manage thelogistics of sharing—in order to bring it into being.So too do we. Unlike our comrades stranded in thehinterlands of capitalism, our future is only constrainedby the limits of our imaginations.Image: Shukhov tower, Moscow.Photo by Wikimedia Commons user LiteCC-BY-SA 3.0

After CyberSynChile’s department ofsimulation literatureAdam Flynnsplendidvagabond.blogspot.comAdam Flynn collects thoughts & notions orbitingthe topics of media theory, convergence culture,interactive shenanigans, anomalous pasts,and weird futures.Chilean mathematiciansworking on problems of uncertainty,adaptation, and“exceedingly complex systems”in a resource-limitedenvironment led to notableadvances in paralleldistributed processing andthe formulation of adaptiveresonance theory in themid-1980s. They continueto lead in research relatedto neural networks.From Spacewar onwards, American computing andcomputer games were born and molded in the shadowof the American military-industrial complex. Assuch, they carried with them an emphasis on topdowncontrol, zero-sum rivalry, and victory by conquest.Chilean cybernetics, by contrast, fostered anemphasis on decentralized autonomy, multiplicityof per<strong>spec</strong>tives, and collaborative optimization.This led them to perceive problems in different ways,and build different techno-social systems to addressthose problems. It fed into different developments inboth mathematics and the arts.The story begins, as one might expect, with politics.Salvador Allende was elected in 1970 on a platform of

enacting socialism within the nation’s existing democraticframework. This might have caused greatconsternation in Washington but for two events: theelection of Robert Kennedy in 1968 and the subsequentattempt on Kennedy’s life by former CIA operativeDavid Sánchez Morales.Kennedy had campaigned on aplatform of non-aggression, andthe latter event provoked the dismantlingof the CIA’s covert operationsbranch.Given the Bratislava Accord in August 1968 amongthe Warsaw Pact nations to tolerate Czechoslovakia’spath towards “socialism with a human face,” therewas an international opening for third-way experimentsthat had not previously existed.You probably know that it is possible by electronicsimulation to make a ten-year-ahead projectioninstantaneously, and then to change your policyand see what difference it makes. This is to takean experimental approach to policy making, doingthe experiments in the laboratory of the controlroom. So instead of experimenting on thepoor old nation, and discovering ten years laterthat your policy was wrong, you can test and discarda dozen wrong policies by lunchtime withouthurting anyone. After lunch maybe you willfind a good policy.-Stafford Beer (1973)Allende’s plan to deal with social and economic inequalityincluded changing the economic base of thenation by nationalizing critical industries, all thewhile preserving individual liberties. This was a tallorder, but at the same time its challenges and constraintscreated an opening for new per<strong>spec</strong>tives incomputing and problem-solving. It began in July1971, when British cybernetician and managementconsultant Stafford Beer was contacted by Fernan-

For more information on thetopic, consult the masterfulCybernetic Revolutionaries byEden Medinado Flores, an engineer with the Chilean ProductionDevelopment Corporation (CORFO). Flores was interestedin applying theories of scientific managementto the nationalized sector of the economy. Hewas likewise attracted to Beer’s philosophy of decentralizedautonomy. The result of their collaboration,Project Cybersyn, was a remarkable achievement ofreal-time many-to-many coordination and adaptivedecision-making.Following the trucking strike of 1972, economic conditionsimproved in Chile and political tensions graduallyeased. The Allende administration threw itsfull weight behind Cybersyn and a host of programsmeant to modernize and optimize the economy as awhole.By 1974, the practice of intensive simulation traininginspired by the Apollo program was well in place atthe top, allowing cabinet officials to respond to criseswith remarkable ease.Futuristic control centers werenot particularly scalable; to helptrain workers and managers atlower levels, they had to look toother tools.“The worker is not the problem. The problem isat the top! Management! […] Once the individualunderstands the system of profound knowledge,he will apply its principles in every kind of relationshipwith other people. He will have a basisfor judgment of his own decisions and for transformationof the organizations that he belongsto.”-W. Edwards Deming (1993)The nationalized sector continued to suffer from alack of qualified managers at ground level, and whilethey did commit to intensive training on the Japanesemodel of total quality management, CORFO did not

Bottom-up feedback sometimesled to revisions, whichoccasioned the original toolsfor version control, dependencytracking, and edit-ripples.The now-celebrated writersroom pioneered the systemof index cards, pinned to awall, connected by differentcolored strings with knotsto indicate paths and dependencies.have the computing power to let them all run computerizedsimulations. Beer was familiar with theTutorText series of instructional game-books in theUK, and suggested a <strong>spec</strong>ialized set of forking textsfor managers to “play” with little more than a paperbackbook. Over time, this series of “programmedlearning” was expanded, with each forked ending includingthe telex number to contact the relevant expertfor clarification and explanation.Prosaic and humble as they were,these texts were an essentialgroundwork for the creative explosionin game-books and story-simulationsthat came after.The production of the instructional texts requiredskilled writers to craft plausible responses for whatthe numbers spit out, and CORFO were fortunateenough to employ Roberto Bolano, a young writerrecently returned from Mexico. Bolano, already familiarwith non-linear writing from the works of JulioCortazar, Jorge Luis Borges, and the “tree-literature”of the French group Oulipo, took to the formwith gusto, inserting characteristic flourishes intowhat were otherwise dry passages of industrial optimizationand consensus-building. He made useof CORFO’s card-catalog-on-corkboard system tomanage forking narratives in his off-the-clock writingas well, starting with a short choose-your-ownstory where the reader took on the role not of a governmentalmanager, but of a fugitive poet waitingin a cafe for an absent lover. Esperar proved divisivewithin the Chilean literary community. Certain conservativecritics suggested it was not to be groupedwith literature at all, that Cervantes never needed totell his reader, “To tilt at the windmill, turn to page6.”Another writer included the telex extension of theCORFO writers’ room in his work, prompting a flurryof poetic submissions from factory workers. This

The archives of these projects,nicknamed “The Libraryof Babel,” came to behoused in the Museo de ArteContemporáneo in Santiagoand can be seen upon request.(perhaps inadvertently) led to later works assembledinto branching poems of staggeringly complexand mysterious structures, simply attributed to “TheChilean People.”“No one realized that the book and the labyrinthwere one and the same […] In all fiction, when aman is faced with <strong>alt</strong>ernatives he chooses one atthe expense of the others. In the almost unfathomableTs’ui Pen, he chooses—simultaneously—all of them. He thus creates various futures, varioustimes which start others that will in their turnbranch out and bifurcate in other times. That isthe cause of the contradictions in the novel.”-Jorge Luis Borges (1941)Influences also came from the field. Augusto Boalleft a deteriorating situation in Argentina to bring his“Theater of the Oppressed” to disadvantaged communitiesin Chile. By 1976, he was provided a smallrecurring grant to create theatrical scenarios for thetechnocrats at CORFO, putting them in the role ofindigenous peoples, factory workers, peasants, andother communities in danger of being less-heard.Gradually the process moved from a didactic processto one of dialogue.By the 1980s, rural schoolhouses had corkboards andtelex machines of their own for members of everycommunity to create their own branching stories,even as the simulation literature departments weremoving on to microfilm and semi-computerized Memexsystems.Writing for the newly-created Department of SimulationLiterature was demanding but transformative;the rate of turnover meant that an entire generationof writers, playwrights, poets, and the occasionalsystems theorist spent time being paid to tackle issuesof branching, complex, cross-dependent narrative.By the time personal computing came aboutin the 1980s, Chile was primed for an outpouring ofcomputationally-driven creativity, and finally prosperousenough to afford it.

DO-IT-YOURSELF VIDEO GAME HISTORY, vol. 2! Fill in theblanks, then keep it, trade it, or submit it to a scholarly journal.Printable versions available at nobadmemories.com.Video game scholars refer to 1988 as the “Yearof ______________________________” due to thepopularity of _______________________________.Whether in _________________________-stylearcades or on home consoles, games such as___________________________ delighted playersand retailers alike. Games released in 1988 arenotable for their _____________________________graphics, their ________________________-tingedmusic, and their impressive sales figures.The head of marketing for games publisher__________________________ remarked on thetrend of ____________________ in games, stating“________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________.” These hallmark gamescontinue to influence not only contemporarygaming but also _____________________________.written by RACHEL SIMONE WEIL and YOUNO CASH VALUE • NO REFUNDS • NO BAD MEMORIESDO-IT-YOURSELF VIDEO GAME HISTORY, vol. 2! Fill in theblanks, then keep it, trade it, or submit it to a scholarly journal.Printable versions available at nobadmemories.com.Video game scholars refer to 1988 as the “Yearof ______________________________” due to thepopularity of _______________________________.Whether in _________________________-stylearcades or on home consoles, games such as___________________________ delighted playersand retailers alike. Games released in 1988 arenotable for their _____________________________graphics, their ________________________-tingedmusic, and their impressive sales figures.The head of marketing for games publisher__________________________ remarked on thetrend of ____________________ in games, stating“________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________.” These hallmark gamescontinue to influence not only contemporarygaming but also _____________________________.written by RACHEL SIMONE WEIL and YOUNO CASH VALUE • NO REFUNDS • NO BAD MEMORIES