The Transferability of Skills - Economics - University of Western ...

The Transferability of Skills - Economics - University of Western ...

The Transferability of Skills - Economics - University of Western ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

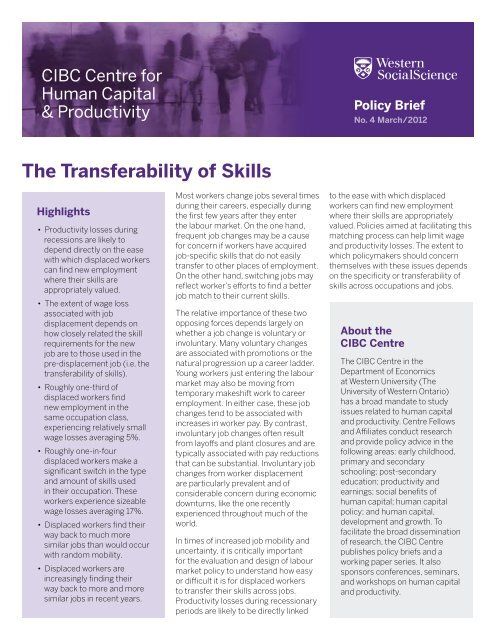

CIBC Centre forHuman Capital& ProductivityPolicy BriefNo. 4 March/2012<strong>The</strong> <strong>Transferability</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Skills</strong>Highlights• Productivity losses duringrecessions are likely todepend directly on the easewith which displaced workerscan find new employmentwhere their skills areappropriately valued.• <strong>The</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> wage lossassociated with jobdisplacement depends onhow closely related the skillrequirements for the newjob are to those used in thepre-displacement job (i.e. thetransferability <strong>of</strong> skills).• Roughly one-third <strong>of</strong>displaced workers findnew employment in thesame occupation class,experiencing relatively smallwage losses averaging 5%.• Roughly one-in-fourdisplaced workers make asignificant switch in the typeand amount <strong>of</strong> skills usedin their occupation. <strong>The</strong>seworkers experience sizeablewage losses averaging 17%.• Displaced workers find theirway back to much moresimilar jobs than would occurwith random mobility.• Displaced workers areincreasingly finding theirway back to more and moresimilar jobs in recent years.Most workers change jobs several timesduring their careers, especially duringthe first few years after they enterthe labour market. On the one hand,frequent job changes may be a causefor concern if workers have acquiredjob-specific skills that do not easilytransfer to other places <strong>of</strong> employment.On the other hand, switching jobs mayreflect worker’s efforts to find a betterjob match to their current skills.<strong>The</strong> relative importance <strong>of</strong> these twoopposing forces depends largely onwhether a job change is voluntary orinvoluntary. Many voluntary changesare associated with promotions or thenatural progression up a career ladder.Young workers just entering the labourmarket may also be moving fromtemporary makeshift work to careeremployment. In either case, these jobchanges tend to be associated withincreases in worker pay. By contrast,involuntary job changes <strong>of</strong>ten resultfrom lay<strong>of</strong>fs and plant closures and aretypically associated with pay reductionsthat can be substantial. Involuntary jobchanges from worker displacementare particularly prevalent and <strong>of</strong>considerable concern during economicdownturns, like the one recentlyexperienced throughout much <strong>of</strong> theworld.In times <strong>of</strong> increased job mobility anduncertainty, it is critically importantfor the evaluation and design <strong>of</strong> labourmarket policy to understand how easyor difficult it is for displaced workersto transfer their skills across jobs.Productivity losses during recessionaryperiods are likely to be directly linkedto the ease with which displacedworkers can find new employmentwhere their skills are appropriatelyvalued. Policies aimed at facilitating thismatching process can help limit wageand productivity losses. <strong>The</strong> extent towhich policymakers should concernthemselves with these issues dependson the specificity or transferability <strong>of</strong>skills across occupations and jobs.About theCIBC Centre<strong>The</strong> CIBC Centre in theDepartment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Economics</strong>at <strong>Western</strong> <strong>University</strong> (<strong>The</strong><strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Western</strong> Ontario)has a broad mandate to studyissues related to human capitaland productivity. Centre Fellowsand Affiliates conduct researchand provide policy advice in thefollowing areas: early childhood,primary and secondaryschooling; post-secondaryeducation; productivity andearnings; social benefits <strong>of</strong>human capital; human capitalpolicy; and human capital,development and growth. T<strong>of</strong>acilitate the broad dissemination<strong>of</strong> research, the CIBC Centrepublishes policy briefs and aworking paper series. It alsosponsors conferences, seminars,and workshops on human capitaland productivity.

CIBC Centre for Human Capital & ProductivityIn two recent CIBC Centre WorkingPapers (2008-3 and 2011-5), ChrisRobinson empirically examines thetransferability <strong>of</strong> skills by measuringhow job skill requirements change forworkers when they switch employers,voluntarily or involuntarily. He furtherexamines the extent to which changesin skill utilization across occupationsimpacts the wages <strong>of</strong> workers thatswitch jobs.Workers may change jobs voluntarilyfor personal reasons or to move aheadpr<strong>of</strong>essionally. Following a move up acareer ladder, the new job may be quitedifferent from the old one, involving apromotion to a different occupationin which all skills are used at a higherlevel. Not surprisingly, these moves aretypically accompanied by wage gains.By contrast, involuntary moves tend toresult in skill utilization downgrades andwage declines. Interestingly, voluntaryand involuntary moves tend to result inchanges in skill utilization <strong>of</strong> a similardegree — only the direction <strong>of</strong> thechange differs.JobDisplacementand Skill<strong>Transferability</strong>In “Human Capital Specificity:Evidence from the Dictionary <strong>of</strong>Occupational Titles and DisplacedWorker Surveys 1984 2000”, Robinson(with Maxim Poletaev) explores theskill and wage losses associated withinvoluntary worker displacementfrom plant closures. Some workersexperience sizeable wages losses, whileothers see little or no decline in theirwages. As one might expect, the extent<strong>of</strong> wage loss depends on how closelyrelated the skill requirements for thepost-displacement job are to thoseused in the pre-displacement job(i.e. the transferability <strong>of</strong> skills).Based on data from the 1984-2010United States Displaced WorkerSurveys, roughly one-third <strong>of</strong> displacedworkers find new employment inthe same occupation class. <strong>The</strong>seworkers experience relativelysmall wage losses averaging 5%.Other workers switch occupationsaltogether. Roughly one-in-fourdisplaced workers make a significantswitch in the type and amount <strong>of</strong>skills used in their occupation.<strong>The</strong>se workers experience sizeablewage losses averaging 17%. Finally,among displaced workers who switchoccupation but manage to avoid asignificant change in the type andamount <strong>of</strong> skills utilized, wage lossesaverage a more modest 9%. See Box1 for a detailed description <strong>of</strong> how theskills used in different occupations aremeasured, along with correspondingmeasures <strong>of</strong> ‘occupational distance’.Box 1 - Measuring ‘Occupational Distance’Measures <strong>of</strong> how close any two occupations are in terms <strong>of</strong> the skills theyuse – referred to as ‘occupational distance’ – are calculated using datafrom a detailed examination <strong>of</strong> over 12,000 jobs in the U.S., known as theDictionary <strong>of</strong> Occupational Titles (DOT). Job analysts scored each job interms <strong>of</strong> a large number <strong>of</strong> characteristics, such as the required level <strong>of</strong>finger dexterity, the level <strong>of</strong> mathematical or writing ability, the requiredamount <strong>of</strong> strength, etc. Using a technique known as factor analysis,Robinson and Poletaev condense this information to associate with eachoccupation a level <strong>of</strong> four basic skills, called a skill portfolio, each derivedfrom the analysts’ measures <strong>of</strong> all job characteristics. <strong>The</strong>se four basicskills roughly correspond to ‘general intelligence related’, ‘fine motorskills related’, ‘strength and gross motor skills related’, and ‘visual skillsrelated’. Any two occupations are considered similar if they have similarskill portfolios. Occupations may differ for two reasons. First, they mayuse a different mix <strong>of</strong> skills. For example an accountant uses a high level<strong>of</strong> mathematics but a low level <strong>of</strong> strength compared with a constructionworker. Second, occupations may use similar types <strong>of</strong> skills, but they mayuse them at very different levels.Most <strong>of</strong> the analysis discussed in this brief focuses on changes in skills andwages associated with movements across the nearly 500 occupationsdistinguished in the U.S. three digit occupation coding system. However,not all jobs within an occupation code have the same skill portfolio. Basedon data from the DOT, the average distance <strong>of</strong> random within-occupationmoves is about half the average for random moves across occupations.Thus, skills are not fully transferable across jobs even for displacedworkers who remain in the same occupation class. Unfortunately, it is notpossible to link changes in skill requirements across jobs within the sameoccupation to associated changes in wages, since standard data sets thatcontain wage measures, such as the March Current Population Surveysand Displaced Worker Surveys, do not measure jobs at a finer level thanthe three digit occupational classification.

CIBC Centre for Human Capital & Productivity0.95Figure 1: 'Occupational Distance' Between New and Old Occupations forDisplaced Male Workers in US0.93'Occupational Distance' (Relative to a Random Occupation Change)0.910.890.870.850.830.810.790.770.751984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010YearIn “Occupational Mobility, OccupationDistance and Specific Human Capital”,Robinson shows that displacedworkers find their way back to muchmore similar jobs than would occurwith random mobility. For example, ifdisplaced workers randomly selectedamong all occupations, fewer thantwo percent would end up finding reemploymentin their same occupation– much less than the one-third thatactually remain in the same occupationclass. Furthermore, among thoseworkers that switch occupations, thechange in skill requirements is typicallyless than one would expect if they wererandomly selecting among all possibleoccupations.More importantly, displaced workersare increasingly finding their wayback to more and more similar jobs inrecent years. Conditional on changingoccupations, displaced workers in 1985found new jobs that were, on average,only a little better matched to their skillsthan if they had randomly accepteda new job in a different occupation.More precisely, the ‘occupationaldistance’ (see Box 1) between their oldand new jobs was roughly 90% <strong>of</strong> the‘occupational distance’ between anytwo randomly selected occupations.Over the past 25 years, Figure 1 showsthat this skill distance has fallen bynearly 10 percentage points. Thissuggests that the productivity andincome losses from involuntary workermobility may be declining significantly,raising important questions about whatlabour market or policy influencesare improving the occupational reassignment<strong>of</strong> displaced workers.Many studies have shown that providingjob search assistance can have ahigh pay <strong>of</strong>f for displaced workers. Bycontrast, numerous policy experimentsand decades <strong>of</strong> research have shownvery little return to providing trainingopportunities to most displacedworkers (Jones 2012). Together, thesefindings suggest that public policiesaimed at helping displaced experiencedworkers find new jobs that utilize theskills they have spent their careersbuilding may be more cost-effectivethan trying to re-train them for entirelynew occupations.

CIBC Centre for Human Capital & ProductivityReferencesChris Robinson, “OccupationalMobility, Occupation Distance andSpecific Human Capital”, CIBC Centrefor Human Capital and Productivity,Working Paper 2011-5, 2011.Maxim Poletaev and Chris Robinson,“Human Capital Specificity: Evidencefrom the Dictionary <strong>of</strong> OccupationalTitles and Displaced WorkerSurveys 1984-2000”, CIBC Centrefor Human Capital and Productivity,Working Paper 2008-3, 2008.Stephen R.G. Jones, “<strong>The</strong> Effectiveness<strong>of</strong> Training for Displaced Workers withLong Prior Job Tenure”, CanadianLabour Market and <strong>Skills</strong> ResearchNetwork Working Paper No. 92, 2012.About the authorsChristopher Robinson is a Pr<strong>of</strong>essor<strong>of</strong> <strong>Economics</strong>, and an Affiliate <strong>of</strong> theCIBC Centre at <strong>Western</strong> <strong>University</strong>.Maxim Poletaev is a recent PhD.graduate from <strong>Western</strong> <strong>University</strong>.Additional copiesFor additional copies or for a pdfversion <strong>of</strong> this paper please visit ourwebsite at:economics.uwo.ca/centres/cibcCIBC Centre for Human Capital & ProductivityDepartment <strong>of</strong> <strong>Economics</strong>Social Science Centre<strong>Western</strong> <strong>University</strong>London, Ontario CANADA N6A 5C2