Download - Delhi Heritage City

Download - Delhi Heritage City

Download - Delhi Heritage City

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

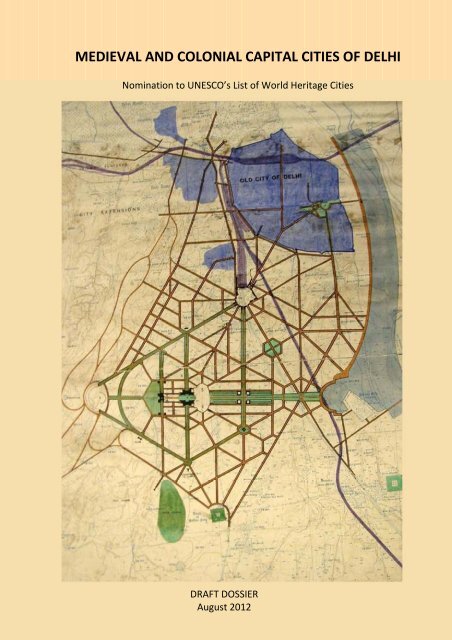

MEDIEVAL AND COLONIAL CAPITAL CITIES OF DELHINomination to UNESCO’s List of World <strong>Heritage</strong> CitiesDraft DossierAugust 2012Nodal Agency: <strong>Delhi</strong> Tourism and Transportation Development Corporation (DTTDC)Nomination prepared by INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter

ContentsExecutive Summary1. Identification of the Property1.a Country (and State Party if different)1.b State, Province or Region1.c Name of Property1.d Geographical coordinates to the nearest second1.e Maps and plans, showing the boundaries of the property and buffer zone1.f Area of nominated property (ha.) and proposed buffer zone (ha.)2. Description2.a Description of Property2.b History and Development3. Justification for Inscription3.a Criteria under which inscription is proposed3.b Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value3.c Comparative analysis (including state of conservation of similar properties)3.d Integrity and/or Authenticity4. State of Conservation and factors affecting the Property4.a Present state of conservation4.b Factors affecting the property(i) Development Pressures (e.g., encroachment, adaptation)(ii) Environmental pressures (pollution, climate change, desertification)(iii) Natural disasters and risk preparedness (earthquakes, floods, fires, etc.)(iv) Visitor/ tourism pressures(v) Number of inhabitants within the property and the buffer zone5. Protection and Management of the Property5.a Ownership5.b Protective designation5.c Means of implementing protective measures.

5.d Existing plans related to municipality and region in which the proposed property is located(e.g., regional or local plan, conservation plan, tourism development plan)5.e Property management plan or other management system5.f Sources and levels of finance5.g Sources of expertise and training in conservation and management techniques5.h Visitor facilities and statistics5.i Policies and programmes related to the presentation and promotion of the property5.j Staffing levels (professional, technical, maintenance)6. Monitoring6.a Key indicators for measuring state of conservation6.b Administrative arrangements monitoring property6.c Results of previous reporting exercises7. Documentation7.a Photographs, slides, image inventory and authorization table and other audiovisualmaterials7.b Texts relating to protective designation, copies of property management plans ordocumented management systems and extracts of other plans relevant to the property7.c Form and date of most recent records or inventory of property .7.d Address where inventory, records and archives are held7.e Bibliography8. Contact Information of responsible authorities8.a Preparer8.b Official Local Institution/Agency8.c Other Local Institutions8.d Official Web address9. Signature on behalf of the State Party

1 a Country India1 b State Province or Region <strong>Delhi</strong>1 c Name of Property Medieval and Colonial Capital Cities of <strong>Delhi</strong>1 d Geographical Coordinatesto the nearest second.1 e Maps and plans, showing theboundaries of the nominatedproperty and buffer zone(i) Topographical Map - Drg No:- Scale : 1: 50,000(ii) Location Map - Drg No:- Scale : 1: 50,000No buffer zone has been designated for Shahjahanabad as thelayout is inward looking, not requiring a setting beyond the citywalls for it to retain its integrity.In Colonial New <strong>Delhi</strong>,o the central avenue is of great significance and the east –west view corridor from Rashtrapathi Bhavan to PuranaQila needs to be preserved. A buffer has therefore beendemarcated along this axis.o Another important view corridor is from India Gatetowards Safdarjung’s Tomb. A buffer has also beenprovided in this direction.o Towards the west of New <strong>Delhi</strong>, the diplomatic areaChanakyapuri, built after Independence, has also beenincluded as a buffer area to preserve the view corridorleading to the Vice regal building. The principal street ofChanakyapuri, Shanti Path, was oriented to provide a directview of the dome of the Viceregal building.1 f Area of the nominated property and proposed buffer zoneShahjahanabad:New <strong>Delhi</strong>:6.76 sq.km19.64 sq.kmArea of Buffer Zone:1) 7.20 sq.km2) 0.43 sq.km3) 0.20 sq.km

2 DESCRIPTION

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTION2 a Description of PropertyThe area proposed for nomination comprises of Shahjahanabad, and New <strong>Delhi</strong>. The former was founded as thecapital of the Mughal Empire, by the Emperor Shahjahan in the mid 17th century ( between 1639‐ 1648). New<strong>Delhi</strong> was the British colonial capital, designed by a Town Planning Committee headed by Edwin Lutyens and builtbetween 1912‐31, adjacent to the Mughal city. Both are outstanding examples of town planning of their times;and continue to function as iconic precincts of the capital of republican India and are symbolic of the city’sextraordinary historic antecedents.Shahjahanabad, although a medieval city, is today very much a living vibrant city. The size and shape of the city,its main streets and major landmarks, which were the product of Imperial planning, are still largely intact and stilldefine the character of the city. The city’s original urban morphology, along with the key buildings is still surviving,making it a supreme example of Mughal city planning. The city has a perimeter of 8 kilometers and encloses anarea of about 590 ha.Shahjahanabad’s townscape is characterised by a few key features. Within the imperial city, the focus is the Qilai‐Mubarak(or Red Fort as it is called today)—the imperial palace complex. It is the largest and grandest structurein the city, laid out in the north east corner of the city fronting the River Yamuna. Red Fort, with its elegantpalaces, symbolises a legacy of political power, which is why the Prime Minister’s address to the nation onIndependence Day is from the Red Fort.What was once the principal bazaar street along the east‐west axis, Chandni Chowk which starts at the LahoreGate of Red Fort and continues west till the chowk of Fatehpuri Masjid, is still the heart of the city. Chandnichowk is a fascinating melange of buildings from different eras of the city’s history, but with a throbbing pulse inthe present. It is a lively commercial hub, with many places of worship—mosques, Hindu and Jain temples,gurudwaras, churches. The northern section of Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, which runs through Darya Ganj (it wasoriginally called Faiz Bazaar), is the north‐south axis of the city, starting from the <strong>Delhi</strong> Gate of the city till the<strong>Delhi</strong> Gate of the fort. This street then continues northwards as Netaji Subhash Marg till Kashmiri Gate. Thesewere the two principal axes of the city and continue to be major commercial spines.Besides the fort, the other important building in the city today is the Friday congregational mosque, the JamaMasjid, which was placed on a natural rise in the ground. Four roads radiate from Jama Masjid in four directions,towards Hauz Qazi Chowk, Daryagang, Red Fort and Chandni Chowk.A network of streets link different parts of the city like the fort, public squares, places of worship, city gates andthe residential areas. The hierarchy in the size and character of the streets: viz the bazaar streets, kuchas, galishas provided the city with a circulation network. Within this framework of streets, settlements have developed,giving the city its unique form. There is a distinct pattern that is still legible, the thanas(wards)and mohallas( areasor residential pockets). The original residential stock of intricately carved facades and doorways of havelis stillexist as do the green courtyards of traditionally laid out homes.Red Fort (Qila‐i‐Mubarak)The Red Fort was originally built along the banks of River Yamuna and the city was planned keeping the fort as thefocal point of development. Located in the centre of the eastern face of the city, the fort wall has 21 bastions, amoat and four gates‐Lahori gate, Akbarabadi gate, Salimgarh gate and Khizr gate. The Fort is an irregularoctagon in plan measuring 3100 ft X 1650 ft with a perimeter of 2.41 km, enclosing an area of 125 acres. The31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 2

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONheight of the fort wall varies from 60 ft to 75 ft and it is 45 ft to 30 ft in width. In keeping with the character of therest of the city, the high walls of the citadel are cased with dressed sandstone, though interspersed with posternsand bastions, suggesting privacy and grandeur rather than defence.The main entrance to the citadel is through the Lahore Gate, so named because it faces the city of Lahore and theother gate of the fort, <strong>Delhi</strong> Gate, faces what used to be the old city of <strong>Delhi</strong>, and further south, Agra. LahoreGate consists of three separate sections. The bridge before entering the fort was built for Emperor Akbar II (r.1806‐37). Shahjahan’s successor Aurangzeb added the 10.5m high barbican —the fortification enclosing theLahore Gate and making its approach less straightforward. Beyond the barbican, and at right angles to it, standsthe Lahore Gate itself, a three‐storeyed structure of red sandstone flanked on either side by half‐octagonalturrets topped by open pavilions. This central portion of the gateway is a style Shahjahan used commonly in hisgateways: a row of small chhatris, each topped by a white marble dome, and with a minaret at either end of therow.Some key heritage structures in the fort:o Chatta Chowk Just beyond Lahori gate is a covered market, chatta chowk , a long arcade with shops oneither side.o Naqar Khana Beyond chatta chowk lies the Naqar Khana (also called the Naubat Khana) Originally thedrum house of the Red Fort, this today houses the site office of the Archaeological Survey of India andwas the main entrance to the Diwan‐e‐Aam (the Hall of Public Audience) beyond.o Diwan‐e‐aam A striking, beautifully symmetrical palace with open sides and front, made of redsandstone. It stands on a high plinth, with a deep chhaja (overhang) projecting below the roof, which hassmall chhatris or pavilions at the north‐western and south‐western ends. Elegant cusped arches on flutedcolumns divide the Diwan‐e‐Aam into 27 square bays. The highlight of the hall is the magnificent whitemarble throne that stands in the centre of the eastern wall, exquisitely decorated, with a curvingBangalda or whaleback roof, and carvings of flowers, particularly daffodils, all along the lower front of thestructure. The wall behind the throne is especially beautiful, inlaid in very fine and extensive pietra durawork depicting trees, flowers and birds.The main palaces that used to be occupied by the royal family are situated along what was then the river front:o Mumtaz Mahal A relatively plain white building, the southernmost of the buildings fronting the river. Ithas been converted into an Archaeological museum displaying artefacts from the Mughal era. The hall isbuilt in white marble with six sections divided by five archways.o Rang Mahal Located behind the Diwan‐e‐aam, this palace building made of white marble and shellplaster, is also known as the Imtiyaz Mahal (the `palace of distinction’). The structure has anunderground chamber called tehkhana. The entrance of the structure is through five broad archways withcusped arches. The centre of the hall has a lotus shaped fountain. At the extreme end of the building aresmall chambers inlaid with fine mirror‐work, fine strips of silvery mirror forming arabesques andgeometrical patterns on the ceiling and upper walls.o Khaas Mahal Next to the Rang Mahal are four contiguous structures—the Khwabgah, Baithak, TasbihKhana and Musamman Burj—that together form the Khaas Mahal. The Tasbih Khana consists of threerooms facing the Diwan‐e‐Khaas (the Hall of Private Audience); behind the Tasbih Khana are the threerooms that form the Khwabgah, or the sleeping chambers. Adjacent to the Khwabgah is the Baithak orTosha Khana, and at the east end of the Khaas Mahal is the Musamman Burj, a semi‐octagonal tower withcarved marble jalis (screens) and a jharokha (oriel window) in the centre. The Khaas Mahal, and especiallythe Khwabgah, is extremely ornamental, with finely carved white marble throughout, particularly, the31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 3

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONexquisite jaali work and the depiction of the scales of justice on the northern side of the Khwabgah. Thenorthern side also has beautifully worked metal doors, carved all over in a pattern of flowers, withunusual doorknobs in the shape of elephants with mahawats sitting atop them.o Diwan‐e‐Khaas Beyond the Khaas Mahal, and separated from it by a courtyard paved with white marble,is what is by far the most ornate of the Red Fort’s many palaces: the Diwan‐e‐Khaas. Unlike the Diwan‐e‐Aam, this hall is made completely of white marble embellished with carving, gilt and fine pietra dura inlayon the lower part of the columns. The hall is rectangular in shape with several columns and arches onwhich rests the flat roof. The inscription over the interior of the central arches of the northern andsouthern walls: `Gar firdaus bar ru‐e‐zameen ast, hameen ast o hameen ast o hameen ast’ (‘If there be aparadise on earth, it is this, it is this’) is a couplet by the famous 13 th ‐14 th century poet, Amir Khusro. Theroof has chajjas on all sides and is topped with small chattris.o sawan and bhadon pavilions The sawan and bhadon pavilions along with the water channel known asthe Neher e Bihist is another striking feature of the complex. Both these pavilions are beautifully carvedwith small arched niches on the wall. The neher continues through the Diwan e Khas, Khas Mahal to theRang Mahal.o Burjs Another important structure of the Fort is the Shah Burj which lies along the wall to the far end ofthe complex, north of Hira Mahal. Like the Mussamman Burj and the Asad Burj, this was also one of theimportant towers overlooking the Yamuna River. The structure has an octagonal plan and formed thecentral hydraulic system feeding into the Neher e Bihisht which is no longer is in use. Adjoining the ShahBurj is a marble pavilion known as Burj‐i‐Shamli. Shah Burj consists of two distinct sections: the mainsection is a five‐arched pavilion of white marble supported on fluted columns and with low whalebackroofs. Attached to this, on the river‐facing side, is the actual burj, the tower.o Zafar Mahal Midway between the sawan and bhadon pavilion in the centre of the broad waterchannel that ran through the Hayat Baksh Bagh. Here lies the Zafar Mahal within a four sided tank built inred sandstone.o Hammam The hammam lies next to the Diwan e Khaas and Khaas Mahal. The structure has threechambers with intersecting corridors and a central basin for hot and cold baths. The interiors are made ofwhite marble having peitra dura inlays on the wall and floral carvings on the floor.o Hira Mahal Beyond the hammam is Hira Mahal, a small sparingly decorated four‐sided pavilion builtin white marble, with three cusped arches on each of its four sides, topped with a simple parapet above achhajja. The side facing the riverfront has arches partly closed off with slabs of marble and jalis along thelower half.o Moti Masjid also known as “pearl mosque” is near the hammam. It is built with white marble and hasthree small domes. It was used as a private chapel by the Mughal emperors and the ladies of theirhousehold. On the eastern side (the side facing the hamaam), is a wall pierced by an ornate door withleaves of copper decorated in a lovely floral design. On the northern side, its façade is inlaid with delicatefloral patterns in black marble and coloured semi‐precious stones, along with extensive carving.Chandni ChowkThis is an important street and a business sector of the city even today. The eastern end of Chandni Chowk startsat the Lahore Gate of the Red Fort complex and ends at the Fatehpuri Masjid located at the western end of thecity. Today this busy commercial street is very much the pulsing, throbbing centre of the city. The two kilometrelong street is flanked by shops on either side selling everything from household goods like utensils, furnishings,electronics, and consumer goods to clothes and books. The street is intercepted by iconic structures, mostlyreligious and institutional buildings, built from the period of the inception of Shahjahanabad till the early 20 th C.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 4

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONThe very inclusive nature of the city is reflected in the fact that shrines of different religions coexist on the samestreet, imparting a strong cultural harmony. The street and its squares are also the setting for periodic religiousand other celebrations and processions, some going back to the days when the city was founded.The first stretch of this street is from the intersection of Netaji Subhash Marg and Chandni Chowk to what isknown as Phawwara Chowk. The eastern half of this section consists of development that has taken place afterthe demolitions of the mid‐19 th century. Thus Esplande Road, which runs southward off the main street, was aBritish creation. On the other hand certain older structures such as the Digambar Jain Lal Mandir, and thejewellers market called Dariba Kalan (a major street linking Chandni Chowk to Jama Masjid), have survived to thepresent day.Some key heritage structures in the area:o Digambar Jain Lal Mandir lies at the eastern end of Chandni Chowk. Though added to down thecenturies, the temple dates to the time of Shahjahan. The Jain temple is surrounded by several smallshops. Built in red sandstone with a shikhara and a finial on top, the temple includes several shrines ofwhich the main shrine is that of Lord Mahavira. The temple has intricately decorated interiors with floralmotifs, images of dancers, musicians and geometrical patterns. The charitable bird hospital lies withinthe complex of the Lal Mandir where injured and ill birds are brought in for treatmento Gauri Shankar Temple was founded in the 18 th C AD and rebuilt several times. The white marble andplaster temple is dedicated to Lord Shiva and his consort Parvati. It is surrounded by shops selling flowers,incense and clothes.o Gurudwara Sis Ganj with its beige sandstone building and golden domes and finials lies further west fromthe Digambar Jain Mandir. This gurudwara rectangular in plan, in sandstone and white marble has seenwas established in 1783 AD and marks the site where the ninth guru Teg Bahadur was beheaded by theMughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1675. The Gurudwara rectangular in plan, in sandstone and white marblehas seen considerable expansion over the last century.o Sunheri Masjid, also along this street, is located just beside the Gurudwara Sis Ganj. The mosque standson a high platform with shops on the lower floor. It is approached by a series of narrow steps leading uptothe court. The domes of the mosque are covered in gilded copper and form another landmark alongChandni Chowk.o The State Bank of India building, which originally housed the Imperial Bank, stands 70 feet tall with aPalladian façade spanning 120 feet close to the eastern end of Chandni Chowk. It is the most imposing ofthe several early 20th century bank buildings in Chandni Chowk. It is a three storeyed building with highceilings, colonial style gateposts and a verandah supported by Corinthian pillars on the first floor level.This building is constructed on the land which consisted of Begum Samru’s Palace and gardens in the early19 th century. Though no remains of the gardens can be seen, the original palace of Begum Samru, calledBhagirath Palace, still exists and is located north of the State Bank of India buildingo The Central Baptist Church, next to the State Bank of India building is one of the earliest churches of <strong>Delhi</strong>,having been built in 1858. It has a heavy circular colonnaded porch and the roof of the church is made instone supported on iron beams.o Phawwara Chowk, which is the first square on the main street, was in Mughal times known as KotwaliChowk. It is today called Bhai Mati Das Chowk, though it is popularly known after the fountain(phawwara) in its middle, built to commemorate the visit of the Governor General Lord Northbrook(1872‐76)31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 5

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONThe central segment of Chandni Chowk stretches between the two squares – Phawwara chowk and the Town Hallchowk. Leading immediately off it to the south are important commercial enclaves or katras – e.g Katra Ashrafi,Katra Shahanshah. The katras are most frequently self‐contained units communicating with the street outsidethrough gates that can be closed. Kinari Bazar, the major market street specializing in lace, tinsel, sequins andother decorative clothing accessories, stretches roughly parallel to Chandni Chowk, opening up in Dariba Kalan.The neighbourhoods of Dharampura and Maliwara lie slightly further south, where many old havelis still survive.The former contains the cul de sac known as Naughara, with its nine havelis with painted doorways, and its a Jaintemple.The central segment of Chandni Chowk ends in a square which was originally laid out by Jahanara Begum, thedaughter of Shahjahan in 1650 AD. Originally called Chandni Chowk (moonlight square), it has given its name tothe entire street, and is itself better known today after its major landmark, Town Hall. To the south of the squareruns a major road, Nai Sarak, which is a major commercial street.The Town Hall was built in 1860‐5, on the site previously occupied by the Begum ki Serai and Bagh, both ofwhich were destroyed after the Revolt of 1857. With its impressive Corinthian columns, mouldings and fineparapet, this elegant pale yellow and white building spreads out around a courtyard and is bounded byporches with arched entrances on all four sides of the building. To the north of Town Hall is a garden whichoccupies the space of Jahanara’s garden. What was originally Company Bagh but has today been renamedAzad Park is a fenced garden with Royal palm trees. The main landmark of the circular park is a large blackstatue of Mahatma Gandhi, which stands in the centre of the park, facing the Town Hall.The western part of Chandni Chowk stretches from the Town Hall chowk to the Fatehpuri Masjid. Off this sectionof Chandni Chowk are some important commercial streets such as Katra Neel (famous for its many small templesor Shivalayas) to the north and Katra Nawab to the south. Also to the south lies the historic residentialneighbourhood of Ballimaran, famous for being the home of hakims or practitioners of traditional Unanimedicine, and the home (now a memorial) of the famous 19 th century poet Ghalib. At the western extreme of thisstreet is Fatehpuri Masjid, surrounded by shops. North of Fatehpuri Masjid is Bazar Khari Baoli, Asia’s largestspecialist spice Market. South of Khari baoli too is an important commercial area with trading enclaves such asKatra Badiyan.Some key heritage structures in the area:o The road also has the Haveli of Lala Chunnamal. The two floor structure has an intricately designed castirongrilled balcony on the first floor and a verandah on the ground floor. Several windows also adorn thefaçade of the building. The interiors of the haveli include a huge courtyard. The rooms have intricate artwork and detailing.ooBuilt in 1650, by the wife of Shahjahan, Fatehpuri begam, Fatehpuri Masjid has a simple and symmetricrectangular plan with fluted dome and kalash finial on top. The two minarets flank the mosque on eitherside. The main prayer hall has seven arches with a pillared hall of multi‐lobed arches and columns. It isapproached through a courtyard once entered from the gate. The mosque resembles the Jama Masjid toa great extent.Along the southern side of this segment of the road are several architecturally significant bank buildingsdating from the early decades of the 20 th century.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 6

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONDaryaganjThe street leading southwards from the <strong>Delhi</strong> gate of the Red Fort to the <strong>Delhi</strong> gate of the city is a thoroughfareand bazaar street equal in importance to Chandni Chowk. This was originally known as Faiz Bazaar, and along itseastern side lies the locality known as Daryaganj (literally, ‘mart by the river’). In contrast to the rest ofShahjahanabad, this area has a grid pattern street layout that took shape in the early decades of the twentiethcentury. Many commercial and residential buildings of that era, and some from earlier, still survive, giving theprecint a distinctive character.Some key heritage structures in the area:o The Zinat‐ul‐masajid is a mosque that dates from 1707, and was built by Zinaunnissa begam, thedaughter of Emperor Aurangzeb. It is one of the major mosques of the city, and similar in style to theJama Masjid, with its red sandstone and white marble ornamentation, twin minarets and three stripeddomes.o The Shroff Eye Hospital, dating from 1926 is a well preserved colonial building.o <strong>Delhi</strong> Gate marks the southern limit of the street, and is one of the four surviving gates of the city.o Segments of the <strong>City</strong> Wall are in a well‐preserved state along the southern edge of Daryaganj, and displayparticular features such as a British‐era Martello Tower.Jama MasjidLocated south‐west of the Red fort, the main congregational mosque of the city stands 10m above the ground ona natural outcrop known as Bhojla Pahari and is by far the most impressive structure in Shahjahanabad. It hasthree gates facing the east, north and south accessed by a series of steps. The façade of the mosque is amagnificent eleven‐arched front, with the central arch the largest. The arches are of red sandstone supported onfour‐sided columns of white marble; each arch is inlaid with delicate tendrils of white marble, and has highlightsand medallions in black marble inlaid on either side of the arch. Above the arches tower three domes of whitemarble, with fine strips of black marble inlaid in between. At either end of the façade rise two tapering minaretsin red sandstone and white marble. The sehan—the main courtyard of the mosque is a vast area, paved with redsandstone with a large marble tank in the centre meant for ablutions. On three sides, enclosing the sehan, arearched cloisters pierced by ornate stone gates. The north‐western corner of the sehan houses a small lockedroom with relics of the Prophet. The floor is white marble, inlaid with a simple pattern that resembles a mosalla (aprayer carpet). Inside, the decoration is restrained, consisting almost entirely of inlay work—white marblearabesques are inlaid all across the ceiling and arches of red sandstone. The mihrab (the closed arch that indicatesthe direction of prayer) inside the main archway of the mosque is very intricately carved, all in white marble; so isthe fine minbar—the pulpit—in front of the façade.Besides being an important place of worship, Jama Masjid is a major landmark in physical, cultural, culinary andcommercial terms. It is at the junction of important streets – Matya Mahal to the south, Dariba Kalan to the north,and Chawri Bazar to the west. The northern and western sides of the square around the mosque are lined withshops, hotels, and visitor amenities such as parking.The steps on the eastern side, which provide a visual connection with the southern gate of the Red Fort, havesince Shahjahan’s time been a place for the sale of wares by hawkers selling goods ranging from articles of areligious nature to exotic country medicines. They take advantage of the stream of visitors to the mosque andthe shrines of Sarmad Shahid and Hare Bhare Shah, located halfway up the steps.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 7

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONAlong the southern edge of the square is a market known as Urdu Bazar. This has a number of bookshopsspecializing in Urdu language books. It also has a number of stalls and restaurants serving traditional street foodand more, which the Jama Masjid area has long been known for. The dense neighbourhood known as MatyaMahal lies to the south of this.North ShahjahanabadThe northern areas of the Shahjananbad, north of Chandni Chowk and the Red Fort, have transformed since thefounding of the city. Always much less populous than the area south of Chandni Chowk, a large part of the groundwas covered by gardens, and by the vast mansions belonging to the Mughal royalty and nobility. The latterparticularly occupied the eastern part of this area, the riverfront. When the British first moved into <strong>Delhi</strong> theyestablished this area as the centre of administrative power, building several new colonial structures, bothreligious and institutional or simply adding to or co‐opting older buildings.The area was also the scene of many a battles during the uprising of 1857, also known as the First War of IndianIndependence. Momentous changes came to the area after the revolt, when the British obliterated large parts ofJahanara’s gardens and established a railway line, aligned along the east‐west axis. ( Section 2b History anddevelopment describes these changes in greater detail) The eastern part, the Kashmiri Gate Area, still retains itswide roads, open spaces and grand buildings, now mostly put to institutional use. There are also handsomeresidential buildings along Nicholson Road.Some key heritage structures in the area:o Kashmiri Gate This was one of the fourteen original gates built by Shahjahan around his newly foundedcity facing towards Kashmir and hence named Kashmiri Gate. This two‐bay gate is built out of brickmasonry and covered with plaster.o Dara Shikoh's Library Dara Shikoh, Shahjahan’s favourite and heir apparent to the Mughal throneexhibited a keen interest in architecture just like his father. He is known to have constructed his mansionin a span of four years (1639 – 43) at the cost of 4,00,000 rupees at a site north of Red Fort near KashmiriGate. Although the current building is mostly the work of the British, many of its original Mughalelements can still be seen. It has a classical façade with 7.5 m ionic columns supporting a partly collapsedarchitrave. The original 3m high plinth and steps can be seen from the rear. Inside too, some elements ofthe original Mughal structure are still visible like a double row of blind arches leading to a central portal.The interior is simple concrete flooring and a concrete roof supported on wooden beams placed on irongirders. It is now part of the premises of the Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University and is used as amuseum under the department of Archaeology, Government of <strong>Delhi</strong>.o Fakhr‐ul‐masajid (Pride of the mosques) or Lal Masjid, was built in 1728‐29 by Kaniz‐i‐Fatima tocommemorate her deceased husband, Shujaat Khan, a high ranking noble under Aurangzeb. The redsandstone mosque, faced with white marble, is clearly modelled on major mosques in <strong>Delhi</strong> built duringthe reign of Shahjahan and Aurangzeb. In fact, it is one of the few stone mosques built in <strong>Delhi</strong> during theeighteenth and the nineteenth centuries. The mosque is raised on a 2.5m platform with shops at the base.Once you climb up to the raised courtyard, there are arcades on both the north and the south.o Northern Railway Building The building currently being used as an office by the Northern Railways,was formerly the mansion of Ali Mardan Khan, a senior general of Shahjahan who was associated withmany of his constructions, especially canals and gardens. As was common in the early days of the empire,the British did not feel the need to demolish the original building completely and therefore, the building31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 8

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONoooooostill has the remains of the Mughal taikhana, or underground chamber, underneath it. The main room ofthe building is domed and on all four sides of it there are semi‐octagonal turrets. On the north and southsides there are circular projecting rooms. On the rear is another circular room with a flat roof which hasprojecting rooms on either side, giving the building a bow shape.Kashmiri Gate Bazaar The building was commissioned by Lala Sultan Singh, a leading banker of his time,in the 1890s. This was a time of relative political stability that led to the rise of the merchant class in <strong>Delhi</strong>and many commercial and institutional buildings were constructed around this time. The building, about50m long, is made of brick and has shops on the ground floor and iron pillars supporting projecting upperfloor balconies that are constructed out of a combination of wood and wrought iron. The roof is gabledover alternate bays and has tin roof on top. In the topmost floors of the last few bays, are a fewresidences constructed in the same style.Bengali Club This building located right beside the Kashmiri Gate was constructed as a cultural centre forthe Bengali community. This is a double‐storeyed structure with shops on the ground floor. The first floorhas a balcony supported on iron columns and has gabled roofing and an elaborate wrought‐ ironbalustrade.St. James Church St. James' Church, also known as Skinner's Church, built in 1836 by Colonel JamesSkinner, is one of the oldest churches in <strong>Delhi</strong>. The building itself was designed by Major Robert Smith, aBritish army engineer. The basic design of the Renaissance style church is of a Greek cruciform plan, withthree porticoed porches, elaborate stained glass windows and a central octagonal dome similar to a domeof Florence Cathedral in Florence. Many late Mughal elements can also be noticed in the building. Thecopper ball and cross on the top, which are said to be replica of a church in Venice, were damagedduring the1857 revolt, and were later replaced. Colonel Skinner is buried here and north of the church liesthe Skinner family plot where many of his descendants are buried. The church is also known for two otherimportant graves; one belonging to William Fraser, and the other of Sir Thomas Metcalfe, who lived in<strong>Delhi</strong> for forty years from 1813 to 1853, during which time he served as Agent to Governor General ofIndia.Magazine Gateway This gateway is all that remains of the British gunpowder and armaments magazinethat was destroyed during the siege of 1857. The structure is now located in a small park in the middle ofa traffic island on the main Lothian Road near Kashmiri Gate. A low‐ vaulted building is attached to agateway that has openings facing both sides of the road. On the outer face there are semi‐octagonalprojections on both sides which lead to a vaulted gateway with two small rooms on either side. There isalso a small canon placed over the gateway. Adjacent to the ruins of the gateway is a smallcommemorative column in granite that was erected in 1901‐2 to honour the postal personnel who died in1857. The height of the column is about 5m and it sits on a square base and tapers towards the top.St. Mary’s Church The church was built in 1865 on the land cleared after the revolt of 1857. The buildingis built in the Italian Romanesque style, not very different from the St. Stephen’s Church near theFatehpuri Mosque and is finished in stucco plaster. The church is laid out on a cruciform plan and has asimple pitched roof made out of country tiles. The arms of the building are semi‐circular in plan. At theentrance on the west there are semi‐circular arched gateways and a bell tower. At the first‐floor levelthere is a blind arcade. The building features some interesting stained glass work on the inside.Post Office This white painted building was built in 1885 in classical European style. The building has fivebays with semi‐circular arches and tapering pilasters in between these doorways. The upper floor wasdesigned as a deep verandah but this has now been screened.The western sector of this part of Shahjahanabad, is the Lahori Gate area. Lahori Gate was one of the originalgates of the walled city of <strong>Delhi</strong>, built in 1651 along with the rest of the city. It was the city’s exit to the Grand31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 9

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONTrunk road, connecting <strong>Delhi</strong> to the north of the country, much before Shahjahanabad was founded. In the mid‐19 th century the railway added a new dimension to this connectivity, and led to the development of relatedinsfrastructure, such as hotels and dharamshalas, in this part of the city. Though the gate was destroyed after theRevolt of 1857 along with the sections of the wall leading from it, there are a number of interesting buildings inthe area, some that even pre‐date the founding of Shahjahanabad.o Old <strong>Delhi</strong> Railway Station Just off the busy S. P. Mukherjee Marg is one of the oldest railway stations builtby the British in India, constructed in 1867. A fairly substantial edifice, it has many gothic featuresincluding tower‐ like bastions that form the corners of the projecting porches, giving the building itsimposing façade. There are deep verandahs on both floors. The building is painted a brick red colour, withwhite paint used to highlight certain architectural features.o Sarhindi Masjid At the end of this street, just outside where the Lahori Gate must have been, stands theSarhindi Masjid, a small mosque built by Sarhindi Begum, one of Shahjahan’s wives. This is a three baymosque is topped by three bulbous domes that dominate the skyline as you approach it from outside.Although most of the mosque structure is original, the courtyard has been built over and is surrounded bymany new buildings.o St Stephen’s Church is an Anglican church built in 1867.South ShahjahanabadThis was prominent even centuries before the founding of Shahjahanabad; as is evident in the several olderstructures in this area. Even the street pattern follows a logic that is distinct from the two main north‐south andeast‐west streets of the city. Here, the major street connecting Turkman Gate and Lahori Gate, and the severalparallel streets, follow a diagonal orientation that originally formed a part of the Grand Trunk Road, the majortrade and communication artery connecting Punjab in the north to the Gangetic Plain in the South.The oldest structures of the city – the dargah of Shah Turkman, Kalan Masjid, the grave of Razia Sultan, HauzwaliMasjid and others lie on either side of the main diagonal street which is called Sitaram Bazar in its southernsection, and Lal Kuan Bazar in its northern part. At Hauz Qazi chowk it intersects with another important street,one that connects Jama Masjid to Ajmeri Gate. At its Jama Masjid end this street is known as Chawri bazar and ishome to the wholesale paper trade. After Hauz Qazi Chowk it is known simply as Ajmeri Gate bazar. These twostreets are important commercial spines, as is the Hauz Qazi chowk, which also has a metro station. Anotherstreet system that follows the diagonal pattern from north‐west to south‐east, consists of the streets known asNai Sarak, Ballimaran, and Churiwalan.There are several narrower lanes leading off from the broad streets, and usually designated ‘gali’ or ‘kucha’.These too often have shops as well as entrances to havelis. Bazar Sitaram and Kucha Pati Ram have particularlywell‐preserved havelis. There is a further network of very narrow lanes leading from these, which are usuallyresidential, though some have small workshops. Compared to the area north of Chandni Chowk, southShahjahanabad was spared the wholesale destruction of the city’s fabric after the revolt of 1857. It thereforeretains much of its original layout, with the exception of Nai Sarak, which was laid in the mid‐19 th century.Another important commercial street lies along the southern perimeter of the city. A continuous row of <strong>Delhi</strong>’searly Art Deco buildings on Aruna Asaf Ali Marg stand where the city wall was once located. Most of them arecommercial in nature.Some key heritage structures in the area:31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 10

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONo Hauzwali Masjid, located in Gali Batashan, is of rare architectural quality and is amongst the few survivingSuri‐period buildings in Shahjahanabad. The mosque built in AD 1540‐50, measures 21m north to southand about 8m east to west. The prayer chamber, which is one‐bay deep is divided into three large domedchambers. The arches are low and massive, with the springing point very close to the floor level.o Masjid Mubarak Begum is located a short walk from the Ajmeri Gate Metro Station (at Hauz Qazi)towards Kharibaoli. The raised mosque with shops below, is accessed by a narrow flight of stairs from thestreet. It was commissioned in 1822 by Mubarak Begum, who was the wife of Sir David Ochterlony, firstBritish Resident of <strong>Delhi</strong>, and was attached to her now‐demolished house. The tiny red sandstone mosqueis well‐proportioned and the scale of the mosque too, is quite intimate.o Two havelis, that of Kucha Pati Ram and Ram Kutiya lie opposite each other. These havelis are largelybuilt of Lakhori bricks with grand entrances of cusped arches and jharokhas and fluted sandstone columns.The haveli of Kucha pati Ram has two floors with intricately carved sandstone façade. Projected jharokhasare placed on sandstone columns. Carved columns, railings and ornamental doorways add to thecharacter of the building. The Haveli Ram Kutiya also has two floors with decorative archways and flutedsandstone columns and floral carvings. The ground floor has two bay windows with extensive carving onthe facade. Both the havelis are built around a central courtyard.o Kalan Masjid, built in 1387, was in existence for nearly 300 years before the city of Shahjahanabad wasestablished. This was possibly the principal mosque of Firoz Shah’s city of Firozabad and is one of theseven great mosques built by Firoz Shah Tuglaq’s Prime Minister, Khan Jahan Junan Shah during the midto late fourteenth century. The lower storey of the five‐bay mosque is now used for residential andcommercial purposes. The corner towers and outer walls of the mosque are all sloped inwards and thereare no minarets. The inside of the mosque consists of a courtyard surrounded on three sides by a singlearcade, borne by plain squared columns. The western prayer hall has three rows of columns. The ablutiontank is in the centre of the courtyard.o Holy Trinity Church Located a stone’s throw away from the Turkman Gate, the Byzantine style church wasbuilt in 1905, using local quartzite stone. It has a cross plan with a domed chapel and half‐domedprojecting bays. Buttresses have been used at the north end and all domes are topped with lanterns. Thefoundation stone was laid on 1 February 1904, in memory of Alexander Charles Maitland by his widowMary R. Maitland.o Ghaziuddin Madrasa, Mosque and Tomb Ghaziuddin, a powerful minister and nobleman in theimperial courts of Emperor Aurangzeb built a complex that included a madrasa, a large mosque, and hisgrave enclosure, sometime during AD 1692, as an institution of higher learning. The complex is locatedright outside the Ajmeri Gate and accessed through the gateway of what is now the Anglo Arabic School.The mosque is a finely proportioned building made out of red sandstone with white marble relief work.It’s a seven bay mosque where the central archway dominates the façade. The structure is topped withthree white bulbous domes. The tomb of Ghaziuddin, built during his lifetime, is made in ornate whitemarble surrounded by elaborately carved screens depicting typical floral patterns of Mughal architecture.There are other smaller graves surrounding the main tomb.o Ajmeri Gate is one of the original gates that was built around Shahjahanabad when it was founded in themid seventeenth century. Most of the gates and part of the city wall were demolished after the revolt of1857. As its name suggests, the gate faces the direction of Ajmer towards the south ‐west of the walledcity. It is a single arched gateway with semi octagonal turrets on the outside. It’s a relatively plainstructure built out of quartzite and red sandstone. Some typical decorative features include carvedmarble rosettes, carved sandstone panels, and on the inside, some fine painted plaster work.o Turkman Gate, one of the four surviving gates of Shahjahanabad, built in AD 1658 is located on Asaf AliRoad, very close to the Ramlila ground. It lies to the south‐western end of the walled city and is named31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 11

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONHavelis: The courtyard house is the basic residential unit in Shahjahanabad, and hundreds of historic havelis areto be found throughout the city. The basic structure comprises rooms constructed around one or morecourtyards. Most of the havelis were originally two storeys but have frequently more floors have been added.The haveli communicates with the street through a doorway set in an ornamental façade – most often of carvedsandstone. A balcony at the first floor level is also frequently provided. Terrace roofs provide additional usableopen space as well as communication with neighbouring havelis.Shops and workshops are located mostly located along the kuchas and galis but in some crowded areas like thataround Jama Masjid and Chawri bazaars, shops are located even within the mohallas. Typically shops occupy theground floor, while the first floor is reserved for residences. Shops and residences are not connected internally.The entrance to the residence at the ground level leads directly to a staircase while the shop has a completelyindependent access.Small factories and workshops are not located along the bazaar streets but within the mohallas and residentialblocks.eg: Gali Chitra Darwaza, behind Sita Ram Bazaar. There is a tendency for concentration of shops orworkshops of the same type.eg: opposite Jama Masjid‐shops selling second hand automobile parts; easternchawri Bazaar‐ paper and paper products( retail and wholesale shops along the bazaar and factories makingnotebooks, cards and business paper are behind the bazaar); western chawri Bazaar‐hardware, building material,etc.The streets connecting the city gates with major urban facilities are the major streets that are also the bazaarstreets. Viz: Chawri Bazaar, Sita Ram Bazaar, Matia Mahal Bazaar and Bazaar Chitli Qabar. While the primarystreets like Chandni Chowk and Darya Ganj have the important markets, the secondary streets which radiatetowards the Jama Masjid and the mohallas, are the smaller bazaar streets trading in items like meat, fish, luxurygoods etc.Each market specializes in a different trade.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 13

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONNEW DELHIThe British Empire was at its zenith at the beginning of the 20 th century, when they built their colonial capital cityto the south‐west of the Mughal city of Shahjahanabad.The city of New <strong>Delhi</strong> extends to the walls of Shahjahanabad in the north, is bounded on the east by the RiverYamuna, the remains of Ferozshah Kotla and Purana Qila, and to the west by the ridge. The city deliberately formsseveral links with the older cities, most importantly, the central vista that is conceived as a landscaped stretchforming continuity between the ridge and the river. One of the avenues, the Parliament Street is linked to thesouthern side/edge of Shahjahanabad and visually to Jama Masjid, while the central vista, beginning at theRashtrapati Bhavan ends at the north gate of Purana Qila (the inner citadel of the city of Dinpanah that flourishedas the 6 th city of <strong>Delhi</strong>).Colonial New <strong>Delhi</strong>, designed on a radial plan by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker is spread over 2,800 hectaresand makes up for about 1.8 per cent of the area of <strong>Delhi</strong> today. The site had a width of about 4.5 miles,narrowing as it approached Old <strong>Delhi</strong> to 2.5 miles. The city reflects the fusion of the two dominant themes ofearly twentieth century city planning – the <strong>City</strong> Beautiful (vistas) and the Garden <strong>City</strong> (verdure). The genius ofNew <strong>Delhi</strong> till today is in its integration of vista and verdure.The most notable feature of the city is Rajpath (the grand central axis, called the “Central Vista”) anchored by theRashtrapati Bhavan at its western end and the Sports Stadium at the eastern end. One of the major nodesconceived by Lutyens for the Central Vista was the hexagonal ring road with the ceremonial arch, India Gate, andthe canopy, within the hexagonal landscaped area and the Princes’ Park (palaces of princely states) surroundingit.The focus of the British Colonial capital is the formal centerpiece, Rajpath (originally called Kingsway) runningeast‐west, radiating from the Rashtrapati Bhawan on Raisina Hill, flanked by the secretariat buildings on eitherside passing the hexagon that has the war memorial, known as the India Gate, and the Princes’ Park and ending atthe National Stadium towards the east. The focus point, the Rashtrapati Bhavan is sited on Raisina Hill,commanding views of the new city on every side and is flanked by the large blocks of Secretariat buildings facingRajpath. The great open space at the base of Secretariat is known as Vijay Chowk and marks the beginning of theadministrative centre of the city. The chowk approximately as wide as 260 ft, forms a cross‐axis at the foot ofRaisina and is also where the 'Beating Retreat' ceremony takes place on 29th January ever year. From Vijaychowk, a road perpendicular to Rajpath, leads to the Parliament House towards the north. Approximately 30mwide water channels surrounded by parkways and trees along Rajpath, on either side, add to the central vista’sgrandeur and also facilitate activities like boating, especially in the months of Feb‐April and Oct‐Nov when the cityis neither too hot nor cold.The width of this ceremonial avenue is such that twelve rows of trees are planted across the street, providingshade, as mentioned above. An extension of the symmetry that characterised the principal buildings of New <strong>Delhi</strong>is seen in the tree planting. The disciplined setting and framing of the principal buildings like the RashtrapatiBhavan, the Secretariats and the Law Courts is a result of the matching tree species flanking the streets.At the eastern end, the central vista terminates in a large hexagon, that has the iconic India Gate and 100m fromthere, a chhatri (canopy) that stands in the middle of a large pool of water, placed right in the centre of thehexagon. The hexagon has landscaped greens and a children’s park. Radiating from the hexagon are avenues, aswide as, 70 ft.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 14

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONThe outer periphery of the hexagon is known as the Princes’ Park, as it is surrounded by the palaces of the mostpowerful Indian Princes, who were allotted lands within this prime location. In all, three dozen lots (of about eightacres each) were leased out to the princes. The most powerful states – Hyderabad, Baroda, Bikaner, Patiala, andJaipur – were given lots forming a ring around the canopy on King’s Way. Lesser princes (including those ofJaisalmer, Travancore, Dholpur, and Faridkot) were given lots further out along the roads radiating from thecentral hexagon. Hyderabad House is the first palace to appear as one moves clockwise around the hexagonalround‐about from India Gate. Right next to it is another palace in buff sandstone, the Baroda House. Movingahead is Patiala House which lies between Tilak Marg and Purana Qila Road. Although part of the Princes’ Parkarea, the National Stadium, designed by R. T. Russell of the Public Works Department (PWD) falls next,approximately 400 ft away from the canopy which appears right opposite. The Dhyan Chand National Stadium,built in 1933 is used as a multipurpose stadium serving international and national events all along the year. Thissite along the eastern end also marks the culmination of the central vista, which radiates from the main entranceof the Rashtrapati Bhavan. Traversing along the outer hexagon, situated between Sher Shah Road and Dr ZakirHussain Marg is the Jaipur House, after which appears Bikaner house, located between Shahjahan Road andPandara Road.The main cross axis, Janpath was the Queensway of British New <strong>Delhi</strong>, and it runs from north to south connectingConnaught Place, the commercial hub in the north to a circle south of Rajpath, at the southern end of colonial,New <strong>Delhi</strong> (near Lodhi Garden). It is marked by the presence of two buildings viz. the National Archives and theNational Museum. On the roads leading out of Connaught Place are other equally important buildings, bothmodern as well as colonial. There are, for example, pre‐Independence buildings like the Eastern and WesternCourts; the Imperial Hotel, New <strong>Delhi</strong>’s first luxury hotel opened in 1931,and though nondescript on the outside,is home to one of the best collections of British art on India. The Eastern and Western Courts stand on either sideof the broad Janpath Road, south of Connaught Place.The road was often compared with the Champ Elyse's ofParis because of the beautiful buildings along it.A diagonal axes links Rajpath with the Parliament House. The Church of the Redemption is located on ChurchRoad, sandwiched between Parliament House on its west and the Jaipur Column on its north. North of this areaare largely institutional buildings with some government housing. The 'Cathedral of the Sacred Heart' also knownas the 'Sacred Heart Cathedral Church' is a Roman Catholic Church situated at 1 Ashok Place between SaintColumbus School and Convent of Jesus and Mary. Directly opposite the Sacred Heart Cathedral, standing in themiddle of a traffic circle, is the Gole Dak‐khana (literally, ‘round post office) General Post Office (GPO). Further afield, are other colonial buildings like the Gole Market.The area to the north of Rajpath, is filled with several institutional buildings and residential bungalows, built tohouse public servants of a lower rank. Some of these were designed by Herbert Baker and other by the PublicWorks Department. This area is wholly and completely of twentieth century vintage with a few exceptions.Scattered across it – and in an often unusual but pleasing juxtaposition of old and new – are older monuments:Agrasen ki Baoli which is a step‐well dating back to the fifteenth century and the impressive observatory known asJantar Mantar that was built in the eighteenth century. Though not as old as either the baoli or the observatory,are the Hanuman Mandir and Gurudwara Bangla Sahib, both medieval buildings that were already in existencewhen Connaught Place was built. Lutyens effortlessly integrated these structures into his plan for the new city.Lutyens' most important contribution was however not the buildings he designed but the layout of the city thatremains unchanged. His street plan for New <strong>Delhi</strong> has wide, tree‐lined avenues, with bungalows in large garden31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 15

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONplots, and wide areas of park between the public buildings, making <strong>Delhi</strong> one of the greenest cities in Asia. Arange of avenues from a modest 70 ft to 260 ft, fan out from Rajpath towards the south of the city giving accessto the bungalows. Rotaries and hexagons much like mini‐gardens with frangipani, Asoka trees, and bushes ofbougainvillea in myriad hues. Flowerbeds, seasonal flowering trees and bushes, shrubs and creepers bordered thelawns. Dense hedges that enclose the bungalow properties act not merely to keep away the dust and serve aswind‐breakers but also mellow the noise of the traffic from the street. The road system with its elaborateroadside planting is an important attribute of the planned city of New <strong>Delhi</strong> and is therefore a valuable part of<strong>Delhi</strong>’s heritage.The greenscape of the city is an expression of the much talked about ‘Garden <strong>City</strong> Concept’. An overwhelmingmajority of the trees species are evergreen or semi‐evergreen. The spacing of the trees along the avenuesprovides much needed shade to counter the extreme heat of north Indian summers. The decidedly Indianambience is because three‐quarters of the species are Indian natives, viz, jamun, tamarind, neem, fig, laburnum,gulmohar, jacaranda,etc.The largest trees, most significant in shape and densest of foliage are along the approaches to the city’s mostimportant buildings (the Jamun is along the central vista) while smaller tree species with lighter foliage and a lessdefined canopy are along roads considered less important.The visual impression of spaciousness that contributes to <strong>Delhi</strong>’s uniqueness is because a single species is plantedalong the entire length of a particular road . In one instance only, along Willingdon Crescent, there is a changewhere an alternate planting of two tree species is visible.A particular tree species is not confined to a single street but extends to a series of adjoining streets. A journeythrough them has the character of journeying through an integrated planting design. The Jamun trees along theRajpath is accompanied by a converging plantings of jamun trees along Raisina Road and Motilal Nehru Marg. Theview from India Gate up the Rajpath is accompanied by radiating views up Akbar Road and Ashoka Road withmatching plantations of Arjun trees and up Prithviraj Road and Curzon Road with matching plantations of NeemTrees. The planting of Arjun trees along the roads leading into Connaught Circus, continues in the planting ofArjun trees along the Janpath.The mature trees are internal green reserve within a vibrant, swiftly growing metropolis. Perhaps no other city inthe world boasts of such elaborate roadside planting!An integral feature of the city is the housing south of Rajpath for senior bureaucrats set within large treedominatedcompounds that create enduring symbols of power within the planned city. The bungalows arespread across the angled roads that are shaded by avenue plantation. In New <strong>Delhi</strong>, there was a strict hierarchyof accommodation according to rank or precedence of the British official. The bungalows of the senior officialshad upto seven bedrooms, and those for lesser ranks ranged from three to six bedrooms. What is visible today isa range of sizes and types.Each bungalow is sprawled in its plot of land, in some cases covering several acres. Each bungalow comprises of aseries of rooms and spaces with often little or no connection to the grounds outside. In contrary to the havelihouse form where the gardens and open spaces lay inside the shell of the building, for bungalows, the exactopposite is true.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 16

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONThe bungalows are whitewashed and characterized by high ceilings, clerestory windows positioned high in thewalls, and shady verandas. They display some classical European (especially Palladian) touches, and someindigenous elements – like chhajjas (dripstones) and occasionally, internal courtyards‐ were included. Keeping inmind <strong>Delhi</strong>’s chilly winters, fireplaces are present in some of the main rooms, along with accompanying chimneysjutting out above the flat roof. A variation is where the verandahs and loggias are reduced or done away with.Servants’ quarters are separate buildings, away from the main dwelling.A description of the key buildings:Rashtrapati Bhavan or the 'President's House ( designed as the British Viceroy’s residence) is situated on RaisinaHill. Built of red and buff sandstone, it is generally acknowledged as the largest residential complex, ever built forthe head of any country. It has 340 well decorated rooms. The Durbar Hall or throne room which was designed tohost all official functions, is a grand hall directly underneath the main dome. Another important hall in theRashtrapati Bhavan is the Ashoka Hall, formerly the ballroom, with its walls and ceiling painted with scenes fromPersian poetry. Besides these two halls, is the State Dining Room (for formal banquets), a large number of guestsuites and the private apartments. Rashtrapthi Bhavan has the most exquisite chandeliers imported from Europe,furniture, Kashmiri carpets in Mughal designs.Jaipur Column, standing 145 ft high in front of Rashtrapati Bhavan, is made of buff sandstone, topped with abronze lotus and a glass star. Inspired largely by Trajan’s Column in Rome, it was designed by Lutyens anderected under the aegis of the Maharaja of Jaipur, to whom much of the land on which New <strong>Delhi</strong> was builtoriginally belonged. The plan of New <strong>Delhi</strong>, with its major axes marked out, is carved onto the plinth of the JaipurColumn.The Mughal Gardens, the setting for the majestic building, cover an area of 13 acres and are divided into threesections, one circular in shape, another rectangular and the third a long rectangle. As in the traditional Mughalgarden, there are water channels and pools, chhatris, parterres, and carved fountains using the same sandstoneas the palace, in the shape of lotus leafs' at every intersection of the four waterway canals and multi levelterraces with chhatris.North and South Blocks Designed by Herbert Baker, these two identical buildings facing each other acrossKing’s Way are situated on Raisina Hill, a little below Rashtrapati Bhawan. The North Block and South Block of theSecretariat house important ministries of the Government of India. The ministries of Finance and Home Affairsoccupy the North Block. Today, the South Block is home to the Prime Minister’s Office, and the ministries ofDefence and External Affairs.The blocks sit on a plinth about 30 ft above the ground and are connected by an underground passage (still inuse). This elevation of the buildings on raised platforms meant that the view of the Rashtrapati Bhawan wasblocked by the slope leading to these buildings. They are made of buff and red sandstone, with red sandstoneforming a broad ‘base’ for the outer walls. Between them, the four‐storied Secretariat buildings have about 4,000rooms. The premises include formal gardens with water fountains, pillars and porticos with vaulted ceilings.Classical in style, each block is crowned by an imposing central baroque dome.Outside each block are two sandstone columns – a total of four columns in the Secretariat. These, known as theColumns of Dominion, were ceremonial gifts to India from the colonies of Britain which had dominion status:Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and South Africa. Each column is topped by a bronze ship in sail (to symbolize31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 17

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONBritain’s maritime traditions). The ship rests on a replica of the Ashokan capital: a lotus blossoming above awheel, flanked by a horse on one side and a bull on the other. There are stone tablets fixed at the sandstonesbases of the buildings on which the names of the architects and builders are inscribed.The Secretariat Buildings are not only impressive and majestic from the outside but their interiors are equallyinteresting. Both blocks have original paintings decorating some walls and ceilings. The North Block containssome very well preserved paintings depicting various themes like justice, war and peace. The South Block too haspaintings of different cities of the country and the emblems of old kingdoms.Designed originally as cold‐season offices, the Secretariats were constructed without the continuous verandahswhich are normally used in India as sun shields. Instead, windows were kept small in proportion to wall area, andtheir glass was deep‐set in thick walls away from high rays of the sun. Teak jalousie shutters screened the low sunof morning and evening. Lighting of rooms could be better adjusted as a result, and offices were not as gloomy inwinter with verandahs.India Gate India Gate is arguably one of the most striking arched memorials of its kind, anywhere in theworld. Its relatively plain façade and clean lines stand in sharp contrast to the more ornate appearance of theSecretariat buildings or Rashtrapati Bhavan. Like these buildings, though, India Gate is also composed mainly ofbuff sandstone. Its wide columns rise from a low base of red sandstone. Between the narrower sides of thecolumns are two large sandstone pine cones, symbolizing eternal life.Topping the arch is a shallow dome with a bowl to be filled with burning oil on anniversaries to commemoratemartyrs. There is a similar structure under the arch, with an ‘eternal flame’, burning constantly in memory ofIndia’s dead soldiers. This is in the form of a plain square shrine of black marble, atop a stepped platform of redstone. From the centre of the black shrine rises an upturned bayonet supporting a helmet – a symbol of theunknown soldier. On each of the corners of the red stone platform is a constantly‐alight flame. The shrine isknown as the Amar Jawan Jyoti (literally, ‘flame of the immortal warrior’.Hyderabad House The most elaborate and biggest of all the princely estates is this majestic cream‐painted,buff sandstone building, the Hyderabad House, designed by Lutyens himself and built in 1926. The palace, like theneighbouring princely palaces, sits on a wedge‐shaped plot of land. To use this shape to its best advantage,Lutyens designed the Palace of the Nizam of Hyderabad (as Hyderabad House was initially known) in a butterflyshape. However, the building plan is as if the butterfly is ‘halved’, leaving it with two wings, one facing each of thetwo roads that flank the palace: Ashok Road on the left and Kasturba Gandhi Marg on the right. Hyderabad Houseis more clearly classical in origin than the other Imperial buildings, and is less ornate and yet more original as atypology. The entrance hall of the palace and a domed roof are the outstanding features of the building. Thecream‐painted, buff sandstone palace with 36 rooms were designed to inspire awe: it has broad, sweepingstaircases, marble fireplaces, and floors decorated with rich patterns. Archways, obelisks, large stone urns, grandstairways, marble fireplaces and exquisitely detailed patterned floors are some of the design elements which canbe found in the interior of Hyderabad House. Currently the palace is in use by the Government, specifically theministry of foreign affairs for press conferences, banquets, and meetings. Four of the rooms have now beenconverted into dining rooms.Baroda House This is a building in the Anglo‐Saxon style, with the dome echoing that of the Sanchi stupa. Thebuilding is of buff sandstone, and from above resembles a butterfly cut in two down the centre: one of its ‘spreadwings’ faces Kasturba Gandhi Marg, the other Copernicus Marg. It has large French windows with semi‐circular31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 18

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONarches; a portico; and unornamented Doric columns. The carved screens of the walls surrounding the terraces aremore European in style than the ornate jaali screens Indian stone‐carvers were used to making. Baroda Housetoday houses the headquarters of the Northern Railway.Patiala House Like Baroda House, Patiala House – built in 1938 for the Maharaja of Patiala – was designed byLutyens as a ‘butterfly house’, where the two wings of the building are joined together with a dome above. Thepalace is painted cream, with sections of buff sandstone left bare to highlight balconies, parapets, and carvedventilator screens. An interesting feature is the distinctly Indian touch provided by a square, domed pavilion onthe roof, with a chhajja and four smaller pavilions clustered around it.National Stadium Although part of the Princes’ Park area, the National Stadium was designed by R. T. Russell ofthe Public Works Department (PWD). It is named the Dhyan Chand National Stadium, in honour of Major DhyanChand Singh (1905‐1979), one of the world’s finest hockey players. The building has a main entrance consisting offive large arches. The rest of the building is a combination of western and Indian architectural styles. Prominentamong the Indian elements are the chhajjas and the chhatris that stand above the arches.Jaipur house Designed by Arthur Bloomfield in 1936 for the Maharaja of Jaipur, it remained true to Lutyens’svision of New <strong>Delhi</strong>. Like the Lutyens‐designed palaces in Princes’ Park, Jaipur House too is a ‘butterfly house’,with a dome atop the centre. Built mainly of buff sandstone, the building has architectural elements that run thegamut from Art Deco to traditional Indian. The dome resembles the one on Rashtrapati Bhavan; a chhajja of redsandstone runs continuously below the roof; there are multiple strips of red sandstone inlaid to form a patterneddado and Rajput columns form arched openings along the façade. Jaipur House is today the National Gallery ofModern Art (NGMA). After India’s independence, when the princely palaces around India Gate became thegovernment’s property, it was realized that the large rooms and high ceilings of Jaipur House would be theperfect exhibition space for a gallery of modern art.Bikaner House The building Lutyens designed for Ganga Singh, the Maharaja of Bikaner is the most understatedand least striking of the buildings of Princes’ Park. The palace has large verandahs along the front, a backyard andextensive gardens – all of which were typical features of the bungalows Lutyens designed in New <strong>Delhi</strong>. BikanerHouse is now the office of Rajasthan Tourism.Connaught Place Connaught Place, popularly known by it's initials as ‘C.P.’ has now been officially namedRajiv Chowk. It is the prime business and commercial centre of New <strong>Delhi</strong>. Inaugurated in 1935, as the mainshopping district of New <strong>Delhi</strong> , Connaught Place, characterized by Georgian buildings, was designed by RobertTor Russel (1888‐1977). Connaught place is a two‐storied structure with an open colonnade, in two concentriccircles, creating the Inner Circle, Middle Circle and the Outer Circle. The circle was designed with eight radialroads that stretch out of the inner circle of Connaught Place like wheel spokes and twelve radial roads stretch outof the outer circle of Connaught Place leading you out of this centre and connecting it to other parts of <strong>Delhi</strong>.The centre of the complex, the Inner Circle, comprises an underground market, Palika Bazaar, which spreads outall the way to the Outer Circle. Also an important part of Connaught Place is the aptly‐named Central Park, withan amphitheatre and water bodies serving as one of <strong>Delhi</strong>’s major venues for concerts and cultural events.The buildings that make up the outer and inner circles have spacious colonnaded verandahs, beyond which areshops and establishments of various types ranging from restaurants, coffee homes and confectioners, to cinematheatres and travel agents. First floor apartments are used as shops with only a few residents remaining. All the31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 19

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONblocks of Connaught Place and Janpath Market are connected by a system of underground pedestrian subways.Connaught Place is surrounded by major ‘Roads’ such as the Barakhamba Road, Baba Kharak Singh Marg,Kasturba Gandhi Marg and Panchkuian Marg.Eastern and Western court These are two striking buildings, both cream‐painted, with rows of tall columns,semi‐circular arches and deep verandahs forming a backdrop against lawns and trees. Both buildings weredesigned by R.T. Russell, and were built in the 1930s, around the same time as some of the other importantgovernmental buildings of New <strong>Delhi</strong> were built. Russell’s style was in keeping with the style adopted by Lutyensand Baker for the residential buildings and minor offices that were to be part of the new capital.The Western and Eastern Courts were originally planned to be used as hostels for legislators. The Western Courtstill serves a similar purpose: it is designated as a transit hostel for Members of Parliament. The Eastern Courthouses a post office and is also home to some offices of the Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd (MTNL).Parliament BuildingParliament House stands north‐west of Vijay Chowk (at the foot of Raisina Hill)and was designed by Herbert Baker. It is a circular, four‐storeyed building, ringed on the outside by a colonnadedverandah. There are 144 columns made of sandstone, each measuring 27 feet in height. The edifice, mainly ofbuff sandstone, sits on a red sandstone platform and sprawls over six acres. It is 171 meters (560 ft) in diameter.The structure consists of a central hall topped by a dome and three semi‐circular chambers that are surroundedby garden courts. The boundary wall has blocks of sandstone carved in geometrical patterns that echo the Mughaljaalis of the type found at the Red Fort in <strong>Delhi</strong>. The three semi‐circular chambers housed the Chamber of Princes,the Council of State, and the Legislative Assembly. In present‐day India, the Rajya Sabha (the Upper House) holdsits sessions in one chamber, while the Lok Sabha (the House of the People) uses the other chamber. The Chamberof Princes, unlike the much simpler Council of State chamber, has carved screens to allow women members inpurdah to attend sessions, when the Supreme Court was housed in the Chamber of Princes.Church of Redemption The stunning architectural design of Henry Medd, took shape through Lord Irwin'ssupport and the structure was completed in 1931. The Church reflected the imprints of the Palladio Church inVenice and the Hampstead Church designed by Sir Lutyens. The church has a fine organ and a silver cross donatedby Lord Irwin, there is also a striking stained glass window which depicts a cross and was installed quite recently.Cathedral of the Sacred Heart The church designed by Henry Alexander Medd sits on a vast expanse of 14 acres.The Sacred Heart Cathedral’s cream‐and‐red painted façade is in distinct contrast to the somewhat staid buffsandstone monuments that dominate the landscape of Lutyens’s <strong>Delhi</strong>. This is an Italianate structure, with atriangular pediment supported on columns forming the central part above the entrance. On either side of thepediment rise two triple‐storied, arcaded towers. Inside, the cathedral has a vaulted ceiling and stone floors. Thealtar is made of pure Carrara Marble.St Columba’s School Standing adjacent to the Sacred Heart Cathedral, the boys‐only St Columba’sSchool was established in 1941 by the Indian province of the Congregation of Christian Brothers (an organizationfounded by an eighteenth‐century Irishman, Edmund Rice). The two‐storeyed red brick building, has archedcolonnades along the façades on both storeys. Semi‐circular arches highlighted in white, along with white twincolumns, form the main decorative elements of the structure. Newer buildings have been added, expanding theoriginal school, over the years.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 20

Medieval And Colonial Capital Cities Of <strong>Delhi</strong>DESCRIPTIONGole Dak‐khana Gole Dak Khana which means round post office was designed by R.T. Russell, the postoffice was built in the 1930s. It was originally called Alexandra Place and was the office of the Central PublicWorks Department (CPWD) till the 1960s, after which it was converted into a post office – a function it still fulfils.The exterior of the Gole Dak‐khana is relatively plain, adorned with semi‐circular arches and columns at theentrance. It’s painted in a combination of white and buff, with a good deal of red – the official colour of India Post– at the entrance.Gole Market Literally, ‘the round market’, isn’t a technically correct description for this market, since it’s notreally circular. Built as part of the new city, Gole Market, its architect, G. Bloomfield, designed it as a twelve‐sidedring surrounding an open central courtyard. Six entrances, in the form of semi‐circular arched gateways, piercethe ring, leading into Gole Market. On the southern edge of the market are three circular colonnaded markets,built at the same time as the Gole Market.Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, 1930, formerly the Residence of the Commander‐in‐Chief (FlagstaffHouse) Originally known as Flagstaff House, it was built on the axis of one of the avenues radiating outwardsfrom Viceroy’s House and therefore, has a direct view of the dome of the Durbar Hall. The central section of theresidence of the Commander‐in‐Chief has an architectural motif that runs like a leitmotif through <strong>Delhi</strong>’s imperialarchitecture – an enormous verandah with pillars, enclosed with walls and set on a massive base. Its longsymmetrical mass, completed in 1930, has motives that have been used in the Viceregal palace, the HyderabadHouse and in the cluster of cultural edifices Lutyens designed for Rajpath. Recessed windows and deep arcadesimplie massive solidity. The restrained classicism of the palatial interior, exemplifies the serene and even severecornice and fireplace details of the barrel‐vaulted reception room.These two cities combined together, though originally a symbol of imperialism for the Indians, the ‘new city of<strong>Delhi</strong>‘, along with the historic Mughal city gives the city its primary identity, as the political capital of the nation.31‐07‐2012 INTACH, <strong>Delhi</strong> Chapter 21