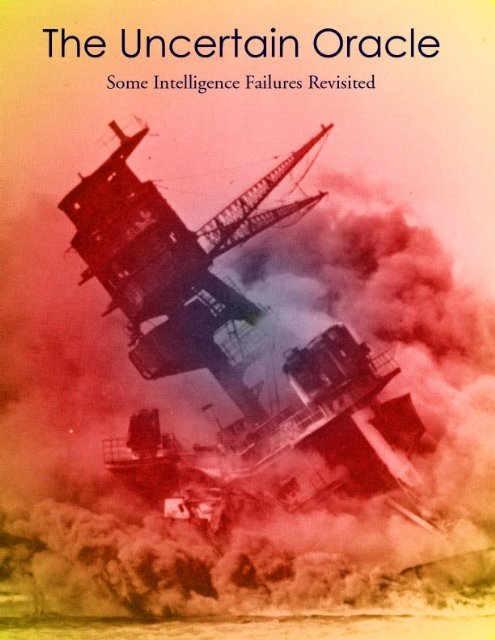

The Uncertain Oracle: Some Intelligence Failures ... - U.S. Army

The Uncertain Oracle: Some Intelligence Failures ... - U.S. Army

The Uncertain Oracle: Some Intelligence Failures ... - U.S. Army

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

In an article about “<strong>Intelligence</strong> and Military History,”Keith Jeffery reflects that because of thelack of a historical record about MI operations,“we usually know more about intelligence failuresthan successes.”1 This observation has thering of another eternal verity. <strong>The</strong> time devotedto dissecting intelligence failures is indicative ofthe human frustration at not being able to predictthe future with any consistent success. <strong>The</strong>re isan all too prevalent tendency in American society(the press, the congress) to call anything lessthan clairvoyance a failure. For many critics,the military intelligence analyst has no more scientificunderpinning than the racetrack tout, stockmarket tipster or the cover-all-bases predictionsof Jeanne Dixon. It is not enough to say that thisattitude probably arises from growing accustomedto a usually reliable intelligence gathering apparatus,so that exceptions become even more jarringto our sense of safety.<strong>The</strong> successes of military intelligence in diviningenemy intentions often go to the grave withthe operatives or to the shredder with their restrictivesecurity classifications intact. This is felt tobe necessary to prevent an enemy from emulatingor thwarting those successes. While someimportant historical lessons are lost in this way,there are enough lessons to be learned from thefailures to keep historians occupied for a time.So yet another catalog of intelligence failure ispresented here along with some analysis of wherethe breakdown may have occurred. I have concentratedon examples that directly affected U.S.military operations.A nation is facing increasing hostility from itsneighbor. Raids across its borders increase untilfinally a major attack is made on its sovereignty.It comes as a complete surprise to the United Statesgovernment. <strong>The</strong> press is agitated by the failureof the government to predict this move. Politiciansfume. <strong>The</strong> situation described could be the1950 attack on South Korea by the CommunistNorth, the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia,the Arab surprise attack on Israel in 1973,the 1979 Chinese invasion of Vietnam, the Iraqiattack on Iran in 1980, the Argentinean invasionof the Falklands in 1982, or Saddam Hussein’ssudden overwhelming of Kuwait in 1990. <strong>The</strong>scenarios are often the same. In this instance, Iam referring to the 1916 attack by Mexican bandit/revolutionaryPancho Villa on the Americantown of Columbus, New Mexico.Villa hit the sleeping town on 9 March 1916with a force of 485 men. <strong>The</strong> town and the garrisonwere totally surprised. Having sent men intothe town the previous afternoon, he knew thatthere were only 30 soldiers in the garrison of the13th Cavalry. He broke off the attack at 6:30a.m., leaving behind 67 Americans dead and 13others dying of their wounds.<strong>The</strong> day before the attack, the foreman of aranch reported to Col. Herbert H. Slocum, commandingthe 13th Cavalry at Columbus, that hehad seen Villa’s force just six miles to the south.Other observers contradicted this report and itwas not taken seriously. In fact, farmers andranchers along the border were nervous andsightings of the Mexican bandits were legion.<strong>The</strong> threat of raid on American soil was a realone. In the year preceding the Villa attack, therewere 38 raids on the U.S. by Mexican bandits,resulting in the death of 37 U.S. citizens, 26 ofthem soldiers.Maj. Gen. Frederick Funston, commanding theSouthern Department at San Antonio, Texas, respondedto the press uproar that followed whenhe said in his 1916 Annual Report:Much has been said about whether ornot this attack was a surprise. If therewas any person in the country who wasnot surprised at such an attack by a largebody of armed troops coming from a nationwith whom we are at peace, that personmust have been one of those residentsof the immediate vicinity, who were allegedto have known of the plans for theattack, or to have guided Villa’s troops inthe attack....2I use this example to show that there are someconstants in history, despite the revolutionaryadvances in technology. In this instance, as inmany to come, an intelligence failure was accompaniedby an operational lapse. <strong>The</strong> garrison atColumbus had settled into a routine and despite38 previous raids, vigilance was lax.Early in the 20th century intelligence was notrecognized as a separate and distinct military discipline.<strong>Intelligence</strong> gathering was primitive and

when their aircraft production was underestimatedby half, their pilot training pronounced inferior,their Zero fighter remained a mystery, their sonargear was written off as substandard, and thenumber of aircraft on their carriers wasundercounted.7<strong>The</strong> question of where an attack would fall waswrongly answered just before Pearl Harbor whenanalysts prepared a list of possible targets whichomitted Hawaii altogether. Although U.S. plannershad considered Hawaii a potential target intheir training exercises for many years, the widespreadbelief that the islands were an impregnablefortress tended to cause U.S. intelligence to writeit off as a possibility.Warnings were dispatched to Admiral Kimmelby the Chief of Naval Operations and by the WarDepartment. On 27 November the CNO sent thismessage: “An aggressive move by Japan is expectedwithin the next few days.... <strong>The</strong> numberand equipment of Japanese troops and the organizationof naval task forces indicated an amphibiousexpedition against either the Philippines, Thaior Kra Peninsula, or possibly Borneo. ...Executean appropriate defensive deployment.” On thesame day the War Department said, “Negotiationswith Japan appear to be terminated...hostile actionpossible at any moment.” On 3 Decemberthe CNO warned, “Highly reliable informationhas been received that categoric and urgent instructionswere sent yesterday to Japanese diplomaticand consular posts at Hongkong, Singapore,Batavia, Manila, Washington, and London to destroymost of their codes and ciphers at once andto burn all other important confidential and secretdocuments.”8 Since none of these messagesspecifically mentioned Hawaii and because theJapanese were not told to burn all of their codes,no special importance was attached to them.<strong>Some</strong>times even apparent signals are rendereduseless by operational inaction. U.S. defenseplans anticipated that a single submarine attackwould mean that a larger surface force was in thearea. Yet when an enemy submarine was confirmedin the area on 7 December at 0640, therewas no change in alert status.9When Col. Rufus S. Bratton, the chief of <strong>Army</strong>Far Eastern <strong>Intelligence</strong> in Washington wastroubled by the implications of the new informationintercepted via the “winds” code and wishedto relay that information to his counterpart inHawaii, he was thwarted by the high security classificationwhich could not be sent through normalchannels. So instead he sent a message in theclear instructing the <strong>Army</strong> intelligence man inHawaii, Lt. Col. Kendall J. Fiedler, to “ContactCommander Rochefort immediately thru CommandantFourteenth Naval District regardingbroadcasts from Tokyo reference weather.”Upon receipt, the untrained and inexperiencedFiedler in Hawaii filed the message and did nottry to see Commander Rochefort. He simply didnot see any urgency in this routine kind of message,especially since he did not expect any Japaneseattack.10Likewise, when Admiral Husband E. Kimmelwas informed that the Japanese were destroyingtheir codes in London, Washington and Far Easternconsulates, he attached no particular importanceto it vis-a-vis his situation. To congressmenand military leaders studying the event afterthe war, destruction of codes was an “unmistakabletip-off” and put Admiral Kimmel’s judgmentin question. But while the admiral might assume,as everyone did after the fact, that this meant war,he did not necessarily come to the conclusion thatPearl Harbor would be attacked. And burning ofclassified documents by the Japanese was a regularoccurrence at the consulate in Honolulu.No one in the Far East U.S. military establishmentseriously believed that Pearl Harbor was aserious target to the Japanese. So it became easierto misinterpret those signs that pointed to thispossibility. <strong>The</strong> human tendency to explain eventsaccording to their own expectations and beliefs,and the resistance to any information that overturnstheir opinions were key factors in the PearlHarbor intelligence failure. Other factors werethe mass of conflicting information, the Japanesesuccess at keeping their intentions quiet, deceptionoperations, sudden changes in military capabilitiesthat caused, for instance, U.S. estimatesof the range of the Zero to fall short, and ourown communications security which not onlydenied information to the enemy but to key Americanofficers as well.After Pearl Harbor, congressional findingsmade note of the tendency of military men to ac-

cept personal responsibility for actions withoutasking for orders from a superior.While there is an understandable dispositionof a subordinate to avoid consultinghis superior for advice except where absolutelynecessary in order that he maydemonstrate his self-reliance, the persistentfailure without exception of <strong>Army</strong> andNavy officers...to seek amplifying andclarifying instructions from their superiorsis strongly suggestive of just one thing:That the military and naval services failedto instill in their personnel the wholesomedisposition to consult freely with their superiors.11Wohlstetter found in her study of Pearl Harborthat there was a general prejudice against intellectualsand intelligence specialists. She said,“[intelligence officers’] efforts were unsuccessfulbecause of the poor repute associated with<strong>Intelligence</strong>, inferior rank, and the province ofthe specialist or long-hair.”12Analysts receive information piecemeal over aperiod of time and seldom are able to evaluatethe cumulative weight of their information. Thiswas true before Pearl Harbor when Magic interceptswere sent to decision-makers one at a time.A messenger waited outside their offices until thefile was read and then carried it to the next personon the list. So the fragments were never consideredas a body of evidence.Expectations have a big part in determininghow information will be interpreted. For example,the chief of <strong>Army</strong> intelligence in Hawaii was notexpecting a Japanese attack. As a result, whenhe received warning of the Japanese destroyingtheir codes, he attached no importance to it andmerely filed the message.13 An <strong>Army</strong> lieutenantreceived information from a radar station of aflight of approaching aircraft on morning of December7th. He readily believed that the flightwas friendly and told the radar operators to forgetit. <strong>The</strong> “wishful-thinking” phenomena isclosely related to expectations. It projects thedesires of an individual into the expected outcome.It is easy to misjudge the importance of newinformation in light of strongly held theories.Admiral Kimmel probably did so when he learnedin a “for action” warning that the Japanese weredestroying their codes. This Japanese action wasconveniently taken to mean that an attack wouldtake place in Southeast Asia, the belief of theAmerican leaders in Hawaii all along. So thisreport was not even passed on to the <strong>Army</strong> headquartersin Hawaii.Another example of the tendency to reshapeinformation to fit preconceptions was the October1941 intercept of a Tokyo request of the Honoluluconsulate for information on the exact numberand location of U.S. warships in the harbor.No special importance was placed on this requestbecause, said the Chief of Naval Operations AdmiralHarold Stark, “We knew the Japanese appetitewas almost insatiable for detail in all respects.<strong>The</strong> dispatch might have been put downas just another example of their great attention todetail.”14Of course, it was not entirely a failure of intelligence.Operational planning must be faulted aswell. Even if the signs of the imminent attack onPearl had been correctly interpreted and the warningdisseminated, the victims of the attack musthave sufficient time to react, to get into their defensiveposture. Because the surprise attackershave a definite advantage in timing, seldom is theretime to get ready. Placing troops on constant alertis not feasible. That exhausts both soldiers andpatience. High levels of readiness cannot be sustainedover long periods of time. <strong>The</strong>re are alwayspeaks and valleys.15Wohlstetter concluded her definitive study ofthe catastrophe at Pearl Harbor with this cautionfor the future: “We have to accept the fact ofuncertainty and learn to live with it. No magic,in code or otherwise, will provide certainty. Ourplans must work without it.”16Ephraim Kam reached a similar conclusion thatsurprise attacks were inevitable when he said,“History does not encourage potential victims ofsurprise attack. One can only hope to reduce theseverity—to be only partly surprised, to issueclearer and more timely warnings, to gain a fewdays for better preparations—and to be more adequatelyprepared to minimize the damage oncea surprise attack occurs.”17<strong>The</strong> War Department General Staff began itsown study of the Joint Congressional Committeeon the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack

and published its findings in January 1947. <strong>The</strong>study analyzed the “evidence from the broad intelligenceviewpoint” and drew its lessons fromthe analysis. Many of their findings and recommendationshave been overtaken by changes inmilitary intelligence organization and technology.But some of the lessons they surfaced can be validin any era.Its first conclusion was there was a lack of appropriationsfor military intelligence. That is aperennial problem that will stay with Americansociety. A second finding was that “intelligencetraining was not given sufficient weight in the selectionof high-level intelligence staff officers.”Emphasis was put on operations and command in<strong>Army</strong> schools and that meant that more prestigewas attached to those positions. “<strong>The</strong> net resultwas a tendency to consider the <strong>Intelligence</strong> Officerin a junior advisory capacity and to usurphis evaluation functions.” <strong>The</strong> study recommendedthat “through the school system and militaryintelligence publications, the importance ofstrategic intelligence and its evaluation by trainedpersonnel be stressed.”A third conclusion was that “at every levelthere were failures to place sufficient credence inthe incomplete intelligence at hand to insure thatwithin existing capabilities no action was omittedwhich might improve our security against attack.”“Dissemination of intelligence and informationfrom Washington to the field was not adequate...tokeep the field...informed. Conversely, the fieldpersonnel did not at all times forward all the informationcollected by their commands whichwould be of interest to the various intelligenceagencies in Washington.”Often security precautions kept informationfrom being disseminated or slowed its flow.A final finding found fault with the analysis anddissemination of information.<strong>The</strong> principles of the importance of firstinformation and of prompt dissemination ofthe conditions of first contact were widelyoverlooked. Japanese intention to attack PearlHarbor was widely rumored in Japan at aboutthe time we later learned it was first proposedby Yamamoto, but the rumors were disregardedas fantastic and soon forgotten. Later,when the Japanese moved into Indo-China,this was properly interpreted at all levels asindicating a complete break soon. However,no one in a position to act realized that thelogical target for initial surprise attack wasour fleet at Pearl Harbor, the one means wethen had to oppose their further obviouslyadvertised intention to continue south. Finally,when their forces were first contactedat Hawaii, the significance of the contacts wasmissed until the bombs fell.<strong>The</strong> five members of the study commission recommended“that there be required as a part ofevery course in all service schools a subcoursestressing the importance of rapid disseminationof first information and first contact, not only in ameeting engagement after hostilities have commencedbut also at any time the status of foreignrelations indicates that there is a possibility ofwar.”18KoreaIn the moments before dawn on 25 June 1950,the North Korean Peoples <strong>Army</strong> moved out oftheir forward positions and swarmed into the Republicof Korea, supported by armor columns andplanes. For the most part, they swept the small,woefully underequipped, US-trained Republic ofKorea <strong>Army</strong> before them. <strong>The</strong> North Koreansachieved complete tactical surprise and wouldnearly overwhelm the peninsula before U.S.forces, under United Nations auspices, could landand establish a toehold at Pusan.<strong>The</strong> U.S. had a small, but organized intelligence-gatheringcapability on the ground in Koreain 1950. <strong>The</strong> U.S. <strong>Army</strong>’s Korean MilitaryAdvisory Group (KMAG) had officers workingwith every echelon of the ROK <strong>Army</strong> and wouldcompile intelligence on the North Korean <strong>Army</strong>.Because KMAG was assigned to the State Departmentrather than to General Douglas MacArthur’sFar East Command (FEC) in Japan, that informationwould bypass his headquarters and be reportedto Washington. To collect the informationhe needed, Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby,the FEC G-2, organized the Korean LiaisonOffice in Seoul which was in fact a detachment ofintelligence specialists. Additionally, the U.S.Embassy in Seoul had its military attaches and

political analysts working on the military situation.<strong>The</strong>se assets did their work. <strong>The</strong>y picked upplenty of warnings, like the evacuation of civiliansnorth of the 38th parallel, troop buildupsalong the border, and the positioning of suppliesand equipment in these forward areas. And therewas a four-year record of border skirmishes andarmed North Korean reconnaissance into theSouth.So frequently had the North Koreans raidedalong the border, including two limited invasionsof the South, that these kinds of incidents werereferred to by Secretary of Defense Louis A.Johnson as “Sunday morning incursions.” Eventhough there was a marked lull in the frequencyof the border incursions, another possible indicatorof an impending attack, no one thought theindicators of the 25 June Sunday morning attackto be out of the ordinary.Between June 1949 and June 1950, FEC intelligencedispatched 1,200 warnings to Washingtonof an impending NK attack.19 Artillery duelsand border incursions were common. Departmentof Defense was saying that the ROK<strong>Army</strong> was far superior to its Communist neighbor,leading officials to reject the possibility of aNK attack and to be confident that even if an attackoccurred, the ROKs could defeat the Northin “two weeks.” Analysts failed to evaluate thesignificance of T-34 tanks amassed at the borderand underestimated their capabilities to negotiateflooded rice paddies.20North Korean leader KIM Il Sung issued a proclamationon 7 June 1950 that elections would beheld “Korea-wide” on August 15th, the first timethat he had ever boldly asserted a deadline. Likeall such outpouring from the North, it was dismissedas propaganda.21<strong>The</strong> pattern took on increasing significance by1950 and General Willoughby was forwardingreports to Washington from his analysts who believedthat a North Korean invasion would takeplace in the Spring of 1950. Willoughby nonconcurred,saying “such an act is unlikely.”22James F. Schnabel reported in to the G-2, FEC,in Tokyo in November 1949 and was briefed onthe military situation in Korea. “A major fromthe G-2 section, quite frankly stated that the feelingin G-2 was that the North Koreans would attackand conquer South Korea in the coming summer.<strong>The</strong> point was not emphasized particularlyand the fact seemed to be accepted as regrettablebut inevitable.”23So the failure to predict the North Korean invasionof the South in 1950 was not one of failingto target the enemy, nor of failing to pick up thesignals. It was one of analyses at the higher echelons.In March 1950, Maj. Gen. Willoughbywas reporting:It is believed that there will be no civilwar in Korea this spring or summer....South Korea is not expected to seriouslyconsider warfare so long as her precipitatingwar entails probable discontinuanceof United States aid. <strong>The</strong> most probablecourse of North Korean action this springand summer is furtherance of attempts tooverthrow South Korean government bycreation of chaotic conditions in the Republicof Korea through guerrillas andpsychological warfare.24In the same month, the embassy in Seoul toldthe State Department that there was little possibilityof a North Korean invasion. In Washington,attention was focused elsewhere, on Indochinawhere a communist takeover appeared muchmore immediate. <strong>The</strong> Department of the <strong>Army</strong>G-2, Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling, was sayingin a March intelligence report that “Recentreports of expansion of the North Korean People’s<strong>Army</strong> and of major troop movements could beindicative of preparation for aggressive action”but that “Communist military measures in Koreawill be held in abeyance pending the outcome oftheir program in other areas, particularly SoutheastAsia.” This was at a time when the AirForce’s Office of Special Investigations was alertingthe Far East Air Forces that the Soviets haddefinitely ordered the North to launch their attack.It was also at a time when a remarkablenumber of indicators were piling up. DA G-2said in May that “<strong>The</strong> movement of North Koreanforces steadily southward toward the 38thparallel during the current period could indicatepreparation for offensive action.” A second intelsummary reported routinely that “the outbreakof hostilities may occur at any time in Korea....25

Another routine report, just six days before theinvasion, noted the evacuation of civilians fromthe border area, the replacement of civilian freightshipments with military supply movement only,large influx of troops, including concentrationsof armor, and large stockpiling of weapons andequipment. No analyses accompanied this rawdata, but coincidentally, on the same day, GeneralWilloughby wrote: “Apparently Soviet advisorsbelieve that now is the opportune time toattempt to subjugate the South Korean Governmentby political means, especially since the guerrillacampaign in South Korea recently has metwith serious reverses.”26Secretary of State Dean Acheson testified incongressional hearings:<strong>Intelligence</strong> was available to the Departmentprior to the 25th of June, made available bythe Far East Command, the CIA, the Departmentof the <strong>Army</strong>, and by the State Departmentrepresentatives here and overseas, andshows that all these agencies were in agreementthat the possibility for an attack on theKorean Republic existed at that time, but theywere all in agreement that its launching in thesummer of 1950 did not appear imminent.27<strong>Some</strong> of the reasons that highly placed Americanofficials discounted the intelligence indicatingan attack were an instinctive distrust of theirKorean sources who they felt were overstatingthe threat for their own purposes, and the factthat North Korean activity around the border wascontinuous and common. <strong>The</strong>y were also distractedby Soviet-instigated trouble around theglobe.<strong>Intelligence</strong> is given less validity if the sourceis rated as unreliable. South Korean officials weredoubted when they warned of a North Koreanattack because they had said the same thing somany times in the past and it was felt their credibilitywas doubtful if not self-serving. GeneralMatthew Ridgway wrote that MacArthur’s G-2staff did not rate its Asian agents as reliable becausethey felt “that South Koreans especially hada tendency to cry ‘wolf’ when there was no beastin the offing.”28A major reason that the leadership was so reluctantto accept the possibility of a North Koreanattack could well have been the psychologicalspecter that nothing had been done to preparefor such an eventuality, short of evacuating Americancitizens. <strong>The</strong>re were no contingency planson the shelf. In fact, the Republic of Korea hadbeen written out of the U.S. sphere of influencein a public speech given by Secretary of StateDean Acheson, a speech that is thought to haveemboldened the Korean communists.One way to dismiss contradictory informationis to question its validity or to simply pretend itdoesn’t exist. When the American ambassadorin Seoul reported a heavy buildup by the Northalong the 38th parallel, he was thought to be makinga case for his recent request for armor for theROK <strong>Army</strong> and thus ignored as an unreliablesource. It was commonly believed that NorthKorea did not have the power to attack the Southunless equipped by the Soviet Union. But theSoviet equipment was left out of the equation, andreports only said that the North did not have adequateresources for an invasion.To the <strong>Army</strong>’s credit, it always looks for lessonsin failure. In this case, Maj. Gen. Lyman L.Lemnitzer, then the Director of the Office of MilitaryAssistance, summed up those actions thatneeded to be taken to improve the intelligenceprocess. He said:I believe that there are lessons to be learnedfrom this situation which can point the way tobetter governmental operations and thus avoidcostly mistakes in the future.... I recommendthat...a clear-cut interagency standing operatingprocedure be established now to insurethat if (in the opinion of any intelligenceagency, particularly CIA) an attack, or othernoteworthy event, is impending it is made amatter of special handling, to insure that officialsvitally concerned...are promptly andpersonally informed thereof in order that appropriatemeasures may be taken. This willprevent a repetition of the Korean situationand will insure, if there has been vital intelligencedata pointing to an imminent attack, thatit will not be buried in a series of routine CIAintelligence reports.But intelligence was to fail again in Korea andin only four months. <strong>The</strong> war in Korea lookedlike it was rolling toward it conclusion. After theInchon landing, the Eighth U.S. <strong>Army</strong> in the west

and the X US Corps in the East were pushing thedecimated and demoralized North Korean <strong>Army</strong>in front of them, moving quickly toward the YaluRiver, North Korea’s border with China. On 25October 1950, U.S. patrols picked up an enemysoldier. He spoke neither Korean nor Japanese.Other prisoners followed. <strong>The</strong>y were interrogatedthoroughly, lie detectors being used on three ofthem. <strong>The</strong>y told stories about being part of largeChinese Communist armies that had crossed theYalu into Korea.Little reliance was placed on this intelligencebecause Eighth <strong>Army</strong> could find no other confirmationof large Chinese Communist Forces (CCF)formations in Korea. <strong>The</strong>y believed these Chinesewere fillers in North Korean units, helpingstiffen the defenses as UN forces approached theChinese border.29I Corps published an estimate at the end ofOctober which claimed, “<strong>The</strong>re are no indicationsat this time to confirm the existence of a CCF organizationor unit, of any size, on Korean soil.”30In late November, 96 Chinese “volunteers” hadbeen taken prisoner. <strong>The</strong>y identified six differentChinese Communist armies to which they belonged.Eighth <strong>Army</strong> was beginning to recognize theirpresence, however, and on 4 November notedthat two division-sized Chinese units were in Korea.It upped that estimate to three the next day,but was still underestimating the number of armiesnow on the peninsula. At this time Peiping radiowas broadcasting a communique declaring thatChina was threatened by the UN forces in Koreaand that the Chinese people should come to theaid of North Korea. On 5 November, the dailyintelligence summary made clear that the Chinesehad the capability to attack UN forces withoutwarning. At the Far East Command, Gen.MacArthur recognized that possibility as well. On6 November he issued a communique of his own,referring to the massing of troops at the borderas an act of “international lawlessness.” He continued,“Whether and to what extent these reserveswill be moved forward to reinforce units nowcommitted remains to be seen and is a matter ofthe gravest international significance.”31As more prisoners were taken the numbers ofChinese in the theater rose and by the third weekof November Eighth <strong>Army</strong> intelligence reportswere putting the figure at about 60,000. <strong>The</strong>Eighth <strong>Army</strong> G2, Lt. Col. James C. Tarkenton,believed that the Chinese units in Korea were notorganized CCF forces but volunteers and that“China would not enter the war.”32 On the eveof the resumption of the UN offensive on 24 November,estimates from the Department of the<strong>Army</strong>, FECOM, Eighth <strong>Army</strong> and X Corps allwere in agreement that there were as many as76,800 CCF troops in Korea, but seemed todownplay the possibility of a full Chinese intervention.Maj. Gen. Willoughby has been quotedas saying that the Chinese would keep out of theKorean War. MacArthur too seemed to sharethe opinion of his intelligence experts. As theUN offensive got underway on the 24th, the Commanderin Chief was declaring that little stood intheir way. He believed that the Chinese wouldnot enter the war in full force and, if they did, hisairpower would take care of them. Earlier, at themeeting with President Harry Truman at WakeIsland, on 15 October, the general was telling thepresident the same thing.33<strong>The</strong> CIA believed that the Chinese were interestedin only establishing a buffer zone along theirborder with North Korea. <strong>The</strong>y would changetheir mind by November 24, just before the Chinesebegan their major offensive, but their reestimatewas too late to have any effect on UNdefenses. <strong>The</strong> consensus in Washington and theFar East Command was that the communists wouldnot risk direct military action, relying instead onsubversion.Based on the historic record, rarely does thecollection effort fail to produce sufficient raw data.Only in the case of the Chinese intervention inKorea is the lack of information raised as a possiblesource of failure. MacArthur claimed afterthe Chinese intervention that he did not haveenough information upon which to base any reasonableintelligence analysis. He said that hisaerial recon planes were prohibited from crossingthe Yalu River where enemy troops could beconcentrated only a day’s march from his theater.Likewise, political intelligence regardingChinese intentions was hard to come by behindthe Iron Curtain. He said, “no intelligence systemin the world could have surmounted such

handicaps to determine to any substantial degreeenemy strength, movements and intentions.”34Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Omar Bradley,backed up that claim when he testified that“we had the intelligence that they were concentratingin Manchuria.... We had the informationthat they had the capability [to intervene].” Butthey didn’t know, according to Bradley, that theywould intervene.Failure to predict just when an attack will takeplace is common to most strategic surprise attackssince 1939.35 On 28 October 1950, after theChinese began infiltrating their forces into theKorean peninsula, U.S. intelligence believed that“with victorious U.S. Divisions in full deployment,it would appear that the auspicious time forintervention had long since passed.”36<strong>The</strong> reliability of the source came into play in1950 when the Indian ambassador to China, K.M.Panikkar, informed U.S. officials that the Chineseintended to intervene in Korea if the UNcrossed into the North. His impartiality was questionedbecause he was known to favor Chinesepolicies over those of the U.S.A belief in the superiority of one’s own militarycapabilities can often blind decision-makersto bold enemy moves. <strong>The</strong> very presence of thepowerful American fleet at Pearl Harbor wasthought to be a deterrent. Instead it was a target.Similarly, an overconfident MacArthur thoughtthat his airpower could take out any Chinesearmies attempting to interfere with his victory inKorea. “<strong>The</strong>re would be the greatest slaughter,”he predicted. As he said this, the Chinese werealready in the war in massive numbers.37In Kam’s analysis of surprise attacks from thevictim’s point of view, he assumed that the “intellectualprocess at the level of the individualanalyst...is consistently biased, and that this biasis the cornerstone of intelligence failures.”38Information about the enemy is interpreted in away that conforms to the personal beliefs andhypotheses of the analyst who will then resist anddismiss any information that contradicts his beliefs.At the same time, analysts will give too muchweight to evidence that support their conclusions.When aerial reconnaissance failed to find largebodies of Chinese troops in the northernmostreaches of Korea, that information dovetailedperfectly with the earlier conclusion that time forChinese intervention was past. It did not considerthat the aerial photos might not show smallgroups of the enemy well camouflaged duringdaylight hours. It is the challenge of professionalsto apply rigid tests to their conclusions andovercome the psychology of cultural bias.In hindsight, it becomes clear that the Chinesehad decided in early October to intervene in Koreaif the UN forces crossed the 38th parallel.Between 14 and 20 October, they moved fourarmies across the Yalu River, three of them infront of the Eighth <strong>Army</strong> and one in the X Corpssector. In the following week two more armiescrossed into Korea. By the end of October therewere 180,000 CCF troops in the peninsula. Beforethe UN offensive would begin, in the thirdweek in November, there were 300,000 Chinesesoldiers facing the UN.<strong>The</strong> Eighth U.S. <strong>Army</strong> had engaged Chineseforces, taken prisoners, and been informed ofChinese broadcasts that said they intended to interveneif the UN forces crossed the 38th parallel.<strong>The</strong> Air Force was providing photo reconmissions. Still they failed to correctly estimatethe number of Chinese, missing by more than 75percent, and ignoring the signals of intervention.Why?<strong>The</strong> Chinese used good operational security.<strong>The</strong>y had made good use of deception, using codenames for their units that made them to appear tobe small, token units. <strong>The</strong>y avoided detection byaerial observation by moving only at night andtheir daytime camouflage was excellent. An entiredivision marched 18 miles a day for 18 days,moving only at night over mountainous terrain.Roy Appleman described the march discipline thatkept aerial photography from uncovering theirpresence:...<strong>The</strong> day’s march began after dark at 1900and ended at 0300 the next morning. Defensemeasures against aircraft were to becompleted before 0530. Every man, animal,and piece of equipment were to be concealedand camouflaged. During daylight only bivouacscouting parties moved ahead to selectthe next day’s bivouac area. When CCF unitswere compelled for any reason to march byday, they were under standing orders for ev-

ery man to stop in his tracks and remain motionlessif aircraft appeared overhead. Officerswere empowered to shoot down immediatelyany man who violated this order.39Human intelligence, mainly reports from prisonersand Korean civilians, was ignored becausethey could not be confirmed by imagery intelligence.<strong>The</strong> Chinese avoided contact with Eighth<strong>Army</strong> units. U.S. authorities thought the Chinesebroadcasts were merely threats.In Korea, U.S. intelligence has been accusedof overemphasizing capabilities and neglectingintentions. After concluding that the North didnot have the capacity to launch a major offensive,some analysts convinced themselves that theenemy would not therefore launch such an ambitiousattack.When it comes to emphasizing intentions orcapabilities, there are two schools of thought. Onemaintains that the main concern should be enemycapabilities since these are more quantifiable, themethods more scientific, the results subject to onlypartial failure. To divine enemy intentions is adelphic enterprise that involves too much guessworkand can result in total failure and blame.<strong>Some</strong>times even the enemy does not know whathe is going to do. <strong>The</strong> other school has beenquoted as saying “the most difficult and most crucialelement in the intelligence craft lies in estimatingthe enemy’s intentions.”40Actually, the analyst must rely on both capabilitiesand intentions, since they cannot be isolated.This premise is recognized in the evolutionof U.S. <strong>Army</strong> doctrine. In 1951 the fieldmanual on Combat <strong>Intelligence</strong> cautioned commandersto “be certain they base their actions,dispositions, and plans upon estimates of enemycapabilities rather than upon estimates of enemyintentions.” Because analysts concluded in 1950that North Korea had no intention of achievingits goals by an all-out attack, it ignored NK capabilities.Consequently, no measures were takento strengthen or reinforce the South Koreanarmy.41 Later editions of the Operations fieldmanual called for the consideration of both enemyintentions along with capabilities. <strong>The</strong> 1976edition of FM 100-5 advised that “enemy intentionsmust be considered along with capabilitiesand probable actions.”42Seizure of the U.S.S. PuebloOn 23 January 1968, the U.S. electronic intelligenceship USS Pueblo was captured by NorthKorean patrol boats and two MiG jets, and its 83-man crew was taken prisoner. <strong>The</strong> ship was takenby surprise and Pueblo offered no resistance. Itwas boarded in international waters twenty-fivemiles from the Korean mainland and forced intothe North Korean port of Wonsan. It was thefirst American ship to be seized in 100 years. Thiswas two days after a 31-man team of North Koreanlieutenants was intercepted near the Republicof Korea presidential mansion on a mission toassassinate the ROK president, Park Chung-hee,and after a year that saw increasing North Koreaninfiltration across the Demilitarized Zone.43<strong>The</strong> intelligence failure in this instance was centeredaround the “risk assessment” for the Pueblomission. When the Navy headquarters assignedthe ship its collection task, it also evaluated thedangers associated with it. A sister ship, the USSBanner, had sailed on sixteen missions along thesame coasts. She had been harassed by both Chineseand Russian ships. But this had become anaccepted part of the game. So the mission proposalwas forwarded up the chain of commandwith a “minimal risk” label.Rear Admiral Frank L. Johnson, Commander,Naval Forces Japan (COMNAVFORJAPAN),agreed that the risk was minimal and sent the requestto Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet(CINCPACFLT) in Hawaii. One of the manyagencies there that had a piece of the action wasthe Current <strong>Intelligence</strong> Branch. <strong>The</strong> North Koreananalyst, Ensign Charles B. Hall, Jr., was newon the job. He went along with the minimal riskassessment. He was quoted as saying, “At thattime I did not see the North Koreans as a directthreat. I had no reservations because I franklydidn’t know enough about it to have any.”Hall’s superiors concurred as well. <strong>The</strong> assistantchief of staff for intelligence at CINCPACFLT,Captain John L. Marocchi, said, “<strong>The</strong>se evaluationswere in no sense rubber stamps. <strong>The</strong> NorthKoreans were pushing bodies across the DMZ.<strong>The</strong>y continued to seize South Korean ships andaccuse them of being spy boats. What we saw

and heard didn’t seem any different from whatwe had been seeing and hearing for the past tenyears. <strong>The</strong> Koreans, up to that point, had donenothing to our ships, while the Russians had harassedthem. <strong>The</strong> mission looked like it would bequiet and safe. <strong>The</strong> logic was in the message. Ittook me about as long to approve it as it did toread it.” <strong>The</strong> proposal worked its way throughsucceeding headquarters. From Commander inChief Pacific (CINCPAC) it went to the Defense<strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency where it was bundled withseveral dozen other proposals into 14 to 16 inchesof dense paperwork. An overworked staff officerdid not have time to ask any questions andhe also approved it.So the mission was launched as planned as aminimal risk with no air support, no escort, andthe Pueblo’s pair of inadequate .50 caliber machineguns useless under frozen tarpaulins. <strong>The</strong>mission was based on a fatal presumption expressedby Captain George L. Cassell, assistantchief of staff for operations at CINCPACFLT, whothought “It didn’t follow that these people [theNorth Koreans], although they were attacking ourpeople across the DMZ, would do anything acrossthe water.”44Tet OffensiveIt was a lousy year for intelligence coups. As1968 began, a message to the Defense <strong>Intelligence</strong>Agency from the National Security Agency, alertingthem to the possibility that the North Koreansmight seize the US intelligence ship Pueblo wasmisplaced on a clipboard and lost. It was locatedthree weeks later. Later in the year, after buildingup their troops for seven weeks on the border,the Soviet’s invaded Czechoslovakia, takingthe U.S. by surprise. <strong>The</strong>n there was the Tet Offensivein Vietnam.During the Tet holiday in Vietnam, a time oftraditional ceasefires during the war, on 31 January1968, the Communist forces launched a majorsurprise offensive, attacking cities, militaryand government targets throughout the country.Simultaneous armed insurrection by South Vietnamesecitizens was a key part of the Communiststrategy. If this succeeded, tens of thousands ofthe southern populace would be added to theirnumbers. But it failed to materialize. As a diversion,the North aimed thrusts along the borderwith South Vietnam, especially the U.S. firebaseat Khe Sanh. <strong>The</strong>se attacks successfully divertedthe allies attention away from their planned Tetattacks nationwide, but at the same time strainedtheir resources.Documents captured in November 1967 includedan order to the People’s <strong>Army</strong> which read:“Use very strong military attacks in coordinationwith the uprisings of the local population to takeover towns and cities. Troops should flood thelowlands. <strong>The</strong>y should move toward liberatingthe capital city.”45Concentrated attacks on U.S. facilities at DaNang, Tan Son Nhut, Bien Hoa Air Base, and thelogistical complex at Long Binh, caused initialconfusion but were eventually thrown back byquickly responding American combat units. <strong>The</strong>bloody battle at Hue where U.S. Marines weredesperately engaged and the attacks on governmentoffices in Saigon, most dramatically the U.S.Embassy, came as shocks to the already anxiousAmerican psyche. <strong>The</strong>re seemed to be fightingand destruction everywhere. Television setsthroughout the United States magnified this perception.But the allies rallied to stymie the enemy.American firepower was brought to bear.By 21 February, the Communists were withdrawingeverywhere but Hue where they would holdout until the 24th when the Imperial Palace wasrecaptured.<strong>The</strong>re were 4,000 Americans killed orwounded, and between 4,000 and 8,000 casualtiesfor the ARVN. <strong>The</strong> Communists lost between40,000 and 50,000 killed in action. <strong>The</strong>ir VietCong infrastructure was destroyed. Ironically,Tet was the biggest victory the allies ever gainedover the Communists during the war, but it wasnot recognized as such at the time. Instead, Tetwas seen by American political leadership andthe American people at large as proof that wewere not winning in Vietnam and could be surprisedand hurt by an offensive by an enemy thatmost military intelligence experts were countingout.<strong>The</strong> Tet Offensive was a turning point in thewar. It produced a staggering recoil in the Americanconsciousness. It was a blow to the political

will on the homefront from which it would neverrecover. From that point on the U.S. policiesshifted toward a reduction of U.S. involvementin the war. President Lyndon Johnson decided afew months later not to seek reelection. Tet wasimmensely successful and owed its success to itssurprise. This was a result that was not foreseenby the planners of Tet. North Vietnamese GeneralTran Do said after the war, “We did notachieve our main objective.... As for making animpact in the United States, it had not been ourintention—but it turned out to be a fortunate result.”46One of the reasons U.S. analysts were surprisedwas the overreach and irrationality of theenemy plan, as it was based on the faulty assumptionthat the South’s citizens would seize this opportunityto join with the Communists to overthrowtheir government.Collection did not fail before Tet. <strong>The</strong> allieshad a captured order for the attack, tape-recordeddiscussions taken off agents at Qui Nhon, prisonerinterrogations, the unprecedented numberof high priority messages that were interceptedby SIGINT pointing to the attack, and the strongevidence provided by premature attacks in I andII Corps Tactical Zones.Ephraim Kam assigns three levels of reliabilityto intelligence information: Nonreliable or partlyreliable, reliable but controlled [enemy knows weknow and can change plans], and reliablenoncontrolled [evidence that enemy does not knowwe know]. <strong>The</strong> attack order intercepted severalweeks before the Tet offensive was deemed asunreliable because it was written by someoneoutside the highest levels of the Communist leadership,because it was not specific as to the dateof the attack, and because it was then easily mistakenfor propaganda.47<strong>The</strong>re were at least four accurate reports ofenemy intentions. General Phillip Davidson,Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV)Assistant Chief of Staff for <strong>Intelligence</strong> (J-2),briefed General Westmoreland on 13 January thatattacks against Saigon were imminent andWestmoreland responded by strengthening thecity, a move that probably prevented its completeoccupation. But allied attention was drawn to thenorth by the enemy threat at Khe Sanh. On themorning before the attack, General Davidson predictedthat the precipitate attacks against the citiesin I and II Corps foreshadowed similar attacksthroughout the country within 24 hours.Westmoreland heeded this warning but it wastoo late to take any real action to change any defensivedispositions. (<strong>The</strong> warning itself did notseem extraordinary to most commanders whowere used to receiving everyday information fromMACV headquarters over the telephone. Sincethe troops were on alert as often as they were offalert, this one issued at 1125 hours on 30 Januaryseemed not at all unusual.) <strong>The</strong> North Vietnamesehad achieved surprise.Because U.S. intelligence analysts did not correctlyput together all the pieces of the puzzle untilhours before the Tet offensive, too late to make adifference, they are credited with an intelligencefailure.James Wirtz analyzes that failure of intelligenceanalysis in light of six empirical questions. “Werethe Americans surprised because they failed to:(1) identify the adversary; (2) estimate the probabilityof attack; (3) determine the type of actioninvolved; (4) identify the location of the attack;(5) predict the timing of the attack; and (6) determinethe motivation behind the initiative?”48Because it was wartime, the question of identifyingthe adversary becomes moot. When at war,it is also likely that an attack will take place, soanalysts assumed that a major offensive was to beexpected. And the type of action involved wasalso easy to figure since the North had no assetsto launch an air, amphibious, naval, airborne ornuclear attack. <strong>The</strong> attack would be undertakenby ground forces. So the clues to the analysisfailure lay in the where, when and why.U.S. leaders had two choices as to where theenemy blow would fall—urban areas or along theDMZ. <strong>The</strong>y chose the DMZ because, amongother reasons, it coincided with their analogies toDien Bien Phu. U.S. commanders were also moreinclined to see their troops as the biggest threat tothe enemy and to protect their own forces. Becausethey were dug in around Khe Sanh and wellprepared, they would have preferred the attackto strike there. <strong>The</strong>se beliefs were reinforced bySIGINT that indicated a massing of NVA troopsalong the borders.49 So the predispositions of

U.S. leaders caused them to mistake the diversionfor the main attack and the main attack forthe diversion.<strong>The</strong> tendency of U.S. analysts to think in termsof U.S. troops rather than their ARVN allies contributedto the failure to consider the Tet holidays,a time when half of the ARVN soldiers would beon leave, as being an especially opportune timefor an enemy attack in ARVN areas of responsibility.<strong>The</strong>y believed that the South Vietnamesearmy was protected by the American shield alongthe DMZ. In the past, the North had taken advantagesof truces to resupply and build up theirforces. Americans believed the attack would fallsometime after the truce.<strong>The</strong> motivation for the Communist offensive,the why of the equation, was, more than anythingelse, to try and reverse their declining combatreadiness and morale. U.S. analysts rightly sawsuch a possible enemy move as a desperate lastditch effort, not unlike the Germans offensiveduring the Battle of the Bulge. <strong>The</strong>y did not recognizea further objective of Communists—thatof playing upon U.S. strengths to deceive themand pouncing upon the vulnerable ARVN unitsto destroy them.More than a few historians have suggested thatAmerican <strong>Army</strong> intelligence specialists producedreports that would confirm the views of their leadersand the Johnson administration that the enemywas just about finished.Wirtz offers this insightful analysis of Tet:<strong>The</strong> story of the intelligence failure alsohighlights the herculean task faced by officers,analysts, and policy makers as theystrove to complete the intelligence cycle.Remarkably, the Americans almost succeededin anticipating their opponents’moves in time to avoid the military consequencesof surprise, despite their underestimationof the weakness in their alliance,the resourcefulness of their opponents,and the handicaps they faced incompleting the intelligence cycle. But twofactors ultimately slowed them in their raceto predict the future: <strong>The</strong> influence ofbeliefs that could no longer account forevents and their inability to anticipate themistakes made by their opponents. <strong>The</strong>failure to anticipate an attack in wartime,when Americans could have assumed thattheir opponents would do everything intheir power to hurt the allies, testifies tothe difficulty inherent in avoiding failuresof intelligence.50Raid on Son TayIn a daring raid on 20 November 1970, a 59-man assault force of elite soldiers, led by Col.Arthur D. “Bull” Simon, hit a small compoundjust 23 miles from Hanoi. It was the Son Tayprison camp that was thought to hold 61 Americanprisoners of war. Months of planning andrehearsal paid off as the team flawlessly were airliftedto their objective, executed their mission,overwhelmed all their opposition, and escapedwithout a single American casualty. <strong>The</strong>re wasonly one problem. <strong>The</strong>y brought out no prisoners.<strong>The</strong> camp was empty. When the newsreached the war room in Washington, D.C. thatthe prison camp was empty, General William C.Westmoreland, then <strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff, exploded“Another intelligence failure!”51 52Son Tay intelligence depended largely on photorecon from SR-71s, RF4s, RF101s, and unmannedBuffalo Hunter drones. Six drone flightswere either shot down or malfunctioned. <strong>The</strong> lastand seventh drone mission, after the camp wasevacuated, was to take shots from treetop level,but the aircraft banked as the shutter was triggered,producing only a photo of the horizon.SR-71 missions were hampered by cloud and dustcover. Agents were also inserted but with negligibleresults.<strong>The</strong> prisoners had been moved four and onehalfmonths before the raid because of flooding.Speculation centered around whether the floodinghad been caused by a covert cloud-seedingoperation designed to wash away resupply trailsin Laos that was so secret that even the plannersof the Son Tay raid could not be informed.53An usually reliable foreign intelligence sourceprovided information that the camp was emptyand that information reached decision makers inWashington just hours before the final missionlaunch. When asked for an unequivocal answeron whether U.S. prisoners were in Son Tay or

not, <strong>Army</strong> Lt. Gen. Donald Bennett, commandingthe Defense <strong>Intelligence</strong> Agency, held out ahandful of messages and photos and said, “I’vegot this much that says ‘<strong>The</strong>y’ve been moved.’”<strong>The</strong>n he extended the other hand which held athick folder and added, “And I’ve got this muchthat says “<strong>The</strong>y’re still there.’”54Defense Secretary Melvin Laird told the presidenton 20 November that the prisoners had beenmoved from Son Tay but that the camp had recentlybeen reoccupied by unknown parties.Laird recommended the raid be given the goahead. <strong>The</strong> president concurred.55<strong>The</strong> Son Tay raid had the top priority for electronicintelligence coverage and ELINT was good.It had the North Vietnamese air defense systemwired. But the delivery of the product was timeconsumingand there was little time at the lastminute to revise information. Because of equipmentfailures or delivery problems, the latestphoto imagery taken before the raid could not beexamined until the operation had been launched.<strong>The</strong> overall commander of the raid, Air ForceBrig. Gen. Leroy J. Manor couldn’t get crucialweather information at the last minute because helacked the proper clearances.56When reporters queried Simons at a press conferenceabout who was to blame for the intelligencefailure, the colonel replied, “I can’t answerthat question at all. I am not sure what you meanby ‘intelligence failure.’”57Before Senate hearings on the failed raid, Secretaryof Defense Melvin Laird testified, “we havemade tremendous progress as far as intelligenceis concerned.” <strong>The</strong> hearing room erupted inlaughter. Laird went on to say, “We have notbeen able to develop a camera that sees throughthe roofs of buildings. [Otherwise] the intelligencefor their mission was excellent.” But since themission failed to bring home any prisoners, fewsaw that as being relevant.58<strong>The</strong>re are a lot of ways for intelligence to fail,and things usually go wrong in combination.<strong>The</strong>re are many critical nodes in the process.Likewise, there are many blocks in the minds ofthe evaluators. <strong>The</strong>re are errors in process. <strong>The</strong>recan be too little data resulting from the omissionto target a given area. <strong>The</strong>re can be too muchinformation, sometimes caused by enemy misinformation,that clogs the channels and slows theflow. In these cases it becomes important to assignthe correct priority. <strong>The</strong>re can be conflictingdata. Often the reliability of the sources comesinto question. <strong>The</strong>re can be a misreading of theurgency of the data. Human inaction quite oftencomes into play, like the lieutenant commanderwho told the excited clerk that the translation ofthe Japanese message that gave important indicatorsof the Sunday attack on Pearl Harbor couldwait until Monday. <strong>The</strong> repetitious occurrenceof indicators can cause the “crying wolf” syndromewhich causes evaluators to discount signsthat have taken on the appearance of the commonplace.<strong>The</strong>n, there is the pinching off of theinformation to the decision makers by overzealousexecutive officers or chiefs of staff who wishto protect their boss from adverse information.<strong>The</strong>re are errors in judgment. Rarely do militaryintelligence professionals err on the side ofenemy capabilities. <strong>The</strong> numbers are usuallyright, or carefully qualified. If they are wrong, itis usually an overestimate resulting from caution.It is in the area of enemy intentions that the possibilityof error multiplies. Here we enter thatcloudy realm of wishful thinking. We need tounderstand, as historians and intelligence officers,the psychology of the human response to informationthat shapes the decision process. <strong>The</strong>policy makers inevitably sift the information thatthey receive through the filter of their own preconceptions.People will believe what they have been conditionedto believe, predicting the future basedupon their own vision of it. <strong>The</strong>y see happeningwhat they want to happen, but the course of thefuture is never so accommodating. Harry Trumanwas unwilling to believe that the North Koreanswould do anything as irrational as cross that linethat western diplomats had so conscientiously andsagely drawn. Stubborn adherence to false assumptionsis a failing that is common to all of us.<strong>The</strong> analyst never acts alone. He is always partof an organization with its own values, expectations,biases, pressures to conform, and politicalmotivations. He works in an environment thatdoes not always reward dissent, discrepant information,or uncertainty.When dissenting views come from junior of-

ficers, they are often suppressed or just ignoredby those in higher positions. When CommanderArthur McCollum, Chief of the Far Eastern Sectionof Naval <strong>Intelligence</strong>, prepared a messagealerting the Pacific fleets, based on what he sawas imminent dangers, he was denied permissionto do so by four senior admirals who thought thatsufficient warnings had already been sent.59Dissenters can also be senior officials as wasthe case with Admiral Richmond Turner, the Chiefof War Plans in the Navy Department, who believedthat Hawaii would be attacked. GeorgeKennan, a State Department Soviet expert, recognizedthe true reaction of the Chinese to thecrossing of the 38th parallel by UN forces, butwas not given a hearing by Secretary of State DeanAcheson.60<strong>The</strong> intelligence analyst works within an organization,often a military one, and institutionsthemselves are subject to inherent inefficiencieslike bureaucracy, compartmentalization, security,faulty communication or rivalry between agenciesor services.Group dynamics, or “Groupthink,”61 can alsoaffect the decision-making process as it is hard toresist the conclusions of a group of peers. Butthe group need not be small, or a selected cliqueof leaders. It can be as large as the entire Americansociety, a peace-loving group that does notreadily accept the possibility of war. An exampleof “groupthink” is seen in President Kennedy’sinner council of advisors prior to the Bay of Pigsinvasion. <strong>The</strong>re are few people who would challengea president’s or general’s decision.Intel analysts are sometimes overwhelmed bytrivial detail, daily workload, unrealistic expectations,and pressures to be politically correct. Itis difficult to sift the relevant from the noise priorto an event. It is understandable that analystswants to evaluate every scrap of information thatcomes their way, any clue that might help themreach correct conclusions.If the military leader is not warned in time, thereis little difference from not being warned at all.Because it would have taken almost three weeksto reinforce the Republic of Korea with U.S.forces from Japan, General MacArthur concludedthat even a 72-hour warning of an attack wouldhave mattered little to the outcome.<strong>Some</strong> failures to provide sufficient warning ofan attack can be chalked up to bad luck. A messagefrom <strong>Army</strong> Chief of Staff George Marshallcould not get through to <strong>Army</strong> headquarters inHawaii because no one was on duty that Sundaymorning. General Marshall had neglected to markthe message urgent so when it did reach Honoluluvia Western Union it was too late. A motorbikemessenger was delivering the telegram whenthe bombs started to fall. Many portentous messagesintercepted by Magic were simply not translatedin time.In reviewing some of those too many instanceswhere intelligence has failed, we come to someobvious realizations. One is that science can beof little help when dealing with the often irrationaland unpredictable human mind.62 It is littlewonder that many of the invaders of our centuryhave been called “madmen.” Logic has its limitsin plumbing the waters of the human soul. If intelligenceanalysis is then as much an art as it is ascience, future failures are inevitable. That is notto say that we can’t improve upon the odds ofsuccess by adding to our understanding both ofthe process of intelligence analysis and of thehuman behavior.I have summarized in a Table some of the obviousconclusions that come to mind after reviewingthose historic examples of intelligence failures.It is an imperfect list and readers are invitedto draw some of their own lessons and offersome of their own remedies. One thing becomesapparent. <strong>The</strong> key to guarding against intelligencedeficiencies lies in the area of education. Manyof the problems with communication and disseminationhave already been fixed by procedural reformsand reorganizations. Problems residing inthe human psyche can only be addressed by trainingthat works at changing attitudes and judgmentalweaknesses.One can readily see how important educationis to bringing about change and solutions. It is adaunting responsibility for <strong>Army</strong> schools. If thereis going to be an improvement in intelligencework, there must be a corresponding movementwithin <strong>Army</strong> education to encourage openmindedness,imaginative new approaches toanalysis, the encouragement of dissenting opinions,interservice cooperation, and leadership at-

titudes. This can be accomplished in basic, advancedand pre-command courses.It would also be useful to inculcate throughtraining a higher tolerance to false alarms. Admittedlythis would mean a willingness to accepthigher costs in both dollars and up-time, but itwould have the benefit of avoiding surprise attacksand perhaps convince an enemy of our preparedness.It is thought that many of the problems of thepast have been overcome by technology. Computershandle and track the masses of information.Mathematical models compile indicators andidentify possible crises. Satellites relay voice andpictures in near real time. <strong>The</strong> President of theUnited States and the Joint Chiefs of Staff canwatch televised battlefield damage assessmentsminutes after an attack. <strong>The</strong> decision-makers havenever had so much information to aid them soquickly.While machines serve us well in gathering andquantifying the more voluminous and complexinformation in today’s world, we will still be leftwith the human fallibilities in analyses and response.<strong>The</strong> recognition of this fact is the firststep toward understanding the process. <strong>The</strong> nextstep is understanding where deficiencies are likelyto occur in the system. And finally, for thoseconcerned with training the intelligence specialistsand for the students themselves, the last stepis to resolve that no intel failure should ever bethe result of a lack of skill on the part of the intelligencespecialist.1. Jeffery, Keith, “<strong>Intelligence</strong> and Military History: ABritish Perspective,” in Charters, David A., Milner, Marc,and Wilson, J. Brent, editors, Military History and theMilitary Profession, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut, 1992.2. Funston’s Annual Report, 1916.3. Wohlstetter, Roberta, Pearl Harbor, Warning and Decision,Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1962, p.385.4. Wohlstetter, p. 387.5. Roberta Wohlstetter defines “Signals” as signs or indications.“Noise” is competing and conflicting signs, ordisinformation. Most signals are read against a background ofnoise. It is easier to know which are signals and which arenoise after the disaster.6. Wohlsetter, p. 387.7. Kam, Ephraim, Surprise Attack: <strong>The</strong> Victim’s Perspective,Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1988, p. 75.8. U.S. Congress, Senate. 1946, Report of the Joint Committeeon the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, 79th Cong., 2dsession, Washington, D.C., pp. 65, 102, 105, 126.9. Kam, pp. 47-8.10. Wohlstetter, pp. 389-90.11. U.S. Congress, p. 258.12. Wohlstetter, p. 312.13. Wohlstetter, pp. 388-90.14. Quoted in Kam, p. 102.15. Wohlstetter, pp. 397-8.16. Wohlstetter, p. 401.17. Kam, p. 49.18. Hunter, Col. W. Hamilton, Chairman, et al, “Study of thePearl Harbor Hearings,” War Department, General Staff, 23January 1947.19. Knorr, Klaus, and Patrick Morgan, eds., Strategic MilitarySurprise, Transaction Books, New Brunswick, NJ, 1983, 80.20. Ibid., p. 81.21. Ibid., p. 82.22. Schnabel, James F., Policy and Direction: <strong>The</strong> First Year,Center of Military History, Department of the <strong>Army</strong>, GovernmentPrinting Office, 1992, p. 63.23. Ibid., p. 63.24. Ibid., p. 63.25. Ibid., p. 63-4.26. Ibid., p. 64.27. Ibid., p. 62.28. Ridgway, Matthew, 1967, p. 14.29. Appleman, Roy E., South to the Naktong, North to theYalu, Center of Military History, Department of the <strong>Army</strong>,Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1992, p. 752.30. Ibid., p. 753.31. Ibid., p. 762.32. Ibid., p. 755.33. Ibid., p. 760-3.34. DeWeerd, H.A., “Strategic Surprise in the Korean War,”Orbis, 6, Fall 1962, pp. 450-1.35. Kam, p. 14.36. Ibid., p. 15.37. Ibid., pp. 80-1.38. Ibid., p. 85.39. Appleman, p. 770.40. Quoted in Kam, p. 57.41. Quoted in Kam, p. 59.42. Kam, p. 59.43. Finley, James P., <strong>The</strong> U.S. Military Experience in Korea,1871-1982, Command Historian’s Office, Secretary Joint Staff,Headquarters, U.S. Forces Korea/Eighth U.S. <strong>Army</strong>, APO SanFrancisco 96301, 1983.44. Armbrister, Trevor, A Matter of Accountability: <strong>The</strong> TrueStory of the Pueblo Affair, Coward-McCann, New York, 1970,p. 189-90.45. Arnold, James R., Tet Offensive 1968: Turning Point inVietnam, Osprey Publishing Ltd, London, 1990, p. 36.46. Ibid., p. 86.47. Kam, pp. 39, 41-2.48. Wirtz, James, <strong>The</strong> Tet Offensive: <strong>Intelligence</strong> Failure inWar, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 1991. 49.James Wirtz makes the point that U.S. analysts have a weaknessfor SIGINT over other less reliable sources of intelligence and

thus fall victim to what he calls the Ultra syndrome (p. 274).50. Wirtz, p. 275.51. Schemmer, Benjamin F., <strong>The</strong> Raid, Harper and Row, NewYork, 1976, p. 182.52. Time was squandered in selling the idea to the military andpolitical hierarchy. <strong>The</strong> raid at Son Tay contrasted with theIsraelis raid on Entebbe on 4 July 1976 which successfullyrescued hostages. <strong>The</strong> difference is in operational realm, not inintelligence.53. Schemmer, p. 81.54. Ibid., p. 147.55. Ibid., p. 148.56. Ibid., p. 151.57. Ibid., p. 189.58. Ibid., p. 192.59. Kam, p. 161.60. Ibid., p. 162.61. Irving Janis defines groupthink as “a mode of thinking thatpeople engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesivein-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity overridetheir motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses ofaction.” <strong>The</strong> condition can be recognized by these symptoms:—An illusion of invulnerability...which creates excessiveoptimism and encourages taking extreme risks;—Collective efforts to rationalize in order to discount warningswhich might lead the members to reconsider their assumptions...;—Stereotyped views of enemy leaders...as too weak andstupid to counter whatever risky attempts are made to defeattheir purposes;—Direct pressure on any member who expresses strongarguments against any of the group’s stereotypes, illusions,or commitments....Janis uses the example of Pearl Harbor to show how hard itwas to confront a strong leader with dissenting views:During the week before the attack it would have been doublydifficult for any of Kimmel’s advisers to voice misgivingsto other members of the group. It was not simply amatter of taking the risk of being scorned for deviatingfrom the seemingly universal consensus by questioning thecherished invulnerability myth. An even greater risk wouldbe the disdain the dissident might encounter from his colleaguesfor questioning the wisdom of the group’s priordecisions. For a member of the Navy group to becomealarmed by the last-minute warning signals and to wonderaloud whether a partial alert was sufficient would be tantamountto asserting that the group all along had been makingwrong judgments. Victims of Groupthink, Houghton-Mifflin, Boston, 1972, pp. 9, 197-8.62. Irrationality on the part of the enemy is often the reasonanalysts give for failing to predict surprise attacks. <strong>The</strong> enemycannot succeed in such an endeavor so it won’t risk it, goes thereasoning. And the reasoning does not appear to be flawed. Inthe eleven surprise attacks since 1939, only twice have the attackersachieved victory.