Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

Staffrider Vol.3 No.1 Feb 1980 - DISA

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

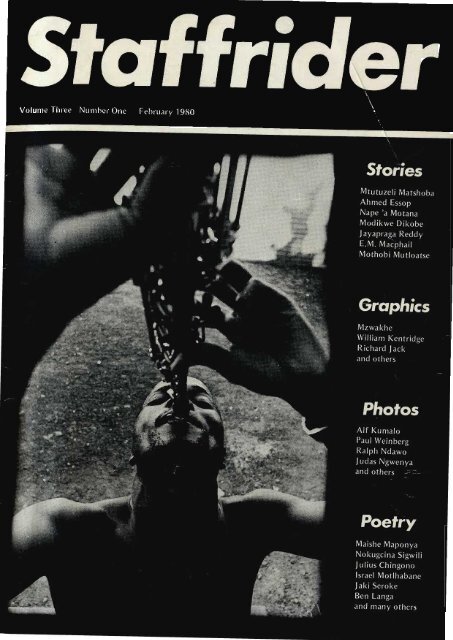

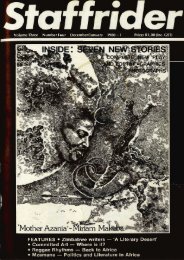

Volume Three Number One <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>1980</strong>StoriesMtutuzeli MatshobaAhmed EssopNape 'a MotanaModikwe DikobeJayapraga ReddyE.M. MacphailMothobi MutloatseIII iiiiiOMMSA•GraphicsMzwakheWilliam KentridgeRichard Jackand othersPhotosAlf KumaloPaul WeinbergRalph NdawoJudas Ngwenyaand others ^~ ~iiiiiiPoetry*'#^'„ill!Maishe MaponyaNokugcina SigwiliJulius ChingonoIsrael MotlhabaneJaki SerokeBen Langaand many others

COMING SOON FROM RAVAN PRESS...§}fM(3© §®Qfl£[j08©°>Dn(^[]QO[p®owywtfMmliiiliiTWENTY-FIVE STORIES, COLUMNS AND MESSAGES BY CONTEMPORARYBLACK SOUTHERN AFRICAN WRITERS EDITED BY MOTHOBI MUTLOATSEAND FEATURING GRAPHICS BY NKOANA MOYAGA AND FIKILE. A MAJOREVENT IN SOUTH AFRICAN PUBLISHING HISTORY - DONT MISS IT!<strong>Staffrider</strong> Series Number three<strong>Staffrider</strong> magazine is published by Ravan Press, P.O. Box 31134, Braamfontein 2017, South Africa. (Street address: 409 Dunwell, 35 JorissenStreet, Braamfontein.) Copyright is held by the individual contributors of all material, including all graphic material, published in the magazine.Anyone wishing to reproduce material from the magazine in any form should approach the individual contributors c/o the publishers.This issue was printed by ABC Press (Pty) Ltd., Cape Town.

Vol. 3 <strong>No.1</strong> Contents <strong>Feb</strong>ruary <strong>1980</strong>StoriesTo Kill a Man's Pride by Mtutuzeli Matshoba 4The Poet in Love by Nape 'a Motana 14The Slumbering Spirit by Jayapraga Reddy 20Two Dimensional by Ahmed Essop 40Saturday Afternoon by E.M. Macphail 45GroupsZAMANI ARTS ASSOCIATION, Dobsonville 8ALLAHPOETS, Soweto 9CYA, Diepkloof 9eSKOM ARTS, Soweto 12PEYARTA, Port Elizabeth 23GUYO BOOK CLUB, Sibasa 26MADI GROUP, Katlehong 27MALOPOETS, Durban 28ABANGANI OPEN SCHOOL, Durban 29PoetryThemba Mabele, Nhlanhla Maake, Dipuo Moerane .... 8Maishe Maponya, M. Ledwaba, Mabuse A. Letlhage .... 8Makgale J. Mahopo, James Twala, Themba kaMiya ... 10Martin Taylor, Patrick Taylor 11Richie Levin, Peter Stewart, Kelwyn Sole 16Zanemvula Mda, Julius Chingono, S.M. Tlali 17Paul Benjamin 22Fezile Sikhumbuzo Tshume, Charles Xola Mbikwana,Mandi Williams, Nkos'omzi Ngcukana 23Nthambeleni Phalanndwa, Tshilidzi ShonisaniRamovha, Maano Dzeani Tuwani, Jaki Seroke 26Matime Papane, Mohale J. Mateta,Motlase Mogotsi, Maupa-Kadiaka 27Ben Langa 28S.Z. Kunene, Senzo Malinga, V.J. Mchunu 29Israel Motlabane 39Nokugcina Sigwili 44Gallery/ GraphicsColumns/ FeaturesVOICES FROM THE GHETTOKwa Mashu Speaking 2PROFILEStar Cafe: Modikwe Dikobe 7NGWANA WA AZANIAA film concept by Mothobi Mutloatse 12Mzwakhe 4, 28, 37, 39Richard Jack 15P.C.P. Malumise 17Mike van Niekerk 20, 21William Kentridge 24Mpikayipheli 30, 3 3, 35Renee Engelbrecht 40Hamilton Budaza 45Goodman Mabote 46GALLERY PROFILEBehind the Lens: Judas Ngwenya 18DRAMA SECTIONChief Memwe IVPart one by Albert G.T.K. Malikongwa 30REVIEWMafika Gwala reviews Just a LittleStretch of Road and The Rainmaker 43WOMEN WRITERSNokugcina Sigwili 44CHILDREN'S SECTIONChildren of Crossroads 46PEN NEWS 47EGOLI, Scenes from the play 48PhotographsGrace Roome 3Paul Weinberg 7,25,Judas Ngwenya 9, 18, 19Biddy Crewe 11, 44Ralph Ndawo, Brett Hilton Barber,David Scannel, Leonard Maseko 12, 13Chester Maharaj 48Cover Photographs:Front: Abe Cindi by Alf KumaloBack: Kliptown, 1979 by Paul Weinberg

VOICES FROMTHE GHETTO:Kwa Mashu SpeakingSpeaking: Mrs M. of Kwa Mashu, born in 1926 in the Districtof Umbumbulu, Natal South Coast, interviewed in July 1979by A. Manson and D. Collins of the Killie Campbell AfricanaLibrary Oral History Programme.FROM CATO MANOR TO KWA MASHUIn 1950 I married and went to stay in Cato Manor . . .In 1959 they started sending us to places like Kwa Mashuand Umlazi. Most people started to run away at that time,some to Inanda, others to a place somewhere at Isipingowhich was called, translated into English, "when you see apoliceman, you have to run, and then when the policeman isgone you come back and do what you like and build yourhome."iLIFE AT CATO MANORIn Cato Manor the laws were very flexible. My husbandand I were running a shack shop. Though we were workingin town, we would come home to do the shop. We wereforever being arrested, but I can see now that we were moreunited there than we have ever been here (Kwa Mashu.)I stayed in Cato Manor for many years, and I can assureyou — we always discuss these things — that if today theywere to say yes, we would go back, even though it was aslum.It must be remembered that, before, it was a slum*with nosite and service. You know that. Well, the life was very free,people were very co-operative with one another. Youcouldn't come and kill somebody for nothing. We used to seethat there was something happening that side. We'd all rushto go and help that somebody. We'd be beating the ... It wasjust like that, honestly. I used to hear people who had neverbeen to Cato Manor say, "Hau. Were you at Cato Manor?"Because today, believe me, I don't go about here at KwaMashu in the evening, because my life would be gone. Yousee. So myself, I don't see anything good here in these townships.There — I'm talking as if — because Cato Manor wasjust a homely place, you know. In those slums, squatters'camps as you call them now, we had that spirit of humourfrom one another. Here, I discover that people in these fourroomeds— I don't know whether they are polluted by them— they don't know their neighbours. Honestly, I don't knowmy neighbours but I'm here, you can just imagine, from1959! Nobody cares for anyone here, and even if a person iscrying — my dogs are doing a lot of work sometimes. Whensomebody cries (imitation of a scream) — tsotsis, you know,pickpocketing, slaughtering someone, I have to release mydogs. Otherwise the life here . . . myself, I say that in CatoManor we were much better, because of unity which I thinkis very important. Here, honestly, nobody cares for any otherperson.For me, I don't like it, that is not the spirit of we Africans.I don't know whether it is because I was born onthe farm where that spirit is existing, you know, to careabout the person on the other side, is he happy and if not,what happened there. We used even to hear the bell ringing.There are some signs that people use on the farm. If that bellrings and then stops, and then rings and then stops, oh, weknow that there was somebody who had passed away.Definitely: if I was ploughing or whatever I was doing, we'dleave that straight away. And then we'd have to go and ask"Who is dead? Somebody has passed away. Did you hear thatbell ringing from the church?" It was a sign telling the peoplethat somebody had passed away. Here, it is most appalling tome, seeing a coffin passing. They don't care what it is. So Idon't think life here in the townships is as good, ja.What kind of social activities did you have at Cato Manor?In Catq Manor people used to, we used to . . . There waspolitics, in the first place. There was too much of ANC inthose days, but those people were very much united, honestly.We used to hear a sound which told us that there wassomething wrong. We'd have to touch one another, that,now, something's happening, what's happening now? Andthen, there, we used to gather. That was politics, of course.Then, in the line of the welfare: people, as I say, werebrewing gavine, shimiyana, everything. They were very rich,compared to -the people here in the township. We used toorganize ourselves to help those children who came fromvery poor people, to serve them with some milk, you know,just to end this kwashiokor in the township. And we used toparticipate — there were schools there. We used to gather aswomen to discuss our problems. That was when the DurbanCorporation started to give us site and service. Becausebefore, as you know, there was nothing like latrines or wateror anything. You used to go there to the Umkumbane —washing, drinking, all those things. Our children were gettingdiarrhorea a lot. Through those meetings of ours, I think, theDurban City Councillors got the idea of this site and service,and gave us some plans. It was L, U, you know, then youbuild your own. But they were nicely built because there wasthis plan which we were given, free of charge, by the DurbanCity Councillors. This is why I always ask why don't theydo it to these people that are on next-door Richmond Farmand Inanda, in those squatters' camps, you know, becausepeople will build in a better way if they are given thatprivilege, and given site and service. They may not buildbeautiful houses, but a simple, nice good pattern with a siteand service, you know. These are important things becausethe population explosion is here.THE SHACK SHOPSWhich area did you live in? Did you live in any specificarea in Cato Manor like Shumville?We started in a place called Mangaroo. Then from MangarooI went up to Newlook. Newlook. That was the name ofthe shack shop I was running at Umkumbane. It was less thanthis (indicating the room). It was just an open four-walls withno ceiling.You must remember Cato Manor was owned by Indiansbefore. I think that an Indian merchant had been trying tobuild a shop. Then there were those riots and the peoplekilled those — they were killing everybody, burning everything.So those four walls were just left unfinished, with noroof inside. That was in Newlook. So my husband had tomove there. Nobody had to tell us, we just moved, youknow.And then Bourquin* was too clever. There were some bigIndian shops there. He said, 'Oh, no, you people, if you wantto enter these shops now, come and negotiate with me. Butfor myself, it was just an open four-wall room at Newlook.'But life there at Cato Manor, honestly, it was a very sweet2 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

*^:. M —leVitamin,1 v-f§|%' ^?K^^>LsSi: : *w ?i* ~life, I must be honest.RESISTANCEKwa Mashuphotos, GraceSo you didn 't want to move?No. Actually a lot of people resisted the removing. Andyou know — you must know — that we were removed bySaracens. I still have that in my mind and in my dreams.Some of the people were at work, and then here come thepolicemen, here come the soldiers with those Saracens, andthen they just take all your things in that manner, you know,and shove it on those big government lorries, those for war,and then they just bulldoze your house, just like that. Whenthese men came I remember one night a man knocked andwe were so much afraid, yes. And then he says, "I'm lookingfor my number." This man had been to Cato Manor. He haddiscovered that now his house was just flattened. You see.This was the very thing which touched me. In Cato Manor.The way we were removed. Because we were resisting, wewere saying, "We are happy here."A NEW LIFEWhen you arrived in Kwa Mashu, it must have been verydifferent?Ja, it's changed our lives. We had to live now another life.I don't know how I can put it. Whether it is Western civilizationor culture I don't know, because to me, I may becivilized but I don't want to become cut off from my customsand my culture. Some are very good and I admire them.I still relate to my children, you know, what life was like onthe farm. I want them to know all these things. And here,I'm not very happy, actually, because people seem to haveforgotten their customs and culture, such things. But well,things are changing, maybe I'm outdated, I don't know. Wehave to live with such things. But there are some people whoare just like me, who are interested in seeing to it that wedon't run away from our culture — though we can inherityour Western civilization. There are some parts of yourculture that are good, but I still say that there are some partsof our culture and customs which are very good.When you moved here, did the people from Cato ManorSTAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>Roome/Durbanall come to one area?Actually, many people came here to Kwa Mashu butmany of them were not very quick to adjust themselves tothis life. Others, they stayed here for a few months or sixmonths, then they jumped off to go build those 'squatters' atInanda. They were real Cato Manor people, Umkumbanepeople. Because there were so many laws to deal with now,in a somebody's four-roomed. Then, in Cato Manor, we werenot even paying for this water. And you see the life changedtotally, became too expensive a life, you know. And thenthey couldn't tolerate it, they said; "Oh no, I better go andstart another Umkumbane further out here," you know,rather than pay this water. If I don't pay the rent I'm beingtold that, "Well, we've got to kick you out." There weresome policemen harassing us in the township. Peoplecouldn't do what they were doing in Cato Manor andcouldn't brew all those things which I've mentioned. So lifechanged completely for some people. They said, "Ugh, lifehere! Because there is somebody who is on our shoulders. Itshows that this is not your land, this is not your house, younever paid a thing over it, you just pay rent." And so theyjumped off.Was there any friction between the people who came toKwa Mashu from the different areas? Was there squabblingbetween the people from the different places?Here at Kwa Mashu? No, no. There wasn't at all, becausethose who knew one another from Cato Manor, we used tomake friends with them, you know. There was no squabbling.But there was too much of poverty, I should call itnow because they were not doing what they knew how to doand felt like doing. There was a lot of house-breaking andtheft. It happened to those who wake up very early in themorning to go to town and work. They used to have theirhomes burgled. That was the thing that was happening here.Did a lot of people who had previously not worked haveto go out and work now?No, I think it was just people taking a chance, now thathere we were in a new township. Everything was new. Ja, itwas just one of those things.*A well-known 'Native 3 , then 'Bantu'Administrator in Natal3

To Kill a Man's Pride..An excerpt from a new story by Mtutuzeli Matshobaillustrated by MzwakheRegistration for work is such an interesting example of away of killing a man's pride that I cannot pass it by withoutmention. It was on Monday, after two weeks of unrewardedlabour and perseverence, that Pieters gave me a letter whichsaid I had been employed as a general labourer at his firm andwhich I was to take to the notorious 80 Albert Street.Monday is usually the busiest day there because everybodywakes up on this day determined to find a job. They end updejected, crowding the labour office for 'piece' jobs.That Monday I woke up elated, whistling all the way as Icleaned the coal stove, made fire to warm the house for thosewho were still asleep, and took my toothbrush and washingrags to the tap outside the toilet. The cold water was revivifyingas I splashed it over my upper body. I greeted 'Star', alsowashing at the tap diagonally opposite my home. Then Itook the washing basin, half-filled it with water and wentinto the lavatory to wash the rest of me. When I had finishedwashing and dressing I bade them goodbye at home and setout, swept into the torrent of workers rushing to the station.Somdale had reached the station first and we waited for ourtrains with the hundreds already on the platform. Theguys from the location prefer to wait for trains on the stationbridge. Many of them looked like children who did not wantto go to school."I did not sympathize with them. The littletime my brothers have to themselves, Saturday and Sunday,some of them spend worshipping Bacchus.The train schedule was geared to the morning rush hour.From four in the morning the trains had rumbled in withprecarious frequency. If you stay near the road to the hostelyou are woken up by the shuffle of a myriad footfalls longbefore the first train. I have seen these people on my wayhome when the nocturnal bug has bitten me. All I can say isthat an endless flow of resolute men hastening in the inky,misty morning down Mohale Street to the station is an awesomeapparition.I had arrived ten minutes early at the station. The 'ninety-The full text of "To Kill A Man's Pride", as well as .twenty-four other stones and prose pieces by contemporaryblack South African writers are to appear in a collection entitled FORCED LANDINGAfrica South: Contemporary Writings, edited by Mothobi Mutloatse, and published by Ravan Press, nextmonth. The stories are accompanied by drawings by Nkoana Moyaga and Fikile.FORCED LANDING will be number three in the <strong>Staffrider</strong> Series, (following AFRICA MY BEGINNINGand CALL ME NOT A MAN) and will be available from bookshops and <strong>Staffrider</strong>s in your area soon.STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

five' to George Goch passed Mzimhlopewhile I was there. This train brought thefree morning stuntman show. The daredevilsran along the roof of the train, afew centimetres from the naked cablecarrying thousands of electric volts, andducked under every pylon. One mistimedstep, a slip — and reflex action wouldsend his hand clasping for support. Nocomment from any of us at the station.The train shows have been going onsince time immemorial and have losttheir magic.My train to Faraday arrived, burstingalong the seams with its load. Thespaces between the adjacent coacheswere filled with people. So the onlyway I could get on the train was bywedging myself among those hanging onperilously by hooking their fingers intothe narrow tunnels along the tops of thecoaches, their feet on the door ledges. Aslight wandering of the mind, a suddenswaying of the train as it switched lines,bringing the weight of the others on topof us, a lost grip and another labour unitwould be abruptly terminated. We hungon for dear life until Faraday.In Pieters' office. Four automatictelephones, two scarlet and two orangecoloured, two fancy ashtrays, a gildedball-pen stand complete with gilded penand chain, two flat plastic ashtrays andbaskets, the one on the left marked INand the other one OUT, all displayed onthe poor bland face of a large highlypolished desk. Under my feet a thickcarpet that made me feel like a piece ofdirt. On the soft opal green wall on myleft a big framed 'Desiderata' and aboveme a ceiling of heavenly splendour.Behind the desk, wearing a short creamwhitesafari suit, leaning back in a regalflexible armchair, his hairy legs (the paleskin of which curiously made me thinkof a frog's ventral side) balanced on theedge of the desk in the manner of asheriff in an old-fashioned western, myblue-eyed, slightly bald, jackal-facedoverlord.'You've got your pass?''Yes, mister Pieters.' That one didnot want to be called baas.'Let me see it. I hope it's the rightone. You got a permit to work inJohannesburg?''I was born here, mister Pieters.' Myhands were respectfully behind me.'It doesn't follow.' He removed hislegs from the edge of the table andopened a drawer. Out of it he took asmall bundle of typed papers. Hesigned one of them and handed it to me.'Go to the pass office. Don't spend twodays there. Otherwise you come back andI've taken somebody else in your place.'He squinted his eyes at me andwagged his tongue, trying to amuse methe way he would try to make a babysmile. That really amused me, histrying to amuse me the way he would ababy. I thought he had a baby's mind.'Esibayeni'. Two storey red-brickbuilding occupying a whole block.Address: 80 Albert street, or simply'Pass Office'. Across the street, halfthe block (the remaining half a parkingspace and 'home' of the homelessmethylated spirit drinkers of the city)taken up by another red-brick structure.Not offices this time, but 'Esibayeni'(at the kraal) itself. No questionwhy it has been called that. Thewhole black population of Johannesburgabove pass age knows that place.Like I said, it was full on a Monday,full of wretched men with defeatedeyes, sitting along the gutters on bothsides of Albert street, the whole passoffice block, others grouped where thesun's rays leaked through the skyscrapersand the rest milling about.When a car driven by a white manwent up the street pandemonium brokeloose as men, I mean dirty slovenlymen, trotted behind it and fought togive their passes first. If the whiteperson had not come for that purposethey cursed him until he went outof sight. Occasionally a truck or vanwould come to pick up labourersfor a piece job. The clerk would shoutout the number of men that werewanted for such and such a job, sayforty, and double the number wouldbe all over the truck before you couldsay 'stop'. None of them would want tomiss the cut, which caused quite someproblems for the employer. A shrewdbusinessman would take all and simplydivide the money he had laid out amongthe whole group, as it was left to him todecide how much to pay for a piece job.Everybody was satisfied in the end —the temporary employer having hiswork done in half the time he had bargainedfor, and each of the labourerswith enough for a ticket back to thepass-office the following day, andmaybe ten cents worth of dishwaterand bread from the oily restaurants inthe neighbourhood, for three days.Those who were smart and familiar withthe ways of the pass-office handedtheir passes in with twenty and/orfifty-cent pieces between the pages.This gave them first preference of thebetter jobs.The queue to 'Esibayeni' was movingslowly. It snaked about thirty metresaround the corner of Polly street. It hadtaken me more than an hour to reachthe door. Inside the ten-feet high wallwas an asphalt rectangle, longitudinalbenches along the opposite wall in theshade of narrow tin ledges, filled withbored looking men, toilets on the lowerside of the rectangle, facing wide bustlingdoors. It would take me another threehours to reach the clerks. If I finishedthere just before lunch-time, it meantthat I would not be through with myregistration by four in the afternoonwhen the pass office closed. FortunatelyI had twenty cents and I knew that theblackjacks who worked there werenothing but starving leeches. One tookme up the queue to four people whostood before a snarling white boy. Thosewhose places ahead of me in the queuehad been usurped wasted their breathgrumbling.The man in front of me could notunderstand what was being bawledat him in Afrikaans. The clerk gave upexplaining, not prepared to use anyother language than his own. I felt thatat his age, about twenty, he should be atRAU learning to speak other languages.That way he wouldn't burst a vein tryingto explain everything in one tongue justbecause it was his. He was either boneheadedor downright lazy or else impatientto 'rule the Bantus'.He took a rubber stamp and bangedit furiously on one of the pages ofthe man's pass, and threw the book intothe man's face. 'Go to the other building,stupid!'The man said, 'Thanks,' and elbowedhis way to the door.'Next! Wat soek jy?' he asked in abellicose voice when my turn to besnarled at came. He had freckles all overhis face, and a weak jaw.I gave him the letter of employmentand explained in Afrikaans that Iwanted E and F cards. My talking in histongue eased some of the tensionout of him. He asked for my pass in aslightly calmer manner. I gave it tohim and he paged through. 'Good, youhave permission to work in Johannesburgright enough.' He took two cardsfrom a pile in front of him and laboriouslywrote my pass numbers on them.Again I thought that he should still beat school, learning to write properly. Hestamped the cards and told me to go toroom six in the other block. There wereabout twelve other clerks growling atpeople from behind a continuousU-shaped desk, and the space in front ofthe desk was overcrowded with peoplewho made it difficult to get to the door.Another blackjack barred the entranceto the building across the street.'Where do you think you're going?''Awu! What's wrong with you? I'mgoing to room six to be registered.You're wasting my time,' I answered inan equally unfriendly way. His eyeswere bloodshot, as big as a cow's and asstupid, his breath was fouled with( mai-mai\ and his attitude was a longway from helpful.He spat into his right hand, rubbedhis palms together and grabbed astick that was leaning against the wallnear him. 'Go in,' he challenged, indica-STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 5

ting with a tilt of his head, and dilatinghis gaping nostrils.His behaviour perplexed me, morethan angering or dismaying me. Itmight be that he was drunk; or was Isupposed to produce something first,and was he so uncouth as not to tell mewhy he would not allow me to go in?Whatever the reason, I regretted that Icould not kick some of the 'mai-mai'out of the sagging belly, and proceededon my way. I turned to see if there wasanyone else witnessing the unnecessaryaggression.'No, mfo. You've got to wait forothers who are also going to room six/explained a man with half his teethmissing, wearing a tattered overcoatand nothing to cover his large, parchedfeet. And, before I could say thanks:'Say, mnumzane, have you got a cigaretteon you? Y'know, I haven't hada single smoke since yesterday.'I gave him the one shrivelled LexingtonI had in my shirt-pocket. He indicatedthat he had no matches either. Isearched myself and gave the box tohim. His hands shook violently when helit and shielded the flame. 'Ei! Babalazhas me.''Ya, neh,' I said, for the sake ofsaying something. The man turnedand walked away as if his feet were sore.I leaned against the wall and waited.When there were a good many of uswaiting the gatekeeper grunted that weshould follow him inside to anotherbustling 'kraal'. That was where theblack clerks shouted out the jobs atfifty cents apiece or more, depending onwhether they were permanent ortemporary. The men in there werefighting like mad to reach the row ofwindows where they could hand in theirpasses. We followed the blackjack up asloping cement way rising to a greendouble door.There was nowhere it wasn't full at thepass-office. Here too it was full of thesame miserable figures that were buzzingall over the place, but this time theystood in a series of queues at a longcounter like the one across the street,only this one was L-shaped and the whiteclerks behind the brass grille wore ties. Idecided that they were of a better class'than the others, although there was nodoubt that they also had the samerotten manners and arrogance. Theblackjack left us with another one whotold us which queues to join. Our cardswere taken and handed to a lady filingclerk who went to look for our records.I was right! The clerks were, atbottom, all the same. When I reachedthe counter I pushed my pass under thegrille. The man who took it had closecroppedhair and a thin sharp face. Hewent through my pass checking it againsta photostat record with my namescrawled on top in a handwriting that Idid not know.'Where have you been from Januaryuntil now, September?' he said ina cold voice, looking at me from behindthe grille like a god about to admonish asinner.I have heard some funny tales, frommany tellers, when it come to answeringthat question. See if you can recognisethis one:CLERK:MAN:CLERK:Heer, man. Waar was jy aldie tyd, jong? (Lord, man.Where have you been all thetime,/o?2g?)I ... I was mad, baas.Mad!? You think I'm youruncle, kaffer?KAFFER: No baas, I was mad.CLERK: Jy . . . jy dink . . . (and thewhite man's mouth dropsopen with no words comingout.)KAFFER: (Coming to the rescue ofthe baas with an explanation)At home they tell methat I was mad all along,baas. 'Strue.CLERK: Where are the doctor'spapers? You must have beento hospital if you were mad!(With annoyance.)KAFFER: I was treated by a witchdoctor,baas. Now I ambetter and have found a job.Such answers serve them right. If it istheir aim to harass the poor people withimpossible questions, then they shouldexpect equivalent answers. I did not,however, say something out of the way.I told the truth, 'looking for work.''Looking for work, who?''Baas.''That's right. And what have youbeen living on all along?' he asked,like a god.'Scrounging, and looking for work.'Perhaps he did not know that among usblacks a man is never thrown to thedogs.'Stealing, huh? You should have beencaught before you found this job. Doyou know that you have contravenedsection two, nine, for nine months? Doyou know that you would have gone tojail for two years if you had beencaught, tsotsi? These policemen are notdoing their job anymore,' he said,turning his attention to the stamps andpapers in front of him.I had wanted to tell him that if I hadhad a chance to steal, I would not havehesitated to do so, but I stopped myself.It was the wise thing to act timid in thecircumstances. He gave me the pass afterstamping it. The blackjack told me whichcorridor to follow. I found men sittingon benches alongside one wall and stoodat the end of the queue. The man infront of me shifted and I sat on theedge. This time the queue was reasonablyfast. We moved forward on theseats of our pants. If you wanted to preventthem shining you had to stand upand sit, stand up and sit. You couldnot follow the line standing. Thepatrolling blackjack made you sit in anembarrassing way. Halfway to the doorwe were approaching, the man next tome removed his upper clothes. All theothers nearer to the door had theirclothes bundled under their armpits. Idid the same.We were all vaccinated in the firstroom and moved on to the next onewhere we were X-rayed by some impatientblack technicians. The snakingline of black bodies reminded me ofprisoners being searched. That waswhat 80 Albert Street was all about.The last part of the medical examinationwas the most disgraceful. I don'tknow whether it was designed to saveexpense or on some other ground ofexpediency, but on me it had the effectof dishonour. After being X-rayed wecould put on our shirts and cross thecorridor to the doctor's cubicle. Outsidewere people of both sexes waiting tosettle their own affairs. You passedthem before entering the cubicle, insidewhich sat a fat white man in a whitedust-coat with a face like an owl, behinda simple desk. The man who had gone inahead of me was zipping up his fly. Iunzipped mine and stood facing the owlbehind the desk, holding my trouserswith both hands. He tilted his fat faceto the right and left twice or thrice. 'J a.Your pass.'I hitched my trousers up while heharried me to give him the pass beforeI could zip my trousers. I straightenedmyself at leisure, in spite ofhis ( Gou, gou, gou!' My pride had beenhurt enough by exposing myself to him,with the man behind me preparing to doso and the one in front of me havingdone the same; a row of men of differentages parading themselves before a boredowl. When I finished dressing I gave himthe pass. He put a little maroon stampsomewhere in amongst the last pages. Itmust have meant that I was fit to work.The medical examination was overand the women on the benches outsidepretended they did not know. Theyoung white ladies clicking their heelsup and down the passages showedyou they knew. You held yourselftogether as best as you could until youvanished from their sight, and you nevertold anybody else about it.6 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Profile/Modikwe DikobeModikwe Dikobe was bom in 1913 at Seabe, in theMoretele district He attended St. Cyprian school and thenAlbert St, School between 1924 and 1932, selling newspaperspart-time. He was secretary of the 1942 Alexandrabus dispute and worked with Alexandra squatters in 1946. In1948 he contested the advisory board election in Orlando,and in that year was secretary of ASINAMALL In 1959 hewas involved in organising African shop workers, and throughthe trade union, he published and wrote in a monthlyjournal,< Shopworker\ His book, The Marabi Dance was% published in 1963, and he is now r~"~ J s 'Y ot uoornronteinwhich will cover the history of blacks in Johannesburg basedmainly on his own experiences and memories. The workreflects three processes: the movement of people off the landinto the towns; a discussion of early black life in Johannesburgincluding the beginnings of segregation; and the shiftingof people out of towns onto the land again. The piece wepublish here reflects the pre-apartheid period: the days whenblacks could still own restaurants etc., and is a fictional discussionof the kind that took place in a cafe that was frequentedby ANC sympathisers.Star CafeThe name Star sounds grand to me.It is because its owner Mr Moretsele,affectinately called Retsi, was a man ofthe people. He was like that when hearrived in Pretoria, and later in thegolden city, some sixty years ago.He was born in Sekhukhuneland inthe late eighties. Being a country boywithout education, he worked as adomestic servant where he learned toread and write. He was a follower ofMatseke and Makgatho, Transvaalleaders of Transvaal National Congress.He later joined a national organisation.At the marital age, he lived in theslums of the city. And by hard effortshe found a house in Western NativeTownship. Nkadimeng of MunicipalWorkers Union helped him to find ahouse in Newclare (Western NativeTownship as it's better known.)Low wages and unsuitability of jobstaught him to undo himself, in a wayfamiliar to others who find out to dofor themselves. He ran an unlicensedKoffie-Kar. 'I did not sleep/ he wouldsay, I baked fat cakes on returning fromwork.' He was then working in commercialdistributive trade.'I sold fat cakes, to Market Street,wholesale. The workers there called meRetse. Selling fat cakes earned me betterthan I was receiving from my employer.I ventured into the Koffie-Kar business.A hard task, moving from place toplace.Then I applied for a licence for acafe. I got this cafe . . . * He stopped. Aninspector was passing, then vanishedinto an alley of Indian fruit sellers.'Bastard, subsidises his earnings bybribery. I am sorry for these poorcreatures. They are poorly paid, but willnot budge from claiming baasskap.'Then someone arrived and took aquick table. He was reading a newspaper.'Well Afred, how is your unionworking?' 'Tough job,' he replied.Municipal workers will not tolerate delayin increasing wages. They wantrationing done away with.'- \\Modikwe Dikobe at his home at Seabe, photos, Paul WeinbergAt home with his family'What about negotiation?''Well, Retsi'. He sighed. 'You are abusinessman. A union of workers can beof use to you. Recognition is to youradvantage, if only you have a yellowunion.''I don't understand.''What I mean, Mr Moretsele, is thatthe City Council is contemplating recognition,on condition it has its ownchosen officials. It is in fact negotiatingon those conditions.''Are you selling the workers?''I intend walking out if my secretarysuccumbs to the council's demands.'The sellout took place, however,before MrMoretsile realised it. Nkadimengwas selling down the river therefuse-removers' rights. Mr Nkadimengwas, without much ado, placed in amunicipal house. And, effortlessly, hefound Mr Moretsele a house.Mr Moretsele was a staunch supporterof the left wing. He and Dr Dadoowere personal friends. His other ardentIndia friend was Nana Sitha, who livedin Pretoria. 'You go pass Marabastad,Retsi, me give you message. Pass toPietersburg,' Nana Sitha would say.'You India, no good. Friend here.Your house, me not come in frontdoor.'You're a friend, me no chase away,you sit by table with me.'Moretsele was a modest man, man ofthe people. Job seekers took rest in StarCafe.Then, when Moretsele was buried, asquare in Western Native Townshipwitnessed for the first time black andwhite bemoaning the death of Retsi.OBITUARYDead. I've left MoretseleStains undoneDispossession, land-hungerAnd the right to liveThat you too shall carry onFrom where he shall leave.STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 7

Poetry/SowetoZamani ArtsCAPE TO CAIROThese ebony skin-deep peopleWith their marred but sacred soilShall not crumble asunderThey are what they areThey are AfricaListen to them talkListen to them laughListen to their volcanic stampedeThey tread on their restless ancestorsThey are what they areThey are AfricaDrag them to the TranskeiTie them down to BophutatswanaDrown them within VendalandBut never in the British IslesLet alone the American shoresThey remain what they areThey are AfricaThey overflow in prisonsThey die in multitudesThey are not crematedBut buried to enrich the soilThey are what they areThey are AfricaThese monstrous skyscrapersThose hefty white torsosBear the black palm printsThat raised and fed themThrough ages ungrudginglyThey are what they areThey are anchored in AfricaThey are AfricaThemba Mabele/Zamani Arts, DobsonvilleGRAVITY IN THE HOLEHoles and faded lettersin my Bibleand floods of tearson my handkerchiefGrave mud on my pickand shining shovelWeed and reptilesin my backyardSmoke in my chimneyand black potsfull of fliesand starving cockroachesas lean as my children.Stinging wires on my bedand bugs fatlike factory boss.Nhlanhla Maake/Zamani Arts Association, DobsonvilleOCTOBER 19THThunder rumbled and threatened to destroyour painful joy.We froze as if our boneswere carved of stones.Our hearts beat protest against our chestbut our lips knew silence to be best.We looked up to see our banners of peaceat half mast, torn to many a piece.Tongues without accent whispered in despairas thunder echoed in the air.Our hopes in gagged tone did crybut never to fade and die.A war born of mind and wordshall never cease by the sword.May such a trial be our lastand forever past,So that those who preach our goalsmay not populate gaols,To have their human thoughts subduedin a slough of solitude.Nhlanhla Maake/Zamani Arts Association, DobsonvilleJUSTICEWhen things are like thiswhat do they saythey took him from methey kept him in custodythey said justice would be doneAfter some daysthey took me toointo custodyand left our child aloneour son kept on askingwhere are my parentsthey told himthe justice people took them awayHow long will they keepmy parentsuntil justice is doneI wanted to knowwhat my papa didthey said he was a 'terrorist'I wanted to knowwhat my mama didthey saidshe's the wife of a 'terrorist'then let justice be donebutwhere is justice?Dipuo Moerane/Jabavu, Soweto8 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Poetry/SowetoAllahpoetsTwo Poemsby Maishe MaponyaTHE GHETTOLook deep into the ghettoAnd see modernised gravesWhere only the living dead existManacled with chainsSo as not to resist.Look deep into the ghettoAnd see the streets dividing the gravesStreets watered with tearsStreets with pavementsDyed with bloodBlood of the innocentStreets used by the chainedTo manufacture more chains dailyLook deep into the ghettoYou will see yourselfSilenced by a 99-year leaseThus creating a class struggleWithin a struggle for survival.Look the ghetto overYou will see smog hoverAnd dust chokingThe lifeless-living-deadLook the ghetto overYou will see pain and hungerTorture and oppressionCan you hear beasts of evilAnd creatures of deathBrawling and cryingTo devour youAnd suck the last dropOf blood from your emaciated corpse.Maishe Maponyalishe Maponya and the Allahpoets at a Dube poetry reading,oto, Judas NgwenyaNO ALTERNATIVEYou either stopOr be stoppedYou either serveOr be servedYou have no alternativeEither you say noOr you say yesEither you moveOr be movedYou have no alternativeEither you negotiateOr you don'tEither you fight for itOr you don'tYou have no alternativeYou either oppressOr be oppressedYou have no alternativeWe will all die later!Maishe MaponyaGAME RESERVEI cater for all I mother the wild On my breastThey rest and rust Some see the days passingI am packed: Lions, tigers, tigers, wolves.I bellow like a crazy cow In a slaughter-houseBellowing for my extinction. Elephants, antsBig, big elephants Trampling my little body.Soweto: Human Game Reserve.TONGUEIf I could speakIn the tongues of angels and prophetsPerhaps my wordsWould be takenTo be evidence of injusticeIn you Mother Azania!Mabuse A. Letlhage/CYA, DiepkloofM. Ledwaba/CYA, DiepkloofSTAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>9

Poetry/SowetoFORESEEN YET UNPREVENTED ACCIDENThistorical anno domini yeartime eleventh hourit pulled out of the tranquil stationfour passenger province-carriagesfragmented into racial mini carriage-statesto fulfil goals of separatist ideologyover twenty-million passengersnumber of train: twentieth century arroganceinnocent soulsunsuspecting and relaxedbabies sucking their tasteless dummieslaboriouslysmall girls adorningtheir new dolls with tearssmall boys cherishing the momentof travelling on ever-parallel mini-state rail linesmamas and papas chatting awayabout their household chores] first, second, third . . . fifth stationalways outwards and inwardsbodies carrying spiritual soulsJIout of twentieth arrogance station,then it happenedit was incrediblerecklessly and sadly shocking| the deafening soundsof clattering steel and plankthe ghastly sight of babieswas far from that sight(that sight of sucked dummies)as they were flungflung in the skieslike the lassies' dolliesthe awry scene| not a shadowof the lads' thinking of neat parallel linesa concoction of legsheads arms and torsosstrewn all over the country! topsy turvy land was never meant to look theMakgale J. Mahopo/SowetoPRESSED| The urine burns and stings my small bladderI can feel it fall out in warm small drops.j The Whites-Only toilets are nearby, so are thecopsWho are ready to swoop down upon me as if I1 were an adder..1 My underpants are already wet,My bladder seems to swell and about to burstMy forehead glitters with sweat, and I thirstFor an icy drink. Still the urine drips; I standand fret.I can smell the strong disinfectant waftingfrom the Whites-Only toilets,It seems to be inviting me to come in andease nature,Dear Lord, how can I? I'd rather torture myselfon the pavement; still fall the large droplets.Suddenly I cannot suppress myself anymoreThe urine jets out. I feel its warmth on my skinAs it trickles down into my shoe; passers-bysneer and grinMy dignity as a.man lowered like never before.The sign stinks worse than a human stoolThe warm urine irritates my dry skin.I wonder which is worse, to commit a social sinOr publicly piss myself like a fool.James Twala/Meadowlands, SowetoTO A FRIEND (PIERO)those moments whenwe bled on our kneesweighing old j ohn 'sunprepared journeywe looked deeperinto each other's eyeswe stood togetherhelplessly watchingour friends draggingtheir talents intomincing passagesclaiming nothing in theworld of artwe were sad beyond pitypeople saw us then untila bullet cut throughthe flesh and messed up mindsthrowing our hopes and dreamsawaywe ran, seeking refugein nothingnessthe other dayyou asked me why peopleask you whyagain we bled in silenceand i asked you whyi realised the crossin our timeThemba kaMiya/Klipspruit, Sowetoj10 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Poetry/Johannesburg"HISTORY WILL ABSOLVE ME" FIDELCASTRO(An unfinished poem.)Fidel,History absolves no-one,History takes drugs, has hallucinations,stumbles among the corpses looking for a fix,wakes up in the morning with a dead head& vomits into the future.Africa,shaped like a skullunknown.Men in khaki & incongruous helmetswho stood in poses beneath the sun.No marble columns/ to frame the action.No clear record/ of the number dead.Despatches in the press.Africa — the outhouse,unspeakableacts.Where any civil servant, rough trader, roadmaker,could take his pants offfeel the shit slidesoftly down his legs.But they stayed, Fidel, they stayed.Not in the Cape, where dreams could rest— out beyond the ring of the mountains,annuli of distance, sunsets red as crucifixblood."To preserve our doctrines in purity"The clean holes of bullet wounds.Men with dark beards& the dust on their clothesthe land deepin a dream of itself.Beauty is annihilating, Fidel,the beasts remainedanimal eyes in the darknessthe dark rowsof sweating, serried bodies&"the rest of the worldwas nowhereas far as our ears& eyes were concerned"*Blood River,Kitchener's camps,Bikobeaten on the headto die of brain damagea blind brute of painbellowingbullet woundswide as flowersa child'steargassed eyesbleed for simple merciestruncheon handat the top of its trajectorystatisticsno-one believespolitician'sdull jawsmalicetheir unmoving eyesFidel,Calvin's dead Godgloats in the kwashiorkor glooman animalwith thick flankswaits by the river"die aapmenshy wat nie kan dink nie"**Martin Taylor/Johannesburg*Anna Steenkamp —Journals** N.P. van Wyk Louw — RakaHILLBROWI waited in the cityand all its eyes turned down on me,surprised.Only old women in old slacksdo thatand walk from single roomdown smelly cabbage stairsto supermarket shoppingas old as city chapel flowerbedsbetween the sunless flats.Who would live in Building Block Land?Yeoville, photo, Biddy CrewePatrick Taylor/JohannesburgSTAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 11

NGWANAWA AZ AMI AA film concept by Mothobi Mutloatse/eSkom Arts ,Sowetow^^mmmmMmmThis film has to be shot on location as much as possible, and the musicalscore shall be regarded as an integral rather than minor part of this herculeantask portraying the lot, or is it heap, of the Black child Azania, on celluloid. Itwill definitely not be an intellectual nor fancy exercise: in fact, some or most ofthe participants will have to volunteer to go through hell first before agreeing tomake their contributions, because basically, making a film documentary even ona small aspect of the black man, is sheer agony. One cannot feign pain, it has tobe felt again to put that stamp of authenticity on any documentary, seeing wehave no archives to refer to. Again, much of the documentary's success willdepend on imagination, improvisation and the artistry of all those involved inthis project. The director — at least the bum who decides to take up this seeminglyimpractical proposition — will have to be a strong, patient, open-minded,non-commercial, un-technical artist. He will be expected to do casting himselffrom the camera-man up to the last 'extra'. He will have to read the synopsis,which in many ways is also the shooting script, to everybody at a discussionmeeting where, naturally, he will have to be grilled by everybody. Suggestions,deletions, additions or even alterations to the synopsis, will have to be made.Concerning the musical score, all the musicians will be required to give their owninterpretations of how they view the project, and thereafter agree on the score.• The future of the black child, the recalcitrant Azanian child in South Africa,is as bright as night and this child, forever uprooted, shall grow into a big sittingduck for the uniformed gunslinger.• From ages two to four he shall ponder over whiteness and its intrigue. Fromages five to eight he shall prise open his jacket-like ears and eyes to the starkrealisation of his proud skin of ebony. From ages nine to fifteen he shall hardeninto an aggressive victim of brainbashing and yet prevail. From ages sixteen totwenty-one he shall eventually graduate from a wavering township candle into aflickering life-prisoner of hate and revenge and hate in endless fury. This motherchildshall be crippled mentally and physically for experimental purposesby concerned quack statesmen parading as philanthropists.• This motherchild shall be protected and educated free of state subsidy in anenterprising private business asylum by Mr. Nobody. This motherchild shallmother the fatherless thousands and father boldly the motherless millionpariahs. This nkgonochild shall recall seasons of greed and injustice to her wartriumphantand liberated Azachilds. This mkhuluchild shall pipesmoke in thepeace and tranquility of liberation, and this landchild of the earth shall never becarved up ravenously again and the free and the wild and the proud shall but livetogether in their original own unrestricted domain without fear of one another,and this waterchild shall gaily bear its load without a fuss like any other happymother after many suns and moons of fruitlessness in diabolical inhumanity.• This gamble-child of zwepe shall spin coins with his own delicate life to winthe spoils of struggle that is life itself. This child of despair shall shit in thekitchen; shit in the lounge; shit in the bedroom-cum-lounge-cum-kitchen; heshall shit himself dead; and shall shit everybody as well in solidarity and in hisold-age shall dump his shit legacy for the benefit of his granny-childs: this veryngwana of redemptive suffering; this umtwana shall but revel in revealing offbeat,creative, original graffiti sugar-coated with sweet nothings like:re tlaa ba etsa power/re-lease Mandela/azikhwelwa at all costs/we shall notkneel down to white power/release Sisulu/ jo' ma se moer/black power will beback tonight/release or charge all detainees/msunuwakho/down with booze/Mashinini is going to be back with a bang/to bloody hell with bantu education/don't shoot — we are not fighting/Azania eyethu/masende akho/majority iscoming soon/freedom does not walk it sprints/inkululeko ngokul• This child born in a never-ending war situation shall play marbles seasonablywith TNTs and knife nearly everyone in sight in the neighbourhood for touchand feel with reality, this child of an insane and degenerated society shall knowlove of hatred and the eager teeth of specially-trained biting dogs and he willspeak animatedly of love and rage under the influence of glue and resistance.• This marathon child shall trudge barefooted, thousands of kilometres throughicy and windy and stormy and rainy days and nights to and from rickety churchcum-stable-cum-classroomswith bloated tummy to strengthen him for urbanwork and toil in the goldmines, the diamond mines, the coal mines, the platinum12 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

a storyby Nape'aMotanaIllustratedby Richard Jackthe poetin loveLesetja, a lad of Mamelodi, is a poet. He loves parties,wine and women. Apart from a cluster of girls who are casualor free-lance lovers, he has a steady partner. She is Mathildaor Tilly. She is conspicuously pretty. Some cynics openly sayhe is showing her off like a piece of jewelry.Lesetja is popular among other Mamelodi poets. He readshis stuff at all kinds of parties and shebeens. The secret of hisinstant popularity is simple: he has as material what peoplewill have an opinion on, like or dislike; what is on thepeople's lips. He often argues: 'Why should I bother aboutbirds, bees and trees while my people are trapped in theghetto!'Poetry earns him fame, more company and, sometimes,free liquor. Recently one of the trendy shebeens, The YellowHouse, heard him reading to ecstatic patrons:wet sundayleaves blue m on dayin the lurch;babalaaz chews my brainlike bubble-gum;how can I bubblewhen fermented bottleshobble me?I am boss of the moment —Baas can go to hell!Some of his friends skin him alive for 'grooving throughpoetry*. He tells them that an artist does not live in a vacuum;that an artist reflects his society. His punches aresometimes wild: 'Those who see flowers when corpsesabound are eunuchs!'But his hectic life is not to last. It reaches a climax when,to the dismay of many socialites, he leaves Tilly to settle fora plain woman like Mokgadi. To be frank, Mokgadi is somewherenear ugliness. Lesetja has been stupidly in love withTilly. He admits he has been stupid, unable to see beyond hisarms as they embraced Tilly.His friend, Madumetja remarks once:'You are a true poet/'Why?''Because you see a bush for a bear, a beauty for an uglyduckling.''Do you say Mokgadi is ugly?''This confirms how true a poet you are. Tell me, why didyou "boot" Tilly, such a beauty of a model?''Look here Madumetja, I am responsible for everythingthat I do. Are you playing my godfather?'Lesetja is ruffled. Madumetja is amused. The argumentends in a cul-de-sac. Neither will throw in the towel.The naked truth is: Madumetja is right. Lesetja is a poet.He is romantic about Mokgadi. He imagines he is in love withMiss Afrika. His poetic eyes scoop nothing but beauty fromthis lass who does not deserve a second look.Mokgadi, whom Lesetja dubs 'black diamond', is a universitystudent. She is coal black while he is lighter in complexion.He often brushes her smooth cheek with the back ofhis palm and romanticises: 'Pure black womanhood from theheart of Afrika!' She giggles, displaying a set of snow-whiteteeth which contrast beautifully with her ebony face.One day as he marvels at her somewhat rare complexion,she confesses to him. She tells him her biological father is aZairean whom the government repatriated with scores of'foreign Bantus' in the early 1960s.Mokgadi has a broad, nearly flat nose, typically Zairean.Her mouth is small, presumably like her mother's. Pitchblack-and-whiteeyes seem to bulge. Her waist is thicker as ifshe wears indigenous beads. Her shoulders are wide andnearly round, and do not go well with her small breasts.But Lesetja loves her passionately. His sensitive eyes seenothing but a 'black diamond'. That the secret of art lies inorchestrating the commonplace and unrelated things into onesolid coherent piece of beauty, here applies to Lesetja, onehundred percent.Lesetja meets Mokgadi in the 1970s when black students,thinkers, politicians, writers, artists and theologians areexposed to the upsurge of Black Consciousness. Drama,poetry and art are vibrant. Lesetja is now wiser. He seesbeyond his love-making arms. He sees beyond parties andshebeens.He mixes with knowledgeable people. He reads booksuntil he comes across and loves Frantz Fanon's Black Skins,White Masks. The spiritual metamorphosis spurs him to be acommitted poet. He spits fire and venom. He dislikes artistswho, while they eat hunger, blood and sweat, vomit fruitsalads.Lesetja changes. He is no more a poet of parties. Hebaffles Tilly but she thinks he will come back. He is nolonger that bohemian poet who has been lionised by funlovers. Patrons at The Yellow House cannot understand whyhe is scarce, keeping to himself. Shebeen queens miss hisincisive humorous verse. What has gone wrong with the poetlaureate of Mamelodi? Nobody can furnish the answers.'One must not play with words while Afrika is ablaze,' heharangues those who confront him over his 'new life'. Hediscovers that indulgence in pleasure has been a multipleland-mine on the road towards ideal creativity or politicalfreedom. He hates over-indulgence. He sheds a handful oflovers. He finds them to be either superficial or immature.'Parasites and staffriders!' he thinks aloud. He even feels aOne must not play with words while Africa is ablaze *14 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Spiritual metamorphosis spurs him to be a committed poet.He spits fire and venom. He dislikes artists who, while theyeat hunger, blood and sweat,vomit fruit salads.strong compulsion to live like a hermit, but he still loves thecity hubbub which affords him some raw material.He looks at Tilly through a different pair of eyes. She isonly a beauty, a cabbage-headed non-white model whobattles against nature. Sympathy replaces love. 'No! it wasnot love but lust!' he corrects himself. Tilly has been fit onlyfor a mere 'release of manly venom', he reflects, with bitternessand built. He recalls what he read from Black Skins,White Masks, that womenof Tilly's ilk are adisgrace because theywant to bleach theblack race. They clamourto imprison blacksouls in white skins.Sis!He used to visit Tillythrice a week. Now hecuts the ration drasticallyto nil. She firstdisguises her worry andanger through thehackneyed 'Long timeno see.''Inspiration, darling.''Inspiration forwhat?''That's when I amwriting poems. I mustnot be disturbed.''Have I become adisturbance? That'snews.'Lesetja manages todefuse an otherwise explosivesituation. Heshuts his mouth andtalks about somethingelse.She later suspectsout of feminine instinctthat he keeps anotherwoman closer to hisheart. Jealousy drivesher beserk. Worked uplike a hen whose chickenhas been snatchedby a hawk, she marchesto Lesetja's room. Sheknocks and barks like ablack-jack. The door isnot locked. She stormsin at the speed of a Boeing when it takes off. She is ready fora fight, sweating and shivering.Her bloodshot eyes scrutinise the bed hurriedly. There isLesetja lying! No woman next to him! Maybe the devil of awoman has hidden under the bed or in the wardrobe whenTHEY heard her advancing footsteps. He is alone, surroundedby pencils, drafts of poems, scribblers, books andliterary magazines. A Concise Oxford Dictionary lies on hischest as he gazes at Tilly, as if saying: 'And now?' Anger ather intrusion is tempered by her pitiful state. His unexpectedcoolness frustrates her pent-up emotions. She is benumbedand she just sobs and sobs while he feigns pity. For thirtyminutes they never say a word to each other. He fumbleswith the writing material, packing books and unpackingthem. She holds him at ransom with her rivulets of tears. Shestands up abruptly and leaves dejectedly. Their roads part.Lesetja feels light, asif somebody has takena coal bag off his back.He reads voraciouslyand spends a lot of timedoing some soul-searching.His writingcraftmellows with intensivepractice. Madumetjahas been visiting him,perhaps more out ofcuriosity than friendship.He pokes fun athim: 'It seems youmake it your businessto caress books whileWE fondle dames anddrink the happy waters.'He asks Madumetjato shut his bigmouth or make use ofhis long legs.He knows and seeswhat he wants. Hemoves between blinkers.He attends artexhibitions, poetryreadings and more funerals.One evening he isthunderously applaudedwhen he reads to asmall audience at thelocal church:Black beautyThe soot that you wearis Afrika's proudepidermisMy tongue and craniumexhumefrom your rich bosom,a black diamond.The thrilled poetry lovers congratulate Lesetja and threeother poets after the reading. Mokgadi a student of AfricanLiterature, is stunned and stirred, especially by Lesetja'spoem. This epitome of an African woman has a chitchatwith Lesetja, not knowing that she is talking herself into thepoet's heart.STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 15

Poetry/Swaziland, Lesotho, NamibiaMESSAGE TO JOBURG NORTHYouwithyour cream-white complexionabout to inventa wonderful machineto lift you from bedand stand you in your shoesLook under your feet:For you're standing on a peoplewho'll soon shatter your complacencyand turn offyour electric carving-knife.Richie Levin/SwazilandPART III NO. 1The dark angel took seven starsAnd flung them to the crimson hell-flaresThis quickened the anger of the crowd,Who surged, helpless humanity, against thegaudy podiumAnd virile cowboys start whippingThe air is whipped till it stinksThis happened some years agoAnd, surely not, blood in thick disastrous goutsFrom you yourselfQuick over your sweating body.There will be lines of men with machine-guns,bombed villages,A crate in the shopping centreInto which waste is flung.Behold, if there is no God, I am He.Give me my whip.Peter Stewart/LesothoPART III No. 2.I loved you like the diamondsThat glistened through wet mossesCointreau, the liqueur of oranges, sweet and high,On a tube trainAnd the cities grind onThe cities grind onAnd on my bed I toss, like a carcass of meatturned on the spitAnd in the mine compoundsAnd in the hearts and in the cornerIn the centre five thin uncles play dice for money,with abandonJoshua Mfolo was murdered with an axe onthe 26 of <strong>Feb</strong>ruaryAnd after the oldest tourist train in the world,Fleas on the seats, six minutes,This is the oceanI loved you in the ocean, for my love for youvanished, evaporated, I didn't love you anymoreAnd I drownedAnd divided into many human beingsEach with social class, in some part of theworld, with incomes, status, virtue, and thelack of theseWho are you now?I will love you becauseI do not love you yetBecause of the good news that came whenhunger had helped to reduce the remainingfamily to painfully subdued frustrations andpermanent tension.You are my neighbour.Peter Stewart/LesothoTHE SMALL TRADERHere the policemen go barechestedand the makakunyas, young boys, spiton their country: last nighta store was destroyed by 'persons unknown'the police blame the guerillas,the guerillas blame the police;and the small tradercaught in these sudden eruptionslike dog's vomit on the groundsat up in bed (knowing which side he was on)and wonderedwhich sidewas on himKelwyn Sole/Namibia16 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Poetry/Zimbabwe, LesothoBIRTH OF A PEOPLETell themThese are the joysOf warThe ecstacy of parturitionJoysOf our new lifeSpringingFrom marching in the heatDrinkingCool fountain waterDestroying lifeBent on destroying usThen dying in the sunTo free those who must liveBathing our battered soulsIn the sweet stenchesOf sexPurificationIn our gory gloryQuenching our thirstWith the warm bloodOf manPutrefactionOf the warm bodiesOf manOur gunsEjaculate deathOur guns spew loveOf a new peopleBirth in deathLove in deathA people born of deathA people MUST be bornIn deathZanemvula Mda/LesothoWHEN THEY COME BACKWhen they come backFrom call-upOur sons look strangeEmpty mouths without wordsDeep eyes, gashesDeepened by bayonets of fearPuffing nostrils puffing outImpacts of close shavesAnd when they smileThey smile the smileOf the armyWhen it is not armedThese children look strangeTrailed by an odourAn odour of the armyJulius Chingono/Salisbury, ZimbabweLino-cut, P.C.P. Malumise/RorkesDriftDEATH IS NOT ONLY DEATH FOR THEDEAD BUT IT IS DEATH FOR THE LIVINGClad in BlackShe knelt beside a coffin:Inside, plastered in wood, lay her husband.She mourned for a man goneShe wailed for an African son goneShe cried for a future escaped.She counted sons and daughters in schoolsShe counted daughters and sons in the cradleShe spelled the name of the child at the breastAnd wondered what next to do.The Priest's voice: 'Madam, God save yourwounded soul.'No hope of God could bandage the woundsecurely.The hazards of bleak winds in winter ravagedAnd the hunger of numberless children infectedThe prospect of years ahead, her breadwinnergone.S.M. Tlali/LesothoSOUNDS ARE NO MORESounds are no moreExplosions of seed podsIn regenerationBut explosions of bombsIn degenerationIn our khaki bushes.Julius Chingono/Salisbury, ZimbabweSTAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 17

Gallery ProfileBehind the Lens: JUDAS NGWENYAThe first in a series of interviews with<strong>Staffrider</strong> photographers and graphicartists about themselves and their work,and how they see it in relation tocultural struggle as a whole.I started taking pictures in 1968while I was still at school. Someone lentme a polaroid and when he took it backI was very sad. I bought an instamaticand started using it for black and whitepictures. I photographed children, parties,school-groups. I was still learning,so I didn't charge professional prices, Ijust said, "If you've got 25c it's O.K."In 1970 I bought a good camera. Istarted using colour, and taking photographsof adults: parties, weddings,funerals, competitions. I charged 75c aprint. At this time I was working atCheckers as a packer, so all the photographywas done in my spare time.I didn't think that commercialphotography would take my aims as aphotographer further, but I used themoney to buy photography books so Icould study.In 1973 I resigned from Checkersand started free-lance work. By now Iwas well-known as a wedding/partyphotographer. But I was tired of weddings.I wanted to learn printing andmore advanced techniques, so that Iwould be competent enough to takemore relevant pictures, and I started acorrespondence course in photography.One day, a few years later, I was takingmy granny to Baragwanath hospital.I had my camera with me. It was about10 a.m. I saw a lot of children shouting'Power'. I didn't know what was happening... I wanted to take photographsbut I was scared and confused.There were a lot of police but somethingkept telling me, if I'm a photographerI must take these pictures.I heard taxis hooting, and then I sawdead children on stretchers being carriedout of the taxis. I was helping to carrythe stretchers to the hospital but at thesame time I was seeing colours, colourseverywhere . . . Men in white coats,nurses in blue-striped uniforms, some ingreen and red stripes, men in white andblue overalls. And I kept thinking, Tvegot a colour film in my camera'. But Ialso felt I must help in the situation,and when the hippos came I just ran tothe car. I was very scared. By this time Ihad lost my grandmother: I only foundher the following day at Dube policestation. This was my experience ofKliptownbackyardJune 16th 1976. It was a Wednesday . . .I wanted pictures so that I couldlook back at events and see clearly whathad been happening. But I also knewthat when I took the film to be processedI probably wouldn't get itback. I now know that it's not easy totake photographs in those situations.But Magubane, Moffat Zungu, RalphNdawo . . . they did it. And I've learnedabout how important photographs arein documenting people's lives. Theyremind us of our history: what's happenedbefore and what's going tohappen in the future.In 1978 I got a diploma in photographyfrom a correspondence courseI'd been doing. The diploma's importantto me because it has proved to me that Iunderstand some of the theory of mywork.Then I joined the photography workshopat the Open School. That waswhere I finally learned how to developand print my own work. I won a pocketcamera in a competition: this encouragedme a lot. If you're takingpictures, you need people to see yourwork and react to it, otherwise youdon't make progress. To take pictures isto learn, and to see what the lives of thepeople are like: most are suffering,though some aren't. People have verydifferent existences, and photographs18 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

'I wanted pictures so that I could look back at events and see clearly what had been happening.'live? We have no place to sleep . . . can't get job'Where must we .../DoornfonteinReturningmigrantsshow that.Even now I need advice and criticism from other photographers.I need to talk with old-timers like Magubane,Robert Tshabalala, Ndawo. Although I want to avoid takingsimilar pictures to, say, Magubane. That's why I buy booksof other photographers' work: to see how they operate.STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>Because I want to create things that are my own, not copiesof someone else's work.So it's a learn and teach process: now I'm working on ayouth project with YWCA, teaching kids (10-15 yearolds) to take pictures with instamatics. Which is where Istarted long ago.19

The Slumbering SpiritA short story by Jayapraga Reddyillustrated by Mike van NiekerkTerry set off for the shops as usual.It was only seven in the morning butalready the day was hot, the relentlessheat building up slowly. By noon itwould make work impossible and lieupon them all like something heavy andtangible. He kicked a stone on thepathway. From the kitchen, his mothersaw him and she thrust her head out ofthe window. 'Terry' she warned, 'thoseshoes must last for a year, remember!And hurry up! Or you'll be late forschool!'She disappeared and resumed herearly morning tasks of preparing breakfastand packing eight school lunches.Terry quickened his steps but outsidethe gate he slowed down. He hatedMondays. After the carefree freedomand fun of the weekends, Mondaysseemed a bad mistake. He and hisfriends played games of high adventurein the huge storm water pipes. Or theywould go exploring the whole of Durban.Sometimes on a Sunday theywould go to the other side of town tothe old Indian temple. There wouldusually be a wedding on and they wouldsit down to a mouth-watering meal ofrice and pungent vegetable curriesserved on banana leaves. Ah yes, weekendsmeant living the way you wantedto. Running with the wind, dreaming inthe grass and smelling the sun hot andsweet on one's skin. He sighed regretfully.But it was a Monday and therewas school. He would have to hurry.At the corner, he paused. Someonehad called,'Hey boy!'It was old Miss Anderson, the whitewoman, who lived at the end of thestreet.In those days the Group Areas Actwas slowly trying to sort out the differentraces in the interest of separatedevelopment. But in the meantime,whites, 'coloureds', Indians and even afew Chinese, lived cheek by jowl in thecity. In their neighbourhood there werea handful of whites. And Miss Andersonwas one of them. She lived all alonewith a nondescript mongrel and two oldcats. Her sole relative was a sister, muchyounger than herself, who lived somewherein Canada. Thrice a week anAfrican maid came in to do the cleaning.Nobody in the street knew muchabout Miss Anderson. She lived quietlyand kept very much to herself. It wasrumoured that she was very rich but noone could be sure of that.Now Terry glanced enquiringly towardsthe stoep where the old womanstood. She motioned to him to wait.She hobbled towards the gate on herstick. The dog followed tiredly.'Young man, could you get me a fewthings from the shop?' she asked in athin, quavering voice.He nodded. She held out the money.'Buy yourself some sweets from thechange,' she said. 'Just get me somebread, cheese and half a dozen eggs.'He took the money with murmuredthanks. She was so very old and frail, hethought. Her hair was snowy white andthis gave her an added air of fragility.When he returned, she was sitting onthe stoep in a rocking-chair. He took thethings to her which she accepted with aquivering smile. 'Thank you, my boy.You're very kind.'He went home but did not mentionthe errand he had done.The following afternoon on his wayto the shop, he paused to glance at thehouse. She sat there, waiting for him,rocking gently. She beckoned to him.The dog lay languidly at her feet, andwagged his tail half-heartedly. Terrywent up the few steps and stood besideher. The red stoep was clean and shining.It had been polished that day; heknew, fox he could still smell the polish.Roses grew in wild profusion over thewhite lattice which partly screened theverandah. He noticed the unusual quietIt was alien to him. Their house, withten children, resounded with laughterand noise. He wondered what it was likeinside.'I looked for you this morning,' shesaid.He explained that he went to theshop in the mornings only on Mondays.She nodded.'I see. Well, would you mind stoppingby on your way, just to get mea few things?''Alright. I don't mind,' he agreedcasually.'You are so kind, you are so differentfrom the other "coloured" boys fromthese parts,' she remarked.He shifted a little uncomfortably, forhe was unused to praise. Different? Inwhat way was he different? He watchedher fumbling in her purse with handsthat were knotted with arthritis.'There, keep the change,' she said.When he returned she was there,waiting. 'Sit down boy,' she said,motioning him to a chair.He shook his head, saying he preferredto stand. He glanced anxiouslyat the street, hoping none of his friendswould see him. He dreaded the curiousprying and merciless teasing which wasbound to follow. He stood there awkwardlyas she tried to draw him out.'What's your name, boy?' she asked.He told her.'How old are you and how many arethere in the family?'He told her that he was eleven yearsold and that there were ten children inthe family.'Ten!' she exclaimed, incredulous.'Now that's a big family! Are they all inschool?'No, he explained haltingly. Therewas the baby and his eldest sister, Pam,who worked. Pam would leave themsoon, he went on. She was going to get20 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

h ~ ^ ,' * i'fI 1%££•>_~_.v* IF JI .1i'fti|P| e. x,^' * '; IV« pWfjfi_ U \tf *»tfitfmmm

ing him from doing anything dangerousor foolish. She, in turn, was rewardedby his patient attention while shereminisced about the old days, and thehappy times of her youth. Sometimesthough, the adult in her irked him, for itreminded him too acutely that he wasstill a child. Like when she gushedpatronisingly, 'You are such a goodboy!'There was the time when hehappened to mention that Pam waslooking for a place of her own. Sheconsidered him thoughtfully for amoment and then said, 'How manyrooms does she need? I could let herhave two.'And that was how Pam and herhusband came to live with the oldwoman, much against his mother'swishes.So the next few years rolled on. Heno longer did any errands for Miss Andersonas Pam took over. The womangrew frailer and less mobile. Her body,stiffened by arthritis, made it difficultfor her to move, even onto the stoep.The dog too grew old and enfeebled. Hewould lie on the floor near the oldwoman's bed where she could reach outand touch him. Often Terry wouldwatch her as she painfully penned herletters to her sister.Pam did a lot to help the old woman.She cooked her meals and tended to herwhen she was ill. Soon the old womangrew too ill to leave her bed. Terryknew it would not be long, and takingPam's advice, he stayed away.When at last it was all over, Paminformed the old woman's lawyer, asshe had been instructed to do. A telegramwas sent to the sister in Canada.At the funeral only the lawyer, Terryand his family were present. His motherjustified her presence by saying that noperson should be buried unmourned andno funeral should go unwitnessed.A few days later, the sister arrived.She was healthy and energetic and gotdown to the business of sorting thingsout. She was calm and displayed nogrief.'I must thank you and your brotherfor being good to her,' she said to Pam.'She used to write to me about howgood your brother was to her.'She stayed for two weeks, duringwhich time she packed everything andput the house up for sale. The lawyerwas to handle the sale. She allowed Pamto stay on till she found a place.And then on her last day, she said toTerry, 'I would like you to have thedog. Every boy loves a dog. I'm sureyou'll take good care of him.'Terry stared at her, speechless. Everyboy loves a dog. But an old dog whowas too tired to even wag his tail andwho moved so stiffly?That night everyone sat around thekitchen table, strangely silent. Hismother was doing the ironing and Pamwas washing up. Terry was doing hishomework with the dog lying mutely athis feet. Pam turned from the sink.'To think she did not even leave us apot plant!' she observed indignantly.She resumed her washing up withrenewed vigour, unable to conceal herdisgust.'I told you, didn't I? Never trust awhite. They worry about their ownskins, not the next man. Let this be alesson to you,' she warned.'But Ma', Pam began.'Weren't expecting anything, wereyou?' her mother demanded sharply.Pam didn't answer. She was tooangry, too disillusioned to answer.Besides, she didn't think she couldanswer that question honestly.Terry reached under the table andpatted the dog. He moved his tail limplyand raised his head to lick his hand.Somehow, he found it oddly comforting.Terry wished they wouldn't talkabout it. It was his first experience ofpain. He got up and left the kitchen.The dog followed. Already he was ashadow, inevitably tagging behind him.Outside, the night was quiet andcool. In his heart, he knew they werewrong. He could have told them that,had he been articulate enough. Miss Andersonhad given him something,something more precious than anythingmaterial. Years later, he was to recogniseit for what it really was. Butstanding there, in the cool night air,with a lift of the heart, he remembereda gentle old woman on a sun-warmedstoep. She had given him time andfriendship, and something else which hisfourteen-year-old mind was too youngto analyse. It was an awakening, anawakening of the slumbering spirit tomutual sharing and communication andsympathetic understanding. And thatwas something he would carry with himfor a lifetime.Yes, he would take good care of thedog. A dog knew about trust and friendship.Even if he was just an ordinary andnondescript mongrel.Poetry/Cape TownA SONG OF AFRICANIZATIONI'd like to trace my progress from mybackground: liberal, classic;I used to read Houghton, now I readLegassick.My journey from the truths weVe learntby rote;I used to be a Prog, now I don't vote.I've broadened my concerns beyond theshrinking rand;I used to dig the Stones, now I'm into Brand.I've adopted a new theory, a new set of beliefs:I used to root for Chelsea, now I back the Chiefs.I'm now of this continent, a native, an insider;I used to write for Contrast, now its for<strong>Staffrider</strong>.My theories have brought understanding ofour paralysis;I used to look at race, now I'm sold on classanalysis.But all I've learnt is that I really cannot fit;I used to think I'd stay, now I'm about to split.Paul Benjamin/Cape Town1976I cannot say I marched that dayWhen lives were lost to win a prideThey never stole from me.I have not mourned the fallen closeBut counted in the quiet of twilight suburbs.Paul Benjamin/Cape Town22 STAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong>

Poetry/Port Elizabeth, GuguletuPort Elizabeth Young Artists AssociationTRIBUTE TO THE MARTYRSWhen you stood up,Castrating the chain that binds youTo your oppression and enslavement;When you stood up,Rejecting the educationThat enfeebles your mind;Like in Sharpeville you fellIn hundreds and thousandsAt the hands of the rulersOf this my beloved countrySuckers of this my sweat and bloodRapers of this my rich soil of Africa.We raised our clenched fistsAs big as our heartsWe showed solidarity to your familiesUnzima lomthwalo, ufuna simanyaneWe sang in the graveyardWhen we laid down your bodiesTo join our ancestors in their ancestral war.When we turned our backs to your gravesWe felt your spiritsCutting our heartsSearching for our sincerity to the causeThe pain of this experienceBrought tears to my eyesTears that would turn to bloodAnd water the tree,The tree you wateredWith your blood so selflessly.You showed your loveUnlimited for us children of AfricaYou laid your lives downWe will never restUntil the dayWhen what belongs to meIs returned to meAnd justice prevails once moreIn this beautiful country of our forefathers.And on that day I will say again:Rest in peace my brothers and sistersYour sacrifices have not been in vain.Fezile Sikhumbuzo Tshume/Peyarta,Port ElizabethTHE FREEDOM WAGONBrother,It has approached its destinationIt's the freedom wagon up thereIt's come to free me and youFrom the bondage that hindersYour growth and mine.Brother,I'm creatingUnder the yoke that suppresses my creativityBecause it needs me I'm its passengerThe freedom wagonCreativity is artArt is cultureBe one of the passengersLet's create.Charles Xola Mbikwana/Peyarta,Port ElizabethBANNEDHe is strong handsome and blackNever smiles unless he sees meAlways hating till he loves meAlmost as quiet as death can beTill my voice tells him I'm back.You think he is bitter don't you?But would you feel any better bannedfrom the worldAnd confined within the wallsOf a township house that you abhor?Mandi Williams/Peyarta,Port ElizabethWISHESI wanted to be a pastor in my youthA pastor who would quench the thirstand hunger of our youthI wanted to be a mentor in my youthto soothe the pain of the enraged kinto protect the squatter baby of thedemolished tinYes, illusionsare beautifulI wanted to be a true orator in my youthto tell the true storiesthat will ring in our earsI wanted to be an architect in my youthto build high monumentsthat will shelter us in our timeYes, dreamsare beautifulBut these our wishesare whitewashed by witches.Nkos'omzi Ngcukana/GuguletuSTAFFRIDER, FEBRUARY <strong>1980</strong> 23