Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

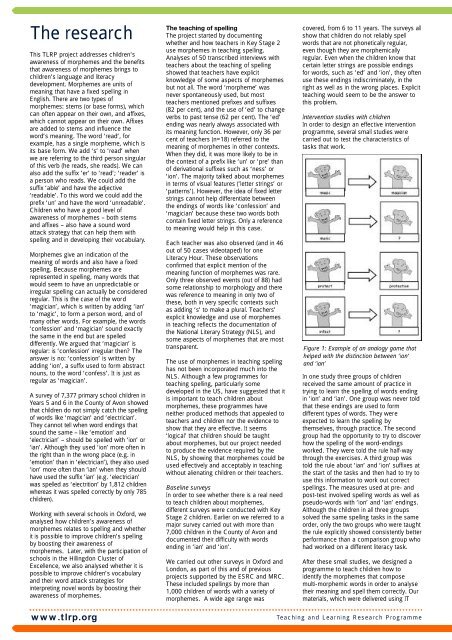

The researchThis TLRP project addresses children'saw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> and the benefitsthat aw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> br<strong>in</strong>gs tochildren’s language and <strong>literacy</strong>development. Morphemes <strong>are</strong> units ofmean<strong>in</strong>g that have a fixed spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>English. There <strong>are</strong> two types of<strong>morphemes</strong>: stems (or base forms), whichcan often appear on their own, and affixes,which cannot appear on their own. Affixes<strong>are</strong> added to stems and <strong>in</strong>fluence theword’s mean<strong>in</strong>g. The word ‘read’, forexample, has a s<strong>in</strong>gle morpheme, which isits base form. We add ‘s’ to ‘read’ whenwe <strong>are</strong> referr<strong>in</strong>g to the third person s<strong>in</strong>gularof this verb (he reads, she reads). We canalso add the suffix ‘er’ to ‘read’; ‘reader’ isa person who reads. We could add thesuffix ‘able’ and have the adjective‘readable’. To this word we could add theprefix ‘un’ and have the word ‘unreadable’.Children who have a good level ofaw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> – both stemsand affixes – also have a sound wordattack strategy that can help them withspell<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g their vocabulary.Morphemes give an <strong>in</strong>dication of themean<strong>in</strong>g of words and also have a fixedspell<strong>in</strong>g. Because <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>are</strong>represented <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g, many words thatwould seem to have an unpredictable orirregular spell<strong>in</strong>g can actually be consideredregular. This is the case of the word‘magician’, which is written by add<strong>in</strong>g ‘ian’to ‘magic’, to form a person word, and ofmany other words. For example, the words‘confession’ and ‘magician’ sound exactlythe same <strong>in</strong> the end but <strong>are</strong> spelleddifferently. We argued that ‘magician’ isregular: is ‘confession’ irregular then? Theanswer is no: ‘confession’ is written byadd<strong>in</strong>g ‘ion’, a suffix used to form abstractnouns, to the word ‘confess’. It is just asregular as ‘magician’.A survey of 7,377 <strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong> children <strong>in</strong>Years 5 and 6 <strong>in</strong> the County of Avon showedthat children do not simply catch the spell<strong>in</strong>gof words like ‘magician’ and ‘electrician’.They cannot tell when word end<strong>in</strong>gs thatsound the same – like ‘emotion’ and‘electrician’ – should be spelled with ‘ion’ or‘ian’. Although they used ‘ion’ more often <strong>in</strong>the right than <strong>in</strong> the wrong place (e.g. <strong>in</strong>‘emotion’ than <strong>in</strong> ‘electrician’), they also used‘ion’ more often than ‘ian’ when they shouldhave used the suffix ‘ian’ (e.g. ‘electrician’was spelled as ‘electrition’ by 1,812 childre nw h e reas it was spelled correctly by only 785c h i l d ren).Work<strong>in</strong>g with several <strong>school</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Oxford, weanalysed how children’s aw<strong>are</strong>ness of<strong>morphemes</strong> relates to spell<strong>in</strong>g and whetherit is possible to improve children’s spell<strong>in</strong>gby boost<strong>in</strong>g their aw<strong>are</strong>ness of<strong>morphemes</strong>. Later, with the participation of<strong>school</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Hill<strong>in</strong>gdon Cluster ofExcellence, we also analysed whether it ispossible to improve children’s vocabularyand their word attack strategies for<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g novel words by boost<strong>in</strong>g theiraw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong>.The teach<strong>in</strong>g of spell<strong>in</strong>gThe project started by document<strong>in</strong>gwhether and how teachers <strong>in</strong> Key Stage 2use <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>g.Analyses of 50 transcribed <strong>in</strong>terviews withteachers about the teach<strong>in</strong>g of spell<strong>in</strong>gshowed that teachers have explicitknowledge of some aspects of <strong>morphemes</strong>but not all. The word ‘morpheme’ wasnever spontaneously used, but mostteachers mentioned prefixes and suffixes(82 per cent), and the use of ‘ed’ to changeverbs to past tense (62 per cent). The ‘ed’end<strong>in</strong>g was nearly always associated withits mean<strong>in</strong>g function. However, only 36 percent of teachers (n=18) referred to themean<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> other contexts.When they did, it was more likely to be <strong>in</strong>the context of a prefix like ‘un’ or ‘pre’ thanof derivational suffixes such as ‘ness’ or‘ion’. The majority talked about <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong> terms of visual features (‘letter str<strong>in</strong>gs’ or‘patterns’). However, the idea of fixed letterstr<strong>in</strong>gs cannot help differentiate betweenthe end<strong>in</strong>gs of words like ‘confession’ and‘magician’ because these two words bothconta<strong>in</strong> fixed letter str<strong>in</strong>gs. Only a referenceto mean<strong>in</strong>g would help <strong>in</strong> this case.Each teacher was also observed (and <strong>in</strong> 46out of 50 cases videotaped) for oneLiteracy Hour. These observationsconfirmed that explicit mention of themean<strong>in</strong>g function of <strong>morphemes</strong> was r<strong>are</strong>.Only three observed events (out of 88) hadsome relationship to morphology and therewas reference to mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> only two ofthese, both <strong>in</strong> very specific contexts suchas add<strong>in</strong>g ‘s’ to make a plural. Teachers’explicit knowledge and use of <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g reflects the documentation ofthe National Literary Strategy (NLS), andsome aspects of <strong>morphemes</strong> that <strong>are</strong> mosttransp<strong>are</strong>nt.The use of <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>ghas not been <strong>in</strong>corporated much <strong>in</strong>to theNLS. Although a few programmes forteach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>g, particularly somedeveloped <strong>in</strong> the US, have suggested that itis important to teach children about<strong>morphemes</strong>, these programmes haveneither produced methods that appealed toteachers and children nor the evidence toshow that they <strong>are</strong> effective. It seems‘logical’ that children should be taughtabout <strong>morphemes</strong>, but our project neededto produce the evidence required by theNLS, by show<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>morphemes</strong> could beused effectively and acceptably <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gwithout alienat<strong>in</strong>g children or their teachers.Basel<strong>in</strong>e surveysIn order to see whether there is a real needto teach children about <strong>morphemes</strong>,different surveys were conducted with KeyStage 2 children. Earlier on we referred to amajor survey carried out with more than7,000 children <strong>in</strong> the County of Avon anddocumented their difficulty with wordsend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> ‘ian’ and ‘ion’.We carried out other surveys <strong>in</strong> Oxford andLondon, as part of this and of previousprojects supported by the ESRC and MRC.These <strong>in</strong>cluded spell<strong>in</strong>gs by more than1,000 children of words with a variety of<strong>morphemes</strong>. A wide age range wascovered, from 6 to 11 years. The surveys allshow that children do not reliably spellwords that <strong>are</strong> not phonetically regular,even though they <strong>are</strong> morphemicallyregular. Even when the children know thatcerta<strong>in</strong> letter str<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>are</strong> possible end<strong>in</strong>gsfor words, such as ‘ed’ and ‘ion’, they oftenuse these end<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ately, <strong>in</strong> theright as well as <strong>in</strong> the wrong places. Explicitteach<strong>in</strong>g would seem to be the answer tothis problem.Intervention studies with childrenIn order to design an effective <strong>in</strong>terventionprogramme, several small studies werecarried out to test the characteristics oftasks that work.Figure 1: Example of an analogy game thathelped with the dist<strong>in</strong>ction between ‘ion’and ‘ian’In one study three groups of childrenreceived the same amount of practice <strong>in</strong>try<strong>in</strong>g to learn the spell<strong>in</strong>g of words end<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> ‘ion’ and ‘ian’. One group was never toldthat these end<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>are</strong> used to formdifferent types of words. They wereexpected to learn the spell<strong>in</strong>g bythemselves, through practice. The secondgroup had the opportunity to try to discoverhow the spell<strong>in</strong>g of the word-end<strong>in</strong>gsworked. They were told the rule half-waythrough the exercises. A third group wastold the rule about ‘ian’ and ‘ion’ suffixes atthe start of the tasks and then had to try touse this <strong>in</strong>formation to work out correctspell<strong>in</strong>gs. The measures used at pre- andpost-test <strong>in</strong>volved spell<strong>in</strong>g words as well aspseudo-words with ‘ion’ and ‘ian’ end<strong>in</strong>gs.Although the children <strong>in</strong> all three groupssolved the same spell<strong>in</strong>g tasks <strong>in</strong> the sameorder, only the two groups who were taughtthe rule explicitly showed consistently betterperformance than a comparison group whohad worked on a different <strong>literacy</strong> task.After these small studies, we designed aprogramme to teach children how toidentify the <strong>morphemes</strong> that composemulti-morphemic words <strong>in</strong> order to analysetheir mean<strong>in</strong>g and spell them correctly. Ourmaterials, which were delivered us<strong>in</strong>g ITwww.tlrp.orgTeac hi ng and Lear ni ng Resea rch Pro g r a m m e