Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Why morphemes are useful in primary school literacy

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

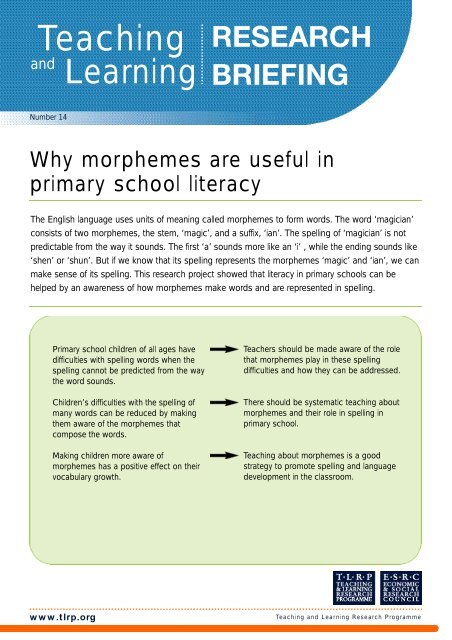

Teach<strong>in</strong>gandL e a rn i n gRESEARCHBRIEFINGNumber 14<strong>Why</strong> <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>are</strong> <strong>useful</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong> <strong>literacy</strong>The English language uses units of mean<strong>in</strong>g called <strong>morphemes</strong> to form words. The word ‘magician’consists of two <strong>morphemes</strong>, the stem, ‘magic’, and a suffix, ‘ian’. The spell<strong>in</strong>g of ‘magician’ is notp redictable from the way it sounds. The first ‘a’ sounds more like an ‘i’ , while the end<strong>in</strong>g sounds like‘shen’ or ‘shun’. But if we know that its spell<strong>in</strong>g re p resents the <strong>morphemes</strong> ‘magic’ and ‘ian’, we canmake sense of its spell<strong>in</strong>g. This re s e a rch project showed that <strong>literacy</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong>s can behelped by an aw<strong>are</strong>ness of how <strong>morphemes</strong> make words and <strong>are</strong> re p resented <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g.Primary <strong>school</strong> children of all ages havedifficulties with spell<strong>in</strong>g words when thespell<strong>in</strong>g cannot be predicted from the waythe word sounds.Children’s difficulties with the spell<strong>in</strong>g ofmany words can be reduced by mak<strong>in</strong>gthem aw<strong>are</strong> of the <strong>morphemes</strong> thatcompose the words.Mak<strong>in</strong>g children more aw<strong>are</strong> of<strong>morphemes</strong> has a positive effect on theirvocabulary growth.Teachers should be made aw<strong>are</strong> of the rolethat <strong>morphemes</strong> play <strong>in</strong> these spell<strong>in</strong>gdifficulties and how they can be addressed.There should be systematic teach<strong>in</strong>g about<strong>morphemes</strong> and their role <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong><strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong>.Teach<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>morphemes</strong> is a goodstrategy to promote spell<strong>in</strong>g and languagedevelopment <strong>in</strong> the classroom.www.tlrp.orgTea chi ng and Lea rni ng Rese arch Pro g r a m m e

The researchThis TLRP project addresses children'saw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> and the benefitsthat aw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> br<strong>in</strong>gs tochildren’s language and <strong>literacy</strong>development. Morphemes <strong>are</strong> units ofmean<strong>in</strong>g that have a fixed spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>English. There <strong>are</strong> two types of<strong>morphemes</strong>: stems (or base forms), whichcan often appear on their own, and affixes,which cannot appear on their own. Affixes<strong>are</strong> added to stems and <strong>in</strong>fluence theword’s mean<strong>in</strong>g. The word ‘read’, forexample, has a s<strong>in</strong>gle morpheme, which isits base form. We add ‘s’ to ‘read’ whenwe <strong>are</strong> referr<strong>in</strong>g to the third person s<strong>in</strong>gularof this verb (he reads, she reads). We canalso add the suffix ‘er’ to ‘read’; ‘reader’ isa person who reads. We could add thesuffix ‘able’ and have the adjective‘readable’. To this word we could add theprefix ‘un’ and have the word ‘unreadable’.Children who have a good level ofaw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong> – both stemsand affixes – also have a sound wordattack strategy that can help them withspell<strong>in</strong>g and <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g their vocabulary.Morphemes give an <strong>in</strong>dication of themean<strong>in</strong>g of words and also have a fixedspell<strong>in</strong>g. Because <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>are</strong>represented <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g, many words thatwould seem to have an unpredictable orirregular spell<strong>in</strong>g can actually be consideredregular. This is the case of the word‘magician’, which is written by add<strong>in</strong>g ‘ian’to ‘magic’, to form a person word, and ofmany other words. For example, the words‘confession’ and ‘magician’ sound exactlythe same <strong>in</strong> the end but <strong>are</strong> spelleddifferently. We argued that ‘magician’ isregular: is ‘confession’ irregular then? Theanswer is no: ‘confession’ is written byadd<strong>in</strong>g ‘ion’, a suffix used to form abstractnouns, to the word ‘confess’. It is just asregular as ‘magician’.A survey of 7,377 <strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong> children <strong>in</strong>Years 5 and 6 <strong>in</strong> the County of Avon showedthat children do not simply catch the spell<strong>in</strong>gof words like ‘magician’ and ‘electrician’.They cannot tell when word end<strong>in</strong>gs thatsound the same – like ‘emotion’ and‘electrician’ – should be spelled with ‘ion’ or‘ian’. Although they used ‘ion’ more often <strong>in</strong>the right than <strong>in</strong> the wrong place (e.g. <strong>in</strong>‘emotion’ than <strong>in</strong> ‘electrician’), they also used‘ion’ more often than ‘ian’ when they shouldhave used the suffix ‘ian’ (e.g. ‘electrician’was spelled as ‘electrition’ by 1,812 childre nw h e reas it was spelled correctly by only 785c h i l d ren).Work<strong>in</strong>g with several <strong>school</strong>s <strong>in</strong> Oxford, weanalysed how children’s aw<strong>are</strong>ness of<strong>morphemes</strong> relates to spell<strong>in</strong>g and whetherit is possible to improve children’s spell<strong>in</strong>gby boost<strong>in</strong>g their aw<strong>are</strong>ness of<strong>morphemes</strong>. Later, with the participation of<strong>school</strong>s <strong>in</strong> the Hill<strong>in</strong>gdon Cluster ofExcellence, we also analysed whether it ispossible to improve children’s vocabularyand their word attack strategies for<strong>in</strong>terpret<strong>in</strong>g novel words by boost<strong>in</strong>g theiraw<strong>are</strong>ness of <strong>morphemes</strong>.The teach<strong>in</strong>g of spell<strong>in</strong>gThe project started by document<strong>in</strong>gwhether and how teachers <strong>in</strong> Key Stage 2use <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>g.Analyses of 50 transcribed <strong>in</strong>terviews withteachers about the teach<strong>in</strong>g of spell<strong>in</strong>gshowed that teachers have explicitknowledge of some aspects of <strong>morphemes</strong>but not all. The word ‘morpheme’ wasnever spontaneously used, but mostteachers mentioned prefixes and suffixes(82 per cent), and the use of ‘ed’ to changeverbs to past tense (62 per cent). The ‘ed’end<strong>in</strong>g was nearly always associated withits mean<strong>in</strong>g function. However, only 36 percent of teachers (n=18) referred to themean<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> other contexts.When they did, it was more likely to be <strong>in</strong>the context of a prefix like ‘un’ or ‘pre’ thanof derivational suffixes such as ‘ness’ or‘ion’. The majority talked about <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong> terms of visual features (‘letter str<strong>in</strong>gs’ or‘patterns’). However, the idea of fixed letterstr<strong>in</strong>gs cannot help differentiate betweenthe end<strong>in</strong>gs of words like ‘confession’ and‘magician’ because these two words bothconta<strong>in</strong> fixed letter str<strong>in</strong>gs. Only a referenceto mean<strong>in</strong>g would help <strong>in</strong> this case.Each teacher was also observed (and <strong>in</strong> 46out of 50 cases videotaped) for oneLiteracy Hour. These observationsconfirmed that explicit mention of themean<strong>in</strong>g function of <strong>morphemes</strong> was r<strong>are</strong>.Only three observed events (out of 88) hadsome relationship to morphology and therewas reference to mean<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> only two ofthese, both <strong>in</strong> very specific contexts suchas add<strong>in</strong>g ‘s’ to make a plural. Teachers’explicit knowledge and use of <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g reflects the documentation ofthe National Literary Strategy (NLS), andsome aspects of <strong>morphemes</strong> that <strong>are</strong> mosttransp<strong>are</strong>nt.The use of <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>ghas not been <strong>in</strong>corporated much <strong>in</strong>to theNLS. Although a few programmes forteach<strong>in</strong>g spell<strong>in</strong>g, particularly somedeveloped <strong>in</strong> the US, have suggested that itis important to teach children about<strong>morphemes</strong>, these programmes haveneither produced methods that appealed toteachers and children nor the evidence toshow that they <strong>are</strong> effective. It seems‘logical’ that children should be taughtabout <strong>morphemes</strong>, but our project neededto produce the evidence required by theNLS, by show<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>morphemes</strong> could beused effectively and acceptably <strong>in</strong> teach<strong>in</strong>gwithout alienat<strong>in</strong>g children or their teachers.Basel<strong>in</strong>e surveysIn order to see whether there is a real needto teach children about <strong>morphemes</strong>,different surveys were conducted with KeyStage 2 children. Earlier on we referred to amajor survey carried out with more than7,000 children <strong>in</strong> the County of Avon anddocumented their difficulty with wordsend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> ‘ian’ and ‘ion’.We carried out other surveys <strong>in</strong> Oxford andLondon, as part of this and of previousprojects supported by the ESRC and MRC.These <strong>in</strong>cluded spell<strong>in</strong>gs by more than1,000 children of words with a variety of<strong>morphemes</strong>. A wide age range wascovered, from 6 to 11 years. The surveys allshow that children do not reliably spellwords that <strong>are</strong> not phonetically regular,even though they <strong>are</strong> morphemicallyregular. Even when the children know thatcerta<strong>in</strong> letter str<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>are</strong> possible end<strong>in</strong>gsfor words, such as ‘ed’ and ‘ion’, they oftenuse these end<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>in</strong>discrim<strong>in</strong>ately, <strong>in</strong> theright as well as <strong>in</strong> the wrong places. Explicitteach<strong>in</strong>g would seem to be the answer tothis problem.Intervention studies with childrenIn order to design an effective <strong>in</strong>terventionprogramme, several small studies werecarried out to test the characteristics oftasks that work.Figure 1: Example of an analogy game thathelped with the dist<strong>in</strong>ction between ‘ion’and ‘ian’In one study three groups of childrenreceived the same amount of practice <strong>in</strong>try<strong>in</strong>g to learn the spell<strong>in</strong>g of words end<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong> ‘ion’ and ‘ian’. One group was never toldthat these end<strong>in</strong>gs <strong>are</strong> used to formdifferent types of words. They wereexpected to learn the spell<strong>in</strong>g bythemselves, through practice. The secondgroup had the opportunity to try to discoverhow the spell<strong>in</strong>g of the word-end<strong>in</strong>gsworked. They were told the rule half-waythrough the exercises. A third group wastold the rule about ‘ian’ and ‘ion’ suffixes atthe start of the tasks and then had to try touse this <strong>in</strong>formation to work out correctspell<strong>in</strong>gs. The measures used at pre- andpost-test <strong>in</strong>volved spell<strong>in</strong>g words as well aspseudo-words with ‘ion’ and ‘ian’ end<strong>in</strong>gs.Although the children <strong>in</strong> all three groupssolved the same spell<strong>in</strong>g tasks <strong>in</strong> the sameorder, only the two groups who were taughtthe rule explicitly showed consistently betterperformance than a comparison group whohad worked on a different <strong>literacy</strong> task.After these small studies, we designed aprogramme to teach children how toidentify the <strong>morphemes</strong> that composemulti-morphemic words <strong>in</strong> order to analysetheir mean<strong>in</strong>g and spell them correctly. Ourmaterials, which were delivered us<strong>in</strong>g ITwww.tlrp.orgTeac hi ng and Lear ni ng Resea rch Pro g r a m m e

Major implicationsOur re s e a rch demonstrates that knowledge of <strong>morphemes</strong> can help children learn<strong>in</strong>g tospell English words, and that it is quite easy to promote this knowledge <strong>in</strong> pupils <strong>in</strong> anattractive and <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g way. We have also shown that for the most part teachersthemselves <strong>are</strong> not explicitly aw<strong>are</strong> of the importance of <strong>morphemes</strong>, but with the help ofspecial courses can easily <strong>in</strong>corporate <strong>in</strong>struction about <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong>to their teach<strong>in</strong>g ofspell<strong>in</strong>g. We have shown that:Figure 2: Help<strong>in</strong>g children th<strong>in</strong>k aboutprefixes and how they can give a clue tomean<strong>in</strong>gFigure 3: Mak<strong>in</strong>g connections betweensuffixes, prefixes and grammatical categoriesand a game format, used a variety ofoperations, such as add<strong>in</strong>g and subtract<strong>in</strong>g<strong>morphemes</strong>, mak<strong>in</strong>g analogies, count<strong>in</strong>g<strong>morphemes</strong>, guess<strong>in</strong>g the mean<strong>in</strong>g of<strong>in</strong>vented words made with real <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong> non-exist<strong>in</strong>g comb<strong>in</strong>ations, and try<strong>in</strong>g todiscover the grammatical categories towhich words with the same <strong>morphemes</strong>belonged. Teachers and pupils enjoyedthese exercises. More than 1,000 childrenwere <strong>in</strong>volved at different stages of theresearch on the development andassessment of the programme. Theprogramme is effective <strong>in</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>gchildren’s spell<strong>in</strong>g of words whose spell<strong>in</strong>gcannot be predicted from the way theysound. It helps both children <strong>in</strong> the higherand lower ability groups. The programmealso has positive effects on children’svocabulary and provides them with a wordattack strategy that helps them analyse and<strong>in</strong>terpret novel words. Its approach iscompatible with current curriculumdemands and extends them <strong>in</strong> a valuableway.Intervention studies with teachersTo transform our re s e a rch with children <strong>in</strong>topractice, these techniques need to beadopted by teachers. We did thissuccessfully dur<strong>in</strong>g the course of this pro j e c t .Teachers were <strong>in</strong>vited to attend a 10-sessioncourse <strong>in</strong> <strong>literacy</strong>. This was off e red as aMasters module or a stand-alone unit ofp rofessional development. There were thre ema<strong>in</strong> aspects to the course: an <strong>in</strong>tro d u c t i o n• S c h o o l c h i l d ren on the whole have littlea w a reness of the morphemic structureof words or of the crucial connectionbetween <strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g• Exist<strong>in</strong>g attempts to teach childre nabout <strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g with<strong>in</strong>the NLS <strong>are</strong> scanty and those attemptsthat <strong>are</strong> made often do not deal withthe mean<strong>in</strong>g of the words or of theirconstituent <strong>morphemes</strong>.• C l a s s room <strong>in</strong>struction about<strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g does not haveto be bor<strong>in</strong>g and can be effective forboth low- and high-achiev<strong>in</strong>g pupils.• Teachers who were given theopportunity to reflect on the importanceof <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong> learn<strong>in</strong>g to spell wereable and generally will<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>in</strong>corporate<strong>in</strong>struction about <strong>morphemes</strong> <strong>in</strong>to theirspell<strong>in</strong>g lessons, and did so with goode ffect.to relevant theories and re s e a rch; thep rovision of the set of materials which wehad created for our work with children; and<strong>in</strong>volvement of teachers <strong>in</strong> the <strong>in</strong>terventionp rocess. Teachers found it challeng<strong>in</strong>g tol e a rn about a range of new techniques anduse them <strong>in</strong> their practice simultaneously butit was the co-ord<strong>in</strong>ation of theory andpractice that proved effective <strong>in</strong> pro m o t i n gtheir pupils’ success.There was little difficulty <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gteachers’ aw<strong>are</strong>ness of morphology. Of the17 teachers for whom we had data at thebeg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g and the end of the course, onlythree def<strong>in</strong>ed a morpheme fairly accuratelyat the beg<strong>in</strong>n<strong>in</strong>g but 16 out of 17 did so atthe end. At the start of the module,teachers tended to consider phonologicalaw<strong>are</strong>ness as ‘an essential foundation <strong>in</strong>the learn<strong>in</strong>g of read<strong>in</strong>g and spell<strong>in</strong>g’, but didnot refer to morphological aw<strong>are</strong>ness. Atthe end, they felt that teach<strong>in</strong>g childrenabout morphology also had importantbenefits for 7- to 11-year-olds. All but oneof the teachers reported that the coursehad changed their approaches to teach<strong>in</strong>gspell<strong>in</strong>g. Most mentioned that they wouldteach more explicit morphology, mak<strong>in</strong>gconnections between spell<strong>in</strong>g, grammarand mean<strong>in</strong>g. The pupils (n=318) ofteachers attend<strong>in</strong>g the course madesignificant ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g comp<strong>are</strong>d toT h e re is a strong case for <strong>in</strong>tro d u c i n gsystematic teach<strong>in</strong>g about <strong>morphemes</strong><strong>in</strong>to the <strong>school</strong> curriculum. Thisteach<strong>in</strong>g should be susta<strong>in</strong>edt h roughout <strong>primary</strong> <strong>school</strong>, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gsimpler examples for the work withyounger pupils and more difficult onesfor the work with older pupils.Teachers can easily recognise how<strong>useful</strong> it is to teach the connectionbetween mean<strong>in</strong>g and spell<strong>in</strong>g, andshould be given the opportunity toreflect on it when plann<strong>in</strong>g how to teachc h i l d ren about <strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g.Our classroom <strong>in</strong>terventions provide aframework for the effective teach<strong>in</strong>g of<strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> <strong>school</strong>s.The connection between <strong>morphemes</strong>and spell<strong>in</strong>g should be <strong>in</strong>corporatedalso <strong>in</strong>to the <strong>in</strong>struction that pre - s e r v i c eteachers <strong>are</strong> given about teach<strong>in</strong>gl i t e r a c y.children (346) <strong>in</strong> similar classroomsreceiv<strong>in</strong>g standard <strong>in</strong>struction. The effectsize of .50 was impressive for a whole-class<strong>in</strong>tervention delivered by teachers who werelearn<strong>in</strong>g a technique for the first time. The<strong>in</strong>tervention is quite a focused and practicalone, despite its conceptual base, and thisprobably contributed to its impact.In the year follow<strong>in</strong>g the course, one resultclarified the aspect of our <strong>in</strong>tervention thathad affected the children’s spell<strong>in</strong>g. In theautumn term, a teacher who had been onthe course did not have an opportunity touse the morphology materials. Dur<strong>in</strong>g thisterm, her new group of pupils made nogreater ga<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> spell<strong>in</strong>g than the otherchildren <strong>in</strong> the same year group. Dur<strong>in</strong>g thespr<strong>in</strong>g term she used the morphologymaterials. Her class was comp<strong>are</strong>d with aparallel class receiv<strong>in</strong>g the same amount ofadditional spell<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>struction but differentmaterials. Her morphology group madesignificantly more progress. But additionalcurriculum time was important. Both theseclasses made significant spell<strong>in</strong>g ga<strong>in</strong>scomp<strong>are</strong>d to a control class and to theirown progress <strong>in</strong> the previous term. The<strong>in</strong>gredients for change <strong>in</strong> pupils’performance appear to be teacherknowledge and dedicated teacher time withthe appropriate set of materials.Teach<strong>in</strong>g and Learn<strong>in</strong>g Research Pro g r a m m ewww.tlrp.org

Further<strong>in</strong>formationBackground <strong>in</strong>formation about teach<strong>in</strong>g<strong>morphemes</strong> and spell<strong>in</strong>g can beobta<strong>in</strong>ed from Nunes, T., Bryant, P., andOlsson, J. (2003) Learn<strong>in</strong>gmorphological and phonological spell<strong>in</strong>grules: an <strong>in</strong>tervention study. Read<strong>in</strong>g andWrit<strong>in</strong>g, 7, 289–307.A report of the work with teachers hasbeen published: Hurry, J., Bryant, P.,Curno, T., Nunes, T., Parker, M. andPretzlik, U. (2005) Teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g<strong>literacy</strong>. Research Papers <strong>in</strong> Education,20 (1), 187–206.Further journal articles report<strong>in</strong>g thisresearch <strong>are</strong> currently <strong>in</strong> preparation. Theproject website (see below) providesfurther <strong>in</strong>formation on the results, andconference presentations on the basel<strong>in</strong>esurvey <strong>are</strong> available there.A full description of the research and itsresults is provided <strong>in</strong> Nunes, T. andBryant, P. (2006) Improv<strong>in</strong>g Literacythrough Teach<strong>in</strong>g Morphemes (London:Routledge).The warrantConfidence <strong>in</strong> our conclusions can bebased on the robustness of theempirical procedures, which comply <strong>in</strong>full with the highest scientific standardsand were <strong>in</strong>formed by the longexperience of all three members of theproject team. The methods of teach<strong>in</strong>gchildren about <strong>morphemes</strong> werescrupulously tested <strong>in</strong> a tightlycontrolled laboratory situation withc<strong>are</strong>fully designed pre- and post-testsand <strong>in</strong>tervention procedures beforethey were tried out <strong>in</strong> the classroom.The lessons for the <strong>in</strong>tervention studieswere <strong>in</strong>formed by the TLRP Phase IIproject The Role of Aw<strong>are</strong>ness <strong>in</strong> theTeach<strong>in</strong>g and Learn<strong>in</strong>g of Literacy andNumeracy. They were with discussedwith the project’s Advisory Board, andwith the teachers and head teachers <strong>in</strong>the participat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>school</strong>s.All our conclusions <strong>are</strong> based onrigorous quantitative analysis, us<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>ferential statistics (e.g. ANOVA andmultiple regression). Our reporteddifferences were not simply statisticallysignificant, but also showed large effectsizes.Teach<strong>in</strong>gand Learn<strong>in</strong>gResearch ProgrammeTLRP is the largest education researchprogramme <strong>in</strong> the UK, and benefits from researchteams and fund<strong>in</strong>g contributions from England,Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Projectsbegan <strong>in</strong> 2000 and will cont<strong>in</strong>ue withdissem<strong>in</strong>ation and impact work extend<strong>in</strong>gthrough 2008/9.Learn<strong>in</strong>g: TLRP’s overarch<strong>in</strong>g aim is toimprove outcomes for learners of all ages <strong>in</strong>teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g contexts with<strong>in</strong> the UK.Outcomes: TLRP studies a broad range of learn<strong>in</strong>goutcomes. These <strong>in</strong>clude both the acquisition of skill,understand<strong>in</strong>g, knowledge and qualifications and thedevelopment of attitudes, values and identities relevantto a learn<strong>in</strong>g society.L i f e c o u r s e :TLRP supports re s e a rch projects and re l a t e dactivities at many ages and stages <strong>in</strong> education, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>gand lifelong learn i n g .Enrichment: TLRP commits to user engagement at allstages of research. The Programme promotes researchacross discipl<strong>in</strong>es, methodologies and sectors, andsupports various forms of national and <strong>in</strong>ternational cooperationand comparison.Expertise: TLRP works to enhance capacity for allforms of research on teach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g, and forresearch-<strong>in</strong>formed policy and practice.I m p ro v e m e n t :TLRP develops the knowledge base onteach<strong>in</strong>g and learn<strong>in</strong>g and collaborates with users totransform this <strong>in</strong>to effective policy and practice <strong>in</strong> the UK.Project teamTerez<strong>in</strong>ha Nunes, Peter Bryant, Jane Hurry andUrsula Pretzlik, with the collaboration of Daniel Bell,Deborah Evans, Sel<strong>in</strong>a Gardner and Jenny Olsson.Project contactProfessor Terez<strong>in</strong>ha NunesEmail: terez<strong>in</strong>ha.nunes@edstud.ox.ac.ukTelephone: +44 (0) 1856 284892/3Department of Educational Studies, University of Oxford,Oxford OX2 6PYProject websitehttp://www.edstud.ox.ac.uk/research/childlearn<strong>in</strong>g/<strong>in</strong>dex.htmlISBN0- 85473-742- 19 78 08 54 73 74 2 0March 2006TLRP is managed by the Economic and SocialR e s e a rch Council re s e a rch mission is to advanceknowledge and to promote its use to enhance thequality of life, develop policy and practice ands t rengthen economic competitiveness. ESRC isguided by pr<strong>in</strong>ciples of quality, relevance andi n d e p e n d e n c e .TLRP Directors’ TeamProfessor Andrew Pollard ❚ LondonProfessor Mary James ❚ LondonProfessor Stephen Baron ❚ StrathclydeProfessor Alan Brown ❚ WarwickProfessor Miriam David ❚ Londone-team@groups.tlrp.orgTLRP Programme OfficeSarah Douglas ❚ sarah.douglas@ioe.ac.ukJames O’Toole ❚ j.o’toole@ioe.ac.uktlrp@ioe.ac.ukTLRPInstitute of EducationUniversity of London20 Bedford WayLondon WC1H 0ALTel: +44 (0)20 7911 5577Fax: +44 (0)20 7911 5579www.tlrp.org