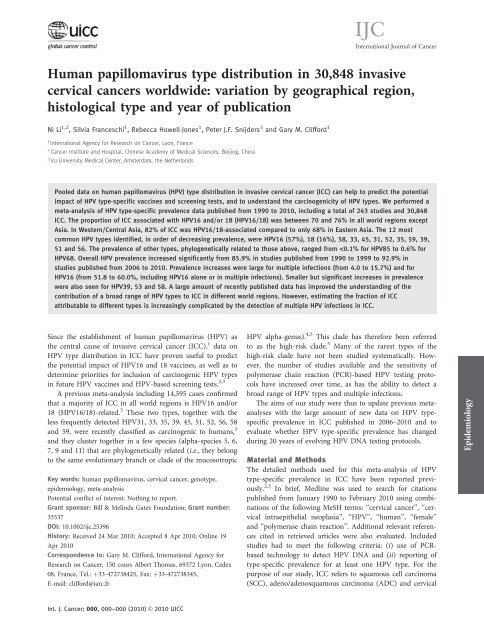

Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive ... - Zervita

Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive ... - Zervita

Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive ... - Zervita

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

4 HPV <strong>type</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>in</strong> cervical cancerEpidemiologyTable 2. Selected human <strong>papillomavirus</strong> (HPV) <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer (ICC), overall and by histological <strong>type</strong>Histological <strong>type</strong>OverallSCC 2ADCSCC vs. ADCHPV <strong>type</strong> 1 Alpha-species N % 95% CI N % 95% CI N % 95% CI p value 3Any <strong>30</strong>,357 89.9 88.2, 91.3 26,667 90.9 89.3, 92.3 3,525 82.0 78.4, 85.1

Li et al. 5EpidemiologyFigure 1. The ten most frequently detected human <strong>papillomavirus</strong> (HPV) <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer (ICC) 1990–2010, by region.Abbreviation: N: number of cases tested for the given HPV <strong>type</strong>.ICC across the Asian cont<strong>in</strong>ent, which is estimated to bearmore than half of the world’s cervical cancer burden. 6The most common <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> ICC after HPV16 and HPV18were confirmed to be consistent <strong>in</strong> all world regions and overtime, namely a comb<strong>in</strong>ation of HPV31, 33, 35, 45, 52 and 58,with few exceptions. Our present f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs are <strong>in</strong> agreementwith those from our previous meta-analysis, 3 as well as withthose from the uniformly tested samples of the IARCInt. J. Cancer: 000, 000–000 (2010) VC 2010 UICC

6 HPV <strong>type</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>in</strong> cervical cancerEpidemiologyTable 3. Selected human <strong>papillomavirus</strong> (HPV) <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer (ICC) and adeno/adenosquamous carc<strong>in</strong>oma (ADC), by yearof publication1990–1999 2000–2005 2006–2010HPV <strong>type</strong> N % 95% CI N % 95% CI N % 95% CI p for trend 1All ICCAny 7,523 85.9 82.5, 88.8 7,877 87.9 85.7, 89.8 14,957 92.9 90.8, 94.5 0.001S<strong>in</strong>gle 5,963 82.1 78.1, 85.5 5,621 80.4 77.3, 83.2 12,350 76.8 73.0, 80.2 0.010Multiple 5,963 4.0 3.0, 5.4 5,621 9.0 5.9, 13.5 12,350 15.7 12.8, 19.2

Li et al. 7Table 4. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>papillomavirus</strong> (HPV) 16 prevalence <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer by year of publication, across strata of region, specimen <strong>type</strong>and PCR primer1990–1999 2000–2005 2006–2010N % HPV16-positive N % HPV16-positive N % HPV16-positive p for trend7,662 7,871 15,210RegionAfrica 457 47.5 880 57.8 674 47.6 0.779Eastern Asia 2,357 45.7 3,283 51.7 6,011 59.3 0.009Western/Central Asia 153 64.7 373 60.6 1,525 68.5 0.215Europe 2,688 56.7 1,647 61.0 4,575 60.5 0.351North America 670 51.0 637 57.3 1,178 54.8 0.160South/Central America 1,064 51.4 890 46.3 1,056 64.7 0.026Oceania 273 59.3 161 54.0 191 52.9 0.069Specimen <strong>type</strong>Fresh/fixed biopsies 6,339 53.3 5,665 57.5 12,427 60.6 0.013Exfoliated cervical cells 1,323 44.7 2,206 47.4 2,783 57.1 0.012PCR primerGP5þ/6þ 1,155 51.2 1,925 55.1 3,026 62.2 0.036MY09/11 3,749 51.8 1,705 53.8 1,863 65.9

8 HPV <strong>type</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>in</strong> cervical cancerTable 5. Prevalence of all, s<strong>in</strong>gle and multiple <strong>in</strong>fections by year of publication, for any human <strong>papillomavirus</strong> (HPV) <strong>type</strong>, HPV16 andHPV18 1 Overall 1990–1999 2000–2005 2006–2010N % N % N % N %All ICC 12,106 1,673 2,938 7,495Any HPV-positive All 11,<strong>30</strong>7 93.4 1,529 91.4 2,733 93.0 7,045 94.0S<strong>in</strong>gle 9,766 80.7 1,479 88.4 2,470 84.1 5,817 77.6Multiple 1,541 12.7 50 3.0 263 9.0 1,228 16.4HPV16-positive All 6,929 57.2 864 51.6 1,635 55.7 4,4<strong>30</strong> 59.1S<strong>in</strong>gle 5,984 49.4 831 49.7 1,481 50.4 3,672 49.0Multiple 945 7.8 33 2.0 154 5.2 758 10.1HPV18-positive All 2,077 17.2 272 16.3 587 20.0 1,218 16.3S<strong>in</strong>gle 1,466 12.1 245 14.6 445 15.1 776 10.4Multiple 611 5.0 27 1.6 142 4.8 442 5.9ADC only 1,156 152 405 599Any HPV-positive All 1,036 89.6 129 84.9 360 88.9 547 91.3S<strong>in</strong>gle 917 79.3 129 84.9 3<strong>30</strong> 81.5 458 76.5Multiple 119 10.3 0 0.0 <strong>30</strong> 7.4 89 14.9HPV16-positive All 462 40.0 42 27.6 172 42.5 248 41.4S<strong>in</strong>gle 395 34.2 42 27.6 150 37.0 203 33.9Multiple 61 5.3 0 0.0 22 5.4 39 6.5HPV18-positive All 467 40.4 70 46.1 155 38.3 242 40.4S<strong>in</strong>gle 374 32.4 70 46.1 104 25.7 200 33.4Multiple 89 7.7 0 0.0 51 12.6 38 6.3p for trend(s<strong>in</strong>gle vs. multiple)

Li et al. 9the newer estimation of the fraction of ICC attributable tothe comb<strong>in</strong>ation of these <strong>type</strong>s (101.0%) is certa<strong>in</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>flatedby the multiple count<strong>in</strong>g of HPV <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> multiple<strong>in</strong>fections.In conclusion, the rise of the fraction of multiple <strong>in</strong>fections<strong>in</strong> ICC, which is understood to arise from a s<strong>in</strong>gle cell,poses serious <strong>in</strong>terpretation problems. Unless functional<strong>in</strong>volvement of HPV <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> multiple <strong>in</strong>fections is demonstrated,the attribution of the various HPV <strong>type</strong>s present <strong>in</strong>multiple <strong>in</strong>fections rema<strong>in</strong>s uncerta<strong>in</strong>. However, demonstrat<strong>in</strong>gwhich HPV <strong>type</strong> is functionally relevant to a tumour, byus<strong>in</strong>g techniques such as microdissection and/or detection ofE6 or E7 transcripts, rema<strong>in</strong>s difficult. 16 It is therefore<strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly challeng<strong>in</strong>g to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between cl<strong>in</strong>ically relevantand irrelevant HPV <strong>in</strong>fections and thereby to estimatethe benefits of tests and vacc<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g more or lessbroad ranges of HPV <strong>type</strong>s. 17AcknowledgementsDur<strong>in</strong>g this work, Dr. Ni Li was the recipient of an IARC postdoctoral fellowship,and Dr. Rebecca Howell-Jones was the recipient of a postdoctoralfellowship at IARC f<strong>in</strong>anced by the ‘‘Fondation Innovations en Infectiologie(FINOVI).’’References1. IARC. Monographs on the evaluation ofcarc<strong>in</strong>ogenic risks to humans, vol. 100: Areview of carc<strong>in</strong>ogens, Part B: biologicalagents. Lyon: International Agency forResearch on Cancer, <strong>in</strong> press.2. Clifford GM, Smith JS, Plummer M,Muñoz N, Franceschi S. <strong>Human</strong><strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong>s <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>vasive cervicalcancer worldwide: a meta-analysis. Br JCancer 2003;88:63–73.3. Smith JS, L<strong>in</strong>dsay L, Hoots B, Keys J,Franceschi S, W<strong>in</strong>er R, Clifford GM.<strong>Human</strong> <strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer and high-gradecervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. IntJ Cancer 2007;121:621–32.4. Schiffman M, Herrero R, Desalle R,Hildesheim A, Wacholder S, RodriguezAC, Bratti MC, Sherman ME, Morales J,Guillen D, Alfaro M, Hutch<strong>in</strong>son M, et al.The carc<strong>in</strong>ogenicity of human<strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong>s reflects viralevolution. Virology 2005;337:76–84.5. Schiffman M, Clifford G, Buonaguro FM.Classification of weakly carc<strong>in</strong>ogenichuman <strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong>s: address<strong>in</strong>gthe limits of epidemiology at theborderl<strong>in</strong>e. Infect Agent Cancer 2009;4:8.6. Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Park<strong>in</strong> DM.Globocan 2002: <strong>in</strong>cidence, mortality andprevalence worldwide [CD-ROM]. Lyon:International Agency for Research onCancer, 2004.7. Muñoz N, Bosch FX, Castellsagué X, DiazM, de Sanjosé S, Hammouda D, Shah KV,Meijer CJ. Aga<strong>in</strong>st which human<strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong>s shall we vacc<strong>in</strong>ate andscreen? The <strong>in</strong>ternational perspective. Int JCancer 2004;111:278–85.8. Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M,Giuliano AR, de Sanjosé S, Bruni L,Tortolero-Luna G, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N.Epidemiology and natural history ofhuman <strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>in</strong>fections and <strong>type</strong>specificimplications <strong>in</strong> cervical neoplasia.Vacc<strong>in</strong>e 2008;26 (Suppl. 10):K1–K16.9. Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y,Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L,Cogliano V. A review of humancarc<strong>in</strong>ogens, Part B: biological agents.Lancet Oncol 2009;10:321–2.10. Clifford GM, Rana RK, Franceschi S, SmithJS, Gough G, Pimenta JM. <strong>Human</strong><strong>papillomavirus</strong> geno<strong>type</strong> <strong>distribution</strong> <strong>in</strong>low-grade cervical lesions: comparison bygeographic region and with cervical cancer.Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2005;14:1157–64.11. Schiffman M, Khan MJ, Solomon D,Herrero R, Wacholder S, Hildesheim A,Rodriguez AC, Bratti MC, Wheeler CM,Burk RD. A study of the impact of add<strong>in</strong>gHPV <strong>type</strong>s to cervical cancer screen<strong>in</strong>g andtriage tests. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:147–50.12. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM,Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, SnijdersPJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. <strong>Human</strong><strong>papillomavirus</strong> is a necessary cause of<strong>in</strong>vasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol1999;189:12–19.13. Tawfik El-Mansi M, Cuschieri KS, MorrisRG, Williams AR. Prevalence of human<strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong>s 16 and 18 <strong>in</strong> cervicaladenocarc<strong>in</strong>oma and its precursors <strong>in</strong>Scottish patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer2006;16:1025–31.14. Clifford G, Franceschi S. Members of thehuman <strong>papillomavirus</strong> <strong>type</strong> 18 family(alpha-7 species) share a commonassociation with adenocarc<strong>in</strong>omaof the cervix. Int J Cancer 2008;122:1684–5.15. Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Dunn T,Zuna RE, Gold MA, Allen RA, Zhang R,Sherman ME, Wacholder S, Walker J,Wang SS. Multiple human <strong>papillomavirus</strong>geno<strong>type</strong> <strong>in</strong>fections <strong>in</strong> cervical cancerprogression <strong>in</strong> the study to understandcervical cancer early endpo<strong>in</strong>ts anddeterm<strong>in</strong>ants. Int J Cancer 2009;125:2151–8.16. Gravitt PE, van Doorn LJ, Qu<strong>in</strong>t W,Schiffman M, Hildesheim A, Glass AG,Rush BB, Hellman J, Sherman ME, BurkRD, Wang SS. <strong>Human</strong> <strong>papillomavirus</strong>(HPV) genotyp<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g pairedexfoliated cervicovag<strong>in</strong>al cells andparaff<strong>in</strong>-embedded tissues to highlightdifficulties <strong>in</strong> attribut<strong>in</strong>g HPV <strong>type</strong>s tospecific lesions. J Cl<strong>in</strong> Microbiol 2007;45:3245–50.17. Snijders PJ, van den Brule AJ, Meijer CJ.The cl<strong>in</strong>ical relevance of human<strong>papillomavirus</strong> test<strong>in</strong>g: relationshipbetween analytical and cl<strong>in</strong>ical sensitivity.J Pathol 2003;201:1–6.EpidemiologyInt. J. Cancer: 000, 000–000 (2010) VC 2010 UICC