BiblioAsia - National Library Singapore

BiblioAsia - National Library Singapore

BiblioAsia - National Library Singapore

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

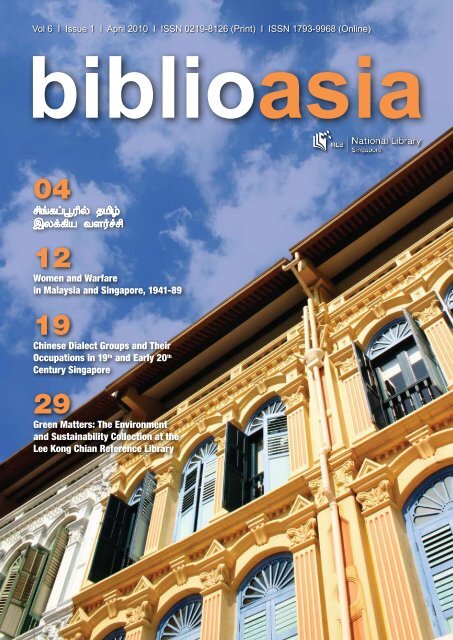

Vol 6 I Issue 1 I April 2010 I ISSN 0219-8126 (Print) I ISSN 1793-9968 (Online)biblioasia04º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢úþÄ츢 ÅÇ÷12Women and Warfarein Malaysia and <strong>Singapore</strong>, 1941-8919Chinese Dialect Groups and TheirOccupations in 19 th and Early 20 thCentury <strong>Singapore</strong>29Green Matters: The Environmentand Sustainability Collection at theLee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>

CONTENTSDIRECTOR’S COLUMNSPOTLIGHT04COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS29NEWS44º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷FEATURES3338414608A Comparative Study of FilmCriticism on <strong>Singapore</strong> Films inPost-1965 <strong>Singapore</strong> Chineseand English Newspapersand Journals19Chinese Dialect Groups andTheir Occupations in 19 th andEarly 20 th Century <strong>Singapore</strong>Green Matters: The Environment and Sustainability Collectionat the Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>Early Tourist Guidebooks to <strong>Singapore</strong>The Handbook to <strong>Singapore</strong> (1892)The Asian Children’s Collection– Multicultural Children’s LiteratureThe George Hicks Collection12Research Collaboratory Client Series:“Policy Making 2010 – Emergent Technologies”Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship:Three New Research Fellows AwardedWomen and Warfare inMalaysia and <strong>Singapore</strong>,1941-8926<strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> DistinguishedReader: Insights from DrAndrew ChewEDITORIAL/PRODUCTIONSUPERVISING EDITORSVeronica CheeWong Siok MuoiCONTRIBUTORSBonny TanGeoff WadeJaclyn TeoJoseph DawesMahani AwangMalarvele IlangovanDESIGN AND PRINT PRODUCTIONOrgnix CreativesCover: Chinatown, <strong>Singapore</strong>.EDITORNg Loke KoonNorasyikin BinteAhmad IsmailPanna KantilalSamuel SngSara PekTan Chee LayAll rights reserved. <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board <strong>Singapore</strong> 2010Printed in April 2010ISSN 0219-8126 (Print)ISSN 1793-9968 (Online)<strong>BiblioAsia</strong> is published and copyrighted in 2010 by the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board,<strong>Singapore</strong> for all contents, designs, drawings and photographs printed in theRepublic of <strong>Singapore</strong>.<strong>BiblioAsia</strong> is published by <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board, <strong>Singapore</strong> with permissionfrom the copyright owner. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publicationmay be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, for any reason or by anymeans, whether re-drawn, enlarged or otherwise altered including mechanical,photocopy, digital storage and retrieval or otherwise, without the prior permissionin writing from both the copyright owner and the publisher, except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The text, layout anddesigns presented in this publication, as well as the publication in its entirety, areprotected by the copyright laws of the Republic of <strong>Singapore</strong> and similar laws inother countries. Commercial production of works based in whole or in part uponthe designs, drawings and photographs contained in this publication is strictlyforbidden without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.While every effort has been made in the collection, preparation and presentationof the material in this publication, no responsibility can be taken for how thisinformation is used by the reader, for any change that may occur after publicationor for any error or omission on the part of the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board, <strong>Singapore</strong>.Neither the respective copyrights owners or authors or the publishers acceptsresponsibility for any loss suffered by any person who acts or refrains fromacting on any matter as a result of reliance upon any information contained inthis publication.Scanning, uploading and/or distribution of this publication, or any designs ordrawings or photographs contained herein, in whole or part (whether re-drawn,re-photographed or otherwise altered) via the Internet, CD, DVD, E-zine,photocopied hand-outs, or any other means (whether offered for free or for a fee)without the expressed written permission from both the copyright owner and thepublisher is illegal and punishable by the laws of the Republic of <strong>Singapore</strong> andsimilar laws in other countries.The copyright owner and publisher of this publication appreciate your honesty andintegrity and ask that you do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrightedmaterial. Be sure to purchase (or download) only authorised material. We thankyou for your support.Please direct all correspondence to:<strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board100 Victoria Street #14-01 <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Building <strong>Singapore</strong> 188064Tel: +65 6332 3255Fax: +65 6332 3611Email: ref@nlb.gov.sgWebsite:www.nlb.gov.sgWant to know more about what’s going on at the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>?Get the latest on our programmes at http://golibrary.nlb.gov.sg/

DIRECTOR’SCOLUMNThe eagerly awaited exhibition Rihlah – Arabs inSoutheast Asia (Rihlah means journey in Arabic)was launched at the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> on 10 April.To be held till October, the exhibition acknowledges the closeties between Southeast Asia and the Arab community. Ondisplay are photographs and artefacts ranging from personaldocuments to musical instruments many of which are on publicdisplay for the first time. Be enthralled by the rich historyand culture of the Arabs in Southeast Asia. This exhibition isdefinitely a visual feast not to be missed.The “Spotlight” article documents the development of theTamil literary scene in <strong>Singapore</strong> which has more than one hundredyears of history. Featured in the article are some Tamil literarypioneers who have contributed significantly to the growthof Tamil literature in <strong>Singapore</strong>. Some major Tamil literary worksare also mentioned in the article.The research findings of two of our Lee Kong Chian ResearchFellows, Tan Chee Lay and Mahani Awang, are publishedin this issue. Tan Chee Lay undertakes a comparativestudy of film criticism on <strong>Singapore</strong> films in post-1965 <strong>Singapore</strong>Chinese and English newspapers and journals. Film criticismplays an important role in contributing to and promotingthe local film industry. Mahani Awang looks at the role andinvolvement of women in warfare in Malaysia and <strong>Singapore</strong>from 1941 to 1989. Using both historical method and genderas analytical tools, she attempts to find out the role of womenvis-à-vis men in various activities connected to war.The different Chinese dialect groups in <strong>Singapore</strong> areassociated with certain skills and trades. A feature article byJaclyn Teo, a librarian with the Lee Kong Chian Reference<strong>Library</strong>, looks at the occupational specialisation of Chinese dialectgroups in <strong>Singapore</strong> from 1819 till the 1950s. Highlightedin the article are the dominant trades for Hokkiens, Teochews,Cantonese, Hakkas and Hainanese.Launched in April 2006, the <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>’s DistinguishedReaders Initiative aims to honour and pay tribute to prominentand learned <strong>Singapore</strong>ans whose leadership and professionalsuccess in their respective fields have propelled <strong>Singapore</strong> asa key player on the global stage, whether in government, business,academia or the arts. The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> was privilegedto have interviewed Dr Andrew Chew, Distinguished Readerand former Chairman of the Public Service Commission.Excerpts of the interview are published in this issue.Featured in this issue are three collections of the <strong>National</strong><strong>Library</strong> – the Environment and Sustainability Collection, theAsian Children’s Collection and the George Hicks Collection.The Environment and Sustainability Collection aims to informand provide insights and ideas on a broad spectrum of resourceson major environmental trends and issues such as climatechange, global warming, sustainable development, green businessand buildings and clean technology. The Asian Children’sCollection is a unique collection of more than 20,000 children’stitles with Asian content. It provides a good resource for researchersinterested in the origins of Asian-oriented children’sbooks and the influences and attitudes affecting the pattern andstages of their development. The <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> is fortunateto have received a collection of more than 3,000 books fromGeorge Lyndon Hicks – economist, author, book-lover, traveller,businessman and long-time <strong>Singapore</strong> resident. The collection’smain areas of focus are the economics, history andculture of China, Japan and Southeast Asia.Happy reading! We look forward to receiving yourcomments and feedback.Ms Ngian Lek ChohDirector<strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>biblioasia • April 20103

4Spotlightº¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢úþÄ츢 ÅÇ÷Edited BySundari BalasubramaniamLibrarianLee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong><strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>Íó¾Ã¢ À¡ÄÍôÃÁ½¢Âõáĸ «¾¢¸¡Ã¢Ä£ ¦¸¡í º¢Âý §Áü§¸¡û§¾º¢Â áĸ šâÂõBy Malarvele IlangovanSenior LibrarianProfessional Services<strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>மலர்விழி இளங்§¸¡வன்ãò¾ áĸ «¾¢¸¡Ã¢Ä£ ¦¸¡í º¢Âý §Áü§¸¡û§¾º¢Â áĸ வாரியம்“±í¸û Å¡ú×õ ±í¸û ÅÇÓõ Áí¸¡¾ ¾Á¢¦ÆýÚ ºí§¸ÓÆíÌ”, ±ýÈ À¡§Åó¾÷ À¡Ã¾¢¾¡ºý ÜüÚôÀÊ ¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢Â¢ý º¢ÈôÒõ, ¦ºÆ¢ôÒõ, «¾ý ÀÂýÀ¡Îõ ¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢¨Â ¯Ä¸ «Ãí¸¢ø ¦¾¡ý¨Á Á¢ì¸ ¦Á¡Æ¢¸Ç¢ø´ýÈ¡¸ ¿¢Úò¾¢ÔûÇÐ. «òмý ¦ºùÅ¢Âø ¦Á¡Æ¢¸Ç¢ýÅ⨺¢Öõ ¾Á¢ú §º÷ì¸ôÀðÎ, ¯Ä¸ÇÅ¢ø ¾Á¢¨ÆÈôÒÈî ¦ºöÐûÇÐ.º¢í¸ôâ÷ º¢ýÉï º¢Ú ¾£× ¿¡¼¡Â¢Ûõ, Íமார்14 ஆம்áüÈ¡ñÊÄ¢Õó§¾ ÅÃÄ¡üÚ ²Î¸Ç¢ø ÌÈ¢ôÀ¢¼ôÀðÎÅóÐûÇÐ. §ÁÖõ் தமிழ் ¿¡ðμÛõ ¦¾¡¼÷Ò¦¸¡ñÊÕì¸Ä¡õ ±É×õ, ¸¼¡Ãõ ¦¸¡ண்ட §º¡ழமண்டலத்தின் ¬ðº¢ìÌ ¯ðÀðÊÕì¸Ä¡õ ±É×õ ¾Á¢ú¿¡ðÊý ÅÃÄ¡üÚ ÌÈ¢ôÒ¸û ¦¾Ã¢Å¢ôÀ¾¡¸ ¬öÅ¡Ç÷¸û¸Õи¢ýÈÉ÷.ÍÁ¡÷ 1880-¸Ç¢ý À¢üÀ̾¢Â¢ø À¢¨ÆôÒò §¾Ê¾Á¢ú ¿¡ðÊÄ¢ÕóÐõ, þÄí¨¸Â¢Ä¢ÕóÐõ º¢í¸ôââøÌʧÂȢ ¾Á¢ú Áì¸û ¾í¸û ÀñÀ¡ðÎ ¸Ä¡º¡Ãò§¾¡Î¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢¨ÂÔõ þíÌ §ÅåýÈ¢É÷. ¸¢¨¼ì¸ô¦ÀüȬŽí¸Ç¢ý ¯¾Å¢§Â¡Î º¢í¸ôââý ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢ÂÅÃÄ¡Ú ²Èį̀È 130 ¬ñθû ÀƨÁ Å¡öó¾Ð±É ÅÃÄ¡üÚ «È¢»÷¸û ¸½¢òÐûÇÉ÷. «¾üÌ ÓýÒÀ¨¼ì¸ô¦ÀüÈ ¬Å½í¸û ²Ðõ ¸¢¨¼ì¸¡¾¾¡øþ¨¾§Â «¨ÉÅÕõ ²üÚ즸¡ñ¼É÷. þýÚ º¢í¸ôâ÷«ÃÍõ, Áì¸Ùõ ¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢ìÌõ ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âò¾¢üÌõ¦¸¡ÎòÐÅÕõ º¢ÈôÒ «¨ÉÅÕõ «È¢ó¾§¾. ¯Ä¸ò¾¢ø¾Á¢ú¿¡ðÊüÌ «Îò¾ÀÊ¡¸ º¢í¨¸Â¢ø¾¡ý ¾Á¢ú¬ðº¢¦Á¡Æ¢Â¡¸ ¯ûÇÐ.º¢í¸ôââý ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢 ÅÃÄ¡Úஇலக்கியம் ±ýÀÐ ´Õ ¿¡ðÊý ͺ⨾ §À¡ýÈÐ.²¦ÉýÈ¡ø þÄ츢Âõ «ó¿¡ðÊý ºÓ¾¡Â ¬Å½Á¡¸ò¾¢¸ú¸¢ÈÐ. ´Õ ¾É¢ ÁÉ¢¾¨ÉÔõ ºã¸ò¨¾Ôõþ¨½ìÌõ ¸ÕŢ¡¸×õ ¸¡½Ä¡õ. ÁÉ¢¾÷¸ÙைடயசÓதாய நம்பிக்கைகள், மக்களின் ÀÆì¸ÅÆì¸í¸û,ÀñÀ¡ðÎìÜÚ¸û ¬¸¢ÂÅü¨È þÄ츢Âõ À¢Ã¾¢ÀĢ츢ÈÐ.º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âõ ±ýÀÐ º¢í¸ôââýÀ¢ýɽ¢Â¢ø º¢í¸ôâÃ÷¸Ç¡ø «øÄÐ ¿¢Ãó¾ÃÅ¡º¢¸Ç¡ø±Ø¾ôÀθ¢ýÈ þÄ츢Âõ ±ÉÄ¡õ. 1870 À¢üÀ̾¢Â¢øº¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢ú «îº¸í¸û ¿¢ÚÅôÀð¼ ¿¢¨Ä¢ø ÀĦºö¾¢ò¾¡û¸û ¯ÕÅ¡¸¢ þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ìÌ Å¢ò¾¢ð¼É.þôÀ¢ýɽ¢Â¢ø º¢í¸ôââý Ó¾ø ¾Á¢úô À¨¼ôÒ ´Õ¸Å¢¨¾ áÄ¡¸ ¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾Ð.1872 ¬õ ¬ñÎ Ó¸õÁÐ «ôÐø ¸¡¾¢÷ «Å÷¸û`ÓÉ¡ƒ¡òÐ ¾¢ÃðÎ’ ±ýÈ ¸Å¢¨¾ á¨Ä ±Ø¾¢É¡÷. þк¢í¸ôââý ¬¸ô ÀƨÁÂ¡É áø ±Éî º¢ÈôÒüÈÐ.³ó¾¡ñθǢø ÁüÈ ¸Å¢¨¾ò ¦¾¡ÌôҸǡÉ`¿¸Ã󾡾¢Ôõ’, `º¢ò¾¢Ã¸Å¢¸Ùõ’ ¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾É. «¨Åº¢í¸ôâ÷ ÍôÀ¢ÃÁ½¢Â ÍÅ¡Á¢ §Áø À¡¼ô¦ÀüȨÅ¡Ìõ.¿ÂÁ¢ì¸ þì¸Å¢¨¾¸û ¬úó¾ ¾òÐÅì ¸ÕòÐ츨ÇÔõÀì¾¢ ¯½÷¨ÅÔõ ¦ÅÇ¢ôÀÎò¾¢É. þÅü¨Èî º¢í¸ôâ÷º¢. Ì. ÁÌàõ º¡ÂÒ «Å÷¸û ¾ÁìÌî ¦º¡ó¾Á¡¸¢Â`¾£§É¡¾Â þÂó¾¢Ã º¡¨Ä¢ø’ «îº¢ð¼¡÷. þóÐ츼רÇôÀüȢ ÀüȢ ¸Å¢¨¾¸¨Ç µ÷ þÍÄ¡Á¢Â÷¦ÅǢ¢ð¼Ð À¡Ã¡ð¼ò¾ì¸¦Å¡ýÚ. «ì¸¡Äõ¦¾¡ð§¼þíÌ Áì¸û ºÁ ¿øÄ¢½ì¸Óõ þÉ, Á¾ ´üÚ¨ÁÔõ¦¸¡ñÊÕó¾É÷ ±ýÀ¨¾ þÐ ¸¡ðθ¢ÈÐ.1888 þø ÁÌàõ º¡ÂÒ ±ýÀÅ÷ `Å¢§É¡¾ ºõÀ¡„¨½’±ýÈ ¾¨ÄôÀ¢ø º¢í¸ôââø Ó¾ý ӾĢø º¢Ú¸¨¾ò¦¾¡ÌôÒ áø ´ýÚ ¦ÅǢ¢ð¼¡÷. þЧŠº¢í¸ôââø§¾¡ýȢ Ӿø ¾Á¢úî º¢Ú¸¨¾Â¡Ìõ. þڸ¨¾ò¦¾¡ÌôÒ ¦ÅÇ¢¿¡ðÎ °Æ¢Â÷¸ÙìÌõ º¢í¸ôââøź¢ìÌõ ¿¢Ãó¾Ã Å¡º¢ìÌõ þ¨¼§Â ¿¨¼¦ÀÚõ¸ÕòÐô ÀÈ¢Á¡üÈí¸û, ¯¨Ã¡¼ø¸û ¬¸¢ÂÅü¨Èò¾¢Ã¢ì¸¢ýÈÉ. «ì¸¡Ä¸ð¼ò¾¢ø º¢í¸ôâÕìÌôÀ¢¨Æô¨Àò §¾Ê Åó¾ þó¾¢Â÷¸Ç¢ý ÁÉ ¿¢¨Ä, Ò¾¢ÂÀÆì¸ÅÆì¸í¸û, Ò¾¢Â ¦Á¡Æ¢¸û ¬¸¢ÂÅü¨Èô ÀüȢ«Å÷¸Ç¢ý ÌÆôÀí¸û, ÀÂõ, ±ôÀÊò ¾í¸û §Å¨Ä¨Â¾ì¸ ¨ÅòÐì ¦¸¡ûÇ §À¡¸¢§È¡õ ±ýÈ «îºõ§À¡ýȨŸ¨Ç þ츨¾¸û Å¢Åâ츢ýÈÉ.þ측ĸð¼ò¾¢ø «Îò¾Îò¾¡¸ §ÁÖõ º¢Ä áø¸û¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾É. ¿. Å. Ãí¸º¡Á¢ ¾¡ºÉ¢ý `«¾¢Å¢§É¡¾Ì¾¢¨Ãô Àó¾Â ġŽ¢Ôõ’, ¸. §ÅÖôÀ¢û¨Ç¢ý`º¢í¨¸ ÓÕ§¸º÷§Àரிø À¾¢¸Óõ’ ´§Ã ¬ñÊø (1893)¦ÅǢ¢¼ôÀð¼Ð. ¬ÃõÀ ¸¡Äò¾¢ø º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢Æ÷¸û¦¸¡ñÊÕó¾ þÄ츢 ¬÷Åò¨¾ þÐ ¸¡ðθ¢ÈÐ.ÀƨÁÂ¡É º¢í¸ôââø ±ôÀÊ À¢¨Æô¨Àò §¾Ê ¸¼ø

¸¼óÐ ¸ôÀÄ¢ø º¢í¸ôâÕìÌ ÅóÐ ¾í¸û Å¡ú쨸¨Â«¨ÁòÐì ¦¸¡ñ¼É÷ ±ýÀ¨¾ô ÀüÈ¢ ±Ç¢Â ¦Á¡Æ¢¿¨¼Â¢ø ÀÃÅÄ¡¸ «ì¸¡Ä Áì¸û ÀÂýÀÎòÐõ Á¡üÚ¦Á¡Æ¢î ¦º¡ü¸û ¸Äó¾ ¿¨¼Â¢ø ¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾ `«¾¢Å¢§É¡¾Ì¾¢¨Ãô Àó¾Â ġŽ¢’ ´Õ ¦À¡Ð Áì¸û þÄ츢Âõ±ÉÄ¡õ. þùÅ¡È¡¸ ÒÄÅ÷ þÄ츢ÂÁ¡¸×õ ¦À¡ÐÁì¸ûþÄ츢ÂÁ¡¸×õ Àì¾¢ þÄ츢ÂÁ¡¸×õ º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢úþÄ츢Âõ ÅÇ÷ó¾Ð.±Ø ¦ÀüÈ ¸¡Äõ1935-1945 ¸¡Ä¸ð¼ò¨¾ º¢í¸ôââý ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢±Ø ¸¡ÄÁ¡¸ì ¦¸¡ûÇÄ¡õ. þ¾¨Éî º£÷ò¾¢Õ󾸡Äõ ±É×õ ÜÚÅ÷. ®. §Å. þáÁº¡Á¢ô ¦Àâ¡÷«Å÷¸û ¾Á¢ú¿¡ðÊø 1920¸Ç¢ý þÚ¾¢Â¢ø ¦¸¡ñÎÅó¾ º£÷ò¾¢Õò¾î º¢ó¾¨É¸û þíÌûÇ ¾Á¢Æ÷¸ÙìÌû±Ø¨Â ²üÀÎò¾¢É. þ¾ý Å¢¨ÇÅ¡ø º¢í¸ôââø¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âò¾¢ý §À¡ìÌ Á¡Èò ¦¾¡¼í¸¢ÂÐ. Àì¾¢þÄ츢Âí¸û ºÓ¾¡Âî º¢ó¾¨ÉÔûÇ þÄ츢Âí¸ÙìÌÅƢŢð¼É. 1929 þø ¦¾¡¼í¸¢Â `Óý§ÉüÈõ’ ±ýÈþ¾Øõ 1935 þø ¾Á¢Æ÷ º£÷¾¢Õò¾î ºí¸ò¾¢ý ÌÃÄ¡¸¦ÅÇ¢ Åó¾ `¾Á¢ú ÓÃÍ’ ¿¡Ç¢¾Øõ ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âí¸ûº¢í¸ôââø ÅÇ÷žüÌ Ó츢Âì ¸¡Ã½Á¡¸ «¨Áó¾É.§ÁÖõ þ¨Å ºÓ¾¡Â ¯½÷׸¨ÇÔõ ºã¸º¢ó¾¨É¸¨ÇÔõ àñΞüÌ ¿øĦ¾¡Ú °¼¸Á¡¸«¨Áó¾É. ¿¢¨È À¨¼ôÒ¸û, ¾É¢ ÁÉ¢¾É¢ý º¢ó¾¨É¨ÂÁðÎõ À¢Ã¾¢ÀĢ측Áø «Å¨Éî ÍüȢ¢ÕìÌõºã¸ò¨¾Ôõ ÍðÊì ¸¡ðÊÂÐ.þó¾ Å⨺¢ø º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢úì ¸Å¢¨¾¸Ùõ ±Ø¸ñ¼É. `ந. பழநிேவÖ’, `º¢í¨¸ Ó¸¢Äý’ §À¡ý§È¡Ã¢ý¸Å¢¨¾¸û º£÷ò¾¢Õò¾ ¯½÷¨ÅÔõ, ÐÊô¨ÀÔõ¦ÅÇ¢ôÀÎò¾¢É. ¾Á¢ú ¿¡ðÊø ¸¡Ä¸¡ÄÁ¡¸ þÕóÐÅó¾ «ÅÄ ºÓ¾¡Âô À¢Ãɸû þíÌûÇ ±ØÀ¨¼ôÀ¢Öõ Á¢Ç¢Ãò ¦¾¡¼í¸¢É. º¡¾¢Á¾ì ¦¸¡Î¨Á,¸¢ÆÁ½ì ¦¸¡Î¨Á ÁüÚõ ®Æò ¾Á¢ú «¾¢¸¡Ã¢¸Ç¢ý«¾¢¸¡Ãò¾¢üÌ ¯ðÀð¼ ¦¾ýÉ¢ó¾¢Âò ¾Á¢Æ÷¸Ç¢ý À⾡À¿¢¨Ä, Á¾îº£÷ò¾¢Õò¾õ ¬¸¢ÂÅü¨Èì ¸Õô¦À¡ÕÇ¡¸ì¦¸¡ñÎò ¾í¸û À¨¼ôÒ¸¨Ç ¯Õš츢É÷.þÃñ¼¡õ ¯Ä¸ô §À¡ÕìÌô À¢ÈÌ ¿¡Ç¢¾Æ¡¸ò¦¾¡¼í¸ôÀð¼ `Áġ¡ ¿ñÀý’ ÀÄ ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸¨ÇÔõÀò¾¢Ã¢ì¨¸Â¡Ç÷¸¨ÇÔõ ¯Õš츢ÂÐ. þ󾸡Äì¸ð¼ò¾¢ø ¾Á¢ú ÓÃÍõ þ¾Ã þ¾ú¸§Ç¡ÎþÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ìÌô ÀÄŨ¸Â¢Öõ ¯ÚШ½Â¡¸þÕó¾Ð. §À¡Ã¢ý ¬¾í¸ò¨¾ô À¨Èº¡üÚõ Ũ¸Â¢ø ந.பழநிேவÖவின் `¾¨Ä ¦ÅðÎõ¾÷À¡÷’ ±ýÛõ ¸Å¢¨¾ƒôÀ¡É¢Ââý ¦¸¡Îí§¸¡ø¬ðº¢²üÀÎò¾¢ÂÅΨŠ¦ÅÇ¢ôÀÎò¾¢ÂÐ.þ측Äì¸ð¼ þ Ä츢Âí¸Ç¢øŢξ¨Ä§Å𨸠Á¢Ç¢÷Ũ¾¿¡õ ¸¡½Ä¡õ. ¾Á¢Æ÷¸û´üÚ¨ÁìÌô ¦ÀâÐõÀ¡ÎÀð¼ ¾Á¢ú Óú¢ý¾¨ÄÅÃ¡É ¾Á¢Æ§Åû §¸¡.¾¢Õ ¿. ÀÆநி§ÅÖº¡Ãí¸À¡½¢ «Å÷¸û,¾Á¢Æ÷¸Ù측¸ò `¾Á¢Æ÷ ¾¢Õ¿¡¨Çò’ §¾¡üÚÅ¢òÐò¾Á¢ú Áì¸Ç¢¨¼§Â þÉ ´üÚ¨Á¨ÂÔõ, þÄ츢¬÷Åò¨¾Ôõ ÅÇ÷ò¾¡÷.º¢í¸ôâ÷ ¾ýɡ𺢠¦ÀüÈ ¸¡Äò¾¢Öõ À¢ýҾɢì ÌÊÂÃÍ ¿¡¼¡¸¢Â ¸¡Ä¸ð¼ò¾¢Öõ º¢í¸ôâ÷ò¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âò¨¾ ÅÇ÷ì¸ô ÒÐ ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸û ÅÃò¦¾¡¼í¸¢É÷. §ÁÖõ 1960¸Ç¢ø `Á¡½Å÷ Á½¢ ÁýÈõ’,‘Á¡¾Å¢’ þÄ츢 þ¾ú ¬¸¢ÂÉ ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ì̯ÚШ½ Òâó¾É.;ó¾¢ÃòÐìÌô À¢ý Åó¾ ÅÇ÷;ó¾¢Ãî º¢í¨¸Â¢ø ¸Å¢¨¾ þÄ츢Âõ Á¡üÈõ ¸ñ¼Ð.º¢í¸ôâ÷ ÌÊÂú¡É ¸¡Ä¸ð¼ò¾¢ø §¾¡ýȢ ¸Å¢¨¾þÄ츢Âí¸û ÁÃÒì ¸Å¢¨¾¸Ç¡¸×õ, ÌÆó¨¾ôÀ¡¼ø¸Ç¡¸×õ ¦ÁÕÌ ¦ÀüÈÉ. ÁÃÒì ¸Å¢¨¾¸û ±ýÚ¦º¡øÖõ §À¡Ð «Ð ¡ôÒ þÄ츽ò¾¢üÌ ¯ðÀðο¼ì¸ì ÜÊ ¸Å¢¨¾¸§Ç ¬Ìõ.¸.Ð.Ó. þìÀ¡ø, ÓÕ¸¾¡ºý, Ó. ¾í¸Ã¡ºý,Àýý, ÓòÐÁ¡½¢ì¸õ §À¡ý§È¡÷ ÁÃÒì ¸Å¢¨¾¸ûþÂüÈ¢É÷. þõÁÃÒì ¸Å¢¨¾¸û, þ¨ÈÔ½÷×,¸¡¾ø, ºã¸õ ¬¸¢ÂÅüÈ¢üÌò ¾É¢òÐÅõ ¦¸¡ÎòÐôÀ¨¼ì¸ôÀðÎûÇÉ.º¢í¨¸ì ¸Å¢¨¾þÄ츢 Óý§É¡Ê¸Ùû´ÕÅÃ¡É º¢í¨¸ Ó¸¢Äýº¢í¸ôââý «Ãº¡í¸ò¾¡øஅ ங் கீ க ரி க் க ப் ப ட் ட±Øò¾¡ÇÕÁ¡Å¡÷. ¸.Ð.Ó.þìÀ¡ø ¾ý þÄ츢ÂôÀ½¢Â¢ø Á¢Ç¢Ãò¦¾¡¼í¸¢ôÀÄ º¢Èó¾ À¨¼ôÒ¸¨Çí¸ôâÕìÌ «Ç¢ò¾¡÷.þ¾ÂÁÄ÷¸û (1975),Ó¸Åâ¸û (1984),¨ÅÃì¸ü¸û (1995),¸É׸û §ÅñÎõ (2000)¬¸¢ÂÉ «Å÷ À¨¼ôҸǢøþìÀ¡ø, ¸. Ð. Ó. 2003. º¢Ä. ¸.Ð.Ó. þìÀ¡ø¸¡¸¢¾ Å¡ºõ. º¢í¸ôâ÷: Å¢ý º¢í¸ôâ÷ò §¾º¢ÂÀ¾¢ôÀ¸õ.Òò¾¸ §ÁõÀ¡ðÎì ¸Æ¸All rights reserved, Å¢ýÀ¾¢ôÀ¸õ,Å¢Õ¨¾Ôõ, `¦Á¡ñð2003.À¢Ä¡í’ (Mont Blanc)Å¢Õ¨¾Ôõ, `¾Á¢Æ§Åû’ Å¢Õ¨¾Ôõ, ¦¾ý¸¢Æ측º¢ÂþÄ츢 Ţը¾Ôõ ¦ÀüÚ சிங்கப்âர்த் ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢ÂÅÇ÷ìÌô ¦ÀÕ¨Á §º÷òÐûÇ¡÷.º¢í¸ôââø ¦¾¡ÌôÒ áø¸û «ùÅÇÅ¡¸¦ÅÇ¢ÅÃÅ¢ø¨Ä. «¾¢Öõ ÅÃÄ¡üÚì ¸ñ§½¡ð¼ò¾¢ý«ÊôÀ¨¼Â¢ø ´Õ º¢Ä À¨¼ôÒ¸¨Ç ÁðΧÁ ¸¡½Ä¡õ.¾Á¢Æ§Åû §¸¡. º¡Ãí¸À¡½¢¨Âô ÀüÈ¢ì ‘¸Å¢ìÌÄõ§À¡üÚõ ¾Á¢Æ§Åû’ ±ýÛõ ¾¨ÄôÀ¢ø Ó. ¾í¸Ã¡Í¦ÅǢ¢ðÎò ¾Á¢Æ§ÅÙìÌô ¦ÀÕ¨Áî §º÷ò¾¡÷.¿¡Åø¸Ç¢ý வளர்ச்சி¿¡Åø¸Ç¢ý ÅÇ÷ «ùÅÇÅ¡¸ò ¾Ç¢÷Å¢¼Å¢ø¨Ä. ±É¢Ûõ´Õ º¢Ä À¨¼ôÒ¸û ¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾É. º¢í¸ôâ÷ þó¾¢Âî ºã¸õbiblioasia • April 20105

§¿¡ìÌõ À¢Ã¨É¸û, º£É þó¾¢Â Áì¸Ù츢¨¼§Â²üÀð¼ ¸ÄôÒò ¾¢ÕÁ½í¸û ¬¸¢ÂÅü¨Èì ÌÈ¢òбØÐõ §À¡ìÌ þÕó¾Ð. ‘§ÅûÅ¢’ ±ýÛõ ÌÚ¿¡ÅÄ¢ø¿¡. §¸¡Å¢ó¾º¡Á¢ ¾õÓ¨¼Â н¢îºÄ¡É À¡½¢Â¢ø¬ÄÂõ ±ØôÒž¢ø ²üÀð¼ À¢Ã¨É¸¨Ç ¨ÁÂÁ¡¸¨ÅòÐ ±Ø¾¢ÔûÇ¡÷.சிÚகைதகளின் வளர்ச்சி¿¡Åø¸Ù¼ý ´ôÀ¢Îõ §À¡Ðº¢í¸ôââø º¢Ú¸¨¾¸Ç¢ýÅÇ÷ µí¸¢Â¢Õó¾Ð.§ÁÖõ Å¡º¸÷ Åð¼ò¾¢øÁ¢Ìó¾ À¡Ã¡ð¨¼Ôõ¦ºøš쨸Ôõ º¢Ú¸¨¾¸û¦ÀüÈÉ. Áñ½¢ý Á½õ¸Á¢Øõ º¢í¸ôââýÀ¢ýɽ¢î Ýú¿¢¨Ä¢øÁÉ¢¾ ¯½÷׸û, Å¡ú쨸,¾¢Õ ¿¡. §¸¡Å¢ó¾º¡Á¢ «øÄø¸û§À¡ýȨŸ¨ÇôÀ¢Ã¾¢ÀÄ¢òÐ ´Õ «üÒ¾ôÀ¨¼ôÀ¡¸î º¢Ú¸¨¾¸û¦ÅÇ¢Åó¾É.¯¾¡Ã½ò¾¢üÌ ¾¢Õ¿¡. §¸¡Å¢ó¾º¡Á¢Â¢ý‘´ðÎñ½¢¸û’, ¾¢ÕþáÁ. ¸ñ½À¢Ã¡É¢ý‘ஆÚÀòÐ À¾¢§ÉØ’, ¾¢Õ¦À¡ý Íó¾ÃáÍÅ¢ý‘±ýÉ ¾¡ý ¦ºöÅÐ?’¾¢Õ ¦ºí§¸¡¼É¢ý ‘¿¡ý´Õ º¢í¸ôââÂý’ §À¡ýȺ¢Ú¸¨¾¸û º¢í¸ôââýºÓ¾¡Âô À¢ýɽ¢Â¢øþÇí¸ñ½ý, º¢í¨¸ Á¡. ±Øò¾ôÀð¼¨Å.2006. ãýÚ ÌÚ¿¡Åø¸û. ÀÄ þÉ Á츨Ç캢í¸ôâ÷: <strong>National</strong> Arts ¦¸¡ñ¼¿¡ðÊøCouncil.±ôÀÊ þÉ ¿øÄ¢½ì¸õAll rights reserved, <strong>National</strong>Arts Council, 2006.þÕ츢ÈÐ ±ýÀ¨¾ôÀ¢Ã¾¢ÀÄ¢òÐ ¸¡ðθ¢ýÈɺ¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢úî º¢Ú¸¨¾¸û. þ¾üÌ µ÷ ¯¾¡Ã½õ`ºÀ¡Ã¢Â¡’ ±ýÛõ þáÁ. ¸ñ½À¢Ã¡É¢ý ¸¨¾Â¢ø ¾Á¢úìÌÎõÀò¾¢üÌõ ÁÄ¡ö ÌÎõÀò¾¢üÌõ þ¨¼§Â ²üÀÎõ¿ð¨Àô ÀüÈ¢ «üÒ¾Á¡¸ º¢ò¾¢Ã¢ì¸ôÀðÎûÇÐ. þôÀÊÀÄ ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸û ¯ÕÅ¡¸¢É¡÷¸û. «Å÷¸Ùû º¢í¨¸Á¡þÇí¸ñ½ý, Ó. ¾í¸Ã¡ºý, º¢í¨¸ò ¾Á¢úøÅõ,§ƒ. ±õ. º¡Ä¢ , ºí¸Ã¢ áÁ¡Ûƒõ, ². À¢. ºñÓ¸õ¬¸¢§Â¡÷ ÌÈ¢ôÀ¢¼ò¾ì¸Å÷¸û.¿¡¼¸í¸Ç¢ý வளர்ச்சி¿¡¼¸òШÈÔõ º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âò¾¢üÌô ¦ÀÕõÀíÌ ¬üÈ¢ÂÐ ±ýÚ ¦º¡ýÉ¡ø «Ð Á¢¨¸Â¡¸¡Ð. ÀÄ¿¡¼¸í¸û Å¡¦É¡Ä¢Â¢Öõ, §Á¨¼Â¢Öõ «Ãí§¸È¢É.º¢Ä ¿¡¼¸í¸û áø ¯ÕÅõ ¦ÀüÚõ Åó¾¢Õ츢ýÈɱýÀÐ ÌÈ¢ôÀ¢¼ò¾ì¸Ð. ‘ÍÅθû’ ‘º¢í¸ôââø §Á¨¼¿¡¼¸í¸û” ¬¸¢Â áø¸û º¢í¸ôââý ¿¡¼¸ÅÇ÷ì̾¢Õ À¢. ¸¢Õ‰½ý± Î ò Ð ì ¸ ¡ ð ¼ ¡ ö ò¾¢¸ú¸¢ýÈÉ. §ÁÖõ À¢.¸¢Õ‰½É¢ý ¿¡¼¸ôÀ¨¼ôÒ¸Ç¡É ‘Á¡ÊÅ£ðÎ Áí¸Çõ,’ ‘«ÎìÌÅ£ðÎ «ñ½¡º¡Á¢’¬¸¢ÂÉ º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢úþÄ츢 ¬÷ÅÄ÷¸Ç¢ý¦¿ïºí¸Ç¢ø ¿£í¸¡¾þ¼õ À¢ÊòРŢð¼É.ÌÆ󨾸û þÄ츢Âõº¢í¸ôââø ÌÆó¨¾ þÄ츢Âõ ÅÇà °¼¸í¸ûШ½Òâó¾É. ¾Á¢ú Óú¢ø Á¡½Å÷ Á½¢ÁýÈõ ±ýȾɢôÀ̾¢ 1952 Ä¢ÕóÐ ¦ÅÇ¢ÅóÐ º¢ÚÅ÷¸Ç¢ý ±ØÐõ¬ü鬀 ÅÇ÷ò¾Ð. ¸. Ð. Ó. þìÀ¡ø, ÓÕ¸¾¡ºý,¿. ÀÆ¿¢§ÅÖ, Àýý,ÓòÐÁ¡½¢ì¸õ, ¦Á.þÇÁ¡Èý §À¡ý§È¡÷ÌÆó¨¾ þÄ츢ÂÅÇ÷ìÌô ¦ÀÕõÀí¸¡üÈ¢É÷. ±É¢ÛõÌÆó¨¾ þÄ츢Âõ ¦Àâ«ÇÅ¢ø º¢í¸ôââø þýÛõÅÇ÷¨¼ÂÅ¢ø¨Ä. ´Õº¢Ä÷ ¦º¡ó¾ ÓÂüº¢Â¡ø¾í¸û À¨¼ôÒ¸¨Ç¦ÅǢ¢ðÎ ÅÕ¸¢ýÈÉ÷.¬÷. §¸. §Å½¢,`¿¡ðÎôÒÈ þÄ츢Âõ’,ÁÄ÷ŢƢ þÇí§¸¡Åý. 2003.`§¸Ç¢îº¢ò¾¢Ãì ¸¨¾¸û’,þ§¾¡ Åó¾Ð ¨¼§É¡‘º¢ÚÅ÷ ¸¨¾¸û §À¡ýÈ º¢ÄAll rights reserved,TamilBookShop.com., 2003. À¨¼ôÒ¸¨Çò ¾óÐûÇ¡÷.ÁÄ÷ŢƢ þÇí§¸¡Åý‘«õÁ¡ ±í§¸?’, `þ§¾¡ Åó¾Ð ¨¼§É¡’ ±ýÈ þÃñκ¢ÚÅ÷ ¸¨¾ô Òò¾¸í¸¨Ç ¦ÅǢ¢ðÎûÇ¡÷.þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ìÌ «Ãº¡í¸ò¾¢ý °ìÌÅ¢ôÒº¢í¨¸Â¢ø ¯ûÇ þÕ¦Á¡Æ¢ì ¦¸¡û¨¸Â¢É¡ø ¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢ìÌ «Ãº¡í¸ò¾¢ý «í¸£¸¡Ãõ ¸¢¨¼ò¾¢Õ츢ÈÐ.¾Á¢ú þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ìÌî º¢í¸ôâ÷ «Ãº¡í¸õ¦ÀâÐõ ¬¾Ã× «Ç¢òÐ ÅÕ¸¢ÈÐ. §ÁÖõ ¾Á¢ú ¦Á¡Æ¢Â¢ýÅÇ÷ìÌ °¼¸ ÅÇ÷Ôõ ¦ÀÚõ Àí¸¡üÈ¢ ÅÕ¸¢ÈÐ.º¢í¸ôââø ¦¾¡¨Ä측ðº¢, Å¡¦É¡Ä¢, ¦ºö¾¢ò¾¡û¬¸¢Â Áì¸û ¦¾¡¼÷Òò ¾¸Åø º¡¾Éí¸û ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢ÂÅÇ÷ìÌô ¦ÀâÐõ ¯¾Å¢ ÅÕ¸¢ýÈÉ. §ÁÖõ º¢í¸ôâ÷«Ãº¡í¸õ þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷¨Â °ì¸ôÀÎòÐõ Ũ¸Â¢øþÄ츢Âõ, ¸¨Ä ¬¸¢ÂÅüÈ¢ø º¢ÈóРŢÇíÌÀÅ÷¸¨Çì¸ñ¼È¢óÐ ¯Ââ `¸Ä¡º¡Ã Å¢ÕÐ’ ÅÆí¸¢ ÅÕ¸¢ÈÐ.«Ãº¡í¸ò¾¡ø ¿¼ò¾ôÀÎõ `±Øò¾¡Ç÷ Å¡Ãõ’,`º¢í¸ôâ÷ ¸¨ÄŢơ’ ¬¸¢Â ¿¢¸ú¸û ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸Ç¢ýÀ¨¼ôÀ¡üÈÖìÌ ¬¾Ã×õ °ì¸Óõ «Ç¢ì¸¢ýÈÉ. «òмýº¢í¸ôââø þÂíÌõ «¨ÁôÒ¸Ùû ´ýÈ¡É §¾º¢ÂôÒò¾¸ §ÁõÀ¡ðÎì ¸Æ¸õ º¢Èó¾ À¨¼ôÀ¡Ç÷¸ÙìÌÅ¢ÕÐ ÅÆí¸¢ ¦¸ªÃŢ츢ÈÐ.6 biblioasia • April 2010

¾¡öÄ¡óÐ «Ãº¡í¸ò¾¡ø ÅÆí¸ôÀÎõ `¦¾ý¸¢Æ측º¢ÂþÄ츢 ŢÕÐ’ º¢Èó¾ þÄ츢Âô À¨¼ôÀ¢üÌÅÆí¸ôÀÎõ ¯Ââ Ţվ¡Ìõ. ¦¾ý¸¢Æ측º¢Â¡Å¢ø¬º¢Â¡ý Üð¼¨ÁôÀ¢ø ¯ûÇ ¿¡Î¸Ç¢ý «¾¢¸¡ÃòÐŦÁ¡Æ¢¸Ç¢ø À¨¼ì¸ôÀÎõ ¾¨Äº¢Èó¾ þÄ츢Âí¸ÙìÌþùÅ¢ÕÐ ÅÆí¸ôÀθ¢ÈÐ. þó¾ô ¦ÀÕ¨Á ¾Á¢ú±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸Ç¢ø, º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢úô À¨¼ôÀ¡Ç¢¸ÙìÌÁðΧÁ ¯Ã¢ÂÐ. ¦¾ý¸¢Æ측º¢Â¡Å¢ý Üð¼ணி¢ø¾Á¢¨Æ ¬ðº¢¦Á¡Æ¢Â¡¸ì ¦¸¡ñÎûÇ ¿¡Î º¢í¸ôâ÷ÁðΧÁ. þó¾ «í¸£¸¡Ãõ ¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢ìÌì ¸¢¨¼ò¾µ÷ ¯Ââ º¢ÈôÀ¡Ìõ. º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âõ,¬º¢Â¡Å¢ý «Ãí¸¢ø þ¼õ¦ÀÚÅÐ ¾Á¢ØìÌ ÁðÎÁøÄ,º¢í¸ôâÕìÌõ ¦ÀÕ¨Á¡Ìõ.º¢í¸ôâ÷ þÄ츢Âò¾¢ý ±¾¢÷¸¡Äõ.º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âõ ´Õ áüÈ¡ñÎì̧Áø ÅÇ÷ ¸ñÊÕôÀ¢Ûõ, þýÛõ ÒШÁ¡ɺ¢ó¾¨ÉÔ¼ý Á¢Ç¢÷žüÌÅ¡öôÒ¸û ¯ñÎ. º¢í¸ôâ÷±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸û À¨¼ôÀ¡üÈøÁ¢ì¸Å÷¸û ±ýÀ¾¢ø³ÂÁ¢ø¨Ä. ÌÊÂú¢øÅÇ÷žüÌõ, Å¡úžüÌõ°ì¸ãð¼ ¿ÁÐ «Ãº¡í¸õ¾Â¡Ã¡¸Á¢Õ츢ÈÐ. ¸¢¨¼ìÌõÅ¡öô¨À ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸û¿ýÌ ÀÂýÀÎò¾¢ì¦¸¡ûǧÅñÎõ.ÀÄ þÉ ºÓ¾¡ÂÓõ,Á¾í¸Ùõ, ¸Ä¡º¡ÃÓõþÇí§¸¡, À¢îº¢É¢ì¸¡Î.2009. Á¨Æ Å¢Øó¾ §¿Ãõ.¾ï¨º: ¸¡Î À¾¢ôÀ¸õ.All rights reserved, ¸¡ÎÀ¾¢ôÀ¸õ, 2009.¦¸¡ñ¼ º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢úþÄ츢Âõ ¾É¢ò¾ý¨ÁÅ¡öóÐô ¦À¡Ä¢×¼ý¾¢¸úÅÐ º¡ò¾¢Âõ.À¨¼ôÀ¡Ç÷¸û ¬ú󾺢ó¾¨ÉÔ¼ý ºÓ¾¡Âò¨¾ ´ðÊ ´Õ ŨèÃìÌûÁðÎÁøÄ¡Ð ÀÃÅÄ¡¸î º¢ó¾¢òÐô ÀÄ §¸¡½í¸Ç¢øºã¸ò¨¾ô À¡÷¨Å¢ðÎò ¾ÃÁ¡É þÄ츢Âí¸¨ÇôÀ¨¼ì¸ §ÅñÎõ. Á¡. «ýÀƸý, À¢îº¢É¢ì¸¡Î þÇí§¸¡,¦ƒÂó¾¢ ºí¸÷ §À¡ýÈÅ÷¸û º¢í¸ôâ÷ ÝÆÄ¢ø ¾í¸ûþÄ츢Âí¸¨Çô À¨¼ì¸¢ýÈÉ÷. þÅ÷¸¨Çô §À¡ýÚ§ÁÖõ ÀÄ Ò¾¢Â ±Øò¾¡Ç÷¸û ¿¢¨È ±Ø¾ §ÅñÎõ.¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢Â¢ø ¿ýÌ §¾÷ ¦ÀüÈÅ÷¸û ¾Á¢úþÄ츢 ÅÇ÷ìÌô Àí¸¡üȢɡø º¢í¸ôââø¾Á¢ú Å¡Øõ, ¾Á¢ú Å¡Øõ Ũà ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âí¸ÙõÅ¡Øõ. º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âõ §Áý§ÁÖõ ¾É¢ò¾ý¨ÁÔ¼Ûõ ÒÐô ¦À¡Ä¢×¼Ûõ Á¢Ç¢÷ÅÐ ¾¢ñ½õ.TAMIL LITERARY DEVELOPMENT IN SINGAPORE<strong>Singapore</strong>’s Tamil literary development has more than ahundred years of history. Tamil-speaking Indians arrived in thisregion in the 18th and 19th centuries and brought with them theTamil language. Over the years, the Tamil community becamea clearly distinguishable ethnic group within the <strong>Singapore</strong>Indian community. Tamil language attained a high status in thelives of the early settlers. The Tamil diaspora has developed anaspiration to nurture Tamil as a vital language that links themto their culture.The recognition of Tamil as one of four national languagesin <strong>Singapore</strong> gave the Tamils an intrinsic satisfaction. TheTamils developed the language’s literary status in <strong>Singapore</strong>over a span of hundred years in several aspects of Tamilliterature -- poetry, novels, short stories and drama. The Tamilliterary scene in <strong>Singapore</strong> is more than literature. It beganas a movement in the early days with the renaissance of theTamil language in <strong>Singapore</strong>. Prolific Tamil writers contributedto the development and status of Tamil literature in <strong>Singapore</strong>.There is certainly much potential for new and emerging writersto contribute to the Tamil literary development in <strong>Singapore</strong>.¬¾¡Ãì ÌÈ¢ôÒ¸ûÒò¾¸í¸û1. Ilangovan Malarvele. (2001). <strong>Library</strong>provision to the Tamil communityin <strong>Singapore</strong>. <strong>Singapore</strong>: NanyangTechnological University, School ofComputer Engineering.Call no.: R SING q027.63095957 ILA2. Centre for the Arts <strong>National</strong> Universityof <strong>Singapore</strong>. (2002). Conference onTamil literature in <strong>Singapore</strong> andMalaysia, 7 & 8 September 2002<strong>Singapore</strong>: <strong>National</strong> University of<strong>Singapore</strong>.Call no.: RSING q894.811471 CON3. Seminar Conference on TamilLanguage and Literature in<strong>Singapore</strong>, & Mani, A. (1977).º¢í¸ôââø ¾Á¢Øõ ¾Á¢Æ¢Ä츢ÂÓõ:¬öÅÃí¸ Á¡¿¡Îì ¸ðΨøû.º¢í¸ôâ÷ : º¢í¸ôâ÷ Àø¸¨Äì¸Æ¸¾Á¢úô§ÀèÅ.Call no.: RSING 494.81109595 SIN4. Ä£ ¦¸¡í º¢Âý áĸò¾¢ý º£Ã¢Â¾Á¢úò ¦¾¡ÌôÒ (2008). º¢í¸ôâ÷ :The Lee Kong Chian Reference<strong>Library</strong>, <strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong> Board, 2008.Call no.: RSING 025.218755957 LIK5. ‚ÄŒÁ¢, ±õ. ±Š. (2005).º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢Âõ ¬ÆÓõ«¸ÄÓõ. ¦ºý¨É : ÁÕ¾¡.Call no.:RSING 894.811109 SRI6. º£¾¡Ã¡Áý, ¾. (1996). º¢í¸ôââø¾Á¢ú º¢Ú¸¨¾. ¦ºý¨É :þħ¡ġ ¾ýɡ𺢠¸øæâ.Call no.: RSING q894.811371 SEE7. Å£ÃÁ½¢, «. (ed.) (2007). º¢í¸ôââø¾Á¢ú¦Á¡Æ¢ ¾Á¢ú þÄ츢 ÅÇ÷1965-1990 : Tamil language andliterature in <strong>Singapore</strong> : 1966-1990.Call no.: RSING 494.811 SIN8. þÇíÌÁÃý, þá. (2000).§¾Å§¿Âô À¡Å¡½÷. ¦ºý¨É :¾¢Õ¦¿ø§ÅÄ¢, ¦¾ýÉ¢ó¾¢Â¨ºÅº¢ò¾¡ó¾ áüÀ¾¢ôÒì ¸Æ¸õ.Call no.: R 494.811092 ILA9. º¢ÅÌÁ¡Ãý. (2001). º¢í¸ôâ÷ò ¾Á¢úþÄ츢Âõ : º¡¾¨É¸Ùõ±¾¢÷¸¡Äò ¾¢ð¼í¸Ùõ. º¢í¸ôâ÷ :Å¡½¢¾¡ºý À¾¢ôÀ¸õ.Call no.: RSING 894.811472 SIV10. º¢ò¾¡÷ò¾ý. (2000). ¾Á¢ú Å¡Øõ.¦ºý¨É : ¿÷Á¾¡ À¾¢ôÀ¸õ.Call no.: RSING 894.811472 SIDbiblioasia • April 20107

Table 1<strong>Singapore</strong> Films Produced After 19651965196719691971197319751977197919811983198519871989199119931995199719992001200320052007Number of films per yearDEFINITION OF A SINGAPORE FILMDefining a <strong>Singapore</strong> film has always been a tricky issue. Onewould expect <strong>Singapore</strong> cinema to be locally rooted, to reflectthe various ethnicities and languages of <strong>Singapore</strong> and capturethe different themes of local lifestyles. However, since thebirth of <strong>Singapore</strong>’s film industry, a key characteristic of thefilm industry is the use of talents from different countries andcultural backgrounds. Both Shaw and Cathay-Keris’ early filmsfeatured casts and crews of talents recruited from China andIndia. Recent films have once again proved that “home-grown”or local films might not necessarily be filmed, produced or performedby locals. This is a situation that is fast becoming thenorm in a rapidly globalised world. “Made-by-<strong>Singapore</strong>” 3 filmsare defined as “made with <strong>Singapore</strong> talent, financing and expertisebut not necessarily entirely made in <strong>Singapore</strong> or madefor the <strong>Singapore</strong> audience only” 4 . Though it was commentedthat “none of these films, however, contributed to having a <strong>Singapore</strong>identity on screen” 5 , these co-productions have allowed<strong>Singapore</strong> to be placed on the global stage of the cinematicindustry. Moreover, such international co-productions which involveseveral countries are increasing worldwide, and it hasbecome increasingly difficult to draw a clear line as to whichcountry a film should be credited. Film historiographers are“witnessing a weakening, if not the demise, of the traditionalconcept of ‘national cinema’, defined by territory, language anda homogenous culture.” 6While it may not even occur to most local audiences thatthe films they are watching are “Made-by-<strong>Singapore</strong>” films,such films are imperative for <strong>Singapore</strong> to move towards gaininginternational exposure and recognition. Besides, <strong>Singapore</strong>companies learn and benefit through their experiences ofworking with established overseas film production companies.Thus, this study will include film criticism on films that were producedlocally, and “Made-by-<strong>Singapore</strong>” films. As 1991 marksthe revival of <strong>Singapore</strong>’s film industry (refer to Table 1), itcomes as no surprise that film criticisms and articles have increasedsignificantly since then, and which are reflected in thedata collected below.DATA COLLECTIONThis analysis is based on various local film reviews collectedmainly from both local English and Chinese newspapers, andto a lesser degree, local journals.This study comprises a comprehensive list of <strong>Singapore</strong>feature films. Short, non-commercial films with limited or no release,digital films or other non-theatrical films are excluded, aswell as the various reviews in Chinese and English on featurefilms. However, there are some limitations in this collection.First, not all films have both Chinese and Englishcommentaries, thus it is impossible to perform an exact film-tofilmcomparison. Second, during the period of data collection,two new newspapers – My Paper and Today – have surfaced,and their form of writing and critique are very different in stylecompared with the traditional ones found in Lianhe Zaobao orThe Straits Times, hence affecting the comparability of data collated.Third, I have chosen to implement a general trend analysisinstead of a film-by-film analysis for this report. This is becausea general trend analysis will allow us to identify the evolvingtrends and mitigate the fact that different films have differentnumbers of reviews, or may lack either Chinese or English reviews.Fourth, although a number of newspapers/journals ratefilms, I have chosen not to take these ratings into considerationwhen comparing the reviews. This is because these ratings arebased on varying grading scales. In addition, there are manynewspapers that do not carry any ratings. Lastly, there are alarger number of English reviews than Chinese reviews, simplybecause there are more English newspapers and journals thanChinese ones.In total, this report focuses on the data of 89 feature filmsstarting from 1991 to 2008. Correspondingly, there are a totalof 237 reviews collected and researched; of these, 69 areChinese films reviews and 168 are English reviews.All rights reserved, OxfordUniversity Press, 2000.ANALYSIS OF DATAEnglish Film Reviews Appear to be More Encouraging thanChinese Film ReviewsIn general, both Chinese and English reviewers have, over theyears and especially after the 1990s, given <strong>Singapore</strong> filmsrather negative reviews. However,English film reviewersappear to be relatively moreencouraging than Chinesefilms reviewers. Interestingly,many of the Chinese film reviewsbefore 1965, in comparison,were more encouragingin nature as they sympathisedwith local filmmakers while acknowledgingthe difficult filmmakingcircumstances. 7 Thismay explain why some readersmay still hold the perceptionthat Chinese film criticismis more forgiving or positive.biblioasia • April 20109

An example is the film The Leap Years. Two Lianhe Zaobaoreviewers on the film unanimously gave it bad reviews. 8 Thereview published in the Today new paper, however, was notgood but still encouraging. It ended off with “Nice effort, hope tosee more good - if not better - work in the future”. 9 The effortin producing the film has been clearly acknowledged, althoughthe results may speak otherwise.One explanation for such a difference in treatment by Englishand Chinese reviewers may be the difference in culturesbetween the West and the East, or correspondingly, the English-speakingand Chinese-speaking communities in <strong>Singapore</strong>.In the West, failure or occasional mistakes seem to bemore acceptable and thus people are more encouraging towardsfailures. However, in the East, mistake or failure is moreoften frowned upon.Chinese Film Reviews Include Both Entertainment andArtistic IndexesIn many of the Chinese Film Reviews by Lianhe Zaobao, thereare both entertainment and artistic ratings for the films. This isa more balanced and comprehensive form of reviewing films.First, English film reviewers generally give only a singular overallfilm review, which may not do justice to the film. Audiencesfrequently simply judge a film on the overall film rating, regardlessof what the rating is based on. For example, a commercialfilm might not have a high artistic value, but is still veryentertaining for the mainstream audience. By separatingthe artistic factor and entertainment factor of the film, audiencesare better able to judge if a local film would suit theirviewing susceptibilities.One prominent example is the review of Jack Neo’s I NotStupid Too in the Business Times. The overall review washighly negative, save for one sentence that acknowledged thatit would have its target mainstream entertainment audience.However, with the film getting an overall rating of C-, it is possiblethat readers would not pick up this line but merely glanceat the overall rating before moving on to the next movie rating.On the other hand, although the Lianhe Zaobao reviewercommented that the movie was overtly “preachy” and awardedit a mere two stars for its artistic factor, it still rightly gave itthree stars for its entertainment factor 10 . Hence audiences arebetter informed, and those who weigh entertainment over artistrywould still consider watching the film. In this scenario, it iscertain that the Lianhe Zaobao’s star ratings would stand outmore than the Business Times’s one-liner that praised the film’sentertaining factor.Having a two-tier rating system would project a morebalanced view of the film production, and further offer reviewreaders an alternative perception of the different emphasesundertaken by local films. Of course, it is not to say that artisticand entertainment factors are mutually exclusive, but thereare certainly different emphases as exemplified in many localproductions, such as the abovementioned Jack Neo’s film. Furthermore,it should not come as a surprise that top box officeperformers, such as I Not Stupid, are high in entertainmentvalue but low in the artistic department; this co-relationship isapparently more palpable with the introduction of an entertainmentclassification system. In addition, the two-tier rating, in away, also balances the comparatively more negative criticism ofChinese reviews as mentioned in the preceding section.MORAL VALUESChinese film reviewers tend to stress more on moral-relatedthemes brought up by the films in their reviews compared withto English film reviewers. This is likely because Chinese cultureplaces more emphasis on advocating moral values andtheir various manifestations, including how they are portrayedin films. The emphasis on moral values in <strong>Singapore</strong>’s Chinesefilm reviews has been prevalent since the emergence of Chinesefilms. Much evidence can be found in <strong>Singapore</strong> Chinesenewspapers during the 1950s to 1970s with the beginning ofthe popularity of local Chinese film productions.A recent example of such an emphasis can be seen in thediffering Chinese and English film criticism and reviews on RoystonTan’s 15. The English reviewers for this film focused oncharacter development, Tan’s filming techniques and effort. 11However, the Chinese critics for this film went a step furtherto discuss the injustice in our society in general. One articleeven commented on how society needed to improve its treatmentof marginalised teenagers and how the education systemcould improve to cater to these teens, 12 turning the review intoan educational doctrine and a social commentary as well asa film criticism.The above example illustrates the trend of Chinese filmreviews focusing more on moral values than English filmreviews, a phenomenon that runs parallel to the Chinese traditionof wen yi zai dao (the text is the carrier of the Way, or themoral values).CONCLUSIONWith the current revival of <strong>Singapore</strong>-made-films, it is importantthat a study is conducted to analyse the trends of what local filmreviewers are writing about our local films.First, it would be useful for film-makers to understand andeven utilise these trends as film-making is never only aboutfilming the film itself; it is a comprehensive project. Producersof <strong>Singapore</strong> films could make use of the identified trendsto target varying segmentsof the population and appealto different languagespeakingaudiences. With thisinclusion, the film wouldalso resonate with its target<strong>Singapore</strong>an community.Second, the average filmgoermay wish to understandcontemporary local film trendsand biases in making aninformed choice in choosing afilm to view.All rights reserved, RoystonTan, 2003.Third, for scholars whoare doing in-depth research10 biblioasia • April 2010

elationship with the enemy (Buccheim, 2008). As a result thesemothers took their secret to the grave.Overall, Malayan women, irrespective of their background,race or religion, suffered and endured dire hardship during theJapanese Occupation in 1942-45. Rapes had taken place beforethe eyes of their own family. Many survived the ordealby disguising themselves as men and smearing their faceswith mud and charcoal to make themselves unattractive to theJapanese soldiers (Sybil, 1983).WOMEN GUERILLASSince time immemorial, war with its masculine nature, isdefined as a male activity, while the culturally female biologyof women and motherhood means women do not takepart in war. The exclusion of women from war and organisedviolence was a result of the general exclusion of women fromthe formal societal apparatus of power and coercion and theirinvolvement in motherhood (Pierson, 1987). This polarisationsubsequently creates gender differences – with war and publicdomain being a male preserve, while the women became anatural symbol for peace, the home and the protected society(Macdonald, 1987).However, besides being war-victims, women did notdistance themselves from the resistance movement in their locality.In the 1940s and 1950s the call for revolution issuedby both the Hukbalahap guerillas in Luzon and the Viet Minhin North Vietnam, for instance, saw many women enteringthe war zone. In Malaya and <strong>Singapore</strong>, the signing of theHat Yai Peace Accord in 1989 between the Malaysian governmentand the MCP which ended the 40-year guerilla warfor the first time brought to the surface the story of women involvementin underground activities and the guerilla war. Subsequently,most of them settled in the four “peace” villages insouthern Thailand which was opened by courtesy of the Thaigovernment. Sixteen of the women were interviewed by AgnesKhoo and became the main source of Life as the RiverFlows. Khoo concludes that women, from different educationaland social backgrounds joined the movement as “a formof rebellion against feudalistic, patriarchal oppression theyexperienced as young women”(Khoo, 2004).Unknown to Khoo, manywomen had joined or followedtheir husbands, friends,relatives or lovers to join theguerillas without themselveshaving any understanding ofthe communist objectives/ideologies, but who neverthelesswere impressed withthe MCP leaders who alwaysharped on British bias and discriminationagainst the poorAll rights reserved, StrategicInformation ResearchDevelopment, 2004.and women. Some of them,especially those who hadjoined after the MCP relocatedto the Malaysia-Thai border in 1953 (referred here as thesecond generation), did so due to poverty; they believed lifewould be much better if they joined the guerillas becauseeverything was provided for. After the relocation, which wasmade due to security reasons, access to food sources, whichwas the major problem for the MCP guerillas during the Emergency,had improved considerably because there was supportfrom the local villagers (Ibrahim Chik, 2004). Undoubtedly,some were coerced to do so (Xiulan, 1983). There were casesin which women were kidnapped and taken to the jungle, suchas the case of the 84-year-old Rosimah Alang bin Mat Yen fromKampong Gajah, Perak. Rosimah had spent 52 years of herlife living with the communists after she was kidnapped whileworking on the padi field in Changkat Jering in Manjong district,Perak, at the age of 17 (Utusan Melayu, 30 May 2009).The understanding of communist ideology and militarystruggle was more discernible among the first batch of womenguerillas (those who had joined before the MCP withdrawal tosouth Thailand) who were born during the British colonial periodand had witnessed the colonial domination in Malaya. The earliestinvolvement of Malayan women in the anti-colonial movementhad taken place in the 1930s. The Japanese invasion ofChina in 1937 led the MCP to mobilise the Chinese regardlessof gender into the anti-Japanese movement which becamemore organised during 1941-45. The women specially targetedwere those with education; they were then subjected to the occasionalcommunist propaganda (Suriani, 2006). Initially theChinese women became underground members of the MCP orthe Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), acting ascouriers, assisting the communists in their propaganda work,purchasing food for its armed forces and carrying out subversiveactivities. Chapman, during three-and-a-half years of livingwith the guerillas in the Malayan jungle as liason officer with theMCP, dubbed the MPAJA girls as great fighters who were committedto fighting the Japanese and were never afraid to holdguns. He related one case: when the Japanese ambushed MCPleaders during a meeting near Kuala Lumpur; a girl emergedas an unlikely heroine firing at the Japanese with her tommygunto enable the men to escape until she was shot (Chapman,1963). By the end of the Japanese Occupation, MCPpropaganda had succeeded in bringing about the involvementof women into their armed forces and to continue the struggleagainst British colonial rule. Through educated Chinese womencomrades, the MPAJA and MCP struggles were extendedto the Malay villages where the anti-Japanese feeling wasstrong (Abdullah C.D, 2005).Compared with the Chinese community – which putkinship relations and friendship network above everything – thatprovided family members or close friends who had joined theguerilla movement with all kinds of support (Stubbs, 2004),the majority of Malays viewed Malay involvement in the radicalmovement as against Islam and many stayed away. Familieswhich had members openly involved in such activitieswere often looked at with deep suspicion. In the end, manydid join secretively the guerilla movement. Many Malay womenwho joined the guerilla movement were former members ofbiblioasia • April 201013

the Angkatan Wanita Sedar (AWAS), the women wing of theMalay <strong>National</strong>ist Party (MNP). These women had their ownphilosophy and were pursuing aggressively the liberation ofwomen from feudal oppression and negative social practices(Ahmad Boestamam, 2004). When the British banned all radicaland leftist movements like MNP, Pembela Tanahair (PETA),Angkatan Pemuda Insaf (API) and AWAS in 1948, most of theradical Malays joined the MCP guerillas, including ShamsiahFakeh and Zainab Mahmud, the leader and secretary of AWAS,respectively. This benefited the MCP enormously as thesewomen were then widely accepted as “heroine” (srikandi)with their fluent and confident articulation, educational(religious) background, strong fighting spirit and unfazed by guns(Shamsiah, 2004).WOMEN COMRADES AT WORKHistory has shown that each guerilla war has its own specificcharacteristics. However, a comparison among different guerillawars shows that these wars do share some common traits.Like the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), femaleMCP cadres generally occupied a lower position in most of themilitary actions orchestrated by the party. Combat operationswere normally handled by men and this became an impedimentfor women to climb to higher positions in the party hierarchyas combat experience was often taken into consideration forpromotion (Hilsdon, 1995). The belief among female comradesthat only those who were brave and intelligent could climb theladder of success within the organisation was quite prevalent.This statement is quite true if we look at the “success” storyof well known MCP women leaders like Shamsiah Fakeh andSuriani Abdullah or Eng Ming Ching before her marriage toAbdullah C. D., the commander of the Malay Regiment in theMCP – the 10 th Regiment – in 1955. Starting as an MCP memberin Ipoh in 1940, the urban-educated Suriani, who had foughtfor the liberation of Malaya (from the British) and also for theliberation of women, began the rapid climb in the MCP whenshe was entrusted to lead a propaganda team in Ipoh, and laterin <strong>Singapore</strong>, and was directly responsible for the relocationof the 10 th Regiment from Pahang to the Malaya-Thai borderin 1953-54. The highest position Suriani had held was that ofcentral committee member of the MCP (Suriani, 2006). Hercharismatic way in handling the tasks and settling the problemsgiven to her and her wide experience in wartime had led herto hold many important appointments within the MCP (RashidMaidin, 2005). In other words, her marriage to the regimentalcommander was a mere coincidence. For Shamsiah, althoughit was not clear what her rank was within the MCP, her leadershipwas groomed by leaders of the 10 th Regiment who werealso former colleagues from the MNP, with the aim to attractmore Malay women to join the movement (Dewan Masyarakat,August 1991).Before the MCP relocated to south Thailand, womencomrades, although their exact number was not known, formedan important part of the fighting strength of the MCP, with afew heading platoons and fighting units. Interestingly, AbdullahC.D. (2007) viewed those women who had perished in theanti-colonial struggle as “Srikandibangsa” (flowers of thenation), a label that was neveraccorded at the time by anyother Malayan political movementto their women wing.They were also involved in the“long march” towards the Malaya-Thaiborder in 1953 whichmany MCP members dubbedthe highest struggle when theyhad to march from one placeto another through thick jungleand mountainous terrain, oftenat the risk of ambush by colonialforces, handicapped byshortage of arms, ammunitionAll rights reserved, StrategicInformation ResearchDevelopment, 2009.and food, and without the support of the Orang Asli and Chinesesquatters who were moved to “New Villages” following theimplementation of the “Briggs Plan” in 1950. 5 The journey itselftook a year and six months to complete (Apa khabar OrangKampong / Village People Radio Show, 2007). For female comrades,they suffered more especially those who were pregnant,such as the case of Zainab Mahmud (Musa Ahmad’s wife) 6 whowas at an early stage of pregnancy when the long march began(Aloysius, 1995). During this testing period, all hygienic needsduring birth or menstruation were secondary with jungle plantsused widely to stop or delay this biological process while somewomen stopped menstruating due to the hardship. These plantswere also used to facilitate abortion or to prevent hunger. 7LIFE IN THE GUERILLA CAMPSAs stressed by Becket (1999), the word “guerilla” connotes warand wartime conditions in difficult terrains like mountain andjungle. Being well versed with the local environment providesmobility to the guerillas who favours “hit-and-run” tactics thatwould inflict damage. It also provides time and opportunityto evade the enemy. Guerillas also tend to enjoy local support,especially those living in the jungle, although at timesthis was secured through terror tactics which were a necessityso as to prolong the struggles (Beckett, 1999). This definitionfits the nature of the MCP struggles. Its tactics of “attackand quick withdrawal” and “hide and survive” becamethe main feature of the MCP guerilla war which enabled it tosurvive until 1989. The MCP guerillas lacked both arms andfood. Hunger and starvation were part of their lives and theyalso had to be constantly on the run and never camped forlong in one place (Ibrahim Chik, 2004; Apa Khabar OrangKampong, 2007).Under this stressful and uncertain condition, both the MPAJAand MCP female guerillas lived their everyday life together withmale comrades. During stressful times, such as the JapaneseOccupation (1941-45) and the Emergency (1948-60) there wasno clear boundaries or lines between gender especially duringwartime as both male and female comrades had to combinetheir collective energy to ensure victory. Like the males,14 biblioasia • April 2010

female combatants underwenta similarly difficult life; they hadto abide by party discipline,undertake specific duties inthe camps such as sentry duty,transporting food which manyfemale comrades claimed asthe most difficult task (Xiulan,1983), cooking and nursing,besides attending militarytrainings and political courses.They were also exposed tooffensive measures by Japaneseintelligence apparatusand later British security forcesAll rights reserved, ObjectifsFilms, 2007.and were liable to be killed if caught by the enemy as reportedin the Straits Echo and Times of Malaya between the late 1940sand early 1950s.Moving to urban guerilla warfare in <strong>Singapore</strong> (<strong>Singapore</strong>became the main base for propaganda work), the colonial responsesaw the arrests of many women including a Chinesewoman who was responsible for directing all the MCP activitiesin <strong>Singapore</strong> (CO 1022/207). Many were also caught bythe <strong>Singapore</strong> authority for their involvement in the “anti-yellowculture” campaign of the 1950s which saw the active involvementof the <strong>Singapore</strong> Women Federation (PRO 27 330/56).The campaign was directed against imported culture which corruptedthe individual and public moral but was perceived by thecolonial government as communist propaganda to raise politicalawareness in the intellectual class (Harper, 1999).Even though their job seemed to be equal to that of themen’s, some of the former female guerillas claimed womenwere given comparatively easy tasks due to their physical built.Perhaps this refers to those from the second-generation combatantswho saw fewer armed skirmishes and the women weregiven tasks such as sewing, breeding animals and nursing aswell as tasks related to the kitchen; these job were less demandingwhereas going to war was preferably given to men.Except for Chang Li Li, most of the women interviewed (mostof them were from the second generation of MCP combatants)claimed they were never involved with any armed skirmishesand that women would be the last to be given weapontraining compared with the men in their camp. They admitted thecombination of bravery and intelligence would certainlyenhance (in the eyes of their superior) the female cadres’opportunity for success (namely, promotion) and to take partin military operations.While war might break down gender boundaries especiallyduring stressful times, and women were able to live in thehostile jungle, in reality, there was little to separate the womenguerillas from womanhood or the emotion of motherhood. Ofinterest are their love life (to be in love and to be loved), marriage,procreation and children. Each camp conducted its everydaylife in accordance with its own rules. Interestingly, whilethe Communist Party of the Philippines’ (CPP) practised a moreliberal policy on sexual matters which created problem to themovement by allowing marriage and, in the end, many femaleCPP were engrossed in looking after their family while war becamethe responsibility of the men (Hilsdon, 1995), the MCPseemed to have a stricter general policy about family life withinthe camp although, towards the end of the struggle, this policybecame more lenient. Marriage was allowed in most MCPcamps but during the Japanese Occupation, husband and wifewere not allowed to work in the same camp to avoid sexualcomplications. As reported by Force 136 (during the liaison withthe MPAJA), these matters were unheard of during their waragainst the Japanese (Chin & Hack, 2004). This complicationbecame common during the Emergency and thereafter withcertain camps putting up a strict policy with regards to love,marriage and pregnancy. The 8 th Regiment in Natawee district,for instance, prohibited its women cadres to be pregnant; and iffound to be so they were forced to have an abortion.As the hostile jungle and wartime condition were notsuitable to raise children, most camps had in place a ruling ofgiving away babies to local villagers. Again the female cadreshad to face enormous emotional struggles to part with theirloved ones. Although some interviewed women tried to hidetheir real feelings at the time of their involvement with the guerillasby saying they did not regret what they had gone through,there were women who refused to think or remember their lifein the jungle, especially when asked about the separation withtheir children. Others simply could not resist motherhood andmanaged to escape from the camp. The 68-year-old Khatijah,who was interviewed in March 2009 in Betong, south Thailand,claimed many women had to endure the feeling of sadnessupon leaving their family behind but did not have the courage toleave camp for fear of possible punishment by the MCP. Somefelt miserable at the time of separation with their babies but relentedas the safety of the children became their main concern(I Love Malaya, 2006). The most tragic incident befell ShamsiahFakeh when she was accused of killing her own baby in thejungle, an accusation, which she claimed was meant to smearher reputation, that she had repeatedly refuted in her memoir.In the memoir she asked her readers “as a nationalist fighter,could a mother kill her own child?” (Shamsiah, 2004: 72).The accusation of killing her son (in the case of ShamsiahFakeh) is probably the only case of its kind in the history of femaleguerillas in the MCP. But the problem of illicit sex, whichled to unwanted pregnancywas nothing new in guerillalife. Sometimes it also involvedleaders of the movementwhich led to morale decline inthe party. Some party membersregarded illicit love affairsas a serious problem thatstarted when the MCP tried tostrengthen the party after thewithdrawal to south Thailandby “accepting newcomers”(men and women) to the party,mostly local Thais. As thereAll rights reserved, ComstarEntertainment, 2006.biblioasia • April 201015

was no clear method to controlrecruitment, the MCP failed todifferentiate the “good guys” fromthe “bad guys”. There were alsomembers who believed womenwere manipulated as a tool tosabotage the MCP; these womenwere sent to create havoc by usingillicit love affairs to ensure thatleaders were engrossed in thisdistraction to the detriment of thepolitical struggle and ideologicalpurity (Ibrahim Chik, 2004: 202).Besides the issue of intimate relationship,MCP members hadalso claimed the enemy (Thaigovernment) had used women topoison their leaders through foodas women were in control of thekitchen. There were many casesof sabotage by poisoning whichwere highlighted in the memoirsof MCP leaders. 8Spies (including women spies) who had infiltrated theMCP had caused considerable chaos among party membersat the end of the 1960s. In its effort to eliminate sabotagethe MCP conducted a rectification campaign to identifyand capture spies. Orchestrating these efforts were afew leading figures of the North Malaya Bureau, including afemale leader by the name of Ah Yen who admitted to usingtorture to get the truth from those arrested. This campaignsaw many women caught and punished on suspicion ofbeing spies (Bei Ma Ju Po Huo Di Jian Zheng Xiang, 1999). InMembers of the 8 th Regiment. Photo courtesy of Mahani Awang.1968, the rectification campaign in the 12 th Regiment saw 35members massacred, 200 others “exposed and criticised” andanother 70 sacked from the party. The same drive was targeted atthe 8 th regiment.The drive to capture spies in the MCP created cracks in themovement as some camp leaders claimed many combatantshad become victims of unproven accusations. The rectificationcampaign, which affected every new recruit and later theveterans, brought about a major split in the MCP into factions,including the MCP central faction, 12 th Regiment breakawayfaction, the MCP (Marxist-Leninist)faction which was formed inAugust 1974 and the MCPrevolutionary faction (formerlythe 8 th Regiment).The author at the entrance of the Khao NamKhang Historical Tunnel Natawee District,Songkhla Province, which used to be thebase camp for the 8th Regiment.Photo courtesy of Mahani Awang.The stairs inside the Khao Nam Khangtunnel which was used as an escape route.Photo courtesy of Mahani Awang.CONCLUSIONFrom the discussion, womendo have their own “space” inwar history whether as fighters,spies, wives, daughters and warvictims.In the case of the guerillamovements in Malaya/Malaysiaand <strong>Singapore</strong>, while thewar broke down the boundariesbetween men and women asthey had to fight for survival andvictory, womanhood was nevertotally suppressed from the femalecomrades. To be in loveand to be loved that often endedin unwanted pregnancies, thesadness of being detached from16 biblioasia • April 2010

motherhood as they were not allowed to raise children in thecamps, and missing out on the “outside world” which led manyto escape, were among the issues that had appeared withincamp life in the jungle. This perspective offers a new insightwith regards to women involvement in the guerilla movementin Malaya, and is different from Khoo’s Life as the River Flowswhich is more concerned with the “voices” of these womencollected through interviews without in-depth analysis.The author wishes to thank Dr Cheah Boon Kheng,Honorary Editor, Journal of Malaysian Branch of the Royal AsiaticSociety (JMBRAS), for his constructive comments on anearlier draft of the paper.ENDNOTES1See, Sybil Kathigasu. (1983). No Dramof Mercy (with Introduction by Sir RichardWinstedt and Preface by Cheah BoonKheng). <strong>Singapore</strong>: Oxford UniversityPress; Zhou Mei. (1995). Elizabeth Choy:More than A War Heroine. <strong>Singapore</strong>:Landmark Books. Sybil and Elizabethsuffered direct physical and psychologicaltorture in the hands of the Japanesekempeitai (military police). Sybil died inJune 1949 due to the torture.2The revelation was made through thepublication of memoirs by victims. See,for instance, Maria Rosa Henson. (1999).Comfort Women: A Filipina’s Storyof Prostitution and Slavery under theJapanese Military. Lanbam: Rowman &Littlefield Publishers; Swee Lian. (2008).Tears of a Teen-age Comfort Women.<strong>Singapore</strong>: Horizontal Books; Jan Huff-O’Herne. (1994). 50 Years of Silence:Comfort Women of Indonesia. Australia:Editions Tom Thompson.3‘Indisch’ denotes both Europeanand Eurasian who had settled in theNetherlands East Indies. They were bornthrough the intimate relationship of theirmothers with Japanese soldiers.4This information was based on interviewswith former female MCP guerillas nowresiding in Betong, south Thailand,between January 2009 and March 2009.5Iskandar Carey. (1976). Orang Asli: TheAboriginal Tribes of Peninsular Malaysia.Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, p.311. It was reported that by 1953, 30,000Orang Asli were already undercommunist influence.6Musa Ahmad was one of the importantleaders in the 10th Regiment.7This information was provided by LeongYee Seng, the former members of the 8thRegiment who managed the Khao NamKhang Historical Tunnel in the NataweeDistrict of Songkhla Province during aninterview on 14 March 2009. The KhaoNam Khang Historical Tunnel was formerlya main base for the 8th Regiment.8Ibrahim Chik, Abdullah C.D. and SurianiAbdullah were among MCP leaders whohad first-hand experienced of sabotagethrough poisoning.REFERENCESPrimary Sources1. Political Situation Reports From<strong>Singapore</strong> (Secret). CO 1022/2062. Political Situation Reports From<strong>Singapore</strong> (Secret). CO 1022/2073. Monthly Emergency and PoliticalReports on the Federation of Malayaand <strong>Singapore</strong> Prepared by S.E.ADepartment (Secret). CO 1022/2084. Anti-Yellow Campaign (Confidential).PRO 27 330/56Books and Articles5. Abdullah C. D. (2005). MemoirAbdullah C. D.: Zaman pergerakansehingga 1948. (Vol.1). PetalingJaya: Strategic Information ResearchDevelopment.Call no.: R 959.503 ABD6. Abdullah C.D. (2007). Memoir AbdullahC. D: Penaja dan pemimpin rejimenke-10 (Part 2). Petaling Jaya: SIRD.7. Ahmad, B. (2004). Memoir AhmadBoestamam: Merdeka dengan darahdalam API. Bangi: Penerbit UniversitiKebangsaan Malaysia.Call no.: RSEA 959.50923 AHM8. Allan, S. (2004). Diary of a girl inChangi, 1941-1945. (3rd ed.). NewSouth Wales: Kangaroo Press.Call no.: RSING 940.547252092ALL [WAR]9. Archer, B. (2008). Internee voices:Women and children’s experience ofbeing Japanese captives. In K.Blackburn and K. Hack, Forgottencaptives in Japanese-Occupied Asia(pp. 224-242). London: Routledge.Call no.: RSING 940. 547252095FOR-[WAR]10. Beckett, I. F. W. (1999). Encyclopediaof guerrilla warfare. Santa Barbara:ABC-CLIO, Inc.Call no.: R q355.425 BEC11. Bei Ma Ju Po Huo Di Jian Zheng Xiang[The truth behind the detention of spiesby the Northern PeninsularDepartment] (1999). Thailand: TheCommittee of Kao Nam KhangHistorical Tunnel, Sadao.12. Buchheim, E. (2008). Hide and seek:Children of Japanese-Indisch parents.In K. Blackburn and K. Hack (Eds.).Forgotten captives in Japanese-Occupied Asia (pp. 260-277).London: Routledge.Call no.: RSING 940. 547252095FOR-[WAR]13. Carey, A. T. (1976). Orang asli: Theaboriginal tribes of PeninsularMalaysia. Kuala Lumpur: OxfordUniversity Press.Call no.: R 301.209595 CAR14. Chapman, S. F. (1963). The jungle isneutral. London: Chatto & Windus.Call no.: R SING 940.53595CHA-[WAR]15. Cheah, B. K. (1987). Red star overMalaya: Resistance and social conflictduring and after the JapaneseOccupation, 1941-1946. <strong>Singapore</strong>:<strong>Singapore</strong> University Press.Call no.: RSING 959.5103 CHE16. Chin, A. (1995). The Communist Partyof Malaya: The inside story. KualaLumpur: Vinpress.Call no.: RSING 959.51 CHI17. Chin, C. C. & Hack, K. (Eds.) (2004).Dialogue with Chin Peng: New light onthe Malayan Communist Party.<strong>Singapore</strong>: <strong>Singapore</strong> University Press.Call no.: RSING 959.5104 DIA18. Chin, P. (2003). My side of historyas told to Ian Ward & Norma Miraflor.<strong>Singapore</strong>: Media Masters.Call no.: RSING 959.5104092 CHIbiblioasia • April 201017

REFERENCES19. Colijn, H. (1995). Song of survival:Women interned. Ashland: WhiteCloud Press.Call no.: RSING 940.547252COL [WAR]20. Harper, T. N. (1999). The end ofempire and the making of Malaya.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press.Call no.: RSING 959.5105 HAR21. Hicks, G. (1995). The comfort women:Sex slaves of the Japanese imperialforces. <strong>Singapore</strong>: Heinemann Asia.Call no.: RSING 364.153 HIC22. Hilsdon, A. M. (1995). Madonnas andmartyrs: Militarism and violence in thePhilippines. Australia: Allen & Unwin.Call no.: RSEA 305.409599 HIL23. Huie, S. P. (1992). The forgottenones: Women and children underNippon. Pymble, N.S.W.: Angus &Robertson Publishers.Call no.: RSEA 940. 547252HUI-[WAR]24. Ibrahim, C. (2004). Memoir IbrahimChik: Dari API ke rejimen ke-10.Bangi: Penerbit UniversitiKebangsaan Malaysia.Call no.: RSEA 355.0092 IBR25. Jan, R. O. (1994). 50 years of silence:Comfort women of Indonesia. Australia:Editions Tom Thompson.Call no.: R 364.153 RUF26. Kathigasu, S. (1983). No dram ofmercy. <strong>Singapore</strong>:Oxford University Press.Call no.: RSEA 940.547252 KAT-[WAR]27. Khoo, A. (2004). Life as the riverflows: Women in the Malayan anticolonialstruggle. Petaling Jaya: SIRD.Call no.: RSING 959.5105 LIF28. Macdonald, S. (1987). Drawing thelines – Gender, peace and war: Anintroduction. In S. Macdonald, P.Holden and S. Ardener (Eds.), Imagesof women in peace and war: Crossculturaland historical perspectives.London: Macmillan Education.Call no.: RU 355.00882 IMA29. Michiko, N. (2008). Women’sinternment camp in <strong>Singapore</strong>: Theworld of POW WOW. <strong>Singapore</strong>:<strong>National</strong> University of <strong>Singapore</strong> Press.Call no.: R SING 940.5337NEW-[WAR]30. Pierson, R. R. (1987). Did your motherwear army boots?: Feminist theoryand women’s relation to war, peaceand revolution. In S. Macdonald, P.Holden and S. Ardener (Eds.). Imagesof women in peace and war: Cross-cultural and historical perspectives (pp.205–27). London: Macmillan Education.Call no.: RU 355.00882 IMA31. Rashid, M. (2005). Memoir RashidMaidin: Daripada perjuanganbersenjata kepada perdamaian .Petaling Jaya: Stratejic InformationResearch Development.Call no.: R 323.04209595 RAS32. Shamsiah, F. (2004). Memoir ShamsiahFakeh: Dari AWAS ke rejimen ke-10.Bangi: Penerbit UniversitiKebangsaan Malaysia.Call no.: RSEA 923.2595 SHA33. Short, A. (1975). The communistinsurrection in Malaya 1948-60.London: Frederick Muller.Call no.: RSING 959.5104 SHO34. Stubbs, R. (2004). Heart and minds inGuerilla warfare: the Malayanemergency, 1948-1960. <strong>Singapore</strong>:Eastern Universities Press.Call no.: RSING 959.504 STU35. Suriani, A. (2006). Memoir SurianiAbdullah: Setengah abad dalamperjuangan. Petaling Jaya: StrategicInformation ResearchDevelopment (SIRD).Call no.: R 322.4209595 SUR36. Swee, L. (2008). Tears of a teenagecomfort women. <strong>Singapore</strong>:Horizon Books.Call no.: RSING 940.5405092SWE [WAR]37. Tan, A. (2008). The forgotten womenwarriors of the Malayan CommunistParty. IIAS Newsletter, No. 48.Retrieved November 18, 2009 fromhttp://www.iias.nl/article/forgottenwomen-warriors-malayancommunist-party.38. Tanaka, Y. (1999). Introduction. InM.R. Henson, Comfort women: AFilipina’s story of prostitution andslavery under the Japanese Military.Lanham: Rowman & LittlefieldPublishers.Call no.: RSEA 940.5405092HEN [WAR]39. Turner-Gottschang, K. & Phan,T. H. (1998). Even the women mustfight: Memories of war from NorthVietnam. New York: JohnWiley & Sons.Call no.: RSEA 959.70430922TUR- [WAR]40. Xiulan. (1983). I want to live: Apersonal account of one woman’s futilearmed struggle for the Reds. PetalingJaya: Star Publications.Call no.: RU RCLOS 322.4209595 XIU41. Yoji, A. & Mako, Y. (Eds.) (2008). Newperspectives on the Japaneseoccupation in Malaya and <strong>Singapore</strong>,1941-1945. <strong>Singapore</strong>: <strong>National</strong>University Press.Call no.: RSING 940.5337 NEW [WAR]42. Zhou, M (1995). Elizabeth Choy: Morethan a war heroine. <strong>Singapore</strong>:Landmark Books.Call no.: RSING 371.10092 ZHONewspapers & Magazines43. Dewan Masyarakat, 1991,February – August.44. Straits Echo and Times of Malaya,1949-195145. Utusan Malaysia (2009, May 30).Videorecording/CD-ROM46. Amir, M. (Writer & Director) (2007). Apakhabar orang kampong [Village peopleradio show] [videorecording].<strong>Singapore</strong>: Objectifs Films.Call no.: RAV 791.437 APA47. Amir, M. (Producer & Director) (2006).The last commununist [videorecording].<strong>Singapore</strong>: Comstar Entertainment.Call no.: RSEA 959.510409248. Chan, K. M., Len, C., Ho, C.H., Lau,E., Wang, E. E. (Directors) (2006).I love Malaya [videorecording].<strong>Singapore</strong>: Objectifs Films, 2006.Call no.: RSING 320.53209225951Interviews49. Aishah @ Suti, personalcommunication, January 7, 1998.50. A’Ling @ A’Yu, personalcommunication, March 11, 2009.51. A’Por @ Wun Jun Yin, personalcommunication, March 11, 2009.52. Chang Li Li, personal communication,January 1, 2009.53. Khadijah Daud @ Mama, personalcommunication, February 25, 2009.54. Leong Yee Seng @ Hamitt, personalcommunication, March 14, 2009.55. Maimunah @ Khamsiah, personalcommunication, February 25, 2009.56. Muna or Mek Pik, personalcommunication, March 14, 2009.57. Shiu Yin, personal communication,March 14, 2009.58. Ya Mai, personal communication,January 1, 2009.18 biblioasia • April 2010

Feature19Chinese Dialect Groups andTheir Occupationsin 19 th and Early 20 th Century <strong>Singapore</strong>“The Teochews are reputed for making fine kuayteow,the Hokkiens for their mee,the Hainanese for their coffee,and the Cantonese for their pee”. 1Li Yih Yuan, Yige Yizhi de Shizhen[ 一 个 移 殖 的 市 镇 : 马 来 亚 华 人 市 镇 生 活 的 调 查 研 究 ]By Jaclyn TeoLibrarianLee Kong ChianReference <strong>Library</strong><strong>National</strong> <strong>Library</strong>The above ditty is a common saying indicative of socialstereotyping among Chinese dialect groups observed in Muar,Johore, in the 1950s. In fact, as far back as the 19 th and early20 th century, there were already studies in <strong>Singapore</strong> highlightingthe relationship between the occupations held by Chineseimmigrants and their dialect origins (Braddell, 1855; Seah,1848; Vaughan, 1874). Hokkiens and Teochews, being earlysettlers on the island, were known to dominate the more lucrativebusinesses, while later immigrants and minority dialectgroups like Hainanese and Foochows were frequently regardedas occupying a lower position in the economic standings(Tan, 1990). Drawing on published English resources availablein the Lee Kong Chian Reference <strong>Library</strong>, this articleaims to explore why certain Chinese dialect groups in <strong>Singapore</strong>,such as Hokkiens, Teochews, Cantonese, Hakkas andHainanese, seem to have specialised in specific trades andoccupations, particularly during the early colonial period untilthe 1950s. It also posits some reasons why dialect groupidentities are no longer as dominant and obvious now asthey used to be.CHINESE MIGRATION TO SINGAPOREBefore delving into the occupational specialisation of eachdialect group, it is important to first understand the social andeconomic background that resulted in the large-scale migrationof Chinese from China to <strong>Singapore</strong> in the 19 th century. Duringthat time, life was extremely difficult in China; overpopulationresulted in a shortage in rice, a basic food staple, which led toinflation. Chinese peasants were also exploited by landlords,who imposed exorbitant rents on cultivable land to counter thehigh land taxes and surcharges levied by the Qing government.Natural calamities further aggravated the situation. From 1877to 1888, for example, the drought in north and east China leftclose to six million people homeless and, without any aid fromthe government, many starved to death. Moreover, China wasalso mired in political turmoil. The Taiping Rebellion (1850-65),which originated in southern China, wiped out about 600 citiesand towns, destroyed all the central provinces of China and adverselyaffected agricultural production, leading to widespreadpoverty and lawlessness. All these factors pushed manyChinese to go overseas in search of a better life (Yen, 1986).Fortuitously, the founding of <strong>Singapore</strong> by the British in 1819,and the subsequent establishment of the Straits Settlementsstates of Penang, Malacca and <strong>Singapore</strong> by 1826 opened upnumerous trade and work opportunities for the Chinese. In thelast quarter of the 19 th century, the discovery of tin in the Malayanstates, as well as the large-scale development of rubberplantations, were additional pull factors for the Chinese tomigrate to the region (Tan, 1986). The British brought aboutlaw and order in the Straits Settlements and initiated policiesof free trade, unrestricted immigration (at least until the AliensOrdinance was introduced in 1933 to limit the number of malemigrants) (Cheng, 1985) and non-interference in the affairs ofthe migrant population, all of which were advantageous to theChinese migrants in search of economic advancement (Tan,1986). <strong>Singapore</strong>, which came under direct British control as acrown colony in 1867, was not only the most important hub inthe south of the Malayan Peninsula for the handling and processingof raw materials, it was also one of the major transitpoints where indentured labour from China and India were deployedto other parts of Southeast Asia. With a thriving economy,abundant job opportunities, and favourable British policies,large numbers of Chinese flocked to <strong>Singapore</strong>. In a letterto the Duchess of Somerset in June 1819, Stamford Raffles,the founder of modern <strong>Singapore</strong>, claimed that his “new colonythrives most rapidly… and it has received an accession ofpopulation exceeding 5000, principally Chinese, and their numberis daily increasing” (quoted in Song, 1923, p. 7). By 1836,the Chinese population (at 45.9%) had already surpassed theindigenous Malay community to become the major ethnic groupin <strong>Singapore</strong> (Saw, 1969).FORMATION OF TRADE SPECIALISATIONSDespite originating from the same country, the Chinesecommunity in <strong>Singapore</strong> was not a homogenous one, but washighly divided and fragmented instead (Tan, 1986). The Chinesecame from different provinces in China and spoke different dialects:those who came from the Fujian province spoke Hokkien;the ones from Chaozhou prefecture spoke Teochew; peoplefrom Guangdong province spoke Cantonese, while those fromHainan Island spoke Hainanese. In addition, the dialect groupsworshipped different local deities and considered their own

traditions and customs to be superior to those of the others(Yen, 1986). As the different spoken dialects posed a significantcommunication barrier between groups, the Chinese immigrantsnaturally banded together within their own provincialcommunities for security and assistance in this new environment(Yen, 1986). This phenomenon was further aided byRaffles’ plan to segregate the different groups (Braddell, 1854).In 1822, Raffles proclaimed that “in establishing the Chinesekampong on a proper footing, it will be necessary to advert tothe provincial and other distinctions among this peculiar people.It is well known that the people of one province are morequarrelsome than another, and that continued disputes and disturbancestake place between people of different provinces”.(Song, 1923, pp.12)How then did the trade specialisations based on dialectgroupings come about? Cheng (1985) posited that the concentrationof each dialect group in specific areas on the islandprovided a geographical and socioeconomic base for startinga trade. As more and more people of the same dialect groupmoved into the same area, the trade that was initially started bysome would become increasingly established and entrenched.This was especially so because new migrants to <strong>Singapore</strong>tended to turn to their relatives (usually of the same dialectgroup) for jobs. Indeed, an early immigrant, Ang Kian Teck,confirmed this point. He related that “when you first arrive in<strong>Singapore</strong>, you find out what your relatives are doing and youfollow suit. If your relatives are rickshaw pullers, then you toowould become one. My elder brother was already in <strong>Singapore</strong>working as chap he tiam shopkeeper, so I joined him.” (quotedin Chou & Lim, 1990, p. 28). It was also natural for experiencedmigrants, such as fishermen, artisans and traders, to continuewith their specialised trades when they resettled. Factors suchas the physical environment, as well as the intervention of secretsocieties, also contributed to the dominance of particulardialect groups in certain trades (Mak, 1981).Mak (1995) puts forth several reasons to explain why suchoccupational patterns continued to persist. First, businesseswhich were capital-intensive, by the very fact that they requiredlarge amounts of resources, tended to exclude the poorer dialectgroups. Close network ties within communities similarlyprevented other dialect groups from participating in the sametrades. The way trade groups were organised, and the formationof occupational guilds and the apprenticeship system, weresuccessful in keeping businesses within certain dialect groups.Occupational guilds helped to contain the supply of materialsand information required for the trade within the dialect group.For example, the <strong>Singapore</strong> Cycle and Motor Traders’ Association,dominated by Henghuas, ensured that the continuationof trade stayed within the same dialect group by encouragingmembers to take over the retiring businesses of fellow clansmen(Cheng, 1985). The apprenticeship system, which entailsthe passing of skills from one to another, was more effectivewhen employers and trainees understood each other. Hence,the employer who was looking for an apprentice would tendto choose someone from the same dialect origin. Over time,the acquired reputation of a dialect group in a particular trademight also prevent other dialect groups from competing in thesame trade successfully.All the above factors reinforced one another and strengthenthe dialect group’s position in that trade. As a result, the “consequenceof dialect trade specialisation is that the particulardialect becomes the language of the trade. Dialect incomprehensibilityamong different dialect groups, dialect patronage,and trade associations are mutually influencing and reinforcing;and together they form a barrier by excluding members of otherdialect groups from entry or effective participation. Thus, unlessthe conditions for dialect trade are disrupted, the trend ofdevelopment is towards further consolidation and expansion.”(Cheng, 1985, p. 90).DOMINANT TRADES FORMAJOR DIALECT GROUPSHokkiensAmong the various dialect groups, Hokkiens were among theearliest to arrive in <strong>Singapore</strong>. It was recorded that the firstgroups of Chinese to arrive in <strong>Singapore</strong> had come from Malaccaand most of these early migrants were believed to beHokkiens, then known as Malacca–born Chinese (Seah, 1848).Subsequently, Hokkiens from Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, Yongchunand Longyan prefectures of Fujian province also migratedto <strong>Singapore</strong> (Cheng, 1985). With a long history of junk tradeinvolvement in Southeast Asia, it was natural for Hokkiensto continue to be active in commerce, working as shopkeepers,general agriculturalists, manufacturers, boatmen, porters,All rights reserved, OpinionBooks, 1990.All rights reserved, <strong>Singapore</strong>Society of Asian Studies, 1995.fishermen and bricklayers, according to an estimate made in1848 (Braddell, 1855). In fact, Braddell noted that the HokkienMalaccan Chinese, who were Western educated andhad prior interactions with European merchants, had “a virtualmonopoly of trade at <strong>Singapore</strong>” in the 1850s (p. 115). Rafflesalso noted in a letter to European officials that the morerespectable traders were found among the Hokkiens (Tan,1986). The Hokkiens congregated and settled in Telok AyerStreet, which was near the seacoast, and this gavethem an added advantage for coastal trade. All thesepropelled the Hokkiens to successfully establish a20 biblioasia • April 2010

strong commercial footing onthe island (Cheng, 1985).Hokkiens’ strong economicposition allowed them toaccumulate capital, whichin turn gave them a higherchance of venturing into newbusinesses like rubber plantingwhen the economy grew(Cheng, 1985). Hokkien capitalistswere the first pioneers toinvest in rubber planting, whichwas considered to be a riskierand more capital-intensiveventure than gambier planting,as rubber could be tappedonly after many years, andwas also subjected to violentprice fluctuations. The rubberboom during World War I andthe Korean War strengthenedHokkiens’ economic positionfurther and Hokkiens went onto control the speculative coffee and spice trade, as well as anumber of banks, including the Ho Hong Bank (1917), Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation (1932), United Overseas Bank(1935), Bank of <strong>Singapore</strong> (1954), and Tat Lee Bank (1975), toname a few (Cheng, 1985).Another well-documented trade specialisation amongHokkiens (specifically those who came from Anxi of Quanzhouprefecture) was the chap he tiam business, otherwise knownas the “mixed goods” store or retail provision store business(Chou & Lim, 1990). Well-known Hokkien personalities likeTan Kah Kee and Lee Kong Chian were also involved in thepineapple-canning business (Tan, 1999). All in all, Hokkiensdominated the more lucrative trades and had a lion’s sharein the following fields: banking, finance, insurance, shipping,manufacturing, import and exporttrade in Straits produce,ship-handling, textiles, realtyand even building andconstruction (Cheng, 1985).Hokkiens were and continueto be the largest Chinesedialect group in <strong>Singapore</strong>, accountingfor more than 40% ofthe overall Chinese population(Leow, 2001).A chap he tiam in China Street stocked with dried goods and Chinese produce.Image reproduced from Tan, T. (Ed.). (1990). Chinese dialect groups: Traits and trades, p. 24.All rights reserved, Opinion Books, 1990.the Chaozhou prefecture in Guangdong province.Teochews were inclined towards agriculture, and theireconomic prowess was anchored in the planting and marketingof gambier and pepper (Tan, 1990). Records have shownthat even before the arrival of the British in <strong>Singapore</strong>, someTeochew farmers and their gambier plantations were alreadyon the island (Bartley, 1933). The first Teochews to arrive onthe British colony were believed to have come from the RiauIslands (Cheng, 1985), which had a large Teochew settlement,and was a centre for gambier trade. With a free port status offeringa gateway to international markets, <strong>Singapore</strong> soon replacedRiau as the preferred gambier trading centre for manyTeochew traders. Before long, the gambier and pepper trades in<strong>Singapore</strong> were dominated by Teochews, and in the 1840s,TeochewsTeochews, who are sometimesknown as the “SwatowPeople”, formed thesecond largest dialect groupin <strong>Singapore</strong> (Tan, 1990),and originated largely fromA kelong.Image reproduced from Tan, T. (Ed.). (1990). Chinese dialect groups: Traits and trades, p. 39.All rights reserved, Opinion Books, 1990.biblioasia • April 201021