pension portability and labour mobility in the united states. new ...

pension portability and labour mobility in the united states. new ...

pension portability and labour mobility in the united states. new ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

AbstractWe explore <strong>the</strong> role of employer provided <strong>pension</strong>s on job <strong>mobility</strong> choices us<strong>in</strong>g datafrom <strong>the</strong> Survey of Income <strong>and</strong> Program Participation. Def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans are foundto have a significant negative effect on <strong>mobility</strong>. However, we f<strong>in</strong>d no significant evidencethat <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> losses deter job <strong>mobility</strong> among workers coveredby<strong>the</strong>seplans. Wealsof<strong>in</strong>d that <strong>the</strong> <strong>portability</strong> policy change implemented by <strong>the</strong> TaxReform Act of 1986 had only m<strong>in</strong>or effects on <strong>mobility</strong>. Puzzl<strong>in</strong>gly, def<strong>in</strong>ed contributionplans, although fully portable, are found to have an impact similar to def<strong>in</strong>ed benefitplans. Evidence of compensation premiums accru<strong>in</strong>g to workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong>, union <strong>and</strong>health <strong>in</strong>surance covered jobs supports <strong>the</strong> view that workers are less likely to leave”good jobs”.Keywords: Labour <strong>mobility</strong>; Pension <strong>portability</strong>; Switch<strong>in</strong>g regression models.JEL classification: C35; J31; J32; J41; J63; J68.0 We thank Raquel Carrasco, Thomas Crossley <strong>and</strong> Franco Peracchi for many suggestions <strong>and</strong> commentson earlier drafts of this paper. V. Andrietti acknowledges f<strong>in</strong>ancial support from CeRP <strong>and</strong>from a Marie Curie Fellowship of <strong>the</strong> European Community program Improv<strong>in</strong>g Human Potentialunder contract number HPMF-CT-2000-00504. V. Hildebr<strong>and</strong> acknowledges f<strong>in</strong>ancial support fromCEPS/INSTEAD <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> GFAD at York University. Correspondence to: V<strong>in</strong>cenzo Andrietti, Departamentode Economia, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid. c/ Madrid 126 28903 Getafe (Madrid).Spa<strong>in</strong>. Tel. +34 91 6249619 Fax +34 91 6249875. E-mail: v<strong>and</strong>riet@eco.uc3m.es.2

1 IntroductionThe question of employer provided <strong>pension</strong>s’ <strong>portability</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US has been widelydebated with<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> ”<strong>new</strong> <strong>pension</strong> economics” literature. Us<strong>in</strong>g different empirical approaches,Allen, Clark <strong>and</strong> McDermed (1988, 1993), Ippolito (1985, 1987), <strong>and</strong> Gustman<strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1987, 1993, 1995) all <strong>in</strong>vestigate whe<strong>the</strong>r a lack of <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong>is primarily responsible for <strong>the</strong> lower job <strong>mobility</strong> rate observed among <strong>pension</strong> coveredworkers. However, no consensus emerged from those studies. Fu<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> evidence<strong>the</strong>y provide is based on data collected dur<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> late 1970s <strong>and</strong> early 1980s, thatcannot reflect <strong>the</strong> rapid changes experienced by <strong>the</strong> US <strong>pension</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>labour</strong> markets <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> last two decades.First, <strong>the</strong>re is substantial evidence 1 that employer provided <strong>pension</strong> coverage hassignificantly decl<strong>in</strong>ed among young males. Structural changes <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>labour</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>pension</strong>markets have been advanced as possible explanations. A second development is<strong>the</strong> shift from def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit towarddef<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans. The rapid growth ofdef<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans is expected to affect both job <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>and</strong> future retirement<strong>in</strong>come as well as <strong>the</strong> structure of wages. Under def<strong>in</strong>ed benefits plans, workers accumulatelower retirement benefits when <strong>the</strong>y change employers frequently. In contrast,job changes have relatively little impact on future retirement benefits for those enrolled1 See, among o<strong>the</strong>rs, Even <strong>and</strong> Macperson (1994).1

<strong>in</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans. This implies that <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> future mobile workers may enterretirement with larger total <strong>pension</strong> benefits than <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> past, although <strong>the</strong> adequacy ofretirement <strong>in</strong>come provided by def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans is widely debated. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans place greater responsibility <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>vestment risks on <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>dividual worker. In a competitive sett<strong>in</strong>g, such a risk shift is likely to <strong>in</strong>duce highercompensation levels as compensat<strong>in</strong>g differentials to employees, which also potentiallyaffect <strong>mobility</strong>.In order to account for <strong>the</strong>se developments <strong>and</strong> to contribute to a better underst<strong>and</strong><strong>in</strong>gof <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong>-<strong>mobility</strong> relationship <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US, we use data drawn from differentsurvey years of <strong>the</strong> Survey of Income <strong>and</strong> Program Participation (SIPP) spann<strong>in</strong>g 1984to 1994. In contrast with <strong>the</strong> limited <strong>in</strong>terpretability of reduced form estimates providedby most of <strong>the</strong> previous studies, we estimate a structural model similar to thatof Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993). The advantage of <strong>the</strong> structural approach is thatit allows one to separately identify <strong>the</strong> impact of employer provided <strong>pension</strong>s (ei<strong>the</strong>rdef<strong>in</strong>ed benefit ordef<strong>in</strong>edcontributionplans),<strong>and</strong>ofprospectivewagedifferentials on<strong>the</strong> probability of <strong>in</strong>dividual job <strong>mobility</strong>.However, our model<strong>in</strong>g differs from Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993) <strong>in</strong> two ma<strong>in</strong> respects.First, we correct for <strong>the</strong> potential endogeneity of <strong>mobility</strong> choices by estimat<strong>in</strong>ga more general sample selection model. Second, we adopt a specification which allowsus to disentangle <strong>the</strong> effects of <strong>the</strong> various fr<strong>in</strong>ge benefits <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>and</strong>2

def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution <strong>pension</strong>s as well as health <strong>in</strong>surance coverage. In addition, <strong>the</strong>period covered by our data allows us to exam<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> effect on <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>mobility</strong> of <strong>the</strong>reduction <strong>in</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g period <strong>in</strong>troduced by <strong>the</strong> Tax Reform Act of 1986.We f<strong>in</strong>d that workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong>s are significantly less likely tomove. However, <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>portability</strong> loss aris<strong>in</strong>g to workers leav<strong>in</strong>g a def<strong>in</strong>ed benefitplan does not seem to play a significant role <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong> choices. Ourresults also reveal that def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans, despite of <strong>the</strong>ir complete <strong>portability</strong>,are as important as def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong>. In addition, employerprovided health <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> union coverage are also found to play a major role <strong>in</strong>deterr<strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong>. These results seem to underm<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> argument that <strong>the</strong> lack of<strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> is a key factor <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>mobility</strong> rate observed amongworkers <strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong> covered jobs. Evidence of compensation premiums <strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong> <strong>and</strong>health <strong>in</strong>surance covered jobs fur<strong>the</strong>r supports <strong>the</strong> alternative view that workers <strong>in</strong>”good jobs” are simply less likely to move.From a policy perspective, <strong>the</strong>se results cast doubts on <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of reformsaimed at improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>labour</strong> market efficiency through <strong>portability</strong> measures. On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rh<strong>and</strong>, <strong>the</strong> data do suggest that <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> reforms have improved <strong>the</strong> retirement<strong>in</strong>come prospects of mobile workers by some 46 percent.So while our estimates ofbehavioural responses suggest that <strong>the</strong> 1986 Tax Reform Act had almost no impact onjob <strong>mobility</strong>, it may have succeeded with respect to <strong>the</strong> complementary goal of ensur<strong>in</strong>g3

equired st<strong>and</strong>ards for <strong>the</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>pension</strong> benefits. ERISA first established a 10year vest<strong>in</strong>g st<strong>and</strong>ard. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 fur<strong>the</strong>r reduced <strong>the</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g period,allow<strong>in</strong>g private s<strong>in</strong>gle employer plans to provide ei<strong>the</strong>r full (cliff) vest<strong>in</strong>g after 5 yearsof service (with no partial vest<strong>in</strong>g before that time) or graded vest<strong>in</strong>g of 20 percentafter 3 years of service <strong>and</strong> 20 percent for each subsequent year of service, with fullvest<strong>in</strong>g reached after 7 years of service 4 .Currently, most def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans allow for <strong>the</strong> immediate vest<strong>in</strong>g of employeecontributions, while virtually all def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plansimposefive years vest<strong>in</strong>g.However, vest<strong>in</strong>g is nei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>the</strong> only nor <strong>the</strong> most important element to consider <strong>in</strong>evaluat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>portability</strong> of employer provided <strong>pension</strong>s. While <strong>mobility</strong> restrictionsimplied by vest<strong>in</strong>g rules have been found to be <strong>in</strong>significant <strong>in</strong> most empirical studies 5 ,a more relevant <strong>portability</strong> issue arises to workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans 6 .The typical structure of such plans implies that upon leav<strong>in</strong>g a job before retirement,vested workers are entitled to a deferred retirement <strong>pension</strong> annuity determ<strong>in</strong>ed on <strong>the</strong>basis of earn<strong>in</strong>gs received upon leav<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> firm. In <strong>the</strong> US deferred annuities are not<strong>in</strong>dexed to <strong>in</strong>flation or to productivity growth. Thus, vested workers who move across4 The <strong>new</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g provisions applied to <strong>pension</strong> rights accrued after January 1, 1989.5 See, for example, Allen, Clark <strong>and</strong> McDermeed (1988, 1993).6 A necessary condition for <strong>the</strong> rise of <strong>portability</strong> losses is that def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong>s are <strong>in</strong>terpretedas implicit contracts under which workers accept to forego wages proportional to retirement<strong>pension</strong> benefits conditional upon rema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g with <strong>the</strong> firm until retirement aga<strong>in</strong>st <strong>the</strong> firm’s promise topreserve <strong>the</strong> employment relationship <strong>and</strong> to pay <strong>the</strong> agreed <strong>pension</strong> benefits upon worker’s retirement(Ippolito, 1985).6

firms with identical def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong> plans <strong>and</strong> offer<strong>in</strong>g similar wage profiles, willaccumulate lower total <strong>pension</strong> benefits than workers who rema<strong>in</strong> with <strong>the</strong> same firmthroughout <strong>the</strong>ir career 7 .In contrast, workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans typically do not <strong>in</strong>cursuch capital losses when <strong>the</strong>y change employers. In general, <strong>the</strong>se workers have a legalclaim on a <strong>pension</strong> account <strong>in</strong> which all <strong>pension</strong> contributions have been <strong>in</strong>vested. If <strong>the</strong>funds rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> an account after <strong>the</strong> worker leaves <strong>the</strong> firm, <strong>the</strong> account will cont<strong>in</strong>ueto grow by <strong>the</strong> accumulated returns on <strong>in</strong>vested assets. Alternatively, <strong>the</strong> funds can bewithdrawn from <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong> account of a former employer <strong>and</strong> ei<strong>the</strong>r rolled over <strong>in</strong>toan <strong>in</strong>dividual retirement account (IRA) or <strong>in</strong> a <strong>new</strong> <strong>pension</strong> account. In ei<strong>the</strong>r case,<strong>the</strong> worker who has changed jobs reta<strong>in</strong>s <strong>the</strong> full value of <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong> funds. Thus, <strong>in</strong>general, def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans are portable <strong>and</strong> workers can change jobs withoutsuffer<strong>in</strong>g any loss <strong>in</strong> future <strong>pension</strong> benefits.The possible consequences of <strong>the</strong> lack of <strong>portability</strong> of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans on <strong>in</strong>dividualjob <strong>mobility</strong> choices have been widely <strong>in</strong>vestigated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> US <strong>pension</strong> literature.Us<strong>in</strong>g simple statistical models (such as probit models expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g job change 8 ,orhazardmodels 9 expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g job tenure), early empirical studies documented a significantnegative correlation between <strong>pension</strong>s <strong>and</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong>. The ”<strong>new</strong> <strong>pension</strong> economics”7 See Andrietti (2001) for a detailed exposition of <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong> loss computation methodology.8 Mitchell (1983).9 Wolf <strong>and</strong> Levy (1984).7

Us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> 1984 release of SIPP, Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993) develop a researchapproach similar to <strong>the</strong> one adopted <strong>in</strong> this paper. The authors question <strong>the</strong> causal<strong>in</strong>terpretation usually attributed to <strong>the</strong> strong negative correlation between <strong>pension</strong>coverage <strong>and</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong>. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, <strong>the</strong>y look for o<strong>the</strong>r causal factors whose omissioncould have generated this correlation. In particular, <strong>the</strong>y suggest that <strong>the</strong> causality mayrun from <strong>the</strong> implicit contract, <strong>in</strong>terpreted as <strong>the</strong> omitted factor, to <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>pension</strong>design. As implicit contracts may provide <strong>the</strong> payment of compensation premiums to<strong>pension</strong> covered workers, <strong>the</strong> authors model <strong>the</strong> relative role of lifetime efficiency wagepremiums <strong>and</strong> <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> losses on <strong>in</strong>dividual job <strong>mobility</strong>. They assume that<strong>the</strong>re is no separate role for <strong>pension</strong> coverage beyond its monetary <strong>in</strong>fluence. Thus, <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong>ir specification, <strong>pension</strong> coverage is not <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> equation but itsmonetary effect is <strong>in</strong>corporated <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>ir measure of lifetime wage differential (referredto by Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993) as <strong>the</strong> compensation premium). This assumptiondoes not allow <strong>the</strong>m to dist<strong>in</strong>guish between <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> effects of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>and</strong>def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution <strong>pension</strong>s 13 . Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, our specification also <strong>in</strong>cludes importantpotential <strong>mobility</strong> predictors such as employer provided health <strong>in</strong>surance coverage.Impos<strong>in</strong>g jo<strong>in</strong>t normality on <strong>the</strong> wage <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> equation error terms, <strong>the</strong>ybackloaded structure of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans attract low discounters, while <strong>the</strong> actuarially fair lumpsums provided to early leavers by def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans encourage <strong>the</strong> departure of mistakenlyhired high discounters early <strong>in</strong> tenure.13 However, <strong>the</strong>y provide some evidence of <strong>the</strong> unexpected role of def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans <strong>in</strong>prevent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estimation of <strong>the</strong>ir reduced form <strong>mobility</strong> equation.9

estimate a self-selection model through a maximum likelihood procedure.However,<strong>the</strong>ir self-selection mechanism differs from st<strong>and</strong>ard models with endogenous switch<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> one estimated <strong>in</strong> this paper. In particular, <strong>the</strong> estimation of <strong>the</strong>ir wagedifferential parameter does not explicitly account for potential sample selection <strong>in</strong>tomover/stayer status. In <strong>the</strong>ir approach, <strong>the</strong> wage differential is just given by <strong>the</strong> differencebetween <strong>the</strong> current <strong>and</strong> alternative wages actually observed for movers. The usualapproach is to derive <strong>the</strong> wage differential from counterfactual imputations. Gustman<strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993) procedure provides <strong>the</strong>m with enough <strong>in</strong>formation to estimate anadditional (<strong>in</strong>cidental) parameter - <strong>the</strong> correlation among unobservables <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> current<strong>and</strong> alternative wage equations - which is not identified <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard sett<strong>in</strong>g of aregression model with endogenous switch<strong>in</strong>g.Their f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs suggest that efficiency wage premiums ra<strong>the</strong>r than backloaded <strong>pension</strong>accrual patterns are <strong>the</strong> primary cause of lower turnover rates among workers coveredby def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans.This brief overview reveals <strong>the</strong> absence of a common view <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> literature regard<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> role played by f<strong>in</strong>ancial (<strong>pension</strong> loss) dis<strong>in</strong>centives, compensation premiums <strong>and</strong>self-selection <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>mobility</strong> rates of <strong>pension</strong> covered workers. Thema<strong>in</strong> objective of this paper is to shed some more light on <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong>losses <strong>and</strong> compensation premiums on <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual job <strong>mobility</strong> choices <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> USus<strong>in</strong>g more recent data sources. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> period covered by our data allows us to10

dent variable. However, because of <strong>the</strong> poor quality of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SIPP onseparation type (quit versus layoff), we consider an <strong>in</strong>dividual to be a mover as long asa transition to a <strong>new</strong> job has occurred, <strong>in</strong>dependently of <strong>the</strong> cause of separation. Thisassumption is consistent with <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oretical argument 16 that <strong>in</strong> an efficient turnoverframework a truly mean<strong>in</strong>gful dist<strong>in</strong>ction cannot be made between quits <strong>and</strong> layoffss<strong>in</strong>ce workers wish<strong>in</strong>g to quit could <strong>in</strong>duce a layoff, while firms desir<strong>in</strong>g a layoff could<strong>in</strong>duce a quit. We <strong>the</strong>refore implicitly assume all turnover to be ”efficient” irrespectiveof who <strong>in</strong>itiates it. The <strong>mobility</strong> choice of <strong>in</strong>dividual i is represented by <strong>the</strong> b<strong>in</strong>aryr<strong>and</strong>om variable I i =1{Ii ∗ > 0},where 1{·} is <strong>the</strong> usual <strong>in</strong>dicator function <strong>and</strong> Ii ∗ is <strong>the</strong>lifetime net ga<strong>in</strong> from <strong>mobility</strong>. We specify <strong>the</strong> latter as follows:I ∗ i ≡ Y mi − Y si − C i R 0, i =1, ....n, (1)where Y mi is <strong>the</strong> expected present value of lifetime earn<strong>in</strong>gs on <strong>the</strong> assumption that <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>dividual moves <strong>in</strong>to his/her best alternative job, Y si is <strong>the</strong> expected present value oflifetime earn<strong>in</strong>gs on <strong>the</strong> assumption that <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>in</strong> his/her current job,C i is <strong>the</strong> expected present value of costs associated with <strong>mobility</strong>. The <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>mobility</strong>choice <strong>in</strong> (1) is based on an ex-ante comparison. The <strong>in</strong>dividual moves to a differentjob if his/her expected lifetime earn<strong>in</strong>gs ga<strong>in</strong>s exceed <strong>mobility</strong> costs. O<strong>the</strong>rwise he/shestays <strong>in</strong> his/her current job. In represent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual decision empirically we haveunderestimate <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> loss.16 Borjas <strong>and</strong> Rosen (1980) <strong>and</strong> McLaughl<strong>in</strong> (1991) provide empirical support to this argument.12

two ma<strong>in</strong> problems. First, we do not observe lifetime wage earn<strong>in</strong>gs for actual movers<strong>and</strong> stayers. We assume current earn<strong>in</strong>gs to be <strong>the</strong> best predictor of lifetime earn<strong>in</strong>gs 17 .The second, <strong>and</strong> even more important, problem is that we cannot observe <strong>the</strong> counterfactualwage for each <strong>in</strong>dividual, that is what <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual would have earned hadhe/she taken <strong>the</strong> alternative <strong>mobility</strong> choice. What we observe is <strong>the</strong> wage conditionalon <strong>the</strong> choice actually taken. In order to obta<strong>in</strong> predictions of <strong>the</strong> counterfactual wagefor each <strong>in</strong>dividual we use <strong>the</strong> estimated coefficients of <strong>the</strong> actual movers <strong>and</strong> stayers.Given that <strong>the</strong> event {I ∗ i > 0} is equivalent to <strong>the</strong> event {I + i > 0}, whereI + i = I ∗ i /Y si<strong>and</strong> that <strong>mobility</strong> costs are not directly observable, we can specify <strong>the</strong> selection <strong>in</strong>dexas follows:I ∗ i = γ(ln Y mi − ln Y si ) − β 0 c X ci − v ci , i =1, ....n, (2)where X ci is a vector of personal <strong>and</strong> job specific <strong>mobility</strong> costs predictors, β c is avector of unknown parameters, <strong>and</strong> v ci is a cont<strong>in</strong>uous r<strong>and</strong>om variable distributed<strong>in</strong>dependently of X ci with zero mean <strong>and</strong> variance σ 2 c. Wage equations for movers <strong>and</strong>17 Ano<strong>the</strong>r approach would have been to assume a constant, but unobserved, rate of future wagegrowth, discount<strong>in</strong>g back at a constant <strong>in</strong>terest rate <strong>the</strong> streams of future wages <strong>and</strong> assum<strong>in</strong>g that<strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual stays <strong>in</strong> his/her job until retirement, on <strong>the</strong> basis of <strong>the</strong> follow<strong>in</strong>g formula:Lifetime W age =RXY t e (ge −i e )t ,where g e is <strong>the</strong> expected nom<strong>in</strong>al rate of wage growth <strong>and</strong> i e is <strong>the</strong> expected nom<strong>in</strong>al discount rate.However, <strong>the</strong>se approaches are similar <strong>in</strong> that both implicitly assume that available <strong>in</strong>formation aboutcurrent wages is <strong>in</strong>dicative of lifetime wages.t=013

stayers are modelled us<strong>in</strong>g a semilog form:ln Y mi = β 0 m X i + v mi , i =1, ....m, (3)ln Y si = β 0 sX i + v si , i = m +1, ....n, (4)where ln Y mi is <strong>the</strong> natural logarithm of hourly net wages for movers, ln Y si is <strong>the</strong> naturallogarithm of hourly net wages for stayers, X i is a vector of personal <strong>and</strong> job specificvariables <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g education, experience <strong>and</strong> its square, occupational <strong>pension</strong>, health<strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> union coverage, <strong>in</strong>dustry, occupation, residential <strong>and</strong> location dummies,β m , β s are vectors of unknown parameters, <strong>and</strong> v mi ,v si are cont<strong>in</strong>uous r<strong>and</strong>om errorsconta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g unobservable variables, such as <strong>in</strong>dividual abilities <strong>and</strong> specific capital thatare useful <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> chosen job, distributed <strong>in</strong>dependently of X i with zero mean <strong>and</strong> unknownvariances σ 2 m, σ 2 s. Equations (2), (3), <strong>and</strong> (4) represent <strong>the</strong> structural model of<strong>in</strong>terfirm job <strong>mobility</strong>. Substitut<strong>in</strong>g from (4) <strong>and</strong> (3) <strong>in</strong>to (2) yields a reduced formselection <strong>in</strong>dex:I ∗ i ≡ β 0 W i + v i , i =1, ....n, (5)where W i =[X i , X ci ] , β =[γ(β m − β s ), −β c ] , <strong>and</strong> v i =(γ(v mi −v si )−v ci ). The decisionrule (5) selects <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong>to movers <strong>and</strong> stayers accord<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong>ir largest expectedpresent value. Therefore, wages actually observed <strong>in</strong> each group are not r<strong>and</strong>om samplesof <strong>the</strong> population, but truncated samples. The expected value of worker i’s wage14

conditional on observed characteristics <strong>and</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> status is:E(ln Y mi |W i ,I i =1)=β 0 m X i + E(v mi |W i ,I i =1), i =1, ....m, (6)E(ln Y si |W i ,I i =0)=β 0 sX i + E(v si |W i ,I i =0), i = m +1, ....n. (7)Knowledge of <strong>the</strong> functional form of <strong>the</strong> conditional mean errors allows estimationof <strong>the</strong> model parameters. Assum<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> error terms (v mi ,v si ,v i ) are <strong>in</strong>dependentof (X i , W i ) <strong>and</strong> have a trivariate normal distribution, with a zero mean vector <strong>and</strong>unknown variance covariance matrix:⎡X = ⎢⎣σ 2 m σ sm σ vmσ ms σ 2 s σ vsσ mv σ sv 1⎤,⎥⎦equations (6) − (7) may be rewritten as:E(ln Y mi |W i ,I i =1)=β 0 mX i + σ mv λ mi , i =1, ....m, (8)E(ln Y si |W i ,I i =0)=β 0 sX i + σ sv λ si , i = m +1, ....n, (9)where λ mi = φ(β0 W i )Φ(β 0 W i ) <strong>and</strong> λ si= − φ(β0 W i )1−Φ(β 0 W i )are <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>verse Mills’ ratios, with φ (·) <strong>and</strong>Φ (·) be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> st<strong>and</strong>ard normal density <strong>and</strong> cumulative distribution function respectively.Selectivity bias <strong>in</strong> wage equations estimation arises from any correlation between<strong>the</strong> unobserved determ<strong>in</strong>ants of <strong>in</strong>terfirm job <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>and</strong> wages. Only if such a correlationwere not present, <strong>the</strong> usual ord<strong>in</strong>ary least square method could be used to15

consistently estimate β j on <strong>the</strong> selected subsample. In general, however, this does notoccur. Consistent estimates of <strong>the</strong> above model are obta<strong>in</strong>ed by apply<strong>in</strong>g Heckman’s(1979) two-stage method. Wage equations’ estimated coefficients are <strong>the</strong>n used to predictlog-wage earn<strong>in</strong>gs for each <strong>in</strong>dividual i, givenhis/herowncharacteristicsX i :ln Ỹmi = ˆβ 0 m X i +ˆσ mvˆλmi , i =1, ....m, (10)ln Ỹsi = ˆβ 0 s X i +ˆσ svˆλsi , i = m +1, ....n, (11)<strong>and</strong> to compute <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual ex-ante structural wage differential:ln Ỹmi − ln Ỹsi =(ˆβ 0 m − ˆβ 0 s)X i +(ˆσ mvˆλmi − ˆσ svˆλsi ), i =1, ....n. (12)This measure has two components: <strong>the</strong> first term is <strong>the</strong> structural <strong>mobility</strong> wage ga<strong>in</strong>,represent<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> difference between systematic components of wages <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> alternativeas well as <strong>in</strong> current job, while <strong>the</strong> second term accounts for r<strong>and</strong>om differences notcaptured by wage equations but important <strong>in</strong> determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong> decision.The structural wage differential is <strong>the</strong>n substituted <strong>in</strong> (2) to obta<strong>in</strong> a structural probitfunction:I ∗ i = γ(ln Ỹmi − ln Ỹsi) − β 0 cX ci + ε i , i =1, ....n, (13)where: ε i = γ(ˆv mi − ˆv si ) − v i .Maximum likelihood estimation 18 of equation (13) allows us to obta<strong>in</strong> estimates of18 While we do not correct <strong>the</strong> variance covariance matrix of <strong>the</strong>se estimates for <strong>the</strong> fact that <strong>the</strong>16

<strong>the</strong> structural parameters related to <strong>the</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>cipal determ<strong>in</strong>ants of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>mobility</strong>choice. Estimation of <strong>the</strong> model requires identify<strong>in</strong>g exclusion restrictions. First,identification of wage equations parameters requires that at least one exogenous variabledeterm<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>mobility</strong> cost (X ci ) not be a determ<strong>in</strong>ant of wages (X i ) 19 . Second,identification of <strong>the</strong> wage differential parameter (γ) <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> structural probit equationrequires that at least one exogenous variable determ<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g wages (X i )beexcludedfrom<strong>the</strong> structural <strong>mobility</strong> cost (X ci ). Both <strong>the</strong>se conditions are satisfied by our underly<strong>in</strong>geconomic model. The reduced form selection <strong>in</strong>dex conta<strong>in</strong>s variables <strong>in</strong>cluded<strong>in</strong> X ci but excluded from X i . In particular, demographic <strong>in</strong>formation, <strong>pension</strong>, union<strong>and</strong> health coverage, expected <strong>pension</strong> loss, employer provided tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> firm sizedummies - all referr<strong>in</strong>g to first period of observation - are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> reduced formprobit but excluded from <strong>the</strong> wage equations provid<strong>in</strong>g appropriate <strong>and</strong> statisticallysignificant <strong>in</strong>struments to identify <strong>the</strong> coefficients of <strong>the</strong> latters. The wage equations<strong>in</strong>clude residential <strong>and</strong> location dummies, <strong>pension</strong>, union <strong>and</strong> health coverage dummiesas well as occupation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>dustry <strong>in</strong>formation - all referr<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>the</strong> second period job -which are excluded from <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> cost vector (X ci ). A fur<strong>the</strong>r identify<strong>in</strong>g covariancestructural wage differential is only an estimate of <strong>the</strong> true one (see Murphy <strong>and</strong> Topel, (1985), Greene(2000), or Peracchi (2001)), we do allow for heteroskedasticity by apply<strong>in</strong>g White’s Variance-CovarianceMatrix Correction.19 This avoids multicoll<strong>in</strong>earity between regressors <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> wage equation <strong>in</strong> case of l<strong>in</strong>earity of <strong>the</strong><strong>in</strong>verse Mills’ ratio. However, <strong>in</strong> pr<strong>in</strong>ciple identification could be atta<strong>in</strong>ed even only rely<strong>in</strong>g on nonl<strong>in</strong>earity of <strong>the</strong> latter.17

estriction, σ ms =0, accounts for <strong>the</strong> fact that sample observations cannot reflect <strong>the</strong>correlation between ln Y mi <strong>and</strong> ln Y si . Parametric estimation of sample selection modelsexploits <strong>the</strong> relationships between selection <strong>and</strong> outcome equations’ errors operat<strong>in</strong>gthrough distributional assumptions. In particular <strong>the</strong> jo<strong>in</strong>t normality assumption impliesl<strong>in</strong>ear relationships between selection <strong>and</strong> outcomes equations’ errors.Sampleselection models based on normality have been criticized on grounds of a seem<strong>in</strong>g lackof robustness of <strong>the</strong> parameters estimates to mispecification of <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed distributionalassumptions 20 . The most recent literature proposes a semiparametric approach,<strong>in</strong> that <strong>the</strong> outcome equation error conditional on <strong>the</strong> selected regime is not implicitly,(through distributional assumptions) or explicitly assumed to be a l<strong>in</strong>ear function of<strong>the</strong> selection’s equation error. Ra<strong>the</strong>r, this relationship is represented by an unknownfunction. However, recent evidence provided by Newey, Powell <strong>and</strong> Walker (1990) <strong>and</strong>Lanot <strong>and</strong> Walker (1998) <strong>in</strong>dicates that semiparametric methods give similar resultsto Heckman’s two-step parametric procedure. Although this evidence should be takencautiously, it provides us with a rationale for us<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> parametric approach.20 See Heckman <strong>and</strong> Honoré (1990).18

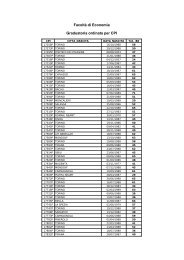

4 Data: The Survey of Income <strong>and</strong> Program Participation(SIPP)The Survey of Income <strong>and</strong> Program Participation (SIPP) is a set of <strong>in</strong>dependent shortpanels. In each survey, <strong>the</strong> data are collected every four months usually for 8 waves.As a result, a typical survey year covers a time span of 32 months. In each survey onecan differentiate between <strong>the</strong> core module <strong>and</strong> topical module <strong>in</strong>formation. The coredata are collected <strong>in</strong> every wave, while <strong>the</strong> topical module conta<strong>in</strong>s an additional set ofquestions address<strong>in</strong>g a particular research topic which does not require updat<strong>in</strong>g wi<strong>the</strong>ach wave. This paper focuses on <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> of males aged between 31 <strong>and</strong> 50 work<strong>in</strong>gat least 30 hours per week <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> private non-agricultural sector. We use <strong>the</strong> survey years1984, 1986, 1990 <strong>and</strong> 1992 for which detailed topical module <strong>in</strong>formation on <strong>pension</strong>s isavailable. The actual period covered by <strong>the</strong> pooled sample spans <strong>the</strong> 10 years between1984 <strong>and</strong> 1994. We start <strong>the</strong> empirical analysis by provid<strong>in</strong>g some prelim<strong>in</strong>ary evidenceon <strong>pension</strong> coverage rates <strong>and</strong> on <strong>the</strong> relationship between <strong>pension</strong>s, wages <strong>and</strong> job<strong>mobility</strong>.Table 1 presents evidence of a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> male <strong>pension</strong> coverage over <strong>the</strong> 1980s 21 ,while figures reported <strong>in</strong> Table 2 are consistent with <strong>the</strong> well known shift from def<strong>in</strong>edbenefit todef<strong>in</strong>ed contribution coverage, <strong>in</strong> particular toward 401(k) plans. One should21 Pension coverage is def<strong>in</strong>ed here as any form of employer provided <strong>pension</strong> coverage, withoutdist<strong>in</strong>ction between def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution, profit shar<strong>in</strong>g or 401(k) plans. Statisticsare computed on <strong>the</strong> selected sample.19

<strong>in</strong>terpret <strong>the</strong> latter table carefully as it reports <strong>in</strong>dividual coverage by plan type follow<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> structure of <strong>the</strong> SIPP <strong>pension</strong> questionnaires 22 . While 401(k) <strong>and</strong> profit shar<strong>in</strong>gplans are <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> usual def<strong>in</strong>ition of def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution coverage by <strong>the</strong> Bureauof Labor Statistics, <strong>the</strong> SIPP <strong>pension</strong> topical modules <strong>in</strong>clude specific questions for eachof <strong>the</strong>se plan categories. However, <strong>the</strong> question on profit shar<strong>in</strong>g coverage is not asked<strong>in</strong> 1992. This could expla<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> strong rise of <strong>the</strong> 401(k) share <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1992 <strong>pension</strong>coverage distribution. In order to adopt a consistent def<strong>in</strong>ition for each survey year,we <strong>in</strong>clude profit shar<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> 401(k) <strong>in</strong> our def<strong>in</strong>ition of def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution coverage.This group<strong>in</strong>g is mean<strong>in</strong>gful given <strong>the</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution nature of 401(k) <strong>and</strong> profitshar<strong>in</strong>g plans, although it confounds <strong>the</strong> different contributory rules between <strong>the</strong> plans.Although <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation necessary to differentiate quits from layoffs isavailable<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SIPP data, it does not appear to be very reliable. Therefore, we consider thata transition has occurred if we can identify a separation from <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>itial job dur<strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> one year time w<strong>in</strong>dow between wave 4 <strong>and</strong> wave 7. As po<strong>in</strong>ted out by Gustman<strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993), several variables, such as <strong>the</strong> r<strong>and</strong>omly assigned job numberor direct questions to employees, could be used to identify <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> SIPP data.However, <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>in</strong>formation derived from <strong>the</strong>se variables is often contradictory.Therefore, follow<strong>in</strong>g Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993), we adopt a broad def<strong>in</strong>ition of<strong>mobility</strong>, that def<strong>in</strong>esatransitiontoa<strong>new</strong>jobtohaveoccurredaslongasoneofthose22 See Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993).20

variables <strong>in</strong>dicates a job change.In Tables 3 to 6, we present basic statistics on <strong>mobility</strong> rates <strong>and</strong> wages by <strong>pension</strong>coverage status. A number of <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs emerges from <strong>the</strong>se tables. We f<strong>in</strong>d <strong>the</strong>well-known negative relationship between def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong> coverage <strong>and</strong> <strong>mobility</strong>rates. Non covered workers have <strong>mobility</strong> rates rang<strong>in</strong>g from 27.8 to 32.7 percent whilemuch lower <strong>mobility</strong> rates characterize <strong>pension</strong> covered workers.In particular, thisnegative relationship holds not only for workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong>s butalso for those covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans. Workers report<strong>in</strong>g double coveragehave <strong>the</strong> lowest <strong>mobility</strong> rate <strong>in</strong> all survey years.Pension covered workers, ei<strong>the</strong>r stayers or movers, are on average better paid thanworkers without <strong>pension</strong>s <strong>in</strong> all <strong>the</strong> survey years 23 . This could reflect ei<strong>the</strong>r workerspecific or job specific attributes. If <strong>the</strong> entire wage differential between workers with<strong>and</strong> without <strong>pension</strong> was due to <strong>in</strong>dividual characteristics, such as unmeasured ability,<strong>the</strong> wage on any alternative job would be identical to <strong>the</strong> current one, <strong>and</strong> no wage losseswould result from a move. If <strong>the</strong> wage on <strong>the</strong> current job was <strong>in</strong>stead just a reflection ofjob specific ra<strong>the</strong>r than personal characteristics, identical workers would be paid moreon <strong>pension</strong> jobs than on non-<strong>pension</strong> jobs, ei<strong>the</strong>r as a result of rent-shar<strong>in</strong>g or because ofsome productivity enhanc<strong>in</strong>g-scheme requir<strong>in</strong>g efficiency wage payments. Raw evidencefrom tables 3 to 7 is consistent with <strong>the</strong> latter <strong>in</strong>terpretation. In particular, table 723 This gap is particularly large for people report<strong>in</strong>g double coverage.21

<strong>in</strong>dicates that most (86 percent) <strong>pension</strong> covered movers lose <strong>pension</strong> coverage 24 <strong>and</strong>thus move to jobs associated with lower average wages.5 Empirical ResultsThe model is estimated on <strong>the</strong> pooled sample of <strong>the</strong> four surveys with a set of paneldummies 25 .Table 8 reports results from first-step reduced form probit estimation.The estimates provide very limited <strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>the</strong> validity of <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>oreticalframework captured by equations (2)− (4), giv<strong>in</strong>g only <strong>the</strong> total effect of each regressoron <strong>the</strong> probability of job <strong>mobility</strong>. Moreover, <strong>the</strong> sign of most variables <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>reduced form probit equation is a priori uncerta<strong>in</strong>, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> estimated coefficient valuesare difficult to <strong>in</strong>terpret. The reduced form estimates are however <strong>the</strong> necessary firststep to derive Heckman’s (1979) two-steps consistent estimates of <strong>the</strong> wage equations.5.1 Selection Corrected Wage EquationsIn Table 9 we present <strong>the</strong> estimated sample-selection corrected wage equations formovers <strong>and</strong> stayers. The dependent variable is <strong>the</strong> log of hourly wages expressed <strong>in</strong>1992 constant dollars. The reported t-values are computed correct<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> variance-24 Information on <strong>pension</strong> coverage on <strong>the</strong> <strong>new</strong> job is collected by means of a topical module <strong>in</strong> wave7 only for <strong>the</strong> 1984 <strong>and</strong> 1986 survey years. Alternatively, no wave 7 <strong>pension</strong> topical module was asked<strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1990s surveys. Pension coverage <strong>in</strong> wave 7 is an important variable <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estimation of ourempirical model. We impute this variable for <strong>the</strong> 1990s runn<strong>in</strong>g a probit for <strong>pension</strong> coverage statuschange among movers <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1980s.25 We have tested <strong>the</strong> pool<strong>in</strong>g of data from different comb<strong>in</strong>ations of panels <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong> no case <strong>the</strong> datareject <strong>the</strong> null hypo<strong>the</strong>sis of common parameters. The year dummy variables are not reported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>tables.22

covariance matrix of <strong>the</strong> estimated coefficients with <strong>the</strong> Heckman procedure 26 .Mostof<strong>the</strong> selection of <strong>in</strong>dividuals <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong> observed mover/stayer status seems to come fromunobservables, although <strong>the</strong> selection effect captured by ˆσ mvˆλmi <strong>and</strong> ˆσ svˆλsi is negativeboth for movers <strong>and</strong> for stayers. The coefficients of ”measurable” variables obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> wage equation (ei<strong>the</strong>r for stayers or movers) confirm a priori expectations. Moreprecisely, be<strong>in</strong>g white, married, professional, employed <strong>in</strong> a medium or large firm (over100employees)aswellas<strong>in</strong>amanufactur<strong>in</strong>gfirm <strong>and</strong> liv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a SMSA are all significantlyassociated with higher earn<strong>in</strong>gs. Similarly, <strong>the</strong> returns to education are positive<strong>and</strong> statistically significant.The wage equations <strong>in</strong>clude dummy variables for def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>and</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution<strong>pension</strong> coverage. These provide a test for <strong>the</strong> existence of a wage premiumaccru<strong>in</strong>g to <strong>pension</strong> covered workers after controll<strong>in</strong>g for <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>and</strong> job specificcharacteristics. The regression results corroborate <strong>the</strong> correlation reported <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> descriptivestatistics: be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a <strong>pension</strong> covered job (ei<strong>the</strong>r <strong>in</strong> def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit ordef<strong>in</strong>edcontribution plan) generally gives positive <strong>and</strong> statistically significant returns <strong>in</strong> wages.The regression results reveal that <strong>the</strong> premium associated with be<strong>in</strong>g covered by a def<strong>in</strong>edbenefit plan(orbyadef<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plan) is much smaller for stayers thanfor movers. Interest<strong>in</strong>gly, a similar result is found for both employees with health cover-26 See Heckman (1979). The rout<strong>in</strong>e for computation of <strong>the</strong> correct st<strong>and</strong>ard errors, programmed <strong>in</strong>Stata - version 7 - is available upon request from <strong>the</strong> authors. Reported t-values followed by one (two)asterisks are significant at 90 (95) percent level.23

age <strong>and</strong> those member of a union. The positive returns to <strong>pension</strong> coverage contradict<strong>the</strong> predictions of <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>ory of equaliz<strong>in</strong>g differences <strong>and</strong> of <strong>the</strong> spot contract <strong>pension</strong>literature 27 .5.2 Structural Probit EstimatesThe f<strong>in</strong>al step <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> procedure is <strong>the</strong> maximum likelihood estimation of <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dividualprobability of <strong>in</strong>terfirm job <strong>mobility</strong>, as expressed by <strong>the</strong> structural probit equation(13) 28 . This requires computation of <strong>the</strong> predicted log wage differential for each <strong>in</strong>dividualgiven his/her own characteristics, as <strong>in</strong> (12). The structural probit allows us todisentangle <strong>the</strong> coefficients of <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> costs equation from effects work<strong>in</strong>g throughwages. The estimated structural equation has a significant power <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong>decisions. A likelihood ratio test strongly rejects <strong>the</strong> null hypo<strong>the</strong>sis that all slopecoefficients are equal to zero. The parameter estimates reported <strong>in</strong> Table 10 represent<strong>the</strong> effect of a one unit change <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>in</strong>dependent variable on <strong>the</strong> probability of job<strong>mobility</strong>, evaluated at <strong>the</strong> sample mean 29 .Generally, <strong>the</strong> coefficient estimates are consistent with a priori expectation. In particular,home owners are less likely to move.Experience <strong>and</strong> family size negatively27 See Bulow (1982).28 In <strong>the</strong> reported estimates, <strong>the</strong> base case <strong>in</strong>dividual is white, not married, without children, housetenant, not enrolled <strong>in</strong> any <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>pension</strong> plan nor <strong>in</strong> any employer provided <strong>pension</strong> or health<strong>in</strong>surance plan, not receiv<strong>in</strong>g firm specific tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, not unionized, work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a small firm.29 St<strong>and</strong>ard errors are derived from a st<strong>and</strong>ard White variance covariance matrix. Reported t-valuesfollowed by one (two) asterisks are significant at 90 (95) percent level.24

affect <strong>mobility</strong>. Similarly, be<strong>in</strong>g married, hav<strong>in</strong>g children under 18, work<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> a largefirm <strong>and</strong> receiv<strong>in</strong>g employer provided tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g have a negative impact on job <strong>mobility</strong>.However, <strong>the</strong>se estimates are not statistically significant at any st<strong>and</strong>ard level.Our model assumes that an <strong>in</strong>dividual’s decision to change jobs responds positively towage differential def<strong>in</strong>ed as her/his lifetime earn<strong>in</strong>g ga<strong>in</strong>s from mov<strong>in</strong>g. The positive <strong>and</strong>highly significant wage differentials estimate constitutes a robust evidence <strong>in</strong> supportof this model.However, our model suggests that <strong>the</strong> response to wage differentialsaccounts on average for a modest 1.7 percent of <strong>the</strong> observed <strong>mobility</strong>. In our model,<strong>the</strong> effect of <strong>pension</strong> coverage is captured by <strong>pension</strong> coverage dummies (ei<strong>the</strong>r def<strong>in</strong>edbenefit ordef<strong>in</strong>ed contribution). In addition, our specification also <strong>in</strong>cludes a <strong>pension</strong>loss variable to disentangle <strong>the</strong> effect of backload<strong>in</strong>g of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong>son<strong>mobility</strong>.Our results reveal that be<strong>in</strong>g employed <strong>in</strong> a <strong>pension</strong> covered job, regardless of <strong>the</strong>nature of <strong>the</strong> plan, significantly reduces <strong>the</strong> probability of mov<strong>in</strong>g by about 20 percent.On <strong>the</strong> contrary, our estimation results suggest that on average, <strong>pension</strong> backload<strong>in</strong>gfur<strong>the</strong>r reduces <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong> covered workers only by 0.5percent. In addition, <strong>the</strong> coefficient is not statistically significant. This result givesvery little support to <strong>the</strong> implicit contract view that potential <strong>pension</strong> wage losses deter<strong>mobility</strong>. Our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g that <strong>the</strong> effect of def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans is equally importantthan <strong>the</strong> overall effect of def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans <strong>in</strong> shap<strong>in</strong>g <strong>mobility</strong> decisions re<strong>in</strong>forces25

this conclusion. Indeed, if backload<strong>in</strong>g loss were <strong>the</strong> ma<strong>in</strong> cause of <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>mobility</strong> of<strong>pension</strong> covered workers, one would observe a much larger <strong>mobility</strong> rate among workerscovered by def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans than among those covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefitplan.Our estimated effect of <strong>the</strong> <strong>pension</strong> variables seems to corroborate earlier f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gsreported by Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993). These authors argue that ra<strong>the</strong>r than<strong>pension</strong> losses, it is <strong>the</strong> existence of a compensation premium associated with <strong>pension</strong>covered jobs which mostly affects <strong>mobility</strong>. Our f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>the</strong> existence of positive wagereturns accru<strong>in</strong>g to workers covered by employer provided <strong>pension</strong> is fur<strong>the</strong>r evidencesupport<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> view that compensation premiums are an important factor <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g<strong>the</strong> lower <strong>mobility</strong> rate of <strong>pension</strong> covered workers. Additional support for <strong>the</strong> idea thatfr<strong>in</strong>ge benefits associated with <strong>pension</strong> covered jobs play an important role <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> job<strong>mobility</strong> decision is found <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> estimated coefficients on <strong>the</strong> health <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong>union coverage variables, which are found to be negative <strong>and</strong> statistically significant.Previous research on <strong>the</strong> question of whe<strong>the</strong>r workers covered by employer providedhealth <strong>in</strong>surance are ”locked” <strong>in</strong>to <strong>the</strong>ir jobs has produced contradictory results despite<strong>the</strong> widespread similarity <strong>in</strong> methodological approaches <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> use of similar datasets.In particular, two previous studies have used SIPP data: while Penrod (1995) produceslittle empirical evidence of a <strong>mobility</strong> imped<strong>in</strong>g role of employer provided health <strong>in</strong>surance,Buchmueller <strong>and</strong> Valletta (1996) f<strong>in</strong>d evidence of job lock among women, but not26

among men 30 . While not address<strong>in</strong>g explicitly <strong>the</strong> ”job lock” hypo<strong>the</strong>sis <strong>and</strong> its identificationstrategies, our results provide fur<strong>the</strong>r evidence that employer provided health<strong>in</strong>surance represents a valuable fr<strong>in</strong>ge benefit toworkerswhichsignificantly deters job<strong>mobility</strong>.As mentioned earlier, <strong>the</strong> Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced, start<strong>in</strong>g from 1989,<strong>the</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g period required to be entitled to any <strong>pension</strong> benefit. This policy changereduced <strong>the</strong> loss <strong>in</strong>curred by workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans associated witha job change 31 .Therefore, one should expect a lower impact of <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong>loss on mov<strong>in</strong>g after <strong>the</strong> implementation of <strong>the</strong> reform. We try to capture this effectby predict<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> change <strong>in</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> that can be attributed to <strong>the</strong> policy change forworkers who have been <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> same job between five <strong>and</strong> ten years <strong>and</strong> who are coveredby def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plan <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1992 survey year. Our basic results are reported <strong>in</strong> Table12. We f<strong>in</strong>d that <strong>the</strong> effect of <strong>the</strong> reform on <strong>the</strong> average <strong>pension</strong> loss is importantreduc<strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> later by 46 percent, or $5430. However, our model also suggests that each1000 dollars of <strong>pension</strong> loss reduces <strong>the</strong> probability of switch<strong>in</strong>g jobs by about 0.03percent. Thus, on average <strong>the</strong> reform <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>the</strong> <strong>mobility</strong> probability by only 0.015percent. This result suggests that <strong>the</strong> dramatic reduction of <strong>the</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g period imposed30 See Currie <strong>and</strong> Madrian (1999) for a review of <strong>the</strong> ”job lock” literature.31 The <strong>portability</strong> loss variable is computed on a typical f<strong>in</strong>alsalarydef<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plan, whosecharacteristics are reported <strong>in</strong> table 11. Table 11 also reports <strong>the</strong> actuarial assumptions needed for <strong>the</strong>calculation.27

y <strong>the</strong> Tax Reform Act had an <strong>in</strong>significant impact on <strong>mobility</strong> choices.6 ConclusionsThis paper provides an empirical analysis of occupational <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>United States, grounded on a structural econometric model of <strong>in</strong>terfirm job <strong>mobility</strong>.We f<strong>in</strong>d that workers covered by def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit <strong>pension</strong>s are significantly less likely tomove. However, <strong>the</strong> potential <strong>portability</strong> loss aris<strong>in</strong>g to workers leav<strong>in</strong>g a def<strong>in</strong>ed benefitplan does not seem to play a significant role <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong> choices. Ourresults also reveal that def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution plans, despite of <strong>the</strong>ir complete <strong>portability</strong>,are as important as def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit plans <strong>in</strong> reduc<strong>in</strong>g job <strong>mobility</strong>. Employer providedhealth <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> union coverage are also found to play a major role <strong>in</strong> deterr<strong>in</strong>g job<strong>mobility</strong>. As <strong>in</strong> Gustman <strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993), <strong>the</strong>se results underm<strong>in</strong>e <strong>the</strong> argumentthat <strong>the</strong> lack of <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> is a key factor <strong>in</strong> expla<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g <strong>the</strong> lower <strong>mobility</strong> rateobserved among workers <strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong> covered jobs. Evidence of compensation premiums<strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong> <strong>and</strong> health <strong>in</strong>surance covered jobs fur<strong>the</strong>r supports <strong>the</strong> alternative view thatworkers <strong>in</strong> ”good jobs” are simply less likely to move. From a policy perspective, <strong>the</strong>seresults cast doubt on <strong>the</strong> effectiveness of reforms aimed at improv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>labour</strong> marketefficiency through <strong>portability</strong> measures.In <strong>the</strong> context of a national <strong>pension</strong> policy focused on <strong>the</strong> reduction of social securitybenefits, a more conv<strong>in</strong>c<strong>in</strong>g argument <strong>in</strong> favour of <strong>in</strong>creased <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> would28

e to ensure retirement <strong>in</strong>come adequacy for multiple job changers. The effect of <strong>the</strong>reduction <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g period implemented with <strong>the</strong> 1986 Tax Reform Act clearlyillustrates <strong>the</strong> latter po<strong>in</strong>t. Although we found that <strong>the</strong> reform did not affect <strong>mobility</strong>,<strong>the</strong> average <strong>pension</strong> loss of workers affected by <strong>the</strong> reform was reduced by 46 percent.On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r h<strong>and</strong>, one may question <strong>the</strong> need to <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>pension</strong> <strong>portability</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce<strong>pension</strong> covered jobs are also associated with a higher remuneration levels (Gustman<strong>and</strong> Ste<strong>in</strong>meier (1993)). If one is concerned with <strong>the</strong> adequacy of <strong>pension</strong> <strong>in</strong>come afterretirement, a more equitable policy goal may be to address <strong>the</strong> observed decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><strong>pension</strong> coverage.29

ReferencesAllen, S., Clark, R., McDermed, A., (1988). Why do <strong>pension</strong>s reduce <strong>mobility</strong>?NBER Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper # 2509.Allen, S., Clark, R., McDermed, A., (1993). Pensions, bond<strong>in</strong>g <strong>and</strong> lifetime jobs.Journal of Human Resources 28 (3), 502-517.Andrietti, V., (2001). Occupational <strong>pension</strong>s <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>terfirm job <strong>mobility</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong>European Union. Evidence from <strong>the</strong> ECHPanel Survey. Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper # 05 -2001, Center for Research on Pensions <strong>and</strong> Welfare Policies.Borjas, G.J., Rosen, S., (1980). Income prospects <strong>and</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong> of younger men.Research <strong>in</strong> Labor Economics 3, 159-181.Buchmuller, T.C., Valletta, R.G., (1996). The effects of employer-provided health<strong>in</strong>surance on worker <strong>mobility</strong>. Industrial <strong>and</strong> Labor Relations Review 49, 439-455.Bulow, J., (1982). What are corporate <strong>pension</strong> liabilities? Quarterly Journal ofEconomics 97, 435-452.Currie, J., Madrian, B.C., (1999). Health, health <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> labor market.InAshenfelter, O., Card, D., (Eds.) H<strong>and</strong>book of Labor Economics, Volume 3.Amsterdam, Elsevier Science, pp. 3309-3415.30

Even, W.E., Macpherson, D., (1994). Why did male <strong>pension</strong> coverage decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> 1980s? Industrial <strong>and</strong> Labor Relations Review 47, 439-453.Greene, W. (1997) Econometric Analysis, 3rd Edition. Prentice Hall, EnglewoodCliffs, New Jersey.Gustman, A.L., Ste<strong>in</strong>meier, T.L., (1987). Pensions, efficiency wages <strong>and</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong>.NBER Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper # 2426.Gustman, A.L., Ste<strong>in</strong>meier, T.L., (1993). Pension <strong>portability</strong> <strong>and</strong> labor <strong>mobility</strong>.Evidence from <strong>the</strong> Survey of Income <strong>and</strong> Program Participation. Journal of PublicEconomics 50, 299-323.Gustman, A.L., Ste<strong>in</strong>meier, T.L., (1995). Pension Incentives <strong>and</strong> Job Mobility.Kalamazoo, Michigan: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.Heckman, J., (1979). Sample selection as a specification error. Econometrica 41,153-161.Heckman, J., Honoré, B. (1990). The empirical content of <strong>the</strong> Roy model. Econometrica58 (5), 1121-1149.Ippolito, R., (1985). The labor contract <strong>and</strong> true economic <strong>pension</strong> liabilities.American Economic Review 75, 1031-1043.31

Ippolito, R., (1987). Why federal workers don’t quit. Journal of Human Resources22 (2), 281-299.Ippolito, R., (1997). Pension Plans <strong>and</strong> Employee Performance. Chicago, Universityof Chicago Press.Lanot, G., Walker, I., (1998). The union/non-union wage differential. An applicationof semi-parametric methods. Journal of Econometrics 88, 327-349.McLaughl<strong>in</strong>, K.G., (1991). A <strong>the</strong>ory of quits <strong>and</strong> layoffs wi<strong>the</strong>fficient turnover.Journal of Political Economy, 91(1),1-29.Mitchell, O.S., (1983). Fr<strong>in</strong>dgeg benefits <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> cost of chang<strong>in</strong>g jobs. Industrial<strong>and</strong> Labor Relations Review 37, 70-78.Murphy, K. <strong>and</strong> Topel, R. (1985). Estimation <strong>and</strong> <strong>in</strong>ference <strong>in</strong> two-step econometricmodels. Journal of Bus<strong>in</strong>ess <strong>and</strong> Economic Statistics, 3, 370-379.Newey, W.K., Powell, J., Walker, J. (1990). Semiparametric estimation of selectionmodels: Some empirical results.” American Economic Review, Papers <strong>and</strong>Proceed<strong>in</strong>gs 80(2), 324-328.Penrod, J.R., (1995). Health care costs, health <strong>in</strong>surance <strong>and</strong> job <strong>mobility</strong>. Mimeo,University of Michigan.Peracchi, F. (2001). Econometrics. Chilchester, John Wiley <strong>and</strong> Sons.32

Wolf, D.A., Levy, F., (1984). Pension coverage, <strong>pension</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> distributionof job tenures. In: Aaron, H. <strong>and</strong> G. Burtless (Eds) Retirement <strong>and</strong> EconomicBehavior. Wash<strong>in</strong>gton def<strong>in</strong>ed contribution, Brook<strong>in</strong>gs, pp. 23-61.33

Table 1: Pension Coverage by Survey YearsSIPP84 SIPP86 SIPP90 SIPP92Not Covered 31.19 34.63 37.46 35.44Pension Covered 68.81 65.37 62.54 64.56Source: Our elaboration on SIPP data.Table 2: Pension Coverage by Plan Type <strong>and</strong> Survey YearsSIPP 84 SIPP 86 SIPP 90 SIPP 92DB plan 39.53 31.38 19.62 23.72DC plan Profit Shar<strong>in</strong>g 14.27 15.13 10.45 N/A401k 3.50 5.59 13.79 14.88O<strong>the</strong>r 5.88 4.70 3.29 7.69Total DC 23.65 25.42 27.53 22.57DB + DC 5.63 8.58 15.40 18.28Not Covered 31.19 34.63 37.46 35.44Source: Our elaboration on SIPP data.Table 3: Job Mobility, Wages <strong>and</strong> Pension Coverage 1984No Pension DB DC DB+DCStayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer MoverMobility Rate 29.1 12.1 15.3 9Hourly wage 12.8 12.6 16.4 16.1 16.4 15.5 20.4 20.5∆Wage % 0.6 2.9 -0.7 3.8 1.1 1.6 -0.8 1.4Source: Our elaboration on SIPP data34

Table 4: Job Mobility, Wages <strong>and</strong> Pension Coverage 1986No Pension DB DC DB+DCStayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer MoverMobility Rate 27.8 12.2 13 8.4Hourly wage 12.9 11.6 15.8 15.2 17.3 15.8 20 16.9∆Wage % 4.4 9.6 -0.5 -4.8 -6.2 -0.5 0.2 -3.4Source: Our elaboration on SIPP dataTable 5: Job Mobility, Wages <strong>and</strong> Pension Coverage 1990No Pension DB DC DB+DCStayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer MoverMobility Rate 32.7 15.8 15.3 10.9Hourly wage 12.7 11.1 15.9 14.6 16.5 16.2 18.5 16.6∆Wage % 0.4 2.3 0.7 -1.9 -0.6 -1.8 -0.2 -1Source: Our elaboration on SIPP dataTable 6: Job Mobility, Wages <strong>and</strong> Pension Coverage 1992No Pension DB DC DB+DCStayer Move Stayer Mover Stayer Mover Stayer MoverMobility Rate 30.9 13.6 14.3 8.1Hourly wage 12.4 11.9 15.5 14.9 16.4 15.5 20.4 20.4∆Wage % 0.8 2 -0.1 -7.9 1.1 1.6 -0.8 1.4Source: Our elaboration on SIPP dataTable 7: Pension coverage of job movers <strong>in</strong> SIPP 84 <strong>and</strong> SIPP 86Period 2 (wave 7)Period 1 (wave 4) Not covered CoveredNot covered 90% 10%Covered 86% 14%Source: Our elaboration on SIPP data.35

Table 8: Reduced Form Probit EquationdF/dx zHous<strong>in</strong>g tenure -0.01772** -2.3Married 0.00046 0.05Family size -0.00909 -0.93Children under 18 0.00574** 2.13Expected <strong>portability</strong> loss -0.00054 -0.06Employer DB <strong>pension</strong> plan 1 -0.05650** -5.39Employer DB <strong>pension</strong> plan 2 0.39196** 18.22Employer DC <strong>pension</strong> plan 1 -0.37144** -32.64Employer DC <strong>pension</strong> plan 2 0.32742** 19.39Employer health <strong>in</strong>surance 1 -0.36526** -32.99Employer health <strong>in</strong>surance 2 -0.04538** -4.4Employer tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g -0.03937** -3.83Employer size > 100 0.01769* 1.95Union member1 0.00133 0.18Union member 2 0.05036** 3.26Experience 0.00745 0.54Experience squared -0.00023 -0.07Education -0.00001 -0.07Manufactur<strong>in</strong>g 0.00431** 2.82Managers <strong>and</strong> professionals -0.02554** -3.56White collars -0.00158 -0.16Non-white -0.00749 -0.92Smsa 0.01017 1.5North-east 0.01362 1.41South 0.01663* 1.94West 0.01319 1.34LR 3767.69Pseudo R2 0.3783Number of observations 10.19936

Table 9: Wage Equation for Stayers <strong>and</strong> MoversStayerMovert-testt-testExperience 0.0129** 2.78 0.0155 1.47Experience squared -0.0001 -1.24 -0.0003 -1.03Education 0.0577** 24.88 0.0533** 10.06Non-white -0.1892** -12.17 -0.2032** -6.08Employer DB <strong>pension</strong> plan 2 0.0772** 4.50 0.2773** 4.08Employer DC <strong>pension</strong> plan 2 0.0752** 4.28 0.2799** 4.18Employer health <strong>in</strong>surance 2 0.1315** 7.71 0.2516** 9.96Manufactur<strong>in</strong>g 0.0243** 2.34 0.0748** 2.88Union member 2 0.0835** 6.61 0.1495** 4.62Managers <strong>and</strong> professionals 0.1794** 12.58 0.2474** 7.53White collars -0.0072 -0.57 -0.0421 -1.50Smsa 0.1126** 11.03 0.0799** 3.40North-east 0.0373** 2.72 0.0896** 2.75South 0.0058 0.47 -0.0125 -0.43West 0.0814** 5.67 0.0504 1.54Lambda 0.2359** 4.62 -0.1050** -4.47Constant 1.3954** 21.36 1.3407** 9.82F-test 182.41 44.94Adj. R2 0.2948 0.2997Root MSE 0.41756 0.47796Number of observations 8247 195237

Table 10: Structural Form Probit EquationdF/dx zWage differential 1.3480** 41.62Hous<strong>in</strong>g tenure -0.0096 -1.21Married -0.0043 -0.42Non-white 0.0362** 3.19Family size -0.0028 -0.98Children under 18 -0.0067 -0.69Union 1 -0.0840** -10.56Expected <strong>portability</strong> loss * 1000 -0.0003 -1.2Employer DB <strong>pension</strong> plan 1 -0.2021** -17.37Employer DC <strong>pension</strong> plan 1 -0.2037** -25.07Empoyer health <strong>in</strong>surance 1 -0.1027** -10.48Employer tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g -0.0125 -1.42Employer size > 100 -0.0052 -0.66Experience -0.0003 -0.09Experience squared 0.0001 1.06Education -0.0017 -1.18Log-likelihood -3373.98Wald Chi2 3211.03Pseudo R2 0.3224Number of observations 10.199Table 11: Assumptions for Portability Loss ComputationAnnual Accrual Rate 1.5%Pensionable WageF<strong>in</strong>al WageNormal Retirement Age 62Expected Inflation Rate 3%Expected Nom<strong>in</strong>al Wage Growth Rate 5%Post-Retirement Indexation 0.33%Early Leavers’ IndexationnoNom<strong>in</strong>al Discount Rate 5%Inflation Adjusted Discount Rate 4%Table 12: Predicted effect of <strong>the</strong> change <strong>in</strong> vest<strong>in</strong>g rule on <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>mobility</strong>Def<strong>in</strong>ed benefit covered movers <strong>in</strong> SIPP 1992, 5 ≤ job tenure < 10Average pre-reform <strong>pension</strong> wage loss $17.189Average post-reform <strong>pension</strong> wage loss $11.745∆ <strong>in</strong> <strong>pension</strong> wage loss -46.3%∆ on predicted <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>mobility</strong> -0.015%Dollar amounts are expressed <strong>in</strong> 1992 dollars.38

Our papers can be downloaded at:http://cerp.unito.itCeRP Work<strong>in</strong>g Paper Series:N° 1/00 Guido Menzio Opt<strong>in</strong>g Out of Social Security over <strong>the</strong> Life CycleN° 2/00 Pier Marco FerraresiElsa ForneroN° 3/00 Emanuele BaldacciLuca IngleseSocial Security Transition <strong>in</strong> Italy: Costs, Distorsions<strong>and</strong> (some) Possible CorrectionLe caratteristiche socio economiche dei <strong>pension</strong>ati <strong>in</strong>Italia. Analisi della distribuzione dei redditi da<strong>pension</strong>e (only available <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> Italian version)N° 4/01 Peter Diamond Towards an Optimal Social Security DesignN° 5/01 V<strong>in</strong>cenzo Andrietti Occupational Pensions <strong>and</strong> Interfirm Job Mobility <strong>in</strong><strong>the</strong> European Union. Evidence from <strong>the</strong> ECHP SurveyN° 6/01 Flavia Coda Moscarola The Effects of Immigration Inflows on <strong>the</strong>Susta<strong>in</strong>ability of <strong>the</strong> Italian Welfare StateN° 7/01 Margherita Borella The Error Structure of Earn<strong>in</strong>gs: an Analysis onItalian Longitud<strong>in</strong>al DataN° 8/01 Margherita Borella Social Security Systems <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> Distribution ofIncome: an Application to <strong>the</strong> Italian CaseN° 9/01 Hans Blommeste<strong>in</strong> Age<strong>in</strong>g, Pension Reform, <strong>and</strong> F<strong>in</strong>ancial MarketImplications <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> OECD AreaN° 10/01 V<strong>in</strong>cenzo Andrietti <strong>and</strong>V<strong>in</strong>cent Hildebr<strong>and</strong>Pension Portability <strong>and</strong> Labour Mobility <strong>in</strong> <strong>the</strong> UnitedStates. New Evidence from <strong>the</strong> SIPP Data