Contents - Medicinski Fakultet u Sarajevu - University of Sarajevo

Contents - Medicinski Fakultet u Sarajevu - University of Sarajevo

Contents - Medicinski Fakultet u Sarajevu - University of Sarajevo

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

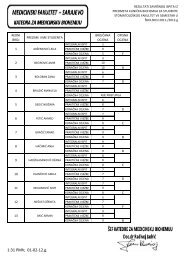

FOLIA MEDICA FACULTATIS MEDICINAE UNIVERSITATIS SARAEVIENSISJournal <strong>of</strong> Medical Faculty <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Bosnia&Herzegovina2011 Vol. 46, No. 1<strong>Contents</strong>ORIGINAL PAPERSSerotyping Streptococcus Pyogenes <strong>of</strong> Preschool and Primary School ChildrenAida Koso, Šukrija Zvizdić . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3Frequency and Sex Distribution <strong>of</strong> Omphalocele in Surgically Treated Infantsin <strong>Sarajevo</strong> Region <strong>of</strong> Bosnia And HerzegovinaSelma Aličelebić, Amela Vilić . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Acute Toxicity Study <strong>of</strong> Combination <strong>of</strong> Tridecactide and Met-EnkephalinMaida Rakanovic-Todic, Nedzad Mulabegovic, Fahir Becic, Mirjana Mijanovic,Svjetlana Loga-Zec, Jasna Kusturica, Lejla Burnazovic-Ristic, Aida Kulo, Elvedina Kapic . . . . . . . . . . . 13Brucellosis – Emerging Zoonosis in Bosnia and HerzegovinaSajma Dautović-Krkić, Edina Bešlagić, Meliha Hadžović-Čengić, Snježana Mehanić,Adnan Karavelić, Sead Ahmetagić, Ibrahimpašić Nevzeta, Eldira Hadžić, Ivo Curić,Nazif Derviškadić, Janja Bojanić. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22Diagnostic Significance <strong>of</strong> Platelet Count in Patients With Lung CancerSelma Arslanagić, Hasan Žutić, Nedžad Mulabegović,Rusmir Arslanagić, Reuf Karabeg, Naima Arslanagić. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28Frequency and Antibiotic Susceptibility <strong>of</strong> Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus(MRSA) in Canton <strong>Sarajevo</strong>; Bosnia and HerzegovinaEdina Bešlagić , Sabaheta Bektaš, Mufida Aljičević, Snježana Balta, Sadeta Hamzić . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Detection <strong>of</strong> Cytokines IFN γ, TNF α and IL 10 in Acute and Chronic Human ToxoplasmosisSabaheta Bektaš, Snježana Balta , Mufida Aljičević, Edina Bešlagić . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41REVIEW PAPERSUse Of Homeostatic Model Assessment In Managing Type 2 DiabetesDamira Kadić, Davorka Dautbegović-Stevanović . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48Paragangliomas <strong>of</strong> the NeckJasminka Alagić-Smailbegović, Kamenko Šutalo, Edina Hadžić . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54Recommendations for Treatment <strong>of</strong> Active and Latent Tuberculosis Before and DuringThe Tumor Necrosis Factor Antagonists Therapy in Bosnia and HerzegovinaHasan Žutić, Nenad Prodanović, Šekib Sokolović, Mladen Duronjić,Suada Mulić Bačić, Nađa Borovac, Nedžad Mulabegović . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60Preporuke za tretman aktivne i latentne tuberkuloze prije i tokom terapije antagonistimafaktora tumorske nekroze u Bosni i HercegoviniHasan Žutić, Nenad Prodanović, Šekib Sokolović, Mladen Duronjić,Suada Mulić Bačić, Nađa Borovac, Nedžad Mulabegović . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73Instructions to authors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85

FOLIA MEDICA FACULTATIS MEDICINAE UNIVERSITATIS SARAEVIENSISJournal <strong>of</strong> Medical Faculty <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Bosnia&HerzegovinaEditor-in-ChiefNedžad MulabegovićExecute EditorMaida Rakanović TodićEditorial BoardJasminko HuskićDamir AganovićAmela BegićSlavica IbruljSemra ČavaljugaNermin SarajlićAlmira Hadžović DžuvoLejla Burnazović RistićRadivoj JadrićLectorised byDubravko VaničekTechnical Editor and PrintSaVart <strong>Sarajevo</strong>DTPNarcis PozderacAdress <strong>of</strong> the Editorial board:71000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Čekaluša 90Bosnia & HerzegovinaPhone: 00387 33 226 472Fax: 00387 33 203 670Published byFaculty <strong>of</strong> Medicine,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>www.mf.unsa.ba/foliaISSN 0352-9630EBSCO Publishing (EP) USAhttp://www.epnet.comPrinted on acid-free paper

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:1-8Figure 1. Representation <strong>of</strong> certain M typesAmong patients who had the streptococciisolated M typing in relation to sex andage there are no statistically significant differencesin M - types <strong>of</strong> streptococci.Also was done the testing blood samplesfor the presence <strong>of</strong> anti-streptolysin Oantibody (ASO) titer in 19 or 27.1% <strong>of</strong> respondents.The results which derived fromASO tests indicate that it is positive in 9 or47.4% <strong>of</strong> respondents, and that its value <strong>of</strong>200 were found in 3 or 33.3% <strong>of</strong> total positivetests, and the titer <strong>of</strong> 400 at 6 or 66.7%<strong>of</strong> total ASO positive tests. Most patientswith positive findings ASO 200 have theM-6 type, and most patients with ASO value<strong>of</strong> 400 is M-3 type. ASO value 400 is foundwith M-1 and M-6 type.DiscussionThis study <strong>of</strong> severe forms <strong>of</strong> streptococcaldisease came to the conclusion that it occurin cycles that are caused by certain prevalenttypes <strong>of</strong> streptococci. European studies haveshown that the distribution <strong>of</strong> ß-streptococcusgroup A haemolyticus is representeddifferently in different countries. In severalEuropean countries, the types <strong>of</strong> M-1, M-3and M-28 predominates, but there is a tendency<strong>of</strong> increase <strong>of</strong> new invasive types (M-77, M-81, M-82, M-89) (17-19). It is knowthat in certain regions <strong>of</strong> the United States,during the twentieth century, was found alarge number <strong>of</strong> patients with acute rheumaticfever, <strong>of</strong> which had as a previous illness,infection with Streptococcus pyogenes,type M-1, M-3 and M 18 (20). Reducementin the incidence <strong>of</strong> rheumatic fever in theUnited States explains the changing representation<strong>of</strong> virulent strains <strong>of</strong> streptococcus-reducednumber rheumatic types(significantly reduce the number <strong>of</strong> isolatedtype M-3, M-5 and M-6 streptococci, from49.7% to 10.6%) (21). Tests in the Republic<strong>of</strong> Croatia indicate that the occurrence <strong>of</strong>severe forms <strong>of</strong> diseases caused by streptococciand the occurrence <strong>of</strong> complicationsare associated with the isolation and identification<strong>of</strong> highly virulent strains <strong>of</strong> mucousM-serotypes <strong>of</strong> Streptococcus pyogenes(22). Testing (during the six year period) inpatients treated for streptococcal disease atthe Clinic for Infectious Diseases (Dr “FranMihaljević”) in Zagreb, Republic <strong>of</strong> Croatia,has shown that patients with severe streptococcaltoxic and invasive infections in 45.5%<strong>of</strong> cases have isolated invasive M-1 and M-3type, with documented types <strong>of</strong> M-6, M-28also M-76 M-4, M-12 and M-60, but in asmaller percentage (23).In the Microbiological laboratory <strong>of</strong> theDepartment <strong>of</strong> Public Health <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Canton, was isolated by standard methodsand typed Streptococcus pyogenes, which6

Aida Koso et al.: Serotyping Streptococcus Pyogenes <strong>of</strong> Preschool and Primary School Childrenis governed by the microbiology laboratory<strong>of</strong> the National Reference Laboratoryin Prague, Czech Republic. Of the 72 typedstrains <strong>of</strong> streptococcus, in 70 or 97.2% <strong>of</strong>the samples type was confirmed by isolation<strong>of</strong> Streptococcus pyogenes, which indicatesthe high quality and validity <strong>of</strong> routine microbiologicaldiagnostics in bacteria that isperformed in the microbiological laboratory<strong>of</strong> the Department <strong>of</strong> Public Health <strong>of</strong>the Canton <strong>Sarajevo</strong>. Serotyping <strong>of</strong> streptococciin our country does not exist, and thesamples were serotyped in Prague, invasivetypes <strong>of</strong> M 1 and M 3 were isolated in 35.7%<strong>of</strong> samples. Considering the total number <strong>of</strong>M type sorts, 75.7% <strong>of</strong> samples were M-1,M-3, M-6, M-12. Other types which areisolated was M-28, M-4, M-5, M-27G, M-50.62, M-75, M-77, M-87 and M-89.Epidemiological data on streptococcalinfections in developing countries are <strong>of</strong>crucial importance, although it turned outthat they are very scarce. Consequently isdeveloped the Strep-EURO project, whichaims to improve our knowledge <strong>of</strong> streptococcusgroup A. In order to prevent streptococcaldisease it is necessary continuouslycollect information and knowledge aboutthe cause <strong>of</strong> the diseases that are its consequence.It is necessary to continually monitorthe presence <strong>of</strong> particular antigenic types(10.24).ConclusionStudies in the world have pointed out theimportance <strong>of</strong> isolation, identification andserotyping <strong>of</strong> streptococcus, the importance<strong>of</strong> identifying the occurrence <strong>of</strong> mucoustypes greater incidence <strong>of</strong> acute rheumaticfever and the importance <strong>of</strong> introducing anactive control over the movement <strong>of</strong> certainM-types <strong>of</strong> streptococci, as a risk factorin the possible development <strong>of</strong> rheumaticheart disease, or acute glomerulonephritis.In the future in our country it is necessary tocreate a program similar to the Strep-EUROprogram for identification and serotypingStreptococcus pyogenes in order to establisha permanent expert network <strong>of</strong> referenceand other relevant centers. Role <strong>of</strong> referencecenters would be to develop and applymodern methods in the field <strong>of</strong> molecularbiology, genetics, microbiology and otherbranches <strong>of</strong> medicine, with the aim <strong>of</strong> theresearch <strong>of</strong> streptococci and streptococcalinfections. The results should be evaluatedand coordinated with other European centersin order to take appropriate measures toprevent streptococcal infection.References:1. Kalenić S, Mlinarić–Missoni E. Medicinska bakteriologijai mikologija. Merkur A.B.D. Zagreb,2005; 142-160.2. Bisno AL, Brito MO, Collins CM. Molecular basis<strong>of</strong> group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet InfectDis 2003; 3(4): 191-2003. Kriz P, Mottova J. Analysis <strong>of</strong> active survellenceand passive notification <strong>of</strong> streptococcal diseasesin The Czech Republic. Adv Exp Med Biol 1997;418: 217-19.4. Veasy LG, Tany LY, Daly JA, Korgenski K, et all.Temporal association <strong>of</strong> the appearance <strong>of</strong> mucoidstrains <strong>of</strong> Streptococcus pyogenes with a continuinghigh incidence <strong>of</strong> rheumatic fever in Utah. PubMed Pediatrics 2004; 113(3 ): 168-72.5. Martin JM, Green M, Barbadora KA, Wald ER.Group A Streptococci among school-aged children:clinical characteristics and the carrier state.Pub Med Pediatrics 2004; 114(5): 1212-9.6. Stephenson KN. Acute and chronic pharyngitisacross lifespan. Pub Med Lippincots Prim CarePract 2000; 4 (5) : 471-89.7. Bisno AL, Brito MO, Collins CM. Molecular basis<strong>of</strong> group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet InfectDis 2003; 3(4): 191-200.8. Facklam R, Beall B, Efstratiou A, Fischetti V, et all.Emm typing and validation <strong>of</strong> provisional M typesfor group A streptococci. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5(2): 247-53.9. Stollerman GH. Rheumatic fever as we enter the21 century. Boston <strong>University</strong>. Archived Reports,20007

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:1-810. Lamagni TL, Efstratiou A, Vuopio-Varkila J, JasirA, Schalen C.Strep-EURO. The epidemiology <strong>of</strong>severe Streptococcus pyogenes associated diseasein Europe. Indexed in Medline as Euro Euroveill2005; 10(9): 179-84.11. Kapetanović O, Ohranović M. Zbirka sanitarnihpropisa. Bosanska riječ <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, 2005 : 40-59.12. Službeni list SRBiH 36/87 Pravilnik o načinu prijavljivanjazaraznih bolesti: 6113. Knjige evidencije zaraznih oboljenja u Kantonu<strong>Sarajevo</strong>, 2006.14. Milovanović J. Etiološka identifikacija akutnihtonsil<strong>of</strong>aringitisa kod dojenčadi i djece s posebnimosvrtom na terapiju streptokokih infekcija.Magistarski rad. Univerzitet u <strong>Sarajevu</strong>, <strong>Medicinski</strong>fakultet, <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, 1987.15. Dinarević S, Mulaosmanović V, Subašić D,Selimović A, i saradnici. Correlation <strong>of</strong> Streptococcusgroup A in throat culture and antistreptolysintitre in post-war Bosnian pediatric population.Paediatric clinic <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Microbiology InstituteCCS <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Bosnia and Herzegovina Acta PaediatricaEspanola vol 60; (8)(381-2) ; 2002.16. Bernard Beall. Streptococcus pyogenes emm sequencedatabase Centers for Disease Control andPrevention, Atalanta, 2008. http:/www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/protocol_emm-type.htm17. Colman G, Tanna A, Gaworzewska ET. Changesin the distribution <strong>of</strong> serotypes <strong>of</strong> Streptococcuspyogenes. Int J Med Microbiol 1992; 277-8(Supp22):14-6.18. Kaplan EL, Wotton JT, Johnson DR. Dynamic epidemiology<strong>of</strong> group A streptococcal serotypes associatedwith pharyngitis. Lancet 2001; 358(9290):1334-7.19. Siljander T, Toropainen M, Muotiala A, Hoe NP,et all. Emm- typing <strong>of</strong> invasive T28 group A streptococci,1995-2004. Finland. 15th European Congress<strong>of</strong> Clinical Microbiology and Infectious DiseasesClin Microbiol Infect 2005; 11(Suppl 2): 567.20. Benenson A. Priručnik za spriječavanje i suzbijanjezaraznih bolesti. Beograd, 1995; 459-66.21. Shulman ST, Stollerman GH, Beal B, Dale JB, etall. Temporal changes in streptococcal M proteintypes and the near-disappearance <strong>of</strong> acute rheumaticfever in the United States. Clin Infect Dis2006; 15: 42 (4): 441-7.22. Begovac J. Kliničko značenje serotipizacije streptokokau Zagrebu. <strong>Medicinski</strong> fakultet, Zagreb,1995. SVIBOR- Projekt broj: 3-01-29.23. Bejuk D. Učestalost tipova beta-hemolitičkihstreptokoka grupe A u bolesnika liječenih u kliniciza infektivne bolesti Dr Fran Mihaljević od 1990.-1996. godine. Doktorska disertacija, <strong>Medicinski</strong>fakultet Zagreb, 2002.24. Smith A, Lamagni TL, Oliver I, Efstratiou A, etall. Invasive groupA streptococcal disease: shouldclose contacts routinely receive antibiotic prophylaxis?Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5(8): 494-5008

Original PapersFrequency and sex distribution <strong>of</strong> omphalocele in surgicallytreated infants in <strong>Sarajevo</strong> region <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and HerzegovinaSelma Aličelebić 1 , Amela Vilić 21, 2Institute <strong>of</strong> Histology and Embryology,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> Medicine,Čekaluša 90, 71000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>,Bosnia and HerzegovinaCorresponding authorSelma AličelebićInstitute <strong>of</strong> Histology and Embryology<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>School <strong>of</strong> MedicineČekaluša 90, 71000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Bosnia and HerzegovinaE-mail: alicelebicselma@gmail.comOmphalocele is a prolapse (herniation) <strong>of</strong> abdominal organs,through an anterior abdominal wall defect at the base <strong>of</strong> theumbilical cord. Herniated abdominal organs (liver, small andlarge intestine, stomach, spleen, gallbladder) are covered withthe amnion and sometimes also with the peritoneum. Theaim <strong>of</strong> this research is to determine the frequency and sexdistribution <strong>of</strong> surgical cases <strong>of</strong> omphalocele treated at theClinic for Children’s Surgery; Clinical Center, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Sarajevo</strong>. It is a retrospective study that included 9 cases <strong>of</strong>surgically treated omphalocele, in the period <strong>of</strong> time from2000 until 2009. These data are obtained from the medicalprotocols and patient histories at the Clinic for the Children’sSurgery. Analysis <strong>of</strong> data found that in the period <strong>of</strong> timefrom 2000 - 2009 at the Clinic for Children’s Surgery, 9 patientswith omphalocele were treated surgically. From these9 patients, 6 <strong>of</strong> them were males (70%), and 3 females (30%).5 (55.55%) <strong>of</strong> these patients had associated anomalies, which<strong>of</strong> those the most frequent were chromosomal abnormalitiespresent at 3 patients (33.33%). Based on these data wecan conclude that omphalocele is a rare congenital anomalywhose frequency doesn’t vary a lot through the years.Key words: omphalocele, frequencyIntroductionDuring the 4 th to 5 th week <strong>of</strong> development,the flat embryonic disk folds in four directionsand/or planes: cephalic, caudal, andright and left lateral. Each fold converges atthe site <strong>of</strong> the umbilicus, thus obliteratingthe extra embryonic coela. The lateral foldsform the lateral portions <strong>of</strong> the abdominalwall and the cephalic and caudal folds makeup the epigastrium and hypogastrium (1,2). Rapid growth <strong>of</strong> the intestines and liveralso occurs at this time. During the 6 thweek <strong>of</strong> development (or eight weeks fromthe last menstrual period), the abdominalcavity temporarily becomes too small to9

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:9-12accommodate all <strong>of</strong> its contents, resultingin protrusion <strong>of</strong> the intestines into the residualextra embryonic coela at the base <strong>of</strong>the umbilical cord. This temporary herniationis called physiologic midgut herniation.Reduction <strong>of</strong> this hernia occurs by the 12 thpostmenstrual week; beyond the 12 th week amidgut herniation is no longer physiological(3). A simple midline omphalocele developsif the extra-embryonic gut fails to return tothe abdominal cavity and remains coveredby the two-layer amniotic-peritoneal layerinto which the umbilicus inserts (1,2,4). Incontrast to fetal bowel, the liver does nothave a physiological migration outside <strong>of</strong>the abdominal cavity during development.Therefore, the liver is never present in physiologicmidgut herniation. However, if thelateral folds fail to close, a large abdominalwall defect is created through which theabdominal cavity contents, including theliver, can be herniated (1,2). The result is aliver-containing omphalocele. The omphalocelemay be small, with only a portion<strong>of</strong> the intestine protruding outside the abdominalcavity, or large, with most <strong>of</strong> theabdominal organs (including intestine, liver,and spleen) present outside the abdominalcavity. A translucent membrane covers theprotruding organs. A “small” type omphalocele(involving protrusion <strong>of</strong> a small portion<strong>of</strong> the intestine only) occurs in one out <strong>of</strong>every 5.000 live births. A “large” type omphalocele(involving protrusion <strong>of</strong> the intestines,liver, and other organs) occurs inone out <strong>of</strong> every 10.000 live births. Isolatedomphalocele occurs in approximately 1 in5000 live births (5). Many babies born withan omphalocele also have other abnormalities.Associated malformation ranges from30 to 88% (6). Babies with omphalocele haveabnormalities <strong>of</strong> other organs or body parts,most commonly the central nervous system,digestive system, heart, urinary system, andlimbs. More boys than girls are affected withomphalocele. The aim <strong>of</strong> this study was toobtain the frequency and sex distribution <strong>of</strong>the omphalocele among cases hospitalizedat the Clinic for Children’s Surgery; ClinicalCenter, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Bosnia andHerzegovina, during the period from January2000 to December 2009.Patients and methodsRetrospective study was carried out on thebasis <strong>of</strong> the clinical records in the Clinic forChildren’s Surgery; Clinical Center, <strong>University</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Bosnia and Herzegovina.From 1 st January 2000 to 31 st December2009, a total <strong>of</strong> 7529 patients were hospitalizedand out <strong>of</strong> that number nine cases(0.119%) were diagnosed as some type <strong>of</strong>omphalocele malformation. Standard methods<strong>of</strong> descriptive statistics were performedfor the data analysis.ResultsA total <strong>of</strong> 9 cases were treated in the Clinicfor Children’s Surgery; Clinical Center, <strong>University</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> in the period from 2000to 2009. The number <strong>of</strong> omphalocele casesdoes not vary much in the observed period(Table 1).Table 1. Frequency <strong>of</strong> omphalocele in theobserved periodYear N°2000 02001 12002 12003 22004 02005 12006 02007 02008 22009 2∑ = 910

Selma Aličelebić et al.: Frequency and sex distribution <strong>of</strong> omphalocele in surgically treated infants...At the Clinic for Children’s Surgery;Clinical Center, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> surgicallywere treated cases <strong>of</strong> omphalocelefrom the whole Federation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia andHerzegovina and their geographical distributionis shown in Table 2.Table 2. Frequency <strong>of</strong> omphalocele in theobserved geographical regionCanton N°<strong>Sarajevo</strong> 3Una-Sana 2Zenica-Doboj 2Central Bosnia 1Herzegovina-Neretva 1∑ = 9The structure <strong>of</strong> patients with omphaloceletreated according to the gender is shownin Table 3. Out <strong>of</strong> that num ber 6 (66.66%)were male patients, while 3 (33.33%) werefemale; sex ratio 2:1.Table 3. Total number and gender <strong>of</strong> treatedomphaloceleGENDER N° %MALE 6 66.66 %FEMALE 3 33.33%TOTAL 9 100%Among surgically treated patients wereeight cases <strong>of</strong> “small” type and one case <strong>of</strong>“large” type omphalocele.Isolated omphalocele occurs in four cases,multiple malformations were found infive cases, three cases were with one and twocases were with two associated malformations(Figure 1). Chromosome aberrationswere present in three patients, one patienthad gastrointestinal and one had musculoskeletalmalformation.DiscussionIn the period from 1 st January 2000 to 31 stDecember 2009 a total <strong>of</strong> 7529 patientswere hospitalized. Out <strong>of</strong> that number 9were omphalocele cases (0.119%) and out<strong>of</strong> that num ber 6 (66.66%) were male patients,while 3 (33.33%) were female; sexratio 2:1. Small omphalocele was presentin 8 (88.88%) <strong>of</strong> 9 surgically treated cases,while the large omphalocele was present inonly one patient (11.11%). Anomalies associatedwith omphalocele were present in55.55% patients and the most common werechromosome aberrations (33.33%). Ourdata was consistent with the other studiesthat have shown similar results. It was reportedthat the prevalence <strong>of</strong> omphalocelewas 1:3400 in the period 1994-2002 and1:2709 from 2000 to 2002 in the UnitedStates, sex ratio was 1.7: 1 and 76 % patientsFigure 1 – Frequency <strong>of</strong> omphalocele with associated anomalies11

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:9-12had associated anomalies (7). Prevalence <strong>of</strong>omphalocele was 4.08:10,000 newborns inEngland, Wales and Scotland (8). Between1993-2002 there were 100 cases <strong>of</strong> omphalocele(82.6%) in Singapore, with an incidence<strong>of</strong> 2.63: 10,000 live births and 40%<strong>of</strong> omphalocele cases were accompanied byassociated anomalies (9). It was reportedthat the omphalocele incidence in Norwaywas 5.4:10,000 and 5.1:10,000 in Russia.The data covered the period 1995-2004 inArkhangelskaja Oblast (AO) in Russia and1999-2003 in Norway which were obtainedfrom the malformation register in AO andthe Medical Birth Registry <strong>of</strong> Norway (10).However, based on our data we can concludethat omphalocele is a rare congenitalanomaly whose frequency doesn’t vary a lotthrough the years. In conclusion, our studyis not consistent with world-wide trends inshowing the increasing incidence <strong>of</strong> anteriorabdominal wall defects. However, our studysuggests that omphalocele is not on the risingtrend and that more studies should bedone to elucidate this phenomenon.References:1. Duhamel, B., Embryology <strong>of</strong> exomphalos and alliedmalformations. Arch Dis Child 1963; 38:142.2. Hutchin, P. Somatic anomalies <strong>of</strong> the umbilicusand anterior abdominal wall. Surg Gynecol Obstet1965; 120:1075.3. Cyr, DR, Mack, LA, Schoenecker, SA, Patten, RM.Bowel migration in the normal fetus: US detection.Radiology 1986; 161:119.4. Margulis, L. Omphalocele (amnicele). Am J ObstetGynecol 1945; 49:695.5. Townsend. Abdomen: In Sabiston Textbook <strong>of</strong>Surgery (16th ed.) Philadelphia. WB SaundersCo. 2001. p. 1478.6. Gilbert WM, Nicolaides KH. Fetal omphalocele:associated malformations and chromosomal defects.Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Oct;70(4):633-5.7. Goldkrand JW, Causey TN, Hull EE. The changingface <strong>of</strong> gastroschisis and omphalocele in southeastGeorgia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004May;15(5):331-5.8. Tan KH, Kilby MD, Whittle MJ, et al. Congenitalanterior abdominal wall defects in England andWales 1987-93: retrospective analysis <strong>of</strong> OPCSdata. BMJ 1996; 313: 903-6.9. Tan KBL, Tan KH, Chew SK, Yeo GSH Gastroschisisand omphalocele in Singapore: a tenyearseries from 1993 to 2002. Singapore Med J2008;49(1) :31.10. Petrova JG, Vaktskjold A. The incidence and maternalage distribution <strong>of</strong> abdominal wall defectsin Norway and Arkhangelskaja Oblast in Russia.Int J Circumpolar Health. 2009 Feb;68(1):75-83.12

Original PapersAcute Toxicity Study <strong>of</strong> Combination <strong>of</strong> Tridecactide andMet-EnkephalinMaida Rakanovic-Todic 1 , Nedzad Mulabegovic 1 , Fahir Becic 1 , Mirjana Mijanovic 1 ,Svjetlana Loga-Zec 1 , Jasna Kusturica 1 , Lejla Burnazovic-Ristic 1 , Aida Kulo 1 , ElvedinaKapic 11Institute <strong>of</strong> Pharmacology, ClinicalPharmacology and Toxicology,Medical Faculty <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Corresponding author:Maida Rakanovic-TodicInstitute <strong>of</strong> Pharmacology,Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology,Medical Faculty,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Čekaluša 90, 71 000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Phone/fax: +387 33 227 018E-mail: maida@dic.unsa.baIntroductionIntroduction: Acute toxicity study was done as the entry step<strong>of</strong> prospective drug toxicological evaluation. The fixed combination<strong>of</strong> two peptide components: met-enkephalin and tridecactideis newly registered drug in Bosnia and Herzegovina(Enkorten ® , Farmacija d.o.o. Tuzla). Materials and methods:Acute toxicity testing was performed on Wistar albino rats,as the single dose testing in accordance with the Limit Testmethodology. Both peptides cannot be absorbed after theoral application and the combination was individually appliedto male and female rats by intravenous (IV), subcutaneous(SC) and intraperitoneal (IP) route. For each route <strong>of</strong>application three dose ranges were calculated, as multiplications<strong>of</strong> expected human therapeutic dose (met-enkephalin5-10 mg and tridecactide 1-2 mg). The administered multiplicationswere: IV 50, 100 and 200 times; SC 100, 250 and500 times; and IP 100, 250, 500 times plus 1000 times in additionalgroup <strong>of</strong> males. Results and conclusions: Neither lethalitynor significant macroscopic and microscopic changesat necropsy following planned sacrificing were observed.The main clinical signs observed at administered doses wereslight changes in motor activity and intensive phonation inIV treated groups. No statistically significant differences inpostmortem organ weights were noted. The tested combinationinduced no lethality and demonstrated low level <strong>of</strong> toxicityin rationally high doses.Key words: tridecactide, met-enkephalin, 1-13-corticotropine,alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, acute toxicityThe newly registered drug in Bosnia andHerzegovina, Enkorten ® (Farmacija d.o.o.Tuzla), consists <strong>of</strong> two neuropetides: metenkephalinand tridecactide (a 1-13-corticotropine).Tridecactide was previously nameda-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-like(a-MSH-like). Tridecactide is deamidatedand deacetylated a-MSH. In the model <strong>of</strong>ethanol induced gastric lesions in rats, metenkephalinand a-MSH exhibited statisticallysignificant additive cyto-protective effect(1,2), achieving the best effect in 5:1 doses13

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:13-21proportion. The practical consequence <strong>of</strong>the latter observation was estimation <strong>of</strong> theexpected human dose (for entering the clinicaltrials) on 5-10 mg <strong>of</strong> met-enkephalin and1-2 mg <strong>of</strong> tridecactide, administered (intramuscularlyor subcutaneously) five times aweek and gradually reduced to once a week(2). Both peptides cannot be absorbed followingoral application.Alpha-MSH exerts antipyretic, antiinflammatoryand antimicrobial effects(3,4,5,6,7). Alpha-MSH is being produced inthe human pituitary and by extra-pituitarycells including gastrointestinal cells, monocytesand keratynocytes. Research suggeststhat a-MSH anti-inflammatory effect couldbe mediated by melanocortin receptorsand regulatory circuits in macrophages,and through descending anti-inflammatorypathways originating from the neurons(8,9). Combined use with met-enkephalinencourages the presence <strong>of</strong> both amino-acidsequences in the same precursor molecule,proopiomelanocortin. Processing yields a-MSH and b-endorphin, while met-enkephalinis mainly derived from preproenkephalin(10). Met-enkephalin is one <strong>of</strong> the simplestopioid peptides, with prominent role in investigation<strong>of</strong> enkephalins engagement inimmunity. Opioid receptors are detectedon the human leucocytes, lymphocytes andthrombocytes. Also, evidence suggests lymphocytesproduction <strong>of</strong> enkephalins andendorphins (11). Growth factors role wassuggested for opioid peptides (12,13), implicatingcontrol <strong>of</strong> cell differentiation andproliferation.Investigational pharmaceuticals toxicitytesting aims on evaluation <strong>of</strong> the toxicologicalpotential and risks <strong>of</strong> the human exposure.Acute toxicity provides the importantsafety parameters for the prospective humanoverdose scenario and its expectedclinical presentation (14,15). Traditionally,international authorities and governmentalagencies had adopted the mean lethal doseas the sole measurement <strong>of</strong> acute toxicity.Currently, the significance is given to theinformation on toxicity signs, mechanism <strong>of</strong>toxicological action and dose-response relationshipfor non-lethal parameters, whilelethality should not be intended endpoint inacute toxicity studies (14,15). Use <strong>of</strong> the rationallyhigh doses in acute toxicity testingis considered as acceptable, and complieswith the Limit Test concept. The use <strong>of</strong> dosesup to the maximum tolerated dose, a doseachieving large exposure multiplies or maximumfeasible dose, are considered appropriatefor the general toxicity testing. The doses<strong>of</strong> 1000 mg/kg/day are considered appropriatefor acute toxicity testing, excluding thesituations when the mean exposure margin<strong>of</strong> 10-fold is not covered. Also, assessmentfollowing the intravenous (IV) route <strong>of</strong> applicationmaximizes the exposure to the testsubstance.Our study aims on detecting toxicitypotential <strong>of</strong> the met-enkephalin and tridecactidecombination following three differentways <strong>of</strong> application, identifying targetorgans for toxicity, reversibility <strong>of</strong> toxic effectsand symptoms <strong>of</strong> acute intoxication. Apreclinical safety evaluation, with an acutetoxicity testing as a first step, would enablethe prospective drug entering the clinicalevaluation.Materials and methodsExperimental AnimalsAdult, healthy, Wistar albino rats, <strong>of</strong> bothsexes, were randomized in three treatmentand one control group for IV application(3M + 3F), subcutaneous (SC) application(5M + 5F), and intraperitoneal (IP) dosing(treatment groups 5M + 5F and control 3M+ 3F). The additional group <strong>of</strong> males (4M)was IP dosed with highest dose. Averagebody mass at randomization was 401.75 g,14

Maida Rakanovic-Todic et al.: Acute Toxicity Study <strong>of</strong> Combination <strong>of</strong> Tridecactide and Met-Enkephalinfor males, and 264.42 g, for females. Animalsspent minimally 21 day in quarantine beforerandomization. Standardized care, nutritionand water supply were provided during thestudy. This research was conducted followingthe Guide for the Care and Use <strong>of</strong> LaboratoryAnimals, US National Institutes <strong>of</strong>Health.CompoundsThe test samples <strong>of</strong> a) met-enkephalin andb) tridecactide were manufactured by CommonwealthBiotechnologies, USA, and deliveredas lyophilized powder in closed flacons.Compounds were dissolved in physiologicalsaline (0.9% NaCl) upon the application,and applied as combination in fixedproportion <strong>of</strong> individual substances.Experimental design and ConductAcute toxicity testing by IV, SC and IP applicationwas performed as the single dosetesting in accordance with the Limit Testmethodology. The animals were randomlyassigned to cages and the individual animalwas fur marked with picric acid. The animalswere dosed with the test combination individuallyand dose was adjusted towards theanimal’s body mass. Dose ranges were calculatedas the multiplication <strong>of</strong> expected humantherapeutic dose (a+b as met-enkephalin+ tridecactide). Control animals receivedthe solvent only (physiological saline).Following multiplications were providedfor IV dosing:– 50 times: 3.55 mg/kg + 0.7 mg/kg(group code IV1, sex subgroups IVF1,IVM1)– 100 times: 7.1 mg/kg + 1.4 mg/kg(group code IV2, sex subgroups IVF2,IVM2)– 200 times: 14.2 mg/kg + 2.8 mg/kg(group code IV3, sex subgroups IVF3,IVM3)– Controls (group code IVC, sex subgroupsIVFC, IVMC)Following multiplications were providedfor SC dosing:– 100 times: 7.1 mg/kg + 1.4 mg/kg(group code SC1, sex subgroupsSCF1, SCM1)– 250 times: 17.7 mg/kg + 3.5 mg/kg (group code SC2, sex subgroupsSCF2, SCM2)– 500 times: 35.5 mg/kg + 7.1 mg/kg (group code SC3, sex subgroupsSCF3, SCM3)– Controls (group code SCC, sex subgroupsSCFC, SCMC)Following multiplications were providedfor IP dosing:– 100 times: 7.1 mg/kg + 1.4 mg/kg(group code IP1, sex subgroups IPF1,IPM1)– 250 times: 17.7 mg/kg + 3.5 mg/kg(group code IP2, sex subgroups IPF2,IPM2)– 500 times: 35.5 mg/kg + 7.1 mg/kg(group code IP3, sex subgroups IPF3,IPM3)– 1000 times: 71.0 mg/kg a + 14.3 mg/kg (additional group code IP4)– Controls (group code IPC, sex subgroupsIPFC, IPMC).Doses were applied in constant volume<strong>of</strong> 0.001 ml/g IV, 0.0005 ml/g SC, and 0.005ml/g IP (excluding additional group).Observation period was set to 14-days.Clinical observations were set on 90, 150and 210 minutes and 4 hours after dosingduring the first day and thereafter on thedaily basis. Animal weight, food and waterconsumption were recorded before dosingand thereafter on the weekly basis. Intensity<strong>of</strong> phonation was assessed subjectively duringmanipulation and handling <strong>of</strong> animals,after the IV and SC application. Plannedsacrificing and necropsy were set at the end<strong>of</strong> the study. Following the macroscopic examination,the organ weights were recorded(as percentage <strong>of</strong> animal’s body weight). The15

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:13-21samples <strong>of</strong> liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, brainand organs with noted macroscopic changeswere examined histopathologicaly.Statistical analysis was performed withmodification for small samples by Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunnett test with multiplecomparisons <strong>of</strong> distributions.ResultsNo lethality was observed during or after IV,SC and IP application. Animal body massincreased during the study in all treatmentand control groups, compared to the bodymass before the application (Figure 1). Thestagnation and decrease in body mass wasnoted only for females following SC application(Table 1). Statistically significant differencein body mass was noted for IVM1(p=0.037812), compared to control group.Statistical analysis <strong>of</strong> water and food consumptiondata (Table 2) showed no statisticallysignificant difference, except for IVM1(p = 0.037812; p = 0.032902).The most prominent clinical signs werenoted on the day 1 <strong>of</strong> the observation periodfollowing all three application routes. Slightlyreduced motor activity was observedin all animals treated with the highest IVdose, males treated with the medium dose,and males and one female treated with thelowest dose. On the contrary, females treatedwith the medium and the lowest doseseemed more active. There was a slight ptosis(eyelids down ¼) in two males treatedwith the highest dose, two males and onefemale treated with medium dose, and allmales and one female treated with the lowestdose. Horizontally positioned tail wasnoted in all animals treated with the highestdose, two males and one female treated withmedium dose, one male and two femalestreated with the lowest dose. Slight cyanosisand general vasoconstriction was noted inone male treated with the highest and onemale treated with medium dose.Following the SC application (day 1)slightly slower motor activity <strong>of</strong> all treatedand control animals was observed. Also,slight muscular hypotonia was noted on day3 in three males treated with highest doseand one male treated with the lowest dose.Following the IP application (day 1), irregularbreathing, decrease in motor activity,somnolence, ataxia, catalepsy and muscularhypotonia were observed in all malesfrom group IP4. A proportion <strong>of</strong> the effectsnoted in IP4 group could be attributed toTable 1. Median <strong>of</strong> growth <strong>of</strong> animal body mass during the study periodGroup Median Group Median Group MedianIVMC 6.96 SCMC 3.47 IPMC 4.25IVM1 1.19 SCM1 3.08 IPM1 2.86IVM2 3.47 SCM2 3.11 IPM2 0IVM3 5.13 SCM3 3.70 IPM3 2.67IPM4 2.40IVFC 2.89 SCFC 0.44 IPFC 3.21IVF1 4.81 SCF1 -0.65 IPF1 2.00IVF2 4.17 SCF2 0 IPF2 5.16IVF3 4.00 SCF3 -1.24 IPF3 1.6116

Maida Rakanovic-Todic et al.: Acute Toxicity Study <strong>of</strong> Combination <strong>of</strong> Tridecactide and Met-EnkephalinFigure 1. Body mass ratio before application and upon the sacrificationTable 2. Median weekly water and food consumption <strong>of</strong> the animals during the study periodGroup X maxX minMedian Group X maxX minMedian Group X maxX minMedianWater consumptionIVMC 16.78 14.15 15.10 SCMC 12.25 7.09 8.43 IPMC 12.68 11.03 12.21IVM1 11.66 9.56 10.62 SCM1 13.97 10.07 11.87 IPM1 13.84 9.21 11.72IVM2 13.89 11.23 13.42 SCM2 15.18 8.98 12.80 IPM2 14.63 12.85 14.58IVM3 12.82 10.70 12.46 SCM3 15.50 9.66 11.43 IPM3 13.40 11.73 13.08IPM4 11.37 9.60 10.11IVFC 16.57 15.09 16.09 SCFC 12.92 9.35 10.98 IPFC 20.05 16.61 18.35IVF1 16.85 15.34 15.73 SCF1 19.81 8.92 16.39 IPF1 21.80 14.70 18.62IVF2 16.63 13.53 14.34 SCF2 14.06 12.19 13.57 IPF2 15.58 14.48 14.71IVF3 13.22 11.90 12.27 SCF3 15.00 9.02 11.45 IPF3 15.38 13.82 14.68Food consumptionIVMC 7.28 6.10 6.13 SCMC 6.46 4.43 6.02 IPMC 7.08 5.73 6.62IVM1 5.13 4.71 4.74 SCM1 6.93 5.96 6.92 IPM1 8.29 7.16 7.50IVM2 5.82 5.25 5.79 SCM2 6.24 5.63 5.81 IPM2 6.80 6.18 6.34IVM3 6.49 5.76 5.88 SCM3 6.39 5.34 6.38 IPM3 7.94 6.57 6.70IPM4 6.25 5.90 6.03IVFC 7.05 5.99 6.79 SCFC 7.06 5.78 6.54 IPFC 7.38 5.70 6.89IVF1 6.25 5.91 6.03 SCF1 6.43 5.89 6.22 IPF1 6.02 5.58 5.88IVF2 6.90 6.13 6.59 SCF2 8.32 6.78 6.86 IPF2 6.02 5.52 5.76IVF3 6.98 5.32 6.26 SCF3 7.34 5.48 7.28 IPF3 6.22 5.24 5.5917

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:13-21IP application <strong>of</strong> the large amount <strong>of</strong> fluid,since the constant volume was not respectedfor this group. Somnolence and muscularhypotonia was noted in male from groupIPM3, and only somnolence in male fromgroup IPM1. Afterwards, frequency andcharacter <strong>of</strong> breathing were observed onceweekly and remained in physiological limits.The intensive phonation during the manipulationwith animals was registered forIV dosed groups between 9 and 14 day <strong>of</strong>observation period (Figure 2), and wasn’tnoted in control animals. Statistically significantdifference was detected for increasedphonation in all treatment groups <strong>of</strong> males,IVF3 and IVF2, compared to controls (p£0.000001). Following the SC applicationeach phonation during the manipulationwith animals was noted (Figure 3). Thereis no prominent difference in variation inphonation in males. Statistically significantdifference in phonation was noted for groupSCF3 (P=0.000001), compared to the control.Necropsy and histopathology did not revealsignificant changes in organs and tissuesmacroscopic and microscopic structure.Following the SC application, macroscopicchanges were detected in one control maleand one female in group SCF2 (hyperemiaand dilatation <strong>of</strong> tubas uterine). The macroscopicchanges were supposed not to berelated with application <strong>of</strong> the test combination.Also, no abnormal changes were notedin postmortem organ mass with respect tobody mass, in experimental groups in comparisonwith controls (Table 3).DiscussionThe purpose <strong>of</strong> this study was to gain theinsight in the acute toxicity pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> thetested combination. Applied combinationinduced no lethality and demonstrated lowlevel <strong>of</strong> toxicity in rationally high doses.The use <strong>of</strong> doses achieving large exposuremultiplies is considered appropriate for thegeneral toxicity testing, indicating that testing<strong>of</strong> higher doses just to induce lethality innot necessary according to the current regulatorydemands. Also, available data showsthat met-enkephalin (in doses up to 10 mg/kg) and a-MSH (in dose range 1-3.3 g/kg)were applied without lethality in animal experiments(1,2). However, no evaluation hasbeen made so far regarding acute toxicity <strong>of</strong>tridecactide individually nor in combinationwith met-enkephalin.Increase in animals body mass confirmedlow toxic potential. Similar foodconsumption <strong>of</strong> animals in control and experimentalgroups, as the true indicator <strong>of</strong>animal growth rate, indicates the feed intakeand utilization was not affected. Also, detectingneither organ or tissue damage nororgan mass ratio differences in control andexperimental groups, indicate that application<strong>of</strong> the tested combination to the rats didnot result in permanent adverse toxicologicaleffect on examined organs. Reversiblesigns <strong>of</strong> toxicity disappear with substanceelimination and usually are not followed bypermanent tissue damage.Met-enkephalins high doses produceeffects on OP3 (m) receptors with sedation,mood changes, miosis, respiratory depressionand gastrointestinal disturbances(10,11). Registration <strong>of</strong> ptosis, motor activitychanges, horizontally positioned tail orincreased phonation could suggest opioidpathway engagement. Increased intensity <strong>of</strong>phonation was clearly noted for all IV dosedtreatment groups, while not noted in controlanimals. Following SC application, all phonationswere registered and effect was not sowell defined. Nevertheless, effects involvinganimal’s emotional reaction are very unstablefield for interpretation, while sensitivity<strong>of</strong> animal tests is generally high and specificityis low.The toxicological studies aim to revealthe type <strong>of</strong> toxicological action, what18

Original PapersBrucellosis – Emerging Zoonosis in Bosnia and HerzegovinaSajma Dautović-Krkić¹, Edina Bešlagić², Meliha Hadžović-Čengić¹, SnježanaMehanić¹, Adnan Karavelić¹, Sead Ahmetagić³, Ibrahimpašić Nevzeta 4 , EldiraHadžić 5 , Ivo Curić 6 , Nazif Derviškadić 6 , Janja Bojanić 7¹ Clinic for Infectious Diseases,Clinical Center <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>, <strong>Sarajevo</strong>² Institut for Microbiology Medical Faculty<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>³ Clinic for Infectious Diseases,<strong>University</strong> Clinical Center Tuzla4Department for Infectious Diseases,Cantonal Hospital Bihać5Department for Infectious Diseases,Cantonal Hospital Zenica6Department for Infectious Diseases,Clinical Hospital Mostar6Department for Infectious Diseases,Hospital Južni logor, Mostar7Institut for Epidemiology, Banja LukaCorresponding author:Clinic for infectious diseases,Clinical Center <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>, <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Bolnička 25, 71000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Bosnia and HerzegovinaE-mail: sajmadautovic@gmail.comBrucellosis is a zoonotic disease present across the world.Disease in humans has an acute, sub acute or chronic course,whereas in animals, usually, occurs as asymptomatic chronicinfection. In Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H), brucellosis isimported by livestock donated to refugees and displaced personsafter aggression on Bosnia and Herzegovina and the warfrom 1992–1995 and since then has spread throughout thecountry in both Entities.AIM <strong>of</strong> this study was to make comparable analysis <strong>of</strong> researchresults on brucellosis data in the period 2000/2005,with the results reported for the period 2006/2009 and toencourage pr<strong>of</strong>essionals <strong>of</strong> veterinary and human medicineto take active action and cooperation with government structuresin order to found an optimal solution to control anderadicate this anthropozoonosis.Results <strong>of</strong> research showed that during the 2006/2009 (44months) was hospitalized six times more cases than in theprevious period 2000/2005 (72 months), the increasing number<strong>of</strong> sick children, as well as recurrence, regardless <strong>of</strong> thetherapy. Mode <strong>of</strong> expansion and maintenance <strong>of</strong> the diseasein some regions in the last ten years indicates its endemicity.The authors CONCLUDE that brucellosis in B&H is emergentzoonotic disease that has become endemic, based onnature <strong>of</strong> continuing epidemic outbreaks in some areas, andthat the work <strong>of</strong> state institutions was not nearly enough tocombat the disease and place it under control. Likewise, therewas no and there is no planned and programmed and supportedcooperation with experts from human and veterinarymedicine.Key words: brucellosis, epidemic, endemia, emergent zoonosis22

Dautović-Krkić S. et al.: Brucellosis - Emerging Zoonosis in Bosnia and HerzegovinaIntroductionBrucellosis is the most widespread zoonosis,that affects more than a half million peopleper year, all over the world. Causative agentis Brucella species, domestic and wild animalsare reservoirs, and it affects mostly humans(1).In humans, Brucella causes acute, subacute or chronic disease. In a first 3-6 weeks,brucellosis is manifested with general flulikesymptoms, and thereafter is localized incertain organs, most commonly the jointsand intervertebral discus, then the liver,lungs, testicles, less on the heart valves, andother organs (2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9). Often, thedisease manifests in humans, only whenbecame chronic and has consequences oncertain organs. In older patients the diseasecan be mistaken for rheumatoid or reactivearthritis <strong>of</strong> other etiology, thus creating diagnosticdifficulties, delayed early therapyand leaves the possibility <strong>of</strong> disability (5).The disease is widespread in livestockregions <strong>of</strong> the world and in most countries<strong>of</strong> the Mediterranean region is endemic. InBosnia and Herzegovina disease appearedafter the war 1992-1995 and since then hasbeen steadily spreading among animals andhumans, with no signs <strong>of</strong> reduction in thenumber <strong>of</strong> infected and affected. Brucellosiswas imported from neighboring countries,with donated livestock to refugees and displacedpersons, since, due to political reasons,there was not adequately controled <strong>of</strong>import <strong>of</strong> livestock on the borders.Objectives– To make a comparative analysis <strong>of</strong>hospitalized patients with brucellosisin Bosnia and Herzegovina in twoconsecutive periods: 2000–2005 and2006–2009.– To make conclusions and guidelinesfor suppression and surveillance <strong>of</strong>brucellosis– To encourage better cooperationamong clinicians, veterinarians andauthorities in order to engage allavailable potentials in suppressionand surveillance <strong>of</strong> brucellosisFigure 1. Distribution <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1999–2009.23

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:22-27Material and methodsWe performed a retrospective study <strong>of</strong> brucellosisfiles from three clinics and four departmentsfor infectious diseases from bothBosnian entities (Federation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia andHerzegovina and Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska). Diagnosiswas confirmed either by ELISA andRose-Bengal test or by isolation <strong>of</strong> Brucellaspecies in blood. We used following statisticaltests: Student T-test and Chi-square test.ResultsBrucellosis was imported in Bosnia andHerzegovina after the war 1992–1995 withimported sheep and cattle that were donatedto refugees and returnees. First cases wereconfirmed in Veterinarian institute “VasoButozan” in Banja Luka (Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska)in 1999. Tested sera had been taken from returneesliving in Trebinje region. There werethree Brucella-positive sera, but only onewas <strong>of</strong>ficially reported. In period 2000–2005human brucellosis was spreading acrossFederation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovina andslowly becoming a continuous epidemic.Spreading <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis was closelyconnected to spreading among the animalson a certain territory.Figure 2. Brucellosis in Republic Bosnia andHerzegovina 1946–1999.DiscussionThere were only four isolated cases <strong>of</strong> brucellosisreported in period 1946–1992 inBosnia and Herzegovina. All four <strong>of</strong> themwere reported in military camps (Manjača,Konjic, Han Pijesak, and Bihać). Infectedsheep were euthanized, with all precautionsand epidemiological measures undertaken.Number <strong>of</strong> infected people was limited, referringto those who were in contact with infectedanimals on daily basis; cattle-breedersTable 1. Distribution <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis by the place <strong>of</strong> hospitalization, 1999–2005.FB&H* RS** B&H***Year <strong>Sarajevo</strong> Tuzla Mostar Zenica Bihać1999. 0 0 0 0 0 1 12000. 8 0 8 0 0 0 162001. 3 0 1 0 0 3 72002. 4 0 3 7 0 0 142003. 28 0 5 14 0 1 482004. 47 0 10 31 1 0 892005. 65 0 6 64 0 0 135Total 155 0 33 116 1 5 310*Federation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovina, **Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska, ***Bosnia and Herzegovina24

Dautović-Krkić S. et al.: Brucellosis - Emerging Zoonosis in Bosnia and HerzegovinaFigure 3. Brucellosis in Bosnia andHerzegovina 1999–2009and soldiers (10). Brucellosis emerged againin 2000 after the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina(1992–1995). It emerges simultaneouslyin three cantons <strong>of</strong> Federation <strong>of</strong>Bosnia and Herzegovina: <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, CentralBosnia, Herzegovina-Neretva. In CantonZenica-Doboj first case <strong>of</strong> brucellosis wasreported in 2002, and in Canton Una-Sanain 2004 (11, 12). There were 305 cases<strong>of</strong> human brucellosis reported in Federation<strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovina at the end<strong>of</strong> 2005. Mean age <strong>of</strong> patients was 40 years(0.8-85). Men were four times more affectedthen women. The most vulnerable populationwere cattle-breeders, then pupils andhousewives. Osteoarticular form <strong>of</strong> brucellosiswas dominant clinical form. There wasone death case due to Brucella endocarditis.In the same period (1999-2005) therewere only five reported cases <strong>of</strong> human brucellosisin Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska. All reportedcases were among returnees to their pre-warhomes. Infection was transmitted from infectedcattle that were donated through differentaid-programs. There was no significantspread <strong>of</strong> the diseases among the cattle,since there was not much contact betweenreturnee’s and local people’s cattle.During the following four years (2006–2009) human brucellosis was rapidly spreadingamong people in all areas <strong>of</strong> Bosnia andHerzegovina. There were six times morereported cases <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis (1797)than it was in former period (1999–2005)in Federation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovina.During this period the disease spread allacross Bosnia and Herzegovina. There were323 cases reported in Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska,with 216 <strong>of</strong> them reported in 2008. Meanage <strong>of</strong> the patients was 36 years (1.5–82years). Men were 2–4 times more affectedthen women. Concerning fact was increasednumber <strong>of</strong> infected children (one tenth <strong>of</strong>reported cases), as well as increased number<strong>of</strong> relapsing diseases regardless <strong>of</strong> therapy.There was a possibility that one part <strong>of</strong> therelapses is a reinfection, since people hasn’tbeen educated <strong>of</strong> self protection.Table 2. Distribution <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis by the place <strong>of</strong> hospitalization, 2006–2009.FB&H* RS** B&H***Year <strong>Sarajevo</strong> Tuzla Mostar Zenica Bihać2006. 64 0 4 84 6 4 1622007. 119 0 22 124 207 24 4962008. 133 113 49 319 139 216 9692009. 87 44 12 136 105 79 493Total 403 157 87 663 457 323 2120*Federation <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovina, **Republic <strong>of</strong> Srpska, ***Bosnia and Herzegovina25

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:22-27Analysis <strong>of</strong> disease spreading shows thatbrucellosis has become and endemic diseasefor the last ten years (12,13,14,15). From thefirst reported case it has had characteristics<strong>of</strong> continuing epidemic in Canton <strong>Sarajevo</strong>,Canton Herzegovina-Neretva and CantonCentral Bosnia. In Canton Tuzla, and CantonUna-Sana disease emerged in form <strong>of</strong>epidemic in 2007 and 2008 respectively, withmore than a hundred <strong>of</strong> infected individuals.All this leads to conclusion that thereis extremely high proportion <strong>of</strong> infectedcattle that were managed by poorly educatedcattle-breeders, which anticipate diseasespreading among people and animals. Noserious preventive precautions have beenundertaken in the past time in order to stopmixing <strong>of</strong> infected and uninfected cattle.Due to after-war division <strong>of</strong> Bosnia andHerzegovina, and lack <strong>of</strong> political will forthe past ten years, the disease has not beeneradicated or controlled, even though Bosniaand Herzegovina has State VeterinaryInstitute. Only palliative measures havebeen undertaken. Cattle have been testedfor brucellosis in both Bosnian Entities, butonly 10-30% <strong>of</strong> total population.There was not a single cattle cemetery inBosnia and Herzegovina before 2008, andeuthanized cattle ended at garbage dumps,in rivers or improperly buried. Two mobilecrematories started to operate at the end <strong>of</strong>2007. Bosnia and Herzegovina still properbutcheries. Veterinary Institute started cattlevaccination program at the end <strong>of</strong> 2008 inboth Bosnian Entities. Vaccination is obligatoryfor all cattle (young, old, pregnant, etc).Major concern is that there is no continuousand systemic cooperation between animaland human medicine specialists. Cooperationis based on personal contacts, and it’snot supported in any way.Conclusions– Human and animal brucellosis inBosnia and Herzegovina was reportedonly as a sporadic and isolateddisease, with no spreading before thewar 1992-1995.– After the war, brucellosis was confirmedfor the first time in 1999.– After emerging, brucellosis keptspreading, gathering characteristics<strong>of</strong> continuous epidemic.– From 2006 the disease emerged incertain areas in form <strong>of</strong> high scaleepidemic.– Brucellosis in Bosnia and Herzegovinahas been emerging zoonosis since1999/2000.– For the past ten years, brucellosis hasbecome an endemic disease in Bosniaand Herzegovina.– Government <strong>of</strong> Bosnia and Herzegovinahasn’t started sufficient andproper actions over the past ten yearsto eradicate or control the disease because<strong>of</strong> lack <strong>of</strong> political will.– There wasn’t any systematic cooperationbetween human and animalmedicine specialists.– Government and related institutionsmust take full responsibility for endangering<strong>of</strong> human and animalhealth on national level.– A cohort <strong>of</strong> experts and scientistsmust be formed in order to start seriousand systematic work, and createnational programs for eradicatingbrucellosis, as well as other infectiousdiseases.26

Dautović-Krkić S. et al.: Brucellosis - Emerging Zoonosis in Bosnia and HerzegovinaReferences1. Godfroid J, Cloeckaert A, Liautard JP, Kohler S,Fretin D, et al. From the discovery <strong>of</strong> the Maltafever’s agent to the discovery <strong>of</strong> a marine mammalreservoir, brucellosis has continuously beena re-emerging zoonosis. Vet Res. 2005 May-Jun;36(3):313-26.2. Husseini AS, Ramlawi AM. Brucellosis in theWest Bank, Palestine. Saudi Med J. 2004 Nov;25(11):1640-3.3. Mantur BG, Akki AS, Mangalgi SS, Patil SV, GobburRH, Peerapur BV. Childhood brucellosis-amicrobiological, epidemiological and clinicalstudy. J Trop Pediatr. 2004 Jun; 50(3):153-7.4. Kalaycioglu S, Imren Y, Erer D, Zor H, ArmanD. Brucella endocarditis with repeated mitralvalve replacement. J Card Surg. 2005 Marapr;20(2):189-92.5. Ozden M, Demirdag K, Kalkn a, Ozdemir H, YuceP. A case <strong>of</strong> brucella spondylodiscitis with extended,multiple-level involvement. South Med J. 2005Feb; 98(2):229-31.6. Seidel G. Pardo Ca, Newman-Toker D. OliviA, Eberhart CG. Neurobrucellosis presentingas leucoencephalopathy: the role <strong>of</strong> cytotoxicT lymphocytes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003Sep;127(9):e374--7.7. Cesur S, Ciftci A, Sozen TH, Tekeli E. A case <strong>of</strong>epididymo-orchitis and paravertebral abscess dueto brucellosis. J Infect. 2003 May;46(4):251-3.8. Hesseling AC, Marais BJ, Cotton MF. A child withneurobrucellosis. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2003 Jun;23(2):145-8.9. Almuneef M, Memish ZA, Al Shaalan M, Al BanyanE, Al-ALOLA s, Balkhy HH. Brucella melitensisbacteremia in children: review <strong>of</strong> 62 cases. JChemother. 2003.Fe;15(1):76-80.10. Zavod za Javno Zdravstvo Kantona <strong>Sarajevo</strong>, Zavodiza Javno Zdravstvo Entiteta države Bosne iHercegovine.11. Dautović-Krkić S, Lukovac E, Mostarac N,Hadžović M, Gazibera B, Muratović P. Zoonosisin infectious practica. Prvi simpozijum o zoonozamasa međunar. učešć. April 2005, 88.12. Sajma Krkić-Dautović. Snježana Mehanić. MerdinaFerhatović. Semra Čavaljuga. Brucellosis epidemiologicaland clinical aspects (Is brucellosis amajor public health problem in Bosnia and Herzegovina?).Bosnian J <strong>of</strong> basic Medic Scienc 2oo6;6(2) 11-15..13. Bosilkovski M., Dimzova M., Grozdanovski K,Natural history <strong>of</strong> brucellosis in an endemic regionin different time periods. Acta clin Croat.2009 Mar;48 (1):41-6.14. Bosilkovski M, Krteva L, Dimzova M, Kondova I.Brucellosis in 418 patients from the Balkan Peninsula:exposure related differences in clinicalmanifestation, laboratory test results, and therapyoutcome. Int J Infect Dis. 2007 Jul; 11 (4):342-7.Epub 2007 Jan 22.15. Muhammad N, Hossain MA, Musa AK, MahmudMC, Paul SK, Rahman MA, Haque N, Islam NT,Parvin US, Khan SI, Nasreen SA, Mahmud NU.Seroprevalence <strong>of</strong> human brucellosis among thepopulation at risk in rural area. Mymensingh MedJ. 2010 Jan; 19(1):1-4.27

Original PapersDiagnostic Significance <strong>of</strong> Platelet Count in Patients WithLung CancerSelma Arslanagić 1 , Hasan Žutić 2 , Nedžad Mulabegović 3 , Rusmir Arslanagić 4 ,Reuf Karabeg 1 , Naima Arslanagić 51Clinic <strong>of</strong> Plastic surgery Clinical Center<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>2Clinic <strong>of</strong> Pulmonal disease Clinical Center<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>3Institute <strong>of</strong> Pharmacology,Clinical Pharmacology and toxicology,Medical Faculty <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong>4Clinic <strong>of</strong> Ear, Throat, Nose diseases,Clinical Center <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>5Clinic <strong>of</strong> Dermatology, Clinical Center<strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>Correspondence to:Selma Arslanagić,Clinic <strong>of</strong> Plastic surgery,Clinical Center <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sarajevo</strong> <strong>University</strong>Bolnička 25, 71000 <strong>Sarajevo</strong>Bosnia and HerzegovinaTel: 033 297 366E-mail: arslas@hotmail.comA number <strong>of</strong> studies have shown that reactive thrombocytosiscan be associated with malignant disease. Thrombocytosiscan be inexpensive and easy indicator <strong>of</strong> solid cancer. It isconfirmed to be a paraneoplastic symptom. There is increasingevidence that interaction between tumor cells, endothelialcells and platelets may contribute to the development <strong>of</strong>metastases resulting in poor prognosis.Aim <strong>of</strong> our study was to analyze thrombocytosis in lung cancerpatients before any kind <strong>of</strong> therapy.Our research showed that there is significant difference inprevalence <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis between lung cancer patientsand control patients group. Elevated platelets count was morecommon in patient with advanced stages lung cancercancer,bat not significantly. There were no significant differences inthe occurrence <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis between the various histologicallung cancer types.Key wordsLung cancer, thrombocytosisIntroductionIn last decade thrombocytosis is consideredas an inexpensive and simple indicator <strong>of</strong>malignancy. Despite numerous studies andopinions, many authors don’t agree aboutquestion whether thrombocytosis is theultimate result <strong>of</strong> the actions <strong>of</strong> growth factorsthat create cell cancer. Opinions on thefrequency <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis in lung cancerare divided. Clinicians who have studiedthe significance <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis in lung28

Arslanagić S et al.: Diagnostic Significance <strong>of</strong> Platelet Count in Patients With Lung Cancercancercancer patients, consider that thethrombocytosis is clinically useful analysisto assess the diagnosis <strong>of</strong> malignancy in patientswith radiographically suspicious lungcancer.OBJECTIVES OF RESEARCH is to examinethe prevalence <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis inpatients with lung cancercancer. To analyzerelationship <strong>of</strong> platelets count in relation tothe histopathological type and TNM stagecancerlung cancer. To investigate a differencein platelets count between non smalllung cell cancer (NALCO) and small celllung cancer (SCLC).Material and methodsThe study involved two groups: group <strong>of</strong>patients with a confirmed diagnosis <strong>of</strong> lungcancer and control group.The group <strong>of</strong> patients with lung cancerIn the retrospective hospital based- cohortstudy was analysed thrombocytes 239 patientswith lung cancer, before any kind <strong>of</strong>therapy, hospitalized at the Clinic for PulmonaryDiseases, in the period since the1 st <strong>of</strong> January 2005 to 31 st December 2007.Classification <strong>of</strong> cancer was made accordingto the recommendations <strong>of</strong> the WorldHealth Organization (1).The study did not include patients withreactive thrombocytosis due to other diseasesas:– Inflammatory disease <strong>of</strong> lung;– Autoimmune disease;– Any other malignancy.In this study, we didn’t include any patientswho were under chemotherapy and/or are subjected to surgical intervention.The control groupDermatovenerology, which practically canbe considered healthy population. Theseparticipants were tested on possible allergieson medicaments. According to the protocolfor testing, all symptoms <strong>of</strong> allergic reactionsdisappeared before at least a monthbefore investigation and such person duringthe test did not take any therapy. The controlgroup according to sex and age correspondedto patients with lung cancer.Statistical analysis was performed usingChi- square 2x2 and Student-t test, utilizingStatistical Package for the Social Science,SPSS, (Version 13). The difference betweentwo groups was evaluated using ANOVAtest at 95% confidence interval. Data wereanalyzed descriptively and expressed as rawfrequencies and percentages, and 95% confidenceintervals (95%CI) were calculatedwith CIA. The significance level was set atp

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:28-34Table 1. Gender distribution <strong>of</strong> patients by histopathologic type <strong>of</strong> cancerHISTOLOGICALTYPE OFCANCERTotal patientsMALESEXFEMALENumber Percent Number Percent Number PercentAdenocarcinoma 105 43.8 85 35.6 20 8.4Squamous cellcarcinoma89 37.2 62 25.9 27 11.3Large cell carcinoma 3 1.5 2 0.8 1 0.4Micro cell carcinoma 42 17.5 34 14.2 8 3.4Total 239 100.0 183 76.5 56 23.5Table 2. Distribution <strong>of</strong> patients with NSCLC according to the TNM classificationHISTOPATHOLOGICALTYPE OF CANCERTotalpatientsTNM CLASSIFICATIONIIA IIB IIIA IIIB IVNum. Perc. Num. Perc. Num. Perc. Num. Perc. Num. Perc. Num. Perc.Adenocarcinoma 105 100.0 6 5.7 14 13.3 34 32.4 14 13.3 37 35.3Squamous cell carcinoma 89 100.0 3 3.3 6 6.7 40 44.9 21 23.7 19 21.4Large cell carcinoma 3 100.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 1 33.3 1 33.3 1 33.3Total 197 100.0 9 4.6 20 10.1 75 38.0 36 18.4 57 28.9The distribution <strong>of</strong> SCLC patients accordingto TNM classification is shown onTable 3. In the extended stage <strong>of</strong> lung cancerwere more affected (55.0%) compared to thelimited stage (45.0%).Table 3. Distribution <strong>of</strong> micro cell carcinomapatients according to tnm classificationHistopathological type<strong>of</strong> cancer according toTNM classificationNumber <strong>of</strong>patientsPercentageLIMITED 20 45.0EXTENDED 22 55.0TOTAL 42 100.0Statistical analysis, shown on Figure 1,ANOVA test, demonstrated that there is statisticallysignificant differences mean values<strong>of</strong> platelets count between lung cancer patientsand control group at the level <strong>of</strong> significance<strong>of</strong> p

Arslanagić S et al.: Diagnostic Significance <strong>of</strong> Platelet Count in Patients With Lung CancerFigure 14. The mean values platelets count for eachgroups <strong>of</strong> lung cancer group are significantlydifferent from the mean values <strong>of</strong> plateletscount <strong>of</strong> the control group at the significancelevel <strong>of</strong> p0.05. The meanplatelets values <strong>of</strong> different SCLC stages isshown on Table 5.Table 6 presents the statistical analysis <strong>of</strong>mean values in platelets count <strong>of</strong> earlier stagesNSCLC (IIA and IIB) to advanced stages(IIIA, IIIB and stage IV). There were noTable 4. Analysis <strong>of</strong> mean values <strong>of</strong> platelet* specific histopathological lung cancer and control groupsPatients Xmin XmaxaverageX95* % CIstandarddeviation(+/-)medianPatients suffering fromadenocarcinoma134 687 385 366-404 117.0 396controlgroup120 373 222 197-246 50.9 218Patients with squamouscell carcinoma182 811 375 356-393 106.0 391controlgroup120 373 222 199-244 50.9 218Patients suffering fromlarge cell carcinoma238 393 318 257-378 77.6 323controlgroup120 373 222 199-244 51.1 218Patients with small celllung cancer134 793 324 294-354 143.0 282controlgroup120 373 222 196-247 51.1 218LEGEND: platelet* = platelet count x 10 9 /LCI = confidence intervallikelysignificancep

Folia Medica 2011; 46 No 1:28-34Table 6. Analysis <strong>of</strong> the mean platelet* count <strong>of</strong> patients with NSCLS according to the TNM classification (IIAand IIB in relation IIIA, IIIB and IV)TNMCLASSIFICATIONPatients with NSCLC(IIA, IIB)Patients with NSCLC(IIIA, IIIB i IV)XminXmaxaverageX95 % CIstandarddeviation(+/-)median207 601 374 331-415 108 350134 811 408 389-426 120 408likelysignificancep>0.05r.n.sLEGEND: platelet* = platelet count x 10 9 /LTable 7. Analysis <strong>of</strong> mean values <strong>of</strong> platelet* counts in patients with NSCLS and SCLSPatients Xmin XmaxPatients withNSCLCPatients withSCLCaverageX95 % CIstandarddeviation(+/-)median134 811 377 360-393 112 390134 793 324 228-360 143 282likelysignificancep>0.05r.n.s*LEGEND: platelet* = platelet count x 10 9 /Lstatistically significant differences in meanvalues <strong>of</strong> platelets count between two testedgroups at the significance level p>0.05.Statistical analysis <strong>of</strong> mean values <strong>of</strong>platelets count NSCLC compared to SCLCis shown on Table 7. There was no significantdifference at the significance level p>0.05.DiscussionOne <strong>of</strong> the most common blood abnormalities<strong>of</strong> patients with solid tumors is thrombocytosis(2-4,5-8,13). Several studies haveconfirmed thrombocytosis as paraneoplasticsymptom (2-6,8-12).In a certain percentage, reactive thrombocytosiswas observed, in the diagnosis <strong>of</strong>lung cancer, prior chemotherapy and/or surgery(2-4).Pathogenesis <strong>of</strong> reactive thrombocytosisassociated with malignancy has not yet beencompletely solved. The precise mechanism<strong>of</strong> reactive thrombocytosis may be due tomediators secreted by tumor cells, whichdirectly affect production bone marrowmegakaryocytes. Mediators <strong>of</strong> tumor cells,such as IL-6, IL-1, IL-11 and macrophagecolony-stimulating factor (14) are probablyresponsible for the thrombocytosis asparaneoplastic symptom (13,15). In addition,some tumors, such as ovarian cancer(15,16), hepatoblastoma and hepatocellularcancer produce thrombopoietin, which hasthe effect on thrombocytosis (7,17).Recent studies indicate interaction betweentumor cells, endothelial cells andplatelets which contribute to the development<strong>of</strong> metastases and poor prognosis onsurvival (13,18,19,20). However, the prognosticsignificance <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis onsurvival time has not yet been elucidated.Platelets help tumor spread by increasingthe adhesion <strong>of</strong> tumor cells in the endothelium<strong>of</strong> blood vessels and accumulating inthe tumor cells. In this way, at the same time,platelets prevent the detection and removal<strong>of</strong> tumor cells by the immune system (21).The largest number <strong>of</strong> patients with lungcancer in our study was from 51 to 60 years<strong>of</strong> age (No=92, or 38.5%). Number <strong>of</strong> men32

Arslanagić S et al.: Diagnostic Significance <strong>of</strong> Platelet Count in Patients With Lung Cancer(No. = 183, or 76.6%) was three times greaterthan the number <strong>of</strong> women (No = 56, or23.4%). Ratio <strong>of</strong> men to women was 3.2:1.Pedersen LM and Milman N (3), like GarciaPrim JM et al. (21), had similar gender ratio.About 43.8% <strong>of</strong>NSCLC was adenocancer,37.2% squamous cell cancer and 1.5%large cell lung cancer. Similar results havebeen reported in study Pedersen LM. andMilman N. (3.5), Garcia Prim JM et al. (22)and Moyer P (23).In our study, from the 42 patients sufferingfrom SCLC, 20 patients (45.0%) were inlimited stage according to TNM classification,and 22 patients (55.0%) in the expandedstage. We found that SCLC men fourtimes more than women. Pedersen LM andMilman N (3,5), Garcia Prim JM et al. (22)and Moyer P (23) have found similar results.The mean platelets value <strong>of</strong> lung cancerpatients in our study was 395x10 9 /l, standarddeviation <strong>of</strong> 122.0. The lowest plateletsvalues was 134x10 9 /l. The largest number <strong>of</strong>platelets was 811x10 9 /l.Different authors found different results<strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis in lung cancer patientsas results a different time when authors determinednumber <strong>of</strong> platelets. Aoe K et al.(2) determined the number <strong>of</strong> platelets atthe first hospital admission. The prevalence<strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis at that time was lower,about 16%. Survival time <strong>of</strong> lung cancer patientswith thrombocytosis was 7.5 monthsand was significantly lower to 10.1 monthsto lung cancer patients without thrombocytosis.Statistical analysis <strong>of</strong> mean platelets values<strong>of</strong> specific histopathological types <strong>of</strong>cancer (adenocancer, squamous cell cancer,large cell cancer and small cell lung cancer)to the control group, for each type <strong>of</strong> cancer,were statistically significant difference.On the basis <strong>of</strong> our research , we can concludethat thrombocytosis was more presentin advanced TNM stages lung cancer , butnot significantly, compared to less advancedstages <strong>of</strong> lung cancer. Results supporting ourfindings have been reported in study Aoe Ket al (2), Pedersen LM and Milman (3,5),Engan T, Hannisdal E (11), Gislason T et al.(24).Unlike these results, Inoue K et al. (25)found a positive association <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosisas tumor size as like TNM stage <strong>of</strong> renalcell cancer. The same authors not foundpositive correlation between thrombocytosisand histological type <strong>of</strong> cancer. They als<strong>of</strong>ound that the number <strong>of</strong> platelets, after renalcell cancer nephrectomy, normalized inall patients with thrombocytosis.We must emphasize that there is verylittle data in the literature examined thepresence <strong>of</strong> thrombocytosis in certain histopathologicaltypes <strong>of</strong> lung cancer.There were no significant difference betweenmean values <strong>of</strong> platelets count NSCLCand SCLC in our research. Pedersen LM andMilman N (5) found significantly higherthrombocytosis in patients with SCLC inrelation to thrombocytosis in patients withNSCLC. The same authors attach great importanceon present thrombocytosis in patientswith lung cancer. They concluded thatthe tumors markers cannot provide moreinformation about the malignant nature <strong>of</strong>some changes in relation to the increasednumber <strong>of</strong> platelets.ConclusionThere are significant differences in meanvalues <strong>of</strong> platelets count among lung cancerpatients in relation to the control group.We did not found a statistically significantdifference between mean values <strong>of</strong> plateletscount in NSCLC in relation to SCLC.We haven’t found a significant differencein the variability <strong>of</strong> the mean values <strong>of</strong> plateletscount between different TNM stages <strong>of</strong>lung cancer.33