3. Dagnino et al - Nucleo Milenio | Intervención Psicológica y ...

3. Dagnino et al - Nucleo Milenio | Intervención Psicológica y ...

3. Dagnino et al - Nucleo Milenio | Intervención Psicológica y ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

P. <strong>Dagnino</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. 79first one, each researcher individu<strong>al</strong>ly coded the specificCommunicative Intentions (Exploring, Attuning,and Resignifying) that appeared in the speakingturns (according to the TACS system; see below formore d<strong>et</strong>ails). The inter-rater agreement of these individu<strong>al</strong>codes is adequate (κ ≥ .71, 95% IC [.63, .87]). Inthe second stage, the pairs of researchers discussedtheir differences in coding in order to obtain a fullyagreed fin<strong>al</strong> coding (100% agreement). These agreedcategories were included in logistic regression models.MeasuresCommunicative Intentions. As stated previously,a Communicative Intention refers to the purposeexpressed by the speaker’s words, as considered bythe TACS (Krause <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2010). In other words, it refersto “what the participant is trying to achieve withhis/her communication” (V<strong>al</strong>dés <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2010, p. 122),and not wh<strong>et</strong>her this effect is actu<strong>al</strong>ly achieved. Forexample, the therapist could verb<strong>al</strong>ize with theCommunicative Intention of Resignifying, and itwould be coded as such regardless of wh<strong>et</strong>her or notthe client accepts the new meaning. 1According to the TACS, there are three types ofCommunicative Intentions: Exploring, Attuning,and Resignifying. Exploring is coded when client ortherapist asks for or provides information that is unknown,or clarifies contents (e.g., the therapist asks“how would you describe your husband so that I cang<strong>et</strong> an idea of him?”). Attuning is coded when thepurpose is to understand or to be understood by theother; to harmonize with the other; and/or to providefeedback (e.g., the therapist says “l<strong>et</strong> me see if Iunderstand, what you are trying to say is that…” orthe client expresses “I need you to understand what Iam trying to explain”). Resignifying is coded whenthere is the purpose of generating or consolidatingnew meanings (e.g., the therapist says “You are tellingme that you want to do som<strong>et</strong>hing, but that youre<strong>al</strong>ly don’t dare. So I think that happens in otherparts of your life and I think that it is happeninghere, it is happening to you right now at this verymoment” (Krause <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2010, p. 19).Data an<strong>al</strong>ysisLogistic regression an<strong>al</strong>yses were conducted to testthe study’s hypothesis. To perform the statistic<strong>al</strong>an<strong>al</strong>ysis, each one of the Communicative Intentionswas transformed into a dichotomous dependent variable.For example, Exploring was coded one “1”when it was used and coded zero “0” when Attuningor Resignifying appeared. This dichotomization processmakes it possible to compare the probability of1TACS was origin<strong>al</strong>ly developed with data from five differentpsychotherapeutic approaches (psychodynamic, soci<strong>al</strong>constructionist,CBT, gest<strong>al</strong>t and humanistic).occurrence of a category (coded 1) with respect tothat of other categories (coded 0).Three simple logistic regression equations were estimatedto test the first hypothesis about the differencesb<strong>et</strong>ween therapists’ and clients’ CommunicativeIntentions. Each of the dichotomized CommunicativeIntentions was regressed on the Actor variable(Clients = 1 and Therapist = 0 as reference category).A similar procedure was used to test the secondhypothesis, comparing the probability of occurrencefor Communicative Intention types through thechange episode stages. Change episodes were dividedinto five stages (henceforth, the variable will be referredto as change episode stage). The fin<strong>al</strong> changeepisode stage was composed of the last six speakingturns, in order to include the “change moment” inthis stage. When the remaining speaking turns weremore than 15, the initi<strong>al</strong> change episode stage wasformed by the first six speaking turns, so as to homogeniz<strong>et</strong>he number of speaking turns belonging tothe initi<strong>al</strong> and fin<strong>al</strong> change episode stages; however,if the remaining speaking turns were b<strong>et</strong>ween 10 and15, the initi<strong>al</strong> change episode stage was formed byfive or fewer Communicative Intentions, dependingon the length of each episode. After defining the initi<strong>al</strong>and the fin<strong>al</strong> change episode stages, the remainingspeaking turns were divided into three equ<strong>al</strong>parts, coding only the middle section as the “middlechange episode stage.” The other two parts of themiddle stage were considered transition<strong>al</strong> stages andwere not included in the an<strong>al</strong>ysis. Each of the dichotomizedCommunicative Intentions was regressed onchange episode stage. Change episode stage was includedas a categoric<strong>al</strong> variable comparing the initi<strong>al</strong>and the middle stages vs. the fin<strong>al</strong> stage (fin<strong>al</strong> stage asreference category).Simple logistic regression equations were estimatedto test the third hypothesis, comparing the probabilityof occurrence of Communicative Intentiontypes through the phase of the therapy. The therapyphase variable was constructed by dividing the tot<strong>al</strong>number of sessions into three equ<strong>al</strong> parts, so that thebeginning, middle and fin<strong>al</strong> phases would have a similarnumber of sessions. For example, in a therapeuticprocess of 18 sessions, each phase will have 6 sessions(the number of sessions per therapeutic process isshown in Table 1). Therapy phase was included as acategoric<strong>al</strong> variable comparing the first and secondphases vs. the third phase (third phase as referencecategory).To test the last hypothesis two multiple logistic regressionan<strong>al</strong>yses were carried out. These an<strong>al</strong>ysesshow the variations of Communicative Intentions inthe different change episode stages and the phases ofthe therapeutic process, and reve<strong>al</strong> any differencesb<strong>et</strong>ween the Communicative Intentions of clientsand therapists in both types of evolution. To performthese statistic<strong>al</strong> an<strong>al</strong>ysis two independent logistic regressionequations were estimated:

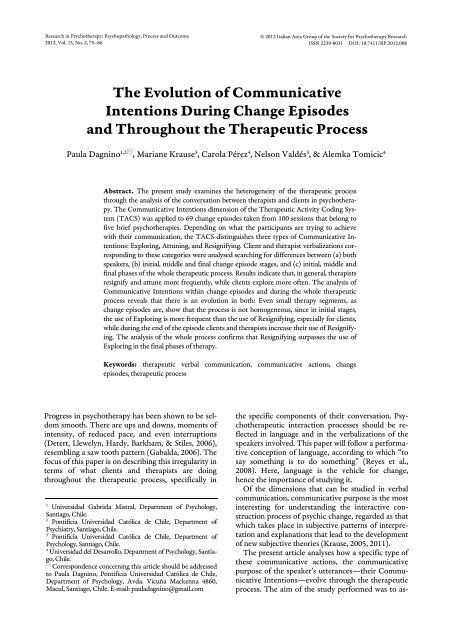

80 The evolution of communicative intentions(a) Logit (y) = a Constant + b1 Actor + b2 Stage (I/F) + b3 Stage (I/F)+ [b4 Actor* Stage (I/F)] + [b5 Actor* Stage (I/F)](b) Logit (y) = a Constant + b1 Actor + b2 Phase (1/3) + b3 Phase (1/3)+ [b4 Actor* Phase (1/3)] + [b5 Actor* Phase (2/3)]The main effects of each of the predictors: Actors,change episode stages or phases of the therapeuticprocess were included first in the logistic regressionequation. Afterwards, interaction terms were addedto the model.Logistic regression results are presented followingthe recommendations by Peng, Lee, and Ingersoll(2002). Tables displaying main effects param<strong>et</strong>ersare presented for <strong>al</strong>l the variables an<strong>al</strong>ysed. The interactionterm is incorporated only when it is statistic<strong>al</strong>lysignificant. Odds ratios were estimated to showinteraction terms with the simplest model of predictors.No relevant differences exist b<strong>et</strong>ween the simpleand the compl<strong>et</strong>e models.ResultsConsidering both clients’ and therapists’ speech conjointly(N = 2060), the most frequent CommunicativeIntention is Exploring (45.2%). Resignifying comessecond with 39.4%, while Attuning reaches 15.4%.Clients and therapists Communicative IntentionsAs was hypothesized, clients and therapists differ regardingtheir use of the three Communicative Intentions(see Figure 1). Statistic<strong>al</strong>ly significant differencescan be observed in the probability of occurrenceof the Communicative Intentions in client andtherapist speech. Therapists attune (β = -.96, OR =.39, p < .001, 95% CI [.30, .50]) and resignify (β =-.38, OR = .68, p < .001, 95% CI [.57, .82]) more oftenthan clients; in contrast, the latter tend to exploremore frequently (β = .84, OR = 2.31, p < .001, 95%CI [1.93, 2.76]).Percentage60%50%40%30%20%10%0%ClientTherapistExploring Attuning ResignifyingFigure 1. Client and therapist use of the different communicativeintentions.Percentage70%60%50%40%30%20%10%0%ExploringResignifyingIniti<strong>al</strong> (1) 2 Middle (3) 4 Fin<strong>al</strong> (5)Communicative Intentions through thechange episode (change episode stages)AttuningFigure 2. Communicative intentions at different changeepisode stages.Figure 2 shows the use of the Communicative Intentionsby both participants of the therapeutic di<strong>al</strong>ogthroughout the different change episode stages. Theresults indicate that the probability of Exploring ishigher in the initi<strong>al</strong> (β = 1.06, OR = 2.88, p < .001,95% CI [2.18, <strong>3.</strong>82]) and middle stages (β = .58, OR= 1.79, p < .001, 95% CI [1.36, 2.35]) compared tothe fin<strong>al</strong> stage of the change episode. The oppositepattern was observed in the case of Resignifying: Theprobability of Resignifying is lower in the initi<strong>al</strong> (β =-1.12, OR = .33, p < .001, 95% CI [.26, .44]) andmiddle stages (β = -.58, OR = .56, p < .001, 95% CI[.42, .73]) compared to the fin<strong>al</strong> change episodestage. The use of Attuning remains constant in th<strong>et</strong>hree change episode stages (Model χ 2 (2, N = 1266) =.07, p = .97, & -2LL = 1067.11). These results are consistentwith the second hypothesis: Since change momentsare characterized by the construction of newmeanings, communication within change episodes willevolve in the direction of a more frequent use of Resignifyingand a less frequent use of Exploring.Communicative Intentions throughout the therapeuticprocess (phases of therapy)Communicative intentions were used differenti<strong>al</strong>lyaccording to the phase of the therapeutic process bythe participants in the therapeutic di<strong>al</strong>og (see Figure3). Statistic<strong>al</strong>ly significant differences were observedin the probability of occurrence of Exploring and Attuning,but not in the probability of Resignifying(Model χ 2 (2, N = 2060) = 2.25, p = .32, & -2LL =2759.67).Compared with the fin<strong>al</strong> phase (third phase of therapy),the probability of Exploring is higher both in theiniti<strong>al</strong> (β = .36, OR = 1.43, p < .001, 95% CI [1.15,1.79]) and middle phases of therapy (β = .32, OR =1.37, p < .05, 95% CI [1.09, 1.72]). Addition<strong>al</strong>ly, in the

P. <strong>Dagnino</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. 81Percentage60%50%40%30%20%10%0%Exploring Attuning ResignifyingPhase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3Figure <strong>3.</strong> Use of communicative intentions at differentstages of therapy.third therapy phase there was a more extensive use ofAttuning than in the first phase (β = -.41, OR = .67, p< .01, 95% CI [.50, .90]), but no differences were observedwhen comparing the second and third phases(β = -.27, OR = .76, p =. 71, 95% CI [.57, 1.02]).These results parti<strong>al</strong>ly support the third hypothesis.Although a decrease in Exploring was observed, therewas no evidence of an increase in Resignifying as th<strong>et</strong>herapy process progressed.Evolution of client and therapistCommunicative Intentions in changeepisode stages and therapy phasesThe fin<strong>al</strong> hypothesis stipulates that the pattern of theevolution of Communicative Intentions in differentchange episode stages and therapeutic phases will besimilar. Given the results showing the differences b<strong>et</strong>weenclients and therapists, this hypothesis must b<strong>et</strong>ested considering the speakers of the therapeuticdiscourse and the micro (change episode stages) andmacro (therapy process phases) moments of th<strong>et</strong>herapeutic process jointly.Change episode stages. In order to an<strong>al</strong>yse theeffect of the change episode stages on the probabilityof using Communicative Intentions (Exploring, Attuningand Resignifying), each of dichotomized dependentvariables was regressed on the variables actors,change episode stages and their interaction.As Table 2 shows, the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween the changeepisode stage and the probability of Exploring andResignifying depends on who the speaker is (significantinteraction terms). There were no significantinteractions b<strong>et</strong>ween actor and change episode stageswhen predicting Attuning. 2Odds ratios were estimated to account for the in-2Direct effects are not interpr<strong>et</strong>ed when interactions are present.teraction terms (Actor X Change episode stage).When the odds ratio is equ<strong>al</strong> to 1, both categorieshave the same odds. When the odds ratio is greaterthan 1, the odds for one of the categories of variables(i.e., the clients) are greater than the odds for the referencecategory (i.e., the therapist). When the oddsratio is less than 1, the reverse is true (Hosmer &Lemeshow, 2000).The results indicate that clients were <strong>3.</strong>7 timesmore likely to use Exploring than therapists in theiniti<strong>al</strong> change episode stage (OR = <strong>3.</strong>72, 95% IC[2.40, 5.75]). This pattern was less clear at the end ofthe change episode (fin<strong>al</strong> stage), where clients Exploredonly one and a h<strong>al</strong>f times more than therapists(OR = 1.69, 95% IC [1.13, 2.54]).With respect to Resignifying, the odds ratios indicat<strong>et</strong>hat clients were less likely to resignify thantherapists in the initi<strong>al</strong> (OR = .43, 95% IC [.26, .68]),and middle change episode stages (OR = .67, 95% IC[.45, .99]), <strong>al</strong>though this difference was less clear inthe fin<strong>al</strong> stage, when clients and therapists had thesame probability of Resignifying (OR = 1.17, 95% IC[.81, 1.71]).In brief, the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween the change episodestage and the probability of Exploring depends onwho the speaker is. In the initi<strong>al</strong> change episode stag<strong>et</strong>he clients explore much more frequently than therapists(3 times more frequently); in contrast, thisCommunicative Intentions asymm<strong>et</strong>ry decreases inthe fin<strong>al</strong> change episode stage. Addition<strong>al</strong>ly, som<strong>et</strong>hingsimilar occurs with Resignifying. Communicationasymm<strong>et</strong>ry, present in the initi<strong>al</strong> and middlechange episode stages and characterized by a higherResignifying rate by the therapist compared with theclient, disappears in the fin<strong>al</strong> change episode stage.Phases of the therapeutic process. In order to an<strong>al</strong>ys<strong>et</strong>he effect of the phases of the therapeutic processon the probability of using each of the CommunicativeIntentions, each of the dichotomized dependentvariables was regressed on the variables actors, therapyphase, and their interaction.As Table 3 shows, the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween phases oftherapy and the probability of Exploring, Attuningand Resignifying depends on who the speaker is (significantinteraction terms).Odds ratios indicate that clients are more likely toexplore than therapists in the first (OR = 2.99, 95%IC [2.22, 4.02]) and second phases (OR = 2.69, 95%IC [1.99, <strong>3.</strong>64]) compared to the third therapy phase.At the end of the therapy (third phase), this patternis less clear; as the use of Exploring by clients andtherapists becomes more similar (OR = 1.46, 95% IC[1.03, 2.05]).With respect to Attuning, odds ratios indicate thatclients were less likely to use Attuning than therapistsin the first therapy phase (OR = .22, 95% IC [.12,.38]) compared to the third therapy phase. In the lasttherapy phase, clients increased their tendency to Attune,thus establishing a less asymm<strong>et</strong>ric pattern in

84 The evolution of communicative intentionschange across a range of theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong>ly diverse treatments(Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds,2011; Horvath & Symonds, 1991; Martin, Garske, &Davis, 2000), and can be defined as the dynamic interperson<strong>al</strong>process where verb<strong>al</strong>izations <strong>al</strong>lude totherapist empathy, degree of client involvement intreatment, being understood, <strong>et</strong>c. (Horvath &Greenberg, 1994; Krause <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2011). All of these elementscan be found under the concept of Attuning,which refers to communicative and emotion<strong>al</strong> adjustment(understanding or being understood by theother, achieving a harmonious relationship, and de<strong>al</strong>ingwith feedback issues). Therefore, having a constantpresence of Attuning is regarded as a fundament<strong>al</strong>requisite for change, <strong>al</strong>lowing the constructionof new meanings and thus of subjective change(Krause, 1992).On the other hand, as was hypothesized, the resultsof the an<strong>al</strong>ysis of Communicative Intentions throughoutthe therapeutic process show that verb<strong>al</strong> communicationcan distinguish b<strong>et</strong>ween phases, thus providingevidence for the notion that therapy evolves (Hill,2005; Krause <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2007), with clients and therapistsgoing through different types of communication.When considering discourse of clients and therapistsjointly, the initi<strong>al</strong> and middle phases of the processhave a similar pattern, in which Exploring predominatesover Attuning and Resignifying. This patternchanges in the fin<strong>al</strong> phase of therapy, where Exploringis less frequent and Attuning increases comparedto the first.In contrast, when their discourse is separated byspeaker, the clients’ increased use of Resignifying atthe end of the process becomes apparent. This resultcan be understood from a clinic<strong>al</strong> point of view, as clientstend to need less of the therapist’s interpr<strong>et</strong>ationswhen they acquire a certain degree of autonomy in theconstruction of their own subjective theories (Krause,2005, 2011). On the other hand, the more frequent useof Attuning can be related to the fact that when terminationcomes, especi<strong>al</strong>ly in brief psychotherapies(like the ones studied), there is a need to ev<strong>al</strong>uate theprocess, provide feedback, check the work done, assessprogress, <strong>et</strong>c.The results of this study show that the therapeuticprocess—at least when the focus is on verb<strong>al</strong> clienttherapistcommunication—is not homogeneous (e.g.,Mergenth<strong>al</strong>er, 1998), either in terms of its glob<strong>al</strong> evolutionor its microprocess. Even sm<strong>al</strong>l therapy segmentsdisplay such h<strong>et</strong>erogeneity. These results go beyondthe existing literature, <strong>al</strong>lowing the developmentof a model that facilitates understanding of the complexitiesof the therapeutic process by simultaneouslyincluding a macro level (session to session) and a microlevel (within session) approach.In gener<strong>al</strong> terms, a par<strong>al</strong>lelism is observed b<strong>et</strong>weenthe evolution of change episodes and the glob<strong>al</strong> evolutionof therapeutic phases. Considering these results,this model has a hologramatic characteristic, in thesense that the features observed at the macro level(e.g., the evolution of Communicative Intentionsthroughout the psychotherapy) are <strong>al</strong>so observed atthe micro level (e.g., the evolution of CommunicativeIntentions within change episodes). This characteristichas implications not only for ongoing and futureresearch, but <strong>al</strong>so for clinic<strong>al</strong> practice.With respect to clinic<strong>al</strong> practice, these results mightencourage therapists to attend to their own and the client’sverb<strong>al</strong>izations, since they show that therapistsshould <strong>al</strong>low and even encourage clients to explore initi<strong>al</strong>ly,not forg<strong>et</strong>ting to resignify what is said during theconversation, while constantly attuning with the client.This gener<strong>al</strong> strategy does not have to be used onlywithin sessions (micro level): Therapists could <strong>al</strong>so considerthe phases of the therapeutic process (macro level),<strong>al</strong>lowing the client to increasingly resignify duringthe whole process so he/she can gain autonomy in theconstruction of his/her subjective change.With respect to future directions of research, the resultsof this study suggest linking Communicative Intentionsto the evolution of change—through the useof Generic Change Indicators (Krause <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>., 2007), inorder to ev<strong>al</strong>uate how the verb<strong>al</strong>izations of the actorslead to different types of change—and different outcomes,comparing successful and unsuccessful therapies.Furthermore, it would be important to deepenthe an<strong>al</strong>ysis of the relation b<strong>et</strong>ween CommunicativeIntentions and the construction of the therapeutic <strong>al</strong>liance.An example of this would be to study the use ofAttuning as part of the construction of a positive bondby relating its use to measurements of therapeutic <strong>al</strong>liancelike the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI;Horvath & Greenberg, 1986).A limitation of this study is the fact that the casesincluded in the study, since they come from natur<strong>al</strong>s<strong>et</strong>tings, do not have form<strong>al</strong> DSM-IV diagnosis.Therefore, a ch<strong>al</strong>lenging research topic for the futurewould be to relate the evolution of CommunicativeIntentions to different client profiles; for example,looking at a specific disorder, such as depression, oreven more ambitiously, at person<strong>al</strong>ity disorders.AcknowledgementThis research was supported by the Chilean Nation<strong>al</strong>Fund for Scientific and Technologic<strong>al</strong> Development,Projects Nº 1060768 and Nº 1080136 and the ChileanMillennium Scientific Initiative, Project Nr.NS100018.ReferencesAnderson, R. H. (1997). Conversation, language, and possibilities:A postmodern approach to therapy. New York: BasicBooks.Bastine, R., Fiedler, P., & Kommer, D. (1989). Was ist therapeutischan der Psychotherapie? [What is therapeuticabout psychotherapy?]. Zeitschrift für klinische Psychologieund Psychotherapie, 18(1), 3–22.Bucci, W. (1993). The development of emotion<strong>al</strong> meaning infree association: A multiple code theory. In A. Wilson, & J.

P. <strong>Dagnino</strong> <strong>et</strong> <strong>al</strong>. 85E. Gedo (Eds.), Hierarchic<strong>al</strong> concepts in psychoan<strong>al</strong>ysis (pp.3–47). New York: Guilford Press.de la Parra, G., & von Bergen, A. (2001, June). Administrationof the Outcome Questionnaire OQ-45.2 in Santiago deChile: V<strong>al</strong>idity, reliability, applicability, normative data andclinic<strong>al</strong> projections. Paper presented at the 32nd Internation<strong>al</strong>Congress of the Soci<strong>et</strong>y for Psychotherapy Research,Montevideo, Uruguay.de la Parra, G., von Bergen, A., & del Rio, M. (2002). PrimerosH<strong>al</strong>lazgos de la aplicación de un instrumento que mideresultados psicoterapéuticos en una muestra de pacientes yde poblacion gener<strong>al</strong> [Preliminary findings of the applicationof an instrument that measures psychotherapeutic results ina sample of patients and gener<strong>al</strong> population]. Revista Chilenade Neuropsiquiatría, 40, 201–209.D<strong>et</strong>ert, N., Llewelyn, S., Hardy, G., Barkham, M., & Stiles, W.(2006) Assimilation in good-and poor-outcome cases ofvery brief psychotherapy for mild depression: An initi<strong>al</strong>comparison. Psychotherapy Research, 16(4), 393–407. doi:10.1080/10503300500294728Elkin, L., Parloff, J. M., Hadley, S. W., & Autrey, J. H. (1985).NIMH treatment of depression collaborative research program.Archives of Gener<strong>al</strong> Psychiatry, 42, 305–316.doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790260103013Elliott, R. (1984). A discovery-oriented approach to significantchange events in psychotherapy: Interperson<strong>al</strong> process rec<strong>al</strong>land comprehensive process an<strong>al</strong>ysis. In L. Rice & L. S.Greenberg (Eds.), Patterns of change: intensive an<strong>al</strong>ysis of psychotherapyprocess (pp. 249–286). New York: Guilford.Elliott, R. (1985). Helpful and nonhelpful events in briefcounseling interviews: An empiric<strong>al</strong> taxonomy. Journ<strong>al</strong> ofCounseling Psychology, 32(3), 307–322. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.32.<strong>3.</strong>307Elliott, R. (1991). Five dimensions of therapy process. PsychotherapyResearch, 1, 92–10<strong>3.</strong> doi: 10.1080/ 10503309112331335521Elliott, R., & Shapiro, D. A. (1992). Client and therapist asan<strong>al</strong>ysts of significant events. In S. G. Toukmanien & D. L.Rennie (Eds.), Psychotherapy process research: Paradigmaticand normative approaches (pp. 163–186). Newbury Park,CA: Sage.Evans, M. D., Piasecki, J. M., Kriss, M. R., & Hollon, S. D.(1984). Raters’ manu<strong>al</strong> for the Collaborative Study PsychotherapyRating Sc<strong>al</strong>e‒Form 6. Minneapolis: MN Universityof Minnesota and the St. Paul-Ramsey Medic<strong>al</strong> Center.Fernández, O., Herrera, P., Krause, M., Pérez, J. C., V<strong>al</strong>dés, N.,Vilches, O., & Tomicic, A. (2012). Episodios de Cambio yEstancamiento en Psicoterapia: Características de lacomunicación verb<strong>al</strong> entre pacientes y terapeutas. [Changeand Stuck Episodes in Psychotherapy: Characteristics ofVerb<strong>al</strong> Communication b<strong>et</strong>ween Patients and Therapists].Terapia Psicológica, 30(2), 5–22. doi: 10.4067/S0718-48082012000200001Fiedler, P., & Rogge, K. E. (1989). Zur Prozeßuntersuchungpsychotherapeutischer Episoden. Ausgewählte Beispieleund Perspektiven. [Towards process research of psychotherapeuticepisodes. Selected examples and perspectives].Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie,, 18,45–54.Fitzpatrick, M. R., & Chamodraka, M. (2007). Participantcritic<strong>al</strong> events: a m<strong>et</strong>hod for identifying and isolating significanttherapeutic incidents. Psychotherapy Research, 17,622–627. doi: 10.1080/10503300601065514.Gab<strong>al</strong>da, I. C. (2006). The assimilation of problematic experiencesin linguistic therapy of ev<strong>al</strong>uation: How did María assimilat<strong>et</strong>he experience of dizziness?. Psychotherapy Research,16, 422–435. doi: 10.1080/10503300600756436.Goldberg, D. P., Hobson, R. F., Maguire, G. P., Margison, F. R.,O’Dowd, T., Osborn, M., & Moss, S.. (1984). The clarificationand assessment of a m<strong>et</strong>hod of psychotherapy. British Journ<strong>al</strong>of Psychiatry, 144, 567–575. doi: 10.1192/bjp.144.6.567Goldfried, M. R., Raue, P. J., & Castonguay, L. G. (1998). Th<strong>et</strong>herapeutic focus in significant sessions of master therapists:A comparison of cognitive-behavior<strong>al</strong> and psychodynamicinterperson<strong>al</strong>interventions. Journ<strong>al</strong> of Consulting and Clinic<strong>al</strong>Psychology, 66(5), 803–810. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.803Hayes, A. M., Laurenceau, J.-P., Feldman, G., Strauss, J. L., &Cardaciotto, L. (2007). Change is not <strong>al</strong>ways linear: Thestudy of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change inpsychotherapy. Clinic<strong>al</strong> Psychology Review, 27(6), 715–72<strong>3.</strong>doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008Heatherington, L. (1988). Coding relation<strong>al</strong> communicationcontrol in counseling: Criterion v<strong>al</strong>idity. Journ<strong>al</strong> of CounselingPsychology, 35(1), 41–46. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.35.1.41Hill, C. E. (1978). Development of a system for classifyingcounselor responses. Journ<strong>al</strong> of Counseling Psychology, 25,461–468. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.25.5.461Hill, C. E. (2005). Therapist techniques, client involvement,and the therapeutic relationship: inextricably intertwinedin the therapy process. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research,Practice, Training, 42(4), 431–442. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.42.4.431Hölzer, M., Erhard, M., Pokorny, D., Kächele, H., & Luborsky,L. (1996). Vocabulary measures for the ev<strong>al</strong>uation of therapyoutcome: Re-studying transcripts from the Penn PsychotherapyProject. Psychotherapy Research, 6(2), 95–108. doi:10.1080/10503309612331331618Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D.(2011). The <strong>al</strong>liance in adult psychotherapy. Psychotherapy:Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 48(1), 9–16. doi:10.1037/a0022186Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1986). The developmentof the Working Alliance Inventory. In L. Greenberg & W.Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A researchhandbook (pp. 529–556). New York: Guilford Press.Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1994). Introduction. InA. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working <strong>al</strong>liance:Theory, research, and practice. New York: Wiley.Horvath, A. O., & Symonds, B. D. (1991). Relation b<strong>et</strong>weenworking <strong>al</strong>liance and outcome in psychotherapy: A m<strong>et</strong>aan<strong>al</strong>ysis.Journ<strong>al</strong> of Counseling Psychology, 38(2), 139–149.doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.38.2.139Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression(2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.Krause, M. (1992). Efectos subj<strong>et</strong>ivos de la ayuda psicológica:Discusión teórica y presentación de un estudio empírico[Subjective effects of psychologyc<strong>al</strong> help: Theoricdiscusión and presentation o an empiric study]. Psykhe, 1,41–52. R<strong>et</strong>rieved from http://www.psykhe.cl/index.php/psykhe/article/view/15Krause, M. (2005). Psicoterapia y Cambio. Una Mirada desdela Subj<strong>et</strong>ividad. [Psychotherapy and Change. A View fromSubj<strong>et</strong>ivity] (1st ed.). Santiago de Chile: Ediciones UniversidadCatólica.Krause, M. (2011). Psicoterapia y Cambio. Una Mirada desdela Subj<strong>et</strong>ividad. [Psychotherapy and Change. A View fromSubj<strong>et</strong>ivity] (2nd ed.). Santiago de Chile: Ediciones UniversidadCatólica.Krause, M., Altimir, C., & Horvath, A. (2011). Deconstructingthe therapeutic <strong>al</strong>liance: Reflections on the underlying dimensionsof the concept. Clínica y S<strong>al</strong>ud, 22(3), 267–28<strong>3.</strong>Krause, M., V<strong>al</strong>dés, N., & Tomicic, A. (2010). TherapeuticActivity Coding System (TACS-1.0). Psychotherapy andChange Chilean Research Program. R<strong>et</strong>rieved from:http://www.psychotherapyandchange.orgKrause, M., de la Parra, G., Arístegui, R., <strong>Dagnino</strong>, P.,Tomicic, A., V<strong>al</strong>dés, N., ... & Ben-Dov, P. (2007). The evo-

86 The evolution of communicative intentionslution of therapeutic change studied through genericchange indicators. Psychotherapy Research, 17(6), 673–689.doi: 10.1080/10503300601158814Lepper, G. (2009). The pragmatics of therapeutic interaction:An empiric<strong>al</strong> study. Internation<strong>al</strong> Journ<strong>al</strong> of Psychoan<strong>al</strong>ysis,90(5), 1075–1094. doi:10.1111/j.1745-8315.2009.00191Mahrer, A. R., Nadler, W. P., St<strong>al</strong>ikas, A., Schachter, H. M., &Sterner, I. (1988). Common and distinctive therapeuticchange processes in client-centered, ration<strong>al</strong>-emotive, andexperienti<strong>al</strong> psychotherapies. Psychologic<strong>al</strong> Reports, 62(3),972–974. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1988.62.<strong>3.</strong>972Marmar, C. R. (1990). Psychotherapy process research: Progress,dilemmas, and future directions. Journ<strong>al</strong> of Consultingand Clinic<strong>al</strong> Psychology, 58(3), 265–272. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.58.<strong>3.</strong>265Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of th<strong>et</strong>herapeutic <strong>al</strong>liance with outcome and other variables: A m<strong>et</strong>a-an<strong>al</strong>yticreview. Journ<strong>al</strong> of Consulting and Clinic<strong>al</strong> Psychology,68(3), 438–450. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.<strong>3.</strong>438Mergenth<strong>al</strong>er, E. (1985). Textbank systems. Computer scienceapplied in the field of psychoan<strong>al</strong>ysis. Heidelberg: Springer.Mergenth<strong>al</strong>er, E. (1998). Cycles of emotion-abstraction patterns:A way of practice oriented process research? TheBritish Psychologic<strong>al</strong> Soci<strong>et</strong>y, Psychotherapy Section Newsl<strong>et</strong>ter,24, 16–29.Peng, C-Y. J., Lee, K. L., & Ingersoll, G. M. (2002). An introductionto logistic regression an<strong>al</strong>ysis and reporting. TheJourn<strong>al</strong> of Education<strong>al</strong> Research, 96(1), 3–14. doi:10.1080/00220670209598786Reyes, L., Arístegui, R., Krause, M., Strasser, K., Tomicic, A.,V<strong>al</strong>dés, N., … & Ben-Dov, P. (2008). Language and therapeuticchange: A speech acts an<strong>al</strong>ysis. Psychotherapy Research,18, 8–1<strong>3.</strong> doi:10.1080/10503300701576360Rice, L., & Greenberg, L. (1984). Patterns of change. NewYork: Guilford.S<strong>al</strong>vatore, S., Gelo, O., Gennaro, A., Manzo, S., & Al-Radaideh, A. (2010). Looking at psychotherapy as an intersubjectivedynamic of sensemaking. A case study with DiscourseFlow An<strong>al</strong>ysis. Journ<strong>al</strong> of Constructivist Psychology,23,195–230.Stiles, W. B. (1992). Describing T<strong>al</strong>k: A taxonomy of verb<strong>al</strong>response modes. SAGE Series in Interperson<strong>al</strong> Communication.SAGE Publications.Stiles, W. B., Shapiro, D. A., & Firth-Cozens, J. A. (1990).Correlations of session ev<strong>al</strong>uations with treatment outcome.British Journ<strong>al</strong> of Clinic<strong>al</strong> Psychology, 29(1), 13–21.doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1990.tb00844.xTrijsburg, R. W., Frederiks, G. C. F. J., Gorlee, M., Klouwer,E., Hollander, A. M., & Duivenvoorden, H. J. (2002). Developmentof the comprehensive psychotherapeutic interventionsrating sc<strong>al</strong>e (CPIRS). Psychotherapy Research, 12,287–317. doi:10.1093/ptr/12.<strong>3.</strong>287V<strong>al</strong>dés, N., Tomicic, A., Pérez, J. C., & Krause, M. (2010).Sistema de Codificación de la Actividad Terapéutica (SCAT-1.0): Dimensiones y categorías de las accionescomunicacion<strong>al</strong>es de pacientes y psicoterapeutas [TherapeuticActivity Coding System (TACS-1.0): Dimensions andCategories of Clients’ and Psychotherapists’ CommunicativeActions]. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 19, 117–129.R<strong>et</strong>rieved from: http://www.clinicapsicologica.org.ar/V<strong>al</strong>dés, N., Krause, M., & Álamo, N. (2011). ¿Qué Dicen yCómo lo Dicen?: Análisis de la comunicación verb<strong>al</strong> depacientes y terapeutas en episodios de cambio [What dothey say and how do they say it? An<strong>al</strong>ysis of patients’ andtherapists’ verb<strong>al</strong> communication in change episodes].Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 20, 15–28.R<strong>et</strong>rieved from: http://www.clinicapsicologica.org.ar/Watzke, B., Koch, U., & Schulz, H. (2006). Zur theor<strong>et</strong>ischenund empirischen Unterschiedlichkeit von therapeutischenInterventionen, Inh<strong>al</strong>ten und Stilen in psychoan<strong>al</strong>ytischund verh<strong>al</strong>tenstherapeutisch begründ<strong>et</strong>en Psychotherapien[About theor<strong>et</strong>ic<strong>al</strong> and empiric<strong>al</strong> differences in therapeuticinterventions, contents and styles, in psychoan<strong>al</strong>ytic<strong>al</strong> andbehavior<strong>al</strong> grounded psychotherapies]. Psychotherapie PsychosomatikMedizinische Psychologie, 56(6), 234–248.Received July 10, 2012Revision received November 25, 2012Accepted December 28, 2012