Banking for the future: - Third World Network

Banking for the future: - Third World Network

Banking for the future: - Third World Network

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

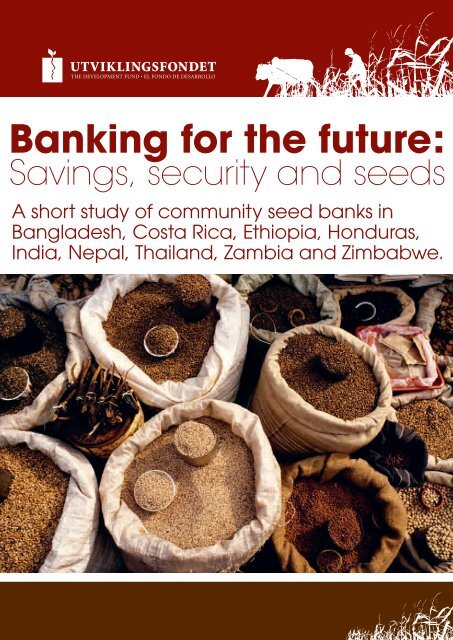

Published by The Development Fund/ UtviklingsfondetAll rights reserved The Development Fund/ Utviklingsfondet, NorwayFirst published 2011Readers are encouraged to make use of, reproduce, disseminate and translate material from thispublication with acknowledgement of this publication.For more in<strong>for</strong>mation please contactThe Development Fund/ UtviklingsfondetGrensen 9BN- 0159 OsloNorway+47 23 10 96 00www.utviklingsfondet.nopost@utviklingsfondet.noContributors at <strong>the</strong> Development Fund: Andrew P. Kroglund, Annette Wilhelmsen, Bell BattaTorheim, Kristin Ulsrud, Pitambar Shresta, Rosalba Ortiz, Sigurd Jorde and Teshome HundumaMulesa.Acknowledgement: First of all, thanks to all working with community seed banks on a daily basisand <strong>for</strong> sharing <strong>the</strong>ir experiences with us! Thanks to Nicha Rakpanichmanee (Thailand), GirmaG. Medhin (Ethiopia), Be<strong>the</strong>l Nakaponda (Zambia), Eduardo Aquilar-Espinoza (Costa Rica),Deepak Kumar Rijal (Nepal), C. K. Saha (Bangladesh), K.Siva Prasad (India) and Vivian VictoriaChristiaens (Zimbabwe) <strong>for</strong> documenting <strong>the</strong> experiences of community seed banks in differentcountries and <strong>the</strong>reby providing essential material <strong>for</strong> this report. A warm thanks to RegassaFeysissa and Melaku Worede <strong>for</strong> proving valuable background in<strong>for</strong>mation on community seedsbanks. Regine Andersen and Tone Winge have kindly written a chapter on linking community seedbanks to Farmers’ Rights <strong>for</strong> this report. Despite short notice, Andrew Mushita, Charles Nkhoma,Fredrik Fredriksen, Neth Dano, Trygve Berg and Vanaja Ramprasad have provided valuablefeedback on parts of <strong>the</strong> report.The Development Fund is a Norwegian independent non-governmental organisation (NGO).Our global programme on agricultural biodiversity supports local partners in <strong>the</strong> Global South incommunity based management of crop genetic diversity. Work at <strong>the</strong> field level is complementedby advocacy and in<strong>for</strong>mation work at <strong>the</strong> national and international levels. The programme issupported by NORAD.Layout: Åsmund GravemTrykk: GrøsetCover photo: Seeds of pulses at <strong>the</strong> market, Burma Photo: Jean-Leo DugastBack cover photo: Woman dries melon seeds in Kigbara-Dere, Nigeria. Photo: George Osodi2

5Community seed bank in India. Photo: Green Foundationyield increase. Besides, modern varieties are genetically distinctfrom each o<strong>the</strong>r, uni<strong>for</strong>m and stable (i.e. <strong>the</strong>y fulfil <strong>the</strong> so calledDUS criteria of <strong>for</strong>mal breeding: distinct, uni<strong>for</strong>m and stable).Chapter II: Linking community seedbanks and Farmers’ RightsRegine Andersen 5 and Tone Winge 6Basically, realising Farmers’ Rights means enabling farmersto maintain and develop <strong>the</strong>ir crop genetic resources as <strong>the</strong>yhave done since <strong>the</strong> dawn of agriculture and recognising andrewarding <strong>the</strong>m <strong>for</strong> this indispensable contribution to <strong>the</strong>global pool of genetic resources. The realisation of Farmers’Rights is a precondition <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> maintenance of crop geneticdiversity, which is <strong>the</strong> basis of all food and agriculturalproduction in <strong>the</strong> world. Since farmers are <strong>the</strong> custodians anddevelopers of crop genetic resources in <strong>the</strong> field, <strong>the</strong>ir rights inthis regard are crucial <strong>for</strong> enabling <strong>the</strong>m to continue this role.For this reason, Farmers’ Rights constitute a cornerstone in<strong>the</strong> International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources <strong>for</strong> Foodand Agriculture, or <strong>the</strong> Plant Treaty. This treaty aims at <strong>the</strong>conservation and sustainable use of crop genetic resources,5 Dr. Regine Andersen is senior research fellow at <strong>the</strong> Fridtjof Nansen Institute anddirector of <strong>the</strong> Farmers’ Rights Project (www.farmersrights.org).6 Tone Winge is research fellow at <strong>the</strong> Fridtjof Nansen Institute, working <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>Farmers’ Rights Project.<strong>the</strong>ir accessibility, and <strong>the</strong> sharing of benefits arising from<strong>the</strong>ir use.Parties to <strong>the</strong> Plant Treaty recognise <strong>the</strong> enormouscontributions that farmers have made, and will continue tomake, in conserving and developing plant genetic diversity,and in making this diversity available. According to <strong>the</strong> PlantTreaty, <strong>the</strong> responsibility <strong>for</strong> realising Farmers’ Rights restswith <strong>the</strong> national governments. The governments are free tochoose measures according to <strong>the</strong>ir own needs and priorities.Measures suggested in <strong>the</strong> Plant Treaty include protectingand promoting traditional knowledge relevant to cropgenetic resources, enabling farmers to participate equitablyin <strong>the</strong> sharing of benefits arising from <strong>the</strong> utilisation of suchresources, as well as in national decision making on relatedmatters. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, <strong>the</strong> treaty addresses <strong>the</strong> rights thatfarmers have to save, use, exchange and sell farm-saved seedand propagating material. We will have a closer look at <strong>the</strong>secomponents of Farmers’ Rights.Components of Farmers’ RightsProtecting traditional knowledge first and <strong>for</strong>emost meanstaking measures to halt this knowledge from disappearing.This can be done by collecting and documenting <strong>the</strong>remaining knowledge, sharing it to ensure continued use,teaching it to <strong>the</strong> younger generations, and encouraging itsuse. In some countries, stakeholders are concerned aboutprotecting traditional knowledge from misappropriation.There are several examples of how this can be done while at<strong>the</strong> same time ensuring that <strong>the</strong> knowledge can be shared, <strong>for</strong>example in <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m of catalogues.

7Chapter III: Making a case oflocal experiencesCommunity seed banks have been set up in many countries.Here is a short visit to some in Bangladesh, Costa Rica,Ethiopia, Honduras, India, Nepal, Thailand, Zambia andZimbabwe.Sustainable agriculture secures Bangladesh’sseed <strong>future</strong>The <strong>for</strong>mal seed system only covers about 20% of <strong>the</strong> seedrequirements in Bangladesh. 8 The rest has to be covered by<strong>the</strong> in<strong>for</strong>mal seed system, which is challenged by floods andcyclones that destroy crops. The private research organisationUBINIG established a community seed wealth centre toaddress <strong>the</strong> problem of loss of crop genetic diversity andsecure farmers’ access to locally adapted seeds. Locally,UBINIG works with <strong>the</strong> movement Nayakrishi Andolon (NewAgricultural Movement of Bangladesh). Their philosophycalls <strong>for</strong> changes in life style by practicing biodiversity-basedecological agriculture with no use of pesticides, minimaluse of chemical fertilisers and careful use of ground water.UBINIG has set up several seed huts, which in principlefunctions as community seed banks.According to Nayakrishi Andolon, seed conservation is anart belonging to women. Women’s Seed <strong>Network</strong>s are bodiesof autodidact and experienced women who provide technicalcapacity building to <strong>the</strong> community, give in<strong>for</strong>mation to <strong>the</strong>seed wealth centre and take part in meetings. Both <strong>the</strong> centreitself and <strong>the</strong> management committee in each seed hut are runby women.The seed network of 3000 farmers in <strong>the</strong> districts whereNayakrishi Andolon operates emphasises indigenouspractices of seed maintenance. UBINIG has no mid or longterm seed conservation system. The seeds are stored <strong>for</strong>limited periods in <strong>the</strong> houses of farmers, in <strong>the</strong>ir seed huts orat <strong>the</strong> seed wealth centre. Thus, UBINIG has to regenerate itsseeds every year.Any member of <strong>the</strong> movement can collect seeds from <strong>the</strong>seed huts if <strong>the</strong>y promise to deposit double <strong>the</strong> quantity <strong>the</strong>yreceived when <strong>the</strong> harvest is finished. The seeds are sold too<strong>the</strong>r farmers of <strong>the</strong> village, and <strong>the</strong> cost of <strong>the</strong> seed huts ismaintained from <strong>the</strong> income. All varieties are registered anda database of varieties is being maintained at each seed wealthcentre and also centrally at UBINIG.Management among farmers is based on collective decisionsand in<strong>for</strong>mation sharing. This is to ensure that, in everyplanting season, all available varieties at farmer’s householdsare planted and seeds collected and conserved <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> nextseason. Diversity is always encouraged as long as it does notbecome an economic stress on <strong>the</strong> farmer. Seed exchangeis encouraged and this is mainly done through <strong>the</strong> women’sseeds. The relation between Bangladesh’s National Gene Bankand <strong>the</strong> community seed wealth centre is just starting to beexamined. UBINIG has received 1500 rice varieties from <strong>the</strong>Bangladesh Research Institute which are now maintained in<strong>the</strong> community seed wealth centres. In addition, NayakrishiAndolon sometimes receives technical support from, andcollaborates with public research institutions.Farmers as seed producers in Costa RicaMany farmers in Costa Rica are organised in associationsof producers. These units provide <strong>the</strong>ir members with anintegral agricultural package and help <strong>the</strong>m improve <strong>the</strong>irincome through multiplication of seeds. Both <strong>the</strong> collectionof local seeds and <strong>the</strong> multiplication process in farmer’s fieldsare done by researchers in close collaboration with seedcommittees consisting of farmers. In addition, <strong>the</strong> NationalInstitute of Innovation and Agrarian Technology Transfertransfers materials and in some cases <strong>the</strong> National ProducersCommission (CNP) reproduces seed.The local materials collected are stored, developed andvalidated in research stations by scientists and farmers, basedon seed committees’ records of what materials are used andwhere <strong>the</strong>y come from. Committees are also responsible <strong>for</strong>choosing breeding strategies. At present, striving <strong>for</strong> higheryields to satisfy <strong>the</strong> demands of <strong>the</strong> market has a higherpriority than keeping diversity in farmers’ field.The national Costa Rican partner in <strong>the</strong> regional ParticipatoryPlant Breeding Programme in Mesoamerica (PPB-MA)purchased a cold chamber at <strong>the</strong> end of 2008 that willfunction as a community seed bank <strong>for</strong> all <strong>the</strong> neighbouringproducers’ associations . But as of February 2011, <strong>the</strong>community seed bank is still not fully operational, due tolack of funds. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, opinion varies among farmersas to which seeds should go into <strong>the</strong> community seed bank,how this bank should be organised and what role shouldbe assigned to <strong>the</strong> seed committees. Overall, conservationof seeds is at an early stage, since <strong>the</strong> main focus of <strong>the</strong>associations is to reproduce seeds <strong>for</strong> marketing.8 C. K. Saha (2009): “Case Study Report on Community Based Management ofCommunity Seed Wealth Center”, Development Fund

81 23

9Bringing traditional varieties back to farmersin EthiopiaEthiopia is regarded as a secondary centre <strong>for</strong> durum wheatdiversity. This diversity has been endangered due to <strong>the</strong>introduction of modern varieties of wheat, as well as byrepeated droughts and unprecedented food crises in <strong>the</strong>1970s and 1980s. To counter this development, researchersfrom <strong>the</strong> national gene bank at <strong>the</strong> Institute of BiodiversityConservation (IBC) collected traditional varieties of durumwheat from different agro-ecological zones. In addition tothis ex situ conservation, twelve community seed banks wereconstructed in six different districts from 1994 to 2002 9 .The community seed banks aims at contributing to asustainable conservation strategy and supporting seedexchange of traditional varieties among farmers. Banks aremanaged by <strong>the</strong> local farmers, who use <strong>the</strong>m to exchangeseeds of traditional varieties from diverse crops, such aswheat, teff, barely, lentil, beans and chickpeas. Havingregistered in crop conservation associations, farmers borrowand return seeds from <strong>the</strong> community seed banks. As intereston <strong>the</strong>ir seed loan, <strong>the</strong>y are obliged to return more seeds than<strong>the</strong>y initially received, <strong>the</strong>reby helping to increase <strong>the</strong> banks’seed stock.One of <strong>the</strong> twelve seed banks is <strong>the</strong> Ejere Community SeedBank, situated in <strong>the</strong> central highlands of Ethiopia. Since 2001it has been managed by an NGO called Ethio-Organic SeedAssociation (EOSA) in collaboration with <strong>the</strong> IBC.Through community seed banks, farmers’ varieties that hadbeen lost on farms were brought back from <strong>the</strong> national genebank at IBC. At <strong>the</strong> same time, samples of <strong>the</strong> remainingdiversity in farmers’ field were collected. Now, <strong>the</strong> communityseed bank in Ejere maintains about 90 accessions of durumwheat out of which 50 are under screening. Each year, <strong>the</strong>IBC undertakes renewal of this collection. EOSA, on itspart, works to increase <strong>the</strong> interest of <strong>the</strong> private sector inagricultural products of traditional varieties <strong>for</strong> processingand trade. EOSA also provides training and direct technicalsupport <strong>for</strong> farmers.“People considered it a miracle whentraditional varieties were brought backto <strong>the</strong>ir door steps after having beenconsidered lost completely.”Tadesse Reta (45), farmer and memberof Ejere Community Seed BankSaving seeds in Honduras: relief when <strong>the</strong>wea<strong>the</strong>r hitsIn Honduras, as in most of <strong>the</strong> world, <strong>the</strong> commercial seedsystem is generally not designed with <strong>the</strong> interests of smallscalefarmers in mind. The Honduran NGO Foundation <strong>for</strong>Participatory Research with Honduran Farmers (FIPAH)helps farmers organise community-wide research teamsknown as Comités de Investigación Local (CIALs). Thesefarmer research teams identify <strong>the</strong> most pressing localagricultural problems and find solutions, one of which is<strong>the</strong> establishment of community seed banks. Here bothtraditional varieties and varieties improved throughparticipatory plant breeding are stored.Several CIALs have set up community seed banks to ensurethat <strong>the</strong> poorest farmers always have access to quality plantmaterials. This helps to ensure that communities have a stablesupply of food. In 2000, FIPHA assisted <strong>the</strong> establishmentof one seed bank in <strong>the</strong> community of Santa Cruz in Yoritoin Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Honduras. Initially, <strong>the</strong> community seed bankfocused on rescuing traditional varieties in <strong>the</strong> area. Afterreceiving training, <strong>the</strong> community also started to provideseeds to its members.During <strong>the</strong> flooding caused by a tropical storm in 2008,farmers in Yorito lost approximately 90 present of <strong>the</strong>irmaize and bean harvest. The stocked seeds in <strong>the</strong> bank wereimmediately distributed to farmers and all farmers attached to<strong>the</strong> community seed bank managed to plant again when <strong>the</strong>storm stopped. The response was effective and no o<strong>the</strong>r reliefservice came so quickly and directly to <strong>the</strong> farmers rescue.According to <strong>for</strong>mer, local CIAL leader, <strong>the</strong> late Don LuisAlonso, <strong>the</strong> inhabitants of Yorito were saved by its communityseed bank. “After <strong>the</strong> flood, we distributed seeds to ourmembers and o<strong>the</strong>r farmers in <strong>the</strong> community. Thus, we areless dependent on support from outside,” said Alonso. Thiscontrasts with <strong>the</strong> situation in 1997, when hurricane Mitch hit<strong>the</strong> country. Then farmers had to receive seeds from outsidewithout being familiar with <strong>the</strong>ir quality or characteristics.“Local varieties of wheat have lowproductivity, but give us considerablesecurity since <strong>the</strong>y withstand extremeand unfavourable climatic conditionsand are less demanding in terms ofmanagement and input requirement.Their food preparation qualities aresuperior and highly demanded <strong>for</strong>specialty products such as local beerproduction. Productivity of localvarieties, particularly in durum wheat,needs to be improved.“Getachew Admassu (52), farmer and memberof Ejere Community Seed Bank9 Severin Polreich (et al.) (2005): ”Assessing <strong>the</strong> Effectiveness of <strong>the</strong> CommunitybasedSeed Supply System <strong>for</strong> in Situ Conservation of Local Wheat Varieties”, paperpresented at <strong>the</strong> Conference on International Agricultural Research <strong>for</strong> Development,Stuttgart-Hohenheim, October 11-13, 2005Images opposite side:1. Community seed bank in Rampur Dang, Nepal. Traditional seedstorage structure made of bamboo <strong>for</strong> storing tubers. Photo: LI-BIRD.2. Rice management in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Thailand. Photo: CBDC-Nan.3. Visitors learning from diversity block established by <strong>the</strong> communityseed bank of Kachorwa in Nepal. Photo: LI-BIRD

10Meeting poor farmers’ needs in IndiaIn India, resource poor farmers face <strong>the</strong> dilemma of procuringexpensive modern seeds with potentially higher yields orkeeping traditional varieties that are less vulnerable to pestand disease and better adapted to varying climatic conditions.If <strong>the</strong> crop is lost, it is difficult <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong>m to pay back <strong>the</strong> loansoften obtained when buying modern varieties. Trying toimprove this situation, <strong>the</strong> NGO Green Foundation focuseson streng<strong>the</strong>ning community based biodiversity conservation.Their aim is to protect <strong>the</strong> ecology and encourage <strong>the</strong> smalland marginal farmers to adopt sustainable agriculturalpractices. Among o<strong>the</strong>r things, Green Foundation motivatedmembers of local Krushi self-help groups to establishcommunity seed banks in a selected cluster of villages.Each community seed bank has members from four to sevenneighbouring villages. Self-help group members who areinterested in conservation take active part in managing <strong>the</strong>seed banks. Green Foundation, on its part, trains farmersin seed selection, storage by traditional methods and recordkeeping and manages disbursals of seeds. Farmers receiveseeds from <strong>the</strong> bank in return <strong>for</strong> double <strong>the</strong> quantity after<strong>the</strong> harvest. In times of crop failure, farmers compensate witho<strong>the</strong>r varieties which <strong>the</strong>y hold and return <strong>the</strong> seed <strong>the</strong> nextseason.1Community sharing of in<strong>for</strong>mation on seed varieties, storingcapacity, germination, crop yields and disease resistanceare crucial to enhance local knowledge of seed production.Female members are showing particular deep interestin saving and exchanging seeds, as well as in practicingtraditional pest control measures. At present, GreenFoundation facilitates nine functioning community seedbanks in <strong>the</strong> district of Ramanagaram in South India, eachproviding 70-80 farmers with seeds every season. Farmerscontribute to conservation of <strong>the</strong> traditional varieties byincreasing <strong>the</strong> area under which <strong>the</strong> traditional varieties aregrown.Green Foundation also has a back-up gene bank in case aparticular variety of seed is lost. The seeds are grown outseasonally and field days are organised to show <strong>the</strong> diversitywithin <strong>the</strong> gene bank. Researchers from <strong>the</strong> agricultureuniversity and extension department are invited to <strong>the</strong> fielddays, where <strong>the</strong>y share <strong>the</strong>ir expertise.Increasing farmers’ income in NepalAs part of a global on-farm crop conservation project inNepal, community seed banks have been established by <strong>the</strong>Nepal Agriculture Research Council and <strong>the</strong> NGO LocalInitiatives <strong>for</strong> Biodiversity, Research and Development (LI-BIRD). The community seed bank in itself is managed byAgriculture Development Community Society (ADCS), afarmers’ organisation.The seed bank deals with a variety of local seeds as well asimproved varieties. In addition, some rice varieties bred fromtraditional varieties with <strong>the</strong> technical assistance of LI-BIRDare included.In collaboration with partner organisations ADCS collects,regenerates, multiplies and promotes diversity on-farm.The diversity and knowledge ga<strong>the</strong>red through differenttechniques, such as diversity fairs, biodiversity registrationand diversity blocks, have improved farmers’ access to seedsof preferred varieties. To refresh seeds maintained in <strong>the</strong> seedbank and meet local demands, seeds of <strong>the</strong> crop varieties areregenerated each year.2

11The seed bank offers local people seeds of local origin aswell as preferred improved varieties, and it empowers <strong>the</strong>community with respect to conservation, use and marketing.Farmers and farmers groups frequently visit <strong>the</strong> seed bank<strong>for</strong> technical input, facilitation of saving and credit schemes,business advice and funding <strong>for</strong> small scale businesses. Thisstrongly suggests that ADCS is becoming a key institutionin <strong>the</strong> area. However, maintaining seed quality has been achallenge <strong>for</strong> ADCS, as it lacks quality control mechanismsand trained man power.The most important lesson learned from <strong>the</strong> project is thatmost crop varieties of local origin are maintained by wealthierhouseholds. Poorer farmers use those varieties, but are unableto invest resources <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> sake of conservation <strong>for</strong> <strong>future</strong>use. In this situation, <strong>the</strong> community seed bank can maintainvarieties preferred by small scale farmers, who often operatein marginal environments where local varieties are preferred.The seed access provided by community seed banks <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>edirectly improves <strong>the</strong> food security of small scale farmers.ADCS has also established a diversity fund, which hasbeen effective in raising <strong>the</strong> incomes of small scale farmers,including landless households. By accepting fund rules, thosewho borrow from <strong>the</strong> diversity fund agree to be responsible<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> regeneration of one traditional variety. The fundthus streng<strong>the</strong>ns small scale businesses and contributes toconservation of traditional varieties. Most of <strong>the</strong> diversityfund loan takers have been resource poor farmers or peoplefrom socially excluded and ethnic minorities.Involving high school students in ThailandIn 2000, a seed bank was established in <strong>the</strong> mountainousNan Province in North Western Thailand to solve commonproblems of insufficient seeds, poor seed quality and highproduction costs. The Thung Kong Community Seed Bankwas initiated by Pin Kamsaen and her relatives. In her late 40s,Pin was illiterate but enthusiastic about sharing her traditionalknowledge about seed saving and plant breeding. Staff from<strong>the</strong> NGO Joko Learning Centre recognised her qualities andgave Pin multiple training opportunities both locally andabroad.Thung Kong Community Seed Bank has successfullyintegrated its activities into <strong>the</strong> local high school curriculum.With active support from <strong>the</strong> school’s biology teacher, <strong>the</strong>community seed bank benefits from <strong>the</strong> weekly contributionin documentation and labour from Grade 11 students, as partof <strong>the</strong>ir science curriculum. Students help with planting andharvesting, as well as with recording properties of traditionalvarieties and new seeds. Some attend <strong>the</strong> Farmers’ FieldSchool on Saturdays during <strong>the</strong> growing season to learnadditional techniques.The establishment of Thung Kong community seed bank wenthand in hand with <strong>the</strong> establishment of Thung Kong Farmers’Field School, initiated by Joko Learning Centre. The schoolcurriculum is matched to each rice growing season and taughtin an actual field. The on-farm research itself is taken up byindividual farmers, notably Pin. With her rice field locatednext to <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>est, Pin often discovers new genetic materials.She cultivates <strong>the</strong>se varieties into seeds <strong>for</strong> propagation.Somkuan, treasurer at <strong>the</strong> community seed bank, breedsselected varieties that are put up <strong>for</strong> sale as foundation seedsto local buyers and o<strong>the</strong>r farmer networks.Thung Kong Community Seed Bank receives some seedsupplies from rice research scientists, from <strong>the</strong> governmentoffice in north-eastern Thailand and from universities in <strong>the</strong>nor<strong>the</strong>rn region. Joko Learning Centre’s technicians and ruraldevelopment workers provide support on pest managementand organic production techniques as well as advice onmanagement of community seed banks. The Thung KongCommunity Seed Bank also has a one-way relationship withfarmer-breeders in <strong>the</strong> region. Members collect new varietiesduring study trips. In return, <strong>the</strong> seed bank serves as aneducational model and initial seed supply <strong>for</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r farmergroups from across Thailand.Distributing modern varieties in ZambiaPoor farmers in rural Zambia face problems in accessinggood quality seed when <strong>the</strong>y need it. This has frequently ledto farmers doing <strong>the</strong>ir sowing late and consequently resultsin poor harvests. To meet <strong>the</strong>se challenges, <strong>the</strong> British/Irish NGO Self Help Africa is working with seed growerassociations in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn, Western and Eastern provinces ofZambia, where community seed banks have been established.However, like some seed companies, <strong>the</strong>se community seedbanks rely on seed bred by <strong>the</strong> Zambian Agriculture ResearchInstitute ra<strong>the</strong>r than promoting local crops and varieties.Thus, <strong>the</strong> community seed banks work as outlets of improvedvarieties.The trained members of <strong>the</strong> seed growers associationsparticipate in seed multiplication. Members have to pay afee and are <strong>the</strong>n allowed to buy shares in <strong>the</strong> association onwhich interest is paid whenever it makes money from bulkselling of modern varieties. However, seed companies andtraders take advantage of in<strong>for</strong>mal sector seed producers’ lackof a readily available market <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> seeds <strong>the</strong>y produce, and<strong>the</strong> insufficient training in marketing skills. Companies andtraders buy seeds from <strong>the</strong>m at very low prices, repack <strong>the</strong>same seeds with <strong>the</strong>ir logo on it and sell it at up to three orfour times <strong>the</strong> price.Images opposite side:1. Seeds bags in Ethiopia. Photo: Ashnan Films, Canada2. Farmers from Western part of Nepal visiting community seed bank atKachorwa Bara, Nepal. Photo: LI-BIRD

123

13There has been a general shift from using traditional varietiesbecause <strong>the</strong>y are late maturing and low yielding compared toimproved varieties. This shift has been compounded by <strong>the</strong>many programmes that promote modern varieties such as <strong>the</strong>Farmer Input Support programme, which provides subsidisedhybrid seed and fertilisers. Even <strong>the</strong> community seed banks of<strong>the</strong> seed growers associations tend to promote only <strong>the</strong> use ofimproved varieties.Seed fairs promote seed diversity in ZimbabweIn 1991/1992 a severe drought contributed to geneticerosion in Zimbabwe’s agriculture. As a response, <strong>the</strong> NGOCommunity Technology Development Trust (CTDT)set up community seed banks in close consultation withcommunities. These were to provide back-up facilities <strong>for</strong>farmers’ varieties, capture traditional knowledge and enablefarmers’ access to local seeds of reasonable quality.One such bank is The Uzumba Maramba PfungweCommunity Seed Bank, established in 1998. It is locatedin a semi-arid area and serves four different administrativeareas. There are two rooms in <strong>the</strong> building constructed tobe relatively cool, maintaining a temperature ideal <strong>for</strong> seedstorage. Seeds brought to <strong>the</strong> bank undergo a thoroughcleaning process, to rid <strong>the</strong> seeds of pests and diseases.Germination tests are conducted every two years to assessseed viability. Seeds with low germination percentages areregenerated.The Uzumba Maramba Pfungwe Community Seed Bank ismanaged by farmers. The community elects a managementcommittee responsible <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> coordination and managementof all activities. Both CTDT and <strong>the</strong> government’s agriculturalextension services provide technical assistance and capacitybuilding to farmers. The National Gene Bank also collaboratesby providing materials and seeds to <strong>the</strong> bank as well astechnical management.Collection and cleaning of seeds are done by individualhouseholds and farmers who have been capacitated in seedhandling. Because of socio-economic and cultural normsand values, women play an important role in communalfarming and are <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e largely contributing through seedselection in <strong>the</strong> fields, cleaning and bringing seeds to <strong>the</strong>community seed bank as well as participating at seed fairs.Youth participation is minimal; only a few are engaged inconservation bring <strong>the</strong>ir seeds to <strong>the</strong> bank. Many youngpeople are not interested in farming and many have moved tocities looking <strong>for</strong> employment.The community seed bank functions as a meeting place <strong>for</strong>farmers to exchange in<strong>for</strong>mation and local knowledge on cropgenetic diversity. In order to increase awareness, seed fairsare conducted at <strong>the</strong> community seed bank every year andat national level biannually. These fairs provide an additionalmeeting <strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> farmers. They also enable communitiesto evaluate <strong>the</strong> level of diversity and to assess and monitorgenetic erosion.Chapter IV: Arguing <strong>the</strong> case <strong>for</strong>community seed banksAs can be seen from <strong>the</strong> previous chapter, different <strong>for</strong>ms ofcommunity seed banking practices are being promoted indifferent countries. Some are highly specialised in collection,regeneration, distribution and maintenance of local cropdiversity and documentation of associated in<strong>for</strong>mation andtraditional knowledge. O<strong>the</strong>rs are engaged in production andmarketing of seeds of improved farmers’ varieties. The presentchapter sums up <strong>the</strong> lessons learned from <strong>the</strong> cases examinedand presents some current and <strong>future</strong> challenges.Why are community seed banks established?Most community seed banks in <strong>the</strong> presented case countrieshave been established to combat seed insecurity. Suchinsecurity is mainly due to drought causing crop failure(e.g. in Ethiopia and Zambia), flood and cyclones (e.g. inBangladesh) and introduction of modern varieties andpolicies promoting it through subsidies or by o<strong>the</strong>r means(e.g. in India, Nepal, Thailand, and Zimbabwe). Modernvarieties are increasingly replacing traditional ones. They areexpensive <strong>for</strong> small scale farmers and hence inaccessible. Inaddition, in <strong>the</strong> cases examined, introduced modern varietieshave not met local needs and thus have failed to adapt. Thisfailure is particularly evident in <strong>the</strong> case of irrigated andpaddy rice growing areas in India, Nepal and Thailand, aswell as in growing areas <strong>for</strong> maize in Zimbabwe and maizeand beans in Honduras. In <strong>the</strong> case of Zambia, focus ontraditional varieties is almost non-existent. Here, communityseed banks mainly provide improved varieties; <strong>the</strong> issue ofconservation is not taken into consideration in bank practiceand management.In some countries (e.g. Costa Rica) <strong>the</strong> motivation behind<strong>the</strong> seed bank is <strong>for</strong> marketing high quality seeds of improvedfarmers’ varieties and modern varieties at community level.This differs from <strong>the</strong> “traditional” goals of community seedbanks: addressing <strong>the</strong> challenges of seed insecurity in timesof shortage and human and nature induced calamities, inaddition to on-farm conservation of crop genetic diversity.Who are involved?Farmers are <strong>the</strong> primary stakeholders in <strong>the</strong> community seedbanks approach <strong>for</strong> management of agricultural biodiversity.Their knowledge of agro ecosystems, crops and varieties, havebeen central in <strong>the</strong> management of community seed banks.Farmers have elected committees to manage <strong>the</strong> seed banks(e.g. in Ethiopia), while in Costa Rica and Zambia farmerswere organised in seed producing associations.Images opposite side:1. Seeds at display in India. Photo: Green Foundation.2. Seed storage in India. Photo: Green Foundation.3. Traditional storing of rice seeds, taro cormel and potato tubers incommunity seed bank in Gadariya, Nepal. Photo: LI-BIRD

15All community seed banks in <strong>the</strong> case studies were initiatedor supported by NGOs. The NGOs played a useful rolein organising and training farmers in collaboration withdifferent national institutions. However, high reliance onNGOs is a challenge <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> sustainability of communityseed banks. This challenge seems to have been overcomein Nepal, where farmers managing community seed bankshave established a community biodiversity managementfund, which is being used <strong>for</strong> conservation and developmentof plant genetic resources and improving livelihoods of <strong>the</strong>target group. Generally, community seed banks in many caseshave remained innovative demonstration examples. Theyhave not received <strong>the</strong> institutional support required <strong>for</strong> ascaling-up that would make <strong>the</strong>m part of larger strategies <strong>for</strong>conserving crop genetic diversity.In some cases, national gene banks have served as a source ofdiversity in varieties <strong>for</strong> farmers managing community seedbanks. In some of <strong>the</strong> examined cases, gene banks restoredlost varieties to certain areas through farmers (Ethiopia).In Zimbabwe, <strong>the</strong> national gene bank works in closecollaboration with <strong>the</strong> community seed bank by providingmaterials <strong>for</strong> restoration of local varieties. Here, <strong>the</strong> nationalgene bank also acts as a backup <strong>for</strong> varieties. However, inmost of <strong>the</strong> case countries <strong>the</strong>re is a loose connection betweengene banks and community seed banks, that is, between exsitu and on-farm conservation.Agricultural research institutions are involved in training offarmers in breeding, plant variety selection, seed productionand storage (e.g. in Nepal, Thailand and Costa Rica). Theyprovide farmers with pre-breeding materials <strong>for</strong> fur<strong>the</strong>rselection and seeds <strong>for</strong> multiplication. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore, researchinstitutions are interested in using organised farmers asoutlets <strong>for</strong> distributing <strong>the</strong>ir varieties and even multiplying<strong>the</strong>m (e.g. in Zambia).Sometimes governmental agricultural extension officescollaborated with community seed banks to promote modernvarieties (e.g. Zambia). On <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r hand, in Thailand andNepal, agricultural extension offices were used to promotefarmers’ varieties that were improved through ParticipatoryPlant Breeding and Participatory Variety Selection in additionto modern varieties from <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal sector. Thus, <strong>the</strong> role ofagricultural extension in management of crop genetic diversityvaries, depending on <strong>the</strong> activities of <strong>the</strong> community seedbanks.How do community seed banks work?The operational modalities of <strong>the</strong> community seed banksdiffer from country to country. In Ethiopia and Bangladesh,members of community seed banks access seeds on loanbasis. The approach in this case is similar to micro creditwhere seeds replace money. In <strong>the</strong>se cases, farmers are pleasedwith saving money on fertiliser that would be required if<strong>the</strong>y were planting modern varieties. Moreover, <strong>the</strong>y getaccess to <strong>the</strong> varieties <strong>the</strong>y appreciate and have knowledge of.The community seed banks are mostly managed by electedcommittees.Images opposite side:1. Seed sacks and germplasm reserve in Ejere community seed bank inEthiopia. Photo: EOSA2. Traditional seed storage structure made of bamboo and mud, Nepal.Photo: LI-BIRD3. Rice display in Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Thailand. Photo: CBDC-NanMost community seed banks reach out also to non-memberfarmers. For instance, farmers managing community seedbanks in Ethiopia, Nepal, India, Thailand and Zimbabwe areselling seeds to non-members. This implies that communityseed banks, in addition to conserving and enhancingtraditional varieties, can be trans<strong>for</strong>med into viable and selfsustainedseed business entities.The case from Zambia shows that participating communitieswere also engaged in multiplying seeds based on parent linesof a very limited number of varieties given to <strong>the</strong>m from<strong>the</strong> country’s breeding stations. They have also assisted withselling <strong>the</strong> multiplied seeds. The same documentation showsthat <strong>the</strong> Zambia Agricultural Research Institute has producedsome of <strong>the</strong> crop varieties <strong>for</strong> seed production by use of <strong>the</strong>community seed banks. However, <strong>the</strong>se variety developmentactivities did not fully involve farmers. Ef<strong>for</strong>ts were made tocollect local varieties <strong>for</strong> various crops under <strong>the</strong> communityseed banks programme in Zambia, but it did not manage todistribute seeds to members <strong>for</strong> reproduction. Fur<strong>the</strong>rmore,a seed company took advantage to peddle its varieties. Inthis case, <strong>the</strong> idea of community seed banks seems to bemisunderstood by implementers.Documented resultsFirst and <strong>for</strong>emost, community seed banks improve farmers’access to seeds. In most countries, <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal seed systemdoes not meet <strong>the</strong> needs of farmers ei<strong>the</strong>r in terms ofquantity (e.g. in Bangladesh, it constitutes only about 20 %)or quality with its narrow focus on modern varieties – or ata cost af<strong>for</strong>dable to poor farmers. Most of community seedbanks distribute to members and non-members alike. InIndia and Nepal, access to seeds <strong>for</strong> resource poor farmershas been given particular attention. In Honduras andBangladesh, community seed banks improved access toseeds after harvest loss. Due to <strong>the</strong> prioritising of modernvarieties by government programmes, farmers’ varieties arenot distributed in <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal seed system. Community seedbanks can <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be a tool <strong>for</strong> farmers to access traditionalvarieties (e.g. in Nepal, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, India andEthiopia), but also improved varieties. Thus, community seedbanks function as locally accessible ex situ conservation ofcrop genetic diversity.Traditional knowledge is documented and shared amongmembers of community seed banks. This is especially valuablein situations where <strong>the</strong> farmers’ varieties are disappearingbut <strong>the</strong> traditional knowledge can be used to promote itsrehabilitation. In Thailand, traditional knowledge is alsoreaching younger generations by being integrated in <strong>the</strong> highschool curriculum.Empowerment of farmers is an important outcome of <strong>the</strong>establishment of community seed banks. This indicates thatfarmers have got <strong>the</strong> necessary skill and knowledge in seedselection, breeding, seed production and role of diversity ofcrops and <strong>the</strong>ir varieties in farming. Community seed bankspromoted bulk selling of produce and allowed <strong>for</strong> its membersto be trained in local seed production and management.They also improved farming systems (e.g. in Thailand, CostaRica and Nepal). Through methods like Participatory Plant

16Breeding (PPB), Participatory Varietal Selection (PVS), croprotation and crop diversification, community seed bankinghelped increase productivity and household food security, andimproved nutrition. This kind of farming also demonstratessustainable agricultural practises.In economic terms, banking contributed to increaseddisposable income from <strong>the</strong> sale of surplus seed and produce<strong>for</strong> farmers’ groups. In Ethiopia and India, <strong>for</strong> instance, suchincome has been used to meet various household needs,including acquisition of assets and agriculture inputs, andstarting up small business enterprises. More generally, <strong>the</strong>affiliated farmers regard <strong>the</strong> seed multiplication throughcommunity seed banks as an opportunity to generate income(e.g. Zambia and Costa Rica). This is so because seed <strong>for</strong><strong>the</strong> next planting season can be stored in proper conditionsand still have good yields and germination. As an additionalbenefit, if a variety is not requested by <strong>the</strong> market its seed canbe saved <strong>for</strong> more advantageous market conditions. In fact,community seed bank projects are more likely to succeed ifseed marketing is included.Overall, <strong>the</strong> commitment of women in farmer groupsmanaging community seed banks outweighed that of men.Home garden fruits and vegetable varieties managed bywomen helped farmers understand <strong>the</strong> importance and valueof diverse seeds of vegetables required <strong>for</strong> different growingseasons (e.g. in India and Bangladesh). Female members ofcommunity seed banks are showing deep interest in savingand exchanging seeds <strong>for</strong> purposes like household nutritionand cultural uses of certain crops. Their knowledge of seedstorage, aptitude <strong>for</strong> nurturing with patience and ability tosave seeds <strong>for</strong> <strong>future</strong> seasons often make women better thanmen at managing seed banks. Female farmers practice severalpest control measures while saving seeds.Many farmers cultivate both modern and traditionalvarieties. They try commercial varieties without necessarilydiscarding <strong>the</strong>ir own. That’s when ideas of combining <strong>the</strong>better of <strong>the</strong> two worlds through participatory plant breedingcame up. If farmers grow ‘low-yielding’ farmers’ varieties,it is usually because those varieties are <strong>the</strong> best under localcircumstances or because of specific merits that are missingin <strong>the</strong> commercial ‘high-yielding’ varieties. If <strong>the</strong> communityseed bank networks involve <strong>the</strong>mselves in participatory plantbreeding <strong>the</strong>y would usually try to combine <strong>the</strong> high yieldpotential of commercial varieties with <strong>the</strong> attractive traits in<strong>the</strong>ir own local varieties.Challenge number one, however, is at a higher level thanwhat can be solved at community level alone: Governments’agricultural policies prioritise high yields throughintensification (increased use of modern varieties andintensification of agricultural inputs). Both research andgovernment extension services are focused on improvedvarieties in combination with chemical fertilisers andpesticides. Training and orientation of development/extension agents is also geared towards <strong>the</strong> implementationof accelerated productivity and growth strategies, withlittle or no relevance to <strong>the</strong> conservation and utilisationof local genetic diversity due to lack of understandingand appreciation. There is also <strong>the</strong> danger of creating <strong>the</strong>impression among farmers that <strong>the</strong>ir traditional varietiesare inferior and this may contribute to erosion of geneticresources and loss of related traditional knowledge.Farmers also want high yields, but high-yield technologypackages may be difficult to adopt <strong>for</strong> economic reasons, <strong>for</strong>lack of agro-ecological adaptation (<strong>the</strong>y do not fit farmersmarginal land), or <strong>for</strong> having o<strong>the</strong>r negative impacts likeharming <strong>the</strong> environment. Care should <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e be taken notto miss <strong>the</strong> target group (seed insecure poor farmers) and <strong>the</strong>banks’ “traditional” objectives of conservation.Today, countries lack legal frameworks and institutionalsupport to community seed banking. They also upholdrestrictive laws, such as seed certification based on <strong>the</strong> criteriain <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>mal seed system of distinct, uni<strong>for</strong>m and stable. Asa result, farmers cannot market branded seeds coming out of<strong>the</strong>ir ef<strong>for</strong>ts. This situation threatens <strong>the</strong> sustainability of <strong>the</strong>seed banking concept itself. Under current legal and policyregimes, it is hard <strong>for</strong> farmers through community seedbanking to combine modern and traditional seeds as <strong>the</strong>yprefer.In cases where traditional varieties are not so attractive <strong>for</strong>local farming communities any longer, it is not <strong>the</strong> soleresponsibility of farmers managing community seed banks toconserve <strong>the</strong>m. The next chapter looks at steps needed to betaken in order to up-scale community seed banks.ChallengesCommunity seed banks still face many challenges. Among<strong>the</strong>m are: lack of markets <strong>for</strong> farmers’ varieties; inadequatecapacity and knowledge in marketing seeds; inadequatestorage facilities; lack of manpower during peak seasons;insufficient seed quality; late distribution of seeds and latepayments <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> seeds loaned, as well as high dependenceon NGOs or a few dedicated farmers. The different farmingcommittees running <strong>the</strong> seed banks meet <strong>the</strong>se challenges indifferent ways.Images opposite side:1. Rice seeds, Nepal. Photo: LI-BIRD2. Conservation of traditional varieties, Ethiopia. Photo: EOSA3. Rice and finger millet seeds, Nepal. Photo: LI-BIRD4. Inside <strong>the</strong> community seed bank in Kachorwa, Bara, Nepal. Photo:LI-BIRD

1712 3 4

18Chapter V: Up-scaling communityseed banks to implement Farmers’Rights and towards a sustainable<strong>future</strong> <strong>for</strong> agricultureTo fully reap <strong>the</strong> benefits of community seed banks inenhancing farmers’ access and control of seeds, as well as <strong>the</strong>ircontribution to <strong>the</strong> conservation and sustainable use of cropgenetic diversity, we will end this report with a set of policyrecommendations.Governments should:ÁÁEstablish and/or support community seedbanks as part of <strong>the</strong>ir obligations to implementFarmers’ Rights and o<strong>the</strong>r provisions of <strong>the</strong>Plant Treaty, such as sustainable use andconservation of crop genetic diversity. Partiesshould support <strong>the</strong> up-scaling of communityseed banks in order to reach as many farmersas possible, especially in marginalised areas.12ÁÁIntegrate community seed banks in broaderprogrammes on agricultural biodiversity,where <strong>the</strong> local seed banks should serve as astoring place <strong>for</strong> results of participatory plantbreeding and participatory variety selection,and make such results accessible to farmers.Seed banks should also be venues <strong>for</strong> seedfairs <strong>for</strong> farmers to exchange and display <strong>the</strong>irseed diversity.ÁÁÁÁÁÁInclude community seed banks ingovernments’ agricultural developmentstrategies as a vehicle <strong>for</strong> adaptation toclimate variability. Agricultural extensionservices would provide <strong>the</strong> best institutionalinfrastructure to embark on a scaling up oflocal seed bank experiences to a nationallevel.Revise seed regulations and provisions onintellectual property rights to seeds to ensureFarmers’ Rights to save, use, exchange and sellfarm-saved seeds.Redirect public subsidies from promotingmodern varieties to fund <strong>the</strong> above mentionedactivities.1. Maize and bean seeds in Honduras. Photo: Development Fund2. Communuty seed bank in Rampur Dang, Nepal. Traditional seedstorage structure made of mud. Photo: LI-BIRD.

19Agricultural Research Institutions should:Commercial seed sector should:ÁÁÁÁÁÁEnsure that farmers are given an in<strong>for</strong>medchoice between traditional and modernvarieties. Extension services and governmentagricultural policies should be reviewed asto ensure this balance. There is a need todemocratise agricultural extension systemsso that it provides all kinds of in<strong>for</strong>mation (e.g.about <strong>the</strong> role of <strong>for</strong>mal and in<strong>for</strong>mal seedsystems) in a transparent way without puttingfarmers’ varieties to a disadvantage.Extend <strong>the</strong>ir expertise and services <strong>for</strong> free toassist and support communities and NGOs insetting up and maintaining community seedbanks. Their assistance and support should bebased on <strong>the</strong> actual needs and capacitiesof <strong>the</strong> communities and local organisationsseeking <strong>the</strong>ir expertise.Facilitate <strong>the</strong> access of communities andNGOs setting up community seed banks too<strong>the</strong>r in situ as well as ex situ sources of seeds,if necessary and when required. They shouldhelp provide linkages among communitiesengaged in community seed banking andrelevant institutions and organisations that maybe able to support such ef<strong>for</strong>ts. Communityseed banks are <strong>the</strong> bridge between in situ andex situ conservation. Through <strong>the</strong>m, nationalgene banks should make <strong>the</strong>ir acquisitionsavailable to farmers.ÁÁÁÁContribute to <strong>the</strong> Benefit Sharing Fund of <strong>the</strong>Plant Treaty, which in its turn should makesure that sufficient funds <strong>for</strong> supportingcommunity seed banks are in place. The costof conserving crop genetic diversity shouldnot be borne by resource poor farmers in <strong>the</strong>Global South, but be shared by all who benefitfrom <strong>the</strong> commercialisation of this diversity.Multiply and produce farmers’ varieties <strong>for</strong>increased availability of locally adaptedseeds.NGOs should:ÁÁÁÁAdopt a mechanism to share <strong>the</strong>ir skills andknowledge in establishing and maintainingcommunity seed banks to interestedcommunities, farmers’ organisations ando<strong>the</strong>r NGOs in and around <strong>the</strong> countrieswhere <strong>the</strong>y are based. The main role of NGOsis to promote community seed banks untilgovernments have incorporated such banks in<strong>the</strong>ir <strong>for</strong>mal systems like agricultural extensionservices.Streng<strong>the</strong>n community based managementof agricultural biodiversity and avoid usingcommunity seed banks <strong>for</strong> promoting onlymodern varieties.“All States should: Support and scale-up local seed exchange systems such as community seed banks andseed fairs, community registers of peasant varieties, and use <strong>the</strong>m as a tool to improve <strong>the</strong> situation of <strong>the</strong>most vulnerable groups,..”Mr Olivier De Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on <strong>the</strong> Right to Food, speakingat <strong>the</strong> 64th session of <strong>the</strong> UN General Assembly (October 2009)