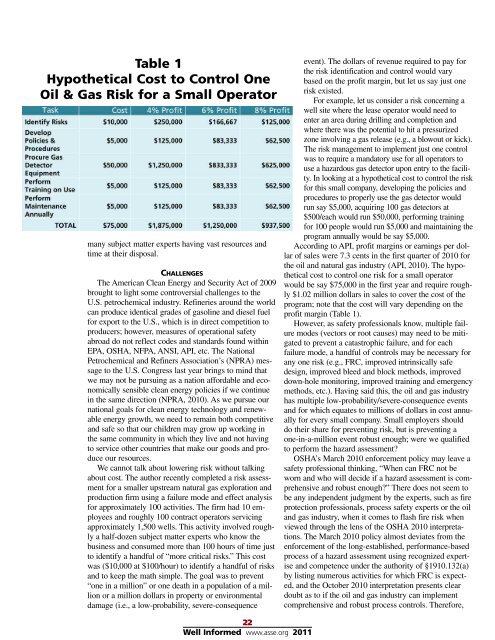

Table 1Hypothetical Cost to Control OneOil & Gas Risk for a Small Operatormany subject matter experts having vast resources andtime at their disposal.CHALLENGESThe American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009brought to light some controversial challenges to theU.S. petrochemical industry. Refineries around the worldcan produce identical grades of gasoline and diesel fuelfor export to the U.S., which is in direct competition toproducers; however, measures of operational safetyabroad do not reflect codes and standards found withinEPA, OSHA, NFPA, ANSI, API, etc. The NationalPetrochemical and Refiners Association’s (NPRA) messageto the U.S. Congress last year brings to mind thatwe may not be pursuing as a nation affordable and economicallysensible clean energy policies if we continuein the same direction (NPRA, 2010). As we pursue ournational goals for clean energy technology and renewableenergy growth, we need to remain both competitiveand safe so that our children may grow up working inthe same community in which they live and not havingto service other countries that make our goods and produceour resources.We cannot talk about lowering risk without talkingabout cost. The author recently completed a risk assessmentfor a smaller upstream natural gas exploration andproduction firm using a failure mode and effect analysisfor approximately 100 activities. The firm had 10 employeesand roughly 100 contract operators servicingapproximately 1,500 wells. This activity involved roughlya half-dozen subject matter experts who know thebusiness and consumed more than 100 hours of time justto identify a handful of “more critical risks.” This costwas ($10,000 at $100/hour) to identify a handful of risksand to keep the math simple. The goal was to prevent“one in a million” or one death in a population of a millionor a million dollars in property or environmentaldamage (i.e., a low-probability, severe-consequenceevent). The dollars of revenue required to pay forthe risk identification and control would varybased on the profit margin, but let us say just onerisk existed.For example, let us consider a risk concerning awell site where the lease operator would need toenter an area during drilling and completion andwhere there was the potential to hit a pressurizedzone involving a gas release (e.g., a blowout or kick).The risk management to implement just one controlwas to require a mandatory use for all operators touse a hazardous gas detector upon entry to the facility.In looking at a hypothetical cost to control the riskfor this small company, developing the policies andprocedures to properly use the gas detector wouldrun say $5,000, acquiring 100 gas detectors at$500/each would run $50,000, performing trainingfor 100 people would run $5,000 and maintaining theprogram annually would be say $5,000.According to API, profit margins or earnings per dollarof sales were 7.3 cents in the first quarter of 2010 forthe oil and natural gas industry (API, 2010). The hypotheticalcost to control one risk for a small operatorwould be say $75,000 in the first year and require roughly$1.02 million dollars in sales to cover the cost of theprogram; note that the cost will vary depending on theprofit margin (Table 1).However, as safety professionals know, multiple failuremodes (vectors or root causes) may need to be mitigatedto prevent a catastrophic failure, and for eachfailure mode, a handful of controls may be necessary forany one risk (e.g., FRC, improved intrinsically safedesign, improved bleed and block methods, improveddown-hole monitoring, improved training and emergencymethods, etc.). Having said this, the oil and gas industryhas multiple low-probability/severe-consequence eventsand for which equates to millions of dollars in cost annuallyfor every small company. Small employers shoulddo their share for preventing risk, but is preventing aone-in-a-million event robust enough; were we qualifiedto perform the hazard assessment?OSHA’s March 2010 enforcement policy may leave asafety professional thinking, “When can FRC not beworn and who will decide if a hazard assessment is comprehensiveand robust enough?” There does not seem tobe any independent judgment by the experts, such as fireprotection professionals, process safety experts or the oiland gas industry, when it comes to flash fire risk whenviewed through the lens of the OSHA 2010 interpretations.The March 2010 policy almost deviates from theenforcement of the long-established, performance-basedprocess of a hazard assessment using recognized expertiseand competence under the authority of §1910.132(a)by listing numerous activities for which FRC is expected,and the October 2010 interpretation presents cleardoubt as to if the oil and gas industry can implementcomprehensive and robust process controls. Therefore,22Well Informed www.asse.org 2011

the interpretations take on a more prescriptive approachto regulating oil and gas well drilling, servicing and production-relatedoperations.OSHA is within its right to enforce and clarify policywhen appropriate; however, both the March and October2010 interpretations imply an expansion of OSHA’s charterbeyond simply performing a public service. It is herewhere the second implication exists, “Is it OSHA’s role tobecome a subject matter expert when it comes to identifyinga risk and controlling hazards for a specific industry?”Codifying measures to protect workers and the communityfor potential risks is clearly warranted, but where is the dueprocess of rulemaking? The role of the safety professionalin guiding employers to a successful outcome to preventrisk becomes less clear if the experts for specific industrysegments become those who write and enforce the rules(i.e., it is like having the fox watch the henhouse).CONCLUSIONThis article is not intended to criticize the agency, butis intended to present a perspective of potential unintendedconsequences of the recent interpretations relative topolicy. At a minimum, these more recent interpretationsleave little room for the oil and gas industry to controlrisk using a hazard assessment and process knowledge,which becomes not only troublesome for safety professionals,but also limits the ability for an organization tomanage resources and control cost. In summary, theauthor is concerned about two implications regarding the2010 OSHA interpretations on the use of FRC. The firstis that there may be a prima facie form of regulating theoil and gas industry without stakeholder consensus ordue process, and the second is that identification andcontrol of hazards have become more difficult for theAmerican industry in which to demonstrate a comprehensiveand robust assessment to achieve compliance.As OSHA turned 40 last year, Assistant SecretaryDavid Michaels’s and Department of Labor SecretaryHilda Solis’s strategies focus on stronger enforcement,whereas some employers need incentives to do the rightthing (OSHA, 2010). The author believes in strongerenforcement and penalties to deter complacent employers;however, let us reflect on where the energy industryis going as safety professionals, for where it came hasbeen through programs, such as PSM, hazard communication,safety by committee and performance-basedmethods, which have matriculated in numerous voluntaryprotection programs and management systems certificationswhere companies have been recognized for ajob well done. These programs motivate consensusbuilding and create the best companies in the world.This is an industry built on “roughnecks” and“roustabouts” who have a “git-r-dun” work ethic, whoare not only “pencil pushers” or “white-collar workers,”but are “salt-of-the-earth” people, Americans who workin some of the most wild and remote areas on earth. Weshould always keep in mind what the President said in arecent State of the Union address, “. . . to help our companiescompete, we also have to knock down barriersthat stand in the way of their success.” All governmentregulations are by the people and for the people—maybeit is time to consider giving some back to the people(State of the Union Address, 2011). REFERENCESAmerican Institute of Chemical Engineers. (1992,April). Guidelines for hazard evaluation procedures (2nded.). With worked examples, Center of Chemical ProcessSafety, Appendix B—Supplemental questions for hazardevaluations.American Petroleum Institute. (2010, Sept. 20).Energizing America: Facts for addressing energy policy.American Petroleum Institute. (2011, Feb. 17). EnergizingAmerica: Facts for addressing energy policy.Curlee, C.K., Broulliard, S.J., Marshall, M.L., et al.(2005). Upstream onshore oil and gas fatalities: A reviewof OSHA’s database and strategic direction for reducingfatal incidents. Prepared for the 2005 SPE/EPA/DOEExploration and Production Environmental Conference,Galveston, TX, March. 7-9, 2005.Engineering News Record. (2010). BP toughens safetyculture. Retrieved Nov. 16, 2010, from http://enr.construction.com/.Fairfax, R. & Witt, S. (2010, Mar.ch19). Enforcementpolicy for flame-resistant clothing in oil and gas drilling,memorandum to regional administrators state designees.Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, OSHA.Maslowski, A. (2010, March/April). The petroleumindustry’s public image. Well Servicing Magazine.Michaels, D. (2010, Jul. 19). OSHA at 40: New challengesand new directions. Comments by the AssistantSecretary, OSHA, U.S. Department of Labor.National Petrochemical & Refiners Association.(2010, April 28). Written statement as submitted to theSubcommittee on Energy and the Environment, U.S.House of Representatives Committee on Energy andCommerce on clean energy policies that reduce ourdependence on oil.Neuman, M. (2011, Jan.). New OSHA sheriff intown. Professional Safety, 8.The White House. (2011, Jan. 25). State of the unionaddress. Washington, DC: Office of the Press Secretary,U.S. Capitol.Christopher S. Clasen, CSP, CFI, CEM, is certified as an ISO14000 and OHSAS 18001 advanced environmental managementsystems auditor and is the owner of CSC Engineering LLC, a professionalenvironmental, fire and safety consulting firm specializingin environmental health and safety (EHS) compliance services.He has more than 25 years’ comprehensive experience in EHS inprivate industry, consulting and public regulatory agencies. Heholds an M.S. in Civil and Environmental Engineering fromCalifornia State University and a B.S. in Mechanical Engineeringfrom the University of California.23Well Informed www.asse.org 2011