VIC Koala Management Strategy - Department of Sustainability and ...

VIC Koala Management Strategy - Department of Sustainability and ...

VIC Koala Management Strategy - Department of Sustainability and ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

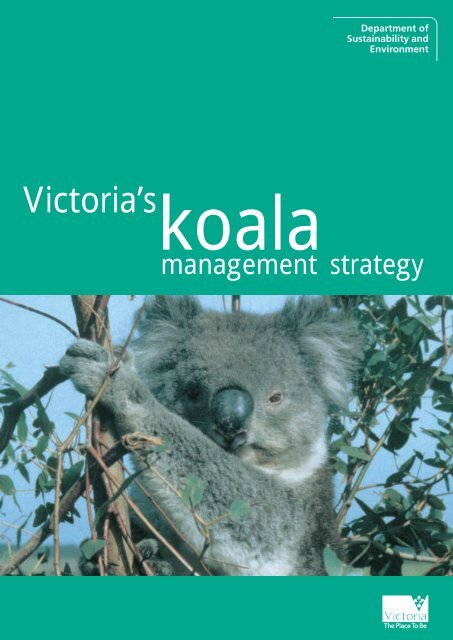

Victoria’skoalamanagement strategy

Victoria’skoalamanagement strategyBiodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> EnvironmentSeptember 2004

Published by the Victorian Government <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong><strong>and</strong> Environment 2004Compiled by Peter Menkhorst, DSE©The State <strong>of</strong> Victoria <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment 2004This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any processexcept in accordance with the provisions <strong>of</strong> the Copyright Act 1968.ISBN 1 74106 6549This publication may be <strong>of</strong> assistance to you but the State <strong>of</strong> Victoria <strong>and</strong>its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw <strong>of</strong>any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes <strong>and</strong>therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequencewhich may arise from your relying on any information in this publication.For further information contact the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong>Environment, PO Box 500, East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 3002.Web: http//www.dse.vic.gov.au (plants <strong>and</strong> animals)Customer Service Centre – phone 136 186Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street,East Melbourne.Printed by Impact Digital, 32 Syme Street, Brunswick.AcknowledgementsMembers <strong>of</strong> the Victorian <strong>Koala</strong> Working Group (1995-1999) played amajor role in the development <strong>of</strong> this strategy. They were: Justin Cook,Alan Crouch, Peter Goldstraw, Dr Kath H<strong>and</strong>asyde, Wayne Hill, PeterMenkhorst, Phil Pegler, Ian Walker <strong>and</strong> Ross Williamson. Likewise, themembers <strong>of</strong> the Parks Victoria/DSE <strong>Koala</strong> Technical Advisory Committee(2000-2004) (Dr Kath H<strong>and</strong>asyde, Pr<strong>of</strong>. Tony Lee, Dr Michael Lynch, PeterMenkhorst, Dr Sally Troy, Ian Walker <strong>and</strong> Dr Chris Weston) havecontributed enormously through wide-ranging discussions <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>management. The contribution <strong>of</strong> discussions with other koala managers<strong>and</strong> researchers is also gratefully acknowledged: they include Barbara StJohn, Bob Inns, Dr Pip Masters, Dr Graeme Moss <strong>and</strong> Dr Glen Shimmin(<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Environment <strong>and</strong> Heritage, South Australia), Dr NatashaMcLean (University <strong>of</strong> Melbourne), Pr<strong>of</strong>. Des Cooper <strong>and</strong> Dr CatherineHerbert (Macquarie University), Dan Lunney (NSW National Parks <strong>and</strong>Wildlife Service), Dr Alistair Melzer (University <strong>of</strong> Central Queensl<strong>and</strong>),<strong>and</strong> Dr John Callaghan (Australian <strong>Koala</strong> Foundation).Barbara Baxter <strong>and</strong> Scott Leech expertly produced Figure 1 usingthe Victorian Fauna Display (DSE).

ContentsAcknowledgments 2IntroductionThe Need for a <strong>Koala</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> 4Key Principles 5Responsibilities 5Policy Framework 6Key Issues in <strong>Koala</strong> <strong>Management</strong> in VictoriaIssue 1. Defining, Ranking <strong>and</strong> Conserving Habitat 8Issue 2. Monitoring Populations 10Issue 3. Managing Over-browsing 10Issue 4. Managing Genetic Structure 12Issue 5. Investigating the Role <strong>of</strong> Chlamydophila in Population Processes 13Issue 6. Underst<strong>and</strong>ing Population Demographics 14Issue 7. Managing Interactions with People 14Issue 8. Managing Captive <strong>Koala</strong>s 14Issue 9. Managing Sick <strong>and</strong> Injured <strong>Koala</strong>s 14Issue 10. Involving the Community 15Issue 11. Implementing the <strong>Strategy</strong> 15The <strong>Strategy</strong>Aim 16Objectives <strong>and</strong> Actions 16References 21AppendicesAppendix 1. Known <strong>Koala</strong> Forage Trees in Victoria 23Appendix 2. Protocols for Translocation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s 23Appendix 3. Decision Tree for Selection <strong>of</strong> Release Sites 27Appendix 4. Glossary 283

IntroductionThe Need for a <strong>Koala</strong><strong>Management</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong>Worldwide, the <strong>Koala</strong> is probably the mostrecognised <strong>of</strong> Australia’s wildlife species. To seea <strong>Koala</strong> is important to a large proportion <strong>of</strong>both domestic <strong>and</strong> international tourists inAustralia. The value <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> as a tourismicon for Australia in 1996 has been estimated at$1.1 billion (Hundloe <strong>and</strong> Hamilton 1997).Further, from the perspective <strong>of</strong> biodiversityconservation, the <strong>Koala</strong> is highly significantbecause it is the only living member <strong>of</strong> itsfamily, the Phascolarctidae. This is an ancientfamily that reached maximum diversity in theOligocene Epoch (34-24 million years ago). Sixgenera <strong>and</strong> 18 fossil species have beendescribed (Black 1999) but only one speciesremains – the <strong>Koala</strong> Phascolarctos cinereus.GovernmentCommonwealthVictoriaSouth AustraliaNew SouthWalesQueensl<strong>and</strong>ACTLegislationEnvironment Protection<strong>and</strong> BiodiversityConservation Act 1999Wildlife Act1975Flora <strong>and</strong> FaunaGuarantee Act 1988National Parks <strong>and</strong>Wildlife Act 1972Threatened SpeciesConservation Act 1995National Parks <strong>and</strong>Wildlife Act 1979Nature ConservationAct 1992Nature ConservationAct 1980StatusNot listedOther ProtectedWildlifeNot listedSchedule 9– RareSchedule 2 –VulnerableProtectedWildlifeCommon Wildlifeexcept for South-eastQueensl<strong>and</strong>Biogeographic Regionwhere VulnerableNot listedOn a national level, the <strong>Koala</strong> is not secure (Melzer, et al.2000) <strong>and</strong> there exists a great deal <strong>of</strong> national <strong>and</strong>international concern for its conservation (Cork, et al. 2000).The level <strong>of</strong> international concern is reflected in the decisionin May 2000 by the U.S. Fish <strong>and</strong> Wildlife Service to list the<strong>Koala</strong> as a threatened species under the U.S. EndangeredSpecies Act. This decision was based largely on documentedrates <strong>of</strong> vegetation clearance within the <strong>Koala</strong>’s distribution.However, in an assessment conducted in 1995 on behalf <strong>of</strong>the Australian Government, the <strong>Koala</strong> was assessed as notmeeting the criteria for listing as a threatened species at thenational level (Maxwell, et al. 1996). In Victoria, the <strong>Koala</strong> hasnot been listed as threatened under the Flora <strong>and</strong> FaunaGuarantee Act. In New South Wales it is listed as Vulnerable,as is the population in South-east Queensl<strong>and</strong> (Table 1).Table 1 Levels <strong>of</strong> legislative protection afforded the <strong>Koala</strong>(at August 2003).Victoria has a large <strong>and</strong> thriving <strong>Koala</strong> population. <strong>Koala</strong>s arewidespread in lowl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> foothill eucalypt forests <strong>and</strong>woodl<strong>and</strong>s across much <strong>of</strong> Victoria where the annual rainfallexceeds about 500 mm (Figure 1). In most Victorian forests<strong>and</strong> woodl<strong>and</strong>s <strong>Koala</strong> population densities are naturally low(

Many <strong>Koala</strong> populations <strong>and</strong>their habitats are protected inVictoria’s conservation reservesystem, including National Parks,Nature Conservation Reserves<strong>and</strong> Special Protection Zones inState Forests.so high that the resulting browsing pressure on preferredtree species is unsustainable, <strong>and</strong> is a direct threat to theintegrity <strong>of</strong> entire forest patches. In other areas, populationsappear to be declining <strong>and</strong> are in need <strong>of</strong> managementsupport. Many <strong>Koala</strong> populations <strong>and</strong> their habitats areprotected in Victoria’s conservation reserve system, includingNational Parks, Nature Conservation Reserves <strong>and</strong> SpecialProtection Zones in State Forests. Other importantpopulations occur in rural <strong>and</strong> semi-rural freehold l<strong>and</strong>, withincreasing infiltration into semi-urban areas, for examplenorth-east Melbourne, Ballarat <strong>and</strong> Portl<strong>and</strong>.Key PrinciplesThis strategy has been developed within the framework <strong>of</strong> thefollowing key principles:• Because the <strong>Koala</strong> is more secure in Victoria than in theother states, Victoria carries a heavy responsibility tomanage its <strong>Koala</strong> populations to ensure that the speciescontinues to flourish in the wild, without damaging othernatural values, as an important component <strong>of</strong> thenation’s biodiversity, <strong>and</strong> as a major tourist drawcard.• Conservation <strong>and</strong> management <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> must beintegrated with other measures to conserve Victoria’sbiological diversity, including Victoria’s Native Vegetation<strong>Management</strong> Framework (<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> NaturalResources <strong>and</strong> Environment 2002) <strong>and</strong> the BioregionalAction Plan process.• Community input <strong>and</strong> involvement is crucial to theeffective management <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> in Victoria.• Local Government planning schemes play a key rolein l<strong>and</strong>-use planning <strong>and</strong> zoning, <strong>and</strong> thus stronglyinfluence the capacity to maintain <strong>Koala</strong> habitat onfreehold l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> other l<strong>and</strong> within the jurisdiction <strong>of</strong>Local Government.• Fragmentation <strong>of</strong> habitat is a serious issue for <strong>Koala</strong>conservation because <strong>of</strong> the species’ specialisation to alow-energy, low-nutrient diet that leaves little scope forincreasing energy expenditure in order to travel betweenhabitat fragments (Hume 1990).• The proclivity <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> populations in some Victorianforests to grow to unsustainable population densities is amajor concern, not only to the <strong>Koala</strong>s themselves, butalso to the ecological integrity <strong>of</strong> the forest communitiesthey inhabit.• The population on French Isl<strong>and</strong> is free <strong>of</strong> diseasesassociated with the organism Chlamydophila <strong>and</strong>therefore has a very high intrinsic rate <strong>of</strong> growth. Havingalready been the saviour <strong>of</strong> Victoria’s <strong>Koala</strong> population –as the source <strong>of</strong> most animals used to successfully reintroducethe <strong>Koala</strong> throughout its natural range inVictoria – its value as insurance against further declineson the mainl<strong>and</strong> is recognised.• Any manipulation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> population numbers shall beundertaken in accordance with strict wildlifemanagement <strong>and</strong> veterinary protocols, including a clearlydocumented rationale for the action. These will bedeveloped after consultation with relevant stakeholders<strong>and</strong> shall be subject to public scrutiny.ResponsibilitiesResponsibility for native fauna in Victoria is vested in theCrown under the provisions <strong>of</strong> the Wildlife Act 1975. This Actconfers protection on all vertebrate animals (except fish) thatare indigenous to Australia. Strategic responsibility formanagement <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s in Victoria rests with the Biodiversity<strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment <strong>and</strong> extends across all public<strong>and</strong> private l<strong>and</strong>. This strategic responsibility includes thedefinition, authorisation <strong>and</strong> coordination <strong>of</strong> appropriate <strong>Koala</strong>management practices. Responsibility for on-ground actionrests with the relevant l<strong>and</strong> manager, within the bounds <strong>of</strong>legislative provisions, this strategy <strong>and</strong> associated guidelines.5

Policy FrameworkThis strategy is intended to sit beneath the ‘National <strong>Koala</strong>Conservation <strong>Strategy</strong>’ (ANZECC 1998). The aim <strong>of</strong> thenational strategy is:‘To conserve <strong>Koala</strong>s by retaining viable populationsin the wild throughout their natural range’.Victoria’s <strong>Koala</strong> <strong>Management</strong> <strong>Strategy</strong> provides guidancetowards achieving the aim <strong>of</strong> the national strategy <strong>and</strong>meeting its six objectives in the State <strong>of</strong> Victoria.A number <strong>of</strong> Victorian Acts <strong>of</strong> Parliament <strong>and</strong> departmentalguidelines are relevant to the management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s. Themost important <strong>of</strong> these <strong>and</strong> their relevance are brieflydescribed below:Prevention <strong>of</strong> Cruelty to Animals Act 1986Provides for legal action against people who cause unduediscomfort to animals in their care, including wild animalscaptured for management purposes. Requires that scientificstudies that utilise wildlife be scrutinised by an accreditedAnimal Experimentation Ethics Committee.Victoria’s Biodiversity <strong>Strategy</strong>Provides a commitment <strong>and</strong> a framework to incorporate flora<strong>and</strong> fauna conservation goals into all activities. A key concept<strong>of</strong> the strategy is the use <strong>of</strong> bioregions as a planningframework, <strong>and</strong> the production <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity Action Plans ineach bioregion.Wildlife Act 1975Provides for the management <strong>of</strong> wildlife, <strong>and</strong> research intowildlife <strong>and</strong> its habitat. It also provides for the control <strong>of</strong>wildlife in situations where wildlife may be causing damage tovegetation or property. The <strong>Koala</strong> is ‘protected wildlife’ underthe Wildlife Act. It is illegal to take, interfere with or destroy<strong>Koala</strong>s without authorisation. Actions to control <strong>Koala</strong>populations that have been authorised under the Wildlife Actinclude translocation <strong>and</strong> fertility control.National Parks Act 1975Allows for to the preservation, protection <strong>and</strong> re-establishment<strong>of</strong> indigenous flora <strong>and</strong> fauna in areas reserved under the Act.Forests Act 1958Provides for the development <strong>of</strong> Forest <strong>Management</strong> Plansthat may include guidelines for the management <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong>forest values, including biodiversity conservation.Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004Provides a framework for sustainable forest management <strong>and</strong>sustainable timber harvesting in State Forests, including anobjective to protect biological diversity <strong>and</strong> maintain essentialbiological processes <strong>and</strong> life-support systems.Planning <strong>and</strong> Environment Act 1987Establishes a system <strong>of</strong> planning schemes based on municipaldistricts to enable l<strong>and</strong>-use policy <strong>and</strong> planning to be easilyintegrated with environmental, social, economic, conservation<strong>and</strong> resource management policies at state, regional <strong>and</strong>municipal levels. Provides for protection <strong>of</strong> natural resources<strong>and</strong> the maintenance <strong>of</strong> ecological processes <strong>and</strong> geneticdiversity. Requires that responsible authorities consider theeffects <strong>of</strong> proposed developments on the environmental values<strong>of</strong> the site. The State Planning Policy Framework for municipalplanning schemes contains objectives for the conservation <strong>of</strong>native flora <strong>and</strong> fauna, <strong>and</strong> the Particular Provisions <strong>of</strong> theplanning schemes contain Native Vegetation RetentionProvisions, which control clearing <strong>of</strong> native vegetation.6

Key Issues in<strong>Koala</strong> <strong>Management</strong> in VictoriaBefore developing a strategy for themanagement <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s in Victoria it is necessaryto identify key issues that influence <strong>Koala</strong>population trends. This section describes 11 keyissues affecting <strong>Koala</strong> populations <strong>and</strong> theirmanagement in Victoria. It is followed by asection that presents the objectives to beachieved in order to adequately address eachkey issue, defines actions necessary to achieveeach objective <strong>and</strong> lists the lead agencies <strong>and</strong>time-frames for their implementation.Issue 1. Defining, Ranking<strong>and</strong> Conserving Habitat<strong>Koala</strong>s are widespread in Victoria <strong>and</strong> occur across a range <strong>of</strong>biogeographical regions <strong>and</strong> habitats. They also occur on mostl<strong>and</strong> tenures, including National Parks <strong>and</strong> other conservationreserves, State Forests, other Crown L<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> freehold l<strong>and</strong>.An essential component <strong>of</strong> informed conservation planning isa detailed underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> what constitutes habitat, <strong>and</strong> thedistribution <strong>and</strong> availability <strong>of</strong> that habitat. This knowledge islacking for the <strong>Koala</strong> in Victoria <strong>and</strong> a program <strong>of</strong> habitatdefinition <strong>and</strong> mapping would assist in planning for <strong>Koala</strong>conservation.Examples <strong>of</strong> high quality <strong>Koala</strong> habitat - Coastal Manna Gumwoodl<strong>and</strong>, Yellow Box woodl<strong>and</strong>, River Red Gum forest.As a start to the process <strong>of</strong> documenting <strong>Koala</strong> habitatavailability, Parks Victoria undertook a GIS-based assessment <strong>of</strong>the extent <strong>and</strong> distribution <strong>of</strong> potential <strong>Koala</strong> habitat inVictoria (Centre for Environmental <strong>Management</strong> 2001). Thisassessment was based upon the distribution <strong>of</strong> EcologicalVegetation Classes (EVCs) containing eucalypts known to bebrowsed by <strong>Koala</strong>s. It provides a useful statewide overview <strong>of</strong>potentially suitable habitat.Tree species that occur naturally in Victoria <strong>and</strong> are knownto be browsed by the <strong>Koala</strong> are listed in Appendix 1. Giventhe level <strong>of</strong> taxonomic revision in the genus Eucalyptus inrecent years, it is likely that many newly described speciesare also eaten, so the list is almost certainly incomplete.The underlying geology <strong>and</strong> soil fertility may also play animportant role in determining the quality <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> habitatthrough their effects on the levels <strong>of</strong> foliage nutrients <strong>and</strong>secondary metabolites (Moore <strong>and</strong> Foley 2000). Thus, a treespecies may be readily eaten in one locality but not favouredat another.Mapping at the statewide scale is useful for obtainingan overview <strong>of</strong> the availability <strong>of</strong> habitat for <strong>Koala</strong>s, forexample, to indicate the distribution <strong>and</strong> extent <strong>of</strong> potentialrelease sites available for use during translocation programs.However, for l<strong>and</strong>-use planning on a local scale, greaterprecision is needed in both habitat definition <strong>and</strong> mapping.For mapping habitat at a level useful for Local Government,the <strong>Koala</strong> Habitat Atlas project <strong>of</strong> the Australian <strong>Koala</strong>Foundation provides a useful model (e.g. Phillips, et al.2000). This methodology combines detailed vegetation<strong>and</strong> soil mapping with a quantified measure <strong>of</strong> local <strong>Koala</strong>preferences for browse tree species, to indicate habitatquality at the local level.There is also a need for further elucidation <strong>of</strong> theenvironmental factors that influence the selection <strong>of</strong>individual browse trees by <strong>Koala</strong>s, so that more sophisticatedmodels <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> habitat quality can be developed <strong>and</strong>applied to l<strong>and</strong>use planning (Moore <strong>and</strong> Foley 2000).Once an area has been recognised as important habitat forthe <strong>Koala</strong>, attention should focus on how best to ensure theconservation or enhancement <strong>of</strong> that habitat. The approachtaken will depend on l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> status. In Victoria,most <strong>Koala</strong> habitat <strong>and</strong> most <strong>Koala</strong>s occur on Crown L<strong>and</strong>.Freehold l<strong>and</strong> has mostly been cleared <strong>of</strong> native vegetation<strong>and</strong>, where <strong>Koala</strong>s persist on freehold, they are <strong>of</strong>ten at low8

In addition to protection <strong>of</strong>existing habitat, the Victoriancommunity is putting a greatdeal <strong>of</strong> effort into revegetationwork throughout the freeholdl<strong>and</strong> estate, through programssuch as L<strong>and</strong>care <strong>and</strong> Bushcare.population densities because the carrying capacity <strong>of</strong> thehabitat has been reduced.Three categories <strong>of</strong> l<strong>and</strong> tenure are particularly relevant:1. Parks <strong>and</strong> reserves – Because the primary aim <strong>of</strong>management in parks <strong>and</strong> reserves is to conserve naturalvalues, one might assume that little work is required toensure the conservation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> habitat in this category.However, a major cause <strong>of</strong> decline in <strong>Koala</strong> habitat inVictoria is over-browsing by the <strong>Koala</strong> itself, <strong>and</strong> mostcases <strong>of</strong> over-browsing occur on parks <strong>and</strong> reserves.Further, the management response to over-browsingfrequently involves other l<strong>and</strong> tenures (for example, asrelease sites for translocated animals), necessitating closecoordination between l<strong>and</strong> management agencies.2. Forests available for commercial timber harvesting –In Victoria there is now relatively little overlap betweencommercial timber harvesting <strong>and</strong> key <strong>Koala</strong> habitat.Exceptions to this include:• hardwood plantation forestry in the Strzelecki Ranges• native forest harvesting in some forests in central<strong>and</strong> western Victoria.Where timber harvesting occurs, the network <strong>of</strong> SpecialProtection Zones (where harvesting is excluded) <strong>and</strong> habitatprescriptions, minimise the impact on local <strong>Koala</strong> populations.3. Freehold l<strong>and</strong> – Protection <strong>and</strong> enhancement <strong>of</strong> habitat onfreehold l<strong>and</strong> relies heavily on voluntary cooperation froml<strong>and</strong>holders. Mechanisms for promoting the conservation<strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s <strong>and</strong> their habitat on freehold l<strong>and</strong> include:• the L<strong>and</strong> for Wildlife Scheme• Trust for Nature covenants• Biodiversity Networks established under Victoria’sbiodiversity framework• Regional Catchment Strategies <strong>and</strong> Whole <strong>of</strong>Catchment Plans• Catchment <strong>Management</strong> Authorityvegetation management plans• Local Government Planning Schemes.In Victoria, Biodiversity Action Plans prepared for eachbioregion will provide an integrated framework for achievingbiodiversity outcomes at a l<strong>and</strong>scape scale. These plans arebeing progressively developed by a coalition <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment, Catchment<strong>Management</strong> Authorities <strong>and</strong> key regional stakeholders. Theyfocus on the protection, enhancement <strong>and</strong> linking <strong>of</strong> remnantvegetation <strong>and</strong> will benefit <strong>Koala</strong> conservation in themedium- to long-term.A strategic framework for native vegetation management isprovided in Victoria’s Vegetation <strong>Management</strong> Framework(<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources <strong>and</strong> Environment 2002)<strong>and</strong> in native vegetation plans prepared by Catchment<strong>Management</strong> Authorities. The Native Vegetation RetentionControls, established under the Planning <strong>and</strong> Environment Act1987, are also an important policy tool for habitat protectionwhen a development or change in l<strong>and</strong> use is proposed onfreehold l<strong>and</strong>.In addition to protection <strong>of</strong> existing habitat, the Victoriancommunity is putting a great deal <strong>of</strong> effort into revegetationwork throughout the freehold l<strong>and</strong> estate, through programssuch as L<strong>and</strong>care <strong>and</strong> Bushcare. This <strong>of</strong>ten includes the reestablishment<strong>of</strong> locally-indigenous eucalypt species <strong>and</strong> willbe <strong>of</strong> increasing benefit to <strong>Koala</strong> populations as theseplantings mature. Revegetation actions should aim to increasethe size <strong>of</strong> existing forest or woodl<strong>and</strong> patches, increase theconnectivity <strong>of</strong> remnants through the establishment <strong>of</strong>corridors <strong>and</strong> stepping stones <strong>of</strong> habitat, <strong>and</strong> provide anincrease in tree cover. Only locally-indigenous plants shouldbe used.9

Issue 2. Monitoring PopulationsThere is evidence that <strong>Koala</strong> populations in some parts <strong>of</strong>Victoria are increasing in density <strong>and</strong> in extent, while in otherplaces populations are declining. In order to be able to mounteffective management responses to these changes, a level <strong>of</strong>knowledge <strong>of</strong> population trends is required. This is particularlycritical for populations with a history <strong>of</strong> over-browsing, orwhich are thought to be approaching unsustainable levels.Populations can be monitored at a number <strong>of</strong> scales. Thecrudest level is to monitor population range by a distributionmapping system, in this case the Atlas <strong>of</strong> Victorian Wildlifeprogram. This scale can indicate medium- to long-termchanges in distribution.More detailed monitoring <strong>of</strong> local populations needsto include an estimate <strong>of</strong> population number, as well as localdistribution. Methods <strong>of</strong> estimating population number thathave been used in Victoria include double-count transects(Caughley <strong>and</strong> Sinclair 1994) <strong>and</strong> the Morgan method <strong>of</strong> linetransectestimation (e.g. Morgan 1999). Both methods haveadvantages <strong>and</strong> disadvantages <strong>and</strong> research is underway todetermine the most appropriate method to use in a range <strong>of</strong>vegetation types, <strong>and</strong> to develop correction factors thataccount for variations in detectability between vegetation types.Population monitoring is necessary in the following situations:1. sites where over-browsing is occurring<strong>and</strong> is being managed2. sites where over-browsing is anticipated to be a problem3. populations <strong>of</strong> special conservation significance,such as those in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong>.4. populations with anecdotal evidence <strong>of</strong> a decline.Issue 3. Managing Over-BrowsingIn some circumstances in southern Australia, <strong>Koala</strong> populationsgrow to unsustainable densities resulting in defoliation <strong>of</strong> theirfavoured food trees. This phenomenon is referred to as overbrowsing.In severe cases, over-browsing leads to widespreadtree death, alterations to the tree species composition <strong>of</strong> theforest (through the killing <strong>of</strong> favoured food species) <strong>and</strong>, inextreme cases, starvation <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s. Over-browsing <strong>of</strong> MannaGum in coastal Victoria has reached a level whereby it isconsidered to be a threat to the conservation <strong>of</strong> two EcologicalVegetation Classes – Damp S<strong>and</strong> Herb-rich Woodl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>Stony Rises Woodl<strong>and</strong>.<strong>Koala</strong> over-browsing was first recorded on Wilsons Promontoryin 1907 (Kershaw 1934), in an environment little changed byEuropeans except for one critical factor – the decline <strong>of</strong> localAboriginal populations. Aboriginal hunting may have helped toconstrain <strong>Koala</strong> population growth (Strahan <strong>and</strong> Martin 1982)<strong>and</strong>, in its absence, over-browsing <strong>and</strong> subsequent populationcrashes may be a regular feature <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> populationdemographics in favoured habitat in southern Australia.A st<strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong> Manna Gums along the Hopkins River atFramlingham that was killed by <strong>Koala</strong> over-browsing duringthe late 1990s.An alternative hypothesis is that over-browsing is aconsequence <strong>of</strong> ecological stresses placed on eucalypts byfragmentation <strong>of</strong> forests <strong>and</strong> woodl<strong>and</strong>s, <strong>and</strong> ecologicalchanges such as altered fire regimes, nutrient cycles <strong>and</strong>hydrological patterns. Eucalypts may respond to such‘stresses’ by producing foliage with higher nitrogen <strong>and</strong>sugar content which makes them even more palatable toherbivores (Jurskis <strong>and</strong> Turner 2002). It is likely that researchinto the ultimate causes <strong>of</strong> over-browsing will be requiredbefore a viable solution to the problem can be achieved.Since 1923, the Victorian Government has activelymanaged over-browsing problems by a program <strong>of</strong>translocating <strong>Koala</strong>s out <strong>of</strong> high-density sites (Figure 1).Initial translocations were onto isl<strong>and</strong>s because they wereconsidered safe havens. Later, the Government began anextensive program <strong>of</strong> re-introduction to mainl<strong>and</strong> habitatleft unoccupied following the dramatic population crashthat occurred in Victoria in the early 1900s. This reintroductionprogram has continued <strong>and</strong> translocationshave taken place in 67 <strong>of</strong> the 80 years since 1923.However, since the mid-1980s the purpose <strong>of</strong> thetranslocations has shifted from re-introduction to habitatprotection at the over-browsed sites (Menkhorst 1995,Martin <strong>and</strong> H<strong>and</strong>asyde 1999).Sites at which serious over-browsing occurs invariably havea few easily recognisable characteristics:• most are isl<strong>and</strong>s, the others are habitat isolates on themainl<strong>and</strong>• all are dominated by Manna Gum; usually the coastalforms Eucalyptus viminalis subsp. pryoriana orEucalyptus viminalis subsp. cygnatensis.• all have only one, or occasionally two, preferredeucalypt species present (see Appendix 1).10

<strong>Koala</strong>s ready for release at a re-introduction site, 1950s.Bringing a <strong>Koala</strong> to ground.In some extensive mixed-species forests, over-browsing <strong>of</strong>individual trees can occur, particularly along drainage lineswhere high-quality browse is more likely to be found.In these situations over-browsing has not led to widespreaddefoliation or to a major loss <strong>of</strong> tree cover. However, overtime, it may result in a change to the eucalypt speciescomposition in valleys.Signs that over-browsing is occurring include reduced canopydensity, <strong>of</strong>ten with tufts <strong>of</strong> leaves remaining on twigs beyondthe reach <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s. This characteristic tufted appearance is animportant clue that the defoliation is due to <strong>Koala</strong>s rather thaninsect attack or loss <strong>of</strong> tree vigour due to other causes.Figure 1. The distribution <strong>of</strong> sightings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s in Victoriasince 1970, the distribution <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> release sites, <strong>and</strong> thelocations <strong>of</strong> populations that have been a source <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>sfor translocation. Data from Atlas <strong>of</strong> Victorian Wildlife, 2004.<strong>Koala</strong> sightings since 1st January 1970<strong>Koala</strong> release sites<strong>Koala</strong> source populations11

12In the development <strong>of</strong> a suitable response to over-browsing,five options have been considered. These, <strong>and</strong> their likelyconsequences, can be summarised as:1. Do nothing – leads to ecological damage<strong>and</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> starvation.2. Translocate – has been highly successful but limitedunoccupied habitat remains, risk <strong>of</strong> creating newover-browsing problems.3. Introduce disease (Chlamydophila) – no control overimpacts, little predictive ability, ethical questions.4. Cull – is a contentious issue within the Australiancommunity, was not supported in the National <strong>Koala</strong>Conservation <strong>Strategy</strong> (ANZECC 1998).5. Reduce birth rate – acceptable to the community,but may not be practicable over large areas.Culling has not been supported as a method <strong>of</strong> populationcontrol in Victoria. Instead, research into potential methods <strong>of</strong>birth control, such as slow-release hormone implants <strong>and</strong>immuno-contraception, has been supported in an attempt to finda means <strong>of</strong> population control that is acceptable to the Victorian,Australian <strong>and</strong> world communities (e.g. Middleton, et al. 2003).A sedated <strong>Koala</strong> is prepared for sterilisation in the field.The following key points need to be considered whendeveloping a strategy to control <strong>Koala</strong> over-browsing at agiven site:1. Early detection <strong>of</strong> high <strong>Koala</strong> population levels <strong>and</strong> signs <strong>of</strong>canopy depletion is essential for successful management.Local knowledge is required to ensure that other potentialcauses <strong>of</strong> dieback have been discounted as the cause <strong>of</strong>canopy depletion.2. Where canopy depletion is apparent in 50% or more <strong>of</strong>trees <strong>of</strong> favoured <strong>Koala</strong> browse species (Appendix 1), acontrol strategy, including an ecological rationale, shouldbe prepared by the l<strong>and</strong> manager. The control strategyshould consider the following points:• An estimate is needed <strong>of</strong> the maximum sustainablepopulation density, or the desired population level forthe site.• The need to rapidly reduce the population to belowthe estimated maximum sustainable level. This can beachieved by either translocation or fertility control, ora combination <strong>of</strong> both, depending on the alternativesavailable in each case.• Survival rates <strong>of</strong> translocated <strong>Koala</strong>s are likely to bestrongly influenced by habitat quality at the releasesite <strong>and</strong> the density <strong>of</strong> resident <strong>Koala</strong> populations.• Currently, the most promising method <strong>of</strong> fertilitycontrol is to use slow-release implants <strong>of</strong> a progestinhormone, such as levonorgestrel, or low-doseoestradiol, in female <strong>Koala</strong>s.• Surgical sterilisation involves tubal transection <strong>and</strong>cautery <strong>of</strong> females <strong>and</strong>/or vasectomisation <strong>of</strong> males.The efficacy <strong>of</strong> male fertility control is unclear pendinga better underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> paternity patterns in <strong>Koala</strong>populations. However, vasectomy <strong>of</strong> males is lessinvasive <strong>and</strong> less costly than tubal transection <strong>of</strong>females.• Surgical sterilisation is an irreversible method <strong>of</strong>fertility control. Therefore, careful <strong>and</strong> informedmodelling <strong>of</strong> the population should be used todetermine the proportion <strong>of</strong> animals that need to betreated to achieve the desired result.• Because <strong>of</strong> possible cumulative effects, it isimportant that animals are not subjected to surgicalsterilisation <strong>and</strong> long-distance translocation in quicksuccession. An alternative strategy is to surgicallysterilise animals <strong>and</strong> release them at the point <strong>of</strong>capture, with the option <strong>of</strong> recapture <strong>and</strong>translocation at a later date. This strategy will notproduce a rapid decline in population number, butmay, over time, produce a decline, depending onthe proportion <strong>of</strong> animals treated.3. If capture, translocation or fertility control is to be part <strong>of</strong>the management response, an authorisation under theWildlife Act 1975, issued by the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment, will be required.4. An essential tool for informing the development <strong>of</strong> controlstrategies will be a <strong>Koala</strong> population model (see Issue 6).5. When undertaking translocations, the decision on whetheror not to include fertility control will depend partly on theavailability <strong>of</strong> release sites <strong>of</strong> adequate size, habitat quality<strong>and</strong> connectivity to accommodate an exp<strong>and</strong>ingpopulation. Sterilisation or contraception <strong>of</strong> animals to betranslocated gives greater flexibility in selection <strong>of</strong> releasesites by allowing release into smaller habitat patches, <strong>and</strong>greater confidence that future over-browsing problems willnot be set in train.

6. All translocation programs should include an on-goingprogram <strong>of</strong> fertility control in the population remaining atthe over-browsed site.7. Detailed protocols for capture, translocation <strong>and</strong> release <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong>s are provided in Appendix 2.8. If over-browsing threatens to kill st<strong>and</strong>s <strong>of</strong> trees, theprotection <strong>of</strong> individual trees to maintain genetic diversityby providing sources <strong>of</strong> local seed, may be a priority. Forisolated trees this can be achieved by b<strong>and</strong>ing the trunk ormain branches with a one metre high ring <strong>of</strong> sheet tin.Issue 4.Managing Genetic StructureVictorian <strong>Koala</strong>s have a most unusual genetic history. <strong>Koala</strong>populations in Victoria declined drastically during the early1900s. By the 1930s, the <strong>Koala</strong> on the Victorian mainl<strong>and</strong> wasthought to be confined to a few remnant populations in SouthGippsl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> the Mornington Peninsula (Lewis 1954).Fortunately, local people had introduced a few <strong>Koala</strong>s toFrench Isl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Phillip Isl<strong>and</strong> in Western Port during the1890s <strong>and</strong> early 1900s. The descendants <strong>of</strong> these animals havesince been used to restock unoccupied habitat across Victoriain one <strong>of</strong> the largest <strong>and</strong> most successful wildlife reintroductionprograms ever undertaken.Unfortunately, the stock used to found the French Isl<strong>and</strong>population in about 1898 probably comprised only a fewanimals, thereby creating a severe genetic bottleneck. Thefounders for the Phillip Isl<strong>and</strong> population were more numerous<strong>and</strong> from a greater geographical range, but never-the-less alsorepresent a significant genetic bottleneck. An unforeseenconsequence <strong>of</strong> using these populations to restock theVictorian mainl<strong>and</strong> is likely to have been the genetic swamping<strong>of</strong> any remnant populations by the restricted <strong>and</strong> in-bredisl<strong>and</strong> gene pool. Thus, the level <strong>of</strong> genetic variation inVictorian <strong>Koala</strong> populations is significantly lower than thatfound across comparable areas in NSW <strong>and</strong> Qld (Houlden,et al. 1996, 1999). It is also lower than in several species <strong>of</strong>endangered marsupial including the Bilby, Bridled NailtailWallaby <strong>and</strong> Queensl<strong>and</strong> populations <strong>of</strong> Yellow-footed RockWallaby, but is higher than in the two species <strong>of</strong> hairy-nosedwombat (Bower, et al. 2002). Therefore, there is a higherthreat <strong>of</strong> inbreeding depression in Victorian <strong>Koala</strong> populationsthan in <strong>Koala</strong> populations further north.Although genetic theory predicts that populations with lowgenetic variation will have lower survival prospects, there iscurrently no evidence that the population growth potential <strong>of</strong>Victorian <strong>Koala</strong>s is being constrained by their genetic history.On the contrary, many populations derived from isl<strong>and</strong> stockare flourishing. However, given the finding that a higher thannormal proportion <strong>of</strong> male <strong>Koala</strong>s on French Isl<strong>and</strong> exhibittesticular aplasia (Seymour, et al. 2001), it would be prudentto be alert to signs <strong>of</strong> inbreeding depression in Victorian<strong>Koala</strong>s (Sherwin, et al. 2000).Only in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong> does it appear that some remnants <strong>of</strong>the original gene pool survive, thanks to a strong remnantpopulation <strong>and</strong> few releases <strong>of</strong> isl<strong>and</strong> stock. However, currentinformation on the geographic spread <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s with thishigher genetic variation is poor. Further, very little <strong>Koala</strong>habitat in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong> is reserved for conservationpurposes. Most is highly fragmented, <strong>and</strong> some is threatenedby unsympathetic l<strong>and</strong> uses. Therefore, if significant remnantgenetic resources persist in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong> it is imperative toensure that habitat is protected as far as possible (Objective 2).It may also be prudent to spread the risk to the remnant SouthGippsl<strong>and</strong> population by establishing new populations, usingfounders from South Gippsl<strong>and</strong>, in areas isolated from theeffects <strong>of</strong> the re-introduction program. The WonnangattaValley has been suggested as one such locality (Martin 1989).Releasing <strong>Koala</strong>s from French Isl<strong>and</strong> onto Kangaroo Isl<strong>and</strong>,South Australia, 1925.13

Issue 5. Investigating theRole <strong>of</strong> Chlamydophila inPopulation ProcessesDiseases associated with the micro-organism Chlamydophilacan have a significant impact on individual <strong>Koala</strong>s <strong>and</strong> onpopulation growth rates. In Victoria, overt clinical symptomsare rarely seen, the main effect being chronic infertility. Ingeneral, populations which are free <strong>of</strong> Chlamydophila havefertility rates <strong>of</strong> 70-95% <strong>and</strong> have the potential to double insize every few years, whereas populations infected withChlamydophila have fertility rates from close to zero up to80% <strong>and</strong> usually have considerably slower growth rates(Martin 1989). In some cases, for example on Phillip Isl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>in The Grampians, widespread infertility caused byChlamydophila is believed to have been a major cause <strong>of</strong>population decline. Current knowledge about the strains <strong>of</strong>Chlamydophila in Victoria, their distribution, <strong>and</strong> impacts onpopulation demography is rudimentary.There is currently no means <strong>of</strong> managing this disease in wild<strong>Koala</strong> populations so its relevance to this strategy relatesmainly to the aim <strong>of</strong> avoiding rapid exposure <strong>of</strong> naive animalsto Chlamydophila as a consequence <strong>of</strong> translocation.Issue 6. Underst<strong>and</strong>ing PopulationDemographicsTo apply fertility control techniques at the population level it isnecessary to be able to predict population trends under variouslevels <strong>of</strong> fertility control, so that the most effective programcan be devised <strong>and</strong> implemented. This is best achievedthrough construction <strong>of</strong> a computer model that simulates<strong>Koala</strong> population fluctuations under a range <strong>of</strong> recruitment<strong>and</strong> mortality levels. Basic data on age structure, age-specificfecundity, <strong>and</strong> age-specific mortality was obtained from largesamples <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s captured during recent translocationprograms. These data have allowed the construction <strong>of</strong> acustom-built <strong>Koala</strong> population model, for both Chlamydophilafree<strong>and</strong> Chlamydophila-affected populations (McLean 2003).Issue 7. Managing Interactionswith People<strong>Koala</strong>s frequently come into contact with human society,usually to the detriment <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong>s. <strong>Koala</strong> populationsoccur on the urban fringes <strong>of</strong> Melbourne, Ballarat <strong>and</strong> severalsmaller towns. In such situations they can be harassed by dogs<strong>and</strong> threatened by road traffic. Numerous <strong>Koala</strong>s utilise habitatclose to major highways <strong>and</strong> deaths from being struck byvehicles are common. Livestock, particularly cattle, are alsoknown to harass <strong>and</strong> even kill <strong>Koala</strong>s that are attempting tocross paddocks. While not necessarily threatening the viability<strong>of</strong> populations, all <strong>of</strong> these situations cause concern tomembers <strong>of</strong> the public <strong>and</strong> create dem<strong>and</strong>s on the time <strong>of</strong>agency staff, Local Government rangers <strong>and</strong> voluntary wildlifecarers. A program <strong>of</strong> community education would help tominimise the frequency <strong>of</strong> such problems <strong>and</strong> help to ensurean appropriate response when situations arise.Wildlife veterinarians from Melbourne Zoo checking <strong>Koala</strong>health on Raymond Isl<strong>and</strong>, 2004.In recent years improvements in the design <strong>and</strong> construction<strong>of</strong> major roads have resulted in reductions in the frequency <strong>of</strong>road trauma to <strong>Koala</strong>s at key sites. Improvements include<strong>Koala</strong>-pro<strong>of</strong> fencing <strong>and</strong> underpasses beneath major roads.A good example <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> sensitive design is the Woodendbypass on the Calder Freeway. In areas with high levels <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong> road mortality, such design features should beincorporated into all major road works.Issue 8. Managing Captive <strong>Koala</strong>s<strong>Koala</strong>s may be kept in captivity only by holders <strong>of</strong> aCommercial Wildlife Licence (Wildlife Demonstrator or WildlifeDisplayer) under the Wildlife Regulations 2002. A condition <strong>of</strong>a Commercial Wildlife Licence is that the Secretary,<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment approve thedesign <strong>and</strong> construction <strong>of</strong> the display facilities. Further, thelicensee must conform to the Code <strong>of</strong> Practice for the PublicDisplay <strong>and</strong> Exhibition <strong>of</strong> Animals 1994, produced underthe Prevention <strong>of</strong> Cruelty to Animals Act 1986. <strong>Koala</strong>s fordisplay must be obtained from existing captive stocks. Permitsto take <strong>Koala</strong>s from the wild will not normally be issued by the<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment.Husb<strong>and</strong>ry st<strong>and</strong>ards for the management <strong>of</strong> captive <strong>Koala</strong>sare provided by Jackson (2003). These should be promoted asthe benchmark for captive husb<strong>and</strong>ry st<strong>and</strong>ards.A major difficulty in maintaining captive <strong>Koala</strong>s is the provision<strong>of</strong> adequate fresh eucalypt foliage. In the past some displayershave harvested foliage from remnant eucalypt forest close totheir facility. This can lead to unacceptable pruning <strong>of</strong>significant vegetation remnants.14

Issue 9. Managing Sick <strong>and</strong>Injured <strong>Koala</strong>sPartly because <strong>of</strong> the iconic status <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong>, there isfrequently a good deal <strong>of</strong> concern shown by members <strong>of</strong> thepublic when an injured <strong>Koala</strong> is found. However, because<strong>Koala</strong>s are powerful animals <strong>and</strong> have sharp claws, theirh<strong>and</strong>ling by untrained people can lead to serious injury. As forall wildlife, the care <strong>and</strong> rehabilitation <strong>of</strong> sick <strong>and</strong> injured<strong>Koala</strong>s is undertaken by skilled volunteer wildlife carers, or bystaff <strong>of</strong> Healesville Sanctuary <strong>and</strong> Melbourne Zoo. There is aneed for public education about whom to contact when adebilitated <strong>Koala</strong> is found.Issue 10. Involving the CommunityThe enormous public interest <strong>and</strong> goodwill towards the <strong>Koala</strong>provides an excellent opportunity to involve the community inpractical wildlife conservation actions. Community involvementin the implementation <strong>of</strong> this strategy is perhaps the best wayto promote realistic <strong>and</strong> sensible attitudes towards <strong>Koala</strong>management in Victoria. It would also help to ensure that thisstrategy is fully implemented.Some areas <strong>of</strong> important <strong>Koala</strong> habitat have culturalsignificance for local Aboriginal people. In such cases liaisonwith local Aboriginal organisations with a view to developingcollaborative management arrangements can have manysynergies <strong>and</strong> will be encouraged.Issue 11. Implementing the<strong>Strategy</strong>On freehold l<strong>and</strong> the primary avenue for achievingimplementation <strong>of</strong> this strategy will be through the BioregionalBiodiversity Action Plans being produced by the <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>Sustainability</strong> <strong>and</strong> Environment <strong>and</strong> Catchment <strong>Management</strong>Authorities. On Crown L<strong>and</strong> responsibility lies with the l<strong>and</strong>management agency, with DSE providing direction on crosstenureissues.For issues relating to research <strong>and</strong> monitoring, <strong>and</strong> the control<strong>of</strong> over-browsing, DSE <strong>and</strong> Parks Victoria have established anindependent scientific advisory body, the <strong>Koala</strong> TechnicalAdvisory Committee, to provide scientific advice <strong>and</strong> reviewproposals.15

The <strong>Strategy</strong>AIM: The aim <strong>of</strong> this strategy is to ensure thatviable wild populations <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> persistwherever suitable habitat occurs throughouttheir natural (i.e. pre-European settlement)range in Victoria.Objectives <strong>and</strong> ActionsThe time frames nominated for each objective are indicativeonly. Short-term objectives should be addressed within threeyears <strong>of</strong> the release <strong>of</strong> this strategy, medium-term objectiveswithin five years <strong>and</strong> long-term within ten years.Issue 1. Defining, ranking <strong>and</strong>conserving habitatObjective 1To conserve the <strong>Koala</strong> <strong>and</strong> its habitat through jointcollaborative management <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> habitat <strong>and</strong> populationsacross l<strong>and</strong> tenures.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division, inpartnership with Parks Victoria, DSE Parks <strong>and</strong> Forests Division,Catchment <strong>Management</strong> Authorities, <strong>and</strong> Local Government.Timeframe: short-termAction 1:• Officers <strong>of</strong> State <strong>and</strong> Local Government agencies willensure that the habitat needs <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> are addressedthrough the application <strong>of</strong> all relevant vegetationprotection <strong>and</strong> vegetation management policies.Priority: highAction 2:• Ensure that <strong>Koala</strong> management is adequately consideredduring the development <strong>of</strong> Biodiversity Action Plans, Park<strong>Management</strong> Plans, Forest <strong>Management</strong> Area Plans, <strong>and</strong>during reviews <strong>of</strong> the Codes <strong>of</strong> Forest <strong>Management</strong>Practices for both Crown l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> freehold l<strong>and</strong>. Peoplewriting or revising such plans must be aware <strong>of</strong> thehabitat requirements <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> in their local area, <strong>and</strong>must ensure that these are accounted for in the plans.Improving linkages between remnant forest <strong>and</strong>woodl<strong>and</strong> patches is particularly important for the <strong>Koala</strong>.Priority: highObjective 2To develop a clear underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the distribution <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Koala</strong> <strong>and</strong> its habitat across Victoria <strong>and</strong> across all l<strong>and</strong>tenures.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division.Timeframe: short-termAction 3:• Establish a system for reporting <strong>and</strong> curating observations<strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s feeding, including accurate identification <strong>of</strong>tree species, to gain a more complete underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong> food tree preferences.Priority: mediumAction 4:• Encourage all staff <strong>of</strong> DSE, Parks Victoria <strong>and</strong> the generalpublic to report sightings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s to the Atlas <strong>of</strong>Victorian Wildlife.Priority: mediumObjective 3To develop detailed maps <strong>of</strong> the distribution <strong>and</strong> quality <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong> habitat in appropriate Local Government Areas <strong>and</strong>incorporate these maps into overlays <strong>of</strong> environmentalsignificance on shire planning schemes.Lead Agent: Local Government in partnership with Australian<strong>Koala</strong> Foundation <strong>and</strong> DSE.Timeframe: medium-termAction 5:• Local Government, in partnership with the Australian<strong>Koala</strong> Foundation, should undertake <strong>Koala</strong> Habitat Atlasmapping in key Local Government Areas. Priorities forLocal Government Areas to be assessed should be basedon degree <strong>of</strong> pressure for development in areas occupiedby <strong>Koala</strong>s.Priority: highAction 6:• Once <strong>Koala</strong> habitat mapping is completed the LocalGovernment should transfer the information toEnvironmental Significance Overlays that define, rank<strong>and</strong> map <strong>Koala</strong> habitat.Priority: high16

To manage <strong>Koala</strong> populationsizes in habitat isolates so thatover-browsing damage toeucalypt communities is kept toacceptable, sustainable levels <strong>and</strong>over-browsed vegetation is ableto recover.Issue 2. Monitoring populationsObjective 4To develop estimates <strong>of</strong> population sizes in key areas, <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>the trend in population numbers at those sites.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division(State Forest <strong>and</strong> freehold l<strong>and</strong>) <strong>and</strong> Parks Victoria(conservation reserves).Timeframe: short- to medium-termAction 7:• Conduct comparisons <strong>of</strong> a variety <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> censustechniques in a range <strong>of</strong> forest types to compare theiraccuracy <strong>and</strong> cost.Priority: highAction 8:• Develop a st<strong>and</strong>ardised technique (or techniquesappropriate to broad habitat types) to estimate <strong>Koala</strong>population numbers that can be implemented by trainedagency staff or volunteers, <strong>and</strong> use this technique tomonitor <strong>Koala</strong> numbers at sites where activemanagement is occurring or desirable, <strong>and</strong> also where apopulation decline is postulated.Priority: highIssue 3. Managing over-browsingObjective 5To manage <strong>Koala</strong> population sizes in habitat isolates so thatover-browsing damage to eucalypt communities is kept toacceptable, sustainable levels <strong>and</strong> over-browsed vegetation isable to recover.Lead Agent: DSE Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Program in partnership withParks Victoria <strong>and</strong> other affected l<strong>and</strong> managers.Timeframe: short- to medium-termAction 9:• Ensure that ecological rationales are included in themanagement strategy for each site where <strong>Koala</strong>population management is proposed.Priority: highAction 10:• Arrange the purchase or manufacture <strong>of</strong> slow-releaseimplants containing the progestin hormonelevonorgestrel, or oestradiol, to be applied at suitablesites where <strong>Koala</strong> populations are unsustainably high.Priority: highAction 11:• Continue to investigate the efficacy <strong>of</strong> a range <strong>of</strong> othermethods <strong>of</strong> fertility control in the <strong>Koala</strong>.Priority: highAction 12:• Develop veterinary st<strong>and</strong>ards against which to assess thecapacity <strong>of</strong> individual <strong>Koala</strong>s to withst<strong>and</strong> the rigours <strong>of</strong>translocation or fertility control.Priority: highAction 13:• Investigate the cost-effectiveness <strong>and</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> the use<strong>of</strong> tranquillising drugs delivered by darts as an alternativeto the traditional noose <strong>and</strong> flag method for capturinglarge numbers <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s (e.g. Lynch <strong>and</strong> Martin 2003).Priority: mediumAction 14:• Initiate field trials <strong>of</strong> techniques for remote delivery <strong>of</strong>hormone implants or other fertility control agents viaa dart gun. This delivery method would be a majoradvance towards cost-effective fertility control ona wide scale.Priority: highAction 15:• Develop a method for scoring tree condition that willallow efficient assessment <strong>of</strong> over-browsing impacts, <strong>and</strong>changes in condition over time.Priority: high17

Objective 6To underst<strong>and</strong> the underlying causes for over-browsing <strong>and</strong>reasons for it arising at some sites <strong>and</strong> not at others.Lead Agency: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Divisionin conjunction with an appropriate ecological researchinstitute.Time frame: medium to long-termAction 16:• Facilitate research into ecological <strong>and</strong> tree physiologicalfactors that are associated with <strong>Koala</strong> over-browsing.Priority: mediumIssue 4. Managinggenetic structureObjective 7To conserve the remnant genotype in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s,<strong>and</strong> to ensure that the low level <strong>of</strong> genetic variation in <strong>Koala</strong>selsewhere in Victoria does not adversely affect the capacity <strong>of</strong>the species to survive <strong>and</strong> flourish in this state.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division inconjunction with an appropriate genetics research laboratory.Timeframe: medium- to long-termAction 17:• Initiate a detailed survey <strong>of</strong> genetic diversity, usingmicrosatellite <strong>and</strong> mitochondrial DNA markers, acrossSouth Gippsl<strong>and</strong>, from Western Port to Sale <strong>and</strong> from thePrincess Highway to Refuge Cove, Wilsons Promontory.Priority: highAction 18:• Facilitate research into the relationship betweenthe low genetic diversity <strong>of</strong> Victorian <strong>Koala</strong>s <strong>and</strong>population fitness.Priority: mediumAction 19:• If surveys <strong>of</strong> genetic diversity in South Gippsl<strong>and</strong> indicatethat the remnant genotype is geographically restrictedwithin that area, investigate the practicality <strong>and</strong> value <strong>of</strong>artificially disseminating the diverse genotype(s) morewidely through the Victorian population.Priority: mediumAction 20:• Depending on the outcome <strong>of</strong> Actions 16 <strong>and</strong> 18,investigate the suitability <strong>of</strong> the Wonnangatta Valley as<strong>Koala</strong> habitat. If it is deemed suitable, use <strong>Koala</strong>s fromSouth Gippsl<strong>and</strong> to establish a population there bytranslocation. Obtain advice from <strong>Koala</strong> geneticists on anappropriate number <strong>of</strong> founder animals, having regardfor possible impacts on the source populations.Priority: mediumAction 21:• Facilitate the collection <strong>and</strong> analysis <strong>of</strong> DNA samples fromother areas <strong>of</strong> Victoria where remnant genes may persist.Such areas include East Gippsl<strong>and</strong>, Stony Rises [roughlybetween Colac <strong>and</strong> Cobden] <strong>and</strong> Strathbogie Plateau.Priority: mediumIssue 5. Investigating the role <strong>of</strong>Chlamydophila in populationprocessesObjective 8To gain an improved underst<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>of</strong> the prevalence, strains<strong>and</strong> impacts <strong>of</strong> Chlamydophila acting on Victorian <strong>Koala</strong>populations.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division inpartnership with veterinary research institutes.Timeframe: medium- to long-termAction 22:• Initiate a survey <strong>of</strong> the Chlamydophila status <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>populations throughout Victoria. The aims are to identifypopulations which are antibody positive, <strong>and</strong> those whichare antibody negative to Chlamydophila, to identify thespecies <strong>and</strong> strains <strong>of</strong> Chlamydophila present, to recordthe prevalence <strong>of</strong> clinical signs <strong>of</strong> the disease, <strong>and</strong> toidentify populations <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s in which Chlamydophilaappears to be a significant factor affecting populationdemographics.Priority: mediumAction 23:• Use the results <strong>of</strong> Action 22 to reassess the relationshipbetween Chlamydophila status <strong>and</strong> populationmanagement needs, including selection <strong>of</strong> release sitesfor translocated <strong>Koala</strong>s.Priority: medium18

Issue 6: Underst<strong>and</strong>ingpopulation demographicsObjective 9To develop the capacity to accurately predict the demographicresponse <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> populations to a range <strong>of</strong> managementactions <strong>and</strong> stochastic events.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural ResourcesDivision in partnership with Parks Victoria <strong>and</strong> theUniversity <strong>of</strong> Melbourne.Timeframe: short-termAction 24:• Facilitate the preparation <strong>of</strong> a species-specificdemographic model for the <strong>Koala</strong> using demographicdata collected from the Snake Isl<strong>and</strong>, Framlingham <strong>and</strong>Mt Eccles populations during 1997-2001. Use the modelto predict the levels <strong>of</strong> translocation or fertility controlnecessary to achieve management aims at sites whereover-browsing is a concern.Priority: high.Issue 7: Managing interactionswith peopleObjective 10To improve underst<strong>and</strong>ing within the community <strong>of</strong> how tolive with local <strong>Koala</strong>s in a benign manner.Lead Agent: DSE Flora <strong>and</strong> Fauna Program <strong>and</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong>Animal Welfare in partnership with Catchment <strong>Management</strong>Authorities <strong>and</strong> Local Government.Timeframe: short-termAction 25:• Initiate a widespread community education programstressing requirements for living with <strong>Koala</strong>s in suburbanenvironments, rehabilitating habitat for <strong>Koala</strong>s in ruralareas, <strong>and</strong> the need for responsible dog ownership.Priority: mediumIssue 8: Managing captive <strong>Koala</strong>sObjective 11To have all existing <strong>Koala</strong> displayers achieve self-sufficiency in theprovision <strong>of</strong> eucalypt browse for their <strong>Koala</strong>s within eight years<strong>of</strong> adoption <strong>of</strong> this strategy, <strong>and</strong> to ensure that new licences todisplay <strong>Koala</strong>s are not issued unless the applicant c<strong>and</strong>emonstrate self-sufficiency in the provision <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong> browse.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division.Timeframe: medium-termAction 27:• Implement a licence requirement that the licenseeestablish plantations <strong>of</strong> appropriate eucalypt species(Appendix 1), so that eucalypt foliage is obtained solelyfrom plantations grown specifically for that purpose.Priority: lowIssue 9: Managing sick <strong>and</strong>injured <strong>Koala</strong>sObjective 12To ensure that sick or injured <strong>Koala</strong>s receive appropriate care<strong>and</strong> attention by properly qualified carers.Lead Agent: DSE Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> Natural Resources Division<strong>and</strong> Bureau <strong>of</strong> Animal Welfare in partnership with AnimalWelfare Advisory Committee.Timeframe: short-termAction 28:• Ensure that staff <strong>of</strong> Local Government <strong>and</strong> StateGovernment agencies are fully appraised <strong>of</strong> theavailability <strong>of</strong> experienced wildlife veterinarians orwildlife carers who are trained in the h<strong>and</strong>ling <strong>and</strong>care <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s.Priority: highAction 26:• Liaise with VicRoads to encourage <strong>Koala</strong>-friendly roaddesign in key <strong>Koala</strong> habitat.Priority: medium19

Issue 10: Involving the communityObjective 13To involve the community in implementation <strong>of</strong> this strategywherever practicable.Lead Agent: DSE in partnership with Local Government,Catchment <strong>Management</strong> Authorities <strong>and</strong> Parks Victoria.Timeframe: short-termAction 29:• Encourage agency staff <strong>and</strong> members <strong>of</strong> the public toreport sightings <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s, including road-killed animals,to the Atlas <strong>of</strong> Victorian Wildlife database.Priority: mediumAction 30:• Encourage members <strong>of</strong> the public to report signs <strong>of</strong>impending over-browsing damage to local DSE or ParksVictoria staff.Priority: highAction 31:• Encourage community-based population monitoring inkey areas such as suburban or township l<strong>and</strong>, <strong>and</strong> inparks <strong>and</strong> reserves where a friends group is active. Areaswhere population declines are thought to be occurringshould also be targeted. Provide guidelines on the mostappropriate methods for population monitoring.Priority: highAction 32:• Develop partnerships with Aboriginal organisations t<strong>of</strong>oster Aboriginal participation in the management <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong>s <strong>and</strong> their habitat in areas <strong>of</strong> cultural significancefor Aboriginal people.Priority: mediumIssue 11: Implementingthe strategyObjective 14To achieve coordinated <strong>and</strong> smooth implementation <strong>of</strong>this strategy.Lead Agent: DSE in partnership with Parks Victoria.Timeframe: short-termAction 33:• When interventionist actions such as translocation orfertility control are proposed, detailed strategic plans willbe prepared by the l<strong>and</strong> management agency <strong>and</strong>submitted to DSE as part <strong>of</strong> the application for a permitto undertake the work, as required under the WildlifeAct 1975. These plans will need to give adequateattention to cross-tenure issues <strong>and</strong> collaborationbetween the relevant l<strong>and</strong> managers.Priority: high.Objective 15To provide the best available advice on technical issues relatedto implementation <strong>of</strong> this strategy.Lead Agent: DSE in partnership with Parks Victoria.Timeframe: short-termAction 34:• A <strong>Koala</strong> Technical Advisory Committee, jointly convenedby Parks Victoria <strong>and</strong> DSE, has been established toprovide independent scientific advice about all aspects <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong> management, <strong>and</strong> to provide scientific scrutiny <strong>of</strong><strong>Koala</strong> research <strong>and</strong> monitoring initiated under thisstrategy.Priority: highObjective 16To review all aspects <strong>of</strong> this strategy <strong>and</strong> its implementationafter five years. Lead agency: DSE.Action 35:• Conduct a thorough review <strong>of</strong> the strategy <strong>and</strong> progresstowards its implementation five years after its adoptionby the Victorian Government, ie. in 2009.Priority: medium20

ReferencesANZECC. 1998. National <strong>Koala</strong> Conservation <strong>Strategy</strong>.Environment Australia, Canberra, ACT.Black, K. 1999. Diversity <strong>and</strong> relationships <strong>of</strong> living <strong>and</strong> extinct<strong>Koala</strong>s (Phascolarctidae, Marsupialia). AustralianMammalogy 21: 16-17.Bower, J. C., Newell, G. R. <strong>and</strong> Eldridge, M. D. B. 2002.Genetic effects <strong>of</strong> habitat contraction on Lumholtz’s treekangaroo(Dendrolagus lumholtzi) in the Australian WetTropics. Conservation Genetics 3: 61-69.Caughley, G. <strong>and</strong> Sinclair, A. 1994. Wildlife Ecology <strong>and</strong><strong>Management</strong>. Blackwell Science. Cambridge,Massachusetts.Centre for Environmental <strong>Management</strong>. 2001. Preliminary<strong>Koala</strong> Habitat Capability Assessment <strong>of</strong> Crown L<strong>and</strong> inVictoria. Unpublished report to <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> NaturalResources <strong>and</strong> Environment. University <strong>of</strong> Ballarat, Ballarat,Victoria.Cork, S. J., Clark, T. W. Mazur, N. 2000. Introduction: aninterdisciplinary effort for <strong>Koala</strong> conservation. ConservationBiology 14: 606-609.<strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources <strong>and</strong> Environment 2002.Victoria’s Native Vegetation <strong>Management</strong>: A Frameworkfor Action. <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong> Natural Resources <strong>and</strong>Environment, Melbourne.Houlden, B. A., Engl<strong>and</strong>, P. R., Taylor, A. C., Greville, W. D. <strong>and</strong>Sherwin, W. B. 1996. Low genetic variability <strong>of</strong> the koalaPhascolarctos cinereus in south-eastern Australia followinga severe population bottleneck. Molecular Ecology5:269-281.Houlden, B. A., Costello, B. H., Sharkey, D., Fowler, E., Melzer,A., Ellis, W., Carrick, F., Baverstock, P. <strong>and</strong> Elphinstone, M.S. 1999. Phylogenetic differentiation in the mitochondrialcontrol region in the koala, Phascolarctos cinereus(Goldfuss 1817). Molecular Ecology 8: 999-1011.Hume, I. D. 1990. Biological basis for vulnerability <strong>of</strong> <strong>Koala</strong>s tohabitat fragmentation. Pp 32-35 in <strong>Koala</strong> Summit:Managing <strong>Koala</strong>s in New South Wales. Proceedings <strong>of</strong> the<strong>Koala</strong> summit held at the University <strong>of</strong> Sydney, 7-8November 1988. Ed by D. Lunney, C. A. Urquhart <strong>and</strong> P.Reed. New South Wales National Parks <strong>and</strong> WildlifeService, Sydney.Hundloe, T. <strong>and</strong> Hamilton, C. 1997. <strong>Koala</strong>s <strong>and</strong> Tourism: anEconomic Evaluation. Discussion paper 13. The AustraliaInstitute, Canberra.Jackson, S. (ed). 2003. Australian Mammals: Biology <strong>and</strong>Captive <strong>Management</strong>. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.Jurskis, V. <strong>and</strong> Turner, J. 2002. Eucalypt dieback in easternAustralia: a simple model. Australian Forestry 65: 87-98.Kershaw, J. A. 1934. The <strong>Koala</strong> on Wilsons Promontory.The Victorian Naturalist 51: 76-77.Lee, A. K., Martin, R. W. <strong>and</strong> H<strong>and</strong>asyde, K. A. 1991.Experimental translocation <strong>of</strong> koalas to new habitat. Pp.299-312 in Biology <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong>. Ed. by A. K. Lee, K. A.H<strong>and</strong>asyde <strong>and</strong> G. D. Sanson. Surrey Beatty & Sons,Chipping Norton, NSW.Lewis, F. 1954. The rehabilitation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> in Victoria.The Victorian Naturalist 70: 197-200.Lynch, M. <strong>and</strong> Martin, R. 2003. Capture <strong>of</strong> koalas(Phascolarctos cinereus) by remote injection <strong>of</strong> tiletaminezolazapam(Zoletil) <strong>and</strong> metadomidine. Wildlife Research30: 255-258.Martin, R. W. 1989. Draft management plan for theconservation <strong>of</strong> the <strong>Koala</strong> (Phascolarctos cinereus) inVictoria. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental ResearchTechnical Report Series Number 99, <strong>Department</strong> <strong>of</strong>Conservation, Forests <strong>and</strong> L<strong>and</strong>s, Melbourne.Martin, R. <strong>and</strong> H<strong>and</strong>asyde, K. 1999. The <strong>Koala</strong>: NaturalHistory, Conservation <strong>and</strong> <strong>Management</strong>. University <strong>of</strong>New South Wales Press, Sydney.21