Preschool hearing, speech, language and vision ... - University of York

Preschool hearing, speech, language and vision ... - University of York

Preschool hearing, speech, language and vision ... - University of York

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

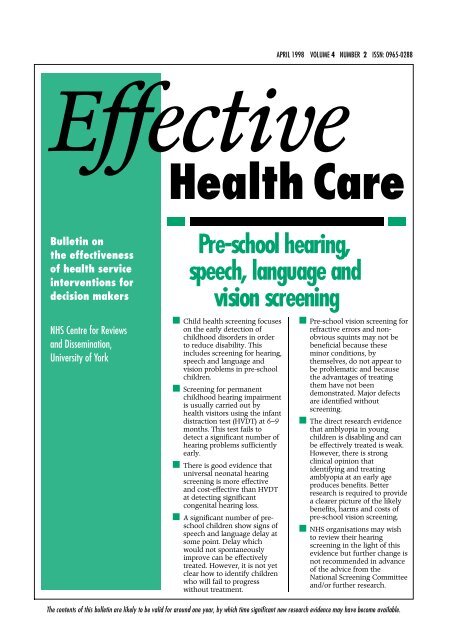

APRIL 1998 VOLUME 4 NUMBER 2 ISSN: 0965-0288EffectiveHealth CareBulletin onthe effectiveness<strong>of</strong> health serviceinterventions fordecision makersNHS Centre for Reviews<strong>and</strong> Dissemination,<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>,<strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>vision</strong> screening■ Child health screening focuseson the early detection <strong>of</strong>childhood disorders in orderto reduce disability. Thisincludes screening for <strong>hearing</strong>,<strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>vision</strong> problems in pre-schoolchildren.■ Screening for permanentchildhood <strong>hearing</strong> impairmentis usually carried out byhealth visitors using the infantdistraction test (HVDT) at 6–9months. This test fails todetect a significant number <strong>of</strong><strong>hearing</strong> problems sufficientlyearly.■ There is good evidence thatuniversal neonatal <strong>hearing</strong>screening is more effective<strong>and</strong> cost-effective than HVDTat detecting significantcongenital <strong>hearing</strong> loss.■ A significant number <strong>of</strong> preschoolchildren show signs <strong>of</strong><strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delay atsome point. Delay whichwould not spontaneouslyimprove can be effectivelytreated. However, it is not yetclear how to identify childrenwho will fail to progresswithout treatment.■ Pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screening forrefractive errors <strong>and</strong> nonobvioussquints may not bebeneficial because theseminor conditions, bythemselves, do not appear tobe problematic <strong>and</strong> becausethe advantages <strong>of</strong> treatingthem have not beendemonstrated. Major defectsare identified withoutscreening.■ The direct research evidencethat amblyopia in youngchildren is disabling <strong>and</strong> canbe effectively treated is weak.However, there is strongclinical opinion thatidentifying <strong>and</strong> treatingamblyopia at an early ageproduces benefits. Betterresearch is required to providea clearer picture <strong>of</strong> the likelybenefits, harms <strong>and</strong> costs <strong>of</strong>pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screening.■ NHS organisations may wishto review their <strong>hearing</strong>screening in the light <strong>of</strong> thisevidence but further change isnot recommended in advance<strong>of</strong> the advice from theNational Screening Committee<strong>and</strong>/or further research.The contents <strong>of</strong> this bulletin are likely to be valid for around one year, by which time significant new research evidence may have become available.

A. Pre-schoolscreeningChild health surveillance (CHS) ispart <strong>of</strong> a broad set <strong>of</strong> activitiesinitiated <strong>and</strong> provided bypr<strong>of</strong>essionals. The objective is toreduce childhood disability byidentifying <strong>and</strong> managing amultiplicity <strong>of</strong> conditions at anearly stage <strong>and</strong> by working withfamilies to promote child health<strong>and</strong> well-being. 1 CHS includes anumber <strong>of</strong> screening programmeswhich are focused on thedetection <strong>of</strong> specific disorders.CHS began as a series <strong>of</strong> activitieswhich tended to come together inan ad hoc manner. The value <strong>of</strong>surveillance <strong>and</strong> monitoring <strong>of</strong>child health, growth <strong>and</strong>development used to be regardedas self-evident. The Hall reportsemphasised the importance <strong>of</strong>applying rigorous criteria forscreening programmes incommunity child health <strong>and</strong>helped to produce a more coordinatednational programme. 2–4However, there is still significantvariation both within <strong>and</strong> betweenhealth authorities in the content,timing <strong>and</strong> delivery <strong>of</strong> CHS.This bulletin summarises theresearch evidence about <strong>hearing</strong>,<strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong>screening <strong>and</strong> is based on recentsystematic reviews commissionedby the NHS Health TechnologyAssessment Programme. Details<strong>of</strong> the methods <strong>and</strong> the results areavailable in the full reports. 5–7 Thisbulletin aims to provide easyaccess to this research intelligence,to promote informed debate <strong>and</strong>help decision makers.These three reviews focus on onlysome <strong>of</strong> the components <strong>of</strong> CHS<strong>and</strong>, within those parts, have notnecessarily examined all thedisorders being sought throughscreening. Some <strong>of</strong> the disabilitiesfor which children are screened inthe early years can exist alongsideone another <strong>and</strong> with otherswhich have not been reviewed,such as conductive <strong>hearing</strong> loss<strong>and</strong> developmental disability.Some important componentsremain to be scrutinised as doesthe value <strong>of</strong> the programme in itsentirety. Therefore, changes tocomponent parts <strong>of</strong> theprogramme should only be madeafter consideration has been givento the consequences <strong>of</strong> thesechanges to the programme overall.The Department <strong>of</strong> Health’sNational Screening Committee hasrecently established a sub-group toexamine neonatal <strong>and</strong> childhoodscreening <strong>and</strong> surveillance. Thiswill be making recommendationson the direction <strong>of</strong> futurescreening <strong>and</strong> surveillance. TheDepartment <strong>of</strong> Healthrecommends that no changes aremade to existing child healthscreening programmes until thiscommittee has reported <strong>and</strong>/orfurther research has beencompleted <strong>and</strong> considered.B. Evaluation<strong>of</strong> screeningThe objective <strong>of</strong> universalscreening in childhood is toidentify impairments which arenot obvious or apparent, whichwill cause significant disabilityor h<strong>and</strong>icap <strong>and</strong> for which earlytreatment is more effective.Screening does not includeTable 1 Major criteria for assessing a screening programmesituations in which potentialproblems are noticed <strong>and</strong> thenreferred for detailed evaluations.Screening uses considerableresources, <strong>and</strong> imposes tests onchildren who are not ill. Inaddition, it has been argued thatsome screening programmes couldbe potentially harmful due to theunnecessary worry, referrals <strong>and</strong>procedures which may result.There is, therefore, an ethicalresponsibility to ensure thatscreening is only carried out wherethere is confidence that it willresult in more good than harm. ‘Itis unethical to <strong>of</strong>fer screening testswhich cannot st<strong>and</strong> up to criticalexamination’. 4 A number <strong>of</strong> criteriaare helpful when consideringwhether or not to carry outscreening (Table 1). 8,9This rational approach toscreening is at odds withconventional views held by somepractising clinicians <strong>and</strong> parentsthat any disorders should bedetected early if possible. These<strong>of</strong>ten powerfully held views do notjustify the establishment ormaintenance <strong>of</strong> a screeningprogramme which is notsupported by the researchevidence. Ultimately, policydecisions have to be made byintegrating the available evidence,incomplete though it may be, <strong>and</strong>assessing the relative values <strong>of</strong>different opportunities to improvehealth. This needs to take accountDoes the screening programme do more good than harm<strong>and</strong> at acceptable cost?• Is the impairment sufficiently common to justify screening all children?• Does the impairment cause significant disability or h<strong>and</strong>icap?• Is there agreement about what is meant by a case?• Is there a screening test which accurately identifies children who may have an impairment?• Is there an agreed <strong>and</strong> available effective intervention with which to treat the impairment orreduce the disability after identification?• Is there an advantage in detecting <strong>and</strong>/or treating the impairment earlier, before it becomesclinically observable?• Is the cost <strong>of</strong> screening justified by the net benefit?2 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening APRIL 1998

<strong>of</strong> the fact that screeningprogrammes can also provideopportunities for healthpr<strong>of</strong>essionals to undertake otheractivities, for example, healthpromotion. The removal <strong>of</strong> specificactivities may unwittingly result inan overall loss <strong>of</strong> service withoutnecessarily resulting in acorresponding time or cost saving.In the final analysis, policy may bedriven by social or politicalconcerns, informed by thescientific evidence, <strong>and</strong> individualchoices made by parents afterhaving been adequately informedabout likely benefits <strong>and</strong> harms.Even when there is good evidenceto support a screening activity itsbenefits are only fully realised ifthe programme is well managed<strong>and</strong> there is quality assurance.This may be difficult since manychildhood screening programmesnow involve several NHS trusts<strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>essional groups <strong>and</strong> arealso undertaken in GP settings.Routine data collection is neededto monitor programmes in terms<strong>of</strong> coverage, sensitivity <strong>and</strong>specificity <strong>and</strong> the progress <strong>of</strong>those children screened positive –a requirement rarely met atpresent.C. HearingscreeningC.1 Epidemiology <strong>and</strong> naturalhistory <strong>of</strong> congenital <strong>hearing</strong>impairment: Approximately 840congenitally <strong>hearing</strong>-impairedchildren are born in the UK eachyear (1.12 per 1000 live births)with a permanent bilateralmoderate, severe or pr<strong>of</strong>ound<strong>hearing</strong> impairment <strong>of</strong> > 40dB<strong>hearing</strong> loss in the better ear. 10There are two types <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>impairment: sensorineural <strong>hearing</strong>loss (SNHL) caused by lesions inthe cochlea or auditory nerve <strong>and</strong>its central connections (unilateralor bilateral) <strong>and</strong> conductive <strong>hearing</strong>loss due to pathology <strong>of</strong> the middleear e.g. glue ear. The vast majority<strong>of</strong> permanent childhood <strong>hearing</strong>impairment is sensorineural,which does not resolve.Almost 85% <strong>of</strong> all permanentchildhood <strong>hearing</strong> impairment willbe present at birth with around160 cases a year being acquired(<strong>of</strong>ten following meningitis). Theimpact <strong>of</strong> permanent <strong>hearing</strong>impairment on children <strong>and</strong> theirfamilies can be considerable. Lateidentification may compoundproblems in communication,<strong>language</strong> acquisition <strong>and</strong> affectother areas <strong>of</strong> development.C.2 Screening tests: The mostcommon pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>screening test used in the UK isthe infant distraction test carriedout by two health visitors (HVDT),or by a health visitor <strong>and</strong> a trainedassistant (Table 2). It isadministered at about 6–9 months<strong>of</strong> age <strong>and</strong> assesses the infant’sability to turn <strong>and</strong> locate a soundsource. It is used as a universal<strong>hearing</strong> screen in about 98% <strong>of</strong>health districts <strong>and</strong> achievesTable 2 Key screening tests used to detect permanent childhood <strong>hearing</strong> impairmentTestsComments1 Infant distraction test (IDT)1a Traditional Health Visitor distraction test(HVDT) universal in most districtsTest carried out at 6–9 months, usually in protected time. Cost about £25 per test includingfollow-up a1b Targeted IDTProposed in t<strong>and</strong>em with universal neonatal screening on equity grounds1c BeST test New one person IDT, with calibrated sound source2 Transient Evoked Otoacoustic Emissions Quick test carried out within days <strong>of</strong> birth. Measures acoustic energy generated by the healthy(TEOAE)cochlea in response to wide b<strong>and</strong> clicks using a lightweight ear-canal probe. Cost £14 per test.Presently most used for well babies. Need agreed criteria for Pass/Refer3 MLS TEOAE New very quick version <strong>of</strong> TEOAE that may have advantages in noisy situations4 Distortion Product Otoacoustic Emissions Many implementations, need to monitor literature as to outcome(DPOAE)5 Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) Test carried out within days <strong>of</strong> birth. Wide b<strong>and</strong> clicks are presented to one ear <strong>and</strong> theresulting electrical potentials <strong>of</strong> the early auditory pathways are measured using surfaceelectrodes. Some ABR machines make pass or refer decisions, others need trained operators.High recurrent costs or long test times on some implementations. Presently most used inNICU/SCBU children6 Portable Auditory Response Cradle (PARC) Automated, quick, behavioural test which presents a 70–80dB SPL high pass noise to one orboth <strong>of</strong> the baby’s ears via an earphone or probe. The baby’s response is measured by acradle <strong>and</strong> associated computer s<strong>of</strong>tware which compares head turns <strong>and</strong> body movements inperiods with the sound on <strong>and</strong> <strong>of</strong>f. An automated decision algorithm is used to pass or refer.Probably good for severe <strong>and</strong> pr<strong>of</strong>ound impairmentsa The full cost <strong>of</strong> health visitor (HV) time does not allow for the fact that HVs may be visiting the home anyway. However, if done in conjunction withseveral other activities its accuracy <strong>and</strong> therefore its value is likely to be reduced.APRIL 1998Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE 3

coverage <strong>of</strong> about 90% <strong>of</strong> allinfants. This varies by socioeconomicstatus. There is alsovariability in the way it is carriedout, the sound generators used,the number <strong>and</strong> level <strong>of</strong> training <strong>of</strong>the people doing the testing, <strong>and</strong>the adequacy <strong>of</strong> soundpro<strong>of</strong>ing <strong>of</strong>the room. This leads to concernsabout the number <strong>of</strong> children withproblems who are not identifiedduring a screen under presentarrangements.The published evidence on testperformance from clinic-basedretrospective studies <strong>and</strong> case-notereviews indicates poor <strong>and</strong>variable sensitivity (detection rate)<strong>and</strong> specificity (true negative rate)for the HVDT. 5 The cumulativeyield is low, being about 50% by18 months <strong>of</strong> age. The average age<strong>of</strong> confirmation <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>impairment via the HVDT isbetween 12–20 months, withsubsequent age <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>-aidfitting following HVDT beingabout 18 months.Alternatively, a number <strong>of</strong>neonatal screening tests that canbe applied within the first few daysafter birth are available (Table 2).These methods include thePortable Auditory Response Cradle(PARC), the Auditory BrainstemResponse (ABR), <strong>and</strong> TransientEvoked Otoacoustic Emissions(TEOAE). TEOAE is currently thepreferred technique for wellbabies, <strong>and</strong> automated ABR forthose in neonatal intensive care orspecial care baby units. Althoughthe PARC has been extensivelytested, its implementation has notbeen as well evaluated in multicentrestudies as TEOAE.One controlled trial has beencarried out to compare screeningmethods. 11 This trial in Wessexcompared 21,000 babies givenTEOAE screening (ABR was usedfor those failing the test) with29,000 babies who received onlythe HVDT at 6–8 months. Interimresults show that the neonatalscreening test has a specificity <strong>of</strong>around 98% <strong>and</strong> gave a yield <strong>of</strong>1.1 per 1,000 births by 4 months<strong>of</strong> age. This corresponds to theexpected prevalence rate, thusindicating a high sensitivity. Thehigh specificity <strong>and</strong> sensitivity <strong>of</strong>the neonatal screen is confirmedby another UK longitudinalstudy. 12–14 The cumulative yield inthe HVDT-only group was lower at0.7 per 1,000 by 18 months oldsuggesting that false negatives willemerge later on. Only 0.1 <strong>hearing</strong>problems per 1000 births wereactually detected by the HVDTsince most were identified due toparental or pr<strong>of</strong>essional concern,or passed the HVDT incorrectly. Inthe neonatal screening group 96%were identified under 9 months <strong>of</strong>age compared to around half inthe HVDT-only group.In the UK, where universalneonatal screening programmeshave been implemented with goodcoverage alongside the HVDTscreen, the extra yield <strong>of</strong> theHVDT is very low (e.g. 0.1 per1000 births).C.3 Interventions for congenital<strong>hearing</strong> impairment:Interventions includeamplification, cochlear implants orhelping the child to learn anappropriate sign <strong>language</strong> (Table3). For children with a pr<strong>of</strong>oundimpairment a cochlear implantmay enable the auditory neuralpathway to be stimulated directly.This is currently being evaluatedby an MRC study.While there is a growing body <strong>of</strong>literature on the benefits <strong>of</strong> earlyintervention, few studies are <strong>of</strong>high quality. Three <strong>of</strong> the 18studies identified providereasonable evidence that earlyintervention is better than late. Ina study <strong>of</strong> 69 children identifiedby a Colorado neonatal screeningprogramme, those habilitatedbefore 3 months <strong>of</strong> age scored87% <strong>of</strong> normal for expressive<strong>language</strong>, compared to only 66%for those habilitated between 3<strong>and</strong> 12 months. 15 Similarly, in thesame study, 46 children whose<strong>hearing</strong> impairments wereidentified before the age <strong>of</strong> 6months were found to have better3-year vocabulary <strong>and</strong> expressive<strong>and</strong> receptive <strong>language</strong> than 63children whose impairment wasidentified after 6 months (afterhaving taken into account anydifferences in non-verbal cognitiveskills). 16 In another study,subjective assessments by teachers<strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong> intelligibility <strong>of</strong> 153children (matched for age, sex, age<strong>of</strong> onset <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong> loss, degree <strong>of</strong>deafness <strong>and</strong> schooling) found thatthose fitted with <strong>hearing</strong> aidsbefore 6 months achieved higherscores than any groups <strong>of</strong> childrenfitted with <strong>hearing</strong> aids later in life. 17The benefits <strong>of</strong> early identificationin <strong>hearing</strong>-impaired children aresupported by other studies whichshow earlier onset <strong>of</strong> babbling 18 orbetter communication skills 19,20 theearlier the children were fittedwith <strong>hearing</strong>-aids. One study,however, found that the initialbenefits <strong>of</strong> early intervention onreceptive <strong>language</strong> did notpersist. 21Overall, this research supports theview that these children(particularly those with moresevere impairments) have verypoor outcomes at presentcompared with normal-<strong>hearing</strong>children. Earlier identification isassociated with better outcomes,particularly in the domain <strong>of</strong><strong>language</strong> acquisition <strong>and</strong>communication. However, theextent to which even betteroutcomes may be achieved withvery early identification is not yetclear, although the early researchresults from Colorado point to thisbeing the case. 16C.4 Cost-effectiveness: There is asignificant difference in the cost <strong>of</strong>neonatal <strong>and</strong> HVDT screeningapproaches. The cost (includingfollow up) for universal neonatalscreening programmes is about£14,000 per 1,000 births; forHVDT it is about £25,000 per1,000 children, when done inprotected time or on a separatevisit. 22 This translates into a ‘costper child with a <strong>hearing</strong> problemidentified’ <strong>of</strong> around £17,000 forneonatal screening <strong>and</strong> £80,000for HVDT screening. These figuresdo not take into account any <strong>of</strong>the benefits to the child <strong>of</strong> earlier4 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening APRIL 1998

Table 3 Key interventions for moderate to pr<strong>of</strong>ound permanent childhood <strong>hearing</strong> impairment <strong>and</strong> ways they will be affected if UniversalNeonatal Screening is introducedInterventionFamily support, advice <strong>and</strong> informationPro<strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong> aidsPro<strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> communication support(spoken <strong>and</strong>/or signed)Pro<strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> pre-school educational supportCochlear implantsPro<strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> other devices e.g. radio aids,tactile aids, other assistive devicesEffect <strong>of</strong> Universal Neonatal ScreeningNeeds to be effective from screen refer <strong>and</strong> onwards. Requires better multi-agencyco-operationBetter early diagnostic testing <strong>and</strong> aid fitting. Requires evaluations for mild impairments if thescreen is to be extended to this groupEarlier support neededEarlier support needed. Different skill mix needed for children in first 18 monthsEarlier implantation will be possibleNo effectdetection <strong>and</strong> habilitation nor theextra costs <strong>of</strong> the earlier treatment<strong>and</strong> educational support whichthey will receive with neonatalscreening. Conversely, it does nottake into account other healthpromotion activities which may beundertaken by health visitors atthe same contact. However, in themajority <strong>of</strong> districts, <strong>hearing</strong> testsare carried out by health visitors inseparate clinics or during protectedtime. Therefore, many healthauthorities will be able to free someresources in moving from HVDT touniversal neonatal <strong>hearing</strong> screeningas well as improve the service.Approximately two-thirds <strong>of</strong>districts have some sort <strong>of</strong>neonatal <strong>hearing</strong> screeningprogramme: two have universalneonatal screening <strong>and</strong> theremainder target babies with oneor more risk factors for <strong>hearing</strong>impairment. Because this meansscreening fewer but higher riskbabies, targeted screening is morecost-effective at around £14,000per case detected. However, onlyabout 50–60% <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>-impairedchildren will have risk factors <strong>and</strong>in practice the yield will be lower. 5,22childhood 23 with a prevalence <strong>of</strong>around 6% <strong>of</strong> children. Thedem<strong>and</strong> for services, particularlyfor children under 4 years <strong>of</strong> age,is increasing. 24,25 Since the agedistribution at which ‘normal’children learn to speak is probably‘bell-shaped’, prevalence estimatesare dependent to a great extent onthe cut-<strong>of</strong>f point used. Few dataare available on bilingual orethnically diverse groups <strong>and</strong> theassociation with social class is alsounclear.Spontaneous remission <strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delays identified inthe pre-school period can be high,particularly for children withspecific expressive delays, wheresome 60% <strong>of</strong> cases may resolvewithout treatment by 3 years <strong>of</strong>age. 6 The picture for older childrenis unclear because <strong>of</strong> a lack <strong>of</strong>research, but it is evident that ifchildren go on to have difficultiesin the first year <strong>of</strong> primary school,they are at risk <strong>of</strong> experiencingproblems throughout theirschooling. In addition, 41–75% <strong>of</strong>children who present with earlyexpressive <strong>language</strong> delay werefound to exhibit readingdifficulties at 8 years <strong>of</strong> age.Risk factors for persistent problemsinclude the initial severity <strong>of</strong> thedelay, the extent to which thedifficulties are generalised across<strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong>, <strong>and</strong> theTable 4 Principal methods <strong>of</strong> screening for <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delay• Level <strong>of</strong> concern elicited from parent by a pr<strong>of</strong>essional (the Parental Evaluation <strong>of</strong>Developmental Status)• Parent provides information about <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> milestones <strong>and</strong> the clinicianinterprets the results (the Early Language Milestone Scale, the Clinical Linguistic AuditoryMilestone Scale)• Parent reports on child’s current level <strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong>/<strong>language</strong> functioning <strong>and</strong> the clinicianinterprets the results (e.g. the Minnesota Child Development Inventory, the Ward InfantLanguage Screening Test, the Language Development Survey)• Clinician makes a judgement <strong>of</strong> child’s performance based on mixed observation/reportedD. Speech <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> delayD.1 Epidemiology <strong>and</strong> naturalhistory <strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong>delay: Speech <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delayis one <strong>of</strong> the most common neurodevelopmentaldifficulties in earlydata (The Denver Developmental Screening Test)• Clinician tests child’s <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> performance by means <strong>of</strong> specific activitiessuch as:the child’s response to requests graded in terms <strong>of</strong> difficulty (e.g. the Hackney LanguageScreening Test, the Mayo Early Language Screening Test, the Uppsala General LanguageScreening)the child’s capacity to imitate words <strong>and</strong> sentences (Sentence Repetition Screening Test)the child’s capacity to retell storiesAPRIL 1998 Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE 5

extent to which other cognitive<strong>and</strong> developmental skills are alsodelayed. The extent to whichfactors such as social class, familyhistory, temperament <strong>and</strong> gendercontribute to relative risk is unclear.However, there is reasonableevidence to suggest that <strong>speech</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> development areaffected by how well parentsinteract verbally with their children<strong>and</strong> by the general level <strong>of</strong>stimulation within the homeenvironment. However, it isuncertain whether parental factorscan actually create a ‘clinical’ level<strong>of</strong> difficulty.D.2 Screening tests: Severalscreening measures are used in theUK (Table 4). No r<strong>and</strong>omisedcontrolled trials (RCTs) <strong>of</strong>screening programmes wereidentified by the review. Screeningtest performance variesconsiderably with sensitivitywithin the range 17–100% <strong>and</strong>specificity in the range 43–100%.Sensitivity was generally lowerthan specificity, particularly in thebetter-quality studies. Thissuggests that it may be easier toindicate those children who arenot cases than to be clear aboutthose who are. Few studies haveattempted to compare theapplication <strong>of</strong> two or morescreening tests to a singlepopulation or to compare a singlescreening measure across differentpopulations. It is, therefore,difficult to make a judgementabout the relative value <strong>of</strong> differentprocedures or to single out anyone measure as outperforming theothers. In general, however, screensthat used parents as informantswere as accurate as those thatused formal testing procedures.The majority <strong>of</strong> the screeningprocedures currently available areapplicable after the age <strong>of</strong> 2 yearswhen the reported accuracy <strong>of</strong>screening is greater. However,work currently in progress isexploring a method <strong>of</strong> identifyingthose at risk <strong>of</strong> subsequentdifficulties based on auditory skillsat 9 months old. 26 Given thevariability in the natural history <strong>of</strong><strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delay, <strong>and</strong>the high level <strong>of</strong> subsequentspontaneous improvement,particularly in the very early years,the use <strong>of</strong> a single measure at thisstage in a child’s development isunlikely to be valuable. Tests thatcan identify those children whowill fail to progress withouttreatment need to be developed.D.3 Interventions for <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> delay: Several types <strong>of</strong>interventions have been used forhelping children with <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> delays (Table 5). TenRCTs <strong>and</strong> 12 controlled studieswere identified which evaluatedtreatment, mostly for problems <strong>of</strong>articulation/phonology <strong>and</strong>expressive <strong>language</strong>. 27–45These studies show thatinterventions are effective inenhancing <strong>speech</strong>, expressive<strong>language</strong>, receptive <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong>auditory discrimination, relative tountreated controls. The size <strong>of</strong> thebenefits represented progress fromthe 5th to the 25th percentile on anorm-referenced test. ThisTable 5 Key intervention approaches for <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delaycorresponds to an overallst<strong>and</strong>ardised effect size <strong>of</strong> around1.0 – an increase in the averageperformance equivalent to 1st<strong>and</strong>ard deviation <strong>of</strong> thedistribution <strong>of</strong> performance scores.These results are supported bydata from 26 single-caseexperimental designs. 6 No studiesspecifically compared the effects <strong>of</strong>different timing <strong>of</strong> interventionson social <strong>and</strong> educational outcomes<strong>and</strong> there are little reliable datawith which to identify the bestchoice for any area <strong>of</strong> delay.One <strong>of</strong> the interesting issues iswho most effectively provides theinterventions: pr<strong>of</strong>essionals (i.e.<strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> therapists orspecialist teachers) orparents/others in the child’senvironment. Studies have showncomparable results for both in thecase <strong>of</strong> expressive <strong>language</strong> (effectsize from 0.65–1.11 <strong>and</strong> 1.08–1.16for pr<strong>of</strong>essionals <strong>and</strong> parentsrespectively). In <strong>speech</strong> delay,pr<strong>of</strong>essionals (effect size from0.94–1.11) were more effectiveThe majority <strong>of</strong> interventions are primarily behavioural in nature <strong>and</strong> may be provided by<strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> therapists or specialist teachers, either intensively within a specialist unitor less intensively, but at regular intervals, in a clinical setting, a school or a day care setting.The three main intervention types are:Didactic interventionThe child is given a model <strong>of</strong> a sound, a word, a communication behaviour or a syntacticconstruction <strong>and</strong> an attempt made to elicit the child’s production <strong>of</strong> that model using positivereinforcement. This approach is usually carried out by the therapist or teacher.Naturalistic interventionThis approach recreates the environment which is known to optimise the child’s <strong>language</strong>learning opportunities, not through explicit instruction, but by making the stimulus relevant to thechild’s focus <strong>of</strong> attention. This approach is aimed at promoting the acquisition <strong>and</strong>generalisation <strong>of</strong> functional <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> frequently involves parents as active participants. Itcan be carried out directly by a therapist or teacher or indirectly by others in the child’senvironment.Hybrid interventionThis approach combines elements <strong>of</strong> both didactic <strong>and</strong> naturalistic interventions. It recognisesthat children with delayed <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> development may learn <strong>language</strong> in differentways from one another <strong>and</strong> from their normal peers, <strong>and</strong> may need to be exposed to a range<strong>of</strong> different types <strong>of</strong> environmental modifications.Other intervention approaches include non-directive therapy, auditory training,comprehension monitoring <strong>and</strong> cognitive therapy.6 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening APRIL 1998

than parents (-0.02 to 0.20). In the No studies were found whichcase <strong>of</strong> receptive <strong>language</strong> the aimed to document the naturalreverse was found – treatment history <strong>of</strong> these conditions inprovided by parents or other untreated pre-school children. Acarers on the advice <strong>of</strong> afew studies, however, give somepr<strong>of</strong>essional following diagnosis or information on what would beassessment was more effective expected to happen to the <strong>vision</strong>(average effect size <strong>of</strong> 1.43) <strong>of</strong> children at this age withcompared with direct intervention amblyopia, 56 squints, 57,58 <strong>and</strong>(average effect size <strong>of</strong> 0.02). refractive errors 59 in the absence <strong>of</strong>intervention. These suggest thatD.4 Cost-effectiveness: No costeffectivenessstudies have examined to non-cosmetically obviousamblyopia in some children (duethe impact <strong>of</strong> screening programmes squints or mild refractive error at 3in terms <strong>of</strong> possible savings in or 4 years) may resolve withoutspecial education <strong>and</strong> other support treatment. However, there areservices provided. One study is many important gaps in the data.currently underway at Erasmus<strong>University</strong>, Rotterdam. There is, Twenty-one studies were foundhowever, evidence from the US which aimed to investigate whetherwhich suggests that home-based a variety <strong>of</strong> disabilities wereintervention may be more costeffective.46 Given the positive effects target conditions. The majority <strong>of</strong>associated with any <strong>of</strong> the three<strong>of</strong> indirect intervention identified studies compared the performancein this bulletin, this needs to be <strong>of</strong> children with visual defects inexamined more closely in the UK tasks such as reading with that <strong>of</strong>context.their peers with normal <strong>vision</strong>, orcompared the <strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> childrenwith <strong>and</strong> without disabilities suchas dyslexia. The only strong <strong>and</strong>consistent relationship to emergeE. Pre-schoolis that children with myopiaperform better than their peers on<strong>vision</strong> screeningreading tests, (although this is notdue to myopia enhancing childE.1 Epidemiology <strong>and</strong> naturaldevelopment).history <strong>of</strong> asymptomatic <strong>vision</strong>60–63 Studies thatinvestigated the relationshipproblems: The aim <strong>of</strong> <strong>vision</strong>between squints <strong>and</strong> readingscreening at the age <strong>of</strong> 3–4 years isability produced inconsistentthe prevention or reduction <strong>of</strong>findings.disability due to one or more <strong>of</strong>64–67 However, childrenwith squints have been found tothe following target conditions:perform less well than their peersamblyopia (reduced visual acuity,without squints in neurodevelopmentaltests.usually in one eye, in the absence<strong>of</strong> organic disease which cannot68–70be improved by spectacles),Amblyopia in one eye can disruptrefractive errors, <strong>and</strong> the typesdepth perception, but the effects<strong>of</strong> squints which are not cosmeticallythat this might have are poorlyobvious <strong>and</strong> so are unlikely to beunderstood <strong>and</strong> are currently thedetected without screeningsubject <strong>of</strong> debate.(phorias <strong>and</strong> microsquints).71–73 The onlystudy found which investigatedthe perceptual difficultiesNo studies were found which hadassociated with amblyopia inthe primary aim <strong>of</strong> establishing theadulthood suggested thatprevalence <strong>of</strong> visual defects at 3–4amblyopia in one eye had littleyears <strong>of</strong> age. However, data fromimpact on perception <strong>of</strong> space orstudies <strong>of</strong> primary orthopticcontrast <strong>and</strong> was unlikely to affectscreening programmes for this ageeveryday life, although this studygroup reported a range <strong>of</strong> yieldswas methodologically flawed.for the target conditions <strong>of</strong>74 Nostudies have been carried out2.4–6.1%. 47–55 using a design which is appropriatefor establishing a causal link.Physiological data from animalstudies showed that blurred <strong>vision</strong>at a critical stage <strong>of</strong> neurologicaldevelopment could result inpermanent impairment <strong>of</strong> therelevant brain functions. This gaverise to the enthusiasm for earlydetection <strong>of</strong> amblyopia. However,the quality <strong>of</strong> the literature onvisual defects <strong>and</strong> disability, <strong>and</strong>on the natural history <strong>of</strong> theseconditions in humans, isinsufficient to know with anycertainty what might be expectedto happen in an individual childwith amblyopia, a noncosmeticallyobvious squint or arefractive error if they were leftuntreated. One large RCT in Avoncomparing <strong>vision</strong> screeningprogrammes in children agedunder 3 should provide usefulinformation on associateddisability in older children. 75 Thereis a very strong pr<strong>of</strong>essional view,however, that amblyopia isdisabling <strong>and</strong> should be treated.E.2 Screening tests: The principalaim <strong>of</strong> the child screening test is toidentify children with amblyopia.However, tests are also carried outfor non-cosmetically obvioussquints <strong>and</strong> refractive errorsbecause these may be associatedboth with amblyopia <strong>and</strong> alsosometimes with the aim <strong>of</strong> treatingthem in their own right (Table 6).No RCTs <strong>of</strong> screening programmesfor the 3–4 year age group wereidentified. One prospectivecontrolled study was found, whichcompared visual outcomes at theage <strong>of</strong> 7 years in children whowere screened at age 3 byorthoptists, general practitioners orhealth visitors in Newcastle. 56Children with straight-eyedamblyopia <strong>and</strong> refractive errorswere identified significantly earlierin the orthoptic screening cohort,but there was no difference in thetime <strong>of</strong> identification <strong>of</strong> obvioussquint. Despite the fact that manymore children with amblyopiawere identified <strong>and</strong> treated in theorthoptic screening cohort, theprevalence <strong>of</strong> amblyopia at 7 years<strong>of</strong> age was the same in all threecohorts. 56 However, this study hascertain methodologicalweaknesses.APRIL 1998Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE 7

Table 6 Common contents <strong>of</strong> pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screeningCommon pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screening tests• Checking the appearance <strong>of</strong> the eyes• Cover/uncover test for squint• Single optotype or linear visual acuity test e.g. Sheridan Gardiner or SnellenAdditional tests performed in primary orthoptic screen• Ocular movements• Convergence• Prism test• Test <strong>of</strong> stereoacuity e.g. Fisby or Lang stereotestSixteen other studies that aimedto establish the effectiveness <strong>of</strong>pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screening wereeither observational or audits. 47–50,52–55, 76–83Uptake rates for primaryorthoptic screening ranged fromaround 44–80%. Vision screeningby health visitors, generalpractitioners or clinical medical<strong>of</strong>ficers, undertaken as part <strong>of</strong> aroutine surveillance contact, had amean uptake rate <strong>of</strong> 76.2%. Rates<strong>of</strong> referral from primary orthopticscreening programmes rangedfrom 4.1–10.6% <strong>of</strong> the screenedpopulation, with no differencesbetween the various healthpr<strong>of</strong>essional groups.In five studies <strong>of</strong> orthopticscreening programmes, thepositive predictive value, (thepercentage <strong>of</strong> those referred whoare true positives) varied from47–66%. 47, 51–53, 55 Positive predictivevalues <strong>of</strong> over 90% were achievedwhere the definition <strong>of</strong> a positivecase was more broad. 48, 49, 54 Inprogrammes run by health visitorsor clinical medical <strong>of</strong>ficers, thepositive predictive value was muchmore variable, ranging from14–62%. 47, 49, 51, 80, 81 In other words,orthoptists are generally better atidentifying these problems th<strong>and</strong>octors or health visitors. Asignificant number <strong>of</strong> areas useorthoptists (usually on a separateoccasion) to test for visualproblems around 3–4 years <strong>of</strong> age.E.3 Interventions for <strong>vision</strong>problems: The treatments foramblyopia include patching thenon-amblyopic eye <strong>and</strong> spectaclecorrection <strong>of</strong> associated refractiveerror, <strong>and</strong> surgery to correctsquints (Table 7). Five prospectiveRCTs <strong>of</strong> treatment <strong>and</strong> six non-RCTs were found. None werespecifically relevant to this agegroup <strong>and</strong> in no study was thetreatment compared to anuntreated control group, <strong>and</strong> thusthe absolute effects <strong>of</strong> treatmentare not known.Three <strong>of</strong> the RCTs compared theeffect <strong>of</strong> the CAM, (a <strong>vision</strong>stimulator grating) withconventional orthoptic treatment<strong>and</strong> showed no significantadvantage. 84-86 One small RCTshowed that adding the druglevodopa/carbidopa to orthoptictreatment for amblyopia improvedvisual acuity <strong>and</strong> contrastsensitivity. However at one monththe intervention group hadregressed slightly <strong>and</strong> the controlgroup had not maintainedimprovement. 87 This latter findingis supported by a controlled studycomparing different occlusionTable 7 Treatments for visual problems identified at pre-school screen• Amblyopia: intermittent occlusion <strong>of</strong> the non-amblyopic eye with a patch• Intermittent squints: followed up <strong>and</strong> may be treated with surgery if they deteriorate• Latent squints with hypermetropia (long sighted): <strong>of</strong>ten spectacle correction only• Microsquints <strong>and</strong> latent squints without hypermetropia: not treated• Refractive errors: left untreated or corrected by spectacles depending on severity <strong>and</strong>whether associated with amblyopiaregimes, in which 33% <strong>of</strong> thosewith improved acuity after treatmentshowed some deterioration after 3months. 88 Drugs <strong>and</strong> CAM are nowrarely used in the UK.Five controlled trials compareddifferent approaches to amblyopiatreatment. 88–92 All <strong>of</strong> these havemethodological flaws which limitthe value <strong>of</strong> their findings. Overall,whilst there is evidence that the<strong>vision</strong> <strong>of</strong> children with amblyopiaimproves with treatment, 84–92 theseimprovements may not be84, 86–88sustained.Seven studies evaluating screeningprogrammes reportedimprovements in visual acuity <strong>of</strong>two or more Snellen lines in50–80% <strong>of</strong> children who weretreated for amblyopia followingscreening. 47, 48, 50, 53, 55, 56, 93 However, asnone <strong>of</strong> these have a comparisongroup <strong>of</strong> untreated children, it isdifficult to assess the degree towhich these changes areattributable to treatment. None <strong>of</strong>the studies assessed long-termoutcomes <strong>of</strong> treatment, evaluatedtreatment in terms <strong>of</strong> disability orother patient-perceived outcomes.In addition, none <strong>of</strong> the studiesassessed the potential negativeimpact <strong>of</strong> orthoptic treatment(such as patching) on children ortheir families, which has beensuggested by recent qualitativework. 94An RCT 95 <strong>and</strong> a non-RCT 96 foundthat the use <strong>of</strong> pre-operative prismcorrection improved the outcome<strong>of</strong> squint surgery. However, thesetrials only included patients withobvious squints. No controlledstudies <strong>of</strong> treatment for latent ormicro-squints were found.Spectacles are a highly effectiveway <strong>of</strong> correcting refractive errorsthat requires no evaluation inolder children. However, thetreatment <strong>of</strong> refractive error in theabsence <strong>of</strong> amblyopia or manifestsquint is <strong>of</strong> unproven benefit <strong>and</strong>may even cause harm byinhibiting the normal refractivedevelopment <strong>of</strong> the eye(emmetropisation). 97 APRIL 19988 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening

F. ImplicationsThis bulletin has summarised arange <strong>of</strong> important new researchon three <strong>of</strong> the component parts<strong>of</strong> the child health surveillanceprogramme. The three individualscreening tests must be seen inthe context <strong>of</strong> an overall childhealth programme which, aswell as screening for specifichealth problems, also providesother health care, advice <strong>and</strong>support for families <strong>of</strong> youngchildren. These individualscreening programmes should,therefore, not be seen in isolation.F.1 Hearing screening: Currentservices are seen by parents <strong>and</strong>pr<strong>of</strong>essionals alike as poorly coordinated<strong>and</strong> fragmented. 5 Asmany as 200 <strong>of</strong> the 840 childrenper year born with significant<strong>hearing</strong> impairment may not beidentified until after 3 1 /2 years <strong>of</strong>age. On the grounds <strong>of</strong> equity,responsiveness <strong>and</strong> costeffectiveness,the transition fromuniversal HVDT to universalneonatal <strong>hearing</strong> screening, incombination with targeted InfantDistraction Tests, is considered thebest value for money. Some healthauthorities will be able to freesome resources in moving fromHVDT to universal neonatal<strong>hearing</strong> screening, as well asimprove the service.These results are currently beingconsidered by the NationalScreening Committee inconjunction with plans forimplementation, training <strong>and</strong>quality assurance. This shouldinclude quality markers such asinitial coverage, sensitivity forcongenital <strong>hearing</strong> impairment,<strong>and</strong> a maximum false-positive rate,<strong>and</strong> indicate relevant data to becollected. There will be a need fordevelopment <strong>and</strong> co-ordination<strong>of</strong> audiological follow-up services<strong>and</strong> the ongoing audiological <strong>and</strong>educational care <strong>of</strong> pre-school<strong>and</strong> school-aged <strong>hearing</strong>-impairedchildren, many <strong>of</strong> whom mayhave other <strong>and</strong>/or complexneeds. 10F.2 Speech <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delay:There are insufficient dataavailable to recommend theintroduction <strong>of</strong> populationscreening for early <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> delay because there isnot yet adequate agreement as towhich children will not progressunless they are given intervention<strong>and</strong> on the grounds that the currentscreening measures themselveshave yet to be shown to haveadequate predictive validity.Nonetheless, early primary <strong>speech</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> delay should remaina cause for concern. This isbecause <strong>of</strong> the problems it maypose for the individual child, theconcern it causes parents, the factit may serve as a litmus test forother problems which commonlyaccompany it such as cognitiveimpairment, behaviour <strong>and</strong>conduct disorders, <strong>and</strong> because <strong>of</strong>the implications that it may havefor literacy <strong>and</strong> socialisation inschool. However, furtherrefinement <strong>of</strong> screening measures,with accompanying research, isneeded before universal screeningis recommended. There is also acase for the evaluation <strong>of</strong> primaryprevention programmes aimed atreducing the risk <strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> delay. Research shouldexamine interventions whichencourage parents to read withtheir children (e.g. Bookstart) <strong>and</strong>teach parents to listen to <strong>and</strong>respond appropriately to theirchild’s communication attempts.F.3 Pre-school <strong>vision</strong> screening:Amblyopia can cause a significantreduction in visual acuity, asmeasured by the Snellen test, butthis may not be the best outcomemeasure. Equally, the physical,psychological <strong>and</strong> social implications<strong>of</strong> reduced visual acuity in one eyeare not well understood. Thus it isnot clear that amblyopia should beseen as the cause <strong>of</strong> significantdisability or h<strong>and</strong>icap. No studyhas addressed adequately thepossible negative aspects <strong>of</strong>amblyopia treatment. Furtherresearch is needed to ascertainboth the importance <strong>of</strong> thiscondition <strong>and</strong> the most effective<strong>and</strong> acceptable treatment.Pre-school screening for refractiveerrors <strong>and</strong> non-obvious squint,without associated amblyopia,does not seem to be justified sincethese conditions do not appear tobe problematic by themselves <strong>and</strong>their treatment at an asymptomaticstage has not been shown to conferbenefit. The fact that existingresearch fails to show that screeningfor, <strong>and</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong>, amblyopiaare beneficial is not however pro<strong>of</strong>that a screening <strong>and</strong> treatmentprogramme confers no benefit.Research is needed to establishwhether pre-school screening is <strong>of</strong>benefit. Pending further research,<strong>and</strong> the recommendations <strong>of</strong> theNational Screening Committee, itwould seem inappropriate toinitiate new programmes, orextend or dismantle existing ones.Given the current uncertainty overthe potential benefits <strong>and</strong> harms <strong>of</strong>testing <strong>and</strong> some correctivemeasures, it is particularly importantthat pr<strong>of</strong>essionals give adequate<strong>and</strong> accurate information to parents.References1. Hall D, Hill P, Elliman D. The childsurveillance h<strong>and</strong>book. 2nd edn.Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1994.2. Hall DMB. Health for all children:a programme for child healthsurveillance; the report <strong>of</strong> the JointWorking Party on Child HealthSurveillance. 1st edn. Oxford: Oxford<strong>University</strong> Press, 1989.3. Hall DMB. Health for all children: aprogramme for child healthsurveillance: the report <strong>of</strong> the JointWorking Party on Child HealthSurveillance. 2nd edn. Oxford:Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press, 1992.4. Hall DMB. Health for all children. Thereport <strong>of</strong> the Joint Working Party onChild Health Surveillance. 3rd edn.Oxford: Oxford <strong>University</strong> Press, 1996.5. Davis A, Bamford J, Wilson I, et al.A critical review <strong>of</strong> the role <strong>of</strong>neonatal <strong>hearing</strong> screening in thedetection <strong>of</strong> congenital <strong>hearing</strong>impairment. Health Technol Assess1997;1(10).6. Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, et al.Screening for <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong>delay: a systematic review <strong>of</strong> theliterature. CRD Report No 12.<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>: NHS Centre forReviews <strong>and</strong> Dissemination, 1998.APRIL 1998 Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE 9

7. Snowdon SK, Stewart-Brown SL.<strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening: results <strong>of</strong> asystematic review. CRD Report No. 9.<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>: NHS Centre forReviews <strong>and</strong> Dissemination, 1997.8. Wilson JMG, Jungner G. Principles<strong>and</strong> practice <strong>of</strong> screening for disease.Geneva: World Health Organisation,1968.9. Cochrane A, Holl<strong>and</strong> W. Validation<strong>of</strong> screening procedures. Br Med Bull1971;27:3–8.10. Fortnum H, Davis A. Epidemiology <strong>of</strong>permanent childhood <strong>hearing</strong> impairmentin Trent Region 1985–1993.Br J Audiol 1997;31:409–46.11. Hunter MF, Kimm L, Cafarelli DeesD, et al. Feasibility <strong>of</strong> otoacousticemission detection followed by ABRas a universal neonatal screening testfor <strong>hearing</strong> impairment. Br J Audiol1994;28:47–51.12. Watkin PM. Neonatal otoacousticemission screening <strong>and</strong> theidentification <strong>of</strong> deafness. Arch DisChild 1996;74:F16–F25.13. Watkin PM. Optimising the specificity<strong>of</strong> a neonatal otoacoustic emissionscreen. Unpublished report, 1996.14. Watkin PM. Outcomes <strong>of</strong> neonatalscreening for <strong>hearing</strong> loss byotoacoustic emissions. Arch Dis Child1996;75:F158–68.15. Downs MP. Universal newborn<strong>hearing</strong> screening – the Coloradostory. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol1995;32:257–9.16. Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey A, ApuzzoM, et al. The effect <strong>of</strong> earlyidentification on the development <strong>of</strong>deaf <strong>and</strong> hard-<strong>of</strong>-<strong>hearing</strong> infants <strong>and</strong>toddlers. Paediatrics 1998; in press.17. Markides A. Age at fitting <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>aids <strong>and</strong> <strong>speech</strong> intelligibility. Br JAudiol 1986;20:165–7.18. Eilers RE, Oller DK. Infantvocalisations <strong>and</strong> the early diagnosis<strong>of</strong> severe <strong>hearing</strong> impairment. JPediatr 1994;124:199–203.19. Ramkalawan TW, Davis AC. Theeffects <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong> loss <strong>and</strong> age <strong>of</strong>intervention on some <strong>language</strong>metrics in young <strong>hearing</strong>-impairedchildren. Br J Audiol 1992;26:97–107.20. Ramkalawan TW. Factors thatinfluence the <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong>communication <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong> impairedchildren. Unpublished. PhD thesis,1997.21. Musselman CR, Wilson AK, LindsayPH. Effects <strong>of</strong> early intervention on<strong>hearing</strong> impaired children. ExceptChild 1988;55:222–8.22. Stevens JC, Hall DMB, Davis A, et al.A survey <strong>of</strong> the costs <strong>of</strong> <strong>hearing</strong>screening in the first year <strong>of</strong> life inEngl<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> Wales. Arch Dis Child1998;78:14–19.23. Drillien C, Drummond M.Developmental screening <strong>and</strong> thechild with special needs. London:Heinemann, 1983.24. Jowett S, Evans C. Speech <strong>and</strong><strong>language</strong> therapy services for children.Slough: NFER, 1996.25. Reid J, Millar S, Tait L, et al. Pupilswith special education needs: the role<strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong> therapists.Edinburgh: SCER, 1996.26. Ward S, Birkett D. The Ward InfantLanguage Screening Test, assessment,acceleration <strong>and</strong> remediation.Manchester: Manchester Health CareTrust, 1994.27. Almost D, Rosenbaum P.Effectiveness <strong>of</strong> <strong>speech</strong> interventionfor phonological disorders: ar<strong>and</strong>omised controlled trial.Unpublished, 1997.28. Conant S, Bud<strong>of</strong>f M, Hecht B, et al.Language intervention: a pragmaticapproach. J Autism Dev Disord1984;14:301–17.29. Fey ME, Cleave PL, Long SH, et al.Two approaches to the facilitation <strong>of</strong>grammar in children with <strong>language</strong>impairment: an experimentalevaluation. J Speech Hear Res1993;36:141–57.30. Fey ME, Cleave PL, Ravida AI, et al.Effects <strong>of</strong> grammar facilitation on thephonological performance <strong>of</strong>children with <strong>speech</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>language</strong>impairments. J Speech Hear Res1994;37:594–607.31. Gibbard D. Parental-basedintervention with pre-school<strong>language</strong>-delayed children. Eur JDisord Commun 1994;29:131–50.32. Girolametto L, Pearce PS, WeitzmanE. Interactive focused stimulation fortoddlers with expressive vocabularydelays. J Speech Hear Res1996;39:1274–83.33. Girolametto L, Pearce PS, WeitzmanE. The effects <strong>of</strong> focused stimulationfor promoting vocabulary in youngchildren with delays: a pilot study. JChild Commun Dev 1995;17:39–49.34. Lancaster G. The effectiveness <strong>of</strong>parent administered input trainingfor children with phonologicaldisorders. MSc Thesis. London: City<strong>University</strong>, 1991.35. Matheny N, Panagos JM. Comparingthe effects <strong>of</strong> articulation <strong>and</strong> syntaxprograms on syntax <strong>and</strong> articulationimprovement. Lang Speech Hear Servin School 1978;9:57–61.36. McDade A, McCartan PA.Partnership with parents: a pilotstudy. Unpublished, 1996.37. Reid J, Donaldson ML, Howell J, et al.The effectiveness <strong>of</strong> therapy for childphonological disorder. TheMetaphon approach. In: Aldridge M(ed.). Child Language. Clevedon,Avon: Multilingual Matters,1996:165–75.38. Schwartz RG, Chapman K, Terrell BY,et al. Facilitating word combinationin <strong>language</strong>-impaired childrenthrough discourse structure. J SpeechHear Disord 1985;50:31–9.39. Shelton RL, Johnson AF, RuscelloDM, et al. Assessment <strong>of</strong> parentadministeredlistening training forpreschool children with articulationdeficits. J Speech Hear Disord1978;43:242–54.40. Stevenson P, Bax M, Stevenson J. Theevaluation <strong>of</strong> home-based <strong>speech</strong>therapy for <strong>language</strong> delayedpreschool children in an inner cityarea. Br J Disord Commun1982;17:141–8.41. Ward S. Validation <strong>of</strong> a treatmentmethod. In the proceedings <strong>of</strong> the2nd Conference <strong>of</strong> the ComitePermanente de Liaison desOthophonistes-Logopedes del’UE[CPLOL], Antwerp, 1994.42. Warrick N, Rubin H, Rowe-Walsh S.Phoneme awareness in <strong>language</strong>delayedchildren: comparativestudies <strong>and</strong> interventions. AnnDyslexia 1993;43:153–73.43. Whitehurst GJ, Fischel JE, LoniganCJ, et al. Treatment or earlyexpressive <strong>language</strong> delay: if, when,<strong>and</strong> how. Top Lang Disord1991;11:55–68.44. Wilcox MJ, Leonard LB. Experimentalacquisition <strong>of</strong> Wh- questions in<strong>language</strong>-disordered children. JSpeech Hear Res 1978;21:220–39.45. Zwitman DH, Sonderman JC. Asyntax program designed to presentbase linguistic structures to<strong>language</strong>-disordered children. JCommun Disord 1979;12:323–35.46. Barnett WS, Escobar CM, RavstenMT. Parent <strong>and</strong> clinic earlyintervention for children with<strong>language</strong> h<strong>and</strong>icaps: a costeffectiveness analysis. J Di<strong>vision</strong>Early Child 1988;12:290–8.47. Bolger P, Stewart Brown S,Newcombe E, et al. Vision screeningin preschool children: comparison <strong>of</strong>orthoptists <strong>and</strong> clinical medical<strong>of</strong>ficers as primary screeners. BMJ1991;303:1291–4.48. Beardsell R. Orthoptic visualscreening at 3.5 years byHuntingdon Health Authority. BrOrthop J 1989;46:7–13.49. Edwards R. Orthoptists as pre-schoolscreeners: a 2 year study. Br Orthop J1989;46:14–19.10 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screeningAPRIL 1998

50. Ingram R, Holl<strong>and</strong> W, Walker C, etal. Screening for visual defects inpreschool children. Br J Ophthalmol1986;70:16–21.51. Jarvis S, Tamhne R, Thompson L, etal. <strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening. ArchDis Child 1990;65:288–94.52. Milne C. An evaluation <strong>of</strong> casesreferred to hospital by the Newcastlepreschool orthoptic service. BrOrthop J 1994;51:1–5.53. Newman D, Hitchcock A, McCarthyH, et al. <strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening:outcome <strong>of</strong> children referred to thehospital eye service. Br J Ophthalmol1996;80:1077–82.54. Wormald R. <strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong>screening in Cornwall: performanceindicators <strong>of</strong> community orthoptists.Arch Dis Child 1991;66:917–20.55. Williamson T, Andrews R, Dutton G,et al. Assessment <strong>of</strong> an inner cityvisual screening programme forpreschool children. Br J Ophthalmol1995;79:1068–73.56. Bray L, Clarke M, Jarvis S, et al.<strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening: aprospective comparative evaluation.Eye 1996;10:714–18.57. Good W, da Sa L, Lyons C, et al.Monocular visual outcome inuntreated early onset esotropia. Br JOphthalmol 1993;77:492–4.58. Aurell E, Norrsell K. A longitudinalstudy <strong>of</strong> children with a familyhistory <strong>of</strong> strabismus. Br JOphthalmol 1990;74:589–94.59. Hard A, Williams P, Sjostr<strong>and</strong> J. Dowe have optimal screening limits inSweden for <strong>vision</strong> testing at the age<strong>of</strong> 4 years? Acta Ophthalmol Sc<strong>and</strong>1995;73:483–5.60. Stewart-Brown S, Haslum M, ButlerN. Educational attainment <strong>of</strong> 10 yearold children with treated <strong>and</strong>untreated visual defects. Dev MedChild Neurol 1985;27:504–13.61. Teasdale T, Fuchs J, Goldschmidt E.Degree <strong>of</strong> myopia in relation tointelligence <strong>and</strong> educational level.Lancet 1988:1351–54.62. McManus I, Mascie-Taylor C.Biosocial correlates <strong>of</strong> cognitiveabilities. J Biosoc Sci1983;15:289–306.63. Peckham C, Gardiner P, Goldstein H.Acquired myopia in 11 year oldchildren. BMJ 1977;1:542–5.64. Grosvenor T. Are visual anomaliesrelated to reading ability? J AmOptom Assoc 1977;48:510–17.65. Simons H, Gassler P. Visionanomalies <strong>and</strong> reading skill: a metaanalysis<strong>of</strong> the literature. Am J OptomPhysiolog Optics 1988;65:893–904.66. Bishop D, Jancey C, Steel A.Orthoptic status <strong>and</strong> readingdisability. Cortex 1979;15:659–66.67. Hall P. The relationship betweenocular functions <strong>and</strong> readingachievement. J Pediatr OphthalmolStrabismus 1991;28:17–9.68. Alberman E, Butler N, Gardiner P.Children with squints – ah<strong>and</strong>icapped group? Practitioner1971;206:501–6.69. Bax M, Whitmore K.Neurodevelopmental screening inthe school-entrant medicalexamination. Lancet1973;825:368–70.70. McGee R, Williams S, Simpson A, etal. Stereoscopic <strong>vision</strong> <strong>and</strong> motorability in a large sample <strong>of</strong> sevenyear old children. J Hum MovementStudies 1991;13:343–52.71. Fielder A, Moseley M. Doesstereopsis matter in humans? Eye1996;10:233–8.72. Jones R, Lee D. Why two eyes arebetter than one: the two views <strong>of</strong>binocular <strong>vision</strong>. J Exp Psychol, HumPercept Perform 1981;7:30–40.73. Servos P, Goodale M, Jakobson L.The role <strong>of</strong> binocular <strong>vision</strong> inprehension: kinematic analysis.Vision Res 1992;32:1513–21.74. Kani W. Human amblyopia <strong>and</strong> itsperceptual consequences. Durham:<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Durham, 1980.75. Williams C, Harvey I, Frankel S, et al.<strong>Preschool</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening – results<strong>of</strong> a r<strong>and</strong>omised controlled trial.Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci1996;37:111.76. Nolan J. Data on preschool <strong>vision</strong>screening in South Birmingham,April 1995–March 1996. Personalcommunication, 1996.77. Allen J, Bose B. An audit <strong>of</strong> preschool<strong>vision</strong> screening. Arch Dis Child1993;67:1292–93.78. Cameron H, Cameron M. Visualscreening <strong>of</strong> pre-school children.BMJ 1978:1693–94.79. Gallaher R. Community orthopticvisual screening: first year report,1994–1995. South BuckinghamshireNHS Trust, 1995.80. Kohler L, Stigmar G. Vision screening<strong>of</strong> four-year-old children. ActaPaediatr Sc<strong>and</strong> 1973;62:17–27.81. Kohler L, Stigmar G. Visual disordersin 7-year-old children with <strong>and</strong>without previous <strong>vision</strong> screening.Acta Paediatr Sc<strong>and</strong> 1978;67:373–7.82. Seng C, Curson J. Study <strong>of</strong> theoutcomes <strong>of</strong> referrals from theorthoptic <strong>vision</strong> screening programme.Luton: Bedfordshire Health, 1991.83. James J. Data on preschool <strong>vision</strong>screening in Highworth, Swindon,1983–1991. Personalcommunication, 1996.84. Keith C, Howell E, Mitchell D, et al.Clinical trial <strong>of</strong> the use <strong>of</strong> rotatinggrating patterns in the treatment <strong>of</strong>amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol1980;64:597–606.85. Nyman K, Singh G, Rydberg A, et al.Controlled study comparing CAMtreatment with occlusion therapy. BrJ Ophthalmol 1983;67:178–80.86. Tytla M, Labow-Daily L. Evaluation<strong>of</strong> the CAM treatment for amblyopia:a controlled study. Invest OphthalmolVis Sci 1981;20:400–6.87. Leguire L, Walson P, Rogers G, et al.Longitudinal study <strong>of</strong>levodopa/carbidopa for childhoodamblyopia. J Pediatr OphthalmolStrabismus 1993;30:354–60.88. Terrell Doba A. Cambridgestimulator treatment for amblyopia.An evaluation <strong>of</strong> 80 consecutivecases treated by this method. AustralJ Ophthalmol 1981;9:121–7.89. Lennerstr<strong>and</strong> G, Samuelsson B.Amblyopia in 4-year-old childrentreated with grating stimulation <strong>and</strong>full-time occlusion – a comparativestudy. Br J Ophthalmol1983;67:181–90.90. Malik S, Gupta A, Grover V.Occlusion therapy in amblyopia witheccentric fixation. Br J Ophthalmol1970;54:41–5.91. Sullivan G, Fallowfield L. Acontrolled test for the CAMtreatment for amblyopia. Br Orthopt J1980;37:47–55.92. Veronneau Troutman S, Dayan<strong>of</strong>f S,Stohler T, et al. Conventionalocclusion vs pleoptics in thetreatment <strong>of</strong> amblyopia. Am JOphthalmol 1974;78:117–20.93. Fathy V, Elton P. Orthoptic screeningfor three- <strong>and</strong> four-year olds. PublicHealth 1993;107:19–23.94. Snowdon S, Stewart-Brown S.Amblyopia <strong>and</strong> disability: aqualitative study. Oxford: HealthServices Research Unit, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>Oxford, 1997.95. Group PASR. Efficacy <strong>of</strong> prismadaptation in the surgicalmanagement <strong>of</strong> acquired esotropia.Arch Ophthalmol 1990;108:1248–56.96. Ohtsuki H, Hasebe S, Tadokoro Y, etal. Preoperative prism correction inpatients with acquired esotropia.Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol1993;231:71–5.97. Troilo D. Neonatal eye growth <strong>and</strong>emmetropisation – a literaturereview. Eye 1991;6:154–60.APRIL 1998 Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screening EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE 11

The Research Team:This bulletin summarises theresults <strong>of</strong> three recent systematicreviews, commissioned by the NHSHealth Technology AssessmentProgramme, which were led by thefollowing people:HearingJohn Bamford, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> ManchesterAdrian Davis, MRC Institute <strong>of</strong> HearingResearch, NottinghamSpeech <strong>and</strong> LanguageJim Boyle, Strathclyde <strong>University</strong>James Law, City <strong>University</strong>VisionSarah Chapman, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> OxfordSarah Stewart-Brown, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong>OxfordThe bulletin was written <strong>and</strong> produced by:Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Trevor Sheldon, Paul Wilson,Mary Turner Boutle <strong>and</strong> Frances Sharp,NHS Centre for Reviews <strong>and</strong>Dissemination, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>.Acknowledgements:Effective Health Care would like toacknowledge the helpfulassistance <strong>of</strong> the followingindividuals who commented onthe text.■ Sheila Adam, Health ServicesDirectorate, Department <strong>of</strong> Health■ Mark Baker, North <strong>York</strong>shire HealthAuthority■ Simon Balmer, Nuffield Institute forHealth, Leeds■ Allan Colver, Community ChildHealth, Gateshead■ Alison Evans, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Leeds■ Jenny Firth-Cozens, NHS ExecutiveNorthern <strong>and</strong> <strong>York</strong>shire■ Alex<strong>and</strong>er Foss, Queen’s MedicalCentre, Nottingham■ David Hall, Sheffield Children’sHospital■ Steve Jarvis, Community Child Health,Gateshead■ Thomas Klee, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> Newcastle■ Dee Kyle, Bradford Health Authority■ Simon Lenton, Community ChildHealth, Bath■ Roderick MacFaul, Paediatrics <strong>and</strong>Child Health, Department <strong>of</strong> Health■ Colin Pollock, Wakefield HealthAuthority■ D Roberts, Child Health Services,NHS Executive■ Sue Roulstone, Bristol■ Diana S<strong>and</strong>erson, <strong>York</strong> HealthEconomics Consortium■ Colin Waine, Sunderl<strong>and</strong> HealthAuthority■ John Wright, Bradford Royal Infirmary■ Keith Young, Health ServicesDirectorate, Department <strong>of</strong> HealthThe Effective Health Care bulletins arebased on systematic review <strong>and</strong>synthesis <strong>of</strong> research on the clinicaleffectiveness, cost-effectiveness <strong>and</strong>acceptability <strong>of</strong> health serviceinterventions. This is carried out by aresearch team using establishedmethodological guidelines, with advicefrom expert consultants for each topic.Great care is taken to ensure that thework, <strong>and</strong> the conclusions reached,fairly <strong>and</strong> accurately summarise theresearch findings. The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>York</strong> accepts no responsibility for anyconsequent damage arising from theuse <strong>of</strong> Effective Health Care.Effective Health Care BulletinsVol. 21. The prevention <strong>and</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong>pressure sores2. Benign prostatic hyperplasia3. Management <strong>of</strong> cataract4. Preventing falls <strong>and</strong> subsequent injuryin older people5. Preventing unintentional injuries inchildren <strong>and</strong> young adolescents6. The management <strong>of</strong> breast cancer7. Total hip replacement8. Hospital volume <strong>and</strong> health careoutcomes, costs <strong>and</strong> patient accessVol. 31. Preventing <strong>and</strong> reducing the adverseeffects <strong>of</strong> unintended teenagepregnancies2. The prevention <strong>and</strong> treatment <strong>of</strong> obesity3. Mental health promotion in high riskgroups4. Compression therapy for venous legulcers5. Management <strong>of</strong> stable angina6. The management <strong>of</strong> colorectal cancerVol. 41. Cholesterol <strong>and</strong> coronary heart disease:screening <strong>and</strong> treatmentSubscriptions <strong>and</strong> enquiries:Effective Health Care bulletins are published in association with FT Healthcare. The Department <strong>of</strong> Health funds a limited number <strong>of</strong> thesebulletins for distribution to decision makers. Subscriptions are available to ensure receipt <strong>of</strong> a personal copy. 1998 subscription rates, includingpostage, for bulletins in Vol. 4 (6 issues) are: £42/$68 for individuals, £68/$102 for institutions. Individual copies <strong>of</strong> bulletins from Vols 1–3 areavailable priced £5/$8 <strong>and</strong> from Vol. 4 priced £9.50/$15. Discounts are available for bulk orders from groups within the NHS in the UK <strong>and</strong> toother groups at the publishers discretion.Please address all orders <strong>and</strong> enquiries regarding subscriptions <strong>and</strong> individual copies to Subscriptions Department, Financial Times Pr<strong>of</strong>essional,PO Box 77, Fourth Avenue, Harlow CM19 5BQ (Tel: +44 (0) 1279 623924, Fax: +44 (0) 1279 639609). Cheques should be made payable toFinancial Times Pr<strong>of</strong>essional Ltd. Claims for issues not received should be made within three months <strong>of</strong> publication <strong>of</strong> the issue.Enquiries concerning the content <strong>of</strong> this bulletin should be addressed to NHS Centre for Reviews <strong>and</strong> Dissemination, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>, <strong>York</strong>YO1 5DD; Fax (01904) 433661 email revdis@york.ac.ukCopyright NHS Centre for Reviews <strong>and</strong> Dissemination, 1998. NHS organisations in the UK are encouraged to reproduce sections <strong>of</strong> thebulletin for their own purposes subject to prior permission from the copyright holder. Apart from fair dealing for the purposes <strong>of</strong> research orprivate study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs <strong>and</strong> Patents Act, 1988, this publication may only be produced,stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior written permission <strong>of</strong> the copyright holders (NHS Centre for Reviews <strong>and</strong>Dissemination, <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>, <strong>York</strong> YO1 5DD).The NHS Centre for Reviews <strong>and</strong> Dissemination is funded by the NHS Executive <strong>and</strong> the Health Departments <strong>of</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong>, Wales <strong>and</strong> NorthernIrel<strong>and</strong>; a contribution to the Centre is also made by the <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>York</strong>. The views expressed in this publication are those <strong>of</strong> the authors <strong>and</strong>not necessarily those <strong>of</strong> the NHS Executive or the Health Departments <strong>of</strong> Scotl<strong>and</strong>, Wales or Northern Irel<strong>and</strong>.Printed <strong>and</strong> bound in Great Britain by Latimer Trend & Company Ltd., Plymouth. Printed on acid-free paper. ISSN: 0965-028812 EFFECTIVE HEALTH CARE Pre-school <strong>hearing</strong>, <strong>speech</strong>, <strong>language</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>vision</strong> screeningAPRIL 1998