Report - Bernard van Leer Foundation

Report - Bernard van Leer Foundation

Report - Bernard van Leer Foundation

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

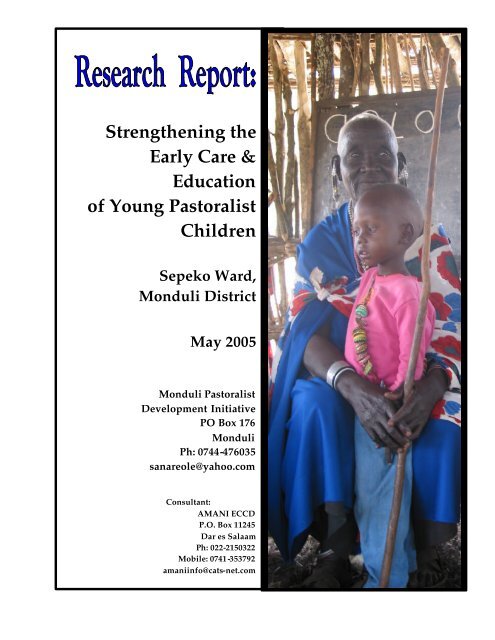

AcknowledgmentsJust as young children are intricately connected to their families and communities, and arevery dependent upon them in so many ways, efforts to support them must be equally interconnected.This research represents the collaborative efforts of many and thereby, very richexperiences for all involved.We would like to thank:-• The communities, who warmly welcomed us, and took the time to share the richness anddiversity of their cultural knowledge, beliefs, practices for caring for & educating theiryoung children;• The children of Sepeko Ward who shared with us their thoughts, ideas, challenges,aspirations – both verbally and through their play and drawings, which are a tribute totheir individuality, creativity, and innate potential;• The Sepeko Ward Development Committee for its leadership and commitment to findinglasting solutions to supporting the holistic care and early education of young children inthe Ward;• The District Executive Director and officials of Monduli District Council and the DivisionOfficials, for their insights and support throughout the research and initial feedbackphase, and their public recognition that quality early care & education is the criticalfoundation for children’s future success in school;• Mr Oliver Mhaiki, Director of Primary Education, Ministry of Education & Culture, forhis advice and encouragement prior to our undertaking this research;• MPDI staff, Erasto Ole Sanare, Mohammed Nkinde, Thomas Meiyan and Lightness fortheir logistical support and good will throughout the research processes;• The Research Team members - Erasto Ole Sanare, Mohammed Nkinde, Thomas Meiyan,Lengai Edward Barnoti; AMANI ECCD - Lorna Fernandes, Elle Hughes, for great teamspirit and perseverance that once again proves that ‘together we can achieve so much’;• AMANI office support staff, Peter Jackson & Andrew Nkunga for all their logistical,back-up and support work, from the preparation of the research to the final reporting;• The <strong>Bernard</strong> <strong>van</strong> <strong>Leer</strong> <strong>Foundation</strong> for making this research possible through financialsupport to MPDI.This child-focused community research has been a very enriching experience for us as earlychildhood professionals. However, above all, we hope that the outcomes of this research willinform collaborative action to improving the quality of Early Childhood Care & Educationfor young pastoralist children in Sepeko Ward and ultimately, Monduli District.Chanel CrokerResearch Team LeaderAMANI ECCDRenee, Age 7 years, Losimingori

Contents PageGlossaryii1. Introduction 12. Methodology 33. Early Childhood Care & Education in Pastoralist Communities 73.1 The Status of Infants & Young Children in Tanzania –Implications for Pastoralist Communities3.2 Policy Context in Tanzania 103.3 National & Regional Experiences – Lessons Learned 154. Research Findings 214.1 Summary of Key Challenges 224.2 Challenges & Opportunities Identified 235. Recommendations 366. Conclusion 38Bibliography 40Tables:Table 1: Status of Infants & Young Children in Tanzania – A Summary 7Table 2: Factors Contributing to the Poor Status of Infants & Young Children 8Table 3: The Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All: April 2000 10Table 4: Summary of the Key ECD Related Government Sectors in Tanzania 12Table 5: NSGRP – Links Between Early Childhood Development and ImprovedAccess To & Success In School 14Table 6: Government Identified Challenges & Solutions for ImprovingFormal Education for Pastoralists 16Table 7: Overview of Key Challenges Identified 22Table 8: Challenges & Opportunities Identified 23Table 9: Recommendations 36Appendices:Appendix 1: Terms of Reference & MPDI Guiding Principles 47Appendix 2: Field Research Programme 53Appendix 3: EFA Goal No. : Early Childhood Care & Education 56Appendix 4: Administrative Map of Tanzania - Monduli District – Sepeko Ward 57Appendix 5: Letters of Approval for Conducting Research 58Appendix 6: Research Tool - Background Information Data Sheets 60Appendix 7: Research Tools for Objective 1 62Appendix 8: Research Tools for Objective 2 64Appendix 9: Community Knowledge & Beliefs about the Care and Educationof Their Young Children 67Appendix 10: Children’s Drawing as Resources 69Appendix 11: District & Ward Development Committee Consultations 7i

GlossaryABEK Alternative Basic Education KaramojaBAEEP Babati Agricultural and Environment Education ProjectBEMP Basic Education Master PlanCCF Christian Children’s FundCSO Civil Society OrganizationECD Early Childhood Development (0 – 8 years)ECCE Early Childhood Care & EducationEFA Education For AllESDP Education Sector Development Programme (2000)ETP Education Training PolicyFBO Faith Based OrganizationFDC Folk Development CollegeHIV/AIDS Human Immune Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency SyndromeHTHead TeacherIMCI Integrated Management of Childhood IllnessKINNAPA An NGO supporting pastoralists’ development issues - Acronym for names of 5villages where it initially started working - Kibaya, Kimana, Njoro, Ndaleta,Namelock and PartimboLGR Local Government ReformMCDG&C Ministry of Community Development, Gender and ChildrenMDGs Millennium Development GoalsMLDW Ministry of Livestock Development and WaterMLYD&S Ministry of Labour Youth Development & SportsMOEC Ministry of Education and Culture of TanzaniaMOH Ministry of HealthMPDI Monduli Pastoralist Development InitiativeNPA Tanzania’s National Programme of ActionNGO Non Governmental OrganizationNSGRP National Strategy for Growth & Reduction of Poverty (2005/06 to 2009/10)PEDP Primary Education Development Plan (2002 – 2006)PMO Prime Minister’s OfficePRSP Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (2000/01-02/03)ORS Orkonerei Radio ServiceStd 1 Standard One - Primary SchoolSWDC Sepeko Ward Development CommitteeTBA Traditional Birth AttendantTIETanzania Institute of EducationTRC Teacher Resource CentreTTC Teacher Training CollegeUNESCO United Nations Education, Science and Culture OrganizationUNICEF United Nations Children’s FundVPO Vice President’s OfficeWFP World Food Programmeii

1. INTRODUCTION1.1 Background of the ResearchMonduli Pastoralist Development Initiative (MPDI) is a non-governmentalorganisation based in Monduli town, which has been working closely with theSepeko Ward Development Committee (SWDC), to address pastoralist children’simproved early childhood care and education. Geographically, Sepeko Ward islocated in Monduli District, Arusha Region, northern Tanzania, and is climaticallyone of the driest areas in the country. Sepeko Ward is one of the twentyadministrative wards in Monduli district, and includes 8 villages 1 - Losimingori,Lepuko, Alkaria, Lendikinya, Mti Mmoja, Lashaine, Arkatan and Meserani Juu (seeAppendix 4 – Map). These eight villages are divided into 30 sub-villages, and arehome to an estimated 14,000 people, 80% of whom are agro-pastoralists.Recognising that the quality of care and early education of young pastoralist childrenin family and community contexts, directly impact on young children’s rate ofsurvival, cultural socialisation and informal education, and preparation for andsuccess in formal school, MPDI and SWDC have identified that a key strategies forimproving pastoralist children’s quality of life and access to and success in formal school, arethrough improved child -care and community pre-school support.To date, MPDI & SWDC have• Mobilised community awareness raising about improving early care andeducation for their young children through a partnership approach betweenfamilies, communities and service providers, including primary schools;• Facilitated parents involvement in the development of five community preschoolclasses and the running of micro projects for supporting the pre-schoolprogrammes;Given the responses to date, MPDI and SWDC seek to expand this programme ofsupporting community day care & pre-school provision, as well as ongoingsensitisation and capacity development of families, communities and serviceproviders, across the Ward. However, this aim has some key challenges.ChallengesIn line with its guiding principles (see Appendix 1) MPDI seeks to support youngchildren’s development without damaging the existing pastoralist cultural practicesof caring for children. At the same time MPDI seeks to raise awareness amongstpastoralist communities, about the benefits of formal education, in the context thatfor many pastoralists, formal education has been viewed with some suspicion, andthey prefer not to send their children to school.1 (see Appendix: MAP).1

Therefore, MPDI has recognised that if the community pre-school programmes areto be successful from the point of view of children, families and communities as wellas Ward/ District officials, then• they should support the strengthening of the traditional community day carearrangements for young children being cared for by grandmothers,• expand these arrangements to community pre-school programmes that buildon the cultural resources within the communities, such as traditional songsand stories, so that children learn to cherish the cultural practices related totheir own environment, whilst at the same time developing all the necessaryskills, knowledge and dispositions necessary for entering formal education.Therefore, MPDI contracted AMANI ECCD – Early Childhood Care & Development,Dar es Salaam, as consultants, to design and facilitate a community research to ‘hearthe voices’ of families, communities, the Sepeko Ward Development Committee andMonduli District Council, regarding the quality care and early education of youngpastoralist children in Sepeko Ward, in order to best inform MPDI’s planning.The Aim of the Research:As outlined in the Terms of Reference (Appendix 1) for this research, the aim of thisresearch was to… inform MPDI and SWDC’s planning for supporting the development of locallyappropriate community day-care and preschool programmes that are informedby the pastoralist community child-care culture and practices, whilst at the sametime successfully preparing young children for entrance into primary school.Specific Research Objectives:1. Identify and analyse community child-care practices and any existing initiativesfor children 2 – 8 years of age, highlighting strengths to build on as well as anyspecific needs, and make recommendations to inform the development of locallyappropriate community day-care and pre-school programmes.2. Identify, analyse and make specific recommendations about the challenges andopportunities related to pastoralist children’s transition to primary school interms of the family and community level of interest in formal education, theirchildren’s readiness for school, the school’s readiness for children.3. From a literature review of national ECD policies and guidelines, and lessonslearned from other pastoralist community programmes in the region, identifykey strengths, lessons learned and opportunities to build on, that may inform thedevelopment of locally appropriate community pre-school programmes in SepekoWard.2

o giving and collecting feedback from others on preliminary report;o strategies for dissemination of the final report to all stakeholders.2.4 The Research ToolsIn line with MPDI’s Guiding Principles 2 and the objectives of the Research , AMANIECCD drafted three research tools that were modified & agreed to by all Teammembers. The tools were developed to collect information regarding1. Background Information 3 on the communities and Primary schools prior tofield visits.2. The knowledge & beliefs about young children’s growth and development 4and current community pre-school arrangements.3. The interest of communities in formal education; children’s readiness forschool ; schools’ readiness for children 5 .2.5 Research InformantsMPDI & SWDC selected 9 communities to be involved in the community fieldresearch. The selection was on the basis that they are representative of the diversityof the communities across the ward, including communities …o with a preschool,o without a preschool,o with a primary school but no pre-primary,o with a pre-primary class at the primary school.The research team agreed that the language of the research with communityinformants would be Kimaasai, and Kiswahili with WDC & District Council.2 See Appendix 1: Guiding Principles3 Appendix 6: Research Tool - Background Information Data Sheets4 Appendix 7: Research Tools – Objective 15 Appendix 8: Research Tools – Objective 24

Care was taken in the planning phase to ensure that a wide cross-section ofinformants, with equitable gender balance, would be consulted,o at the community level, from young children to the elderly;o government, NGOs, and Faith Based Organisations.The range of informants was planned to include:-Community level Informants: Social Service Informants District Level Informants:o Childreno Women – traditional leaders,mothers, grandmothers,youth, traditional birth,attendants, business women &farmerso Men – traditional leaders,fathers, elders, youth,livestock owners & herders,farmers, business men,religious leaders,o Village government leaders,o Pre-school committeememberso Community pre-schoolteacherso Village health workers &TBAsPrimary Schoolso Children - Pre-primay, Std 1 & 2o School committee memberso Head teacherso Std 1 & 2 teacherso Teachers of Maasai and nonMaasai originsClinics &Dispensarieso staffWard Level Informants:o Sepeko Ward Councilloro Ward executive Officero Ward Education Coordinator,o Ward Community DevelopmentOfficero Ward Livestock Officero Village Chair persons,o Village executive officers.o District Executive Director,o District Education Officer & DistrictAcademic Officer,o District Chief School Inspector andother inspectorate staff,o District Community DevelopmentOfficer,o District Agriculture and LivestockDistrict Officers ,o Department of Water and LivestockRepresentativeo Representatives from of theDepartment of Health includingMonduli Hospital Head ofHIV/AIDS,o District Administrative Secretaries,o Division Administrative Secretary,o Monduli Teacher Training CollegeStaff,o Monduli Teacher Res ource CentreStaff,o Monduli Folk DevelopmentCollege staff,o Monduli Dioceses Disabilitiestreatment Centre staff.2.6 Research MethodsDuring the fieldwork, team members worked in pairs as co-researchers and fortranslation from Kimaasai to Kiswahili or English, and were on location for up to 4hours in each community visited.The research approaches used included, guided interviews, focus group discussions,and observations. In some cases children’s drawing was used as a specific strategyfor engaging children and including their feedback in the research. The framing ofgroup discussions and interviews were modified as much as possible to suitindividual communities, depending on the depth of background informationavailable on each community prior to the filed visit. Care was taken to ensure that ‘allvoices’ could be heard, for example in some instances it was necessary to divide5

group discussions into gender related groups, in other communities the womenrequested to stay together with the men.2.7 Documentation approachesDiverse documentation approaches were intentionally used during the researchprocesses so as to more readily enable a) cross-checking of information and, b) thesharing of feedback with informants. Documentation approaches included notetaking, photographs, video recording, audio recording. Prior to any documentation,permission was requested and approval was given, for researchers to freelydocument using all of the above strategies. Furthermore, as an important part ofrespecting ownership of information, the Research Team committed to presentingeach community with a set of the photos taken in their community, as part of thefeedback process.2.8 Data Analysisa. Research Team members engaged in daily debriefing and analysis sessions at theend of each field research day and the diverse documentation proved to bevaluable in cross-checking information;b. A two day workshop at the end of the research, brought together resource peopleto share initial collation of data and research experiences, which enabled acollective preliminary analysis of data and drafting of some initial keyrecommendations;c. In order to ensure verification of data analysis & recommendationsi. AMANI facilitated first draft report feedback meetings with MPDI, SepekoWDC and Monduli District Councilii. MPDI facilitated community feedback meetings on the draft.2.9 Constraints and ChallengesNotable limitations in the research process centred on time constraints:-• We could only visit each community once as a team, for a period of 3 – 4hours. This meant that it was not possible engage community members in thecontext of their home environments; it was not possible for researchers tospend in-depth time with children themselves;• Cross-checking and consolidation of data had to be done at a later date byMPDI alone;• During the field research, a government Minister was also in the District, andtherefore many officials and community leaders were involvedsupporting related activities, with limited time for discussion with theresearch team.6

3. EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE & EDUCATION (ECCE) INPASTORALIST COMMUNITIES3.1 The Status of Infants & Young Children in Tanzania –Implications for Pastoralist CommunitiesPoverty impacts on the lives of more than 50% of Tanzania’s population. Combinedwith a number of socio-cultural factors, the capacity of many poor families toadequately care for and nurture their children is increasingly limited. Whilst specificdata was not readily available from the Monduli District Council, Table 1 below,summarises the status of young children and their caregivers in Tanzania, fromwhich implications can be drawn for planning for improved Early Childhood Care &Education specifically in pastoralist communities.Table 1: Status of Infants & Young Children in Tanzania – A Summary.Source: Towards Tanzania’s ECD EFA Action Plan, 2003 – 2015, Tanzania ECD Network, 20021. More Infants and Young Children are Struggling to Survive than 10 Years Ago.a. There has been an increase in infant and under-five mortality. In ‘…the year 2000, 1 in 6 children diedbefore the age of five.’ 6 with• ‘At least 75 percent of these deaths … attributed to easily preventable conditions/diseases …malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea, malnutrition and measles’, 7• with 46% of women beginning childbearing before the age of 18, there are significantly moredeaths of children of mothers who give birth at a younger age. 8• estimates from the National Aids Control Programme showing that ‘…70,000 – 80,000 newly bornwere infected annually, … and that 80% of those infected at birth do not survive their secondbirthday and at the age of five very few will still be alive.’ 9• ‘In the absence of preventive measures, the risk of a women with HIV passing on the virus to herchild ranges from 25% to 35% in developing countries like Tanzania. 10b. Little improvement in malnutrition levels of infants and children, with data suggesting that one inevery three Tanzanian children is malnourished. 11• Stuntedness has increased, with ‘.. nearly half of all children … either moderately or severelystunted. TRCHS 1999’ 12• ‘..1999 assessments of nutrition indicated that 44% of children under five years were stunted ,17% severely so. 5% of children under five are wasted , and 29% are underweight. (TRCHS1999:122)’ 13• It is estimated that approximately 150,000 to 200,000 children are born with Low Birth Weighteach year. These children are at a greater risk of under nutrition and mortality in the first year oflife, ‘and continue to be at a disad<strong>van</strong>tage for the rest of their lives’ 142. The majority of young children are not thriving, and with very limited community-based child-caresupport, children are entering school already disad<strong>van</strong>taged.a. In reality, if the Primary Education Development Plan (2002 – 2006) is to have an impact, then, as6 ibid7 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Country Programme of Co-operation for 2002 – 2006, Draft document,Version 01.04.01ECD sub project 2.8 Tanzania Reproductive & Child Health Survey 1999:88; figs 2.6 and 2.79 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Situation Analysis of Children in Tanzania.10 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Situation Analysis of Children in Tanzania.11 Ibid p.2612 ibid p.2613 ibid.14 ibid p.27.7

UNICEF have indicated, ‘… it is not enough just to decree that all children should be sent to schoolat the age of seven, unless there is also a concerted campaign to improve the nutritional status ofchildren from an early age. 15b. There is a high demand, and urgent need for community-based child-care support‘The women have no alternative for child care. When they look after children they can’t work,therefore, no food and less income; when they work, they can’t look after children. It is the childrenwho suffer as the women try to do both.’ – Male Elder, Mtwara Rural. 16c. Only 3% of pre-school age children access such services 17d. The number of HIV/AIDS affected young children is rapidly increasing, with no concrete supportreadily available. UNICEF has indicated that ‘…of the approximately 2 million orphans, 97 percent… are living with their extended families, many of them in seriously deprived circumstances. 18 Insome communities the number of children orphaned is as high as 40% and the proportion of childrenin school who have been orphaned has reached 50%. 19 Whilst there is some support for school-ageorphans, as one community member from Moshi rural has expressed, in Tanzania it seems that, Anorphan is only an orp han when they reach Standard One. 203. Contributing factors to infants and young children’s poor status.Table 2: Factors Contributing to the Poor Status of Infants & Young ChildrenSource: Towards Tanzania’s ECD EFA Action Plan, 2003 – 2015, Tanzania EC D Network, 20021. Poverty impacts on the lives of more than 50% of Tanzania’s population. Combined with a number ofsocio-cultural factors, the capacity of many poor families to adequately care for and nurture theirchildren is increasingly limited.2. The low status of women combined with their heavy workloads, negatively impacts on the quality ofcare of infants and young children.‘The root cause of maternal deaths and morbidity in Tanzania are directly related to women’s lowsocio-economic statues and their limited access to quality social services. In the current situation,complications during pregnancy and birth lead to illness and disabilities – and have graveconsequences for women’s lives and survival as well as that of their children. 21i. significant gender inequalities prevail, and women often are excluded from decision-makingespecially related to family resources control and inheritance issues;ii.iii.women carry the bulk of the responsibility for child-care, whilst their work loads appear to beincreasing;women (and youth) provide most of the labour force in rural areas, they have very limited accessto land – as land tenure which is a male issue , and their participation in family allocation of fundsand community decision -making is negligible. It is estimated that in many villages women form lessthan 10% of representation in village governments. 22iv. with the break-down of families, it is estimated that approximately 13% of rural households areheaded by women, which, on average, are poorer ..’ 23v. women’s standard of education is low – 57.1%literacy rate compared to 70.6 % for men. 2415 UNICEF, Tanzania, 1995, The Girl Child in Tanzania16 AMANI ECCD, 2001,17 Government of the United Republic of Tanzania, Basic Education Master Plan, 200018 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Situation Analysis of Children in Tanzania.19 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Situation Analysis of Children in Tanzania.20 AMNANI ECCD, 200121 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Country Programme of Co-operation for 2002 – 2006, Draft document,Version 01.04.01ECD sub-project 1.3.22 United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Country Programme of Co-operation for 2002 – 2006, Draft document.23 UNDP 2000, Tanzania Human Development <strong>Report</strong> 1999, p.424 UNDP, 2001, United Nations Development Assistance Framework for Tanzania, p.138

vi.there has been increase in maternal mortality rates during the ‘90s.vii ‘The prevalence of HIV infection in pregnant women is about 12 percent and of those about 40%pass on the infection to their children .’ 253. Poor Health, Water & Sanitation in Rural Areas Adds to Poor Childcare Conditionsi. Access to quality health services by the poor has been negatively influenced by (i) limited servicesavailable; (ii) the introduction of user cost -sharing schemes, which in reality mean that the mostvulnerable – especially women and children, are excluded from services.ii.It is estimated that less than 29 percent of rural population have access to clean and potablewater..’ , and rural women and children in rural areas spend twice as much time as urban dwellersin collecting water. 26iii. Effective use of latrines in rural areas is rated at only 30%. 27Monduli District Council itself recognises that that it does not have readily accessibleand reliable data on indicators of infants and children’s health & well-being in theDistrict, and that there is an urgent need for comprehensive data collection. Afterdiscussion about this national data during the research & feedback periods, Districtofficials indicated that given the hardship conditions that pastoralist communities areliving in, it is highly likely that the poor status of infants and young childrennationally is also reflected in the situation in Monduli District. Therefore, ifpastoralist children are to realise their rights to optimal development, there is anurgent need for• Reliable data regarding the health and nutritional status of pastoralist youngchildren and mothers in Monduli District;• Collaborative efforts between families, communities, Ward and DistrictCouncil stakeholders ensure that quality care (nutrition, health, sanitation)and early education of young children are prioritised in all village, Ward andDistrict plans, because these are the critical foundation years for humanresource development.25 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Country Programme of Co-operation for 2002 – 2006, Draft document.26 Government of United Republic of Tanzania & UNICEF, 2001, Situation Analysis of Children in Tanzania, p.3227 ibid p.339

3.2 Policy Context in Tanzania3.2.1 ‘Education For All’ Goal No. 1: Early Childhood Care & EducationIn April 2000, the government of Tanzania committed to the Dakar Framework forAction to achieve the six ‘Education for All’ (EFA) goals (see Appendix 3: EFAGoals). Significantly, the first of these goals focuses on comprehensive EarlyChildhood Care and Education (ECCE), for children 0 – 8 years, as the importantfoundation of all other goals. The essential philosophy of EFA Goal No. 1 is that‘Learning Begins at Birth’, and the foundation for success in formal education are laidin the years BEFORE children enter school. As detailed in Table 3, EFA Goal No. 1sets a very comprehensive framework for evaluating and planning for improvedquality of care and education of young children in family, community and morestructured contexts, especially those who are already disad<strong>van</strong>taged. Therefore, thedetails of this goal have been used as a guide by the consultants in designing andcarrying out this research, as well as framing the recommendations.Table 3: The Dakar Framework for Action: Education for All: April 2000Goal No. 1: Expanding and improving comprehensive early childhood care and education,especially for the most vulnerable and disad<strong>van</strong>taged children.All young children must be nurtured in safe and caring environments that allow them to become healthy, alert,and secure and be able to learn.Good quality early childhood care and education, both in families and in more structured programmes, havea positive impact on the survival, growth, development and learning potential of children.Early Childhood Care & Education Programmes should…‣ be comprehensive, focusing on all of the child's needs andencompassing• health• nutrition and hygiene• cognitive• psycho-social development.‣ be provided in the child's mother tongue‣ help to identify and enrich the care and education of childrenwith special needs.‣ be achieved though partnerships between• governments,• NGOs• communities and• families‣ include activities• centred on the child,• focused on the family,• based within the community• supported by national, multi-sectoral policies andadequate resources.Who is responsible?Governments across rele<strong>van</strong>t ministries,have the primary responsibility for‣ formulating early childhood careand education policies within thecontext of national EFA plans,‣ mobilizing political and popularsupport, and‣ promoting flexible, adaptableprogrammes for young childrenthat are appropriate to their ageand not mere downwardextensions of formal schoolsystems.‣ The education of parents andother caregivers in better childcare, building on traditionalpractices, and the systematic useof early childhood indicators areimportant elements in achievingthis goal.10

3.2.2 Towards Integrated Multi-sectoral ECD Policies & GuidelinesFor young children to develop well, all aspects of their physical, social, emotional,intellectual and spiritual development must be supported simultaneously, fromconception to eight years of age.This was recognised by the government of Tanzania during the 1990s, when variouschild-related ministries began to highlight that sectoral approaches to EarlyChildhood Development (ECD) support, have been hindering progress. In 1993, theMinistry of Community Development, Gender & Children (MCDG&C), as the sectorresponsible for coordinating all sectors related to children’s issues called forintegrated policies and approaches to supporting Early Childhood Development(ECD), highlighting that‘…no goal for children can be achieved by a single sector working on its own’ 28 ,MCDG&C,1993In the National Health Policy of 1990, the Ministry of Health had also indicated that ..‘Health is a multi-sectoral responsibility for partners in education, agriculture, waterand sanitation community development etc.’ 29At the central government level, policies and guidelines related to the needs andrights of young children, are divided across four main sectors:-1. Ministry of Community Development Gender & Children2. Ministry of Health3. Ministry of Labour Youth Development & Sports – Social WelfareDepartment4. Ministry of Education & Culture… supported by …1. Ministry of Water & Livestock2. Ministry of Agriculture & Food SecurityThe ECD policies, guidelines, specific responsibilities and challenges identified foreach of the main ECD related sectors are summarised over, in Table 4: Summary ofthe Key ECD Related Government Ministries in Tanzania. (Source, Tz ECD Network,2003, ‘Towards Tanzania’s ECD & EFA Action Plan: 2003 – 2015’, p. 8-9)28 United Republic of Tanzania, (1993) Tanzania’s National Programme of Action (NPA) to Achieve the Goals forTanzanian Children in the 1990s11

Table 4: Summary of the Key ECD Related Government Sectors in TanzaniaECD Policies & Guidelines Responsibilities & Initiatives Key Challenges1. Ministry of Community Development, Gender & Children – MCDG&CCommunity DevelopmentPolicy, June 1996. (revisedpolicy yet to be released)Women and GenderDevelopment Policy, 2000.Child Development Policy,October 1996 (revised 2000)• Draft Child DevelopmentPolicy ImplementationFramework 2000,• Child defined as 0 – 18years.Co-ordinating Role through theDirectorate of Children (formed July2003), of all the sectors related tochildren’s issues through the ChildDevelopment Policy, in relation to1. the implementation of the CRC inTanzania.2. integrated issues of child survival,protection and development in thecontext of women affairs, genderissues and integrated communitydevelopment.3. Tanzania’s ‘National Programme ofAction (NPA) to Achieve the Goalsfor Tanzanian Children’ 19911. ‘No goals for children can beachieved by a single sectorworking on its own.’National Programme ForAction for Children ,19932. Strategies for co -ordinatingECD related sectors are yet tobe realized;3. Limited institutional capacityin ECD;2. Ministry of Health - MoHThe National Health Policy(1990)• Young child - conception- 5 years in context offamily health;• Reproductive and ChildHealth Section of theDirectorate of PreventiveServices.• Food & Nutrition Policy(1992)a. A number of key interventionsunder the Reproductive andChild Health Section (RCHS) ofDirectorate of PreventativeServices include:-• Safe Motherhood Initiative• Extended Programme onImmunization (EPI);• Integrated Management ofChildhood Illness (IMCI),through improved familyand community practicesfocusing on Physical andpsycho-social growth &development; Diseaseprevention; Care seeking &compliance; Homemanagement of a sick child.b. School Health Programmes –healthpromotion at school &community levelc. Tanzania Food and NutritionCentre,d. Malaria Control Programme.e. Tanzania Commission for AIDS &National AIDS ControlProgramme.1. Policy highlights that ‘Health is amulti-sectoral responsibility forpartners in education,agricultures, water and sanitation,community development etc.’ 30National Health Policy(1990)2. Available services are still limited;3. Quality of services are generallypoor;4. Cost-sharing excludesdisad<strong>van</strong>taged and mostvulnerable5. Children & women’s poorsurvival rates and health statusare directly linked to the lack ofbasic amenities, in particular cleanwater and adequate sanitation,fuel and a safe, clean, place to live.6. ‘… it is not enough just to decreethat all children should be sent toschool at the age of seven, unlessthere is a concerted campaign toimprove the nutritional status ofchildren from an early age’.(UNICEF, 1999, Children in Needof Special Protection Measures)12

ECD Policies & Guidelines Responsibilities & Initiatives Key Challenges3. Ministry of Labour, Youth Development & Sports – MLYD&S– Department of Social WelfareDay Care Centres for YoungChildren 2 – 6 years.i. Day Care Centres Act,1981 & Day Care CentresRegulations 1982.Children 0 – 6 years of age, indifficult circumstances and inneed of special protection,i. The Children’s HomeRegulations, 1968ii. Adoption Ordinanceiii. Draft National PolicyGuidelines for the Careand Support for Childrenin Need of SpecialProtection.iv. Draft Policy re HIV AIDSOrphans, 2000a. Supervision of Training of Day CareAttendants Provision of trainingguidelines for regulating governmentand civil society training initiatives.b. Guidelines, registration of servicesand supervision of programmes forchildren, ages 0 – 6 years of age, indifficult circumstances and in need ofspecial protection, includingorphans, children with disabilities,abused children, street children,children affected by natural disasters,children in single parent households,and children of adolescent mothers.1. The Department of Social Welfareis under-resourced;2. There are very few Social Welfareofficers across districts;3. The conflict between MOEC’s(1995) pre-primary policy for 5 – 6year olds and the Day Care Act(1981) is causing confusion at alllevels;4. There is a high demand for daycare support for children between2– 6 years because of the mutualbenefit such services provide bothwomen and children. However,services are mostly urban and foruser fees.4. Ministry of Education & Culture - MOECEducation & Training Policy(ETP, 1995)- Education SectorDevelopmentProgramme (ESDP,2000)- Basic Education MasterPlan (BEMP, 2001)- Primary EducationDevelopment Plan(PEDP, 2002 – 2006)Promote pre-school education 0-6years.Formalize pre-primary education for5-6 year olds, and integrate it into theformal school system. 31Guarantee access to pre-primary andprimary education and adult literacy toall citizens as a basic right. 32Pre-primary curriculum guidelines –TIE 2000.Pre-primary teacher educationcurricula – not yet achieved;Pre-Primary Teacher DeploymentPre-Primary Teacher TrainingFacilitating partnership approaches topre-primary with families,communities & NGOs ‘…with specificsupport for disad<strong>van</strong>taged groups’(ETP, 1995)1. Only 3%of pre-school age childrenon the mainland access such services(BEMP, 2000);2. There has been no governmentresourcing of pre-primary to date;PEDP excludes pre-primary;3. There is no pre-primary teachertraining curriculum (TIE, 2002)4. Pre-primary teacher training is adhoc & there is a clear lack of trainedpre-primary teachers (TIE, 2002)5. There has been no specific preprimaryteacher deployment to date,therefore where they exist they areoften teaching primary classes aswell.;6. There are guidelines for partnershipapproaches; fee paying privatesector dominates serve provision.7. There is no specific support fordisad<strong>van</strong>taged groups; the negativeeffect of cost-sharing approaches hasbeen transferred from primary topre-primary / preschool.13

3.3 National & Regional Experiences – Lessons LearnedYoung children’s early care and informal education in pastoralist communities has longbeen supported solely within the context of family and community structures, by astrong tradition of quality child-care knowledge, beliefs and practices. However in thecontext of changing livelihoods, brought on by struggles for land, environmentalhardships, drought, and a weakened family economy, heavy burdens affect families’ability to meet their basic needs. These burdens are particularly felt by women, whoseincreasingly heavy work-loads means that their capacity to care for and nurture theiryoung children is rapidly declining.a. The quality of traditional early care & education is decliningPastoralist communities’ traditional informal education, has sustained their communitiesover generations. In order to survive & excel, younger generations have learned fromtheir elders and parents the community knowledge, beliefs, life skills, culture, traditionsand taboos, through their indigenous languages, songs, stories and arts (OXFAM GBpaper, Sept 2003, Mwegio & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001).‘Pastoralist households without a doubt value education, in the widest sense of the word –and much of their child rearing and lifestyle focuses on educating their children into thepastoralist way of life. ’ Oxfam, GB paper, Sept 2003:4.Traditionally pastoralist communities, ‘Transmission of knowledge and skills is usually donepractically and on the job … (and) …there are no established institutions for transmittingknowledge-skills to young generation…’ (Mwegio, L. & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001:94)’. However,with changing community livelihoods & life-styles, and the inevitable break-down ofcommunity child-care support structures, the result is that increasingly, the quality oftraditional education is declining, because the opportunities are simply not available tochildren.b. Highly effective informal education processes have long sustained pastoralistcommunities. Their interest in formal education is increasingChildren make up 58 % of the total population in Monduli District - 61,541 between 0 – 8years; 34% of total population, and 106,994 children between 0 – 18 years, (NationalCensus 2002). Whilst the Monduli District Council recognise that the collection ofaccurate data remains a challenge, it has been reported that there is a significant increasein the number of children enrolling in primary school within a 2 year period – from 2000to 2002. From District data in 2000- approximately 31 % of school age children wereenrolled, and specifically in Sepeko Ward, 43 %, (Mwegio, L. & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001:42).Whilst the government’s Education & Training Policy, Basic Education Master Plan andPrimary Education Development Plan commit to ensure all children’s access to quality15

education, a MOEC, UNICEF, UNESCO Study on ‘Education for Nomadic Communities inTanzania’, highlights that ‘… it remains a challenge to ensure that all nomadic children whereverthey are access, participate, remain , perform well and complete their basic education.’ (Mwegio,L. & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001:79). The authors highlight specific issues which lead to poorenrolment & high level of drop out of pastoralist children from schools, including,poverty; lack of water; distance; lack of food in the schools; shortage of teachers; poorlearning environment – curriculum that has little rele<strong>van</strong>ce; mobility of communities;early marriages; cultural practises, i.e rituals including circumcision; low level ofeducational awareness. (Mwegio, L. & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001:79).However, despite the challenges, ironically, the‘Pressures of life, such as drought, conflict or socio-economic factors…result in pastoralistsincreased demand for formal education, to provide alternatives for th eir children.’Oxfam GB paper, Sept 2003, Monduli District Council, 2003Some specific government identified challenges of formal education in relation topastoralist communities and & possible solutions are outlined in Table 6: Govt identifiedchallenges & solutions for improving formal education for pastoralists, below.Table 6: Government t identified challenges & solutions for improving formal education for pastoralistsChallengesPrimary School programmes & approaches are not rele<strong>van</strong>t to pastoralist children.‘The curriculum does not respond to needs and aspirations of nomadic children…,• it does not link with informal and indigenous education, which is more functional, and• does not offer to the children the necessary life and survival skills within their immediate environment’Mwegio, L. & Mlekwa, V.M, 2001:102Suggested SolutionsMonduli District Council (Monduli Council, 2003:14 ) have suggested …• involvement of communities ‘….. in preparation of curricular … (based) .. on the socio-cultural background ofthe community, ‘• ‘..making teaching and learning methodologies more rele<strong>van</strong>t to Maasai community,’• adjusting timing of school terms fit with migration period, and• establishin g parent education, to lead to greater understanding between families, communities andteachers,’MOEC, UNICEF, UNESCO Study on Education for Nomadic Communities in Tanzania suggests• Develop a Core & Functional curriculum - researchers in a Tanzanian study in nomadic education tosuggest the development of a, ‘..that the curriculum be divided into a core curriculum (mathematics, languagesand general knowledge)… and a functional curriculum… that should provide skills education deeply rooted into thesocio-economic activities and lifestyles of the children… and both categories of the curriculum ( to be) taken seriously…should be equally weighted and examined.’ (pg 103)• Strengthen the concept of community schools - ‘… organise and coordinate school activities in such a way thatschools are operated as community schools which prepare children to meet the challenges and improve their lives, (pg.102)• Collaborative multi-sectoral approaches to improving educational outcomes for pastoralsit children• ‘… a multi-sectoral programme needs to be established, consisting of projects in education, agriculture,livestock, water development, natural resources, health, hunting, bee-keeping and community development’,(pg. 101)16

Babati Agricultural and Environment Education Project (BAEEP) - Lessons Learned:One very local example of linking informal and formal education exists in Babati a fewhours from Monduli town. The Babati Agricultural and Environment Education Project(BAEEP) supported by District in collaboration with FARM AFRICA, aims to linkcommunity and school knowledge, through participation of students, teachers, andparents in the development & management of school gardens and nurseries.Planned outputs of BAEEP include the development of practical and rele<strong>van</strong>t learningcontexts through increased participation of parents in the education system.Coming up to the end of its second year, identified lessons learnt to date, include: -‣ Consultations with parents and communities have been slow to happen, relying onexisting structures such as school committees and parents/general meetings, andrallying by village officials,‣ Community awareness-raising initiatives are yet to truly mobilise;‣ The Life-skills subject Agriculture/Livestock husbandry and Environment, is onlyvery small section within the existing curriculum, and is not examinable, thereforeteachers do not invest time and effort in it despite it’s importance to the livelihood ofrural communities and national economy;‣ School committees and parents have little understanding of LGRP, and what itcan/does mean to them, especially in increased participation and management inschool matters. This situation is not helped with Head Teachers resistance to ‘handover’ and be appropriately transparent in decision-making including resourceallocation.Alternative Basic Education for Karamajong (ABEK), Uganda, - Lessons Learned:ABEK - Alternative Basic Education for Karamajong, Uganda, has grown out of what isdescribed as ‘positive resistance’, to a formal education (of the past) that had no practicalbenefit or value in helping their children to adapt and make better use of theirenvironment. The programme is a non-formal alternative to basic education, and aims toprovide rele<strong>van</strong>t education for pastoralist Karamajong children, 6 – 18 year olds, whowould grow up and continue the Karamajong lifestyle, whilst creating a path to formalschool for those who want to go on, (Nagel 2002). Some key lessons to draw from theABEK experiences to date, include: -‣ Links school schedules & hours to community lifestyles & children’s family workroles& thereby ensure their ongoing informal education - ‘ ...ABEK adapts schoolingto the “framework” of Karamajong’s agro-pastoralist lifestyle, recognising the central roleof the child in the household economy , (Indigenous Information Network, 2003:25).‣ Develops the capacity of community nominated teachers facilitating theprogrammes in the vicinity of the community (or Manyattas);17

KINNAPA, Kiteto District, Manyara Region - Lessons Learned:The KINNAPA Development Programme, works to support pastoralists & huntergathers’improved socio-economic quality of life through participatory approaches thatemphasise sustainable resource management. Within the context of KINNAPA’seducation focus they have been facilitating communities to establish ECD Centres withintheir communities, as a strategy for ensuring young children’s improved early care andeducation, and thereby, a greater likelihood of their smooth transition to and success informal school. From feedback from Monduli Pastoralist Development Initiatives(MPDI’s) recent exchange visit to the KINNAPA supported ECD centres they highlightedsome key lessons learned, including‣ The ECD centres are meeting points for community activities, supporting youngchildren’s early care and education, as well as adult education and training, projectmeeting areas for women and youth groups, and generally uniting the community(MPDI 2004).‣ The ECD centres emphasise the importance of integrated approaches to supportingyoung pastoralist & agro-pastoralist children’s care & early education, and thereforework to bring education, health, and other service providers closer to children andtheir families.‣ Each ECD Centre is managed by its own parents committee‣ The Centre programmes & teachers are supported through a collaboration betweencommunity and KINNAPA contributions‣ The demand is high, with many communities motivated by others to develop ECDcentres as a key strategy to supporting early care and education, and the successfultransition to formal education.Samburu & Maasailand, Kenya - Lessons Learned:In Samburu and Maasailand, Kenya, Christian Children Services, have been workingwith communities to expand their traditional concept of the ‘loipi’ – ‘meeting point underthe shade’, to incorporate community day-care arrangements for young children. Theseprogrammes have become very successful in their approaches to finding locallyappropriate solutions to improving the quality of child-care at family and communitylevels. Some of the key strengths identified include that these programmes …‣ are owned and managed by the communities themselves;‣ involve grandmothers in their traditional roles of caring for and advising others onthe best care practices for infants and young children;19

‣ are resourced with locally made teaching/learning materials that bring communityculture into the care & learning environments;‣ provide two nutritious meals per day for children‣ actively monitor children’s health;‣ build the capacity of families, including expectant mothers, to provide the adequatehealth, nutrition and intellectual stimulation for their children to realise their fullpotential.20

4. RESEARCH FINDINGS4.1 Challenges & Opportunities IdentifiedEven though the field work period for this research was only a total of ten days acrossnine communities, the research team were able to collate an extensive body of data, dueto the readiness of community members, service providers, ward & district stakeholders,to meet and discuss their dreams and challenges about the care & education of theyoungest children. What has been most fascinating about the collation and analysis ofthe research data, is the fact that whilst the pastoralist communities are facingtremendous obstacles to ensuring the well-being of their children, for all the challengesidentified, the opportunities presented, as indicated by communities suggestions for howthings could be improved, far outweigh the challenges. Therefore, whilst the summarydocument provides an overview, the following charts present a comprehensive reportingof both challenges & opportunities as they were identified by all informants, as areference document for planning. The extensive inclusion of informants quotes, althoughmaking the document lengthy, has been intentional, for the purposes of …• indicating the extent to which the recommendations are woven together from themany threads of ‘ideas’ that the research team heard directly from communities, Ward& District informants;• sharing these as these as potential resource material for future Early Childhood Care& Education lobbying, sensitisation & awareness raising based on existing knowledgewithin the Ward & District.Given the aim and specific objectives of the of the research, the challenges andopportunities are presented under three key areas:-The Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward –Key Challenges & Opportunities Identified …1. … In Families & Communities2. … In Healthcare Services3. … In the existing Community Pre-Schools & Primary SchoolsThe following tables presentTable 7: Overview of Key Challenges IdentifiedTable 8: Challenges & Opportunities Identified21

Table 7: Overview of Key Challenges IdentifiedThe Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward1. … In Families & CommunitiesSummary of Key Challenges1. Communities recognise that the quality of care & early education of their young children is generallynot good, due to a combination of factors. …….1.1 Pastoralists’ livelihoods, family structures, and social and cultural contexts are rapidly changing, withnegative implications for young children’s development,a. women increasingly heavy workloads means that they simply do not have the time to adequatelycare for their children;b. traditional child-care support structures are fading, and the child-care knowledge, beliefs andpractices of younger generations are limitedc. Informal Education at the family & community level is declining, and young children’sopportunities for early learning & socialisation, are less.1.2 Environmental hardships combined with poor access to water & limited food supply are resulting inyoung children’s poor health & nutrition, thus hindering their growth, development and ability tolearn.2. … In Health Care Services2. Health services are inadequate, not accessible and not planning is not informed by reliable data2.1 With dispensaries & clinics 7 - 20kms from communities these services are not accessed by mothers &children on a regular basis.2.2 There is an apparent lack of awareness of some clinic staff to the reality of children’s poor health andwell-being, & a lack of flexibility in how their services could be delivered.2.3 A lack of reliable data on health & nutrition status of young children and mothers in the District, haslimited planning.3. … In the Existing Community Pre-Schools & Primary Schools3.1 Communities’ interest in formal education is increasing, and they are actively mobilising their owncommunity pre-schools to improve the quality of care & early education of their young children,however with the many unresolved challenges of primary schools, they are not sure if the DistrictCouncil will assist them.3.2 Location, facilities & provisions, are challenges for children’s & communities participation, shared byboth community Pre-schools & Primary Schools, but there are key lessons to be learned from preschoolsbased within communities.3.3 Caregivers / Teachers for Community Pre-schools are mostly nominated by communities and theyshare with Primary Teachers the urgent need for specific training in working with young children &their communities3.4 Whilst communities prefer that Kimaasai is the language of community pre-schools and is used in preschool& primary school to teach Kiswahili – this is only possible where Maasai Teachers are involved.3.5 Programme content, approaches & resources, of pre-schools and early years of primary schools arelimited to primary school syllabus & teacher-directed approaches, which do not reflect communityknowledge & beliefs about how children learn or what is important for them to learn3.6 Links Between Community Pre-schools , Health Services & Primary Schools are minimal.22

Table 8: Challenges & Opportunities IdentifiedThe Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward –Key Challenges & Opportunities Identified …1. … In Families & Communities2. … In Healthcare Services3. … In the existing Community Pre-Schools & Primary Schools1.1The Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward –Challenges & Opportunities Identified …1. … In Families & CommunitiesCHALLENGESOPPORTUNITIESPastoralists’ livelihoods, family structures, and social and cultural contexts are rapidly changing, with negativeimplications for young children’s development -a. Women’s increasingly heavy workloads means that they simply do not have the time to adequately care for theirchildren;‘We know how to care for our children, but we have notime.’Women’sGroupThe work-load of women is heavy & timeconsumingwhen they have to walk up to 20kms forwater and the men are away with cattle.‘Because the mothers are busy and they are the onesrequired to teach children– their social roles andculture, we can see the changes in that children do nothave some of the culture components.’Women’s GroupGirls are increasingly involved in school, thereforethey are not available to support their mothers ascaregivers for their young siblings.Women highlighted that it would be very helpful to them if thepreschool programme could be designed so that they have aplace where their children are well cared for while they areoccupied with their work.Some communities are very clear about the attributes of a goodcarer of young children, as someone whoo Is a gentle person,o has good character – not drunkard;o doesn’t shout,o is not rude,o observes childreno explains things to children;o encourages childreno plays with childreno allows children to experiment & experience thingso has children of their ownWomen’s Groups (See Appendix 9)At the time of this research, women from somecommunities were walking 20 kilometres tocollect water, leaving home at 4.00 a.m. andreturning around 3.00 p.m.‘We know how to care for ourchildren, but we have no time!’Women’s Group23

1.1 …continued … Pastoralists’ livelihoods, family structures, and social and cultural contexts are rapidly changing,with negative implications for young children’s development -CHALLENGESOPPORTUNITIESb. traditional child-care support structures are fading, and the child-care knowledge, beliefs and practices ofyounger generations are limitedYounger women lack the traditional knowledge aboutquality child-care practices‘We know some things, but some we have forgotten.’In some communities there is a breakdown in thetraditional support structures for child-care• ‘… bibis used to look after children and tell stories, but wedon’t do that now’Male Elder• Child-care is changing from a shared communityresponsibility to an individual issue.• This situation is particularly serious given the highincidence of early marriages and girls having their firstchild by the age of 15 years (Public Health Nurse)In some communities this means that some children are atrisk of negligence and sometimes abuse, ‘ …. These days thereare lot of changes and you cannot trust people to look after yourchildren like before’Women’s GroupPastoralist men’s current roles in child-care & earlyeducation are unclear.Whilst some men acknowledge the heavy workloads ofwomen especially in times of drought, and when menmigrate, they were not able to consider how they mightadjust their roles and responsibilities in order to get moreinvolved in care of children.In some communities, Grandmothers still have the roleof overseeing / supporting the care of young children,and they play a very active role as key resource peoplein some community pre-school centres. There is anopportunity to engage these female leaders as resourcepeople in community programmes where there are nofemale elders.Build on existing knowledge, practices & beliefs ofcaring for childrenSome community members (especially female elders)have very detailed knowledge about traditionalbeliefs and practices for supporting young children’sdevelopment through different stageso what they require to grow & develop wello and gender variations related to theirsocialisation patterns(See Appendix 9: ‘Community Knowledge & Beliefs aboutthe Care and Education of the Young Children’)Some men expressed a clear interest in developing theroles & responsibilities of men as fathers and teachersof their children.‘We as fathers and teachers, we must be responsible forteaching our children.’Men’s GroupWith the community pre-school,‘At least we have a place for the childrento play and be safe while we are lookingfor water.’Women’s Group24

1.1 …continued … Pastoralists’ livelihoods, family structures, and social and cultural contexts are rapidlychanging, with negative implications for young children’s development -CHALLENGESOPPORTUNITIESc. Informal Education at the family & community level is declining, and young children’s opportunities for earlylearning & socialisation, are less.The actual practice of traditional knowledge & beliefs aboutwhat young children should learn and how they best learn, islimited due to changing social & cultural contexts.‘In the next 50 yrs the life of pastoralists may fade away – we used to havestories that taught us, but we don’t use them now’MaleCommunity Member‘We have realised that informal education is washing away because recentage-groups do not know most of the pastoralist ways, & things like respectamongst our people are drastically changing.’Elder‘Because the mothers are busy and they are the ones required to teachchildren their social roles and culture, we can see the changes in thatchildren do not have some of the culture components..’Women’s GroupThe fact that opportunities for informal education are rapidlydeclining in some communities means that some children do nothave any foundation for starting formal education‘…. Sometimes we get children coming school who do not know thingslike colours and counting in Kimaasai, and they do not know Kiswahili.Culturally they are lost.’Maasai TeacherCommunities have clearly identified the importance of play insupporting young children’s learning, but that boys have moreplay opportunities than girls.‘Boys seem to learn faster than girls because when they look after cattle,they meet and play together and learn a lot . But girls don’t get thischance.’Community Pre-school TeacherGirls have duties close to home that limit their opportunities tomeet and play with others in groups.Some elders and community members’knowledge & beliefs provide a rich resource forsupporting the development of early care andearly education programmes• How Children Learn: Young children learnbyo being around everyday activitieso being included and shown how to dothings by adults and siblingso observingo imitatingo by being given specific tasks andopportunities to practice them. e.g. go upto there with the cows for a 4 year old boy;o by being allowed to make mistakes‘ If you beat them too much ….. you are notallowing mistakes, so they can’t learn. ’Women’s Groupo playing –boys pretend play with stonesfor cows; football; girls – make clay dolls,cooking games etc;o laughing with them• What Young Children Should Learno Maasai cultureo Traditional values & respect of agegroupingso Kimaasai languageo Their gender roles, responsibilities andassociated skills within the family&community contextWhilst elders highlighted that informal education practicesare’ washing away’, communities believe that young childrenlearn by …• being around everyday activities & encouraged toparticipate in them, by adults and siblings;• by being shown how to do things, and having thingsexplained to them, by adults and siblings;• by observing and imitating;• by being encouraged to try & practice real tasks• by being allowed to make mistakes• playing• experimenting & experiencing things• adults and siblings laughing with them‘What communities areidentifying as approachesto children’s learning issimilar to modern theoriesof children’s learning andactive participation.’Monduli Teacher TrainingCollege Official25

1.2 Environmental hardships combined with poor access to water & limited food supply are resulting in youngchildren’s poor health & nutrition, thus hindering their growth, development and ability to learn.CHALLENGESOPPORTUNITIESa. Lack of accessible, clean water supplies• women are walking up to 20 km to get water• the harsh dusty environment has lead to Mondulihaving the second highest incidence of Trachomain Tanzania, even among children (WHO, SAFE,2005)Plans that are underway for improved water access inMonduli District should include provision at communitypre-schools, schools and clinics.b. Limited supply & poor quality of foodWomen identified that with the water scarcity,° cows’ milk production is very low, & poor quality,therefore children’s diet is poor° children and families are not able to eat on aregular basis;° if they have access to food sources such as maize &beans, they prepare Ugali (made with milk fat),milk chai, maize boiled with salt, for children BUTthey know that this is not enough for growingchildrenDistrict Agriculture official highlighted thato There is a critical link between nutrition, mental andphysical health.o The women & children are the most affected bynutrition limitationso Plans are underway for a cross-sectoral approachesto addressing food insecurity in the district. (TPRA& SNV, 2003)A Traditional Elder explains traditional informal education:‘When a child starts to play a game withstones as cows, for example, mzee starts touse this opportunity to start teaching himhow to take care of the cows. He sees theboy take big stones and small ones, and sothey talk about cows (big stones) and theircalves (smallstones). Mzeeteaches themmany things,like how tokeep the cows,and where toput the boma, and the children practice these ideas as theyplay in the soil with stones and sticks. He teaches themeverything, even how to take care of the livestock, andthings like that it is very important for the calf to have thefirst milk from its mother. This is working because if you ask children to sing songstaught to them by bibi they can’.Traditional Elder26

The Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward –Challenges & Opportunities Identified….2. … In Health Care ServicesCHALLENGESOPPORTUNITIES2.1 With dispensaries & clinics 7 – 20kms from communities these services are not accessed by mothers & childrenon a regular basis.oosome women do attend MCH clinics, but not on aregular basis;ailments for pre-school and school age children tend tobe initially treated at home – accessing clinics only foremergencies.Clinic StaffA village Chairperson in a WDC meeting asked of theDistrict Council,‘Where are the social services for children in Sepeko Ward?’Village Chairperson2.2 There is an apparent lack of awareness of some clinic staff tothe reality of children’s poor health and well-being, & a lackof flexibility in how their services could be deliveredFor example,° despite the drought conditions, limited food supply etc,one clinic staff member indicated that no-one was visitingthe clinic on that day because ‘..all the children are healthy.’° Whilst the long distances between bomas & clinics meansthat children are not accessin g these services, only onecommunity pre-school reported that clinic staff havevisited the centre where children ARE gathered• Expand existing mobile Mother ChildHealth service to include community preschoolsas a meeting point for MCH issues• Village / Community Health Workersprogrammes to be stren gthened & mobilised• Include a comprehensive mapping of socialservices in relation to communities inDistrict Health & Nutrition on study (see 2.2below)• TBAs assist most women to deliver at homeand are highly respected in communities• Community pre-schools are an opportunityfor clinic staff & village health workers too meet with young children fro check-upson a regular basiso develop and maintain strongrelationships with the TBAs, who are wellrespected in pastoralist communities, andactively involved in some communitypre-schools2.3 Lack of reliable data on health & nutrition status of young children and mothers in the District, is limitingplanning for improved early care & education support.a. Clinic staff & District officials indicated that the lack ofreliable data is due to the fact that communities are notaccessing the health centres.b. The inter-related factors contributing to children’s poorhealth & nutrition status have not been systematicallydocumented to improve multi-sectoral planning, e.g.o with water scarcity, children’s diet is poor , and familiesare not able to eat on a regular basis. Women’s Groupo food sources such as maize and beans lack the nutritionalvalue of crops such as sorghum & millet that weretraditionally grown by some pastoralist communities.District officialo food sources are dependent on elements currently out ofreach of many pastoralists - fertile land, sustainableagricultural practices, and adequate rains financialresources.• District officials proposed that a MonduliDistrict health & nutrition study is a priority ,and given that health is a cross-sectoral issue,all sectors should be involved from in thestudy from the beginning (Water, Health,Agriculture, Education, CommunityDevelopment )• <strong>Report</strong> of food security in Monduli (TPRA &SNV, 2003) highlights that food security mustbe addressed multi-sectorally & holistically,with the aim of developing sustainablehuman settlements that are ecologicallysound & economically viable (in terms ofenergy, time & resources) – DistrictAgriculture & Livestock Dev.27

The Early Care & Education of Young Pastoralist Children in Sepeko Ward –Challenges & Opportunities Identified …3 … In the Existing Community Pre-Schools & Primary Schools3.1 Communities’ interest in formal education is increasing, and they are actively mobilising their own communitypre-schools to improve the quality of care & early education of their young children, however with the manyunresolved challenges of primary schools, they are not sure if the District Council will assist them.Community Pre-schoolsPrimary SchoolsCHALLENGESGovernment has emphasised the need forpartnership approaches to supportingcommunity –based early care & education, andpastoralist communities are actively mobilisingtheir own community -based pre-schools formultiple purposes. However, they are not sure towhat extent the District Council will assist them.As the Ministry of Education & Culture hasindicated,° ‘The success of this (partnership) model ofdevelopment will depend on the willingness andeconomic capacity for the communities concerned’,Communities’ level interest in formal education is increasing butthe challenges are discouraging° long distances to schools (for both children & parents)° lack of water & food at school° content & approaches are not locally appropriate, andcommunities fear that by their children going school they willlose their cultural identity.° A number of primary schools in Sepeko Ward are strugglingwith low Std 7 pass rates‘ … one of our primary schools was the last in the country in2004.We can’t let our children go on until Std 7 and then just fail’Village Chairperson° ‘… there is an inherent risk in depending on theefforts of communities alone. (MOEC, 2001,Basic Education Master Plan, 2001 - 2005)All community pre-schools have ManagementCommittees in place, but they have had nospecific training to assist their planning andensure that the pre-schools meet their specificneeds.Some community members are unsure whether they have tochose between formal education & informal, or if its possible tohave bothA number of schools in Sepeko Ward are struggling with, lackof regular attendance & low Std 7 pass rates‘ … one of our primary schools was the last in the country in2004.We can’t let our children go on until Std 7 and then just fail’Village ChairpersonOPPORTUNITIESCommunities’ level of interest in their pre-schools is high indicated by• the growing number of active centres over the past two years• children’s regular participation, especially in those closer to bomas• the fact that all have Pre-school Committees in place that are stronglylinked to local government structures – which provides an additionalopportunity for their capacity development to support pre-schooldevelopment & later primary school participationCommunities in Sepeko Ward ARE actively mobilising their owncommunity pre-school centres, closer to home, for …• supporting women through providing day -care for their childrenwhile they are involved in the their work ‘At least we have a place forthe children to play and be safe while we are looking for water.’Women’s Group• ensuring young children’s quality day -care and ongoing informaleducation• being extended to include programmes for children up to the ageof 8 / 9 years, after which they are old enough to walk the longdistances to primary school;• supporting their children’s preparation for success in primaryschool.• possibly a primary school being located where their pre-school is.This provides other cross-sectoral stakeholders with a unique opportunityto work in collaboration with themCommunities ARE interested in formaleducation‘Pastoralist families are interested in formalschool because they can see it is helping them, forexample, some of our educated ones havereturned and are helping our communities.’Traditional LeaderPrimary Teachers indicted that childrenentering school with pre-school experienceare better prepared for school.The high success rate of LosimingoriPrimary School provides an opportunityfor further study in order to document &share the lessons to be learned. – thisschool has recorded an enrolment rate ofalmost 94% of children within vicinity ofthe school, 99% Std 7 pass rate in 2004 – 23of 24 Std 7 students. Eight of these weregirls and all of them have gone on tosecondary school28

3.2 Location, facilities & provisions, are challenges for children’s & communities participation, shared by bothcommunity Pre-schools & Primary Schools, but there are key lessons to be learned from pre-schools basedwithin communities.Community Pre-schoolsPrimary SchoolsCHALLENGESLocation & children’s participationOnly a two community pre-schools are located closeto bomas,° some are between 2 – 4 kms away;° two are located at primary schools between 6 –10kms away – where the distance is already aproblem for older children.The number, and age range of childrenparticipating in Community Pre-school Centres isdependent on their location° Centres close to bomas – more children widerage-range:- 2 / 3 years – 8/9years;° Centres further from bomas – less childrennarrower age range:- 4/ 5 years – 8/9 yearsFacilities° Centres further from the bomas tend to behoused in more permanent structures owned byothers, or have no shelter at all.° No centres have sanitation facilities for youngchildren or adults – except the two located atprimary schools, where there are commonfacilities.Location & children’s participationMany primary schools are struggling with issues of pastorlistchildren’s enrolment and regular attendance due to acombination of issues - long distances to school(up to 10 kms),no water of food provision at school, and the lack of rele<strong>van</strong>ce ofschool programmes to pastoralist communities etc.‘Our children have to walk almost 10 kms to school. During therainy season some areas are flooded so children can’t reach school –its dangerous. So they miss blocks of time and then they can’t catchup.’Male School Committee memberThe age range of children in Std 1 is between 7 and 10 years,with distance being a key factor‘If we had a choice we would like our children to start school later,because its just too far for 7 years olds.’Female Pre-school Committee MemberFacilitiesMost Primary Schools° classroom facilities & school environments areuninviting & not child-friendly° appear to exclude children with disabilities – with noalternative structures in place° teachers’ housing is inadequateProvisions – water & foodAll Community Pre-Schools & most Schools have little or no water or food provision, which contributes to children’so Poor health, sanitation & nutrition -‘Children are weak at school because they do not have any breakfast and no food until they go home.’ Teachero Limited brain functioning -‘Lack of food at home and at school is another big problem why children are not registered. & for those who attend – itaffects their concentration.’Head TeacherSome primary schools expect children to° bring water from home, ‘If you don’t give water & firewood for your child to take to school, they will not go’Female Pre-school Committee Member° to use school time to go & collect water for teachers and school use after have already walked long distances toschoolThere are some outstanding issues regarding the sustainability of World Food Programme provision of food in schools inMonduli District, includingo the promised de-worming of all children has not yet happened in all schoolso it is assumed that schools have water supplies, and can provide cooking facilities, firewood and pay the cook (noadditional provision made during the drought )o limited opportunities for discussion with WFP about what food is provided;o provision of food to schools is not a guarantee that children are always the recipients of this food;OPPORTUNITIES …. Continued Over Page …29

3.2 Location, facilities & provisions, are challenges for children’s & communities participation, shared by bothcommunity Pre-schools & Primary Schools, but there are key lessons to be learned from pre-schools basedwithin communities.Community Pre-schoolsPrimary SchoolsOPPORTUNITIESCommunity pre-schools located close to bomas• Have more children participating – both girls & boys& some children with disabilities• Include a wider age –range of children involved, fromage of 2 years• Meet women’s needs for day -care for their youngchildren• Have more community involvement & a stronger senseof ownership• Recognise that they can be flexible with programmehours (depending on seasonal variations, women’sneeds etc).• Have participation of elders as resource people• Have a teacher nominated from within the community• Are an integral part of community culture & events‘Whilst community members spoke of the need for schools to belocated within communities so that children do not lose theirculture, this alone is not enough. The community must alsocommit resource people to the programme to facilitate this.’Traditional LeaderThere are pre-schools located within communities that arevery creative examples of the use of local materials, tocreate centres for children and communities that reflectcommunity culture.Communities mobilization of their own Pre-schoolCentres in Sepek o Ward is a key opportunity for thepiloting of the Ministry of Education & Culture’s ideaof satellite schools, by extending the Centres toinclude programmes for Std 1 & 2 children• that are developed through collaboration betweencommunities, schools & officials• that ensure pastoralist children’s ongoingdevelopment in their informal education & cultureAS WELL AS their smooth transition to & success inprimary school‘If primary schools .(are) .. closer to the bomas thencommunities can be more involved in the school, and theschool can learn from the community.’Male Community MemberGiven that more children ARE participating incommunity pre-schools on a regular basis, AND theproblems of long distances to primary schools – thepre-school centres offer a key opportunity to beextended to include Std 1 & 2 primary yearsprogrammes, developed through collaboration with theneighbouring primary schools (as suggested throughthe Ministry of Education & Culture’s Satellite Schoolconcept – see Issue 3 below)‘If we had a choice we would like our children to startschool later, because its just too far for 7 years olds.’Female Pre-school Committee MemberDistrict officials have identified community pre-schools & schools as key sites for the development of experimentalgardens, as a way of a) Introducing alternative drought resistant crops that have a high nutrition level – e.g. sorghum& millet; b) Influencing sustainable community agricultural practices.‘If we had a choice we would like our children to start school later,because its just too far for 7 years olds.’Female Pre-school Committee Member‘If primary schools .(are) .. closer to the bomas then communities can be moreinvolved in the school, and the school can learn from the community.’Male Community Member30