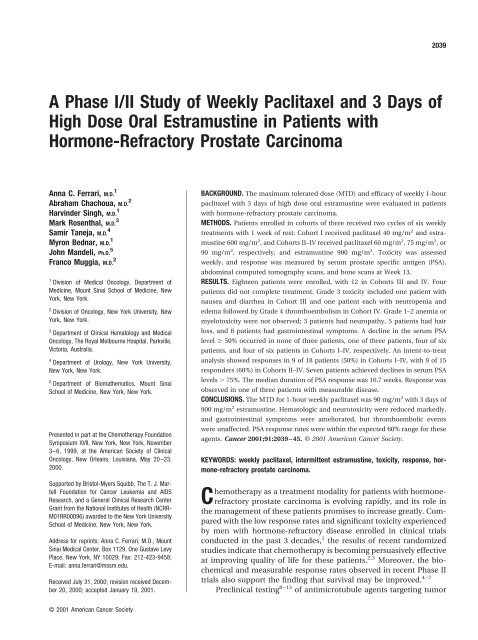

A Phase I/II study of weekly paclitaxel and 3 days of high dose oral ...

A Phase I/II study of weekly paclitaxel and 3 days of high dose oral ...

A Phase I/II study of weekly paclitaxel and 3 days of high dose oral ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

2040 CANCER June 1, 2001 / Volume 91 / Number 11cells in mitosis <strong>and</strong> interphase indicated that the limitedactivity <strong>of</strong> estramustine <strong>and</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> as singleagents could become synergistic against <strong>and</strong>rogen independentprostate carcinoma cells. 14 When 96-hourinfusions <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> at 120 mg/m 2 every 21 <strong>days</strong>were given with continuous <strong>oral</strong> estramustine at 600mg/m 2 for 21 <strong>days</strong> in patients with hormone-refractoryprostate carcinoma, Hudes et al. 15 observed adecline in the level <strong>of</strong> serum prostate specific antigen(PSA) 50% in 53% <strong>of</strong> patients <strong>and</strong> measurable diseaseresponses in 44% <strong>of</strong> patients lasting a median <strong>of</strong>22 weeks. The spectrum <strong>of</strong> toxicity included 21% <strong>of</strong>patients with Grade 3 <strong>and</strong> 4 granulocytopenia <strong>and</strong>neuropathy attributed primarily to <strong>paclitaxel</strong> <strong>and</strong> 10%<strong>of</strong> patients with serious gastrointestinal <strong>and</strong> thromboticcomplications attributed primarily to estramustine.A similar spectrum <strong>of</strong> toxicity <strong>and</strong> response rateswere described by Petrylak et al. 7 with one infusion <strong>of</strong>docetaxel at 75 mg/m 2 <strong>and</strong> 5 <strong>days</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine at840 mg every 21 <strong>days</strong>.To improve on these regimens, it became a priorityto decrease toxicity <strong>and</strong> maintain or improve responserates. One approach was to modify the frequency,<strong>dose</strong>, <strong>and</strong> length <strong>of</strong> administration <strong>of</strong> eachdrug. Preclinical data 16 <strong>and</strong> clinical data 17,18 supportedthat <strong>weekly</strong> 1-hour infusions <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> 100 mg/m 2 could be as effective as <strong>high</strong>er <strong>dose</strong>s atinducing tumor cell death <strong>and</strong> clinical response withsubstantially less side effects. New information concerningan intermittent schedule <strong>of</strong> estramustine becameavailable when the results <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Phase</strong> I <strong>study</strong> 19 <strong>of</strong>3 <strong>days</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>oral</strong> estramustine at 900 mg/m 2 or 1200mg/m 2 <strong>and</strong> 3-hour infusions <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> at 100mg/m 2 or <strong>high</strong>er every 21 <strong>days</strong> were analyzed. In this<strong>study</strong>, gastrointestinal side effects were reduced,whereas clinical responses were observed in 4 <strong>of</strong> 15<strong>and</strong> in 6 <strong>of</strong> 14 heavily pretreated women with refractorybreast <strong>and</strong> ovarian carcinoma, respectively.These studies gave backing to a <strong>Phase</strong> I–<strong>II</strong> clinicaltrial to assess the maximum tolerated <strong>dose</strong> (MTD)safety <strong>and</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>weekly</strong>, 1-hour infusions <strong>of</strong> escalating<strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> <strong>and</strong> a brief, intermittentschedule <strong>of</strong> <strong>oral</strong> estramustine in patients with hormonerefractory prostate carcinoma.MATERIALS AND METHODSStudy DesignTo determine the MTD, safety, <strong>and</strong> efficacy <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong><strong>and</strong> estramustine in this modified schedule, weused a <strong>Phase</strong> I–<strong>II</strong> design. The initial plan was to havea maximum <strong>of</strong> six cohorts <strong>of</strong> three patients. Eachcohort would be treated with an incremental <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong><strong>paclitaxel</strong> starting at 40 mg/m 2 . Oral estramustine initiallywas planned to be given at 600 mg/m 2 based onthe existing experience with this <strong>dose</strong>. However, soonafter the first cohort <strong>of</strong> patients had been enrolled, theresults <strong>of</strong> our <strong>Phase</strong> I <strong>study</strong> 19 became available, suggestingthat 900 mg/m 2 may be required for activity <strong>of</strong>estramustine on a brief, intermittent schedule. Therefore,the protocol was amended to increase the <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong>estramustine to 900 mg/m 2 from Cohort <strong>II</strong> onward.Each cohort would receive a minimum <strong>of</strong> 12 consecutiveweeks <strong>of</strong> therapy with a break on Week 7. Thecohort would be exp<strong>and</strong>ed by three additional patientsat the same <strong>paclitaxel</strong> <strong>dose</strong> level if one patientdeveloped Grade 3 or 4 toxicity. The MTD would bereached if two patients in a given cohort experiencedGrade 3 or 4 toxicity. At this point, no further <strong>dose</strong>escalation would be allowed.Patient SelectionEligible patients had a histologic diagnosis <strong>of</strong> adenocarcinoma<strong>of</strong> the prostate with progressive systemicdisease despite at least two endocrine manipulations.One <strong>of</strong> the manipulations included either orchiectomy,a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone(LHRH) analogue with or without anti<strong>and</strong>rogens,megesterol acetate, or diethylstilbestrol. For patientson an anti<strong>and</strong>rogen, discontinuation <strong>of</strong> the agent wasrequired as a second hormonal manipulation for aminimum <strong>of</strong> 4 weeks with evidence <strong>of</strong> subsequentrising PSA level or progressive, measurable disease.Patients were required to have a minimum life expectancy<strong>of</strong> 3 months <strong>and</strong> an Eastern Cooperative OncologyGroup performance score 2. Additional requirementswere adequate hepatic <strong>and</strong> renal function,granulocyte count 1500/L <strong>and</strong> platelet count 100,000/L. Patients were required to be at least 3weeks beyond surgery, recovered from infectious process,<strong>and</strong> have no significant active medical illnessthat would preclude protocol treatment or survival.Prior radiation to a symptomatic metastatic site thatwas not the only measurable or evaluable lesion wasallowed. Radiation therapy <strong>and</strong> corticosteroids had tobe completed at least 2 weeks before therapy. Hydronephrosiswith impaired renal function had to be adequatelydecompressed. Patients with central nervoussystem metastasis, unstable angina, uncontrolled congestiveheart failure, or arrhythmia were excluded. Allpatients were required to sign informed consent inaccordance with institutional, state, <strong>and</strong> federal guidelines.Evaluation CriteriaA complete history <strong>and</strong> physical examination withcomplete blood count, serum chemistry pr<strong>of</strong>ile, <strong>and</strong>PSA level were performed at baseline, in Week 7, <strong>and</strong>in Week 13. Radionuclide bone scans <strong>and</strong>, computed

Weekly Paclitaxel/Estramustine in HRPC/Ferrari et al. 2041tomography (CT) scans <strong>of</strong> the abdomen <strong>and</strong> pelviswere required at baseline <strong>and</strong> at the end <strong>of</strong> the <strong>study</strong>or as indicated by biochemical or clinical progression.Clinical evidence <strong>of</strong> toxicity <strong>and</strong> complete bloodcounts were assessed <strong>weekly</strong>.Treatment ProgramTherapy was administered in the outpatient setting.All patients continued on a LHRH agonist. Paclitaxelwas given as a <strong>weekly</strong> 1-hour intravenous infusion fortwo cycle <strong>of</strong> 6 weeks, with a break on Week 7. The <strong>dose</strong>escalations <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> planned for each cohort were40 mg/m 2 , 60 mg/m 2 , 75 mg/m 2 , 90 mg/m 2 , 100 mg/m 2 ,<strong>and</strong> 110 mg/m 2 . Two <strong>days</strong> preceding the <strong>paclitaxel</strong>infusion, patients began a 3-day course <strong>of</strong> <strong>oral</strong> estramustinegiven in three divided <strong>dose</strong>s 1 hour before or2 hours after meals. The <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine was 600mg/m 2 per day for patients in Cohort I; however,starting with Cohort <strong>II</strong>, it was raised to 900 mg/m 2 perday in an attempt to decrease toxicity <strong>and</strong> maintainefficacy. One hour before <strong>paclitaxel</strong> infusion, patientsreceived intravenous diphenhydramine 50 mg, ranitidine50 mg, <strong>and</strong> dexamethasone 20 mg, which wasreduced subsequently to 8 mg if no reactions wereobserved. At the discretion <strong>of</strong> the treating physician,responding patients were <strong>of</strong>fered an opportunity tocontinue on the same regimen after the <strong>study</strong> period.Toxicity <strong>and</strong> Response CriteriaToxicity was graded according to the revised NationalCancer Institute common toxicity criteria. Efficacy was20 –22assessed by changes in PSA levels, changes inmeasurable disease (assessed by CT scans <strong>of</strong> the abdomen<strong>and</strong> pelvis <strong>and</strong> chest X-rays), <strong>and</strong> changes inevaluable disease (assessed on bone scans). A completebiochemical response was defined as normalization<strong>of</strong> PSA levels ( 4.0 ng/mL), a partial responsewas defined as a decline in PSA levels 50% frombaseline values, <strong>and</strong> disease progression was definedas rising PSA levels 50% above baseline values. Stabledisease was defined as PSA changes that did not meetthe criteria for partial response or disease progression.PSA responses required confirmation on a second determinationat least 2 weeks apart. Measurable diseasewas assessed in bidimensionally measurable lesionswith clearly defined margins by imaging X-rays <strong>and</strong>scans. A complete response was defined as the resolution<strong>of</strong> all measurable masses <strong>and</strong> the absence <strong>of</strong>any lesions or anomalies, a partial response was definedas a reduction 50%, <strong>and</strong> a minor response wasdefined as a reduction between 25% <strong>and</strong> 50% in themeasurable lesions.The duration <strong>of</strong> response 23 was calculated fromthe date <strong>of</strong> PSA decline 50% from the initiation <strong>of</strong>TABLE 1Patient CharacteristicsCharacteristicNo. eligible patients 18No. evaluable 18RaceAfrican American 8Caucasian 8Others 2Median age in yrs (range) 69 (44–76)ECOG performance status0 171 12 0Sites <strong>of</strong> metastasesBone only 15Bone <strong>and</strong> s<strong>of</strong>t tissue 3Median baseline PSA (range) 111 (38–2853)Median no. <strong>of</strong> hormonal therapies (range) 2 (2–4)Prior chemotherapy (%) 3 (16.7)Prior radiotherapy (%) 11 (61.1)ECOG: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; PSA: prostate specific antigen.treatment to the date <strong>of</strong> 50% increase above the nadirPSA value or an increase 25% in the smallest sum <strong>of</strong>all tumor measurements obtained during the best response.Response was analyzed on an intent-to-treatbasis for all patients enrolled in the <strong>study</strong> <strong>and</strong> forthose in Cohorts <strong>II</strong>–IV who received the same <strong>high</strong><strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine.RESULTSPatient CharacteristicsThe pretreatment characteristics <strong>of</strong> the 18 patients arelisted in Table 1. The median age was 69 years (range,44 –76 years). There were eight African-American patients,eight Caucasian patients, <strong>and</strong> two Hispanic patients.Seventeen patients had a performance status <strong>of</strong>0, <strong>and</strong> only 1 had a performance status <strong>of</strong> 1. Themedian baseline PSA level was 111 ng/mL (range,38 –2853 ng/mL). Eighteen patients had bony metastasis,<strong>and</strong> 3 had pelvic lymph node enlargement. Nonehad parenchymal organ involvement. At <strong>study</strong> entry,all patients had evidence <strong>of</strong> disease progression byrising PSA levels after two hormonal manipulationsthat included anti<strong>and</strong>rogen withdrawal for 4 – 6 weeks.Three patients had received prior chemotherapy, <strong>and</strong>11 patients had received radiation to a metastatic site.Patient Distribution Among CohortsThe three patients in Cohort I were enrolled to receive<strong>paclitaxel</strong> 40 mg/m 2 <strong>and</strong> estramustine 600 mg/m 2 . Allpatients completed two cycles <strong>of</strong> therapy. In Cohort <strong>II</strong>,three patients were enrolled to receive <strong>paclitaxel</strong> 60No.

2042 CANCER June 1, 2001 / Volume 91 / Number 11TABLE 2Distribution <strong>of</strong> Toxicity Events by Type <strong>and</strong> GradeToxicityGrade1 2 3 4Neuropathy 2 1 0 0Musculoskeletal 1 0 0 0Alopecia 3 2 0 0Neutropenia 0 0 1 0Phlebitis a 0 4 0 0Edema 0 0 1 0Thrombosis/embolism 0 0 0 1Nausea 3 3 1 0Emesis 2 0 0 0Diarrhea 0 0 1 0a Phlebitis refers to induration <strong>and</strong> erythema at the site <strong>of</strong> intravenous infusion.mg/m 2 with estramustine 900 mg/m 2 . One patient waslost to follow-up after 5 weeks <strong>of</strong> treatment. Two patientscompleted two cycles. For Cohort <strong>II</strong>I, six patientswere enrolled to receive <strong>paclitaxel</strong> 75 mg/m 2with estramustine 900 mg/m 2 . The cohort was exp<strong>and</strong>ed,because one patient developed Grade 3 nausea<strong>and</strong> diarrhea, requiring treatment interruption.Five patients completed two cycles. In Cohort IV, sixpatients were enrolled to receive <strong>paclitaxel</strong> 90 mg/m 2with estramustine 900 mg/m 2 . The cohort also wasexp<strong>and</strong>ed, because 1 patient developed Grade 3edema with pulmonary embolism during the secondweek <strong>of</strong> the first cycle <strong>and</strong> was removed from protocol.One patient discontinued therapy after 4 weeks, <strong>and</strong>one patient developed Grade 3 neutropenia. Four patientscompleted two cycles.According to the MTD criteria, no further escalationswere made after Cohort IV. In summary, 14patients completed two cycles <strong>of</strong> therapy, <strong>and</strong> 4 patientsdid not complete the first cycle.Toxicity AssessmentToxicity could be evaluated in all patients enrolled inthe <strong>study</strong>, because the discontinuation <strong>of</strong> treatment infour patients occurred after they had started treatment.Overall, there were no therapy-related deaths. Adetailed account <strong>of</strong> the spectrum <strong>of</strong> toxicity <strong>and</strong> thenumber <strong>of</strong> patients for each grade <strong>of</strong> toxicity are listedin Table 2. Grade 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 paresthesias were observedin three patients, <strong>and</strong> Grade 1 musculoskeletal symptomswere documented in another patient. Partial loss<strong>of</strong> hair was seen in five patients. There was only onepatient with Grade 3 neutropenia without febrile complications.At the time <strong>of</strong> enrollment, 17 patients hadGrade 1 <strong>and</strong> 2 anemia secondary to prolonged <strong>and</strong>rogenablation <strong>and</strong> chronic disease. There were no newTABLE 3Distribution <strong>of</strong> Grade 3 <strong>and</strong> 4 Toxicity Events among Cohorts<strong>II</strong>I <strong>and</strong> IVToxicity Cohort <strong>II</strong>I Cohort IVNeutropenia 0 1Edema 0 1Thrombosis/embolism 0 1Nausea 1 0Emesis 0 0Diarrhea 1 0patients with Grade 1 or 2 anemia or progression <strong>of</strong>anemia during therapy. Four patients had superficialphlebitis with erythema at the site <strong>of</strong> intravenous injectionwithout evidence <strong>of</strong> deep vein thrombosis,which resolved with local therapy. One patient hadGrade 3 lower extremity edema <strong>and</strong> subsequently developeda pulmonary embolism with pleuritic chestpain <strong>and</strong> shortness <strong>of</strong> breath without hemodynamiccomplications. Symptoms improved rapidly with st<strong>and</strong>ardanticoagulation treatment with heparin <strong>and</strong> warfarin,<strong>and</strong> the patient was removed from <strong>study</strong>. Nauseawas the most common gastrointestinal symptom<strong>and</strong> was experienced by six <strong>of</strong> seven patients as Grade1–2 <strong>and</strong> by one patient as Grade 3. Grade 2 emesis wasseen in two patients, <strong>and</strong> Grade 3 diarrhea was experiencedby one patient.Overall, there were four events <strong>of</strong> Grade 3 toxicity<strong>and</strong> one event <strong>of</strong> Grade 4 toxicity. Table 3 summarizedthe number <strong>of</strong> Grade 3– 4 toxicity events by cohort.There was one patient with Grade 3 nausea <strong>and</strong> diarrheain Cohort <strong>II</strong>I, <strong>and</strong> one patient with Grade 3 neutropenia<strong>and</strong> one patient with edema <strong>and</strong> pulmonaryembolism in Cohort IV.PSA ResponseTable 4 summarizes the clinical responses for eachcohort according to PSA criteria <strong>and</strong> intent-to-treatanalysis results. Cohort I had one patient with stablePSA levels <strong>and</strong> two patients with PSA progression.Cohort <strong>II</strong> had one patient who was lost to follow upafter 5 weeks <strong>of</strong> treatment, one patient had PSA progression,<strong>and</strong> one had PSA decline 75%. In Cohort<strong>II</strong>I, one patient was removed early, one patient hadstable PSA, one patient had PSA decline 50%, <strong>and</strong>three patients had PSA decline 75%. In Cohort IV,two patients were removed early, one patient had PSAdecline 50%, <strong>and</strong> three patients had PSA decline 75%.The PSA response rate estimated on the basis <strong>of</strong>the intent-to-treat analysis showed that 9 <strong>of</strong> 18 patients(50%) enrolled in the <strong>study</strong> had a PSA decline

Weekly Paclitaxel/Estramustine in HRPC/Ferrari et al. 2043TABLE 4Prostate Specific Antigen Response by CohortCohort Paclitaxel Estramustine No.Treatmentdiscontinued Progressed StablePSA decline> 50%Intent to treatresponse (%)I 40 600 3 0 3 0 0 0 <strong>of</strong> 3<strong>II</strong> 60 900 3 1 1 0 1 1 <strong>of</strong> 3<strong>II</strong><strong>II</strong> 75 900 6 1 0 1 4 4 <strong>of</strong> 6IV 90 900 6 2 0 0 4 4 <strong>of</strong> 6Total — — 18 4 4 1 9 9 <strong>of</strong> 18 (50)PSA: prostate specific antigen. 50%. Because the group <strong>of</strong> patients in Cohorts <strong>II</strong>–IVreceived a <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine 1.5 times greater thanCohort I, <strong>and</strong> this alone may have affected the PSAresponse irrespective <strong>of</strong> the <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>, we alsoanalyzed them as a group. The intent-to-treat analysisshowed that 9 <strong>of</strong> 15 patients (60%) had a PSA decline 50%; in 7 patients, the decline was 75%. Themedian duration <strong>of</strong> response (n 9 patients) was 16.7weeks, with a range from 3 weeks to 48.6 weeks.Fifteen <strong>of</strong> 18 patients (83%) had metastatic diseaselimited to bone, including 12 patients in Cohorts <strong>II</strong>–IV.Seven <strong>of</strong> these patients (58%) experienced PSA decline 50% from baseline. Stabilization with mild improvementwas reported in two patients. Three patients hadmeasurable disease to lymph nodes, one patient had ameasurable response with a PSA decline 75%, anotherpatient had no response with a PSA decline 50%, <strong>and</strong> one patient did not complete therapy.Bone scan abnormalities persisted in all patients.DISCUSSIONIn this report, we present the toxicity pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong> response<strong>of</strong> patients with hormone-refractory prostatecarcinoma to a new schedule <strong>and</strong> <strong>dose</strong> range <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong><strong>and</strong> <strong>oral</strong> estramustine. This regimen was basedon previous experience with other tumors suggestingthat more frequent 24,25 <strong>and</strong> lower <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>, 17,26as well as intermittent but <strong>high</strong>er <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> estramustine,19 could improve the toxicity pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>of</strong> each drugwithout compromising their synergistic activity.Therefore, <strong>weekly</strong> 1-hour infusions <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> weregiven in escalating <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> 40 mg/m 2 , 60 mg/m 2 ,75mg/m 2 , <strong>and</strong> 90 mg/m 2 combined with 3 <strong>days</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>oral</strong>estramustine. The <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine, which wasestablished at 600 mg/m 2 in the original design <strong>and</strong>was received by patients in Cohort I along with 40mg/m 2 <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>, was increased subsequently to900 mg/m 2 <strong>and</strong> fixed at that level for all subsequent<strong>paclitaxel</strong> <strong>dose</strong> levels.The results <strong>of</strong> this trial indicate that the grade <strong>and</strong>spectrum <strong>of</strong> toxicity associated with taxanes in previousstudies <strong>of</strong> this combination 7,15 can be improvedmarkedly. Compared with the 20% <strong>and</strong> 53% incidencerates <strong>of</strong> Grade 3– 4 granulocytopenia, there was onlyone patient without febrile complications in our series.Similarly, there were no new incidents <strong>of</strong> anemiaor worsening <strong>of</strong> preexisting anemia compared with the18% <strong>and</strong> 59% incidence rates reported in the previousstudies, <strong>and</strong> there were no incidents <strong>of</strong> thrombocytopenia.Neurologic <strong>and</strong> musculoskeletal symptoms alsowere infrequent <strong>and</strong> predominantly were Grade 1.Hypersensitivity reactions, arrhythmia, or hypotensionwere not reported during the infusions. The incidence<strong>of</strong> peripheral edema also was reduced markedly.Gastrointestinal complications commonly associatedwith <strong>oral</strong> estramustine 27 were ameliorated butnot eliminated with the brief <strong>and</strong> intermittent schedulethat was used. Despite the <strong>high</strong> <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine,the frequency <strong>and</strong> severity <strong>of</strong> nausea, emesis, <strong>and</strong>diarrhea was low 7,28 <strong>and</strong> was limited to the <strong>days</strong> <strong>of</strong>treatment. This may explain why, compared withother regimens using lower <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> estramustine forprolonged periods <strong>of</strong> time, 28 anorexia <strong>and</strong> weight losswere rare.This treatment schedule did not appear to preventthe development <strong>of</strong> thromboembolic events previouslyreported with regimens containing estramustine,27 as illustrated by the patient who developed apulmonary embolism in the second week <strong>of</strong> therapy.Given the proximity <strong>of</strong> the episode to the initiation <strong>of</strong>therapy, the possibility cannot be excluded that it mayhave been related to the advanced stage <strong>of</strong> the diseaserather than the treatment. Also, because we did notobserve other patients with deep vein thrombosis, <strong>and</strong>recent studies quote 8 –10% thromboembolic eventswith lower 28 <strong>and</strong> intermittent 7 dosing <strong>of</strong> estramustine,we do not have evidence that the <strong>high</strong>er <strong>dose</strong> used inthis trial played a role. In recognizing this risk, prophylaxis<strong>of</strong> thrombosis using low <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> warfarin<strong>and</strong> aspirin currently are included in the treatmentplan <strong>of</strong> new trials containing estramustine. Based on

2044 CANCER June 1, 2001 / Volume 91 / Number 11the fact that Cohort IV required expansion becausethere were two patients with Grade 3 <strong>and</strong> 4 toxicity, weconcluded that the MTD for this regimen had beenreached.A second objective <strong>of</strong> this <strong>study</strong> was to evaluatethe efficacy <strong>of</strong> the combination by PSA response <strong>and</strong>,whenever possible, by measurable disease parameters.The intent-to-treat analysis by PSA response criteriashowed an overall response rate <strong>of</strong> 50%, because9 <strong>of</strong> 18 patients enrolled in the <strong>study</strong> had a PSA decline 50% from baseline. When looking at PSA responserates by cohort, it appears that a <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>between 75 mg/m 2 <strong>and</strong> 90 mg/m 2 was required toachieve synergism with 900 mg/m 2 <strong>of</strong> estramustine.These PSA response rates are <strong>high</strong>er than the 23%rate reported with 24-hour infusions <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> at135–170 mg/m 2 every 3 weeks 29 or <strong>weekly</strong> 1-hour infusions<strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> at 150 mg/m 2 . 30 They also aresuperior to the 14% rate observed with continuousestramustine at 560 – 840 mg daily. 31We took into consideration the facts that the 15patients enrolled in Cohorts <strong>II</strong>–IV had received a 1.5times larger <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine compared with patientsin Cohort I <strong>and</strong> that this alone may have influencedtheir response independent <strong>of</strong> the <strong>dose</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>.The 60% response rate observed in the intentto-treatanalysis reflects the fact that the 9 responderswere among the 15 patients in this group. It is noteworthythat seven <strong>of</strong> these responders had a PSA decline 75% from baseline <strong>and</strong> that the drop in PSAlevels for eight <strong>of</strong> these patients occurred within theinitial 6 weeks <strong>of</strong> treatment, which may have affectedthe median PSA response duration determination 23 <strong>of</strong>16.7 weeks, because, at the time <strong>of</strong> first evaluation <strong>of</strong>response, PSA levels had decreased beyond 50%.Although they were limited because <strong>of</strong> the nature<strong>of</strong> the <strong>study</strong>, the PSA response rates observed in theintent-to-treat analysis were within the 53% <strong>and</strong> 63%response rates reported previously with either <strong>paclitaxel</strong>or docetaxel every 3 weeks <strong>and</strong> continuous orintermittent lower <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> estramustine. 7,28 The timeto response <strong>and</strong> duration <strong>of</strong> response also were withinthe 8 weeks <strong>and</strong> 20 –22 weeks observed, respectively,in those studies.We also evaluated whether there was any evidence<strong>of</strong> response in bone metastasis or measurabledisease. Like what is seen frequently with metastaticbone disease in patients with hormone-refractoryprostate carcinoma, we observed decreased intensity<strong>of</strong> bony lesions in two patients, but no decrease in thenumber <strong>of</strong> bone lesions was observed. We did observea partial response in one patient with measurabledisease to the lymph nodes, whereas the PSA level haddeclined more than 75%. These preliminary observationssuggest that measurable responses also may beexpected with this schedule after a decline in the PSAlevel 50%. 15This <strong>study</strong> supports the finding that the MTD <strong>of</strong><strong>paclitaxel</strong> in a <strong>weekly</strong> 1-hour infusion schedule is 90mg/m 2 with intermittent estramustine at 900 mg/m 2for 3 <strong>days</strong>. The current schedule had markedly improvedhematologic <strong>and</strong> neurotoxicity pr<strong>of</strong>ile <strong>and</strong>milder gastrointestinal side effects compared with<strong>high</strong>er <strong>dose</strong>s <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> at 3-week intervals <strong>and</strong> continuousestramustine in patients with hormone-refractoryprostate carcinoma. In terms <strong>of</strong> efficacy, biochemicalresponses were similar for either 75 mg/m 2or 90 mg/m 2 <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>, <strong>and</strong> the response ratespromise to be within the 50 – 60% range expected forthese agents. Therefore, the improved toxicity pr<strong>of</strong>ile<strong>and</strong> potential efficacy <strong>of</strong> this schedule supports a<strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> <strong>study</strong> incorporating prophylactic measures todecrease the incidence <strong>of</strong> thromboembolic complications.REFERENCES1. Yagoda A, Petrylak D. Cytotoxic chemotherapy for advancedhormone-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer 1993;71(3Suppl):1098 –109.2. Tannock IF, Osoba D, Stockler MR, Ernst DS, Neville AJ,Moore MJ, et al. Chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plusprednisone or prednisone alone for symptomatic hormoneresistantprostate cancer: a Canadian r<strong>and</strong>omized trial withpalliative end points. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:1756 – 64.3. Kant<strong>of</strong>f PW, Halabi S, Conaway M, Picus J, Kirshner J, HarsV, et al. Hydrocortisone with or without mitoxantrone inmen with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: results <strong>of</strong> theCancer <strong>and</strong> Leukemia Group B 9182 <strong>study</strong>. J Clin Oncol1999;17(8):2506 –13.4. Pienta KJ, Redman B, Hussain M, Cummings G, Esper PS,Appel C, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> evaluation <strong>of</strong> <strong>oral</strong> estramustine <strong>and</strong><strong>oral</strong> etoposide in hormone-refractory adenocarcinoma <strong>of</strong>the prostate. J Clin Oncol 1994;12(10):2005–12.5. Ellerhorst JA, Tu SM, Amato RJ, Finn L, Millikan RE, PaglieroLC, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> trial <strong>of</strong> alternating <strong>weekly</strong> chemotherapyfor patients with <strong>and</strong>rogen-independent prostate cancer.J Clin Oncol 1997;3:2371– 6.6. Hudes G, Chapman A, McAleer C, Greenberg R. Taxol <strong>and</strong>estramustine in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. CancerInvest 1994;13:47– 8.7. Petrylak DP, Macarthur RB, O’Connor J, Shelton G, Judge T,Balog J, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> I trial <strong>of</strong> docetaxel with estramustine in<strong>and</strong>rogen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17(3):958 – 67.8. Crossin KL, Carney DH. Microtubule stabilization by taxolinhibits initiation <strong>of</strong> DNA synthesis by thrombin <strong>and</strong> byepidermal growth factor. Cell 1981;27:341–50.9. Stearns ME, Tew KD. Antimicrotubule effects <strong>of</strong> estramustine,an antiprostatic tumor drug. Cancer Res 1985;45:3891–7.10. Horwitz SB. Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> action <strong>of</strong> taxol. Trends PharmacolSci 1992;13:134 – 6.11. Haldar S, Chintapalli J, Croce CM. Taxol induces bcl-2 phosphorylation<strong>and</strong> death <strong>of</strong> prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res1996;56:1253–5.

Weekly Paclitaxel/Estramustine in HRPC/Ferrari et al. 204512. Dumontet C, Sikic BI. Mechanisms <strong>of</strong> action <strong>of</strong> <strong>and</strong> resistanceto antitubulin agents: microtubule dynamics, drugtransport, <strong>and</strong> cell death. J Clin Oncol 1999;17(3):1061–70.13. Wang LG, Liu XM, Kreis W, Budman DR. The effect <strong>of</strong>antimicrotubule agents on signal transduction pathways <strong>of</strong>apoptosis: a review. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1999;44:355– 61.14. Speicher LA, Barone L, Tew KD. Combined antimicrotubuleactivity <strong>of</strong> estramustine <strong>and</strong> taxol in human prostatic carcinomacell lines. Cancer Res 1992;52:4433– 40.15. Hudes GR, Nathan F, Khater C, Haas N, Cornfield M, GiantonioB, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> trial <strong>of</strong> 96-hour <strong>paclitaxel</strong> plus <strong>oral</strong>estramustine phosphate in metastatic hormone-refractoryprostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15(9):3156 – 63.16. Torres K, Horwitz SB. Mechanism <strong>of</strong> Taxol-induced celldeath are concentration dependent. Cancer Res 1998;58:3620 – 6.17. Hainsworth JD, Greco FA. Paclitaxel administered by 1-hourinfusion. Preliminary results <strong>of</strong> a <strong>Phase</strong> I/<strong>II</strong> trial comparingtwo schedules. Cancer 1994;74(4):1377– 82.18. Chang AM, Boros L, Asbury R, Hiu L, Rubins J. Dose escalation<strong>study</strong> <strong>of</strong> 1-hour <strong>weekly</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> administration inpatients with hormone refractory prostate cancer. SeminOncol 1997;5(Suppl 17):69 –71.19. Rosenberg SK, Muggia F, Russell C, Parimoo D, Israel D,Rogers M, et al. Estramustine phosphate (EMP) <strong>and</strong> 3H<strong>paclitaxel</strong>:a <strong>Phase</strong> I <strong>study</strong> in women with refractory cancer.Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1996;15:181.20. Kelly WK, Scher HI, Mazumdar M, Vlamis V, Schwartz M,Fossa SD. Prostate-specific antigen as a measure <strong>of</strong> diseaseoutcome in metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer.J Clin Oncol 1993;11:607–15.21. Smith D, Dunn RL, Strawderman MS, Pienta KJ. Change inserum prostate-specific antigen as a marker <strong>of</strong> response tocytotoxic therapy for hormone-refractory prostate cancer.J Clin Oncol 1998;16(5):1835– 43.22. Scher H, Kelly WMK, Zhang Z-F, Ouyang P, Sun M, SchwartzM, et al. Post-therapy serum prostate-specific antigen level<strong>and</strong> survival in patients with <strong>and</strong>rogen-independent prostatecancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91(3):244 –51.23. Bubley GJ, Carducci M, Dahut W, Dawson N, Daliani D,Eisenberger M, et al. Eligibility <strong>and</strong> response guidelines for<strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> clinical trials in <strong>and</strong>rogen-independent prostatecancer: recommendations from the prostate specific antigenworking group. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3461–7.24. Norton L. Implications <strong>of</strong> kinetic heterogeneity in clinicaloncology. Semin Oncol 1985;12:231–35.25. Fennelly D, Aghajanian C, Shapiro F, O’Flaherty C, McKenzieM, O’Connor C, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> I <strong>and</strong> pharmacologic <strong>study</strong><strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong> administered <strong>weekly</strong> in patients with relapsedovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 1997;15(1):187–92.26. Hainsworth JD, Urba WJ, Hon JK, Thompson KA, Stagg MP,Hopkins LG, et al. One-hour <strong>paclitaxel</strong> plus carboplatin inthe treatment <strong>of</strong> advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results<strong>of</strong> a multicenter, <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> trial. Eur J Cancer 1998;34(5):654–8.27. Reference PD. Emcyt. physicians desk reference, volume 52.1998:2267– 8.28. Hudes G. Estramustine-based chemotherapy. Semin UrolOncol 1997;15(1):13–9.29. Roth BJ, Yeap BY, Wilding G, Kasimis B, McLeod D, LoehrerPJ. Taxol in advanced, hormone-refractory carcinoma <strong>of</strong> theprostate. A <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> trial <strong>of</strong> the Eastern Cooperative OncologyGroup. Cancer 1993;72(8):2457– 60.30. Trivedi C, Redman B, Flaherty LE, Kucuk O, Du W, HeilbrunLK, et al. Weekly 1-hour infusion <strong>of</strong> <strong>paclitaxel</strong>. Clinical feasibility<strong>and</strong> efficacy in patients with hormone-refractoryprostate carcinoma. Cancer 2000;89(2):431– 6.31. Yagoda A, Smith JA Jr., Soloway MS, Tomera K, Seidmon EJ,Olsson C, et al. <strong>Phase</strong> <strong>II</strong> <strong>study</strong> <strong>of</strong> estramustine phosphate inadvanced hormone-refractory prostate cancer with increasingprostate specific antigen levels [abstract 686]. J Urol1991;145:384A.