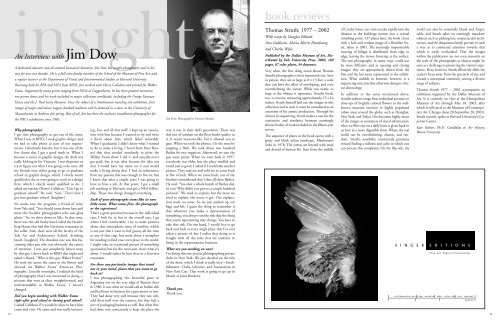

12insightJim DowAn Interview withA dedicated educator and all-around humanist/ humorist, Jim Dow has taught photography and its historyfor over two decades. He is a full-time faculty member of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts anda regular lecturer at the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University.Receiving both his BFA and MFA from RISD, Jim worked with Harry Callahan and printed for WalkerEvans. Supported by many grants ranging from NEAs to Guggenheims, he has been granted numerousone-person shows and his work included in major collections worldwide, including the George EastmanHouse and the J. Paul Getty Museum. Once the subject of a Smithsonian traveling solo exhibition, Jim’simages of major and minor leaguer baseball stadiums will be featured in a show at the University ofMassachusetts at Amherst this spring. Best of all, Jim has been the exclusive installation photographer forthe PRC’s exhibitions since 1985.Why photography?I got into photography to get out of the army.When I was at RISD, I took graphic design, andwe had to take photo as part of our requirements.I absolutely hated it, but it was one of thefew classes that I got a good mark in. When Ibecame a senior in graphic design, the draft wasreally kicking in for Vietnam. I was desperate totry to figure out what I was going to do next. Allmy friends were either going to go to graduateschool in graphic design, which I clearly wasn’tqualified to do, or were going to work in a designfirm, which I clearly wasn’t qualified to do. Iasked my teacher (Harry) Callahan, “Can I go tograduate school?” He said, “Sure.” That’s how Igot into graduate school. [laughter]Six weeks into the program, a friend of minefrom Yale said, “You should come down here andmeet this Socialist photographer who uses glassplates.” So, we drive down to Yale. At that time,there was this old funky hotel called the HeidelbergHouse that had this Germanic restaurant inthe cellar. And, there were all the faculty of theYale Art and Architecture School, drinkinglunch. [laughter] The drunkest one was this fascinatingolder guy who was obviously the centerof attention. I was just completely blown awayby this guy. I drove back to RISD that night andasked a friend, “Who is this guy Walter Evans?”He took me across the street to the library andshowed me Walker Evans’ American Photographs.Literally overnight, I realized the kindof photography that I was interested in doing—pictures that were as clear, straightforward, andunderstandable as Walker Evans’. I haven’tchanged.Did you begin working with Walker Evansright after grad school or during grad school?I asked Callahan if it would be okay to have himcome and visit. He came and was really interesting,fun, and all that stuff. I kept up an associationwith him because I wanted to try and writea thesis about him, which failed miserably.When I graduated, I didn’t know what I wantedto do to make a living. I heard from Peter Bunnelthat they needed somebody to print theWalker Evans show. I did it, and actually nevergot paid, but it was okay because the idea wasthat I would have my name on it and wouldmake a living doing that. I had an inheritancefrom my parents that was enough to live on, butI knew that after a couple years I was going tohave to have a job. At that point, I got a smalljob teaching at Harvard, and got a NEA fellowship.Those two things changed everything.Each of your photographs <strong>see</strong>ms like its ownlittle event. What comes first, the photographor the experience?That’s a great question because in the individualcase, I look for it, but in the overall case, I gowhere I feel comfortable. I try to make picturesabout that atmospheric sense of comfort, whichis not just that I want to feel groovy all the timeor any of that crap, but more about a metaphorfor needing to find your own place in the world.I might take an occasional picture of somethingspectacular, but for the most part, that’s what it’sabout. I would rather be here than in a four-starrestaurant.Are there any particular images that standout in your mind, places that you want to goback to?I was photographing this beautiful place inArgentina out on the very edge of Buenos Airesin 1986. It was what we would call an Italian deliand had been in business for a generation or two.They had done very well because they not onlysold their stuff over the counter, but they had asort of packaging business as well. But what theyhad done very consciously is keep the place theJim Dow. Photograph by Terrence Morash.way it was in their dad’s generation. There wasthis sort of sawdust on the floor funky quality toit. It wasn’t museum-like, but it allowed you togaze. When we took the photos, I lit the store bypopping a flash. We took about two hundredflashes for two negatives. Afterward, we sent theguy some prints. When we went back in 1997,everybody was older, but the place smelled andtasted just as good. I asked if I could take anotherpicture. They said yes and told me to come backat five o’clock. When we came back, one of thebrothers remembered that I shot all those flashes.He said, “You shot a whole bunch of flashes didn’tyou? Why didn’t you give us a couple hundredpictures?” We tried to explain, but the more wetried to explain, the worse it got. Our explanationmade no sense. So we just packed up ourbags and left. I guess the thing to remember isthat whenever you make a representation ofsomething, you always run the risk that the thingthat you’re representing may change. You have totake that risk. On one hand, I would love to goback and look at every single place that I’ve evertaken a picture of, but I realize that doing so isfraught with all the risks that are endemic tobeing in the representation business.What are you working on now?I’m doing this one project photographing privateclubs in New York. We just decided on the titleof the show, which I think is really nice—Establishments:Clubs, Libraries, and Associations inNew York City. That work is going to go up inMarch at Janet Borden’s.Thank you.Thank you.book reviewsThomas Struth: 1977 – 2002With essays by Douglas Eklund,Ann Goldstein, Maria Morris Hambourgand Charles Wylie.Published by the Dallas Museum of Art. Distributedby Yale University Press, 2002, 189pages, 67 color plates, 34 duotones.Very often, the first thing noted about ThomasStruth’s photographs is their mammoth size. Seenin person, they are as large as 8 x 13 feet, a scalethat can have the effect of enveloping, and evenoverwhelming the viewer. While not nearly solarge as the objects it represents, Struth’s book,too, is oversize, measuring approximately 15 x 16inches. Struth himself laid out the images in thiscollection and as such it must be considered as anextension of his artistic production. Through hischoices in sequencing, Struth makes a case for thecontinuity and similarity between <strong>see</strong>minglydiverse bodies of work included in the fifteen-yearsurvey.The sequence of plates in the book opens with agritty and bleak urban landscape, Manhattan’sSoho in 1978. The streets are littered with trashand devoid of human life. Seen from the middle© R.of Crosby Street, our view recedes rapidly into thedistance as the buildings narrow into a centralvanishing point. 137 plates later, the book closeswith a lush and verdant image of a Brazilian forest,taken in 2001. The <strong>see</strong>mingly impenetrableweaving of foliage is distributed from edge toedge, leaving the viewer hovering at the surface.The two photographs, in many ways, could notbe more different, and as opening and closingimages, they are appropriately drawn from thefirst and the last series represented in the exhibition.What unfolds in between, however, is asequencing structure that otherwise disrupts a linearchronology.In addition to the series mentioned above,Struth’s subjects range from individual portraits toclose-ups of brightly colored flowers to the wellknownmuseum interiors to highly populatedurban areas around the globe, such as Shanghai,New York, and Tokyo. One becomes highly awareof the images as containers of visual information;what we filter out on a daily basis is given back tous here in a more digestible form. Where the realworld can be overwhelming, chaotic, and random,Struth’s sensibility consistently gravitatestoward finding a stillness and calm in which onecan process this complexity. On the flip side, theworld can also be essentially bland and forgettable,and Struth takes on <strong>see</strong>mingly mundanesubjects such as parking lots, unspectacular architecture,and the ubiquitous family portrait in sucha way as to command attention towards thatwhich is easily overlooked. That the imageswithin the publication are not even remotely onthe scale of the photographs as objects might be<strong>see</strong>n as a challenge to preserving the viewer’s experience.Here, however, Struth effectively shifts thereader’s focus away from the spectacle of size andtoward a conceptual continuity among a diverserange of subjects.Thomas Struth 1977 – 2002 accompanies anexhibition organized by the Dallas Museum ofArt. It is currently on view at the MetropolitanMuseum of Art through May 18, 2003, afterwhich it will travel to the Museum of ContemporaryArt, Chicago (June 28-September 28, 2003).Struth recently spoke at Harvard University’s CarpenterCenter.Kate Palmer, Ph.D. Candidate in Art History,<strong>Boston</strong> UniversityS I N G E R E D I T I O N SFine Art Digital Printmakingcollaborative printing archival inks color and b & w naturalpapers13

photography events in new england and beyondEXHIBITIONSMASSACHUSETTSArt Complex Museum at DuxburyDuxbury Art Association Annual Winter Juried Show(April 5-27). Wed-Sun, 1-4. 189 Alden St., Duxbury,MA 02331. 781-934-6634. www.artcomplex.orgArt Institute of <strong>Boston</strong>Photographs by Miguel Rio Branco (thru March 3);Senior Graduate Exhibition (April 28-May 31). Mon-Fri, 9-6; Sat, 9-5; Sun, 12-5. 700 Beacon St, <strong>Boston</strong>,MA 02215. 617-585-6600. www.aiboston.eduArt InteractiveBody Double (thru April 6). Sat & Sun, 10-6.130 Bishop Allen Dr., Cambridge, MA 02139.617-498-0100. www.artinteractive.orgartSPACE @ 16Malden Art Now 2003 (thru March 15). March 15,12-5; Mon-Fri evenings, by appt. 16 Princeton Road,Malden, MA 02148. 781-322-6851.<strong>Boston</strong> Architectural Center - McCormick GalleryIn Celebration of Mentorship: An Exhibition of <strong>Boston</strong>areaFirms Employing BAC Students (March 5-April 6)and Rose Theater Project USA (April 24-June 1).Mon-Thur, 9-9; Fri-Sat, 9-5; Sun, 12-5. 320 NewburyStreet, <strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02115. 617-262-5000. www.thebac.edu/exhibits/<strong>Boston</strong> Arts AcademyPenumbra (thru March 21). 174 Ipswich St, <strong>Boston</strong>,MA 02215. 617-635-6470. artsacad.boston.k12.ma.us/<strong>Boston</strong> CollegeAn Ancient Light in the Burns Library (thru March 17);Éire/Land in McMullen Museum of Art (thru May19). Library hours: Mon-Fri, 9-5. 617-552-3282.Museum hours: Mon-Fri, 11-4 ; Sat-Sun, 12-5.617-552-8100. 140 Commonwealth Ave, ChestnutHill, MA 02467. www.bc.edu/arts<strong>Boston</strong> University Art GalleryMFA Graphic Design Exhibition (April 11-May 4).Tue-Fri, 10-5; Sat-Sun, 1-5. College of Fine Arts,855 Commonwealth Ave, <strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02215.617-353-3329. www.bu.edu/artDavis Museum and Cultural CenterFazal Sheikh: A Camel for the Son, Ramadan Moon, TheVictor Weeps (thru June 8); The Space Between: ArtistsEngaging Race and Syncretism and Bridging the Border:Shared Themes in Mexican and American Art 1900-1950(March 18-June 8). Tue-Sat, 11-5; Sun, 1-5. WellesleyCollege, 106 Central St, Wellesley, MA 02481.781-283-2051. www.wellesley.edu/DavisMuseum/DeCordova Museum and Sculpture ParkStreet Portraits, 1947-1976: The Photographs of JulesAarons (March 8-May 25). Tue-Sun, 11-5. 51 SandyPond Rd., Lincoln, MA 01773. 781-259-8355.www.decordova.orgElias Fine ArtImpressions of a Revolution: New Prints (March 6-April26). Wed-Sat, 12-5. 120 Brain St., Rear, Allston.617-783-1888.Essex Art CenterWomen’s History Month with Lynn VanNatta, JudiMilano, and Adrienne Araujo; The Collaborative Visionsby students from Collaborative Alternative School (March7-April 25). Tue-Thu, 10-7; Fri, 10-3. 56 Island St.,Lawrence, MA 01840. 978-685-2343.www.essexartcenter.comFirehouse Center for the ArtsAfrican Portraits, Cuban Textures (March 5-31). Tue-Sun, 10-5. One Market Square, Newburyport, MA01950. 978-462-7336. www.firehousecenter.comFitchburg Art MuseumScotland Calls: One Hundred Years of Scottish <strong>Photography</strong>(April 13-June 8). Tue-Sun, 12-4. 185 Elm St.,Fitchburg, MA 01420. 978-345-4207.www.fitchburgartmuseum.orgFletcher/Priest GalleryDonna DiRado: Carnival (thru March 27). Wed-Thur,12-6, and by appt. 5 Pratt Street, Worcester, MA01609. 508-791-5929. www.fletcherpriestgallery.comFort Point Arts Community GalleryBetween Evolution and Abberation: Works of ImaginaryAnatomy (thru March 7); Hidden Language with pinholephotographs by Jesseca Ferguson (March 14-April18). Mon-Fri, 10-3; Sat, 12-5. 300 Summer St.,<strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02110. 617-423-4299.www.fortpointarts.orgGriffin Museum of <strong>Photography</strong>The New Year’s Eve Project: 20 Years Around the Worldby Jill Waterman (thru March 30). Tue-Sun, 12-4. 67Shore Road, Winchester, MA 01890. 781-729-1158.www.griffinmuseum.org.Judy Ann Goldman Fine ArtDavid Armstrong (thru March 1). Tue-Sat, 10:30-5:30.14 Newbury St., <strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02116. 617-424-8468.Lee Gallery19th and 20th Century Photographs (ongoing).Mon-Fri, 10-5:30. 9 Mount Vernon Street, 2nd Floor,Winchester, MA 01890. 781-729-7445.www.leegallery.comMassachusetts Museum of Contemporary ArtUncommon Denominator: New Art from Vienna(thru Spring 2003). Mon-Sun, 11-5; closed Tuesdays.87 Marshall Street, North Adams, MA 01247.413-664-4481. www.massmoca.orgMead Art Museum at Amherst CollegeCritical Mass: Happening, Fluxus, Performance, andIntermedia at Rutgers University 1958-1971 (thru June1) and American Edge: Photographs by Steve Schapiro(thru March 23). Tue-Sun, 10-4:30; Thur, 10-9.Intersection of Rte. 9 and South Pleasant St., Amherst,MA. 413-542-2335. www.amherst.edu/meadMIT List Visual Art CenterPaul Pfeiffer (thru April 6). Tue-Sun, 12-6; Fri, 12-8.20 Ames Street Building E15, Atrium Level, Cambridge,MA 02139. 617-253-4680. web.mit.edu/lvacMIT Museum Main GalleryThe Winning Hand: Images from the MIT RadiationLaboratory Negative Collection (thru May 4); Flashes ofInspiration: The Work of Harold Edgerton; Holography:The Light Fantastic (ongoing). Tue-Fri, 10-5; Sat-Sun,12-5. 265 Massachusetts Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139.617-253-4444. web.mit.edu/museumMuseum of Fine Arts, <strong>Boston</strong>Traveling Scholars 2002, A juried exhibition of MuseumSchool students and alumni. Mon-Tue, 10-4:45;Wed–Fri, 10-9:45; Sat-Sun, 10-5:45. 465 HuntingtonAve., <strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02115. 617-267-9300.www.mfa.orgNew England School of <strong>Photography</strong> Gallery OneKeith Johnson Photographs (Feb 10-March 14); To theWest: Dreams by Ronald Cowie (March 17- April 18);Landscapes of My Mind by Janet Koenig Picinich (April21-May 23). Mon-Fri, 9-5. 537 Commonwealth Ave.,<strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02215. 617-437-1868. www.nesop.comPanopticon GalleryPhotographs by Charles Gauthier (thru March 29).Mon-Fri, 10-6; Sat, 11-5. 435 Moody St., Waltham,MA 02453. 781-647-0100. www.panopt.comPeabody Museum of Archeology and EthnologyCharles Fletcher Lummis: Southwestern Portraits 1888-1896 (thru August 2003). Mon-Sun, 9-5. 11 DivinityAve., Cambridge, MA 02138. 617-496-0099.www.peabody.harvard.eduRobert Klein GalleryFace to Face: Portraits by Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans,Horst P. Horst, Yousuf Karsh, Irving Penn, AugustSander, Herman Leonard, Ansel Adams, Lewis Hine,Edward Sheriff Curtis and Lotte Jacobi (thru March14); Bruce Davidson Photographs (March/April). Tue-Fri, 10-5:30; Sat, 11-5. 38 Newbury St., <strong>Boston</strong>, MA02116. 617-267-7997. www.robertkleingallery.comin the loupe listings deadlinesMay/June issue:March 15, 2003July/August issue:May 18, 2003Somerville TheatreLost Theatres of Somerville (thru March 2003). Thur, 2-7; Fri, 2-5; Sat, 12-5. One Westwood Rd, Somerville,MA 02143. 617-666-9810. www.losttheatres.orgSouth Shore Art CenterTech Art: A Computer Art Exhibition Juried by AaronFry and Dorothy Krause (April 18-May 25). Mon-Sat,10-4; Sun 12-4. 119 Ripley Rd, Cohasset MA 02025.781-383-2787.The Gallery at Barrington Center for the ArtsBoth Sides of the Cut: Six Cape Ann Photographers(thru March 21). Mon-Fri, 9-4; Sat, 12-4. GordonCollege, 255 Grapevine Rd, Wenham, MA 01984.978-867-4414.Tisch Gallery of Tuft UniversityPrequel from the students of the Master of Fine Artsprogram (April 3-20). Wed-Sat, 12-8; Sun, 12-5.Aidekman Arts Center, 40 Talbot Avenue, Medford,MA 02155. 617-627-3518. www.tufts.edu/as/galleryTrustman Art Gallery at Simmons CollegeArt from Abafazi: A Tenth Anniversry Retrospective (thruMarch 7). Mon-Fri, 10-4; closed Feb 17. SimmonsCollege, 4th Floor, Main College Building, 300 TheFenway, <strong>Boston</strong>, MA 02115. 617-521-2268.www.simmons.edu/trustmanUniversity Gallery at University of MassachusettsJim Dow: American and National League Baseball Stadiums(March 25-May 16). Tue-Fri, 11-4:30; Sat- Sun,2-5. Fine Arts Center, University of Massachusetts,151 Presidents Drive, Amherst, MA 01003.413-545-3670. www.umass.edu/fac/universitygalleryWilliams College Museum of ArtFrom the Collection: New York, New York (thru March23); American Dreams: American Art to 1950 (thruMarch 30); Wait Until Dark: Night <strong>Photography</strong> fromthe Collection of Jay Richard DiBiaso (thru July 6).Tue- Sat, 10-5, Sun, 1-5. 15 Lawrence Hall Dr,Suite 2, Williamstown, MA 02116. 413-597-2429.www.williams.edu/WCMAWorcester Art MuseumWall at WAM: Julian Opie (ongoing). Wed-Sun, 11-5;Thur, 11-8; Sat, 10-5. 55 Salisbury St., Worcester, MA01609. 508-799-4406. www.worcesterart.orgELSEWHERE IN NEW ENGLANDCurrier Museum of ArtAn Eye for Exploration: Photographs from the JonathanStein Collection (thru March 24). Mon,We, Fri, Sun11-5; Thu 11-8; Sat 10-5. 201 Myrtle Way, Machester,NH 03104. 603-669-6144. www.currier.orgBowdoin College Museum of ArtThe Writing on the Wall: Photographs by Shimon Attie(thru March 23). Tue-Sat, 10-5; Sun, 2-5. 9400 CollegeStation, Brunswick, ME 04011. 207-725-3275.academic.bowdoin.edu/artmuseum/David Winton Bell Gallery at Brown UniversityBathhouses by Katarzyna Kozyra (thru March 9). Mon-Fri, 11-4; Sat-Sun, 1-4. List Art Center, Brown University,64 College Street, Providence, RI 02912. 401-863-2932. www.brown.edu/Facilities/David_Winton_Bell_GalleryFarnsworth Art MuseumAll of Pierce: From <strong>Boston</strong> to Baghdad (thru March 16).Tue-Sat, 10-5; Sun, 1-5. 365 Main St., Rockland, ME04843. 207-596-6457. www.farnsworthmuseum.orgHartford Center for Contemporary CultureMain Gallery. Call for hours. 56 Arbor St., Hartford,CT 06106. 860-232-1006. www.realartways.orgHood Museum of Art at Dartmouth CollegeAmbassadors of Progress, American Women Photographersin Paris 1900-1901; and Carrie Mae Weems “TheHampton Project” (thru March 9). Tue–Sat, 10-5; Wed,10-9; Sun, 12-5. Dartmouth College, Wheelock St.,Hanover, NH 03755. 603-646-1400. www.dartmouth.edu/~hoodJaffe-Friede and Strauss Galleriesat Dartmouth CollegeStudio Art Department Faculty Exhibition(thru March 6). Tue-Sat; 12:30-10; Sun, 12:30-5:30.Hopkins Center for the Arts, Dartmouth College,Hanover, NH 03755. 603-646-3651.www.hop.dartmouth.eduKeith de Lellis GalleryNew York Night & Day: Vintage Photographs by PaulWoolf, ca. 1932-39 (thru April 4). Tue-Sat, 11-5.47 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021.212-327-1482.Portland Museum of ArtMigrations: Humanity in Transition, photographs bySebastião Salgado (thru March 23). Tue, Wed, Sat, andSun, 10-5; Thur and Fri, 10-9. Congress Square,Portland, ME 04101. 207-775-6148.www.portlandmuseum.orgReal Art Ways Center for Contemporary CultureLean To in the Main Gallery (March 8-April 27). Tue-Sun, 2-10; Fri-Sat, 2-midnight. 56 Arbor St, Hartford,CT 06106. 860-232-1006. www.realartways.orgRobert Hull Fleming MuseumAndy Warhol Work and Play (thru June 9). Tue-Fri, 9-4;Sat-Sun, 1-5. University of Vermont, 61 ColchesterAve., Burlington, VT 05405. 802-656-0750.www.flemingmuseum.orgSalt Institute for Documentary StudiesPursglove: Legacies of Our Livelihood (March 7-May 9).Mon-Fri, 11:30-4:30. 110 Exchange St., Portland, ME04112. 207-761-0660. www.salt.eduStevens Gallery at University of ConnecticutAncestor Portraits by Donna Hamil Talman (thru March14). Mon-Thur, 8am-midnight; Fri, 8am-10pm; Sat,10am-10pm; Sun, 10am-midnight. University of Connecticut,Homer Babbidge Library, U-1005A, Storrs,CT 06269. 860-486-6020.www.lib.uconn.edu/exhibits/.University of Maine Museum of ArtSebastião Salgado: Migrations~Humanity in Transition(thru March 15). Tue-Sat, 9-6pm; Sun, 11-5.Norumbega Hall, 40 Harlow St., Bangor, ME 04401.207-561-3350.University of New Hampshire Art GalleryReligion: Contemporary Interpretations by Women (thruApril 25). Mon-Wed, 10-4; Thur, 10-8; Sat-Sun, 1-5.Paul Creative Arts Center, University of New Hampshire,Durham, NH 03824. 603-862-3712.www.unh.edu/art-gallery.htmlUniversity of Rhode Island <strong>Photography</strong> GalleryPatrick Burns: Panoramic Landscapes (thru March 9);Night Views and Other Dark Encounters: Jill Berry(March 25-May6). Tue-Fri, 12-4; Sat-Sun, 1-4.Fine Arts Center Galleries, 105 Upper College Road,Kingston, RI 02881. 401-874-2775.www.uri.edu/artgalleriesWadsworth Atheneum Museum of ArtStructures of Difference (thru July 6). Tue-Fri, 11-5;Sat-Sun, 10-5. 600 Main St, Hartford, CT 06103.860-278-2670. www.wadsworthatheneum.orgYale University Art GalleryThe Once and Future Art Gallery: Renewing Yale’s OldestMuseum (thru May 18). Tue-Sat, 10-5; Thur, 10-8;Sun, 1-6. 1111 Chapel Street, New Haven, CT 06520.203-432-0600. www.yale.edu/artgallery/Zilkha Gallery at Wesleyan UniversityGood Morning, America (thru March 2). Tue-Sun, 12-4. Center for the Arts, Wesleyan University, Middletown,CT 06459. 860-685-2684.www.wesleyan.edu/CFAEDUCATIONThe Art Institute of <strong>Boston</strong> at Lesley University,through the Office of Continuing and ProfessionalEducation is offering Winter/Spring 2003 workshopsin Digital Media, <strong>Photography</strong>, Marketing, and Framing/Matting.Upcoming courses are Introduction toBlack & White <strong>Photography</strong>, with Ruth MolinaWalker, Writing for Photojournalists: The WritingPhotographer, with John Suiter, and Marketing forPhotographers, with Jeffrey Brown, among many others.Inquiries may be directed to Diana Arcadipone,617-585-6729. www.aiboston.edu/EXTRAThe Art Institute of <strong>Boston</strong> and The French-AmericanCollaborative in Language and Art will host its7tth and 8th workshops "<strong>Photography</strong> as an Art" inthe early spring in the Caribbean, and in Paris in thesummer of 2003. These unique week-long intensiveworkshops will cover the technology of film and cameras,correlations with the artistry of photographiccomposition, along with readings from the literature ofart and photography. These workshops are designed forbeginner and intermediate students and college creditis available. Costs range from $995-$1295 per personexcluding airfare. Please check out the website atwww.facilart.net for details or call Regis de Silva at 617482 8055.The <strong>Boston</strong> Photo Collaborative offers innovativephotography classes for beginner, intermediate, andadvanced levels, amateurs and professionals in blackand white, color, digital and alternative processes. Inaddition to these high quality classes, the Collaborativeruns several community-based youth and senior programs.Darkroom rental is also available. For moreinformation please visit www.bostonphoto.org or call617-524-7729. 67 Brookside Ave., Jamaica Plain, MA02130.The Cape Cod Photo Workshops offers a wide varietyof courses on photography. For more informationplease contact Cape Cod Photo Workshops at 508-255-6808. P.O. Box 1619, N. Eastham, MA 02651.The Essex Art Center offers classes in all artisticmedia, including photography. For more informationgo to www.essexartcenter.com or call 978-685-2343.56 Island Street, Lawrence, MA 01840The International Center for <strong>Photography</strong>announces its Travel Abroad Program for 2003.Among many programs, they will offerSummersite:Venetian Light, taught by Hollo Smith-Pedlosky with visiting photographer Neal Rantoul,May 29-June 10, 2003. For more information visitwww.icp.org or call 212-857-0001. 1114 Avenue ofthe Americas at 43rd Street, New York, NY 10036.Horizons to Go Travel Programs offers classes in allartistic media, including photography. For more informationand prices please contact Horizons to Go! POBox 2206, Amherst, MA 01004, or go to www.horizons-art.comor call 413- 549-2900.Georgia Litwack will conduct an eight-week courseDaguerre to Digital: the History of <strong>Photography</strong>,beginning April 2, 3003. For more information contactLaurie Swett, Newton Community Center, 360Lowell Ave., Newton, MA 02460 or call 617-552-7118.The Maine Photographic Workshops will be offeringa large variety of <strong>Photography</strong> workshops. The MainePhotographic Workshops are located at 2 CentralStreet, PO Box 200, Rockport, ME 04856. For moreinformation go to www.theworkshops.com or call 1-877-577-7700.Ralph Mercer and Daniel McManus announce their2003 Death Valley Workshop. This is their 4thannual photographic expedition to Death Valley. Learnthe artistic and practical techniques of photography inthe field while you explore the transcendental environmentof America’s newest National Park. For moreinformation email ralph@ralphmercer.com or call 617-542-2211.Santa Fe <strong>Photography</strong> and Digital Workshops arehosting a wide variety of workshops and programs thisWinter. For more information contact Santa Fe Workshops,PO Box 9916, Santa Fe, NM 87504-5916, orgo to www.santafeworkshops.com or call 505-983-1400.The School of the Museum of Fine Arts announcesits Summer 2003 International Art Programs inVenice, Paris, and Vienna. Art making abroad for alllevels. For more information go to smfa.edu or call617-267-1219.John Sexton Photo Workshops offers a wide varietyof courses on photography. For more informationplease contact us on the web at www.johnsexton.com.John Sexton <strong>Photography</strong> Workshops, 291 LosAgrinemsors, Carmel Valley, CA, 93924.Snow Farm, The New England Craft Program offersclasses in all artistic media, including photography. Formore information please contact Snow Farm at 5Clary Road, Williamsburg, MA 01096, go towww.snowfarm-art.org, or call at 413-268-3101.South Shore Art Center offers classes in all artisticmedia, including photography. The South Shore ArtCenter is located at 119 Ripley Rd., Cohasset, MA02025. For more information go to www.ssac.org orcall 781-383-2964.ENTRIES/OPPRTUNITIESAbout the Arts invites artists working in all media tosubmit work for a new television series airing in 2003.About the Arts was created in 1995 to provide exposureand visibility to the arts and bring local artists tothe forefront. It has produced more than 250 visual,performing, literary, and media artists, museums, andgallery events.The series aims to produce 12 half hour documentarieson artists who bring awareness to issues such as racism,AIDS, poverty, and homelessness.For more information visit www.aboutthearts.com,email jamesbrown@aboutthearts.com, or call 617-644-0143.The Flat Street Center for <strong>Photography</strong> is acceptingportfolios for exhibition dates in 2003. Send 20 slidesmin. of final prints for exhibition. The gallery willcharge a 30 % commission on work that is sold.Details on other artists and gallery responsibilities canbe obtained by writing or calling the gallery located at49 Flat Street, Brattleboro, VT 05301. www.flatstreetphoto.orgThe 2003 Photo Review <strong>Photography</strong> Exhibitionplaces a Call for Entries for its 19th annual exhibitionat the photography gallery of the University of Arts,Philadelpia, PA AND accepted entries will be reproducedin its Summer 2003 issue. All entries must bereceived between May 1 and May 15, 2003. For moreinformation and a prospectus send a SASE to PhotoReview, 140 East Richardson Ave., Suite 301, Langhorne,PA 19047 or go to www.photoreview.org.Slow Art Productions announces its 10th annualShowcase 2003 exhibition, with a focus on recentwork. The exhibition will be held in the LimnerGallery, 870 Avenue of the Americas, New York.Opento all media. Deadline for submission April 30, 2003.Send a SASE for prospectus to Slow Art Productions,Showcase 2003, 870 Avenue of the Americas, NewYork, NY, 10001 or email slowart@aol.com.The Stebbins Gallery in Harvard Square, CambridgeMA is placing a Cell for Entries for its 2003 Spring<strong>Photography</strong> Exhibition, April 5-27. It will be juriedfrom actual work by Don Gurewitz. Drop-off date isSaturday March 29, 11-5pm. For more informationcall 617-576-0131. The Stebbins Gallery is located atthe First Parish Church/ Unitarian, Zero ChurchStreet, Cambridge, MA 02138.1415