The Galerie du Temps at the Louvre-Lens A unique presentation of ...

The Galerie du Temps at the Louvre-Lens A unique presentation of ...

The Galerie du Temps at the Louvre-Lens A unique presentation of ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>The</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> Enlightenment<br />

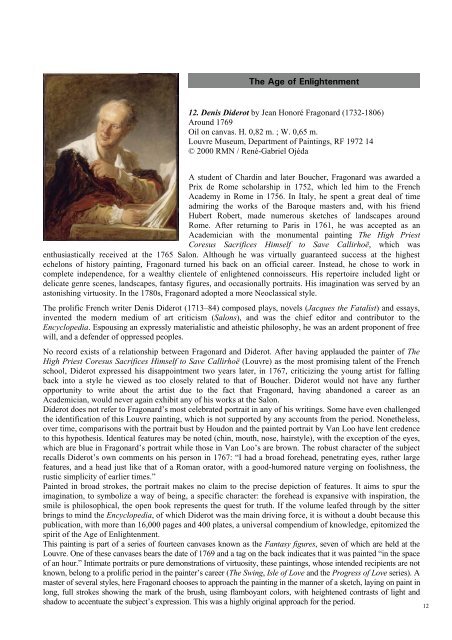

12. Denis Diderot by Jean Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806)<br />

Around 1769<br />

Oil on canvas. H. 0,82 m. ; W. 0,65 m.<br />

<strong>Louvre</strong> Museum, Department <strong>of</strong> Paintings, RF 1972 14<br />

© 2000 RMN / René-Gabriel Ojéda<br />

A student <strong>of</strong> Chardin and l<strong>at</strong>er Boucher, Fragonard was awarded a<br />

Prix de Rome scholarship in 1752, which led him to <strong>the</strong> French<br />

Academy in Rome in 1756. In Italy, he spent a gre<strong>at</strong> deal <strong>of</strong> time<br />

admiring <strong>the</strong> works <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Baroque masters and, with his friend<br />

Hubert Robert, made numerous sketches <strong>of</strong> landscapes around<br />

Rome. After returning to Paris in 1761, he was accepted as an<br />

Academician with <strong>the</strong> monumental painting <strong>The</strong> High Priest<br />

Coresus Sacrifices Himself to Save Callirhoë, which was<br />

enthusiastically received <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> 1765 Salon. Although he was virtually guaranteed success <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> highest<br />

echelons <strong>of</strong> history painting, Fragonard turned his back on an <strong>of</strong>ficial career. Instead, he chose to work in<br />

complete independence, for a wealthy clientele <strong>of</strong> enlightened connoisseurs. His repertoire included light or<br />

delic<strong>at</strong>e genre scenes, landscapes, fantasy figures, and occasionally portraits. His imagin<strong>at</strong>ion was served by an<br />

astonishing virtuosity. In <strong>the</strong> 1780s, Fragonard adopted a more Neoclassical style.<br />

<strong>The</strong> prolific French writer Denis Diderot (1713–84) composed plays, novels (Jacques <strong>the</strong> F<strong>at</strong>alist) and essays,<br />

invented <strong>the</strong> modern medium <strong>of</strong> art criticism (Salons), and was <strong>the</strong> chief editor and contributor to <strong>the</strong><br />

Encyclopedia. Espousing an expressly m<strong>at</strong>erialistic and <strong>at</strong>heistic philosophy, he was an ardent proponent <strong>of</strong> free<br />

will, and a defender <strong>of</strong> oppressed peoples.<br />

No record exists <strong>of</strong> a rel<strong>at</strong>ionship between Fragonard and Diderot. After having applauded <strong>the</strong> painter <strong>of</strong> <strong>The</strong><br />

High Priest Coresus Sacrifices Himself to Save Callirhoë (<strong>Louvre</strong>) as <strong>the</strong> most promising talent <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> French<br />

school, Diderot expressed his disappointment two years l<strong>at</strong>er, in 1767, criticizing <strong>the</strong> young artist for falling<br />

back into a style he viewed as too closely rel<strong>at</strong>ed to th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> Boucher. Diderot would not have any fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

opportunity to write about <strong>the</strong> artist <strong>du</strong>e to <strong>the</strong> fact th<strong>at</strong> Fragonard, having abandoned a career as an<br />

Academician, would never again exhibit any <strong>of</strong> his works <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong> Salon.<br />

Diderot does not refer to Fragonard’s most celebr<strong>at</strong>ed portrait in any <strong>of</strong> his writings. Some have even challenged<br />

<strong>the</strong> identific<strong>at</strong>ion <strong>of</strong> this <strong>Louvre</strong> painting, which is not supported by any accounts from <strong>the</strong> period. None<strong>the</strong>less,<br />

over time, comparisons with <strong>the</strong> portrait bust by Houdon and <strong>the</strong> painted portrait by Van Loo have lent credence<br />

to this hypo<strong>the</strong>sis. Identical fe<strong>at</strong>ures may be noted (chin, mouth, nose, hairstyle), with <strong>the</strong> exception <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> eyes,<br />

which are blue in Fragonard’s portrait while those in Van Loo’s are brown. <strong>The</strong> robust character <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> subject<br />

recalls Diderot’s own comments on his person in 1767: “I had a broad forehead, penetr<strong>at</strong>ing eyes, r<strong>at</strong>her large<br />

fe<strong>at</strong>ures, and a head just like th<strong>at</strong> <strong>of</strong> a Roman or<strong>at</strong>or, with a good-humored n<strong>at</strong>ure verging on foolishness, <strong>the</strong><br />

rustic simplicity <strong>of</strong> earlier times.”<br />

Painted in broad strokes, <strong>the</strong> portrait makes no claim to <strong>the</strong> precise depiction <strong>of</strong> fe<strong>at</strong>ures. It aims to spur <strong>the</strong><br />

imagin<strong>at</strong>ion, to symbolize a way <strong>of</strong> being, a specific character: <strong>the</strong> forehead is expansive with inspir<strong>at</strong>ion, <strong>the</strong><br />

smile is philosophical, <strong>the</strong> open book represents <strong>the</strong> quest for truth. If <strong>the</strong> volume leafed through by <strong>the</strong> sitter<br />

brings to mind <strong>the</strong> Encyclopedia, <strong>of</strong> which Diderot was <strong>the</strong> main driving force, it is without a doubt because this<br />

public<strong>at</strong>ion, with more than 16,000 pages and 400 pl<strong>at</strong>es, a universal compendium <strong>of</strong> knowledge, epitomized <strong>the</strong><br />

spirit <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> Age <strong>of</strong> Enlightenment.<br />

This painting is part <strong>of</strong> a series <strong>of</strong> fourteen canvases known as <strong>the</strong> Fantasy figures, seven <strong>of</strong> which are held <strong>at</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Louvre</strong>. One <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong>se canvases bears <strong>the</strong> d<strong>at</strong>e <strong>of</strong> 1769 and a tag on <strong>the</strong> back indic<strong>at</strong>es th<strong>at</strong> it was painted “in <strong>the</strong> space<br />

<strong>of</strong> an hour.” Intim<strong>at</strong>e portraits or pure demonstr<strong>at</strong>ions <strong>of</strong> virtuosity, <strong>the</strong>se paintings, whose intended recipients are not<br />

known, belong to a prolific period in <strong>the</strong> painter’s career (<strong>The</strong> Swing, Isle <strong>of</strong> Love and <strong>the</strong> Progress <strong>of</strong> Love series). A<br />

master <strong>of</strong> several styles, here Fragonard chooses to approach <strong>the</strong> painting in <strong>the</strong> manner <strong>of</strong> a sketch, laying on paint in<br />

long, full strokes showing <strong>the</strong> mark <strong>of</strong> <strong>the</strong> brush, using flamboyant colors, with heightened contrasts <strong>of</strong> light and<br />

shadow to accentu<strong>at</strong>e <strong>the</strong> subject’s expression. This was a highly original approach for <strong>the</strong> period.<br />

12