Pipeline 50 Years - WFP Remote Access Secure Services

Pipeline 50 Years - WFP Remote Access Secure Services

Pipeline 50 Years - WFP Remote Access Secure Services

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

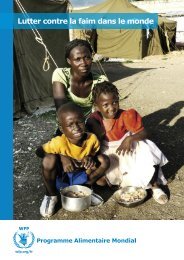

<strong>WFP</strong>/F. Botts<strong>WFP</strong>/G. DiMajo<strong>WFP</strong>/Mattew CherryHsinhua News Agency1973 Faso1973 1974 1975 Burkina Pakistan EgyptTibetFrom theArchives:Our FirstWoman inthe FieldThe prevailing wisdomover <strong>WFP</strong>’s first decadewas that life in the fieldwas too rough andrigorous for a woman.Then came Louise Sobon-Latiolais, who had workedthree years with the U.S. Peace Corps in Africa beforegetting hired in 1972 as <strong>WFP</strong>’s first woman in the field– as assistant project officer in Swaziland. By 1978,there were six women officers serving in the field outof a total 120 posts. Louise, who has since passedaway, was interviewed in 1975 for the <strong>WFP</strong> internalnewsletter:How is it that you’re the only woman projectofficer at <strong>WFP</strong>?I really wish I knew. I think women are a bit reluctantto get into this type of work because, well, once we dowe’re not encouraged to continue. They put us in ourlittle corner, and there we stay.What can a female project officer do as well if notbetter than a man – and what not?I think administratively we can do the job as well as aman, but obviously jobs we couldn’t do as well wouldbe physical labour, unloading trucks, etc. What we can,I think, do better is in our dealings in developingcountries. You find most of their nurses, teachers,dieticians and so on are female. And since males inthese countries are held in esteem, I think womenwould tell a man what she thinks he wants to hear, asopposed to her real problems. I think she would bemore inclined to give me the real picture.Has your work caused any problems with yourhusband and baby daughter?No. I think I’m in a very enviable position. I have avery flexible family. Before I got married, my husbandand I talked over the whole situation. My husband is amathematics teacher and, fortunately, very much indemand in any country to which I am likely to go.What advice would you give to other women tohelp them along this trail that you have blazed?I’m still blazing the trail and don’t think I’m in aposition to give advice. I’d tell women to just go outand try it, whatever it is, whatever field they’re in –not to be influenced by the old wives’ tales that youshould not do this and that because you’re a woman.years far stronger than when it entered. From a smallagency with total expenditures of $60 million at thebeginning of the 1970s, it had matured into one of thelargest programmes in the UN family, and a principalsource of help for the poorest of the poor in the hungrydeveloping world.IndependenceThroughout the 1980s, Africa was hammered by a seriesof food crises that dwarfed those that had struck thecontinent in the 1970s. As always, drought south of theSahara was largely responsible. But severe social, politicaland economic difficulties also played their role,compounding the problems.By 1984, hunger gripped 27 countries from coastal WestAfrica across to the Horn and down to southern Africa.More than 30 million people required help. Of those inneed, 10 million had simply abandoned their homes andlands to wander in search of food, water and pasture fortheir livestock.“It was a major challenge,” recalls Bronek Szynalski.“There were so many countries in trouble, all at the sametime, and <strong>WFP</strong> was called upon to coordinate all the reliefefforts and handle all the logistics for the entireoperation.”Building a ReputationThe worldwide food crisis burnished <strong>WFP</strong>’s credentials inanother critical area. The agency’s response to theemergency firmly established the reputation that it enjoysto this day as a globe-spanning logistical organizationwith few peers, capable of moving large amounts of foodand commodities throughout the developing world, oftenin the most difficult circumstances.The acid test came in Africa’s western Sahel region, whensix successive years of drought struck seven countriesthat were home to a combined 25 million people. In1973, an international emergency relief operation wasmounted; it lasted three years. More than 2.5 million tonsof cereals were delivered to the area. Even so, 100,000people – and one million head of cattle – perished.<strong>WFP</strong> assumed the task of coordinating the transport of allthose tons of food and other relief supplies by any meanspossible – road, rail, river, air, even camel caravans. Atthe peak of the operation, as many as 1,000 trucks a daywere operating. To reach remote locations, <strong>WFP</strong>coordinated the first-ever multinational food airlift,drawing more than 30 cargo aircraft from 12 national airforces. Over four months, flying round-the-clockrotations, the airlift delivered 25,000 tons of cereals andother food commodities. Nine West African ports, mostnot equipped to handle large volumes of food, were eitherrehabilitated or upgraded to serve an inland deliverysystem that <strong>WFP</strong> helped design and implement. Theaverage clearance at the ports more than doubled duringthe three years of the relief effort.As in the Sahel, drought descended upon Ethiopia in 1973,the result of successive years of scant rainfall. Faced withmounting problems in transporting food around Ethiopia,<strong>WFP</strong> responded by assembling its own fleet of trucks.<strong>WFP</strong> continued to build on its logistical strengthsthroughout the 1970s until, as the new decade dawned,it culminated with <strong>WFP</strong>’s taking the reins for the first timeof a multinational inter-agency relief operation. In 1980,<strong>WFP</strong> led the effort to assist 370,000 Cambodians who hadfled across the border into Thailand to escape genocideand conflict in their homeland.The Cambodian operation was also noteworthy in that itsaw <strong>WFP</strong> pioneer a new policy by distributing weekly foodrations directly to women. This policy of putting food (andincome) in the hands of women was to be increasinglyapplied through the subsequent decades, as research –and solid field experience – showed it resulted in betterfamily health, education, and child nutrition. But applyingthe principle had to be done gently, with tact.“In my experience, when a <strong>WFP</strong> delegation arrives in avillage, it’s usually the men who come out first and oftenmonopolize the situation,” says Valerie Guarnieri, anAmerican whose 20-year humanitarian career – half with<strong>WFP</strong> – has taken her to many of the world’s hungerhotspots. “The women are usually a bit quiet, standingto the side. They’re often reluctant to speak out, so whatyou want to try to do is get the women alone. That’sbecause we’ve learned over the years that theparticipation of – and input into – our work is vital.”Valerie, now director of programmes, says she feels beinga woman and also a mother gives her an invaluable“edge” when it comes to humanitarian work. “There’s alevel of interaction that you have with womenbeneficiaries in the field, that is quite difficult for men tohave because there’s always going to be that boundary”.At the end of the decade, <strong>WFP</strong>’s identity had beendefined, its future secured. It had emerged from the crisisDonor response to the interlocking crises wasunprecedented in its generosity. Never before had somuch food been mobilized so quickly and distributed to somany countries. Between 1983 and 1985, <strong>WFP</strong> mounted87 separate emergency operations, delivering 2 milliontons of aid.When famine spread throughout Ethiopia in 1984-85,there was little problem finding food. Donor funding wasplentiful thanks to the efforts of “Band Aid” and “Live Aid”and other massive public appeals. But reaching thehungry in a large war ravaged country with formidableterrain and only rudimentary infrastructure and transportfacilities posed huge challenges.<strong>WFP</strong> responded in the "can-do” manner that had becomeits trademark – setting about rebuilding Ethiopia’stransport system from scratch. Ports were upgraded,airports refurbished and roads improved. A fleet of 360trucks was also assembled, which posed a problem:“Nobody knew what to do with all those trucks, so theyhired me,” recalled Ramiro Lopes da Silva. APortuguese national and former manager of Mozambiquerailways, Ramiro was signed to a year-long contract andtold to organize the fledgling truck fleet in Ethiopia. At thetime, all it had was a title: the World Food TransportOrganization in Ethiopia, or WTOE.“There were some serious teething problems at thebeginning,” remembers Ramiro. “Things were tough forseven or eight months. It got so bad that people startedjoking that WTOE stood for the ‘Worst TransportOrganization Everywhere’. But we eventually got thingsrolling, and soon we were moving 10,000 tons of reliefsupplies every month from the coast to drought strickenareas inland. By the time I left three years later, we wereoperating on a $5 million annual budget with a staff of800, made up of 12 different nationalities.”<strong>Pipeline</strong> 5