ECUADOR - Land Tenure and Property Rights Portal

ECUADOR - Land Tenure and Property Rights Portal

ECUADOR - Land Tenure and Property Rights Portal

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>ECUADOR</strong>INDIGENOUS TERRITORIALRIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF CAIMAN ANDSOUTHERN BORDERS INTEGRATION PROGRAMMARCH 2008This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency forInternational Development. It was prepared by ARD, Inc.

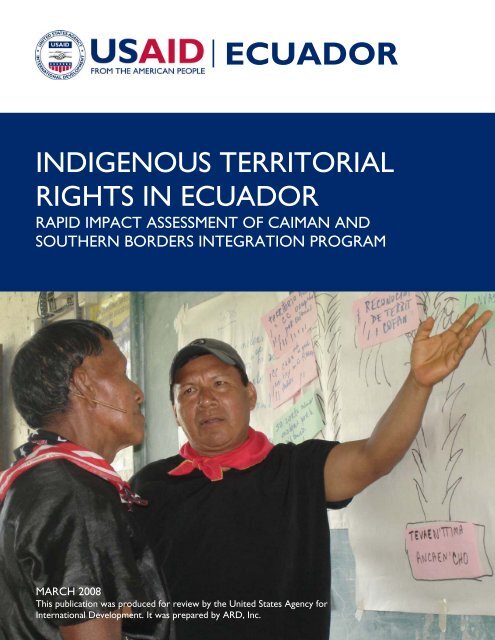

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThe impact assessment team would like to acknowledge the leadership <strong>and</strong> commitment of all entitiesconnected to this assessment that are working for the preservation of natural resources <strong>and</strong> theterritorial <strong>and</strong> cultural empowerment of Ecuador’s Indigenous Nationalities. In particular, we recognizeUSAID/Ecuador, CARE, Chemonics, International, ECOLEX, FEINCE, <strong>and</strong> FICSH whose guidance,support, <strong>and</strong> insight were instrumental to this assessment. We wish to extend our sincerest gratitude toMs. Monica Zuquil<strong>and</strong>a <strong>and</strong> Mr. Thomas Rhodes of USAID/Ecuador. The team also extends itsappreciation to ARD, Inc. for its commitment to l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> property rights (LTPR) <strong>and</strong> theopportunity to field test the LTPR assessment tool.The team has benefited from the generous contributions of individuals in both Ecuador to the UnitedStates. In Quito, we are grateful to Jorge Alvear, Jeanneth Rodriguez, Joao Stacishin de Queiroz, <strong>and</strong>Mario Añazco. In Lago Agrio, thanks goes to Emeregildo Criollo, Luis Narvaez, <strong>and</strong> Elisa Omenda. InMacas, we recognize Patricia Rivadeneira <strong>and</strong> José Acachu. Finally, in the US, we would like toacknowledge Anna Knox, Roxana Blanco, <strong>and</strong> Jessica Jackson.The evaluation was enormously enriched by the nearly 200 participants who took part in the interviews<strong>and</strong> workshops. Our underst<strong>and</strong>ing of LTPR in Ecuador was also significantly enhanced by the analysis<strong>and</strong> vision of those representing the public sector (the Ministry of the Environment <strong>and</strong> the NationalInstitute of Agrarian Development), nongovernmental organizations, <strong>and</strong> donor organizations.Finally, the team would like to thank the Cofán communities of Dureno <strong>and</strong> Duvuno, the Shuarcommunity of Angel Rouby, <strong>and</strong> the Aja Shuar women in the Guadalupe community. It was an honor forthe team to be invited into these areas <strong>and</strong> to learn from the communities about their territory realitiesof defending their territory <strong>and</strong> their visions for its protection <strong>and</strong> conservation.Prepared by:Ramon Balestino (Team Leader), Independent ConsultantPaula Bilinsky, Independent ConsultantDwight Ordoñez, Independent ConsultantAmy Regas, Independent ConsultantPrepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number PCE-1-00-99-00001-00, Task Order: 13, Lessons Learned: <strong>Property</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>and</strong> Natural Resource Management(GLT 2), under the Rural <strong>and</strong> Agricultural Incomes with a Sustainable Environment (RAISE) IndefiniteQuantity Contract (IQC).Implemented by:ARD, Inc.P.O. Box 1397Burlington, VT 05402COVER PHOTOS:FRONT: Indigenous Cofan elders in the Duvuno community discuss territorial encroachment during a rapid appraisal workshopwith the impact assessment team. Photo by Ramon Balestino, March 11, 2008.BACK: Timber processing on the outskirts of the Duvuno. Logging was cited as a major threat faced by the community in theirefforts to defend their territorial rights <strong>and</strong> protect the ecosystem. Photo by Dwight Ordoñez, March 11, 2008.

INDIGENOUS TERRITORIALRIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF CAIMAN ANDSOUTHERN BORDERS INTEGRATION PROGRAMMARCH 2008DISCLAIMERThe author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of theUnited States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

CONTENTSACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................... iEXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ iii1.0 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT.................................................................... 12.0 ASSESSMENT DESIGN...................................................................................................... 32.1 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................................... 32.2 RESEARCH SAMPLE................................................................................................................................... 42.3 LIMITATIONS............................................................................................................................................. 53.0 CONCEPTUAL MAPS: INTERVENTIONS AND OUTCOMES OF INTEREST ........ 73.1 CAIMAN PROJECT ................................................................................................................................. 73.2 SOUTHERN BORDERS PROGRAM............................................................................................................ 84.0 FINDINGS ............................................................................................................................ 94.1 CAIMAN: EXPECTED OUTCOMES OF INTEREST.................................................................................. 94.1.1 Expected Outcome 1: Effectively Interacting with External Actors RegardingTerritorial <strong>Rights</strong> (MO-7)........................................................................................................ 94.1.2 Expected Outcome 2: Indigenous Groups with Adequate Legal <strong>Rights</strong> (HO-1)..........104.1.3 Expected Outcome 3: Territorial <strong>Rights</strong> of Indigenous Communities Respected(HO-2).......................................................................................................................................114.1.4 Expected Outcome 4: Indigenous Communities Honor Legal Obligations (HO-3).124.1.5 Expected Outcome 5: Biodiversity Conservation (SO-1)..............................................134.2 CAIMAN: INTERVENTIONS..................................................................................................................144.2.1 LTPR Intervention 1: Legal <strong>and</strong> Policy Dialogue...............................................................144.2.2 LTPR Intervention 2: Community <strong>L<strong>and</strong></strong> Titling.................................................................144.2.3 LTPR Intervention 3: Conflict Mitigation/Resolution ......................................................154.2.4 LTPR Intervention 4: Co-management Agreements .......................................................154.2.5 LTPR Intervention 5: Delimiting <strong>and</strong> Demarcating Boundaries ....................................164.2.6 LTPR Intervention 6: Patrolling Boarders..........................................................................164.2.7 LTPR Intervention 7: Institutional Strengthening .............................................................174.3 SUR: EXPECTED OUTCOMES OF INTEREST .........................................................................................17INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENTi

4.3.1 Expected Outcome 1: <strong>Tenure</strong> Security (MO-1.1) ...........................................................174.3.2 Expected Outcome 2: Increased Capacity to Manage Resources Sustainably(HO-2).......................................................................................................................................184.4 PSUR: INTERVENTIONS.........................................................................................................................194.4.1 LTPR Intervention 1: Policy <strong>and</strong> Legal Issues (Titling).....................................................194.4.2 LTPR Intervention 2: Community Forestry Management ..............................................204.4.3 LTPR Intervention 3: Protected Area Management ........................................................205.0 INSTITUTIONAL STRENGTHENING .......................................................................... 215.1 CAIMAN: FEINCE...............................................................................................................................215.2 PSUR: FISCH ........................................................................................................................................216.0 SUSTAINABILITY OF LTPR AND NRM ACHIEVEMENTS....................................... 237.0 LESSONS LEARNED AND CONCLUSION.................................................................. 257.1 LTPR PROGRAMMING CONSIDERATIONS FOR INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS.......................257.2 CONCLUSIONS.......................................................................................................................................27ANNEX A: LIST OF DOCUMENTS REVIEWED..................................................................... A-1ANNEX B: LIST OF KEY INFORMANTS ................................................................................. B-1ANNEX C: CAIMAN CONCEPTUAL MAP FOR TERRITORIAL CONSOLIDATION ANDINSTITUTIONAL STRENGTHENING ........................................................................ C-1ANNEX D: PSUR CONCEPTUAL MAP FOR NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT.. D-1ANNEX E: CAIMAN OUTCOME INDICATORS AND CONTRIBUTING FACTORS........E-1ANNEX F: CAIMAN INTERVENTIONS AND RELATED OUTCOMES...............................F-1ANNEX G: PARK GUARD MONITORING DOCUMENTS.................................................... G-1ANNEX H: RAPID APPRAISAL WORKSHOP PROTOCOL.................................................H-1ANNEX I: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE ...........................................................................................I-1iiINDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

ACRONYMS ANDABBREVIATIONSCAIMANFSCFEINCEFICSHFundación CofánGTZHIHOINDALTPRLILOMIMOMOENGONRMPSURSOSOIUSAIDWCSConservation in Areas Managed by Indigenous Groups ProjectCofán Survival FoundationFederacion Indigena de la Nacionalidad Cofán del Ecuador (Indigenous Federation for theCofán Nationality in Ecuador)Inter-provincial Federation of Shuar CommunitiesFundación para la Sobrevivencia del Pueblo CofánGerman Technical CooperationHigh-level Indicators according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsHigh-level Outcomes according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsNational Institute of Agrarian Development<strong>L<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>Tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> <strong>Property</strong> <strong>Rights</strong>Low-level output indicators according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsLow-level outcomes (outputs) according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsMid-level Indicators according to PSUR or CAIMAN Conceptual MapsMid-level Outcome according to PSUR or CAIMAN Conceptual MapsMinistry of EnvironmentNongovernmental OrganizationNatural Resource ManagementSouthern Borders ProgramStrategic objective according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsStrategic objective indicator according to PSUR/CAIMAN Conceptual MapsUS Agency for International DevelopmentWorld Conservation FundINDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENTi

PREFACEThere is a continuing need to underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> communicate 1) how property rights issues change aseconomies move through various stages of economic growth, democratization, <strong>and</strong> in some cases from warto peace, <strong>and</strong> 2) how these changes require different property rights reform strategies <strong>and</strong> sequencing tofoster further economic growth, sound resource use, <strong>and</strong> political stability. The lack of secure <strong>and</strong> negotiableproperty rights is one of the most critical limiting factors to achieving economic growth <strong>and</strong> democraticgovernance throughout the developing world. Insecure or weak property rights have negative impacts on:• Economic investment <strong>and</strong> growth;• Governance <strong>and</strong> the rule of law;• Environment <strong>and</strong> sustainable resource use, including parks <strong>and</strong> park l<strong>and</strong>, mineral resources, <strong>and</strong> forestry<strong>and</strong> water resources; <strong>and</strong>• Biodiversity <strong>and</strong> sustainable resource exploitation.At the same time, robust <strong>and</strong> secure rights (along with other economic factors) can promote economicgrowth, good governance, <strong>and</strong> sustainable use of l<strong>and</strong>, forests, water, <strong>and</strong> other natural resources.USAID is making a strategic commitment to developing a stronger, more robust policy for addressingproperty rights reform in countries where it operates. “<strong>Property</strong> rights” refers to the rights that individuals,communities, families, firms, <strong>and</strong> other corporate/community structures hold in l<strong>and</strong>, pastures, water, forests,minerals, <strong>and</strong> fisheries. <strong>Property</strong> rights range from private or semi-private to leasehold, community, group,shareholder, or types of corporate rights. As l<strong>and</strong> is a main factor for economic production in most USAIDpresencecountries, it is the main focus of this Lessons Learned: <strong>Property</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>and</strong> Natural ResourcesManagement Task Order under the Rural <strong>and</strong> Agricultural Incomes with a Sustainable EnvironmentIndefinite Quantity Contract.The objectives of this task order include:1. Transferring lessons learned in property rights <strong>and</strong> natural resource management to date to USAIDmanagement, Missions, <strong>and</strong> partners;2. Developing curricula <strong>and</strong> offering courses on l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> property rights issues (including bestmethodologies <strong>and</strong> sequencing of reform steps) for staff in USAID’s geographical regions <strong>and</strong> operatingunits in Washington;3. Conducting studies on the environmental, economic, or political impacts of l<strong>and</strong> privatization or reformin USAID’s geographical regions;4. Developing <strong>and</strong> testing analytical <strong>and</strong> impact measurement tools for property rights reform in support ofprograms developed or implemented by USAID; <strong>and</strong>5. Providing USAID Missions <strong>and</strong> operating units with specific evaluation, design, <strong>and</strong> support of propertyrights reform activities.The task order is managed by ARD, Inc., on behalf of USAID. It is a mechanism of the USAID/EconomicGrowth, Agriculture, <strong>and</strong> Trade Division/Natural Resources Management/<strong>L<strong>and</strong></strong> Resources ManagementTeam. Its period of performance is August 2004 through May 2008. Dr. Gregory Myers is the task order’soperating Cognizant Technical Officer.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENTiii

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYUnder the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Lesson Learned: <strong>Property</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>and</strong> NaturalResource Management (GLT2) Task Order, ARD, Inc. developed a l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> property rights (LTPR)impact assessment tool. USAID/Washington <strong>and</strong> ARD sought to field test the tool <strong>and</strong> reached out tovarious Mission c<strong>and</strong>idates. USAID/Ecuador responded with a request for a rapid impact assessment of theConservation in Areas Managed by Indigenous Groups Project (CAIMAN, in Spanish) <strong>and</strong> the SouthernBorder Integration Program (PSUR). Both projects sought to strengthen territorial rights of indigenousnationalities: the Cofán nationality in the case of CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> the Shuar nationality in the case of PSUR.The core of the assessment team consisted of four independent consultants, aided by logistical support froma local consultant. The team applied the tool in order to underst<strong>and</strong> the impact of CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSURLTPR activities on objectives defined by the projects at their outset. In particular, the team sought to distill:1) the combination of factors that contributed to outcomes corresponding to project objectives; <strong>and</strong> 2) theoutcomes resulting from the LTPR interventions implemented by the projects, whether they were expectedor unexpected.For each project, a conceptual map was developed to: (a) characterize the LTPR intervention-to-outcomerelationships as conceived in project design; <strong>and</strong> (b) pinpoint higher-level expected outcomes against whichimpact would be assessed. This information was drawn from project documentation <strong>and</strong> interviews withproject implementing organizations.In order to assess impact, the team drew on both primary <strong>and</strong> secondary information sources. Projectdocumentation from CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR, as well as other relevant materials relating to the identifiedoutcomes, was reviewed. Interviews <strong>and</strong> rapid appraisal techniques were employed to gather informationfrom stakeholders <strong>and</strong> other key informants in Quito, Lago Agrio, <strong>and</strong> Macas from March 3–15, 2007. Theseindividuals were selected using a purposeful non-r<strong>and</strong>om sampling approach. The team consulted with Shuar<strong>and</strong> Cofán indigenous beneficiaries, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), public sector actors, <strong>and</strong>donors.The main findings of the assessment respond to three key questions:To what extent did CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR LTPR interventions contribute to their objectives?CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR have contributed to several positive outcomes, including more secure legal rights toindigenous territories, improved protection of territorial limits, <strong>and</strong> strengthened capacity of indigenousorganizations in assisting communities to better protect their territorial rights <strong>and</strong> conserve the resourceswithin those territories. Within each project, the assessment has uncovered promising approaches thatwarrant future consideration:• CAIMAN: Territorial consolidation has shown the benefits of multiple, interconnecting LTPRinterventions in achieving positive <strong>and</strong> lasting outcomes. CAIMAN’s successful efforts with theIndigenous Federation for the Cofán nationality in Ecuador (Federacion Indigena de la Nacionalidad Cofán delEcuador, FEINCE) have demonstrated the benefits of investing institutional strengthening, while theproject’s support for park guards <strong>and</strong> demarcation of boundaries have enhanced territorial defense.• Southern Border Integration Program: PSUR’s multi-sectoral approach reveals the importance ofworking with indigenous nationalities in a manner that simultaneously addresses their differentdevelopment needs.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENTv

While CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR contributed to attainment of targeted outputs <strong>and</strong> lower-level outcomes, findingssuggest that their contributions toward higher-level outcomes—associated with territorial integrity,productive investment, <strong>and</strong>/or biodiversity conservation—have been limited.What was the efficacy of project approaches for achieving sustainable impact?The sustainability of CAIMAN’s <strong>and</strong> PSUR’s distinct approaches to strengthening territorial rights wasassessed through multiple lenses.• Cultural <strong>and</strong> Social Sustainability: There have been positive changes in public opinion on naturalresource conservation both at the national <strong>and</strong> indigenous community levels.• Institutional Sustainability: Increases in financial, administrative, <strong>and</strong> technical capacities of FEINCEto defend Cofán territory clearly attained a level of sustainability.• Economic Sustainability: Effective, conservation-friendly methods to generate income for indigenouspeople have yet to be widely introduced <strong>and</strong> exp<strong>and</strong>ed in the northern <strong>and</strong> southern border areas.• Political Sustainability: The assessment revealed the importance of separating the technical aspects ofdefending territorial rights from its political elements. One factor that appears to be have contributed tothe Cofán’s success in defending <strong>and</strong> conserving its territories is that technical support for these actions iskept separate from FEINCE, the political arm of the Cofán.• Sustainability of CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR Impact: Since termination of CAIMAN, respondents did notindicate a decline in FEINCE’s effectiveness or in the Cofán’s commitment to securing their territorialrights. In the case of PSUR, although the federation was executing titling activities by the end of theproject, it has not developed the fiscal resources nor maintained the technical capacity to title l<strong>and</strong> on itsown.What are the implications for future LTPR programming to support indigenous territorialrights?The findings of the assessment suggest various considerations for future USAID/Ecuador programming inthe realm of indigenous territorial rights.• Resist generalization across indigenous groups: Cultural, geographical, <strong>and</strong> contextual differences ofindigenous nationalities (<strong>and</strong> communities within) must be carefully considered. These factors will shapethe ultimate success of interventions.• Shifting indigenous value systems: Under traditional practices, indigenous groups may be goodstewards of natural resources; however, economic pressures <strong>and</strong> the absorption of western values areincreasingly challenging these traditions. Project designs need to address these changes.• Integrated approach: An LTPR approach that enhances both the legal <strong>and</strong> social recognition of rights,supports mechanisms to defend those rights, <strong>and</strong> strengthens local institutions such that they can carryon these functions, will yield more sustainable results. Titling by itself is unlikely to lead to tenure securityor sustainable natural resources management.• Community vs. individual titles: Inalienable community l<strong>and</strong> titles are more suited to maintaining thelong-term territorial integrity of indigenous communities’ ancestral l<strong>and</strong>s than are individual titles.• Government involvement: Government obligations around monitoring <strong>and</strong> enforcement need to befulfilled at local <strong>and</strong> national levels if impacts on securing territorial rights are to be sustained.viINDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

• Relationship of livelihoods to conservation: Consideration should be given to livelihood activities thatoffset the need to rely on resource extraction to meet basic needs as well as respect indigenouscommunities’ priorities, values, <strong>and</strong> geographical constraints.• Focus on higher-level outcomes: LTPR projects need to monitor progress toward higher-levelobjectives (e.g., tenure security, reduced encroachment, biodiversity conservation) as much as outputs(e.g., titles, management plans).In light of the impacts sustained by past projects, continued support for strengthening the territorial rights ofindigenous nationalities within Ecuador is recommended. Projects should continue support for strengtheningthe capacity of indigenous organizations to secure <strong>and</strong> defend territorial rights as well as building the capacityof communities themselves to demarcate territory <strong>and</strong> defend their borders. Nevertheless, more concertedefforts should be directed toward: 1) introducing conservation-friendly livelihood opportunities; 2)augmenting the financial sustainability of indigenous organizations; 3) addressing the growth in outsidepressures confronted by indigenous groups in defending their territories; <strong>and</strong> 4) eliciting stronger supportfrom relevant government entities in enforcing territorial rights. Finally, it is critical that LTPR interventionsto support territorial rights are informed by indigenous communities <strong>and</strong> implemented in a manner thataddresses the differing circumstances of each nationality.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENTvii

1.0 PURPOSE AND SCOPE OFASSESSMENTUnder the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Lesson Learned: <strong>Property</strong> <strong>Rights</strong> <strong>and</strong> NaturalResource Management (GLT2) Task Order, ARD, Inc. developed a l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong> property rights (LTPR)impact assessment tool. This tool was crafted to assist USAID Missions assess impact of l<strong>and</strong> tenure <strong>and</strong>property rights (LTPR) interventions <strong>and</strong> derive important lessons that can inform future programming. Itcomprises the sixth volume in a series of LTPR tools.Following a USAID review <strong>and</strong> subsequent revision of the draft impact assessment tool,USAID/Washington <strong>and</strong> ARD sought to field test the tool <strong>and</strong> reached out to various Mission c<strong>and</strong>idates.USAID/Ecuador responded by requesting a rapid impact assessment of the Conservation in Areas Managedby Indigenous Groups Project (CAIMAN, in Spanish) <strong>and</strong> the Southern Border Integration Program (PSUR).Specifically, the assessment called for an analysis of: (a) the extent to which higher order CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSURobjectives were met; (b) expected <strong>and</strong> unexpected outcomes of CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR interventions; (c)efficacy of project approaches for achieving a sustainable impact; <strong>and</strong> (d) lessons learned.The scope of the assessment centered upon:• CAIMAN efforts to strengthen territorial rights of the Cofán nationality—particularly within theprovince of Sucumbios; <strong>and</strong>• PSUR support to enhance territorial rights of the Shuar nationality within the province of MoronaSantiago.It is important to point out that both CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR encompassed other components in addition tosupport for territorial rights, <strong>and</strong> each covered extensive geographic areas. A comprehensive analysis of theprojects, however, was beyond the scope <strong>and</strong> resources of this assessment.Overall, this assessment seeks to guide future decision making in terms of effective <strong>and</strong> sustainable ways tosupport indigenous groups in consolidating territorial rights <strong>and</strong> protecting natural resources.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 1

2.0 ASSESSMENT DESIGN2.1 METHODOLOGYThe assessment team was constructed to balance technical sector <strong>and</strong> programmatic expertise; the coreconsisted of four independent consultants: an LTPR specialist, a Monitoring <strong>and</strong> Evaluation (M&E)specialist, an evaluation specialist, <strong>and</strong> an institutional development specialist. Throughout the fieldwork, theteam received logistical support from three host country nationals: one previously affiliated with CAIMAN<strong>and</strong> the other two from CARE-Quito <strong>and</strong> CARE-Macas. ARD’s <strong>L<strong>and</strong></strong> <strong>Tenure</strong> <strong>and</strong> Natural ResourceGovernance Specialist also accompanied the team <strong>and</strong> observed the use of the LTPR tool throughout theevaluation.The study utilized the LTPR Impact Assessment Tool as its touchstone methodology. Qualitative in nature,the tool seeks to underst<strong>and</strong> impact from two distinct angles: (a) Outcomes–“What were the combination ofcauses that resulted in the given change or outcome?”; <strong>and</strong> (b) Interventions–“What changes or outcomesresulted from the given intervention?” Together, these questions help establish the extent to which LTPRinterventions contributed to their objectives as well as to other unanticipated outcomes.As the foundation of the LTPR assessment, CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR conceptual maps were designed throughanalyzing relevant project documentation <strong>and</strong> consulting with USAID/Ecuador <strong>and</strong> project implementingorganizations. The maps served as theoretical depictions of the outcomes that, according to project design,were expected to emerge from interventions. The team elected to focus on assessing change in higher orderoutcomes as they correspond to intended project impact. Annexes C <strong>and</strong> D provide the conceptual maps ofeach project.Data was gleaned from primary <strong>and</strong> secondary sources. Secondary collection included a review of technicalsector reports as well as CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR documents: quarterly reports, project evaluations, performancedata, <strong>and</strong> USAID reports. Primary data collection consisted of fieldwork in Quito, Lago Agrio, <strong>and</strong> Macasfrom March 3–15, 2007. Activities were conducted through the following means:• Semi-structured Interviews: Government representatives, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs),project staff, <strong>and</strong> key informants were interviewed in each location (Quito, Lago Agrio, <strong>and</strong> Macas).• Rapid Appraisal Workshops: A total of four workshops, disaggregated by gender, were conducted withthe Cofán nationality: two in the Duvuno community (with 7 women <strong>and</strong> 11 men); <strong>and</strong> two in theDureno community (13 women; 8 men). Translators were hired to enable those who did not speak (orwere not comfortable speaking) Spanish to participate. Additionally, pictures <strong>and</strong> symbols were utilizedto encourage participation <strong>and</strong> close the literacy gap among respondents (see Annex H for the rapidappraisal protocol).• Group Observation <strong>and</strong> Inquiry: In Lago Agrio, the team observed <strong>and</strong> interacted with an annualassembly of Cofán community representatives (2 women <strong>and</strong> 38 men). In Centro Angel Rouby, teammembers attended a Shuar assembly held to elect local community leaders during which they observedongoing dialogues <strong>and</strong> posed a small number of evaluative questions (27 women <strong>and</strong> 43 men).• Supplementary Interviews: When needed, complementary interviews were conducted to verifyinformation or deepen that which was already gleaned.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 3

Although data analysis was iterative across the evaluation, its emphasis took place upon the conclusion offieldwork. The analytical phase kicked off with the presentation of preliminary findings to USAID/Ecuadorstaff for feedback <strong>and</strong> recommendations. A content <strong>and</strong> frequency analysis was performed afterward inproject outcome <strong>and</strong> intervention data organized in Excel spreadsheets. Triangulation techniques wereutilized to analyze the responses of key informants <strong>and</strong> identify repeated attributions that highlight patterns ofcausality <strong>and</strong> impact as well as important differences in perceptions.2.2 RESEARCH SAMPLEA purposeful non-r<strong>and</strong>om sampling approach was utilized to examine PSUR <strong>and</strong> CAIMAN stakeholders. 1 Inexamining this sample (composed principally of project beneficiaries, public sector officials <strong>and</strong> key NGOactors), the evaluation sought to determine the level <strong>and</strong> sustainability of impact upon a segment ofindigenous beneficiaries.TABLE 2.1: CAIMAN SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICSSAMPLEPOPULATION ASSESSMENT METHODIndigenous project Rapid appraisal workshops, semi-structuredbeneficiaries (Cofán interviews, group observation <strong>and</strong> inquiry,nationality)individual interviewsGovernment stakeholders(local <strong>and</strong> national levels)NGO stakeholders (local<strong>and</strong> national levels)SAMPLE GENDERSIZE CHARACTERISTICS79 22 women57 menSemi-structured interviews 8 1 woman7 menSemi-structured interviews, supplementary 19 2 womeninterviews17 menTOTAL: 106 25 women; 81 menTABLE 2.2: PSUR SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICSSAMPLEPOPULATION ASSESSMENT METHODIndigenous projectbeneficiaries (Shuarnationality)SAMPLESIZEGroup observation & inquiry 70 27 women43 menGENDERCHARACTERISTICSGovernment stakeholders(local <strong>and</strong> national levels)Semi-structured interviews 3 1 woman2 menDonor (GTZ) Semi-structured interviews 1 1 manNGO stakeholders (local<strong>and</strong> national levels)Semi-structured interviews 13 1 woman12 manTOTAL: 87 29 women; 58 menAs seen in Tables 2.1 <strong>and</strong> 2.2, a total of 193 informants were interviewed across the assessment. Selectioncriteria for the participants included: gender <strong>and</strong> indigenous nationality (in the case of communitystakeholders) <strong>and</strong> project affiliation or technical sector focus. Data from these key stakeholder groups weresystematically collected <strong>and</strong> compared across each project.1Selection of informants within this sample was principally driven by the implementing organizations: CARE (for PSUR) <strong>and</strong> the ex-CAIMAN Grants Manager (for CAIAMAN).4 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

2.3 LIMITATIONSThis assessment had various limitations that warrant illumination. First, the team was simultaneously chargedwith addressing two statements of work: one calling for the assessment of USAID/Ecuador’s LTPR efforts<strong>and</strong> another for the pilot testing <strong>and</strong> appraisal of ARD’s LTPR assessment tool. This dual focus prevented amore robust assessment, as sacrifices were required in terms of scope, level of effort, <strong>and</strong> time on the ground.Another key constraint was the challenging logistical nature of examining LTPR efforts in remote indigenouscommunities. This reality, combined with limited fieldwork time, precluded a more extensive sample. Instead,it required fieldwork to take place in the most logistically convenient indigenous communities within theCofán <strong>and</strong> Shuar territories.The study recognizes the limitations of an impact assessment that focuses upon select communities withintwo of Ecuador’s numerous indigenous nationalities. From the geographic location, to the level oforganization among representative entities, to the type <strong>and</strong> level of external threats, each nationality (<strong>and</strong>communities within) is distinct. While recommendations drawn form the analysis attempt to provide somegeneral LTPR guidance, it is far form prescribing a one-size-fits-all approach.Equally important, this study was not able to interview external stakeholders that may have been impacted byLTPR interventions or have alternative views about their outcomes (e.g., bordering indigenous nationalities,colonists, or companies). As external stakeholders are seen to possess an interdependent relationship to theefficacy of LTPR interventions <strong>and</strong> sustainability of succeeding outcomes, their absence in this analysis wasconsidered significant.Finally, <strong>and</strong> as seen in Tables 2.1 <strong>and</strong> 2.2, the level of time <strong>and</strong> effort spent reviewing PSUR activities wascomparatively less than CAIMAN due to limited time <strong>and</strong> resources. While this constraint was discussed withUSAID/Ecuador at the outset of the assignment, a rapid assessment of PSUR’s LTPR activities in Macas wasnonetheless considered valuable to Mission learning.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 5

3.0 CONCEPTUAL MAPS:INTERVENTIONS ANDOUTCOMES OF INTERESTThe assessment design drew from the CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSUR conceptual maps. The conceptual mappingexercise served two purposes: (a) to characterize each project’s LTPR intervention-to-outcome relationshipsas conceived in project design; <strong>and</strong> (b) to pinpoint higher-level expected outcomes against which impactwould be assessed. The following provides an overall description of this process within each initiative.3.1 CAIMAN PROJECTImplemented from 2002–2007, the CAIMAN project possessed the overarching goal of conservingbiodiversity in Ecuadorian indigenous territories. Activities were implemented under three thematic areas:territorial consolidation, financial sustainability, <strong>and</strong> institutional strengthening. While all themes areinterconnected, the assessment focused upon territorial consolidation <strong>and</strong> the crosscutting area ofinstitutional strengthening.CAIMAN’s approach to territorial consolidation involved a chain of mutually supporting LTPRinterventions designed to enable indigenous groups to control (via support for legal rights to ancestral l<strong>and</strong>),defend (via mechanisms to protect legal rights), <strong>and</strong> conserve their associated l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> resources. Complementingthis area was institutional strengthening of indigenous representative organizations, which helps theirconstituent communities secure <strong>and</strong> defend territorial rights among other duties.Between these two CAIMAN themes, seven key LTPR-related interventions were identified: (a) Legal <strong>and</strong>Policy Dialogue; (b) Communal Titling; (c) Conflict Mitigation/Resolution; (d) Co-management Agreements;(e) Delimiting <strong>and</strong> Demarcating Boundaries; (f) Patrolling Borders; <strong>and</strong> (g) Institutional Strengthening.As part of the conceptual mapping process, key anticipated outcomes for each CAIMAN LTPR interventionwere identified from project documentation <strong>and</strong> interviews from executing agencies. Stemming from eachintervention, a series of low-level outcomes (or outputs) as well as mid- <strong>and</strong> high-level outcomes wereidentified. As the assessment was most concerned with determining impact, the following five outcomes ofinterest were selected:• Mid-level: (i) Effectively interacting with external actors regarding territorial rights;• High-level: (ii) Indigenous groups with adequate legal rights, (iii) territorial rights of indigenouscommunities respected, <strong>and</strong> (iv) indigenous communities honor legal obligations; <strong>and</strong>• Strategic Objective Level: (v) Biodiversity conservation.As a next step, indicators corresponding to each of these outcomes were identified as proxies forcharacterizing change. The indicators drove the methodology in assessing the outcome-side of CAIMAN’simpact <strong>and</strong> are highlighted in the CAIMAN Conceptual Map (see Annex C).INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 7

3.2 SOUTHERN BORDERS PROGRAMFrom 2000–2007, PSUR was implemented along the Ecuador-Peru border as a multi-sectoral developmentprogram. The totality of PSUR encompassed four major components: income generation; social services(water <strong>and</strong> sanitation); local government; <strong>and</strong> natural resource management. The assessment centered uponthe relatively small natural resources management (NRM) component.The overarching objective of PSUR’s NRM component was to improve the management of natural resourcesin select areas along the southern border. Under NRM, the assessment examined three of five originallydesigned subcomponents or major LTPR interventions: (a) Protected Area Management; (b) CommunityForestry Management; <strong>and</strong> (c) Policy <strong>and</strong> Legal Issues.Through review of the project literature, the team produced a conceptual map that associated theseinterventions with expected outcomes. Two were then chosen as the focus of the assessment:• Mid-level: (i) <strong>Tenure</strong> security; <strong>and</strong>• High-level: (ii) Increased capacity to manage natural resources sustainably.Indicators were then designed for these outcomes of interest <strong>and</strong> are highlighted on the PSUR conceptualmap (see Annex D).8 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

4.0 FINDINGSThis section analyzes the responses to key questions posed by the assessment related to CAIMAN <strong>and</strong> PSURinterventions <strong>and</strong> outcomes of interest.First, the outcome-side of the inquiry is examined to determine: What were the combination of causes that resulted ina given change or outcome? For each outcome of interest, the analysis includes: (i) a description of the indicatorselected to approximate it; (ii) the change in indicator state <strong>and</strong> the factors contributing to this change asperceived or documented by the multiple sources consulted; <strong>and</strong> (iii) the degree to which the LTPRinterventions of the respective projects contributed to achieving expected outcomes, according to the sourcesconsulted.The intervention-side of the inquiry is subsequently assessed <strong>and</strong> considers: What changes or outcomes resulted fromthe given intervention? Under each intervention, the analysis is organized as follows: (i) description of theintervention; <strong>and</strong> (ii) outcomes seen to emerge from those interventions.In an effort to provide a summative underst<strong>and</strong>ing of findings as well as highlight recurring data, theresponses by each of the informants consulted for the CAIMAN project have been included in Annex E <strong>and</strong>F.4.1 CAIMAN: EXPECTED OUTCOMES OF INTEREST4.1.1 Expected Outcome 1: Effectively Interacting with External Actors RegardingTerritorial <strong>Rights</strong> (MO-7)Description of Targeted Indicator: CAIMAN dedicated significant effort to the institutional strengtheningof Indigenous Federation for the Cofán Nationality in Ecuador (Federacion Indigena de la Nacionalidad Cofán delEcuador, FEINCE). The project’s efforts were aimed not only at creating an organization that can crediblyrepresent the Cofán people, but also at developing an entity that successfully defend the Cofán’s territorialclaims. Thus, the indicator (MI) selected to measure this mid-level outcome (MO) was: Perception that theFederation is effectively managing territorial issues with external actors (MI-1 <strong>and</strong> MI-7).Change in Indicator States <strong>and</strong> Contributing Factors: Evidence of the maturation of FEINCE sinceCAIMAN began its work with the institution is obvious. A large number of the informants consultedaffirmed that in 2002 FEINCE existed only on paper. It had no staff, office, phone or lines, it carried debt,<strong>and</strong> it possessed no credibility with its Cofán constituency. Today, 19 individuals work in FEINCE’s wellequippedoffices. According to informants, the institution has established financial <strong>and</strong> accountingprocedures, manages projects, <strong>and</strong> receives funding from international organizations <strong>and</strong> the government ofEcuador, indicating significant institutional improvement.However, the question corresponding to the indicator remains: is FEINCE effectively managing territorialissues with external actors? From the perspective of the majority of those sampled, the answer is yes. Thecausal factor most cited for this improvement was CAIMAN’s institutional support of FEINCE. The otherprominent factor identified by multiple stakeholders was FEINCE’s relationship to <strong>and</strong> support by theFundación para la Sobrevivencia del Pueblo Cofán (also know as Fundación Cofán).INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 9

Community members as well as NGO <strong>and</strong> government representatives provided numerous examples of howFEINCE is effectively managing territorial issues. These included: (a) the successful negotiation that led tothe recent titling of Cofán ancestral territory in Rio Cofánes; (b) FEINCE’s positive reputation with localgovernment officials; (c) the canton (municipality) of Nueva Loja providing the Cofán a space in themunicipal park to sell h<strong>and</strong>icrafts; (d) the Cofán’s ability to leverage support from the local military; <strong>and</strong> (e)the improved relationship with the Fundación Cofán, which further strengthens FEINCE’s territorial defensecapabilities.At the community level in Dureno <strong>and</strong> Duvuno, opposing views about FEINCE were also expressed. Certaincommunity members felt that FEINCE was not providing adequate support to the Cofán community.Supplementary information gained from informants (i.e., not directly related to the query) reveals thefollowing possible explanations for these negative perceptions:• FEINCE’s leadership: Certain community members expressed discontent that FEINCE is led by acolonist (as opposed to a Cofán) who does not speak the Cofán language; <strong>and</strong>• FEINCE’s relationships to communities: The relationship between FEINCE <strong>and</strong> the Durenocommunity is stronger <strong>and</strong> more active than that with the Duvuno community. Distance betweenFEINCE <strong>and</strong> the communities as well as community leadership can all factor into this equation.Relevance of CAIMAN Interventions to Outcomes of Interest: Most stakeholders see CAIMAN’s role asa primary contributor to FEINCE becoming a more organized, capable institution. While CAIMAN hasclearly contributed to FEINCE’s improved ability to interact with external actors around territorial rights,evidence is much weaker in terms of the organization’s ability to attain higher-level LTPR outcomes (HOs):indigenous groups with adequate legal rights (HO-1); territorial rights of indigenous communities respected (HO-2); <strong>and</strong>indigenous communities honor legal obligations (HO-3). This, however, is seen by the assessment as part of a naturalprocess. Institutional strengthening occurs in a building block manner that necessitates stages. In the past fiveyears, FIENCE has made exceptional progress through solidifying operational, electoral, <strong>and</strong> administrativeprocesses; it now possesses a solid foundation upon which these higher-level outcomes may be secured.4.1.2 Expected Outcome 2: Indigenous Groups with Adequate Legal <strong>Rights</strong>(HO-1)Description of Targeted Indicator: Secure, defendable, <strong>and</strong> enforceable legal rights are vital to the abilityof indigenous nationalities to defend against encroachment <strong>and</strong> invasion of their territories. Legal rights alsoform one of the pillars of territorial integrity. 2 Two high-level outcome indicators (HIs) were identified tomeasure the adequacy of indigenous nations’ legal rights: (a) perception the state will support legal claims; <strong>and</strong>(b) perception of secure tenure status. The team selected the former, Perception the state will support legal claims(HI-1), to measure this indicator.Change in Indicator States <strong>and</strong> Contributing Factors: Respondents generally indicated that the statecurrently supports legal claims of indigenous nationalities. The majority of respondents described animprovement in state support between 2002 <strong>and</strong> the present. Yet those citing a positive trend—<strong>and</strong> thepolitical will bolstering it—often noted government resource constraints as seriously compromising theState’s ability to act. An example can be seen in the Lago Agrio office of the National Institute of AgrarianDevelopment (INDA), which is staffed by one technician who is responsible for preparing legalizationpaperwork <strong>and</strong> investigating property disputes for Sucumbios Province. At both local <strong>and</strong> national levels,2Territorial integrity is defined here as a state whereby a community’s l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> natural resources can be controlled <strong>and</strong> defended in orderthat it can be conserved.10 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

concrete actions that provide indigenous groups with adequatelegal rights are perceived as significantly restricted by insufficientgovernment resources.“It is not that outsiders respectour territory, we have made themrespect it.”–FEINCE officialThe increase in state support over the past years was attributed toa combination of factors. The two most often cited were: (i) theorganizational advancements of indigenous entities; <strong>and</strong> (ii) the political will <strong>and</strong> posture of the currentgovernment. The 1998 Constitution’s guarantee of indigenous territorial rights, civil society pressure, <strong>and</strong>public opinion were also named as factors precipitating this change. Interestingly, only two parties mentionedtitling as a contributing factor to the state’s increased support of legal claims of indigenous nationalities.Relevance of CAIMAN Interventions to Outcome of Interest: Collected data reveals multiple causes forpositive change around state support for legal claims to indigenous territory, though CAIMAN was not notedas one of these causes. Yet, CAIMAN was associated with the organizational advancement of indigenousfederations—cited as a primary causal factor in promoting positive change in state support for legal claims.Specifically, this relationship can be traced to CAIMAN’s institutional strengthening efforts of FEINCE <strong>and</strong>likely other indigenous federations as well.Today, FEINCE’s enhanced institutional capacity <strong>and</strong> ability to work with external stakeholders appear tohave enabled success in obtaining state support for Cofán territorial“The government will support the claims. This was recently demonstrated as FEINCE successfullyCofán with police force. Backing negotiated with the canton of La Bonita to register title of 30,000up the Cofán is backing up the hectares within Area Rio Cofánes, despite strong opposition frompresident.”other interests. CAIMAN’s institutional strengthening efforts appear–Local government official to have played an important role in FEINCE’s current capacity tosecure legal claims to ancestral territory.4.1.3 Expected Outcome 3: Territorial <strong>Rights</strong> of Indigenous CommunitiesRespected (HO-2)Description of Targeted Indicator: CAIMAN sought to empower indigenous nationalities with knowledge<strong>and</strong> practical tools (through border patrols, boundary delimitation, trained paralegals, etc.) to better protect<strong>and</strong> defend their territory. Two high-level indicators were identified for this outcome: (a) incidences ofencroachment; <strong>and</strong> (b) perception of external stakeholder respect for indigenous territory. The high-levelindicator selected to assess this outcome was: Perception of external stakeholder respect for indigenous territory (HI-4)Change in Indicator States <strong>and</strong> Contributing Factors: Overall, respondents perceived that there isimproved respect for indigenous territory. The Cofán’s enhanced capacity to patrol <strong>and</strong> defend againstincursions was specifically mentioned. However, in terms of external respect for territory, significantpressures were seen to persist from outsiders seeking resources for individual/community consumption orfor commercial purposes.The respondents cited three primary reasons––all driven by Cofán territorial defense efforts—forimprovements in external respect: (i) park <strong>and</strong> forest guards; (ii) demarcation, delimitation, <strong>and</strong> conflictresolution along borders; <strong>and</strong> (iii) positive relationships with external actors <strong>and</strong> local authorities (e.g. Cofánability to call on local military assistance). Additional causes cited included the Cofán’s own will <strong>and</strong>knowledge, the Constitution, <strong>and</strong> corresponding political recognition of indigenous rights, l<strong>and</strong> titles, <strong>and</strong> civilsociety pressure. Importantly, government respondents (particularly at the national level) noted an improvedlegal atmosphere, but appear to be limited in mitigating the intentions <strong>and</strong> efforts of multinational companies’utilization of natural resources.Relevance of CAIMAN Interventions to Outcome of Interest: A majority of respondents answered thisquestion along two lines of thought. On the one h<strong>and</strong>, external regard for territory has in large part remainedINDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 11

the same. On the other h<strong>and</strong>, the ability of Cofán communities to defend their territory has increased, partlyas a result of CAIMAN’s territorial interventions. For example, the Kichwa-14 agreement, which transferred aportion of Cofán territory to the neighboring indigenous Kichwa community, is credited for reducingincursions in Dureno. In Cofán Bermejo, Cofán park guards <strong>and</strong> Ministry of the Environment (MOE) parkguardsworked together to form a human barrier that prevented the China National Petroleum Corporationfrom entering the reserve. Finally, in Dureno <strong>and</strong> Duvuno, targeted outreach sensitizing neighboringcolonists about collective rights has helped to reduce encroachment. CAIMAN’s territorial consolidationapproach contributed to a number of defense-oriented tools that appear to be generating degrees of externalrespect for their territory.4.1.4 Expected Outcome 4: Indigenous Communities Honor Legal Obligations(HO-3)Description of Targeted Indicator: In effort to measure the level to which indigenous communities honorlegal obligations, the assessment selected the high-level outcome indicator: Perception of degree of community'scompliance with co-management agreements <strong>and</strong> NRM plans (HI-6). In protected areas, co-management agreementsserve as the formal recognition of a legal right to l<strong>and</strong>. NRM plans are prerequisites to titling or signing comanagementagreements. Upon analysis of information gleaned, however, it was recognized that thisindicator did not elicit precise information on co-management agreements <strong>and</strong> NRM plans. Instead, thephrasing of the indicator provoked discussion around a range of formal <strong>and</strong> informal NRM plans, includingthose linked to co-management agreements, titling, forestry plans, <strong>and</strong> the community’s formal <strong>and</strong> informalNRM processes. In addition, significantly less data was collected on this indicator in comparison to theothers. The results below attempt to sort the responses according to how the question was interpreted by theinformants.Change in Indicator States <strong>and</strong> Contributing Factors: Although compliance levels vary by indigenouscommunity, overall responses did not indicate strong compliance with resource use regulations as establishedin NRM plans. For example, in the community of Sinangue, the outdated NRM plan is completely ignored,while in the community of Savalo, the plan is reportedly followed to the letter (e.g., any family killing morethan the three allotted birds per year is fined $50). Yet Savalo appears to be the exception. In most cases, theNRM plans are developed <strong>and</strong> agreed upon as a way to satisfy a government requirement in order to obtain atitle or co-management agreement.In those cases where communities are honoring these legal obligations, respondents cited variouscontributing factors: (i) the existence of income generating activities that allow community members to meetfamily needs without depleting natural resources (most important); (ii) community participation in NRMplanning; (iii) support for NRM plan implementation from NGOs; <strong>and</strong>; (iv) FEINCE’s conservation focus.Relevance of CAIMAN Interventions to Outcome of Interest: It does not appear that CAIMAN’sinterventions have contributed to improving indigenous communities’ compliance of legal obligationssurrounding resource management. Indigenous communities will most often comply with co-management<strong>and</strong> NRM plans if they see the value in doing so, if doing so fits into their own rules, objectives, <strong>and</strong> way oflife, or if there are serious consequences for not doing so. This in mind, it is important to note that whilenon-compliance of NRM use regulations is grounds for cancellation or non-renewal of co-managementagreements, minimal or non-existent monitoring on the part of the MOE facilitates such trends. The currentlack of resources around MOE monitoring is illustrated by the fact that only two ministry park guards areresponsible for patrolling 375,000 hectares of the Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve where the Cofán have aco-management agreement.12 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

4.1.5 Expected Outcome 5: Biodiversity Conservation (SO-1)Description of Targeted Indicator: Biodiversity within Cofán indigenous territories is threatened by adiverse number of actors, including: (a) actors outside the territories that are contaminating water, soil, <strong>and</strong> airthat flow into the territories; (b) Cofán communities that extract resources on their own l<strong>and</strong>; <strong>and</strong> (c) actorsoutside areas who encroach, invade, or negotiate access to l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong>/or resources. Key threats stem frompetroleum exploration <strong>and</strong> extraction, logging, mining, hunting, fishing, <strong>and</strong> medicinal plant harvesting. Theoverall purpose of the CAIMAN project was to conserve biodiversity in the chosen protected areas <strong>and</strong>buffer zones managed by indigenous groups. The strategic objective indicator (SOI) selected to measure theproject’s highest-level outcome was: Perception that natural resources within indigenous territories are utilized by all actorsin a sustainable manner (SOI-1).Change in Indicator States <strong>and</strong> Contributing Factors: This indicator yielded mixed responses. Half of thesample indicated positive change between 2002 <strong>and</strong> 2008. The other half noted that there had been nochange or negative change in sustainable natural resource use by all actors over this time period. There is noclear pattern to this split in viewpoints. Cofán community members fell on both sides of the fence, withDureno men exhibiting a more positive attitude than Duvuno men. Women in both communities say thesituation has worsened. For the most part, NGO representatives reported that the situation has improved,while government representatives stated it has not. Potential reasons for divergent views perceived by theassessment team include:• Awareness of Contrary Forces: Pressures are simultaneously being exerted in support of <strong>and</strong> againstconservation (e.g., communities are regulating their own hunting/fishing but simultaneously experiencingan increased number of encroachments from neighbors);• Diverse Community Realities: The interpretation of “sustainable use of natural resources by all actors”differs across communities <strong>and</strong> is influenced by numerous factors including: culture, external <strong>and</strong> internalpressures, external support, <strong>and</strong> level of private-sector penetration; <strong>and</strong>• Diverse Perspectives <strong>and</strong> Frames of Reference: Differences in gender, age, location, or social statusmay affect how one perceives this indicator. As an example, one community member’s response focusedon quantity of medicinal plants while another’s focused on the departure of the oil company.When positive change in sustainable resource use was articulated, respondents attributed territorialcontrol/park guards as a primary cause. At the local level, community regulations for resource management<strong>and</strong> the departure of oil interests were mentioned as contributing factors. At the NGO/government level,multiple respondents cited the Constitution <strong>and</strong> the government’spolitical will. When negative change was assessed, the primarycauses cited were invasion/encroachment, pressure placed byexternal actors, <strong>and</strong> oil contamination. Multiple respondentshighlighted the profit driving motives of companies as, “they will gowhere there resources are.” Respondents also made clear that whencompanies depart, the environmental situation improves.“Before, there were lots ofanimals <strong>and</strong> fish. Now I go fivedays without eating.”–Cofán elder from Ch<strong>and</strong>iannaeRelevance of CAIMAN Interventions to Outcome of Interest: While progress has been made, thereappears to be a long road ahead toward achieving sustainable natural resource use by all actors. In the case ofthe Cofán, CAIMAN’s efforts aimed at territorial control seem to have given a boost to their ability to defend<strong>and</strong> protect their resources. Although CAIMAN’s efforts are seen to positively contribute to the strategicobjective of biodiversity conservation, other critical factors (e.g., the weakness of government capacity toenforce resource management regulations) seem to severely limit achievement of sustainable resource use <strong>and</strong>biodiversity conservation.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 13

4.2 CAIMAN: INTERVENTIONS4.2.1 LTPR Intervention 1: Legal <strong>and</strong> Policy DialogueDescription of Intervention: The 1998 Ecuador Constitution established a legal basis that encouragedadvances by indigenous nationalities with respect to territorial consolidation. The Constitution gaverecognition to the political <strong>and</strong> civil rights of indigenous communities, including collective territorial rights.The CAIMAN project implemented outreach activities to inform indigenous community members aboutthese constitutionally based rights through workshops <strong>and</strong> brochures written in Spanish <strong>and</strong> relevantindigenous languages. In addition, the project trained paralegals selected from the Cofán communities in howto negotiate <strong>and</strong> defend their territorial rights <strong>and</strong> acquainted them with laws on agrarian development,mediation <strong>and</strong> arbitration, forestry, <strong>and</strong> others subjects. Together, these activities aimed to provide Cofánindividuals <strong>and</strong> entities with the legal knowledge <strong>and</strong> negotiating skills necessary to more effectively interactwith external actors <strong>and</strong> defend their rights.Prominent Outcomes: According to respondents, the key outcome yielded by these interventions was anincreased capacity to not only interact, but also to successfully negotiate with a wide range of actors:indigenous communities, ministries, colonists, <strong>and</strong> private companies. For example, Cofán forest guards areled by a paralegal. The paralegal’s ability to competently discuss legal rights gives weight to discussionsundertaken with colonists found encroaching on Cofán territory. In addition, respondents in the Cofáncommunities credited the awareness raising <strong>and</strong> training interventions with “waking them up” to a clearerunderst<strong>and</strong>ing of ancestral rights <strong>and</strong> mechanisms to defend their territory. Thus, the legal <strong>and</strong> policy dialogueactivities of the project are seen to contribute to reaching mid-level outcome Effectively interacting with externalactors regarding territorial rights (MO-1). Although this intervention yielded positive results, numerousrespondents pointed to the lack of paid positions for newly trained paralegals. That is, once trained, there isvery limited opportunity for paralegals to apply this knowledge.4.2.2 LTPR Intervention 2: Community <strong>L<strong>and</strong></strong> TitlingDescription of Intervention: Collective titling of ancestral l<strong>and</strong>s was one of the major activities of theCAIMAN project. However, the large majority of Cofán territory falls within Ecuador’s protected areassystem <strong>and</strong> certain Cofán communities outside those protected areas were titled decades ago. Thus, the onlycollective titling undertaken by the project in Cofán territory was initiating a dialogue regarding the Area RioCofánes in La Bonita in the province of Sofia. 3 Accordingly, interview questions related to CAIMAN titlingwere more generalized, as opposed to specific activities undertaken in the Cofán territory.Outcomes: Respondents indicated that outcomes from CAIMAN’s l<strong>and</strong> titling intervention yielded: (a) anenhanced perception around indigenous communities’ legal rights; (b) decreased conflict with neighbors; (c)an enhanced feeling of tenure security; <strong>and</strong> (d) decreased encroachment. The acknowledgement of ancestralrights represented by a legal title to l<strong>and</strong> appears to provide both practical <strong>and</strong> social benefits to Cofáncommunities. These responses support two of the project’s higher-level outcomes: Indigenous groups withadequate legal rights (HO-1) <strong>and</strong> territorial rights of indigenous communities respected (HO-2).Additionally, there were two unexpected outcomes of titling cited by respondents: pride in l<strong>and</strong> ownership<strong>and</strong> changes in l<strong>and</strong> use. While only part of a long-term process of change in Ecuadorian politics <strong>and</strong> socialdevelopment, legal l<strong>and</strong> title is instrumental in providing indigenous communities with an official basis on3After project completion (2007), 30,000 hectares of the Area Rio Cofánes in Sofia was titled by ministerial decree.14 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT

which to interact with society. Legal title also gives communities a sense of security in knowing that theycannot be arbitrarily removed from their l<strong>and</strong>; this security may end up contributing to longer-termsustainable resource use <strong>and</strong> management strategies.4.2.3 LTPR Intervention 3: Conflict Mitigation/ResolutionDescription of Intervention: Resolution of conflicts between indigenous communities <strong>and</strong> theirsurrounding neighbors (colonists <strong>and</strong> other indigenous groups) were a primary focus of CAIMAN. Evenwhen indigenous communities have secured titles, conflicts still arise between actors. In order to enableresolution of conflicts, especially over boundary delimitation/demarcation or rights to specific naturalresources, workshops <strong>and</strong> meetings were facilitated by the project. Results of this intervention often resultedin the signing of good neighborliness agreements or paving the way toward titling. For example, conflictresolution in the Duvuno community led to the Kichwa-14 agreement.Outcomes: Typical responses demonstrated that conflict resolution was important to: (a) lowering theoverall level of conflict; (b) reaching agreements with neighbors; <strong>and</strong> (c) obtaining respect for territorial limits.The majority of outcomes articulated by respondents (agreements, demarcation, <strong>and</strong> conflicts reduced) referto output level outcomes as opposed to impact level outcomes. The responses did provide moderate evidenceof conflict resolution contributing to the high-level outcome, Territorial rights of indigenous communities respected(HO-2). However, contrary to project expectations that improved respect of territorial borders wouldcontribute to indigenous groups with adequate legal rights (HO-1), this link was not born out by the responses.Based on this picture, it appears that informants do not associate conflict mitigation with yielding formalizedtenure. This may be because titling was not a prominent activity within Cofán territory under CAIMAN, <strong>and</strong>such support was needed to fuel the linkage. Alternatively, while external stakeholders pointed to existingconflicts with colonists <strong>and</strong> other indigenous communities as a key issue confronting the Cofán, the objectiveof their resolution appears not to be titling.4.2.4 LTPR Intervention 4: Co-management AgreementsDescription of Intervention: In order to strengthen indigenous communities’ legal rights within protectedareas, CAIMAN helped establish co-management agreements between the MOE <strong>and</strong> indigenousorganizations. These agreements demonstrate state recognition of indigenous rights to l<strong>and</strong> within theprotected area system. They also place obligations on indigenous groups to abide by specific regulations thatgovern use of natural resources. In the Cofán territory, CAIMAN facilitated co-management agreements for7,500 <strong>and</strong> 22,538 hectares within the Cuyabeno Wildlife Production Reserve <strong>and</strong> Cayambe-Coca EcologicalReserve respectively. In 2002, prior to CAIMAN, the Cofán had obtained a similar but legally weaker coadministrationagreement for 50,000 hectares within Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve.Outcomes: Respondents indicate that co-management agreements have fallen short in: (i) providing securelegal status; (ii) fostering a sense of tenure security, <strong>and</strong> (iii) advancing sustainable use of natural resources.On the first two points, the Cofán perceive that they are legally vulnerable with co-management agreements<strong>and</strong> see them only as a step toward obtaining collective title. On the latter point, in most cases NRMrequirements contained within co-management agreements are not implemented by indigenous communities,nor are they adequately monitored or enforced by government agencies.Given the above, the CAIMAN’s support for co-management agreements had a limited effect on theexpected high-level outcome of Honoring of legal obligations by indigenous people (HO-3). Since no respondentsassociated the agreements with increased Respect for territorial rights of indigenous groups (HO-2), there wouldappear to be limited impact on this expected outcome. But it may also be that, between the Cofán <strong>and</strong> theirsupporters, the quest for titles overwhelmed their ability to find merit in co-management agreements.INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT 15

4.2.5 LTPR Intervention 5: Delimiting <strong>and</strong> Demarcating BoundariesDescription of Intervention: The enforcement of territorial rights is difficult to execute without physicalindicators of boundaries. These help internal <strong>and</strong> external actors underst<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> comply with territorialboundaries. Clearing l<strong>and</strong> <strong>and</strong> placing signs that visibly demarcate the limits of each community’s territorywas an important intervention within the CAIMAN project. Trained community members, including parkguards, participated in delimitation <strong>and</strong> demarcation activities. Across Cofán territory, a total 248 kilometersof boundaries were demarcated.Outcomes: Within the project, this intervention aimed to support the following high-level outcomes:Indigenous groups with adequate legal rights (HO-1) <strong>and</strong> Territorial rights of indigenous communities respected (HO-2).Respondent opinions, however, were clearly focused on the latter. Many of those interviewed indicated thatthis intervention contributed to: (a) greater respect for territory; (b) improved security; (c) resolution ofdifficult issues; <strong>and</strong> (d) establishment of boundaries. In some cases, the clearing <strong>and</strong> marking of territorialboundary required the resolution of, sometimes decades-old, conflicts with neighboring communities(colonists or indigenous communities). It also allowed for reconciliation between legal boundaries <strong>and</strong> sociallyrecognized boundaries, contributing to the prevention of further conflicts.While not meriting the category of unexpected outcome, it is noteworthy that one respondent crediteddemarcation <strong>and</strong> delimitation for enabling park guards to work in a more informed manner. Thus, at least oneinformant identified the synergy between this intervention <strong>and</strong> other border enforcement activities.4.2.6 LTPR Intervention 6: Patrolling BordersDescription of Intervention: Border patrolling is a visible mechanism for the defense of property rights <strong>and</strong>the enforcement of rule of law. Fundación Cofán <strong>and</strong> CAIMAN collaborated in creating the Cofán ForestGuard Program. Approximately 60 border guards (including women) received training on topics such as firstaid, global positioning systems use, conflict resolution, <strong>and</strong> biological monitoring. In addition to protectingterritory <strong>and</strong> demarcating <strong>and</strong> maintaining boundaries, park guards also collect data on the biological health ofthe flora <strong>and</strong> fauna within their boundaries (See Annex G, Figures G-1 <strong>and</strong> G-2 for park guard monitoringsheets). The guards are broken into two groups: (i) park guards monitor areas within the protected areasystem <strong>and</strong> possess the same rights as MOE guards; <strong>and</strong> (ii) forest guards monitor titled communities such asDuvuno <strong>and</strong> Dureno. Operationally speaking, the guards organize into roving patrols <strong>and</strong> staff rangerstations.Outcomes: Responses gleaned on this intervention demonstrate a strong linkage to attaining expected midleveloutcomes: Borders of indigenous territories respected (MO-3) <strong>and</strong> agreed property rights enforced at the local level (MO-4). Likewise, respondents point to an important tie between this intervention <strong>and</strong> the expected high-leveloutcome, Territorial rights of indigenous people respected (HO-2). The conservation of natural resources was alsoidentified as an outcome of the border patrol program. According to respondents, this is occurring throughthree means: (i) guards protecting natural resources within Cofán territory; (ii) guards earning a consistentincome that reduces pressure on the environment (i.e., usingl<strong>and</strong>/resources to fulfill basic needs); <strong>and</strong> (iii) enhanced feelings ofresponsibility toward the environment on the part of youngCofáns participating in the guard program. Thus, the guardprogram was also seen as contributing to the attainment of thestrategic-level objective Biodiversity conservation (SO1).Additional important outcomes of border patrolling activitiescited included the generation of leadership skills <strong>and</strong> employmentfor (mainly young) community members. Several other interesting“I am happy <strong>and</strong> content that Ihave this work <strong>and</strong> that I amconserving the forest. Before, Inever had these types of ideasabout preserving animals <strong>and</strong>territories like this. ”–Cofán park guard16 INDIGENOUS TERRITORIAL RIGHTS IN <strong>ECUADOR</strong>: RAPID IMPACT ASSESSMENT