Engendering Justice - from Policy to Practice - The Fawcett Society

Engendering Justice - from Policy to Practice - The Fawcett Society

Engendering Justice - from Policy to Practice - The Fawcett Society

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Engendering</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>– <strong>from</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>Final report of the Commission on Womenand the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> SystemMay 2009

We are grateful <strong>to</strong> our funders, the LankellyChase Foundation and the Barrow Cadbury Trust, for their generous support.We are also very grateful <strong>to</strong> all those who have contributed <strong>to</strong> this report, in particular the many women and organisationswho gave up their valuable time <strong>to</strong> share their experiences of the criminal justice system with us. We would like<strong>to</strong> especially thank the British Association for Women in Policing, the Magistrates’ Association, UK Association ofWomen Judges, Women and Young People’s Team (NOMS) and the Governors of the female prison estates fortheir help in putting us in <strong>to</strong>uch with women with direct experience of the criminal justice system. Thank you also <strong>to</strong>the Government departments, criminal justice agencies and organisations (outlined in Chapter One) who attendedCommission evidence sessions and <strong>to</strong> the staff and volunteers at the <strong>Fawcett</strong> <strong>Society</strong> who contributed <strong>to</strong> this project.Report compiled by Sharon Smee, <strong>Justice</strong> <strong>Policy</strong> Officer at the <strong>Fawcett</strong> <strong>Society</strong>.Page 2

ContentsForeword 5Executive Summary 7Chapter One: Methodology and an Overview of the Work of the Commission 13Chapter Two: Introduction: From <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Practice</strong> 18Part One:Women Need <strong>Justice</strong> and <strong>Justice</strong> Needs WomenChapter Three: Women and <strong>Justice</strong> – Meeting the Needs of Women Offenders 20Chapter Four: Women Need <strong>Justice</strong> – Female victims of Crime 45Chapter Five: <strong>Justice</strong> Needs Women – Women Workers in the System 66Part Two:<strong>Engendering</strong> <strong>Justice</strong>: Roadmap for Reform 80A Vision for a Gender Responsive Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> SystemAppendix A <strong>The</strong> Commissioners 99Appendix B Recommendations of the Commission 101Page 3

List of AcronymsACPOAssociation of Chief Police OfficersSDVCSpecialist Domestic Violence CourtsBMEBlack- Minority EthnicSOITSexual Offences Investigative Technique [officer]BAWPBritish Association for Women in PolicingSRASolici<strong>to</strong>rs Regulation AuthorityCEDAW Convention for the Elimination of All Forms ofDiscrimination Against WomenCICACJLDCriminal Injuries Compensation AuthorityCriminal <strong>Justice</strong> Liaison and Diversion [schemes]TWPVAWWAVETogether Women ProgrammeViolence against WomenWitness and Victim Evaluation SurveyCPSDVEHRCGEDGSSHMPSIDVAIPCCISVACrown Prosecution ServiceDomestic ViolenceEquality and Human Rights CommissionGender Equality DutyGender Specific StandardsHer Majesty’s Prison ServiceIndependent Domestic Violence AdviserIndependent Police Complaints CommissionIndependent Sexual Violence AdviserMARAC Multi-Agency Risk Assessment ConferencesNHSNOMSQCRCCSARCNational Health ServiceNational Offender Management ServiceQueen’s CounselRape Crisis CentreSexual Assault Referral CentrePage 4

ForewordFor the past five years, <strong>Fawcett</strong>’s Commission on Women and the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> System has examined theexperiences of women as victims, offenders and workers in the criminal justice system. This unique Commissionhas published four reports and has achieved a number of key legislative, organisational and policy changes.Since its inception, the Commission’s work has benefited <strong>from</strong> the considerable and diverse expertise of itsCommissioners, drawn <strong>from</strong> across the criminal justice system and areas of public life. Vera Baird MP QCexpertly chaired the Commission until 2006 when she stepped down following her appointment as a minister inthe Department of Constitutional Affairs. I have been privileged <strong>to</strong> Chair this Commission since that time.This final report is an in-depth examination of the experiences of women in the criminal justice systemand incorporates testimony of women themselves <strong>to</strong> give voice <strong>to</strong> the diverse experiences of individuals.One of the key emerging themes is the persisting gap between strong policy development and consistentimplementation. This report contains detailed recommendations which address each stage of thecriminal justice process and which aim <strong>to</strong> close the widening gap between policy and practice.<strong>The</strong> Commission welcomes the Government’s work over the past five years <strong>to</strong>wards ensuring that thecriminal justice system meets the needs of women but the pace of change has been disappointingly slow.<strong>The</strong>re remains much work <strong>to</strong> be done. Part Two of this final report sets out the Commission’s vision of ajustice system which recognises and responds <strong>to</strong> the unique needs, experiences and skills of women and theinstitutional change which is needed <strong>to</strong> achieve this. It is up <strong>to</strong> each of us <strong>to</strong> work <strong>to</strong>wards this goal.Baroness Jean Cors<strong>to</strong>n,Chair, Commission on Women and the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> SystemPage 5

List of Commissioners 2008-2009Baroness Jean Cors<strong>to</strong>n (Chair)Labour PartyColin Allen,Former Governor of Holloway Prison and Former PrisonsInspec<strong>to</strong>rLiz Bavidge OBEMagistrateRuth BundeySolici<strong>to</strong>r, Harrison Bundey Solici<strong>to</strong>rsMr <strong>Justice</strong> Calvert-SmithHigh Court JudgeMalcolm DeanFormer assistant edi<strong>to</strong>r, the GuardianLord Navnit Dholakia OBE DLLiberal DemocratsDeputy Assist. Commissioner Cressida Dick,Metropolitan Police ServiceMrs <strong>Justice</strong> Linda Dobbs DBEHigh Court JudgeMitch Egan CBNOMS advisor and former North East Regional OffenderManagerProfessor Liz Kelly CBERoddick Chair in Violence against Womenat London Metropolitan UniversityCommissioner, Women’s National CommissionKaron Monaghan QCBarrister, Matrix ChambersBaroness Gillian ShephardConservative PartyPage 6

Executive SummarySince 2003, <strong>Fawcett</strong>’s Commission on Women and theCriminal <strong>Justice</strong> System has examined the experiences ofwomen in the criminal justice system as victims, offendersand workers. This approach has allowed us <strong>to</strong> drawparallels across the system, demonstrating that womencontinue <strong>to</strong> be marginalised in a criminal justice system,designed by men for men. Despite improved policydevelopments since the inception of the Commission,institutional sexism remains deeply embedded in practicesand attitudes <strong>to</strong>wards women in the criminal justice system.A Gender-responsive Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> SystemOur vision is for a society in which:• <strong>The</strong> criminal justice system provides women withsupport, safety and justice.• <strong>The</strong> sentencing of non-violent female offenders isresponsive <strong>to</strong> the needs of these women and theirfamilies.• Women working in the criminal justice system arefree <strong>from</strong> discrimination and harassment with equalopportunities <strong>to</strong> progress at all levels of the variouscriminal justice agencies.• <strong>Policy</strong> and practice of all criminal justice agencies isinformed by gender analysis so as <strong>to</strong> meet the diverseneeds of both men and women.• <strong>The</strong> Judiciary and the senior levels of the legal profession,the police, the CPS, the prison service and the probationservice are broadly representative of a society with abalance of women and men and recognition of the skillsand experiences of women.• <strong>Society</strong> recognises that all women have the right <strong>to</strong> livetheir lives free <strong>from</strong> the threat and reality of violence.Acknowledgement and Understanding of InstitutionalSexismInstitutional racism became a familiar term following theStephen Lawrence inquiry but institutional sexism is rarelyopenly acknowledged. <strong>The</strong> experiences of women withinthe criminal justice system provide countless examples ofinstitutional sexism in practice through processes, attitudes,and behaviour which amount <strong>to</strong> discrimination whichdisadvantages women.<strong>The</strong> criminal justice system remains largely definedby male standards:• Flexible and part-time working is not consistentlyaccepted and the culture of long working hoursdisadvantages any individual with caring responsibilities,the majority of whom are women.• Promotion and ability <strong>to</strong> perform a job are frequentlyjudged against male standards rather than thecompetencies of the job, such as fitness tests in thepolice force focusing on upper body strength, rather thanthe actual requirements of the role.• Attitudes and expectations as <strong>to</strong> how a ‘proper victim’should behave continue <strong>to</strong> shape the criminal justicesystem response <strong>to</strong> violence against women. A 2009Home office survey revealed one in four respondentsbelieve that a woman is partially responsible if she israped or sexually assaulted when she is drunk and onethird thought she would be partially responsible if sheflirted heavily with the man beforehand.I feel if I don’t partake in sexual banter I get left out and amnot one of “the boys.”Female Prison OfficerWomen who are carers experience disadvantagethroughout the criminal justice system:• Women victims without access <strong>to</strong> support <strong>from</strong> family andfriends <strong>to</strong> look after their children often have <strong>to</strong> bring theirchildren <strong>to</strong> court. Yet courts have no facilities <strong>to</strong> assistmothers in this position.• It is estimated that up <strong>to</strong> 17,700 children each year areseparated <strong>from</strong> their mothers due <strong>to</strong> imprisonment andat least a third of women offenders with children are loneparents. Women are often not prepared for sentencingoutcomes by their lawyers and may be placed in cus<strong>to</strong>dywithout the opportunity <strong>to</strong> arrange for the care of theirchildren.• For women in cus<strong>to</strong>dy, maintaining contact is veryimportant yet the location of female prisons meansfamilies are often unable <strong>to</strong> visit and call costs are higherthan standard rates.• Women workers with children face disadvantage in thePage 7

Executive Summary continuedway workplaces are organised such as on-call work andshift work and training and development programmes far<strong>from</strong> home.Double disadvantage on the basis of both race andsex• Ethnic minority women and foreign national women areoverrepresented within the female offender populationand are more likely <strong>to</strong> feel isolated in cus<strong>to</strong>dy, less likely<strong>to</strong> seek help and face additional language and culturalbarriers.• Foreign national women, who make up nearly one in fiveof the female prison population, are particularly isolated<strong>from</strong> their children and are currently only provided withfree phone use for five minutes per month <strong>to</strong> speak <strong>to</strong>their family.• Understanding of the needs of ethnic minority womenwho experience violence and appropriate support islacking. Only one in ten of all local authorities have aspecialised service for BME women.• Ethnic minority women are under-represented amongworkers in the criminal justice system. For example, thereis only one ethnic minority woman in the senior judiciary.One size does not fit all• A misunderstanding of equality as requiring sametreatment for men and women has led <strong>to</strong> male-definedpractices and programmes being applied <strong>to</strong> women.• <strong>The</strong> high levels of self-harm within the female prisonestate are one manifestation of the effects on womenof a prison estate which is designed for male prisoners.Self-harm among women in cus<strong>to</strong>dy has increased by48 percent between 2003 and 2007 and women commitaround 50 percent of self-harm incidents although theyrepresent only 5 percent of the <strong>to</strong>tal prison population.• Despite the different needs of women (such as womenonlyaccommodation for women who have experiencedviolence and abuse), there have been instances wherelocal authorities have stipulated that support services,such as refuges, must provide <strong>to</strong> men on a parity withwomen.Squeezing Women in<strong>to</strong> the Male Mould – <strong>The</strong> PoliceUniform<strong>The</strong> police force uniform provides a clear example ofattempts <strong>to</strong> make female workers fit the male mould. Insome police forces, the current uniform is based upona 1950s military uniform and the same male-designeduniform is issued for both men and women. Shirts aredesigned for men and are ordered by collar size andstab vests have no shaping for women. <strong>The</strong>re is littleunderstanding that women come in different shapesand sizes <strong>to</strong> men and therefore need clothing tailored <strong>to</strong>meet their body form, resulting in a very impractical anduncomfortable uniform for women officers in these forces.Key Findings:This final report of the Commission reveals a persistinggap between strong policy development and consistentimplementation. Evidence has demonstrated thatthroughout the criminal justice system, practices andattitudes continue <strong>to</strong> discriminate against women.As a consequence the criminal justice system:• Does not address the causes of women’s offendingwith the result that <strong>to</strong>o many women continue <strong>to</strong> beimprisoned on short sentences for non-violent crime;• Fails <strong>to</strong> provide female victims of violence with support,safety and justice; and• Creates a glass ceiling for women working within thesystem so that higher positions across the sec<strong>to</strong>r remainmale dominated.<strong>The</strong> Gap between <strong>Policy</strong> and <strong>Practice</strong>When the gender equality duty came in<strong>to</strong> force it washoped that it would result in all organisations providing apublic service proactively addressing discrimination andpromoting gender equality. However, results <strong>to</strong> date havebeen disappointing and highlight the slow translation ofpolicy in<strong>to</strong> practice.Page 8

Executive Summary continuedon domestic violence, rape and sexual offences as wellas its Violence against Women Strategy and Action Plans.<strong>The</strong> Commission is also encouraged by the current workof the Home Office in leading on a long over-due Cross-Government Strategy on VAW. However, good policydevelopment will not have impact on the ground, unlessresources and targets are directed <strong>to</strong>wards creating a shiftin attitudes and culture.<strong>The</strong> Commission has identified five key areasrequiring urgent attention:• A cross-government integrated and strategic approach<strong>to</strong> ending violence against women. <strong>The</strong> new Violenceagainst Women Strategy will only succeed if there is realcross-government commitment and an understandingthat violence against women is a relevant issue for everydepartment.• Violence against women should be treated with the sameprofessionalism as other crimes with consistency in initialresponses <strong>to</strong> victims and investigation across policeareas.• A uniform approach <strong>to</strong> communication with victims by thepolice during investigation and by the CPS, particularlyat the point in time when the decision is made not <strong>to</strong>proceed with the prosecution of a case.• Support for women who experience violence shouldnot depend on a woman’s postcode. Currently, thereis patchy provision of violence against women servicesacross England and Wales, particularly in rural areas,and the provision of special measures, interpretationand support for women during the court process isinconsistent.• <strong>The</strong> attitudes <strong>to</strong>wards violence against women,particularly in relation <strong>to</strong> rape and sexual offences,exhibited by the police, prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs, judges, juries andthe general public.Women WorkersWhile there is growing acknowledgement that femalevictims and female offenders require a justice system thatis responsive <strong>to</strong> their needs there is less recognition thatjustice needs women. However, a greater representationof women, particularly in high level positions, is crucial <strong>to</strong>create a criminal justice system which is representative ofour diverse society; responsive <strong>to</strong> the needs of women; andreflective of unique perspectives <strong>to</strong> issues.I think it is important for women <strong>to</strong> be seen in all areas ofthe criminal justice system. Until this is true the systemis not reflective of society. I do not believe that there is adifference in the administration of justice because there arewomen doing the job but that is an argument for women<strong>to</strong> do the job not <strong>to</strong> the contrary.Female JudgeWhether gender balance can be achieved, particularlyin senior levels, will depend on how responsive careerprogression and grading practices are <strong>to</strong> the needs ofwomen and how workplaces adapt <strong>to</strong> utilise the skillsand experiences of women. Adopting a gender neutralapproach, which ensures the ‘playing field remains thesame’ is not the solution. Rather, the participation ofwomen should be unders<strong>to</strong>od as a route <strong>to</strong> challengingmale dominance.<strong>The</strong>re have been policy developments across thecriminal justice system in an attempt <strong>to</strong> increase therepresentativeness of the justice sec<strong>to</strong>r, such as theintroduction of the Judicial Appointments Commissionand changes <strong>to</strong> the Queen’s Counsel Selection Process.Policies in relation <strong>to</strong> flexible working, equal opportunitiesand diversity have also been introduced across the criminaljustice agencies. However, although women are makinginroads at lower levels, the higher positions remain stronglymale dominated.I felt that I had <strong>to</strong> defend my actions rather than him having<strong>to</strong> defend his. I often felt like the perpetra<strong>to</strong>r and not thevictim.Female victim of RapePage 10

<strong>The</strong> Commission has identified five key areasrequiring urgent attention:• Women’s caring responsibilities continue <strong>to</strong> operate asa disadvantage in career progression (with promotion ortraining requirements often requiring travel or long hours)and in coping with shift or on-call work.• When flexible working and part-time workingarrangements are in place, they are not appliedconsistently and rely on the interpretation of local linemanagement. <strong>The</strong>re is also a lack of understanding thatflexible working can benefit all staff.• Women continue <strong>to</strong> earn less than their malecounterparts, particularly within the legal profession.• <strong>The</strong> diversity of individuals applying for the judiciary andfor Queen’s Counsel remains worryingly low. <strong>The</strong> numberof female applicants for QC in 2008 was at its lowest levelfor ten years.• A male dominated culture continues <strong>to</strong> exist across thecriminal justice system with women constantly having <strong>to</strong>prove themselves against male-defined standards such aslong working hours.Women working in the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> SystemIn 2008, only 12 percent of police officers at ChiefInspec<strong>to</strong>r grade and above were female.Only 15.9 percent of partners in the UK’s ten largest lawfirms were women in 2008.At the <strong>to</strong>p 30 sets of the UK bar, there are only 42 femalecompared <strong>to</strong> 479 male silks.In 2008, less than a quarter of the prison governors arefemale and fewer than one in four prison officers arewomen.Key Recommendations – Women Need <strong>Justice</strong> and<strong>Justice</strong> Needs Women<strong>The</strong> Commission welcomes the Government’s work overthe past five years <strong>to</strong>wards ensuring that the criminal justicesystem meets the needs of women but the pace of changehas been disappointingly slow. This in-depth examinationof the experiences of women in the criminal justice systemhas resulted in recommendations which address each stageof the criminal justice process. <strong>The</strong>se recommendations canbe found at Appendix B.Key over-arching recommendations include:Female Victims of Crime• A Cross-Government Strategy on VAW must beimplemented with real commitment <strong>from</strong> all Governmentdepartments.• <strong>The</strong> Government should fund a national awarenessraising campaign on rape and sexual violence, similar <strong>to</strong>awareness raising campaigns in relation <strong>to</strong> drink driving.• Specific training aimed at frontline staff within the policeand the CPS <strong>to</strong> change attitudes <strong>to</strong>wards rape, andimprove initial responses <strong>to</strong> women and early evidencecollection must be rolled out across the country.• Joint targets for the CPS and the police should bedeveloped <strong>to</strong> incentivise them <strong>to</strong> work <strong>to</strong>gether anddevelop a national strategy <strong>to</strong>wards rape and otherserious sexual violence offences.• A Government commitment <strong>to</strong> long term funding forviolence against women service provision, including anational network of rape crisis centres and a 24 hourhelpline.In 2008, just over 10 percent of the 109 High CourtJudges were women and just over 8 percent of the 37Court of Appeal Judges were female. <strong>The</strong>re is only onefemale Law Lord.Page 11

Executive Summary continuedFemale Offenders• Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> Liaison and Diversion Schemes shouldbe adequately resourced <strong>to</strong> work in partnership with thepolice and courts <strong>to</strong> divert offenders with mental healthneeds away <strong>from</strong> the criminal justice system.• Adequate and robust alternatives <strong>to</strong> remand must bemade available <strong>to</strong> the judiciary, such as adequate singlesexbail hostel provision (for women and their children),intensive supervision and electronic surveillance.• Comprehensive pre-sentence reports which analysethe harms likely <strong>to</strong> result <strong>from</strong> incarceration shouldbe prepared for each female offender, including anassessment of the impact of incarceration on anydependents.• Prison staff should be provided with training in relation <strong>to</strong>mental health needs of offenders and the needs of femalevictims of violence, including screening, risk assessment,safety planning and referral <strong>to</strong> specialist services.• Long term funding for community provision and thedevelopment of a national network of gender specificcommunity provision with accommodation facilities forwomen and their children.service and prison service should be introduced <strong>to</strong> allowemployees <strong>to</strong> appeal decisions in relation <strong>to</strong> flexibleworking beyond local managers.• Methods for promotion and locations for prerequisitetraining should take in<strong>to</strong> account caring commitments ofstaff as well as any disadvantage for part-time or flexibleworkers in assessment methods chosen.• Part-time working and a programme of equalityand diversity should be made available <strong>to</strong> all levelsof the judiciary.Creating a criminal justice system which is fair for womenrequires consistent and focused hard work on the part ofcriminal justice agencies and organisations. Importantlythere can be no real change until there is a shift in themindset of those working within all levels of Governmentand the criminal justice system that equality does notrequire that women be treated the same as men but ratherthat women should be treated appropriately according <strong>to</strong>their needs.• <strong>The</strong> development of small cus<strong>to</strong>dial units in each countyarea <strong>to</strong> aid the transition <strong>to</strong> community alternatives <strong>to</strong>cus<strong>to</strong>dy and <strong>to</strong> be eventually integrated in<strong>to</strong> the nationalnetwork of community provision.Women Workers• Extensive research in<strong>to</strong> sexual harassment anddiscrimina<strong>to</strong>ry practices, including pregnancydiscrimination, in the police, probation service, prisonservice and legal profession should be undertaken bythe EHRC in partnership with the relevant authority /inspec<strong>to</strong>rate and the results widely publicised.• An explanation of the benefits of part-time workingand flexible work practices and the availability of theseinitiatives for male and female employees should bewidely promoted.• An appeal system within the police, CPS, probationPage 12

Chapter One:Methodology and an Overview of the Work of the CommissionI truly welcome the work of the <strong>Fawcett</strong>’s Commission onWomen and the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> System in uncovering thetreatment of women. <strong>Fawcett</strong>’s annual reviews have led<strong>to</strong> real reform of the system and I welcome the continuedpressure for change.(Charles Clarke, then Home Secretary, launch of <strong>Justice</strong>and Equality, 2005)Remit and Scope ofthe Commission<strong>Fawcett</strong>’s Commission on Women and the Criminal<strong>Justice</strong> began its work in 2003 with a one year inquiryin<strong>to</strong> the experiences of adult women in England andWales. Since that time the Commission has publishedthree annual reviews which have continued <strong>to</strong> highlightwomen’s experiences of the criminal justice system.Our remit has not extended <strong>to</strong> Scotland, due <strong>to</strong> the differentnature of the criminal justice system. However, we havedrawn on examples of good practice <strong>from</strong> Scotland <strong>to</strong>inform our work. Time and resources also dictated thatthe Commission’s work has been limited <strong>to</strong> adult womenand has not considered, in detail, the specific needsof girls and young women offenders or the families ofwomen offenders and/or victims. We acknowledge theimportance of these issues and commend the specificresearch that has been conducted by other bodies.<strong>The</strong> Commission has published fourreports since its inception in 2003:• Women and <strong>Justice</strong> (2007)• <strong>Justice</strong> and Equality (2006)• One Year On (2005)• Commission on Women and the Criminal<strong>Justice</strong> System Report (2004)Each of these reports has examined issues forwomen as victims, offenders and workers andhas made a series of recommendations aiming <strong>to</strong>create a better and more equitable way of dealingwith women in the criminal justice system.Evidence CollectionSince its inception, the Commission’s work has benefited<strong>from</strong> the considerable and diverse expertise of itsCommissioners, drawn <strong>from</strong> across the criminal justicesystem and areas of public life. A full list of Commissioners,current and previous, is at Appendix A. Since 2007, theCommission has been chaired by Baroness Jean Cors<strong>to</strong>n,author of the Cors<strong>to</strong>n Report - a review of women withparticular vulnerabilities in the criminal justice system.During 2008-09, we held three evidence sessions.Significantly, government departments, voluntary sec<strong>to</strong>rorganisations and criminal justice agencies were all veryreceptive <strong>to</strong> the work of the Commission and all invitations<strong>to</strong> attend <strong>to</strong> give evidence were accepted without exception.<strong>The</strong> first evidence session, focused on female offenders,and was attended by high level representatives <strong>from</strong> theSentencing Advisory Panel, Women and Young People’sTeam of the National Offender Management Service;the Women and Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> Strategy Unit of theMinistry of <strong>Justice</strong>; and the Offender Health strand ofthe Department of Health. <strong>The</strong> first part of the secondmeeting concentrated on women as victims and theCommission had the opportunity <strong>to</strong> meet with <strong>The</strong> ViolentCrime Unit within the Home Office; Rape Crisis (England& Wales); the Crown Prosecution Service (leads onViolence against Women and Rape); and the Associationof Chief Police Officers (ACPO). <strong>The</strong> second segmentprovided us with an opportunity <strong>to</strong> focus on women asworkers in the criminal justice system with the Chair ofthe Judicial Appointments Commission and the NationalCoordina<strong>to</strong>r of the British Association for Women in Policing<strong>to</strong>gether with Janet Astley, a researcher in the area ofwomen and policing, meeting with the Commission.<strong>The</strong> third evidence session focused on creating aCommission-led vision of a criminal justice system which isfair for women and the key reforms needed over the nextfive <strong>to</strong> ten years <strong>to</strong> create this more gender-responsivecriminal justice system. Vera Baird QC MP, Solici<strong>to</strong>r General,provided evidence <strong>to</strong> the Commission. This was followedby a roundtable lunch event at which approximatelytwenty organisations who work on issues relevant <strong>to</strong>women and the criminal justice system shared their viewswith the Commission on a ‘wish-list’ for future reform.Page 13

Chapter One: Continued.Methodology and an Overview of the Work of the CommissionWe are especially grateful <strong>to</strong> the women’s associationsand membership associations within the variouscriminal justice agencies as well as organisationswithin the voluntary sec<strong>to</strong>r who facilitated thisprocess and the numerous individuals who gaveup their time <strong>to</strong> share their views with us. <strong>The</strong>rewas an overwhelming response <strong>to</strong> our work withover 500 questionnaire responses received.<strong>The</strong> evidence gathered by the Commission wasprimarily qualitative and the survey responses <strong>from</strong>offenders, victims, specialised agencies and workersin the criminal justice system have not been codedfor statistical analysis. Content analysis is focusedon broad themes and recurring concerns which areaddressed throughout the report. <strong>The</strong> focus in the texthas been on giving voice <strong>to</strong> the diverse experiencesof individual women. <strong>The</strong> emphasis is on “buildingknowledge <strong>from</strong> women’s lives – a commitment that,feminists believe, has wider implications that have thepotential <strong>to</strong> transform existing knowledge frameworks.” 1<strong>The</strong> Commission Model – a meansfor achieving real change<strong>The</strong>se evidence sessions provided the Commission witha valuable opportunity <strong>to</strong> hear first-hand informationand <strong>to</strong> follow up issues which were of particularconcern <strong>to</strong> Commissioners. We would like <strong>to</strong> thankall attendees who gave up their valuable time <strong>to</strong>share their experiences and expertise with us.Vera Baird QC MP, Solici<strong>to</strong>r General and BaronessJean Cors<strong>to</strong>n (Chair) at a meeting of the Commission on4 March 2009A key aim of this final report was <strong>to</strong> incorporate the voicesof women who have experienced the criminal justice systemas women accused or convicted of criminal offences;female victims of crime; women working within the variouscriminal justice agencies; and organisations working withfemale victims of crime and/or female offenders. Specificallydesigned questionnaires were distributed within theprison service, the police force, the legal profession, thejudiciary, the magistracy, the Crown Prosecution Serviceand the Probation Service as well as <strong>to</strong> organisations andindividual women via the internet and various networks.This is the final phase of our work. <strong>The</strong> use of aCommission model has proven particularly effective asit has enabled the work <strong>to</strong> go beyond a ‘one-off’ reportand we have not been confined in relation <strong>to</strong> the breadthof issues which we could explore. <strong>The</strong> five year durationof the Commission has allowed extensive follow-upwork <strong>to</strong> be carried out in order <strong>to</strong> track progress onrecommendations by the criminal justice agencies.Through authoritative research, high level lobbyingand media interventions, the Commission hasachieved a number of key changes.Successful lobbying for the introduction of a dutyon public bodies <strong>to</strong> promote gender equality:In its original report, the Commission recommendedthat legislation on gender should be brought in line withlegislation on race by introducing a positive duty on publicauthorities <strong>to</strong> have “due regard” <strong>to</strong> the need <strong>to</strong> eliminateunlawful sex discrimination and <strong>to</strong> promote genderequality. <strong>The</strong> gender equality duty was introduced in theEquality Act 2006, and came in<strong>to</strong> force in April 2007.Page 14

Commissioners listen <strong>to</strong> evidence <strong>from</strong> organisations working on issues relevant <strong>to</strong> women and the criminal justice system.Improved treatment of women offenders<strong>The</strong> Commission has led a change in the thinkingof politicians and policy makers about the need forwomen-specific community provision for womenoffenders, which has resulted in projects such as theTogether Women Programme (TWP). <strong>The</strong> Commissionwas also influential in making the link between femalevictims of violence and patterns of female offending.Improved provision for women victimsOur work has added <strong>to</strong> the exposure of the scandalof the ‘postcode lottery’ faced by women victims ofviolence. In the second annual review, the Commissionreleased figures that demonstrated the inconsistent rapeconviction rates between police areas ranging <strong>from</strong> 13.8percent in one police force area <strong>to</strong> 0.8 percent in another.We also called for an increase in the number of sexualassault referral centres and specialist domestic violencecourts and there has been progress in this regard.Better working lives for women withinthe criminal justice system<strong>The</strong> Commission influenced the decision <strong>to</strong> establishan independent Judicial Appointments Commission <strong>to</strong>increase diversity in the judiciary and has also exposedthe barriers <strong>to</strong> the participation of women amongthe senior levels of the judiciary, the legal profession,the police, the prison service and the CPS.We would like <strong>to</strong> thank the funders who have generouslysupported the work of the Commission at varioustimes over the previous five years: <strong>The</strong> LankellyChaseFoundation; <strong>The</strong> Barrow Cadbury Trust; <strong>The</strong> EsméeFairbairn Foundation; <strong>The</strong> 29th May 1961 CharitableTrust; <strong>The</strong> Noel Bux<strong>to</strong>n Trust; <strong>The</strong> Nuffield Foundation;<strong>The</strong> Home Office; Matrix Causes Fund and Garden CourtChambers. Without the generous support of these funders,the Commission’s work would not have been possible.Page 15

<strong>The</strong> Five Years of the CommissionComparative Statistics- <strong>The</strong> First and Final reports of the CommissionWe have endeavoured <strong>to</strong> collect comparable statistics <strong>from</strong> the time of the first Commission report (2003/ 2004) and themost currently available data but a direct comparison has not always been possible. <strong>The</strong>se statistics present a picture ofmixed progress over the last five years. <strong>The</strong>re have been marked improvements in some areas, no change in others andsome statistics suggest the situation has worsened. It should also be noted that a five year comparison often does notcapture the whole s<strong>to</strong>ry. For example, the women’s prison population has increased by 60 percent over the last decade.Female OffendersFirst Report19th March 2004 there were 4,584 women in prison.(In 1993, the female prison population was an average of 1,560)<strong>The</strong>re were 17 prisons that hold women and none in Wales.Final Report20th March 2009 there were 4,309 women and girls in prison.<strong>The</strong>re are 14 women only prisons in the U.K. and none in Wales212,500 women were arrested for notifiable offences. 251,500 women were arrested for notifiable offences (2007).34,100 females were cautioned. 55,700 females were cautioned (2007).11% of all sentences of women were community sentences. 10.6% of all sentences of women were community sentences(2007).12.4% of women in prison were serving sentences of less than orequal <strong>to</strong> six months.13.9%of women in prison were serving sentences of less than orequal <strong>to</strong> six months (2007).30% of women in prison self-harmed Around 50% of all self-harm incidents in prison are committed bywomen.376 self-harm incidents by women in HMP Styal 1,324 self-harm incidents by women in HMP StyalAround 17,000 children were affected by their mothers’ imprisonmenteach year.Of all the women in prison two thirds were on remand.More than 17,700 children are separated <strong>from</strong> their mother byimprisonment.One-fifth of the female prison population is on remand.20% of female prisoners were foreign nationals. 19% of female prisoners are foreign nationals.Crown Court (Sentencing)Immediate Cus<strong>to</strong>dy:Men, 41,165, Women, 3,109Community Sentences:Men, 19,715, Women 28,545Crown Court (Sentencing)Immediate Cus<strong>to</strong>dy:Men, 40,911, Women, 3,123Community Sentences:Men, 12,575, Women 30,617Magistrate Court (Sentencing)Immediate Cus<strong>to</strong>dy:Men, 57,695, Women, 5,701Community Sentences:Men, 143,421, Women, 25,166Magistrate Court (Sentencing)Immediate Cus<strong>to</strong>dy:Men, 46,500, Women, 4,672Community Sentences:Men, 153,229, Women, 28,37824 women received life imprisonment sentences. 21 women received life imprisonment sentences.Percentage sentenced <strong>to</strong> immediate cus<strong>to</strong>dy forindictable offences:Women- 15.2%Percentage sentenced <strong>to</strong> immediate cus<strong>to</strong>dy forindictable offences:Women- 14.6%Page 16

Female Victims of CrimeFirst ReportRapeFinal Report11,441 rapes against women. 11,648 recorded rapes against women.2.8% of women reported they had been a victim of sexual assault 3.1% of women reported they had been a victim of sexual assaultConviction rate for rape: 5.3% (of reported cases)Conviction rate for rape: 6.5% (of reported cases)Sexual offence sanction detection rate for rape of a female: 30% Sexual offence sanction detection rate for rape of a female: 25%14 Sexual Assault Referral Centres (SARCs). 22 SARCs in operation and more under development.Domestic Violence37% of victims retracted their cases. 21.2% of victims retracted their cases.<strong>The</strong>re were 2 pilots of Specialist Domestic Violence Courts inCroydon and CaerphillyDomestic Violence accounted for 18% of all reported violentcrimes.<strong>The</strong>re are 104 Specialist Domestic Violence Courts in Englandand Wales.Domestic Violence accounts for 16% of all reported violentcrimes.26% of women killed were killed by a current or ex- partner. 44% of women killed were killed by current or ex – partner.Conviction rate <strong>from</strong> domestic violence prosecutions stands at25% (of charged cases).Conviction rate <strong>from</strong> domestic violence prosecutions stands at72.5% (of charged cases).Women WorkersFirst ReportJudiciaryHigh Court Judges, 5.7% are femaleCircuit Judges, 9.4% are femaleDistrict Judges, 21.2% are femaleTotal, 14.9% are femaleFinal ReportHigh Court Judges 10% are femaleCircuit Judges 13.32% are femaleDistrict Judges 22% are femaleTotal 19% are femalePoliceWomen represented:21% of constables11% of sergeants9% of inspec<strong>to</strong>rs and chief inspec<strong>to</strong>rs8% of superintendents and above.Prison Workers(Apr 2008 figures – 2009 not released at time of publication)Women represent:27% of constables16% of sergeants14% of inspec<strong>to</strong>r and chief inspec<strong>to</strong>rs11% superintendents and chief superintendents.19% of Governor or equivalent grades were women. 23% of Governor or equivalent grades are women.32% of prison officers were female 23% of prison officer grades are female.Probation Staff18/42 chief officers of probation were women. 19/40 chief officers of probation are women.Legal SystemOn the roll of solici<strong>to</strong>rs 39.5% are female.Of new admissions, 56.8% are female.In 2003 335 men applied <strong>to</strong> the Queens Counsel, 112 wereawarded. 39 women applied, 9 were awarded.On the role of solici<strong>to</strong>rs 44.3% are female.Of new admissions 59.9% are female2008/9 213 men applied <strong>to</strong> QC, 87 were awarded. 29 womenapplied, 16 were awarded.Forensic Medical Examiners18% of forensic medical examiners are female. 18% of FMEs working for the Met Police (29 out of 159) arefemale.Crown Prosecution Service67% of CPS staff are women. 7 (16.5%) Chief Prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs arewomen.67% of CPS staff are women. 16 (38.1%) Chief Prosecu<strong>to</strong>rs arewomen.Page 17

Chapter Two:Introduction - From <strong>Policy</strong> <strong>to</strong> <strong>Practice</strong>For the past five years, the Commission on Womenand the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> System has brought issuessurrounding women and the criminal justice system in<strong>to</strong>the policy spotlight. <strong>The</strong> Commission has highlighted thedisadvantages faced by women throughout the criminaljustice system and has succeeded in prompting legislative,organisational and policy changes. However, while thereis growing awareness and improved policy developmentdesigned <strong>to</strong> obviate the systematic discrimination faced bywomen as offenders, victims and workers in the criminaljustice system, there remains a significant gap betweenpolicy and practical implementation.Part One of this report tracks the key areas of progressand of failure in relation <strong>to</strong> Commission recommendationsacross the agencies and considers how failures intranslating policy in<strong>to</strong> practice are impacting on the actualexperiences of women in the criminal justice system.One of the key emerging themes is a persisting gapbetween strong policy development and consistentimplementation. Evidence <strong>from</strong> female victims of crime,female offenders, women working in the criminal justicesystem and specialist organisations revealed that the needsof women are continually marginalised in a system whichwas designed for men by men. Importantly, there can beno real change until there is a shift in mindset <strong>to</strong>wards arealisation that equality does not require that women betreated the same as men but rather that women shouldbe treated appropriately according <strong>to</strong> their distinct needs –whether accused or convicted of crime, female victims ofcrime or women working in the criminal justice system.When the Gender Equality Duty (‘GED’) came in<strong>to</strong> forcein April 2007, it was identified as having the “potential <strong>to</strong>transform the criminal justice system for women – whetherthey are staff, offenders or victims of crime.” 2 It was hopedthat the duty would result in a more positive, proactiveapproach with the burden resting with all organisationsproviding a public service <strong>to</strong> address discrimination andpromote gender equality. However, results <strong>to</strong> date havebeen disappointing.<strong>The</strong> GED imposes a clear legislative obligation upon publicauthorities <strong>to</strong> adopt a substantive equality (or outcomebased) approach <strong>to</strong> addressing gender inequality. However,there is a lack of understanding around the meaningof substantive equality and how it differs <strong>from</strong> formalequality. Formal equality assumes that all people shouldbe treated alike. Such equality can in fact entrench genderdisadvantage. Substantive equality, conversely, is directedat achieving substantively equal outcomes. A substantiveequality approach <strong>to</strong> tackling disadvantage recognises thatsome inequalities – including gender – are so persistent,durable and institutionalised (in both formal and informalstructures and processes) that <strong>to</strong> treat people in the sameway may simply be <strong>to</strong> reproduce disadvantage, thusperpetuating discrimination. Substantive equality requiresthat the roots of inequality are identified and addressed, andthat ‘special measures’ are likely <strong>to</strong> be necessary <strong>to</strong> achieveequality.Significantly, the Committee on the Elimination ofDiscrimination against Women (‘<strong>The</strong> CEDAW Committee’) inits examination of the United Kingdom in July 2008, notedwith concern that:<strong>The</strong> varying levels of public understanding of the concep<strong>to</strong>f substantive equality have resulted in the promotionof equality of opportunity and of same treatment only,as well as of gender-neutrality, in the interpretation andimplementation of the Gender Equality Duty.<strong>The</strong> Commission shares these concerns. Gender equality isstill not being mainstreamed in<strong>to</strong> all policies and processes,and there is a dearth of mechanisms <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r outcomesand <strong>to</strong> ensure accountability. Further, a misunderstandingof equality as requiring the same treatment for men andwomen has led <strong>to</strong> the redirection of funds <strong>from</strong> women-onlyservices and the application of programmes, services andtreatment designed for men <strong>to</strong> women. <strong>The</strong> Commissionheard evidence that this was particularly a problem at thelocal government level, where organisations have beenasked <strong>to</strong> provide parity of services <strong>to</strong> men irrespective ofneed.As explored in this report, the GED does appear <strong>to</strong> havebeen helpful as a lever for specific policy development inrelation <strong>to</strong> women. For example, the head of the NOMSWomen’s Team noted that the duty had been usefulin pushing for the development of policies such as theGender Specific Standards for Women’s Prisons in PrisonOrder 4800 and in making policy changes such as thebreakthrough new full search arrangements for womenPage 18

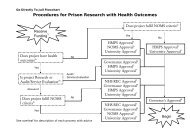

3. Allocateresources4. GenderimpactassessmentFigure 1: <strong>The</strong> Gender Equality Duty & <strong>Policy</strong>-Making 4prisoners.2. Assessneed anddevelop policyHowever, if the duty is <strong>to</strong> be as effectiveas intended there is a need for practicaland cultural change at every stage of thepolicy-making cycle (as outlined in Figure1) that takes in<strong>to</strong> account the needs of menand women. To-date, the practical applicationof the duty has <strong>to</strong>o often been reduced <strong>to</strong>ticking boxes, such as the inadequate or unfocused1. Understanddifferencescompletion of Gender Impact Assessments, rather thanthe mainstreaming of gender within core everyday businessthrough concrete understanding of the different needsof men and women. Worryingly, even the completion ofGender Impact Assessments frequently demonstratesan absence of gender analysis. During its collection ofevidence, the Commission requested a number of impactassessments <strong>from</strong> Government departments and wasdisappointed at the standard of assessments it was shown.Further, the tendency, as noted by the CEDAW Committee,for gender neutrality <strong>to</strong> be equated with gender equality wasapparent. For example, the UK Government delegation <strong>to</strong>the CEDAW Committee in 2008, did not mention the word‘women’ once during its six hours of evidence. 3<strong>The</strong>re has also been a failure <strong>to</strong> moni<strong>to</strong>r and evaluate theoutcome of policies. <strong>The</strong> evidence sessions revealed thatwhere information has been collected there has been atendency for the focus <strong>to</strong> be on collecting informationabout women as an undifferentiated group in the criminaljustice system. Disaggregation of statistics has been afundamental requirement in all UN policies and ensures thatthe intersections between gender and other inequalitiessuch as race and disability can be taken in<strong>to</strong> account.7. Furtherassessment andrefinement of policy5. Implementpolicy6. Moni<strong>to</strong>r andevaluateWe are concerned that given the currentlack of progress in relation <strong>to</strong> the GEDthat the proposed single equality duty forpublic bodies, proposed in the EqualityBill, if enacted, would lead <strong>to</strong> furtherreduced focus on gender inequality and inparticular the need <strong>to</strong> achieve substantiveequality, with gender being lost amongstthe other inequalities. We recommend that theGovernment develops and implements an educationand awareness raising campaign in the public sec<strong>to</strong>r (witha particular emphasis at the local authority level) <strong>to</strong> increaseunderstanding of substantive equality and the practicalimplications of the GED.<strong>The</strong> Commission is also concerned that the key ac<strong>to</strong>rspushing for reform within the criminal justice sec<strong>to</strong>r arelargely women. <strong>The</strong>se women are doing a remarkable job.However, there is also a need for men <strong>to</strong> recognise theskills and experiences which women can bring <strong>to</strong> the justicesec<strong>to</strong>r and the changes which are needed <strong>to</strong> make thesystem more responsive <strong>to</strong> female victims and offenders.A culture of gender equality cannot take root unless mensupport the rights of women, their equal participation asworkers in the system, and understand the distinct needs ofwomen within the criminal justice sec<strong>to</strong>r.Creating a criminal justice system which is fair for womenrequires consistent and focused hard work on the par<strong>to</strong>f criminal justice agencies and organisations. <strong>The</strong>re is aneed for careful evaluation and research as <strong>to</strong> the effectthat policy development is having in practice and anacknowledgement that a culture shift is required in thecriminal justice system before any real change can occur.Clear guidance needs <strong>to</strong> be issued <strong>to</strong> local authorities <strong>to</strong>ensure they fully understand their obligations under theGED in relation <strong>to</strong> the provision of violence against women(‘VAW’) services and the provision of services for femaleoffenders and women at risk of offending. All public bodiesincluding local councils, police services, probation services,health authorities and government departments should beassessing the needs of both women and men and takingaction <strong>to</strong> meet those needs. Public bodies should also besetting themselves pay related objectives that address thecauses of any differences in pay between men and womenthat are related <strong>to</strong> their sex.Part Two of this report sets out the institutional changewhich is needed <strong>to</strong> achieve an engendered justice systemwhich recognises and responds <strong>to</strong> the unique needs,experiences and skills of women and outlines key targetswhich should be reached by 2020.Page 19

Chapter Three:Women and <strong>Justice</strong> – Meeting the Needs of Female OffendersFigure 2: Receptions in<strong>to</strong> Prison Establishments – Prisoners undersentence by length of sentence, 2008It is now well recognised that amisplaced conception of equalityhas resulted in some very unequaltreatment for the women and girlswho appear before the criminaljustice system. Simply put, a maleorderedworld has applied <strong>to</strong> themits perceptions of the appropriatetreatment for male offenders. 5(Lady <strong>Justice</strong> Brenda Hale DBE, Lordof Appeal in Ordinary, December2005)Since the Commission began its work in 2003, therehave been some important developments in recognitionof the distinct needs of female suspects, defendants andoffenders. However, despite these steps forward at thepolicy level, implementation on the ground has been lessevident.Women remain a minority of the prison population (justfive percent of the <strong>to</strong>tal population) in a prison estate thatwas designed by men for male prisoners and it is thereforeno surprise that the system continues <strong>to</strong> overlook theneeds of female offenders. Significantly, women in prisonremained an area of concern for the CEDAW Committeein its examination of the United Kingdom in July 2008. <strong>The</strong>UK Government was urged <strong>to</strong> intensify its efforts <strong>to</strong> reducethe number of female offenders; <strong>to</strong> develop alternativesentencing and cus<strong>to</strong>dial strategies for women convictedof minor offences, including community interventionsand services; and <strong>to</strong> take further measures <strong>to</strong> increaseand enhance educational, rehabilitative and resettlementprogrammes and health facilities and services for women inprison. 6<strong>The</strong> female prison population remains at a disturbinglyhigh level. On 3 April 2009, the female prison population inEngland and Wales s<strong>to</strong>od at 4,309, compared <strong>to</strong> a midyearfemale prison population of 2,672 in 1997. 7 Over thelast ten years, the female prison population has increasedby 60 percent compared <strong>to</strong> a 28 percent increase formen. 8 Due <strong>to</strong> the limited number of prisons in the femaleestate, women continue <strong>to</strong> be held far <strong>from</strong> their homeand families. In 2007, 60 percent of female prisoners wereheld in prisons outside their home region. As one femaleSource: Statistics on Women and the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong>System, Ministry of <strong>Justice</strong>, January 2009, p.49offender <strong>to</strong>ld the Commission: “My sentence has had ahuge impact on my family even more so because I am nowin a prison so far away <strong>from</strong> home.” 9Too many women continue <strong>to</strong> be imprisoned on shortsentences for non-violent crime. In 2007, 63.3 percent ofwomen were sentenced <strong>to</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>dy for six months or less(see Figure 2) and 31 percent of all women sentenced <strong>to</strong>immediate cus<strong>to</strong>dy in 2007 were sent <strong>to</strong> prison for theft andhandling of s<strong>to</strong>len goods. 10 <strong>The</strong> number of women servingsentences up <strong>to</strong> and including three months has increasedby 68 percent since 1997. 11<strong>The</strong>re is now an established body of evidence on thedistinct needs of female offenders. Most notably, theCors<strong>to</strong>n Report published in March 2007 sets out in clearterms the improvements required <strong>to</strong> address the needs offemale offenders. <strong>The</strong> Commission commends the stepswhich have been taken in response <strong>to</strong> the Cors<strong>to</strong>n Report<strong>to</strong> make the criminal justice system more responsive <strong>to</strong> theneeds of female offenders and these are discussed in detailin this section. However, there is much work still <strong>to</strong> be doneand evidence <strong>from</strong> female offenders in cus<strong>to</strong>dy illustratesthat there remains a gap between policy development andchange on the ground.<strong>The</strong> Commission has identified five key areasrequiring urgent attention.• A consistent approach <strong>to</strong> the needs of female suspects inpolice cus<strong>to</strong>dy.• Sentencing of female defendants and the over-use ofremand and cus<strong>to</strong>dial sentences for non-violent offences.• Implementation of the Cors<strong>to</strong>n Recommendations,Page 20

particularly in relation <strong>to</strong> community alternatives <strong>to</strong>cus<strong>to</strong>dy, the mental health needs of female offenders andthe unsuitability of the current female prison estate.• <strong>The</strong> gap between policy and practice especially the lackof a consistent, co-ordinated approach on the ground <strong>to</strong>the needs of women offenders.• <strong>The</strong> failure of criminal justice agencies and local authorities<strong>to</strong> comply with the obligations imposed by the GED.This section considers each of these key problem areasalongside noting the significant progress by the Governmentand criminal justice agencies. Importantly, there can beno real change until those working with women offendersunderstand that equality does not require that womenshould be treated the same as male offenders but ratherthat women offenders should be treated appropriatelyaccording <strong>to</strong> their different needs.Female Suspects– Experiences ofPolice Cus<strong>to</strong>dyAt the police station they don’t let you wash, or brushyour teeth or comb your hair. <strong>The</strong>y don’t even offer you ashower, and they expect you <strong>to</strong> go <strong>to</strong> court like that! 12In 2006/2007, women made up only 16.97 percent ofthose arrested for notifiable offences. 13 While this numberhas been increasing over the previous five years, it stillresults in police dealing with far fewer female suspectsthan males in an environment which has been traditionallydesigned for men. <strong>The</strong>re is still a lack of understandingin relation <strong>to</strong> women’s experiences of cus<strong>to</strong>dy and moredetailed research is required at the local and the nationallevel. However, the limited available evidence suggests thatwomen are likely <strong>to</strong> have a more negative experience ofcus<strong>to</strong>dy than men.International human rights obligations require that allindividuals deprived of their liberty are treated with respectfor their privacy, personal integrity and the inherent dignityof the human person. It is therefore important that facilitiesat police stations, including washing and <strong>to</strong>ilet facilities, areappropriate and dignified for female suspects, includingaccess <strong>to</strong> a female member of staff <strong>to</strong> discuss needs, suchas sanitary protection. <strong>The</strong> Commission has consistentlyrecommended that appropriate hygiene facilities should bemade available <strong>to</strong> female suspects, without the need <strong>to</strong> askfor them. However, the evidence suggests that this is stillnot routine practice. Many women <strong>to</strong>ld us that they werenot offered sanitary protection and were not able <strong>to</strong> havea shower or clean their teeth prior <strong>to</strong> Court. As one femaleoffender described:<strong>The</strong>re were no appropriate hygiene facilities available. Iasked for a sanitary <strong>to</strong>wel and they didn’t come back foran hour and a half. When they did bring me one there wasnowhere <strong>to</strong> dispose of the old one. <strong>The</strong> officer <strong>to</strong>ld me <strong>to</strong>roll it up and leave it in the corner of the cell. I was therefor 23 hours and I was only given one sanitary <strong>to</strong>wel. Iasked for breast pads, but they didn’t have any. I wasn’tallowed <strong>to</strong> shower or wash my face so I had <strong>to</strong> go <strong>to</strong>court feeling dirty. 14Women were also concerned at the lack of cleanliness andthe cold temperature of the cells.Given the high number of women suspects who are likely<strong>to</strong> have experienced abuse by men, 15 it is important thatwomen feel safe in cus<strong>to</strong>dy. All officers should be trained <strong>to</strong>deal with women who have experienced abuse, includingtraining as <strong>to</strong> whether it may be more appropriate for thesuspect <strong>to</strong> be interviewed by a female officer.<strong>The</strong> Commission acknowledges that a current lack ofwomen working as police officers in the cus<strong>to</strong>dy area maymake access <strong>to</strong> a female member of staff difficult. However,the number of women working in the cus<strong>to</strong>dy area shouldbe increased through use of the genuine occupationalqualifications exception in relation <strong>to</strong> recruitment, training,promotion or transfer under section 7(2) of the SexDiscrimination Act; part-time working and job-sharing;or other positive action measures such as the specialmeasures allowed under CEDAW. If cus<strong>to</strong>dy arrangementsare outsourced <strong>to</strong> third party providers, a minimum numberof female staff per shift should be stipulated as a conditionof the contract.<strong>The</strong> significance of the unpaid labour of women as carersPage 21

[A woman] had admitted <strong>to</strong> an offence of theft <strong>from</strong>shops. [She] had accumulated a high level of debt;much of this was related <strong>to</strong> her offending as s<strong>to</strong>res wereattempting <strong>to</strong> recoup their losses. She also had supportneeds in relation <strong>to</strong> substance misuse. [<strong>The</strong> woman] hasengaged well with TWP, seeing this as an opportunity<strong>to</strong> address the issues that were leading her <strong>to</strong> commitshop lifting. She was, at the time, in a cycle of offending<strong>to</strong> pay debts that had been accrued as a result of earlieroffending. Her key worker supported her <strong>to</strong> write <strong>to</strong> theretail recovery agency. At first the debt was put on holdand then it was written off. [She] attends ADS <strong>to</strong> addressher substance misuse issues as well as counsellingwith LCWS. She continues <strong>to</strong> engage with the servicealthough this is likely <strong>to</strong> be relatively short term as hersupport needs have been met. For this [woman], referral<strong>to</strong> TWP as a conditional caution was timely and effective.She has been able <strong>to</strong> address issues that she neededsupport with and had not felt previously able <strong>to</strong> solvealone. She has not re-offended since engaging with theservice. 17Requiring women <strong>to</strong> attend a needs assessment opensthe possibility for each individual <strong>to</strong> consider the reasonsbehind their offending and, in turn, makes them aware ofthe support and training available in the community. Thisrehabilitative approach has largely been absent <strong>from</strong> thenational approach <strong>to</strong> conditional cautioning <strong>to</strong> date. Sincethe scheme began in April 2006 until February 2008, themajority of conditions (just under 60 percent) were forcompensation <strong>to</strong> victims, followed by a letter of apology in15 percent of cases and it was only in just over ten percen<strong>to</strong>f cases that participation in a drug intervention programmewas imposed. 18However, the success of the condition aimed at womenoffenders goes hand-in-hand with the provision of supportservices for women on a national scale. <strong>The</strong> Commissionalso recommends that the impact of the scheme is carefullyevaluated and moni<strong>to</strong>red going forward <strong>to</strong> ensure thatwomen who might have been simply referred for assistanceby the local police, without any formal record of the offence,are not being formally cautioned as a result of the scheme.Female Defendants– Experiences of theCourt System and theSentencing ProcessWomen are always the ones who face court for nonpaymen<strong>to</strong>f TV licenses…We get women who havenever been in court before and they are criminalized andtraumatized unnecessarily. Why should this debt be anydifferent <strong>from</strong> any other non-criminal debt [such as] creditcard debt? Also it is women who almost always have <strong>to</strong>pay the fines for their errant children obviously this is fairenough <strong>to</strong> a certain extent, but what about the fathers?Again we get women in court for not sending their children<strong>to</strong> school. I have yet <strong>to</strong> see a father in this position havingbeen on the bench for 17 years.Female Magistrate, Questionnaire Response, March 2009<strong>The</strong> Legal Profession and Legal Aid<strong>The</strong> Legal Services Commission provides publicly fundedlegal aid <strong>to</strong> individuals facing criminal charges through theCriminal Defence Service. Evidence <strong>from</strong> female offenderssuggested that in the majority of cases, female suspectswere satisfied with the advice received <strong>from</strong> their solici<strong>to</strong>r.Many women commented that they were able <strong>to</strong> deal withthe same solici<strong>to</strong>r they had dealt with previously whichmade them feel reassured or were provided with a dutysolici<strong>to</strong>r who explained the process <strong>to</strong> them. However, theCommission remains concerned that there are frequentlydelays associated with the provision of legal advice. Asone woman stated “It wasn’t until the following day thatI was asked if I wanted legal advice which really stressedme out.” 19 This evidence of extensive delay experienced bysuspects <strong>to</strong>gether with the limited time that duty solici<strong>to</strong>rsare often able <strong>to</strong> spend with their clients suggests theduty solici<strong>to</strong>r scheme remains under-resourced: “<strong>The</strong> dutysolici<strong>to</strong>r explained everything <strong>to</strong> me but he was rushing<strong>from</strong> one station <strong>to</strong> another. <strong>The</strong>refore he <strong>to</strong>ld me <strong>to</strong> givea ‘no comment’ interview.” 20 Of particular concern wasthat many suspects who shared their views with theCommission appeared unsure as <strong>to</strong> their options in relationPage 23

Chapter Three: Continued.Women and <strong>Justice</strong> – Meeting the Needs of Female Offenders<strong>to</strong> legal advice, such as being able <strong>to</strong> elect <strong>to</strong> have theirown solici<strong>to</strong>r rather than the duty solici<strong>to</strong>r. All suspectsshould be provided with the Criminal Defence Serviceinformation sheet which sets out entitlement <strong>to</strong> legal adviceand the cus<strong>to</strong>dy staff should ensure that individuals haveunders<strong>to</strong>od this entitlement.<strong>The</strong> Commission welcomes the research which is beingconducted by the Legal Services Research Centre in<strong>to</strong>whether suspects and defendants in the criminal justiceprocess understand their legal rights when arrested andthe main fac<strong>to</strong>rs influencing their choice of solici<strong>to</strong>r. <strong>The</strong>fieldwork for this research has included interviews with167 female prisoners in HMP Send and HMP Downview.This research is crucial and appropriate funding should beprovided <strong>to</strong> allow thorough research in this area <strong>to</strong> continue.Once the case progressed <strong>to</strong> Court, numerous offenders<strong>to</strong>ld the Commission that they were dissatisfied with theirbarrister or the time they were able <strong>to</strong> spend with him/herand many added that they had not unders<strong>to</strong>od the courtprocess. As one female offender stated “I didn’t understandhow it all worked, I had never been before. I neededmore time with my barrister.” 21 This type of comment wasfrequent.Evidence also suggested there was little information as<strong>to</strong> what women could expect as a sentencing outcome.Anawim, a voluntary sec<strong>to</strong>r organisation working inBirmingham, <strong>to</strong>ld the Commission:“We meet women in the prison and they had no ideathey would go <strong>to</strong> prison and have not even arrangedsomeone <strong>to</strong> pick the children up <strong>from</strong> school let alonelook after them for the next few weeks. <strong>The</strong>y need betterpreparation and information <strong>from</strong> their solici<strong>to</strong>rs.” 22Barristers and solici<strong>to</strong>rs also need <strong>to</strong> be aware of thespecific harms which can result <strong>from</strong> cus<strong>to</strong>dy for womenand their families and ensure that this is clearly presented <strong>to</strong>the Court. As a Magistrate recounted:way. She had a male lawyer who perhaps didn’t take theimplications on board.” 23<strong>The</strong> Poppy Project (providing accommodation, support andoutreach for trafficked women within Eaves Housing) <strong>to</strong>ldthe Commission that poor legal advice has also resulted ina number of trafficked women pleading guilty <strong>to</strong> charges(such as for holding false documents) whilst evidenceabout their trafficking had not been raised in their defence.Defence lawyers are under an obligation <strong>to</strong> make enquiriesas <strong>to</strong> whether there is any credible material showing thattheir client may have been a victim of trafficking 24 andappropriate services such as the Poppy Project should beinvolved at an early stage.Women offenders with children face similar issues <strong>to</strong> thoseexperienced by female victims and witnesses (see ChapterFour) due <strong>to</strong> the lack of childcare facilities available atthe courts. This can cause additional anxiety for femaleoffenders. As TWP <strong>to</strong>ld us:“When attending court, people often have <strong>to</strong> arrive for9.45 for the morning sitting but they are given no definitetime of when they will be appearing, meaning they couldbe sitting and waiting for hours…If women have nochildcare they are forced <strong>to</strong> take their children <strong>to</strong> courtwith them and there are no childcare facilities available…Sometimes women do not even know why they are atcourt and often attend court with no idea of what theoutcome is likely <strong>to</strong> be. This means they do not knowwhether they have <strong>to</strong> set plans in place for childcare or atenancy if they are given a cus<strong>to</strong>dial sentence.” 25<strong>The</strong> Commission recommends that courts should providechildcare services and probation staff or a speciallydesignated member of court staff should be able <strong>to</strong>available <strong>to</strong> assist the mother with arrangements for herchildren in case she is given a cus<strong>to</strong>dial sentence.“We had a case last week where a woman was being sent<strong>to</strong> prison for non-payment of fines and it only emerged bychance after sentence that she was a single mum with a3-month-old baby. So she was re-sentenced in a differentPage 24

Figure 3: Female Reoffending Rate by Length of Cus<strong>to</strong>dial Sentence 2000-2006 29Source: Statistics on Women and the Criminal <strong>Justice</strong> System, Ministry of <strong>Justice</strong>, January 2009, p.61<strong>The</strong> Judiciary and the Sentencing of Female OffendersOf course it is right that the judiciary should jealouslyguard its independence <strong>from</strong> Government and theexecutive. But that does not mean that it should ignorethe concerns expressed by others about the trends forwhich its decisions are responsible. <strong>The</strong> family justicesystem is asking itself whether it is indeed unjust <strong>to</strong>fathers. <strong>The</strong> criminal justice system could also ask itselfwhether it is indeed unjust <strong>to</strong> women. 26(Lady <strong>Justice</strong> Brenda Hale DBE, Lord of Appeal inOrdinary, December 2005)Since its inception the Commission has drawn attention <strong>to</strong>the fact that: <strong>to</strong>o many women are being imprisoned onshort sentences for non-violent crime; there is an over-useof remand for female defendants; and there are <strong>to</strong>o manyforeign national women in prison, particularly those servinglong sentences for drug-smuggling offences. Much ofthe rise in the female prison population can be attributed<strong>to</strong> a significant increase in the severity of sentencing. Forexample, in 1996, 10 percent of women convicted of anindictable offence were sent <strong>to</strong> prison. While in 2006, 15percent of women were. 27 Short sentences continue <strong>to</strong>have a devastating effect on the lives of women whileleading <strong>to</strong> increased rates of reoffending. As a prisonworker commented <strong>to</strong> the Commission, “Getting sentenced<strong>to</strong> four weeks for driving whilst disqualified, what does itachieve” 28A lack of information available about sentencing practicesmakes it very difficult for any analysis of the reasons behindthis increase in the severity of sentencing. This dearthof information is an issue of particular concern <strong>to</strong> theCommission, resulting in limited knowledge as <strong>to</strong> the effec<strong>to</strong>f sentencing guidelines or trends in sentencing in relation<strong>to</strong> female offenders.<strong>The</strong> Commission understands that the new SentencingCouncil, proposed in the Coroners and <strong>Justice</strong> Bill, willbe coordinating the collection of data on sentencing.Information on gender, ethnicity, previous convictions,mitigating circumstances and aggravating fac<strong>to</strong>rs is crucialin the long term in order <strong>to</strong> understand sentencingpractices and trends. Mechanisms and resources shouldbe put in place <strong>to</strong> collect this information. However, in theshort term, the NOMS regional structure could be utilised<strong>to</strong> compile information which is currently available suchas offence type and sentencing outcome. It is crucial thatsteps are taken <strong>to</strong> collect this information and in fact, thecollection of data and the implementation of moni<strong>to</strong>ringsystems <strong>to</strong> assess the different impacts of sentences onwomen and men are necessary in order <strong>to</strong> comply withthe GED. This duty will also apply <strong>to</strong> the new SentencingCouncil.<strong>The</strong> Commission has consistently recommended that theSentencing Advisory Panel should conduct a thematicreview in<strong>to</strong> women offenders. However, the Commissionwas <strong>to</strong>ld by the Sentencing Advisory Panel, that a lackof resources and the need <strong>to</strong> prepare guidelines for newlegislation, had led <strong>to</strong> an inability <strong>to</strong> conduct research onthis issue. <strong>The</strong> proposed Sentencing Council must besufficiently resourced <strong>to</strong> enable such research, includingrecent trends in sentencing and whether the availablerequirements of the community order are effectively meetingthe needs of women offenders.Page 25