pow/mia recognition day - Veterans of Foreign Wars

pow/mia recognition day - Veterans of Foreign Wars

pow/mia recognition day - Veterans of Foreign Wars

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

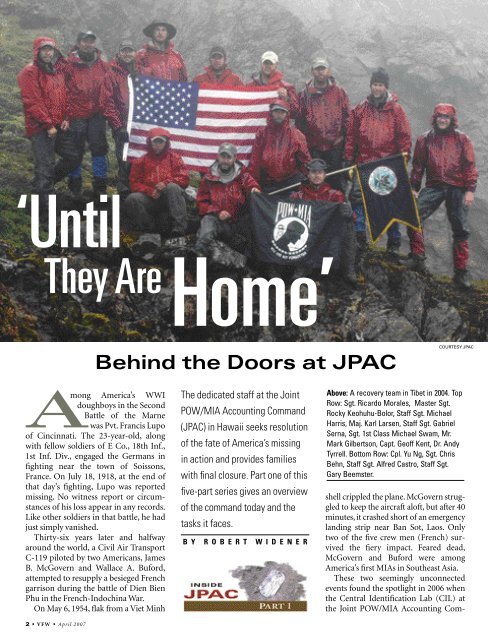

‘UntilThey AreHome’Behind the Doors at JPACCOURTESY JPACAmong America’s WWIdoughboys in the SecondBattle <strong>of</strong> the Marnewas Pvt. Francis Lupo<strong>of</strong> Cincinnati. The 23-year-old, alongwith fellow soldiers <strong>of</strong> E Co., 18th Inf.,1st Inf. Div., engaged the Germans infighting near the town <strong>of</strong> Soissons,France. On July 18, 1918, at the end <strong>of</strong>that <strong>day</strong>’s fighting, Lupo was reportedmissing. No witness report or circumstances<strong>of</strong> his loss appear in any records.Like other soldiers in that battle, he hadjust simply vanished.Thirty-six years later and halfwayaround the world, a Civil Air TransportC-119 piloted by two Americans, JamesB. McGovern and Wallace A. Buford,attempted to resupply a besieged Frenchgarrison during the battle <strong>of</strong> Dien BienPhu in the French-Indochina War.On May 6, 1954, flak from a Viet Minh2 • VFW • Apr il 2007The dedicated staff at the JointPOW/MIA Accounting Command(JPAC) in Hawaii seeks resolution<strong>of</strong> the fate <strong>of</strong> America’s missingin action and provides familieswith final closure. Part one <strong>of</strong> thisfive-part series gives an overview<strong>of</strong> the command to<strong>day</strong> and thetasks it faces.B Y R O B E R T W I D E N E RAbove: A recovery team in Tibet in 2004. TopRow: Sgt. Ricardo Morales, Master Sgt.Rocky Keohuhu-Bolor, Staff Sgt. MichaelHarris, Maj. Karl Larsen, Staff Sgt. GabrielSerna, Sgt. 1st Class Michael Swam, Mr.Mark Gilbertson, Capt. Ge<strong>of</strong>f Kent, Dr. AndyTyrrell. Bottom Row: Cpl. Yu Ng, Sgt. ChrisBehn, Staff Sgt. Alfred Castro, Staff Sgt.Gary Beemster.shell crippled the plane. McGovern struggledto keep the aircraft al<strong>of</strong>t, but after 40minutes, it crashed short <strong>of</strong> an emergencylanding strip near Ban Sot, Laos. Onlytwo <strong>of</strong> the five crew men (French) survivedthe fiery impact. Feared dead,McGovern and Buford were amongAmerica’s first MIAs in Southeast Asia.These two seemingly unconnectedevents found the spotlight in 2006 whenthe Central Identification Lab (CIL) atthe Joint POW/MIA Accounting Com-

mand (JPAC) in Hawaii, identified theremains <strong>of</strong> both Lupo and McGovern.(Buford’s remains have yet to be discovered.)The cases brought much-heraldedattention to JPAC’s efforts in recoveringremains and identifying America’s missingin action.Lupo, whose remains were discoveredin 2003, became the first MIA fromWWI to be identified. McGovern’s identificationinvolved a complex DNA procedure.His remains were found in 2002.The solution in providing the finalchapter to these cases, and so many more<strong>of</strong> the 88,000 still missing from America’swars, lies along many lines <strong>of</strong> cooperationbetween Department <strong>of</strong> Defense (DoD)<strong>of</strong>fices, the service branches and especially,the dedicated personnel behind thedoors at JPAC, where the motto “UntilThey Are Home” truly resides in eachperson’s heart.JPAC History and StructureGiven the high-tech world we live into<strong>day</strong>, the recovery and identificationwork at JPAC knows few boundaries. Itowes its present state, though, to an evolutionthrough the years from earlieragencies that had one common quest—return America’s missing heroes to theirfamilies. A quick review <strong>of</strong> its transformationalso shows the relentless supporta deeply dedicated nation has puttoward that goal.At the end <strong>of</strong> the Vietnam War inJanuary 1973, provisions in the ParisPeace Accords led to the creation <strong>of</strong> theJoint Casualty Resolution Center (JCRC).Headquartered in Thailand, it searchedfor and recovered remains <strong>of</strong> Americansmissing in action. JCRC worked in concertwith the newly formed CentralIdentification Laboratory, Thailand (CIL-THAI), a relocated U.S. mortuary thathad handled the remains and identification<strong>of</strong> Americans killed during the war.By 1976, a downsizing <strong>of</strong> U.S. forcesin Thailand classified CIL-THAI andJCRC personnel as military, rather thanhumanitarian. As a result, the operationswere forced to relocate. Hawaiiwas chosen as the new home, and thelab name thus changed to CILHI. At thesame time, CILHI’s mission was broadenedto include the identification <strong>of</strong>service members killed in Korea, WWIIand recent operations.JCRC continued operation until 1992when it became Joint Task Force-FullAccounting (JTF-FA). The change waspartly due to an increased interest fromthe U.S. government as well as the publicin MIA recovery. More important,though, Southeast Asian countries wereshowing an increased willingness to allowaccess to records, files and witnesses concerningunaccounted-for Americans.Finally, in 2002, DoD concluded thatPOW/MIA accounting efforts wouldbest be served by combining JTF-FA andCILHI. On Oct. 1, 2003, the two agenciesmerged and were renamed JPAC.Brig. Gen. Michael Flowers, a 28-yearArmy veteran, directs JPAC’s 425 militaryand civilian personnel based atHickam Air Base and nearby CampH.M. Smith in Hawaii. Assisting Flowersis Deputy Commander Johnie Webb, aformer commander <strong>of</strong> CILHI from1982-1993. Webb brings a long history<strong>of</strong> involvement in POW/MIA accounting,beginning in 1975 as a search-andrecoveryteam leader.The overall structure <strong>of</strong> JPAC is dividedinto four sections: command andsupport, search and recovery operations,casualty data analysis and the laboratory.PHOTO BY ROBERT WIDENER / VFWStaff and personnel are a mixture <strong>of</strong> servicemembers from the different branches,and pr<strong>of</strong>essional civilians whoprovide expertise in crucial areas, suchas dentistry, anthropology and historicalresearch.According to Webb, the most importantchange through the years has beenreplacing morticians with scientists inthe lab.“When I originally took command,the holdover from the Vietnam War wasusing morticians to make the identifications,”said Webb. “We needed tobring key scientific staff on board to dothe work that needed to be done.”Currently, the lab has 23 anthropologists,four archeologists and three dentistson staff.JPAC’s operations extend overseas, aswell. It maintains three detachments inSoutheast Asia to assist with command,logistics and valuable in-country supportduring field operations. These arelocated in Bangkok, Thailand; Hanoi,Vietnam; and Vientiane, Laos. A fourthdetachment at Camp H.M. Smith isresponsible for recovery team personnelwhen they’re not deployed.Operating under U.S. Pacific Com-Anthropologist Dr. Derek Bendix studies remains in the Central Identification Lab (CIL) atJPAC. The largest forensics lab in the world, CIL employs 30 anthropologists, archeologistsand dentists. It completes an average <strong>of</strong> two identifications each week.Apr il 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 3

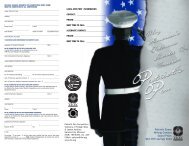

Accounting for the Missing by WarFigures for the Vietnam War are current as <strong>of</strong> Feb. 15, 2007; all others are as <strong>of</strong> Sept. 9, 2006WAR AND CURRENT TOTAL UNKNOWNS BURIED BURIAL AT SEA/ NO FURTHER RECOVERIES AT POSSIBLYGEOGRAPHIC UNACCOUNTED AT NATIONAL MISSING BURIED PURSUIT JPAC-CIL TO RECOVERABLEAREA FOR CEMETERIES OR LOST AT SEA OVER LAND BE IDENTIFIED 1Vietnam WarCambodia 54 0 0 4 11 39Laos 359 0 0 39 21 292Vietnam 1,367 0 394 217 90 665China 7 0 3 0 0 4Cold War 125 0 104 1 0 20Korean WarNorth Korea 5,561 414 292 N/A 480-580 4,580South Korea 980 451 0 N/A 0 875WWIIPacific 45,120 2 6,318 3N/A 11,3868,600576-7684China, Burma, India 3,585 (Not broken out (Not broken outN/A (Not broken out 949 4Europe 21,047 geographically) geographically) N/A geographically) 4,554 4Americas 3,166 N/A 2,087 4Worldwide 73,291 5 N/A 18,976 41 Includes co-mingled remains.2 Estimates <strong>of</strong> WWII unaccounted-for by theater <strong>of</strong> operations are projections based onthe geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> non-recovered servicemen listed by the American GravesRegistration Service Roster <strong>of</strong> Remains not Recovered or Identified. Numbers are refinedas new records are reviewed.3 WWII number includes only those confirmed “buried at sea” not all lost at sea.4 Estimates are based on the geographic distribution <strong>of</strong> WWII servicemen recovered andidentified between 1978-2006.5 The total number <strong>of</strong> current WWII unaccounted-for is calculated by subtracting identificationsfrom 1978-2006 (376) plus the verified number <strong>of</strong> servicemen buried at sea(6,318) from the total number <strong>of</strong> men listed as non-recovered on the 1983 Department<strong>of</strong> Army Rosters <strong>of</strong> the Dead for All Services (79,985).Note: Not included are three unaccounted-for from the Persian Gulf War; USN Capt. Michael Speicher is “missing-captured’, and USN Cmdrs. Barry Cook and Robert Dwyer are “KIA,body not recovered.” Also, the 1986 Libya attack, Operation El Dorado Canyon, has one MIA, USAF Capt. Paul Lorence.Source: Defense Prisoner <strong>of</strong> War/Missing Personnel Officemand, JPAC depends on direct assistancefrom other DoD <strong>of</strong>fices to completeits mission.The Defense Prisoner <strong>of</strong> War/MissingPersonnel Office (DPMO) in Washington,D.C., is responsible for policy andoversight <strong>of</strong> U.S. POW/MIA efforts.DPMO communicates with other U.S.agencies and the public, especially families,on overall progress. In addition toother planning and research, it also coordinatestalks with countries where missionsare proposed, helping to pave theway for JPAC to work out final details.The Armed Forces DNA IdentificationLaboratory (AFDIL) in Rockville,Md., conducts DNA analysis. CIL sendssamples from skeletal remains toAFDIL for DNA processing, then evaluatesthe results.The Life Sciences Equipment Laboratory(LSEL) at Brooks Air Base in Texasanalyzes some <strong>of</strong> the artifacts recoveredduring field operations. Its experts cantell, for example, from what plane a piece<strong>of</strong> glass may have come, or determine4 • VFW • Apr il 2007the origin <strong>of</strong> a patch <strong>of</strong> fabric.Also playing an essential role are themilitary service branches. Soldiers,Marines, airmen and Navy personnel,most with combat experience and manywho are recently from the wars in Iraqand Afghanistan, can volunteer for JPACas one <strong>of</strong> their rotated duty stations. Themixture <strong>of</strong> the different branches createsa joint military force, giving the servicemembers a unique opportunity to workas a team.The casualty <strong>of</strong>fices at the branchesalso work closely with JPAC, DPMOand AFDIL, but primarily serve as a liaisonto families <strong>of</strong> the missing. Theyprovide updated information on particularmissions, serve as conduits toand from other agencies and coordinateDNA family reference samples.As the years have progressed, so havethe procedures and communication rolesbetween the agencies and JPAC. Theresulting finely honed system enables itto operate smoothly in not only resolvingthe fate <strong>of</strong> the missing, but more important,giving closure to the families whohave waited so long for answers.Mission PrioritiesWhen JPAC was formed in 2003, thetransition plan dictated that a certainnumber <strong>of</strong> joint field activities (JFA) beconducted each year. The missions aredivided between Southeast Asia––whichincludes Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia andThailand––and worldwide, which sendsteams to such places as Europe, SouthKorea, China and even New Guinea.Southeast Asia missions are mainlyfocused on the Vietnam War, while thoseworldwide cover losses that occurredduring WWI, WWII, Korea, the ColdWar and other operations. JPAC followsa 10-5-10 formula in breaking down theJFAs: 10 in Southeast Asia, 5 in Koreaand 10 worldwide.Each JFA contains multiple searchand-recoveryoperations that can last30-45 <strong>day</strong>s each. For instance, in fiscalyear 2007, which began on Oct. 1, 2006,Continued on page 5 ➲

‘Until They Are Home’➲ Continued from page 4one JFA in Southeast Asia includes fourrecovery, one investigative, one underwatersearch and one combinationinvestigative/recovery teams.Flowers follows established policyand prioritizes missions by the followingcriteria, not necessarily in this order:• Last known alive: This refers to thepoint that an MIA was last seen alive.• Existing site: Recovery operationssometimes require more than onevisit, or remains were found at the end<strong>of</strong> an operation.• Developments in countries: A nationmay be planning construction in anarea where MIAs may be located.• Weather: Seasonal patterns can hampera team’s field operation, resultingin the loss <strong>of</strong> precious time.• Equilateral turnovers: Artifacts orbones are discovered and turned overby a country.• Host nation limitations: Some countrieshave a cap on the number <strong>of</strong>personnel involved.• Best case for a specific time frame.were getting ready to develop the harborarea in 2009,” Webb said. “So, wehave two years to get in and completethat recovery.”Flowers pointed out that “no one caseis more important than any other,” andthey follow a strict adherence to thepoints above.“We get congressional inquiries, butwe don’t move people to the head <strong>of</strong> theline because their senator writes to say‘I’m interested,’ ” he stressed. “We tellthem exactly what we told the family—that this is where they’re at in the line,and we’re working on it.”And that list grows shorter eachyear—the lab now averages two identificationseach week, or 100 per year.Meeting with Other CountriesNegotiations with host nations aboutupcoming missions are an enormousdiplomatic undertaking coordinated byDPMO. These meetings occur one tothree times annually and center on investigationsand recoveries planned in thecountry. When working with SoutheastAsian countries, government <strong>of</strong>ficials areaccess to restricted areas are normal topics.In addition, host nations want toknow the length <strong>of</strong> the mission, the number<strong>of</strong> personnel involved and the type <strong>of</strong>equipment and vehicles to be used. Thetalks also cover how much local workersand landowners will be paid, and whatcompensation will be given to local <strong>of</strong>ficialsassigned to the site.Flowers says “they work well with allcountries” on these matters, and “nonehave kept them from doing missions.”He adds that Cambodia has been theeasiest country to work with, whileVietnam’s rules and regulations tend tocomplicate matters.(North Korea did head the “most difficult”list, but missions there have beensuspended since spring 2005 over concernfor the teams’ safety.)In Vietnam, for example, an underwaterinvestigation was proposed, butVietnamese <strong>of</strong>ficials objected to U.S.flagships within their waters. Similarly,missions for the longest time have beenbarred in the western highlands wherethe Vietnamese cited problems in thearea. However, last year, one mission“We don’t move people to the head <strong>of</strong> the line because their senator writes to say‘I’m interested.’ We tell them exactly what we told the family—that this is wherethey’re at in the line and we’re working on it.”—Brig. Gen. Michael FlowersJPAC determines which MIA casesultimately become missions. Forinstance, when an investigation teamreturns from the field, an executivedecision board that includes Flowers,deputy commanders and other keyJPAC personnel determines if the findingswarrant a recovery operation. Ananalyst or historian from the casualtydata section also weighs in with recordsresearch. After all the evidence is evaluated,Flowers makes a final decision onwhether to proceed with a recovery.An example <strong>of</strong> how a proposeddevelopment in another country canchange the priority <strong>of</strong> a particular caserecently occurred after a trip to SouthKorea by Webb.“During one <strong>of</strong> our underwaterinvestigations, we found out that theyinvolved, whereas worldwide operationsdeal more with local <strong>of</strong>ficials.Usual participants in the meetingsinclude staff from DPMO and a DoDintelligence agency, as well as JPAC’scommanding general. A representativefrom an overseas detachment, if the missionfalls within its domain, and a U.S.ambassador also sit in on the discussions.According to Larry Greer, director <strong>of</strong>public affairs at DPMO, the talks are“generally a give-and-take event, whereboth sides are working toward the samegoal—getting our teams out into thefield with the full support <strong>of</strong> the nation.”Once the groundwork has been laid,JPAC takes control <strong>of</strong> the meeting.Specific cases are discussed as well asfuture activities. Difficulties in terrain,communications and inquiries aboutwas allowed to be carried out, and JPAChas permission to return again this year.VFW Averts Funding CrisisAs if courting Communist countrieswere not enough, the missions werethreatened from another angle. In fiscalyear 2006, part <strong>of</strong> the crucial funding forJPAC, which falls under U.S. PacificCommand’s budget, was cut.VFW stepped forward and demandedthat JPAC be fully funded. According toMichael Wysong, VFW’s national securityand foreign affairs director, “VFWlaunched this initiative and led thecharge. A couple <strong>of</strong> other groups weighedin, but not to the extent that VFW did.”Though $3.6 million was restored to<strong>of</strong>fset the shortfall, it was too late toContinued on page 6 ➲Apr il 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 5

‘Until They Are Home’➲ Continued from page 5reschedule some <strong>of</strong> the missions.At the time, Bob Wallace, executivedirector <strong>of</strong> VFW’s Washington Office,said, “It was unconscionable that duringa time when our service men and womenare risking all to protect our freedoms,our government does not see fit to fund aprogram to find our prisoners <strong>of</strong> war orthose missing in action.”Says Wysong, “As a result <strong>of</strong> ourefforts last year, Congress, in the FY ’07Defense budget, asked to see where andhow all organizations involved inPOW/MIA issues are budgeting andspending their allotted resources.”VFW further calls for JPAC’s budgetto be a dedicated single-line item in thelarger Defense budget.“We appreciate VFW’s support as veterans,”Flowers said. “We work veryhard to find and bring their comradeshome. This is a relationship built ontrust, and we try our best to live up toit.”Continuing the EffortWorking a four- to five-year plan,Flowers looks for ways to keep the operationsas efficient as possible.Two aspects <strong>of</strong> recovery operations,for example, were adjusted to reduce thenumber <strong>of</strong> visits to a site, yet still yieldreliable results. A scientific testing stagein the field was streamlined. And, missionsin Vietnam were lengthened from30 to 45 <strong>day</strong>s, allowing teams ampletime at a site.Overall, progress is proceeding well.Recoveries in Cambodia have reached apoint where nine sites are ready forexcavation. Flowers says they should befinished there in two years with thecases they know <strong>of</strong> now, cautioningthat new evidence could change that.In addition to Vietnam, Laos andCambodia, missions through September2007 are being conducted in NewGuinea, Palau, China, Thailand, SouthKorea and Europe.For Flowers, the overall success <strong>of</strong> themissions carries a huge responsibility—onethat is most evident when anidentification is made and he comesface-to-face with the family.“Something that you’re not preparedfor when you come here is the families,the emotions,” he said. “There is nothingmore rewarding to us than when wedo make an identification, and the familycomes here to pick up the remains.We get to talk to them and see theimpact that we made on them.”JPAC has one core goal—bring homethose who remained behind on foreignsoil so they can be reunited with theirfamilies. With its committed staff andpersonnel working alongside U.S. agenciesand the military service branches,and adequate funding in place, thatgoal is reached time after time.McGovern’s nephew, James McGovernIII, explained it best to The AssociatedPress: “All those years were enough <strong>of</strong> aseparation. It’s closure for my family, anda great feeling.”✪PART II (JUNE): Casualty Data Analysis:Where Cases BeginE-mail rwidener@vfw.orgEditor’s note: The author visited JPAC<strong>of</strong>fices and the Central IdentificationLaboratory in December to get a firsthandview <strong>of</strong> operations there.6 • VFW • Apr il 2007

Casualty Data Analysis:At the Forefront<strong>of</strong>MIA CasesTall, slender archivalboxes, all neatly labeled,sit solemnly on shelvesat the Joint POW/MIAAccounting Command (JPAC) inHawaii. Inside the boxes are folders,each with its own story about a soldier,or perhaps an airman. They containpersonal medical data, letters from awife or father, and sometimes even aphoto. As different as each story may be,they all have one thing in common—theperson was reported missing in actionin one <strong>of</strong> America’s wars.To the analysts and historians withinthe casualty data analysis section atJPAC, the files are a treasure trove. Muchlike historical detectives, the staff turnsto these files and a multitude <strong>of</strong> militaryrecords to determine two main factors inthe overall MIA accounting process: thefeasibility <strong>of</strong> sending out an investigationteam, and providing historical andscientific background to help identifyremains.Lt. Col. Dale Norris, a 21-year AirForce and Persian Gulf War veteran,heads the casualty data staff. AssistingNorris is Deputy Director Rob Richeson,a retired Air Force master sergeant whostarted with Joint Task Force-Full Accountingin 1993.Because <strong>of</strong> the varied nature <strong>of</strong> eachwar, staff researchers are specialists ondifferent wars. The section has threedivisions—Southeast Asia, which isconcerned primarily with the VietnamWar; the Korean War; and worldwide,Mining a vast array <strong>of</strong> military records is a crucial first stepin determining MIA missions.which includes WWI, WWII, the ColdWar and other operations, even somedating back to the Civil War.“Most <strong>of</strong> our people are involved inSoutheast Asia,” Richeson explained.“That’s in line with the strategy comingfrom Washington. There is a requirementto investigate and to come tosome resolution for every one <strong>of</strong> theguys unaccounted for.”In Southeast Asia, cases rely more onfield investigative work where teamsvisit suspected crash or battle sites.Here, team personnel have the opportunityto conduct interviews with eyewitnesseswho may have been childrenat the time <strong>of</strong> the incident.Worldwide cases turn to historicalrecords analysis due to the lack <strong>of</strong> suchfirsthand accounts. Only in a few caseshave veterans contacted analysts withvital information about a buddy whowas missing during a battle.Sometimes information can comefrom unusual sources. For example, amateurrelic hunters in Europe who plunderWWII battle sites for pr<strong>of</strong>itable artifactshave stepped forward in the past to cooperateand disclose their findings.According to historian Heather Harris,whose specialty is the Korean War, theyreceive a number <strong>of</strong> leads each <strong>day</strong>. “NotB Y R O B E R T W I D E N E Rall information leads to a case, but all <strong>of</strong>the discoveries have to be checked out,”she said.Regardless <strong>of</strong> the source, a “discovery”is where new cases begin at JPAC. Thefind sends the analysts and historiansmining their resources, hopefully, touncover the “who, what or when” inorder to warrant further action.IDPFs Are IndispensableMilitary personnel records top the list <strong>of</strong>reference materials used by the casualtydata researchers. Unfortunately, the 1973fire at the National Personnel RecordsCenter in St. Louis, Mo., destroyed 80%<strong>of</strong> the 22 million records for Army personneldischarged between Nov. 1, 1912,and Jan. 1, 1960. Also destroyed wereabout 75% <strong>of</strong> the records for Army AirForces and Air Force personnel dischargedbetween Sept. 25, 1947, and Jan1, 1964.Lacking that resource, utmost in theanalyst’s arsenal is individual deceasedpersonnel files (IDPFs)—informationcompiled on every military person duringhis or her service dating back toWWI. The files, regardless <strong>of</strong> whatbranch the person served in, are housedat the Washington National RecordsCenter in Suitland, Md. The ArmyJune/July 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 7

Stephanie Young assists in the records department within the casualty data analysis sectionat JPAC. The files provide analysts with military personnel information for warranting aninvestigation mission, and later, to scientists in the identification <strong>of</strong> remains in the lab.holds executive oversight <strong>of</strong> them dueto its role in the graves registration processduring WWII.“IDPF files are the single most completedocument for us,” said Harris, “interms <strong>of</strong> combining information aboutthe individual that we need for identification,with information about the wayin which they were killed.”The files are rich in details. Somerecords, stamped out with WWII-eratypewriting, are on fragile onion-skinpaper. They contain items such as themost recent medical and dental records,letters from family members concerningthe loss, and sometimes photographs <strong>of</strong>the missing person. Airman files contain8 • VFW • June/July 2007a “missing crewman report” with informationon the loss, the aircraft and itsserial numbers.Also included are reports on investigationsby the service branch that weredone at the time <strong>of</strong> the incident to locateand identify the missing serviceman. Inaddition, records may hold correspondenceconcerning the disposition <strong>of</strong>personal effects, yielding clues such thatan individual smoked a pipe—valuableinformation if one is recovered amongthe artifacts in the field.Foremost, Korean War records dealprimarily with the loss itself and providemore information on the servicemember than records from any otherPHOTO BY ROBERT WIDENER / VFWwar period.IDPFs are photocopied after they arereceived at JPAC, then digitally scannedand stored in a computer database. Thismethod allows the data to be easilyshared by not only the researchers, butby teams in the field. JPAC has alreadyprocessed 95% <strong>of</strong> Korean War MIAfiles; WWII numbers 3,000. And forSoutheast Asia, every file on every MIAis already processed.IDPFs are not the only source <strong>of</strong>record data for the researchers. Battlefieldloss documents give details fromdaily morning reports <strong>of</strong> units operatingin the area. Also, the National GravesRegistration Service, which at one timedevoted resources to resolving WWIIand Korea MIAs, has records that showhow far they proceeded with their owninvestigation, or where in the NationalArchives to look for such things as unithistories.“Also, depending on what theateryou’re talking about,” said Harris,“therewere historians deployed in the field atthe time who did combat interviews.We use those interviews to see if certainpeople are mentioned.”Overall, the casualty data analystsfind they are most successful with aircrashes due to the missing crewman’sreport and correlating debris found atthe crash site. Battlefield losses are thesecond most successful.When all data has been collected andevaluated, a “loss incident case file” iscreated. These compilations prove indispensableto investigation and recoveryteams in the field, and later, to scientistsin the lab for final identification.‘No One Wants to Let Go’Still, despite all <strong>of</strong> their efforts andresources, accounting for the remainingMIAs, particularly in Southeast Asia,frustrates Richeson.“We’ve been looking for those guyssince the ’70s, and the answers aren’t inthose files,” he said referring to theIDPFs. “We’ve been through them ahundred or more times trying to resolvethese cases.”Harris says the files hold morepromise for worldwide cases. “It’s differentfor conflicts other than SoutheastAsia,” she said. “There’s still a lot to begained from the records we have, and

from the archives on the mainland.”Their efforts are sometimes augmentedby the diligence <strong>of</strong> private individualsworking on their own. In thepast, these dedicated people have providedJPAC analysts with vital research.One such researcher, Ray Emory, aPearl Harbor survivor, has researchedsince 1968 records <strong>of</strong> those listed asunidentifiable from the WWII Japaneseattack. About 2,000 such remains areinterred at the “Punchbowl” NationalCemetery <strong>of</strong> the Pacific in Honolulu.Emory is able to obtain five IDPFs eachyear through the Freedom <strong>of</strong> InformationAct. He then painstakingly comparesthose files to the records <strong>of</strong> the remains atthe time <strong>of</strong> burial, focusing mostly ondental records.Emory contacted Harris in November2003 concerning a possible match. Harrissaw potential in Emory’s evaluation andafter further research, came to similarconclusions.The remains were exhumed andexamined by JPAC’s Central IdentificationLaboratory which confirmed theidentity—Seaman 2nd Class WarrenPaul Hickok, a crewman <strong>of</strong> the USSSicard. Evidence suggests he most likelyperished while helping others aboardthe USS Pennsylvania during the attack.Dealing with battle reports and personnelfiles on a daily basis can take itstoll on the researchers, though. ForHarris, the daily pace <strong>of</strong> poring overrecords <strong>of</strong> POWs who died in thebombing <strong>of</strong> a Japanese hell ship, or themissing from Pearl Harbor, or POWcamps in the Philippines, can be emotionallydraining.“After a while,” she said, “you feel likeyou’re dwelling on death and destructionso much it can weigh on you.”In the end, giving closure to the familiesmakes it all worthwhile. The challengeis trying to stay passionate aboutthe work without getting psychologicallyexhausted. And sometimes, it getspersonal.“When things go well, it’s veryrewarding,” Richeson said. “Nobodylikes to give up on anything, or have acase that you can’t do anything on … noone wants to let go.”✪E-mail rwidener@vfw.orgPART III (AUGUST): Teams in the Field.June/July 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 9

MIA Teams in the Field:PHOTO BY CPL. RICARDO MORALES, U.S. MARINE CORPSMIA teams traverse jungles and mountain peaks in therelentless search for and recovery <strong>of</strong> America’s missing inaction. For team members, ‘there’s no better job in the world.’B Y R O B E R T W I D E N E RNavy veteran JamesPokines remembersthe intensely coldnights, the intermittentrain that fell through the <strong>day</strong>and the snow that thawed right afterfalling, saturating the gravelly earthwhere he dug. He also remembers workingbare-handed because any gloveswould be soaked after 10 minutes, freezinghis hands. He especially remembersthe hail.“I stood and stared for a full 30 minutesas it hailed on us, and I wondered,‘What next?’ ” he said.10 • VFW • September 2007Pokines recalled his role as anthropologistand recovery team leader in a14-man MIA mission that in August2002 ventured into the southeasternTibetan Himalayas in China. Operatingat nearly 16,000 feet, they were determiningif remains <strong>of</strong> four crewmencould be recovered from a WWII C-46that crashed in March 1944.Their mission was tw<strong>of</strong>old: Whileeight team members worked the crashsite, six others trekked across a glacierto investigate another C-46 crash sitefor a future mission.The Tibetan operation proved to be atest <strong>of</strong> physical endurance, not to mentionthe mental toll <strong>of</strong> isolation on amountaintop. In the end, the mission’sextreme nature proved how dedicated theteam members <strong>of</strong> the Joint POW/MIAAccounting Command (JPAC) can be intheir noble task <strong>of</strong> accounting forAmerica’s MIAs.Sacred ObligationSome 200 active-duty personnel make upJPAC’s 18 recovery and three investigationteams headquartered in Honolulu.MIA teams can be found operating mostanywhere in the world, from the frozen

Left: Members <strong>of</strong> a JPAC team searchthrough wreckage <strong>of</strong> a WWII aircraft in theHimalayan mountains <strong>of</strong> southeastern Tibeton Sept. 3, 2002. The team recovered foursets <strong>of</strong> remains, two <strong>of</strong> which wereidentified in 2006.landscape <strong>of</strong> Alaska to the dense jungles<strong>of</strong> Laos, and even on the WWII battlefield<strong>of</strong> Iwo Jima. The scope <strong>of</strong> searchesnow spans WWII to the Persian GulfWar. Currently, however, nearly twothirds<strong>of</strong> the missions are focused onSoutheast Asia and the Vietnam War.The first joint MIA recovery operationoccurred in 1985 when Johnie Webb,JPAC’s current deputy commander, led ateam in Vietnam. For years, Webb hadlobbied the Vietnamese to allow U.S.teams into the country, but each time hisrequest was denied. Finally, a breakthroughin relations opened the door.“Being a Vietnam veteran and seeingmen killed in battle, and knowing wehad left people behind,” Webb said, “Ithought it was very important to bringsome <strong>of</strong> those men back home who hadmade the ultimate sacrifice.”In the end, the successful missionpaved the way for the U.S. to return timeand time again in the following years.Getting Teams into the FieldImagine scheduling several hundredpeople on 21 different teams that makeup 51 separate missions at different times<strong>of</strong> the year to nine nations. Next, coordinatewith each service for extra personnelfor those teams, and ask the military forthe aircraft necessary to get everyone andeverything to its destination and back.Did we also mention that each countryhas its own maze <strong>of</strong> requirements andregulations governing such expeditions?Welcome to JPAC’s OperationsDepartment—a vital and <strong>of</strong>ten overlookedhub in the MIA effort. Theresponsibility rests here for putting all<strong>of</strong> JPAC’s missions into action by planningevery minute detail. In addition,the Operations Department overseesdeployment, monitors the teams’progress in the field and provides dailybriefings on their status.Within the 24-person department isDeputy Director Joe Patterson, a longtimeoperations taskmaster. Patterson, aMarine Vietnam vet, began similarduties in 1989 with the Joint CasualtyResolution Center, and later with JointTask Force-Full Accounting.“We estimate cost and man<strong>pow</strong>errequirements and put them all in anoperational schedule,” said Patterson,who is a VFW life member <strong>of</strong> Post 2485in Angeles City, Philippines.Planning takes into account a multitude<strong>of</strong> details such as weather patterns,the length <strong>of</strong> the mission and any hostnationholi<strong>day</strong>s that might interferewith a local labor force. High on the listis the use <strong>of</strong> helicopters, which sometimesis the only way to reach a site.“Blade hours are extremely expensive,”Patterson said. “If they’re sittingon the ground and not flying [due tobad weather], that’s a whole lot <strong>of</strong>money just to sit there.”Patterson also has tasking authorityunder U.S. Pacific Command to ask theservices for extra personnel, or augmentees,with specific skills—such asmedics and communications specialists—t<strong>of</strong>ill out the teams.Once an operation plan is finalized,further preparations and training are putin progress. Augmentees generally arerequired to undergo specialized trainingfor their roles.In the case <strong>of</strong> the 2002 Tibet mission,team leader Capt. Daniel Rouse createda strenuous physical training programto prepare all team members for thearduous expedition.For four months, according to Pokines,they’d start working out in pre-dawnhours with cardio exercises, weight trainingand swimming.“Those were the easy <strong>day</strong>s,” he said.On the hard <strong>day</strong>s, they made two- tothree-hour hikes with 80-lb. rucksacks upmountains on Oahu. In addition, teammembers performed high altitude trainingat 14,000 feet on Mauna Kea on theisland <strong>of</strong> Hawaii. They also spent time inAlaska at the Army’s Northern WarfareTraining Center where they learnedglacier and mountaineering techniques.A ‘Lewis and Clark Relationship’Two important roles on every team areplayed by the team and recovery leaders.An anthropologist from JPAC’s CentralIdentification Laboratory (CIL), likePokines, is designated as the recoveryleader and is in charge <strong>of</strong> the excavation.Team leaders play a more managerialrole.As team leader Air Force Capt. JuddStiglich put it: “It’s kind <strong>of</strong> like a ‘Lewisand Clark’ relationship between theanthro and the team leader. The anthrois in charge <strong>of</strong> the actual site, and theteam leader makes sure the team is onTeam members dig at a site in Kirchgandern, Germany, in August 2006, hoping to recoverremains <strong>of</strong> a P-51 pilot <strong>of</strong> the 368th Fighter Squadron whose plane crashed during a bombingrun in February 1945.STAFF SGT. VALDA G. WILSON / U.S. AIR FORCE PHOTOSeptember 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 11

site and equipped.”Army Capt. Jeremy Taylor, an IraqWar veteran who was a team leader on a2006 recovery mission in Laos, added:“When there are issues with host nationworkers, the team leader works withlocal <strong>of</strong>ficials to resolve the situation sowork can continue.”Navy Lt. Leslie Alexander, a pilot whoaccompanied Taylor in Laos to learnmore about the team leader role, told <strong>of</strong>a worker who had been injured when atall tree fell onto the site.“It was Taylor who called the detachment,got the medevac going and talkedto the pilot,” she said. Alexander willbecome the first Navy member to becomea team leader, as well as JPAC’s firstfemale team leader.While team leaders are crucial toensuring that the mission proceedswith as few setbacks as possible, recoveryleaders need a different skill set.According to anthropologist Dr. JohnByrd, the best background is experiencein both forensic anthropology andarchaeology.“The methods we use are a blend <strong>of</strong>crime scene and archaeological procedures,”said Byrd, who has been onmore than 25 missions since joiningJPAC in 1998.Earning his graduate degree in anthropologyfrom the University <strong>of</strong> Tennessee,Byrd had done numerous archaeologicalexcavations in North Carolina. His roommatefrom college, who later joined themilitary as a Special Forces medic, hadbeen part <strong>of</strong> several recovery missions.He convinced Byrd that he might find thework interesting—and rewarding.Byrd eventually joined JPAC. Afterbeing there only two <strong>day</strong>s, he wasordered to leave on a mission.“It was the ‘trial by fire’ method <strong>of</strong>orientation,” he said. “I didn’t evenunpack.”Not Like TV’s CSIOnce a team is on site, Byrd says he firstdecides how to excavate it and the methodshe’ll need to follow. As the excavationprogresses, it’s his responsibility toensure the work is done systematicallyEnsuring Safety in the Fieldand to high standards. CIL is an accreditedcrime laboratory and adheres tostrict guidelines as to how remains arehandled.Byrd, who refers to remains or artifactsas “evidence,” says there is a “protocolfor bagging and sealing it, just likean investigator would at a crime scene.”Part <strong>of</strong> the process involves initiating a“chain <strong>of</strong> custody” document. It accompaniesthe remains throughout theentire process <strong>of</strong> recovery, transportationand storage at the lab, until finalidentification is made and the remainsare transferred to the family.Writing the chain <strong>of</strong> custody documentsand keeping track <strong>of</strong> the remainsare tasks performed by the anthropologistlong after the work is finished at theend <strong>of</strong> each <strong>day</strong>.“The hardest thing to deal with is all <strong>of</strong>the little details,” Byrd said. “You have tomake sure all the bags are properlylabeled and sealed, and that all <strong>of</strong> theitems you’re bringing back are on thechain <strong>of</strong> custody document. It’s what TVContinued on page 13 ➲Medical expertise and reliable communications are twoabsolute necessities when teams are deep within a foreigncountry. A medic and communications specialist are part <strong>of</strong>nearly every mission. Above all, safety is the keyword.Since operations are overseas, regulations require thateveryone be treated as though they were heading to a warzone, according to Capt. Tom Hettich, who heads up themedic section. Medics run team members through a barrage<strong>of</strong> medical exams and screenings. Also, to avert problems inthe field, a psychological exam may be in order since a number<strong>of</strong> team members have served in the wars in Afghanistanand Iraq.“I’ve seen guys who have had signs <strong>of</strong> PTSD,” saidHettich, a 17-year Army veteran and Special Forces medic.“Our outfit includes Army mortuary affairs techs who dealtwith the dead, and they’re coming from Iraq, and some showproblems.”Prior to most missions, medics receive supplemental trainingabout diseases they might encounter in regions that havedifferent climates. For missions conducted at high altitudes,special equipment may be in order. Knowing how to use apressurized bag to counter a team member’s altitude sicknesswhile on a 14,000-ft. peak can avert a serious situation.Communication specialists have their own set <strong>of</strong> prioritiesimmediately after reaching a site. Before a mission can proceed,two communication requirements must be in place.The team must be able to contact Red Cross andInternational SOS (ISOS) for emergency help or medicalevacuation. With ISOS, a medic can speak directly to a medicalspecialist who can walk him through a procedure that isoutside his training.Host nations have restrictions, though, when it comes tocommunications equipment being brought into the country,especially in Southeast Asia. Requirements demand that allradio gear conform to their specifications—or it won’t beallowed.“Whenever we go to Communist countries, they actuallymonitor us so they know there’s no espionage or black opsgoing on,” said Air Force Tech Sgt. Andy Hurst. “All equipmentis listed on diplomatic notes as to whom we’re talkingto and how we’re talking to them.”Communications gear includes a variety <strong>of</strong> satellite radioequipment, both stationary and handheld. Some radios havedata and text messaging available. And for investigationteams that may track deep into a jungle, handheld units haveglobal positioning systems capability.Patrick Thompson, a Navy electrician tech who handledcommunications on several missions, two to remote areas inAlaska, finds the challenge <strong>of</strong> negotiating terrain and weatherhardly a factor when he considers the rewarding purpose<strong>of</strong> his work.“There’s no better job you can give me in the world,” hesaid.12 • VFW • September 2007

‘Every Day is Like Memorial Day’➲ Continued from page 12shows like CSI don’t capture—spendinghours in your hotel room filling outpaperwork.”Sometimes weeks can go by withoutany remains being found, and some missionscome up empty-handed, accordingto Alexander. But when a find does occur,excitement races through the entire site.“It’s always a huge morale boost whenyou find something,” she said. “Even ifit’s the last <strong>day</strong>, and all <strong>of</strong> a sudden—there’s a tooth in the screen. And withevery one, you can feel the site change.”Under rare circumstances, a veteranwith special information concerning anMIA can accompany a recovery teaminto the field. Byrd said that during thefall <strong>of</strong> 2006, a Korean War POW wentalong with his team into South Korea tosearch for the grave <strong>of</strong> a fellow POWwho had died during captivity.“We were out there excavating thesite with the veteran right there with uswhile we’re looking for his friend,” Byrdsaid. “He told us what happened tothem as POWs. It was a very rewardingexperience.”Of all the missions, Byrd said thatthose in North Korea were the most difficultdue to the authorities and therestrictions required <strong>of</strong> the team. In thespring <strong>of</strong> 2005, he was with a team excavatinga large site where soldiers <strong>of</strong> the3rd Bn., 8th Cav Regt., 1st Cav Div., hadmade a futile last stand resulting in severalhundred Americans killed.Unfortunately, North Korea has barredany missions since then. But Byrd saysthat JPAC is not giving up, and that“eventually we’ll get back to the site.”(North Korea handed over six sets <strong>of</strong>remains to JPAC in April 2007 as aresult <strong>of</strong> a U.S. diplomatic mission.)Hazardous DutySome missions can prove difficult duemore to the terrain than politics. During a1999 WWII recovery mission to IrianJaya, the country forming the westernportion <strong>of</strong> the island <strong>of</strong> New Guinea,Byrd’s team was working at a high altitudeto excavate a site where a B-25 hadcrashed with eight crew members aboard.“That site was at 13,000 feet,” Byrdsaid, adding that he had to learn how torappel. “The wrecked aircraft wasperched on the edge <strong>of</strong> a cliff, and wehad to be tied in to work there. One <strong>of</strong>the team members had altitude sicknessand went into shock.”Team members can be exposed to amultitude <strong>of</strong> dangers in and around asite. Typical <strong>of</strong> most missions, a workforce from the local population isemployed to do much <strong>of</strong> the digging.These willing workers provide anotherbenefit with their knowledge <strong>of</strong> the area’shazards, such as the treacherous “twostep”snake in Vietnam—a green pit viperso nicknamed because when it strikes,that’s as far as you get before you die.But a much larger threat is unexplodedordnance. Laos in particular has ahigh number <strong>of</strong> such explosives, makingmissions there especially dangerous.In fact, it’s estimated that 200 Laotiansare killed each year by ordnance leftover from the war.“During the first mission I was on,there was a bomb crater with two 2.75-inch rockets just lying there by our LZand work site,” Taylor said. The teamwas pulled back while the explosiveordnance disposal tech moved the rocketsto a safe area.Some missions test the mettle <strong>of</strong> teammembers more than others. During theTibet operation, team members did allthe digging because the site was in aremote area, far from any local population.As a result, fatigue hampered theteam, but taking a break was out <strong>of</strong> thequestion.“There was no point in giving anyonetime <strong>of</strong>f because all you could do was sitthere in your tent with wet clothing,”Pokines said. With the snow line movingfurther down the mountain each<strong>day</strong>, the team decided to push hard towrap up the mission as quickly as theycould, he said.Safety for team members is always atop concern (see sidebar), but tragediescan occur. On April 7, 2001, a helicoptertransporting team members crashed 280miles north <strong>of</strong> Hanoi. Seven Americansand nine Vietnamese were killed. Thegroup was an advance party investigatingpossible excavation sites. It’s a woundstill felt to<strong>day</strong> by those at JPAC.Rewarding WorkDespite long hours and sometimes livingout <strong>of</strong> a pup tent at a base camp, orputting up with rain that may last most <strong>of</strong>the <strong>day</strong>, team members find the workextremely rewarding. For Byrd, it was justas his Special Forces friend had suggested.“Every one <strong>of</strong> these cases involves astory about a serviceman who is missing,and there’s a reason why they’remissing,” he said. “And for every one <strong>of</strong>them, there’s someone out there whowonders what happened to him.”One <strong>of</strong> the air crewmen whoseremains Byrd had helped recover fromthe Irian Jaya mission turned out to befrom North Carolina. The airman’s sisterwrote to him after reading a localnewspaper account <strong>of</strong> the recovery forwhich Byrd was interviewed.“I still have the letter … it means a lotto me,” he said. “She wrote that peoplemight think that after 70 years we haveforgotten about them, but it was just asreal now as it was then. She said theynever stopped wondering what happenedto him, and if he was ever goingto come home.”For Taylor, doing his part to helpresolve the fate <strong>of</strong> MIAs helps him connectto men in his command who werekilled during his time in Iraq, as well asa classmate who died there.“My unit got back from Iraq in August2004,” he said. “I lost soldiers I commanded,and it means a lot to do thesemissions.”Alexander related her feelings aboutthe missions to her Navy aviation background.“Being a pilot, and my husband is apilot, and a lot <strong>of</strong> the people we’re lookingfor were air crew,” she said. “I wouldwant to know someone was looking forme, or my husband, as long as it took.And I think that’s awesome that we cando that for the families.”Stiglich says every <strong>day</strong> he wouldremind team members at a site whythey were there: “These guys we’re lookingfor have been laying there for 30 to40 years, and we’re only out here for 45<strong>day</strong>s. We owe it to them, and to theirfamilies.”Summing it up simply, he said: “Every<strong>day</strong> is like Memorial Day.” ✪PART IV (NOVEMBER): The Central IdentificationLaboratory and mtDNA.E-mail rwidener@vfw.orgSeptember 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 13

CIL and DNA:Last Leg <strong>of</strong> aJourney HomeWhen Dr. Robert Mannfirst came to the CentralIdentification Laboratory(CIL) in 1992, every <strong>day</strong> hehad to walk past a photo hanging in the hallwayleading to the lab. The photo was <strong>of</strong> a WWII serviceman’sskull that had a gold-capped tooth.“It’s like seeing a friend every <strong>day</strong> that youwalk by and notice,” said Mann, a Navy veteranwho is currently the deputy director <strong>of</strong> CIL withinthe Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command(JPAC) in Hawaii.The serviceman’s remains had been recoveredfrom a cemetery in Hungary. They werestored in a box in the lab because a lack <strong>of</strong> dentalrecords had so far kept his identity a mystery.“Each <strong>day</strong> I passed it, I wondered: ‘Whenwould he ever go home? What are we going todo to identify him?’ ” Mann recalled.The answer would not come for another 12years. A Hungarian researcher in 2003 forwardedinformation to JPAC that suggested a possibleidentity. A mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)sample was extracted from the remains andcompared to two known maternal relatives.In December 2004, the results confirmed thesuspected identity. The photo on the wall nowhad a name—Staff Sgt. Robert McKee, a B-24crewmember who had been reported missing inaction when his plane was shot down on Dec.17, 1944.Solving McKee’s 60-year-old case exemplifiesthe success that scientists at CIL achieve inidentifying about 100 MIAs each year. It’s a featattributable to the largest staff <strong>of</strong> forensicsanthropologists anywhere in the world. The scientists,together with modern advances inArmed with high-tech equipment and DNA analysis,the scientists at the Central Identification Laboratoryin Hawaii are unsurpassed in identifying MIAs.B Y R O B E R T W I D E N E RDr. Robert Mann, CIL’s deputy director, begins his examination <strong>of</strong> an airman’s bodythat was recovered encased in ice from the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Californiain 2005. The “Iceman” was later identified as WWII pilot Leo Mustonen.PHOTO BY STAFF SGT. DERRICK C. GOODE, USAF14 • VFW • November 2007

forensic DNA, give hope that America’sservicemen, who may have gone missingin action decades earlier, may at lastmake the journey home.Lab BackgroundCIL’s staff <strong>of</strong> 40 includes 30 anthropologistsand archaeologists who have anarsenal <strong>of</strong> high-tech equipment at theirdisposal. Over the years, they have pioneeredtechniques for determining age,race and sex that are used all over theworld. At the helm is Scientific DirectorDr. Thomas Holland, who began at thelab in 1992 as an anthropologist.“I have <strong>of</strong>ten said that I have thegreatest job in the world,” said Holland,who has supervised numerous MIAexcavations in China, Korea, SoutheastAsia and Iraq. “There is the intellectualsatisfaction <strong>of</strong> solving complex puzzlesfrom 30, 40 or 60 years ago, but therealso is the emotional satisfaction <strong>of</strong>doing a job that is almost sacred.”Unknown to most people, CIL is afull-fledged crime lab with accreditationfrom the American Society <strong>of</strong> CrimeLaboratory Directors, a prestigious<strong>recognition</strong> that took three years to gain.It requires the lab to adhere to strictguidelines in all aspects <strong>of</strong> its work.On occasion, CIL assists local, stateand federal authorities on cases. Theyalso played a role in identifying victims<strong>of</strong> the World Trade Center terroristattack <strong>of</strong> September 2001. Steppingoutside the world <strong>of</strong> military MIA identificationshas an important purpose,according to Mann.“We have to stay current in the forensiccommunity—with the police andmedical examiners,” he said. “If youonly look at dry bones that are 35 yearsold, you’re not going to be up on what’sbeing done in the mainstream.”CIL also has a fully-equipped autopsysuite that in 2005 aided in identifyingthe “Iceman,” a 22-year-old WWII pilotnamed Leo Mustonen. Mustonen’s AT-7 navigation plane disappeared in theSierra Nevada Mountains <strong>of</strong> Californiaduring a training mission on Nov. 18,1942. His well-preserved body, encasedin ice, was brought to the lab for examination.Still in his Army Air Forces uniformwith his parachute unopened, Mustonenhad died immediately, according toDr. Elias Kontanis, an anthropologist at CIL, reviews a report on an examination performed byanother <strong>of</strong> the lab’s anthropologist. Anywhere from seven to 10 people at the lab reviewfindings to ensure reliable data toward making an identification.Mann. In March 2006, the Brainerd,Minn., native finally was laid to rest.Multiple Lines <strong>of</strong> EvidenceA solemn quietness exists behind theglass wall <strong>of</strong> the lab’s examination roomwhere a number <strong>of</strong> skeletal remains arelaid out on tables. Anthropologists arebusy examining remains with little orno talk. It’s as though a respectful“moment <strong>of</strong> silence” is forever in the air.Family members <strong>of</strong> an MIA who visitthe facility are not allowed to enter theroom for fear <strong>of</strong> mixing their DNA withthe remains. In fact, thorough proceduresin handling and analyzing remainsare followed at every phase <strong>of</strong> the identificationprocess to ensure validity in thefinal analysis.The forensic anthropologist and dentistwho perform preliminary examinationswhen remains are first received atthe lab are excluded from doing theactual examination later on. Their mainpurpose is to prioritize the case.“They also assess if the bones aresturdy enough to obtain DNA, or if theteeth warrant a dental examination,”Mann explained.Once an examination begins, theanthropologist is not allowed access toany records to avoid skewing theresults. The dentist, on the other hand,works independently from a short list<strong>of</strong> dental records based on the locationwhere the remains were recovered.Their finished report is reviewed andcritiqued by seven to 10 anthropologists,some <strong>of</strong> whom compare the findingsto the remains.“You need to do a pretty thoroughjob because somebody is going to sitthere and read everything you did,”Mann pointed out.“They’re going to dotheir own comparisons and come upwith their own results.”Skeletal remains are not the only itemsconsidered in the final identification.“We use multiple lines <strong>of</strong> evidence toreach a conclusion,” Mann said. “Wedon’t just use the tooth, the bones orDNA. We also look at where the remainscame from … did they come from Laosor Vietnam?”Artifacts recovered along with remainsare important factors, too. In a case concludedin January 2007, the wallet <strong>of</strong>WWII soldier Harold Fechter, who wasreported missing on Oct. 3, 1944, nearMt. Battaglia in Italy, helped anthropologistsconfirm his identity. According toThe Kansas City Star, a plastic fragment<strong>of</strong> the wallet sleeve held the barely discernibleimage <strong>of</strong> a felt Catholic medallion.The image transfer had formed onthe sleeve over the six decades he hadPHOTO BY ROBERT WIDENER / VFWNovember 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 15

Family ReferenceSamples Are Needed“This country called, and they answered that call. This country sentthem into harm’s way, and many didn’t return. There is an underlyingnobleness in returning these men home that is reaffirming.”— Dr. Thomas Holland, scientific director, Central Identification LaboratoryProviding a DNA family referencesample tops the list <strong>of</strong> ways in whichyou can help the scientists at JPAC.Reference samples from Korean WarMIA family members especially areneeded. Another way to help is byorganizing a drive in your area tolocate MIA family members.To search a list <strong>of</strong> MIAs requiring afamily reference sample, go to:www.jpac.pacom.mil/FRS_public/FRS_public.aspx.If you feel you are a suitable donor,contact the appropriate servicecasualty <strong>of</strong>fice listed below.Air ForceUSAF Missing Persons BranchHQ AFPC/DPWCM550 C Street West, Suite 15Randolph AFB, TX 78150-47161-800-531-5501ArmyDepartment <strong>of</strong> the ArmyU.S. Army Human ResourcesCommandATTN: AHRC-PER200 Stovall StreetAlexandria, VA 22332-04821-800-892-2490Marine CorpsHeadquarters U.S. Marine CorpsMan<strong>pow</strong>er and Reserve AffairsPersonal and Family ReadinessDivision3280 Russell RoadQuantico, VA 22134-51031-800-847-1597NavyNavy Personnel CommandCasualty Assistance DivisionPOW/MIA Branch (PERS-624)5720 Integrity DriveMillington, TN 38055-62101-800-443-9298State DepartmentOverseas Citizens ServicesU.S. Department <strong>of</strong> State, 4th Floor2201 Pennsylvania Ave., NWWashington, DC 20037(202) 647-547016 • VFW • November 2007been missing.Analysts knew which soldiers were listedas missing in the area, and after examiningrecords, they discovered thatFechter was Catholic. CIL <strong>of</strong>ficials contactedfamily members for an mtDNAsample. The test results were conclusive—Sgt.Harold Fechter had been identified,and would finally come home.All final lab reports eventually end upon Holland’s desk, where he performsthe last review. He scrutinizes everypiece <strong>of</strong> evidence and weighs a verdicton the identification proposed by hisstaff—a responsibility he shoulderswith great concern.“While we can debate the rights andwrongs <strong>of</strong> war, what is not open todebate is what these young men did,”Holland said. “This country called, andthey answered that call. This countrysent them into harm’s way, and manydidn’t return. There is an underlyingnobleness in returning these men homethat is reaffirming.”DNA: The Key to a Cellular LockSo important is DNA analysis in the lab’sprocess that 78% <strong>of</strong> all identificationsinclude it. CIL’s anthropologists all agreeDNA is the single most important developmentin forensics in modern times.All DNA analysis is performed by theArmed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory(AFDIL) located in Rockville,Md. Results are forwarded to CIL.Two kinds <strong>of</strong> DNA are most important—nuclearDNA, which is locatedwithin the nucleus <strong>of</strong> the cell, andmtDNA, the genetic material that surroundsthe nucleus. A third type, yDNA,refers to the male chromosome and isused more in recent MIA cases.Nuclear DNA is an exact copy, butrequires a previous sample from the personin order to do a comparison.Scientists at AFDIL are able to extractDNA from saliva, hair, combs, rings, eyeglasses,toothbrushes and other personalitems. Current TV forensic crime showsare fashioned around nuclear DNA.MaternalGrandmotherAunt Mother UncleCousin Cousin Missing Sister Brother2nd Cousin 2nd Cousin Niece NephewGreatNieceGreatNephewOnly relatives along femaleblood lines can donate mtDNA samples.MtDNA, on the other hand, is passedon maternally from a mother to her children.Male mtDNA is destroyed duringegg fertilization, but female mtDNA survivesand mutates very little throughsuccessive generations, giving scientists areliable identification tool (see chart).“We try to determine if the mtDNAfrom the remains being examined arefrom the same matrilineal source,” saidDr. Elias Kontanis, an anthropologistand DNA expert at CIL. “If there are fiveor six differences in the DNA markersbetween the bone and the family sample,then they are not maternally related.”Using mtDNA is confounded, though,by the fact that 7% <strong>of</strong> all caucasians havethe same mtDNA, even though they arenot related. This aspect became a hurdlewhen scientists were trying to identifyJames McGovern, the CIA’s Civil AirTransport pilot who had been shot downin 1954 during the French-IndochinaWar. His remains were recovered in 2002.McGovern and another personContinued on page 17 ➲

CIL and DNA ➲ Continued from page 16aboard the aircraft shared the samemtDNA. Scientists used a complicatedanalysis involving several mtDNA samplesfrom female relatives, plus the DNA<strong>of</strong> a paternal nephew in order to confirmMcGovern’s identity. It was onlythe second time CIL had used paternalDNA in identification.“It was a very complicated geneticproblem to piece together McGovern’spr<strong>of</strong>ile from distant relatives,” Kontanissaid.In some cases, the nuclear DNA <strong>of</strong> amissing serviceman has fortunatelybeen available to compare directly tothe remains, according to Holland. Onecase depended on locating a DNA samplefrom the family. But the servicemanhad been adopted at birth, and his biologicalparents were unknown.“What seemed like an impossiblecase was finally resolved by obtainingan aged envelope in the possession <strong>of</strong>the man’s widow,” Holland said. “It hadbeen handed down to her from theadoptive mother.”Inside the envelope was a lock <strong>of</strong> hairfrom his first haircut. It provided theDNA necessary to confirm his identity.“In another case, we obtained a DNAsample from the envelopes <strong>of</strong> love letterswritten by the serviceman to hiswife 40 years ago,” Holland said.“It is somehow fitting and completethat what began as an act <strong>of</strong> love andtenderness—the snipping <strong>of</strong> a baby’sfirst lock <strong>of</strong> hair or the expression <strong>of</strong>longing a fidelity—should be the key tobinding up the unhealed wounds <strong>of</strong>war,” he said. “Those are the cases thatchange you.”As much as DNA’s role in MIA caseshas had great success, it also has led togreat controversy. In 1998, the remains<strong>of</strong> Lt. Michael Blassie grabbed nationalheadlines. Blassie, an Air Force pilot lostduring the Vietnam War, was thought tobe the Vietnam War’s Unknown Soldierwithin the Tomb <strong>of</strong> the Unknowns.Enough artifact and record evidenceexisted, along with the availability <strong>of</strong> afamily mtDNA reference sample, t<strong>of</strong>orce the Department <strong>of</strong> Defense toexhume the remains and perform a test.The results confirmed that the remainsindeed belonged to Blassie.The case set a precedent, leaving Vietnamvets in a vacuum: How could anyset <strong>of</strong> remains ever fill the UnknownSoldier space when some evidence mightsurface later enabling identification?‘No Longer a Name in a Book’One thing is evident in identifyingMIAs—the DNA <strong>of</strong> family members cangreatly aid in identification. Presently, anumber <strong>of</strong> unidentifiable remains arestored at CIL, due partly to the lack <strong>of</strong>adequate family reference samples. Sgt.Robert McKee would still be a namelessphoto on the wall had a reference samplenot been available.And male contributions are not out<strong>of</strong> the question.“The technology is advancing to thepoint where we will be using nuclearDNA from paternal descendants in thefuture,” Kontanis said. “All we had beendoing in the past is looking for maternalreference samples, but now, sciencebroadens our scope <strong>of</strong> it.”As for the lab, Holland sees it as anational resource that some<strong>day</strong> couldbe expanded.“What it does, the capabilities it has,and the research it advances, have thepotential to pay substantial dividends tothe people <strong>of</strong> this country—regardless <strong>of</strong>whether or not you have a family membermissing from a past war,” he said. “Into<strong>day</strong>’s world, with our global war on terrorand the concerns for homelanddefense, the laboratory has the realpotential to be a tool <strong>of</strong> national scale.”For Kontanis, solving a decades-oldcase is an amazing process <strong>of</strong> watchingall <strong>of</strong> the lines <strong>of</strong> evidence fall in place.“It gives you a good feeling when itall comes together to produce an identificationso that somebody can go hometo his family,” he said.Mann agrees and adds that his workat CIL is “his way <strong>of</strong> contributing to thepeople who went <strong>of</strong>f to war and didn’tcome back.“Once you work a case, you get to seewhat his photo looks like, or you get tomeet his wife,” he said. “It really bringsthe humanity into it, and it’s no longera name in a book.”Or, a nameless photo on the wall. ✪PART V (JANUARY): Families <strong>of</strong> MIAsE-mail rwidener@vfw.orgNovember 2007 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 17

Families <strong>of</strong> MIAs:Keeping the Candle <strong>of</strong>Hope BurningFamilies <strong>of</strong> MIAs are on a quest for answersthat can lead to closure. But in some cases, itraises even more questions. Beyond a doubt,the loss felt by the family is everlasting.B Y R O B E R T W I D E N E RAt night after her children were put to bed, SharonTaylor would read one <strong>of</strong> the hundreds <strong>of</strong> loveletters her father, 1st Lt. Shannon Estill, hadwritten to her mother during WWII. Shesavored each one, hoping to understand a father she neverknew.“I was three weeks old when he was killed,” said Taylor. “Idon’t remember a time when my mother and grandparentsdidn’t talk about him. I knew the story.”Estill’s P-38 Lightning fighter was struck by anti-aircraftfire while attacking targets in eastern Germany on April 13,1945, just a few weeks before the war ended in Europe. Butbecause the crash site was within the Russian-controlled sector<strong>of</strong> occupied Germany, U.S. military personnel could notrecover the 22-year-old’s remains after the war.“No one knew for sure what happened to him,” Taylor said,“so there was that lingering overlay that he would show upbecause some men did after the war. It was always an unspokenpossibility.”For as many MIAs still unaccounted for to<strong>day</strong>, there are asimilar number <strong>of</strong> families just like Taylor’s seeking answers.Tasked with fulfilling that mission is the Joint POW/MIAAccounting Command (JPAC) in Hawaii and the DefensePOW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) in Washington, D.C.Through these agencies’ combined efforts, wives, mothers,brothers and sisters come closer to knowing the fate <strong>of</strong> theirmissing loved ones. Some families are fortunate to find resolutionwhen identifications are made. But others must keepLove letters from Sharon Taylor’s father, 1st Lt. Shannon Estill, toher mother during WWII took her on a quest to resolve his fate.Her effort led to the discovery <strong>of</strong> his crash site in 2003.the candle <strong>of</strong> hope burning for answers that may never come.Love Letters Initiate a QuestThe letters from Taylor’s father became her only tangible linkto him over the years. In the course <strong>of</strong> reading them, Taylorcame across the names <strong>of</strong> his crewmembers. In the early1990s, she tracked down her father’s crew chief, Henry“IN MY THOUGHTS” PAINTING BY JAMES B. HARTEL18 • VFW • Frbruary February 2008

Hamm, who told stories about herfather during their service together. Theexperience sparked the thought thatwith further research, she might findclues to his crash site.“I always did everything on my own,”said Taylor. “I pieced together everythingbecause that’s the way I operate. Itwas a process that I had to do myself.”Hamm provided Taylor with thename <strong>of</strong> a German WWII researcher,Hans Guenther Ploes, who also was anexpert on WWII crash sites. Taylor traveledto Germany in 2001 and met withPloes who took up her quest. In 2003,when examining a possible crash site ina farmer’s field near Elsnig, Germany,Ploes discovered an aircraft part thatmatched her father’s P-38. Humanremains also were found.With such strong physical evidenceand Taylor’s research, JPAC sent a recoveryteam to the site in August 2005.Taylor was allowed to join the teambecause <strong>of</strong> her relations with the Germangovernment over the years and her overwhelmingdrive to find her father.“I spoke to team members the first <strong>day</strong>and said ‘I’m here to do whatever I can,’ ”she said.“They loved that and handed mea shovel and said ‘Here you go.’ ”She had special caps made for eachmember along with a flag that was postedat the site each <strong>day</strong>. The caps and flagread “Team Estill.” She also gave a photo<strong>of</strong> her father to each <strong>of</strong> them.The team had two items it hoped torecover—Estill’s dog tags and a babyshoe.“My father carried one <strong>of</strong> my babyshoes in his plane,” Taylor said. “Theteam started to get emotionally upsetthat they couldn’t find it for me.” Despitetheir efforts, neither item was found.JPAC’s Central Identification Labidentified remains from the recovery asEstill’s in 2006. He was buried in ArlingtonNational Cemetery that October.Closure, however, is not a wordTaylor uses to describe the end result.“I don’t think that circle ever closestotally,” she said. “You always have yourmissing dad. When you’re sitting inyour house and it’s all over, and everythingis in boxes or files, it feels thesame—except you know more.”Capt. Charles J. Scharf went missing inaction in 1965 during the Vietnam War.Love Letters Provide Final Pro<strong>of</strong>“May<strong>day</strong>, May<strong>day</strong>, May<strong>day</strong>!” came thetransmission from the F4C Phantom IIin flames. Piloted by Capt. Charles J.Scharf and co-pilot 1st Lt. Martin J.Massucci, the jet had been hit by antiaircraftfire on Oct. 1, 1965, while on areconnaissance mission over Son Laprovince, North Vietnam.Squadron members remember seeingonly one chute, later determined tobe a drag chute, before the planecrashed. No further contact with thedowned pilots occurred, even thoughsearch efforts were made that <strong>day</strong> andafterward. Scharf and Massucci hadsimply vanished.“I hoped that he was alive,” said hiswife, Patricia, when she heard about thePHOTO COURTESY PATRICIA SCHARFshootdown. “He was a survivor, ahunter and a fisherman. And I justcouldn’t conceive that he would go.”When he was not among the POWsrepatriated at the war’s end, doubt <strong>of</strong> herhusband’s survival loomed for Scharf.She took solace from the hundreds <strong>of</strong>love letters he had sent her. They hadsometimes arrived two or three at atime. He wrote <strong>of</strong> a new life for the two<strong>of</strong> them, especially about starting a familywhen his military service was over.The pair had met when they were 16,and married at 18. During their 11-yearmarriage, they had one baby girl, butshe had died shortly after childbirth.JPAC sent three recovery teams to thesite between 1992 and 2004 that yieldedhuman remains and other artifactsindicating Scharf had been found.Among the recovered items was aCatholic scapular, a religious cloth.“We were married in 1953, and thepriest gave each <strong>of</strong> us one at the altar,”said Scharf. “Chuck carried his in hiswallet.”That particular scapular was uniqueto the time period and helped to provideone layer <strong>of</strong> confirmation. Positiveidentification was hampered, though,when a mitochondrial DNA samplefrom one <strong>of</strong> Scharf’s maternal relativescame back inconclusive. The scientiststhen approached Scharf for any personalitems she may still have <strong>of</strong> his.“I said ‘How about the envelopesfrom the love letters he had sent me?’ ”she said.“I had a box full <strong>of</strong> them.”The experts at the Armed ForcesDNA Identification Laboratory wereable to extract DNA from the saliva onthe stamps and envelopes Scharf hadlicked. It was the pro<strong>of</strong> they needed.“When I got the word that Chuckhad been identified, I had great relief,”said Scharf, “because in the back <strong>of</strong> mymind, I knew he never suffered.”Scharf visited JPAC in October 2006to claim her husband’s remains. In achapel at the facility, she had time to bealone with the casket.“He was buried with a new uniformand his medals,” she said. “Inside thecasket I placed a few <strong>of</strong> the love letters, anote from me and a picture <strong>of</strong> when wewere last together in Hawaii.”Her trip took another emotional turnwhen traveling back to Virginia. Theplane landed in Texas, but before passengerswere allowed to leave, the stewardessannounced that they werebringing back the remains <strong>of</strong> a VietnamWar MIA. The passengers listened quietly,and then applauded. That’s whenthe stewardess pointed out Scharf, whostood and spoke to them.“I am so honored that you feel proudthat you have men fighting for you,” shetold them. “And we do bring back ourFebruary 2008 • WWW.VFW.ORG • 19

men. There will be other men broughtback and please honor this. They arethere so that we can sleep at night andbe at peace.”DPMO’s Family Update ProgramA large number <strong>of</strong> families are not asfortunate as those <strong>of</strong> Taylor and Scharf.For them, the answers will be a lifetimein coming, if at all. In order to keepthem apprised <strong>of</strong> developments, DPMOhas hosted briefings for family memberssince 1995.Annually, eight such gatherings areconducted in cities across the U.S., andtwo in Washington, D.C. They affordthe families an opportunity to hearfirsthand from representatives <strong>of</strong>Department <strong>of</strong> Defense agencies andthe service casualty <strong>of</strong>fices involved inthe MIA effort.Helen Famuliner, a VFW LadiesAuxiliary member, attended one <strong>of</strong> themeetings in Kansas City in August2007. She had questions concerning herfirst husband, Pfc. Ralph K. King. The24-year-old was reported missing duringthe Korean War when he and anothersoldier were helping a woundedbuddy back to their lines. None <strong>of</strong> themmade it back, though.“They found no trace <strong>of</strong> my husbandor his equipment, so I was led to believehe was taken prisoner,” said Famuliner.She found out in 1998 that the woundedsoldier her husband had helped wasa POW repatriated at the war’s end.“I didn’t get to talk to him because Ididn’t learn about the details until afterhe had died,” she said.King’s brother, Don, along with nineother family members, also attendedthe update program. Several <strong>of</strong> King’schildren are interested in continuing toseek answers because King was lost inNorth Korea, which has barred MIAsearches since 2005.King says the update program “givessome hope that some<strong>day</strong> they mightfind him.”Thomas Klingner, also at the KansasCity meeting, keeps hope, too, thatsome<strong>day</strong> they’ll find his brother, Capt.Michael Klingner, an F-100 jet pilot. Hewas shot down over Laos on April 6,1970.“Other people don’t come back—butnot my brother,” said Klingner.JPAC has been to Klingner’s crashsite several times, but other than hisidentification card, no remains werefound. His blood chit, an aviator’s personalinformation scarf, curiouslyturned up in Vietnam’s Hue MilitaryMuseum in 1992. Officials there, however,are not cooperating.According to the deputy assistant secretary<strong>of</strong> Defense, DPMO, AmbassadorCharles Ray, the family update programsare “a creation <strong>of</strong> the desire <strong>of</strong>people in America to have answers.“The one thing that might not seemobvious to people is despite how longago a loss took place,” Ray said, “theemotion and sense <strong>of</strong> loss is greaterwith the passage <strong>of</strong> time when theydon’t have answers.“It’s important for those who don’thave missing family members to understandthe importance <strong>of</strong> this mission.The freedoms that we enjoy and take forgranted were built on the sacrifices <strong>of</strong>these men and women. Our freedomswere paid for in blood.”✪E-mail rwidener@vfw.org20 • VFW • Frbruary February 2008