bruce munday - Wakefield Press

bruce munday - Wakefield Press

bruce munday - Wakefield Press

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

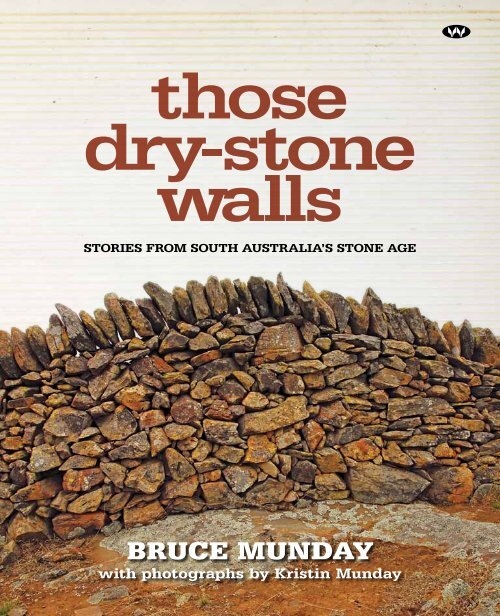

stories from south australia’s stone age<strong>bruce</strong> <strong>munday</strong>with photographs by Kristin Munday

Bruce Munday grew up in Geelong with a burning ambition to play football for his beloved Cats.When that was not going to happen, he completed a PhD in physics and then spent four yearsresearching the magnetoelastic properties of antiferromagnetic materials. Alas, he found that hispenchant for the esoteric cut him off from many of his friends. So he moved into teaching where hehad a captive audience.In 1974 he and Kristin Munday bought a farm in the Adelaide Hills. There they raised sheep,cattle and three children, and planted many trees. When the kids left home Bruce established hisown business as a communications consultant in natural resource management and discovered howmuch he enjoyed sharing stories with people living on the land – particularly those who love the landand want to conserve it.Kristin grew up in Melbourne lacking any ambition to play football but with an abiding passionfor photography.

Netherford, Pine Hut RoadFor Kim Mitchell and David Phelps,country boys at heart who departed far too soon.

thosedry-stonewallsstories from south australia’sstone age<strong>bruce</strong> <strong>munday</strong>with photographs by Kristin Munday

<strong>Wakefield</strong> <strong>Press</strong>1 The Parade WestKent TownSouth Australia 5067www.wakefieldpress.com.auFirst published 2012Copyright © Bruce Munday, 2012All photographs by Kristin Munday except where indicatedAll rights reserved. This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research,criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced without written permission.Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher.Edited by Julia Beaven, <strong>Wakefield</strong> <strong>Press</strong>Designed by Mark ThomasPrinted in China through Red Planet Print ManagementNational Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entryAuthor:Munday, Bruce.Title:Those dry-stone walls: stories from South Australia’s stone age / Bruce Munday;photographs by Kristin Munday.ISBN:978 1 74305 125 2 (pbk.).Notes:Includes bibliographical references and index.Subjects:Dry stone walls.Stone walls.Dry stone walls--South Australia--Photographs.Stone walls--South Australia--Photographs.Dry stone walls--Design and construction.Stone walls--Design and construction.Other Authors/Contributors: Munday, KristinDewey Number: 693.1

ContentsAcknowledgements . ................................................................... viMap.................................................................... viiForeword ..................................................................... 1Preface ..................................................................... 2Chapter One Stones in the blood ................................................. 4Chapter Two Stone also rises in the east ......................................... 14Chapter Three The other side of the Hills ..........................................42Chapter Four Heading north .....................................................54Chapter Five Over ‘The Line’ ....................................................80Chapter Six Why SA beer is best ............................................... 92Chapter Seven A long way from anywhere ........................................ 102Chapter Eight The deep south ................................................... 112Chapter Nine Across the passage ............................................... 124Chapter Ten Walls across ages and stages ...................................... 132Chapter Eleven Getting stone ..................................................... 150Chapter Twelve Doing walls ...................................................... 158Chapter Thirteen So, you want to build a wall! ...................................... 168References ................................................................... 178Glossary ................................................................... 180Index ................................................................... 182

AcknowledgementsWe could fill chapters thanking people who helped with this book. Those who showed us walls,pointed us towards other walls, lent books, sent history and photos, interpreted geology,commented on early drafts or shared their ideas.Rather than write another chapter, we will thank Bryan Edwards for his inexhaustible andfascinating knowledge of the Mid-North, so generously given; Bill Nosworthy Snr for sharing not onlyhis great knowledge of West Coast walls but also his wise observations on history, development andnature; and the Keynes family for the loan of Joseph Keynes’ wonderful journals which really set thetone for this book.To all the others, we trust that this book is some reward for your invaluable support.vi

south australiaregion 1region 2region 3region 4region 5region 6region 7region 8Stone also rises in the eastThe other side of the HillsHeading northOver ‘The Line’Why SA beer is bestA long way from anywhereThe deep southAcross the passageGoyder’s Line4Port Augusta63BurraRiver MurrayPort Lincoln5MaitlandAdelaide21Murray Bridge8KingscoteKingston7Mount GambierMap not to scalevii

Old sheep dipping yards, Rosebank, Mount Pleasant

ForewordThose Dry-stone Walls: Stories from South Australia’s Stone Age is not only a poem to the beautyand craft of stone walls, but will persuade many readers to become interested in this importantpart of South Australian heritage.In a fascinating journey around dry-stone walls and other stonework throughout the State, andthrough their engaging text and superb photography, Bruce and Kristin Munday will help othersdiscover new delights (as well as, perhaps, renew old acquaintances).Dry-stone walls are a previously unsung, little researched heritage and this important bookrecognises and describes them from a range of angles. For many the book will form the basis for anew exploration of the countryside, opening up a fresh perspective on what was previously thoughtto be familiar.An important feature of the book is the attention to relatively recent stone walls as well as historicmasterpieces, underlining that this is very much a living heritage that continues to the present. Indeedthe early impetus for dry-stone walls (readily available local stone as a cheap building and fencingmaterial) echoes contemporary concerns for ecological sustainability, where use of local materialscreates lower environmental impacts. Even the lack of mortar is more ecologically sustainable thanthe later high-energy, high-carbon-footprint use of cement.Although the identity of the stone wall builders is poorly known, the book includes informationand insights about some and its discussion of construction brings the walls to life as never before.The importance of stonework to the physical identity of South Australia’s built heritage has longbeen noted – as the Mundays reveal, in 1911 sixty-two per cent of South Australian houses werestone compared to eight per cent nationally. Now we can confidently add dry-stone walls, as thedetailed record of this book shows.Above all, the author’s passion for the walls is infectious, and stories of bulldozed, deterioratingor pillaged walls will stir preservationist instincts.David BeaumontPresident, National Trust of South Australia1

prefaceMy affair with stone walls started way back as a kid growing up in Geelong. The old GeelongGaol, quite an elegant building in its grim and gruesome way, is now heritage listed. WhatI vividly recall of that gaol was feeling reassured by the immense stack of bluestone between meand all manner of evil.I don’t know why convicts loomed large in my life, there being no family connection to that part ofAustralia’s history. But we did have connections with the Western District of Victoria and I was wellacquainted with the miles of dry-stone wall stretching out over the Stony Rises. Like many kids ofmy generation I grew up believing these walls were built by convicts. At the time my preoccupationwas not with the Herculean effort and the classical skill that these walls represented. It was with theimage of unshaven men in navy blue and white hoops stacking stones while towing ball and chainunder the watchful gaze of stern guards.So it was with a tinge of disillusionment that I read recently that convicts were not at all involvedin the building of those walls. Maybe freed ex-convicts contributed some of the labour, but moregenerally those walls were crafted by Scottish and Irish tradesmen, often brought out to Australiafor that very purpose. 1In Peru in 2006, like everyone who goes there, I pondered the amazing stone engineering andarchitectural feats of the Incas. Not just how they did it, but what must life have been like back then?What were they thinking? Was it fun or agony, satisfying or mundane? In the absence of a writtenlanguage, we are left pondering.While South Australia’s dry-stone walls are in a lesser league than those of the Inca, there is stilla case for the written word and photography to record and enhance this wonderful heritage. And yetmentioning to a friend that I was writing a book on dry-stone walls in South Australia, she burst intohysterical laughter. Wiping away the tears she spluttered, ‘I’m sure it will be a lot of fun.’I am not a historian, so a definitive history of walls in South Australia is beyond me. Nor am I ananthropologist, geographer, town planner, mason or engineer. I am a farmer with a lot of rock thatI like playing with – Kristin, my wife, says it’s an obsession, and I do confess to becoming somethingof a ‘wall spotter’. I also love seeing what other people have done with stone, marvelling at theenormity, durability, craftsmanship and diversity of their creations. And what I discovered exploring2 THOSE DRY-STONE WALLS

these marvels is the great depth of feeling others have for ‘their walls’. And what I also learned, butshould have known, is that I love hearing their stories and telling them mine.Kristin and I started our quest thinking we knew where the most interesting and worthwhilewalls would be found. The stone fences in the Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges are historic, photogenic,accessible, and in many instances still in excellent condition. And we knew several of the currentowners. But as we travelled and talked to people − ‘Have you seen those walls on . . .’ and ‘You musttalk to . . .’ − new chapters kept presenting. Not only were there walls where we would never haveexpected, they were different in style and history and unmistakably important to the locals.So this book is not an inventory of walls, region-by-region or era-by-era or style-by-style. Nor is ita ‘how to’ manual, notwithstanding a final chapter diarising the author’s own experiences buildingdry-stone walls that may help guide the enthusiast. It is about a journey that took us to placesin South Australia we had never dreamt of, discovering walls and often unearthing a fascinatinghistory behind them. It is about the people we met as we travelled, about the tales they shared withus and the leads they gave us. But perhaps, more than anything else, it is about the value peopleattach to their unique heritage, to those stone walls. The book has alloyed all these ingredients and,as with the alchemist, I hope we have produced something that becomes greater than just the sumof the parts.Bruce Munday, 20123

4Once reached the end of the rainbow

Chapter onestones in thebloodThe style of construction of the wall has provided us withan aesthetic form, as in country crafts, generally, that hasits roots in practicality: the wall as a functional work ofart. Inherent knowledge of how best to build, to withstandstorms, has dictated the manner in which stones arechosen, laid and the wall intermittently strengthened.G. D’Arcy, The Burren Wall5

Walls and fences mark and defend boundaries. Before white man arrived there was no needfor fences as there was little sense of property ownership among Aboriginal communities,although the very first stone walls were indeed built by Aboriginals as fish traps along the SouthAustralian coast, the Coorong and the Lower Lakes.As the early pastoralists pushed out into the unknown, stock never moved far from availablewater and was tended by shepherds. But when the vast pastoral runs were broken up for farming andshepherds saw a better life calling on the Victorian goldfields, the fence soon became a consuminginterest.Rural fences in the mid-nineteenth century were about function and cost. I have read nothingto suggest that there was any sense of aesthetic value attached to post-and-rail fences built fromhand-split and adzed posts, or stone walls meticulously assembled from odd-shaped rocks. Very fewpost-and-rail fences have survived 150 or so years of fire, termites and rot, but we still have hundredsof kilometres of stone walling for various purposes and in various styles and materials. Many arebeautiful, most are heroic, and all tell us something about lives lived before ours.And yet not all find a stone wall compelling. It was about 1976 that my then neighbour with hisfront-end loader pushed down the stone wall that had fenced the eastern side of his property. WhenI asked him why, he explained to me something that I had already noticed: ‘It is old.’ But that is oneof the few sad stories in this adventure. Most of the tales are warm and uplifting. Sure, you see somewalls tumbling down through neglect, but that is just the Law of Entropy at work – there is in naturean inevitable and overwhelming tendency towards disorder.And talking of nature, it short-changed South Australia in terms of forests for building timber andat the same time over endowed us with white ants. But we are blessed with beautiful stone. * Stonewith colour, texture and light. We have a wonderful heritage of stone buildings from the simplestshepherds’ huts to grand churches and halls. † At the 1911 census sixty-two per cent of SA homeswere of stone compared with eight per cent nationally. About the only conventional stone buildinglacking was a fortress.But what of the stories behind those walls? Even the simplest man-made forms give us a glimpseof early European settlement here, while their durability states the obvious about the material andunderlines the skill and toil of our forebears. Yet there is seldom mention of South Australian stonewalls in the national conversation – further evidence that the history of Australia was largely writtenin the Eastern States.Even in SA, it is hard to come by historical mentions of dry-stone walls. ‡ Reading about earlysettlement, even where miles and miles of walls were being built, you get the impression that thiswas pretty hum-drum stuff – just putting up fences, hardly worth mentioning. At Kanyaka Station* A summary of South Australian building stone is available on CD-ROM from PIRSA: Hough J. (2006) South Australian Dimension Stone,Primary Industries and Resources SA.† The SA Government’s SAmemory website is being a bit coy when it can only claim that ‘South Australia is noted for the use of corrugatediron, for underground houses at Coober Pedy, and for Adelaide lace decorative cast iron on verandas’.‡ The encyclopaedic Pastoral Pioneers of South Australia by Rodney Cockburn published in 1926 provides comprehensive biographicalaccounts of 230 significant figures of the era. Despite numerous indexed references to fences and fencing there is nothing but the briefestreference to stone walls, walling or wallers.6 THOSE DRY-STONE WALLS

stones in the bloodin the southern Flinders Ranges, where many miles of fence were supposedly built by a man withone arm and an Aboriginal woman assistant, about the only source of such ‘knowledge’ is over thecounter at the Hawker Mobil servo.Angus McLachlan lamented to me the greatest mistake he made when he took over runningRosebank Station in the Adelaide Hills in 1970: ‘I didn’t take the time to sit down and talk to theoverseer who had been here for over fifty years, and whose father, Levi Meakins, had built many ofthe wonderful walls throughout the district.’Now I have a dilemma – when is a stone wall really dry-stone? Obviously when no mortar was used.But what about when the mortar was nothing but mud that has eroded away over the years?This book is mainly about the walls that spent their life untouched by mortar. But it does includesome walls that have shed their mortar and impress us because of their history, endurance, beautyor some other compelling attribute.When is a dry-stone wallreally dry?For me a dry-stone wall is when it has no mortar.But Kristin, the photographer, squirms at this andannounces, ‘It must never have had mortar.’ Onthe one hand Kristin says I am snobbish aboutdry-stone walls being special, but then she wantsto disqualify some of the finest old walls inthe State.It seems that I have won this debate as I amwriting about anything that is now dry-stone andshe is shooting them. In fact we have relaxed the criteria further. It is dry-stone for the purpose of thisbook if it now looks dry-stone from all sides. The only mortar used was mud that has weathered awaycompletely or is of the same parent material as the stone and what little remains is barely noticeableto all but the most forensic eye. In fact, you could persuade a sceptic that it is dust that blew in there!We have found some wonderful walls, mainly on shepherds’ huts, stables, stalls and sheds whichwere exposed to the elements when the roof blew off and now show no evidence at all of mortar oneither side. Is it cheating to say that these have defaulted to dry-stone? It means of course that manyruins, particularly in the pastoral country, will now be classified as dry-stone.I built a stone wall at the end of our driveway in 2006. Travelling the State and seeing what othershave done is uplifting but on reflection can be quite depressing. One day I said to Kristin, ‘Our wallhas too many holes I can see light through. Maybe I should knock it down and start again?’7

‘No you won’t!’ she said. ‘That was your practice wall. If you think you can now do better, buildanother one.’It is difficult to appreciate dry-stone walls until you have built at least one. An eye for a nice stonein the paddock, the satisfaction in unearthing a mini-quarry, the grunt of lifting and placing, the Zento accept that this hard-won piece really won’t do and to replace it with another, * and admiration forother works. These are all part of the love affair with stone.At the end of your first day of wall building – lifting rock, twisting vertebrae, crushing fingers –you survey your efforts and despair: ‘Is this all I’ve done?’ But day one is nothing. Day two your handsare sore, week two you walk with a stoop and you might be thinking, This is bad for my health.Of the many folk who have helped me gather material for this book, those most switched on havealready built a wall or two, restored a wall, or at least attempted one of the above. Walling really isabout learning on the job. Stones are not bricks, no two are the same and no one stone looks the samefrom every angle. Nor are all wallers the same, but the one thing most have in common is that theyare short people. They might not have started short, but that’s how they finish. †There is lots of stone where we have lived these past thirty-eight years. The Kanmantoo Systemis a band of schist outcropping across the Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges from about Wistow throughHarrogate, Tungkillo, Springton and Keyneton to Truro. The rock is a host to lichen and the combinedproduct has earned some fame (or notoriety) as ‘moss rock’ that is used and abused as a landscapingfeature in mainly newer suburbs of Adelaide.One-hundred-and-fifty years ago much of this stone was used to build the first dwellings, shedsand fences throughout the district, simultaneously providing shelter and containment whilst clearingthe land of some of the obstacles to farming. Many of the structures are still in use today, providingenduring insights to lives of the early settlers and at the same time displaying the marvellous stonearchitecture that so characterises much of South Australia.We bought Dairy Springs, about midway between Mount Torrens, Tungkillo and Harrogate, in1974; or at least we bought part of it. In those days we could not afford the eastern-most sectionwhich had about a kilometre of stone wall. To be honest the wall didn’t mean much to us back then.But we did think the stone buildings looked pretty, salt damp and all.The core of our house was four rooms built from local stone, while out the back was a two-room(three if you count the loft) stone cottage from which operations commenced in 1896. Over the years,functional but ugly extensions were grafted on and the verandah bricked in to make another room.We had the sense that stone was very much a part of this place but that it was unloved. As everyposthole I dug hit rock, and too often my ute would hit one in the paddock, I could understand howthe early settlers might have had a jaundiced relationship with the local stone.Time passes and one finds use for what is at hand. Flagstones carted back from the paddockscreated paths where needed – and after a while, where not really needed, supply exceeding demand.* Something no serious waller would contemplate – the craftsman, having picked up a stone will not put it down until a place for it is foundin the wall.† A notable exception is the almost legendary Scott Wilson on Kangaroo Island. At six foot five inches in the old money, Scott has such aniconic Aussie style about him that I suspect he will somehow continue to defy gravity where so many before him have failed.8 THOSE DRY-STONE WALLS

stones in the bloodWhen we built a verandah on two sides of the house we were getting serious with stone. Then camea wall around a courtyard and another at the end of the driveway. And now I find myself writing abook about it, during the course of which I have built two more dry-stone walls!There are turning points in life and I found one at the end of our driveway on Collins Road. Therewas an old bridge, hand-made in 1906 by first settler Horace Collins. Sure, the bridge had becomeunsafe for traffic heavier than a car and was complemented with a concrete box culvert when theroad was realigned in 1975. But the bridge with its four red gum trunk bearers, red gum decking andimpressive stone wall abutment was an irreplaceable monument; a reminder of the skill and hardwork that got us to where we are today. So when I came home one afternoon to find workmen fromMount Pleasant District Council burning the decking in the creek, presumably a first step to furtherpillage, my preservationist instinct suddenly kicked in, intensified when my neighbour bowled overhis section of the stone wall.The earliest mention I can find of ‘our’ stone wall next door is in Ron Collins’ unpublished‘Recollections’, writing in 1922: ‘I went with my father [Horace] to set some rabbit traps . . . near thestone wall fence.’ Ron’s brother, Hartley, alert at ninety-four, swears that ‘the wall was there whenI was born’.‘Our’ stone wall, next door

Before fences – shepherdsAny party in want of a shepherd who holds good testimonials of character and has had twelveyears experience in the employment of one of the most extensive Sheep farmers in Scotland,may have the immediate services of the advertiser by applying at the Immigration depot onMonday next or the following days. – Register, 16 May 1840European conquest of much of South Australia was rooted in the principle of ‘first in best dressed’.Vast pastoral runs based on occupational licences were set up by men with vision for what mightbe and with the capital to stock them.Until the 1850s there were few fences on the pastoral runs; livestock was controlled by shepherdsand boundary riders. By the early 1850s Bungaree Station north of Clare had fifty-two shepherds forapproximately 100,000 sheep. The going rate was between ten and fifteen shillings per week withouta hut keeper, along with weekly rations of meat, flour, sugar, and tea.Shepherding was generally near the bottom of the vocational ladder, shepherds in some regionsearning little more than their keep and their abode reflecting their low station. Responding to anassertion that shepherds were getting a bit cheeky seeking a pay rise to above fifteen shillings aweek, a correspondent defended the claim in the Adelaide Observer, noting that shepherds weresometimes referred to as ‘hutters’:He takes charge of a flock of sheep day and night, living by himself, cooking for himself, infact living – no, existing – like a hermit, seldom seeing any of his race or colour. His lodgingsconsist of anything in the shape of a hut, and his ‘board’ shepherd’s rations, viz. flour, meat,tea and sugar – ‘only this and nothing more.’ * Living such a life as this, in addition to the riskhe runs of having his lonely hut plundered of his few traps by some marauding white or blackfellow, is it a wonder that such a man should expect 20/- (a week) for his services? 2Nonetheless, there is today a perception that shepherding was something of a pastoral idyll. If youwere content with a solitary life, generally free of pressure and physical exertion, shepherdingwas not such a bad option. The reality was probably rather different, and for white shepherdsthe history of relations with local Aboriginal people was front of mind. For this and other reasonsmany pastoralists far preferred to employ native shepherds. Maureen and Bill Nosworthy paint aparticularly stark picture of the shepherd’s life on the remote west coast of Eyre Peninsula. Asidefrom the utter loneliness, relations with local Aboriginals were quite fraught, an extract from theLake Hamilton journal notes: ‘Shepherd to Adelaide with insane wife.’ 3* Alludes to the notation often used in the employer’s contract with the shepherd.10 THOSE DRY-STONE WALLS