An Interview with Neville Higgins: Part 13 - Vincent HRD Owners Club

An Interview with Neville Higgins: Part 13 - Vincent HRD Owners Club

An Interview with Neville Higgins: Part 13 - Vincent HRD Owners Club

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

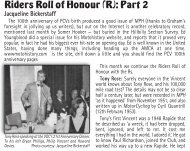

YOU the <strong>Club</strong> Members. So, Gentlemen, a big vote of thanks to the Technical Committee andthe Executive Committee before we go any further.B: I’ll go along <strong>with</strong> that too <strong>Neville</strong>. What’s next?N: While Frank was busy in Holland I kept going in Sweden, updating my crankcase drawingsand converting them to VOC standards, then drawing the G2 gearbox cover plate and the G50RH pivot plate. Then I got into the gearbox shafts, which are critical components; here I tookadvantage of Tony Maughan’s extensive experience on the clutch shaft, where he had up to30 per cent scrap rates on case hardened components due to distortion of the long thin shaft— so he had gone over to nitride hardening which is more expensive, but is done at much lowertemperatures which minimise distortion. So I did the same.After that I attacked the gears themselves, but was soon over my head in difficulties. Standardgears working at standard centre distances are fairly straightforward to design. The 10/12 DP(diametral pitch) gears in the <strong>Vincent</strong> box, working at 2.4” shaft centres, should all have atotal of 48 teeth on each pair of meshing wheels, but in fact, to adjust the internal gear ratios,three pairs have 46 or 47 teeth, and the one remaining pair which does in fact have 48 teethis oversize on one gear and undersize on the other due to some earlier non-standard set upwhich has later been altered! <strong>Vincent</strong> gears have, for instance 18 teeth cut on a 19 tooth PCD(pitch circle diameter) 20 cut on 21, or 23 cut on 24. There are a lot of different ways of doingthis sort of ‘gear cheating’ and it is no easy job to determine what the designer has actuallydone by looking at used parts. Most automotive firms seem to have their very own gearboxspecialist, who has done the job for more than fifty years, and does it his own special way —which works fine, but nobody else knows how he does it!After about 15 unsuccessful tries and 40 pages of calculations I went up to the Volvo gearboxsection thinking that they would have a computer program I could use to design our gears. <strong>An</strong>hour later, after being passed around six of their ‘experts’ I came away no wiser, and <strong>with</strong> theamazing realisation that absolutely no-one on the gearbox section had ever designed a gearwheel himself!I kept on fighting the gears until about mid-1996 when Don Alexander suggested we shouldcontact a certain Roger Moss, who ran his own machine shop and made gears among otherthings. We had a very useful discussion on a number of parts, but he could not help much onthe gears — confirming my thoughts above — that gear specialists are a breed unto themselves,and operate in ways unknown to others. However, he gave me the name of <strong>An</strong>drew Jardinewho manages Sovereign Gears Ltd, a firm which specialises in producing replica gears, manyof them for ancient automobiles. I contacted <strong>An</strong>drew and went to visit complete <strong>with</strong> a pileof drawings, getting a lot of useful feedbackfrom him, and leaving my drawings <strong>with</strong> himfor checking.<strong>An</strong>drew was a real enthusiast, and I think hewas fascinated by the thought of producing<strong>Vincent</strong> gears to proper drawings — ratherthan just being given a broken crownwheeland pinion (or something) from a 1921Whotsit Special <strong>with</strong> the request “Can youmake me a new one of these, please?” Forthe next two years there were drawingsand faxes, questions and answers, half pagecalculation formulae, and telephone callsThe Prof on his Black Prince <strong>with</strong> home made pannier boxes,which were loaned to Phil Primmer to make productionmoulds from. Photo courtesy: Allt Om MC Magazineflying back and fore between us, until inJune 1998 we were finally in agreement onall gear sizes and had cutting instructions

which would produce gears to match all the samples we had measured. By then I had fourcomplete exercise books full of calculations, and a one inch thick file of correspondence <strong>with</strong>Sovereign Gears, plus another inch <strong>with</strong> the Technical Committee. As a mark of our appreciationfor all his help, I prevailed on the Executive Committee to allow me to invite <strong>An</strong>drew Jardineand his wife to our <strong>An</strong>nual Dinner in 1998, so that he could meet some of the other <strong>Club</strong>Officials and Members.I retired at the end of 1991, but went into the office a number of times to help out for a fewhours on some of the projects which I had not had time to complete, and in return got the OKto continue <strong>with</strong> my drawing work for the <strong>Club</strong> using a spare CADAM terminal. Thus I kept intouch <strong>with</strong> all my old cronies, and made a lot of drawings as well.B: A sort of mutual benefit program you might call it.N: Yes, and motorcycle racing benefitted in other ways as well.B: What was that then?N: Well, in addition to being deeply involved in building and racing <strong>Vincent</strong>s I was dragged intorace organisation through one of our local clubs — SMK Gothenburg Section, whose Chairman,Karl Oskarsson, was a tireless worker and organiser for all sorts of race meetings. They werestrong on trials, since many members were famous trials riders in their younger days, butOskar, as he was always called, set up the Diamond Jubilee TT road race meeting in 1986 whichwas a great success. I missed this one, but joined SMK in 1987 to ride in the second one, whichwas the first meeting at Stora Holm. I was immediately roped in as an advisor on setting upthe circuit and flag marshals posts, and my wide network of contacts at Volvo was used torecruit many flag marshals to help out on race day. I had a pretty busy time trying to organiseall the marshals on race day, as well as get myself and the bike ready to race!Oskar then got me involved in judging for trials, and I ended up <strong>with</strong> a functionaire’s licenceand a lot of work on that score! It culminated in Oskar persuading SVEMO (the Swedish ACU)that we could run a round of the World Trial Series in 1991. This was a huge job which entailedenlisting and training a team of five or six people for each of some 20 sections. Not only didwe have to run the trial — but we had to cut a world class trial course out of virgin forestas well. Luckily we had another Englishman in the <strong>Club</strong>, Keith Bartlett, who was an absolutedab hand at making trials sections, and a gang of us was out <strong>with</strong> him many evenings andweekends, cutting and clearing and marking up each of the sections. Nowadays it makes mefeel faint to think of all the work we got through in our spare time!Oskar and a couple of others went down to a couple of other European rounds and cameback <strong>with</strong> the news that the judging was varied over the different sections, and that oftenthe top competitors were judged too leniently because the marshals were afraid of offendingthem! Many other Swedish clubs sneered and said SMK could never run a World Cup trial —but everything ran as if on rails, and the competitor’s verdict was that the judging was verystiff — but absolutely fair and even on all sections. We had big congratulations from SVEMOafterwards, and in 1992 when Sweden was awarded a round of the European Trial cup, theycame back to us and asked us to run it for them — so we had to do the whole thing over again— including building a new course in a different area!Our Man Oskar also dragged us into enduro race organisation. Around 1990 we ran theNovember Kåsan, which is the oldest enduro race in Sweden, and involves 24 hours of crosscountry racing in winter conditions. Again there are huge logistical problems in setting acompetitive course of 150 to 200kms <strong>with</strong> about 20 timed sections in the forest, and transportsections on the roughest available tracks, and in getting all the necessary permissions fromlandowners, police, councils etc. Each section has to have a trained team of timing marshalsat both the start and the finish, and competitors go off at one minute intervals and are timedto the second over each section. The start is at <strong>13</strong>00hrs on Saturday, and each rider goesaround the course three times, one of them during the night, and they get about three hours