Mythologies - The Scottish Gallery

Mythologies - The Scottish Gallery

Mythologies - The Scottish Gallery

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Mythologies</strong>

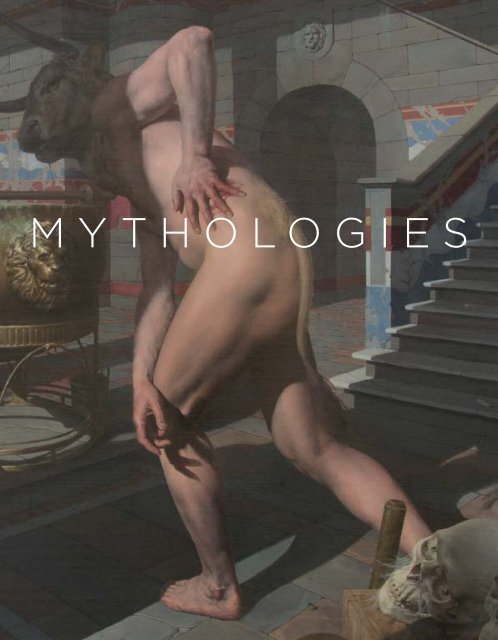

paul reid<strong>Mythologies</strong>2 AUGUST – 4 SEPTEMBER 2013foreword 3prologue 4introduction 6Hercules and the Cup of Helios 9<strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur 17<strong>The</strong> Island of Circe 31Pan 63Medusa 69list of work 72biography 7316 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZTel 0131 558 1200 Email mail@scottish-gallery.co.ukwww.scottish-gallery.co.ukCover: <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, oil on canvas, 161 x 201 cmsLeft: Hercules and the Cup of Helios I, oil on canvas, 100.5 x 81 cms

2 | PAUL REIDI have followed Paul’s work with great interest from the early daysfollowing his graduation through to a solo exhibition of his paintings heldat <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> in 2002. Since then, he has continued to expand hiswork through classical traditions of painting, presenting the viewer withnew and personal interpretations of Greek mythology. His art pays respectto the great masters and traditions of the past; the understanding of theirmethods and techniques has been crucial in allowing him to develop atruly unique and contemporary vision.HRH Prince of WalesPaul Reid, 108 Fine Art Ltd, 20071 Cyclops, black ink on board, 73 x 53 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 3foreword<strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> always mounts a major, one-person exhibition for <strong>The</strong> EdinburghFestival and this year is delighted to present <strong>Mythologies</strong> by Paul Reid. Reid has movedon from the neo-classicism which characterised his first exhibitions to describe a dystopiawhich combines contemporary references and classical illusions. <strong>The</strong>re is no room forempathy in a world of hubris and nemesis but now the cruelty and violence perpetratedon Odysseus on the Island of Circe might as well be wrought by an implacable Serbianwarlord as an angry Olympian. Of course Reid as a consummate modernist does not wishto lead us by the nose; his images are as enigmatic as the most arcane of Damien Hirst’smise-en-scenes, quite available for individual interpretation. <strong>The</strong> figures of Odysseusand <strong>The</strong>seus might be Special Forces, partisans or everyman heroes from the world ofgaming. <strong>The</strong> bestiality of the Minotaur and Odysseus’ soldiers could be symbolic or theresult of a ghastly genetic experiment appropriated by a sinister military establishment.What is without question is the commitment of the artist to his inspiration, methodsand technique. His determination to work with live models, create and then scale upthe many props and furnishings in his major opus <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, makeendless studies, some squared up; to perfect the perspectives and light distribution ofthe labyrinth is a remarkable undertaking. His easy facility is sometimes his ally but likeevery element in his painting it has to be subordinate to his uncompromising vision.His restricted palette, perfectly modulated tones, accurate anatomies, control of detail,balance of masses – every craft of the guild of painters – is subverted to present astrange, odd and compelling new reality.Guy PeploeTHE SCOTTISH GALLERY

4 | PAUL REIDPROLOGUEI first became aware of Paul Reid’s paintings when I was a lecturer at Duncan ofJordanstone College of Art in the mid nineties. As part of the first year course schedulestudents were asked to make a self-portrait. I remember being very taken with thesmall head and shoulders self-portrait that Paul produced. <strong>The</strong> painting had somethingof the warmth of colouring of Van Dyck and the cool gaze of Velázquez. It showed aprecocious talent with serious intent that said to me that this was someone to watch.In the subsequent four years Paul devoured Max Doerner’s <strong>The</strong> Materials of the Artist andtheir Use in Painting. He learned to grind pigments and make a paint that had the desiredconsistency for his works. At the same time Paul also immersed himself in studyingRubens, Van Dyck, Titian and Velázquez, the artists whose techniques he sought toemulate. Paul was painting wonderfully assured realist still lifes and thoroughly engagingportraits of family and friends. <strong>The</strong> still life works and portraits were powerfully realisticwith an ease of handling that showed his deep understanding of the language of theMasters he was studying. It was while studying Rubens that Paul became interested inmythological based works. Through studying the titles and names referred to by Rubenshe became aware that they referred to Greek myths. In a sense Paul was led to classicalmythology by the process of painting itself. Paul began studying Ovid’s Metamorphoseswhich opened up a vast subject where he could expand, channel and challenge hisformidable powers of realistic painting, over the next 15 years.Paul’s first classically inspired work was a large painting <strong>The</strong> Death of Actaeonpainted in his fourth year. This was a very significant transitional point for Paul: it waswhere his portraiture, life room studies and still life knowledge were all pulled togetherinto one large successful composition. It was intriguing at the time to leave his studioand see the faces of the characters of his paintings wandering the art school corridors.Paul’s subsequent ongoing body of mythologically inspired paintings have worked sowell because of his powers to instill a potent sense of reality. It is not an arcane orunreachable reality but something timeless and tangible.Characteristic of his subsequent works is his ability to impart a vast amount ofinformation without confusing or distracting the viewer. His paintings overflow withvisual material: images of fruit and vegetables, costume, portraiture, human form inaction, metamorphosis, landscape, architectural details and still life. All of these thingsplaying a part in his highly orchestrated compositions.Derrick Guild, RSAPaul Reid in his studio, June 2013

MYTHOLOGIES | 5

6 | PAUL REIDintroductionPaul Reid, growing up in the Perthshire in the 1980s lovedsuperheroes and comic books. He not only loved to watchand read them, he loved to draw them.His passion for drawing led him to embark on aportfolio course in Dundee. He then applied to and wasaccepted by Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art andDesign.It was the early 1990s and the contemporary art worldwas in the grip of post-modernism. If ever there had beenan era not to specialise in painting as a young artist, thiswas it.“At art college, they tried to make me do sculpture,video art, and installation,” recalls Reid. “But it justwasn’t me. I wanted to draw and paint, which was veryunfashionable at that time.”Thankfully, Reid persevered and although some of histutors – notably the artist Derrick Guild – were supportive;he ploughed his own furrow. He painted still lifes andportraits and read voraciously about painting techniques,while studying the work of the old masters.As his fellow students looked to the likes of emergingartists such as Damien Hirst or the Chapman Brothers asrole models, Reid’s bible became Max Doerner’s guide totraditional painting methods, <strong>The</strong> Materials of the Artistand <strong>The</strong>ir Use in Painting.Looking at the work of great Renaissance and Baroquepainters such as Rubens and Titian, Velázquez, he foundhimself beguiled by the Greek myths which they portrayso vividly.He says: “When I was really young, I had Ladybirdbooks which told the story of legends such as <strong>The</strong>seusand the Minotaur and Perseus and the Gorgons. <strong>The</strong>stories were very vivid in my memory.” As a young artstudent, Reid rediscovered the myths through Ovid’sMetamorphoses and ideas started to flow. He had foundhis concept, and it was the stuff of life.<strong>The</strong>se stories of men turning into animals, facing upto adversity, getting lost in unfamiliar places, or ignoringwarnings from those wiser than ourselves... they were all,he realised, the base point for storytelling the world over.For his degree show in 1998, Reid produced a largepainting called <strong>The</strong> Death of Actaeon. This myth tellsthe story of how the huntsman Actaeon disturbed thegoddess Diana while she bathed. Furious, she turned himinto a stag and he was then devoured by his own hounds.Unlike Titian’s fluid, erotically-charged version of thesame myth which seeks to tell the whole myth in onetableau, Reid presented a moment of almost incidentaldrama as Actaeon’s friends find his clothes, a phalanx ofyoung men like a bas-relief across the picture plane. <strong>The</strong>composition was masterful and the technical virtuosityhe displayed grabbed viewers to his degree show by thescruff of the neck.Reid received a first-class honours degree and hiswork garnered much attention, with Art Review evenfeaturing him on their front cover of their Novemberissue under the headline: Painting? Still worth a look! Inthe intervening fifteen years, Paul Reid’s paintings havechanged and developed. But he has steadfastly stuck tohis guns in his desire to be and to remain a painter andin large part resisted also taking on commissions, whichcould have led him in a direction not of his own choosing.For this solo exhibition at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> as partof the Edinburgh Art Festival 2013, Reid is still miningthe rich seam of narratives he finds in the world of Greekmythology.He has never thought of himself as a neo-classicist,being interested in realism over idealism, but this bodyof work seems to take him further away from Poussin orJaques-Louis David. Reid asserts as never before that heis painter of his time. Like many film makers, such as PeterJackson, his childhood hero was Ray Harryhausen, whomade Jason and the Argonauts (1963) and Clash of theTitans (1981). Reid was also part of the first generation toplay video games on consoles at home. He’s still a fan ofgaming and finds in the worlds enjoyed by gamers a verysimilar aesthetic to his own. Reid’s paintings referenceboth worlds and as ‘director and producer’ of his ownproductions, he plans his epic paintings with cinematicprecision.<strong>The</strong> scenes he paints are planned initially in miniature.Models are made, disposed, and photographed to forma storyboard. Had you been on Portobello beach one

MYTHOLOGIES | 7day last year, you might have seen a man lying on thebeach taking photographs of tiny golden cup emergingfrom the sand. <strong>The</strong> resulting paintings, Hercules and theCup of Helios I and II bear all the hallmarks of classic Reid.A <strong>Scottish</strong> seascape in the background, an exquisitelypainted hero emerging from a gold cup, the perspectivejust utterly right whichever way you look at it.But only after Reid is completely happy with thestaging, will he start the process of making his painting.For <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, which shows a hesitantMinotaur straining to look behind a pillar to see if hisnemesis, <strong>The</strong>seus, is there waiting to pounce, Reid foragedin the Games Workshop for props. Friends will be ropedin to pose but when he is setting up a scene in miniature,to make sure perspective is correct and shadows fallaccurately, he will use toy figures.<strong>The</strong> level of detail in a Paul Reid painting is not slavish;he has no pretentions to super realism; the mark of thebrush is not disguised. But the level of realism he achievesis astonishing. He often underpaints in traditional blackand white grisaille before starting to paint the figures inoil and for his architectural settings he will deploy squaredup drawings. <strong>The</strong> landscape, he says, is always paintedaround the figure. Renaissance masters were happy toinclude ‘contemporary’ references into their retelling ofGreek mythology and Reid has no use for ‘continuity’advice in the complex world he creates. Once his ideas aregathered into place the drawing and painting is practicaland the pursuit is one of dogged realism. Reid foundthe perfect Circe backdrop when he was out on a walkin the Pentland Hills. Grafting a pig’s head onto a man’sbody is not a hardship for this consummate draughtsman.“Pigs are pretty much like humans,” he smiles. Odysseusis also wearing a mixture of clothing and accessoriesfrom various eras. His rifle and boots could have walkedstraight out of a World War Two action film.quizzically from a beautifully rendered goat’s head. Hisman’s torso is clad in a contemporary T-shirt. According toReid, the challenge when painting Pan is not to make himlook too Satanic. When tackling the similarly demonisedMedusa, often portrayed as the monster she becameonce the goddess Athena robbed her of her beautyin perpetuity, he has tackled the painting like a societyportrait. “She was one of the most beautiful woman in theworld,” he says. “I wanted to convey this in my paintingof her.” <strong>The</strong> snake head began with the figure of a Fury,seated at the gates of Hades in his painting <strong>The</strong> Abductionof Persephone (2008) but the modeler’s backstory to thispainting is that Reid, the father of two young children,found some toy snakes and knew they would be a perfectfor his Medusa.As an avid and eclectic reader, he cites influence feedinginto his work from texts as varied as; Milton’s Comus,Kafka’s Metamorphoses, H.P. Lovecraft’s Pickman’s Model,Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5 and H.G. Wells’ <strong>The</strong>Island of Dr Moreau.At the heart of Paul Reid’s art lies a deep empathywith his characters and a pin-sharp sense of place. <strong>The</strong>ycan be read at face value as enigmatic (weird, Paul mightprefer) or as complex, contemporary commentarieson the human condition. <strong>The</strong> way I view them, they arenot neoclassical paintings, they are part of the story ofmankind.Jan PatienceVisual arts writerJuly 2013Reid has real empathy with the characters he paints. Histender portrait, Pan, god of wild places (usually depictedas a man with the horns, legs and tail of a goat, a bushybeard, squat nose and pointed ears), reveals him at rest;his arms and legs crossed, his eyes staring at the viewer

herculesand the cupof helios

10 | PAUL REID

MYTHOLOGIES | 11Hercules’ anger grew as he waited on the sea shore,trying to find a way to reach the island of Eretheia,where Geryon kept his cattle. He railed at the sun godHelios whose unrelenting rays tortured him. He fired hisarrows at the god, who was amused by his passion, badehim quiet and lent him his golden cup to bear him acrossthe waters. For Reid his crossing has not been easy and hearrives half drowned, to sleep on the deserted beach, hismaul in his hand in the shadow of the giant cup. Nor hasReid sought to locate the hero in the Aegean but ratherit is a <strong>Scottish</strong> shore. <strong>The</strong> painting relates to his Orionof 2004 when again he set a heroic figure in a <strong>Scottish</strong>landscape, playing with ideas of scale. In this and Herculesand the Cup of Helios II the impossibility of the giantcup lends a surrealism to the moment, as ever reinforcedby the hyper-reality of the painting: the foreshorteningof Hercules’ foot refracted through water in I; the sunlighton the rocks and grass on the island, in II and the wetnessof the leather belt and fabric tunics in both paintings.2 Hercules and the Cup of Helios I, oil on canvas, 100.5 x 81 cms

12 | PAUL REID

MYTHOLOGIES | 133 Hercules and the Cup of Helios II,oil on canvas, 76 x 95.5 cms

14 | PAUL REID4 Hercules, Study II, oil on canvas paper, 31 x 50 cms

5 Hercules, Study I, oil on canvas paper, 30 x 40.5 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 15

tHESEUS ANDTHE MINOTAUR

18 | PAUL REID<strong>The</strong> game is on. <strong>The</strong> characters fully engaged in a deadlypursuit of hide and seek. <strong>The</strong> hero, fear in his eyes, hideswith his back to the great stone column, but ready tospring into action. In one hand is his axe, in the otherhe holds an amulet. A golden brazier has fallen to thefloor and perhaps alerted the Minotaur to the presenceof an intruder and the beast has his smell. <strong>The</strong> action isplaced in the labyrinth of King Minos’ palace at Knossos,a cool, complex, stygian interior. Beyond the presenceof the protagonists it is all entirely from the imaginationof the artist and the fantasy is given a hyper-reality bythe realism of the treatment and extraordinarily accurateperspective. <strong>The</strong> artist has appropriated some Minoandetail, like the frieze, and other details have necessitatedthe construction of tiny models such as the brazier andstaircase, to fully understand their forms and shadows.Elsewhere in the imagined narrative a great, brass pot,decorated with a lion’s head, may have been used torender heads to skulls, whose presence in the bottomright of the painting is a grisly memento mori. This is whythe Athenian hero has come: to end the blood sacrifice ofthe city’s gilded youth to the appetite of the beast.6 <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, oil on canvas, 161 x 201 cms

22 | PAUL REIDFor Reid drawing is vital to his process. Elaboratepreparatory drawings, some squared up and transferredto canvas (Fig. 1), are made; individual poses are exploredand even drapery studies undertaken. <strong>The</strong>re are no opticaldevises deployed; there is no projection or manipulationof imagery within a computer programme. His technicalrepertoire is faithful to Renaissance studio practice, exceptthe painter has no studio assistants and carries out thework himself in the east of Edinburgh. This discrepancybetween the all embracing aesthetic of his imaginedworld and the mundane surroundings of his workplace isstark. <strong>The</strong> explanation is that Reid is not isolated becausehe has embraced digital media and devices which givehim access to imagery, ideas, sounds and communitieswhich feed his imagination. Graphic novels, metal music,literature of weird, the work of Odd Nerdrum, videogames and Spanish Masters can be accessed at the touchof a button.Fig. 1 – under drawing for <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II

Actaeon, charcoal on paper, 75 x 56 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 23

24 | PAUL REIDMuch of the narrative content in my own work has thus farbeen directly inspired by Greco-Roman mythology. This mayincite accusations of an empathy towards nineteenth-centuryacademicism. Nothing could be further from the truth, however,and historical dogma such as that espoused by the likes ofDavid and his followers is as abhorrent to me as it is to the mostardent modernists. To my mind there is no right or wrong wayto interpret classical myth, and it is this openness to new artisticinterpretation which has no doubt contributed to its continuedrelevance throughout the history of art.Paul ReidArt Review, November 1998details from <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, oil on canvas, 161 x 201 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 25

26 | PAUL REID

MYTHOLOGIES | 277 <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur I,oil on canvas, 107 x 132 cms

28 | PAUL REID<strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur I, oil on canvas, 107 x 132 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 29<strong>The</strong> beast sleeps as the hero hauls himself from the well,his assassin’s knife clenched between his teeth. <strong>The</strong> lightsource is the sun and comes directly from the left andthe viewpoint is from above, the viewer floating abovethe action, close enough to smell the blood, sweat andfear. <strong>The</strong> composition is in perfect balance and tension:the claustrophobia of the moment before violence. It iscinematic: the still from a movie that might have beenselected for the poster; everything is said in one shot.Reid’s technique is as brilliant as ever but this paintinghas come quickly for him. No revisions or trial preparationsin other media were undertaken. It has come completeand awful; glimpsed and made permanent in every detail.

the islandof circe

32 | PAUL REID8 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 130.5 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 33Looking at Reid’s painting Odysseus on the Island of Circe,there is a sense that this scene is being recorded, whetherthe scene is a contemporary re-enactment or some kindof parallel universe under our noses, it still convinces usthrough the power of its realism. <strong>The</strong> care and attentionReid lavishes on his elements, from the humble turnipto the smoke billowing beyond Odysseus to the highlycharged detail of the spectacles on the shirt, that seemto hint at much more contemporary incarceration, makethis scene, wherever it is taking place believable. <strong>The</strong>reare many associations reverberating through Odysseus onthe Island of Circe, I am reminded of Velázquez’s Forge ofVulcan: the sense of air and light, the wonderful surprisethat Velázquez imparts in the young blacksmith’s face,and how the tools on the floor of the forge gently createinterest and a guiding structure. Reid’s tour de force ofstill life painting in the vegetables echo Velázquez toolsperfectly. <strong>The</strong> vegetables also lead me to William YorkMacgregor’s great realist work <strong>The</strong> Vegetable Stall, whichin turn takes me to the naturalism of Bastien Lepage andthe French Realist School. <strong>The</strong> painting also brings tomind the scene in Lindsay Anderson’s 1973 film O LuckyMan!, with the scene where the main character, MickTravis discovers a man with a pig’s body in a hospital bed.Anderson began his film career making documentariesand it is his clear-eyed realistic approach to filming thatcreates a stark and believable truth. Film is somethingthat I feel resonating in Reid’s work and it does notsurprise me that he has a strong following from thegaming industry.Derrick Guild, RSA

34 | PAUL REID

MYTHOLOGIES | 35Odysseus on the Island of Circe,oil on canvas, 106.5 x 130.5 cms

36 | PAUL REID<strong>The</strong>re is a wealth of sources for an artist looking at Odysseus and Circe. She is anenchantress who invites the hero’s scouts to a feast and poisons their drink totransform them into pigs. He is warned and takes a herbal remedy as protection fromthe same draft so that instead Circe falls in love with him and releases his men fromthe enchantment in return for his sexual favour. Reid made a spectacular, colourfulversion of the same moment: the hero discovering his men transformed into beasts(Fig. 2) but the treatment is pure neo-classicism: Poussin and David are clear inspirations.In the new painting the aesthetic is very different: stark, modern, dystopic and disturbing.<strong>The</strong>re is huge violence in the Greek myths; Odysseus’ previous adventure is amongstthe cannibalistic Laestrygonians where all but his own ship are destroyed by rocks andthe men skewered and eaten by giants. On Circe’s island the action is more subtle andmany Victorian painters chose to depict the sorceress and her lions and wolves as a rulerand temptress in the mould of She. Instead Reid returns to the discovery by Odysseus ofhis men, made into pigs. Pigs have long been associated with greed and lust, particularlyin Flemish iconography but the return to bestiality and cruelty of people shorn of moralrestraint is also a literary theme well understood from Golding’s Lord of the Flies andOrwell’s 1984.Fig.2 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, 2007, oil on canvas, 101 x 147 cms, Private Collection

9 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study III, pen and charcoal on board, 42 x 37.5 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 37

38 | PAUL REIDFor Reid, the classical tradition is of such profoundimportance that, although his work might appearretrogressive, he instead sees a path full of newpossibilities and new challenges, unencumbered bymodern theoretical baggage. He would refute accusationsof archaism, and instead challenge those who consider hisapproach anachronistic, as being incapable of projectingtheir imaginations beyond the present.Philip LongPaul Reid, New Works, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, 2002Odysseus is in deep contemplation of how he mustrescue his soldiers and resolve this latest challenge tohis Odyssey. His worry and doubt is palpable. Reid hasmoved the action to an interior and gives hints that it is asmuch prison as shelter. <strong>The</strong> pig-soldier has his head in thetrough, incapable of acknowledging either his commanderor his debased existence. Like Pan he seems captive, butunlike Pan he is oblivious, his humanity further denied tohim by his transformation and incarceration. Both thesefigures are a compelling reminder of other captives withbags over their heads, their individuality and by extensiontheir humanity curtailed.

10 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, acrylic on canvas paper, 46 x 38 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 39

40 | PAUL REID<strong>The</strong> figure of Odysseus has also been reappraised from theartist’s previous depictions. Now he is a grizzled warriorin a ramshackle assembly of clothes and weaponry;canteen, rifle and boots might have been recycled fromthe aftermath of a previous War and his tunic and coatare practical for marching and fighting. Only his swordseems fit for a hero. He is favoured by the Gods but isalso a mercenary whose principal loyalty is to his ownband of warrior companions whose fate is once again inthe balance.11 Portrait of Odysseus, oil on canvas, 91 x 51 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 41

42 | PAUL REIDIn making the fully worked versions of the hero Reiddemonstrates his extraordinary commitment to his finalpainting. But these works are much more. <strong>The</strong> first twoare very close (and seem almost to invite the child’s gameof spot the difference). <strong>The</strong> chief difference is the additionof the landscape and we are invited to see Odysseus as afilm actor, once, posed in front of the green screen thenplaced cinematically in a computer generated world.In this way the artist comments on the idea of mythmakingand image-making; he takes no short-cuts butreferences a world of endless visual possibility.<strong>The</strong> next two studies were made in competition fordeployment in the final painting, Study I being finallyused. But once again the artist plays with the idea of film.<strong>The</strong>y could be near consecutive frames, the first depictingthe shock of discovery the next the hero laying down hisrifle, seeking to help but the terror of the scene makinghim move his right hand instinctively onto the hilt ofhis sword.12 Study for Odysseus, acrylic on board, 51 x 35.5 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 43

44 | PAUL REID13 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study I, acrylic on board, 51 x 35.5 cms

14 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study II, acrylic on board, 51 x 33 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 45

46 | PAUL REIDNothing goes to waste in the studio and the pose ofActaeon has been recycled for the Minotaur in <strong>The</strong>seusand the Minotaur II. Actaeon, in the myth retold by Ovid,is transformed into a stag and then hunted and killedby his own hounds after he has surprised and enragedArtemis, the Goddess of the Hunt. Reid had used themyth in a painting of 1998 which describes the momentthe hunter’s friends discover his bloodied tunic. In thisnew study he flees, wounded, through the woods andis a clear reference to the violence and bestiality whichcharacterises Circe’s island.

15 Actaeon, charcoal on paper, 75 x 56 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 47

48 | PAUL REID

MYTHOLOGIES | 4916 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Island of Circe,oil on textured canvas, 71 x 91 cms

50 | PAUL REID17 After the Hunt, charcoal on board, 42 x 50.5 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 51Circe’s island is a savage place in Reid’s imagining. <strong>The</strong>reis no hint of civilisation and already in the forest his menare butchering deer for meat and hides. <strong>The</strong> man wieldingthe flaying knife in After the Hunt has himself the head ofa stag and the implication is clear.

52 | PAUL REID<strong>The</strong> trees take us back to studies made in Argyll within thelast five years. Ancient, gnarled, clad in moss, festoonedwith ivy, they are the sinister guardians of the forest’ssecrets wherein pantheism will see conducted its violentrites and sacrifices. <strong>The</strong> very absence of action in <strong>The</strong>Great Tree, Study, the perfect stillness of the leafy forestfloor and dappled light filtering through the canopy actslike the pause before violence in <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaurto create a dramatic tension.

18 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Study, oil on canvas paper, 43 x 60.5 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 53

54 | PAUL REID

19 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Study II, pen on board, 42 x 59.5 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 55

56 | PAUL REID20 Tree Study, Argyll, pen and charcoal on board, 39.5 x 50 cms

21 Tree Study, Argyll II, pen and charcoal on board, 43 x 35 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 57

58 | PAUL REIDReid’s paintings and drawings for Circe’s island are nota narrative sequence; he does not seek to tell the story.In reality the setting is a pretext and he has nocompunction about visual extrapolation of his material.<strong>The</strong> wistful lion man sits forlorn by his damaged boat –his thwarted means of escape, looking out to sea, to theliberation it represents, trapped, stripped of his humanityand the freedom it implies, now a heroic figure in isolationbut soon to be drawn back into the sorceress’s violentsurvival game.

60 | PAUL REID

23 Stranded, Island of Circe, Study, pencil and charcoal on board, 45.5 x 61 cmsMYTHOLOGIES | 61

PAN

64 | PAUL REIDPan is one of the most complex of mythological figures.He has been associated with music, lust, modernpaganism, and the occult. He was one of only two GreekGods who died. Reid prefers to depict him with a goat’shead rather than the more conventional lower half, so thathe fits in alongside the figures of Actaeon, <strong>The</strong> Minotaur,Cyclops and Odysseus’ soldiers, condemned and isolatedin their beastly transformation. Pan is more like a creaturecreated by Dr Moreau, depicted by Burt Lancaster,conducting secret experiments on a remote island in thebest Hollywood tradition of the mad scientist, in the filmof 1977, than the playful companion of Dionysus.24 Pan, oil on canvas, 61 x 46 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 65

66 | PAUL REID25 Pan, conté on paper, 62 x 66 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 67In the drawing, which came first and relates to anotherpainted composition, Pan is clad in crude linen draperyand sandals. In the painting he is in t-shirt and a loose scarfis around his neck. He sits in subjugation: a bracelet couldbe a manacle; he is like a youth of the Intifada, surroundedby the rocks which might have been his crude armoury.In both painting and drawing the setting is architectural,one outdoor and the other inside, prison-like andoppressive. In one his head is at a defiant angle and helooks out directly; in the other Pan’s eyes are downcast;and in both his narrative is uncertain.

MEDUSA

70 | PAUL REIDReid’s honesty and his insistence on keeping it real havemade him suspicious of the moral claims sometimesmade for art. A review of the recent Velázquez show inLondon which compared the painter’s surface effects withhis ‘inner truth’ made him bristle. To Reid, the businessof painting is about appearances; what an audience seesbeyond them is their own affair. If there’s an inner truthto his work, he’s not letting on. <strong>The</strong> myths of antiquityhave retained their power over us because their meaningsare open-ended; Reid’s pictures operate on the sameprinciple. It augurs well for their longevity.Laura GascoignePaul Reid, 108 Fine Art Ltd, 2007<strong>The</strong> myth of the Medusa is one of the most familiar andcompelling from the Greek mythology. Reid is consideringa painting and this highly finished, painted study is in onesense preparatory and looks forward to the artist’s nextproject. He sees her as at once mundane and fantastic.Her calm presence belies the terrible turmoil of her snakeheaddress while her implacable stare suggests the stonyfuture which awaits any who return her gaze.26 Medusa, oil on canvas paper, 62.5 x 35.5 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 71

72 | PAUL REIDList of workAll work is for sale on receipt of catalogue1 Cyclops, black ink on board, 73 x 53 cms2 Hercules and the Cup of Helios I, oil on canvas, 100.5 x 81 cms3 Hercules and the Cup of Helios II, oil on canvas, 76 x 95.5 cms4 Hercules, Study II, oil on canvas paper, 31 x 50 cms5 Hercules, Study I, oil on canvas paper, 30 x 40.5 cms6 <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur II, oil on canvas, 161 x 201 cms7 <strong>The</strong>seus and the Minotaur I, oil on canvas, 107 x 132 cms8 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, oil on canvas, 106.5 x 130.5 cms9 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study III, pen and charcoal on board, 42 x 37.5 cms10 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, acrylic on canvas paper, 46 x 38 cms11 Portrait of Odysseus, oil on canvas, 91 x 51 cms12 Study for Odysseus, acrylic on board, 51 x 35.5 cms13 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study I, acrylic on board, 51 x 35.5 cms14 Odysseus on the Island of Circe, Study II, acrylic on board, 51 x 33 cms15 Actaeon, charcoal on paper, 75 x 56 cms16 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Island of Circe, oil on textured canvas, 71 x 91 cms17 After the Hunt, charcoal on board, 42 x 50.5 cms18 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Study, oil on canvas paper, 43 x 60.5 cms19 <strong>The</strong> Great Tree, Study II, pen on board, 42 x 59.5 cms20 Tree Study, Argyll, pen and charcoal on board, 39.5 x 50 cms21 Tree Study, Argyll II, pen and charcoal on board, 43 x 35 cms22 Stranded, Island of Circe, acrylic on board, 44 x 61 cms23 Stranded, Island of Circe, Study, pencil and charcoal on board, 45.5 x 61 cms24 Pan, oil on canvas, 61 x 46 cms25 Pan, conté on paper, 62 x 66 cms26 Medusa, oil on canvas paper, 62.5 x 35.5 cmsNon illustrated27 Portrait Study for Odysseus, pencil & charcoal on board, 48 x 33 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 73PAUL REID1975 Born Scone, Perth1994-98 Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art, DundeeFirst Class Honours in Drawing and PaintingAwarded the Carnegie Trust VacationScholarship and a John Kinross Scholarship.Studied in Madrid and Florence2004 Accompanied His Royal Highness <strong>The</strong> Princeof Wales on a visit to Italy, Turkey and Jordan,completing a series of paintings and drawingsbased on the landscape and people of theareas visited2009 Accompanied HRH on a visit to CanadaSolo Exhibitions2013 <strong>Mythologies</strong>, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Edinburgh2009 Paul Reid, Isis <strong>Gallery</strong>, London2008 Paul Reid, Perth City Art <strong>Gallery</strong>(touring exhibition)Paul Reid, Dundee University Art <strong>Gallery</strong>(touring exhibition)2007 Paul Reid, Hull University Art <strong>Gallery</strong>(touring exhibition)21st Century Painting, 108 Fine Art, Harrogate2004 Orion, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Edinburgh2003 Apollo and Pan, Art London with<strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>2002 New Works, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, Edinburgh1999 <strong>The</strong> Rendezvous <strong>Gallery</strong>, Aberdeen<strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong>, EdinburghCollectionsHis Royal Highness <strong>The</strong> Prince of WalesDuke and Duchess of Roxburghe<strong>The</strong> Royal <strong>Scottish</strong> AcademyPerth Museum and Art <strong>Gallery</strong>, Perth and Kinross CouncilUniversity of Dundee Museum ServicesDuncan of Jordanstone College of Art Collection<strong>The</strong> Fleming CollectionSelected bibliography<strong>The</strong> Dictionary of <strong>Scottish</strong> Painters, 1600 To <strong>The</strong> Present,Julian Halsby & Paul Harris, Birlinn Ltd, 2010‘Six of the Best Painters Point the Way Forward’ Iain Galefor Scotland on Sunday, 30th January 2005A History of <strong>Scottish</strong> Art, Selina Skipworth & Bill Smith,Merrell, 2003‘Myths Remade’ Iain Gale for Scotland on Sunday, 2002Paul Reid, New Works, Phillip Long, Senior Curator,<strong>Scottish</strong> National <strong>Gallery</strong> of Modern Art, <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong><strong>Gallery</strong>, 2002Art Tomorrow, Edward Lucie Smith, Terrail, 2002‘Best of Young British’, New Statesman, July 2002Artists Eye Art Review. Main Feature, November 1998‘Rising Stars in the Arts Firmament: Paul Reid, JohnRussell Taylor’, <strong>The</strong> Times, 1999

74 | PAUL REIDPublished by <strong>The</strong> <strong>Scottish</strong> <strong>Gallery</strong> to coincide with the exhibitionPAUL REID: MYTHOLOGIES2 August – 4 September 2013Exhibition can be viewed online atwww.scottish-gallery.co.uk/paulreidISBN: 978-1-905146-81-9Designed by www.kennethgray.co.ukPhotography by William Van EslandPrinted by Barr PrintersAll rights reserved. No part of this catalogue may be reproduced inany form by print, photocopy or by any other means, without thepermission of the copyright holders and of the publishers.16 Dundas Street, Edinburgh EH3 6HZTel 0131 558 1200 Email mail@scottish-gallery.co.ukwww.scottish-gallery.co.ukRight: Actaeon, charcoal on paper, 75 x 56 cms

MYTHOLOGIES | 75

76 | PAUL REID