Mines Magazine Turns 100 - the Timothy and Bernadette Marquez ...

Mines Magazine Turns 100 - the Timothy and Bernadette Marquez ...

Mines Magazine Turns 100 - the Timothy and Bernadette Marquez ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

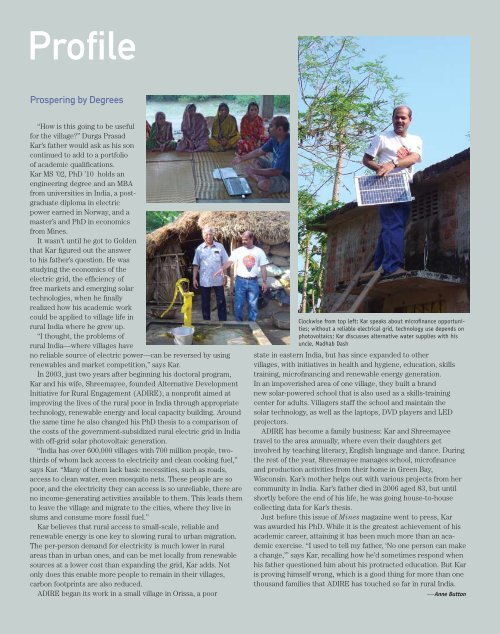

ProfileAlumniFast ForwardProspering by Degrees“How is this going to be usefulfor <strong>the</strong> village?” Durga PrasadKar’s fa<strong>the</strong>r would ask as his soncontinued to add to a portfolioof academic qualifications.Kar MS ’02, PhD ’10 holds anengineering degree <strong>and</strong> an MBAfrom universities in India, a postgraduatediploma in electricpower earned in Norway, <strong>and</strong> amaster’s <strong>and</strong> PhD in economicsfrom <strong>Mines</strong>.It wasn’t until he got to Goldenthat Kar figured out <strong>the</strong> answerto his fa<strong>the</strong>r’s question. He wasstudying <strong>the</strong> economics of <strong>the</strong>electric grid, <strong>the</strong> efficiency offree markets <strong>and</strong> emerging solartechnologies, when he finallyrealized how his academic workcould be applied to village life inrural India where he grew up.“I thought, <strong>the</strong> problems ofrural India—where villages haveno reliable source of electric power—can be reversed by usingrenewables <strong>and</strong> market competition,” says Kar.In 2003, just two years after beginning his doctoral program,Kar <strong>and</strong> his wife, Shreemayee, founded Alternative DevelopmentInitiative for Rural Engagement (ADIRE), a nonprofit aimed atimproving <strong>the</strong> lives of <strong>the</strong> rural poor in India through appropriatetechnology, renewable energy <strong>and</strong> local capacity building. Around<strong>the</strong> same time he also changed his PhD <strong>the</strong>sis to a comparison of<strong>the</strong> costs of <strong>the</strong> government-subsidized rural electric grid in Indiawith off-grid solar photovoltaic generation.“India has over 600,000 villages with 700 million people, twothirdsof whom lack access to electricity <strong>and</strong> clean cooking fuel,”says Kar. “Many of <strong>the</strong>m lack basic necessities, such as roads,access to clean water, even mosquito nets. These people are sopoor, <strong>and</strong> <strong>the</strong> electricity <strong>the</strong>y can access is so unreliable, <strong>the</strong>re areno income-generating activities available to <strong>the</strong>m. This leads <strong>the</strong>mto leave <strong>the</strong> village <strong>and</strong> migrate to <strong>the</strong> cities, where <strong>the</strong>y live inslums <strong>and</strong> consume more fossil fuel.”Kar believes that rural access to small-scale, reliable <strong>and</strong>renewable energy is one key to slowing rural to urban migration.The per-person dem<strong>and</strong> for electricity is much lower in ruralareas than in urban ones, <strong>and</strong> can be met locally from renewablesources at a lower cost than exp<strong>and</strong>ing <strong>the</strong> grid, Kar adds. Notonly does this enable more people to remain in <strong>the</strong>ir villages,carbon footprints are also reduced.ADIRE began its work in a small village in Orissa, a poorClockwise from top left: Kar speaks about microfinance opportunities;without a reliable electrical grid, technology use depends onphotovoltaics; Kar discusses alternative water supplies with hisuncle, Madhab Dashstate in eastern India, but has since exp<strong>and</strong>ed to o<strong>the</strong>rvillages, with initiatives in health <strong>and</strong> hygiene, education, skillstraining, microfinancing <strong>and</strong> renewable energy generation.In an impoverished area of one village, <strong>the</strong>y built a br<strong>and</strong>new solar-powered school that is also used as a skills-trainingcenter for adults. Villagers staff <strong>the</strong> school <strong>and</strong> maintain <strong>the</strong>solar technology, as well as <strong>the</strong> laptops, DVD players <strong>and</strong> LEDprojectors.ADIRE has become a family business: Kar <strong>and</strong> Shreemayeetravel to <strong>the</strong> area annually, where even <strong>the</strong>ir daughters getinvolved by teaching literacy, English language <strong>and</strong> dance. During<strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong> year, Shreemayee manages school, microfinance<strong>and</strong> production activities from <strong>the</strong>ir home in Green Bay,Wisconsin. Kar’s mo<strong>the</strong>r helps out with various projects from hercommunity in India. Kar’s fa<strong>the</strong>r died in 2006 aged 83, but untilshortly before <strong>the</strong> end of his life, he was going house-to-housecollecting data for Kar’s <strong>the</strong>sis.Just before this issue of <strong>Mines</strong> magazine went to press, Karwas awarded his PhD. While it is <strong>the</strong> greatest achievement of hisacademic career, attaining it has been much more than an academicexercise. “I used to tell my fa<strong>the</strong>r, ‘No one person can makea change,’” says Kar, recalling how he’d sometimes respond whenhis fa<strong>the</strong>r questioned him about his protracted education. But Karis proving himself wrong, which is a good thing for more than onethous<strong>and</strong> families that ADIRE has touched so far in rural India.—Anne Button46 Fall/Winter 2010