Study on USAID Non-Project Assistance Programs in

Study on USAID Non-Project Assistance Programs in

Study on USAID Non-Project Assistance Programs in

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

PN-ABW-490Policy Paper No. 12THE USE OF <strong>USAID</strong>’S NON-PROJECTASSISTANCE TO ACHIEVEHEALTH SECTOR POLICY REFORM IN AFRICA:A DISCUSSION PAPERSubmitted to:The Health and Human Resources Research and Analysis for Africa (HHRAA) <strong>Project</strong>Human Resources and Democracy Divisi<strong>on</strong>Office of Susta<strong>in</strong>able DevelopmentBureau for AfricaandPolicy and Sector Reform Divisi<strong>on</strong>Office of Health and Nutriti<strong>on</strong>Center for Populati<strong>on</strong>, Health and Nutriti<strong>on</strong>Bureau for Global Problems, Field Support and ResearchAgency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al DevelopmentBy:James C. Setzer and Molly L<strong>in</strong>dnerC<strong>on</strong>sultants, Abt Associates Inc.SEPTEMBER 1994HEALTH FINANCING AND SUSTAINABILITY (HFS) PROJECTABT ASSOCIATES INC., Prime C<strong>on</strong>tractor4800 M<strong>on</strong>tgomery Lane, Suite 600Bethesda, MD 20814 USATel: (301) 913-0500 Fax: (301) 652-3916Telex: 312638Management Sciences for Health, Subc<strong>on</strong>tractorThe Urban Institute, Subc<strong>on</strong>tractor

AID C<strong>on</strong>tract No. DPE-5974-Z-00-9026-00

ABSTRACTThis policy paper exam<strong>in</strong>es the experiences and effectiveness of us<strong>in</strong>g the U.S. Agency forInternati<strong>on</strong>al Development’s n<strong>on</strong>-project assistance (NPA) to support health sector objectives <strong>in</strong>sub-Saharan Africa. <strong>Programs</strong> <strong>in</strong> Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Togo, and Camero<strong>on</strong> are summarized. For eachcountry, background is provided <strong>on</strong> the health sector, and a summary and assessment of specific NPAprograms are provided.The primary focus of the paper is <strong>on</strong> health f<strong>in</strong>ance policy reforms that were promoted through<strong>USAID</strong>-supported NPA programs. It compares and c<strong>on</strong>trasts country experiences as they relate to NPA.The authors’ purpose is to encourage discussi<strong>on</strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>USAID</strong> of the effectiveness of us<strong>in</strong>g NPA as areform tool <strong>in</strong> policy development and the broader questi<strong>on</strong> of how to best support desired healthoutcomes <strong>in</strong> Africa.The paper provides a detailed assessment of three aspects of NPA programm<strong>in</strong>g: programdevelopment and design, program implementati<strong>on</strong>, and program evaluati<strong>on</strong>. The <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> sources werelimited to official program documentati<strong>on</strong>, and did not <strong>in</strong>clude field work. An extensive bibliography <strong>on</strong>the topics of n<strong>on</strong>-project assistance, policy reform, and health sector policy is <strong>in</strong>cluded.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTSThis report is part of the reasearch and analysis activities of the Health Care F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g and PrivateHealth Sector Development portfolio of the HHRAA project under the technical directi<strong>on</strong> of AbrahamBekele.i

TABLE OF CONTENTSLIST OF EXHIBITS .......................................................ACRONYMS ............................................................EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................ivvvi1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................... 12.0 METHODS ........................................................ 33.0 BACKGROUND .................................................... 54.0 EXPERIENCES WITH NPA IN THE HEALTH SECTOR UNDER THE DFA ......... 84.1 OVERVIEW .................................................. 85.0 NIGER .......................................................... 125.1 BACKGROUND .............................................. 125.2 HEALTH SECTOR ............................................ 125.2.1 The Niger Health Sector Support Grant (NHSSG) ................. 135.3 EXPERIENCES .............................................. 146.0 KENYA ......................................................... 166.1 BACKGROUND .............................................. 166.2 HEALTH SECTOR ............................................ 166.2.1 Kenya Health Care F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g Program (KHCF) .................. 176.3 EXPERIENCES .............................................. 187.0 NIGERIA ........................................................ 207.1 BACKGROUND .............................................. 207.2 HEALTH SECTOR ........................................... 217.2.1 The Nigeria Primary Health Care Support (NPHCS) Program ........ 227.3 EXPERIENCES .............................................. 238.0 TOGO ........................................................... 248.1 BACKGROUND .............................................. 248.2 HEALTH SECTOR ........................................... 248.2.1 Togo Health and Populati<strong>on</strong> Sector Support Program (HAPSS) ........ 258.3 EXPERIENCES .............................................. 269.0 CAMEROON ..................................................... 279.1 BACKGROUND .............................................. 279.2 HEALTH SECTOR ............................................ 279.2.1 Primary Health Care Subsector Reform (PHCSR) Program ........... 289.3 EXPERIENCES .............................................. 29ii

10.0 SUMMARY OF LESSONS LEARNED ................................... 3010.1 PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT AND DESIGN ......................... 3110.2 PROGRAM IMPLEMENTATION ................................. 3710.3 PROGRAM EVALUATION ..................................... 3811.0 CONCLUSIONS ................................................... 41BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................ 43iii

LIST OF EXHIBITSEXHIBIT 4-1DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC INDICATORS ................................ 9EXHIBIT 4-2SUMMARY OF NPA PROGRAMS ........................................... 11iv

ACRONYMSCIPDACDFAFHSPFMGFMOHGDPGNPHAPSSHFSHHRAAIMFIPCKHCFKNHLGAMCHMOHMOPHMOPHSANHIFNHSSGNPHCSP/PHCPHCSRSALSAPSDATCSPUNICEF<strong>USAID</strong>WHOCommodity Import ProgramDevelopment <strong>Assistance</strong> CommitteeDevelopment Fund for AfricaFamily Health Support <strong>Project</strong>Federal Military GovernmentFederal M<strong>in</strong>istry of HealthGross Domestic ProductGross Nati<strong>on</strong>al ProductHealth and Populati<strong>on</strong> Sector Support Program (Togo)Health F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g and Susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>Project</strong>Health and Human Resources Analysis for Africa <strong>Project</strong>Internati<strong>on</strong>al M<strong>on</strong>etary FundInterim Program of C<strong>on</strong>solidati<strong>on</strong>Kenya Health Care F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g ProgramKenyatta Nati<strong>on</strong>al HospitalLocal Government AuthorityMaternal Child HealthM<strong>in</strong>istry of HealthM<strong>in</strong>istry of Public HealthM<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health and Social AffairsNati<strong>on</strong>al Hospital Insurance FundNiger Health Sector Support GrantNigeria Primary Health Care Support ProgramPreventive and Primary Health CarePrimary Health Care Subsector Reform Program (Camero<strong>on</strong>)Structural Adjustment Lend<strong>in</strong>g Program (World Bank)Structural Adjustment ProgramSocial Dimensi<strong>on</strong>s of Adjustment ProgramTogo Child Survival and Populati<strong>on</strong> ProgramUnited Nati<strong>on</strong>s Children’s FundU.S. Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al DevelopmentWorld Health Organizati<strong>on</strong>v

EXECUTIVE SUMMARYAt the request of <strong>USAID</strong>’s Africa Bureau and the Health and Human Resources Analysis forAfrica <strong>Project</strong>, the Health F<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g and Susta<strong>in</strong>ability <strong>Project</strong> exam<strong>in</strong>ed the experiences of the UnitedStates Agency for Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (<strong>USAID</strong>) us<strong>in</strong>g n<strong>on</strong>-project assistance (NPA) to supporthealth sector objectives <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa. This paper summarizes the design, implementati<strong>on</strong>, andevaluati<strong>on</strong> experiences of NPA programs <strong>in</strong> Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Togo,, and Camero<strong>on</strong>. All fiveprograms were submitted to <strong>USAID</strong>; however, <strong>on</strong>ly three were authorized.The overall goal of these programs was to use NPA with<strong>in</strong> the health sector to achieve specificpolicy reform objectives and to provide f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources to programs and activities with<strong>in</strong> the sector.The purpose of this paper is to <strong>in</strong>itiate a discussi<strong>on</strong> with<strong>in</strong> <strong>USAID</strong> of the effectiveness of us<strong>in</strong>g NPA asa reform tool <strong>in</strong> policy development. This will, it is hoped, also promote a discussi<strong>on</strong> of the wider questi<strong>on</strong>of how to best support the development of health services and promote desired health outcomes <strong>in</strong> Africa.The experiences of the health sector NPA programs are exam<strong>in</strong>ed us<strong>in</strong>g sec<strong>on</strong>dary <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong>sources (PAIPS, PAAPS, project reports and documentati<strong>on</strong>, and evaluati<strong>on</strong> reports).All NPA programs transfer d<strong>on</strong>or resources to a host county to support ec<strong>on</strong>omic development.The NPA programs <strong>in</strong> the health sector <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa have all been developed as sector assistanceprograms. Sector assistance programs have two objectives: the direct transfer of f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources to thehost government and the support of sector specific host country <strong>in</strong>itiatives result<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> predef<strong>in</strong>ed policyreforms or implementati<strong>on</strong>. Sector assistance programs attempt to def<strong>in</strong>e reform agendas that addresspolicy and resource c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts to sector productivity, performance and output.All of the countries <strong>in</strong> this study experienced significant decl<strong>in</strong>es <strong>in</strong> their annual GDP growth ratess<strong>in</strong>ce the early 1980’s. Policy reform and development of the health sector <strong>in</strong> each of the countries hasbeen made more difficult by political <strong>in</strong>stability. In most sub-Saharan Africa countries, the public sectoris the primary source of the delivery of health care. This currently leaves many (and perhaps <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g)populati<strong>on</strong>s with limited access to services, decreased quality of care, and poor health outcomes. Facedwith this decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> services, d<strong>on</strong>or agencies and m<strong>in</strong>istries of health <strong>in</strong> many countries are attempt<strong>in</strong>g toimplement reforms and projects <strong>in</strong> the areas of health f<strong>in</strong>ance, primary care services, and plann<strong>in</strong>g andmanagement of health care services decentralizati<strong>on</strong>. The NPA programs discussed <strong>in</strong> this paper weredeveloped to support reforms <strong>in</strong> these areas.Health services <strong>in</strong> Niger are provided by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health and Social Affairs(MOPHSA), which emphasizes primary health care through vertical disease specific <strong>in</strong>terventi<strong>on</strong> programs.The Niger Health Sector Support Grant (NHSSG) was designed to complement and be implemented <strong>in</strong>collaborati<strong>on</strong> with other d<strong>on</strong>or (primarily World Bank) efforts <strong>in</strong> the sector to facilitate policy reform <strong>in</strong>the follow<strong>in</strong>g areas: cost recovery, cost c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ment, resource allocati<strong>on</strong>, pers<strong>on</strong>nel, health sectorplann<strong>in</strong>g, and populati<strong>on</strong> policy and resources. The program was judged by evaluators as be<strong>in</strong>g toocomplex for the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g human resources) and fiscal resources available. In additi<strong>on</strong>, fundswere not directly transferred to the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the reforms and, due to delays <strong>in</strong> theaccomplishment of certa<strong>in</strong> reforms, were not disbursed with<strong>in</strong> the assigned time frame. However, manyof the predef<strong>in</strong>ed health sector reforms have occurred s<strong>in</strong>ce the sign<strong>in</strong>g of the grant agreement.vi

The Kenyan health sector may be divided <strong>in</strong>to three sectors: public, voluntary, and private withthe majority of services provided by the public sector. Due to problems <strong>in</strong> f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g the expansi<strong>on</strong> ofprimary and preventive health care and services to under-served populati<strong>on</strong>s, the Kenyan Health CareF<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g Program (KHCF) was established. The KHCF program goals are to implement policy reforms<strong>in</strong> the areas of cost recovery, social f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g, and resource allocati<strong>on</strong>. The KHCF was effective <strong>in</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g, promot<strong>in</strong>g, and implement<strong>in</strong>g many of the def<strong>in</strong>ed reforms. However, these reforms were notaccomplished without difficulties. The cost-shar<strong>in</strong>g system orig<strong>in</strong>ally accepted by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Health(MOH) was annulled by the President <strong>on</strong>ly to be readopted and implemented a year later. Objecti<strong>on</strong>s arosearound the resource allocati<strong>on</strong> algorithms to be applied to primary and preventive services for budgetallocati<strong>on</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong>s. The implementati<strong>on</strong> of many reforms suffered due to the lack of comprehensive<strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> systems capable of m<strong>on</strong>itor<strong>in</strong>g and evaluat<strong>in</strong>g the effects of the reforms.Both public and private sectors provide curative health services <strong>in</strong> Nigeria. Due to the ec<strong>on</strong>omicdecl<strong>in</strong>e experienced by the country, the quality and quantity of health services has decl<strong>in</strong>ed. The NigeriaPublic Health Care Support Program was developed to support the transfer of resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities for theplann<strong>in</strong>g, management, and delivery of public health care services from federal to state levels, andredirect<strong>in</strong>g the emphasis from curative to preventive services. The program experienced delays <strong>in</strong> thedisbursement of funds caused by a lack of clear policy objectives. The implementati<strong>on</strong> benchmarks werenot completed with<strong>in</strong> the allotted time frame due <strong>in</strong> part to a lack of sufficient <strong>in</strong>itial analysis and technicalassistance.The Government of Togo (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the health sector) has become <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly dependent <strong>on</strong>d<strong>on</strong>or support. The M<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health provides the majority of services <strong>in</strong> Togo. Their goal is toimprove and expand service provisi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>in</strong> health facilities country-wide. The Togo Health and Populati<strong>on</strong>Sector Support Program (HAPSS) was developed to support the expansi<strong>on</strong> of curative, preventive, andprimary care services; improve access to family plann<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong>; <strong>in</strong>crease the availability of essentialdrugs and c<strong>on</strong>traceptives; and expand recurrent cost recovery mechanisms <strong>in</strong> the public sector. It wasdesigned to complement the $15.5 milli<strong>on</strong> Togo Child Survival and Populati<strong>on</strong> (TCSP) project. The TCSPproject was authorized <strong>in</strong> 1991 but was withdrawn <strong>in</strong> 1993. As a result, the HAPSS program was notauthorized. Nevertheless, several of the program’s policy reforms have been <strong>in</strong>stituted by the Governmentof Togo.S<strong>in</strong>ce 1986 Camero<strong>on</strong> has experienced a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> delivery of health services due to decreases<strong>in</strong> the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health (MOPH) budget. The goal of MOPH is to improve the delivery ofprimary health care services. The Primary Health Care Subsector Reform Program (PHCSR) wasestablished to implement a nati<strong>on</strong>wide primary care program. The PHCSR program was designed tosupport implementati<strong>on</strong> of recurrent cost recovery activities, develop nati<strong>on</strong>al standards for delivery ofservices, and <strong>in</strong>crease the availability of modern c<strong>on</strong>traceptives. The PHCSR program was neverauthorized by <strong>USAID</strong>; however, many policy reform changes that were def<strong>in</strong>ed by the program have been<strong>in</strong>stituted by the Government of Camero<strong>on</strong>.In order to promote discussi<strong>on</strong>, the less<strong>on</strong>s learned from experiences us<strong>in</strong>g NPA <strong>in</strong> the healthsector <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa may be grouped <strong>in</strong>to three areas: program development and design, programimplementati<strong>on</strong>, and program evaluati<strong>on</strong>.Program Development and Design: Before program development and design beg<strong>in</strong>s, a backgroundanalysis is necessary to allow for an understand<strong>in</strong>g of the policy envir<strong>on</strong>ment with<strong>in</strong> the country. Thisanalysis should be more detailed than that required for traditi<strong>on</strong>al project development. A thorough andh<strong>on</strong>est assessment of exist<strong>in</strong>g human resources and <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al capabilities must be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> thisvii

analysis. The development of the NPA reform program must not overlook the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al reforms andchanges that are required to support the policy reforms def<strong>in</strong>ed by the program. Sufficient resources mustbe devoted to promote these <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al reforms as well as the technical policy reforms def<strong>in</strong>ed by theprogram. In all three of the NPA programs implemented <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa, the lack of humanresources available to support the reform process appeared to have a negative impact <strong>on</strong> achievement ofprogram mandated reforms with<strong>in</strong> the established time frame. The development of human resourcesthrough tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g should be c<strong>on</strong>sidered as part of NPA programs.A more direct l<strong>in</strong>kage between the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>sible for reforms and the recipient of grantfunds may be effective <strong>in</strong> motivat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s to carry out program reforms. <strong>Programs</strong> should bedesigned to be flexible. Due to unforeseen problems such as political changes and time factors or policiesthat are made outside of the health sector, NPA policy reform agendas must be adaptable. In the NPAprograms that were exam<strong>in</strong>ed, the specific reform agendas appear to have helped ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> focus andattenti<strong>on</strong> <strong>on</strong> important health sector issues, when faced with these unforeseen problems. Another meansof ensur<strong>in</strong>g that policies rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>tact is to identify policies that may have high levels of support with<strong>in</strong>the exist<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al framework.Program Implementati<strong>on</strong>: NPA programs are <strong>in</strong>tended to quickly transfer funds to the hostcountry. However, as found <strong>in</strong> this study, the disbursement of funds often becomes a significantmanagement burden for the <strong>USAID</strong> missi<strong>on</strong> and the host country due to cumbersome track<strong>in</strong>g andadm<strong>in</strong>istrative requirements imposed <strong>on</strong> the funds. If additi<strong>on</strong>al resp<strong>on</strong>sibilities become too burdensomeand complicated, enthusiasm for NPA policy reform may dim<strong>in</strong>ish. In the countries <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the study,<strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al capacity build<strong>in</strong>g was an implied objective. In the future, it would appear advisable to developspecific benchmarks for <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al capacity build<strong>in</strong>g to be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the NPA reform agenda.Additi<strong>on</strong>al technical assistance resources must also be <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> NPA plann<strong>in</strong>g, if capacity build<strong>in</strong>gobjectives are to be met.Program Evaluati<strong>on</strong>: Direct evaluati<strong>on</strong> of the effectiveness of NPA supported policy reforms <strong>in</strong>br<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>g about desired health outcomes is difficult. All of the policy reforms <strong>in</strong> these countries may ormay not have occurred <strong>in</strong> the absence of the NPA programs. One of NPA’s pr<strong>in</strong>cipal roles may be topromote the <strong>in</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong> of certa<strong>in</strong> policy reforms with<strong>in</strong> a chang<strong>in</strong>g nati<strong>on</strong>al agenda. Some of the healthsector policies <strong>in</strong> these countries may not have rema<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>on</strong> the agenda without the efforts of NPA and,therefore, may have never been implemented.The establishment of direct l<strong>in</strong>ks between NPA goals of sector policy reform and resource transferis difficult. Policy reform may not resp<strong>on</strong>d to f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives as perceived by the NPA framework.L<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g people-level impact <strong>in</strong>dicators to specific policy reforms may not be feasible. This is true of notjust NPA programs but of efforts to support policy reform <strong>in</strong> general. Most African countries do not have<strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> systems capable of measur<strong>in</strong>g changes <strong>in</strong> people-level impact <strong>in</strong>dicators. Even when changesare measured, it is difficult to l<strong>in</strong>k those changes directly to policy reforms. It is more feasible to m<strong>on</strong>itorchanges <strong>in</strong> services delivered and utilized as a result of policy reform. The three- to five-year time frameof the programs <strong>in</strong> these countries appears to be too short for many of the projected outcomes of thestudied NPA programs.Overall, us<strong>in</strong>g NPA <strong>in</strong> the health sector has not been as successful as projected by <strong>USAID</strong>. Thereforms have taken l<strong>on</strong>ger than anticipated, build<strong>in</strong>g ownership for reforms has been difficult and timec<strong>on</strong>sum<strong>in</strong>g, the programs appear to have paid <strong>in</strong>sufficient attenti<strong>on</strong> to <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al reform as part of theNPA agenda, and the reforms c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the programs were, perhaps, too complex.viii

However, it can be noted that the countries with health sector NPA have made important andsignificant progress <strong>in</strong> the development of their health sectors. It may be that NPA has served to promotea number of policy changes and kept health policy issues <strong>on</strong> the nati<strong>on</strong>al agendas dur<strong>in</strong>g periods of<strong>in</strong>stability and transiti<strong>on</strong>. <strong>USAID</strong> should use the experiences of NPA to exam<strong>in</strong>e its efforts to support thec<strong>on</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ued development of the health sector <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa.ix

1.0 INTRODUCTIONThe purpose of this paper is to exam<strong>in</strong>e and analyze the experiences of the United States Agencyfor Internati<strong>on</strong>al Development (<strong>USAID</strong>) <strong>in</strong> the use of n<strong>on</strong>-project assistance (NPA) to support health sectorobjectives <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa, especially through the achievement of sector-wide reforms of healthf<strong>in</strong>ance policies. The analysis and discussi<strong>on</strong> of these NPA experiences was carried out by the HealthF<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g and Susta<strong>in</strong>ability (HFS) <strong>Project</strong> at the request of <strong>USAID</strong>’s Africa Bureau and the Health andHuman Resources Analysis for Africa (HHRAA) <strong>Project</strong>.<strong>USAID</strong> experience <strong>in</strong> the use of NPA with<strong>in</strong> the health sector is limited compared to that <strong>in</strong> othersectors (agriculture, educati<strong>on</strong>, etc). However, even these limited experiences provide important <strong>in</strong>sight<strong>in</strong>to the applicati<strong>on</strong> of the NPA mechanism to meet<strong>in</strong>g Agency objectives <strong>in</strong> the health sector.To date, health sector based NPA programs have been funded under the Development Fund forAfrica (DFA) and implemented <strong>in</strong> three African countries (Niger, Nigeria, Kenya). 1 In additi<strong>on</strong>, two othercountries (Togo and Camero<strong>on</strong>) developed NPA comp<strong>on</strong>ents which were <strong>in</strong>tended to be l<strong>in</strong>ked to andcomplement large health sector projects. In these latter <strong>in</strong>stances the projects were accepted but thecorresp<strong>on</strong>d<strong>in</strong>g NPA comp<strong>on</strong>ents were not authorized. 2 The experience of health sector NPA <strong>in</strong> each ofthese five African countries will be summarized with regard to the design of their programs. Clearly, theexperiences of Togo and Camero<strong>on</strong> are limited to this aspect of NPA programm<strong>in</strong>g. Implementati<strong>on</strong> andevaluati<strong>on</strong> issues will be exam<strong>in</strong>ed for <strong>on</strong>ly the NPA programs <strong>in</strong> Niger, Nigeria, and Kenya.The cases of both Botswana and Ghana have been excluded s<strong>in</strong>ce these NPA programs aredesigned to primarily address populati<strong>on</strong> policy issues and do not <strong>in</strong>clude the key health f<strong>in</strong>ance policyreforms that are the primary focus of this analysis.For the three NPA programs which will be the primary focus of this paper, Niger, Nigeria, andKenya, it is important to note that these programs have been <strong>in</strong> existence for a relatively short period oftime. The l<strong>on</strong>gest-stand<strong>in</strong>g NPA health program <strong>in</strong> Africa is that <strong>in</strong> Niger, which was authorized <strong>in</strong> 1986.This represents a relatively short time frame to draw c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s regard<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al reform and policyreform processes.1 It is important to note that the NPA program <strong>in</strong> Niger <strong>in</strong>cludes c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ality to promote policy reform with<strong>in</strong>the populati<strong>on</strong> sector as well.2 Health sector based NPA programs have also been undertaken <strong>in</strong> Chile, Philipp<strong>in</strong>es and Ecuador. Inadditi<strong>on</strong>, Botswana and Ghana have developed and implemented NPA programs designed to supportobjectives <strong>in</strong> the populati<strong>on</strong> sector (Niger’s NPA also <strong>in</strong>cluded populati<strong>on</strong> sector objectives).1

<strong>USAID</strong> has attempted to use NPA <strong>in</strong> the health sector to achieve specific policy reform objectivesand to provide resources to programs and activities with<strong>in</strong> the sector as well. The dual goal of NPA toachieve both of these objectives simultaneously is important and serves to dist<strong>in</strong>guish NPA from otherassistance mechanisms. This makes NPA an attractive and potentially powerful mechanism capable ofpromot<strong>in</strong>g wide rang<strong>in</strong>g and fundamental changes with<strong>in</strong> an entire sector or subsector (perhaps bey<strong>on</strong>dthose that traditi<strong>on</strong>al project mechanisms expect to achieve at similar fund<strong>in</strong>g levels). It also makes thedesign and implementati<strong>on</strong> of NPA complicated, its management time c<strong>on</strong>sum<strong>in</strong>g, and evaluati<strong>on</strong> difficult.NPA potentially provides <strong>USAID</strong> (and other d<strong>on</strong>ors as well) with an effective mechanism tosupport the development of host country health sectors al<strong>on</strong>g a mutually def<strong>in</strong>ed path. Alternatively, it maynot be prudent or possible to achieve both of these objectives through the use of a s<strong>in</strong>gle support orfund<strong>in</strong>g mechanism. Learn<strong>in</strong>g from these experiences may provide program planners with <strong>in</strong>sight necessaryto choose the most effective means of achiev<strong>in</strong>g sector objectives, especially when those objectives <strong>in</strong>cludeor are dependent up<strong>on</strong> significant policy reforms. A discussi<strong>on</strong> of NPA requires <strong>USAID</strong> to assess its role<strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g the development of health systems capable of dem<strong>on</strong>strat<strong>in</strong>g positive health outcomes. NPAis but <strong>on</strong>e possible means of support<strong>in</strong>g this process.Us<strong>in</strong>g experiences derived from <strong>USAID</strong>’s NPA health programs <strong>in</strong> Africa, this paper will:Synthesize less<strong>on</strong>s learned as they relate to the design, implementati<strong>on</strong>, and evaluati<strong>on</strong> ofhealth sector NPA <strong>in</strong> Niger, Kenya, and Nigeria (design issues related to proposed NPAprograms <strong>in</strong> Togo and Camero<strong>on</strong> have been <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> the relevant secti<strong>on</strong>s); andDiscuss the effectiveness of NPA as a health sector policy development and reform tool,and attempt to formulate recommendati<strong>on</strong>s <strong>on</strong> circumstances under which NPA may beused most effectively.<strong>USAID</strong>’s desire to exam<strong>in</strong>e NPA <strong>in</strong> the health sector is important if the agency is to c<strong>on</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ue toplay a leadership role <strong>in</strong> the support of health policy reform <strong>in</strong> Africa. Exam<strong>in</strong>ati<strong>on</strong> of NPA’s impact <strong>in</strong>achiev<strong>in</strong>g health policy reform also serves to promote discussi<strong>on</strong> and dialogue around issues bey<strong>on</strong>d the<strong>in</strong>dividual programs or the specific role or success of NPA <strong>in</strong> general. These broader issues, while bey<strong>on</strong>dthe scope of this paper, relate to:The nature of policy reform and decisi<strong>on</strong> mak<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the African c<strong>on</strong>text;The need to encourage policy reform versus a focus <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>on</strong> assistance to program and/orproject implementati<strong>on</strong>;The means by which all d<strong>on</strong>ors may best promote political <strong>in</strong>terest <strong>in</strong> policy reform aswell as a necessary sense of ownership and commitment;The <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al and human resources which must be <strong>in</strong> place to undertake policy analysisand reform programs; andThe role of d<strong>on</strong>ors <strong>in</strong> the policy reform process.These questi<strong>on</strong>s are clearly relevant to d<strong>on</strong>or efforts to support the development of efficient,quality and susta<strong>in</strong>able health services. NPA offers important <strong>in</strong>sight <strong>in</strong>to <strong>on</strong>e of the mechanisms used by<strong>USAID</strong> to promote such development.2

2.0 METHODSThis is a comparative study of health sector based NPA programs <strong>in</strong> Africa to date. It is <strong>in</strong>tendedto focus primarily <strong>on</strong> health f<strong>in</strong>ance policy reforms that were promoted through <strong>USAID</strong> supported NPAprograms. The analysis is based <strong>on</strong> sec<strong>on</strong>dary <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> sources (PAIPS, PAADs, project reports anddocumentati<strong>on</strong>, and evaluati<strong>on</strong> reports) and exam<strong>in</strong>es all three authorized programs and two programswhich were developed and submitted but not authorized by <strong>USAID</strong>.It represents <strong>on</strong>e of the few attempts to exam<strong>in</strong>e all of these health sector programs as a meansof exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g the effectiveness of NPA programs <strong>in</strong> support<strong>in</strong>g policy reform programs. Its ma<strong>in</strong> focusis to compare and c<strong>on</strong>trast country experiences as they relate to NPA rather than to describe <strong>in</strong> great detaileach of the country programs or their implementati<strong>on</strong>. Other important and relevant discussi<strong>on</strong>s of NPAand health policy reform <strong>in</strong> Africa have been provided by both Foltz and D<strong>on</strong>alds<strong>on</strong>. This analysis ismeant to complement rather than replace those.The pr<strong>in</strong>cipal sources of <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> for this study were <strong>USAID</strong> documentati<strong>on</strong> of the NPAprograms as well as Agency reports and papers c<strong>on</strong>cern<strong>in</strong>g NPA as a fund<strong>in</strong>g and assistance mechanism.Unfortunately <strong>USAID</strong> does not ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> a complete library or repository of all project documentati<strong>on</strong>.Informati<strong>on</strong> is scattered between Wash<strong>in</strong>gt<strong>on</strong> offices and the <strong>in</strong>dividual country missi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>in</strong>volved. As aresult, this paper does not necessarily reflect all relevant documents ever produced <strong>on</strong> the subject of healthsector based NPA <strong>in</strong> Africa. It must also be noted that many of these sources were not written to providethe basis for policy analysis. They are primarily <strong>in</strong>ternal <strong>USAID</strong> documents <strong>in</strong>tended to def<strong>in</strong>e complexenvir<strong>on</strong>ments and reform agendas <strong>in</strong> terms of "progress" toward goals def<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> program documents. Assuch, they raise questi<strong>on</strong>s as to the mean<strong>in</strong>g of "success" and "ownership" with<strong>in</strong> the c<strong>on</strong>text of policyreform and development assistance. This paper will use these terms, then, with<strong>in</strong> the c<strong>on</strong>text of <strong>USAID</strong>’sefforts to evaluate the ability of the NPA programs to support the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al and policy reforms def<strong>in</strong>edby the programs.Additi<strong>on</strong>al <strong>in</strong>sight is the result of the pers<strong>on</strong>al experiences of the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal author and the HFSproject <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g, implement<strong>in</strong>g, and evaluat<strong>in</strong>g health sector NPA programs.The available resources did not permit field work to be carried out as part of the writ<strong>in</strong>g of thispaper. The authors therefore relied up<strong>on</strong> the observati<strong>on</strong>s, analyses, and op<strong>in</strong>i<strong>on</strong>s of others as found <strong>in</strong>official program documentati<strong>on</strong>. As a result, it is not always easy to separate the effects of time, place,and pers<strong>on</strong> from those of structure, design, and implementati<strong>on</strong>. It is clear that all play a significant role<strong>in</strong> the ability of any program or project to achieve its objectives. This is not menti<strong>on</strong>ed as an excuse forshortcom<strong>in</strong>gs found <strong>in</strong> the analysis. Instead it is <strong>in</strong>cluded as an acknowledgment of the limitati<strong>on</strong>s ofassess<strong>in</strong>g the impact of complex assistance programs through the use of sec<strong>on</strong>dary sources.3

The difficulties <strong>in</strong> exam<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g NPA through this method come from the limited number of healthsector programs which have been implemented and basic differences <strong>in</strong> their design (see overview secti<strong>on</strong>below). It appears that <strong>in</strong> many cases the design and experiences of the <strong>in</strong>dividual programs are notsufficiently comparable to isolate <strong>in</strong>dividual factors affect<strong>in</strong>g the success of a particular program. Thiscomplicates the task of relat<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>dividual experiences to c<strong>on</strong>clusi<strong>on</strong>s about the NPA process. While eachof the programs has been evaluated by <strong>USAID</strong> and external sources accord<strong>in</strong>g to program specific<strong>in</strong>dicators of "success" (as def<strong>in</strong>ed by <strong>USAID</strong> and the programs themselves), there is no general c<strong>on</strong>sensusas to <strong>in</strong>dicators of success for health policy reform programs. The reader is referred to Foltz, "PolicyReform and N<strong>on</strong>-<strong>Project</strong> <strong>Assistance</strong>: Framework for Analysis" for a discussi<strong>on</strong> of this subject.4

3.0 BACKGROUNDN<strong>on</strong>-project assistance that focuses <strong>on</strong> policy reforms <strong>in</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>gle sector such as health is <strong>on</strong>e ofseveral types of NPA. The follow<strong>in</strong>g provides a brief discussi<strong>on</strong> of the variety of purposes, forms, andimplementati<strong>on</strong> mechanisms that NPA may take.NPA, also referred to as program assistance, is generally characterized by the transfer of d<strong>on</strong>orresources as foreign exchange and/or commodities to support host country ec<strong>on</strong>omic development. Thesetransfers are often seen as a rapid disbursement mechanism <strong>in</strong>tended to provide balance of payments andbudgetary relief to the host country’s ec<strong>on</strong>omy or as a means of support<strong>in</strong>g the development of a particularsector. <strong>Programs</strong> of policy c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ality may be attached to such transfer programs so that NPA is oftenseen as hav<strong>in</strong>g two basic objectives: direct transfer of f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources and policy reform.However, the use of NPA to support host country policy reform is, at times, c<strong>on</strong>sidered sec<strong>on</strong>daryand <strong>in</strong> general "the basic purpose (of NPA) rema<strong>in</strong>s <strong>on</strong>e of support" (DAC, 1986). NPA has been usedextensively by <strong>USAID</strong> <strong>in</strong> all regi<strong>on</strong>s. In 1986 <strong>USAID</strong>’s Development <strong>Assistance</strong> Committee (DAC)estimated that NPA was "the largest s<strong>in</strong>gle type of d<strong>on</strong>or assistance" (DAC, 1986).NPA closely resembles mechanisms employed by other d<strong>on</strong>or organizati<strong>on</strong>s to promote hostgovernment policy review and reform. The World Bank’s Structural Adjustment Lend<strong>in</strong>g (SAL) programand the Time Slice Operati<strong>on</strong>s funded through the Inter-American Development Bank are examples ofsuch programs. The Internati<strong>on</strong>al M<strong>on</strong>etary Fund (IMF) also frequently l<strong>in</strong>ks resource transfers to policyreform c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s. The major similarity between the programs of each of these d<strong>on</strong>ors and NPA programsis that all are resource transfer programs driven by meet<strong>in</strong>g c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s precedent l<strong>in</strong>ked to a policy reformagenda. The policy reform agendas promoted through these mechanisms are frequently broad ec<strong>on</strong>omicprograms rather than sector specific agendas for reform.With<strong>in</strong> <strong>USAID</strong>, NPA may take several dist<strong>in</strong>ct forms:Cash Transfer/Payment: A cash transfer is the deposit of foreign exchange funds (dollars)directly <strong>in</strong>to the account of the host government. This transfer is not directly tied to eithergoods or services. These funds can be used to provide immediate balance of paymentsand/or government budget support. They are often used as part of stabilizati<strong>on</strong> efforts andgeneral ec<strong>on</strong>omic policy reform programs. Governments can use the funds transferred asforeign exchange to pay for public sector import requirements or can use them to purchaselocal currency to be used to f<strong>in</strong>ance general government expenditures or to f<strong>in</strong>ancespecific development activities. Cash transfers are c<strong>on</strong>sidered the "purest" form of NPAs<strong>in</strong>ce the end use of the transferred funds is <strong>on</strong>ly <strong>in</strong>directly c<strong>on</strong>trolled or programmed bythe U.S. government.Commodity Import (or Support) Program (CIP): These programs provide a quickdispers<strong>in</strong>g mechanism <strong>in</strong> which dollars are made available to the host government <strong>in</strong> orderto f<strong>in</strong>ance general import requirements of specified categories of commodities (producti<strong>on</strong><strong>in</strong>puts rather than c<strong>on</strong>sumer goods). The sale of these commodities generates localcurrencies to be spent <strong>in</strong> a manner that is agreed up<strong>on</strong> by both host and U.S.governments. These uses generally <strong>in</strong>volve host government budget expenditures and/ordevelopment projects. The degree to which uses of these local currencies are programmedor "projectized" <strong>in</strong> advance varies by regi<strong>on</strong> and country.5

Public Law 480, Title I: Until the law was changed <strong>in</strong> 1990, <strong>USAID</strong> had the authority t<strong>on</strong>egotiate highly c<strong>on</strong>cessi<strong>on</strong>al loans to host countries <strong>in</strong> order to f<strong>in</strong>ance the purchase ofU.S. agricultural commodities. These commodities were sold <strong>on</strong> the local market by therecipient government as a means of generat<strong>in</strong>g local currencies. The degree to which TitleI agreements required recipient governments to carry out policy, regulatory oradm<strong>in</strong>istrative reforms, and/or the programm<strong>in</strong>g of local currencies for specific uses (oftenreferred to as "self-help measures") varied from agreement to agreement. In 1990, TitleI became a market development program adm<strong>in</strong>istered by the U.S. Department ofAgriculture.Public Law 480, Title III: Until the U.S. C<strong>on</strong>gress changed the law <strong>in</strong> 1990, Title IIIprograms resembled Title I (c<strong>on</strong>cessi<strong>on</strong>al loans to purchase U.S. commodities) but werelimited to IDA eligible countries, had much more rigorous "self-help" requirements(<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g cumbersome procedures for the use of local currency), and permittedforgiveness of debt when those requirements were met. S<strong>in</strong>ce 1990, <strong>USAID</strong> has beenauthorized to use the new Title III to provide grant assistance to IDA eligible countriesto purchase U.S. commodities and requires recipient governments to carry out specificpolicy, regulatory, or adm<strong>in</strong>istrative reforms.Sector <strong>Assistance</strong>: Program sector assistance is <strong>in</strong>tended to address policy c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts tosector productivity and output and/or address resource c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts with<strong>in</strong> a specifiedsector. Like CIPs these programs may <strong>in</strong>volve significant commodity imports andgenerati<strong>on</strong> of local currencies. Unlike CIPs, however, they generally focus <strong>on</strong> a s<strong>in</strong>glesector and its identified resource and policy c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts. They are justified more often <strong>on</strong>the basis of the policy c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts and the need for policy reform than the need forresource transfers to the specific sector. An important aspect of this type of program isc<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ality. Resource transfer under sector assistance type programs is directly tied tothe host government’s meet<strong>in</strong>g a predef<strong>in</strong>ed series of c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s precedent l<strong>in</strong>ked toidentified sector policy reforms. Often the resources are divided <strong>in</strong>to tranches which arereleased periodically (annually), c<strong>on</strong>t<strong>in</strong>gent up<strong>on</strong> the successful completi<strong>on</strong> of theappropriate c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s precedent.The NPA programs <strong>in</strong> the health sector <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa have all been designed as sectorassistance type programs. All specify country agendas for the review and reform of policies with<strong>in</strong> thehealth sector (the specific policy reform agendas supported by each of the programs will be describedbelow). They differ, however, with regard to the degree of specificity with which the uses of the resourcesto be transferred are programmed jo<strong>in</strong>tly by the host government and <strong>USAID</strong>. They also differ <strong>in</strong> thedegree to which the NPA programs are directly tied to or comb<strong>in</strong>ed with "projectized" resources such astechnical assistance, commodities, vehicles, salaries, travel, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, <strong>in</strong>frastructure, etc. to be used <strong>in</strong>support of the NPA policy review and reform agenda or its implementati<strong>on</strong>.The "Revised Africa Bureau NPA Guidel<strong>in</strong>es" (<strong>USAID</strong> 1990) characterize the differences betweenNPA and project assistance as based up<strong>on</strong> the specificity with which the end use of <strong>USAID</strong> funds isdef<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> advance. "NPA resources are provided <strong>in</strong> a ’generalized’ manner" and "not directly l<strong>in</strong>ked toprojectized expenditures." This dist<strong>in</strong>cti<strong>on</strong> holds true for the health and other sectors.6

4.0 EXPERIENCES WITH NPA IN THE HEALTH SECTORUNDER THE DFA4.1 OVERVIEWWhile each of the NPA experiences <strong>in</strong> the five countries described <strong>in</strong> this paper is dist<strong>in</strong>ctive andunique, there are attributes and characteristics which the countries share.From an ec<strong>on</strong>omic perspective, all of the countries where health sector NPA programs have beendeveloped—Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Togo and Camero<strong>on</strong>—have experienced, s<strong>in</strong>ce the early 1980s, adecl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> their annual GDP growth rates. For example, Nigeria’s annual GDP growth rate from 1970-80was 4.6 percent. In the next decade, 1980-91, this rate decl<strong>in</strong>ed to 1.9 percent, while the annual <strong>in</strong>flati<strong>on</strong>rate climbed to 18 percent. Niger, whose growth rate <strong>in</strong> the 1970s was <strong>on</strong>ly 1.7 percent, decl<strong>in</strong>ed to a rateof −1.0 dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s.Ec<strong>on</strong>omic resources allocated to the health sector have been <strong>in</strong>sufficient to support the deliveryof free health services as mandated by nati<strong>on</strong>al policies <strong>in</strong> all of the countries. Limited resources with<strong>in</strong>the health sector <strong>in</strong> the 1980s were <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly c<strong>on</strong>sumed by pers<strong>on</strong>nel costs. The lack of overallec<strong>on</strong>omic growth and development, especially <strong>in</strong> the health sector, has been the catalyst for many countriesto reform policies <strong>in</strong> order to expand the f<strong>in</strong>ancial bases for health service delivery. Exhibit 4-1 showsseveral key demographic and ec<strong>on</strong>omic <strong>in</strong>dicators for the countries studied.Politically, while all five countries have made attempts at establish<strong>in</strong>g multi-party democraticstates, the attempts have not come free of turbulence or unrest. All five countries have experienced a highdegree of political <strong>in</strong>stability, with frequent changes of people, policies, and offices. With such fluidity,l<strong>on</strong>g-term plann<strong>in</strong>g and policy reform processes have been difficult to develop and susta<strong>in</strong>.The public sector is the pr<strong>in</strong>cipal force <strong>in</strong> the delivery of health services <strong>in</strong> the countries identified.Some countries, such as Kenya, have a relatively mixed public, private, and voluntary health system.Others, such as Niger, have a relatively weak private sector, so the resp<strong>on</strong>sibility of health care falls up<strong>on</strong>the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health and Social Affairs. Comm<strong>on</strong> obstacles with<strong>in</strong> the health sector have beenthe lack of resources (both human and f<strong>in</strong>ancial), a focus <strong>on</strong> curative as opposed to preventive or primarycare services, an overly centralized system of plann<strong>in</strong>g and management of services, and <strong>in</strong>efficient andsuboptimal allocati<strong>on</strong> of resources with<strong>in</strong> the health sector. The overall effect has been to leavepopulati<strong>on</strong>s with limited access to services, decreased quality of care, and poor health outcomes.7

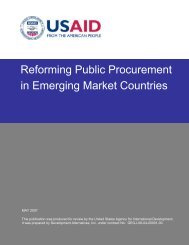

EXHIBIT 4-1DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC INDICATORSCountryPopulati<strong>on</strong>(milli<strong>on</strong>s,1991)LifeExpectancyat Birth, 1991InfantMortality Rate(per 1,000live births)1991 GDP(billi<strong>on</strong>s ofdollars)1991 GNPper capita(dollars)1990 Percentof GDP tohealth1990 Percentof GDP tohealth frompublic sector1990 percapita totalhealthexpenditure(<strong>in</strong> dollars)Niger 7.9 46 126 2.3 300 5 3.4 16Nigeria 99 52 85 34.1 340 2.7 1.2 9Kenya 25 59 67 7.1 340 4.3 2.7 16Togo 3.8 54 87 1.6 410 4.1 2.5 18Camero<strong>on</strong> 11.9 55 64 11.7 850 2.6 1 24Sources: Infant mortality rates from "1994 State of the World’s Children Report," UNICEF; populati<strong>on</strong> and ec<strong>on</strong>omic <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> from 1993 "WorldDevelopment Report," World Bank.8

The ec<strong>on</strong>omic, political and health envir<strong>on</strong>ments <strong>in</strong> these countries have provided the frameworkand motivati<strong>on</strong> toward acti<strong>on</strong> for d<strong>on</strong>or agencies and m<strong>in</strong>istries of health. Overall policy reform goalsfocus<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong> the emphasis of primary care, decentralizati<strong>on</strong>, and health f<strong>in</strong>ance reform have been centralto many d<strong>on</strong>or agendas, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the NPA health programs which are exam<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> this report. While eachof the identified countries—Niger, Nigeria, Kenya, Togo and Camero<strong>on</strong>—are unique <strong>in</strong> their situati<strong>on</strong>s,the reform agendas of the health sector NPAs developed for these countries have focused <strong>on</strong> a limitednumber of important areas for reform. They are:Health f<strong>in</strong>ance reform: Each of the reform agendas <strong>in</strong>cludes reforms and implementati<strong>on</strong>steps <strong>in</strong>tended to <strong>in</strong>crease the f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources available for the delivery of healthservices. Included <strong>in</strong> this area are reforms to improve the allocati<strong>on</strong> of resources with<strong>in</strong>the health sector as well.Increased emphasis <strong>on</strong> primary care: Several of the programs were developed to supportan <strong>in</strong>creased emphasis <strong>on</strong> services delivered at the primary level. This is <strong>in</strong>tended to<strong>in</strong>crease access and efficiency.Decentralizati<strong>on</strong> of plann<strong>in</strong>g and management of health services. These reform measuresare <strong>in</strong>tended to improve health resource allocati<strong>on</strong> decisi<strong>on</strong>s and the ability of the healthsystem to resp<strong>on</strong>d to local and community needs.The NPA programs developed for the health sectors <strong>in</strong> Niger, Kenya, Nigeria, Togo, andCamero<strong>on</strong> are summarized <strong>in</strong> Exhibit 4-2 below.9

EXHIBIT 4-2SUMMARY OF NPA PROGRAMSNPA Comp<strong>on</strong>ents Niger Nigeria Kenya Togo Camero<strong>on</strong>Program TitleNiger Health SectorSupport Grant(NHSSG)Nigeria PrimaryHealth Care SupportProgram (NPHCS)Kenya Health CareF<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g Program(KHCF)Togo Health andPopulati<strong>on</strong> SectorSupport Program(HAPSS)Primary HealthCare SubsectorReform Program(PHCSR)Authorized July 1986 July 1989 August 1989 — —Fund<strong>in</strong>g$17.2 milli<strong>on</strong>·$15 milli<strong>on</strong>amended to $17.2$36 milli<strong>on</strong>·$25 milli<strong>on</strong> amendedto $36$9.7 milli<strong>on</strong> ($6 milli<strong>on</strong>) ($5 milli<strong>on</strong>)Disbursements$4.5 milli<strong>on</strong>(1992)$25 milli<strong>on</strong>(1992)$4.6 milli<strong>on</strong>(1992)M<strong>on</strong>itor<strong>in</strong>g/Evaluati<strong>on</strong> Comp<strong>on</strong>entNo formal system;resp<strong>on</strong>sibilityto technicalassistance teamNo formal systemNo formal system;resp<strong>on</strong>sibilityto technicalassistance teamPolicy Reform Areas·Cost Recovery·Cost C<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ment,especiallyhospitals·Resource allocati<strong>on</strong>·Human resources·Decentralizati<strong>on</strong>·Transfer ofresp<strong>on</strong>sibility forplann<strong>in</strong>g, managementand deliveryof services·Shift <strong>in</strong> emphasisfrom curative topreventive·Promoti<strong>on</strong> ofprivatizati<strong>on</strong>·Cost recovery·Social f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g·Improved resourceallocati<strong>on</strong>·Expansi<strong>on</strong> of privatesector <strong>in</strong> delivery ofservices, drugimportati<strong>on</strong> anddistributi<strong>on</strong>·Improved access tofamily plann<strong>in</strong>g<strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong>·Cost recovery·Legal foundati<strong>on</strong>for cost recovery·Creati<strong>on</strong> ofnati<strong>on</strong>al servicestandards·Improved accessto familyplann<strong>in</strong>gmaterials and<strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong>C<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s Precedent 60(<strong>in</strong> five tranches)18(<strong>in</strong> three tranches)23(<strong>in</strong> three tranches)14(<strong>in</strong> three tranches)8(<strong>in</strong> three tranches)10

5.0 NIGER5.1 BACKGROUNDAfter a decade of rapid growth, Niger’s ec<strong>on</strong>omic prospects began to decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the early 1980s.This was set off by a decrease <strong>in</strong> the world price for uranium and a number of years of drought.Government expenditures had rapidly risen <strong>in</strong> the 1970s, with the deficits f<strong>in</strong>anced from external sources.Dur<strong>in</strong>g the 1980s, the Government of Niger adopted a number of austerity measures to restra<strong>in</strong> overallpublic sector spend<strong>in</strong>g under both IMF Standby and World Bank Structural Adjustment programs.Together with the IMF Stand-by Arrangements, the government began an adjustment process under theInterim Program of C<strong>on</strong>solidati<strong>on</strong> (IPC) <strong>in</strong> 1984-1985. The IPC provided new policy directi<strong>on</strong>s <strong>in</strong> severalareas, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g changes <strong>in</strong> public <strong>in</strong>vestment spend<strong>in</strong>g, restructur<strong>in</strong>g of state-owned enterprises, and costrecovery measures for public services.The IPC was complemented <strong>on</strong> a sectoral level by the <strong>USAID</strong> Agricultural Sector DevelopmentGrant which was authorized <strong>in</strong> 1984. It was also followed by the World Bank SAC program which wasc<strong>on</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> 1986 and focused <strong>on</strong> chang<strong>in</strong>g expenditures <strong>in</strong> the social service sector, together with thepublic enterprise and agricultural sectors. External aid <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly became an important source off<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g for all government operati<strong>on</strong>s. By 1991, the government was operat<strong>in</strong>g us<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g fromd<strong>on</strong>ors while barely manag<strong>in</strong>g to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> payments of civil servant salaries.The political shifts toward more democratic forms of government which began <strong>in</strong> the late 1980shave been encourag<strong>in</strong>g, but have at the same time been a source of significant disrupti<strong>on</strong> to the c<strong>on</strong>ductof rout<strong>in</strong>e bus<strong>in</strong>ess with<strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>istries. They have created an envir<strong>on</strong>ment of uncerta<strong>in</strong>ty for thosec<strong>on</strong>cerned with policy and <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al reform, exact<strong>in</strong>g a high toll <strong>on</strong> policy and <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al developmentefforts undertaken dur<strong>in</strong>g this period.5.2 HEALTH SECTORHealth services <strong>in</strong> Niger are provided almost exclusively by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Public Health andSocial Affairs (MOPHSA). 3 An extensive publicly operated and f<strong>in</strong>anced health care <strong>in</strong>frastructure exists<strong>in</strong> the country. This <strong>in</strong>cludes hospitals <strong>in</strong> all the departmental capitals, arr<strong>on</strong>dissement level health centersand over 200 rural dispensaries. Niger attempts to provide access to health services to its people througha strategy which emphasizes primary health care which depends heavily <strong>on</strong> a number of vertical (largelyn<strong>on</strong>-<strong>in</strong>tegrated) disease-specific <strong>in</strong>terventi<strong>on</strong> programs. The formal system of hospitals, medical centers,maternity units and dispensaries is supplemented by a nati<strong>on</strong>al program of village health teams, which<strong>in</strong>clude volunteer village health workers and traditi<strong>on</strong>al birth attendants. Although these teams have been<strong>in</strong> operati<strong>on</strong> s<strong>in</strong>ce 1974, their activities and the impact of their presence <strong>on</strong> the health of the populati<strong>on</strong>is largely unknown.<strong>USAID</strong> has provided assistance to the health sector <strong>in</strong> Niger s<strong>in</strong>ce the mid-1970s and is the majord<strong>on</strong>or to the primary health care program. In 1978 AID <strong>in</strong>itiated the $15 milli<strong>on</strong> Rural Health3 Unlike many other countries <strong>in</strong> West Africa, the private sector (for-profit, church run and n<strong>on</strong>-profit/NGOoperated) is relatively undeveloped.11

Improvement <strong>Project</strong>. RHIP f<strong>in</strong>anced the recruitment, tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, and supervisi<strong>on</strong> of village health teams;tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of health cadres; and the c<strong>on</strong>structi<strong>on</strong>, repair, and equipment for rural health facilities. RHIP wasdesigned primarily to provide budgetary support to the primary health care (especially the village healthteam) program and there was little c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>ality associated with the provisi<strong>on</strong> of resources to theMOPHSA <strong>in</strong> its design.Despite the development of a large delivery system <strong>in</strong>frastructure and supportive health policies,a pre-NPA sector analysis c<strong>on</strong>ducted <strong>in</strong> 1986 identified significant weaknesses <strong>in</strong> the health care deliverysystem <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g:Inadequate management and plann<strong>in</strong>g, the lack of <strong>in</strong>tegrati<strong>on</strong> of ec<strong>on</strong>omic and f<strong>in</strong>ancialfactors <strong>in</strong>to health plans, and weak central adm<strong>in</strong>istrative structures and <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s;An imbalance <strong>in</strong> the allocati<strong>on</strong> of funds between preventive and curative care pers<strong>on</strong>neland material, and between rural and urban populati<strong>on</strong>s relative to the stated objectives ofpromot<strong>in</strong>g primary and preventive care;A lack of <strong>in</strong>tegrati<strong>on</strong> of exist<strong>in</strong>g services and shortage of services <strong>in</strong> many areas;Inadequate support of pers<strong>on</strong>nel, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>-service tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g, supervisi<strong>on</strong>, materials, andsupplies;Lack of health care f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g policies that address the c<strong>on</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ued prospects for poor (oreven negative) growth <strong>in</strong> budgetary resources <strong>in</strong> the near future;Inefficient spend<strong>in</strong>g practices and an absence of cost c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ment measures;Lack of an <strong>in</strong>tegrated nati<strong>on</strong>al health plan, comb<strong>in</strong>ed with the timely, reliable, andcomprehensive <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> about services, resources, and the populati<strong>on</strong>’s health status.5.2.1 The Niger Health Sector Support Grant (NHSSG)In resp<strong>on</strong>se to the c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts identified by its analysis of the health sector <strong>in</strong> 1986, <strong>USAID</strong>designed and authorized the Niger Health Sector Support Grant (NHSSG) as an NPA program for thehealth sector. As the first health sector NPA program <strong>in</strong> Africa, it has the l<strong>on</strong>gest history of any of thehealth sector NPA programs funded under the DFA. Much of the design and mechanisms forimplementati<strong>on</strong> were modeled <strong>on</strong> <strong>USAID</strong>’s experiences with NPA <strong>in</strong> the agriculture sector <strong>in</strong> Niger.In 1986 the orig<strong>in</strong>al NHSSG grant agreement to provide $15 milli<strong>on</strong> to the health sector over afive-year period was signed. Release of $10.5 milli<strong>on</strong> <strong>in</strong> tranches over a five-year period was c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>edup<strong>on</strong> achievement of specified policy review and reform benchmarks ("c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>s precedent"). Therema<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g $4.5 milli<strong>on</strong> was programmed <strong>in</strong> support of technical assistance and tra<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g. An additi<strong>on</strong>al $2.2milli<strong>on</strong> for project assistance was added to that sum when the NHSSG was extended <strong>in</strong> 1990 (it has s<strong>in</strong>cebeen extended a sec<strong>on</strong>d time with completi<strong>on</strong> now scheduled <strong>in</strong> 1995).The NHSSG was designed to complement and be implemented <strong>in</strong> close collaborati<strong>on</strong> with otherd<strong>on</strong>or efforts <strong>in</strong> the sector. The most important area of collaborati<strong>on</strong> was the World Bank Health <strong>Project</strong>,which supports policy reform efforts of the Government of Niger undertaken as part of the StructuralAdjustment Credit program.12

The NHSSG <strong>in</strong>cluded numerous benchmarks <strong>in</strong>tended to support and facilitate policy review andreform <strong>in</strong> the follow<strong>in</strong>g six areas:Cost recovery: implement and <strong>in</strong>crease cost recovery measures for curative services(hospital and n<strong>on</strong>-hospital) <strong>in</strong> order to improve susta<strong>in</strong>ability of public health services;Cost c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ment: c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> unit costs for hospital services and drug purchas<strong>in</strong>g anddistributi<strong>on</strong> <strong>in</strong> order to make more efficient use of available f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources;Resource allocati<strong>on</strong>: reallocate MOPHSA f<strong>in</strong>ancial resources to promote <strong>in</strong>creasedspend<strong>in</strong>g <strong>on</strong> primary and sec<strong>on</strong>dary services, and to allow a proporti<strong>on</strong>ally larger budgetfor c<strong>on</strong>sumable supplies;Pers<strong>on</strong>nel: improve management of exist<strong>in</strong>g human and material resources, upgrade staffability to design, implement, and supervise preventive and primary health programs(particularly child survival activities);Health sector plann<strong>in</strong>g: <strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al capacity to plan, manage, and m<strong>on</strong>itor healthproblems and services; andPopulati<strong>on</strong> policy and resources: promote development of nati<strong>on</strong>al populati<strong>on</strong> policies and<strong>in</strong>crease access to family plann<strong>in</strong>g services.5.3 EXPERIENCESDespite c<strong>on</strong>siderable effort <strong>on</strong> the part of the MOPHSA and the technical assistance provided bythe grant, the program has been perceived by evaluators as too ambitious and too complex for the human,<strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al, and fiscal resources available. In additi<strong>on</strong>, achievements must be balanced aga<strong>in</strong>st the muchslower than anticipated pace at which grant implementati<strong>on</strong> has moved.N<strong>on</strong>e the less, the Government of Niger has undertaken a number of important health sectorreforms as a result of the grant. Most notably these have been <strong>in</strong> the area of health f<strong>in</strong>ance, developmentof <strong>in</strong>formati<strong>on</strong> systems for improved plann<strong>in</strong>g, and cost c<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ment for hospital services. It is importantto highlight the fact that the program appears to have had a positive impact up<strong>on</strong> the health policyenvir<strong>on</strong>ment despite several negative process outcomes identified by the evaluators.Factors which appear to have c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ed the grant <strong>in</strong> achiev<strong>in</strong>g its objectives with<strong>in</strong> the orig<strong>in</strong>altime frame have been documented <strong>in</strong> two mid-term evaluati<strong>on</strong>s. The factors identified by the evaluatorsmay be categorized as chiefly related to the design of the NHSSG itself and <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>al c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>tsassociated with implementati<strong>on</strong> of the program.13

The evaluators c<strong>on</strong>cluded that the nature, number, and structure of the policy reform benchmarksc<strong>on</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> the NHSSG resulted <strong>in</strong> a great many activities be<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>itiated by the MOPHSA <strong>in</strong> anuncoord<strong>in</strong>ated manner (the grant identified 60 benchmarks spread out over six policy areas requir<strong>in</strong>gcoord<strong>in</strong>ati<strong>on</strong> of at least four separate m<strong>in</strong>istries). While the total volume of work carried out was deemedimpressive, there was a result<strong>in</strong>g lack of focus by policymakers and an <strong>in</strong>complete understand<strong>in</strong>g of thenature of the reform agenda which the NHSSG def<strong>in</strong>ed. The reforms and the resources did not appearclosely l<strong>in</strong>ked <strong>in</strong> the m<strong>in</strong>ds of MOPHSA policymakers and therefore provided little <strong>in</strong>centive to undertakethe reform package. NHSSG resources were not allocated to the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s resp<strong>on</strong>sible for the reformsso that <strong>in</strong> the eyes of many (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the evaluators) the c<strong>on</strong>necti<strong>on</strong> between "carrot and stick" was notachieved.The delays experienced <strong>in</strong> meet<strong>in</strong>g reform agenda benchmarks has meant that the f<strong>in</strong>ancialresources have not been released to the MOPHSA accord<strong>in</strong>g to the orig<strong>in</strong>al time l<strong>in</strong>e. Less than $5 milli<strong>on</strong>of the $10.4 milli<strong>on</strong> allocated has been released after eight years (1986-1994). The orig<strong>in</strong>al time l<strong>in</strong>eanticipated the disbursement of the entire $10.4 milli<strong>on</strong> with<strong>in</strong> a five-year period (1991). As a result ofthese delays (and others brought about by the de-certificati<strong>on</strong> of the <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong> resp<strong>on</strong>sible for theallocati<strong>on</strong> and track<strong>in</strong>g of funds for the Government of Niger) the ec<strong>on</strong>omic impact of the grant has,clearly, been significantly reduced. It was noted by the evaluati<strong>on</strong> that complicated and unclear directivesfor the development of subgrants for the use of the NHSSG counterpart funds c<strong>on</strong>tributed to the lack ofec<strong>on</strong>omic impact of the grant.Instituti<strong>on</strong>al weaknesses identified dur<strong>in</strong>g the evaluati<strong>on</strong>s have plagued the NHSSG as well. TheMOPHSA has never allocated a sufficient number of qualified and capable pers<strong>on</strong>nel to assist <strong>in</strong>undertak<strong>in</strong>g grant activities. This is most likely a functi<strong>on</strong> of a lack of ownership for the reform agendaand an absolute lack of pers<strong>on</strong>nel capable of the analytic work required to achieve many of the NHSSGbenchmarks.The secretariat established by the M<strong>in</strong>istry of Plann<strong>in</strong>g to execute and track the disbursement ofNHSSG funds was deemed <strong>in</strong>adequate and decertified by <strong>USAID</strong>. Additi<strong>on</strong>ally, <strong>USAID</strong> found that it didnot have sufficient resources to adequately m<strong>on</strong>itor grant activities.L<strong>in</strong>kage of NHSSG reform c<strong>on</strong>diti<strong>on</strong>alities to those of the World Bank program proved to beproblematic. The MOPHSA was not able to undertake the activities required by the World Bank with<strong>in</strong>the orig<strong>in</strong>al time frame. As a result, several NHSSG activities were held hostage and were not able to becompleted, thus hold<strong>in</strong>g up the eventual disbursement of NHSSG fund<strong>in</strong>g.14

6.0 KENYA6.1 BACKGROUNDKenya’s early ec<strong>on</strong>omic expansi<strong>on</strong> period, 1963-1980, was am<strong>on</strong>g the greatest <strong>in</strong> Africa. RealGNP grew by over 6 percent annually and real GNP per capita grew at an annual rate of over 3 percent.The early 1980s were marked by substantial ec<strong>on</strong>omic decl<strong>in</strong>es with real per capita growth of m<strong>in</strong>us 0.2percent per year and a (current) deficit of over 12 percent of GDP. The latter half of the 1980s markeda recovery period, with Kenya’s ec<strong>on</strong>omy achiev<strong>in</strong>g a growth rate of about 5 percent per year. The overallperformance of the ec<strong>on</strong>omy has been relatively str<strong>on</strong>g s<strong>in</strong>ce the recovery <strong>in</strong> the mid-1980s: agricultural,manufactur<strong>in</strong>g, service, and tourism sectors have grown and performed well. However, the overall str<strong>on</strong>gec<strong>on</strong>omic performance has been accompanied by rapid populati<strong>on</strong> growth, ris<strong>in</strong>g aggregate demand, and<strong>in</strong>flati<strong>on</strong>ary pressures.In 1985 the Government of Kenya <strong>in</strong>itiated its Budget Rati<strong>on</strong>alizati<strong>on</strong> Program to c<strong>on</strong>trol andrestructure public expenditures. The thrust of the budget rati<strong>on</strong>alizati<strong>on</strong> called for c<strong>on</strong>trols <strong>on</strong> overallspend<strong>in</strong>g and policy reforms to change the compositi<strong>on</strong> of government spend<strong>in</strong>g (e.g., address<strong>in</strong>gimbalances between wage and n<strong>on</strong>-wage expenditures). However, progress <strong>in</strong> improv<strong>in</strong>g the compositi<strong>on</strong>of public expenditures was very slow and government employment c<strong>on</strong>t<strong>in</strong>ued to grow. In additi<strong>on</strong>, thesebudgetary c<strong>on</strong>stra<strong>in</strong>ts adversely affected and magnified the recurrent cost f<strong>in</strong>anc<strong>in</strong>g problem of the healthsector by limit<strong>in</strong>g resources available to the sector.Follow<strong>in</strong>g the sudden fall of coffee and tea prices and the result<strong>in</strong>g terms of trade deteriorati<strong>on</strong><strong>in</strong> 1987, together with expansi<strong>on</strong>ary fiscal and m<strong>on</strong>etary policies, serious macroec<strong>on</strong>omic imbalancesemerged. Widespread ec<strong>on</strong>omic stabilizati<strong>on</strong> became essential, and <strong>in</strong> early 1988 the Government of Kenyareceived IMF assistance <strong>in</strong> the form of an 18-m<strong>on</strong>th stand-by arrangement and a three-year StructuralAdjustment Facility to support stabilizati<strong>on</strong> efforts.Efforts to move Kenya toward a multiparty, truly democratic state have dom<strong>in</strong>ated the politicalenvir<strong>on</strong>ment s<strong>in</strong>ce the late 1980s. Parliamentary electi<strong>on</strong>s were held <strong>in</strong> 1988 and late 1992. Presidentialelecti<strong>on</strong>s were held <strong>in</strong> late 1992. Civil unrest, strikes, and dem<strong>on</strong>strati<strong>on</strong>s were associated with theseattempts at political transformati<strong>on</strong>. Violent ethnic disputes have occurred frequently dur<strong>in</strong>g the last threeyears, especially <strong>in</strong> Western Kenya.6.2 HEALTH SECTORThe Kenyan health sector can be divided <strong>in</strong>to three sub-sectors: public, voluntary, and private. Thepublic sub-sector comprises the government and municipal health services. It provides about 70 percentof hospital beds and employs the majority of doctors, cl<strong>in</strong>ical workers, and nurses. The voluntary subsectorc<strong>on</strong>sists of the church-related health services and the health activities of other n<strong>on</strong>-governmentorganizati<strong>on</strong>s and provides about 20 percent of hospital beds. The private sub-sector <strong>in</strong>cludes medicalservices provided directly by private companies to their employees and through the "market" by privatehealth <strong>in</strong>stituti<strong>on</strong>s, fee-for-service medical practiti<strong>on</strong>ers and pharmacies.15