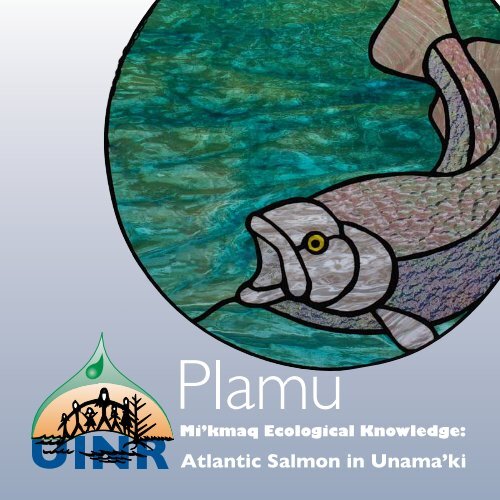

PlamuâMi'kmaq Ecological Knowledge: Atlantic Salmon in Unama'ki

PlamuâMi'kmaq Ecological Knowledge: Atlantic Salmon in Unama'ki

PlamuâMi'kmaq Ecological Knowledge: Atlantic Salmon in Unama'ki

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

PlamuMi’kmaq <strong>Ecological</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong>:<strong>Atlantic</strong> <strong>Salmon</strong> <strong>in</strong> Unama’kiby Shelley Denny, Angela Denny, Keith Christmas, Tyson Paul© Unama’ki Institute of Natural ResourcesAcknowledgementsWe would like to thank the follow<strong>in</strong>g people for their contributionto the content and review of this publication. Wela’lioq.We would liketo dedicate thisVictor AlexCorey BattisteJake BattistePeter BattisteAlan BernardBlair Bernard, Jr.W<strong>in</strong>ston BernardStephen ChristmasCharlie DennisDean DennyJames DoucetteJoe GoogooJudy Bernard-GoogooStephen IsaacDennis IsadoreLester JohnsonDr. Albert MarshallGeorge MarshallLillian B. MarshallPeter MarshallEdward D. MorrisAaron S. PaulCameron PaulClifford PaulDanny PaulLance PaulLeonard PaulStephen PaulRichard PierroKerry ProsperJohn SylliboyLawrence Wellspublication tobeloved familymembers andElders of Unama’kiwho have carriedon the traditionsand shared theirknowledge andpassion for2the resource.

ContentsAcknowledgements 2Introduction 3Mi’kmaq World View 4Bras d’Or Lakes 5<strong>Knowledge</strong> Gather<strong>in</strong>g 7<strong>Knowledge</strong> 7Plamu/<strong>Atlantic</strong> <strong>Salmon</strong><strong>in</strong> Unama’ki 8<strong>Salmon</strong> Harvest<strong>in</strong>g 8Habitats 11<strong>Salmon</strong> Movements andCues from Nature 12<strong>Salmon</strong> Produc<strong>in</strong>g Rivers 13Preparation and Uses 13Observations on <strong>Salmon</strong>and Their Behaviour 14Observations on <strong>Salmon</strong>Conditions 15The Value of <strong>Salmon</strong> and<strong>Salmon</strong> Harvest<strong>in</strong>g 15Netukulimk: Traditional<strong>Salmon</strong> Management 16Current State of the <strong>Salmon</strong>Population and Justification 18Mi’kmaq Concerns 19A Call for Action 21IntroductionAborig<strong>in</strong>al Traditional <strong>Knowledge</strong> (ATK) is a broad description of an<strong>in</strong>tegrated package of knowledge that <strong>in</strong>cludes the local knowledge of species,environmental practices and management systems, social <strong>in</strong>stitutions thatprovide the rules for management systems, and world views that form thebasis for our beliefs. ATK comes from watch<strong>in</strong>g and listen<strong>in</strong>g, through directexperience of song and ceremonies, through the activities of hunt<strong>in</strong>g anddaily life, from trees and animals, and <strong>in</strong> dreams and visions. <strong>Knowledge</strong>,values, and identity are passed down to the next generation through practice,ceremonies, legends, dance, or song. ATK, and more specifically Mi’kmaq<strong>Ecological</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> (MEK), the Mi’kmaq way of life, is derived from centuriesof <strong>in</strong>teraction, observation, and adaptation to the natural environment. It is theMi’kmaq science of survival <strong>in</strong>tertw<strong>in</strong>ed with spirituality and culture unique tothe people.The collection and preservation of ATK is becom<strong>in</strong>g more important. Initiallyused <strong>in</strong> land negotiations, ATK is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly recognized for use <strong>in</strong> scientificassessments, management plans, and recovery strategies for several speciesprotected through Canadian legislation, known as the Species at Risk Act.Because of the potential use for MEK for culturally important species suchas the American eel (katew) and <strong>Atlantic</strong> salmon (plamu), demand for specificecological knowledge held by the Mi’kmaq is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g. While there areprotocols <strong>in</strong> place for the collection of MEK, little documentation has beenproduced for shar<strong>in</strong>g this knowledge beyond the community’s use and culture.The Unama’ki Institute of Natural Resources (UINR) is an organizationthat represents the five Mi’kmaq communities of Unama’ki (Cape BretonIsland, Nova Scotia) on natural resources issues. UINR contributes to anunderstand<strong>in</strong>g and protection of the Bras d’Or Lakes’ ecosystem throughresearch, monitor<strong>in</strong>g, education, management, and by <strong>in</strong>tegrat<strong>in</strong>g Mi’kmaq andconventional ways of understand<strong>in</strong>g, known as Two-Eyed See<strong>in</strong>g. UINR wasidentified as the lead organization to collect, <strong>in</strong>terpret, and store MEK for thisregion.References 233

Mi’kmaq World ViewThe Mi’kmaq are part of Wabanaki, the Algonqu<strong>in</strong>speak<strong>in</strong>gconfederacy that <strong>in</strong>cludes four otherNations; Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot,and Abenaki. Mi’kma’ki (land of the Mi’kmaq)<strong>in</strong>cludes the five <strong>Atlantic</strong> prov<strong>in</strong>ces andnorthern Ma<strong>in</strong>e.Mi’kma’ki was held <strong>in</strong> communalownership. Land and its resourceswere not commodities that could bebought and sold but were consideredgifts from the Creator. This view is verydifferent from the Western view of land.As Mi’kmaq, we were the caretakers of theseven districts of Mi’kma’ki and we strivedto live <strong>in</strong> harmony. This belief rema<strong>in</strong>s strong <strong>in</strong>our culture today.We view the world and all that is <strong>in</strong> it as hav<strong>in</strong>gspirit. We consider all life equal to our own and treatit with respect. We developed an <strong>in</strong>timate understand<strong>in</strong>g ofthe relationships between the liv<strong>in</strong>g and non-liv<strong>in</strong>g so that each plant, animal,constellation, full moon, or red sky tells a story that guides our people so theycan survive. These beliefs affect the manner <strong>in</strong> which we treat the natural worldfor sustenance and survival. Animals and plants are not taken if they are notneeded. All spirits are acknowledged and respected as relatives and are offeredtobacco, prayer, or ceremony (or comb<strong>in</strong>ation) when taken. No part of ananimal is wasted. All parts that cannot be used are returned to the Creator. Theconsciousness is described by the Mi’kmaq word, Netukulimk.4The Mi’kmaq right to fish for food, social and ceremonial needs, and for amoderate livelihood, is recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada andprotected by the Constitution of Canada.

Bras d’Or LakesThe Bras d’Or Lakes, situated <strong>in</strong> the center of Cape BretonIsland, Nova Scotia, are a large estuar<strong>in</strong>e body of<strong>in</strong>terconnect<strong>in</strong>g bays, barachois ponds, channels,and islands. The Bras d’Or Lakes formedapproximately 10,000 years ago when theexist<strong>in</strong>g bas<strong>in</strong> that was carved out of softsandstone from the last glacial periodbecame flooded by adjacent ocean water.The term “Lakes” refers to two ma<strong>in</strong>components. The North Bas<strong>in</strong> and theBras d’Or Lake, connected by a 500 mwide open<strong>in</strong>g (Barra Strait), are knowncollectively as the Bras d’Or Lakes. Thesmaller component, the North Bas<strong>in</strong>,branches <strong>in</strong>to two channels that lead toseparate small open<strong>in</strong>gs to the <strong>Atlantic</strong> Ocean.The Great Bras d’Or Channel is 30 km long withan average depth of 19.5 m, average width of 1.3 kmand is the source of the majority of saltwater exchangebetween the Lakes and Sydney Bight (<strong>Atlantic</strong> Ocean).St. Andrew’s Channel connects to Sydney Bight through a muchmore restrictive open<strong>in</strong>g known as the Little Bras d’Or Channel. This channel,8 km <strong>in</strong> length, less than 100 m wide and approximately 5 m deep, does notcontribute significantly to temperature and sal<strong>in</strong>ity distributions. At theirsouthern-most po<strong>in</strong>t, the Bras d’Or Lakes connect to the <strong>Atlantic</strong> Ocean througha small, man-made canal that allows only an occasional exchange of water dur<strong>in</strong>gvessel movements.The Bras d’Or Lakes has been designated <strong>in</strong> the World Network of BiosphereReserves by the United Nations Man and the Biosphere Programme.5

The perimeter of the Bras d’Or Lakesmeasure approximately 1,000 kmand have a total area of 1,080 km 2 .Their average depth is 30 m but variesthroughout. St. Andrew’s Channel,for example, has a maximum depthof 280 m while small bays and coveshave average depths of 10 m or less.Tidal range dim<strong>in</strong>ishes rapidly fromthe Great Bras d’Or Channel <strong>in</strong>ward,with tidal ranges between 16 cm nearthe entrance to 4 cm at Iona. Currentsalso follow the same pattern but arestronger <strong>in</strong> the channels and chokepo<strong>in</strong>ts. Sal<strong>in</strong>ity and temperature variesby area. Sal<strong>in</strong>ity ranges from 30 ppt<strong>in</strong> the Great Bras d’Or Channel tosal<strong>in</strong>ities lower than 18 ppt <strong>in</strong> semienclosedbas<strong>in</strong>s, but averages tendto fall around 22 ppt <strong>in</strong> most of theopen regions. W<strong>in</strong>ter temperatures fallto just below 0 o C and the coves andponds freeze over. However, <strong>in</strong> the pastfew years, some of these areas did notfreeze. Summer temperatures exceed16 o C <strong>in</strong> July and surface and subsurfacetemperatures are even higher(>20 o C) <strong>in</strong> shallow coves, especially<strong>in</strong> River Denys Bas<strong>in</strong>. Substrata areprimarily silt with smaller proportionsof sand, gravel, and boulders.The environmental quality of theLakes is still considered to be verygood. Sewage is the primary sourceof pollution. Sediments from landare becom<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly difficultto control and have the potentialto alter important habitats. Organiccontam<strong>in</strong>ation and heavy metals <strong>in</strong>sediments, water, and biota are wellbelow the federal sediment andwater quality guidel<strong>in</strong>es. The Brasd’Or Lakes has been described ashav<strong>in</strong>g a relatively low level of naturalproductivity.The Bras d’Or Lakes are home to avariety of biota. Warm and cold waterfish and <strong>in</strong>vertebrates are present withseveral fish species, such as mackerel,herr<strong>in</strong>g, and salmon migrat<strong>in</strong>g to theLakes annually to spawn. The primarycommercial fisheries are for lobster,eel, and gaspereau. Invasive speciessuch as the green crab, the MSX oysterdisease parasite, eel swimbladderparasite, and the golden star tunicatehave found their way <strong>in</strong>to the Brasd’Or Lakes. With their rare physicaland chemical oceanography, range oftemperate, arctic biota occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>less than 10 km of water, and diversityof habitats, the Bras d’Or Lakes aretruly a unique ecosystem.The Bras d’Or Lakes are of greatsignificance to the Mi’kmaq heritage <strong>in</strong>this region. The Mi’kmaq word for theBras d’Or Lakes is Pitu’paq, mean<strong>in</strong>g“to which all th<strong>in</strong>gs flow.” The Brasd’Or Lakes have provided a foodsource for the Mi’kmaq. Numerousfish species, such as mackerel, trout,salmon, smelt, gaspereau, cod, hake,flounder, herr<strong>in</strong>g, eel, and othersprovide prote<strong>in</strong> to our diet, as doresident <strong>in</strong>vertebrates such as lobster,mussels, oysters, clam, scallops, whelks,and quahogs. Numerous bird species,such as geese and duck, have thrivedhere and were hunted. These gifts areimportant to communal health and are<strong>in</strong>tertw<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> our culture. The Lakesare also a means of transportationbetween hunt<strong>in</strong>g and fish<strong>in</strong>g areas andthose used for spiritual solidarity, likeMalikewe’j (Malagawatch) or Mniku(Chapel Island).6

<strong>Knowledge</strong> Gather<strong>in</strong>gMi’kmaq ecological knowledge gathered for this report was collected fromMi’kmaq harvesters through a series of <strong>in</strong>terviews and workshops.For knowledge collection and shar<strong>in</strong>g, UINR follows Mi’kmaq <strong>Ecological</strong><strong>Knowledge</strong> protocols established by the Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq Chiefs,Mi’kmaq Ethics Watch (Unama’ki College), Unama’ki Parks Canada sites (preparedfor Parks Canada by UINR 2007), and advice of Elders and fishers.In September 2011, the application for the collection of Mi’kmaq ecologicalknowledge on salmon was submitted to the Mi’kmaq Ethics Watch forconsideration for approval. Approval was obta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> December 2011.A workshop was held March 5, 2012 <strong>in</strong> Membertou, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.Selection of participants <strong>in</strong>cluded a balance of Elders, current harvesters,Aborig<strong>in</strong>al Fishery Guardians and knowledge holders. <strong>Knowledge</strong> holders werenot randomly selected. Selection of Elders was based on a referral method fromUINR’s Elder Advisor. Current harvesters were selected from a pool of <strong>in</strong>dividualswho were representative of active harvesters.Another workshop was held March 28 and March 31, 2012 to add to exist<strong>in</strong>gknowledge and to <strong>in</strong>terpret and review the knowledge gathered.<strong>Knowledge</strong>The views <strong>in</strong> this report do notrepresent those of the entire Mi’kmaqnation. Participation by UINR andthe Mi’kmaq <strong>in</strong> this workshop groupis not, and should not, be construedas consultation. Any new areas be<strong>in</strong>gproposed by the Crown(s) to haveexpanded legal protection wouldrequire separate consultation underthe Mi’kmaq-Nova Scotia-CanadaConsultation process.The knowledge conta<strong>in</strong>ed <strong>in</strong> thisreport is strongly connected toMi’kmaq tradition, the practice ofsalmon harvest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the Bras d’OrLakes, and the transfer of knowledgebetween generations through storiesand practice.7

<strong>Salmon</strong> Harvest<strong>in</strong>g<strong>Salmon</strong> are most frequently captured<strong>in</strong> rivers us<strong>in</strong>g rods (fly and lure), spear,div<strong>in</strong>g, snares, se<strong>in</strong>es or weirs. Weirsmade by us<strong>in</strong>g rocks were designed tolead salmon <strong>in</strong>to an area l<strong>in</strong>ed by alderbranches stand<strong>in</strong>g upright <strong>in</strong> the gravel.<strong>Salmon</strong>, if captured <strong>in</strong> the estuar<strong>in</strong>ewaters of the Bras d’Or Lakes, weretaken through gill net. Spear<strong>in</strong>g iscommon and typically occurs at nightand referred to as ‘saqsikwemk.’Plamu/<strong>Atlantic</strong> <strong>Salmon</strong> <strong>in</strong> Unama’ki<strong>Salmon</strong> harvest<strong>in</strong>g spans many generations and is a reflection of local and<strong>in</strong>timate understand<strong>in</strong>g of salmon ecology <strong>in</strong> our traditional territory of Unama’ki,known today as Cape Breton Island. The traditional practice of spear<strong>in</strong>g salmoncont<strong>in</strong>ues today and is ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>ed through harmony and respect for the spiritualrelationships between ourselves and plants, animals, and elements on Earth.Harvest<strong>in</strong>g occurs throughout theyear but is concentrated at the timeof, or just prior to, spawn<strong>in</strong>g runs.In the 1980s and earlier, salmon wasalso harvested <strong>in</strong> w<strong>in</strong>ter <strong>in</strong> the Brasd’Or Lakes. Long herr<strong>in</strong>g nets wereset under the ice to catch herr<strong>in</strong>g andsalmon.<strong>Salmon</strong> harvest<strong>in</strong>g took place <strong>in</strong> manyrivers and barachois <strong>in</strong> the Bras d’OrLakes watershed and around Unama’ki.Once widespread, salmon harvest<strong>in</strong>gis now concentrated <strong>in</strong> the MargareeRiver on the western side of the islandand North River <strong>in</strong> St. Ann’s Bay on theeastern side of Cape Breton.8Historically, at least 22 locations <strong>in</strong> theBras d’Or Lakes watershed and at least35 other locations on the perimeter ofthe Island were traditionally harvested.

Historical salmon produc<strong>in</strong>gareas <strong>in</strong>cluded:Aspy River (Middle, North and South)Auco<strong>in</strong> BrookBaddeck RiverBalls CreekBarachois RiverBarachois-McLeod BrookBelfry LakeBenacadie RiverBenacadie PondBig BrookBlack BrookBreac BrookCataloneCheticamp RiverCrooked LakeDenys Bas<strong>in</strong>East Bay BarachoisFifes (Aconi) BrookFramboise RiverFrench BrookFrenchvale BrookGabarusGabarus LakeGeorge’s RiverGillis BrookGillis LakeGrand RiverGrantmire BrookIndian Brook (Eskasoni)Indian Brook (St. Ann’s Bay)Ingonish RiverLeitches BrookLittle Bras d’Or ChannelLorra<strong>in</strong>e BrookMalagawatchMacDonald’s CoveMacIntosh BrookMargaree River (NE, SW)Marie Joseph BrookMcAdam’s LakeMcIver’s CoveMcK<strong>in</strong>non’s HarbourMiddle RiverMira RiverMirror CoveMorrison Lake BrookNorth RiverRed RiverRiver BennettRiver DenysRiver InhabitantsRiver Tillard<strong>Salmon</strong> River<strong>Salmon</strong> River (of Mira River)Skye RiverSouth Gut to St. Anns HarbourSydney RiverWarren Lake BrookThe majority of these areas are no longer harvested because of conservationconcerns for local salmon populations. Some areas, such as Sydney River, BaddeckBay, Balls Creek, and Frenchvale Brook, were not harvested because of concernsabout <strong>in</strong>dustrial pollution <strong>in</strong> the area.9

Habitats<strong>Salmon</strong> spend much of their lives <strong>in</strong> brooks and rivers. In all seasons, rivers areimportant salmon habitat. Ideal habitat is described as primarily consist<strong>in</strong>g of cool,clean water. This description encompasses conditions that are free of pollutionand siltation, and hav<strong>in</strong>g adequate shelter to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong> cool temperatures and<strong>in</strong>sect life for additional food. Natural debris is seen as natural shelter for salmonso that they can avoid predators. Adequate shelter was observed as hav<strong>in</strong>g aldersand natural hardwood, such as birch and maples, along the river banks. Areas <strong>in</strong>the river where the banks have overhang<strong>in</strong>g tree stumps and old logs are idealplaces for salmon. The bottom cannot be sandy. Rocky bottom with gravel andcobble were identified as ideal substrate.Parr are found <strong>in</strong> between the rocks of the river and are observed yearround. Occasionally they move about dur<strong>in</strong>g thesummer, likely seek<strong>in</strong>g cooler water. Parr arefeed<strong>in</strong>g and rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the brook until bigenough to move out of the brook.Smolt are found <strong>in</strong> rivers along the edge and <strong>in</strong> deeppools (1 m) before they travel downstream<strong>in</strong> the spr<strong>in</strong>g. Smolt will live alongside trout <strong>in</strong> the rivers.<strong>Salmon</strong> was also captured <strong>in</strong> the barachoisponds. These areas were identified as ahold<strong>in</strong>g area for the smolt as they wereleav<strong>in</strong>g the rivers, and adult salmon before mak<strong>in</strong>gtheir way up river.People contribute to habitat destruction and overharvest<strong>in</strong>g, and forget theimportance of salmon for all animals. Bears, seals and birds, such as eagles,mergansers and seagulls, also feed on salmon. Trout and <strong>in</strong>troduced species, suchas smallmouth bass and cha<strong>in</strong> pickerel, also feed on salmon fry.Illustrations by J. O. Pennanen© <strong>Atlantic</strong> <strong>Salmon</strong> Federation11

<strong>Salmon</strong> Movementsand Cues from NatureAdult salmon come <strong>in</strong>to the Brasd’Or Lakes’ rivers <strong>in</strong> early to midfallfor spawn<strong>in</strong>g, depend<strong>in</strong>g on thetemperature. <strong>Salmon</strong> come <strong>in</strong>to riversaround the perimeter of the Brasd’Or Lakes <strong>in</strong> the spr<strong>in</strong>g to fall. Otherfactors that affect salmon movementup river are current speed and depth.<strong>Salmon</strong> will wait until the water is deepand flow<strong>in</strong>g fast. <strong>Salmon</strong> come <strong>in</strong>to theriver as runs, with some runs smalleror larger than others. Each river had adifferent time for when the large runof salmon came <strong>in</strong>. Often, salmon willmove <strong>in</strong>to smaller rivers and brooks atnight but will move out to avoid predators dur<strong>in</strong>g the day. The emerg<strong>in</strong>g fireflysand completion of strawberry blossoms signal the tim<strong>in</strong>g of the spr<strong>in</strong>g run.<strong>Salmon</strong> spawn<strong>in</strong>g depends on ra<strong>in</strong>fall and temperature. <strong>Salmon</strong> beg<strong>in</strong> the processof spawn<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the fall after a heavy ra<strong>in</strong>. If the temperature is too warm, thefish will stay and will not travel further. Some observations that salmon areapproach<strong>in</strong>g to spawn is when two or three are seen together, as if they wereswimm<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> families. Often, when the salmon runs are occurr<strong>in</strong>g, you will hearbears and see more trout <strong>in</strong> the area.<strong>Salmon</strong> kelts (post-spawners) are commonly found <strong>in</strong> the rivers <strong>in</strong> the spr<strong>in</strong>g buthave also been found <strong>in</strong> late fall and w<strong>in</strong>ter. Kelts will rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> the river until thespr<strong>in</strong>g, leav<strong>in</strong>g after heavy ra<strong>in</strong>.Smolt leave rivers dur<strong>in</strong>g spr<strong>in</strong>g time after the ice is gone and stay <strong>in</strong> the estuar<strong>in</strong>eareas, especially if there is a barachois pond between the river and the Lakes.12

<strong>Salmon</strong> Produc<strong>in</strong>g Rivers<strong>Salmon</strong> are known to occur and spawn <strong>in</strong> the Margaree, Middle, Skye, Denys,Baddeck, Indian Brook, Aspy, and North Rivers, and 30 other smaller brooks <strong>in</strong>Unama’ki. Their productivity is likely related to limited human access to the riversbecause of private property laws and less habitat destruction, such as ford<strong>in</strong>g andclear-cutt<strong>in</strong>g.Preparationand Uses<strong>Salmon</strong> is an important foodsource for the Mi’kmaqpeople. Unfortunately,fewer salmon are availablefor general consumptionand are now reserved forspecial occasions, such asfeasts, powwows, and othercelebrations.Individual tastes guide preparation methods. Some modern methods ofpreparation <strong>in</strong>clude stuffed salmon, fillets, and steaks. Once scales are removed,salmon can be boiled, barbequed, smoked, or mar<strong>in</strong>ated. Roe is smoked or fried.Internal organs were offered to the river or forest as food for other animals, asbait for eels, or consumed (tastes like clams). Bones and tails are used as fertilizerand pet food. <strong>Salmon</strong> heads are stock piled and shared with local Asian cultures.In the fall, oil was collected from salmon dur<strong>in</strong>g the cook<strong>in</strong>g process and taken<strong>in</strong>ternally for medic<strong>in</strong>al purposes.Historically, salmon was smoked orbaked over an open fire l<strong>in</strong>ed withheated rocks. <strong>Salmon</strong> can be roasted bydigg<strong>in</strong>g a pit on the beach and mak<strong>in</strong>ga fire. C<strong>in</strong>ders are removed before thesalmon is placed <strong>in</strong> the pit, with rocksplaced on top and roasted. Vegetation(tall grasses) from the river side wasused to wrap the salmon before plac<strong>in</strong>git on the heated rocks.The whole salmon is used. The headand tail is boiled and eaten. <strong>Salmon</strong> isstuffed and served with a dipp<strong>in</strong>g saucecalled “plamuipkl”. Other methods ofpreparation <strong>in</strong>clude salt<strong>in</strong>g and dry<strong>in</strong>g,smok<strong>in</strong>g, pickl<strong>in</strong>g, and fry<strong>in</strong>g. Bones areused for garden fertilizer. All parts of asalmon are put to use with little to nowaste.There is no one method of preparationpreferred over another. The decid<strong>in</strong>gfactor is whom the fisher is shar<strong>in</strong>g itwith. For big events and celebrations,salmon is often stuffed to feed largecrowds and families.<strong>Salmon</strong> harvest<strong>in</strong>g traditionally occurs <strong>in</strong> the fall because they are <strong>in</strong> bettercondition as food. Roe provides a source of prote<strong>in</strong>. Roe can be baked <strong>in</strong> the ovento produce a sauce for the cooked salmon.13

• If conditions are not favourable,salmon will not spawn. Forexample, harvesters are catch<strong>in</strong>gsalmon that have not spawned <strong>in</strong>coastal rivers <strong>in</strong> December andJanuary.• Kelts leave the Skye River <strong>in</strong>December immediately afterspawn<strong>in</strong>g.• <strong>Salmon</strong> are not as large as theyused to be.• Smolts are not found <strong>in</strong> local freshwater lakes.Observations on <strong>Salmon</strong> and Their BehaviourGenerations of salmon harvest<strong>in</strong>g provided an opportunity for harvesters todevelop relationships with salmon <strong>in</strong> their natural habitat, allow<strong>in</strong>g them to takenote of <strong>in</strong>terest<strong>in</strong>g behaviors and observations.• <strong>Salmon</strong> are high jumpers and wave their tails to catch momentum and toremove sea lice. Jump<strong>in</strong>g loosens sea lice and the water splashes help toknock them off.• Lamprey marks are evident onsalmon <strong>in</strong> the Margaree River. Anunusual mark was seen on one fishthat could either be a puncturewound or bacterial <strong>in</strong>fection.• Ice cover is thought to affectsalmon f<strong>in</strong> rays. <strong>Salmon</strong> f<strong>in</strong>s appeardamaged.• <strong>Salmon</strong> have a good sense of smelland are aware of changes <strong>in</strong> nature.• They are very strong fish and can endure rough waters.• <strong>Salmon</strong> move faster before storms and will hide under leaves, rocks, etc.• They rema<strong>in</strong> still and can camouflage themselves with the bottom.14

Observations on<strong>Salmon</strong> ConditionsMost <strong>in</strong>dividuals observed sores <strong>in</strong> adult salmons and worms <strong>in</strong>side the muscle <strong>in</strong>salmon from the Margaree River. Lice was observed on the gills of smolt. Parasiteswere observed <strong>in</strong> salmon from Grand River, Indian Brook and Balls Creek/FrenchVale Brook. River Inhabitants is also an area where lamprey is found. Sea lice arecommon <strong>in</strong> salmon <strong>in</strong> the summer around Whycocomagh Bay but are also evident<strong>in</strong> the fall months, especially <strong>in</strong> the Margaree River. Scrapes and bite marks havebeen noticed on some salmon <strong>in</strong> this area.Sea lice are often found <strong>in</strong> warmer waters <strong>in</strong> August and September. Other areaswhere sea lice were observed on salmon <strong>in</strong>clude Grand River, Barachois River,Balls Creek, and Sydney River. Sea lice are more common <strong>in</strong> areas closer to theocean.<strong>Salmon</strong> from rivers <strong>in</strong>side the Bras d’Or Lakes’ watershed also had sea lice andlamprey marks. In 2004, <strong>in</strong> the area around Wagmatcook, lamprey bite marks wereobserved on the belly area of salmon.The Value of <strong>Salmon</strong>and <strong>Salmon</strong> Harvest<strong>in</strong>gThere are important dietaryconsiderations for harvest<strong>in</strong>g salmon.Many people enjoy the flavour andhealth benefits of wild salmon. Farmedsalmon are thought to have too manychemicals from the feed and antibioticsand is not a substitute for the healthbenefits wild salmon provide. <strong>Salmon</strong> isone of the staple foods at communitycelebrations and powwows because oftheir size. It is a large fish that can feedmany people. Shar<strong>in</strong>g is very importantto the Mi’kmaq and harvesters willoften share their catch, especiallywith those who cannot harvest forthemselves.<strong>Salmon</strong> consumption is l<strong>in</strong>ked tolongevity. The Mi’kmaq people livedlong lives on their traditional foods. Asour traditional diet is replaced withprocessed foods, our people are proneto illness, disease, and untimely death.Many cannot afford to purchase salmon<strong>in</strong> the grocery store nor is there adesire to do so. If they cannot have itwild then many will not have it at all.15

The experience of salmon harvest<strong>in</strong>gis also important to the Mi’kmaq. Itis part of the culture and many grewup harvest<strong>in</strong>g salmon and other fishspecies. It is part of the social norm tospend time with family learn<strong>in</strong>g aboutharvest<strong>in</strong>g practices and netukulimk(susta<strong>in</strong>ability). Many enjoy time spentoutdoors even if salmon is not caught.In some cases, salmon harvest<strong>in</strong>g canbe very relax<strong>in</strong>g.<strong>Salmon</strong> harvest<strong>in</strong>g was a means ofsustenance. Harvest<strong>in</strong>g was donefor survival. There were times whensalmon would be left alone andanother species would be harvested.People were very alert to times whensalmon would migrate up river.In the 1970s and 1980s, Mi’kmaq hadto purchase licenses which many couldnot afford. Today salmon harvest<strong>in</strong>gis still limited and restricted becauseof conservation concerns. When asalmon is caught, Elders are taken careof first.Netukulimk: Traditional <strong>Salmon</strong> ManagementSeveral concepts of traditional management or netukulimk are employed bythe Mi’kmaq of Unama’ki when harvest<strong>in</strong>g salmon. These concepts vary among<strong>in</strong>dividuals based on their beliefs or teach<strong>in</strong>gs as to what contributes to salmonconservation. This means harvest<strong>in</strong>g efforts are balanced <strong>in</strong> terms of stage ofsalmon or time harvested. For example, some harvesters let large salmon spawnbecause they have more eggs and experience, while others feel this may be thesalmon’s last spawn and it will die soon after. Many will not harvest kelts becauseof the meat’s condition, while others prefer kelts because they have successfullyspawned, contribut<strong>in</strong>g to the future salmon population.Another example of traditional management is the size of salmon captured. This isa reflection of the adoption of imposed size restrictions and care for broodstock.Many harvesters will carefully return salmon under 63 cm (24.5 <strong>in</strong>ches) backto the river. Many prefer the feed of larger, >63 cm (>24.5 <strong>in</strong>ches), salmon butwill let the really large salmon, >74 cm (>29 <strong>in</strong>ches), cont<strong>in</strong>ue its journey upriver to spawn. Others will take these salmon because they have likely spawnedsuccessfully before and are closer to the end of their life span than smaller,spawn<strong>in</strong>g salmon. Some harvest <strong>in</strong> the fall, while others harvest <strong>in</strong> spr<strong>in</strong>g andsummer.As with other species, salmon are harvested at certa<strong>in</strong> times of the year. Shar<strong>in</strong>gsalmon among multiple families is the backbone of Mi’kmaq culture. <strong>Salmon</strong> areharvested when needed or if the season allows their harvest. Several communitiesare limited <strong>in</strong> the number of salmon tags issued. Other communities are notlimited by regulations but rather limit themselves by practic<strong>in</strong>g netukulimk. Some<strong>in</strong>dividuals have resorted to purchas<strong>in</strong>g licenses to ga<strong>in</strong> access to more salmonand to avoid conflict with fishers of other cultures.Handl<strong>in</strong>g salmon affects their ability to survive. Smolt and parr are carefullyreleased if captured by rod. Smolt and parr are not targeted by spear, div<strong>in</strong>g, orsnares.16

<strong>Salmon</strong> are more commonly harvested<strong>in</strong> the fall when they travel upstream.Because they are <strong>in</strong> spawn<strong>in</strong>g condition,conservation is practiced. Harvesterstake only what they need. <strong>Salmon</strong> willnot take bait if they are not hungry,therefore spear<strong>in</strong>g or snar<strong>in</strong>g will takeplace.Large salmon produce larger quantitiesof eggs. They are the breed<strong>in</strong>g stockfor the population and because of this,many choose not target them or willcarefully release one if captured. If largefemales that are ready to spawn arecaptured, their eggs may be fertilizedwith the milt of a male and placed <strong>in</strong>tothe gravel of the pool (redds). Theseare set up along the river as <strong>in</strong>cubationponds. Even if the eggs do not becomefertilized, the eggs will become food forother animals.17

Current State of the <strong>Salmon</strong> Populationand JustificationThe salmon population is considered low and has been for many years.Improvements are seen <strong>in</strong> several rivers as the number of salmon and runs have<strong>in</strong>creased, but they are still so low there is general concern for their susta<strong>in</strong>ability.These areas are Skye River (We’koqma’q), Grand River, Indian Brook (Eskasoni),Indian Brook (St. Ann’s Bay), MacIntosh Brook, Gillis Brook, River Denys, andBenacadie Pond. The Margaree and North Rivers are still good rivers, while theMiddle and Baddeck Rivers are show<strong>in</strong>g signs of improvement.Because of the predictable tim<strong>in</strong>g of salmon runs, the time it takes to capturesalmon is a good <strong>in</strong>dication of change <strong>in</strong> abundance over the years. Fifteen yearsago it took two to three hours to catch approximately 22 salmon <strong>in</strong> the fallmonths. Now, it takes five hours to get four salmon. In the spr<strong>in</strong>g, it could takeapproximately eight hours to get four salmon. To fish salmon <strong>in</strong> North River now,it may take all day to get one salmon. However, <strong>in</strong> the Margaree River, a salmonwill bite right away if the right bait is used at the right time of day and year. An<strong>in</strong>crease <strong>in</strong> salmon has been observed <strong>in</strong> this river over the past few years.Overall, it takes longer to catch salmon. They are not as plentiful as they were40-60 years ago, or even 10 to 15 years ago. The population has decl<strong>in</strong>ed and thisdecl<strong>in</strong>e is consistent across all rivers.18

Mi’kmaq Concerns<strong>Salmon</strong> habitats are deteriorat<strong>in</strong>g. Many impacts and activities were identified ascaus<strong>in</strong>g harm to their habitats. These <strong>in</strong>clude overharvest<strong>in</strong>g of trees along riverbanks, acid ra<strong>in</strong>, garbage, pesticides, sewage, and siltation from gravel pits anderod<strong>in</strong>g banks and ford<strong>in</strong>g. Naturally and non-naturally occurr<strong>in</strong>g landslides, andoil and gas developments <strong>in</strong> fresh water systems that feed the rivers affect waterand sediment quality.Sedimentation and siltation <strong>in</strong> Margaree River is gett<strong>in</strong>g worse. There are changesoccurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> the river from clear cutt<strong>in</strong>g, farm<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>in</strong>creased ra<strong>in</strong>fall events.Increased sedimentation also means that harvesters cannot see and target salmon.Fish ladders, while promot<strong>in</strong>g up-river migration, can contribute to overharvest<strong>in</strong>g.Dur<strong>in</strong>g their spawn<strong>in</strong>g migration, salmon are vulnerable to predators, especiallyhumans.Smolt are a vulnerable part of the food cha<strong>in</strong> and must compete with other fishspecies for food and space. They are part of the food cha<strong>in</strong> for other animals.What affects it has impact on other species. <strong>Salmon</strong>, <strong>in</strong> all its stages, is a sharedresource among humans and animals. Also noted is a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> rivers’ speciessuch as smelt and gaspereau.Commercial development has affected traditional spawn<strong>in</strong>g rivers. Farms affectwater quality by <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g organic waste, <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g sediments that cover gravel<strong>in</strong> pools, and <strong>in</strong>creased water temperature from lack of shade from trees alongthe banks.Smolts mistakenly identified as trout are taken by younger harvesters.19

A Call for ActionHabitat preservation, improved management, and education were identified asapproaches to salmon conservation and susta<strong>in</strong>ability.Habitat for all stages of salmon are necessary. We must preserve habitats so theycan be productive for spawn<strong>in</strong>g salmon as well as juveniles. We need to addressthe causes of habitat destruction rather than just identify<strong>in</strong>g symptoms. To ourbest abilities, we must prevent pollution and siltation and keep our rivers cool.Improved management is needed on many levels. Illegal harvest of salmon isunacceptable and more must be done to prevent it. No amount of money fromf<strong>in</strong>es can replace the value of a salmon to the Mi’kmaq culture. Current bag limitsare too high for the recreational salmon fishery. Non-natives have more accessto salmon than the Mi’kmaq communities. Private lands should be appraised and<strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> river habitat assessments to identify areas that should be improved.To prevent pollution, oil, gas, and m<strong>in</strong>e development should not be allowed atheadwaters. We need to consider other forms of management actions and ideas.We could alternate pools when harvest<strong>in</strong>g to allow salmon to spawn. We shouldrespect spawn<strong>in</strong>g season and the time needed for prepar<strong>in</strong>g redds, mate selection,and spawn<strong>in</strong>g.Rivers and streams must be enhanced.Rules must be set. Buffer zonesare needed to protect banks onprivate property and <strong>in</strong> First Nationscommunities. As spawn<strong>in</strong>g occurs <strong>in</strong>pools, they should be treated withrespect and protected.Youth must be educated and <strong>in</strong>volved.It would be beneficial to see a “FishFriends” program set up <strong>in</strong> the schoolsto re<strong>in</strong>troduce salmon to ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong>populations. Education on all speciesand the <strong>in</strong>terconnectedness of ourenvironment should be part of thecurriculum <strong>in</strong> our schools.Education is needed across cultures. Mi’kmaq harvesters are often verbally andphysically attacked dur<strong>in</strong>g the salmon harvest. A greater presence of RCMPand Conservation and Enforcement Officers is needed. Conservation andEnforcement Officers and other salmon conservation groups should be educated<strong>in</strong> Mi’kmaq Rights and Title, Mi’kmaq worldview, and history so they can educateother cultures. Education is needed among younger harvesters <strong>in</strong> the Mi’kmaqcommunity on species identification for trout and salmon. There is an imbalance<strong>in</strong> the understand<strong>in</strong>g of rights and responsibilities among the younger generationthat could be taught through mentor<strong>in</strong>g programs. Open houses are neededto educate youth, Chief and Councils, and non-Mi’kmaq populations on theseriousness of the status of the salmon population <strong>in</strong> Canada and to show howpreservation and improvements to salmon habitat relate to current communityland practices.21

ReferencesAssembly of Nova Scotia Chiefs. 2007. Mi’kmaq <strong>Ecological</strong> <strong>Knowledge</strong> StudyProtocol. 1st Ed. Kwilmu’kw Maw-klusuaqn Mi’kmaq Rights Initiative. 22 pp.Berkes, F. Sacred Ecology: traditional ecological knowledge and resourcemanagement. Philedelphia: Taylor & Francis. 209 pp.Berneshawi, S. 1997. Resource management and the Mi’kmaq Nation.The Can. J. Native Studies. Vol. 17(1): 115-148.Denny, S. 2009. Aborig<strong>in</strong>al Traditional <strong>Knowledge</strong>: Mov<strong>in</strong>g ForwardWorkshop Report. Unam’ki Institute of Natural Resources.Available: [On-l<strong>in</strong>e] www.u<strong>in</strong>r.ca/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/ATK-2009-WEB.pdf. 17 pp.Gurbutt, P.A., B. Petrie and F. Jordon. 1993. The physical oceanography ofthe Bras d’Or Lakes: Data analysis and model<strong>in</strong>g. Canadian TechnicalReport of Hydrography and Ocean Studies: 147.Holmes Whitehead, R. and H. McGee. 2005. The Mi’kmaq: How their ancestorslived five hundred years ago. Halifax: Nimbus Publish<strong>in</strong>g Limited. 60 pp.Krueger, W.H. and K. Oliveira. 1997. Sex. Size, and gonad morphology ofsilver American eels Anquilla rostrata. Copeia. 2: 415-420.Lambert, T.C. 2002. Overview of the ecology of the Bras d’Or Lakes withemphasis on the fish. Proc. N.S. Inst. Sci. 42:65-100.Mi’kmaq Ethics Watch. Research Pr<strong>in</strong>ciples and Protocols. Cape Breton University.Available: [On-l<strong>in</strong>e]: www.cbu.ca/mrc/ethics-watch.Petrie, B. and J. Raymond. 2002. The oceanography of the Bras d’Or Lakes:General Introduction. Proc. N.S. Inst. Sci. 42:1-8.Petrie, B. and G. Bugden. 2002. The physical oceanography of the Bras d’Or Lakes.Proc. N.S. Inst. Sci. 42:9-36.Stra<strong>in</strong>, P. and P.A.Yeats. 2002. The chemical oceanography of the Bras d’Or Lakes.Proc. N.S. Inst. Sci. 42:37-64.Tremblay, M.J. 2002. Large epibenthic <strong>in</strong>vertebrates <strong>in</strong> the Bras d’Or Lakes.Proc. N.S. Inst. Sci. 42:101-126.23

UINR–Unama’ki Instituteof Natural Resourcesis Cape Breton’s Mi’kmaqvoice on natural resourcesand the environment.UINR represents the five Mi’kmaqcommunities of Unama’ki <strong>in</strong>forestry, mar<strong>in</strong>e science research,species management, traditional Mi’kmaqknowledge, water quality monitor<strong>in</strong>g,and environmental partnerships.Mail<strong>in</strong>g AddressPO Box 8096Eskasoni NS B1W 1C2Street Address4102 Shore RoadEskasoni NS B1W 1C2Phone902 379 2163Toll Free1 888 379 UINR (8467)Fax902 379 2250E-mail<strong>in</strong>fo@u<strong>in</strong>r.caWebu<strong>in</strong>r.ca