Oral medicine â Update for the dental practitioner - Oral Cancer ...

Oral medicine â Update for the dental practitioner - Oral Cancer ...

Oral medicine â Update for the dental practitioner - Oral Cancer ...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

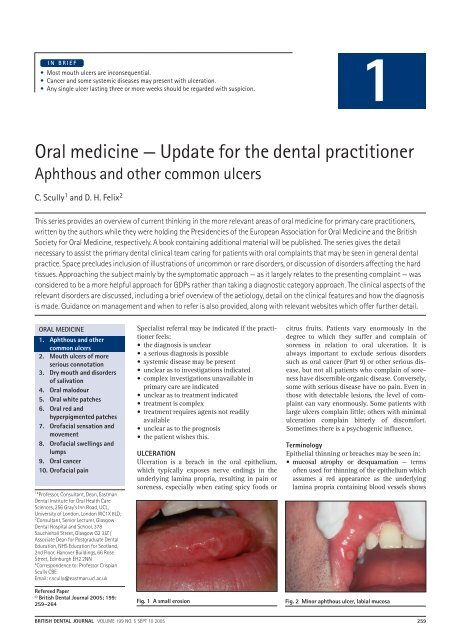

IN BRIEF• Most mouth ulcers are inconsequential.• <strong>Cancer</strong> and some systemic diseases may present with ulceration.• Any single ulcer lasting three or more weeks should be regarded with suspicion.1<strong>Oral</strong> <strong>medicine</strong> — <strong>Update</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>dental</strong> <strong>practitioner</strong>Aphthous and o<strong>the</strong>r common ulcersC. Scully 1 and D. H. Felix 2This series provides an overview of current thinking in <strong>the</strong> more relevant areas of oral <strong>medicine</strong> <strong>for</strong> primary care <strong>practitioner</strong>s,written by <strong>the</strong> authors while <strong>the</strong>y were holding <strong>the</strong> Presidencies of <strong>the</strong> European Association <strong>for</strong> <strong>Oral</strong> Medicine and <strong>the</strong> BritishSociety <strong>for</strong> <strong>Oral</strong> Medicine, respectively. A book containing additional material will be published. The series gives <strong>the</strong> detailnecessary to assist <strong>the</strong> primary <strong>dental</strong> clinical team caring <strong>for</strong> patients with oral complaints that may be seen in general <strong>dental</strong>practice. Space precludes inclusion of illustrations of uncommon or rare disorders, or discussion of disorders affecting <strong>the</strong> hardtissues. Approaching <strong>the</strong> subject mainly by <strong>the</strong> symptomatic approach — as it largely relates to <strong>the</strong> presenting complaint — wasconsidered to be a more helpful approach <strong>for</strong> GDPs ra<strong>the</strong>r than taking a diagnostic category approach. The clinical aspects of <strong>the</strong>relevant disorders are discussed, including a brief overview of <strong>the</strong> aetiology, detail on <strong>the</strong> clinical features and how <strong>the</strong> diagnosisis made. Guidance on management and when to refer is also provided, along with relevant websites which offer fur<strong>the</strong>r detail.ORAL MEDICINE1. Aphthous and o<strong>the</strong>rcommon ulcers2. Mouth ulcers of moreserious connotation3. Dry mouth and disordersof salivation4. <strong>Oral</strong> malodour5. <strong>Oral</strong> white patches6. <strong>Oral</strong> red andhyperpigmented patches7. Orofacial sensation andmovement8. Orofacial swellings andlumps9. <strong>Oral</strong> cancer10. Orofacial pain1 *Professor, Consultant, Dean, EastmanDental Institute <strong>for</strong> <strong>Oral</strong> Health CareSciences, 256 Gray’s Inn Road, UCL,University of London, London WC1X 8LD;2 Consultant, Senior Lecturer, GlasgowDental Hospital and School, 378Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3JZ /Associate Dean <strong>for</strong> Postgraduate DentalEducation, NHS Education <strong>for</strong> Scotland,2nd Floor, Hanover Buildings, 66 RoseStreet, Edinburgh EH2 2NN*Correspondence to: Professor CrispianScully CBEEmail: c.scully@eastman.ucl.ac.ukRefereed Paper© British Dental Journal 2005; 199:259–264Specialist referral may be indicated if <strong>the</strong> <strong>practitioner</strong>feels:• <strong>the</strong> diagnosis is unclear• a serious diagnosis is possible• systemic disease may be present• unclear as to investigations indicated• complex investigations unavailable inprimary care are indicated• unclear as to treatment indicated• treatment is complex• treatment requires agents not readilyavailable• unclear as to <strong>the</strong> prognosis• <strong>the</strong> patient wishes this.ULCERATIONUlceration is a breach in <strong>the</strong> oral epi<strong>the</strong>lium,which typically exposes nerve endings in <strong>the</strong>underlying lamina propria, resulting in pain orsoreness, especially when eating spicy foods orFig. 1 A small erosioncitrus fruits. Patients vary enormously in <strong>the</strong>degree to which <strong>the</strong>y suffer and complain ofsoreness in relation to oral ulceration. It isalways important to exclude serious disorderssuch as oral cancer (Part 9) or o<strong>the</strong>r serious disease,but not all patients who complain of sorenesshave discernible organic disease. Conversely,some with serious disease have no pain. Even inthose with detectable lesions, <strong>the</strong> level of complaintcan vary enormously. Some patients withlarge ulcers complain little; o<strong>the</strong>rs with minimalulceration complain bitterly of discom<strong>for</strong>t.Sometimes <strong>the</strong>re is a psychogenic influence.TerminologyEpi<strong>the</strong>lial thinning or breaches may be seen in:• mucosal atrophy or desquamation — termsoften used <strong>for</strong> thinning of <strong>the</strong> epi<strong>the</strong>lium whichassumes a red appearance as <strong>the</strong> underlyinglamina propria containing blood vessels showsFig. 2 Minor aphthous ulcer, labial mucosaBRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005 259

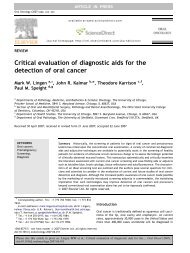

PRACTICEFig. 3 Chemical burn, rightmaxillary tuberosityFig. 4 Thermal burn, palatethrough. Most commonly this is seen in desquamativegingivitis (usually related to lichenplanus, or less commonly to pemphigoid) and ingeographic tongue (ery<strong>the</strong>ma migrans, benignmigratory glossitis). A similar process may alsobe seen in systemic disorders such as deficiencystates (of iron, folic acid or B vitamins).• mucosal inflammation (mucositis, stomatitis)which can cause soreness. Viral stomatitis,candidosis, radiation mucositis, chemo<strong>the</strong>rapyrelatedmucositis and graft-versus-host-diseaseare examples.• erosion which is <strong>the</strong> term used <strong>for</strong> superficialbreaches of <strong>the</strong> epi<strong>the</strong>lium. These often have ared appearance initially as <strong>the</strong>re is little damageto <strong>the</strong> underlying lamina propria, but <strong>the</strong>ytypically become covered by a fibrinous exudatewhich has a yellowish appearance (Fig.1). Erosions are common in vesiculobullousdisorders such as pemphigoid.• ulcer which is <strong>the</strong> term usually used where<strong>the</strong>re is damage both to epi<strong>the</strong>lium and laminapropria. An inflammatory halo, if present, alsohighlights <strong>the</strong> ulcer with a red halo around <strong>the</strong>yellow or grey ulcer (Fig. 2). Most ulcers aredue to local causes such as trauma or burns,but recurrent aphthous stomatitis and cancermust always be considered.Table 1 Main causes of oral ulcerationLocal causesAphthaeInfectionsDrugsMalignant diseaseSystemic diseasesTable 2 Main causes of mouth ulcersLocal causesTraumaAppliancesIatrogenicNon-acci<strong>dental</strong> injurySelf-inflictedSharp teeth or restorationsBurnsChemicalColdElectricHeatRadiationRecurrent aphthaeInfectionsAcute necrotising gingivitisChickenpoxDeep mycosesHand, foot and mouth diseaseHerpanginaHerpetic stomatitisHIVInfectious mononucleosisSyphilisTuberculosisDrugsCytotoxic drugs,Nicorandil, NSAIDsMany o<strong>the</strong>rsMalignant neoplasms<strong>Oral</strong>Encroaching from antrumSystemic diseaseMucocutaneous diseaseBehcet's syndromeChronic ulcerative stomatitisEpidermolysis bullosaEry<strong>the</strong>ma multi<strong>for</strong>meLichen planusPemphigus vulgarisSub-epi<strong>the</strong>lial immune blistering diseases(Pemphigoid and variants, dermatitisherpeti<strong>for</strong>mis, linear IgA disease)Haematological disordersAnaemiaGammopathiesHaematinic deficienciesLeukaemia and myelodysplastic syndromeNeutropenia and o<strong>the</strong>r white cell dyscrasiasGastrointestinal diseaseCoeliac diseaseCrohn's diseaseUlcerative colitisMiscellaneous uncommon diseasesEosinophilic ulcerGiant cell arteritisHypereosinophilic syndromeLupus ery<strong>the</strong>matosusNecrotising sialometaplasiaPeriarteritis nodosaReiters syndromeSweet's syndromeWegener's granulomatosis260 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005

PRACTICECauses of oral ulcerationUlcers and erosions can also be <strong>the</strong> final commonmanifestation of a spectrum of conditions. Theserange from: epi<strong>the</strong>lial damage resulting fromtrauma; an immunological attack as in lichenplanus, pemphigoid or pemphigus; damagebecause of an immune defect as in HIV diseaseand leukaemia; infections such as herpesviruses,tuberculosis and syphilis; cancer and nutritionaldefects such as vitamin deficiencies and somegastrointestinal diseases (Tables 1 and 2).Fig. 6 Minor aphthous ulcerationUlcers of local causesAt any age, <strong>the</strong>re may be burns from chemicalsof various kinds (Fig. 3), heat (Fig. 4), cold, orionising radiation or factitious ulceration, especiallyof <strong>the</strong> maxillary gingivae or palate.Children may develop ulceration of <strong>the</strong> lowerlip by acci<strong>dental</strong> biting following <strong>dental</strong> localanaes<strong>the</strong>sia. Ulceration of <strong>the</strong> upper labialfraenum, especially in a child with bruised andswollen lips, subluxed teeth or fractured jaw canrepresent non-acci<strong>dental</strong> injury. At any age, trauma,hard foods, or appliances may also causeulceration. The lingual fraenum may be traumatisedby repeated rubbing over <strong>the</strong> lower incisorteeth in cunnilingus, in recurrent coughing as inwhooping cough, or in self-mutilating conditions.Most ulcers of local cause have an obviousaetiology, are acute, usually single ulcers, lastless than three weeks and heal spontaneously.Chronic trauma may produce an ulcer with akeratotic margin (Fig. 5).Fig. 5 Traumatic ulceration, lateral tongueRecurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS; aphthae;canker sores)RAS is a very common condition which typicallystarts in childhood or adolescence and presentswith multiple recurrent small, round or ovoidulcers with circumscribed margins, ery<strong>the</strong>matoushaloes, and yellow or grey floors (Fig. 6).RAS affects at least 20% of <strong>the</strong> population,with <strong>the</strong> highest prevalence in higher socio-economicclasses. Virtually all dentists will seepatients with aphthae.AetiopathogenesisImmune mechanisms appear at play in a personwith a genetic predisposition to oral ulceration. Agenetic predisposition is present, and <strong>the</strong>re is apositive family history in about one third ofpatients with RAS. Immunological factors are alsoinvolved, with T helper cells predominating in <strong>the</strong>RAS lesions early on, along with some naturalkiller (NK) cells. Cytotoxic cells <strong>the</strong>n appear in <strong>the</strong>lesions and <strong>the</strong>re is evidence <strong>for</strong> an antibodydependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) reaction. Itnow seems likely <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e that a minor degree ofimmunological dysregulation underlies aphthae.RAS may be a group of disorders of differentpathogeneses. Cross-reacting antigens between<strong>the</strong> oral mucosa and microorganisms may be <strong>the</strong>initiators, but attempts to implicate a variety ofbacteria or viruses have failed.Predisposing factorsMost people who suffer RAS are o<strong>the</strong>rwiseapparently completely well. In a few, predisposingfactors may be identifiable, or suspected.These include:1. Stress: underlies RAS in many cases. RAS aretypically worse at examination times.2. Trauma: biting <strong>the</strong> mucosa, and <strong>dental</strong>appliances may lead to some aphthae.3. Haematinic deficiency (deficiencies of iron,folic acid (folate) or vitamin B 12) in up to 20%of patients.4. Sodium lauryl sulphate (SLS), a detergent insome oral healthcare products may produceoral ulceration.5. Cessation of smoking: may precipitate oraggravate RAS.6. Gastrointestinal disorders particularly coeliacdisease (gluten-sensitive enteropathy) andCrohn’s disease in about 3% of patients.7. Endocrine factors in some women whose RASare clearly related to <strong>the</strong> fall in progestogenlevel in <strong>the</strong> luteal phase of <strong>the</strong>ir menstrual cycle.8. Immune deficiency: ulcers similar to RAS maybe seen in HIV and o<strong>the</strong>r immune defects.9. Food allergies: underlie RAS rarely.Drugs may produce aphthous-like lesions (seebelow).Key points <strong>for</strong> dentists: aphthous ulcers• They are so common that all dentists willsee <strong>the</strong>m• It is important to rule out predisposingcauses (sodium lauryl sulphate, certainfoods/drinks, stopping smoking or vitaminor o<strong>the</strong>r deficiencies) or conditions such asBehcet’s syndrome• Enquire about eye, genital, gastrointestinalor skin lesions• Topical corticosteroids are <strong>the</strong> maintreatmentBRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005 261

PRACTICEClinical featuresThere are three main clinical types of RAS,though <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>the</strong>se distinctions isunclear and it is conceivable that <strong>the</strong>y may representthree different diseases:1. Minor aphthous ulcers (MiAU; Mikulicz Ulcer)occur mainly in <strong>the</strong> 10 to 40-year-old agegroup, often cause minimal symptoms, and aresmall round or ovoid ulcers 2-4 mm indiameter. The ulcer floor is initially yellowishbut assumes a greyish hue as healing andepi<strong>the</strong>lialisation proceeds. They are surroundedby an ery<strong>the</strong>matous halo and some oedema,and are found mainly on <strong>the</strong> non-keratinisedmobile mucosa of <strong>the</strong> lips, cheeks, floor of <strong>the</strong>mouth, sulci or ventrum of <strong>the</strong> tongue. Theyare only uncommonly seen on <strong>the</strong> keratinisedmucosa of <strong>the</strong> palate or dorsum of <strong>the</strong> tongueand occur in groups of only a few ulcers (oneto six) at a time. They heal in seven to 10 days,and recur at intervals of one to four monthsleaving little or no evidence of scarring (Fig. 7).are found on any area of <strong>the</strong> oral mucosa,including <strong>the</strong> keratinised dorsum of <strong>the</strong>tongue or palate, occur in groups of only a fewulcers (one to six) at one time and heal slowlyover 10 to 40 days. They recur extremely frequentlymay heal with scarring and are occasionallyfound with a raised erythrocyte sedimentationrate or plasma viscosity.3. Herpeti<strong>for</strong>m Ulceration (HU) is found in aslightly older age group than <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>r <strong>for</strong>msof RAS and are found mainly in females. Theybegin with vesiculation which passes rapidlyinto multiple minute pinhead-sized discreteulcers (Fig. 10), which involve any oral siteincluding <strong>the</strong> keratinised mucosa. Theyincrease in size and coalesce to leave largeround ragged ulcers, which heal in 10 days orlonger, are often extremely painful and recurso frequently that ulceration may be virtuallycontinuous.Fig. 7 Minor aphthaeFig. 10 Herpeti<strong>for</strong>m aphthae2. Major aphthous ulcers (MjAU; Sutton’s Ulcers;periadenitis mucosa necrotica recurrens(PMNR)) (Figs 8 and 9) are larger, of longerduration, of more frequent recurrence, andoften more painful than minor ulcers. MjAUare round or ovoid like minor ulcers, but <strong>the</strong>yare larger and associated with surroundingoedema and can reach a large size, usuallyabout 1 cm in diameter or even larger. TheyDiagnosisSpecific tests are unavailable, so <strong>the</strong> diagnosismust be made on history and clinical featuresalone. However, to exclude <strong>the</strong> systemic disordersdiscussed above, it is often useful to undertake<strong>the</strong> investigations shown in Table 3. Biopsyis rarely indicated, and only when a differentdiagnosis is suspected.Table 3 Investigation of aphthaeFull blood countHaematinicsFerritinFolateVitamin B 12Screen <strong>for</strong> coeliac diseaseFig. 8 Major aphthous ulceration,soft palate complexFig. 9 Major aphthous ulcerationManagementO<strong>the</strong>r similar disorders such as Behcet’s syndromemust be ruled out (see below). Predisposingfactors should <strong>the</strong>n be corrected. Fortunately,<strong>the</strong> natural history of RAS is one of eventualremission in most cases. However, few patientsdo not have spontaneous remission <strong>for</strong> severalyears and although <strong>the</strong>re is no curative treatment,measures should be taken to relieve symptoms,correct reversible causes (haematologicaldisorder, trauma) and reduce ulcer duration.Maintain good oral hygieneChlorhexidine or triclosan mouthwashes mayhelp.262 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005

PRACTICETable 4 Examples of readily available topicalcorticosteroidsSteroid UK trade name Dosage everysix hoursLow potencyHydrocortisone Corlan 2.5 mg pelle<strong>the</strong>misuccinate pelletsdissolved inmouth close toulcersMedium potencyTriamcinolone Adcortyl in Apply paste toacetonide 0.1% in Orabase dried lesionscarmellose gelatin pasteBetamethasone Betnesol 0.5 mg; use asphosphate tabletsmouthwashHigh potencyBeclometasone Becotide 100 1 puff(Beclomethasone)(100 micrograms)dipropionate sprayto lesionsTopical corticosteroids can usually controlsymptomsThere is a spectrum of topical anti-inflammatoryagents that may help in <strong>the</strong> management ofRAS. Common preparations used include <strong>the</strong>following, four times daily:• Weak potency corticosteroids topical hydrocortisonehemisuccinate pellets (Corlan), 2.5 mgor• Medium potency steroids - topical triamcinoloneacetonide in carboxymethyl cellulosepaste (Adcortyl in orabase), or betamethasoneor• Higher potency topical corticosteroids (egbeclometasone) (Table 4).The major concern is adrenal suppressionwith long-term and/or repeated application,but <strong>the</strong>re is evidence that 0.05% fluocinonidein adhesive paste and betamethasone-17-valerate mouthrinse do not cause this problem.Topical tetracycline (eg doxycycline), ortetracycline plus nicotinamide may providerelief and reduce ulcer duration, but should beavoided in children under 12 who might ingest<strong>the</strong> tetracycline and develop tooth staining. IfRAS fails to respond to <strong>the</strong>se measures, systemicimmunomodulators may be required,under specialist supervision.Key points <strong>for</strong> patients: aphthous ulcers• These are common• They are not thought to be infectious• Children may inherit ulcers from parents• The cause is not known but some followuse of toothpaste with sodium lauryl sulphate,certain foods/drinks, or stoppingsmoking• Some vitamin or o<strong>the</strong>r deficiencies orconditions may predispose to ulcers• Ulcers can be controlled but rarely cured• No long-term consequences are knownWebsites and patient in<strong>for</strong>mationhttp://www.usc.edu/hsc/<strong>dental</strong>/opath/Cards/AphthousStomatitis.htmlhttp://openseason.com/annex/library/cic/X0033_fever.txt.htmlInfectionsInfections that cause mouth ulcers are mainlyviral, especially <strong>the</strong> herpesviruses, Coxsackie,ECHO and HIV viruses. Bacterial causes ofmouth ulcers, apart from acute necrotisingulcerative gingivitis, are less common. Syphilisand tuberculosis are uncommon but increasing,especially in people with HIV/AIDS. Fungaland protozoal causes of ulcers are also uncommonbut increasingly seen in immunocompromisedpersons, and travellers from <strong>the</strong> developingworld.Herpes simplex virus (HSV)The term ‘herpes’ is often used loosely to refer toinfections with herpes simplex virus (HSV). Thisis a ubiquitous virus which commonly produceslesions in <strong>the</strong> mouth and oropharynx. HSV iscontracted by close contact with infected individualsfrom infected saliva or o<strong>the</strong>r body fluidsafter an incubation period of approximately fourto seven days.Primary infection is often subclinicalbetween <strong>the</strong> ages of 2-4 years but may presentwith stomatitis (gingivostomatitis). This isusually caused by HSV-1 and is commonlyattributed to ‘teething’ particularly if <strong>the</strong>re is afever. In teenagers or older people, this may bedue to HSV-2 transmitted sexually. Generallyspeaking, HSV infections above <strong>the</strong> belt (oralor oropharyngeal) are caused by HSV-1 butbelow <strong>the</strong> belt (genital or anal) are caused byHSV-2.The mouth or oropharynx is sore (herpeticstomatitis or gingivostomatitis): <strong>the</strong>re is a singleepisode of oral vesicles which may bewidespread, and which break down to leaveoral ulcers that are initially pin-point but fuseto produce irregular painful ulcers. Gingivaloedema, ery<strong>the</strong>ma and ulceration are prominent,<strong>the</strong> cervical lymph nodes may beenlarged and tender, and <strong>the</strong>re is sometimesfever and/or malaise. Patients with immunedefects are liable to severe and/or protractedinfections.HSV is neuroinvasive and neurotoxic andinfects neurones of <strong>the</strong> dorsal root and autonomicganglia. HSV remains latent <strong>the</strong>reafter inthose ganglia, usually <strong>the</strong> trigeminal ganglion,but can be reactivated to result in clinicalrecrudescence (see below).DiagnosisDiagnosis is largely clinical. Viral studies areused occasionally and can include:• culture; this takes days to give a result• electron microscopy; this is not alwaysavailable• polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detectionof HSV-DNA; this is sensitive butexpensive• immunodetection; detection of HSV antigensis of some value.BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005 263

PRACTICEManagementAlthough patients have spontaneous healingwithin 10-14 days, treatment is indicated particularlyto reduce fever and control pain. Adequatefluid intake is important, especially inchildren, and antipyretics/analgesics such asparacetamol/acetoaminophen elixir help. Asoft bland diet may be needed, as <strong>the</strong> mouthcan be very sore. Aciclovir orally or parenterallyis useful mainly in immunocompromisedpatients or in <strong>the</strong> o<strong>the</strong>rwise apparently healthypatient if seen early in <strong>the</strong> course of <strong>the</strong> diseasebut does not reduce <strong>the</strong> frequency of subsequentrecurrences.Recurrent HSV infectionsUp to 15% of <strong>the</strong> population have recurrentHSV-1 infections, typically on <strong>the</strong> lips (herpeslabialis: cold sores) from reactivation of HSVlatent in <strong>the</strong> trigeminal ganglion. The virus isshed into saliva, and <strong>the</strong>re may be clinicalrecrudescence. Reactivating factors includefever such as caused by upper respiratory tractinfection (hence herpes labialis is often termed‘cold’ sores), sunlight, menstruation, trauma andimmunosuppression.Lip lesions at <strong>the</strong> mucocutaneous junctionmay be preceded by pain, burning, tingling oritching. Lesions begin as macules that rapidlybecome papular, <strong>the</strong>n vesicular <strong>for</strong> about 48hours, <strong>the</strong>n pustular, and finally scab within 72-96 hours and heal without scarring (Fig. 11).treatment is indicated. Antivirals will achievemaximum benefit only if given early in <strong>the</strong> diseasebut may be indicated in patients who havesevere, widespread or persistent lesions and inimmunocompromised persons. Lip lesions inhealthy patients may be minimised with penciclovir1% cream or aciclovir 5% cream appliedin <strong>the</strong> prodrome. In immunocompromisedpatients, systemic aciclovir or o<strong>the</strong>r antiviralssuch as valaciclovir (<strong>the</strong> precursor of penciclovir)may be needed.Websites and patient in<strong>for</strong>mationhttp://openseason.com/annex/library/cic/X0033_fever.txt.htmlKey points <strong>for</strong> patients: cold sores• These are common• They are caused by a virus (Herpes simplex)which lives in nerves <strong>for</strong>ever• They are infectious and <strong>the</strong> virus can betransmitted by kissing• They may be precipitated by sun-exposure,stress, injury or immune problems• They have no long-term consequences• They may be controlled by antiviral creamsor tablets, best used early onDrug-induced ulcerationDrugs may induce ulcers by producing alocal burn, or by a variety of mechanismssuch as <strong>the</strong> induction of lichenoid lesions(Fig. 12). Cytotoxic drugs (eg methotrexate)commonly produce ulcers, but non-steroidalanti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alendronate(a bisphosphonate), nicorandil (acardiac drug) and a range of o<strong>the</strong>r drugs mayalso cause ulcers.Fig. 11 Herpes labialisRecurrent intraoral herpes in apparentlyhealthy patients tends to affect <strong>the</strong> hard palateor gingivae with a small crop of ulcers whichheals within one to two weeks. Lesions are usuallyover <strong>the</strong> greater palatine <strong>for</strong>amen, followinga palatal local anaes<strong>the</strong>tic injection, presumablybecause of <strong>the</strong> trauma.Recurrent intraoral herpes in immunocompromisedpatients may appear as chronic, oftendendritic, ulcers, often on <strong>the</strong> tongue.DiagnosisDiagnosis is largely clinical; viral studies areused occasionally.ManagementMost patients will have spontaneous remissionwithin one week to 10 days but <strong>the</strong> condition isboth uncom<strong>for</strong>table and unsightly, and thusFig. 12 Lichenoid reaction to propranololA drug history is important to elicit suchuncommon reactions, and <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong> offendingdrug should be avoided.Patients to refer:• Severe aphthae• Malignancy• HIV-related ulceration• TB or syphilis• Drug-related ulceration• Systemic disease• Mucocutaneous disorders.264 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 199 NO. 5 SEPT 10 2005