Minerva, Fall 2011 - Citizens for Global Solutions

Minerva, Fall 2011 - Citizens for Global Solutions

Minerva, Fall 2011 - Citizens for Global Solutions

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

NOVEMBER <strong>2011</strong><strong>Minerva</strong>39<strong>Citizens</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Solutions</strong>WORLD FEDERALIST INSTITUTE2 – 4 – 6 – 8 ~ CONGLOBATE!1 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>

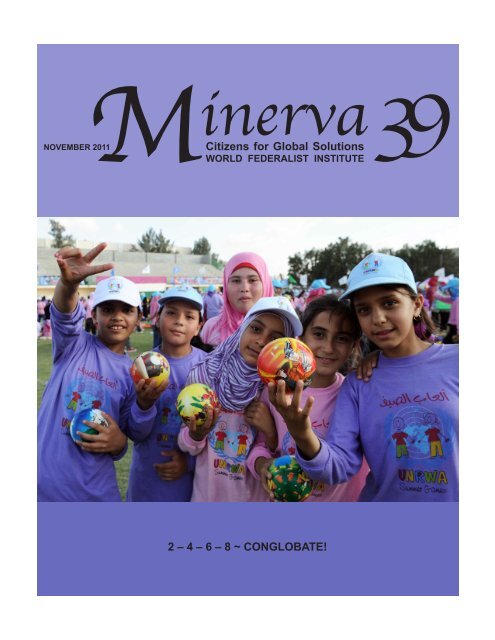

In this issue:3 • EDITORIAL COMMENT: First & Goal Thesil Morlan10 • BOOK REVIEW: Power and Arrogance David ShorrThe End of Arrogance: America in the<strong>Global</strong> Competition of Ideasby Steven Weber and Bruce Jentleson13 • The New Road to Europe: Mary KaldorWays Out of the Hydra-Headed Crisis<strong>Minerva</strong>This twice-yearly collation, provided bythe World Federalist Institute of <strong>Citizens</strong><strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Solutions</strong>, is named in honor ofone of the four women signers of the UNCharter, <strong>Minerva</strong> Bernardino (1907–1998),who helped found the UN Commission onthe Status of Women.15 • BOOK REVIEW: European Union & <strong>Global</strong> Union Ronald J. GlossopThe Uniting of Nations:An Essay on <strong>Global</strong> Governanceby John McClintock17 • Re<strong>for</strong>m of the United Nations Security Council Myron W. Kronisch& General Assembly ~ A Step to Federation19 • The UN as Truth Commission Andrew Erueti20 • INTERVIEW: The Big Picture Joanna RiceRodolfo Stavenhagen, <strong>for</strong>mer UN Special Rapporteuron the Rights of Indigenous Peoples22 • Six Scenes of Endeavor Joshua Cooper1 - UN Expert Mechanism on Rights of IndigenousPeoples | 2 - ASEAN Civil Society Conference& Peoples’ Forum | 3 - UN Human Rights Council4 - UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues5 -Threatened Island Nations | 6 - UNSC & climate change33 • Traditional Values 65 NGOs36 • INTERVIEW: Human Rights, Fundamentalism, Cassandra BalchinPower and PrejudiceVijay Nagaraj, Director,International Council on Human Rights Policy39 • NOTES on Dehumanization and Extermination40 • The Trials and Tests Faced by R2P Rachel Gerber41 • ICC - Speech at Closing of Lubanga Trial Benjamin B. Ferencz42 • ICJ - War Crimes Reparation Right Amnesty International44 • Assertive Action To Protect — Without War Lucy Law Webster45 • REVIEW of 17 BOOKS: Eliminating Nukes James T. Ranney50 • Extreme Injury Elaine Scarry54 • NOTES & RESOURCESEditor:Thesil MorlanPO Box 397Waldoboro, ME 04572Tel & Fax 207-832-6863E-mail: thesil@midcoast.comwww.globalsolutions.org/wfi/minervaEditorial Advisory Board:Robert EnholmRonald GlossopScott HoffmanTo help support <strong>Minerva</strong>, please considermaking a donation to the CGS EducationFund: 418 7th Street, SE, Washington DC20003. Thank you.In<strong>for</strong>mation cut-off <strong>for</strong> this issue:1 November <strong>2011</strong>Submission deadline <strong>for</strong> next issue:1 March 2012<strong>Citizens</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Solutions</strong> promotesdiscussion of global issues; the views presentedin <strong>Minerva</strong> are the authors’ own.COVERS - Front: UNWRA’s Gaza SummerGames, involving a quarter millionchildren, 30 June <strong>2011</strong> (UN Photo/ShareefSarhan); Back: women observe Eid al-Fitrin Dili, Timor-Leste, 1 October 2008 (UNPhoto/Martine Perret); Back cover quotationfrom A Thousand Times More Fair –What Shakespeare’s Plays Teach Us AboutJustice, by Kenji Yoshino (Ecco, <strong>2011</strong>)2 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>

First & GoalEven euphoria isn’t what it used to be.Remember a now fallen Football Hall ofFamer, as a giddy young running back,telling a post-game interviewer that he’dbeen enjoying “a metaphoric moment inthe locker-room”? Perhaps <strong>Minerva</strong> hasbeen suspiciously deficient in sports metaphors.Let’s tackle that.I was surrounded by football as a child(even though my father and mother preferredtennis and lariat twirling, respectively).In a warm climate, our familylived near an open-air football stadiumthat served the local college and highschool — whose season seemed to runmost of the year because a large stateboasts many layers of playoffs — andwhere the nearest professional teamhad its summer training camp. Night afternight, I eventually fell asleep to thesounds of play-by-play from the publicloudspeaker and organized cheers fromthe stands. “PUSH ’em back, PUSH ’emback, WAAAY back!” echoed through myslumbers. 1 “2-4-6-8 — DECIMATE!”Although I don’t claim this as a corruptinginfluence, I’m consequently not surprisedto live in a society that loves tochant “We’re number one!” on the sidelinesof games and battlefields. I’m confounded,though, by American culture’ssimultaneous fostering of reluctance tochoose superior representation in its politicalsystem. We are hobbled by smuglyasserting fictive superiority while mockingand tearing apart any discernible signsof excellence in political policy-makingor leadership.exceptionalismThe strands of our so-called exceptionalisminclude not only that conflicted claimof national superiority (oddly, furtherhardened and undermined simultaneouslyas factions haggle over which side ismore to blame <strong>for</strong> decline!) 2 but also: exceptionalismas a measure of lapse fromfoundational ideals, as a prod to improvementin that regard, or as an excuse <strong>for</strong>alleging that emergencies supersede adherenceto tradition or to the rule of law;and the assertion that international law orglobally accepted standards do not applyto a self-proclaimed virtuous country, entitledto special status.Despite the usual terminology, exceptionalistattitudes are not exclusively American.Several strands are tangled in wayspeculiar to each nation, and are sometimesmatted over broader turf, such as ahemisphere or the realms called “<strong>Global</strong>North” or “South”. There are even competingproclamations that “the West” isbest at deteriorating!But the USA does specialize in an exceptionalistoutlook that tends to be experiencedby others as at least ignorant,at worst predatory. At home, “[t]hat thecommon good requires such exceptionalismhas been so taken <strong>for</strong> granted as to notneed acknowledgment,” observes JamesCarroll, though the US Congress recentlyaimed “to convert in<strong>for</strong>mal understandinginto official legislation” in a provision ofthe National Defense Authorization Act“expand[ing] boundaries of America’smilitary mission in the world” by stretchingthe notion of our targetable enemy toinclude not only those who “committed oraided” the 2001 attacks but also <strong>for</strong>ces allegedly“associated” with designated antagonists.Although this language affirmswhat already has become practice, saysCarroll, “more than policy is at stake. Thelaw after 9/11 made an implicit claim toglobal <strong>for</strong>ce projection based on an emergency;the new legislation would explicitlyreject any time or place limitations onthat <strong>for</strong>ce. In other words, a seeminglysubtle shift marks a movement from theexceptional to the threshold of normal.There is a word <strong>for</strong> the realm into whichthat threshold opens: The legislation is astep toward an open declaration of Americanempire.” Carroll comments that, evenif instances of “‘invited’ US imperialism[are] mainly benign (which requires leavingaside questions of unfair economicstructures abroad, and dehumanizing effectsof garrison culture at home)”, andeven if “contemplated expansions of …belligerence may successfully defangterrorism (instead of sparking it), … themore far-reaching consequence of 21stcenturyAmerican empire will be the finaldestruction of authentic internationalism— nations bound by the power of agreed3 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>democratic law, cross-border systems ofchecks and balances, all abiding by thesame rules, mutually en<strong>for</strong>ced. The destruction,that is, of the only world with ahope of real peace and justice.” 3Decrying “America’s Selective Vigilantism”4 , Tariq Ali complains that, “notwithstanding”Euro-American liberal andconservative governing elites’ “pious renunciationsof terrorist violence …, theyhave no problems in defending torture,renditions, targeting and assassination ofindividuals, post-legal states of exceptionat home so that they can imprisonanybody without trial indefinitely”, whilemost citizens “avert their gaze from thedead, wounded and orphaned” afar.Even if one (a) acknowledges that humanitarianimpulses inevitably may bemixed with impure thoughts, that humanitarianexcuses often are merely addedon officially to crasser projects, or that“great-power logic soon overwhelms thehumanitarian rationale <strong>for</strong> intervention”,as Walden Bello complains 5 , but (b) doesnot go so far as to agree with Tariq Alithat NATO intervention in Libya intended“to bring the Arab rebellions to an end byasserting western control, confiscatingtheir impetus and spontaneity”, and that“the frontiers of the squalid protectoratethat the west is going to create are beingdecided in Washington”, it is painfullyobvious that our infamous cultural exceptionalismis riddled with delusions thatare dangerous <strong>for</strong> all.The delusion of being Number One, deploredby some as obnoxious and selfdefeating,diagnosed by others as a frenzycovering anxieties about being sidelined,might also sometimes be considered a bitof relief in the midst of seemingly interminablevicious squabbles — evidence thatwe can conceive of banding together afterall. But as long as this involves pushingeveryone else back — or ignoring theirexistence — it obviously doesn’t advanceus down the earth-wide field toward anydesirable, or even recognizable, goal.Political theorist Benjamin Barber 6 mocks“the American exceptionalist claim that‘We’re Number One’, when as measuredby far too many key indicators we are

actually closer to being #10 (social mobility)or maybe #34 (infant mortality)or dead last — pun intended — in thepercentage of our population we incarcerate”.He angrily challenges “the complainerswho deny the public good andinsist government is a wastrel” to “makeup their minds: do they want the UnitedStates to be a third class mini-state with afourth class public sector? In which casethey can … stop pretending we’re numberone and admit we’re actually a drop-out.Or they can try to give some substance totheir boasting and take steps to maintainour global leadership. In which case theyneed to be revitalizing and growing thepublic sector they are currently devastating.”Instead of hypocritically destroyingdemocratic governance, he argues,we need to learn to “share our commonwealth”and enable farsighted leadershiptoward that end. Unless we’re intent onstaggering backward while shoutinglouder about being number one. 7While Barber was calling <strong>for</strong> “salvagingAmerican leadership at home andabroad” last summer (“We’re Number34!”), Steve Clemons was blogging 8 froma conference in Aix-en-Provence, organizedby Le Cercle des Economistes tograpple with “The State of the World”. In“a session exploring the growing tensionbetween political rather than economiczones and whether ‘states’ were back orstill getting fuzzed up by various transnationalsaboteurs”, his New America Foundationcolleague Parag Khanna 9 “said thatglobalization is not a trend that can justbe quickly turned on and off. He thinksglobalization is a much longer, deeperprocess stretching back a thousand yearsin which the Silk Road was an early partof the plat<strong>for</strong>m. Khanna said we are ‘nowentering a phase in which globalization isreally global’ and that it can’t be slowedby the fiscal straits of a few of the largerdeveloped countries. … [He] also saidthat nation states as the term of unit inthe international system was being underminedby ‘Four C’s’ -- Countries, Cities,Companies, and Communities. Hebelieves that these groupings will shareauthorities, overlap, and intensify theircommunication and coordination in waysthat don’t depend on the state <strong>for</strong> intermediation.”10 These shifts are exposinglimits of patchwork international law aswell as of national prerogatives.commonwealWhile people continue, deliberately and/or by default, to sort out Khanna’s crisscrossed“Four C” categories and <strong>for</strong>mteams from them, vast exigencies pressureus all, threatening our lifesaving sense ofa 5th C: the Commonweal. Rescuing thismay require some rehabilitation of bodiespolitic, large and small — identifyingessential values, acknowledging sharedrights and responsibilities, and poolingsovereignty <strong>for</strong> the sake of better selfgovernmentat all levels.The holes in this early 21st-century 5th C,the Commonweal, are lined with mindbogglingnumbers: the bewildering calculationsof the financial & economiccrisis; the alarming statistics of populationgrowth, disappearing species, andclimate change; the staggering numbersof migrants, asylum-seekers, camp-boundrefugees, slum dwellers, child soldiers,victims of famines, disease, disasters,ethnic cleansing, crimes against humanity,war crimes, and genocide. And, lurkinganywhere, even where least expected(as in Norway) the “one of us” — eachunaccounted <strong>for</strong>, in numbers and linkagesunknown — who can go rogue to maimand kill in the grip of an extreme ideologyor misunderstanding or perverse impulse.scrimmageThough feeling overrun and nearly overwhelmedby the piling on of these numbers,we have realized that we have tostart somewhere to interrupt their patterns— such as committing to the MillenniumDevelopment Goals (MDGs) 11 , the InternationalCriminal Court (ICC), the principleof the Responsibility to Protect (R2P),an Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) to reducethe supply of small arms to human rightsabusers, and the proposed UN EmergencyPeace Service (UNEPS), designed tocomplement existing peace operations— even though all of these measures arediscouragingly clumsy at this early stage,without having all the necessary equipment,and without our having learned allthe necessary implementing skills yet.4 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>As <strong>Citizens</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Solutions</strong> CEODon Kraus points out, when stressing theneed <strong>for</strong> “a global 911 service that canrapidly, credibly and legitimately respondwhen a government uses its military toviolently smash peaceful protest” (UN-EPS) 12 , “you can’t protect babies from30,000 feet nor should this be the job ofthe US and its allies alone”. 13 Carrying thelatter proviso a step further, so that “militaryunits belonging to hegemonic powers— in particular, the United States andNATO — must not be allowed to participatein … intervention”, is one of WaldenBello’s five guidelines <strong>for</strong> considering alegitimate intervention (and only in “theexceptional case of genocide being carriedout by a government”) 14 . His first twocriteria, usually considered grimly late inan emergency, are that “the evidence <strong>for</strong>genocide must be substantial” and “theintervention must be a last resort, after allef<strong>for</strong>ts at stopping the genocide by diplomacy,military export bans, and economicsanctions have failed”. He scarcely mentionsthat the R2P principle also grappleswith thresholds and the right moment ofa last resort. Third, “the UN General Assembly,not the Western-dominated SecurityCouncil, must legitimize the intervention”.He does not specify whether thiswould be in the “Uniting <strong>for</strong> Peace” modeor require a different mechanism. Finally,“the expeditionary <strong>for</strong>ce must aim onlyat stopping the genocide, must withdrawonce the situation has stabilized, and mustrefrain from sponsoring and propping upan alternative government and engagingin ‘nation-building’.” Defining and securingthe stability is left an open question.Obviously, Walden Bello is discussingonly one kind of intervention. But hisopening sentence equates it with a narrownotion of R2P: “Events in Libya andSyria have again brought to the <strong>for</strong>efrontthe question of armed humanitarian interventionor the ‘responsibility to protect’.”And the scheme he outlines seemsstrangely sanitized. Atrocity reaches acalculable level, is duly stopped, and thescene magically clears itself. Instead,as Rachel Gerber observes, “Far from achecklist that mandates uni<strong>for</strong>m action,R2P is a dynamic policy framework thatis meant to twist, bend, and adapt as bestit can to the complex realities of the world

it hopes to improve. Beyond Libya andSyria, it in<strong>for</strong>ms many and diverse approachesto crisis, each of which gives ita chance to prove its mettle in the longrun.” 15 She warns that “military responsesin Libya and Côte d’Ivoire have come todominate current political discourse onthe ‘responsibility to protect’ (R2P) ina way that threatens to detract from themuch broader role the international communitycan and should play in preventingmass atrocity crimes.” 16 And, as noted frequently,prevention includes peacebuildingand other kinds of capacity-buildingin the aftermath of previous crises. 17The UNEPS plan that Don Kraus promotes“calls <strong>for</strong> the UN to individuallyrecruit, train and employ 10,000-20,000personnel [others recommend differentnumbers] with a wide range of skills, includingcivilian police, military, judicialexperts and relief professionals. It is designedto ensure that missions would notfail due to a lack of skills, equipment,cohesiveness, experience in resolvingconflicts, or gender, national or religiousimbalance. With UN Security Council approvalin hand, this <strong>for</strong>ce would have thelegitimacy to enter countries in conflictand deter mass atrocities.” 18Writing in Tripoli of his tempered hopes& concerns <strong>for</strong> Libya, 19 Nicholas Kristofproclaims himself to be “a believer in humanitarianintervention to avert genocideor mass atrocities — when [as it seemedin Libya] the stars align …” — also a difficultcriterion to ascertain! But, recognizingthat “the question of humanitarian interventionis one of the knottiest in <strong>for</strong>eignpolicy, and it will arise again,” he hopesthat next time we remember, despite thequandary of Syria, “a lesson of Libya: Itis better to inconsistently save some livesthan to consistently save none.”Still, complacency about current halfmeasuresis as unwarranted as capitulationto dreaded doom. Even those of uswho try to avoid panicked retreat from it— and also reject rushing toward doomin anticipation of rapturous selective exemption— often find ourselves hobbledby arguments about incrementalist versustrans<strong>for</strong>mative strategies. Recognizingthat mixtures of both preferences riskconfusing people further, perhaps provokingeven more resistance to either course(or to both), we are daunted by the difficultyof finding a balance — of acceptable,practical, and motivational elements— that seems as elusive as the perfectionwe know is not possible.scrumMeanwhile, within mobilizations concerningspecific issues — nuclear weaponry,nuclear power, climate change, <strong>for</strong>example — organizers warn that the natureof each overpowering danger meansthat “reality reality trumps political reality”,as Bill McKibben asserts concerningclimate change, since even projecteddevelopments short of the worst casescenario are cataclysmic, so time notonly should not, but cannot, be wastedon piecemeal fixes. 20 Others argue thatcoping with multiple crises precludes attemptingto master one deemed the mostdire while spurning small steps towardmitigating the rest.Similarly, the number of participants is indispute. Moisés Naím’s much-discussedrecommendation in Foreign Policy (2009)that <strong>for</strong> every global crisis we shouldsummon “the smallest possible numberof countries needed to have the largestpossible impact on solving a particularproblem” is countered by those whoworry with Lord Nicholas Stern, economistat the London School of Economics,that small agreements af<strong>for</strong>d only the impressionof action, exposing everyone toone or another <strong>for</strong>m of devastation. “Thescale of ambition should be commensuratewith the risks being managed, whichare enormous,” Stern says. 21Perhaps this blockage should send usdashing back to the gridiron, where asuccessful game-plan grinds out crucialinches mixed with bursts of yardage!As with arguments about increments andultimate goals, advancement stumblesover local or global focus, as if bothweren’t necessary. Actual problems withsome aspects of globalization — transnationallabor and migration issues, <strong>for</strong>example— aren’t reduced by merely batteringstraw globalization from all sides.5 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>Remedies may require more varieties ofglobalization, along lines such as thosedescribed by University of Cali<strong>for</strong>nia historyprofessor Peter Baldwin, discussingthe globalization of universities in which“reciprocity is the key concept” (“TheNarcissism of Minor Differences”) 22 —by extending beyond trends in academiclife “a kind of intellectual Brownian motionacross the globe”.After all, a trans<strong>for</strong>mative movementneeds more than a roaring “wave” runningacross one side of a stadium, wheresolidarity is unremarkable. And solidarity,“in its mundane sense”, is “morallyneutral”, as Christopher Hayes remindsus. 23 “Union members refusing to cross apicket line exemplify solidarity, but so dowhite homeowners in a Chicago neighborhoodsigning restrictive covenants tokeep black families out. Sublime solidarity,on the other hand”, developing fromempathy, “embodies a powerful moralaspiration to realize the fundamental fellowshipof humankind.” J.A. Myersonreminisces that in 1968 “[s]ublime solidaritybound the sixty-eighters to one another.… What linked the[m], the criticalfactor that turned what might otherwisehave been disparate local movements intoa global revolutionary <strong>for</strong>ce, was solidarity.Solidarity has acquired near clichéstatus, but it remains an inestimably importantingredient in the struggle <strong>for</strong> freedom,justice and equality.” 24fanfareIs this fanciful? Or is a semblance of it revealedby fanology, which studies a spectrumof loyalties of varying intensities tolearn more about group identification ingeneral and about allegiance — which,in sports, does not depend on attachmentto a winning team 25 , nor is it strictly geographical.Researchers’ findings “point toa variety of factors that contribute to fanship,including our instinct <strong>for</strong> tribal affiliation,our desire to participate in tradition,and our hunger <strong>for</strong> compelling charactersand dramatic story lines,” reports LeonNeyfakh in extremely sports-consciousBoston. 26 “If tribalism and honor exert astrong pull, there may be an even morepowerful <strong>for</strong>ce at work in getting fansaddicted to teams: the human need <strong>for</strong>

narrative. Especially <strong>for</strong> franchises withlong histories, … a big part of what hooksfans—what pushes a casual fan deeperinto the spectrum—is the multitude ofstory lines that can be seen in longstandingrivalries, the career arcs of players,and of course, individual games.” And“narrative has a self-rein<strong>for</strong>cing property”:the more familiar one is with teamhistory and the more deeply one knowsa team, the better “you’re able to keeptrack of multiple story lines at once. …”This gives people a sustaining sense ofprogress (not mere static success or depressinglydistant promise of it). Whileaccommodating fans to unpredictability,it offers, notes Neyfakh, an enlivening hitof what sports experts call “eustress” —“the addictive combination of euphoriaand stress that grips fans”, with rewardsdelivered at irregular intervals.In this context, Adam Sternbergh 27 eventouts “the epic sports collapse” that “is tobe treasured, even more so than the improbablevictory. It’s more rare, and there<strong>for</strong>emore precious. And it reaffirms theessence of why we root <strong>for</strong> a team in thefirst place. … It’s crushing, maddening,unfathomable — and yet it means nothing.… The epic collapse … is an opportunityto confront an event that’s bewildering inits unlikelihood and ruinous in its effect,yet to also walk away entirely unscarred.It matters, deeply, and yet it doesn’t matterat all. … At a time when much moredire collapses — financial, emotional,geopolitical, familial — are a frequentoccurrence or at least a consistent threat,the opportunity to experience and surviveone, however trivial or nonexistent therepercussions, is something to be valued,not lamented. It’s the one time you shouldreally be grateful <strong>for</strong> deciding to be a fan.… There is one demonstrable value to beinga sports fan. It allows you to feel realemotional investment in something thathas no actual real-world consequences.In any other contest (presidential campaigns,<strong>for</strong> example), the outcome can beexhilarating or dispiriting to its followersand, by the way, when we wake up thenext day, the course of history has beenchanged.”There are other risks, of course. 28 Unrulyfanatics abound. Weak characters whocan’t handle a heady mix of instant anddelayed gratifications can resort to hooliganism.More commonly, carelesslypoor fan manners are displayed. DanielE. Doyle Jr., who studies sportsmanship,cautions: “You have people who, emboldenedby the cover of the crowd, are ableto say anything and do anything withoutconsequences”, 29 as in other venues suchas the Internet.Corruption by peer pressure and manipulationsof fanhood to distract people fromthoughtfully asserting the responsibilitiesof citizenship are not the only factors tobe considered when gauging or endeavoringto engage public opinion, however.When it’s not going berserk, fandomrecognizes the precariousness of <strong>for</strong>tuneand security, the illusion of invincibility,the stimulation (though sometimes to excess)of opposition. Segments of a sportscrowd with different allegiances are similarlyengrossed in a partially meshed narrativeand equally vigilant <strong>for</strong> signs ofunfairness (though interpretations differ,of course), with acceptance (howevergrudging at times) of rules and referees.Flipping to the less trivial political protestversion of these tendencies, the “OccupyMovement” (<strong>for</strong> example) seems toinclude a mix of descriptive accounts ofstructural crises and angry objections togaming the system.So it may be possible to move beyondspasms of cheerleading to tap into certainfan capacities — particularly love ofnarrative 30 and fairness 31 — in ways thatrender tensions productive or rehabilitative,conducive to involvement in worldaffairs, while avoiding either paralyzingourselves with futile desire <strong>for</strong> total comityor destroying ourselves with enmity.Owning common heritage and destiny, weneed not anticipate perfectly integratedglobal brain circuitry or revert to the superiorcooperative finesse of slime moldcells. With today’s multiplicity of megaphones,global citizens — who realizethat we don’t have to think alike or loveeveryone to recognize that “we’re one!”— can lead and heed sustained summonsin support of the Commonweal: a humanehuman future.“2-4-6-8 — CONGLOBATE!”6 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>ENDNOTES:1 - University of Chicago football cheer(late 60s):Themistocles, ThucydidesThe Peloponnesian WarX-squared, y-squaredH2SO4Who <strong>for</strong>? What <strong>for</strong>?Who we gonna yell <strong>for</strong>?Go Maroons!2 - More neutrally, Adam Gopnik comments:“There’s no pattern in history tocompare us to, because nothing like usever happened be<strong>for</strong>e. The lessons of declinismare manifold, but the central oneis that obsessively fretting about possibledecline can be a good way to produce it.… Whatever happens next, short term orlong, is likely to be more affected by accidentand by invention — and by newideas — than any trend now in sight. …Declinism is a bad idea, because no onecan have any notion of what will happennext. Yet the idea of our decline is emotionallymagnetic, because life is a longslide down, and the plateau just passedis easier to love than the one comingup” (“Decline, <strong>Fall</strong>, Rinse, Repeat — IsAmerica Going Down?”, The New Yorker,12 September <strong>2011</strong>).Aside from the death link, Gopnik is notsurprised that many voters refuse to act to“maximize future utility” and even preferto ignore their own interests: “In the longstory of civilization, the moments whenimproving your lot beats out annoyingyour neighbor are vanishingly rare.”3 - James Carroll, Boston Globe, 16 May<strong>2011</strong>4 - Tariq Ali, British/Pakistani politicalcommentator and editor of the New LeftReview, “America’s Selective Vigilantism”,The Guardian, 7 September <strong>2011</strong>):“‘Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,’Carl Schmitt wrote in differenttimes almost a century ago, when Europeanempires and armies dominated mostcontinents and the United States was baskingbeneath an isolationist sun. What theconservative theorist meant by ‘exception’was a state of emergency, necessitated byserious economic or political cataclysms,that required a suspension of the constitution,internal repression and war abroad.”

5 - Walden Bello, Princeton-educatedFilipino political analyst & activist, politician,professor of sociology & publicadministration at the University of thePhilippines, Executive Director of Focuson the <strong>Global</strong> South (based in Bangkok),and Fellow of the Transnational Institute(based in Amsterdam), “The Crisis of HumanitarianIntervention”, Foreign Policyin Focus (“A think tank without walls”)- AProject of the Institute <strong>for</strong> Policy Studies,9 August <strong>2011</strong>; his books include The Futurein the Balance: Essays on globalisationand resistance (2001)6 - Benjamin Barber, Distinguished Fellowat the Demos policy center, “We’reNumber 34!”, Huffington Post, 25 July<strong>2011</strong>7 - On an index produced by law professor(and <strong>for</strong>mer administrator of the UNDevelopment Program and co-founderof the Natural Resources Defense Council)James Gustave Speth, among the 20major “advanced” countries, the US doesrank highest in the poverty rate, inequalityof incomes, prison population per capita,international arms sales, and failure toratify international agreements.Despite evidence of problems that he expectsto worsen or at least “continue tofester” <strong>for</strong> “the <strong>for</strong>eseeable future”, Speth(as quoted by William Fisher in a Truthoutop-ed ”American Exceptionalism”, 29August <strong>2011</strong>) believes: “There is hope especiallyin three things. The decline nowoccurring will progressively delegitimizethe current order. Who wants an operatingsystem that is capable of generatingand perpetuating such suffering and destruction?The one good thing about thedecline of today’s political economy isthat it opens the door to something muchbetter. Second, people will eventually riseup, raise a loud shout and demand majorchanges. That is already happening withsome people in some places. Eventually,the chorus will grow to become a nationaland global movement <strong>for</strong> trans<strong>for</strong>mation.And third, Americans are already busywith numerous, mostly local initiativesthat point the way to the future.”8 - On Steve Clemons’ page <strong>for</strong> The WashingtonNote at The Atlantic, 9 July <strong>2011</strong>9 - Born in India, having grown up in theUnited Arab Emirates, New York, andGermany, and having been educated atthe London School of Economics andGeorgetown University, geo-strategistParag Khanna is, in addition to his positionas a Senior Research Fellow at theNew America Foundation, Senior Fellowat the European Council on Foreign Relations,Director of the Hybrid Reality Institute,and author of The Second World:Empires and Influence in the New <strong>Global</strong>Order (2008) and How to Run the World:Charting a Course to the Next Renaissance(<strong>2011</strong>).10 - On another occasion (“InnovationAmidst the Wreckage of America’s Empire”,The Washington Note, 17 January<strong>2011</strong>), commenting on Parag Khanna’sHow to Run the World: Creating aCourse to the Next Renaissance, SteveClemons questions Khanna’s observationsabout “a much more complex …diffusion of actors and speeding up of internationalinteractions”, saying he thinks“the proliferation of large-scale NGOsand the surge of diplomatic activity by nationssuch as Brazil, South Africa, Turkeyand others may not be examples of the‘mega-diplomacy’ Khanna observes andadvocates but rather examples of whathappens when a hegemon collapses. Allof this seemingly rich and diverse activitymay be manifestations of America’sloss of control, its diminishment on theinternational stage — where other playersfill voids, co-opt parts of the sprawlinginfrastructure of America’s <strong>for</strong>eign policyframework, and test the reset boundariesof power in a world of US strategiccontraction. I fear that we won’t knowwhether the world we are moving intois more stable and better run given thisflood of new institutions and states intoglobal stewardship roles than that we hadin the past — but Parag Khanna seemsto embrace it.” Clemons thinks Americacan salvage some leverage, but “the juryis out on America being able to recreate aglobal social contract with other nationsand players in the international system…. [W]e may be as Khanna believes onthe way to some version of a neo-Medievalglobal arrangement, though the termis tough to use because it comes with somuch distracting baggage, but if we get7 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>there — there’s no assurance of a Renaissanceat the other end.”See also Foundation on Economic Trendspresident Jeremy Rifkin’s new book, TheThird Industrial Revolution: How LateralPower is Trans<strong>for</strong>ming Energy, theEconomy, and the World. He summarizeshis thesis in a response to Huffington Postenvironmental reporter Tom Zeller, Jr. (26September <strong>2011</strong>): “The Third IndustrialRevolution is the last stage of the greatindustrial saga and the first stage of theemerging collaborative era rolled together.It represents an interregnum betweentwo periods of economic history — thefirst characterized by industrious behaviorand the second by collaborative behavior.If the industrial era emphasized the valuesof rigid discipline and hard work, the topdownflow of authority, the importanceof financial capital, the workings of themarketplace and private property relations,the collaborative era is more aboutcreative play, peer-to-peer interactivity,social capital, participation in open commonsand access to global networks. …In the new era, providers and users aggregatenodally in vast networks and carryon commerce and trade in commercialarenas that function more like commonsthan markets. A more distributed and collaborativeindustrial revolution, in turn,invariably leads to a more distributedand collaborative sharing of the productivewealth generated by society. … Themetamorphosis from an industrial to acollaborative revolution represents one ofthe great turning points in economic history.”11 - Valdênia A. Paulino Lanfranchi, alawyer who grew up in Brazil’s favelas, isthe founder of the Sapopemba Center <strong>for</strong>Human Rights in São Paulo and has takenpart in in<strong>for</strong>mal hearings with the UNGeneral Assembly concerning the MillenniumDevelopment Goals. In an interviewlast year (Amnesty International, TheWire, August/September 2010), she said:“Universal and indivisible human rightsis the only way to ensure the inclusionof marginalized and neglected groups inthe UN Millennium Development Goals(MDGs) process. A great portion of theworld’s population – the poorest in allcountries and the poorest countries –haven’t yet been significantly affected by

the ef<strong>for</strong>ts to achieve the MDGs. We willhave an estimated 1.4 billion people livingin slums in 2015. We are not dealingwith ‘minority’ groups here. Millions ofhomeless and landless people cannot be aminority. They can’t be left out. A holistichuman rights perspective must spur discussiontowards a new socially inspiredeconomic and political world order as theonly way to overcome poverty, hungerand disease and sustain common life onthis resource-limited planet. Such an immensetask will call <strong>for</strong> collective actionwell beyond 2015.”Phyllis Bennis, a Fellow of the Institute <strong>for</strong>Policy Studies and the Transnational Institutein Amsterdam, argues that, insteadof searching <strong>for</strong> new strategies to achievethe Millennium Goals, the MDGs shouldbe re-construed as MDRs — MillenniumDevelopment Rights (YES! Magazine,27 September 2010). Then grim realitiescould be changed “through building anew internationalist movement, involvingcivil society AND governments AND theUnited Nations. And a movement basedon rights — with accountability whenthose rights are violated.”12 - Don Kraus, “The Arab Spring and a<strong>Global</strong> 911”, guest post on care2make adifference, 16 May <strong>2011</strong>13 - Don Kraus, The <strong>Global</strong> Citizen blog, 18 April <strong>2011</strong>14 - “With these guidelines,” assertsWalden Bello, referring to perspectivesattributed to the <strong>Global</strong> South, “very fewhumanitarian interventions would havequalified as valid and carried out legitimatelyin the last 40 years. There are perhapsonly two: the Vietnamese invasionto remove the blood-thirsty Khmer Rougefrom power in 1978 (though this lackedUN sanction) and the UN-led multinational<strong>for</strong>ce INTERFET that ended thegenocidal killings and deportations ofTimorese by Indonesian-backed militiasin 1999.”15 - Rachel Gerber, “The Trials and TestsFaced by R2P”, The Stanley Foundation’sthink., August <strong>2011</strong>; reprinted here, page4016 - Rachel Gerber, “Mass Atrocities andthe International Community: The MultilateralFramework <strong>for</strong> Prevention and Response”,The Stanley Foundation’s think.,April <strong>2011</strong>17 - For example: the work of the UNbackedInternational Commission AgainstImpunity in Guatemala (CICIG). Createdin the fall of 2007, the CICIG is describedby David Grann (“A Murder Foretold —Unravelling the ultimate political conspiracy”,The New Yorker, 4 April <strong>2011</strong>)as “a path-breaking political experiment.Unlike many truth commissions or humanrights bodies, it does not investigatewar crimes of the past, or merely monitorabuses. Rather, it aggressively fightsagainst systemic violence and corruption…. Composed of several dozen judges,prosecutors, and law-en<strong>for</strong>cement officialsfrom around the world, CICIGworks within Guatemala’s legal systemto prosecute members of organized crimeand dismantle clandestine networks embeddedin the state.”Thanks to national and international pressure,the Guatemalan Congress approvedthe International Commission AgainstImpunity in Guatemala on 1 August 2007.The CICIG is set up to support the PublicProsecutor’s Office, suggesting methodsof investigation and presenting evidence.The Public Prosecutor’s Office has ultimateresponsibility <strong>for</strong> deciding whetheror not to pursue an investigation. It is partlyintended to interrupt the operations ofclandestine groups that undermine respect<strong>for</strong> the rule of law and human rights.8 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>In a recent high-level case (Amnesty Internationalpress release, 26 November2010), the Guatemalan Public Prosecutor’sOffice brought charges against <strong>for</strong>merInterior Minister Carlos Vielman“and 19 individuals, some of whom arein custody, <strong>for</strong> their alleged participationin the extrajudicial execution of prisonersin several Guatemalan jails. These actionshave the support of the CICIG. FormerNational Director of Police Erwin Sperisen,currently resident in Switzerland, andother <strong>for</strong>mer officials are being investigatedover the killings of prisoners heldat two prisons in Guatemala in 2005 and2006.” Carlos Vielman was arrested on13 October in Madrid following a judicialrequest by the Guatemalan Public Prosecutor’sOffice, supported by the CICIG.He was released by the Spanish authoritieson 23 November, after Guatemalafailed to meet a deadline <strong>for</strong> filing theproper documentation <strong>for</strong> his extradition.18 - Don Kraus, care2make a difference,16 May <strong>2011</strong>: “In the meantime the USshould support the deployment of UNpeacekeepers on the ground to protectcivilians; provision of food, water, medicineand shelter <strong>for</strong> displaced Libyans;and UN sponsored elections to bring democracyand a legitimate government.”19 - Nicholas Kristof, New York Times, 7September and 31 August <strong>2011</strong>20 - Bill McKibben, Reader SupportedNews, 16 April <strong>2011</strong>: “Climate change,above all issues, requires a trans<strong>for</strong>mativeand not an incremental vision. We havefundamental change to make, and a veryshort window to make it in — Obama’stypical (and often quite savvy) little-bitat-a-timeapproach doesn’t square withthe physics and chemistry that govern thisdebate.”21 - Naím and Stern, along with severalother debaters on this issue, are quoted byThanassis Cambanis, author of A Privilegeto Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legionsand Their Endless War Against Israel, in“No Big Deal — The key to solving theplanet’s most daunting problems: thinksmall”, Boston Globe, 9 January <strong>2011</strong>.22 - Peter Baldwin, “The Narcissism ofMinor Differences: How America andEurope Are Alike”, New York Times, 28November 201023 - Christopher Hayes, of The Nation,“In Search of Solidarity”, In These Times,3 February 200624 - Editor & artist J.A. Myerson, “‘ArabSpring’ Label Hampers <strong>Global</strong> Protests’Solidarity Potential”, Truthout, 9 July<strong>2011</strong>25 - “For a team to be lovable, it helpsnot to be great or too great, but rather tohave a chance to win or get lucky,” saysLawrence Wenner, of Loyola MarymountUniversity, author of the MediaSport and<strong>for</strong>mer editor of the Journal of Sport andSocial Issues (quoted in 26, below).26 - Leon Neyfakh, “How Teams TakeOver Your Mind”, Boston Globe, 24 April<strong>2011</strong>; see also: Sports and Their Fans, by

Kevin Quinn, on the tribal aspect; and, oninculcation processes, Fandom: Identitiesand Communities in a Mediated World,edited by Jonathan Gray27 - Adam Sternbergh, “The Thrill ofDefeat <strong>for</strong> Sports Fans”, New York TimesMagazine, 21 October <strong>2011</strong>28 - Seeking fans, while promising to increasethe size of the military by 100,000,Mitt Romney exclaimed in October to cadetsat The Citadel: “This century must bean American century. America leads thefree world and the free world leads the entireworld. God did not create this countryto be a nation of followers.”Andrew Bacevich lamented the increasinglydominant requirement of militaristicpiety in public life: “In his Citadel speech,Romney said nothing that a thousandpoliticians and pundits have not alreadysaid a thousand times and will say again.The significance of his presentation liesnot in its originality but in its familiarity”(“America: with God on our side”, LosAngeles Times, 16 October <strong>2011</strong>).29 - Daniel E. Doyle Jr., executive directorof the Institute <strong>for</strong> International Sportat the University of Rhode Island, NewYork Times, 5 September <strong>2011</strong>30 - For example: “What matters [to thepublic] is the story of America, not theideological structure of American exceptionalism.”- Steven Knapp, president ofThe George Washington University, “TheEnduring Dilemma of the Humanities”,The Key Reporter, Summer <strong>2011</strong>See also Vijay Nagaraj on the humanrights “counter-narrative” to religiousfundamentalisms, page 36 of this issue.31 - From Former Under SecretaryGeneral of the United Nations BrianUrquhart’s Afterword to Working Paper40 of the Brookings <strong>Global</strong> Economy andDevelopment program, Does FairnessMatter in <strong>Global</strong> Governance?, by HakanAltinay, a nonresident senior fellowwith that program: “A universal traditionof fairness and public spirit — a gloriousobjective — will not be created quicklyor easily. This is why the foundation fromwhich it can grow needs to be establishedas soon as possible. … Until the recognitionof the notion of human dignitybecomes universal rather than a distantaspiration, progress in establishing universalrespect <strong>for</strong> human rights will remainpartially unfulfilled, and the growthof a universal tradition of fairness will bestunted.“Anyone who has worked <strong>for</strong>many years in an admittedly flawed internationalsystem becomes accustomed tobeing called deluded, naïve or unrealistic.In the end, however, it is possible to lookback on a surprising degree of progressthat was difficult to discern at the time,sometimes toward objectives that werepreviously thought to be hopelessly unattainable.Fairness and civility are vastobjectives even <strong>for</strong> a single state, but ifwe pride ourselves on having achievedglobalization and a revolution in humancommunication, why should fairnessand civility not also be global objectives?Such vast objectives may neverbe altogether realized. They stand as aguide to behavior, a great work in continualprogress …”ïThe “nuclear football”— accompanying the US president —is housed in a modified Zero Halliburtonattaché case (Photo: John Caruso)9 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>rugbyALTERNATIVESSecretary-General Ban Ki-moon, at thePacific Islands Forum summit meetingin New Zealand, just be<strong>for</strong>e the RugbyWorld Cup there (September <strong>2011</strong>):New Zealand is the magnificent meetingground of both the world of diplomacyand the world of rugby. I have come torealize that those worlds are not as differentas you might think. In rugby, you loseteeth. In diplomacy, you lose face. Rugbyscrums confuse anyone who doesn’t knowthe game. So do UN debates. And sometimesthey can look very similar. And yet,in heart and spirit the Rugby World Cupis a celebration, a celebration of commonvalues and a way of life: teamwork, mutualrespect, solidarity. The qualities ofgrit and determination — all very useful,I have found, in the world of diplomacy.soccerI would rather lose as Scotland than winas Great Britain.~ Craig Brown,<strong>for</strong>mer Scotland manager who nowcoaches Aberdeen, expressing reportedlywidespread sentiment as to whether thereshould be a team of English, Welsh, Scotsand Northern Irish players at the Olympicsin London (The Guardian, mid-September<strong>2011</strong>)

From “Imperiled Revolutions”,by Stephen Eric Bronner(RSN Perspective, 24 June <strong>2011</strong>) ~Stephen Eric Bronner is DistinguishedProfessor of Political Science and Directorof Civic Diplomacy & Human Rightsat the Institute <strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> Challenges,Rutgers University, Senior Editor of Logos:A Journal <strong>for</strong> Modern Society andCulture, and author of Peace Outof Reach: Middle Eastern Travelsand the Search <strong>for</strong> Reconciliation,among other works.The Arab Spring was marked by spontaneousrevolts, lack of charismatic leaders,youthful exuberance, and disdain <strong>for</strong>more traditional <strong>for</strong>ms of organizationaldiscipline. That is what made these revolutionsso appealing. Institutional obstaclesto democracy, however, requireinstitutional responses: speaking truth topower is no longer enough. Success nowhinges on the organization of power bythe <strong>for</strong>mer insurgents and their ability todeal with the armed <strong>for</strong>ces, the bureaucracy,religious institutions and the globaleconomy. …Revolution is a daunting task,but running a country the day after is perhapsan even more daunting proposition.New liberal republics in economicallydisadvantaged circumstances will need tonavigate a swirl of conflicting economicinterests and illiberal institutional claims.These are not discrete concerns though, ineach circumstance, the art – not the science– of politics is required to providean integrated set of responses. Ignoringthe logic of power is no solution. Only byconfronting reactionary and exploitativeinterests with an eye privileging the commonneeds of the disenfranchised and theoppressed will a fresh breeze sustain theArab Spring.ïThe United States mustundoubtedly be more consciousof how it appears to others, lesspresumptuous about the advantagesit has enjoyed in the past,and more respectful of the needsand perspectives of other nations.Power and ArroganceBOOK REVIEW:The End of Arrogance:America in the <strong>Global</strong> Competition of Ideasby Steven Weber and Bruce JentlesonDavid ShorrApril <strong>2011</strong>David Shorr is a program officer at theStanley Foundation and a member of theboard of <strong>Citizens</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>Global</strong> <strong>Solutions</strong>Education Fund. Co-editor of Bridgingthe Foreign Policy Divide (Routledge)and a contributor to the <strong>for</strong>eign policyblog Democracy Arsenal, he teachesUS <strong>for</strong>eign policy at the University ofWisconsin-Stevens Point.Reprinted from Policy Review,a publication of the Hoover Institution,Stan<strong>for</strong>d University.The most interesting questions <strong>for</strong> US <strong>for</strong>eign policy are variants of the following:How much has the world changed? As America tries to prod world affairs along itspreferred trajectory, how has that task been complicated by new international realities?The debate over whether America is in decline misses the point. The signs of asignificant shift in international power are just too plain and numerous <strong>for</strong> anyone todoubt that the United States faces new challenges in exerting its influence. But again,this leaves plenty of open questions about the nature of those challenges.Steven Weber and Bruce Jentleson’s new book, The End of Arrogance: America in the<strong>Global</strong> Competition of Ideas, tackles these most basic issues head-on. The authors offera bracing assessment of the international environment US policymakers confront. Ifthe first step in overcoming any self-delusion is to recognize that you have a problem,Weber and Jentleson are trying to jolt America out of its self-absorption. Just to stretchthe analogy, consider the book an intervention — its authors giving tough love to fellow<strong>for</strong>eign policy thinkers who are addicted to an outmoded ideology of Americanleadership. They liken the delusion to the Copernican paradigm shift undercutting theimage of the earth at the center of the universe; the United States has lost its politicalgravitational pull.Putting it succinctly, the book answers this essay’s opening question by saying theworld has changed a lot more than we have admitted to ourselves. Assumptions aboutAmerica’s advantages are ripe <strong>for</strong> reexamination. The authors dissect even the milderconceptions of American exceptionalism. In other words, their critique covers conservativesand liberals alike.10 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>

Among their targets is the notion thatthe US political and economic modelfaces no significant rivals, because thesupposed contenders have such limitedappeal or applicability. The argumentis indeed familiar — and com<strong>for</strong>ting inits reassurance. The Chinese dynamo ofexport-led state capitalism is very hard toreplicate. The Singapore model dependson its peculiar geography. FundamentalistIslam is too inhuman. Anti-Americanismis a purely negative phenomenon. American-styledemocracy and free marketsare dominant paradigms because no othersare as coherent or systematic or canmatch their record of success.But this is a false com<strong>for</strong>t, Weber andJentleson argue. The main fallacy —aside from the stubborn fact of China’seconomic success — is that only universallyapplicable, all-encompassing theoriescan contend as rivals. In other words,while America presumes that it has wonthe grand historical argument about governanceand economic management, wehave misunderstood how that argumentplays out in the real world of global politics.Resistance to American leadershipand the emergence of counter-argumentsdon’t need to be undergirded by fullyworkable ideologies.So it is a mistake to view American approachesas vying in a war of ideas, inwhich one model decisively vanquishesanother. And despite the use of the Copernicanrevolution as a reference point, thebook also warns against the image of scientificadvances, with theories gaining acceptancedue to their superior explanatorypower. A much better analogy <strong>for</strong> how itworks, say the authors, is the competitionof the commercial marketplace.In his recent state of the union address,President Obama adopted similar themesof American economic dynamism asstrengthening national competitiveness,but End of Arrogance is a methodicalreconception of US <strong>for</strong>eign policy challengesin terms of the global competitionof ideas. A main thread of the book is towarn against taking anything <strong>for</strong> granted,beginning with the “five big ideas [that]shaped world politics in the twentieth century”:the preferability of peace to war;benign (American) hegemony to balanceof power; capitalism to socialism; democracyto dictatorship; and Western cultureto all others. Jentleson and Weber portrayan international order that is up <strong>for</strong> grabsat the beginning of the 21st century. Theirclaim that nations and leaders are workingwith a clean slate probably overstatesthe case, but most of the book charts acredible course to renewed US globalleadership.The heart of the book’s first section describesessential market dynamics andkey principles:In a functioning modern marketplace ofideas, at least three things are true of atwenty-first-century leadership proposition.First, we offer, but they choose. Amarket leader is fundamentally more dependenton the followers than the followersare on the leader . . . Second, the relationshipsare visible and consistency isdemanded. Market leaders don’t dependheavily on private deals and subterfuge tohold their bargains in place . . . Finally,there is real competition. Markets are relentlessin their ability to generate newofferings.The authors describe some key challengesin the contemporary marketplace, all ofwhich lower the barriers to entry <strong>for</strong> ourcompetitors. They highlight the revolutionin in<strong>for</strong>mation and communicationstechnology, demographic trends that fillmegacities with young people whoseworldview is non-Western, the openingsprovided by the diffusion of authority,and the permeability of national borders.The section concludes with a sobering assessment:In 2010, globally, there remains a deepskepticism about the proposition that theUnited States can be more powerful andthe world can be a better place at thesame time. The belief that these two thingscould be consistent or even rein<strong>for</strong>ce eachother was the most valuable and preciousadvantage America had in the post-WorldWar II milieu. It has eroded and thatchanges the nature of ideological competitiondramatically. A new <strong>for</strong>eign policyproposition has to find a way to put thatbelief back into play.11 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>A stark, yet apt, summary of our currentstrategic challenge.The book’s middle two chapters outlinethe substance of leadership propositionsthe United States could offer as a basis<strong>for</strong> equitably just societies domesticallyand new political terms <strong>for</strong> internationalorder. Since the authors’ project is to shedthose conceits that represent the toughest“sell” <strong>for</strong> the hegemon, their leadershippropositions have a distinctly strippeddowncharacter. In place of democraticideology — electoral competition and thepopular mandate — the essential elementsof a just society are the empowerment ofpeople to lead fulfilling lives and protectionof the vulnerable, those buffeted by<strong>for</strong>ces of rapid change such as extremeweather, industrial accidents, or spikes inthe price of staple foods.As the authors step out of ingrainedAmerican worldviews to gain perspectiveon democracy, they make a compellingpoint about the weaknesses thatothers perceive. After all, democracy isa decision-making process rather than atangible benefit <strong>for</strong> people’s lives. In thewide swath of the world where daily lifeis a grinding struggle, to idealize processand treat material conditions as secondaryand contingent must seem exotic.Just as the book proposes revised standardsof good governance, it issues asimilar challenge to recast the internationalpolitical order. Again the root ofthe problem is complacency; Americansare still trying to dine out on our authorshipof the post-World War II order whenthe resonance of that creation myth hasfaded. Rather than dismissing the merenotion that the postwar order could be (orhas already been) upended, we should tryto get out ahead of the revision process.One of the authors’ refrains is that whilethe US political elite is consoling itselfthat “there is no alternative”, much of therest of the world is insisting that “theremust be an alternative”.The leadership proposition that Weberand Jentleson put <strong>for</strong>ward is a responseto the interconnected 21st-century world,and rightly so. The difficulty is that theprecursors <strong>for</strong> a peaceful and prosperous

order — which they identify as “security,a healthy planet, and a healthfully heterogeneousglobal society” — can onlybe achieved through combined ef<strong>for</strong>t.In other words, if all of the world’s keyplayers deal with the international systemby trying to maximize their own nations’benefits and minimize their contributions,the world as a whole could face a prettybleak future.As a key to spurring a more civic-mindedattitude from nations and their leaders,the authors offer an alternative to narrowand short-sighted conceptions of nationalinterest: the principle of mutuality. Whenpolicy-makers mull tough diplomaticcompromises or tithes they might contributetoward global public goods, theyshould use an accounting system thattakes a long view. They shouldn’t expectrepayment or benefits of equal value, butshould instead trust that if everyone doeshis part, “an ongoing set of mutualitymoves will roughly balance out the accountsand leave us all better off than wewere”.The book’s concluding chapter highlightsfour major <strong>for</strong>eign policy dilemmas thatwill test America’s international strategy.To stress the importance of those toughchoices, the authors give their thoughtson the discipline of strategy: “Anybodycan tell a story about the world they wantto live in. Strategy is the discipline ofchoosing the most important aspects ofthat world and leaving the other stuff behind.”As they see it, the trickiest questionshave to do with the proper role ofnonstate actors versus official authorities;multilateralism as a false panacea <strong>for</strong>international challenges; populist pressuresdemanding more than democraticgovernance and free markets can deliver;and the difficulty of reckoning short-termcosts in light of long-term risks (think climatechange).Here’s how I would answer my openingquestion about how much the world haschanged: not as much as Jentleson andWeber say it has. The End of Arroganceworks very well as a provocation, yet theauthors’ insistence that we are back to thedrawing board of a new global order is abit excessive. Their report of the postwarorder’s demise is greatly exaggerated.While it may be overly complacent to assertthat “there is no alternative”, it’s alsotoo early to declare the old rules invalid.Indeed, one of the book’s most dramaticclaims is to declare the very notion ofrules to be passé. In keeping with the ideaof a relentlessly competitive, constantlychurning marketplace, the new internationalorder consists of a stream of intergovernmentaltransactions. As the authorsput it, diplomatic deals are taking theplace of international norms at the heartof the system.If they’re right, the world has been turnedupside down, and most of us in the <strong>for</strong>eignpolicy establishment failed to notice it —international politics as a new global WildWest. Can that be right, though? I don’tthink so. It’s one thing to face up to thepolitical strains that indeed jeopardize thenorms put in place over the last 65 years,and yet another to declare that the old rulebooks have gone out the window.When Weber and Jentleson describe anew political system in which each nation’spolity and social order are beyondthe bounds of international relations, youhave to give them credit <strong>for</strong> practicingwhat they preach about strategic disciplineand abandoning secondary concerns. Inone section, they try to get a jump on theircritics with a preemptive defense againstcharges of betraying moral values. Theauthors insist that they fully share the valuesof liberty and democracy. It’s just thatthe authors’ own views — and by extensionthose of the American leadership andpublic — do not represent the weight ofinternational sentiment and there<strong>for</strong>e donot set the terms <strong>for</strong> the global politicalorder. As a matter of political assessment,they see only enough consensus amonggovernments <strong>for</strong> them to deal with oneanother as equally sovereign authoritiesin the international arena. Governanceprinciples <strong>for</strong> how they act within theirown borders are too divisive and controversialto serve as a basis <strong>for</strong> internationalorder.In such a system, would the United Statesbe compelled to back Hosni Mubarakto the bitter end? End of Arrogance waspublished be<strong>for</strong>e the recent protests in12 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>Egypt, but the book says enough aboutthe hazards of getting involved in others’governance to allow <strong>for</strong> some extrapolation.Jentleson and Weber’s view doesn’tnecessarily imply unstinting support <strong>for</strong>a dictator faced with mass discontent.Given their emphasis on political realities,it would be surprising if the authorscalled on US policy-makers to ignore thewriting on the wall. Machiavelli himselfwould have recognized that Mubarak wasneither loved nor feared enough to retainpower.On the other hand, the authors’ viewsseem to align them with the series of USambassadors in Cairo who counseledagainst any serious pressure by Washingtonon Mubarak to re<strong>for</strong>m Egypt’s politicalsystem. In other words, I interpret thebook as an argument <strong>for</strong> giving Mubaraka shove at the end, but not laying afinger on him be<strong>for</strong>e then. Among theircomments on democratic principles, theauthors remind us of the long record ofAmerican hypocrisy — the dictators supported,the democratically elected governmentsoverthrown. And remember,among their tenets of the marketplace ofideas is that a nation must be consistent toremain credible, given the market’s highdegree of transparency. The apparent answeris to give up any pretense of defendingdemocratic principles abroad.Given the scope and speed of change intoday’s world, it is highly useful to havea book that keeps us from being too com<strong>for</strong>table.US <strong>for</strong>eign policy indeed confrontshard choices and trade-offs andmust do a better job in wrestling withthese dilemmas. Yet I have to ask whetherthis framework has boxed us in more thannecessary. Must the discipline of strategybe so stringent that second-tier concernsbe jettisoned rather than kept in proportion?Just because the norms of the oldorder have come under significant newskepticism and resistance, does that meanthey are null and void? Does the globalmarket demand such consistency that internationalpublics cannot understand thecompeting pulls of democratic principles,stability considerations, and power realities?[continued]

The protestors in Tahrir Square and elsewherein the Middle East, the indignadosin Spain and Greece or the wütburger inGermany, ... are experimenting with newsocial arrangements and new <strong>for</strong>ms ofdiscursive democracy. But they need aninstitutional response. Change is blockedat a national level, the policies and assumptionsof the past are imprinted on thestructures of the nation-state and on theassumptions of national politicians. Somechange is possible at local and regionallevels but there also needs to be a globalagenda, especially in the fields of finance,security and environment.The hydra-headed crisis is also a Europeancrisis. The crisis of the euro, likethe wider financial crisis, is an expressionof deeper underlying factors. Yet theEuropean Union also could represent ananswer to the crisis. It has to go <strong>for</strong>wardsif it is not to go backwards. To save theeuro, policies will have to be adoptedthat could offer a model <strong>for</strong> the rest ofthe world. This may well not happen, ofcourse, but that is why activists and othersneed to campaign at a European level andnot just at local and national levels.The reason that the European Union containsthe seeds of a solution is because itis a new type of political animal. It originatedas a peace project, in reaction to twoworld wars and the holocaust. By trial anderror, it has developed as a new <strong>for</strong>m oftransnational governance designed not todisplace the nation-state but to constrainits dangerous tendencies. It adds a newlayer of political authority rather than establishinga new pole of political authority.It is a multilateral institution but goesbeyond internationalism (between states)and possesses an element of supra nationalism(beyond states). It offers new possibilities<strong>for</strong> public intervention that is notstate-based.In practice, actually existing Europe appearsvery different. Indeed, it seems to belittle more than a neo-liberal bureaucracy.As Pianta and Rossanda have shown, theneoliberal policies that underpinned theeuro have been immensely destructive insocial and economic terms. The LisbonTreaty was supposed to establish a moreunified political leadership but in fact itproliferated Presidents largely unknownto the public – the Union now has a Presidentof the Council, a rotating Presidencyof the Council, a <strong>for</strong>eign minister, a Presidentof the Commission, all appointedthrough a murky backstage method andfew European citizens are even awareof who they are. The result is a politicalvacuum made worse by a tendency <strong>for</strong>national governments to blame Europe<strong>for</strong> their own incapacity to respond topopular demands.Yet precisely because the European Unionis new type of political animal it has thepotential to address some of the underlyingsources of the crisis in a way that isnot possible <strong>for</strong> nation-states. There is, ofcourse, a risk that the euro will collapseand that the EU will disintegrate. But inorder to <strong>for</strong>estall that possibility somechanges are happening almost by stealth.Eurobonds have, in effect, been createdby the decision to convert national debtto European debt. Almost unnoticed,President Sarkozy and Chancellor Merkelagreed to a tax on financial transactions–something long demand by activists inthe social <strong>for</strong>ums.At root the weakness of the Europeanproject was that it has always been anelite project. It lacks the social compactthat underpinned the state. The protestorsin different parts of Europe are howevermainly focussed on local demands, butthose local demands can only be met withina wider European framework. How canthe current popular mobilisation connectup and frame a European agenda? Suchan agenda might include:• A new fiscal mechanism that would raisetaxes at a European level – a tax on financialtransactions <strong>for</strong> example, and acarbon tax – and would increase spendingand redistribution at a European level.• A new social policy aimed at reducinginequality and promoting jobs, especially<strong>for</strong> young people. Some have proposed aMarshall Plan <strong>for</strong> youth.• An economic strategy aimed at resourcesaving as opposed to labour saving thatwould be both economically and environmentallysustainable.14 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>• A renewal of the peace project includingcosmopolitan citizenship, reaching out tothe new democracies in the Middle Eastthe way it reached out to Eastern Europe,and a human security rather than a nationalsecurity policy.• A reinvigoration of democracy both locallyand at European level — a widespreaddebate at local levels, in town hallsand public squares, as well as a way ofpublicly electing an accountable politicalleadership.Change of this kind in Europe could havefar reaching consequences <strong>for</strong> global arrangements.The EU is still the largestsingle economy in the world. But it lackspopular legitimacy. How can the road toEurope be reinvigorated from the bottomup? Is another Europe possible? A peacegreen-democratic-cosmopolitanEuropeinstead of a neo-liberal bureaucracy?The goal is to provide an institutionalmodel that could tackle the multiple crisesthat are piling up, that could channelthe new technologies into emancipatoryapplications, and that could address themismatch between pervasive changes insocial relations and the institutions of anearlier era. We need to reinvent the roadto Europe.ïAn international study, to which 21 universitiesworldwide contributed, considersthe potential <strong>for</strong> new states to emergein the EU, hypothesizing a “fourth waveof independence”. Enlarging democracyin Europe – New statehoods and processesof sovereignty was presented to theEuropean Parliament on 11 January, at theinitiative of Catalan MEP Oriol Junqueras.The study suggests, among other possibilities,Scotland, Flanders, the BasqueCountry, and Catalonia — all with theirown languages, past institutions, andother relevant social & historical factors(Agence Europe, 11 January <strong>2011</strong>).

European Union and <strong>Global</strong> UnionBOOK REVIEWThe Uniting of Nations: An Essay on <strong>Global</strong> Governanceby John McClintockRonald J. GlossopOctober <strong>2011</strong>World Federalist Institute FellowRonald J. Glossop is Professor Emeritusof Philosophy and Peace Studies atSouthern Illinois University at Edwardsvilleand author of Confronting War (4thed., 2001), among other books.The Uniting of Nations: An Essay on<strong>Global</strong> Governance, by John McClintock,Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 3rd ed, 2010“Nothing like a United States of Europehas ever been built be<strong>for</strong>e, a half-billionpeople brought together not throughconquest but by the idea of “ever closerunion”. In a way it’s an inspirationalblueprint <strong>for</strong> mankind; and so it wouldbe foolish to think it would go smoothly.Yes, the League of Nations collapsed,but it did lead to the United Nations. Theeuro may also unravel but the idea istoo good not to return in <strong>for</strong>ce. Betweenthe League and the UN lay catastrophe.From here to euro 2.0 is not going to bepretty.”~ Roger Cohen, London,29 November 2010The Uniting of Nations argues <strong>for</strong> the need <strong>for</strong> a governed world community and usesthe European Union as a model <strong>for</strong> how that can be accomplished. One must start withsmall steps and proceed gradually in such a way that national governments will wantto join to gain something specific <strong>for</strong> themselves. The European Union would be thenucleus and other countries could join this global political union separately, but theywould then be required to work together to <strong>for</strong>m their own regional organizations.Thus eventually there would be a world federation made up of regional federations,one of which would be the European Union which initiated the new global organization.McClintock begins the book with a summary <strong>for</strong> those “who do not have time to readthe whole essay” (p. 17). The world faces many problems, problems which no countryby itself can solve and which can only get worse. The only way <strong>for</strong>ward is <strong>for</strong> countriesto work together. Europe is a region of the world demonstrating how nations canshare sovereignty in order to improve both their national welfare and the welfare ofthe whole group. “What Europe has done, the world needs to do. This essay explainshow” (p. 18).The many current global problems not being handled shows that “the present systemof global governance is dysfunctional” (p. 18). The basic problem is the lack ofa sovereign governing body <strong>for</strong> the whole global community which can make anden<strong>for</strong>ce laws as sovereign national governments do within countries. Just as citizensshare sovereignty in order to establish a governing body within their nations, so nationalgovernments need to share sovereignty in order to establish a governing bodyat the global level. The European Union is a good example of a governing body overnations that has both sovereign powers and political legitimacy. On the other hand, theUN’s Security Council has impressive powers on paper but not in the real world. TheUN Security Council also lacks political legitimacy because 5 countries are permanentmembers with a veto power while at any one time only 7% of the 193 countries arerepresented at all.The global community must do two things: assist the failing nation-states and “bringinto being a governing body which can act effectively at the global level” (p.23). Butthe first task itself requires “a system of global governance that works” (p. 24) andthe rules set down in the UN Charter are such that the Security Council can never bere<strong>for</strong>med. “Something new needs to be created” (p. 25). This new global organizationcould be initiated by “the European Union and around half-a-dozen or so pioneerstates” (p. 26).As was done in Europe the new global governance community could start with a fewcountries focused on a single problem like food security (p. 27) and then “a community<strong>for</strong> climate, energy, and prosperity” (p. 28). As the European Community was furtheredby the Zeitgeist of a united Europe, so the current Zeitgeist of globalism can supportthe creation of a <strong>Global</strong> Union. Perhaps future historians will see the European Unionas an experiment in sharing sovereignty by states that could be followed by the wholeworld.[continued, next page]15 • <strong>Minerva</strong> #39 • November <strong>2011</strong>