Reducing Adolescent Sexual Risk: A Theoretical - ETR Associates

Reducing Adolescent Sexual Risk: A Theoretical - ETR Associates

Reducing Adolescent Sexual Risk: A Theoretical - ETR Associates

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

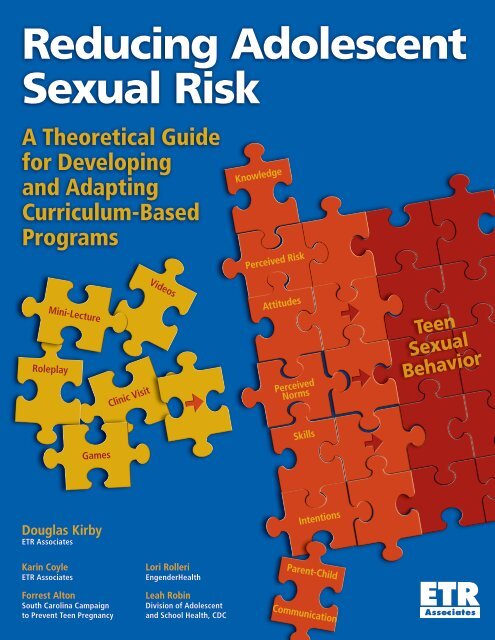

<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong><strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guidefor Developingand AdaptingCurriculum-BasedProgramsKnowledgePerceived <strong>Risk</strong>VideosMini-LectureRoleplayClinic VisitAttitudesPerceivedNormsTeen<strong>Sexual</strong>BehaviorGamesSkillsDouglas Kirby<strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>Karin Coyle<strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>Forrest AltonSouth Carolina Campaignto Prevent Teen PregnancyLori RolleriEngenderHealthLeah RobinDivision of <strong>Adolescent</strong>and School Health, CDCIntentionsParent-ChildCommunication

<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong><strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide forDeveloping and AdaptingCurriculum-Based ProgramsDouglas Kirby<strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>withKarin Coyle<strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>Forrest AltonSouth Carolina Campaign to Prevent Teen PregnancyLori RolleriEngenderHealthLeah RobinDivision of <strong>Adolescent</strong> and School Health, CDC

<strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong> (Education, Training and Research) is anonprofit organization committed to fostering the health,well-being and cultural diversity of individuals, families, schoolsand communities. The publishing program of <strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>provides books and materials that empower young people andadults with the skills to make positive health choices. Weinvite health professionals to learn more about our high-qualitypublishing, training and research programs by contacting us at4 Carbonero Way, Scotts Valley, CA 95066, 1-800-321-4407,www.etr.org.The South Carolina Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy(SC Campaign) works in all of the state’s 46 counties to preventadolescent pregnancy through education, technical assistance,public awareness, advocacy and research. Since its inceptionin 1994, the SC Campaign has established itself as the leaderand quality resource in South Carolina for comprehensive,medically accurate, age-appropriate, science-based approachesand evidence-based programs to prevent teen pregnancy.For more information, visit www.teenpregnancysc.org orwww.carolinateenhealth.org.© 2011 <strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>. All rights reserved.Published by <strong>ETR</strong> <strong>Associates</strong>4 Carbonero WayScotts Valley, California 95066Printed in the United States of America10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1Title No. A063ISBN 978-1-56071-704-1

DedicationThis volume is dedicated to Guy Parcel, Ph.D.,Professor of Health Promotion and BehavioralHealth, University of Texas School of PublicHealth, Austin Regional Campus, formerDean of the School of Public Health at theUniversity of Texas Health Science Center atHouston and former director of the Center forHealth Promotion and Prevention Research.Guy has been an incredibly productive andprolific leader in the fields of health educationand public health more generally. His manyaccomplishments include helping to develop andpromote intervention mapping, a very rigorousand systematic approach to designing effectiveprograms. In our joint work together, I learneda great deal from Guy about approaches toeffective curriculum design, as well as programevaluation and project management. Much ofthe foundation of this book was stimulated byhis approach and ideas.Douglas Kirby<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programsiii

AcknowledgmentsThis book evolved out of a series of all-day trainings thatwere jointly conceived by the South Carolina Campaign toPrevent Teen Pregnancy and myself and that I conductedover several years for the SC Campaign. Each trainingfocused on two or three risk and protective factors (and/orbackground topics) that became the basis for the chapters inthis book. I want to thank Suzan Boyd, former ExecutiveDirector of the SC Campaign; Forrest Alton, currentExecutive Director of the SC Campaign; and others at theCampaign for their intellectual, administrative and financialsupport for those trainings and, ultimately, this volume.I especially want to thank my co-authors—Karin Coyle,Forrest Alton, Lori Rolleri and Leah Robin—for theircontributions to this book. They helped conceptualize thebook, review and edit each chapter, summarize activities asexamples, arrange focus groups to review the entire volumeand obtain funding. Karin Coyle also wrote parts of twochapters and provided particularly helpful guidance on theremaining chapters. I also want to thank Lisa Romero forcreating the resource section and reviewing the volume.The book was strengthened by the reviews of numerousexperts in the field, including Bill Bacon, Patricia Dittus,Joyce Fetro, Ericka Gordon, Angie Hinzey, Chris Markam,Susan Milstein, Leslie Pridgen, Mary Prince, Nicole Ressa,Stacy Sirois and Antonia Vilarruel. Without question, thisbook benefitted from their innumerable suggestions.This book was partially supported by funding from theDivision of <strong>Adolescent</strong> and School Health, National Centerfor Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion,Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)(Contract # 200-2002-00800), and Cooperative Agreementnumber 5U65DP424971-05. The findings and conclusionsin this report are those of the authors and do not necessarilyrepresent the views of CDC.iv<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

ContentsDedication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iiiAcknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iivActivities, Boxes and Figures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . viTables . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . vii1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 Creating a Logic Model andLearning Objectives . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 93 Increasing Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 334 Improving Perceptions of <strong>Risk</strong>s—Both Susceptibility and Severity. . . . . . . . . . . 435 Addressing Attitudes, Values and Beliefs . . . . 556 Correcting Perceptions of Peer Norms . . . . . . 757 Increasing Self-Efficacy and Skills . . . . . . . . . 838 Improving Intentions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 999 Increasing Parent-ChildCommunication About Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10710 Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119Glossary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 129Resources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 143<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programsv

Activities, Boxes and FiguresActivity 4-1 Pregnancy <strong>Risk</strong> Activity and Follow-UpActivities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50Activity 4-2 STD Handshake . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52Activity 4-3 STD <strong>Risk</strong>s . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53Activity 5-1 Reasons to Not Have Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70Activity 5-2 Dreams, Goals and Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71Activity 5-3 <strong>Sexual</strong> Values Line . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 72Activity 5-4 “Dear Abby” . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73Activity 5-5 Addressing Barriers to Using Condoms . . . . . 74Activity 6-1 Conducting In-Class Surveys to ChangePerceptions of Peer Norms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82Activity 7-1 Lines That People Use to Pressure Someoneto Have Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 91Activity 7-2 Situations That May Lead to Unwantedor Unintended Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 92Activity 7-3 Roleplaying to Enhance Refusal Skills . . . . . . 94Activity 7-4 Condom Line-Up . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 96Activity 7-5 Using Condoms Correctly . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97Activity 8-1 Creating Personal <strong>Sexual</strong> Limits . . . . . . . . . . 104Activity 8-2 Creating a Plan to Stick to Their Limits . . . . 105Activity 9-1 Homework Assignment to Talk with Parents.115Activity 9-2 Relay Race for Parent-Child Programs . . . . . 116Activity 9-3 Human <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Board Game forParent-Child Programs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 117Activity 9-4 “Dear Abby” for Parent-Child Programs . . . 118Box 2-1 Tips for Developing Logic Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11Box 2-2 Criteria for Assessing Logic Models andTheir Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12Box 3-1 Types of Activities to Increase Knowledge inEffective Pregnancy and STD/HIV Prevention Curricula . . 36Box 3-2 Important Topic Areas to Cover in Pregnancy andSTD/HIV Prevention Curricula . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42Box 10-1 Potential Pilot Test Probes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 123Figure 1-1 Possible Logic Model of Psychosocial FactorsAffecting Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6Figure 2-1 Basic Elements in a Logic Model That Forms theBasis of This Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9Figure 2-2 Steps for Developing and UnderstandingLogic Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10Figure 2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to ReducePregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Disease byImplementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum . . . . . . . . . 15Figure 5-1 Peripheral Route—Central Route . . . . . . . . . . . 57Figure 10-1 Assessing Factors in Curricula . . . . . . . . . . . . 121vi<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

TablesTable 1-1 The Number of Curriculum-Based Sex EducationPrograms with Indicated Effects on <strong>Sexual</strong> Behaviors . . . . . . 4Table 1-2 The 17 Characteristics of Effective Programs . . . . 5Table 2-1 Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy of Learning—Cognitive Processing Domain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13Table 2-2 Learning Objectives to Reduce <strong>Sexual</strong> Activity . 23Table 2-3 Learning Objectives to Increase Condom Use . . 25Table 2-4 Learning Objectives to Increase HormonalContraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27Table 2-5 Learning Objectives to Increase STDVaccinations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29Table 2-6 Learning Objectives to Increase Pregnancy andSTD Testing and Treatment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30Table 3-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofKnowledge on <strong>Sexual</strong> Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Table 3-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofKnowledge on Condom or Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Table 3-3 Number of Programs Having Effects on DifferentKnowledge Topics . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35Table 4-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofPerceptions of <strong>Risk</strong>s of Pregnancy or STD/HIVon Initiation of Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45Table 4-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofPerceptions of Consequences of Pregnancy and ConcernAbout Pregnancy on Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45Table 4-3 Number of Studies Reporting Effects of OverallConcern About <strong>Risk</strong>s of STD/HIV on Condom Use . . . . . . 45Table 4-4 Number of Programs Having Effects onPerceptions of <strong>Risk</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46Table 4-5 Examples of Items That Have Been Used toMeasure Perceptions of <strong>Risk</strong> . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49Table 5-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects of AttitudesAbout Abstaining on Teens’ Own <strong>Sexual</strong> Behavior . . . . . . . . 61Table 5-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofAttitudes About Condom/Contraceptive Use on Teens’Own Condom/Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62Table 5-3 Number of Programs Having Effects onAttitudes Toward Sex and Condom/Contraceptive Use . . . . 63Table 5-4 Examples of Survey Items from Research Studiesof Attitudes, Values and Beliefs in Different Domains . . . . . 67Table 6-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofPeer Norms About Sex on Teens’ Own <strong>Sexual</strong> Behavior . . . . 77Table 6-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofPeer Norms About Condom/Contraceptive Use onTeens’ Own Condom/Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 77Table 6-3 Number of Programs Having Effects onPerceptions of Peer Norms or Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78Table 6-4 Examples of Items That Have Been Used toMeasure Perceptions of Peer Norms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 81Table 7-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofSelf-Efficacy to Refrain from Sex on Teens’ Own<strong>Sexual</strong> Behavior . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Table 7-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofSelf-Efficacy to Insist on Condom/Contraceptive Use onTeens’ Own Condom/Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 85Table 7-3 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofSelf-Efficacy to Actually Use Condoms or Contraceptiveson Teens’ Own Condom or Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . 86Table 7-4 Number of Programs Having Effects onSelf-Efficacy and Skills to Perform Protective Behaviors . . . 86Table 7-5 Examples of Items That Have Been Usedto Measure Self-Efficacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 89Table 8-1 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofIntentions on Initiation of Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101Table 8-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofIntentions on Condom or Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . 101Table 8-3 Number of Programs Having Effectson Intentions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101Table 8-4 Examples of Items That Have Been Usedto Measure Intentions to Have Sex or Use Condoms orContraception . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102Table 9-1 Number of Studies Reporting an AssociationBetween Parent-Child Communication About Sexand Teens’ Initiation of Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109Table 9-2 Number of Studies Reporting Effects ofParent-Child Communication About Sex on Teens’Subsequent Initiation of Sex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109Table 9-3 Number of Studies Reporting Effectsof Parent-Child Communication About Sex onTeens’ Condom or Other Contraceptive Use . . . . . . . . . . . . 109Table 9-4 Number of Programs for Teens HavingEffects on Parent-Child Communication About Sex . . . . . 111Table 9-5 Number of Programs for Parents andTeens Having Effects on Parent-Child CommunicationAbout Sex and Teen <strong>Sexual</strong> Behavior. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 111Table 9-6 Number of Programs for Only Parents HavingEffects on Parent-Child Communication About Sex . . . . . 113Table 9-7 Examples of Items That Have Been Used toMeasure Parent-Child Communication About <strong>Sexual</strong>ity . . 114Table 10-1 Instructional Principles Importantfor Each Factor . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 125<strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programsvii

1 IntroductionThis book was created tohelp others design or adapttheir own curricula.Overview of This BookUnintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases(STDs), including HIV, continue to be importantproblems among young people in the UnitedStates. These problems can be addressed effectively ifyoung people reduce their sexual risk behaviors—forexample, if they initiate sexual activity later, havesex (meaning vaginal, anal and oral sexual activity)less frequently, have fewer sexual partners anduse condoms or contraception more consistently.However, programs designed to address unintendedpregnancy and STDs cannot directly control thesexual risk behavior of young people; rather, theycan only affect various risk and protective factorsthat, in turn, affect decision making and behavioramong young people.<strong>Risk</strong> and protective factors include biological factorssuch as age or maturation, community factors suchas economic opportunities or crime rates, and familyfactors such as strong families and monitoring ofchildren.However, a very important group of risk and protectivefactors is “sexual psychosocial” factors. Theseinclude knowledge, perceptions of risk, attitudes,perceptions of norms, self-efficacy and intentions.These are particularly important because 1) theyhave a very strong impact on sexual decision makingand behavior and 2) educational programs, eitherin school or out of school, can significantly improveeach of them, if curricula include the right kinds ofactivities that incorporate important instructionalprinciples.Although it is relatively easy to increase knowledge,it is not easy to markedly improve all ofthese factors. If curriculum activities fail to includeimportant instructional principles, they may fail toimprove these factors and may fail to have an impacton behavior. On the other hand, there is considerableevidence that all of these factors are amenableto change when appropriate instructional techniquesare used. Thus, these principles are important toachieve behavior change.This book is not a curriculum itself. Instead, it isdesigned to help reproductive health professionals,educators, curricula selection committees and othersdesign or adapt curricula so that they focus on riskand protective factors that are related to sexual riskbehavior and use instructional principles most likelyto improve the targeted factors. It can also be usedto select curricula that incorporate these features,Chapter 1 Introduction 1

ut it does not focus on other important criteria forselecting curricula.We have structured the book around risk andprotective factors most likely to be changed by acurriculum-based program. Each chapter focuseson a different risk or protective factor, summarizingthe available evidence showing that the factor affectssexual behavior and discussing relevant behaviorchange theory and important instructional principlesfor improving the factor.Although most of the examples in this book comefrom activities used primarily with middle or highschool-aged youth, it also can be useful for peopledesigning curricula for younger or older youth.Finally, even though all the examples involve sexuality,the risk and protective factors, the theories andthe pedagogical principles may apply to many healthbehaviors other than sexual risk, such as eatingnutritiously, exercising and preventing substanceabuse. However, theories and research on the factorsaffecting these other behaviors should be thoroughlyreviewed before applying the instructional principlesdiscussed.<strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong> Behaviorand Its ConsequencesIn the United States, young people engage in considerablesexual risk behavior prior to or outside ofmarriage. For example:• Roughly half of all high school students reporthaving had sex at least once and close to twothirdsreport having sex before they graduatefrom high school (Centers for Disease Controland Prevention 2010b).• Although 80 to 90 percent of teens report usingcontraception during their most recent act ofsexual intercourse, many teenagers do not usecontraceptives correctly and consistently. Among15- to 19-year-old women relying upon oral contraceptives,only 70 percent take a pill every day(Abma et al. 1997). Among never-married men15-19 who had sex in the previous year, only47 percent used a condom every time they had sexin that year (Abma 2004).As a result, pregnancy rates and birth rates amongU.S. young adults remain very high relative to otherdeveloped countries.• In 2004, the latest year for which data are published,the rate of unplanned pregnancy was highestamong women 18-19 and 20-24 years of age.In these age groups, more than one unplannedpregnancy occurred for every 10 women, a ratetwice that for women overall (Finer and Henshaw2006; Ventura, Abma et al. 2008).• Among 15- to 19-year-old teens, about 72 ofevery 1,000 women became pregnant in 2006(the last year for which data are available)(Guttmacher Institute 2010). This means thatcumulatively, more than 30 percent of teenagewomen in the United States became pregnant atleast once by the age of 20.• These rates were much higher for Hispanics(127 per 1,000 women) and blacks (126 per1,000 women) than for non-Hispanic whites(44 per 1,000 women).• In absolute numbers, about 750,000 womenunder age 20 become pregnant each year(Guttmacher Institute 2010).• More than 80 percent of these pregnancies areunplanned (Finer and Henshaw 2006).• Among young women ages 20-24, each year1.7 million pregnancies occur, 58 percent ofwhich are unplanned. Among unmarried women20-24, 72 percent of their pregnancies areunplanned (Connor 2008).These unintended pregnancies have negative effectson the young adults involved, their children andsociety at large.• Teenage mothers are less likely to completeschool, less likely to go to college, more likely tohave large families and more likely to be singlethan their peers who are not teenage mothers,increasing the likelihood that they and their childrenwill live in poverty. Negative consequencesare particularly severe for younger mothers andtheir children (Hoffman 2006).2 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

• Children of teenage mothers are likely to haveless supportive and stimulating home environments,lower cognitive development, less education,more behavior problems and higher ratesof both incarceration (for boys) and adolescentchildbearing than children of non-teenage mothers(Hoffman 2006).STDs are also a large problem. Compared to olderadults, sexually active adolescents and young adultsages 24 and younger are at higher risk for acquiringSTDs. For example:• The most common STDs among young peopleare human papillomavirus (HPV), trichomoniasisand chlamydia. Although young adults (24 andunder) represent only 25% of the sexually activepopulation, they account for nearly half (48 percent)of the new STD cases every year. In 2004,there were more than nine million cases of STDreported in this age group (Weinstock, Berman etal. 2004).• In addition, more than 7,000 young adults 24 andunder were diagnosed with HIV in 2008 (Centersfor Disease Control and Prevention 2010a).• The prevalence of STDs are typically muchhigher among African-American young peoplethan non-Hispanic whites (Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention 2008a). In 2006,for example, the rates of gonorrhea amongAfrican-American 15- to 19-year-old womenwere 15 times greater than those for white womenin the same age group. The rate for African-American men ages 15-19 was 39 times higherthan for 15- to 19-year-old white men (Centersfor Disease Control and Prevention 2008).Impact of Curriculum-BasedSex and STD/HIV EducationProgramsIn response to these high rates of unintended pregnancyand STDs, many people concerned aboutadolescent reproductive health have implementeda wide variety of programs to reduce sexual risk.Aside from contraceptive services, STD testing andtreatment and other reproductive health servicesprovided in clinics, the most commonly implementedtypes of prevention programs are curriculum-basedsex and STD/HIV education programs.These programs are based on a written curriculumand are implemented among groups of youth. Theyare in contrast to one-on-one peer programs; healthfairs; youth development programs and other kindsof programs that also have an impact on adolescentsexual behavior. They are commonly implemented inschools where very large numbers of young peoplecan be reached before and after they have initiatedsexual activity. However, curriculum-based sexand STD/HIV education programs also have beenimplemented effectively after school and in nonschoolsettings such as clinics, community centers,housing projects and elsewhere.Multiple reviews of sex and STD/HIV educationprograms have been conducted in the United Statesand elsewhere (Johnson, Carey et al. 2003; Robin,Dittus et al. 2004; Kirby 2007; Underhill, Operarioet al. 2007, UNESCO 2009). They consistently supportthe following conclusions (see Table 1-1):1. Sex and STD/HIV education programs do notincrease sexual behavior, even when they encouragesexually active young people to use condomsor other forms of contraception.2. Some programs delay the onset of sexual intercourse,reduce the frequency of sex, reduce thenumber of sexual partners, increase condom use,increase other contraceptive use, and/or reducesexual risk.3. Not all programs are effective at changingbehavior. According to one review (Kirby 2008),about two-thirds of the programs had a positivesignificant impact on one or more sexual behaviorsamong the entire sample or among importantsub-groups within the sample (e.g., males orfemales). About one-third did not. And one-thirdof the programs improved two or more behaviors;the remainder did not.4. Numerous characteristics distinguish theeffective programs from the ineffective ones(Kirby 2007). For example, the effective programsChapter 1 Introduction 3

used psychological theory and research to identifythe cognitive risk and protective factors that affectbehavior and then developed program activities tochange those factors, gave clear messages aboutbehavior and taught skills to avoid undesired andunprotected sexual activity. Table 1-2 lists all thedistinguishing characteristics.5. Some programs for parents also have been foundto be effective at increasing communicationbetween parents and their adolescents and atreducing adolescent sexual risk behavior(Kirby 2007).Identifying and ImprovingImportant <strong>Risk</strong> andProtective FactorsAs stated above, curriculum-based sex andSTD/HIV programs, as well as other programs,cannot directly control whether young peopleengage in sexual activity or whether they useprotection; instead, young people make their owndecisions about sexual behavior and use of protection.Thus, to be effective, programs must markedlyimprove those risk and protective factors that havean important impact on youths’ decision makingabout sexual behavior.Logically, if programs correctly identify the factorsthat have a clear impact on behavior and if programactivities markedly change those factors, then theprogram will have an impact on behavior. However,if programs identify factors that only weakly affectbehavior or fail to change the factors sufficiently,then they may not affect behavior. Consequently,it is critical both to identify the important factorsaffecting behavior and to implement programsdesigned to change those factors.Factors that have a large impact on behavior includeinternal cognitive factors (such as knowledge, attitudes,skills and intentions) and external factors suchas access to adolescent-friendly reproductive healthservices. Curriculum-based programs, especiallythose in schools, typically focus on internal cognitivefactors. These factors are very proximal (closelyTable1-1The Number of Curriculum-Based SexEducation Programs with IndicatedEffects on <strong>Sexual</strong> BehaviorsUnitedStates(N=47)OtherDevelopedCountries(N=11)DevelopingCountries(N=29)AllCountriesin the World(N=87)Initiation of Sex➤ Delayed initiation 15 2 6 23➤ Had no significant impact 17 7 16 40➤ Hastened initiation 0 0 0 0Frequency of Sex➤ Decreased frequency 6 0 4 10➤ Had no significant impact 15 1 5 21➤ Increased frequency 0 1 0 1Number of Sex Partners➤ Decreased number 11 0 5 16➤ Had no significant impact 12 0 8 20➤ Increased number 0 0 0 0Use of Condoms➤ Increased use 14 2 7 23➤ Had no significant impact 17 4 14 35➤ Decreased use 0 0 0 0Use of Contraception➤ Increased use 4 1 1 6➤ Had no significant impact 4 1 3 8➤ Decreased use 1 0 0 1<strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>-Taking➤ Reduced risk 15 0 1 16➤ Had no significant impact 9 1 3 13➤ Increased risk 0 0 1 1linked to behavior conceptually) and are related tobehavior.Previous studies of curriculum-based sex and STD/HIV education programs have demonstrated thatthose programs that effectively delayed the initiationof sex, reduced the frequency of sex, or reduced thenumber of sexual partners sometimes focused onand improved the following cognitive factors (Kirby2007):1. Knowledge, including knowledge of sexual issues,pregnancy, HIV and other STDs (includingmethods of prevention)2. Perception of pregnancy risk, HIV risk, and otherSTD risk3. Personal values about sexuality and abstinence4. Perception of peer norms and behavior about sex5. Self-efficacy to refuse sexual activity and to usecondoms and contraception4 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Table1-2 The 17 Characteristics of Effective Programs*The Process of Developingthe CurriculumThe Contents of the Curriculum ItselfThe Process of Implementingthe Curriculum1.Involved multiple peoplewith different backgroundsin theory, research and sexand STD/HIV education todevelop the curriculum2. Assessed relevant needs andassets of target group3. Used a logic model approachto develop the curriculumthat specified the healthgoals, the behaviors affectingthose health goals, therisk and protective factorsaffecting those behaviorsand the activities addressingthose risk and protectivefactors4. Designed activities consistentwith community valuesand available resources (e.g.,staff time, staff skills, facilityspace and supplies)5. Pilot-tested the program*Curriculum Goals and Objectives16. Focused on clear health goals—the prevention ofpregnancy and/or STD/HIV17. Focused narrowly on specific behaviors leading to thesehealth goals (e.g., abstaining from sex or using condomsor other contraceptives), gave clear messages aboutthese behaviors and addressed situations that mightlead to them and how to avoid them18. Addressed multiple sexual psychosocial risk and protectivefactors affecting sexual behavior (e.g., knowledge,perceived risks, values, attitudes, perceived norms andself-efficacy)Activities and Teaching Methodologies19. Created a safe social environment for youth toparticipate10. Included multiple activities to change each of thetargeted risk and protective factors11. Employed instructionally sound teaching methods thatactively involved the participants, that helped participantspersonalize the information and that weredesigned to change each group of risk and protectivefactors12. Employed activities, instructional methods and behavioralmessages that were appropriate to the youths’culture, developmental age and sexual experience13. Covered topics in a logical sequence14. Secured at least minimalsupport from appropriateauthorities such as departmentsof health, schooldistricts or communityorganizations15. Selected educators withdesired characteristics(whenever possible),trained them and providedmonitoring, supervisionand support16. If needed, implementedactivities to recruit andretain youth and overcomebarriers to their involvement,e.g., publicized theprogram, offered food orobtained consent17. Implemented virtually allactivities with reasonablefidelityKirby, D. B. (2007). Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseases.Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unwanted Pregnancy.6. Intention to abstain from sexual activity, restrictsexual activity or decrease the number of sexualpartners7. Communication with parents or other adultsabout sexuality, condoms or contraception1Similarly, those programs that effectively increasedcondom or contraceptive use sometimes focused onand improved the following factors (Kirby 2007):1. Knowledge, including knowledge of sexual issues,pregnancy, HIV and other STDs (includingmethods of prevention)1 Communication with parents or other adults is not a cognitivesexual psychosocial factor. However, it is a factor that many programsaddressed and improved and that in turn changed behavior.2. Attitudes toward risky sexual behavior andprotection3. Attitudes toward condoms4. Perceived effectiveness of condoms to preventSTD/HIV5. Perceptions of barriers to condom use6. Self-efficacy to obtain condoms7. Self-efficacy to use condoms8. Intention to use a condom9. Communication with parents or other adultsabout sex, condoms, or contraceptionBoth theory and numerous empirical studies havedemonstrated that these factors, in turn, have animpact on adolescent sexual decision making andChapter 1 Introduction 5

ehavior (Kirby and Lepore 2007). These factors areamong the most important concepts in widely usedeffective psychosocial theories of health behaviorchange, such as social cognitive theory, theory ofreasoned action, theory of planned behavior, andthe information-motivation-behavioral skills model(Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Ajzen 1985; Bandura1986; Fisher and Fisher 1992).In sum, there is considerable evidence that effectivesex and STD/HIV education programs actuallychanged behavior by first having an impact on thesefactors, which, in turn, positively affected youngpeople’s sexual behavior.Although there is evidence that all of these factorsaffect behavior, some of them affect each otherand only indirectly affect behavior. For example,it is commonly believed that intentions to performa behavior most directly affect that behavior. Inturn, relevant attitudes, perceptions of norms andself-efficacy affect intentions. Further, other factors(e.g., knowledge) may affect attitudes, perceptionsof norms and self-efficacy. Figure 1-1 provides anexample of how these factors may be related.Finally, although intentions to perform a behaviortend to be good predictors of whether or notthe behavior is then performed, many things candisrupt (or moderate) the intention–behavior link.For example, environmental constraints or habitsmay affect whether intentions translate into behavior,so even intentions do not completely determinebehavior.Organization of This BookThe organization of this book follows the frameworkof logic models, which are described in greater detailin Chapter 2.The primary health goals addressed in this bookare to reduce unintended pregnancy and STDs. Toreduce unintended pregnancy, young people need todelay sex or reduce the frequency of sex and increasethe consistent and correct use of effective contraception.To reduce STD transmission, young peopleneed to delay sexual activity, have sex less frequently,have fewer sexual partners, avoid concurrent sexualpartners, increase condom use, increase the timeperiod between sexual partners, be tested (andtreated if necessary) for STDs and be vaccinatedagainst human papilloma virus (HPV) and hepatitisB (Kirby 2007). Logic models for some of thesebehaviors are presented in the next chapter.Figure1-1Possible Logic Model of Psychosocial Factors Affecting BehaviorEnvironmentKey <strong>Risk</strong> and Protective Factors(<strong>Sexual</strong> Psychological Factors)<strong>Sexual</strong> BehaviorsHealth GoalsSex andSTD/HIVEducationParent-childcommunicationSupport fromenvironmentPerceptionof riskKnowledgeActualbehavioralcontrol(self-efficacy)AttitudestowardbehaviorsPerceivednormsPerceivedbehavioralcontrol(self-efficacy)Strength ofintention toperform eachsexual behavior• Delay onset of sex• Decreasefrequency of sex• Decrease numberof partners• Avoid concurrentpartners• Increase timebetween partners• Increase use ofcondoms or birthcontrol• Increase STDtesting andtreatmentDecreaserates of teenpregnancy,STD and HIV6 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Each of the following chapters focuses on an importantrisk and protective factor that affects thosebehaviors and can be changed by curriculum-basedsex and STD/HIV education programs. Withineach chapter, we:• Identify a risk or protective factor that has animpact on these sexual risk behaviors• Identify important theories that address eachfactor• Summarize the evidence for the impact of thatfactor on the sexual behaviors 2• Summarize the evidence for the ability of programsto change the factor3• Specify important instructional principles foreffectively changing each factor• Summarize examples of activities that have beenused in curricula that effectively changed eachfactor• Provide references to more detailed descriptionsof those activities in effective curricula• Provide a sampling of items used in studies tomeasure each factor (These items simply providemore detail about some of the concepts in eachfactor.)Consequently, this book can be used to help developcompletely new curricula, to add new activities toexisting curricula that may not have sufficientlypowerful activities to change particular factors,to improve the effectiveness of existing activitiesalready in curricula and to critically review curriculaactivities for possible adoption. When adaptingcurricula that have strong evidence of impact,all changes should be consistent with guidelinesfor adapting those curricula (Rolleri, Fuller et al.,unpublished).Reading this book from cover to cover may be challenging.Thus, readers may wish to:1. Read the first two chapters to obtain an overviewof the book, logic models and behavioralobjectives.2. Read and apply those chapters addressing thespecific factors that are in their own logic models.3. Read the final chapter and apply the principles totheir curricula.2 In each chapter, the evidence assessing the relationship betweenthe factor discussed in that chapter and sexual behavior is based ontabulations of the studies summarized in <strong>Sexual</strong> risk and protectivefactors: Factors affecting teen sexual behavior, pregnancy, childbearing andsexually transmitted disease: Which are important? Which can you change?(Kirby and Lepore 2007).3 In each chapter, the evidence assessing the impact of curriculumbasedprograms on the factor discussed in the chapter is based largelyon tables in Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs toreduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (Kirby 2007).Chapter 1 Introduction 7

2Creatinga Logic Modeland Learning ObjectivesKeys to Creating a Logic ModelComplete the following four steps in order: Identify 1) thehealth goal(s) to be achieved; 2) the behaviors that directlyaffect that health goal(s); 3) the factors that affect eachof those behaviors and that can be modified; and 4) theintervention components or activities that will improve thosefactors.Keys to Creating LearningObjectivesIdentify the precise behaviors to be implemented to avoidunprotected sexual activity and the particular knowledge,facts, beliefs, attitudes, peer norms and skills needed tohave the intentions and ability to conduct those behaviors.BackgroundMost, if not all, programs that have led to sexualbehavior change have either explicitly or implicitlydeveloped logic models. Their development is one ofthe 17 characteristics of effective curriculum-basedsex education programs. Creating a detailed logicmodel is a very important first step in the processof creating a new program or improving or adaptingan existing program. It provides the frameworkor roadmap specifying which activities affect whichfactors that, in turn, change behavior and achievehealth goals.A foundation of this book is a particular logic modelthat assumes that specific curriculum activities canaffect selected sexual psychosocial factors that, inturn, reduce sexual risk behavior and potentiallyreduce unintended pregnancy and STDs (see Figure2-1). This chapter briefly describes a process forcreating logic models and provides a very detailedexample of one logic model that is consistent withthe subsequent chapters in this book and the manyprinciples therein.This chapter continues with a discussion of learningobjectives, because a critical step in developingcurriculum-based intervention activities is creatinglearning objectives to focus the instruction andensure it will produce learning that is related to thebehavioral goals specified in the logic model.Types of Logic ModelsAlthough many logic models include these fourcomponents, they sometimes use different wordsto describe them. Some may use the conceptsabove, while others may refer to “interventions,”Figure2-1Basic Elements in a Logic Model That Forms the Basis of This BookSpecifiedCurriculumActivitiesAffectChosen <strong>Risk</strong> andProtective FactorsThatAffectImportant<strong>Sexual</strong> BehaviorsWhich,in Turn,ReduceTeen Pregnancy,STD and HIVChapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 9

“determinants,” “behaviors,” and “health goals,”or “activities,” “short-term objectives” and “longtermoutcomes,” or “processes,” “outcomes,” and“impacts,” respectively.There are also other variations among logic models.Some include only these four minimum components,while others may provide more informationon inputs or specify far more complex causal models,with some determinants of behavior affecting otherdeterminants or with reciprocal causality acknowledged(e.g., determinants affecting behaviors andvice versa).Steps for Developinga Logic ModelCreating a logic model consistent with the goalsof this book involves completing at least four basicsteps:1. Identify possible health goals and select thehealth goal(s) to be achieved. For the purposesof this book, those health goals are reducingunintended pregnancy and STDs among youngpeople. These are listed on the far right side of thelogic model (see Figure 2-1).2. Identify potentially important behaviors thataffect the selected health goal and then select theparticular behaviors to be targeted. Key behaviorsfor sexual risk-taking are specified in Chapter 1.Specifically, to reduce unwanted pregnancy,young people need to delay sex or reduce the frequencyof sex and increase consistent and correctuse of effective contraception. To reduce STDtransmission, young people need to delay sex,have sex less frequently, have fewer sexual partners,avoid concurrent sexual partners, increasecondom use, increase the time period betweensexual partners, be tested (and treated if necessary)for STDs and be vaccinated against HPVand hepatitis B.3. Identify potentially important risk and protectivefactors of the selected behaviors and selectthose factors that can be changed and are to betargeted. This book highlights selected sexualpsychosocial factors affecting sexual behavior andparent-child communication about sexual behavior.Multiple studies demonstrate that these factorscan be changed by curriculum-based activitiesand can, in turn, affect sexual risk behavior.4. Identify or create possible interventions or activitiesthat have sufficient strength to improve eachselected risk and protective factor and select thosethat are most effective. The following chaptersprovide examples of many effective activities anddescribe theory-based instructional practices forincreasing their effectiveness.These four steps are summarized in Figure 2-2.Box 2-1 provides additional tips for developinglogic models, and Box 2-2 provides criteria forFigure2-2Steps for Developing and Understanding Logic ModelsThe order of the steps for developing the logic model:Step 4 Identify andselect interventioncomponentsStep 3 Identify andselect importantrisk and protectivefactorsStep 2 Identify andselect importantbehaviorsStep 1 Identify andselect healthgoal(s)The causal order of the components of the completed logic model:SpecifiedInterventionComponentsand ActivitiesAffectChosen <strong>Risk</strong> andProtective FactorsThatAffectImportant<strong>Sexual</strong> BehaviorsWhich,in Turn,ReduceTeen Pregnancy,STD and HIV10 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

assessing logic models. Logic models are describedmuch more fully in Kirby (2004). An on-linecourse on these models also is available free ofcharge at: http://www.etr.org/recapp/documents/logicmodelcourse/index.htm. Intervention Mapping(Bartholomew, Parcel et al. 2006) describes morecomprehensive approaches that involve logic modelsand that are effective.A Detailed Example ofa Logic ModelFigure 2-3 provides a very detailed example of alogic model that incorporates activities from curriculathat have been effective at improving sexualpsychosocial factors and behavior. The figure illustrateshow to read a logic model and how a givencurriculum would reduce sexual risk behaviors. Italso provides a frame of reference for the remainderof this book. Indeed, Chapters 3 to 9 focus onthe risk and protective factors that are in this logicBox2-1 Tips for Developing Logic Models• Choose your target. Remember that logic models aregraphic depictions that show clearly and concisely thecausal steps through which specific interventions canaffect behavior and thereby achieve a health goal.They can be applied to any health goal or to any goalthat is affected by the behavior of individuals or thepolicies and programs of organizations.• Be comprehensive. Consider all reasonable possibilitiesat each stage, all health goals of interest, all behaviorsaffecting a selected health goal, all factors affectingeach behavior, and all activities or interventions thatmay affect each factor.• Be thorough. Consider both positive and negativebehaviors and both risk and protective factors thataffect those behaviors.• Be strategic. Focus on the goals, behaviors, risk andprotective factors, and intervention strategies that aremost important and that you can change; the mostimportant health goal in the community that yourorganization wishes to achieve (and can), the mostimportant behaviors that have the greatest impact onthat health goal and that you can change, the mostimportant factors that affect each behavior and thatyou can change, and the activities or interventionsthat most strongly affect each factor and that you canimplement.• Be realistic. Assess the impact of each activity or interventionon each factor, the impact of each factor oneach behavior and the impact of each behavior on thehealth goal. Select only those that have the greatestimpact.• Consider the evidence. Review research when assessingwhich activities, risk and protective factors andbehaviors are most important in addressing a healthgoal.• Be very specific. For example, when choosing a healthgoal, specify the particular health outcome and thepopulation to be targeted (e.g., a particular agegroup in a particular geographic area). When choosingbehaviors, identify the specific behavior, not abroader behavior. (For example, do not specify “reducingunprotected sex” as a behavior. Instead, break itdown into abstaining, using condoms, having mutuallymonogamous partners, using contraception, etc.)When choosing activities, describe them sufficiently sothat readers can understand how they will affect theirtargeted factors.• Call for back-up. Identify multiple activities to changeeach important risk or protective factor. (Create amatrix to help with this as described in Chapter 10.)• Know your target. Complete all of these activities witha thorough knowledge of the particular population ofyoung people, their community, their culture and theircharacteristics always in mind.• Widen your perspective. Involve multiple people inthe development of your logic model. Include peoplewith different areas of expertise, such as knowledgeabout adolescent sexual behavior, psychosocialtheories of behavior change, factors affecting sexualbehavior, effective instructional strategies, youth culture,community values and research on sex educationprograms.• Use the logic model as a tool. Use your logic modelnot only to develop an effective program, but toexplain it to other stakeholders and to train staff whoimplement it.• Monitor progress. Over time, conduct evaluations toassess your logic model and program, using the datato update and improve them.Chapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 11

model, provide evidence regarding how these riskand protective factors affect behavior, provide evidencethat curriculum activities can improve themand describe the theory behind these psychosocialfactors, as well as the instructional principles forshaping curriculum activities to improve them.Learning Objectives:Becoming More SpecificAfter creating a logic model, the next important stepin developing curriculum-based intervention activitiesis creating learning objectives. The elements inlearning objectives are typically more precise thanthose in logic models and therefore further focus theinstruction. If prepared properly, these objectivesshould convey what students will be able to do as aresult of the lesson(s).Box2-2 Criteria for Assessing Logic Models and Their Development 4Criteria for Assessing the Model• Can the selected factors be modified markedly bypotential interventions?Overall• Are all factors that affect behavior and can be• Does the model make sense? Do the goals, behaviors,risk and protective factors and interventionchanged by feasible interventions included?approaches reflect the understanding of the group?Program Components• Are all items in the correct columns?• Can the activities and components in combinationhave a marked impact upon each of the selected• Are all the relationships causal (as opposed to correlational)?factors? Do multiple activities or components addresseach factor?Goals• Is there strong evidence from research or elsewhere• Is the stated goal a priority?that the intervention strategies can improve the• Is it well defined?factors?• Are the populations defined well enough (e.g., by age, • Is it feasible to implement each of the interventionsex, income level, location)?components? Are the necessary organizational• Does your organization have the capacity to addressrequirements in place? Do staff have the neededthis goal?skills? Are there sufficient financial resources? Is therenecessary political or policy support? Is there sufficientBehaviorscommunity support?• Are all the important and relevant behaviors that have• Given the purposes of the model, were the interventioncomponents described in sufficient detail?a marked impact upon the health goal identified andselected? If not, are there good reasons provided forexcluding some of the behaviors?Criteria for Assessing the Development of• Are the behaviors defined precisely?the Model• Do they directly and strongly affect the health goal?• Were people with different views involved in the• Are they measurable?development of the model? Were youth involved in<strong>Risk</strong> and Protective Factorsthe development of the model? Were people with programexperience involved? Were researchers involved?• Were risk and protective factors in different domainsidentified (e.g., media, community, school, family,• Is a process described for actually using the modelpeer, and individual)? If not, were good reasonsonce it is developed (e.g., using it to create a curriculum,train educators, inform stakeholders or facilitateprovided for excluding some of the factors?• Are both risk and protective factors included?grant writing)?• Do selected factors have a strong causal impact upon• Is a process described for periodically assessing andone or more behaviors?updating the model?4 These are criteria for assessing logic models in general, not only logic models specifically designed for curriculum-based programs.12 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

For example, not having sex at a particular time orwith a particular person may involve: deciding notto have sex, communicating personal limits aboutsex, suggesting alternative activities to sex, avoidingsituations that might lead to sex and refusing to havesex. Similarly, using condoms may involve: makingthe decision to use condoms, buying or obtainingcondoms, carrying condoms, negotiating their useand using condoms.Associated with each of these more specific behaviorsare multiple learning objectives that will affectstudents’ intention and ability to perform thesebehaviors. Because there are learning objectivesassociated with each of the sexual psychosocial factorsdiscussed in the following chapters, examplesof learning objectives are presented in a matrix withthe specific behaviors down the left-hand side andthe psychosexual factors across the top. (See Tables2-2 to 2-6.)Taxonomies of learning (Bloom, Englehatt et al.1956; Krathwohl, Bloom et al. 1964; Anderson andKrathwohl 2001) are among the most well-usedtools to help shape objectives and reflect a continuumof learning ranging from lower levels (e.g.,remembering key facts) to actually synthesizing andconstructing new learning. There are taxonomies forthe cognitive, affective, and psychomotor domains,descriptions of which are available on the Internet.These taxonomies also have lists of “learning verbs”associated with each level to help developers shapeobjectives. (See examples for the cognitive processingdomain in Table 2-1.) Ideally, students shouldbe challenged to reach higher levels of learning (e.g.,applying, analyzing, evaluating or creating) ratherthan just recalling information. Indeed, researchhas shown that students who work with content athigher levels of a taxonomy retain more than thoseworking only at lower levels (Garavalia, Hummel etal. 1999). For example, students who learn strategiesTable2-1 Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy of Learning—Cognitive Processing Domain *LowerLevelRevisedTaxonomyLevelBrief Decription of Level*Examples of Learning VerbsExamples of Behavioral ObjectivesRememberRecall facts or bits ofinformationList, memorize, identify,cite, recallStudents will be able to list 5 factsabout HIV transmission.UnderstandConstruct meaning from theinformation rememberedExplain, describe, illustrate,clarify, restate, discussStudents will be able to describe howcondoms protect against HIV.ApplyUse the information in agiven situationApply, use, demonstrate,show, practiceStudents will be able to use refusalskills correctly when faced withpressure to have sex.AnalyzeBreak material into smallerparts and see how the partsrelate to each other and thebigger pictureAnalyze, examine, compare,contrast, debate, appraiseStudents will be able to compareand contrast the pros and cons ofhaving sex.EvaluateMake judgments based onthe informationEvaluate, judge, decide,appraise, recommendStudents will be able to decide onthe most effective form of protection(abstinence and contraception) for3 pairs of students in relationships.HigherLevelCreateSynthesize the information andput it together to apply it in anew wayCreate, design, construct,present, compose, hypothesize,generate* Note: Details regarding the revised taxonomy can be found in Anderson and Krathwohl 2001.Students will be able to composea response to an anonymous callerseeking advice on what to do aboutsome STD symptoms he/she isexperiencing.Chapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 13

to avoid unwanted sex and then synthesize themand apply them to other situations will rememberand use them more than those students who simplyreiterate the strategies.Once the learning objectives have been established,it is essential to ensure the planned activities and theobjectives are in alignment. If an activity is includedin the curriculum but really does not support studentsin meeting the stated objectives, then it shouldbe modified or replaced. If an existing program doesnot have clearly stated objectives, they should becreated.Tables 2-2 to 2-6 include examples of behavioralobjectives for the key behaviors specified in the logicmodel in Figure 2-3. These tables are not exhaustive,but provide a range of examples of the types ofobjectives that could be included in a curriculum toaddress abstinence, sexual partners, contraceptiveuse, condom use, STD testing and treatment, andvaccinations.14 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education CurriculumIndividual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Provide accurate information about the risks of pregnancy• Implement simulation activities in which teens see that with each passing month,more teens get pregnant if they have unprotected sex, but don’t get pregnant ifthey abstain• Have students write down what they would have to do in the next 48 hours if theyjust found out they were pregnant• Have students write down activities they wish to do in coming years, and then markwhich ones would be difficult or impossible if they had a child• Show video clips of teen parents who talk about how they wish they had waiteduntil they were older to become parents• Provide accurate information about the risks of STDs (including HIV)• Implement simulation activities in which adolescents can see how STDs can spreadrapidly in people engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners• Show video clips of teens who contracted herpes or other incurable STDs and whodescribe the consequencesIncrease knowledge andperception of risks andconsequences of pregnancy andchildbearing if sexually activeIncrease knowledge andperception of risks andconsequences of contracting anSTD, including HIV, if sexuallyactive• Delay initiation ofsex• Reduce frequencyof sex amongsexually active• Reduce number ofpartners• Avoid concurrentpartners• Increase timebetween partners• Have only longterm,mutuallyfaithful partners ifhaving sex• Reduce teenpregnancy• Reduce STD• Provide accurate information about the additional risks of having multiple partners,concurrent partners and short periods of time between partners• Implement simulations showing the huge impact on the size of sexual networks ofsmall increases in number of partners• Conduct simulations demonstrating the impact of concurrent versus sequentialsexual partners on the spread of STDsIncrease knowledge and perceptionof risks of the impactof multiple partners, concurrentpartners, and gap of timebetween sexual partners on contractingan STD, including HIV• Have peer leaders lead group discussions in which students discuss the advantagesand disadvantages of engaging in sex, and emphasize benefits of abstaining fromsex or having only one long term faithful partner if having sex• Identify peers who are popular among different groups of adolescents and whoare willing to publicly support abstinence or having only one long-term, faithfulpartner if having sex• Have groups of peers plan and implement school-wide activities such as assemblies,contests, media materials and small group discussions, all of which promoteavoiding unprotected sex by abstaining from sex• Conduct school-wide polls and report results showing support for adolescentsavoiding unprotected sex; provide individual stories to personalize results of thepolls• Collect survey data from students and report results showing that most studentsabstain from sex or support only one long-term, faithful partner if having sex• Implement roleplays in which adolescents successfully resist sexIncrease perception that peersare not sexually active andsupport abstinence or long‐termfaithful partners(Continued)Chapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 15

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Lead group discussions in which students discuss the advantages and disadvantagesof engaging in sex; emphasize that abstinence is the only 100% effective methodof avoiding pregnancy and STD, and may reduce some emotional negativeoutcomes; and emphasize that some advantages of sex are short-term while somedisadvantages can be long-term• Discuss methods of showing you care about someone without engaging in sex• Create materials for parents to help them explore, understand, and express theirvalues about sexuality, love and relationships• Assign homework activities in which students ask their parents several questionsabout their values about sexuality, love and relationships• Through class discussions and help from peer leaders, identify and describe thetypes of situations which might lead to undesired sex, and identify multiplestrategies for avoiding each situation• Provide demonstration and practice of skills to refrain from sex when pressured tohave sex• Have teachers or peer leaders demonstrate effective strategies for saying no toundesired sex through scripted roleplays• Have students divide into small groups and practice roleplays by reading scripts• Repeat roleplays with increasingly challenging situations and less scripting,allowing students to use their own skills in more difficult contextsDecrease permissive attitudesabout sex and increase attitudesfavoring abstinence or longterm,faithful relationships ifhaving sexIncrease belief that parents/family have conservativevalues about sex and supportabstinence or long-term,faithful relationships if havingsexIncrease self-efficacy and skillsto abstain from undesired orunprotected sex• Delay initiation ofsex• Reduce frequencyof sex amongsexually active• Reduce number ofpartners• Avoid concurrentpartners• Increase timebetween partners• Have only longterm,mutuallyfaithful partners ifhaving sex• Reduce teenpregnancy• Reduce STD• Have students think clearly about what is the right choice for them in terms of sexand number of partners• Have them think about what circumstances or events might challenge their choiceto abstain from sex or limit sex to one faithful partner• Have them create a personal plan to avoid those circumstances or events orovercome themIncrease intention to abstainfrom sex or to abstain from sexoutside of long-term, faithfulrelationships if having sex(Continued)16 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Provide accurate information about the risks of pregnancy (see above)• Implement simulation activities in which teens see that with each passing month,more teens get pregnant if they have unprotected sex, but don’t get pregnant ifthey abstain (see above)Increase perceived susceptibilityto pregnancyIncrease correct andconsistent use ofcontraceptionReduce teenpregnancy• Have students write down what they would have to do in the next 48 hours if theyjust found out they were pregnant (see above)• Have students write down activities they wish to do in coming years, and then markwhich ones would be difficult or impossible if they had a child (see above)Increase perceived consequencesof pregnancy and childbearing(greater importance ofavoiding pregnancy)• Provide accurate information about the different types contraception commonlyused by adolescents; indicate which protect against both pregnancy and STD;discuss advantages and disadvantages of each; discuss side effects, both positiveand negativeIncrease knowledge about contraception,including the recognitionof positive side effectsof hormonal contraceptives (aswell as negative side effects)• Provide parents with accurate information about adolescent sexual behavior,pregnancy and STD• Give students homework assignments in which they should talk with their parentsor other trusted adults about abstaining from sex, condom use and contraceptionuseIncrease belief that parents/family support contraceptiveuse if sexually active• Provide accurate information about the different types contraception commonlyused by adolescents; state their effectiveness if used correctly; indicate whichprotect against STD; discuss advantages and disadvantages of each; discuss sideeffects, both positive and negative (see above)• Have students identify the ways in which using condoms may reduce pleasure (e.g.,disrupts love making) and identify ways to avoid this (e.g., have a condom ready)(see below)• Identify ways that using condoms and other forms of contraception can make sexmore pleasurableIncrease intention to abstainfrom sex or to abstain from sexoutside of long-term, faithfulrelationships if having sex(Continued)Chapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 17

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Identify peers who are popular among different groups of adolescents and who arewilling to publicly support a message against having unprotected sex and for usingcondoms or other contraceptives• Have groups of peers plan and implement school-wide activities such as assemblies,contests, media materials and small group discussions, all of which promoteavoiding unprotected sex by abstaining from sex and using contraception if havingsex• Conduct school-wide polls and report results showing support for adolescentsavoiding unprotected sex; provide individual stories to personalize results of thepolls• Collect survey data from students and report results showing that most studentsabstain from sex or use condoms or other forms of contraception• Implement plays in which adolescents successfully resist sex or always usecontraceptionIncrease belief that peers usecontraception, if having sexIncrease belief thatpeers support the use ofcontraception, if having sexIncrease correct andconsistent use ofcontraceptionReduce teenpregnancy• Through class discussions and help from peer leaders, identify and describe thetypes of situations that might lead to unprotected sex, and identify multiplestrategies for avoiding each situation• Provide demonstration and practice in using skills to avoid unprotected sex• Have teachers or peer leaders demonstrate effective strategies for saying no tounprotected sex through scripted roleplays and have students practice roleplays• Repeat roleplays in which students insist upon the use of contraceptionIncrease self-efficacy to say noto unprotected sex and to insiston using contraception• Identify places where adolescents can obtain affordable contraception withoutembarrassment• Provide demonstration and practice in how to use condoms properlyIncrease self-efficacy and skill toobtain and use contraception• Have students identify possible situations or changes in their lives that might causethem to forget to take birth control pills and brainstorm ways to overcome thosesituationsIncrease skill to usecontraception consistently• Have students think clearly about what is the right choice for them in terms of sexand condom and contraception use• Have them identify what circumstances or events might challenge that choice• Have them create a plan to avoid those circumstances or events or overcome them• If their choice is to use contraception, have them create a specific plan to obtainand use contraception consistently and correctlyIncrease intentions to usecontraception(Continued)18 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Provide accurate information about the risks of STDs (including HIV) (see above)• Implement simulation activities in which adolescents can see how STDs can spreadrapidly in people engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners (see above)• Have people who are HIV positive talk about the impact that HIV has had upontheir livesIncrease knowledge andperception of risks andconsequences of contracting anSTD (including HIV) if engagingin sex without condomsIncrease correct andconsistent use ofcondomsReduce STD• Provide accurate information on the effectiveness of condoms in preventingpregnancy and STDs, if used consistently and correctlyIncrease knowledge of effectivenessof condoms in preventingpregnancy and STD• Brainstorm ways to have condoms available and ready when needed• Brainstorm ways to make condom use more sensual rather than less sensual• Provide accurate information on how different types of condoms (correct size,lubricated, etc.) can both reduce breakage and slippage and increase pleasureImprove attitudes about condomuse: Decrease attitude thatcondoms are a hassle, interruptthe mood, reduce pleasure, indicatea lack of trust, etc.• Provide parents with accurate information about adolescent sexual behavior,pregnancy, STDs, and the effectiveness of condoms• Give students homework assignments in which they talk with their parents or othertrusted adults about abstaining from sex and condom useIncrease communication withparents about condom use andsupport for use if sexually active• Identify peers who are popular among different groups of adolescents and who arewilling to publicly support a message about avoiding unprotected sex• Have groups of peers plan and implement school-wide activities such as assemblies,contests, small media materials and small group discussions, all of which promoteavoiding unprotected sex by abstaining from sex and using condoms if having sex• Conduct school-wide polls and report results showing support for adolescentsavoiding unprotected sex and using condoms if having sex; provide individualstories to personalize results of the polls• Collect survey data from students and report results showing that most studentsabstain from sex or use condoms• Implement plays in which adolescents successfully resist sex or always use condomsIncrease perception that peerssupport the use of condoms ifsexually active• Have groups of students go to different places where condoms are available andassess how easily and comfortably teens could obtain condoms there• Have students go to one or more places where condoms are available and assess thetypes of condoms available and their costIncrease self-efficacy to obtaincondoms(Continued)Chapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 19

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Have teachers or peer leaders demonstrate effective strategies for refusing toengage in unprotected sex through scripted roleplays and have students practiceroleplays• Repeat roleplays in which students insist upon the use of condomsIncrease self-efficacy to insist onusing condomsIncrease correct andconsistent use ofcondomsReduce STD• Provide demonstration and practice in how to use condoms properlyIncrease self-efficacy to usecondoms correctly• Have students think clearly about what is the right choice for them in terms of sex,condom or other contraceptive use• Have them identify what circumstances or events might challenge that choice• Have them create a plan to avoid those circumstances or events or overcome them• If their choice is to use condoms, have them create a specific plan to obtain and usecondomsIncrease intentions to usecondoms• Provide research data on the high prevalence of HPV among young women• Describe how some varieties of HPV lead to cervical warts and some varieties leadto cervical cancer and death• Provide research data on the relative number of deaths due to cervical cancer andAIDS among women in the last 40 years• Provide research data on the prevalence of Hepatitis B and its consequencesIncrease perception of risks ofHPV and Hepatitis BIncrease vaccinationsfor HPV andHepatitis BReduce STD• Provide research data on the effectiveness of HPV and Hepatitis B vaccines• Provide information on where to obtain vaccinations and the costs of the vaccinesto young people• Have a speaker from a clinic talk about the vaccines and procedures for obtaining itIncrease knowledge ofeffectiveness of HPV andHepatitis B vaccines and placesto obtain vaccinations• Provide research data showing the increases in the percentages of young womenwho are being vaccinated for HPV• Provide role model stories promoting the benefits of vaccination and suggesting itswider use• Collect survey data showing that classroom peers would like to avoid HPV andHepatitis B and support vaccinationIncrease belief that peers arebeing vaccinated for HPV orsupport vaccination• Send information hope to parents with factual information about HPV, cervicalcancer, and the HPV vaccine• Include as part of a homework assignment to talk with parents about beingvaccinated for HPV if femaleIncrease communication withparents about being vaccinatedfor HPV(Continued)20 <strong>Reducing</strong> <strong>Adolescent</strong> <strong>Sexual</strong> <strong>Risk</strong>: A <strong>Theoretical</strong> Guide for Developing and Adapting Curriculum-Based Programs

Figure2-3 An Example of a Logic Model to Reduce Pregnancy and <strong>Sexual</strong>ly Transmitted Diseaseby Implementing a <strong>Sexual</strong>ity Education Curriculum (Continued)Individual <strong>Risk</strong> andCurriculum Activities Protective Factors Behaviors Goals• Provide accurate information about the risks and consequences of STDs (includingHIV) (see above)• Implement simulation activities in which adolescents can see how STDs can spreadrapidly in people engaging in unprotected sex with multiple partners (see above)• Provide accurate information on how some STDs can be cured, how the physicalsymptoms of other viral STDs can be reduced, and how the infectivity of their viralSTDs can be reducedIncrease knowledge of the risksof contracting an STD and theconsequences of undiagnosedSTDsIncrease testing andtreatment of STDReduce STD• Have a guest speaker from a clinic explain the testing and treatment process andwhere testing and treatment services are available• Have students obtain accurate information about the availability of confidentialand low-cost STD testing and treatment services in the local community (see above)and have them assess each service• Have students call or visit a clinic and obtain information about itIncrease knowledge of theavailability of confidential andlow-cost STD testing and treatmentservices• Provide accurate information about STD tests and treatment, emphasizing that STDtests need not be painful• Brainstorm ways to make teens more comfortable going to a clinic for testing (e.g.,go with a friend)Increase positive attitudesand comfort being tested andtreated for STDs• Have students divide into groups and research different STDs and their symptoms;have them create posters or pamphlets showing the common symptoms thatwarrant being checked for STDs• Have students identify other situations that might warrant being tested for STDs(e.g., being tested before stopping condom use and using hormonal contraceptionin a long-term, mutually faithful relationship)Increase self-efficacy to knowwhen to visit a clinic and betested and treated• Show a video on teens and STD testing, clarifying the process of going to a clinic,being tested, notifying partners, etc.• Have students identify the names and locations of the nearest health services thatprovide confidential and low-cost STD testing and treatment services• Have students develop a feasible plan for arranging and getting to those healthservices• Have students call or visit a clinic and obtain information about itIncrease self-efficacy to visit aclinic and be tested and treatedChapter 2 Creating a Logic Model and Learning Objectives 21