What is Art? - Southwestern Law School

What is Art? - Southwestern Law School

What is Art? - Southwestern Law School

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

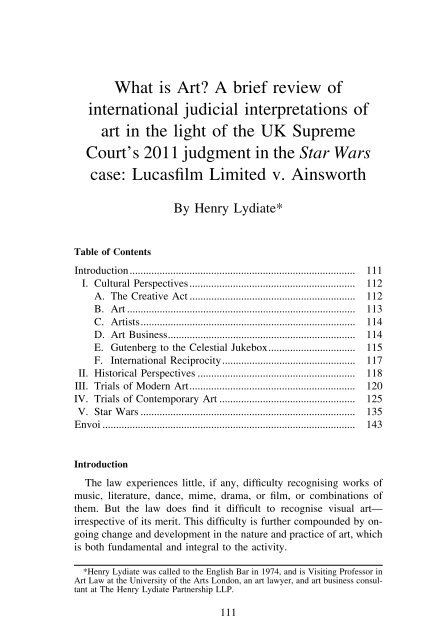

<strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> <strong>Art</strong>? A brief review ofinternational judicial interpretations ofart in the light of the UK SupremeCourt’s 2011 judgment in the Star Warscase: Lucasfilm Limited v. AinsworthBy Henry Lydiate*Table of ContentsIntroduction................................................................................... 111I. Cultural Perspectives............................................................. 112A. The Creative Act ............................................................. 112B. <strong>Art</strong> .................................................................................... 113C. <strong>Art</strong><strong>is</strong>ts............................................................................... 114D. <strong>Art</strong> Business..................................................................... 114E. Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox................................ 115F. International Reciprocity................................................. 117II. H<strong>is</strong>torical Perspectives .......................................................... 118III. Trials of Modern <strong>Art</strong>............................................................. 120IV. Trials of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong> .................................................. 125V. Star Wars ............................................................................... 135Envoi ............................................................................................. 143IntroductionThe law experiences little, if any, difficulty recogn<strong>is</strong>ing works ofmusic, literature, dance, mime, drama, or film, or combinations ofthem. But the law does find it difficult to recogn<strong>is</strong>e v<strong>is</strong>ual art—irrespective of its merit. Th<strong>is</strong> difficulty <strong>is</strong> further compounded by ongoingchange and development in the nature and practice of art, which<strong>is</strong> both fundamental and integral to the activity.*Henry Lydiate was called to the Engl<strong>is</strong>h Bar in 1974, and <strong>is</strong> V<strong>is</strong>iting Professor in<strong>Art</strong> <strong>Law</strong> at the University of the <strong>Art</strong>s London, an art lawyer, and art business consultantat The Henry Lydiate Partnership LLP.111

112 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2These <strong>is</strong>sues are important for lawyers, jur<strong>is</strong>ts and art<strong>is</strong>ts—as wellas the wider public—and locate within in an increasingly global artenvironment. We will explore them in five parts:• cultural perspectives• h<strong>is</strong>torical perspectives• trials of modern art• trials of contemporary art• the recent Star Wars case.I. Cultural PerspectivesBefore exploring the h<strong>is</strong>tory of cases where art and art<strong>is</strong>ts havefound themselves before courts of law, let us first consider creativity,art, art<strong>is</strong>ts, art business, and art practice.A. The Creative ActMarcel Duchamp <strong>is</strong> widely recogn<strong>is</strong>ed as one of the most influentialart<strong>is</strong>ts of the 20th century, in the middle of which, he offered a personalview of the creative process: “Millions of art<strong>is</strong>ts create; only a few thousandsare d<strong>is</strong>cussed or accepted by the spectator and many less again areconsecrated by posterity. In the last analys<strong>is</strong>, the art<strong>is</strong>t may shout fromall the rooftops that he <strong>is</strong> a genius: he will have to wait for the verdictof the spectator in order that h<strong>is</strong> declarations take a social value, andthat posterity finally includes him in the primers of <strong>Art</strong> H<strong>is</strong>tory. I knowthat th<strong>is</strong> statement will not meet with the approval of many art<strong>is</strong>ts whorefuse th<strong>is</strong> medium<strong>is</strong>tic role and ins<strong>is</strong>t on the validity of their awarenessin the creative act—yet, <strong>Art</strong> H<strong>is</strong>tory has cons<strong>is</strong>tently decidedupon the virtues of a work of art through considerations completelydivorced from the rationalized explanations of the art<strong>is</strong>t.” 1He goes on to assert: “<strong>Art</strong> may be bad, good or indifferent, butwhatever adjective <strong>is</strong> used we must call it art, and bad art <strong>is</strong> still artin the same way that a bad emotion <strong>is</strong> still an emotion.” 2Furthermore, and central to h<strong>is</strong> thes<strong>is</strong>, he suggests: “The creative acttakes another aspect when the spectator experiences the phenomenonof transmutation: through the change from inert matter into a work ofart, an actual transubstantiation has taken place, and the role of the spectator<strong>is</strong> to determine the weight of the work on the aesthetic scale.” 31. From Marcel Duchamp’s public talk on The Creative Act delivered at the Conventionof the American Federation of <strong>Art</strong>s, Houston, Texas, in April 1957.2. Id.3. Id.

114 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2sent they have entered the tradition as if by simple chronologicald<strong>is</strong>tance.” 8C. <strong>Art</strong><strong>is</strong>tsEven though there <strong>is</strong> ample evidence of surviving art and artefactsand architecture from the dawn of civil<strong>is</strong>ation, there <strong>is</strong> little knowledgeof the identity of their authors. 9 It was not until the 17th century, chieflyduring the Golden Age of art and architecture in the Netherlands andduring the Qing Dynasty in China, that surviving records began to identifyart<strong>is</strong>ts as we have come to know them today—creating works on aspeculative bas<strong>is</strong> and offering them for sale in the open market.The interaction of social and economic changes, over time, provideskeys to our understanding of why societies gradually embraced thepractice of art<strong>is</strong>t as a d<strong>is</strong>tinct career—“of men who spend all theirtime in the production of useless things . . . who are exempted fromgrowing food.” 10 Urban dwellers have always relied on buying surplusesproduced by rural labour, and especially in cities where a significantmass of wealthy and powerful people—high net worth individuals—can also afford to patron<strong>is</strong>e original creations of the ‘art<strong>is</strong>t’.D. <strong>Art</strong> BusinessDirect patronage of the wealthy and powerful was the principalsource of income for creators of art and artefacts and architectureuntil the 17th century, or so. Scientific, technical, and industrial inventionsand developments from around th<strong>is</strong> era (and beyond, to date) increasinglyfacilitated the creation of artworks that were moveable andtransportable objects. Th<strong>is</strong> led to: the practice of collecting uniqueand desirable art objects, also and increasingly by the newly r<strong>is</strong>ing8. Id.9. “In the Middle Ages the individual art<strong>is</strong>t remains inv<strong>is</strong>ible behind the corporatefacades of church and guild. Greco-Roman and Chinese h<strong>is</strong>tories alone report in anydetail the conditions of individual art<strong>is</strong>ts’ lives. A few names and lines of text are allwe have about Egyptian dynastic art<strong>is</strong>ans. The records of the other civil<strong>is</strong>ations of antiquityin America, Africa, and India tell nothing of art<strong>is</strong>ts’ lives. Yet the archaeologicalrecord repeatedly shows the presence of connected series of rapidly changingmanufactures in the cities, and slower ones in the provinces and in the countryside,all manifesting the presence of persons whom we call art<strong>is</strong>ts.” KUBLER, note 6 supra.10. The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman was an exhibition held at The Brit<strong>is</strong>h Museumin London in 2012. It was an installation of new works by Turner Prize winnerGrayson Perry, compr<strong>is</strong>ing objects made by unknown men and women throughout h<strong>is</strong>toryfrom the Brit<strong>is</strong>h Museum’s collection alongside new works by Perry; who explained:“Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> a memorial to all the anonymous craftsmen that over the centurieshave fashioned the manmade wonders of the world. . .The craftsman’s anonymityI find especially resonant in an age of the celebrity art<strong>is</strong>t.” See http://www.brit<strong>is</strong>hmuseum.org/whats_on/exhibitions/grayson_perry/introduction.

WHAT IS ART? 115merchant classes; re-sales of works, and the establ<strong>is</strong>hment of the artmarket place of auction houses 11 and dealers; the foundation of national/statemuseums and galleries to curate and publicly exhibit artand other cultural objects acquired from other states as symbols ofconquest. 12 Such activities involved many and various transactionswe now describe as the art business, most requiring legal form or regulation:comm<strong>is</strong>sioning contracts; sales contracts; deeds of gift orloan; import taxes and export restrictions; establ<strong>is</strong>hment of trustsand foundations for collections and related endowments; and the creationof statutory public authorities.New technologies and techniques were avidly embraced by art<strong>is</strong>tskeen to extend their market place, by making reproductions of theirunique works and selling them at much lower and affordable pricesto the general public: our next consideration.E. <strong>Art</strong> Practice: Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox 13The Western printing press was invented around 1440 by Gutenberg.14 Th<strong>is</strong> seminal technology not only revolution<strong>is</strong>ed and facilitatedindustrial production of literary texts, but also mass d<strong>is</strong>semination ofcopies of unique paintings and drawings. During the following twocenturies the printing press became widely used throughout the thendeveloped world. A variety of v<strong>is</strong>ual images—technical drawings andinstructions, humorous cartoons, illustrated advert<strong>is</strong>ements—became increasinglypopular, especially with the largely illiterate masses, andadded a new option alongside the ex<strong>is</strong>ting fine art prints produced bymore limited autographic reproductive processes.Writers and their publ<strong>is</strong>hers then became concerned that unauthor<strong>is</strong>edcopying and publication of their original literary workswas seriously damaging their sales income, and eventually persuadedgovernments to leg<strong>is</strong>late through a limited form of what we now call11. Sotheby’s auction house was establ<strong>is</strong>hed in 1744 (see http://www.sothebys.com/en/inside/about-us.html; Chr<strong>is</strong>tie’s in 1766 (see http://www.chr<strong>is</strong>ties.com/about/company/h<strong>is</strong>tory.aspx, both in London, England; and Drouot in 1852, in Par<strong>is</strong>, France(see http://www.drouot.com/static/drouot_h<strong>is</strong>torique_enchere.html?lang=en.12. The Brit<strong>is</strong>h Museum, London, England, was opened to the public in 1759;Musée du Louvre, Par<strong>is</strong>, France, in 1793; Nationale Kunst-Gallerij, The Hague, Netherlands,in 1800 (relocated to a new building in Amsterdam and renamed The Rijksmuseumin 1885); Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid, Spain, in 1819; The NationalGallery, London, England, in 1824; and the State Hermitage, Saint Petersburg, Russia,in 1852.13. The Celestial Jukebox was originated by Paul Goldstein in PAUL GOLDSTEIN,COPYRIGHT’S HIGHWAY (2003).14. Johannes Gensfle<strong>is</strong>ch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (1398–1468).

116 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2copyright in the common law world. 15 The first such law was enactedin 1709/10 by the Engl<strong>is</strong>h Parliament, commonly known as the Statuteof Anne, 16 and was soon emulated in other countries. 17V<strong>is</strong>ual art<strong>is</strong>ts 18 subsequently lobbied governments to include theirworks in copyright laws, which initially protected recogn<strong>is</strong>ed artforms—drawings, paintings, prints, sculpture, architecture—againstcopying and publ<strong>is</strong>hing without the art<strong>is</strong>t’s prior consent; and to doso irrespective of art<strong>is</strong>tic content or quality (a subject to which we returnlater). Over the last hundred years or so, art<strong>is</strong>ts have developedmany new and radically different forms of art—reaching far beyondthe traditional forms recogn<strong>is</strong>ed at the end of the 19th century. Duringth<strong>is</strong> dramatic period of art<strong>is</strong>tic innovation, copyright leg<strong>is</strong>lation hasbeen very slow to respond in recogn<strong>is</strong>ing such new art media and practice(a subject to which we also return later).However, over the last century copyright leg<strong>is</strong>lation has kept betterpace with the development of new technology and processes for reproducingand publ<strong>is</strong>hing copies of artworks. Leg<strong>is</strong>lative changes weremade to outlaw copying and d<strong>is</strong>semination of copyright works throughunauthor<strong>is</strong>ed audio/v<strong>is</strong>ual recording, physical copying by analogueor digital means and physical or digital d<strong>is</strong>tribution thereof. Digitald<strong>is</strong>tribution, especially the development of online sharing and storagemethods, <strong>is</strong> an area where the law has struggled to keep pace. Cloudcomputing, where personal data <strong>is</strong> stored across a network of servers,<strong>is</strong> a recent lawful development of methods used by illegal file sharingnetworks, facilitating interaction between users who w<strong>is</strong>h to share copyrightmaterial across a vast network of individual computer systems.In recent years, major telev<strong>is</strong>ion broadcasters have establ<strong>is</strong>hed ondemandservices for their viewers that operate in a similar way to You-Tube 19 ; or have a YouTube channel where current programmes arelawfully available on-demand for no fee, and with targeted webspecificequivalents of the broadcast advert<strong>is</strong>ements: a celestial juke-15. It <strong>is</strong> known as le droit d’auteur in French, diritto d’autore in Italian, and derechosde autor in Span<strong>is</strong>h.16. The Copyright Act 1709 gave authors the exclusive right to reproduce theirworks for 14 years. See http://www.copyrighth<strong>is</strong>tory.com/anne.html17. Th<strong>is</strong> includes the Copyright Clause in the U.S. Constitution “The Congressshall have Power . . . To promote the Progress of Science and useful <strong>Art</strong>s, by securingfor limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respectiveWritings and D<strong>is</strong>coveries.” (U.S. CONST., art. I, § 8, cl. 8); and the Copyright Act1790, 1 Stat. at Large 124 (1790).18. The Engraving Copyright Act 1734 was enacted in Britain; sometimes calledHogarth’s Act after the popular art<strong>is</strong>t who lobbied for th<strong>is</strong> law. William Hogarth(1697–1764) was an Engl<strong>is</strong>h painter, printmaker, illustrator and satirical cartoon<strong>is</strong>t.19. Such as the BBC iPlayer.

WHAT IS ART? 117box. The concept of the celestial jukebox <strong>is</strong> exemplified by Spotify:rather than delivering a music file for retention by the subscriber (aswith iTunes), material <strong>is</strong> streamed on demand to the user—literally,a jukebox via satellite transm<strong>is</strong>sion.F. International ReciprocityIn 1886, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, developed nationspromulgated the Berne Convention. 20 Th<strong>is</strong> seminal internationalagreement (and its subsequent rev<strong>is</strong>ions throughout the 20th century)addressed two key problems relating to the worldwide enforcementof copyright: each signatory country’s copyright leg<strong>is</strong>lation was differentto the others, and was not enforceable beyond its own jur<strong>is</strong>dictionalboundaries. Signatories undertook to amend their domestic leg<strong>is</strong>lation: toprovide minimum standards for domestic/national copyright law; and torecognize and enforce the copyright works of authors from other signatorycountries, as they did for their own authors. The Berne Convention’sinternational harmon<strong>is</strong>ation and reciprocal enforcement of copyrightlaws provided a model for subsequent international intellectual propertytreaties throughout the 20th century, to date. 21However, international agreements encounter common language andtranslation <strong>is</strong>sues, especially when seeking to describe or define art.Diplomatic comprom<strong>is</strong>es and concessions are made to achieve agreement,often producing bland or ambiguous treaty prov<strong>is</strong>ions. Internationalagreements concerning copyright generally permit each signatorycountry itself to interpret and/or define any legal meaning of art withinits own national leg<strong>is</strong>lation. For example, the Berne Convention initiallydescribes “art<strong>is</strong>tic works” as follows: “every production in the art<strong>is</strong>ticdomain, whatever may be the mode or form of its expression”; thencontinues by specifying an inclusionary l<strong>is</strong>t of art forms: “such asworks of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving and lithography;photographic works to which are assimilated works expressedby a process analogous to photography; works of applied20. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and <strong>Art</strong><strong>is</strong>tic Works (1886)(hereinafter “Berne Convention”), http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/trtdocs_wo001.html The UK joined the Berne Union in 1887, the U.S. in 1989; by 2011there were 164 member countries. See also http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/.21. See Universal Copyright Convention (1952), http://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/other_treaties/text.jsp?file_id=172836; Universal Copyright Convention (1971),http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15241&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html; Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual PropertyRights (TRIPS) (1994), http://www.wto.org/engl<strong>is</strong>h/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf; andthe World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Copyright Treaty (Dec. 20,1996), www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/wct/trtdocs_wo033.html.

118 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2art; illustrations, maps, plans, sketches and three-dimensional worksrelative to geography, topography, architecture or science.” 22 It thenprovides: “It shall, however, be a matter for leg<strong>is</strong>lation in the countriesof the Union to prescribe that works in general or any specified categoriesof works shall not be protected unless they have been fixedin some material form.” 23 Whether national copyright laws of BerneConvention countries have been able to implement Berne in suchways that recogn<strong>is</strong>e innovative v<strong>is</strong>ual art forms developed during thelast 100 years or so, will be explored later; as will difficulties encounteredby courts applying such laws to specific cases.II. H<strong>is</strong>torical Perspectives<strong>Art</strong> <strong>is</strong> no stranger to the courtroom. Western art h<strong>is</strong>tory <strong>is</strong> pepperedwith cases where v<strong>is</strong>ual art has been the central factual and legal <strong>is</strong>suefor the court 24 ; and where judges have been required to consider itsrelevance in a legal context—usually, but not always, reluctantly.Two landmark cases will be considered in pursuit of th<strong>is</strong> article’s thes<strong>is</strong>.1511 Italy: Dürer v. Raimondi 25From around 1501 Dürer 26 made and marketed a series of 19 woodcutprints about the Life of the Virgin. These were of an exceptionallyhigh standard, and attracted the attention of Marcantonio Raimondi(the engraver used by Dürer’s friend and colleague Raphael 27 ) whowas able to engrave, print, and sell multiple copies of them—withoutDürer’s knowledge or consent. Raimondi ignored Dürer’s eventual‘cease and des<strong>is</strong>t’ entreaties (directly and via Raphael), and continuedh<strong>is</strong> evidently profitable merchand<strong>is</strong>ing venture. In 1511 Dürer finallysought a legal remedy from the Senate of the Venetian Republic. 28The facts were not in d<strong>is</strong>pute and, in the absence of any intellectual22. Berne Convention, note 20, supra, art. 2(1).23. Id., art. 2(2).24. For wider contemporary consideration of many more such cases, see LAURIEADAMS, ART ON TRIAL (1976); DANIEL MCCLEAN, THE TRIALS OF ART (2007).25. For a fuller exploration of th<strong>is</strong> case, see PON, L.RAPHAEL, DÜRER &MARCAN-TONIO RAIMONDI: COPYING AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE PRINT (2004).26. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was a German painter, printmaker and engraver:leading art<strong>is</strong>t of the Northern Rena<strong>is</strong>sance. He achieved great success throughout Europe,in large part through h<strong>is</strong> multiple reproduction prints of h<strong>is</strong> own paintings anddrawings.27. Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483–1520) was a progenitor of the Italian HighRena<strong>is</strong>sance.28. From the 7th century to 1797 it was formally entitled the Most Serene Republicof Venice. In 1511 Venice was one of the leading sea-faring and trading nations in thethen developed world.

WHAT IS ART? 119property rights laws, the Senate exerc<strong>is</strong>ed its inherent jur<strong>is</strong>dictionalpowers over trade to allow Raimondi to continue producing and merchand<strong>is</strong>ingDürer’s images; with the prov<strong>is</strong>o that he could not in thefuture include on them Dürer’s unique ‘AD’ signature or brand. 29Not only <strong>is</strong> th<strong>is</strong> one of the earliest recorded cases in the developmentof copyright laws, it also illustrates the Senate’s difficulty in understandingthe true nature of Dürer’s art (and h<strong>is</strong> legal claim). TheSenate seemingly focused on the innovative and highly technicalskill and labour Raimondi employed in making engraved copies; noton the art. Dürer’s original images were the art; not h<strong>is</strong> original woodcutsor h<strong>is</strong> prints thereof, and not Raimondi’s engraved renditions ofDürer’s original images or h<strong>is</strong> prints thereof. In granting Dürer a remedyin relation to Raimondi’s future use of h<strong>is</strong> “logo”—h<strong>is</strong> brandidentity—the Senate also heralded the development of what becametrademark and other intellectual property laws.1573 Italy: Inquiry of the Venetian Inqu<strong>is</strong>ition v. Veronese 30In 1572, at the height of h<strong>is</strong> career, Veronese 31 was comm<strong>is</strong>sionedby the monastery of San Giovanni e Paolo in Venice to make a largepainting of The Last Supper to adorn the refectory, to replace an earlierwork by Titian 32 that had been destroyed by fire the previousyear. In 1573 Veronese delivered a very large canvas, 39 feet wideby 17 feet high, on which he had updated the ancient Biblicalscene by placing it in a contemporary Italian palazzo. 33 He had expandedthe traditional gathering of Jesus and h<strong>is</strong> twelve d<strong>is</strong>ciplesby adding a large number of curious-looking people, including “buffoons,drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities ...ajesterwith a parrot on h<strong>is</strong> wr<strong>is</strong>t . . . a servant who has a nose-bleed from someaccident...armedmendressedinthefashionofGermany,withhalberdsin their hands” 3429.30. For an Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation of the trial transcript, See FRANCIS MARION CRAWFORD,SALVE VENETIA: GLEANINGS FROM VENETIAN HISTORY. VOLUME: 1 (1905); Elizabeth C.Childs, Suspended License: Censorship and the V<strong>is</strong>ual <strong>Art</strong>s (1997).31. Paolo Cagliari (1528–1588), popularly known as Veronese from the city of h<strong>is</strong>birth, Verona was an eminent fresco and oil painter in the Manner<strong>is</strong>t style of the ItalianLate or High Rena<strong>is</strong>sance, especially in Venice alongside Titian and Tintoretto.32. Tiziano Vecellio (1488–1576), popularly known as Titian, was the pre-eminentmember of the so-called Venetian <strong>School</strong>, with Veronese and Tintoretto.33. Such “modern<strong>is</strong>ation” was commonly pract<strong>is</strong>ed by art<strong>is</strong>ts during theRena<strong>is</strong>sance.34. Crawford, supra note 30; Childs, supra note 30.

120 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2The Roman Catholic Church at that time jealously guarded its articlesof faith, especially from attack by the rapidly growing ProtestantChr<strong>is</strong>tian faiths in Northern Europe: so much so that, a decade earlier,the Ecumenical Council of Trent had decreed a key tenet to be that thebread and wine at the Roman Catholic Mass transubstantiated into thebody and blood of Chr<strong>is</strong>t. In th<strong>is</strong> politically sensitive climate, it wasinevitable that Veronese was prosecuted for h<strong>is</strong> inclusion of such charactersin h<strong>is</strong> composition. 35 The Inqu<strong>is</strong>itor asked Veronese “Did someperson order you to paint Germans, buffoons, and other similar figuresin th<strong>is</strong> picture?” Veronese replied “No, but I was comm<strong>is</strong>sioned toadorn it as I thought proper; now it <strong>is</strong> very large and can containmany figures ...Wepainters take the same licence as do poets andmadmen.” 36 The Inqu<strong>is</strong>ition’s judgment was temperate: Veronesewas ordered to “correct” the painting. After some months of reflectionVeronese achieved th<strong>is</strong>, by painting on the canvas these words: “Feastin the House of Levi”. 37Th<strong>is</strong> uncomprom<strong>is</strong>ing yet elegantly diplomatic solution evidentlysat<strong>is</strong>fied the court of Inqu<strong>is</strong>ition, 38 and not only demonstrates the professionalconfidence of the art<strong>is</strong>t in defending h<strong>is</strong> own work under forensicinquiry; but also reflects the Inqu<strong>is</strong>ition’s surpr<strong>is</strong>ingly enlightenedapproach that respected the art<strong>is</strong>t’s professional independence.Th<strong>is</strong> case also heralds key <strong>is</strong>sues (to which we return later): thepower and influence exerc<strong>is</strong>able by art<strong>is</strong>ts of high standing; and judicialrecognition of the importance of the art<strong>is</strong>t’s intentions in the creativeact.III. Trials of Modern <strong>Art</strong>From the early Italian Rena<strong>is</strong>sance period around 1400 through tothe mid-19th century, successive generations of art<strong>is</strong>ts in the westernworld sought to produce images as true to life as their techniqueswould allow. Even though the form and content of art was increasinglynatural<strong>is</strong>tic and real<strong>is</strong>tically representational throughout these centuries,courts struggled to interpret, construct and apply the law tocases where they were required to recogn<strong>is</strong>e and understand the art35. Crawford, supra note 30; Childs, supra note 30.36. Id.37. Reference to the feast <strong>is</strong> contained in Luke’s Gospel: “And Levi made him agreat feast in h<strong>is</strong> own house: and there was a great company of publicans and of othersthat sat down with them.” Luke 5:29 (King James version).38. The canvas survived, unaltered further; it now hangs at the Gallerie dell’Accademiain Venice, Italy.

WHAT IS ART? 121of their era. 39 Such forensic difficulties were relatively modest, comparedwith the greater challenges thrown up by the work of art<strong>is</strong>ts fromthe second half of the 19th century 40 to date. Around 1840 art<strong>is</strong>tsfiercely debated whether the invention of photography 41 heralded“the death of art”. 42 Many young and emerging art<strong>is</strong>ts reacted againstphotography by creating works depicting images a photograph couldnot achieve. The celebrated 1863 Salon des Refusés 43 in Par<strong>is</strong>, Franceheralded the birth of what we now know as Impression<strong>is</strong>m, 44 whichthen developed into Post-Impression<strong>is</strong>m. 45 The innovation continuedas subsequent generations variously developed Symbol<strong>is</strong>m, 46 Fauv<strong>is</strong>m,47 Cub<strong>is</strong>m, 48 Expression<strong>is</strong>m, 49 Surreal<strong>is</strong>m, 50 throughtoPop<strong>Art</strong> 51 :a hundred year period contemporary art h<strong>is</strong>torians now classify asModern <strong>Art</strong>.39. See McClean, supra note 24.40. See Wh<strong>is</strong>tler v. Ruskin, d<strong>is</strong>cussed in the text accompanying notes 53–59 infra.Th<strong>is</strong> 1878 lawsuit exemplifies the turbulent debates during the last quarter of the 19thcentury between art<strong>is</strong>ts themselves, and with critics and conno<strong>is</strong>seurs, over thennascent Modern <strong>Art</strong> styles, forms, techniques, and subject-matter.41. Lou<strong>is</strong>-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) was a French art<strong>is</strong>t and physic<strong>is</strong>t,who invented the first (daguerreotype) photographic technique in 1837.42. Walter Benjamin, A Short H<strong>is</strong>tory of Photography (Literar<strong>is</strong>che Welt, Germany,18 & 19 Sept. and 2 Oct. 1931).43. The prestigious Par<strong>is</strong> Salon of 1863 was inaugurated by the French government.The selection jury rejected as unsat<strong>is</strong>factory around 3,000 works submittedby young and emerging art<strong>is</strong>ts, who vociferously complained to the authorities.Such art<strong>is</strong>ts were offered showing space in a small annex to the main Salon, whererejected works were shown; these works included one by the 31 year-old ÉdouardManet (Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1862–3), which <strong>is</strong> now in the French national collectionat the Musée d’Orsay, Par<strong>is</strong>) and one by the 29 year-old James McNeill Wh<strong>is</strong>tler(Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1861–2), which <strong>is</strong> now in the collectionof the National Gallery of <strong>Art</strong>, Washington, D.C.44. Early Impression<strong>is</strong>ts notably included Frédéric Bazille (22), Armand Guillaumin(22), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (22), Claude Monet (23), Paul Cézanne (24), AlfredS<strong>is</strong>ley (24), Édouard Manet (31), and Camille P<strong>is</strong>sarro (33).45. Notably: Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Georges-Pierre Seurat, PaulCézanne, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.46. Notably: Frida Kahlo, Gustav Klimt, Gustave Moreau, Edvard Munch, andAuguste Rodin.47. Notably: André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Henri Mat<strong>is</strong>se, Jean Puy, and GeorgesRouault.48. Notably: Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp, Fernand Léger, Franc<strong>is</strong> Picabia,Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, and Max Weber. Also notably, Cub<strong>is</strong>t works werefirst exhibited in the United States in 1913 at the landmark Armory Show in NewYork City.49. Notably: Egon Schiele, Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Marc Chagall, Willemde Kooning, and Max Weber.50. Notably: Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Franc<strong>is</strong> Picabia, SalvadorDalí, Lu<strong>is</strong> Buñuel, Alberto Giacometti, and René Magritte.51. Notably: Peter Blake, Patrick Caulfield, Jim Dine, Richard Hamilton, KeithHaring, David Hockney, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Allen Jones, Roy Lichtenstein,Takashi Murakami, Claes Oldenburg, Eduardo Paolozzi, Robert Rauschenberg, LarryRivers, Ed Ruscha, and Andy Warhol.

122 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2How did courts respond to the ever-changing form and content ofwhat art<strong>is</strong>ts regarded as their art in the late 19th and early 20th century?Our starting point will be consideration of judgment of a work by anearly ‘modern’ art<strong>is</strong>t, James Wh<strong>is</strong>tler. 521878 England: Wh<strong>is</strong>tler v. Ruskin 53Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (1872–1875) 54 waspainted by Wh<strong>is</strong>tler in oils on canvas. The subject was a night-timefireworks d<strong>is</strong>play over Battersea Bridge in London. The small (23.7inches high by 18.3 inches wide) painting was executed in an impression<strong>is</strong>tic,rather than the (then) orthodox representational, style: it conveyeda sense of atmosphere, with glowing colours and drifting smokeagainst a dark sky over the River Thames. The work was first exhibitedat the prestigious Grosvenor Gallery in London, in a group showthat included paintings by Pre-Raphaelite art<strong>is</strong>ts such as EdwardBurne-Jones. The critic John Ruskin 55 publ<strong>is</strong>hed a review of theshow in one of h<strong>is</strong> popular pamphlets, Fors Clavigera, on 2 July1877. He lauded Burne-Jones and others; but lambasted Wh<strong>is</strong>tler:“For Mr. Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s own sake, no less than for the protection of thepurchaser, [the Grosvenor Gallery] ought not to have admitted worksinto the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the art<strong>is</strong>t so nearlyapproached the aspect of wilful imposture. I have seen, and heard, muchof Cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcombask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’sface.” 56Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s sales took a sharp downturn after Ruskin’s widely publ<strong>is</strong>hedattack. Wh<strong>is</strong>tler sued for libel, seeking £1,000 for damage to52. James Abbott McNeill Wh<strong>is</strong>tler (1834–1903) was an art<strong>is</strong>t born in Lowell,Massachusetts, who relocated to Europe, Par<strong>is</strong> in particular, eventually settling inLondon. He became widely known through h<strong>is</strong> close association in the 1860s withcontroversial “modern” art<strong>is</strong>ts such as the French Real<strong>is</strong>t painter Gustave Courbetand the Impression<strong>is</strong>t Éduard Manet.53. Officially unreported. The case was tried at the Court of Exchequer Div<strong>is</strong>ionof the High Court in London on 25 and 26 Nov.1978. Wh<strong>is</strong>tler v. Ruskin, THETIMES (LONDON), Nov. 27, 1878, at 9. See also LINDA MERRILL, APOT OF PAINT: AES-THETICS ON TRIAL IN WHISTLER V. RUSKIN (1992).54. It <strong>is</strong> now in the collection of the Detroit Institute of <strong>Art</strong>s, Detroit, Michigan.55. John Ruskin (1819–1900) was a pre-eminent and very influential Brit<strong>is</strong>h art criticof h<strong>is</strong> generation, who professed that an art<strong>is</strong>t’s core function was “truth and nature”. Hewas a staunch defender of then controversial “modern” paintings by J. M. W. Turneragainst fierce critics. He was greatly influenced Pre-Raphaelite painters such as WilliamHolman Hunt, John Everett Milla<strong>is</strong> and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and founded the Ruskin<strong>School</strong> of Drawing at Oxford University.56. RONALD ANDERSON &ANNE KOVAL, JAMES MCNEILL WHISTLER: BEYOND THEMYTH 215.

WHAT IS ART? 123h<strong>is</strong> art<strong>is</strong>tic reputation. To do so, he and h<strong>is</strong> lawyer had to convince thejury of h<strong>is</strong> art<strong>is</strong>tic abilities and standing.Study of Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s cross-examination reveals the heart of Ruskin’sline of defence. Question: “<strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong> the subject of Nocturne in Blackand Gold: The Falling Rocket?” Wh<strong>is</strong>tler: “It <strong>is</strong> a night piece and representsthe fireworks at Cremorne Gardens.” Question: “Not a view ofCremorne?” Answer: “If it were A View of Cremorne it would certainlybring about nothing but d<strong>is</strong>appointment on the part of the beholders.It <strong>is</strong> an art<strong>is</strong>tic arrangement. That <strong>is</strong> why I call it a nocturne.”Question: “Did it take you much time to paint the Nocturne in Blackand Gold? How soon did you knock it off?” Answer: “Oh, I ‘knockone off ’ possibly in a couple of days—one day to do the work and anotherto fin<strong>is</strong>h it ...”.Question: “The labour of two days <strong>is</strong> that forwhich you ask two hundred guineas?” Answer: “No, I ask it for theknowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.” 57Wh<strong>is</strong>tler was the David of the forensic set-piece, Ruskin the Goliath.Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s many art<strong>is</strong>t peers and supporters, who had prom<strong>is</strong>ed to give evidence,failed to do so; Ruskin’s did, including Burne-Jones. The jury’stask was invidious: effectively, whether to recogn<strong>is</strong>e art<strong>is</strong>tic merit inthe (then) unorthodox ‘modern’ painting style of so-called impression<strong>is</strong>m;and, if so, to place a monetary value on Ruskin’s damage to Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’sprofessional reputation. Ruskin was found guilty, and ordered topay one farthing 58 in damages. Costs were borne by each party. Such der<strong>is</strong>oryawards were commonplace at the time, whenever juries in civil trialswere faced with “a delicate and ultimately insoluble legal dilemma.” 59Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> arguably the last time an art<strong>is</strong>t sued a critic for defamation.The courtroom <strong>is</strong> clearly the wrong place for a forensic fight over aestheticmerit. Indeed, it has often been said over the intervening centurythat Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s lawyers would have been w<strong>is</strong>er to claim (if at all) damageto Wh<strong>is</strong>tler’s sales of work (of which there was ample hard evidencefollowing Ruskin’s public attack), rather than damage to h<strong>is</strong>art<strong>is</strong>tic competence.We now consider the landmark trial of art initiated by a progenitorof Modern <strong>Art</strong>, often referred to as the Patriarch of Modern Sculpture,Romanian art<strong>is</strong>t Constantin Brâncuşi. 6057. PETRA TEN-DOESSCHATE CHU, NINETEENTH CENTURY EUROPEAN ART 349.58. Th<strong>is</strong> was the lowest value coin of the Realm.59. Franc<strong>is</strong> L. Fennell, The Verdict in Wh<strong>is</strong>tler v. Ruskin, VICTORIAN NEWSLETTER,Fall 1971, at 17, 21.60. Constantin Brâncuşi (1876–1957) was an Abstract Expression<strong>is</strong>t sculptor, bornin Romania, who settled and remained in Par<strong>is</strong>, France from 1904.

124 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 21928 USA: Brâncuşi v. United States 61In the 1920s Brâncuşi began an exploration of the shapes of birds inflight. In 1923 he carved a work in marble that “concentrated not onthe physical attributes of the bird but on its movement. In Bird inSpace wings and feathers are eliminated, the swell of the body <strong>is</strong> elongated,and the head and beak are reduced to a slanted oval plane.Balanced on a slender conical footing, the figure’s upward thrust <strong>is</strong> unfettered.Brancusi’s inspired abstraction realizes h<strong>is</strong> stated intent tocapture ‘the essence of flight.’ Th<strong>is</strong> particular conception of Bird inSpace <strong>is</strong> the first in a series of seven sculptures carved from marbleand nine cast in bronze, all of which were painstakingly smoothedand pol<strong>is</strong>hed.” 62In 1926 a consignment of twenty Brâncuşi sculptures arrived atNew York by steamship from France, including a bronze version ofBird In Space. 63 US Customs demanded payment of import duty of40% of the market value of its bronze material as ‘merely a manufactureof metal’: around $230. Works of art could be imported duty freeunder the 1922 Tarrif Act. Brâncuşi filed suit claiming that h<strong>is</strong> workwas in law an ‘original sculpture’ and therefore exempt from importduty. 64 At the heart of the case lay the question: what <strong>is</strong> Modern <strong>Art</strong>?In 1928 a US Customs Court in New York ruled that Brâncuşi’ssculpture was a work of art, not an ‘article of utility’, as US Customshad claimed. Th<strong>is</strong> seminal trial, and especially its enlightened ruling,has been cited by art lawyers worldwide for eight decades as an iconiclegal precedent. Both parties called expert witnesses to attest whetherthe bronze artefact was indeed art. The US Customs appra<strong>is</strong>er had assertedthat “Several men, high in the art world were asked to expresstheir opinions for the Government and one of them told us, ‘If that’sart, hereafter I’m a bricklayer.’ Another said, ‘Dots and dashes areas art<strong>is</strong>tic as Brâncuşi’s work.’ In general, it was their opinion thatBrâncuşi left too much to the imagination.” Brâncuşi gave evidence61. Brancusi v. United States, 54 Treas. Dec. Cust. 428 (Cust. Ct. 1928).62. Catalogue entry of the Metropolitan Museum of <strong>Art</strong>, New York, which acquiredthe original marble sculpture in 1995 as a bequest from Florene M. Schoenborn,who had bought the work in 1942: 57 inches high, 6 1/2 inches diameter. A seriesof seven was made in marble. Nine were cast in bronze (two of which are in thecollection of Museum of Modern <strong>Art</strong>, New York, one at the Philadelphia Museum of<strong>Art</strong>). One sold at auction in the U.S. for $27.5 million in 2005, the then highest hammerprice for any sculpture.63. U.S. photographer Edward Steichen had bought the work in France and Brâncuşiarranged for it to be shipped to the United States, accompanied by the art<strong>is</strong>t’sfriend and colleague Marcel Duchamp.64. Marcel Duchamp suggested the lawsuit; Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney financed it.

WHAT IS ART? 125of h<strong>is</strong> execution of the work: “I conceived it to be created in bronzeand I made a plaster model of it. Th<strong>is</strong> I gave to the founder, togetherwith the formula for the bronze alloy and other necessary indications.When the roughcast was delivered to me, I had to stop up the air holesand the core hole, to correct the various defects, and to pol<strong>is</strong>h thebronze with files and very fine emery. All th<strong>is</strong> I did myself, byhand; th<strong>is</strong> art<strong>is</strong>tic fin<strong>is</strong>hing takes a very long time and <strong>is</strong> equivalentto beginning the whole work over again. I did not allow anybodyelse to do any of th<strong>is</strong> fin<strong>is</strong>hing work, as the subject of the bronzewas my own special creation and nobody but myself could have carriedit out to my sat<strong>is</strong>faction.”The court’s judgment relied strongly on the intentions of the art<strong>is</strong>t,and the opinions of eminent art experts. It held: “There has been developinga so-called new school of art, whose exponents attempt toportray abstract ideas rather than to imitate natural objects. Whetheror not we are in sympathy with these newer ideas and the schoolswhich represent them, we think the fact of their ex<strong>is</strong>tence and their influenceupon the art world as recognized by the courts must be considered.”The court concluded: “The object now under consideration . . .<strong>is</strong> beautiful and symmetrical in outline, and while some difficultymight be encountered in associating it with a bird, it <strong>is</strong> neverthelesspleasing to look at and highly ornamental, and as we hold under theevidence that it <strong>is</strong> the original production of a professional sculptorand <strong>is</strong> in fact a piece of sculpture and a work of art according to theauthorities above referred to, we sustain the protest and find that it<strong>is</strong> entitled to free entry.”IV. Trials of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>Bearing in mind th<strong>is</strong> Brâncuşi case, let us now consider significantjudgments during the last 25 years of Contemporary <strong>Art</strong>.1987 England: Regina v. Boggs 65In 1984 US art<strong>is</strong>t JSG Boggs 66 was in a diner in Chicago “having adoughnut and coffee and doodling on th<strong>is</strong> napkin . . . sketching a65. Regina v. Boggs, Unreported (Cent. Crim. Ct. London 1987); see also GEOF-FREY ROBERTSON, THE JUSTICE GAME (1999); LAWRENCE WESCHLER, BOGGS: ACOMEDYOF VALUES (1999); Henry Lydiate, The Courtroom as Gallery: The Jury as Spectators,in THE TRIALS OF ART (Daniel McClean ed. 2007).66. James Stephen George Boggs was born in New Jersey, USA, in 1955. Hedropped out of an accountancy course to attend art schools in Florida and NewYork, and settled in London in 1980 to pursue h<strong>is</strong> art practice which, at that time, focusedon graphic representation and interpretation of numerals.

126 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2numeral 1, and gradually began embell<strong>is</strong>hing it. The waitress kept refillingmy cup and I kept right on drawing, and the thing grew into avery abstracted one-dollar bill.” 67 The waitress offered to buy the napkinwork, but Boggs refused. He then asked for h<strong>is</strong> bill—90 cents—and suggested “I’ll pay you for my doughnut and coffee with th<strong>is</strong>drawing.” The deal was done and, as he was leaving, the waitresscalled out “Wait a minute. You’re forgetting your change”, and gavehim a dime. Boggs pract<strong>is</strong>ed many such exchanges over the next twoyears, as payment for h<strong>is</strong> basic expenses, including h<strong>is</strong> rent; and determinedthat drawings of currency alone were not h<strong>is</strong> artwork, ratherthat the whole bartering transaction—including the receipt of legal currencyas change—was the real work. A further new art<strong>is</strong>tic medium—performativity—joins the debate.In 1986 Boggs was living in London and successfully pursuing h<strong>is</strong>art bartering practice, when a journal<strong>is</strong>t suggested that such activitymight be a criminal offence in England unless sanctioned by theBank of England. Boggs therefore “wrote a letter to the Governor ofthe Bank of England, asking him perm<strong>is</strong>sion to go on drawing likenessesof Brit<strong>is</strong>h currency . . . who wrote back denying perm<strong>is</strong>sion,telling me what I was doing was illegal and that I was r<strong>is</strong>king conf<strong>is</strong>cationand arrest.” Boggs continued. He was subsequently indicted. 68The case went to jury trial and he pleaded not guilty to four counts,each alleging reproduction of currency. 69 If the jury determinedthat Boggs had indeed reproduced the Treasury Notes specified inthe indictment, 70 he would be found guilty: these were absolute offencesnot requiring the prosecution to prove any mens rea by theaccused—nor, the prosecution stressed in anticipation of the defence,was it relevant that the accused was an art<strong>is</strong>t whose only intention wasto create art.The defence team’s strategy was to transform the public courtroominto a temporary art gallery by exhibiting an array of artworks, and67. Th<strong>is</strong> and all subsequent quotations from Boggs are taken from direct conversationsin 1986 and 1987 with Henry Lydiate, who was a member of Boggs’ defenceteam; GEOFFREY ROBERTSON, THE JUSTICE GAME (1999); LAWRENCE WESCHLER, note65 supra.68. The Forgery and Counterfeiting Act 1981, c. 45(U.K.), § 18(1) states: “it <strong>is</strong> anoffence for any person, unless the Bank of England has previously consented in writing,to reproduce on any substance whatsoever, and whether or not on the currentscale, any Brit<strong>is</strong>h currency note or any part of a Brit<strong>is</strong>h currency note.”69. Th<strong>is</strong> was decidedly not a prosecution alleging breach of copyright law.70. Four of Boggs’ artworks had been seized and were exhibited to the jury: eachone was a hand-drawn image of one side of a Bank of England currency: £10, £5, andtwo £1 notes.

WHAT IS ART? 127calling expert witnesses to convey one key message for the jury: forgoodness’ sake, th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> art on trial, not mass murder. 71 An array of eminentart experts gave evidence for the defence. They offered the juryearnest, erudite, entertaining, and illuminating d<strong>is</strong>courses about theh<strong>is</strong>torical lineage of art as currency, bartering traditions, the economicvalue of art, the art marketplace, Dada, 72 appropriation of found objectsby art<strong>is</strong>ts, 73 Conceptual<strong>is</strong>m, 74 Performance <strong>Art</strong>, 75 Trompe-l’oeil, 76and Pop <strong>Art</strong>. 7771. The nature and flavour of the defence’s appeal to the jury are captured in thefollowing extracts from defence counsel’s opening address: “The Mona L<strong>is</strong>a <strong>is</strong> not a reproductionofanItalianwoman,andVanGoghdidnotreproducesunflowers...Boggs<strong>is</strong> not an art<strong>is</strong>t of that calibre—and being an art<strong>is</strong>t would in any case be no defencein itself—but if you just look at h<strong>is</strong> drawings you will see that they are not reproductions. . . but an art<strong>is</strong>t’s impression, objects of contemplation . . . they had never beenpassed off as real currency . . . and not even a moron in a hurry would m<strong>is</strong>take thesedrawings for the real thing, they are obviously drawings . . . Boggs <strong>is</strong> no mere reproducer,he’s an art<strong>is</strong>t. You may or may not like what he does. You may find what hedoes of value. You may feel that a Boggs <strong>is</strong>n’t worth the paper it’s drawn on . . . butthat’s not the point. The point <strong>is</strong> that these are original works of art and not reproductionsat all.”72. “Dada <strong>is</strong> the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point forperformance art, a prelude to postmodern<strong>is</strong>m, an influence on pop art, a celebration ofanti-art to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movementthat lay the foundation for Surreal<strong>is</strong>m.” See FRANCIS PICABIA (TRANS. MARC LOW-ENTHAL), I AM ABEAUTIFUL MONSTER: POETRY, PROSE, AND PROVOCATION (2007).73. Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) used found objects and exhibited them as h<strong>is</strong>own artworks from around 1915. He called them Readymades. He challenged traditionalnotions of what art could be, and especially the idea of art being of aestheticor ‘retinal’ value: “My idea was to choose an object that wouldn’t attract me, eitherby its beauty or by its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it,you see.” (Interview, BBC TV, 1966.) Duchamp <strong>is</strong> widely accepted as the most influentialart<strong>is</strong>t of the 20th Century, being the progenitor of Conceptual <strong>Art</strong>. See http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/duch/hd_duch.htm.74. Sol LeWitt (1928–2007) was a progenitor of Conceptual <strong>Art</strong> in the UnitedStates in the 1960s: “In conceptual art the idea or concept <strong>is</strong> the most important aspectof the work. When an art<strong>is</strong>t uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planningand dec<strong>is</strong>ions are made beforehand and the execution <strong>is</strong> a perfunctory affair. Theidea becomes a machine that makes the art.” Quoted from LeWitt’s article Paragraphson Conceptual <strong>Art</strong>, ARTFORUM, June 1967.75. Performance <strong>Art</strong> emerged in the 1950s, and especially the 1960s and 1970s, vianotable v<strong>is</strong>ual art<strong>is</strong>ts such as Joseph Beuys, Vito Acconci, Yves Klein, Yoko Ono,Barbara T Smith, and Carolee Schneemann. Sometimes called “live art”, it eludes prec<strong>is</strong>edefinition, embracing unscripted or unchoreographed events presented with orwithout audience involvement, not necessarily in an art gallery, lasting for any lengthof time. Marina Abramović (1946–) <strong>is</strong> the most widely known performance art<strong>is</strong>t currentlyperforming around the world.76. The ancient technique of “perspectival illusion<strong>is</strong>m” (optical illusion) has beenemployed by art<strong>is</strong>ts since time immemorial.77. Pop <strong>Art</strong> developed in the UK and the U.S. in the 1950s, challenging conventionby appropriating mass-produced v<strong>is</strong>ual images and icons of popular culture from advert<strong>is</strong>ements,comic books, product and packaging designs, telev<strong>is</strong>ion, and film; oftenusing industrial processes to make “multiple originals” such as photo-silkscreenprinting.

128 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2The judge directed the jury that all defence arguments were legallyunsound or irrelevant, and in particular that “th<strong>is</strong> case <strong>is</strong> not about art<strong>is</strong>ticfreedom or freedom of expression or anything of that sort. Youmay have heard it described as a test case. Nothing could be furtherfrom the truth. Th<strong>is</strong> <strong>is</strong> a very narrow and specific case. Please don’tbe deluded into imagining that you’re trying the contemporary art establ<strong>is</strong>hment.It provides no defence whatsoever that the drawings inquestion may be worth more than the originals or, for that matter,that they may in some manner provide the defendant with a principalsource of h<strong>is</strong> livelihood. Whether or not the defendant understood thelaw <strong>is</strong> immaterial.” It was a direction to convict.Engl<strong>is</strong>h juries, especially at the Old Bailey, fiercely resent beingtold by trial judges what to decide. They returned within fifteen minutesa unanimous verdict of not guilty on all counts. Outside in the OldBailey street, members of the jury came out to shake Boggs’ hand andsay “It was the correct verdict. We loved your work.” Indeed: thejury’s judgement had been persuasively guided by Boggs’ art lawyer’sdeep understanding and advocacy of h<strong>is</strong> art bartering practice: at once,conceptual, performative, and graphically representational. 782007/11 USA: Kelley v. Chicago Park D<strong>is</strong>trictIn 1984 Chapman Kelley 79 was granted formal perm<strong>is</strong>sion by theChicago Park D<strong>is</strong>trict to use a parcel of land in Grant Park to createan original artwork: Chicago Wildflower Works, 1984. 80 Twentyyears later the Chicago park authority bulldozed half of Kelley’s siteand replaced h<strong>is</strong> wildflowers with trees, without h<strong>is</strong> knowledge or consent.Kelley filed suit claiming violation of h<strong>is</strong> statutory moral rightsunder federal law: the V<strong>is</strong>ual <strong>Art</strong><strong>is</strong>ts Rights Act 1990 (VARA). 8178. One certain legacy of the case <strong>is</strong> that, soon after their failed prosecution ofBoggs under forgery and counterfeiting (but not copyright) leg<strong>is</strong>lation, the Bank ofEngland for the first time included on its Treasury Notes the international copyrightdeclaration: © THE GOVERNOR AND COMPANY OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND.79. Chapman Kelley was born in San Antonio, Texas, USA, in 1932. He <strong>is</strong> a painter,draftsman, art<strong>is</strong>ts’ rights activ<strong>is</strong>t, art dealer, lecturer and art teacher.80. It compr<strong>is</strong>ed 66,000 sq. ft. into which Kelley planted forty-five different kindsof yellow and purple blooming flowers that were tended by volunteers under h<strong>is</strong> direction,and at h<strong>is</strong> own expense, for twenty years. Kelley described the work as “a sculptureof native flowers, gravel, and steel . . . created with the approval and agreement ofthe Chicago Park D<strong>is</strong>trict.” See http://www.chapmankelley.com/asset.asp?AssetID=37996&AKey=jlbdk6w281. One hundred sixty four countries have now enacted moral rights leg<strong>is</strong>lation,giving creative art<strong>is</strong>ts two basic rights: to claim (or deny) authorship of their work(so-called paternity right); and to object to any mutilation or deformation or othermodification of, or other derogatory action in relation to, their work which wouldbe prejudicial to the author’s honour or reputation (so-called integrity right). The United

WHAT IS ART? 129First tried in 2007/8, 82 the heart of the case lay in the question ofwhether Kelley’s work was an artwork entitled to protection underVARA or whether it was merely landscaped public parkland—andtherefore not entitled to such protection. VARA only gives art<strong>is</strong>tsmoral rights over certain forms of art, specified in the US CopyrightAct 1976. The initial trial judge expressed sympathy for, and understandingof, the development in the late 20th century of radicallynew art practices and forms, commenting: “There <strong>is</strong> a tension betweenthe law and the evolution of ideas in modern or avant-garde art; theformer requires leg<strong>is</strong>latures to [classify] art<strong>is</strong>tic creations, whereasthe latter <strong>is</strong> occupied with expanding the definition of what we acceptto be art. While Andy Warhol’s suggestion that ‘art <strong>is</strong> whatever youcan get away with’ <strong>is</strong> too nihil<strong>is</strong>tic for the law to accommodate, neithershould [moral rights laws] be read so narrowly as to protectonly the most revered work of the Old Masters. In other words, the‘plain and ordinary’ meanings of words describing modern art arestill slippery.” 83 And so the court ruled that Kelley’s work was inlaw a sculpture, or three-dimensional artwork; and also a paintingthat “corralled the variegation of wildflowers in bloom into pleasingoval swatches”. Kelley was rightly pleased with th<strong>is</strong> enlightened initialjudgment, commenting: “Th<strong>is</strong> ruling redefines legally what can be fineart, what it can be made of, and that art<strong>is</strong>ts themselves make thesedec<strong>is</strong>ions.”However, not all artworks are entitled to copyright and thereforemoral rights protection; only those that pass the legal ‘originality’test required by copyright law (of most countries, including the US),which courts determine in each case. In Kelley’s case the trial courtexpressed difficulty in understanding what was original about h<strong>is</strong>work because he was not “the first person to ever conceive of and expressan arrangement of growing wildflowers in [an] ellipse-shapedenclosed area”. 84 The judge further ruled that Kelley’s work was‘site-specific’ and, as such, would not be entitled to moral rights protection(even if it had passed the legal ‘originality test’) because UScase law had decided in 2006 that site-specific artworks—whose integ-States introduced statutory moral rights into federal law through VARA, following theU.S. government’s joining the Berne Convention in 1989. VARA amends the federalCopyright Act 1976 by inserting moral rights of paternity and integrity, but only forliving v<strong>is</strong>ual (not other creative) art<strong>is</strong>ts.82. Kelley v. Chicago Park D<strong>is</strong>trict, No. 04 C 07715, 2008 WL 4449886 (N.D. Ill.,Sept. 29, 2008), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011).83. Id. at6.84. Id.

130 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2rity would be damaged by their removal from a specific site—wereoutside the scope of moral rights protection. 85 Kelley did achieve apyrrhic victory when the court ruled on a separate contractual claimthat the park authority should have given him at least 90 days noticeof its intention to remove half of h<strong>is</strong> work—but awarded him nominaldamages of only $1. Kelley appealed against the court’s rulingsagainst him, particularly that h<strong>is</strong> work failed to sat<strong>is</strong>fy the legal ‘originality’test.In 2011 the appeal court 86 reversed the initial court’s judgmentabout the classification of the work under copyright leg<strong>is</strong>lation, decidingthat an artwork “must actually be a painting or sculpture. Not metaphoricallyor by analogy, but really . . . Authors of copyrightableworks must be human; works owing their form to the forces of naturecannot be copyrighted . . . and are not authored or fixed.” 87 Fixation <strong>is</strong>a further requirement of copyright laws in many jur<strong>is</strong>dictions beyond,and including, the US, namely: that an original work must be recordedor fixed in a stable material form—not be transient or ephemeral—soas to be capable of being copied in some material form, and thus qualifyfor copyright protection. The appeal court ruled that “the law musthave some limits; not all conceptual art may be copyrighted”; and thatChicago Wildflower Works was created more by nature than by itsconceiver/planner, and compr<strong>is</strong>ed “inherently changeable organ<strong>is</strong>ms”. 88However, the appeal succeeded on two key <strong>is</strong>sues: that the trialjudge was wrong to hold that the work failed the copyright originalitytest; and that art<strong>is</strong>ts’ statutory moral rights did not apply to site-specificworks, in particular that “an all-or-nothing approach to site-specific artmaybeunwarranted...site-specificart...likeanyothertypeofart...can be defaced or damaged.” 89 That latter dec<strong>is</strong>ion has been hailed as animportant judgment by art<strong>is</strong>ts’ rights campaigners who had, since 2006,sought to reverse the so-called Phillips rule 90 denying art<strong>is</strong>ts’ statutorymoral rights to their site-specific artworks. At the same time, the appealcourt’s judgment took a narrower and more traditional view of what85. Phillips v. Pembroke Real Estate, Inc., 459 F.3d 128 (1st Cir. 2006).86. Kelley v. Chicago Park D<strong>is</strong>t., 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011), cert. denied, 132S.Ct. 380 (2011).87. Th<strong>is</strong> ruling was made by the appeal court of its own motion, not followingarguments advanced by the parties in the appeal.88. The appeal also failed on the contract claim: the court held that the ChicagoPark D<strong>is</strong>trict official who had informally allowed Kelley to continue use the parkland (after h<strong>is</strong> formal permit had expired) had no legal capacity or authority to do so.89. Kelley v. Chicago Park D<strong>is</strong>t., 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011), cert. denied, 132S.Ct. 380 (2011).90. Phillips, 459 F.3d at 143.

WHAT IS ART? 131art could be (for copyright purposes) than views expressed by contemporaryart<strong>is</strong>ts.2010 Germany: VG Bild-Kunst v. Museum Schloss Moyländer 91In 1964 German art<strong>is</strong>t and philosopher Joseph Beuys 92 gave an improv<strong>is</strong>edtwenty minute performance transmitted on Germany telev<strong>is</strong>ionchannel Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, which he called MarcelDuchamp’s Silence Is Overrated. The performance was not tapedbut Beuys allowed the renowned art documenter Manfred T<strong>is</strong>cher 93to photograph it. T<strong>is</strong>cher’s 19 photographs are the only record ofBeuys’s unique live performance; they remained unpubl<strong>is</strong>hed until exhibitedat Museum Schloss Moyländer 94 in 2008. In 2009 that exhibitionwas curtailed by a temporary court order requiring T<strong>is</strong>cher’s photographsto be taken down, pending a full trial of a legal claim that theimages violated Beuys’s copyright and moral right of integrity.The lawsuit was brought against the museum by VG Bild-Kunst,Germany’s art<strong>is</strong>ts’ copyright collecting society, acting on behalf ofEva Beuys who inherited her husband’s intellectual property rightson h<strong>is</strong> death in 1986. The trial ended in September 2010 when theHigher Regional Court in Düsseldorf gave its final judgment 95 confirmingthe claim, and permanently ordering T<strong>is</strong>cher’s images not tobe exhibited by the museum.Beuys’s 1964 performance was improv<strong>is</strong>ed (and therefore had notbeen performed or fixed in a material form via film or tape beforethe live broadcast) and the only record of it <strong>is</strong> T<strong>is</strong>cher’s nineteen photographs.Nevertheless, the court appears to have ruled that Beuys’s91. Unreported. The facts of th<strong>is</strong> case considered in th<strong>is</strong> section are drawn from anunauthor<strong>is</strong>ed Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation of the judgment: the court’s written judgment in theGerman language was publ<strong>is</strong>hed and handed down September 29, 2010 by the D<strong>is</strong>trictCourt of Dusseldorf, Chamber: 12 Civil Div<strong>is</strong>ion, Application Number: 12 O 255/09.92. Joseph Beuys (1921–1986) was a German art<strong>is</strong>t and art theor<strong>is</strong>t, widely recogn<strong>is</strong>edas one of the most influential art<strong>is</strong>ts of the 20th century. A progenitor of Performance<strong>Art</strong> in the 1960s, he also created a large body of 2D and 3D artworks and installations.He developed an “extended definition of art” including especially h<strong>is</strong>“social sculpture” aimed at influencing society and politics. The first and only comprehensiveretrospective exhibition of h<strong>is</strong> works during lifetime was at the GuggenheimMuseum, New York in 1979, which sealed h<strong>is</strong> international reputation.93. Manfred T<strong>is</strong>cher lived from 1925–2008.94. Located within Moyländ Castle, Bedburg-Hau, Germany, Museum SchlossMoyländer holds the world’s largest collection of Beuys’s works (6,000); and <strong>is</strong> anexample of an increasing number of modern and contemporary art galleries exhibitingrecords/documents of “non-object based” artworks.95. An author<strong>is</strong>ed Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation of the judgment <strong>is</strong> not available; the court’swritten judgment in the German language was publ<strong>is</strong>hed and handed down September29, 2010 by the D<strong>is</strong>trict Court of Dusseldorf, Chamber: 12 Civil Div<strong>is</strong>ion, ApplicationNumber: 12 O 255/09.

132 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2entire performance—though transient and unfixed—was an artworkentitled to copyright and moral rights protection, and that the exhibitionof T<strong>is</strong>cher’s freeze-frame-like images was an unlawful adaptationof the entire work of Performance <strong>Art</strong>. 96From an unauthor<strong>is</strong>ed Engl<strong>is</strong>h translation of the judgment andmedia reports 97 of the case, the court’s reasoning appears to includethe following findings:• circumstantial evidence in the form of an assessment by expertscan prove the ex<strong>is</strong>tence of an entire performance, from whichthe court could gain an overall impression and find that an intellectualcreation of the art<strong>is</strong>t was made;• improv<strong>is</strong>ed actions are protected by copyright when they reachthe required threshold of originality;• the essence of th<strong>is</strong> art form would be frustrated if art activitieswere denied the status of art on the grounds that they were essentiallybased on improv<strong>is</strong>ation;• German copyright law allows new forms of art beyond the boundariesof traditional art forms to be protected, and such protectioncovers the work as a whole;• it <strong>is</strong> not necessary for a work to be recorded permanently so that it<strong>is</strong> capable of being reproduced;• the entire performance lasted at least 20 minutes: the 19 photographsare only snapshots of the work and, thereby, transform adynamic art process into stas<strong>is</strong>;• the museum exploited an adaptation of the entire performance,without perm<strong>is</strong>sion of the legal successor to the creator, andwas contrary to copyright law. 98The court’s judgment was unprecedented—not only in Germany,but worldwide—in holding that unrecorded/undocumented/unfixedPerformance <strong>Art</strong> <strong>is</strong> capable of being protected by copyright and moralrights laws. Equally significant was the court’s demonstrable understandingand embracing of an avant-garde contemporary art form that96. Performance <strong>Art</strong> events are essentially transient, often though not always improv<strong>is</strong>ed,and infrequently scripted or recorded. In recent times, Performance <strong>Art</strong>events and projects have been scripted and/or recorded by the art<strong>is</strong>t/performer/author,which not only helps to meet the ‘fixation’ requirement of intellectual property rightslaws but also enables such secondary ‘documents’ to be sold by the art<strong>is</strong>t in the artmarket place.97. See The <strong>Art</strong> Newspaper, Nov. 2010, at 13.98. The trial court’s judgement <strong>is</strong> subject to appeal by the Museum at the time ofwriting, and <strong>is</strong> expected to be heard during 2012.

WHAT IS ART? 133could not have been contemplated by the promulgators of Germancopyright and moral rights laws.2008 England: Haunch of Ven<strong>is</strong>on v. Her Majesty’s Comm<strong>is</strong>sionersof Revenue and Customs 99In December 2008 a VAT 100 and Duties Tribunal in London tried acase that was strikingly similar to Brancusi’s eighty years earlier. Theartworks concerned were video installations by Bill Viola 101 and lightworks by Dan Flavin 102 that had been d<strong>is</strong>mantled into their constituentparts for shipping. <strong>Art</strong> dealers Haunch of Ven<strong>is</strong>on had imported theworks into the UK from the US, and had been required by Her Majesty’sRevenue and Customs (HMRC) to pay import taxes on thebas<strong>is</strong> that they were not artworks, but projectors and light fittings. Accordingto relevant EU and UK import laws, importers of artworks intothe EU are required to pay a reduced VAT rate of 5% (of the works’market value plus insurance and transport costs). Importers of projectorsand light fittings into the EU via the UK are required to pay the normalVAT rate of (then) 17.5% plus Customs Duty of 3.7%. Curiously,HMRC based its assessment of the value of these so-called ‘projectorsand light fittings’ on their market value as artworks.In order to succeed in its appeal against the customs levy, Haunch ofVen<strong>is</strong>on needed to persuade the tribunal that the constituent partsshould be treated as artworks, in particular as ‘sculpture’ within themeaning of EU customs law classifications of imported goods and materials103 ; and called expert witnesses to give evidence in support. Thetribunal was persuaded by th<strong>is</strong> evidence, holding that the meaning of‘sculpture’ had been significantly enlarged and developed by art<strong>is</strong>ts99. Haunch of Ven<strong>is</strong>on Partners Limited v. Her Majesty’s Comm<strong>is</strong>sioners of Revenueand Custom, (2008) London Tribunal Centre (Eng.), http://www.taxbar.com/Haunch_of_Ven<strong>is</strong>on_Trib.pdf.100. Value Added Tax<strong>is</strong> the UK name for general sales tax, which applies throughoutthe European Union at different rates determined by each EU Member State.101. Bill Viola (1951–) was born in Queens, New York. He <strong>is</strong> an internationallyrenowned contemporary art<strong>is</strong>t whose work employs audio-v<strong>is</strong>ual digital technology.Viola <strong>is</strong> a leading practitioner of Video <strong>Art</strong>, which uses moving images and/orsound as components that are often, but not always, installed in art galleries and museums.Recent auction sales have real<strong>is</strong>ed between US$55,000 and US$600,000.102. Dan Flavin (1933–1996) was born in Jamaica, New York. He <strong>is</strong> an internationallyrenowned modern art<strong>is</strong>t whose work usually employed fluorescent lighttubes/bulbs/fittings to form sculptural objects, or as part of an art installation. TheDan Flavin <strong>Art</strong> Institute in Bridgehampton, New York, exhibits an extensive permanentcollection of h<strong>is</strong> works. Recent auction sales have real<strong>is</strong>ed between US$170,000and US$1,700,000.103. Classification 9703 of the Combined Nomenclature in Council Regulation2658/87/ 1987 O.J. (L 256) (EEC).

134 J. INT’L MEDIA &ENTERTAINMENT LAW VOL. 4,NO. 2during the Modern <strong>Art</strong> era to embrace the materials at <strong>is</strong>sue. And thetribunal specifically held that it would be “absurd to classify any of theworks as components ignoring the fact that the components togethermake a work of art”. Undoubtedly the tribunal also had strong regardto the reasoning of the judge in the Brâncuşi judgment.And there the matter rested, until in September 2010 EuropeanComm<strong>is</strong>sion Regulation 731/2010 came into force, specifically reversingthe London Tribunal’s judgment on Viola’s and Flavin’s works asart, and classifying them as ‘components’ for which no reduced VATimport rate <strong>is</strong> allowed. In relation to Viola’s work, th<strong>is</strong> curious Regulationstates: ‘classification as a sculpture <strong>is</strong> excluded, as none of theindividual components or the whole installation, when assembled, canbe considered as a sculpture . . . It <strong>is</strong> the content recorded on the DVDwhich, together with the components of the installation, provides forthe “modern art” . . . Consequently, the components of the installationare to be classified separately . . . the video reproducing apparatus . . .the loudspeakers. . . . the projectors . . . and the DVDs.’ As for Flavin’slight works, the Regulation equally curiously states: ‘classification as asculpture <strong>is</strong> excluded, as it <strong>is</strong> not the installation that constitutes a“work of art” but the result of the operations (the light effect) carriedout by it. Classification . . . as a collector’s piece of h<strong>is</strong>torical interest . . .<strong>is</strong> [also] excluded ...Ithasthecharacter<strong>is</strong>tics of lighting fittings andthe product <strong>is</strong> therefore to be classified as wall lighting fittings.’Why did the European Comm<strong>is</strong>sion 104 go to such elaborate lengthsto overturn the judicial dec<strong>is</strong>ion of a London VAT Tribunal in relationto a relatively small amount of contested UK/EU import tax (£36,000)in relation to artworks? Pierre Valentin, the art lawyer who representedHaunch of Ven<strong>is</strong>on at the tribunal, recently used Freedom of Informationleg<strong>is</strong>lation to obtain copies of relevant European Comm<strong>is</strong>sion recordsto d<strong>is</strong>cover why. He explained 105 : “within weeks of the London[Tribunal] dec<strong>is</strong>ion, the <strong>is</strong>sue was on the agenda of the European Comm<strong>is</strong>sion’sCustoms Code Committee in Brussels. Several MemberStates reported that their tax authorities had considered the <strong>is</strong>sue ofvideo art previously. The meeting was told that in two Members States(the UK and the Netherlands), a VAT Tribunal had held that video installationsshould be classified as sculptures. By April 2009, without104. The European Comm<strong>is</strong>sion <strong>is</strong> the executive arm of the European Union, ofteninformally called the “European Government”. It has leg<strong>is</strong>lative powers to make Regulations,which are direct forms of law that have binding legal effect on all EU MemberStates.105. In a feature article in The <strong>Art</strong> Newspaper, Jan. 2011.

WHAT IS ART? 135apparent further consultation, the Committee decided that ‘a draft regulationwill be prepared for a future meeting. Th<strong>is</strong> will overturn theUK [and Dutch] National Court dec<strong>is</strong>ions’. Th<strong>is</strong> eventually becameEU Regulation 731/2010, which Valentin argues <strong>is</strong> “a patently absurdpiece of leg<strong>is</strong>lation. Adopted behind closed doors, without an apparentunderstanding of the subject matter, it reverses two national judicialdec<strong>is</strong>ions that both ruled that video installations should be classifiedas art. No judge had decided the <strong>is</strong>sue in any other way. There wasno need for the Regulation, which <strong>is</strong> contrary to the jur<strong>is</strong>prudenceof the European Court of Justice”. 106 Because th<strong>is</strong> Regulation only addressesthe specific Viola and Flavin ‘components’ imported into theEU by Haunch of Ven<strong>is</strong>on, it remains moot whether it embraces importationinto the EU of component parts of all d<strong>is</strong>assembled artworks.V. Star WarsLet us finally consider the latest landmark judgment on “<strong>What</strong> <strong>is</strong>art?” Handed down by the UK Supreme Court in July 2011, and popularlyknown as the Star Wars case, it was brought by George Lucasand h<strong>is</strong> companies claiming copyright infringement against a UKdesigner-maker named Andrew Ainsworth. There was a sequence offour judicial dec<strong>is</strong>ions; given by:• Federal US Court in 2006: a default judgment for Lucas 107• UK High Court in 2010: finding for Ainsworth 108• UK Court of Appeal in 2010: finding for Ainsworth 109• UK Supreme Court in 2011: finding for Ainsworth. 110The UK Supreme Court was required to determine the legal meaningof sculpture in UK copyright law. The significance of th<strong>is</strong> dec<strong>is</strong>ion<strong>is</strong> far-reaching: not only because UK’s judicial system <strong>is</strong> based uponthe common law principle of precedent, whereby th<strong>is</strong> dec<strong>is</strong>ion andits rationale should be followed by all UK courts trying the same ora similar legal <strong>is</strong>sue; but also because UK Supreme Court judgmentsare respected by, and potentially influential upon, courts of record incommon law jur<strong>is</strong>dictions around the world. Any such influence willdepend upon, and be directly proportionate to, the nature and quality106. Id..107. Lucasfilm Ltd v. Shepperton Design Studios Ltd., No. CV05-3434 RGKMANX, 2006 WL 6672241 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 26, 2006).108. Lucasfilm Ltd & Ors v Ainsworth & Anor, [2008] EWHC 1878 (Ch), (Eng.and Wales High, Chanc.)109. [2009] EWCA Civ 1328, [2010] Ch 503110. Lucasfilm Ltd and others v. Ainsworth and another, [2011] UKSC 39