The Bridge - Mercy Corps

The Bridge - Mercy Corps

The Bridge - Mercy Corps

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

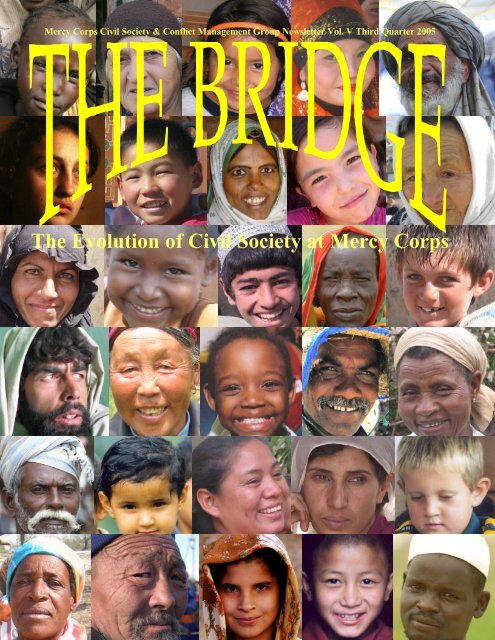

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>IntroductionThis issue of the <strong>Bridge</strong> examines the development ofCivil Society at <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>. Beginning with itsfounding in 1981, through the establishment of theHuman Rights Desk in 1989 and most recently withthe merger with the Conflict Management Group, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>has sought to empower people to improve their lives and communities- in effect to “be the change.” Our Civil Society vision,with the end goal of secure, productive and just communities,underpins all of our programs, permeates our culture and establisheshow we should enact this change.In this issue: CEO Neal Keny-Guyer provides insight about hisvision for the organization; we recognize the important civil societycontributions by <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ co-founders, Dan O‘Neilland Ells Culver; President Nancy Lindborg describes the evolutionof the development of civil society at <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; formerDirector of <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ Human Rights Desk, LowellEwert writes of the grounding of civil society in the humanrights movement; Ethiopia Country Director Tom Hensleighdescribes the advances made as a result of the Civil Society InstitutionalStrengthening Grants; Program Manager DaynaBrown highlights our recent merger with the Conflict ManagementGroup. In addition, we present feedback from a survey onchanges to the mandala and provide a brief review of the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights.In the past year the Civil Society Team has transitioned into theCivil Society and Conflict Management Group and has expandedfrom three to eleven members. We have incorporated formermembers of the Conflict Management Group as well as the ScottishNGO Just World Partners. <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> has acquired threeDFID programs from Just World Partners. <strong>The</strong>se include a programin Nepal that addresses child trafficking into prostitution, ayouth civic engagement program in East Timor and a radio programin Kiribati that allows citizens of outer islands to raise theirconcerns to policy makers. Our current team consists of:- Seema Tikare (Cambridge), Director and lead point for overviewof sectoral and regional portfolios, and Azerbaijan and India,with experience and interest in good governance, publicsector accountability, transparency, urban poverty and municipalservices.- Ruth Allen (Cambridge), lead point for Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudanand Uganda with experience and interest in gender and peaceconflictassessments.- Dayna Brown (DC), lead point for the Balkans, Liberia, Niger,Zimbabwe, and Somalia with exp erience and interest in conflictsensitive programming.- Scott Dubin (Cambridge), provides general support for team inCambridge with experience and interest in rights based approaches.- Silas Everett (Manila), lead point for Nepal, Pakistan, Indonesiaand Sri Lanka with experience and interest in good governanceand advocacy strategies- Ted Johnson (Cambridge), lead point for negotiation trainingswith particular focus on WHO and other institutional clientswith experience and interest in interest-based negotiation.-Emmy Lang-Kennedy (Portland, Landrum Bolling Fellow), exp e-rience and interest in <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>, youth and HIV/AIDS programming.- Arthur Martirosyan (Cambridge), lead point for Caucasus,Central Asia, and West Bank/Gaza with experience and interestin adaptive leadership, scenario planning and coalition building.- Dory McIntosh (Edinburgh), lead point for Kiribati, East Timor,and Guatemala, with particular focus on DFID and other Europeandonors/agencies/programs with experience and interest inDFID programs, rights based approaches and local partnerships.- David Steele (Cambridge), lead point for Iraq and Afghanistanwith experience and interest in religion and conflict.- Michael Szporluk (Portland), lead point for Jordan and TANprogram in Mongolia and Guatemala with experience and interestin inclusion and disability, local partners and localization.Over the next year the Civil Society and Conflict ManagementGroup will continue to work on improving the capacity ofagency staff, partners and beneficiaries to work on strengtheningcivil society. We will focus on integrating conflict managementresources to enable our staff in the field to work on improvingrelations between local stakeholders and to strengthenthe enabling environment, on publishing more about the bestand most innovative field practices, and on making our technicalsupport more user-friendly.Please contact us for additional information and support.<strong>The</strong> Civil Society andConflict Management GroupCivil society is both the process and the result of the civic, public andprivate sectors interacting in a way that is participatory, accountableand includes mechanisms for peaceful coexistence, all of whichcontributes to the creation of more secure, productive, just andhealthy communities. <strong>The</strong> function of a healthy and vibrant CivilSociety is to empower people to participate in economic, politicaland social activities and in the decisions that affect their lives.Drawing from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> has identified the following principles as integral to afunctioning Civil Society: Participation, Accountability and PeacefulCoexistence.3

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>Proposed Vision for ChangePublic SectorSectorPrivateParticipationSecure, Productiveand JustCommunitiesAccountabilityPeacefulCoexistenceCivic Sector<strong>The</strong> August 30 th edition of <strong>The</strong> Globe requested feedbackon changes to the mandala. Here we present ourproposed changes based on this feedback and discussionby the CS and CMG. Feedback from staffindicated the mandala is seen more as a visual representation ofMC’s mission and the end-state toward which we work. <strong>The</strong>refore,<strong>The</strong>ory of Change could be replaced by Vision forChange.Private Sector, Civic Sector, and Public Sector have been usedto describe the three central actors. We see Civic Sector as abetter option than Civic Organizations or Civil Society. <strong>The</strong>term Civic Organizations is too limiting. Since our definition ofcivil society remains, “the process and the result of the interactionsbetween all actors”, it would be confusing, to have CivilSociety appear as a stakeholder. We believe that Private Sectoris broader than Business and is a term that is understood andused by partner organizations, institutions and beneficiaries inthe field. To be consistent with these changes Public Sectorhas been used in place of Government.Peaceful Coexistence has replaced Peaceful Change. While theother parts of the mandala describe MC’s vision of the end-statetoward which the agency works, Peaceful Change was the onepart that still referred to a process. To be consistent the mandalashould read Peaceful Coexistence, which also implies anend-state for our programming.Sustainable Livelihoods has replaced Economic Opportunities.This change came in response to the proposed addition of SustainableResource Management. <strong>The</strong> term Sustainable Liveli-hoods addresses a weakness some saw with the lack of responsiblemanagement or equitable distribution in Economic Opportunity,and affirms our commitment to enhancing the ability ofcommunities to sustain themselves responsibly. SustainableLivelihoods encompasses Sustainable Resource Managementand economic opportunity.Good Governance has replaced Political Development. GoodGovernance is clearer and implies access to information, transparency,accountability, and trust between community membersand their elected officials.Civic Engagement has replaced Vibrant Civic Sector. Peoplefelt Vibrant Civic Sector was redundant and that citizens andcommunities were not sufficiently represented as actors or contributorsin the external environment. Civic Engagement paystribute to the capacity and ability of individuals to play an integralrole in shaping their community.Along with these changes we would like to propose the additionof healthy to the mandala’s center. We believe that healthyshould be broadly understood to signify more than the physical,social and mental well-being of the individual. Indeed, it shouldrefer to the social, cultural, and political health of communitiesas well. One concern with adding healthy is its implication for<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ mission statement. Adding healthy would requirean amendment to our mission of “building secure, productiveand just communities”.<strong>The</strong> team will take this last recommendation to the Senior ManagementTeam for their review and consideration.4

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong><strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ Co-FoundersDan O’NeillDan O’Neill established Save the Refugees Fund in1979 in response to the Cambodian Killing Fieldsand motivated by the moral duty he felt after theUnited States’ involvement in the region. Alongwith providing basic relief services such as food, shelter, medicalcare, and clothes to refugees Dan and others delivered riceand seed rice to Cambodian farmers.On returning to the United States Dan met Ells Culver at a conferencefor the Association ofEvangelical Relief and DevelopmentOrganizations, whereDan represented Save theRefugees Fund and Ells representedFood for the Hungry,where he served as Vice-President. <strong>The</strong>ir shared commitmentto provide more sustainableaid and developmentto poor countries united thetwo men around a single purpose.From this commitmentand shared passion <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> was founded in 1981.As <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> has grownDan has continually pushedthe organization to addressthe root causes of conflictand disaster. He saw thisneed first hand while in Beirutin 1982 during the Lebanese Civil War and the Israeli invasion.As he witnessed the war’s aftermath, Dan became convinced ofthe necessity of addressing conflict management since thework, even of strong relief agencies, is compromised whenconflict erupts. He led <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> to discuss the role of ruleof law, government accountability, sustainable economicdevelopment, and conflict management – all key elements ofcivil society. Dan’s work has also emphasized the importanceof relying on local staff to help build bridges to localcommunities. Without this component <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ programswould be neither effective nor sustainable.<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ President until 2004, Dan remains the public faceof the agency. This year he addressed 250,000 demonstratorsat the G8 summit in Scotland and attended the 10th-anniversarymemorial for the massacres at Srebrenica, which occurred duringthe conflict in Bosnia.Dan O’Neill and Ells Culver during a banquet at the World LeadershipConference in Portland, Oregon. (<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)Ells CulverWhile President of <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> from 1984 to1993 Ells directed the expansion of the organization’srelief and development work into Asia,Africa and Central America. He guided <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> towards focusing on helping people to build secure, productive,and just communities, the mission of our organization,the ultimate goal of our civil society strategy, and the centerpiece of our vision for change. Ells evaluated crises and beganprograms in many fragile partsof the world including Lebanon,the West Bank, Iraq, Pakistan,and Ethiopia.outside world.From 1994 until his death inAugust 2005 at age 78, Ellsworked as <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ SeniorVice President where hecontinued to open doors otherwiselocked. His most recentwork focused on EastAsia, and North Korea in particular,where he helped breakdown barriers for partnershipsthat would have been impossibleotherwise. Ells saw a largerole for U.S. non-governmentalorganizations in opening uprelations with North Korea andin providing a window to theAlong with supplying food aid and medical support, under Ells’leadership <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> has assisted in the redevelopment ofNorth Korea’s orchards. Apple, peach, and pear productionthrived 50 years ago but had seen a drop in production due tothe lack of new inputs. To fill this need <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ AppleTree Project has supported the planting of over 70,000 trees.Ells also helped found the National Committee for North Koreawhich works toward reconciliation between North Korea andthe United States by advancing, promoting. and enhancing engagementbetween citizens of the two nations. Ells saw theneed to increase understanding and exchange of knowledgebetween these two countries. He led numerous delegationscomposed of U.S. citizens to North Korea to foster a better relationship.Ells’ leadership and vision led <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> to becomewhat it is today.5

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>6Civil Society at <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>:<strong>The</strong> Continuing Journey<strong>The</strong> Founding Vision of Peace and Social Justice /1979 - 1989: <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> co-founders Dan O’Neilland Ellsworth Culver each brought a strongcommitment to peace and social justice, which formedthe deep bedrock of their fledgling organization. Initiallygalvanized by the killing fields of Cambodia, Dan and Ellsbroadened their focus to providing assistance in other areas ofconflict, including Central America, the Middle East, Pakistanand Afghanistan. In addition to providing relief assistance,they decided to organizedelegations ofpolicymakers, religiousleaders and otherinfluentials to witnessfirsthand the suffering thatresulted from broadinjustice and conflict. From1979 to 1989, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>sponsored a series ofdelegations -- many led bytheir close friend LandrumBolling -- primarily to theMiddle East in an effort tocontribute to the peacefulresolution of theseconflicts.<strong>The</strong> Human Rights Desk /1989 – 1993: However, in1989, Ells decided thedelegations weren’t enoughAhmeda Rahbar, a local school teacher, talks about the challenges facingeducation during an initial needs assessment in Michurin village, Tajikistan.(Colin Spurway/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)to address the deeper roots of injustice and lack of rights. Herecruited a dedicated young human rights attorney, LowellEwert, to establish and run a human rights desk at <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.Lowell drew upon his rule of law and advocacy experiences toform the Human Rights program. Under his early guidance, theHuman Rights program began to explore how to ground reliefand development activities within the framework of humanrights. <strong>The</strong> Universal Declaration of Human Rights wasparticularly influential with its inclusion of social and economicrights.One early example of this experiment was our work in CentralAsia under a 1992 USDA food monetization grant. During thisperiod, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> provided support for the draft nationalconstitution, promoted the establishment of a law school andsponsored human rights trainings in Kazakhstan. It was alsothe first time the <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> deliberately sought to fund adiverse group of civil society organizations, with about 30 smallgrants given in the first year of the program. Other early effortsincluded facilitating repatriation and the rebuilding ofmultiethnic communities in Lebanon following the civil war,organizing agricultural cooperatives in the Philippines, andbuilding the capacity of the Displaced Women’s Association inSudan. All of these programs aimed to promote peace andconflict resolution, and to build citizen participation – elementsthat later would be embodied in the Civil Society Framework.A pivotal moment for the emerging program was the publicationin 1992 of a Human Rights Watchreport that quoted Amartya Senthat “[E]very single famine inmodern history has been caused,at least in significant part, bysystematic abuse of humanrights.” 1 Sen, a Nobel-prizewinning economist, furtherinspired our early work by hiswritings on the role of democracyand an open society. Heobserved that the presence ofsocial justice, the open flow ofinformation and equity enabledsocieties to mitigate thedevastation caused by faminesand the destruction caused byearthquakes and other naturaldisasters. <strong>The</strong>se ideas helpedinfuse our programs with newdirection.<strong>The</strong> Shift to Civil Society Terminology: At the time, however,<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ Human Rights program faced resistance mainlydue to concern about the political implications on a conceptuallevel, both inside the organization and with most colleague reliefand development organizations. At some early conferences,<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> encountered serious opposition to its growingfocus on human rights from colleague agencies.As a result, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> shifted its language from human rightsto the term “civil society”. This shift was not seen asconceptual or programmatic, but rather reflected a pragmaticdesire to avoid the lightning rod of the human rights language.It also reflected a desire to focus more specifically on how we,as an operational relief and development agency, could mosteffectively make a difference in the communities where we work.It signified a more realistic and farther-reaching assessment ofthe role <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> could play to promote human rights.Evolution of a Concept: In 1996, Lowell and I attended a

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>conference sponsored by the Washington DC Society forInternational Development in which the definition of “civilsociety” was discussed. Lowell had already identified abewildering 72 different definitions. At the time, the conceptwas still very loose and broad – seemingly a perfect vehicle forevolving our own sense of this concept.USAID awarded <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> the first of two three-yearmatching grants in 1996 to explore more deeply this civil societyapproach. <strong>The</strong>se grants became the engine that drove forwardthe concept of civil society throughout the agency, engaging abroad cross section of people to help develop the specific ideasthat underpinned our civil society approach. A series ofworkshops brought people together, including many initialskeptics, who contributed to the evolution of what has becomeknown as the civil society mandala. <strong>The</strong> grants also funded aseries of pilot programs in Bosnia, Lebanon, Tajikistan,Guatemala and Honduras to test these ideas on the ground.Under the successive direction of Kim Maynard, Kim Johnstonand Mara Galaty, these grants yielded enormous results andlearnings. We struggled with the question of whether civilsociety was a sector or an approach that informed everythingwe did, only to realize the answer was a simple “Both.”We refined our definition of civil society as both a process anda desired endstate in which civic society – defined as all theways in which individuals come together for the power ofcollective action – interacts with the private business sector andgovernment at all levels. This interaction must have broadinclusive participation, accountability in all directions andmechanisms for peaceful change to enable communities to bejust, secure and productive.Our <strong>The</strong>ory of Change: In the wake of our massive Kosovoresponse in 1999-2000, we organized a summit meeting outsidePortland in July 2001 to examine “Comprehensive AssistanceStrategies: Exploring Developmental Relief, NavigatingTransitions and Working in a Conflict-ridden World.” Wepersuaded the late, brilliant Marc Lindenberg to facilitate, withhopes that his outside perspective and intellect would help usas we grappled with increasing challenges in the world.<strong>The</strong> realization that our civil society framework was ourunderlying theory of change strongly emerged from thatworkshop. It embodied both our commitment to human rights,to peace and social justice, as well as a diagnostic for how wemight be able to contribute concretely to that vision of “just,secure and productive communities.”<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> has long focused on working in countries intransition, based on the firm conviction that despite the chaosof conflict and economic collapse, there are also possibilities forcontributing to positive change. We don’t aspire to remain incountries for years and years, but rather to support individualsand communities in their quest for stability, economicopportunity and dignity.All our program sectors contribute to the development of avibrant civic sector that can begin the process of engaging withprivate business and government at all levels. With the toolsfor this engagement, with the health to do so and with thelivelihoods that enable families to support themselves withdignity, communities have the possibility of a more peaceful andpositive future.<strong>The</strong> Challenge Ahead: During the last decade, there has beensignificant movement on all these fronts within our entirecommunity. Civil Society has been defined to mean primarilythat civic sector rather than the more holistic vision weidentified. While the civic sector is quite frequently our entrypoint into a community, increasingly it is not the only sector wetarget. In Kosovo for example, the team has moved its entrypoint to the municipal governments, but with the same basicgoal of bringing accountability, participation and mechanismsfor peaceful change to the interactions with civic and businesssectors. However, the totality of what we mean by civil societyhas not always been effectively communicated with a broaderaudience. We are challenged to ensure we have a crisper, morecomplete way of communicating our approach.A human rights based approach has become quite acceptableand has spawned a broad dialogue. Because of our vocabularyshift in the early nineties, we have not been as engaged in thisdialogue, which has focused to some extent on linking localcommunities with international legal instruments to which theirgovernments are signatory. We have based our civil societyframework on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, butwe have broadly interpreted the promotion of those rights in thefield. We are challenged by the need to plug more robustly intothis dialogue and bring our valuable experiences to the table.We have sought to deepen yet again our understanding of howto address conflict effectively and have merged with ConflictManagement Group to add tools, approaches and improvedunderstandings to our programs. We are challenged to ensurethis merger ensures a significant difference in how our fieldprograms address conflict.Finally, the Civil Society mandala is truly a representation of ourtheory of change, of how we can work with communities andpromote their efforts to create positive and lasting change wherethey live. Our collective experiences have supported the earlyvision of Dan and Ells. We cannot only respond to famine anddisaster, but must also look carefully at how we can facilitateand support the change that individuals and communities wantto see and how we can facilitate the work of heroes and leadersliving wherever we work.So we are challenged to keep the vision of civil society freshand relevant and to constantly test ourselves on whether andhow our work makes a difference in the lives of those we serve.Written by Nancy Lindborg, President .7

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>From Human Rights to Civil SocietyIf all you manage to accomplish during your first year,”President Ells Culver told me shortly after I began my jobat <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> in the summer of 1989, “is to export anambulance from New Jersey to the hospital in Gaza towhich it was donated, you will have had a successful year.” Ithought then that this was an odd and strange way to evaluatethe impact of a year of my work. I had greater expectations ofwhat I could accomplish in twelve months.However, Ells knew something that I didn’t at the time. He knewthat the job he had just assigned to me would turn out to be oneof the most difficult challenges I would face at <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>. Healso knew that the export of the ambulance was extremely importantas it sent a signal about the universality of human rightsand highlighted the significance of demonstrating the equalityof all persons. As a piece of equipment, the ambulance met anurgent human need. As a symbol, however, it had a far rangingripple effect by directly interjecting the agency into a developmentactivity that was deemed to be almost totally political.Although this assignment from Ells was not the “origin” of the<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ civil society program, it evidenced the fertile soilout of which the program grew. At a time when many relief anddevelopment agencies shied away from the language of humanrights as a justification for their work, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> embraced it.It established a human rights desk with responsibility for developingan informed constituency that could become an advocatefor the people for whom <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> worked. More than25 study tours were organized to allow North Americans tohear for themselves the various perspectives – Syrian, Lebanese,Jordanian, Israeli and Palestinian - involved in the MiddleEast conflict. <strong>The</strong>se tours included American civil, political,religious leaders and opinion makers. One tour alone was organizedfor a group of reporters who wrote for religious publicationsthat had a collective readership in excess of 10 millionpersons.Even though this approach was based on the principle of lettingthe poor and victims of conflict speak for themselves unfilteredby foreign staff, it was not widely accepted by other colleagueorganizations. At presentations on the topic of “human rightsand development” sponsored by <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> at the Associationof Evangelical Relief and Development Organizations andInterAction in the early 1990’s, it was clear that many viewed the<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> approach critically. “You are mixing politics withhumanitarian intervention,” we were told by some. <strong>The</strong>y believedthis approach, if continued, “would destroy the credibilityof the relief and development community and only result in gettingyou expelled from the countries in which you work.” Othersworried less about the perceived politicization of assistance andmore about whether promoting human rights was an efficientand effective use of resources.This skepticism about human rights was deeply embedded evenwithin <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>. One Country Director was so frustrated byall of this talk coming from headquarters about human rights anddevelopment that he sent a blunt message to Portland statingthat if “HQ is really so insistent on promoting this agenda, theyshould send Lowell Ewert here so he can get himself killed tryingto implement it.” A headquarters staff person who had significantresponsibility for several international programs wasequally blunt when he took me aside one day in January 1991 tolet me know that “while I like you as a person, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> hasno business having someone like you on staff. You should gowork for a human rights group instead.”A smiling woman in Maluku, Indonesia fills jugs with water. (Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)Like many other good ideas that are ahead of their time, thesechallenges to the very philosophical core of the proposed humanrights program were what eventually gave it strength. <strong>The</strong>skepticism from both internal and external sources was the cruciblein which the subsequent civil society program was forged.<strong>The</strong>se skeptics forced advocates to be more specific, practicaland attuned to the potential harm that this approach couldcause. <strong>The</strong>y therefore deserve to be thanked for forcing therefinement and deepening of the theoretical foundation of thecivil society program that subsequently developed.So how exactly did the present day civil society program emergefrom this landscape of skepticism? In my opinion, the “tippingpoint” for civil society occurred in late Spring or early Summer1992 when a Human Rights Watch Report was issued that8

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>quoted Amartya Sen to say, “[E]very single famine in modernhistory has been caused, at least in significant part, by systematicabuse of human rights.” 2 In this article Human RightsWatch made the claim that if citizens were allowed to be civillyengaged in the political life of their nation they could take thesteps to ensure that there would be adequate food sufficient toavoid famines.This argument immediately resonated with <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> staff. Itwas the most persuasive rationale most had ever heard linkinghuman rights and thework of <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>. Icould literally see theconnection being madefor the first time in theeyes of some. It was a“light going on” kind ofevent that could not bedisguised.Even the colleague, whohad earlier told me that Ihad no business beingemployed by <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong>, was convinced.Later he suggested theexact wording of what wesubsequently referred toas the “four little magicwords” that funded<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ first civilsociety projects. Thosefour little words, insertedTwo female clients of the National Association of Business Women (NABW), a<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> partner organization, selling pants in open-air-market in Khojand,Tajikistan. (Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)into a contract with USDA allowed <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> Kazakhstan toutilize the monetized proceeds from the 1992 sale of 4,000 tons ofbutter oil to be used (in addition to the usual economic and agriculturaldevelopment) “to promote democratic processes.” <strong>The</strong>first projects intentionally designed by <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> to promotehuman rights began experimenting with an explicit strategy tofoster civil society. Before any project was funded by the monetizationprogram, we asked – how will this project promote humanrights? It was not an easy question to answer, and at timesit was not answered well. But it placed the human rights questionsquarely on the agenda for each and every project.We liked what we saw of the Kazak program and later our approachevolved to extend to other projects in other CentralAsian nations. It made a lot of sense even though there waslittle theory to back it up. <strong>The</strong> practice seemed to be effectiveand it was affirmed by those with whom <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> worked.However, it took another couple of years for <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> tounderstand what we had affirmed. We knew after thinkingabout this for a while that <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> was not, and should notbe, a human rights organization. But we also understood thatthe solution to most every problem <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> was attemptingto address in its interventions was based on the respect of fundamentalhuman rights.<strong>The</strong> bottom line was that the drafters of the Universal Declarationof Human Rights had it right when they made the claim thatthe respect for human rights was the key to peace in the world.<strong>The</strong> preamble states, “Recognition of the inherent dignity and ofthe equal and inalienable rights of all members of the humanfamily is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in theworld.” 3 This simple lesson, which represents a succinct summaryof the collective learning of the world community about thecauses of two horrific World Wars, seemed sound. <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> faced the challenge offiguring out how a developmentagency could promotehuman rights without beingdrawn off its core competencies.<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ civil societymandala was developed tointegrate practical grassrootsdevelopment with humanrights. It acknowledged thatthe one piece of human rightsthat <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> could directlyinfluence, and which fitwithin its development mandate,was to empower citizensto find their own solutions –to enhance their capability toparticipate, hold power accountableand work forchange nonviolently. At theend of the day, if citizens areempowered in this way, they will not just be equal partners inthe development process, but they will also be the drivers of it.When this happens, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> will have succeeded.Nothing has persuaded me that the lessons of the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights are no longer valid. Violations ofhuman rights are still the root cause of most of the challenges<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> seeks to address. <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ civil society strategyis adaptable and can reflect changing realities. Unlike the“rigidness” shown by the USSR in the late 1980’s and early1990’s when faced with internal pressures (and subsequentlyexploded into pieces because it could not “flex”), the <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> strategy can adapt, change and grow with the times. Empoweringpeople to take control over their lives will never be outof date. Agencies that affirm and assist empowerment will alwaysbe at the cutting edge because the edge moves asempowerment grows. It is a great place for <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> to beunder the umbrella of the Universal Declaration of HumanRights.Written by Lowell Ewert, Director of Peace and Conflict Studiesat Conrad Grebel University College and former Directorof <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ Human Rights Desk.9

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>Building Civil Society inTimes of TurmoilIn 1998 many experts thought Indonesia might break upand cease to exist. <strong>The</strong> financial crisis in late 1997 had hitIndonesia particularly hard. Many businesses and industriesdeclined precipitously under the burdens of enormousdebt and the devaluation of the currency. Urban areaswere particularly hard hit as the number of unemployed grewand as inflation reduced the value of the incomes of those luckyenough to continue their work. Riots and demonstrations inJakarta and other cities in May 1998 prompted President Suhartoto step down after more than 30 years as the head of a centralizedgovernment. <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> entered in February 1999.Within two years conflict broke out in several regions of thecountry eventually displacing 1.3 million people and negativelyaffecting millions more. East Timor split off in late 1999 and anactive, violent separatist movementcontinued to brew in Aceh.From the outset it was clear that<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ civil society approachwould be a key element ineffectively working in Indonesia.In 2000, Indonesia was included asa pilot country in the BuildingCivil Society in Times of Turmoilproject, a USAID-funded InstitutionalSupport Grant for civil society.Under this grant, most of<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> activity in Indonesiafocused on local non-governmentpartners. We had three objectivesin Indonesia: to improve the understandingand use of the civilsociety principles by our partners;to enable our staff to develop, implement,monitor and evaluate ourcivil society approach; and to increase<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ institutional capacity in the area of civilsociety.<strong>The</strong> Civil Society team in Indonesia identified good practices,studied how the use of the good practices affected impact, andgenerated a number of articles on our experiences. Lookingback, in those contexts where we and others perceived that wewere successful, three key elements were in place:1. Our staff learned about, internalized and contextualizedthe three principles of accountability, participation andpeaceful change, by linking government, business andcitizens.2. We applied these principles in the one-on-one contactwe had with partners and target populations.3. We modeled positive behaviors.Virtually all staff had some knowledge of and could talk aboutaccountability, participation and peaceful change. Initially weused civil society training materials that <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> had preparedduring the previous three to four years. Most of thosewere based on western perspective examples. But discussionsof Plato and Tocqueville did not resonate with Indonesians.Presentations on international declarations as a starting pointdid not mobilize people. We began to make progress when wetalked about the principles in relation to project activities orwhen examples were drawn from observations in communitiesTwo Indonesian women washing clothes in a rocky stream. (Nick Macdonald/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)where we worked. Local examples made it easier for staff andpartners to see how they could apply the principles in theirwork. This process of discovering meaning in local contextsbrought accountability, participation and peaceful change tolife. <strong>The</strong> principles became less abstract and more tangible. <strong>The</strong>same is true of people’s understanding for links between government,business and citizens.We conducted numerous trainings with project staff and partnerson the meaning of the principles, their importance and theirapplication. But often it was not until we sat down with a partnerand went through a finance report that they understood10

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>what accountability was about. Monitoring visits were a goodvenue for learning about participation. Through dialogue withpartners about real projects, both <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> and our partnersrecognized situations in which communities were not beinglinked and came up with creative ways to enable links that are soessential to peaceful change. Although we talked about theneed to work togetherand the commonalitiesthat bind us togetheras people, initiallystaff recruited fromdifferent communitieswere still suspiciousof each other. <strong>The</strong>same was true whenwe brought organizationsfrom differentcommunities together.As our staff and ourpartners began toshare common interestsand problemsthey realized that theyhad much to gain fromworking together. Inone conflict affectedarea staff and partnersbegan to recognizethat sometimes, as onestaff person described it, “Weboth thought the same thingsabout each other, and we wereboth wrong.”Dayna Brown in conversation with beneficiaries and local partners in the streets ofMaluku province Indonesia. (Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)Modeling positive behaviorsplayed itself out in variousways. Sometimes <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>brought them to the table andsometimes we picked up positivebehaviors from others.Accountability was modeled inJakarta in the way we allocatedand tracked distribution infood for work activities. Communitymembers organizedgroups in their areas to workon community projects and toreceive food on distributiondays. Many of these groupleaders had little past leadershipexperience. When a major flood struck Jakarta in early2002, the communities where we did food for work activitieswere mu ch better, when compared to communities where we hadnot worked, at documenting distributions of relief contributionsto flood-affected families and creating a paper trail when theyreallocated resources to neighboring communities.In conflict areas our offices were located in neutral space, whichwas considered safe for people from communities in conflict andwhere people from otherwise isolated communities could meet totalk to friends or trade. When we set up our offices in theseneutral spaces several developments followed. Other organizationsbegan to move their offices into neutral space. In Ambon,a new main market for the townsprung up outside <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong>’ office. Governmentagencies began organizingactivities in neutral space, includingalternative educationopportunities for studentsfrom conflict affected communities.Our staff from communitiesin conflict worked together,an example which manyof organizations, governmentpartners and target communitiesincreasingly followed.In many of the contexts inwhich the team in Indonesiaworked change was not immediate.During the process ofattaining significant change weengaged in activities responsiveto the environmentthat produced rapidsmall-scale results.Most of these activitieswere funded by smallgrants to local organizationsand included watersystems, provisionof school supplies,school reconstruction,shelter, micro-credit orprovision of non-fooditems. In areas affectedby conflict, priority wasgiven to projects addressingcommon intereststhat created linksbetween communitiesacross the lines of conflict.We kept the theoreticalmessages simple.We practiced the behavioralsolutions toproblems and continually looked for local examples to illustratethe theoretical. This enabled a growing number of small changesthat occasionally led to widespread change far beyond our originalexpectations.Women making recycled paper in a community center in Indonesia. <strong>The</strong> centerwas constructed as part of Mery <strong>Corps</strong>’ food-for-work program. (Bob Newell/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>)Written by Tom Hensleigh Ethiopia Country Director, andformer Indonesia Country Director, 1999-2004.11

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>Merging Civil Society andConflict ManagementOver the past year, the Conflict Management Group(CMG) has been officially integrated into the CivilSociety and Conflict Management Group (CS andCMG), which is part of the Technical Support Unit(TSU) in Headquarters. <strong>The</strong> following exa mples showcase somedifferent ways that the merger is already having an impact on<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> programming and operations:Pilot Activities and Initial Results in the FieldShortly after the merger took place, USAID awarded <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> a two year, $1 million program for Conflict Preventionand Resolution in the Southern Nations, Nationalities andPeoples Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia. <strong>The</strong> program includes anintensive training of trainers with key official and unofficial communityleaders in hands-on conflict management skills whichthey are now implementing in the ten program areas of southernEthiopia. A member of the CS and CMG team was built into thebudget to assist with program start-up, co-lead the training oftrainers, and provide support and monitoring over the life of theprogram. Through working with Ruth Allen, who is now an insiderto <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>, the Ethiopia team gained confidence intheir own abilities to carry the program forward and access tolong term technical assistance. Ruth gained direct experience inprogram start-up and implementation, and has built essentialrelationships with field staff which will facilitate more effectivelong-term support.<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ programs in Central Asia have had a long-termfocus on conflict prevention and the agency has committed substantialresources to document progress made in using developmentinterventions as a tool for the prevention of potential conflict.However, the program teams have struggled in developingtools to measure attitudinal and behavioral changes in communities.A CS and CMG team member, Arthur Martirosyan, madetwo visits to Tajikistan and worked with the team to develop asurvey tool to serve as a baseline and end-line index for thecommunities where <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> is implementing the two yearTajikistan Conflict Prevention Program. <strong>The</strong> baseline hasnow been conducted, and while there are still challenges facingthe team in data analysis, the support has moved the programsubstantially closer to measuring impact at the attitudinal level.Combining Conflict Management and Community MobilizationSkills and ProcessesAnother result of the merger is the development of a frameworkthat embeds <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ traditional community mobilizationprocess with conflict management methodologies. <strong>The</strong> aim ofthe framework is to help people to understand the conflict dynamicsof the contexts in which they are working and negotiation/problem-solvingskills they could apply throughout thecommunity mobilization process. <strong>The</strong> framework , created byAnna Young from the New Initiatives team, can be accessed onthe Digital Library by searching the title, Embedding ConflictManagement and Analysis Tools into the Community MobilizationProcess.TrainingDuring the past year, CS and CMG staff have taken advantageof collective meetings and gatherings to present some of theframeworks and tools to different people across <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.For instance, <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> staff received training on negotiationskills at the Leadership Conference in Beijing in November 2004,and at the Finance Conference in Thailand in July 2005. In June2005, MC field and headquarters staff from across twenty countryprograms received training on negotiation, effective communication,and conflict analysis through presentations, interactiveexercises, simulations and discussions over the course of threedays.In July 2005 two CS and CMG team members, Ted Johnson andDavid Steele, provided a five-day training program for <strong>Mercy</strong><strong>Corps</strong> staff at three field offices in Indonesia to assist their abilityto negotiate better with government and to develop moreeffective action plans for ongoing projects. <strong>The</strong> first three daysof the training were spent introducing staff to a negotiation approachbased on meeting the interests of all parties. Participantslearned various negotiation tools, including skills in perceptionclarification, communication, persuasion, relationship mapping,and option creation among others. During the last two days, thefocus shifted to utilizing these skills in a problem solving process.Each field office worked as a team to develop an actionplan that could lead to greater success in implementing a localproject. <strong>The</strong> projects chosen by the field offices included: ahealthy school nutrition project in Sumatra, an urban agricultureproject in Jakarta, and the disposal of zinc pile rubbish in Aceh.<strong>The</strong> CS and CMG team looks forward to working with more membersof the <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> family in the coming years, and is committedto sharing our new tools and methodologies, as well ascritical lessons learned along the way.Dayna Brown, Program Manager, Civil Society and ConflictManagement Group.12

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong><strong>The</strong> Universal Declaration ofHuman RightsOn December 19 th 1948 the General Assembly of theUnited Nations adopted Resolution 217 A (III)known as <strong>The</strong> Universal Declaration of HumanRights. <strong>The</strong> Declaration’s purpose is to provide acommon understanding of the rights and fundamental freedomsof all people and a “common standard of achievement for allpeoples and all nations”. <strong>The</strong> Declaration was conceived as ameans to achieve international peace through respect for humanrights. With the ratification of the Declaration the question ofindividual state sovereignty arose for the first time. States hadnever before agreed to restrictions on their domestic behaviorand had never allowed their treatment of their citizens to becomea subject of international scrutiny.<strong>The</strong> preamble to the Declaration states that the foundation forfreedom, justice and peace in the world is the respect for theinherent dignity and inalienable rights of all human beings, andthat disregard for these rights has resulted in atrocities againsthumankind. Two major themes running through the Declaration’sthirty articles are accountability and participation. Article2 states that every person, regardless of their race, color, sex,language, religion, political or other opinion, national or socialorigin, property, birth or other status, has the right to:- equal protection under the law (Article 7);- take part in the government (Article 21);- equal access to public services (Article 21); and- be the basis of the government’s authority throughgenuine elections (Article 21).In upholding these rights the state must ensure that no one besubject to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile (Article 9), that allhave access to a fair and public hearing (Article 10), that thosecharged with a penal offence be presumed innocent until provenguilty (Article 11) and that an individual’s rights and freedomscan be limited only if they infringe the rights of others or in orderto maintain public order and the general welfare of society(Article 29).For more information, and the full text of the Universal Declarationof Human Rights, see the United Nations’ website atwww.un.org/rights.Comments and suggestions areencouraged and should be directed to:civilsociety@mercycorps.orgInternational Headquarters3015 SW First Ave. 10 Beaverhall Rd.Portland, OR 97201 Edinburgh EH7 4JEUSAScotland, UKTel: +503.796.6800 Tel. 44.131.477.3677<strong>The</strong> next issue of <strong>The</strong><strong>Bridge</strong> will highlight<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>’ work withyouth.If you are interested in contributingan article or have ideas forpossible articles please contact us.13

Vol. V Third Quarter 2005<strong>The</strong> <strong>Bridge</strong>Civil Society ResourcesCIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen ParticipationCIVICUS is an international alliance with over 1,000 members from 105countries that works to strengthen citizen action and civil society in areaswhere citizen participation and freedom are threatened.www.civicus.orgDevelopment GatewayDevelopment Gateway is an interactive site that bring together people, resources, and information on development and poverty reduction and providesa venue for communities to share their experiences.www.developmentgateway.orgInterActionInterAction: American Council for Voluntary International Action, a U.S.based international development and humanitarian organization seeks tobring its 165 members together to impact policy and debate.www.interaction.orgInternal Resources:• Civil Society in Action Parts 1 and 2. This set of resources and workshop materials helps explain howMerc<strong>Corps</strong>’ Civil Society Approach, Principles and Framework strengthen all aspects of programming. Onthe Digital Library search for “Civil Society in Action”.• Numerous conflict management tools and documents are available on the Digital Library, including Seven Elementsof Good Negotiation, Difficult Conversation, Difficult People and training cases and exercises.<strong>The</strong>se resources can be found on the Digital Library under Program Development and Management/Conflictand Peaceful Change/Conflict Management.Endnotes:Page 6 1 Indivisible Human Rights: <strong>The</strong> Relationship of Political and Civil Rights to Survival, Subsistence and Poverty, a publication of <strong>The</strong> Human Rights Watch, September 1992, pg.1.Page 9 2 Ibid.Page 9 3 <strong>The</strong> Universal Declaration of Human Rights December 10. 1948. http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.htmlCover Photo Credits From Left to Right:Row 1: Zalengei, West Darfur, Sudan – Cassandra Nelson/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Ujmire village, Kosovo – Matt Voltz/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> ; Guatemala – Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Aceh, Indonesia -Clarissa Meister-Petersen/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Kandahar, Afghanistan - Scott Heidler/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.Row 2: Kosovo – Gorm Gaare/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Mongolia – Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Eritrea - Michaela Ledesma/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Namangan, Uzbekistan - Kimito Mishina/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>;Najin, North Korea – Cassandra Nelson/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.Row 3: Wassit, Iraq – Cassandra Nelson/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> Kanapathichetticullumpuppam, India – John Stephens/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Pakistan – Kim Johnston/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Darfur, Sudan –Henry McInnis/Sunday Mail; Sulimanayah, Iraq - Pete Sweetnam/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.Row 4: Pakistan – Laura Guimond/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Chaiyang, China - Jeremy Barnicle/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; New York, United States – Elena Olivo/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Sir Lanka - Jeff Greenwald for<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Ethiopia - Michaela Ledesma/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong> .Row 5: India – John Stephens/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Lower Lingtem, India - Colin Spurway/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Sisimetepec, El Salvador -Laura Guimond/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Afghanistan - Lana Slezic/UNHCR; Albania - Vladimir Dango/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>.Row 6: Manicaland, Zimbabwe - Susan Romanski/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Mongolia – <strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Iraq – Cassandra Nelson/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; India - Colin Spurway/<strong>Mercy</strong> <strong>Corps</strong>; Darfur, Sudan -Henry McInnis/Sunday Mail.14